Ellen Gould Harmon White

ELLEN GOULD HARMON WHITE TIMELINE

1827 (November 26): Ellen Gould Harmon was born, with identical twin Elizabeth, in Gorham, Maine.

1840 (March): Ellen Harmon first heard William Miller lecture in Portland, Maine.

1842 (June 26): Ellen was baptized into her family’s Chestnut Street Methodist Church.

1843 (February–August): Five committees were appointed in the Chestnut Street Methodist Church to deal with the Harmons after Ellen refused to stop testifying that Jesus would return on October 22, 1844.

1844 (October 22): Ellen Harmon and other Millerites were greatly disappointed when their millennial expectations failed.

1844–1845 (Winter): Ellen experienced waking visions, and traveled to share her visions with scattered bands of disappointed Millerites.

1846 (August 30): Ellen married James Springer White.

1847–1860: Ellen White gave birth to four sons, only two of whom survived to adulthood, James Edson (1849–1928) and William (Willie) Clarence (1854–1937). Both John Herbert (September 20, 1860-December 14, 1860) and Henry Nichols ( August 26, 1847-December 8, 1863) died before reaching adulthood.

1848 (Autumn): Ellen White experienced the first of many visions on health.

1848 (November 17–19): Ellen White had a vision instructing James to commence printing “a little paper.” Adventist Publishing later grew from the resulting periodical, originally called The Present Truth.

1851 (July): Ellen published A Sketch of the Christian Experience and Views of Ellen G. White, the first of twenty-six books she would publish during her lifetime.

1863: The Seventh-day Adventist Church was officially organized.

1876 (August): Ellen White delivered a speech on temperance in Massachusetts to a crowd of 20,000, the largest she would address in her lifetime.

1881 (August 6): James White died.

1887: The General Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church voted to give Ellen White ordination credentials.

1895: Ellen White called for Adventist women to be “set apart by the laying on of hands” to ministerial work.

1915 (July 16): Ellen Gould Harmon White died at her home, Elmshaven, near St. Helena, California.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Ellen Gould Harmon and her identical twin Elizabeth were born the last of eight children to Robert Harmon and Eunice Gould Harmon in Gorham, Maine. When Ellen was a few years old her family moved to Portland, Maine, where her father worked as a hatmaker, and the family began to attend the Chestnut Street Methodist Church. Ellen’s parents were deeply religious, and as she grew up she participated with her mother in the Methodist “shout” tradition, crying out, singing, and participating in worship as moved by the Holy Spirit.

In her later writings, Ellen [Image at right] describes two events that occurred when she was about age nine as formative. In 1836, she found a  scrap of paper “containing an account of a man in England who was preaching that the Earth would be consumed in about thirty years” (White 1915:21). She would later recount that she was so “seized with terror” after reading the paper that she “could scarcely sleep for several nights, and prayed continually to be ready when Jesus came” (White 1915:22). In December of the same year, she was hit in the face by a stone thrown by a schoolmate “angry at some trifle” and was so badly injured that she “lay in a stupor for three weeks” (White 1915:17, 18). She was a shy, intense, and spiritual child, and these two events focused her attention on the destiny of her soul, especially as her injuries forced the formerly strong student to withdraw from school and spend her days in bed shaping crowns for her father’s hat-making business.

scrap of paper “containing an account of a man in England who was preaching that the Earth would be consumed in about thirty years” (White 1915:21). She would later recount that she was so “seized with terror” after reading the paper that she “could scarcely sleep for several nights, and prayed continually to be ready when Jesus came” (White 1915:22). In December of the same year, she was hit in the face by a stone thrown by a schoolmate “angry at some trifle” and was so badly injured that she “lay in a stupor for three weeks” (White 1915:17, 18). She was a shy, intense, and spiritual child, and these two events focused her attention on the destiny of her soul, especially as her injuries forced the formerly strong student to withdraw from school and spend her days in bed shaping crowns for her father’s hat-making business.

Particularly after these events, Ellen experienced bouts of “despair” and “mental anguish” as she sought assurance of her salvation in the face of her burgeoning belief in the soon-coming advent of Jesus Christ, and her trepidation at Methodist ministers’ descriptions of a “horrifying” “eternally burning hell” (White 1915:21, 29). In March 1840, Ellen heard lectures by William Miller (1782-1849) in Portland, Maine. Bible study had led Miller to conclude that Christ would return in 1843, though he and his followers eventually settled on October 22, 1844 as the anticipated date of the second coming. Ellen accepted Miller’s prediction, and, after a long spiritual search, felt the assurance of God’s love at a Methodist camp meeting in Buxton, Maine in September 1841. She was baptized into the Chestnut Street Methodist Church in Casco Bay on June 26, 1842. Still, her anxiety returned and intensified as she became focused on Millerite expectations. After hearing Miller’s second series of Portland lectures in June 1842, Ellen experienced religious dreams and, once again, the assurance of salvation, and was “struck down” by the “wondrous power of God” (White 1915:38).

By early 1843, as the date of the expected advent neared, Ellen felt called to pray and testify publically “all over Portland,” which she did. Between February and June 1843, at least in part in response to Ellen’s public support for Millerite millennial predictions, her congregation appointed a series of five committees to deal with the Harmon family. Ellen refused to back down from her conviction that Jesus would return on October 22, 1844, and the Harmons were expelled from their congregation in August 1843.

When Christ failed to return to the Earth on October 22, Millerites, along with Ellen, were deeply disappointed. Leaders of the movement, including William Miller and Joshua Himes (1805-1895), reorganized, abandoned date setting, and rejected the ecstatic worship style that had prevailed in the movement in the months preceding the Great Disappointment. Nonetheless, some believers, dubbed radicals by more moderate Millerites, continued to gather in small groups to participate in emotionally charged worship (Taves 2014:38–39). Worshiping in one of these gatherings with five other women in December 1845, Ellen experienced a vision in which she saw that something important had occurred on October 22, 1844: Christ had entered the heavenly sanctuary and commenced the final work of judging souls, and he would return to Earth as soon as that work was complete (White 1915:64–65). Her vision, which laid out what would come to be called the investigative judgment and sanctuary doctrine, explained Christ’s failure to return in 1844 and bolstered continued hope in his imminent coming.

Ellen Harmon traveled among bands of former Millerites in the winter and spring 1845 sharing her vision. She was not the only Portland-area visionary: Adventist historian Frederick Hoyt identified newspaper accounts of five others in and around Portland who saw visions after October 1844 (Taves 2014:40). Though in her later written accounts Ellen would portray herself as calmly receiving visions (an image perpetuated in official Adventist renditions of the prophet since before her death) recently uncovered historical documents indicate that in her early prophetic experiences she participated in “noisy” emotional worship that lacked “order or regularity” (Numbers 2008:331). Court testimony from the 1845 trial of Israel Dammon on charges of vagrancy and distrurbing the peace described radical adventist worshipers crawling on the floor, hugging and kissing one another, “[losing] their strength and fall[ing] to the floor,” and “wash[ing] each other’s feet” (Numbers 2008:334, 338). Witnesses identified the “one that they call Imitation of Christ,” Ellen, lying on the floor “in a trance,” occasionally “point[ing] to someone,” and relaying messages to them, “which she said w[ere] from the Lord” (Numbers 2008:338, 330, 334, 336). During this period Ellen met James Springer White (1821-1881), a former Christian Connection minister turned Millerite, who joined in this emotional worship. He accepted her visions, and accompanied her in her travels.

When rumors of their unchaperoned travels began to circulate, James and Ellen married, [Image at right] thereby uniting the two figures who  would prove most instrumental in forming Seventh-day Adventism. After marrying, Ellen and James had four sons, who they often left in others’ care for weeks at a time as they traveled around the Northeast during the 1850s to provide leadership and guidance to dispersed bands of adventists. In the late 1840s, Ellen and James became acquainted with Joseph Bates (1792-1872), a former British navy captain, revivalist minister, abolitionist, and advocate of temperance and health reform. Each of the three contributed to the beliefs that would define Seventh-day Adventism, especially belief in the sanctuary doctrine, the Great Controversy between Christ and Satan, the impending advent, vegetarianism, and the seventh-day Sabbath. Before formal organization, Ellen’s visions settled debates among male adventist leaders regarding theology, belief, and practice, so that by 1863, when Seventh-day Adventism was officially organized, Ellen’s visions had confirmed core Adventist beliefs and practices.

would prove most instrumental in forming Seventh-day Adventism. After marrying, Ellen and James had four sons, who they often left in others’ care for weeks at a time as they traveled around the Northeast during the 1850s to provide leadership and guidance to dispersed bands of adventists. In the late 1840s, Ellen and James became acquainted with Joseph Bates (1792-1872), a former British navy captain, revivalist minister, abolitionist, and advocate of temperance and health reform. Each of the three contributed to the beliefs that would define Seventh-day Adventism, especially belief in the sanctuary doctrine, the Great Controversy between Christ and Satan, the impending advent, vegetarianism, and the seventh-day Sabbath. Before formal organization, Ellen’s visions settled debates among male adventist leaders regarding theology, belief, and practice, so that by 1863, when Seventh-day Adventism was officially organized, Ellen’s visions had confirmed core Adventist beliefs and practices.

In November 1848, Ellen Harmon White proclaimed the “duty of the brethren to publish the light,” and instructed her husband James that he “must begin to print a little paper and send it out to the people” (White 1915:125). Visions relaying health, education, and mission followed. Ellen experienced numerous bouts of poor health in her lifetime, James’ health often suffered from overwork, and two of the couples’ four sons died. So it is no surprise the she was fascinated by health. White’s message of health is demonstrably similar to ideas advocated by other nineteenth-century health reformers (Numbers 2008:chapter three). Her originality was less in the specifics of her messages of health, education, or mission, than in her conceptualization of, and ability to motivate Adventists to create interdependent systems of religious institutions directed toward serving the goals of Seventh-day Adventism. Adventists were, according to White, to be educated and religiously socialized in Adventist schools where they could prepare for professional work in Adventist institutions. Adventists were to adhere to their health message, but also, as their aptitudes allowed, be trained as physicians to minister through healing, or as ministers, educators, literature evangelists, secretaries, administrators, editors, or in a variety of other professions to work in the service of Adventism.

As White’s visions found increased acceptance, she gained confidence as a prophetic speaker and writer. Ellen and James traveled extensively among Adventists, and James was Ellen’s supporter and sometimes-collaborator in speaking and publishing. Even before Adventism’s official organization, the couple “developed a pattern” in public speaking: “James would preach a closely reasoned, text based message during the morning sermon hour, and Ellen would conduct a more emotive service in the afternoon” (Aamodt 2014:113). Ellen was also a prolific author, publishing twenty-six books, thousands of periodical articles, and numerous pamphlets in her lifetime. She relied on “literary assistants” to help her prepare work for publication, and James often helped her to edit her work. His extensive contributions took a toll, and James’ health declined in the 1870s. Ellen increasingly traveled without him, and spoke to audiences, including general audiences of thousands, about health, temperance, and other topics. Her favorite son, W. C. (Willie), accompanied her when James’ illness prevented travel, and even more after James White died in 1881.

Ellen’s leadership style became more sedate as she aged. She had had religious dreams as a girl before she experienced religious trances or waking visions, and though religious dreams replaced Ellen’s waking visions by the 1870s, she continued to play an instrumental role in shaping Adventism. She wrote long, and sometimes highly critical, letters to church leaders, often addressed meetings of the General Conference, and published extensively. Ellen spent nine years during the 1890s in Australia, and influenced the movement significantly after her return to America, in part by encouraging the election of A. G. Daniels (1858-1935), her protégé and president of the Australian Union Conference, as president of the General Conference in 1901. At the same gathering she promoted a major denominational reorganization that, though highly controversial, passed and was successfully implemented. She delivered eleven addresses during the last General Conference session that she was able to attend in 1909, and thereafter confined herself increasingly to her home, Elmshaven, near St. Helena, California, where she died in 1915.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Ellen White was indelibly shaped by the Methodism of her childhood, and Seventh-day Adventism incorporated beliefs in a literal creation, the Trinity, the incarnation of Christ, the virgin birth, substitutionary atonement, the second coming, resurrection of the dead, and judgment. In what Adventists regard as Ellen White’s first vision, she saw that on October 22, 1844 Christ entered the heavenly sanctuary and commenced the second and last phase of his atoning work for humans. At the close of this work, Christ would return. White’s explanation of the delayed advent helped to establish the investigative judgment and sanctuary doctrine in Adventist theology of atonement, as well as to define the advent as near.

In addition to the investigative judgment and sanctuary doctrine, Ellen White’s explanation of the Great Controversy [Image at right] anchors  Adventist theology. Her articulation of the Great Controversy posits a battle between good and evil that began in heaven, and frames all of life on Earth. The controversy began when Satan, a created being, used his freedom to rebel against God, and some angels followed him. After God created the Earth in six days, Satan introduced sin to Earth, leading Adam and Eve astray. God’s perfection in humans and creation was damaged, culminating eventually in the destruction of creation in a universal flood. Christ was God incarnate, and God provides angels, the Holy Spirit, prophets, the Bible, and the Spirit of Prophecy to guide people toward salvation, and the ultimate victory of good.

Adventist theology. Her articulation of the Great Controversy posits a battle between good and evil that began in heaven, and frames all of life on Earth. The controversy began when Satan, a created being, used his freedom to rebel against God, and some angels followed him. After God created the Earth in six days, Satan introduced sin to Earth, leading Adam and Eve astray. God’s perfection in humans and creation was damaged, culminating eventually in the destruction of creation in a universal flood. Christ was God incarnate, and God provides angels, the Holy Spirit, prophets, the Bible, and the Spirit of Prophecy to guide people toward salvation, and the ultimate victory of good.

The three angels of Revelation 14 capture the distinguishing aspects of Seventh-day Adventism. Guided by Ellen White’s visions, early Adventists interpreted the decades prior to, and culminating in, Miller’s message of the soon-coming advent as fulfilling the first angel’s message. The second angel’s message was fulfilled when Millerites came out of “Babylon,” their churches, to join the Millerite movement in the summer of 1844. The third angel’s message was realized as believers accepted and adhered to the seventh-day (Saturday) Sabbath.

Interpretation of the three angels’ messages evolved over time as it became necessary to admit both converts and children of believers to the movement. Though Ellen and James White initially resisted the idea that salvation was available to those who were not Millerites on October 22, 1844, they eventually accepted that belief. The reconciliation of the still-soon-coming advent with emphasis on October 22, 1844 as a critical date allowed Adventism to embrace its Millerite beginnings and attract new converts. In addition to delineating Adventist theology, Ellen White’s visions promoted practices, such as worshiping on the seventh-day and same-sex foot washing, which helped to define the religion.

As time passed, Ellen White’s publishing on health, education, mission, and humanitarianism provided Adventists focus and work to hasten Christ’s return. White’s health message incorporated aspects of the nineteenth-century health reform movement, including abstinence from alcohol, meat, and tobacco, and emphasis on exercise, fruits, nuts, grains, and vegetables. White advocated dress reform for Adventist women after seeing the bloomer costume during a stay at Our Home on the Hill, a New York sanitarium. She developed her own pattern, which included pants and a skirt that fell lower on the boot, and wore it herself, but ceased promoting dress reform when Adventists resisted women wearing pants. She also encouraged Adventists to study medicine, and she selected an important protégée, John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943), to head the first Adventist sanitarium, the Western Health Reform Institute (called the Battle Creek sanitarium), after he completed his training. Adventism lost the Battle Creek sanitarium when Kellogg split with Adventism after his 1903 publication of The Living Temple. Nonetheless, Ellen White contributed to the development of numerous other Adventist institutions, including additional sanitariums, schools and colleges, and publishing houses.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Even before their official organization into a denomination, Adventists accepted the seventh-day, Saturday, as the Sabbath. Ellen’s visions settled disputes about when the Sabbath began (at sundown Friday) and when it ended (at sunset on Saturday). In its early decades, Adventists were dispersed, and so itinerant ministers, often in married ministerial teams, traveled to serve the faithful. After organization, Adventists commenced erecting church buildings, in which worship was held. Adventist worship included time during which Adventists washed the feet of others of the same sex. Baptism was by immersion after a public confession of faith. Ellen White encouraged Adventists to marry only after careful consideration, forbade marriage to non-Adventists, and wrote that “adultery alone can break the marriage tie” (Ellen G. White Estate n.d.). Outside of worship, White encouraged believers to dress modestly, live simply, and refrain from worldly amusements such as reading fiction or attending the theater.

LEADERSHIP

Ellen White called herself “God’s messenger” rather than a prophet, and she insisted that the Bible was “authoritative, infallible revelation.” The Bible, though, did not “rende[r] needless the continued presence and guidance of the Holy Spirit” (White 1911:vii). Her visions, the “lesser light,” illuminated the truth of the Bible.

Ellen White never held certified office. After the church was formally established, she received a ministerial stipend. She insisted that she was ordained by God, and that, for her, ordination by men was unnecessary. The General Conference nonetheless voted to give her ordination credentials beginning in 1887.

White took positions and provided counsel on things as mundane as the site of a new building, and as significant as General Conference debates over theology. Despite her lack of official standing, no other leader influenced Adventism as much. In addition to her voluminous books and pamphlets, she wrote thousands of pages of correspondence to Adventists, some of which were collected in her “testimonies” (Sharrock 2014:52). She provided pointed criticism and direction in these letters, which often detailed specific failings of individuals or churches.

White also wrote extensively to church presidents, counseling and sometimes reprimanding them. In some cases, she sent harshly critical letters that directed the recipient, a church president, to read aloud to colleagues (Valentine 2011:81). White also provided encouragement in her letters, especially when leaders followed her counsel. In addition, she attended regularly meetings of the General Conference, sometimes as a voting delegate, and she addressed the General Conference numerous times. At meetings of the General Conference, her view often prevailed, as it did in 1909, when she embraced reorganization of the General Conference amid controversy over the question.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Ellen White was a socially awkward young woman who was often in poor health, and early in her prophetic career the authenticity of her visions was challenged. James White worked, especially in his role as editor of the Review and Herald , to distinguish Ellen from the “fanaticism, accompanied by false visions and exercises” of other visionaries in and around Portland, Maine in the wake of the Great Disappointment (White 1851). He also encouraged onlookers to subject her to physical tests while in vision, such as covering her nose and mouth.

Though James was generally Ellen’s most effective advocate, he ceased publishing her visions in 1851 in response to what was dubbed the “shut-door” controversy. Before 1851 Ellen and some other believers, including James, had advanced the idea that the door to salvation closed on October 22, 1844, and that those who had not accepted Miller’s message by that date could not be saved. As time continued, however, and as both potential converts and children born to believers sought salvation through the movement, that position became less tenable. By 1851, Ellen acknowledged that the door to salvation remained open, and James, frustrated by critics of the prophet, stopped publishing her visions in the Review . Ellen’s visions became infrequent, resuming only in 1855 after a group of church leaders criticized James’ decision, and replaced him as editor of the Review .

Ellen was also criticized as a female religious leader by some inside and outside the movement who cited the Pauline epistles and other texts as evidence that women should not preach or lead. The early Review and Herald responded to these criticisms. A number of Adventist pioneers, including Joseph H. Waggoner and J. N. Andrews (1829-1883), wrote Review and Herald articles defending women’s right to preach, speak publically, and minister. Ellen White left defense of her role to her husband and other male leaders, but did advocate for women to serve in ministry and other leadership roles. By the late 1860s, as Adventism developed a route to ordination, women participated, and received ministerial licenses. Lulu Wightman, Hattie Enoch, Ellen Lane, Jessie Weiss Curtis, and other women were licensed and served successfully in ministry. The question of women’s ordination was presented for debate at the 1881 General Conference session. Ellen, mourning James’s recent death, was not in attendance, however, and the resolution was tabled and never voted on.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of movement founder Ellen Gould Harmon White. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Image #2: Photograph of James and Ellen Gould Harmon White. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Image #3: Drawing of the turmoil accompanying the Great Controversy. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

REFERENCES

Aamodt, Terrie Dopp. 2014. “Speaker.” Pp. 110-125 In Ellen Harmon White: American Prophet, edited by Terrie Dopp Aamodt, Gary Land, and Ronald L. Numbers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellen G. White Estate. n.d. “Ellen G. White Counsels Relating to Adultery, Divorce and Remarriage.” Accessed from http://ellenwhite.org/sites/ellenwhite.org/files/books/325/325.pdf on 15 March 2016.

Numbers, Ronald L. 2008. Prophetess of Health: A Study of Ellen G. White, Third Edition. Grand Rapids, MI and Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans.

Sharrock, Graeme. 2014. “Testimonies.” Pp. 52-73 in Ellen Harmon White: American Prophet, edited by Terrie Dopp Aamodt, Gary Land, and Ronald L. Numbers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Taves, Ann. 2014. “Visions.” Pp. 30-51 in Ellen Harmon White: American Prophet, edited by Terrie Dopp Aamodt, Gary Land, and Ronald L. Numbers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Valentine, Gilbert M. 2011. The Prophet and the Presidents. Nampa, ID: Pacific Press Publishing Association.

White, Ellen Gould. 1915. Life Sketches of Ellen G. White. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Publishing Association.

White, Ellen G. 1911. The Great Controversy Between Christ and Satan. Washington D.C.: Review and Herald Publishing Association.

White, Ellen. 1895. “The Duty of the Minister and the People.” The Review and Herald, July 9. Accessed from http://text.egwwritings.org/publication.php?pubtype=Periodical&bookCode=RH&lang=en&year=1895&month=July&day=9 on 13 January, 2016.

White, James. 1851. “Preface.” First Edition of Experience and Views, by Ellen G. White, v–vi. Accessed from http://www.gilead.net/egw/books2/earlywritings/ewpreface1.htm on 3 March 2016.

Post Date:

21 April 2016

the mid-1970s (Mageary 2012; Milenković 2007). The two subcultures shared opposition to established institutions, but punks rejected hippies for a “do whatever you want as long as no one else is hurt” philosophy and a lack of real understanding about what would be necessary for systemic change. Punk subculture has evidenced considerable class diversity but has been overwhelmingly white. The subculture has developed and been shaped differently internationally, reflecting specific cultural traditions.

the mid-1970s (Mageary 2012; Milenković 2007). The two subcultures shared opposition to established institutions, but punks rejected hippies for a “do whatever you want as long as no one else is hurt” philosophy and a lack of real understanding about what would be necessary for systemic change. Punk subculture has evidenced considerable class diversity but has been overwhelmingly white. The subculture has developed and been shaped differently internationally, reflecting specific cultural traditions. on community within punk culture. Loose punk communities are built around punk bands, with their distinctive musical styles and political messages. In addition to rejection of conventional society, unifying values within decentralized, punk communities include a sense of being outsiders, strong individualism, egalitarianism, personal autonomy and authenticity, the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethic, and aversion to “selling out.” Members wear X or XXX tattoos (a symbol that was stamped on the hands of underage individuals entering nightclubs to forestall their purchase of alcohol) on their hands as symbols of group membership. Although the place of religion in punk subculture was a matter of some controversy, during the 1990s Christian, Krishna consciousness, Islamic (Taqwacore – “piety” core), and Buddhist (Dharma Punx) strands of punk subculture emerged (Fiscella 2012; Stewart 2011, 2012).

on community within punk culture. Loose punk communities are built around punk bands, with their distinctive musical styles and political messages. In addition to rejection of conventional society, unifying values within decentralized, punk communities include a sense of being outsiders, strong individualism, egalitarianism, personal autonomy and authenticity, the DIY (Do It Yourself) ethic, and aversion to “selling out.” Members wear X or XXX tattoos (a symbol that was stamped on the hands of underage individuals entering nightclubs to forestall their purchase of alcohol) on their hands as symbols of group membership. Although the place of religion in punk subculture was a matter of some controversy, during the 1990s Christian, Krishna consciousness, Islamic (Taqwacore – “piety” core), and Buddhist (Dharma Punx) strands of punk subculture emerged (Fiscella 2012; Stewart 2011, 2012). in response to the heavy drug use was Straight Edge punk. Straight Edge originated in 1981 when Ian MacKaye wrote a song by that title for Minor Threat, a hardcore punk band. In the song he asserted that he was claiming “the straight edge” by rejecting drugs, alcohol, and casual sex. In addition to these three primary principles, many straight edge punks support vegetarianism, feminism. There is also a positive orientation in the culture, which involves making choices in one’s life that produce positive outcomes.

in response to the heavy drug use was Straight Edge punk. Straight Edge originated in 1981 when Ian MacKaye wrote a song by that title for Minor Threat, a hardcore punk band. In the song he asserted that he was claiming “the straight edge” by rejecting drugs, alcohol, and casual sex. In addition to these three primary principles, many straight edge punks support vegetarianism, feminism. There is also a positive orientation in the culture, which involves making choices in one’s life that produce positive outcomes. Body Awareness Project in 2000, which had the objective of teaching troubled youth mindfulness meditation and emotion coping strategies. In 2006, the organization was merged with a sister non-profit, and then in 2007, was merged again with Vision Youthz, an aftercare program for youth located in San Francisco. The three organizations have continued to work together in an effort to serve at-risk youth in the area. Levine currently serves on the Board of Directors (“Mind Body Awareness Project” n.d.). Levine went on to found the Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society in 2008 as a means of making Buddhist teachings accessible to everyone. The first center was located in Melrose, California, and about a year later the organization moved to Santa Monica. Subsequently, many chapters have been established across the U.S. Levine himself resides in Los Angeles California (“Dharma Punx” 2014).

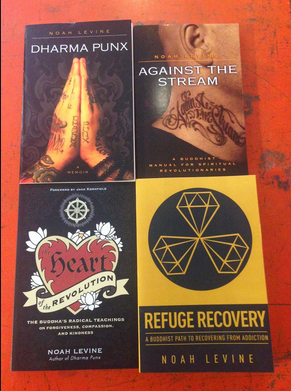

Body Awareness Project in 2000, which had the objective of teaching troubled youth mindfulness meditation and emotion coping strategies. In 2006, the organization was merged with a sister non-profit, and then in 2007, was merged again with Vision Youthz, an aftercare program for youth located in San Francisco. The three organizations have continued to work together in an effort to serve at-risk youth in the area. Levine currently serves on the Board of Directors (“Mind Body Awareness Project” n.d.). Levine went on to found the Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society in 2008 as a means of making Buddhist teachings accessible to everyone. The first center was located in Melrose, California, and about a year later the organization moved to Santa Monica. Subsequently, many chapters have been established across the U.S. Levine himself resides in Los Angeles California (“Dharma Punx” 2014). subsequent recovery. He describes his trips to monasteries in Asia and his later return to the juvenile hall where he was incarcerated, this time to teach meditation. In 2007, Levine published a second book, Against the Stream, that includes a variety of meditation techniques and instructions for both novices and skilled practitioners. He outlines a “path to freedom” The first stage, “The Rebel’s Path,” involves daily practice, an annual retreat, and following the five precepts. These practices and commitments are intensified in “The Revolutionary’s Path.” The culminating state, “The Radical’s Path,” involves an increased multi-year commitment and a willingness to teach others. His most recent book, Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Recovering from Addiction (2014), discusses the application of the Four Noble Truths and the Eight-Fold Path to the recovery program that he has created.

subsequent recovery. He describes his trips to monasteries in Asia and his later return to the juvenile hall where he was incarcerated, this time to teach meditation. In 2007, Levine published a second book, Against the Stream, that includes a variety of meditation techniques and instructions for both novices and skilled practitioners. He outlines a “path to freedom” The first stage, “The Rebel’s Path,” involves daily practice, an annual retreat, and following the five precepts. These practices and commitments are intensified in “The Revolutionary’s Path.” The culminating state, “The Radical’s Path,” involves an increased multi-year commitment and a willingness to teach others. His most recent book, Refuge Recovery: A Buddhist Path to Recovering from Addiction (2014), discusses the application of the Four Noble Truths and the Eight-Fold Path to the recovery program that he has created. (Preston 2009; “Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). The hippie subculture is dismissed as unrealistic; the hardcore punk subculture is deemed to be overly negative. Levine, along with Jack Kornfield, instead allies himself with emerging American Buddhism, which emphasizes relevance, accessibility, and applicability for contemporary Americans. Levine seeks a return to what he believes is the original, pure, core teachings of Buddhism contained in the Pali Sutta. For Levine, Siddhartha Gautama, who he refers to as “Sid,” was a revolutionary who taught anti-establishment rebellion and advocated a path of “Patisotagami,” that is, “against the stream” (“Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). Levine has adopted as his motto, “Meditate and Destroy” (dark thoughts).

(Preston 2009; “Against The Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). The hippie subculture is dismissed as unrealistic; the hardcore punk subculture is deemed to be overly negative. Levine, along with Jack Kornfield, instead allies himself with emerging American Buddhism, which emphasizes relevance, accessibility, and applicability for contemporary Americans. Levine seeks a return to what he believes is the original, pure, core teachings of Buddhism contained in the Pali Sutta. For Levine, Siddhartha Gautama, who he refers to as “Sid,” was a revolutionary who taught anti-establishment rebellion and advocated a path of “Patisotagami,” that is, “against the stream” (“Against the Stream Buddhist Meditation Society” n.d.). Levine has adopted as his motto, “Meditate and Destroy” (dark thoughts). for being unrealistic about the sacrifices that would be necessary to produce systemic change), conventional society (which he characterizes as corrupt), traditional Buddhism (which he assesses as having been corrupted). By contrast, Against the Stream is part of the New Buddhism that rejects traditional Buddhist practice in favor of a more contemporary, accessible, and attainable practice for present-day conditions. Levine symbolizes and embodies his oppositional stance and Buddhist commitments in part through extensive tattooing, which includes a large image of Buddha on his abdomen and a Buddhist wheel of existence covering his entire back (Swick 2010).

for being unrealistic about the sacrifices that would be necessary to produce systemic change), conventional society (which he characterizes as corrupt), traditional Buddhism (which he assesses as having been corrupted). By contrast, Against the Stream is part of the New Buddhism that rejects traditional Buddhist practice in favor of a more contemporary, accessible, and attainable practice for present-day conditions. Levine symbolizes and embodies his oppositional stance and Buddhist commitments in part through extensive tattooing, which includes a large image of Buddha on his abdomen and a Buddhist wheel of existence covering his entire back (Swick 2010). subcontinent under British rule, which added another dimension to religious debates taking place and to ongoing religious rivalries. This led to a number of different responses from Muslim thinkers, including from Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who began his carrier by writing tracts that argued in favor of Islam’s superiority as a religion (Khan 2015).

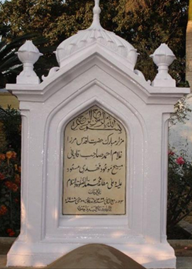

subcontinent under British rule, which added another dimension to religious debates taking place and to ongoing religious rivalries. This led to a number of different responses from Muslim thinkers, including from Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who began his carrier by writing tracts that argued in favor of Islam’s superiority as a religion (Khan 2015). to be another prophet after the Prophet Muhammad, who has generally been regarded as the last prophet in Islam (Friedmann 1989). Mirza Ghulam Ahmad spent the remaining years of his life engaged in a bitter controversy with other Muslims who rejected his claims. Ghulam Ahmad insisted that by following his interpretation of Islam, Muslims would be able to return to their former glory before the impending Day of Judgement. This messianic motif is responsible for providing Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya with its apocalyptic orientation in the broader Islamic tradition (Friedmann 1989).

to be another prophet after the Prophet Muhammad, who has generally been regarded as the last prophet in Islam (Friedmann 1989). Mirza Ghulam Ahmad spent the remaining years of his life engaged in a bitter controversy with other Muslims who rejected his claims. Ghulam Ahmad insisted that by following his interpretation of Islam, Muslims would be able to return to their former glory before the impending Day of Judgement. This messianic motif is responsible for providing Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya with its apocalyptic orientation in the broader Islamic tradition (Friedmann 1989). Muslims, and it is arguably the basis of the Ahmadi controversy today. The reason why this belief is considered to be so problematic by mainstream Muslims is because it appears to be a direct contradiction of the Qur’anic verse declaring Muhammad to be the “seal of the prophets ( khātam al-nabiyyīn )”, which has been understood by mainstream Muslims to indicate Muhammad’s status as the last prophet (Qur’an 33:40). Ahmadis, instead, have suggested that the verse should be understood to mean that Muhammad was the best of all previous prophets and that any subsequent prophet who might follow Muhammad would not establish new laws that contravened Islamic law in a way that would abrogate Islam and lead to the formation of a new religion (Friedmann 1989; Khan 2015). Ahmadis compare prophecy in Islam to the age of prophecy in ancient Judaism when numerous prophets were known to have appeared within the same religious tradition as a means of strengthening and revitalizing the tradition in anticipation of the Day of Judgment (Friedmann 1989).

Muslims, and it is arguably the basis of the Ahmadi controversy today. The reason why this belief is considered to be so problematic by mainstream Muslims is because it appears to be a direct contradiction of the Qur’anic verse declaring Muhammad to be the “seal of the prophets ( khātam al-nabiyyīn )”, which has been understood by mainstream Muslims to indicate Muhammad’s status as the last prophet (Qur’an 33:40). Ahmadis, instead, have suggested that the verse should be understood to mean that Muhammad was the best of all previous prophets and that any subsequent prophet who might follow Muhammad would not establish new laws that contravened Islamic law in a way that would abrogate Islam and lead to the formation of a new religion (Friedmann 1989; Khan 2015). Ahmadis compare prophecy in Islam to the age of prophecy in ancient Judaism when numerous prophets were known to have appeared within the same religious tradition as a means of strengthening and revitalizing the tradition in anticipation of the Day of Judgment (Friedmann 1989). apocalyptic expectations of the messiah to defeat evil in the world. Whereas the notion of jihad has always been used in Islam to signify various notions of inner and outer struggles, Ghulam Ahmad insisted that his mission would succeed through non-violent means (Hanson 2007). This concept of jihad, as representing an inner spiritual struggle, is certainly not unique to Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya, but the way in which it has been emphasized by Ahmadis, especially during the early years of the movement under British colonial rule, has developed into one of the hallmarks of Ahmadi Islam. Aside from the colonial context when Ahmadis refused to take up arms against the British, the notion of non-violent jihad has been particularly useful in marketing Ahmadi Islam to western audiences in a post 9/11 era (Khan 2015).

apocalyptic expectations of the messiah to defeat evil in the world. Whereas the notion of jihad has always been used in Islam to signify various notions of inner and outer struggles, Ghulam Ahmad insisted that his mission would succeed through non-violent means (Hanson 2007). This concept of jihad, as representing an inner spiritual struggle, is certainly not unique to Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya, but the way in which it has been emphasized by Ahmadis, especially during the early years of the movement under British colonial rule, has developed into one of the hallmarks of Ahmadi Islam. Aside from the colonial context when Ahmadis refused to take up arms against the British, the notion of non-violent jihad has been particularly useful in marketing Ahmadi Islam to western audiences in a post 9/11 era (Khan 2015). resulted in the creation of separate mosques and prayer facilities around the world and is somewhat unique in the Islamic tradition, where at least historically Muslims have largely avoided forming separate prayer congregations. There are of course some exceptions to this rule, especially in modernist South Asian Islam. Nonetheless, in the case of Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya, the separation in prayer is undeniable. This practice stems from the generalized assumption of Ahmadi congregants that a non-Ahmadi imam leading the prayer would likely consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad an infidel, and so Ahmadis choose to perform the same prayer ritual behind an Ahmadi imam. To illustrate the subtlety of this distinction, one might find non-Ahmadi Muslims who reject Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s claims performing the prayer behind an Ahmadi imam, especially in western countries where Muslim communities are diverse and prayer spaces are limited.

resulted in the creation of separate mosques and prayer facilities around the world and is somewhat unique in the Islamic tradition, where at least historically Muslims have largely avoided forming separate prayer congregations. There are of course some exceptions to this rule, especially in modernist South Asian Islam. Nonetheless, in the case of Jama‘at-i Ahmadiyya, the separation in prayer is undeniable. This practice stems from the generalized assumption of Ahmadi congregants that a non-Ahmadi imam leading the prayer would likely consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad an infidel, and so Ahmadis choose to perform the same prayer ritual behind an Ahmadi imam. To illustrate the subtlety of this distinction, one might find non-Ahmadi Muslims who reject Mirza Ghulam Ahmad’s claims performing the prayer behind an Ahmadi imam, especially in western countries where Muslim communities are diverse and prayer spaces are limited. the auxiliary organizations of the movement around the world and represents the centralization of both religious and political authority. He has the power to define or redefine both Ahmadi orthodoxy and Ahmadi orthopraxy (Khan 2015). The institution of Ahmadi khilāfat currently represents a stateless caliphate with branches of the movement in various countries throughout the world that make up the strata of the organizational hierarchy. Each nation with a local Ahmadi community (jama‘at) has a national representative known as an amīr (leader). The national amīr manages local branches, which are headed by a president. There are also subsidiary organizations for men and women that are subdivided by age group that fall within the jurisdiction of the president at the local level, or the amīr at the national level, as part of the hierarchical structure (Khan 2015). Ahmadi missionaries are responsible for spreading Ghulam Ahmad’s mission and will lead the prayer services at the local level while working with the president on local initiatives. Ahmadi missionaries often undergo basic religious training at various Ahmadi seminaries around the world before dedicating their lives to the movement.

the auxiliary organizations of the movement around the world and represents the centralization of both religious and political authority. He has the power to define or redefine both Ahmadi orthodoxy and Ahmadi orthopraxy (Khan 2015). The institution of Ahmadi khilāfat currently represents a stateless caliphate with branches of the movement in various countries throughout the world that make up the strata of the organizational hierarchy. Each nation with a local Ahmadi community (jama‘at) has a national representative known as an amīr (leader). The national amīr manages local branches, which are headed by a president. There are also subsidiary organizations for men and women that are subdivided by age group that fall within the jurisdiction of the president at the local level, or the amīr at the national level, as part of the hierarchical structure (Khan 2015). Ahmadi missionaries are responsible for spreading Ghulam Ahmad’s mission and will lead the prayer services at the local level while working with the president on local initiatives. Ahmadi missionaries often undergo basic religious training at various Ahmadi seminaries around the world before dedicating their lives to the movement. disagreement about the nature of the institutional hierarchy. The Lahori branch rejected the notion of a centralized supreme khalīfa and favored the formation of an administrative board known as the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore (Lahore Ahmadiyya Committee for the Propagation of Islam), which is headed by an amīr (Lavan 1974; Friedmann 1989). The amīr in the Lahori branch does not carry the same authoritative connotations as the khalīfat al-masīh in the larger Qadiani branch, even though he holds considerable authority in terms of guiding the administrative affairs of the branch nonetheless.

disagreement about the nature of the institutional hierarchy. The Lahori branch rejected the notion of a centralized supreme khalīfa and favored the formation of an administrative board known as the Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha‘at Islam Lahore (Lahore Ahmadiyya Committee for the Propagation of Islam), which is headed by an amīr (Lavan 1974; Friedmann 1989). The amīr in the Lahori branch does not carry the same authoritative connotations as the khalīfat al-masīh in the larger Qadiani branch, even though he holds considerable authority in terms of guiding the administrative affairs of the branch nonetheless. successors of the messiah have thus far been direct descendants of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. Expounding notions of charisma in relation to heredity, while accommodating other aspects of religious or political leadership and development, will need to be developed over time.

successors of the messiah have thus far been direct descendants of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad. Expounding notions of charisma in relation to heredity, while accommodating other aspects of religious or political leadership and development, will need to be developed over time. Montana before moving to Denver. On December 21, 1887 she married Kent White, an aspiring Methodist minister whom she had met in Montana in 1883. After completing his studies at University of Denver, he was ordained in 1889.

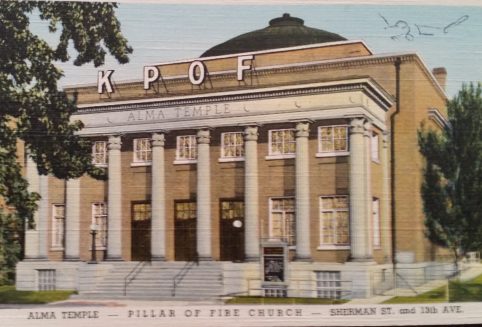

Montana before moving to Denver. On December 21, 1887 she married Kent White, an aspiring Methodist minister whom she had met in Montana in 1883. After completing his studies at University of Denver, he was ordained in 1889. Denver for her followers. Alma White purchased the property and supervised construction of the building, which seated 1,000 and had thirty-four bedrooms. Adopting the pattern of other Wesleyan/Holiness groups, she founded her own church, the Pentecostal Union on December 29, 1901 with fifty charter members. In 1902 Alma White participated in services in New England with the Burning Bush, the popular name of the Metropolitan Church Association, whose leaders she had met in Chicago the prior year. They cooperated in other services in Illinois, Iowa, California, Texas and London until they parted ways in a dispute over land in 1905. Alma White persevered, securing property in New Jersey. There, she established Zarephath, which replaced Denver as church headquarters in 1908.

Denver for her followers. Alma White purchased the property and supervised construction of the building, which seated 1,000 and had thirty-four bedrooms. Adopting the pattern of other Wesleyan/Holiness groups, she founded her own church, the Pentecostal Union on December 29, 1901 with fifty charter members. In 1902 Alma White participated in services in New England with the Burning Bush, the popular name of the Metropolitan Church Association, whose leaders she had met in Chicago the prior year. They cooperated in other services in Illinois, Iowa, California, Texas and London until they parted ways in a dispute over land in 1905. Alma White persevered, securing property in New Jersey. There, she established Zarephath, which replaced Denver as church headquarters in 1908. London. Arthur White (1889-1981), Alma’s son, stated in 1948, “some 50 branches of the society were organized” (Arthur White 1939:391). An unpublished list itemized 82 properties including buildings and lots purchased between 1902 and 1946. There were approximately 5,000 members at the church’s height. By 1940 the church sponsored eighteen private Christian schools throughout the United States. The outreach of Pillar of Fire extended to the acquisition of radio stations in Denver and New Jersey. Publications were also an important aspect of the church’s outreach. White wrote more than thirty-five books and edited six magazines. She played an active role in the leadership of the church, preaching until shortly before her death on June 26, 1946. Her son Arthur led the church until 1978 when his daughter, Arlene White Lawrence (1916–1990), took over, serving as president and general superintendent until 1984.

London. Arthur White (1889-1981), Alma’s son, stated in 1948, “some 50 branches of the society were organized” (Arthur White 1939:391). An unpublished list itemized 82 properties including buildings and lots purchased between 1902 and 1946. There were approximately 5,000 members at the church’s height. By 1940 the church sponsored eighteen private Christian schools throughout the United States. The outreach of Pillar of Fire extended to the acquisition of radio stations in Denver and New Jersey. Publications were also an important aspect of the church’s outreach. White wrote more than thirty-five books and edited six magazines. She played an active role in the leadership of the church, preaching until shortly before her death on June 26, 1946. Her son Arthur led the church until 1978 when his daughter, Arlene White Lawrence (1916–1990), took over, serving as president and general superintendent until 1984. also in the public arena. She promoted a standard definition of feminism: “In every sphere of life, whether social, political, or religious, there must be equality between the sexes” (“A Woman Bishop” 1922). Like other Christian feminists, she maintained that Jesus was “the great emancipator of the female sex.” Believing women’s equality was God’s will, she listed the religious and political equality of the sexes as a part of the Pillar of Fire creed (White 1935-1943 5:229). She documented a biblical precedent for her views, quoting from the story of Pentecost (Acts 2), Paul’s statement of equality in Galatians 3:28, and offering a litany of women in the Bible who operated outside the patriarchal women’s sphere. She supported suffrage for women. Pillar of Fire became the first religious group and one of the first organizations to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment when it was introduced by the National Woman’s Party in 1923. Alma White established the magazine Woman’s Chains in 1924 as a forum for her feminist message.

also in the public arena. She promoted a standard definition of feminism: “In every sphere of life, whether social, political, or religious, there must be equality between the sexes” (“A Woman Bishop” 1922). Like other Christian feminists, she maintained that Jesus was “the great emancipator of the female sex.” Believing women’s equality was God’s will, she listed the religious and political equality of the sexes as a part of the Pillar of Fire creed (White 1935-1943 5:229). She documented a biblical precedent for her views, quoting from the story of Pentecost (Acts 2), Paul’s statement of equality in Galatians 3:28, and offering a litany of women in the Bible who operated outside the patriarchal women’s sphere. She supported suffrage for women. Pillar of Fire became the first religious group and one of the first organizations to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment when it was introduced by the National Woman’s Party in 1923. Alma White established the magazine Woman’s Chains in 1924 as a forum for her feminist message. land, planted 25,000 fruit trees, laid miles of fence, planted wheat, oats, corn, and barley, and raised cattle, horses, sheep, and swine. By this time they had also erected a woolen mill (a logical choice, since several members had operated a mill in Germany), [Image at right] four saw mills, a flour mill, an oil mill, a calico print works, and a tannery, all of which were sources of revenue. In several small shops craftsmen produced brooms, baskets, tinware, ironware, barrels, wagons, furniture, shoes, clothing, and ceramics mostly for Community use. Each village had a butcher shop and bakery. The Community also raised grapes from which an ample quantity of wine was made, some for religious use but most for daily consumption, especially by men. The women’s roles were less diverse, but no less important. Women planted and tended the Community’s large gardens of beans, peas, potatoes, cabbage, cucumbers, and lettuce. They knitted and sewed certain items of clothing. Most significantly, they were in charge of preparing and serving the food, which they did in several communal kitchens and dining halls in each village.

land, planted 25,000 fruit trees, laid miles of fence, planted wheat, oats, corn, and barley, and raised cattle, horses, sheep, and swine. By this time they had also erected a woolen mill (a logical choice, since several members had operated a mill in Germany), [Image at right] four saw mills, a flour mill, an oil mill, a calico print works, and a tannery, all of which were sources of revenue. In several small shops craftsmen produced brooms, baskets, tinware, ironware, barrels, wagons, furniture, shoes, clothing, and ceramics mostly for Community use. Each village had a butcher shop and bakery. The Community also raised grapes from which an ample quantity of wine was made, some for religious use but most for daily consumption, especially by men. The women’s roles were less diverse, but no less important. Women planted and tended the Community’s large gardens of beans, peas, potatoes, cabbage, cucumbers, and lettuce. They knitted and sewed certain items of clothing. Most significantly, they were in charge of preparing and serving the food, which they did in several communal kitchens and dining halls in each village. addition of more members from Europe, the Inspirationists needed more land. High land prices and boisterous neighbors finally convinced Metz and the Elders that another move was needed to a less densely settled region. In 1854, an exploratory expedition discovered a nearly ideal spot. The new location, along the Iowa River twenty miles west of Iowa City, had excellent agricultural land, good water resources, ample timber, clay for brickmaking, and outcroppings of sandstone that could be used in building. The Community arranged to purchase nearly 18,000 contiguous acres of land from the government and from private owners, and early the following year sent out the first party of settlers. They cleared land, planted crops, and laid out the first village in July [Image at right] about three-quarters of a mile north of the river. They incorporated as the Amana Society, after a name in the Song of Solomon 4:8, essentially replicating the not-for-profit economic system they had created in New York.

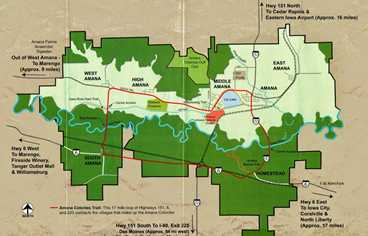

addition of more members from Europe, the Inspirationists needed more land. High land prices and boisterous neighbors finally convinced Metz and the Elders that another move was needed to a less densely settled region. In 1854, an exploratory expedition discovered a nearly ideal spot. The new location, along the Iowa River twenty miles west of Iowa City, had excellent agricultural land, good water resources, ample timber, clay for brickmaking, and outcroppings of sandstone that could be used in building. The Community arranged to purchase nearly 18,000 contiguous acres of land from the government and from private owners, and early the following year sent out the first party of settlers. They cleared land, planted crops, and laid out the first village in July [Image at right] about three-quarters of a mile north of the river. They incorporated as the Amana Society, after a name in the Song of Solomon 4:8, essentially replicating the not-for-profit economic system they had created in New York. their land: South Amana (1855) and Homestead (1861) on the south side of the Iowa River; and on the north side West Amana (1856), High Amana (1857), East Amana (1857), and Middle Amana (1862). [Image at right] The seven villages comprise the Amana Colonies, which until 1932 was co-terminus with the Amana Society. The religious enthusiasm which had characterized Ebenezer carried over to the Inspirationists’ early years in Iowa. They faced challenges, overcame hardships, and began to build a durable community.

their land: South Amana (1855) and Homestead (1861) on the south side of the Iowa River; and on the north side West Amana (1856), High Amana (1857), East Amana (1857), and Middle Amana (1862). [Image at right] The seven villages comprise the Amana Colonies, which until 1932 was co-terminus with the Amana Society. The religious enthusiasm which had characterized Ebenezer carried over to the Inspirationists’ early years in Iowa. They faced challenges, overcame hardships, and began to build a durable community. simple Amana cemetery [Image at right] he was accorded a singular distinction: his grave was allocated two of the customary burial plots. Under Landmann’s spiritual leadership, the Society concluded its basic building program, its land acquisition (to 26,000 acres, roughly the present tract), and its recruitment of new members from Europe. The Society attained its greatest population size and developed a vigorous economy.

simple Amana cemetery [Image at right] he was accorded a singular distinction: his grave was allocated two of the customary burial plots. Under Landmann’s spiritual leadership, the Society concluded its basic building program, its land acquisition (to 26,000 acres, roughly the present tract), and its recruitment of new members from Europe. The Society attained its greatest population size and developed a vigorous economy. economy and the bottom dropped out of the woolens market. Although dyestuffs again became available, the calico print works never reopened, the victim of changing clothing fashions. The Society went from a $7,000 net profit in 1922 to a $73,000 deficit in 1923, and recorded losses in every one of the next nine years. In 1923, a disastrous fire swept through the woolen mill [Image at right]. The lack of insurance (“God’s will be done”) put an enormous strain on the Society’s resources to rebuild it. The labor shortage and rising costs associated with hired labor contributed further to the Society’s insolvency. To make matters worse, selfishness and resentment began to show itself in some members, and malingering and dishonesty became more common.

economy and the bottom dropped out of the woolens market. Although dyestuffs again became available, the calico print works never reopened, the victim of changing clothing fashions. The Society went from a $7,000 net profit in 1922 to a $73,000 deficit in 1923, and recorded losses in every one of the next nine years. In 1923, a disastrous fire swept through the woolen mill [Image at right]. The lack of insurance (“God’s will be done”) put an enormous strain on the Society’s resources to rebuild it. The labor shortage and rising costs associated with hired labor contributed further to the Society’s insolvency. To make matters worse, selfishness and resentment began to show itself in some members, and malingering and dishonesty became more common.

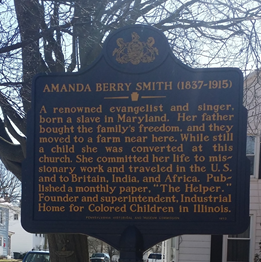

freedom and later the freedom of his wife, Mariam Matthews Berry and five children. Amanda’s father was active in the Underground Railroad and their home served as a prominent station. She grew up in Maryland and central Pennsylvania, often working as a servant in other people’s homes. Her formal education consisted of three-months’ schooling. Her parents taught her to read and write. Amanda Berry married Calvin Devine in September 1854. They had one child, Mazie, who was her only child to live to adulthood. Calvin Devine died while serving in the Civil War. Amanda Berry Devine moved to Philadelphia where she continued to do housework and cooking for others. There she met James Smith whom she married in 1865. They moved to New York City where she took in people’s washing and cleaned houses. James Smith died in November 1869, and Amanda Berry Smith never remarried.

freedom and later the freedom of his wife, Mariam Matthews Berry and five children. Amanda’s father was active in the Underground Railroad and their home served as a prominent station. She grew up in Maryland and central Pennsylvania, often working as a servant in other people’s homes. Her formal education consisted of three-months’ schooling. Her parents taught her to read and write. Amanda Berry married Calvin Devine in September 1854. They had one child, Mazie, who was her only child to live to adulthood. Calvin Devine died while serving in the Civil War. Amanda Berry Devine moved to Philadelphia where she continued to do housework and cooking for others. There she met James Smith whom she married in 1865. They moved to New York City where she took in people’s washing and cleaned houses. James Smith died in November 1869, and Amanda Berry Smith never remarried. Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1875, shortly after it was organized. She played an active role in its meetings, both in the United States and later in England. In Liberia, she urged her listeners to sign a pledge to forego drinking alcohol and organized temperance societies. After eight years, she left Africa, visiting England, Scotland, and Ireland for several months before returning to the United States in September 1890. She maintained her dual emphases on temperance and evangelism, preaching at camp meetings and churches. She traveled to California and Canada before traveling to Great Britain and Ireland in 1893.

Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1875, shortly after it was organized. She played an active role in its meetings, both in the United States and later in England. In Liberia, she urged her listeners to sign a pledge to forego drinking alcohol and organized temperance societies. After eight years, she left Africa, visiting England, Scotland, and Ireland for several months before returning to the United States in September 1890. She maintained her dual emphases on temperance and evangelism, preaching at camp meetings and churches. She traveled to California and Canada before traveling to Great Britain and Ireland in 1893.

pastor. Zwingli was popular, and many hoped that he would move quickly to do away with all rituals for which there was not a clear scriptural basis. Nevertheless, Zwingli felt that secular authority should guide reform, and he refused to proceed without the consent of the Zurich City Council, which had taken charge of the church. Zwingli’s decision seemed to privilege secular authority over scriptural and angered several of his young students, most particularly Conrad Grebel (ca.1498-1526), the son of a prominent Zurich family; Felix Manz (ca. 1498–January 5, 1527), another well-educated Zurich native; and Georg Blaurock (ca. 1492-September 6, 1529), a former priest. The conflict between students and teacher ultimately came to a head over the issue of infant baptism, a practice that not only had religious significance but also helped to ensure that children were entered into state records. In other words, it served a secular purpose as well as a religious one, creating both church members and citizens of the state. Grebel, Manz, Blaurock and their followers argued that, because infant baptism was not mentioned in scripture, it had no place in the church. They asserted baptism should be undertaken as a sign of one’s commitment to the church. Further, they argued, the church should be a believers’ church, a position that many in authority feared would bring anarchy. In January, 1525, the Zurich City Council enacted laws requiring that infants be baptized and forbidding the rebaptism of those who had been baptized as infants. In response, Grebel, Manz and Blaurock, rebaptized each other and launched the Anabaptist movement (Hostetler 1993; Hurst & McConnell 2010); Johnson-Weiner 2010; Kraybill et al 2013; Loewen and Nolt 1996; Nolt 2016).

pastor. Zwingli was popular, and many hoped that he would move quickly to do away with all rituals for which there was not a clear scriptural basis. Nevertheless, Zwingli felt that secular authority should guide reform, and he refused to proceed without the consent of the Zurich City Council, which had taken charge of the church. Zwingli’s decision seemed to privilege secular authority over scriptural and angered several of his young students, most particularly Conrad Grebel (ca.1498-1526), the son of a prominent Zurich family; Felix Manz (ca. 1498–January 5, 1527), another well-educated Zurich native; and Georg Blaurock (ca. 1492-September 6, 1529), a former priest. The conflict between students and teacher ultimately came to a head over the issue of infant baptism, a practice that not only had religious significance but also helped to ensure that children were entered into state records. In other words, it served a secular purpose as well as a religious one, creating both church members and citizens of the state. Grebel, Manz, Blaurock and their followers argued that, because infant baptism was not mentioned in scripture, it had no place in the church. They asserted baptism should be undertaken as a sign of one’s commitment to the church. Further, they argued, the church should be a believers’ church, a position that many in authority feared would bring anarchy. In January, 1525, the Zurich City Council enacted laws requiring that infants be baptized and forbidding the rebaptism of those who had been baptized as infants. In response, Grebel, Manz and Blaurock, rebaptized each other and launched the Anabaptist movement (Hostetler 1993; Hurst & McConnell 2010); Johnson-Weiner 2010; Kraybill et al 2013; Loewen and Nolt 1996; Nolt 2016). interact with and even marry non-Mennonites, and he chastised congregations for their apparent failure to shun expelled members. Most of the Mennonite preachers and congregations in Switzerland and the Palatinate region rejected Amman’s call for greater separation from the world, and so, in 1693, Amman excommunicated them. Twenty of the twenty-three Alsatian ministers, along with one in the Palatinate and five in Germany, supported Amman. They and their congregations became known as Amish Mennonites, or, simply, Amish (Nolt 2016).

interact with and even marry non-Mennonites, and he chastised congregations for their apparent failure to shun expelled members. Most of the Mennonite preachers and congregations in Switzerland and the Palatinate region rejected Amman’s call for greater separation from the world, and so, in 1693, Amman excommunicated them. Twenty of the twenty-three Alsatian ministers, along with one in the Palatinate and five in Germany, supported Amman. They and their congregations became known as Amish Mennonites, or, simply, Amish (Nolt 2016). the Ausbunds (hymnbooks) are put out on the benches as well.

the Ausbunds (hymnbooks) are put out on the benches as well. regulates much of daily life. While church members will acknowledge that not everything in the Ordnung is scripturally based, what cannot be supported by reference to the Bible is justified by the feeling that to do otherwise would be worldly and disruptive to the community.

regulates much of daily life. While church members will acknowledge that not everything in the Ordnung is scripturally based, what cannot be supported by reference to the Bible is justified by the feeling that to do otherwise would be worldly and disruptive to the community. appliance saves the owner time does not necessarily recommend it, nor does it being “modern” condemn it. The question is simply how it will affect the church-community. Most Amish communities use some battery-powered devices, notably flashlights, as well as diesel motors. Some Amish communities have even permitted solar power. Nevertheless, all have determined that connecting the Amish home to power lines “could lead to many temptations and the deterioration of church and family life” (Hostetler 1993; Hurst and McConnell 2010; Johnson-Weiner 2010; Kraybill 2001; Kraybill et al 2013; Nolt 2016; Nolt and Meyers 2007).

appliance saves the owner time does not necessarily recommend it, nor does it being “modern” condemn it. The question is simply how it will affect the church-community. Most Amish communities use some battery-powered devices, notably flashlights, as well as diesel motors. Some Amish communities have even permitted solar power. Nevertheless, all have determined that connecting the Amish home to power lines “could lead to many temptations and the deterioration of church and family life” (Hostetler 1993; Hurst and McConnell 2010; Johnson-Weiner 2010; Kraybill 2001; Kraybill et al 2013; Nolt 2016; Nolt and Meyers 2007). public schools, most attend small one or two-room schoolhouses in their own communities, where they are taught by teachers of their own faith [See photograph of Amish school at right]. While teachers’ meetings in many communities provide teachers with some training and support, in the most conservative Amish settlements, teachers are likely to be young, unmarried, girls from the community with little or no formal training. In their eight years of formal education, Amish children learn English, arithmetic, German, and maybe geography and health. The important lessons (how to manage the farm and the household, how to raise the children, how to be responsible and work hard) are learned at home, where children participate in work, play, and ceremony to the extent of their abilities (Dewalt 2006; Johnson-Weiner 2007).

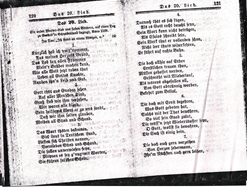

public schools, most attend small one or two-room schoolhouses in their own communities, where they are taught by teachers of their own faith [See photograph of Amish school at right]. While teachers’ meetings in many communities provide teachers with some training and support, in the most conservative Amish settlements, teachers are likely to be young, unmarried, girls from the community with little or no formal training. In their eight years of formal education, Amish children learn English, arithmetic, German, and maybe geography and health. The important lessons (how to manage the farm and the household, how to raise the children, how to be responsible and work hard) are learned at home, where children participate in work, play, and ceremony to the extent of their abilities (Dewalt 2006; Johnson-Weiner 2007). scripture is the final authority. Amish church services are conducted in German, and all Amish sing from the Ausbund [See scan of pages from Ausbund at right], a hymnbook first printed in 1564 that contains songs written by early Anabaptists. The Lobelied, a hymn of praise, is always the second song in the service, but more conservative congregations sing it far more slowly than more progressive ones. The Ausbund does not contain melodies for the songs, and tunes are passed down from one generation to the next, further uniting the community (Hostetler 1993; Kraybill et al 2013).

scripture is the final authority. Amish church services are conducted in German, and all Amish sing from the Ausbund [See scan of pages from Ausbund at right], a hymnbook first printed in 1564 that contains songs written by early Anabaptists. The Lobelied, a hymn of praise, is always the second song in the service, but more conservative congregations sing it far more slowly than more progressive ones. The Ausbund does not contain melodies for the songs, and tunes are passed down from one generation to the next, further uniting the community (Hostetler 1993; Kraybill et al 2013). possessing extraordinary powers. According to these accounts, the signs of Sudhamani’s future spirituality began prior to her birth. During pregnancy her mother “began having strange visions. Sometimes she had wonderful dreams of Lord Krishna. At others she beheld the divine play of Lord Shiva and Devi, the Divine Mother” (Amritaswarupanada 1994:13). When Sudhamani was born she had a dark blue complexion and would lay in the lotus position of hatha yoga (chinmudra). By the time that she was six months old “she began speaking in her native tongue, and at the age of two began singing devotional songs to Sri Krishna…[E]even at an early age Sudhamani exhibited certain mystical and suprahuman traits, including compassion for the destitute. In her late teens, she developed an intense devotion to and longing for Krishna…sometimes she danced in spiritual ecstasy, and at other times she wept bitterly at the separation from her beloved Krishna” (Raj 2004:206). Sudhanami reportedly was so absorbed with Lord Krishna that “If she suddenly realized she had taken several steps without remembering Krishna, she would run back and walk those steps again, repeating the Lord’s name” (Johnsen 1994:95).

possessing extraordinary powers. According to these accounts, the signs of Sudhamani’s future spirituality began prior to her birth. During pregnancy her mother “began having strange visions. Sometimes she had wonderful dreams of Lord Krishna. At others she beheld the divine play of Lord Shiva and Devi, the Divine Mother” (Amritaswarupanada 1994:13). When Sudhamani was born she had a dark blue complexion and would lay in the lotus position of hatha yoga (chinmudra). By the time that she was six months old “she began speaking in her native tongue, and at the age of two began singing devotional songs to Sri Krishna…[E]even at an early age Sudhamani exhibited certain mystical and suprahuman traits, including compassion for the destitute. In her late teens, she developed an intense devotion to and longing for Krishna…sometimes she danced in spiritual ecstasy, and at other times she wept bitterly at the separation from her beloved Krishna” (Raj 2004:206). Sudhanami reportedly was so absorbed with Lord Krishna that “If she suddenly realized she had taken several steps without remembering Krishna, she would run back and walk those steps again, repeating the Lord’s name” (Johnsen 1994:95). by a female disciple who performs the ritual foot worship (pada puja) by sprinkling water on Ammachi’s feet, then placing sandal paste and flowers on them. Two monks recite from the Sanskritic slokas, followed by the ceremonial waving of a lamp. Another devotee decorates Ammachi with a garland. There is a lecture on Ammachi’s message and spirituality. Finally, Ammachi and an Indian band lead the devotional singing (bhajan). After a period of meditation, Ammachi’s devotees are invited to approach her individually for her trademark embrace.

by a female disciple who performs the ritual foot worship (pada puja) by sprinkling water on Ammachi’s feet, then placing sandal paste and flowers on them. Two monks recite from the Sanskritic slokas, followed by the ceremonial waving of a lamp. Another devotee decorates Ammachi with a garland. There is a lecture on Ammachi’s message and spirituality. Finally, Ammachi and an Indian band lead the devotional singing (bhajan). After a period of meditation, Ammachi’s devotees are invited to approach her individually for her trademark embrace. Amma embraces or kisses someone, it is a process of purification and inner healing. Amma is transmitting a part of Her pure vital energy into Her children. It also allows them to experience unconditional love. When Amma holds someone it can help to awaken the dormant spiritual energy within them, which will eventually take them to the ultimate goal of Self-realization” (Raj 2005:136-7). One of Ammachi’s devotees communicates the power of this encounter as follows: “Ammachi gives all the time, twenty four hours a day…She lavishes her love freely on everyone who comes to her. She may be firm with them, but she always radiates unconditional love. That’s why people are so shaken after they meet her. She’s a living example of what she teaches, of what all the scriptures teach” (Johnsen 1994:100).