COMMUNITY OF TRUE INSPIRATION/AMANA SOCIETY TIMELINE

1714: Radical Pietists Eberhard Ludwig Gruber and Johann Friedrich Rock established the Community of True Inspiration in Hessen, Germany. Rock became divinely inspired; Gruber could discern true from false inspiration.

1714-1716: Seven other inspired instruments appeared which the group accepted, though only Rock remained inspired for more than two years.

1728: Eberhard Ludwig Gruber died.

1749: Johann Friedrich Rock died, and leadership passed to lay Elders.

1817-1819: A “Reawakening” of the group began with three new instruments: Michael Krausert, Barbara Heinemann, and Christian Metz.

1819: Krausert lost his inspiration and left the group.

1823: Against the advice of the elders, Heinemann married and spontaneously lost her inspiration, leaving Metz the only instrument.

1830s: In response to persecution of the group, Metz began to gather some of the dispersed members onto rented estates in Germany, where they initiated more collectivistic living.

1843: Metz led 700 members to the United States, where they established the communal Ebenezer Society in upstate New York, its economy based on agriculture and light manufacturing.

1849: Barbara Heinemann Landmann regained her inspiration.

1854-1861: The Community relocated all members to Iowa, establishing the Amana Society and continuing communal life based on agriculture and manufacturing.

1860-1884: Additional members joined from Germany and Switzerland, and Amana’s population peaked at around 1,800 members in the early 1880s.

1867: Christian Metz died at Amana.

1883: Barbara Landmann died at Amana, and leadership passed to the Elders.

1923: A disastrous fire in the woolen mill and flour mill economically weakened the Society.

1932: Members of the community voted to abandon communalism and reorganize the Society as a joint-stock corporation. The Amana Church Society separated from the community’s business functions.

1960: The Amana Church Society began offering church services in English as well as German. The process of translating religious texts into English began.

1960-1980: Tourism became a significant factor in Amana’s economy.

1980-2000: All religious services switched to mainly English.

2014: Amana celebrated the 300 th anniversary of the founding of the Community of True Inspiration.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The name “Amana Society” has two referents: (1) a religiously-based and not-for-profit communal society that existed from 1855 to 1932 in east-central Iowa, which will be referred to here as Amana Society (I), and (2) a successor organization, in the same location, structured as a for-profit joint-stock corporation without religious dimensions that has existed from 1932 to the present, which will be referred to here as Amana Society (II). In 1932, the religious functions of Amana Society (I) were separated from the business functions and incorporated under a new name, Amana Church Society. Further confusing the history, the Amana Society (I) was essentially a new name for a new location of the Ebenezer Society that existed near Buffalo, New York, from 1843 to 1862, whose members began relocating to Amana in 1855. The roots of the Ebenezer Society, in turn, can be traced back to 1714 in Hessen, Germany, where a group that eventually took the name Die Gemeinde der wahren Inspirations (The Community of True Inspiration) broke away from the state-sponsored Evangeliche Kirche (the Lutheran Church) under the influence of Radical Pietism. This 300 year history, seen by modern residents of Amana as continuous, even though punctuated, does not drop neatly into a single group label, complicating the effort to designate the group’s founder, doctrines, rituals, and organization, which differ at different periods in the group’s history.

The Community of True Inspiration was one of many small sects which appeared early in the eighteenth century under the influence of Pietist criticisms of the state church in Germany. Its founders, a former Lutheran minister (Eberhard Ludwig Gruber), and a saddle maker (Johann Friedrich Rock), came originally from Wuerttemberg, but in 1707 they moved to Himbach, in Hessen, where they could enjoy a greater degree of religious freedom due to the liberal inclinations of the Count of Ysenburg. Gruber and Rock were Separatists who favored simple and direct Christian worship without the accoutrements of ritual, clergy, or church. All one needed, they believed, was to humble oneself before God, pray earnestly, and study the Bible, alone or with other pious people.

Gruber and Rock belonged to a nascent prayer-assembly in Himbach of the sort known in Separatist circles as a “conventicle.” Its members gathered to pray together in one another’s homes, activated by no creed except for what was taught in the Bible. Though heartfelt, the association was a fragile one, periodically disrupted by differences of opinion and personal animosity that more than once caused Gruber and the others to despair about the possibility of sustained and meaningful spiritual fellowship.

Into this setting, in mid-November 1714, came a small group of followers of the doctrine of inspirationism. A belief in inspiration (that is, in the possibility that human beings can receive divine communications through the agency of the Holy Spirit) surfaced in slightly different forms from time to time in European history. The variant which reached Gruber and his neighbors appears to have originated late in the seventeenth century in the Cevennes region of France, where the Camisards or French Prophets, believers in inspiration, waged an unsuccessful war for religious freedom against the French crown following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. Following their defeat, a handful of their inspired leaders fled to England, where they influenced Quakerism, and then to the Continent. They traveled widely, preaching in inspiration about the impending millenium and promising redemption for those who practiced a simple form of Christian piety. Among those touched by their message were three brothers from Saxony, who in June 1714 took up the life of wandering prophets and delivered inspired warnings to whoever would hear them. In mid-October, the brothers reached the Ysenburg area, creating a sensation among the Separatists and dissidents who had settled there.

Gruber and Rock at first were dubious, but when they finally met the prophets they were won over to a belief in inspiration. The following day, November 16, 1714, Gruber hosted the prayer-assembly which founded the Community of True Inspiration. Within several months, eight individuals had acquired the gift of inspiration, including Rock, three women, and four other men, among them Gruber’s son, Johann Adam Gruber. Proclaimed as Werkzeuge (instruments) of God, they, too, took up the call to proselytize. The instruments travelled throughout Germany and into Switzerland, Bohemia, and Silesia. Wherever they went they were accompanied by scribes who recorded their inspired words for dissemination to others. Their testimonies (Bezeugungen) contained homiletic and exhortatory messages to “awaken” people from their spiritual slumber. Audiences were urged to cast aside their sinful ways, dedicate themselves to doing God’s will, and prepare for the heavenly kingdom by obeying the teachings of Scripture. They were told they could dispense with the organized church, the rote performance of rituals, and unrighteous ministers. Those who felt the call of the instruments most strongly joined the Community of True Inspiration.

Although the instruments traveled widely, the Ysenburg area and the nearby Principality of Wittgenstein remained the center of Inspirationist life. Most of the congregations and most of the members were there. Even in these more tolerant areas, however, the Inspirationists were occasionally harassed by the authorities, and elsewhere the instruments faced imprisonment, floggings, and fines for their activities and, along with entire congregations, were banished from some towns and districts. The persecutions proved too much for some members, whose initial enthusiasm was suffocated by the realities of the abuse they suffered at the hands of jealous clergy and apprehensive town councils. Those who remained faithful explained the apostates’ “fall from grace” as a failure of will or a succumbing to the temptations of Satan. Even the instruments experienced self-doubt or found the leadership demands placed on them too great to bear. In the end, all of them apostatized save Rock.

Eberhard Ludwig Gruber and Johann Friedrich Rock remained steadfast, and it was they, more than anyone else, who sustained the Community through its difficult early years to a time of relative stability by 1720. Kept by old age from extensive travel, Gruber remained the spiritual heartbeat of the Community until his death in 1728, whereupon to Rock fell the task of stoking the fires of religious enthusiasm that he and the other instruments had kindled. During this period the Community grew more slowly than in the early years of the awakening, for there was much to do simply to meet the needs of the existing congregations. Rock travelled among them, exhorting the members to lead pure and humble lives, overseeing where possible their annual spiritual examination, and proselytizing where he could. In these efforts he was assisted by many gifted and capable lay Elders, and following his death in 1749 they carried on in the absence of any inspired instruments for the next fifty years. By 1800, however, the Community was clearly on the wane. A few vigorous congregations remained, but most had shrunken away to only a few families, and a few had disappeared altogether.

Providentially, the history says, in 1817 a young spiritual seeker by the name of Michael Krausert sought out one of the remaining Inspirationist congregations in search of an explanation for the curious spiritual stirrings he felt. Two of the congregation’s Elders questioned him closely and came to the conclusion that Krausert was experiencing manifestations of divine inspiration, about which they had only read in the writings of Gruber. They acknowledged Krausert as an instrument, a mantle that he accepted, and thereby initiated the period in Inspirationist history known as the Reawakening.

Krausert’s inspiration cleaved the remaining Inspirationist congregations in two. Neither the sceptics nor those ready to accept him had ever witnessed inspiration. Their respective attitudes depended more on hope versus doubt, or on their level of confidence in the two elders, than on Krausert’s own qualities, but that his inspired pronouncements animated many members is certain. In general, these were the younger members. They had not yet had time to grow over-accustomed to old patterns, had not yet had time to settle serenely into an undemanding religious life. Where it became necessary, they separated from the sceptics, and even from their parents, to establish new congregations.

The enthusiasm which Krausert sparked, like that generated by the three brothers from Saxony a century earlier, soon produced other instruments. Barbara Heinemann was an illiterate Alsatian chamber maid who, like Krausert, was directed by acquaintances to an Inspirationist congregation after experiencing unaccountable visions. She came in 1818 and met Krausert, who prophesied that she would soon come fully under the influence of the spirit and speak out in inspiration, which shortly came to pass. Next was a young carpenter by the name of Christian Metz, who experienced a spiritual reawakening and was invited to travel with Krausert and Heinemann to help rekindle enthusiasm in the congregations. Heinemann prophesied Metz’s inspiration, and it came, but at first only as a brief flicker before being suffocated by dissention within the new Community.

In the summer of 1819 Krausert publicly began to question Heinemann’s inspiration, and she his. Metz chose not to take sides but to entreat God in prayer for a resolution. A potentially disastrous outcome was averted when Krausert acknowledged that he had grown uncertain of his inspiration, whereupon he lost the power and withdrew from the community. Then, in 1822, Heinemann fell in love with and wanted to marry another member by the name of Georg Landmann. The elders opposed the match; it was not appropriate for an instrument of God to marry. Heinemann acquiesced for a time, but in the spring of 1823 her willpower faltered. She ceased being moved by the inspirational spirit and married Landmann; banished by the elders, she nevertheless remained faithful to the Community and, with her husband, was soon readmitted. Fortunately for the Community, Metz’s power of inspiration returned shortly after this, and he emerged as the central figure of the Reawakening. Like Rock in the previous century, he never married.

Metz continued the process of contacting the old congregations in Germany, Switzerland, and Alsace, and the members ready to accept his leadership formed new congregations. (Almost without exception, the congregations which did not accept the new leaders soon dissolved.) The heightened activity of the congregations, and especially Metz’s preaching and proselytizing, once again aroused the unfavorable attention of church and civil authorities, and persecution began anew. In 1826, the Inspirationists were expelled from Schwarzenau, in the province of Wittgenstein, one of the group’s original centers. Under the pressure of this incident, Metz conceived a plan to gather persecuted members to several estates in the religiously tolerant Grand Duchy of Hessen-Darmstadt. The Inspirationists who settled on these estates were segregated from the wider society to a greater degree than before, and they were also economically more interdependent. Many of them worked in factories established by merchants in the Community under the guidance of Metz and the Elders. The leaders arranged work opportunities for them, and in general the level of sharing in their lives increased.

In 1843, Metz and three companions sailed to New York City and began to search for a suitable location, ultimately buying 5,000 acres of the former Seneca Indian Reservation near Buffalo, New York. Nearly 700 members from the estates and various congregations relocated during the first year, with others following as their circumstances allowed. The Inspirationists called their new home Ebenezer, named for a stone erected by the biblical Samuel to mark the terminus of his people’s wanderings. The Community incorporated as a religious association under the laws of the State of New York as “the Ebenezer Society” and established four villages. A few years later, through the accession of new members, the Community acquired land in Canada, and two small villages were added there.

For several years, the Inspirationists wrestled with the question of how the economic life of the Community should be organized. Was it better to implement a version of the system used on the estates in Germany, whereby each family was financially independent within an economic context of cooperatively-owned or even privately-owned businesses? Or would it be preferable to link the members even more closely by eliminating wages and private property in exchange for guaranteed work and cradle-to-grave security? Each alternative had attractive features, and each had its advocates. Some members voiced strong opposition to collectivization, but Metz made clear in several inspired testimonies that it was God’s will to adopt a system whereby all the property except small personal possessions would be owned and worked in common.

The Inspirationists developed a diverse and productive economic base in Ebenezer. By 1847, they had cleared 3,000-4,000 acres of land, planted 25,000 fruit trees, laid miles of fence, planted wheat, oats, corn, and barley, and raised cattle, horses, sheep, and swine. By this time they had also erected a woolen mill (a logical choice, since several members had operated a mill in Germany), [Image at right] four saw mills, a flour mill, an oil mill, a calico print works, and a tannery, all of which were sources of revenue. In several small shops craftsmen produced brooms, baskets, tinware, ironware, barrels, wagons, furniture, shoes, clothing, and ceramics mostly for Community use. Each village had a butcher shop and bakery. The Community also raised grapes from which an ample quantity of wine was made, some for religious use but most for daily consumption, especially by men. The women’s roles were less diverse, but no less important. Women planted and tended the Community’s large gardens of beans, peas, potatoes, cabbage, cucumbers, and lettuce. They knitted and sewed certain items of clothing. Most significantly, they were in charge of preparing and serving the food, which they did in several communal kitchens and dining halls in each village.

land, planted 25,000 fruit trees, laid miles of fence, planted wheat, oats, corn, and barley, and raised cattle, horses, sheep, and swine. By this time they had also erected a woolen mill (a logical choice, since several members had operated a mill in Germany), [Image at right] four saw mills, a flour mill, an oil mill, a calico print works, and a tannery, all of which were sources of revenue. In several small shops craftsmen produced brooms, baskets, tinware, ironware, barrels, wagons, furniture, shoes, clothing, and ceramics mostly for Community use. Each village had a butcher shop and bakery. The Community also raised grapes from which an ample quantity of wine was made, some for religious use but most for daily consumption, especially by men. The women’s roles were less diverse, but no less important. Women planted and tended the Community’s large gardens of beans, peas, potatoes, cabbage, cucumbers, and lettuce. They knitted and sewed certain items of clothing. Most significantly, they were in charge of preparing and serving the food, which they did in several communal kitchens and dining halls in each village.

In 1849, Metz prophesied that Barbara Heinemann Landmann would again receive the gift of inspiration. In light of Landmann’s married status this was a surprising pronouncement, not triggered by any obvious need or change. It shortly came to pass, and for the next twenty years Landmann and Metz together imparted God’s messages to the Community, though she appears to have deferred to his “higher gift.” After Metz’s death, Landmann experienced resistance from some of the Elders, but never outright rebellion.

The economic success of Ebenezer was due in part to the proximity of Buffalo and its markets, but the city’s growth threatened to engulf the Community in a sea of worldliness. Further, as Ebenezer’s population increased to over 1,000, mostly due to the addition of more members from Europe, the Inspirationists needed more land. High land prices and boisterous neighbors finally convinced Metz and the Elders that another move was needed to a less densely settled region. In 1854, an exploratory expedition discovered a nearly ideal spot. The new location, along the Iowa River twenty miles west of Iowa City, had excellent agricultural land, good water resources, ample timber, clay for brickmaking, and outcroppings of sandstone that could be used in building. The Community arranged to purchase nearly 18,000 contiguous acres of land from the government and from private owners, and early the following year sent out the first party of settlers. They cleared land, planted crops, and laid out the first village in July [Image at right] about three-quarters of a mile north of the river. They incorporated as the Amana Society, after a name in the Song of Solomon 4:8, essentially replicating the not-for-profit economic system they had created in New York.

addition of more members from Europe, the Inspirationists needed more land. High land prices and boisterous neighbors finally convinced Metz and the Elders that another move was needed to a less densely settled region. In 1854, an exploratory expedition discovered a nearly ideal spot. The new location, along the Iowa River twenty miles west of Iowa City, had excellent agricultural land, good water resources, ample timber, clay for brickmaking, and outcroppings of sandstone that could be used in building. The Community arranged to purchase nearly 18,000 contiguous acres of land from the government and from private owners, and early the following year sent out the first party of settlers. They cleared land, planted crops, and laid out the first village in July [Image at right] about three-quarters of a mile north of the river. They incorporated as the Amana Society, after a name in the Song of Solomon 4:8, essentially replicating the not-for-profit economic system they had created in New York.

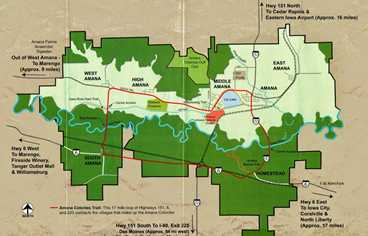

During the next seven years, as more members arrived from Ebenezer and Germany, the Inspirationists built six more villages on their land: South Amana (1855) and Homestead (1861) on the south side of the Iowa River; and on the north side West Amana (1856), High Amana (1857), East Amana (1857), and Middle Amana (1862). [Image at right] The seven villages comprise the Amana Colonies, which until 1932 was co-terminus with the Amana Society. The religious enthusiasm which had characterized Ebenezer carried over to the Inspirationists’ early years in Iowa. They faced challenges, overcame hardships, and began to build a durable community.

their land: South Amana (1855) and Homestead (1861) on the south side of the Iowa River; and on the north side West Amana (1856), High Amana (1857), East Amana (1857), and Middle Amana (1862). [Image at right] The seven villages comprise the Amana Colonies, which until 1932 was co-terminus with the Amana Society. The religious enthusiasm which had characterized Ebenezer carried over to the Inspirationists’ early years in Iowa. They faced challenges, overcame hardships, and began to build a durable community.

Christian Metz died in 1867 at the age of 72. Exhausted by his countless trips in Europe and between Ebenezer and Amana, never free from worry about the “inner and outer condition” of the Community, he at least lived to see his followers comfortably settled in a secure spot where they could work out their collective destiny with a minimum of outside interference. Much esteemed for his leadership and beloved for his patience and kindness, his death was a blow to the Inspirationists. Several hundred members attended his funeral in Amana, and when he was buried in the simple Amana cemetery [Image at right] he was accorded a singular distinction: his grave was allocated two of the customary burial plots. Under Landmann’s spiritual leadership, the Society concluded its basic building program, its land acquisition (to 26,000 acres, roughly the present tract), and its recruitment of new members from Europe. The Society attained its greatest population size and developed a vigorous economy.

simple Amana cemetery [Image at right] he was accorded a singular distinction: his grave was allocated two of the customary burial plots. Under Landmann’s spiritual leadership, the Society concluded its basic building program, its land acquisition (to 26,000 acres, roughly the present tract), and its recruitment of new members from Europe. The Society attained its greatest population size and developed a vigorous economy.

Landmann’s death in 1883 proved to be the “seal of inspiration” in the Community of True Inspiration. Only a handful of Elders remained from the time of the Reawakening, and in a few years they too were gone. The governance of Amana then fell completely to younger men who had never known the Community without Werkzeuge. They were a remarkably capable group in every sense. Many of them had reached maturity in Ebenezer and showed a deep and abiding dedication to Inspirationism. They were also experienced and competent businessmen, and under their leadership the Society was debt-free and economically sound.

In 1883, the Amana Society was still relatively isolated from the rest of the world. Most of the outsiders who came to the Colonies were businessmen, with whom ordinary members had little contact, or neighboring farmers, whose material way of life differed little from that of the Inspirationists, and indeed probably was inferior to theirs. The Community subscribed to several periodicals, but for the most part these were “wholesome” German-language publications “for the family” or technical journals. Members were not allowed to leave the Colonies without permission, a rule relatively easy to enforce because the members had no cash and the Society’s conveyances were under close supervision. The Elders busied themselves with problems of job assignments, marketing the Society’s products, leading the members in worship, and routinely inveighing against “worldly amusements.”

As the century waned, however, the outside world made more and more inroads into the Colonies. Mail-order catalogs appeared from some of the companies with which the Society did business. Tourists arrived, at first by one’s and two’s and later on rail excursions organized from neighboring cities. It is a measure of Amana’s conservatism that as early as 1890 it was impressing outsiders as quaint. It has been estimated that 1,200 tourists a year visited Main Amana alone in the early 1900s (Shambaugh 1932:91). The automobile made its appearance, not only bringing more tourists but giving Amanans a novel lesson in personal mobility. Then came the radio, baseball, and bobbed hair. The Elders found it increasingly difficult to resist the flood of modernity.

At the same time that outside influences were being felt in the Colonies, some members of the Community began to venture into “the world” with more frequency. They were mostly the young, the third generation after the leaders of the Reawakening. They were curious about the outside, curious to learn what money could buy beyond their narrow and well-protected sphere. Some were content with surreptitious daytrips to Cedar Rapids. Others wanted an education, more freedom, or remunerative work, and either knew or sensed that their options in the Community were limited. Many young people left Amana, and it was difficult for the Elders to stop them. They returned for visits with their own automobiles and with presents for their Colony relatives, adding to the world’s penetration of the Community’s boundaries. Their departure also created a shortage of labor and of young talent in particular.

Then came World War I. The war brought increased prosperity to the Colonies. High agricultural prices and a government contract for woolens more than made up for the closing of the calico mill due to the unavailability of dyestuffs. The Amana Society had its three most profitable years ever in 1918, 1919, and 1920. In small but noticeable ways, ordinary members benefitted from this wealth. In return, the war effort demanded many of the Community’s young men. During the Civil War, the Society had been able to purchase “substitutes” for its draftees, but the laws had changed. Furthermore, this was a war against Germans, and the Colonists’ patriotism was in question. Twenty-seven Amana men went into the army. Most entered as conscientious objectors and served in the quartermaster corps. Two died of influenza at Camp Pike; the rest saw something of the world and returned home with a growing conviction that Colony life had become outmoded.

Already undermined by the increasing contact between the Community and the outside, the Inspirationist system was dealt some jarring economic blows in the 1920s. The wartime economic boom gave way to a post-war downturn as recession hit the farm economy and the bottom dropped out of the woolens market. Although dyestuffs again became available, the calico print works never reopened, the victim of changing clothing fashions. The Society went from a $7,000 net profit in 1922 to a $73,000 deficit in 1923, and recorded losses in every one of the next nine years. In 1923, a disastrous fire swept through the woolen mill [Image at right]. The lack of insurance (“God’s will be done”) put an enormous strain on the Society’s resources to rebuild it. The labor shortage and rising costs associated with hired labor contributed further to the Society’s insolvency. To make matters worse, selfishness and resentment began to show itself in some members, and malingering and dishonesty became more common.

economy and the bottom dropped out of the woolens market. Although dyestuffs again became available, the calico print works never reopened, the victim of changing clothing fashions. The Society went from a $7,000 net profit in 1922 to a $73,000 deficit in 1923, and recorded losses in every one of the next nine years. In 1923, a disastrous fire swept through the woolen mill [Image at right]. The lack of insurance (“God’s will be done”) put an enormous strain on the Society’s resources to rebuild it. The labor shortage and rising costs associated with hired labor contributed further to the Society’s insolvency. To make matters worse, selfishness and resentment began to show itself in some members, and malingering and dishonesty became more common.

A sentiment for change began to grow in the Community. Although opposed by some of the remaining, and now elderly, second-generation Elders, the idea took hold that the communal system was no longer workable and would have to be abandoned if the Amana Society was to avoid bankruptcy. In 1931, a committee was elected to study the possible alternatives. It recommended reorienting the Society’s businesses along profit-seeking lines and creating a joint-stock corporation, with members of the old Amana Society becoming stockholders and wage-earning employees of the new

Amana Society. The new corporation would continue to pay the medical and dental expenses of members, but the community kitchens and other aspects of the communal economy would be discontinued. After months of meetings and deliberations, the members voted [Image at right] in favor of the committee’s proposal, and on June 1, 1932, Amana’s “Great Change” took effect, and the mana Society (I) became the Amana Society (II).

There are at least three ways to view Amana’s Reorganization of 1932. One can see the original Community of True Inspiration as a purely religious association to which, in 1843, a socio-economic system was joined and from which that socio-economic system was disconnected in 1932, returning the Community to its original sectarian character. Alternatively, one can see the changes of 1843 (moving to America and adopting communalism) as necessary to sustain the religious association in the face of persecution and life in a strange new land, and the Reorganization of 1932 as signaling the demise of that association, the end of a community defined primarily by religion. Or one can see the changes of both 1843 and 1932 as helping to sustain a community of people who wanted to remain together, even if it meant significant changes in both their church and their economy.

In fact, there is no need to choose among these three alternatives. Each is true or, rather, each has elements of truth in it. Amana’s theocratic system did fail in 1932, but the Inspirationists’ religious faith survives within the Amana Church Society. The communal system also failed in 1932, but Amana’s economy continues in a different organizational form, and is still based on agriculture and manufacturing (with tourism as a significant addition in more recent years).

Since 1932, most of the energy and creativity in the Amana Colonies has gone into business. In the wake of the Reorganization, the Amana Society (II) redesigned its accounting system, closed several old and unprofitable businesses (which had been maintained for the convenience of members), merged the two woolen mills, and released most of the hired hands. The profit motive provided the Society inducement to concentrate on lucrative enterprises and to develop new ones with growth-potential. The farms remained profitable by following the main trends of Iowa agriculture, producing mostly corn, soybeans, beef cattle, and (until recently) hogs. Two of the Amana Society (I)’s meat shops continued to operate, selling initially to members but increasingly to tourists. The woolen mill’s retail outlet was expanded to take advantage of the growing tourist trade, and the cabinet shops, which once supplied furniture for members of the Amana Society (I), were amalgamated into a single retail furniture-making business. The most important innovation was the development of a modern factory for the manufacture of freezers and refrigerators. So successful was this enterprise (one reason was a government contract during World War II) that the Amana Society (II) feared it would come to dominate other corporation businesses and sold it to outside private investors. Amana Refrigeration, Inc., which over time has had a series of corporate owners, most recently Whirlpool, continues to operate today in Middle Amana and employ a large workforce.

Following Reorganization, numerous private businesses appeared in Amana, virtually all of them catering to tourists. The first were restaurants and wineries, trading on the old Colonies’ reputation for good and ample food and wine. Tourism increased substantially beginning in the mid-1960s due to the completion of nearby Interstate Highway 80 and the designation of the Amana Colonies as a National Historic Landmark, spawning a wide variety of shops selling arts and crafts, antiques, clothing, and specialty foods, as well as numerous B&Bs and hotels. Although tourism, like other sectors, has ebbed and flowed, today over seventy businesses operate in the Amana Colonies, only a handful owned by the Amana Society (II).

The prosperity of both the Amana Society (II) and the Colony’s private sector has meant a rapid and rather dramatic increase in the standard of living of virtually all of the residents. There is no poverty or unemployment to speak of in Amana. The Amana Colonies supports a fine K-12 school with excellent facilities (consolidated twenty years ago with the school in a nearby town) as well as a first-class retirement community and nursing home. In terms of amenities and material comforts, Amana is as modern as any small town in America. An unfortunate similarity in name, however, still draws some tourists expecting to find Amish horse-and-buggies.

Inevitably, Amana’s modernization has come at a price. Many communal-era buildings have been torn down or extensively remodeled, and much of the new residential construction looks typically mid-American. Many of Amana’s young people have gone to college, married outsiders, and moved away. Others have settled in the Colonies with new ideas and outside spouses, diluting the hold of tradition. The emergence of an economic sector geared toward tourism entailed other changes, most notably a dramatic shift away from social and cultural introversion to the idea that “Amana Welcomes the World,” as one tourist sign proclaimed a few years ago. And the world has come. Tourists overrun the villages, especially during the summer (several years ago, the Amana Tourism Council boasted as many as one million visitors a year), dispelling any vestige of the bucolic air which once characterized the Colonies. Local production could not keep pace with these numbers, and much of what is for sale in Amana today is produced outside the Colonies.

As early as the 1960s, these trends were being noticed by more and more Amanans, who began to voice concerns about the erosion of the Community’s heritage. Fortunately, Amana’s prosperity allowed them to put their words into action. By the mid-1970s, a concerted effort was underway to preserve what remained of Amana’s past and to reclaim some of the traditions which had begun to disappear. The Amana Heritage Museum, opened in 1968, is a repository for (especially) communal-era material culture and an archive for records, photographs, and taped oral reminiscences of the Community’s past. The Amana Preservation Foundation was formed in 1979, dedicated to the preservation and restoration of communal-era buildings. The Amana Artists’ Guild sponsors programs of instruction in crafts of the past, including basket-making and tinsmithing, as well as in contemporary arts. Many Amana residents and outsiders have taken advantage of these programs, and a revival of handcrafting is occurring. In 1982, Colony residents approved the creation of an Amana Colonies Land Use District. Its board of directors has the power to make and enforce policies governing patterns of land use and styles of architecture with the aim of preserving the villages’ historic character.

Most of these trends begun in the 1960s have continued till the present, but Amana has also witnessed the further inevitable erosion of living memory of the communal era as those who had reached adulthood before the 1932 Reorganization have now passed from the scene. In fact, the Amana Society (II) has now been in existence longer than the communal Amana Society (I).

In its 300-year history, the Community today called Amana has undergone several major transformations. It has been a religious movement, a sect, a cooperative association, a communal society, and a joint-stock corporation. Twice it has been on the verge of collapse, and both times it has been revitalized. It has faced persecution and escaped it; it has, more recently, faced the prospect of complete acculturation and resisted it. It was America’s fourth-longest surviving communal society when it reorganized in 1932, and descendants still cherish the memory of those times. Amana’s religion has survived, but strictly speaking the Community of True Inspiration has not. The growth of Amana’s economy, and especially of tourism, has granted the Community a prosperity that simultaneously threatens the past and sponsors efforts to preserve it.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

An especially important inspired message to the Community of True Inspiration, spoken by Johann Adam Gruber in 1716, came to be called the “Twenty-four Rules for True Godliness.” It contained guidelines concerning the members’ interactions with one another, with the “world’s people,” and with prospective members. It also addressed the role of families in the community and of the lay Elders appointed in inspiration to lead each Versammlung (congregation). It warned against the ritualization of worship, stressing that faith could only live in heartfelt communion with God and the other members of the community and not through the performance of ritual. Finally, it announced itself as the basis of the covenant among the members and between the Community and God, calling for the members to pledge the set rules with a verbal affirmation and a handshake. For 300 years the Community has honored this statement of faith, and church members still renew the covenant through a pledge.

Eberhard Ludwig Gruber, Johann Adam’s father, never became inspired, but with his theological training and long involvement with Separatism he became the Inspirationists’ spokesman. He wrote several tracts about the phenomenon of inspiration, reports about the group’s early years, and pamphlets describing other items of the group’s faith. In 1715, he wrote down “Twenty-one Rules for the Examination of Our Daily Lives,” a practical guide for Inspirationists about how to comport themselves in the world. He also served as “Overseer of the Werkzeuge, ” endowed with a special ability to distinguish true inspiration (from God) from false inspiration (from Satan). The Inspirationists made a point of emphasizing this difference, since they came into contact with several putative Werkzeuge whom they believed to be falsely-inspired. An important test of “true” inspiration is that it contradicts nothing in the Bible.

Although considering themselves devout Christians with a faith rooted firmly in Scripture, the Inspirationists embraced several articles of doctrine which distinguished them from the majority of German Protestants at the time of their founding. Paramount among these, of course, was the belief in inspiration. Other distinctions involved their rejection of common beliefs and practices. For instance, they did not practice infant baptism or baptism by water at any time of life, citing especially 1 Cor. 1:17; Rom. 2:28-29; John 3:5 and Titus 3:5 as justification. They refused to swear oaths, considering it a form of blasphemy. They refused military service on religious grounds. They refused to support the state Church or to send their children to state-run schools. They had no ordained clergy, but rather lay Elders. On this point it is noteworthy that although only men could serve as Elders, Werkzeuge, who were “chosen by God,” were often women, another distinguishing feature at that time.

In addition, they believed the millennium was imminent and paid special attention to the biblical book of Revelation. In anticipation of that event, they apparently accepted the principle of gender separation, though evidence for its practice is most clear only after they moved to America and set up full-featured communities, where men and women were separated in church, at work, and at communal meals. They encouraged (but did not require) celibacy, taking their lead in this from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians, although it is possible to trace an influence back to the German mystic Jakob Boehme’s notion of an original androgynous Adam and the idea that sexuality is a manifestation of separation from God. The cohort of members born in Ebenezer, New York, in the 1840s and 1850s, a period of intense religious enthusiasm in the Community, had a lifetime celibacy rate of forty percent, one of the highest rates of voluntary celibacy ever documented (Andelson 1985).

Other religious beliefs were manifested in the physical character of Amana churches and cemeteries. (Unfortunately, little is known of their worship or burial spaces in Europe.) Both the exteriors and interiors of church buildings were simple, without iconography or symbolism of any kind. For worship services the members sat on plain pine benches, men in one half of the church and women in the other, the youngest members seated closest to the front of the room (where the elders sat facing the congregation), the oldest at the rear of the room. This de-emphasis of the family unit carried over to the cemeteries, where members were buried in the order of death rather than in family plots, beneath uniform headstones bearing only their name and dates of birth and death (or date of death and age) (Andelson forthcoming). These sacred spaces clearly proclaimed the virtues of simplicity and equality before God. Supporting this, central messages of the Werkzeuges’ testimonies dealt with the importance of humility, self-denial, and piety.

The strength or prominence of these various beliefs and articles of faith has varied through time. As noted earlier, gender separation probably was more emphasized once the Inspirationists established a communal order in America. It ended after the 1932 Reorganization in the communal kitchens (which were disbanded) and in workplaces, although it persisted in the church until recently. In another departure from tradition, the church has accepted female Elders since the 1990s. Millennialism was much more pronounced among the Inspirationists in the eighteenth century than in the nineteenth, and it virtually disappeared from the Community’s religious discourse in the twentieth. Several other beliefs have also weakened through time. Celibacy became uncommon after the move to Iowa. The refusal to swear oaths gave way after 1932 and Amana’s growing involvement with external authority. Pacifism, still important during World War I, receded by the time of World War II, when many Amanans served in combat. The rejection of state-sponsored education lessened after the Inspirationists came to America, although the community operated its own schools, albeit with state-certified teachers, until the merger with a neighboring district in the 1990s.

On the other hand, several items of traditional doctrine and practice remain. The Amana Church still does not practice infant baptism or water baptism at any age. The Church has no ordained clergy. Church buildings and cemeteries remain as they have been since 1855, proclaiming the virtues of simplicity and equality before God. It is difficult to say how the Amana Church members today feel about inspiration. The testimonies are still revered as the Word of God and are read in church services, though probably few members feel that inspiration could come again to the Community, even though the reason most often given (“we have become too worldly”) could also have been claimed prior to the Reawakening of 1817. Amana history records the case of a young man in the nineteenth century who sometimes manifested the motions associated with inspiration, and the Elders hoped he might become inspired, but it never happened. In the 1980s a man from Denmark visited Amana claiming to be the leader of a congregation of Danish Inspirationists that traced its ancestry back to Gruber and Rock. Those Amanans who heard about his visit (surprisingly, many did not) mostly displayed polite curiosity but not more, and nothing ever came of the contact. Inspiration has not been a living presence in Amana since Barbara Landmann’s death in 1883, but its place in the identity of members of the Amana Church seems secure.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Rather little is known about the religious rituals and practices of the Inspirationists in the eighteenth and first part of the nineteenth centuries. While we have a good record of the inspired testimonies (which for that period number over a thousand, including the occasion on which each was delivered and to whom, and a full transcript of the content), these do not describe the nature of ordinary prayer meetings or the rituals which the Inspirationists routinely performed. Therefore, the information that follows is drawn mostly from the Community’s time in Amana, first from the communal period and then from the post-communal period.

In communal Amana (1855-1932), the Church held eleven regular worship services each week: Sunday morning and afternoon, Wednesday morning, Saturday morning, and short prayer services every evening. Special services were held on major Christian holidays: Good Friday, the days of Holy Week, Easter, Ascension Day, Pentecost, and Christmas. Easter, Pentecost, and Christmas were celebrated as two-day holidays. New Year’s Day was religiously observed. Funerals occasioned a church service for family and close friends of the deceased. Each meal taken in the communal kitchens was a religious act, eaten in silence and beginning and ending with a prayer. All together, these add up to over 1,000 routine ritual occasions a year in the lives of the Inspirationists during the communal period.

In addition, the Inspirationists practiced four special religious services. The most sacred of these were Liebesmahl (Love Feast, or Holy Communion) and Bundesschliessung (Renewal of the Covenant), closed to non-members and suffused with important sacred symbols. We know from Church records that the Inspirationists held Holy Communion services in the first three years of the Community’s history, but then, inexplicably, not again for 120 years until 1837, then regularly after that for ninety years, followed by another interruption, and then a resumption. The Renewal of the Covenant, initiated by Johann Adam Gruber in 1716, likewise was not regularized until the nineteenth century. The Unterredung (Yearly Spiritual Examination), like the other two, began in the eighteenth century, but may also have been regularized only in Ebenezer; it was a less sacred but nevertheless important ritual in which the Elders in each village examined the obedience and spiritual standing of individual members. The Yearly Spiritual Examination not only expressed the theocratic nature of the Community but helped to regulate behavior. Finally, the Kinderlehre (Youth Instruction) was a special annual service designed to enhance the piety and spirituality of young members.

For many of these worship services, the members in each village came together as a single group. For others, however, they were divided into grades or ranks according to the principles of age and spiritual condition. The senior and more spiritually advanced members were in the Erste Versammlung (First Congregation), the more mature young people “with a good Christian upbringing” were in the Kinderversammlung (Youth Congregation), while the children belonged to the Kinderlehre (Catechism School) (Scheuner 1977 [1884]:53). In later years, a Zweite Versammlung (Second Congregation) was added between the Erste Versammlung and Kinderversammlung , but it is not clear when this change was made. Normally, a member would advance with age and spiritual maturity from the Youth to the Second to the First Congregation, reaching the last around the age of forty. An Elder would instruct them when to move. However, if a married couple became pregnant, both husband and wife were demoted to the Youth Congregation for a year as a mark of giving in to “temptations of the flesh.” At the end of the year, they would begin moving up in the ranks again.

A few other details about the Inspirationists’ worship services can be noted. The village Elders sat on benches at the front of the chamber facing the congregation, the presiding Elder at a small table in the center. Men and women entered the church through separate doors and sat in separate halves of the room. Women wore a black cap, black scarf, and black apron over their dark-colored dresses, a tradition dating back to the eighteenth century; men wore dark suits. Members carried two volumes with them to services, the Bible (with Apocrypha) and the Inspirationists’ own hymnal. All singing was a capella, led by male and female song leaders. Musical instruments were not part of church services. Regular services included at least an opening hymn, a prayer, a reading from Scripture, a reading from one of the inspired testimonies, a sermon by the presiding Elder, recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, a closing prayer, and a closing hymn.

Although the Inspirationists’ core religious beliefs remained unaltered in their essence after the 1932 Reorganization, some of the rituals and practices changed at that time. The Amana Church Society discontinued the Yearly Spiritual Examination and the system of ranks, perhaps the clearest sign that the theocratic system of the Amana Society (I) had ended. The Youth Instruction service also eventually ceased. The number of regular church services each week gradually declined from eleven to only one, for an hour or so on Sunday morning. In the 1960s, the Church began to offer English language services in response to increasing numbers of young people not learning German and some non-German speakers marrying into Amana and wanting to attend the Church. Gradually English began to find its way into the German language services as well, and today all services are in English. Despite this, the number of church members has gradually declined, the result of some members moving away, others leaving the church following marriage to an outsider and attending church elsewhere, and a growing proportion of Amana’s population moving in from the outside with no connection to the church. As the number of church members has declined, so has the number of villages in which services are held, until today services are held only in the church in Middle Amana, the most centrally located of the seven. The decline in number of services and number of members has also led to a decline in the number of Elders. At Amana’s population peak during the communal era, as many as eighty or ninety Elders were active at the same time. In 2015, the number of Elders was fewer than ten, although the Church hopes to recruit more.

Despite these changes and the numerical decline, the Amana Church Society remains a vibrant, relevant, and spiritually rich institution, and an important part of the Amana Colonies.

LEADERSHIP/ORGANIZATION

Much has already been said about the nature of leadership in Amana Society (I). It remains to add the details of the governance system. The affairs of the Society as a whole were in the hands of the Trustees, or Great Council of Elders (Grosser Bruderrath), whose members (one from each village and six at-large) were elected by popular vote every two years. In advance of the vote, the Trustees put forward a slate of candidates, and every voting member of the Society (men over twenty-one and unmarried women over thirty-five) could vote “yes” or “no” for each. The slate generally consisted of the incumbent Trustees, except when death, infirmity, gross incompetence, or a moral failing necessitated a new candidate. No opposition candidates were presented, so incumbents were almost always returned to office. Serving on the Great Council normally required at least a degree of business acumen, since the Trustees made all major economic decisions as well as decisions about the general welfare of the Society. It was not uncommon for a younger Elder with demonstrated business ability to be selected over older, and possibly more pious, Elders who lacked it. The Great Council elected from its own membership a president, vice-president, secretary, and treasurer, all of whom played a special role in representing the Amana Society in dealings with the outside. The Trustees appointed managers of the Society’s major businesses: the farms, the mills, and the general stores.

The Trustees also named Elders in each of the villages to a local, or village, Council (Bruderrath). Here it was common for piety to be weighed more heavily in the selection, since the village Councils oversaw the spiritual condition of members in their village, in addition to making decisions about housing assignments, kitchen assignments, and job assignments. While Elders served on the local Council at the pleasure of the Trustees, normally they, too, remained in their positions indefinitely. The size of the local Council varied according to the population of the village. Being on the local Council was not perceived as a step on the path toward becoming a Trustee, though the longest-serving Elder in each village was usually designated the “head Elder.”

While a Werkeug lived, Elders were named through inspiration; after Landmann’s death the Great Council assumed the task of appointing them. The main responsibilities of Elders who were not on either the local or Great Council was to lead worship services, perform funeral services, officiate at weddings, and in general keep an eye out for rule-breakers and breeches of morality, which would normally be reported to the local Council. Piety and a good speaking voice were viewed as important qualities in an Elder.

Following the 1932 Reorganization, the local Councils were discontinued since most of their responsibilities ended under the new more individualistic and corporate system. The Great Council morphed into the Board of Directors of the Amana Society (II), which has continued to function in ways that are generally similar to the old Great Council, though with a narrower focus on the Society’s business operations and property (most of the original 26,000 acres). In the communal era, everyone living in the Amana villages except for the hired hands was considered a member of the Amana Society (I). Since the Reorganization, Amana Society (II) is beholden only to its shareholders, not all of whom live in the Colonies. For the Amana Church Society a new Board of Trustees was created which oversees church business and church property (the church buildings and the cemeteries). Membership in the Amana Church Society overlaps with but does not coincide with membership in the Amana Society (II). Furthermore, a considerable number of the residents of Amana today, perhaps half, are neither church members nor shareholders in the Amana Society (II). Thus, Amana’s governance system since Reorganization is more diffuse, and the possible identities of people in Amana (resident, member of the Society, and member of the Church) are separate and distinct.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Amana Colonies cannot fail to impress today’s visitor. The land is fertile, well-managed, and productive, the economy diverse and prosperous (and unemployment very low), the people energetic, creative, and content. These are enviable achievements for a small, rural community now in its 161 st year. The Amana Society (II) is in its eighty-fourth year of solvent operation; add to this its Amana and Ebenezer corporate antecedents and we have a set of integrated businesses that date back 173 years. The Amana Church Society in 2014 celebrated its 300 th anniversary. Insofar as longevity is a measure of success, Amana has been successful. Through time it has demonstrated flexibility, resiliency, and a knack for innovation.

This judgment on Amana’s past seems secure. What is the prognosis for its future? Perhaps the question needs to be addressed separately for each of Amana’s three identities mentioned above. The Amana Colonies, the seven villages with their modern mix of residents, depend for their continued prosperity on tourism. Tourism depends on many factors, internal and external. Over the external ones Amana has no control. Heretofore, the internal factors have depended on Amanans’ ability to market the past as a combination of ethnic (German) heritage, a distinctive built environment, and a tradition of handcrafted quality. (Amana’s communal era is highlighted in the museums, but it has not been a crucial part of the tourist draw in a strict sense.) The first of these seems likely to continue to fade as Amana’s German character gets diluted by time. The distinctive built environment has unquestionably been reduced as older structures decay and are torn down and new ones are erected in their places. However, many old buildings remain and are being cared for by the Society and private owners; the distinctive village layout also will persist. The tradition of handcrafted quality is fairly robust in Amana and is benefitting from a partial turn toward it in the country generally.

The future of the Amana Society (II) likewise depends on many factors beyond local control. However, the leadership seems capable, is committed to historic preservation, and has just gone through a period of re-branding for twenty-first century marketing that looks promising. An important question concerns the number of stockholders, which has been slowly but steadily declining for fifty years. Some innovations have partly addressed this problem in the past, but new solutions will soon be needed.

And what of the Church, the foundation of everything in Amana? Here, too, declining numbers will need to be addressed. Whether addressing this will compromise yet more of the legacy of the Community of True Inspiration, as has happened in numerous ways since the Reorganization, remains to be seen. Given Amana’s remarkable record of adaptation, the current members are hopeful.

REFERENCES

Andelson, Jonathan G. 1985. “The Gift to be Single”: Celibacy and Religious Enthusiasm in the Community of True Inspiration. Communal Societies 5:1-32.

Andelson, Jonathan G. forthcoming. “Amana Cemeteries as Embodiments of Religious and Social Beliefs.” Plains Anthropologist.

Scheuner, Gottlieb. 1977 [ originally published in German 1884]. Inspirations-Historie, Volume I: 1714-1728, translated by Janet W. Zuber. Amana, Iowa: Amana Church Society.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES

Andelson, Jonathan G. 1997. “The Community of True Inspiration from Germany to the Amana Colonies. Pp. 181-203 in America’s Communal Utopia , edited by Donald E. Pitzer. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Foerstner, Abigail 2000 Picturing Utopia: Bertha Shambaugh and the Amana Photographers. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Shambaugh, Bertha M.H. 1932. Amana That Was and Amana That Is. Iowa City: State Historical Society of Iowa.

Webber, Philip E. 1993 Kolonie-Deutsch: Life and Language in Amana. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

IMAGES

Image #1: Sketch of the woolen mill at Ebenezer.

Image #2: Sketch of Amana Village in Iowa.

Image #3: Map of Amaa villages.

Image #4: Christian Metz cemetery headstone.

Image #5: Remains of the Amana woolen mill after the 1923 fire.

Image #6: The ballot proposing the “great change” of Amana organization. The ballot is written in German.

Author:

Jonathan Andelson

Post Date:

27 April 2016