BROTHERHOOD OF ETERNAL LOVE TIMELINE

1965 (Fall): John Griggs robbed a Hollywood producer of LSD. He used the psychedelic drug for the first time shortly thereafter.

1966 (October 11): Brotherhood of Eternal Love registered as a church in California, with LSD used as a sacrament.

1966 (December): Brotherhood would move to Laguna Beach after a fire burned down their church in Modjeska Canyon

1968 (December): The United States Senate amended the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to ban LSD from use.

1968 (December 26): Timothy Leary was arrested in Laguna Beach for marijuana possession.

1969 (August 26): John Griggs died of what many believed to be an overdose; he was twenty-five years old.

1970 (September 12) Leary broke out of prison, with the help of the group the Weather Underground. The Brotherhood financed most of the operation.

1970 (September 12): President Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act into law.

1970 (December 25-28): “The Christmas Happening” concert took place, where the Brotherhood dropped 25,000 tablets of LSD onto the crowd. It marked a more concerted effort by law enforcement to bring about the end of the Brotherhood and the counterculture.

1972 (August 5): The Brotherhood of Eternal Love Task Force raided establishments all across the West Coast, arresting fifty-three Brotherhood members and confiscating millions of dollars-worth of contraband.

1973 (July 1): The Drug Enforcement Administration was formed as the overarching drug control apparatus for the U.S. Government.

1973 (October 3): A U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing, entitled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” presented the extensive drug smuggling operation of the group. For many, this was considered the end of the Brotherhood’s group.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was founded on the idea that the psychedelic drug, LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), was a sacrament to bring people closer to God. For many of the groups’ apostles, LSD helped them gain a greater awareness of the love and wisdom inherent in the universe. The Brotherhood’s spiritual ethos, which to outsiders was nothing more than drug-infused debauchery, was rooted in the belief that traditional religions had done little to help society. In particular, the 1950s and 1960s were marked by fear, paranoia, and chaos as numerous global conflicts raged (be it the Cold War or the war in Vietnam), as well as the countless other struggles for freedom in the U.S. and parts of the decolonizing world. Born from the the cultural and social chaos of the counter-culture movement of the 1950s and 1960s in the U.S., the Brotherhood would eventually have a monumental impact on the use of psychedelic drugs as either a form of social and cultural resistance or revival.

The Brotherhood was largely a byproduct of the life of John Griggs. Griggs was a seemingly unlikely figure to be considered the founder of a religious group proselytizing the use of LSD as a conduit for the spread of love and spiritual awakening. Growing up in southern California, Griggs was described by many as a fighter. As leader of the gang, the Blue Jackets, Griggs spent many of his teenage years patrolling Anaheim, California looking to fight, and years later, as a member of the gang, the Street Sweepers, John spent numerous marijuana-fueled evenings racing cars and terrorizing passers-by (Brotherhood of Eternal Love1 n.d.) Street-fighting and illegal drag racing had their limitations however; Griggs wanted more. It was during the mid-60s that Griggs shifted focus, and endeavored to become one of the largest marijuana dealers in southern California. Griggs, along with Eddie Padilla, another founding member of the Brotherhood, began smuggling marijuana from Mexico and selling in Anaheim. (Schou 2010)

But in 1965, John Griggs would have an awakening of sorts. Griggs, who was using marijuana and heroin heavily, had heard of a drug more powerful than both drugs: LSD. John was intrigued, and he took it upon himself to find some. Rumors spread of a Hollywood film producer who kept a large stash of acid on the top of his refrigerator. One night, a cohort and Griggs showed up at the producer’s home, and robbed him at gunpoint, only stealing the LSD. (Schou 2010) The group drove into the California desert and proceeded to take a massive dose of LSD. Almost overnight, Griggs transformed from a rough-housing street fighter and drug-peddler into a missionary of psychedelic drugs.

Contrary to popular ideas about drug use at the time, that people only used drugs to party, or for “kicks,” Griggs fascination with LSD was rooted in his belief that it led him to God. As Brotherhood member Dion Wright wrote:

Whatever John’s religious and spiritual roots may have been, they kicked into overdrive. He came back into this plain of objectivity with a single conviction: ‘Its God! Its all God!…The bedrock realization never left him (Maguire and Ritter 2014).

Griggs religious conviction only grew with time. Not long after discovering LSD, Griggs contracted Hepatitis from his previous heroin use, and was hospitalized. Griggs claimed to have gone through a near-death experience and that LSD had helped him feel “for the first time a powerful and humbling connection to a greater life force in the universe.” (Schou 2010) Once recovered, Griggs spread the word on the gospel of acid. His transformation centered largely on the belief that through the healing powers of LSD they could create a utopian society. Only a few months after Griggs first was revealed, to what Aldous Huxley called the “doors of perception,” would he make it his life’s work to recruit any and all people to this new higher calling. (Huxley 1954)

Eddie Padilla, like many others, was converted to the gospel of LSD. Padilla lived a rebellious life, often getting into trouble with law-enforcement, but through LSD, he found meaning and purpose. Padilla regularly accompanied Griggs to Tahquitz Canyon, near Palm Springs, to drop acid. It was there that they both increasingly believed that LSD could help people struggling with drug abuse or living a life of crime. With an evangelical zeal, Griggs and Padilla worked tirelessly to expose anyone they possibly could to the drug. They soon led communal excursions into the desert to take acid, often referring to the weekly trips as “church.” Rick Bevan, a surfer from Garden Grove, fit the profile of the type of person who could benefit from “church” with Padilla and Griggs. Bevan started taking acid with them following a stint at a work camp for delinquent juveniles. Bevan’s description of the experience is indicative of why many young people in southern California were drawn to Griggs and the sacrament of LSD, and saw these trips as something much greater than themselves. As Bevan explains:

The house had all these Buddhist statues in it, and he had incense burning and was meditating. I just wanted to get drugged out…I just broke through right away, it wasn’t like discovering something about yourself for the first time, it was like remembering something that you hadn’t remembered your whole lifetime, remembering something form a previous lifetime…We were experiencing a whole new viewpoint of life that was beautiful and loving and caring of others and the whole world, we felt connected to the source of all life. We were plugging into that source on a weekly basis (Schou 2010).

The groups started to meet on Wednesdays to help those who had reverted to conventional bad habits of drinking and using drugs. As the groups grew in size many of the members started to refer to themselves as Disciples. Griggs took it upon himself to spread the gospel further, and utilized the United States loose laws regarding tax-exempt status for churches to his advantage.

On October 26, 1966, Brotherhood member Glenn Lynd filed paperwork incorporating the Brotherhood of Eternal Love as a non-profit in the state of California. The group had become a church, with Griggs their prophet, and LSD their sacrament. The objective of the church was to “bring to the world the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Paramahansa Yoganada, Mahatma Gandhi, and all the true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men”(Lee and Shlain 1992) The timing of the Brotherhood’s incorporation, however, would have a major impact on its future, as it would put the church and its holy sacrament, at odds with California law. Fifteen days before the group filed paperwork the California state legislature banned LSD. The confluence of legal and cultural issues surrounding LSD would make it increasingly difficult for the Brotherhood to execute their divine vision for the future of the world.

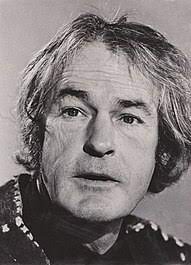

Shortly after their incorporation, the Brotherhood moved to Laguna Beach, south of Los Angeles. Laguna was ideal for the Brotherhood; the beautiful beaches were popular among surfers, artisans, and a growing  bohemian hippie community. They set up a store front called Mystic Arts World and sold various products that catered to the growing psychedelic subculture. It seemed that the Brotherhood and its gospel of love and LSD was gaining traction, but to grow even further, they would need legitimation of a grander sort. Griggs began to recruit of one of the most infamous counter-cultural icons of the 1960s, Timothy Leary, the High Priest of LSD. [Image at right] Leary’s role as icon of the hippie movement was more mundane and “square” in its origins; he started his career as a Harvard University psychologist who, after a series of failed marriages began to second-guessing his career, eventually compelling him to experiment with hallucinogenic mushrooms. The trip fundamentally transformed Leary’s life, describing it as “the deepest religious experience of my life.” (Lee and Shlain 1992) Leary tried to incorporate his growing belief in the power of psychedelics with his academic work, to no avail; he would be fired from Harvard for giving LSD to undergraduates. However, Leary could not be constrained by the conventions of the ivory tower, as his books, The Psychedelic Experience (1964) and Turn On, Tune In, and Drop Out (1966), and his popular phrase, “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” catapulted him to global fame (Leary 1970). By 1966, Leary, continued his psychedelic experimentation at the estate of the heirs to the Mellon fortune in Millbrook, NY, and cemented his status as one of the most important figures of the 1960s counter-cultural movement (Greenfield 2006).

bohemian hippie community. They set up a store front called Mystic Arts World and sold various products that catered to the growing psychedelic subculture. It seemed that the Brotherhood and its gospel of love and LSD was gaining traction, but to grow even further, they would need legitimation of a grander sort. Griggs began to recruit of one of the most infamous counter-cultural icons of the 1960s, Timothy Leary, the High Priest of LSD. [Image at right] Leary’s role as icon of the hippie movement was more mundane and “square” in its origins; he started his career as a Harvard University psychologist who, after a series of failed marriages began to second-guessing his career, eventually compelling him to experiment with hallucinogenic mushrooms. The trip fundamentally transformed Leary’s life, describing it as “the deepest religious experience of my life.” (Lee and Shlain 1992) Leary tried to incorporate his growing belief in the power of psychedelics with his academic work, to no avail; he would be fired from Harvard for giving LSD to undergraduates. However, Leary could not be constrained by the conventions of the ivory tower, as his books, The Psychedelic Experience (1964) and Turn On, Tune In, and Drop Out (1966), and his popular phrase, “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” catapulted him to global fame (Leary 1970). By 1966, Leary, continued his psychedelic experimentation at the estate of the heirs to the Mellon fortune in Millbrook, NY, and cemented his status as one of the most important figures of the 1960s counter-cultural movement (Greenfield 2006).

John Griggs revered Leary, and believed he would provide both guidance and legitimacy to the Brotherhood’s cause. In 1966, Griggs drove cross-country to Leary’s compound in Millbrook, NY. He was granted an audience with Leary, an event that played a major role in convincing Griggs to incorporate the Brotherhood of Eternal Love as a church. Griggs seemed to make an impression on Leary and invited him to move to the  west coast. Leary, who was facing mounting law enforcement pressure in New York, would eventually move to Laguna Beach in 1966. In Laguna, Leary and his family took root, hosting psychedelic sessions and lectures at the Mystic Arts World on Leary’s popular catchphrase: “turn on, tune in, and drop out” (Greenfield 2006). [Image at right] Leary settled into his role as the spiritual guru, bringing both academic clout and a “pop-star” like presence to the west coast, and it certainly gave the Brotherhood a sense of visibility that they didn’t have before (Schou 2010). Griggs and Leary’s relationship was mutually beneficial as they worked together to hatch a plan to find a property that would help them and others to “drop out” of society, but they did have disagreements as to where. Griggs, and much of the Brotherhood, had always envisioned buying an island utopia somewhere in the South Pacific; Leary, on the other hand, wanted to stay on the mainland. Many members of the Brotherhood believed Leary wanted to stay on the mainland to be closer to media and publicity in order to take psychedelics mainstream. Eventually, the Brotherhood used their money to buy a ranch north of Palm Springs, and named it the Idyllwild ranch. The purchasing of the ranch foreshadowed the divergent views within the Brotherhood, as it became increasingly muddled by Leary’s fame, money from the drug trade, and the ambitions to transform society (Schou 2010).

west coast. Leary, who was facing mounting law enforcement pressure in New York, would eventually move to Laguna Beach in 1966. In Laguna, Leary and his family took root, hosting psychedelic sessions and lectures at the Mystic Arts World on Leary’s popular catchphrase: “turn on, tune in, and drop out” (Greenfield 2006). [Image at right] Leary settled into his role as the spiritual guru, bringing both academic clout and a “pop-star” like presence to the west coast, and it certainly gave the Brotherhood a sense of visibility that they didn’t have before (Schou 2010). Griggs and Leary’s relationship was mutually beneficial as they worked together to hatch a plan to find a property that would help them and others to “drop out” of society, but they did have disagreements as to where. Griggs, and much of the Brotherhood, had always envisioned buying an island utopia somewhere in the South Pacific; Leary, on the other hand, wanted to stay on the mainland. Many members of the Brotherhood believed Leary wanted to stay on the mainland to be closer to media and publicity in order to take psychedelics mainstream. Eventually, the Brotherhood used their money to buy a ranch north of Palm Springs, and named it the Idyllwild ranch. The purchasing of the ranch foreshadowed the divergent views within the Brotherhood, as it became increasingly muddled by Leary’s fame, money from the drug trade, and the ambitions to transform society (Schou 2010).

For Griggs, and the Brotherhood, who lacked the international cachet of Leary, if not notoriety, the ambition to create a new global utopia, with LSD as its sacrament, required a much more ambitious and grander plan. By late 1966, and early 1967, the Brotherhood realized that Mystic Arts World, while providing consistent income, was not enough to purchase land and supplies for their growing membership. Furthermore, the Brotherhood needed money to finance their properties at Idyllwild and Laguna, as well as their growing membership. The answer to their financial issues lay in the illicit drug trade, something with which both Griggs and Eddie Padilla had experience. Soon Mystic Arts World became a depot for illicit drug sales; members of the Brotherhood began trafficking kilos of marijuana from Mexico, or buying LSD in San Francisco, to sell in Laguna. But the big money lay beyond California. Some, like Glenn Lynd, began trafficking marijuana to New York City, moving hundreds of kilos from the Arizona-Mexico border to Manhattan (Schou 2010).

Other Brotherhood members, like David Hall, began moving drugs on a global scale. He first started trafficking weed in planes from Mexico, realizing the real money lay across the ocean. Rick Bevan and Travis Ashbrook, both avid cannabis users, became infatuated with hashish from Asia; that infatuation proved both profitable and perilous for the Brotherhood. In late 1967, Bevan and Ashbrook flew to Munich, Germany, purchased a car, and began the long journey east to Katmandhu, Nepal, which was later known as the “Hippie Trail.” But they never made it Nepal. To make big money in the drug business, one needed to find a cheap source for the drug, and that was Afghanistan. For many hippies and drug traffickers, Afghanistan was a drug paradise as Afghanistan had some of the best, and cheapest, hashish in the world (Bradford 2019). Bevan and Ashbrook’s first trip to Kandahar, Afghanistan yielded eighty-seven pounds of hash, and tens of thousands of dollars in profit. Not long after, Laguna Beach was flooded with some of the best hash in the world, and the Brotherhood with newfound wealth (Maguire and Ritter 2014). Given its high-quality product, as well as loose enforcement of anti-drug laws, Afghanistan would become the primary source of hashish for the Brotherhood throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bradford 2019).

By the summer of 1967, the hippie movement had reached an apex in California, culminating in what was known as “the Summer of Love.” More than a hundred thousand people converged on the Bay area, especially the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, embracing sex, drugs, and rock-n-roll. The growing music scene proved essential to the growing nexus of drug use and the counterculture. An example of this was in Timothy Scully, partner chemist with Nick Sand, who lived with the infamous Ken Kesey and Merry Pranksters. As detailed in Tom Wolfe’s, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Kesey gave LSD to hundreds, if not thousands, of people in what were known as the “acid-tests.” The musical group, the Grateful Dead, became an integral part of the “Palo Alto scene” where the Pranksters resided, often combining their “wall of sound” concerts with taking LSD (Wolfe 1968). In June 1967, at the Monterey International Pop Festival, artists like the Who, Jefferson Airplane, the Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, and the Grateful Dead played to thousands of revelers and fans fueled by LSD. Naturally, most of the artists partook as well. Most of the acid was supplied by the Brotherhood. The Summer of Love, and the myriad of live concerts that followed throughout the 1960s, provided a blueprint for the Brotherhood to expand their brand; members often dressed in orange jumpsuits would pass out Orange Sunshine at concerts by the fistful (Schou 2010).

Although the hash trade was lucrative for the Brotherhood, it did not have the sentimental value of LSD, as LSD was, in many ways, the life blood of the group. Thus, the Brotherhood remained ever-entangled in the world of LSD production and distribution; this would lead the group to Nick Sand. Like Leary and members of the Brotherhood, Sand was converted to the gospel of psychedelics after a trip of mescaline in 1961, and shortly after became one of the most notorious chemists in American history, producing much of the LSD that fueled the counterculture movement in California. (Brotherhood of Eternal Love2 n.d.) In 1968, Sand, who had been producing LSD from his farmhouse in Windsor, California, first met John Griggs and Timothy Leary. The meeting between the “outlaw chemist” and two of the most prominent figures of the psychedelic movement in California, would be transformative. Sand had produced an incredibly potent type of LSD, which after using Griggs, dubbed “Orange Sunshine.” At the time, it was believed to be the most powerful LSD ever made. Sand would end up making Sunshine exclusively for the Brotherhood and the impact was monumental; within a half-year he produced nearly 3,600,000 tablets of the drug (Brotherhood of Eternal Love2 n.d.). Unlike hashish, which was the drug that would finance their movement, Orange Sunshine was the drug that was seen as instrumental to the creation of a global utopia. In turn, many in the Brotherhood gave the drug away, rather than sell it, even though some believed they could have made a fortune in the LSD business (Schou 2010). But as the counter-culture movement grew, so too did knowledge of LSD and Orange Sunshine. It wasn’t long before the Brotherhood’s most famous drug sparked the moral panic that would bring it to its end.

On August 26, 1969, John Griggs died of an apparent overdose; he was twenty-five years old. In many ways, Griggs death marked a divergence in the various forces at play within the LSD-fueled counter-culture scene in California, but especially the Brotherhood. While the profits from drug sales at Mystic Arts World and concerts helped finance Brotherhood ambitions, the money was seductive. For some members of the Brotherhood, the drug business had become more important than the mission. Moreover, the growing role of the Brotherhood in both the LSD and hashish trade was increasingly apparent to law-enforcement. For Neil Purcell, an enterprising young patrol officer in Laguna Beach in 1968, the constant influx of hedonistic and LSD-fueled hippies was driven by Leary and the Brotherhood; they then became the primary target of police. Things would come to a head on December 26, 1968, when Purcell pulled Leary over and arrested him for marijuana possession; Leary was sentenced to one to ten years in prison. Although, the arrest of Leary was a victory for law enforcement, the war between the Brotherhood and police was only beginning. On the night of September 12, 1970 Leary broke out of prison, with the help of the anti-government group the Weather Underground. The Brotherhood played a vital role in the prison break: they had launched a “Free Timothy Leary” fundraising campaign, and helped finance his escape to Canada and eventually to Algeria (Schou 2010).

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, as the Brotherhood continued to supply most of the LSD and hashish to California, and aided in the high-profile escape of Leary, police pressure increased dramatically. Many Brotherhood members, including Griggs, and the Mystic Arts World, were under constant police surveillance (Schou 2010). The threat posed by police prompted many in the Brotherhood to leave Laguna; Griggs fled to the Idyllwild ranch in 1969 (where he would later die), while others fled to Hawaii. Travis Ashbrook, along with Jack Harrington and Gordon Sexton, fled to Maui to escape the heat of law enforcement. For Ashbrook, the move to Maui presented lucrative opportunities to expand the drug business, not necessarily the  opportunity to build the island utopia. Hawaii had transformed into a haven for hippies, surfers, and various vagabonds, all of whom had an insatiable appetite for marijuana. To capitalize on this large market, Ashbrook purchased a seventy-foot yacht, the Aafje, to smuggle hash from Asia and Mexico into Maui. [Image at right] From 1969-1972, Maui was indeed profitable, as many members of the Brotherhood raked in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in illicit drug profits (Maguire and Ritter 2014).

opportunity to build the island utopia. Hawaii had transformed into a haven for hippies, surfers, and various vagabonds, all of whom had an insatiable appetite for marijuana. To capitalize on this large market, Ashbrook purchased a seventy-foot yacht, the Aafje, to smuggle hash from Asia and Mexico into Maui. [Image at right] From 1969-1972, Maui was indeed profitable, as many members of the Brotherhood raked in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in illicit drug profits (Maguire and Ritter 2014).

The growing impact of drug money led to growing distrust among members of the counterculture movement, a distrust that would be amplified by the escalating war on the illicit drug trade. When Richard Nixon was elected president in 1969 he called the problem of illicit drugs “public enemy number one.” Nixon, as well as many members of Congress, believed that the counterculture and its embrace of psychedelic drugs was a significant threat to American society. The government needed a dramatic new policy approach to deal with the problem. The first shoe to drop took place on October 24, 1968; the United States Senate amended the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to ban LSD from use. Although, the LSD Act marked a new approach to the problem of the counterculture and illicit drug use, it was limited in scope. A complete transformation of how the government regulated drugs would be required. This would come in 1970 when Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA). The CSA fundamentally transformed the legal framework for regulating and prohibiting all drugs. Drugs were placed within five schedules, with schedule one drugs deemed the most harmful and therefore entirely prohibited. The law granted the government, and in turn law enforcement agencies, sweeping powers to regulate legal and, in this case, illegal commerce. By the time the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was created in 1973 as the umbrella organization for all drug regulation, the “war on drugs” was fully underway (Frydl 2013). The counterculture, especially the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, would soon be squarely in the crosshairs of the emboldened American government.

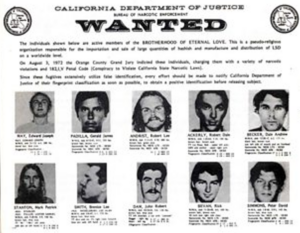

Law enforcement agencies, frustrated by their inability to stop the Brotherhood’s role in the illicit drug trade, created the Brotherhood of Eternal Love Task Force, a collaboration between local, state, and federal law enforcement. After years of playing cat-and-mouse with Brotherhood members, the task force scored a major victory on August 5, 1972 when police raided houses in Hawaii, Oregon, northern California, and Laguna Beach. Fifty-three people were arrested that day, and the police confiscated nearly two and one half tons of hash, thirty gallons of hash oil, and 1,500,000 tablets of Orange Sunshine (Schou 2010). The operation  continued through the following year. Twenty-six members of the Brotherhood, or those affiliated with its smuggling operation, were targeted by police. [Image at right] Possibly the biggest catch, Timothy Leary, was captured in Kabul, Afghanistan, and flown back to Los Angeles. He was charged with escaping prison, along with various other drug charges. The police raid, and the revelations of the depths of the drug trafficking operations, no doubt captured the media’s attention, with Rolling Stone magazine dubbing the group “the Hippie Mafia.” By October 3, 1973, the U.S. government all but celebrated its victory over the Brotherhood. That day, a subcommittee hearing, entitled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” highlighted the extensive drug smuggling operation of the group. DEA supervisor Job Sinclair told Congress:

continued through the following year. Twenty-six members of the Brotherhood, or those affiliated with its smuggling operation, were targeted by police. [Image at right] Possibly the biggest catch, Timothy Leary, was captured in Kabul, Afghanistan, and flown back to Los Angeles. He was charged with escaping prison, along with various other drug charges. The police raid, and the revelations of the depths of the drug trafficking operations, no doubt captured the media’s attention, with Rolling Stone magazine dubbing the group “the Hippie Mafia.” By October 3, 1973, the U.S. government all but celebrated its victory over the Brotherhood. That day, a subcommittee hearing, entitled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” highlighted the extensive drug smuggling operation of the group. DEA supervisor Job Sinclair told Congress:

To date, the Brotherhood investigation has resulted in the arrest of over 100 individuals, including Dr. Timothy Leary who is currently serving 15 years in Folsom Prison. Four LSD laboratories have been seized, along with over 1 million ‘Orange Sunshine’ LSD tablets, and LSD powder in excess of 3,500 grams, capable of producing over 14 million dosage units of the drug…A total of six hashish oil laboratories were seized, along with over 30 gallons of hashish oil and approximately 6,000 pounds of solid hashish” (Schou 2010).

The victory lap was considered the first major victory in the governments “war on drugs.” Yet, for many in the Brotherhood, the victory was pyrrhic. Brotherhood member, Robert Ackerly, who served a brief stint in prison, and was released in the early 1970s, went on to become a major cocaine dealer. In fact, many in the Brotherhood, received relatively light sentences considering the quantities of drugs sold. Some believed that the U.S. government was “thankful” for them, as it gave the government an enemy to justify the passing of the Controlled Substances Act and to create the DEA.

While the government’s war against the Brotherhood certainly marked the end of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, many of the Disciples found its downfall to be more a consequence of the death of Griggs, or the pursuit of fame and money, than of the police. For example, when Griggs died in August 1969, numerous disciples abandoned the cause. To Robert Ackerly, “John was the Brotherhood,” and his death meant the loss of the movement’s prophet (Schou 2010). Moreover, the ambition to create a global utopia, with LSD as a sacrament, was ultimately lost to the allure of wealth, and fame. These enveloped many members of the Brotherhood and its association with various counterculture figures, most notably Timothy Leary. When Griggs opted to buy the Idyllwild ranch, rather than buy an island utopia, many believed that marked a turning point for the group, for the ranch and Leary would become a magnet for publicity and police scrutiny. Indeed, Leary’s public advocacy for psychedelic drug use, as well as his thirst for fame and fortune, garnered him a public notoriety and scrutiny from police that harkened back to the days of Lucky Luciano (Valentine 2004). Fittingly, one of the last members of the Brotherhood to evade police, Brenice Lee Smith, provides the most clarity about the downfall of the group. Smith, who fled to Nepal in 1981, married a Nepalese girl, and became a Buddhist monk. Heremarked four decades later (after serving a brief stint in jail in the U.S. for his role in the Brotherhood) that it was greed and paranoia that led to the Brotherhood’s demise. The Brotherhood of Eternal Love “wanted people to be happy and free and not like what society conditioned you to want to be….we loved everyone and wanted everyone to find love and happiness. We wanted to change the world in five years, but in five years, it changed us. It was an illusion” (Schou 2010). That illusion, just like an acid trip, had to end.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

When Aldous Huxley first used the psychedelic mescaline, he described it as being

shaken out of the ruts of ordinary perception, to be shown for a few timeless hours the outer and the inner world, not as they appear to an animal obsessed with survival or to a human being obsessed with words and notions, but as they are apprehended, directly and unconditionally, by Mind at Large—this is an experience of inestimable value to everyone (Huxley 1954)

What Huxley described in Doors of Perception was an experience in which people were cast off from the ordinary and mundane features of their life, and thrust into a world whereby the individual was part of something greater, if not extraordinary.

For John Griggs, the de facto leader of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the use of LSD was instrumental in his spiritual awakening. Prior to his use of LSD, Griggs lived a life of crime; he used heroin, picked fights, and robbed people at gunpoint. But after a near-death hospitalization for Hepatitis C, and subsequent trip on LSD, he was fundamentally transformed. As friend of Griggs, Chuck Mundell described, “Something happened to John in that hospital…he asked me to come to the hospital and take Christ in my heart with him.” For Griggs, LSD was the living incarnation of God, and it had the power to not only heal an individual but also to heal society. It was through this revelation that Griggs became an evangelist for LSD, believing that it could help create a global utopian society, built on love and happiness, and without war, pain, and trauma (Schou 2010).

When the Brotherhood of Eternal Love was incorporated as a church in 1966, it provided the sense of legitimacy that would help Griggs spread the gospel of LSD. Contrary to his friend and colleague, Timothy Leary, who coined the phrase, “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” at least for Griggs, the various illicit enterprises the Brotherhood engaged in, be it marijuana and hashish trafficking, or LSD manufacture and distribution, were done with the intent to finance and spread the gospel of LSD.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Central to Brotherhood of Eternal Love rituals was the use of LSD. According to Glenn Lynd, who filed the incorporation of the Brotherhood as church, the Brotherhood, and LSD, would help

bring to the world the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Paramahansa Yoganada, Mahatma Gandhi, and all the true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men (Lee and Shlain 1992).

When people arrived the Mystic Arts World, or the Idyllwild ranch, LSD trips were conducted in a way to amplify the spiritual aspects of the LSD journey. Incense was often burned, and houses or teepees were decorated ornately with statues of famous religious figures. The aim was to use LSD with the intent of spiritual growth, to meditate rather than to party.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Although the Brotherhood was non-hierarchical in nature, like many other counterculture groups of the 1960s, they were still centered around their inspirational leader, John Griggs. [Image at right] Griggs’ life was dramatically transformed by the use of LSD; it inspired him to abandon a life of crime to pursue a more spiritual life. Griggs became an evangelist for LSD; he believed it would bring people to closer to God, and that it could ultimately help create a global utopia. Griggs would try to recruit everyone possible to the cause.

Those that would follow Griggs (Eddie Padilla, Robert Ackerly, Chuck Mundell, Dion Wright, Rick Bevan and others) all shared similar stories of transformation to Griggs. Many had lived lives using hard-drugs, committing crime, or lacked general purpose. It was Griggs who showed them the light. It was his zeal for LSD as a conduit for spiritual enlightenment that seemed to convince many others to follow. As more people were drawn to Griggs, and moved to Laguna beach, or the Idyllwild ranch, to participate in the daily or weekly LSD rituals, they began to refer to themselves as the Disciples. The Disciples conversion to the Brotherhood was often compelled by their own revelatory experiences with LSD. Many claimed it healed them of trauma, others of their addiction, and even one claiming it cured a stutter (Schou 2010).

When it came to the Brotherhood’s illicit drug businesses, Griggs was the leader in terms of scheme and purpose; however, they remained relatively non-hierarchical in practice. For example, Griggs was instrumental in putting the sprawling global hash-smuggling operation into motion. However, Griggs was rarely involved in the drug business directly. Rather, it was the Disciples who would be instrumental in conducting the drug business. In fact, for law enforcement part of the challenge of prosecuting the Brotherhood for their illegal drug trafficking operation was that there was no clear leader of the drug business. The lack of clear leader meant that they could never pinpoint precisely the figurehead of the scheme; this partially explains the relatively short sentences served by many of the Brotherhood (Maguire and Ritter 2014).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

By the late 1960s, LSD had emerged as “every mother’s worst nightmare” (Valentine 2004) For conservative Americans, LSD use was indicative of the growing hedonism and declining moral standards of the country. This association with the counterculture movement eventually compelled state and federal authorities to pass laws to criminalize the use of LSD. But it was the Brotherhood’s various other illicit activities that contributed to their demise.

John Griggs grandiose plans, such as buying an island to create an LSD-fueled utopian society, required major financing; the answer lay in marijuana. By the late 1960s, marijuana was ubiquitous with counterculture and social rebellion. As a result, the demand for marijuana exploded (Dufton 2017). From 1966 to 1972, members of the Brotherhood trafficked ever-increasing quantities of marijuana and hashish from Afghanistan and Mexico to feed the insatiable American appetite. The funds from the marijuana and hashish business helped finance the production and distribution of LSD. Over time, as marijuana and hashish flooded southern California, along with copious amounts of LSD, law enforcement took notice. Laguna Beach police officer Neil Purcell, spent years trying to implicate both Griggs and Leary in a conspiracy to traffic illicit drugs, and more often than not, instead busted hippies and surfers. The leader of the nefarious drug trade flooding California’s shores remained elusive (Schou 2010).

On Christmas day, 1970 things would change. The “Christmas Happening” as it was called, was a three-day festival in Laguna Canyon, which was supposed to feature some of the biggest musical acts in the world, such as Bob Dylan and George Harrison. Although, none of the big musical acts showed up, except for Jimi Hendrix drummer Buddy Miles, the festival carried on. During one of the acts, a member of the Brotherhood flew a plane over the crowd, and police, and dropped 25,000 tablets of LSD (Ramm 2017). The audacious act embodied the chaos of the event: food ran out, people had no access to sanitation, and three people even gave birth. Ultimately, the “Christmas Happening” pushed local authorities to the limit. This marked the beginning of a concerted effort on the part of Laguna Beach, California and federal officials to root out the problem that was the Brotherhood. In particular, Purcell and fellow officer Bob Romaine, were able to convince officials of the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (the predecessor to the DEA) that the Brotherhood was more than just innocuous hippies growing vegetables in their commune, but rather the largest drug trafficking organization in the United States. The coordinated effort to bring down the Brotherhood, called Operation BEL, would eventually bring the group to its end in August 1972 following nearly two years of consistent police surveillance (Schou 2010).

Although, the Brotherhood’s role in the growth of the illicit drug trade in California played a major role in its downfall, so too did its affiliation with one of the most infamous figures of the period, Timothy Leary. Leary believed he was the modern messiah, “the wisest man in the 20th Century” (Ramm 2017). Initially, Leary’s presence among the Brotherhood was welcomed. As a college professor, and from an older generation, he legitimized the actions of the Brotherhood by reinforcing the idea that what they were doing (while appearing outlandish to mainstream conservative American society) was indeed the right thing to do (Schou 2010). But Leary was also one of the most visible figures of the counterculture movement, appearing on television shows, testifying in front of Congress, and meeting rockstars. As he became increasingly entrenched in the Laguna scene, with the Brotherhood at his side, their popularity began to corrupt members of the group. While, many Brotherhood members joined the group to live a simple, and pure spiritual life, they soon found that with their newfound fame, and wealth, they became local celebrities. As Travis Ashbrook stated: “if you were part of the Brotherhood? My god, you might as well be Mick Jagger” (Schou 2010). When combined with their outsized role in the illicit drug trade, it is not all too surprising that the fame, fortune, as well as constant infidelity proved to disenchant many members of the group who truly believed in the spiritual mission of the Brotherhood. In essence, over time money proved to be a more powerful force than God, a story that seems all too familiar.

IMAGES

Image #1: Timothy Leary.

Image #2: Mystic Arts World store front @1967.

Image #3: The seventy-foot yacht, the Aafje, used to smuggle hash from Asia and Mexico into Maui.

Image #4: Wanted poster of Brotherhood members and affiliates in the drug smuggling operations.

Image #5: John Griggs with his children.

REFERENCES

Bradford, James. 2019. Poppies, Politics, and Power: Afghanistan and the Global History of Drugs and Diplomacy in the 20th Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brotherhood of Eternal Love1. n.d. “Events.” Accessed from https://belhistory.weebly.com/events.html on 26 January 2024.

Brotherhood of Eternal Love2. n.d. “History.” Accessed from https://belhistory.weebly.com/bel-files.html on 26 January 2024.

Dufton, Emily. 2017. Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America. New York, NY; Basic Books.

Frydl, Kathleen. 2013. The Drug Wars in America 1940-1973. Cambridge, UK; Camrbidge University Press.

Greenfield, Robert. 2006. Timothy Leary: A Biography. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin.

Huxley, Aldous. 1954. The Doors of Perception. London, UK: Harper & Row.

Leary, Timothy. 1970. The Politics of Ecstasy. London, UK: Granada.

Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain. 1992. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. New York, NY: Grove Point.

Maguire, Peter and Mike Ritter. 2014. Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammer, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Ramm, Benjamin. 2017. “The LSD Cult That Transformed America.” BBC, January 12. Accessed from https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20170112-the-lsd-cult-that-terrified-america on 25 January 2024.

Schou, Nicholas. 2010. Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books.

Valentine, Douglas. 2004. The Strength of the Wolf: The Secret History of the America’s War on Drugs. London, UK: Verso.

Wolfe, Thomas. 1968. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. New York, NY: Farrar Straus Giroud.

Publication Date:

30 January 2024