ELIZABETH ANN BAYLEY SETON TIMELINE

1774 (August 28): Elizabeth Ann Bayley was born in Manhattan.

1794 (January 25): Elizabeth Bayley married William Magee Seton.

1795 (May 23): Daughter Anna Maria was born.

1796 (November 25): Son William was born.

1798 (July 20): Son Richard was born.

1800 (June 28): Daughter Catherine was born.

1802 (August 20): Daughter Rebecca was born.

1803 (Fall): Elizabeth and William Seton (her husband) traveled to Italy in search of respite for William’s tuberculosis. There she encountered Antonio and Filippo Filicchi, who encouraged Elizabeth to convert to Catholic Christianity.

1803 (December 27): William M. Seton died of tuberculosis.

1804 (March): The widowed Elizabeth Seton returned to the United States.

1806 (Spring): Seton converted to Catholic Christianity.

1808 (June): Seton arrived in Baltimore to teach at a small Catholic school run by Sulpician Fathers (Society of St. Sulpice Order – Province of the United States).

1809 (July): Seton created the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, a religious order for women founded in the tradition of Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac. The community moved to Emmitsburg, Maryland.

1812: Seton’s daughter Anna Maria died of consumption.

1813 (July): Eighteen women took their first vows as Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, using a rule modeled on that of the French Daughters of Charity.

1814: Sisters from the Emmitsburg Community expanded to Philadelphia to run an orphanage.

1816: Seton’s daughter Rebecca died of consumption.

1817: The Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph created a new outpost in New York City, founding another orphanage.

1821 (January 4): Elizabeth Bayley Seton died of tuberculosis in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

1959 (December 18): Elizabeth Seton was declared venerable by Pope John XXIII.

1963 (March 17): Elizabeth Bayley Seton was beatified by Pope John XXIII.

1975 (September 14): Elizabeth Bayley Seton was canonized as a saint by Pope Paul VI.

BIOGRAPHY

Elizabeth Bayley was born in Manhattan on August 28, 1774. Her father Richard Bayley was an intellectually ambitious physician and her mother Catherine Charlton Bayley was the daughter of an Anglican rector. The American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) soon brought turmoil: Richard Bayley spent the early months of the war in England pursuing additional medical education, then served as a medical officer in the British army during the occupation of New York. Catherine Bayley died not long after giving birth to a baby who also soon died. When Richard quickly remarried, Elizabeth and her older sister Mary gained a stepmother, Charlotte Barclay, who proved to be an awkward mother not only to Elizabeth and Mary, but to the seven children Charlotte eventually bore during her marriage to Richard. Often sent to stay with relatives north of Manhattan, Elizabeth grew up aware of the unhappiness in her home and longing to attract her father’s attention. She never forgot the sorrow and loneliness she sometimes felt.

Although Elizabeth [Image at right] at times attended Episcopal services with her family, institutional Christianity was not important to her childhood. Catholicism (which boasted few adherents in Manhattan and was mistrusted by many Protestants as a superstitious religion whose adherents were loyal primarily to Rome) was largely or entirely unknown to her. Yet Bayley did, by her later account, seek out moments in which she felt close to God; these usually occurred when she was alone in nature. She was also an avid reader, and it was through reading that in her teens she developed a close relationship with her father. She read poetry, ancient history, and contemporary philosophers including Jean Jacques Rousseau and Mary Wollstonecraft, keeping copybooks on her own and in conjunction with her father Richard Bayley.

At age nineteen, Elizabeth Bayley married fellow New Yorker, William Magee Seton, a transatlantic merchant six years her senior. The marriage was happy and the couple lived contentedly in a web of intermarried friends, relatives, and her husband’s merchant associates. Seton also forged female friendships that bolstered her throughout the extraordinary transformations of her life. In the first several years of the marriage, she bore two children: Anna Maria and William. As a young wife and mother, Seton continued to read philosophy, and now also read the Bible and the sermons of Hugh Blair (1718–1800), a Scottish minister and belletrist who eschewed doctrinal controversies in favor of urging Christians toward virtue and benevolence. Seton believed, as she wrote a friend in 1796, that “the first point of Religion is cheerfulness and Harmony” (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol. 1:10)

Her husband’s health began to falter; his mother and aunt had died of tuberculosis and he now showed signs. During the same years, the merchant concern in which William worked for his father faced losses. As she worried for the future, Elizabeth began to find more solace in Christian prayer and reading. Empathetic with women who faced such challenges with fewer resources than she possessed, she also worked with Isabella Graham (1742–1814), an immigrant from Scotland prominent in transatlantic Presbyterian circles, as part of one of the nation’s first female-run groups devoted to charitable works, the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children. Seton served as a manager and treasurer and wrote compassionately of her conversations with women whom the society served (Boylan 2003:96–105).

Threats to Seton’s own privilege grew in 1798, when her father-in-law slipped on ice on his front porch and, after struggling for weeks, died. Elizabeth and William were left to figure out the family’s distribution of money and effects (the elder Seton died intestate), to manage the merchant house’s complex business dealings, and to provide for William’s seven half-siblings still living at home. The young couple, Elizabeth still in her twenties, and the children took up residence at the elder Seton’s home, which also housed the merchant business. Seton found her new circumstances profoundly disorienting, regretting that she had little time left for reading, prayer, and thought. The next two years saw the Seton merchant house struggle while Elizabeth, who bore two more children, Richard and Catherine, during this period, worked informally as her husband’s clerk. In December 1800, William Seton declared bankruptcy.

While William [Image at right] struggled to rebuild his credit, Elizabeth found a spiritual guide in a young assistant rector of Trinity Church named John Henry Hobart (1775–1813), who gave emotionally rich sermons redolent with confidence that Episcopal priests were the descendants of Christ’s apostles. During this same period, Elizabeth’s father, with whom she had maintained a close intellectual relationship since her teenage years, died of typhus while tending patients at a quarantine station. Deprived of her father and concerned for her consumptive husband, Seton felt impatient with earthly life. “I will tell you the plain truth,” she wrote to a friend, “that my habits both of Soul and Body are changed—that I feel all the habits of society and connections of this life have taken a new form and are only interesting or endearing as they point the view to the next” (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol 1:212).

In 1802, Seton gave birth to a fifth child, Rebecca. That year Elizabeth and William also concocted a desperate plan: a voyage to Italy, in hopes that the climate might restore William’s health and an Italian merchant clan with whom Seton had lived and worked before his marriage, the Filicchi family, might help restore his business. In fall of 1803, the couple left their four younger children with friends and relatives and embarked for Livorno with their oldest daughter Anna Maria. On arrival in Livorno, the family was promptly put into quarantine for a month, because officials feared the tubercular William posed a risk. William died soon after their release, hallucinating that he had won the lottery and left his family with no debt.

For the next four months, Elizabeth and Anna Maria lived with the Filicchi family. As Seton mourned her husband, her hosts coaxed her to convert to Catholicism. The Filicchis had for years seen the United States as a potential refuge for a Catholic faith they believed was profoundly threatened in Napoleonic Europe, and Seton’s arrival in their home seemed providential. Brothers Antonio and Filippo Filicchi took Seton to Catholic Masses, shared Catholic readings, and introduced her to the cultural glories of Florence. At first, Seton gently laughed off their efforts, but she soon found herself moved by Mass, by the prominence of the Virgin Mary in Catholic devotion, and by the doctrine of transubstantiation, which is the Catholic teaching that Christ is present in the sacrament of communion. As she prepared to return to New York, Seton decided to convert.

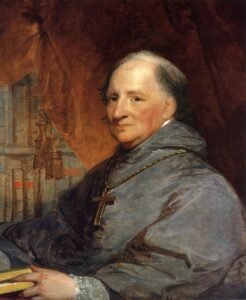

Seton told her startled family and friends of her intentions soon after she disembarked in early June 1804. Most hoped that she would settle back into her old life and abandon a conversion they considered motivated by grief and disorientation. One person took her decision seriously and was appalled: John Henry Hobart of Trinity Church. In personal conversations and in a long  argument he wrote out by hand, Hobart launched a withering assault on Catholicism as superstitious and barbaric. Seton began to compare the competing faiths’ claims by the light of her own judgment. Months of agonized indecision followed as she read Protestant and Catholic apologetics and sought guidance from Catholic priests in New York, and, via correspondence, in Boston. She hoped for guidance from the nation’s lone Catholic bishop, John Carroll (1735–1815), [Image at right] but he wrote only cautiously and impersonally, having no wish to involve himself in a Protestant matron’s public struggle over faith (O’Donnell 2018:177–99).

argument he wrote out by hand, Hobart launched a withering assault on Catholicism as superstitious and barbaric. Seton began to compare the competing faiths’ claims by the light of her own judgment. Months of agonized indecision followed as she read Protestant and Catholic apologetics and sought guidance from Catholic priests in New York, and, via correspondence, in Boston. She hoped for guidance from the nation’s lone Catholic bishop, John Carroll (1735–1815), [Image at right] but he wrote only cautiously and impersonally, having no wish to involve himself in a Protestant matron’s public struggle over faith (O’Donnell 2018:177–99).

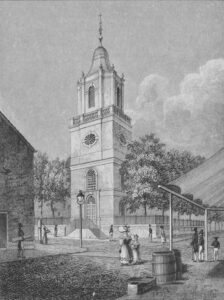

Finally, Seton made her choice. She was drawn to the Catholic understanding of communion, to the culture of the saints and Catholic religious art, and to the figure of the Virgin Mary. But she also decided that Catholicism was simply the safest bet. “If [choice of] Faith is so important to our Salvation I will seek it where true Faith first began, seek it among those who received it from GOD HIMSELF,” Seton wrote. “As the strictest Protestant allows Salvation to a good catholick, to  the Catholicks I will go, and try to be a good one, may God accept my intention and pity me” (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol 1:374, original capitalization and spelling). Seton attended her first Mass in the United States at Manhattan’s only Catholic church, St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church. [Image at right] Shortly afterward she made her profession of faith as a Roman Catholic and received Catholic communion.

the Catholicks I will go, and try to be a good one, may God accept my intention and pity me” (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol 1:374, original capitalization and spelling). Seton attended her first Mass in the United States at Manhattan’s only Catholic church, St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church. [Image at right] Shortly afterward she made her profession of faith as a Roman Catholic and received Catholic communion.

Seton’s friends and family in the main considered Catholicism to be an unsuitable religion, its teachings ill-configured to modern life, and its adherents of lower status and education than the Seton and Bayley families. Yet most accepted her choice, and some were relieved that her agonized indecision had ended. Her family continued to support her financially after her conversion. It was Seton’s own intense desire to proselytize young female members of her extended family, as well as her determination to live as fully Catholic a life as possible, that strained relations and left her eager to leave Manhattan. At first she sought to bring her children to Montreal, but she was soon invited by William Dubourg (1766–1833), an enterprising Sulpician priest, to run a small school in Baltimore. There, Dubourg explained, her boys could attend the school run by Sulpicians, called Mount St. Mary’s, while she taught the daughters of Baltimore’s wealthy Catholic families, along with her own three daughters, at a girl’s academy. Seton wrote happily that clergy believed that she was “destined to forward the progress of his holy Faith” in the United States (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol. 1:432).

Arriving with her girls in Baltimore, Seton was grateful to live within the sound of Catholic church bells and to have the guidance of the Sulpicians. Yet she was soon discontented: The fully devotional life she had dreamed of in New York eluded her. So she was pleased that Sulpicians in Baltimore imagined a different role for her: leader of a community of women religious (in the parlance of the Church, women who had taken vows of obedience, poverty, and celibacy).

The Council of Trent (1545–1563) had sought to impose strict cloister on all women religious, but in France, two communities (the Ursulines and the Daughters of Charity) developed rules and practices that enabled members to work on behalf of laypeople while living vowed lives. Ursulines taught schoolgirls and Daughters of Charity served people who were impoverished, orphaned, or ill. Baltimore’s Sulpician priests believed that Seton could start a community that might combine teaching and benevolent work.

Sulpicians recruited young women who might wish to join the community. Seton wrote to the Filicchi brothers to request financial support. John Carroll, though unsure how Seton would lead a religious community before having belonged to one, warmed to the idea that she could found an active religious community that would offer a spiritual path for Catholic women and education to Catholic children. Such a community would be an American entrant in the Vincentian tradition, so called because Vincent de Paul (1581–1660) was, along with Louise de Marillac (1591–1660), a founder of the Daughters of Charity. A plan emerged for a Seton-led community to be founded near a new Sulpician boys’ school in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Maryland. She happily wrote Filippo Filicci of an “institution for the advancement of catholick female children in habits of religion and giving them an education suited to that purpose” (Bechtle and Metz 2002, vol 2:47).

In 1809, Seton left Baltimore to begin (another) new life. Her sons entered the Sulpician school, Mount St. Mary’s, while her daughters joined her at the fledgling women’s community and girls’ school, named St. Joseph’s Academy and Free School, in Emmitsburg, Maryland, located in the adjoining valley. A few women from New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore entered the community as did two of Elizabeth’s sisters-in-law. The women were given a preliminary rule of conduct based on de Marillac’s Daughters of Charity. They created a boarding school for paying students and a day school with a less ambitious curriculum for locals who would pay free or reduced tuition in style closer to the Ursuline model noted above. Seton acquired the title she would hold for the rest of her life: “Mother.” In addition to a female and a male superior, there was to be an elected council of sisters, a structure that reflected Catholic tradition.

The community faced hardships in its first year. Illness, including tuberculosis, circulated, and their first dwelling was unfinished and drafty. Seton soon mourned the death of both sisters-in-law. She had difficulty substituting the judgment of male superiors for her own in matters such as the women’s choice of confessor. Such struggles over obedience and a spiritual dryness that left her unable to feel God’s presence left Seton feeling as if she were playacting the role of mother and believing that she might be (and might deserve to be) replaced as Mother.

Although Seton’s personal writings make clear her distress, surrounding documentation reveals a thriving community and a respected leader. The Sisters’ school thrived (McNeil 2006:300–06). Seton was involved in every aspect of the enterprise, from paying bills to designing curricula to disciplining the girls. She also served as female spiritual director to the community’s members and began the work of writing reflections, translating religious works from French, and offering personal counsel that would continue for the rest of her life.

As the community grew, a Sulpician priest translated from French the Rule of the Daughters of Charity, making only small changes. Like the French Daughters, the Emmitsburg Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph were to serve the poor rather than living in cloister, and, like the Daughters of Charity, they would take private annual vows. The women discussed the proposed regulations and voted on them in 1811, a practice which, like the Sisters’ elected leadership council, was part of Catholic tradition. One woman voted no and soon left the community, but everyone else voted yes and remained. All of the women, including Seton, became novices in the community and expected to take their vows as Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph in a year.

As the community began its formal existence as the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, Anna Maria, Seton’s oldest child, died of consumption. Seton’s spiritual struggle after Anna Maria’s death led the Sulpicians to send to Emmitsburg a highly educated priest named Simon Bruté (1779–1839), whom they felt would serve as an effective spiritual director. It was a good choice. Bruté shared with Seton a Catholicism that fully engaged her mind and the two read and discussed centuries of Catholic writing. Their letters make clear that this was a collaborative spiritual relationship. When he needed to instruct his English-speaking flock, the French priest turned to Seton for help. Bruté’s services attracted a growing number of Catholics to take Communion at a time when clergy in the area felt the competition of Protestant revivalists.

In July 1813, four years after Seton had first arrived at Emmitsburg and one year after adopting their regulations, eighteen women took their first annual vows as Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph. They were a mix of widows and women who had never married, and of American-born, Irish and (via the West Indies) French. Soon, the sisterhood began to expand beyond Emmitsburg. In 1814, women who ran Philadelphia’s Catholic orphan asylum requested Sisters be sent from Emmitsburg to run the orphanage and care for the children, and the Sisters’ leadership council quickly agreed. In 1817, the sisterhood created a new outpost, this one an orphanage in New York City. As the Sisters branched out, their original schools at Emmitsburg also thrived. Focused on boarding students but providing educations to local girls at reduced cost, the institutions were important to the region and to a larger web of well-heeled Catholic and Protestant families.

Seton faced new tragedy when her youngest daughter, Rebecca, died of consumption. She also worried for her sons, who were ill-suited to the merchant life she wanted for them. Yet she increasingly felt herself the serene Mother she had long appeared to others and confidently tended to the practical and spiritual needs of Sisters and students. Once uninterested in institutional Christianity, Seton was now an institution builder. There was another change, as well. The woman who shortly after her conversion had insisted on proselytizing, had decided that it was impossible to persuade others what to believe, and perhaps harmful to try. She declined to proselytize Protestant girls in her care and counseled others to let people find their own way. Her new way of thinking melded a belief that spiritual safety lay within the teachings of the Catholic Church, with one more familiar to Protestants: each individual must forge her own relation with God.

Seton developed and shared her thinking in hundreds of pages of reflections, translations from French, and meditations, as well as in the words of Bruté’s sermons. Her contemplative nature had caused her to struggle over the demands of leading an active community, and her desire to lead a heroic life for God sometimes led her to chafe at the essentially domestic nature of her service, and occasionally at the gendered structures of the Catholic Church. But she turned to Vincentian teachings to discern meaning in her labor and role as a Sister and wrote convincingly of her contentment.

In 1818, after living with people suffering from tuberculosis for her entire adult life, Seton finally began to suffer from it. She endured her long illness in the tender care of the other Sisters. By late 1820, she openly looked forward to death, no longer bound by her responsibilities to her children (though Catherine was heartbroken) or the sisterhood, both of whom she considered well launched. Elizabeth Seton died on January 4, 1821, in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

The Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph grew in the decades after Seton’s death, with communities founded throughout the United States. In 1850, male clergy arranged for the various Sisters of Charity communities to affiliate formally with the French Daughters of Charity. Many did, but some (including the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati and the Sisters of Charity of New York) declined to do so, for reasons emerging from their thoughts about governance and consultation, rather than differences in doctrine or charism. (In a Roman Catholic religious community, the charism is the heart and soul of its purpose, history, tradition, and rule of life.) As a result, some communities that trace their lineage to Emmitsburg are known as Daughters of Charity, and others as Sisters of Charity. As the nineteenth century progressed, Sisters and Daughters of Charity were joined by many other female religious communities in the United States: by 1900, there were nearly 150 Catholic female religious orders and congregations and approximately 50,000 nuns and Sisters (Mannard 2017:2, 8).

Throughout the nineteenth century, admirers kept Seton’s memory alive. While Seton still lived, Simon Bruté successfully dissuaded her from burning her papers; she worried that her life of inquiry, struggle, and choice might teach inappropriate lessons, but Bruté was confident that it would lead others to what he considered the safety of the Church. Sisters of Charity as well as friends and family also preserved and sometimes made copies of Seton’s letters. This formed the basis of an archive that resides now at the National Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton in Emmitsburg. Sisters of Charity have also edited and annotated a four-volume collection of Seton’s writings, and have overseen the Seton Writing Project, which provides an online annotated catalog of letters written to and about Seton. (Bechtle and Metz 2000–2006; Seton Writing Project). In 1882, James Cardinal Gibbons (1834–1921) proposed to the community at Emmitsburg that an effort to bring about Mother Seton’s canonization—a cause, in the language of the Church—be begun. Gibbons’ proposal was part of a broader effort to convince Rome to canonize an American citizen, and Seton was not in fact the first: Mother Frances Cabrini (1850–1917), an Italian who arrived in New York City during a transformational period of immigration, was canonized in 1946.

The cause of Elizabeth Seton, however, persisted. In 1907, an ecclesiastical court was created to investigate its merits. In 1931, American women traveled to the Vatican and petitioned Pope Pius XI (p. 1922–1939) on behalf of Elizabeth Seton’s canonization. In the same year, the American Catholic hierarchy voted to approve her cause. The Mother Seton Guild formed to advocate for her canonization, and in the 1940s, Sisters and Daughters of Charity authorized a formal biography. American Catholic women organized petition drives, requesting that the pope look kindly on the question of her sainthood. In 1959, the Congregation of Rites declared that Mother Seton should be honored as “venerable.” In 1963, Pope John XXII beatified her, meaning that Catholics should consider her to be with God in heaven and may refer to her as Blessed. Finally, in 1974, Pope Paul VI announced that three miracles had been accepted by the Church and that number, rather than the traditional four, would be sufficient. Elizabeth Bayley Seton was canonized the next year as the first American-born saint, with a crowd of over 150,000 in attendance at St. Peter’s Square (Cummings 2019: 195–98).

TEACHINGS

Elizabeth Seton [Image at right] did not develop new religious teachings; instead, she adapted traditions of Catholic worship and Vincentian religious community to her sensibility and American circumstances, and she drew others in with her charismatic example. Seton and her religious community made visible female Catholic benevolence at a time when Catholicism was a mistrusted religion in the United States. Their work in schools and orphanages also laid practical groundwork for urban Catholicism before the waves of immigration of the 1840s.

Seton catechized Catholic girls attending the school she and the Sisters ran. She also catechized enslaved people who labored for the Sulpicians’ St. Mary’s school. We do not know whether enslaved people attended and sent their children to catechism through choice, coercion, or a mixture of the two.

Seton shared Catholic teachings outside of classrooms and catechetical sessions, as well. While still in New York, before embarking on life as Mother Seton, she introduced young female relatives to elements of Catholicism, likely foregrounding the doctrine of transubstantiation, prayers such as the Memorare to the Virgin Mary, and the intervention of saints. Once established in Emmitsburg, she had institutional authority for the first time in her life. As Mother Seton, she counseled sisters and offered talks for the community; she also translated texts from French, including a life of Louise de Marillac and works of Saint Teresa of Avila (1515–1582) and Saint Francis de Sales (1567–1622), as well as a Treatise on Interior Peace by the French Capuchin priest Ambroise de Lombez (1708–1778). The structure of the Catholic Church did not allow for female preaching: priests, not Sisters, were to give sermons. But Simon Brute’s poor English and deep respect for his friend left Seton first translating and then apparently largely writing Brute’s sermons for his English-speaking congregants.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Elizabeth Bayley Seton was drawn to Catholicism in great measure because of its rituals and material culture. In this she departed from her contemporary, the bishop and archbishop John Carroll. Influenced by an English Catholic tradition, Carroll favored a restrained Catholicism that blended in with Protestant neighbors; when he had the opportunity to design a cathedral, it was in the American Federal style (O’Donnell 2018:225). By contrast, during her long struggle over conversion, Seton came to believe that Catholicism was more compatible with the human mind and heart than Protestantism in great measure because of its rituals and material culture. The Protestants’ God, she wrote, seems not “to love us . . . as much as he did the children of the old law since he leaves our churches with nothing but naked walls and our altars unadorned with either the Ark which his presence filled, or any of the precious pledges of his care of us which he gave to those of old.” Catholicism offered “something to fix [my] attention” (Bechtle and Metz 2000, vol. 1:369–70). The religious community she created treasured the paintings, crucifixes, and rosaries it could acquire. The Sisters’ black garb was based on the Italian widows’ weeds Seton had adopted after her husband’s death. Plain by the standard of many European communities, it nonetheless distinguished the Sisters from other women, and Seton established it at the inception of the community. As Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph spread out from Emmitsburg to form additional communities, they often brought with them something of Seton’s (a letter, for example) and that remained a treasured possession in the new sisterhood.

ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Mother Ann Seton was the first American woman to found a Catholic order for women in the United States. In doing so she both worked within the structures the Catholic Church provided and used relationships with clergy and laity to extend her authority, the latter a kind of activity that is itself a tradition within the Church. Her approach to creating a religious community is illustrative. Seton let her interest in living in a religious community be known to priests, understanding that it was they who had the ability to connect her to an existing community or to create a new one. When Sulpician priests began to plan for a community in the tradition of the Daughters of Charity, Seton helped to raise funds and began quietly to encourage women to join it, but she did so deferentially, always presenting herself as responsive to providence and to clerical guidance, rather than letting on that she was driven by her own ideas and spiritual ambitions. Knowing she was likely to be chosen as the community’s leader, she did not put herself forward but demonstrated her willingness to take on the role.

Seton’s leadership [Image at right] of the community once it[ was created occurred within the structure and ethos set by the community’s regulations, which were modeled on the Rule of the Daughters of Charity, itself a descendant of the Rule of Saint Benedict. This template for community life drew on centuries of experience creating a framework in which individuals living in close proximity pursued difficult spiritual and communal goals in as much harmony as possible. Days and seasons were organized around both liturgical rhythms and mundane tasks, and a clear hierarchy coexisted with significant collective decision-making. Useful as this framework was, Seton nonetheless also led through developing personal relationships with those around her, including deep friendships that departed from the monastic tradition. Seton knew of St. Teresa of Avila’s instruction that the Sisters should love each other equally rather than forming specific friendships; she nonetheless chose to create a different kind of community, one that understood earthly affections as productive of rather than competitive with worship of God.

Seton’s authority emerged from her spiritual counsel and charisma. This was so because the women of the community, as well as the priests formally and informally affiliated with it, understood her to be in communion with God, and possessed of unusual spiritual power. Seton herself also grounded her ethics in her spirituality. She believed that contemplation of Christ’s sufferings produced a deep consciousness of shared human frailty and of God’s love. This awareness inspired not only worship of God but also compassion and practical benevolence toward others. “I am not enabled as Jesus Christ to do miracles for other,” Seton explained, “but I may constantly find occasions of rendering them good offices and exercising kindness and good will towards them” (Bechtle and Metz 2006, vol. 3a:195). This understanding of active love, concordant with the Vincentian tradition, was central to Seton’s leadership.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Elizabeth Seton faced challenges because of her gender and her choice to convert to Catholicism. As a woman, she had difficulty earning money after the death of her husband, and her financial dependence on her family accentuated the tensions caused by her conversion. Those tensions reflected an Anglo-American mistrust of Catholicism as a religion that repressed patriotism and individual judgment. Although most of her friends and family accepted her decision, Catholic faith still differentiated Seton from the predominantly Protestant culture in which she lived; her intense devotion to her adopted faith, as much as the unexpected content of that faith, temporarily strained ties. The small number of Catholics and paucity of Catholic communities in the United States posed a challenge when Seton decided to become a woman religious, but her country also offered a realm for innovation: she founded the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph because the United States had no community for Catholic women religious that she could join. That community initially faced challenging living conditions, with unfinished buildings and tight finances. It is important to recall, however, that she always had benefactors and that the school and community benefited from funds produced by the institution of slavery. This was true because the Sulpicians at Mount St. Mary’s used enslaved labor, because the American Catholic Church as a whole, which helped to support the Sisters, benefited from enslaved labor, and because families paid tuition to the Sisters using money derived from enslaved labor (O’Donnell 2018:220–21).

Seton’s struggles with obedience would have been recognizable to male members of religious or monastic communities, but also had an additional gendered dimension: she chafed at the need to obey male superiors whose judgment she at times doubted, and she felt occasional frustration that her sex meant she could not be a missionary or a priest. Seton always, however, found her way to contentment with the teachings of her adopted faith, and the challenge of obedience seems to have fallen away in the last years of her life.

During her life, Seton faced challenges familiar to many women religious, including some who would become saints: times of spiritual dryness or a feeling of distance from God, challenges of obedience, and a painful sense of sinfulness. After her death, her progress toward canonization also faced familiar challenges. Canonization requires a sustained lobbying effort as well as extraordinary qualities in the proposed saint, and Seton’s followers lacked both familiarity with the Vatican’s processes and unity as those seeking her canonization disagreed over tactics (Cummings 2019).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Elizabeth Bayley Seton is a convert, a Catholic saint, the founder of a religious community, and a leader within the Vincentian tradition. She also developed distinctive ideas about how to reconcile religious faith and a desire for social harmony in a pluralist society. Because of an extensive archive, [Image at right] Seton’s thoughts, emotions, and spiritual life are unusually accessible. We can read in her own words about the spiritual, social, and domestic contexts of her conversion decision. Her writings provide insight into the distinctive challenges of adopting a faith different from one’s family posed to a woman living in a society in which her own employment possibilities, and thus her capacity to support herself and her children should her family reject her, were constrained. At the same time, Seton’s archive allows us to see specific elements of Catholicism’s appeal to her as a woman: the centrality of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the esteem for female saints, and the possibility of life as a vowed woman religious. Catholicism offered her institutional support for her spiritual ambition in a way that the Episcopal Church, as she knew it, did not.

Sainthood also has offered Seton posthumous influence. Her example, like that of other female saints, was preserved and promulgated in a way unusual for women. (She is also included in the Anglican calendar of saints.) Women, both within the Sisters and Daughters of Charity communities descended from Emmitsburg and outside of it, lobbied for her canonization and continue to cherish her memory. Sisters and Daughters of Charity will also point out that Seton was canonized during the United Nations’ International Women’s Year (1975), and that Sister Hildegarde Marie Mahoney, a Sister of Charity of Saint Elizabeth, served as lector during the canonization Mass, the first time a woman had an official role in a papal liturgy.

Seton’s legacy is in fact most evident in the many religious communities that can be traced to the Sisters of Charity of Saint Joseph. In the Vincentian model, highly competent women, freed of the responsibilities to husbands and children that interrupted the benevolent labors of most Protestant peers, carried out the charitable work of the Catholic Church. For more than a century after Seton’s death, Sisters and Daughters of Charity grew in number and expanded their geographical reach. By the 1850s, there were communities in Ohio, Louisiana, Virginia, Alabama, Indiana, Massachusetts, and California, in addition to the Emmitsburg, Philadelphia, and New York communities founded during Seton’s life. Members of the community tended soldiers during American wars, founded hospitals and orphanages, and eventually established communities in Asia, as well. Their service work during the American Civil War (1860–1865) helped create a favorable impression of Catholicism, especially at a time of anti-Catholic sentiment.

In recent decades, the numbers of Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph have shrunk, in accord with a general and precipitous decline in religious vocations in the Catholic Church in the United States. Nonetheless, as of 2023 there were still approximately four thousand members of the Sisters of Charity Federation, which unites the North American communities with ties to Mother Seton’s original Sisters of Charity of St Joseph and, along with lay members, continues to work on behalf of refugees, migrants, and people experiencing homelessness and poverty. Hospitals throughout the United States, including several medical centers in the Austin, Texas, area, still bear the Seton name and trace their roots to clinics and infirmaries founded by Sisters of Charity, though they may have long since ceased to be staffed by members of the religious communities. Similarly, schools named for Elizabeth Seton persist throughout the United States, many of which no longer have or never had direct connections to Sisters of Charity, but nonetheless see in Mother Elizabeth Seton a useful inspiration. The National Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton preserves buildings associated with Seton’s time in Emmitsburg as well as many artifacts. Its programs include education, spiritual, and charitable works. Thus, the legacy of Mother Seton lives on in countless ways.

IMAGES

Image #1: This portrait of Elizabeth Ann Seton is a reproduction of a portrait painted by Amabilia Filicchi. The reproduction was sent to the Daughters of Charity by Patrizio Filicchi in 1888. It is based on an engraving by Ceroni from the 1860s, which in turn was based on a 1797 engraving by Charles Balthazar Julien Fevret de Saint-Mémin. Wikimedia.

Image #2: Portrait of William Magee Seton created in 1797 by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin. National Portrait Gallery.

Image #3: Portrait of Archbishop John Carroll, created by Gilbert Stuart. Georgetown University Library.

Image #4: An image of Old Saint Peter’s Church, where Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton took her first communion. Wikimedia.

Image #5: Bronze statue of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton located at Seton Hall University, which was named after her. Bishop James Roosevelt Bayley, her nephew, founded Seton Hall College.

Image #6: Statue of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton at St. Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx, New York.

Image #7: The minor basilica and shine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton, Emmitsburg, Maryland. Wikimedia, photo by Acroterion.

REFERENCES

Bechtle, Regina, S.C., and Judith Metz, S.C. 2000–2006. Elizabeth Bayley Seton: Collected Writings. Four Volumes. Hyde Park, NY: New City Press.

Bechtle, Regina S.C., Vivien Linkhauer, S.C. Betty Ann McNeil, D.C. and Judith Metz, S.C. n.d. Seton Writings Project. Digital Commons @ DePaul. Accessed from https://via.library.depaul.edu/seton_stud/ on 10 September 2023.

Boylan, Anne M. 2003. The Origins of Women’s Activism: New York and Boston, 1797–1840. Greensboro, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Cummings, Kathleen. 2019. A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Mannard, Joseph G. 2017. “Our Dear Houses Are Here, There + Every Where”: The Convent Revolution in Antebellum America.” American Catholic Studies 128:1–27.

McNeil, Betty Ann. 2006. “Historical Perspectives on Elizabeth Seton and Education: School is My Chief Business.” Journal of Catholic Education 9:284–306

O’Donnell, Catherine. 2018. Elizabeth Seton: American Saint. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

The National Shrine of Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton. 2023. Accessed from https://setonshrine.org/ on 10 September 2023.

Publication Date:

14 September 2023