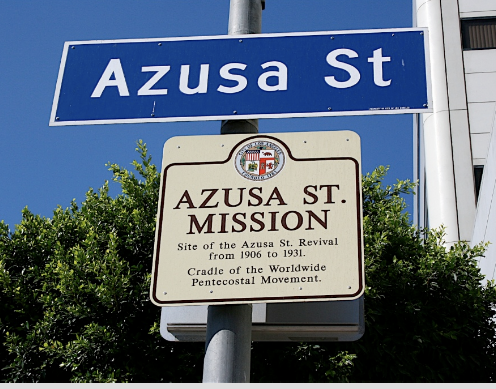

Azusa Street Mission

AZUSA STREET TIMELINE

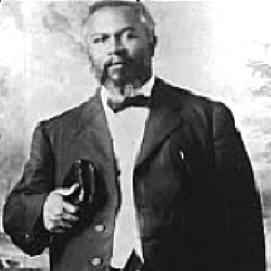

1870 (May 2) William Joseph Seymour was born in Centerville, LA.

1905 Seymour became a student of Charles Parham in Parham’s new Bible school in Houston, TX.

1906 (April) Seymour accepted, with Parham’s blessing, an invitation to speak in a small Holiness Church in Los Angeles, CA.

1906 (September) Seymour, with the help of two members of the congregation, began the newspaper Apostolic Faith.

1908 (May 3) Seymour married Jennie Evans Moore, an early convert.

1908 Many white members of the congregation left the mission, some to found similar revivals and congregations in other cities.

1909-1913 The revival gradually declined. Seymour remained as pastor of the Apostolic Faith Mission.

1922 (September 28) Seymour died of a heart attack.

1922-1931 Jennie Moore Seymour continued the mission as pastor until the building in which the revival took place was lost in foreclosure.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Azusa Street revival was a landmark moment in the history of the Pentecostal movement, and today virtually all Pentecostal  groups trace their origins to Azusa Street. It was not, however, the only, or even the first, Pentecostal source. While much of what happened at Azusa Street was indeed distinctive it, was not entirely unprecedented. It was, in a way, the logical outcome of several generations of historical and theological development (Blumhofer 1993:3-6).

groups trace their origins to Azusa Street. It was not, however, the only, or even the first, Pentecostal source. While much of what happened at Azusa Street was indeed distinctive it, was not entirely unprecedented. It was, in a way, the logical outcome of several generations of historical and theological development (Blumhofer 1993:3-6).

The revival was seen by the faithful in an already well-understood religious context. The end of the world was coming soon and God, through an “outpouring of the Holy Spirit,” was empowering those who would accept for one last burst of evangelism and preparation before it was too late. Also, those who were “baptized in the spirit” could hope to join the saints who would be taken in “the rapture.” This understanding had grown, over several generations, from the Wesleyan concept of “complete sanctification” (Blumhofer 1993:11-42).

The history of popular religion in the United States, and to a lesser extent in Canada and the United Kingdom, had been one of successive waves of revivalist renewal. Scholars recognize three distinct periods of revival-based “Great Awakening” before the turn of the twentieth century. Each had involved progressively more “spirit oriented” or supernatural emphasis. The Methodists spawned the Holiness movement built on concepts of piety and sanctification through a “second (or third) act of grace” or “baptism of the spirit,” which followed conversion (and in some formulations, after sanctification) and made believers able to resist temptations to sin (Knoll 1992:373-86).

This general idea, in various forms, led over time to a highly developed theology of the actions of the Holy Spirit in the lives of individuals, and to a number of new denominations. This movement, beginning in the late nineteenth century, was sometimes called “The Latter Rain,” a reference to Joel 2:23-29, which describes an early rain that starts the plants and a latter rain that prepares the plants for harvest. Especially in Holiness churches, there was both a well-developed hope for yet another “outpouring,” and predictions that it would be worldwide and would lead to extensive missionary activity before the beginning of the End Times. Many, perhaps most, believers who observed reports of widespread revival activity became convinced that that “outpouring,” or Latter Rain, was already underway (Blumhofer 1993:43-62).

In the United States, there was the Zion City movement near Chicago, where a whole new town had been constructed along theocratic lines by followers of an Australian born evangelist, John Alexander Dowie. In New England there was the Shiloh community of Frank Weston Sandford, a student of Christian and Missionary Alliance founder A. B. Simpson. There were also several other highly successful and widely publicized revivals around the country, and especially in the Southeast. But by far the most influential event in this context was the Welsh revival of 1904-1905. This event was widely noticed, even in the U.S., and involved very large numbers. Many of these venues incorporated “spirit blessings,” such as healing and prophecy, and in a number of cases, glossolalia (Blumhofer 1993:43-62; Goff 1988:17-106).

About 1900, Charles Fox Parham, an independent Holiness evangelist based at the time in Topeka, Kansas, studied the work of

several spirit-oriented revival organizations that had led to glossolalia. Parham connected this phenomenon with the description in Acts 2:4 of the day of Pentecost, and concluded that “speaking in tongues” was actually the initial proof of the “spirit baptism.” He also thought that other phenomena, such as interpretation, healing and prophesy, were all gifts of an ecstatic “outpouring” of the spirit. He coined the term “apostolic faith” for his understandings (Blumhofer 1993:43-62).

several spirit-oriented revival organizations that had led to glossolalia. Parham connected this phenomenon with the description in Acts 2:4 of the day of Pentecost, and concluded that “speaking in tongues” was actually the initial proof of the “spirit baptism.” He also thought that other phenomena, such as interpretation, healing and prophesy, were all gifts of an ecstatic “outpouring” of the spirit. He coined the term “apostolic faith” for his understandings (Blumhofer 1993:43-62).

Parham, a Kansas frontier farm boy, was once a Methodist lay preacher who was seriously uncomfortable with authority, church or otherwise. He caught the Holiness spirit and began his own mission, including a healing home and later a Bible school where some students spoke in tongues after fasting and lengthy prayer sessions. After several successful revivals, he moved the school to Texas, following the spread of his reputation. There he met and encouraged a student named William Seymour, who could only participate in classes by sitting in the hallway outside the classroom or behind a curtain because of his race. (Goff 1988:17-106)

William J. Seymour was an unlikely founder of a world faith. He was born in Centerville, Louisiana, the first son of former slaves. His early years were spent in the abject poverty of Reconstruction-era freed black farm workers on a sugar plantation. Hoping for better times, he left in early adulthood and followed a somewhat nomadic existence, working mainly as a waiter in city hotels in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, possibly Missouri, and Tennessee. In Cincinnati, he had a near-fatal case of smallpox, losing one eye and ever after wearing a beard to hide the scars. In Indianapolis, Seymour had joined the Methodist Church, but he soon moved to the Church of God Reformation Movement based in Anderson, Indiana. This conservative Holiness group was then called the Evening Light Saints. With this group he was sanctified and called to preach. He later moved to  Houston, Texas, looking for relatives; it was there that he met Parham through a friend and part-time pastor of a small, black Holiness congregation, Lucy Farrow. (Pete 2002-2012; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; “Bishop William J. Seymour” n.d.)

Houston, Texas, looking for relatives; it was there that he met Parham through a friend and part-time pastor of a small, black Holiness congregation, Lucy Farrow. (Pete 2002-2012; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; “Bishop William J. Seymour” n.d.)

Seymour knew Farrow because he was a member of her church. But she was also employed by the Parham family and traveled with them, and on occasion had “spoken in tongues.” While Farrow was on one such trip, Seymour filled in for her. At one of the meetings where Seymour preached was a visitor from California, Neely Terry, on a trip to see relatives nearby. At home in Los Angeles, Terry was part of a small mission on Santa Fe Street led by Julia Hutchins. This congregation consisted largely of followers of Hutchins who had all been expelled from the Second Baptist Church because of Hutchins’ Holiness teachings. She felt the need to have a male assistant in order to continue her work effectively. Neely recommended Seymour, and Hutchins invited him. (“The Road to Azusa” n.d.; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.)

It was Parham’s message of apostolic faith that Seymour preached when he arrived in Los Angeles. But Seymour’s spark of apostolic faith landed in the tinder of hope for a visit (or “outpouring”) of the Holy Spirit, which had become part of the Holiness culture and expanded with the holiness movement. The result was the ecstatic reenactment of the day of Pentecost in a backwater industrial neighborhood of Los Angeles. The flame of Pentecostalism that he ignited has become the second largest group of Christians in the world, after Roman Catholics. At the time, however, the message was rejected by Hutchins and the Southern California Holiness Association. Nonetheless, Seymour began holding prayer meetings with Terry, her cousins and several members who did not reject his approach, including Edward Lee in whose home nearby Seymour was lodging. Lucy Farrow, sent by Parham, was soon there to help (Cauchi 2004; Blumhofer 2006:20-22; “Bishop William J Seymour” 2004-2011).

The Azusa Street Revival actually began, in fact, in the home of Terry’s cousins, Richard and Ruth Asberry on Bonnie Brae Street. A number of those attending a “prayer meeting” led by Seymour were moved by a religious experience to “speak in tongues,” that is, to verbalize in something other than their native (or previously learned) language in April of 1906. Word of this phenomenon spread very rapidly and crowds of those drawn by these reports soon outgrew the available space. A search of the area turned up an abandoned church building at 312 Azusa Street where makeshift facilities were developed from available materials, such as boards placed across backless chairs. ( Cavaness, Barbara n.d.; “Bishop William J Seymour” 2004-2011). almost every day. Several aspects of these meetings were unusual at that time. First, worshipers included both blacks and whites at the peak of the “Jim Crow” segregationist era. Second, the leadership of women was recognized and encouraged well before suffrage, and developed beyond the traditional supporting roles. The initial beliefs that the Holy Spirit eliminated race, class and gender differences, that racial lines were “washed away by the blood,” in the words of one of Seymour’s white assistants, and that women were qualified for leadership roles were soon strongly criticized, however, and did not survive past 1909. Third, the meetings were largely unstructured and spontaneous, with testimony, preaching, and music proceeding without any established order, often without evident leadership. Fourth, the meetings involved and encouraged a very highly charged emotional atmosphere. And finally, in a most distinctive aspect, many attendees exhibited unorthodox behavior such as falling down and seemingly passing out (called by the faithful “being slain in the spirit”), “speaking in tongues,” interpreting tongues, prophesying, and miraculous healing. All these behaviors were strongly encouraged and drew the attention of the secular media as well as visitors from across the country and around the world. Worshipers included those of almost every race and class, a highly unusual mixing at the time. A Los Angeles newspaper described it as a “weird Babel of tongues,” and even Charles Parham, when he visited, was outspoken in his consternation with what he saw. (Goff 1988:17-106; Blumhofer 1993:56-62; “Bishop William J Seymour” 2004-2011; Cauchi 2004; Blumhofer 2006:20-22; Knoll 2002:151-52).

Those who had the unorthodox experiences listed above were not simply moved by a powerful sermon. Many had been praying intensely for hours or days for such a moment. Indeed, some of those hoping for an “outpouring of the Spirit” were part of the culture of their Holiness denominations and had been praying for this outpouring for much longer. The signs and wonders, the tongues, prophecy and miracles were seen as evidence that they had “broken through.” Attention of other evangelicals was drawn through the revival’s newspaper Apostolic Faith, founded in late 1906. The publication reached a circulation that may have been as high as 50,000. It was distributed nationwide, and a few copies went abroad. (“History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d; Dove 2009).

The most intense portion of the revival lasted for about three years, until most of the white, and female, leaders departed in 1909, many to start their own ministries or to join in others. One white woman who had edited the newspaper, and may have wanted to marry Seymour, left when Seymour married Jennie Evans Moore. She took the mailing list with her. The Azusa Street Apostolic Faith Holiness Mission, as the church itself was called, lasted as a small, mostly black Holiness congregation past Seymour’s death in 1922 until the building was lost in foreclosure in 1931 (“History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; “The Apostolic Faith” 2004-2012; Cauchi 2004).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Azusa Street Revival lasted only a few years and involved no formal or written theology. It grew out of a general Holiness background and much of its doctrinal structure may be deduced by looking at common Holiness beliefs of the time, with one major addition, glossolalia (“speaking in tongues”) as evidence of “Spirit Baptism” (Knoll 1992:386-7).

Specific beliefs, beyond those held by Christians generally, would include:

* That the Holy Spirit continued to be active in the world and to bring a “baptism of the spirit” in individual lives, providing the power for service, evangelism and resistance of temptation (Knoll 1992:386-7).

* That glossolalia was the biblical, initial evidence of this baptism (Knoll 1992:386-7).

* Acceptance of a dispensationalist-premillennialist world view, belief that they lived in the last period, or dispensation, of history and that Jesus millennial return was imminent. This doctrine included the belief that the contemporary period of revival was a last chance to evangelize the world before it was too late. Further, that those who had been baptized in the spirit would be among the living saints snatched up to heaven (sometimes called “the rapture”) before the seven years of tribulation began. This belief system placed substantial emphasis on concern with end times (eschatology), and usually considered the Book of Revelations as prophesying events of the soon to come end times (Blumhofer 1993: 55-62).

* Acceptance of an early form of Biblical literalism that presaged the Fundamentalist Movement (Blumhofer 1993: 55-62).

* Salvation (initial conversion) as being by faith (Cauchi 2004).

* That God, through the Holy Spirit, continued to provide for healing of sickness. (Knoll 1992:386-7)

* Mainline churches (“denominationalists”) had institutionalized religion to the point of losing the spark of revival and recognition of the contemporary work of the Holy Spirit (Knoll 1992:381).

* An enthusiastic embrace of a restorationist dream for Christianity, seeking to return to the life of apostolic faith and first century practices (Blumhofer 1993: 1, 4).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Revival worship services at The Azusa Street Mission were scheduled for 10:00 a.m., noon and 7:00 p.m., but they frequently ran  together, making them continuous. Occasionally they ran through the night. Services were held seven days a week during much of the duration of the revival (Cauchi 2004).

together, making them continuous. Occasionally they ran through the night. Services were held seven days a week during much of the duration of the revival (Cauchi 2004).

There was no order of service, usually no instruments to accompany music, and often no obvious individual leadership or sermon. Frequently Seymour would simply come in, open a Bible on the cloth covered plank altar, and then sit down, covering his head with a shoe box while he prayed. Testimony, periods of silence, prayer and music would proceed spontaneously. Attendees described the services as being led by the Holy Spirit. There was a receptacle at the rear of the church for those who wished to contribute, but there was no offering taken (Cauchi 2004).

The atmosphere was very highly charged, emotionally intense. People were packed tightly, often swaying in ecstatic prayer, some dancing in joy. Many people would shout throughout the meeting and some would moan while others would fall on the floor in a trance, “slain in the spirit.” The singing was sporadic, usually a cappella, repetitive (there were no hymnals) and not infrequently in tongues. There were repeated altar calls for salvation, sanctification, healing and baptism of the Holy Spirit. Prayers of thanksgiving were usually loud and frequently in tongues. On occasion, those feeling a particular urgency would move, sometimes with one or two of the leaders, to an upstairs room where they could pray with more focus and intensity, often for healing. The meetings lasted as long as there was anyone in the room with anything to say or testimonial letters to read (Blumhofer 1993:59; Cauchi 2004; “Weird Babel of Tongues” 1906:1).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The leadership of the Azusa Street Revival was largely informal and consisted of predominantly female volunteers who gathered around William Seymour. Only a few have been personally identified. Prominent figures who have been identified during the revival period would include Jennie Evans Moore, Lucy Farrow, Julia Hutchens, Frank Bartleman, Florence Louise Crawford, and Clara Lum. There was also a governing board of twelve, and it is worth noting that half or more of the members of this group also were women (“Women Leaders” n.d.; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; Cauchi 2004).

After Seymour himself, the first person with known leadership status was Jennie Evans Moore, a convert made in the very early prayer meeting days on Bonnie Brae Street. It has been often reported that when she was “baptized in the spirit” she became able to play the piano, which she had been unable to do previously. She continued to exercise this gift her whole life. She later became Seymour’s wife and evidently played a supporting role, although she did sometimes preach when Seymour was not present. Moore remained as pastor of the Azusa Street Apostolic Faith Holiness Mission after Seymour died in 1922. An early convert, Edward Lee, with whom Seymour lodged, and Richard and Ruth Asberry, in whose home the revival actually began, also remained involved (“History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; Cauchi 2004).

Very soon after the prayer meetings began to take hold, Seymour asked Parham for help, specifically for his friend Lucy Farrow. Parham responded affirmatively and sent Farrow to Los Angeles. All that is known about Lucy Farrow’s background is that she was born into slavery in Virginia and that she was a niece of the black abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Prior to her arrival in Houston about 1890, she had lived in Mississippi. She had given birth to seven children, only two of whom lived, and was a widow by the time she met Seymour. She was about 55 years old and the pastor of a small, black Holiness church in the Houston area at the time. She also worked as a governess and cook for Charles Parham’s family. Seymour came to Houston, looking for relatives, in1903 and joined her church. He served, at her invitation, as interim pastor of her church while she traveled back to Galena, KS with the Parham family. It was on this trip that she had her “baptism of the spirit.” Farrow joined Seymour during the Bonnie Brae period, and was the person who laid hands on Seymour at the time of his “baptism of the spirit”. She continued to participate in the revival at Azusa Street for about four months before traveling with Julia Hutchins to Liberia as a Missionary. Farrow eventually returned to Azusa to live in a “faith cottage” behind the main building, and to pray and minister to those seeking deeper faith. She later returned to Houston to live with a son and died there in 1911 (Cauchi 2004; “The Life and Ministry of Lucy Farrow” n.d.; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.)

Julia Hutchens was a member of the Second Baptist Church of Los Angeles when she learned the Holiness message at a revival meeting. She began to teach Holiness beliefs to others in her congregation, and eventually she and eight families were expelled from their church as a result. They began to meet as a Holiness mission on Santa Fe Street, possibly associated with the Church of the Nazarene. Neely Terry was a member of that group. Not being a minister herself, Hutchins felt the need for someone to help her. Terry recommended Seymour whom she had met at Farrow’s church in Houston while visiting relatives there. While she was initially reluctant to embrace the concept of tongues and “spirit baptism,” she soon had the experience at the Bonnie Brae Street meetings. Hutchens then joined in the Revival, along with her congregation. She later traveled to Liberia with Lucy Farrow (Cavaness n.d.; Cauchi 2004; “The Road to Azusa” n.d.).

Frank Bartleman, an itinerant evangelist who was originally from Pennsylvania, by the time of the Azusa Street Revival had developed a pattern of being ready to go anywhere the Lord called, but not for very long. He had been licensed to preach in a Baptist church in his home state, but in the meantime had drifted in a distinctly Holiness direction. He had most recently been involved in street missions in Los Angeles, but he had also recently developed a reputation among Holiness publications as a reliable and inspired journalist. He had also started publishing and distributing tracts on Holiness subjects. Bartleman was drawn to Azusa Street as soon as he heard about it and soon became involved in publicizing it. Within a few weeks of his involvement, the San Francisco earthquake struck. Bartleman quickly prepared a tract linking the two by suggesting that both were God’s action in the world and also that the earthquake had been predicted in prophecy at Azusa. The pamphlets were widely circulated and were probably responsible for an early increase in attendance and media attention for the revival. Unlike the pattern he had established earlier, Bartleman remained at Azusa for some time before returning to itinerancy. Using diaries he had kept at Azusa, Bartleman wrote a number of articles and books including How Pentecost Came to Los Angeles (1925). He died in 1936 (Goff 1988:114; Cauchi 2004).

Florence Louise Crawford, the mother of two and the wife of a building contractor, had been active in social work and women’s organizations in spite of suffering from a childhood injury and spinal meningitis. She assumed a leadership role in Azusa, working on the newspaper and organizing branches in Seattle and Portland, Oregon. She later left her husband, returned to the Oregon mission, developed it into the Apostolic Faith denomination, and became its general overseer for the rest of her life. She was joined in this work by Clara Lum (Cauchi 2004).

Clara Lum, also a white woman, was a stenographer and may have served as Seymour’s secretary. She was instrumental in founding the mission’s newspaper, Apostolic Faith, and was evidently in love with Seymour. A publication of Florence Crawford’s Apostolic Faith denomination reports that Charles Harrison Mason, founder of the Church of God in Christ, advised Seymour not to marry her, evidently because of the scandal that an interracial marriage would cause. No biographical information is available on her, but when Seymour married Jennie Evans Moore, she left Azusa Street to join Florence Crawford in Oregon, taking with her the mailing list for the Apostolic Faith newspaper, which they continued. However, they used the Portland mission’s address for donations and did not mention Azusa Street, thereby cutting off much of Seymour’s access to publicity and financial support (Cauchi 2004; “Failed Inter-racial Love Interests” n.d.; “The Apostolic Faith” 2004-2011).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The early challenge to the Azusa Street Revival was simply doctrinal, but as the revival began to develop the criticism grew apace. If the happenings on Azusa Street scandalized its critics, their comments tended toward the intemperate at very least. When William Seymour reached Los Angeles in 1906 he went almost immediately to the small Holiness mission on Santa Fe Street to which he had been invited. The church was affiliated with the Southern California Holiness Association. That first Sunday Seymour preached Parham’s apostolic faith message, including tongues as evidence of “spirit baptism”. When he returned the next week, he found the door padlocked against him. It turns out that even though Neely Terry had heard Seymour preach Parham’s message in Texas, and had convinced Julia Hutchins to invite him, when Hutchins and her church elders actually heard the message, they was uncomfortable and expressed their reservations to the Holiness Association. That group also found the “new thing” Seymour preached to be contrary to Holiness doctrine that sanctification and “baptism with the spirit” were the same thing. They were also concerned because Seymour himself had not yet had the experience (“Bishop William J. Seymour” 2004-2011; Pete 2001-2012).

Seymour was staying with a member of the congregation, Edward Lee. Lee, Terry, Terry’s cousin, Richard Asberry, and his wife, Ruth, along with several others did not support Seymour’s banning. This small group began to gather for “prayer meetings,” soon moving to the Asberry’s Bonnie Brae address where the revival began to take hold. Lee was among the first to speak in tongues. He was followed by Jennie Evans Moore, a neighbor (later Seymour’s wife) and eventually by Julia Hutchins. A few days later, so did Seymour, which ended that initial controversy (“Bishop William J. Seymour” 2004-2011; Cavaness, Barbara. n.d.)

However, soon after the move to Azusa Street, criticism heated up again. The Los Angeles Times headed its story “Weird Babel of Tongues” and continued, “Breathing strange utterances and mouthing a creed which it would seem no sane mortal could understand, the newest religious sect has started in Los Angeles.” Another newspaper reported “…disgraceful intermingling of the races…they cry and make howling noises all day and into the night. They run, jump, shake all over, shout at the top of their voice, spin around in circles, fall out on the sawdust blanketed floor jerking, kicking and rolling all over it.….These people appear to be mad, mentally deranged or under a spell. They claim to be filled with the spirit. They have a one eyed, illiterate, Negro as their preacher who stays on his knees much of the time with his head hidden…. They repeatedly sing the same song, ‘The Comforter Has Come’.” Indeed, those attending the revival were popularly referred to as “Holy Rollers” and “Tangled Tonguers” (“Weird Babel of Tongues.” The Los Angeles Daily Times 1906; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; Wilson 2006).

Charles Parham himself, when he visited some weeks later was even less charitable. “Men and women, whites and blacks, knelt together or fell across one another; a white woman, perhaps of wealth and culture, could be seen thrown back in the arms of a big ‘buck nigger,’ and held tightly thus as she shivered and shook in freak imitation of Pentacost. Horrible, awful shame.” Parham was quickly “uninvited” to the Azusa Street services and subsequently attempted, with little success, to start a competing revival nearby. Mainstream churches and religious leaders, often through denominational publications, were also frequently critical, some on the basis of specifically conflicting theology, others of the revival’s decorum (Goff 1988:130, 132, 133; “History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; “Azusa Street Critics” 2004-2011).

While the revival thrived for three years amid a variety of criticisms, it ultimately dissolved into a number of early divisions, a pattern that continued for a number of years. Particularly frustrating for some was the fact that racial separation returned very quickly, with many of the black converts joining Charles Mason’s branch of The Church of God in Christ which remains today one of the largest predominantly black denominations. White converts, through a series of small denominations, eventually founded the Assemblies of God, the largest single Pentecostal denomination. There were early divisions even within this group, however, and several other large Pentecostal denominations resulted. Although the revival itself did not survive, virtually all contemporary Pentecostals and Charismatics in other denominations consider Azusa Street to be their source. Today there are at least five hundred million Pentecostals and Charismatics in the world, which may comprise as much as one quarter of all Christians, and collectively they constitute the fastest-growing segment of Christianity (“History of the Azusa Street Revival” n.d.; Holstein 2006; Blumhofer 2006).

REFERENCES

“Azusa Street Critics.” n.d. 312 Azusa Street. Accessed at http://www.azusastreet.org/AzusaStreetCritics.html on 26 April 2012.

Bartleman, Frank. 1925. How Pentecost Came to Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Frank Bartleman.

“Bishop William J. Seymour.” n.d. 312 Azusa Street. Accessed at http://www.azusastreet.org on 20 April 2012.

Blumhofer, Edith. 2006. “ Azusa Street Revival.” Azusa Street Mission. Accessed at http://www.religion-online.org showarticle.asp? title 3321 on 8 April 2012.

Blumehofer, Edith. 1993 Restoring the Faith Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Cauchi, Tony. 2004. “William Seymour and the History of the Azusa Street Outpouring.” Revival Library. Accessed at http://www.revival – library.org/pensketches/am…/Seymourazusa.html.

Cavaness, Barbara. n.d. “Spiritual Chain Reactions: Women Used of God.” The Network. Accessed at www.womeninministry.ag.org/history/spiritual_chain_reactions.cfm on 26 April 2012.

Dove, Stephen. 2009. “Hymnody and Liturgy in the Azusa Street Revival 1906 – 1908.” Pneuma 31 (2). Accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10 on 25 April 2012.

“Failed Inter-racial Love Interests Could Have Led to Demise of Azusa Street Revival.” n.d. Metropolitan Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction C.O.G.I.C. Accessed at http://www.azusa.mejcogic.org/apostolicfaithpub.html on 27 April 2012.

Goff, James R., Jr. 1988. Fields White Unto Harvest. Fayettville: University of Arkansas Press.

“History of the Azusa Street Revival.” n.d. Friendly Church of God in Christ. Accessed at http://www.friendlycogic.com/azusa/azusa on 6 April 2012.

Holstein, Joanne. 2006. “ Azusa (A susa) Street Revival.” Becker Bible Studies. Accessed at http://www.guidedbiblestudies.com/library/asusa_street_revival. htm on 25 April 2012.

Knoll, Mark A. 1992. A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Knoll, Mark A..2002. The Old Religion in a New World. Grand Rapids, MI/ Cambridge, UK: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Pete, Reve’ M. 2001-2012. “African-Americans of the Holiness Movement.” In The Impact of Holiness Preaching as Taught by John Wesley and the Outpouring of the Holy Ghost on Racism, Chapter 8. Accessed at http://www.revempete.us/research/holiness/africanamericans. Html on 26 April 2012.

“The Apostolic Faith.” 2004 – 2012. 312 Azusa Street. Accessed at :www.azusastreet.org/TheApostolicFaith.htm on 27 April 2012.

“The Life and Ministry of Lucy Farrow.” n.d. Zion Christian Ministry. Accessed at http://www.zionchristianministry.com/azusa/the-life-and-ministry-of-lucy-farrow/ on 26 April 2012.

“The Road to Azusa.” n.d. Metropolitan Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction C.O.G.I.C. Accessed at http://www.azusa.mejcogic/roadazusa.html on 22 April 2012.

“Weird Babel of Tongues.” 1906. The Los Angeles Daily Times. April 18, 1906. Accessed at http://312azusastreet.org/beginnings/latimes.htm.

Wilson, Billy. 2006. “The Miracle on Azusa Street.” The 700 Club. Accessed at http://www.cbn.com/700 club/bios/billywilson 030706.aspx on 13 June 2012.

“Women leaders.” n.d. Scattered Christians. Accessed at http://www.scatteredchristians.org/Pentecostal Women.html on 27April 2012.

Post Date:

17 June 2012

model. Many came to know Keegan through his childhood acting roles in popular hits such as 10 Things I Hate About You, with Heath Ledger, and Seventh Heaven. A teenage heartthrob, Keegan went on to play less significant roles in his early adulthood. Keegan has also operated a nightclub and invested in real estate (Brown 2015).

model. Many came to know Keegan through his childhood acting roles in popular hits such as 10 Things I Hate About You, with Heath Ledger, and Seventh Heaven. A teenage heartthrob, Keegan went on to play less significant roles in his early adulthood. Keegan has also operated a nightclub and invested in real estate (Brown 2015). in a cyclical manner but inside is the present moment (Kuruvilla 2014). As Keegan puts it: “Synchronicity. Time. That’s what it’s all about. Whatever, the past, some other time. It’s a circle; in the center is now. That’s what it’s about,” Keegan explained, regarding the church’s name, Full Circle (Brpwm 2015). Members join together in live music, yoga, meditation and group workshops all focused on the impact of their group energy. The practice of “activated peace” is their way of using their positive energy to change the world. The group incorporates a combination of Hinduism practices and icons with new age theology.

in a cyclical manner but inside is the present moment (Kuruvilla 2014). As Keegan puts it: “Synchronicity. Time. That’s what it’s all about. Whatever, the past, some other time. It’s a circle; in the center is now. That’s what it’s about,” Keegan explained, regarding the church’s name, Full Circle (Brpwm 2015). Members join together in live music, yoga, meditation and group workshops all focused on the impact of their group energy. The practice of “activated peace” is their way of using their positive energy to change the world. The group incorporates a combination of Hinduism practices and icons with new age theology.

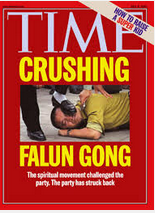

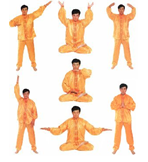

Li Hongzhi ( 李洪志) in May 1992. It was part of the “qigong boom” (qigong re 气功热 ), a mass movement that spanned the 1980s and 1990s and was extremely popular, particularly in urban China. Qigong (“the discipline of the vital breath”) is a varied set of practices based on the belief that practitioners can, through gestures, meditation, and visualization, mobilize the vital breath (qi) in their bodies to achieve greater physical and mental health. Although such beliefs and practices have ancient roots, modern qigong is an invention of the twentieth century and was systematized in the early 1950s as part of the creation of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the People’s Republic of China (Palmer 2007).

Li Hongzhi ( 李洪志) in May 1992. It was part of the “qigong boom” (qigong re 气功热 ), a mass movement that spanned the 1980s and 1990s and was extremely popular, particularly in urban China. Qigong (“the discipline of the vital breath”) is a varied set of practices based on the belief that practitioners can, through gestures, meditation, and visualization, mobilize the vital breath (qi) in their bodies to achieve greater physical and mental health. Although such beliefs and practices have ancient roots, modern qigong is an invention of the twentieth century and was systematized in the early 1950s as part of the creation of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the People’s Republic of China (Palmer 2007). derable powers: he claimed to be able to cleanse their bodies, among other ways, by installing a perpetually revolving wheel in their stomach. Li’s miraculous powers were different from those of other masters in that they happened at an unseen level, and relied on faith rather than works. Li’s efforts met with great success. Between 1992 and the end of 1994, he toured China, wrote and sold books, and built a nation-wide organization of followers that numbered in the tens of millions (Penny 2003).

derable powers: he claimed to be able to cleanse their bodies, among other ways, by installing a perpetually revolving wheel in their stomach. Li’s miraculous powers were different from those of other masters in that they happened at an unseen level, and relied on faith rather than works. Li’s efforts met with great success. Between 1992 and the end of 1994, he toured China, wrote and sold books, and built a nation-wide organization of followers that numbered in the tens of millions (Penny 2003). o have defenders in high places. Falun Gong practitioners reacted to media criticism by organizing non-violent demonstrations at the television stations or newspapers that had criticized them, asking for a retraction or equal time. This is not common practice in China, yet there were some 300 such demonstrations between 1996 and 1999, and Falun Gong practitioners seem to have emerged victorious more often than not. These demonstrations form the background to the huge event that changed the history of Falun Gong. On April 25, 1999, some 20,000 Falun Gong practitioners appeared outside the gates to Zhongnanhai (中南海), the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing. The demonstration was prompted by police intervention and reported brutality in the neighboring city of Tianjin, where Falun Gong practitioners had protested at a university a few days earlier (Tong 2009).

o have defenders in high places. Falun Gong practitioners reacted to media criticism by organizing non-violent demonstrations at the television stations or newspapers that had criticized them, asking for a retraction or equal time. This is not common practice in China, yet there were some 300 such demonstrations between 1996 and 1999, and Falun Gong practitioners seem to have emerged victorious more often than not. These demonstrations form the background to the huge event that changed the history of Falun Gong. On April 25, 1999, some 20,000 Falun Gong practitioners appeared outside the gates to Zhongnanhai (中南海), the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party in Beijing. The demonstration was prompted by police intervention and reported brutality in the neighboring city of Tianjin, where Falun Gong practitioners had protested at a university a few days earlier (Tong 2009). (the main sites are falundafa.org and en.minghui.org). They have pursued China’s leadership through the legal systems of various countries and through international institutions like the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the International Criminal Court. They have hacked into television programming in China to present their own version of the truth about Falun Gong. The Chinese government has responded to these efforts by continuing the campaign of suppression. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International continue to report that Falun Gong practitioners are subject to arrest and torture; charges of organ harvesting of Falun Gong prisoners remain controversial, but are no longer dismissed out of hand.

(the main sites are falundafa.org and en.minghui.org). They have pursued China’s leadership through the legal systems of various countries and through international institutions like the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the International Criminal Court. They have hacked into television programming in China to present their own version of the truth about Falun Gong. The Chinese government has responded to these efforts by continuing the campaign of suppression. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International continue to report that Falun Gong practitioners are subject to arrest and torture; charges of organ harvesting of Falun Gong prisoners remain controversial, but are no longer dismissed out of hand. e course of the conflict between Falun Gong and Chinese authorities. The messianic and apocalyptic elements in Li’s writings have become increasingly prominent in practice over the years (Penny 2012).

e course of the conflict between Falun Gong and Chinese authorities. The messianic and apocalyptic elements in Li’s writings have become increasingly prominent in practice over the years (Penny 2012).