Ananda Marga Yoga Society

Ananda Marga Yoga Society

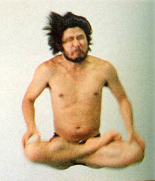

Founder : He is known to his followers as Marga Guru Shrii Shrii Anandamurti (which means “He who attracts others as the embodiment of bliss”), but is also known as Prabhat Rainjan Sarkar (his birth name), or Ba’Ba (which means father). 1

Date of Birth : May 21, 1921-October 21, 1990. 2

Birth Place : The small town of Jamalpur in Bihar, India. 3

Year Founded : 1955 in Jamalpur, Bihar, India. 4

Sacred or Revered Texts : Although there aren’t any sacred texts in Ananda Marga, there are works by the founder of Ananda Marga and other writers that are used as a philosophical skeleton to help guide the members. The founder used the name Shrii Shrii Anandamurti when he wrote books on spiritual topics and the name Shrii Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar when he authored books on other areas. The first book was Ananda Marga- Elementary Philosophy that was written by Shrii Shrii Anandamurti, and outlines the philosophy of Ananda Marga. Besides this book, there are many more books that outline the philosophy of Ananda Marga and other important doctrines written by Anandamurti and others. These books can be found on the Ananda Marga Homepage. 5

Size of Group : The largest concentrations of Ananda Marga are located in India and in the Phillipines, but members are found throughout the world and can be found in most countries. “Though it has been suggested that this ‘revolutionist’ movement has several million adherents, the actual membership is undoubtedly very much smaller” 6 . Worldwide, there are spiritual and social activity centers in over 160 countries. 7

History

Prabhat Rainjan Sarkar was born on May 21, 1921 on Vaesha’Khii Pu’rn’ima’, or Buddha Pu’rn’ima’ (the day of the full moon of the lunar month). He was the fourth child in a family of eight. 8

He was a bright student who eventually went to Vidyasagar College in Calcutta, and it was here that his spiritual powers manifested. The story of his first disciple is said to have taken place when he was a freshman in college in 1939. One night Sarkar took his usual walk along the banks of the Ganges and sat down to rest and there went into a state of meditation. A man by the name of Kalicharan came up to him and tried to rob him. Sarkar acted very calmly and began to talk to Kalicharan and finally asked him if he was interested in changing his life. As Sarkar continued to talk, Kalicharan became captivated and ended up bathing in the river and becoming the first sadhaka (spiritual aspirant) initiated to the spiritual path by Sarkar. Kalicharan then changed his name to Kalikananda. This event occurred on a full moon in August, Shra’van’ii Pu’rn’ima’, and every year this date is celebrated. 9

In 1941 Sarkar passed the intermediate science exam and went to work on the railway where his father had worked. During this time before the establishment of the Ananda Marga Yoga Society, Sarkar built up a following. He was evidently able to look over his followers with his “omniscient power” and the ability to see whether they correctly observed yama and hiyama (the ten cardinal principles of morality). 10

In 1954 Sarkar told his senior sadhakas that he would be establishing a new organization and preparations went under way for the inauguration (by-laws and articles of association were drawn up), which would take place on January 1, 1955. On this date, Sarkar and his followers met at house 339 at the Rampur Rail Colony where he was instated as the organization’s founder-president. The organization took the name of Ananda Marga Pracaraka Samgha, “The Society for the Propagation of Ananda Marga Ideology,” which would be better known as the Ananda Marga Yoga Society. 11

The name “Ananda Marga” came from a relationship with saint Brghu. Saint Brghu had attained Brahma (infinite consciousness) after a long period of penance. From this infinite bliss, the universe and its entities were created. In this bliss (Ananda) everything flourishes and in the end everything also returns to Ananda and merges with it. Because of this, Ananda is the same as Brahma. 12

After the founding of Ananda Marga, Sarkar started to train missionaries to spread his teaching of “self-realization and service to humanity” (which became the motto of Ananda Marga) into India and the rest of the world, and in 1962 initiated the first monk (called Dada, meaning elder brother) of Ananda Marga. He followed this with the creation of an order of nuns (called Didis, meaning elder sister) in 1966. 13 In 1963, Sarkar established the Education Relief and Welfare Section (ERAWS) of Ananda Marga. ERAWS has created schools, colleges, homes for children, hospitals all over the world. 14 Sarkar also created the theory of PROUT (Progressive Utilization Theory) in 1959 which is a theory of how to end social and economic injustice in society and the world. 15

In December 1971 Sarkar was arrested and charged with murder which was later reduced to the charge of “abetment to murder” and had no trial for four years. When he finally had a trial he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. After Indira Gandhi fell from power in 1978 he was granted a new trial and found innocent. Sarkar and Ananda Marga have sparked much controversy due to its political activism. In the early and mid- 1970s, the Indian government considered the organization a terrorist organization that taught its members ritual murder. He continued to work to expand his philosophy and also Ananda Marga to the rest of the world until his death in 1990. 16

Because Sakar’s philosophy of “service to humanity” covers such a broad base of ideas, his organization is made up of numerous branches dedicated to different aspects that Ananda Marga focuses on, such as environmental awareness and disaster relief. Under environmental awareness, he used the term “Neo-Humanism” to define his belief that one should extend humanism to love for animals and plants as well as people. 17 With this belief, he established a global plant exchange program to save plant species around the world and also established animal sanctuaries around the world. Under disaster relief, Ananda Marga has created two organizations to help with disaster relief efforts. AMURT (Ananda Marga Universal Relief Team) and AMURTEL (Ananda Marga Universal Relief Team Ladies) were created in 1965 and 1977 respectively.

AMURT was first founded to help victims of the numerous floods in India but has eventually expanded globally to 80 countries. Each sector is independent (choice of projects and obtaining funds) but can obtain technical help from other sectors. In each country that AMURT exists, it not only helps with disaster relief but also works with helping to develop the country. They follow the method called “co-operative development” which is when workers of AMURT work with the people to help improve their situation through construction, agriculture, and water preservation. It also participates in social programs such as owning and running schools, renovating schools, training teachers, running children’s homes, and providing medical aid. 18

AMURTEL is the sister organization of AMURT and is geared toward the specific needs of women and their families and is also run by women. AMURTEL provides medical care for pregnant and nursing mothers, helps educate women in home industry such as tailoring, handicraft, and commercial food production, and also promotes effective birth control. AMURTEL also sets up relief and refugee camps, distributes food, medicine and clothing, provides cheap kitchens and nutrition classes, and aids underprivileged children by running low tuition schools. It also sponsors homes and halfway houses for children, the elderly, the handicapped, battered women, and also run cheap hostels for underprivileged students. 19

Today, Ananda Marga is a worldwide organization with centers in over 160 countries, including the United States. 20

Beliefs

The ideology of the group is universal and it stresses the unity of human society. Criticizing religions and other spiritual paths is strongly discouraged and the group has a strong commitment to bring progress to the whole of human society (and other creatures) by doing service to the suffering in all kinds of ways. To this effect, Sakar created organizations such as AMURT, AMURTEL, and the philosophy of PROUT to carry out the activities to achieve this progress.

His philosophy of PROUT called for economic democracy, which is maintaining human rights, and giving control of the economy to the local level rather than “a handful of leaders [who] misappropriate the political and economic power of the state.” He also called for the election of competent, educated, and moral people into public office rather than candidates who rely on money to win an election, a balanced economy by controlling industry on the local level, redistributing cultivatable land, and putting money into productive ventures such as railroads. Sakar said that science and technology should be guided by Neo- humanistic principles. He wanted the establishment of a welfare system and fair taxation, social and economic justice, women’s rights, and the creation of a world government with a global bill of rights, global constitution, and global justice system. 21

The group’s dislike of narrow-mindedness is very apparent in the philosophy of Neo- Humanism, which is the belief that one should extend humanism to love for animals and plants as well as people. This philosophy of Neo-Humanism is carried over into education through Ananda Marga schools, which are located throughout the world, including the United States. 22

Ananda Marga practices Tantra Yoga, and since it is considered a practical science (intuitional science of the mind). Yoga is an important practice in following Ananda Marga. Tantra yoga was founded by Lord Sadashiva who was also the interpretor of the Tantra which is a mystical tradition of Eastern India. Tantra means “liberation through expansion” and so the practice of Tantra yoga is to free one’s mind. Tantra yoga the universe is a part of Brahma which is the Supreme Conscious Being. It is said that Brahma is split up into two parts, the Eternal Consciousness (Shiva) and creative power (Shakti). All living things apparently identify with material and mental goods made by Shakti and are not fully connected with Shiva. When one becomes human they can increase their identification with Shiva, the Eternal Consciousness through meditation. By reestablishing equilibrium between Shakti and Shiva, a person can return to a state of Eternal Bliss or the state of Brahma. Brahma can be experienced through Tantra Yoga by exploring and mastering the mind to the point where it realizes its connection with Brahma. Tantra Yoga uses two ways to connect with Brahma. One way is by releasing a person from addictive activities and the other is to practice yoga. Yoga helps a person overcome their addictions and also deepen a person’s feeling of connection with Brahma. The end product is the experience of the Eternal Bliss. The correct ways of meditating are taught by Acharyas who give initiation and lessons on yoga as representatives of the Guru (God). 23

Ananda Marga uses the Sixteen Points 24 , created by P.R. Sarkar, which is an important system of spiritual practices, to help guide its followers to maximize their own personal growth. Although few people can actually follow the Sixteen Points perfectly, these practices can help balance the physical, mental, and spiritual parts of human life. Members of Ananda Marga are encouraged to try and follow these points as strictly as possible. Below is a basic outline of the Sixteen Points, provided by “Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Practices” edited by Tarak, but it is suggested that they should be learned from a person who has experienced them. The Sixteen Points are split up into two sections and are as follows:

Jaeva Dharma (Maintenance of Existence)

Use of Water

Water should be poured over the genital area after passing urine. Pouring cool water over this area counteracts this heat build-up and causes the muscles to contract, thereby entirely emptying the urinary bladder. The reason for this practice is because any residual urine in the bladder can cause a glandular imbalance and result in disease, excessive sexual stimulation, and general wastage of physical and mental energy. 25

Skin

If possible, males should be circumcised. This prevents many diseases and maintains all-round cleanliness. If not circumcised, males should clean and pull back the foreskin regularly, so as to prevent the accumulation of urine sediments. 26

Joint Hair

Hair under the arms, on the legs and in the pubic area should not be shaved. It grows naturally to provide a balance in body heat and is important for good health. Joint hair (armpits and genitals) should be cleaned with soap daily and oiled with coconut oil. 27

Underwear

Males should wear a laungota to protect the genital area, prevent excessive sexual stimulation and divert the seminal flow. Women should wear bra and underwear to protect the genital area, prevent excessive sexual stimulation and prevent infections. 28

Vya’Paka Shaoca (Half Bath)

This practice is done before meditation, meals, and sleep. To take a half-bath one systematically cleans certain areas of the body with cool water, the genital area, knees, calves, feet, elbows, lower arms, mouth, eyes, nose, back of the mouth, throat, tongue, ears, and back of neck. This is done to prevent build-up of body heat; it also helps relax the body creating an ideal calm state for meditation. 29

Bath

A full bath should be taken at least once a day. Cool water (all water used should be no higher than body temperature) should be used unless one has a cold. If one does have a cold, lukewarm water should be used in a closed area. Baths should be taken four times a day at very specific times, the morning, noon, evening, and midnight. The wet skin should be dried either by sunlight or light from a white light bulb. 30

Food

“It is preferable to eat sentient food rather than mutative food, while static food should be avoided.” The reason for this is that mutative foods contain stimulants and static foods requires one to kill an animal and is unhealthy for the body. Meals should be eaten at regular times throughout the day and no more than four meals should be eaten. Other meal etiquette should be followed such as not eating when one is not hungry, drinking plenty of water throughout the day, and eating with others rather than alone. 31

Bha’Gavad Dharma (The Path to Salvation)

Upavasa

Members of Ananda Marga should fast the eleventh day after the full or new moon (Ekadshii), and should not eat food or drink water during this time. A person that is pregnant or suffers from medical ailments does not need to fast. “Fasting generates willpower” and “generates empathy with the sufferings of the poor and also of animals and plants.” 32

Sa’Dhana’

This word defines the conscious effort that a person takes to achieve the goal of enlightenment. “An aspirant enters the realm of Sadhana by receiving initiation into the process of meditation.” This initiation is important to the life of a spiritual seeker as he/she learns about meditation, which is made up of a system of six lessons. Meditation is taught by an Acarya, or teacher and it should be done twice a day. As well as meditation, Sadhana is also made up of other spiritual practices. 33

Madhuvidya (also called Guru mautra) – It is the second lesson in Ananda Marga’s system of meditation. It should be performed before sleeping, eating, meditating, and bathing. 34

Sarva’tmaka Shaoca – Meaning “all round cleanliness.” A person’s body, clothes, and environment should be kept clean. A person should keep their mind clear. 35

Tapah – Meaning service. Sarkar outlines four services and one should try and perform all four types of service every day. 36

Bhuta Yajina – “Service to the created world.” One should be kind to animals, plants, and inanimate objects. 37

Pitr Yajina – “Service to ancestors.” 38

Nr Yajina – “Service to humanity.” There are four different ways to perform this: physical labor, giving financial support, physical strength and courage, and using one’s intellectual strength. Paincaseva (five services) should be done daily and can be accomplished by distributing free food, selling cheap vegetarian food, distributing clothing, medical supplies, or books and educational supplies. 39

Adhya’tma Yajina – “Spiritual Service.” An internal form of service throughout the day and during meditation. 40

Sva’dhya’ya – To understand spiritual materials fully. By reading Sarkar’s books, one is able to clearly understand what the goal to reach for is. By reading, one is also able to understand one’s own spiritual experiences. 41

Asanas (or Innercises) – These yoga postures should be done in the presence of an Acarya and done twice a day (morning and evening). 42

Pashas and Ripus – Individuals acquire eight pa’shas (bondages) as they interact with the world around them. These bondages are shame, fear, doubt, hatred, pride of decent, pride of culture, egoistic feeling, and hypocrisy. There are also six internal bondages, which are physical desire, anger, greed, attachment, pride, and envy. To control the internal bondages, Sadhana is used and Yama and Niyama are used to control the societal bondages. 43

Kiirtan – A spiritual dance that should be done before Sadhana. This dance loosens the body to help the ease of movement and also helps create a calm state of mind. 44

Pa’incajanya – Every morning at 5 a.m. one should follow the yoga routine of kiirtan and sadhana. This is the time when spiritual elevation can be optimized. 45

Guru Saka’sha – This means to be near the Guru. At dawn, when one rises, one should think of Guru and do internal service to him. 46

Is’ta – This term defines “the chosen ideal.” It is the goal of the Absolute, which is personalized for us. “No negative remarks against the Guru should be tolerated and duties given by the Guru should be followed.” 47

A’darsha – The term means ideology. “The path by which [a person] move[s] towards [their] chosen goal. [A person] should not compromise [their] ideology nor allow others to ridicule it without making an effort to explain [their] position properly and logically. One should read Baba’s books and become competent in the spiritual and social philosophy of Ananda Marga.” 48

Conduct Rules – One should strictly follow the Conduct Rules. These rules help during Sadhana by helping keep one’s ideation. Understanding and following of Yama, Hiyama, the 15 Shiilas (Social Conduct rules), the Supreme Command, the One Point Local (one should not compromise the sanctity of Is’ta, A’darsha, the Conduct Rules, and Supreme Command) and the 40 Social Norms will help one maintain mental equilibrium. 49

Supreme Command – This is the “fundamental guidepost for all Margiis to follow.” One should follow the Supreme Command strictly. 50

Dharmacakra – This is the weekly collective meditation sessions. In these sessions, one can be in the company of the Absolute Entity, or the Lord. “If one misses Dharmacakra, one should go to the jagriti (house of spiritual awakening) and perform sadhana that day.” If jagriti is also missed, a meal should be missed and given to a needy person. 51

Oaths – Every morning one should think about the oaths that they have taken and make the conscious effort to put them into practice. 52

C.S.D.K – Each letter stands for a practice that will help increase one’s knowledge of Ananda Marga as well as reinforces their spirituality.

C. Conduct Rules: One should know and follow these rules.

S. Seminar: “One should try to attend all seminars and retreats which are available.”

D. Duty: Any duty that is given by one’s acarya or another superior should be done happily.

K. Kiirtan, Tandava, and Kaoshikii: Kiirtan should be danced every day. Tandava should also be danced by men twice a day and Kaoshikii by women. Tandava should not be done by a woman. 53

Sarkar also called himself the “Leader of the New Renaissance.” In 1958 he established Renaissance Universal (RU). It was created to help raise social awareness of humankind and strives for universal peace. It is believed that art and science should be used for service and self-realization rather than negative uses (i.e. money and creating weapons), that the gap between the rich and the poor should shrink by improving the condition of the lower class, improving education, and promoting unity and cultural diversity. RU accomplishes this by participating in service projects around the world. RU is a global organization and has sectors in about 150 countries around the world. 54

The practices of Ananda Marga are not uncommon to other religions. One such group is the Self-Realization Fellowship. This group is older than Ananda Marga (founded in 1920), but the similarities are apparent. Ananda Marga and the Self-Realization Fellowship both share the philosophy of Self-Realization (that fufillment can be achieved from within) and both also practice yoga and consider it an important practice in their spiritual lives. 55

Bibliography

Ananda Marga. 1981. The Spiritual Philosophy of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti. Denver, CO: Ananda Marga Publications.

Ananda Marga. 1993. Shrii P.R. Sakar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Anandamitra, Didi. The Philosophy of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti, A Commentary on Ananda Sutram. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Anandamurti, Shrii Shrii. 1973. Baba’s Grace; Discourses of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti. Los Altos Hills, California: Ananda Marga Publications.

Anandamurti, Shrii Shrii. 1973. The Great Universe: Discourses on Society. Los Altos Hills, California: Ananda Marga Publications.

Anandamurti, Shrii Shrii. 1993. Discourses on Tanrta. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Avadhuta, Ácárya Vijayánanda. 1994. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Ánandamúrti. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Avadhuta, Shraddhananda. 1991. My Spiritual Life with Baba. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Avt., Tadbhavananda. 1990. Shraddhainjali. New Delhi: PROUT Research Center.

Bowler, John. 1997. Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Devadatta and Nandita. 1971. Paths of Bliss, Ananda Marga Yoga. Wichita, KS: Ananda Marga Publications.

Dhruvananda. 1991. The Supreme Friend: My Days with Baba. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Kamaleshvahananda, Dada Acarya. 1999. Yogic Treatment and Natural Remedies. Chiang Mai, Thailand: (transcript of his presentation at the 33rd World Vegetarian Congress).

Melton, J. Gordon. 1978 .The Encyclopedia of American Religions. Wilmington, N.C.: Mcgrath Publishing Co.

Sarkar, P.R [translated by Vijayananda Avadhuta and Jayanta Kumar]. 1990. Yoga Psychology. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

Tarak, ed. 1990. Anada Marga, Social and Spiritual Practices. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications.

References

1. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p78.

2. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p7.

3. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p7.

4. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p77.

5. http://www.anandamarga.org/books/index.html

6. Bowler, John. Oxford Dictionary of World Religions . Oxford, Oxford University Press, p.62.

7. http://www.anandamarga.org/- click on “BRIEF STORY” paragraph five.

8. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p6&10.

9. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p31&35-36.

10. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p40.

11. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p77.

12. Vijayananda, Acarya. The Life and Teachings of Shrii Shrii Anandamurti . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p81-83.

13. http://www.anandamarga.org/- click on “BRIEF STORY” paragraph two.

14. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p2.

15. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p4-5.

16. Bowler, John. Oxford Dictionary of World Religions . Oxford, Oxford University Press, p.62 and Melton, J. Gordon. The Encyclopedia of American Religions . Wilmington, N.C.: McGrath Publishing Co., p381.

17. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p7.

18. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p3 and http://www.amurt.org/About.html, http://www.amurt.org/development.html, and http://www.amurt.org/disaster.html.

19. http://www.amurt.org/Women.html, http://home1.pacific.net.sg/~rucira/amurtel/relief.html, http://home1.pacific.net.sg/~rucira/amurtel/children.html, and http://home1.pacific.net.sg/~rucira/amurtel/women.html.

20. http://www.anandamarga.org/- click on “BRIEF STORY”

21. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p4-5 and http://www.prout.org/Summary.html.

22. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p7.

23. http://www.abhidhyan.org/Teachings/Tantra_Yoga_Tradition.htm.

24. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p3-4.

25. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p5.

26. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p5.

27. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p5.

28. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p6.

29. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p6-7.

30. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p7-8.

31. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p8-9.

32. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p10-11.

33. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p11-12.

34. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p12-13.

35. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p13.

36. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p13.

37. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p13.

38. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p13.

39. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p13-14.

40. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p14.

41. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p14.

42. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p14.

43. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p15.

44. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p15.

45. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p15.

46. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p.15-16.

47. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p16.

48. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p17.

49. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga

Publications., p17-18.

50. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p18.

51. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p18-19.

52. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p19.

53. Edited by Tarak. Ananda Marga: Social and Spiritual Pracices . Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p19-20.

54. Ananda Marga Shrii P.R. Sarkar and His Mission. Calcutta: Ananda Marga Publications., p2 and http://www.ru.org/ru.html under “Principles of Renaissance Universal.”

55. http://religiousmovements.lib.virginia.edu/nrms/SelfReal.html under “Beliefs.”

Created by Angela An

For Soc 257, New Religious Movements

University of Virginia

Spring Term, 2000

Last modified: 07/17/01

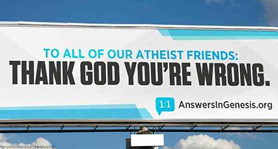

with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world (Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). The most prominent creationist museums in the U.S. was established by Answers in Genesis.

with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world (Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). The most prominent creationist museums in the U.S. was established by Answers in Genesis. CSF board in Australia sent Ham to work with Dr. Henry Morris’s Institute for Creation Research (ICR) in 1987 as a speaker; he remained the Director of the Australian CSF ministry until 2004. Ham went on to lecture not only in the U.S. but also in the U.K.

CSF board in Australia sent Ham to work with Dr. Henry Morris’s Institute for Creation Research (ICR) in 1987 as a speaker; he remained the Director of the Australian CSF ministry until 2004. Ham went on to lecture not only in the U.S. but also in the U.K. creationists, attempt to validate biblical dating and the biblical creation narrative. Answers in Genesis (AIG) can be categorized as Young-Earth Creationists (YECs). AIG asserts that the Bible is the word of God and the absolute authority on all matters. The Board of AIG explains that any evidence in any area of knowlege must be confirmed by the Bible to be valid. As AIG puts the matter, “no apparent, perceived or claimed evidence in any field, including history and chronology, can be valid if it contradicts the scriptural record” (Answers in Genesis 2012). Therefore, AIG accepts the Bible as the accurate historical account of Earth’s creation recorded in Genesis 3:14-19 (Ross, 2005). From its perspective, the organization of the natural world is “irreducibly complex” and could only have been originally designed (Petto & Godfrey, 2007).

creationists, attempt to validate biblical dating and the biblical creation narrative. Answers in Genesis (AIG) can be categorized as Young-Earth Creationists (YECs). AIG asserts that the Bible is the word of God and the absolute authority on all matters. The Board of AIG explains that any evidence in any area of knowlege must be confirmed by the Bible to be valid. As AIG puts the matter, “no apparent, perceived or claimed evidence in any field, including history and chronology, can be valid if it contradicts the scriptural record” (Answers in Genesis 2012). Therefore, AIG accepts the Bible as the accurate historical account of Earth’s creation recorded in Genesis 3:14-19 (Ross, 2005). From its perspective, the organization of the natural world is “irreducibly complex” and could only have been originally designed (Petto & Godfrey, 2007). their creation museum. Two efforts to rezone land for the project met strong opposition from evolution proponents and other secular groups. Despite this resistance, hundreds of radio stations began featuring AIG’s Answers program. By 2006, AIG’s website, AnswersInGenesis.org, was chosen out of 1,300 ministries to receive the “Website of the Year” award from the National Religious Broadcasters. The website has gone on to host about 25,000 visitors a day. The AIG magazine, Creation, which was originally published in Australia, is also distributed in the United States. In 2006, however, AIG-US discovered that over half their subscribers did not renew their subscriptions after one year. The organization recognized the need for a new magazine, Answers , which would feature biblical and scientific articles about the origins controversy and emphasize the biblical worldview with practical applications. Further differences between the American and Australian branches caused AIG-US to stop distributing Creation and focus solely on Answers. After only five years in operation, Answers received the “Award of Excellence” from the Evangelical Press Association (Ham n.d.).

their creation museum. Two efforts to rezone land for the project met strong opposition from evolution proponents and other secular groups. Despite this resistance, hundreds of radio stations began featuring AIG’s Answers program. By 2006, AIG’s website, AnswersInGenesis.org, was chosen out of 1,300 ministries to receive the “Website of the Year” award from the National Religious Broadcasters. The website has gone on to host about 25,000 visitors a day. The AIG magazine, Creation, which was originally published in Australia, is also distributed in the United States. In 2006, however, AIG-US discovered that over half their subscribers did not renew their subscriptions after one year. The organization recognized the need for a new magazine, Answers , which would feature biblical and scientific articles about the origins controversy and emphasize the biblical worldview with practical applications. Further differences between the American and Australian branches caused AIG-US to stop distributing Creation and focus solely on Answers. After only five years in operation, Answers received the “Award of Excellence” from the Evangelical Press Association (Ham n.d.). 2007. Ham created the Creation Museum to spread “Biblically correct science” to the public and to try and bring Creationism into the mainstream. He preferred a museum to a church because museums are accepted as places of public education and for the display of scientific research findings. Further, a museum is a more engaging environment in which to encourage learning among children. Finally, a museum could connect directly with visitors and AIG’s message would not be filtered through mainstream scientists or the government (Duncan 2009). According to Ham, AIG simply wants the Creation Museum to tell people that “the Bible is true and the Bible is God’s word, that’s what it’s all about” (Jacoby, 1998). The museum features a planetarium, the Johnson Observatory, SFX Theater, a petting zoo, an insectarium, a zip-line course, dinosaur fossils, and animatronic exhibits. The Creation Museum was very successful in its first year, attracting 404,000 visitors but suffered declining visitation, with only 280,000 visitors in 2012.

2007. Ham created the Creation Museum to spread “Biblically correct science” to the public and to try and bring Creationism into the mainstream. He preferred a museum to a church because museums are accepted as places of public education and for the display of scientific research findings. Further, a museum is a more engaging environment in which to encourage learning among children. Finally, a museum could connect directly with visitors and AIG’s message would not be filtered through mainstream scientists or the government (Duncan 2009). According to Ham, AIG simply wants the Creation Museum to tell people that “the Bible is true and the Bible is God’s word, that’s what it’s all about” (Jacoby, 1998). The museum features a planetarium, the Johnson Observatory, SFX Theater, a petting zoo, an insectarium, a zip-line course, dinosaur fossils, and animatronic exhibits. The Creation Museum was very successful in its first year, attracting 404,000 visitors but suffered declining visitation, with only 280,000 visitors in 2012. located on 800 acres near Interstate 75 in Grant County, Kentucky and is scheduled to open in the summer of 2016 (Ham, n.d.). The Ark Encounter is described as “a 160-acre park with a life-size replica of Noah’s Ark built to stand 500 feet long and 80 feet high” (Goodwin 2012). Initial construction plans were delayed until 2014 due to a weak economy and a decline in visitation to the Creation Museum (Goodwin 2012). Based on outside consulting term estimates, AIG has anticipated 1,600,000 visitors in its first year, as well as improved visitation. The initial financial projections were also optimistic as a result of tax breaks pledged by the State of Kentucky; these were withdrawn after considerable controversy concerning church-state separation (Alford 2010; “Kentucky” 2015). AIG subsequently announced plans to sue Kentucky over the withdrawal (Linshi 2015).

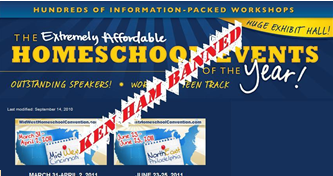

located on 800 acres near Interstate 75 in Grant County, Kentucky and is scheduled to open in the summer of 2016 (Ham, n.d.). The Ark Encounter is described as “a 160-acre park with a life-size replica of Noah’s Ark built to stand 500 feet long and 80 feet high” (Goodwin 2012). Initial construction plans were delayed until 2014 due to a weak economy and a decline in visitation to the Creation Museum (Goodwin 2012). Based on outside consulting term estimates, AIG has anticipated 1,600,000 visitors in its first year, as well as improved visitation. The initial financial projections were also optimistic as a result of tax breaks pledged by the State of Kentucky; these were withdrawn after considerable controversy concerning church-state separation (Alford 2010; “Kentucky” 2015). AIG subsequently announced plans to sue Kentucky over the withdrawal (Linshi 2015). Homeschool Conventions, Inc. (GHC) voted to disinvite Ken Ham and AIG from “all future conventions [as Ham made] unnecessary, ungodly, and mean-spirited statements that are divisive at best and defamatory at worst” (Blackford 2011) about another speaker at the convention. The board stated that “Ken’s public criticism of the convention itself and other speakers at [the] convention require him to surrender spiritual privilege of addressing a homeschool audience” (Blackford 2011). Ham, in his blog, explained that Peter Enns of the BioLogos Foundation teaches misleading information about Genesis that compromises Genesis with evolution and is an “outright liberal theology that totally undermines the authority of the Word of God” (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). After the allegations against Ham being un-Christian and sinful were made, AIG launched an internal investigation of GHC, but has yet to find any resolution (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011).

Homeschool Conventions, Inc. (GHC) voted to disinvite Ken Ham and AIG from “all future conventions [as Ham made] unnecessary, ungodly, and mean-spirited statements that are divisive at best and defamatory at worst” (Blackford 2011) about another speaker at the convention. The board stated that “Ken’s public criticism of the convention itself and other speakers at [the] convention require him to surrender spiritual privilege of addressing a homeschool audience” (Blackford 2011). Ham, in his blog, explained that Peter Enns of the BioLogos Foundation teaches misleading information about Genesis that compromises Genesis with evolution and is an “outright liberal theology that totally undermines the authority of the Word of God” (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). After the allegations against Ham being un-Christian and sinful were made, AIG launched an internal investigation of GHC, but has yet to find any resolution (Answers in Genesis Board of Directors 2011). He stated that “If we raise a generation of students who don’t believe in the process of science, who think everything that we’ve come to know about nature and the universe can be dismissed by a few sentences translated into English from some ancient text, you’re not going to continue to innovate” (Lovan 2012). For his part, Ham attempted to substantiate the YEC model of the universe’s origins. He reasserted that Earth was created by God approximately 6,000 years ago and dinosaurs and humans once coexisted, as it is specifically stated in the Genesis. Nye sought to refute Ham’s claims by citing widely supported observations by scientists that the Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old. Ham responded that “I believe science has been hijacked by secularists…and that there is a difference between historical science and observational science” (“Bill Nye Debates Ken Ham” 2014). Nye pointed out that a variety of methodologies (radiometric dating, ice core data, and the light from distant stars) supports the position that the Earth is much older than 6,000 years (Lovan 2012). When Ham referred to the Genesis flood narrative and Noah’s Ark, Nye pointed out that the Ark as described in the Book of Genesis would not float. Nye also pointed out that, using Nye’s calculations, an ark containing 7,000 kinds of animals would require that approximately eleven new species would have to come into existence every day for the Earth to contain all presently known species (O’Neil 2014). While Ham does not have appeared to have won over a majority of the audience, he seemed unconcerned. From his perspective, the publicity generated by the debate was a source of fundraising for AIG’s construction of the Ark Encounter theme park (Chowdhury 2014).

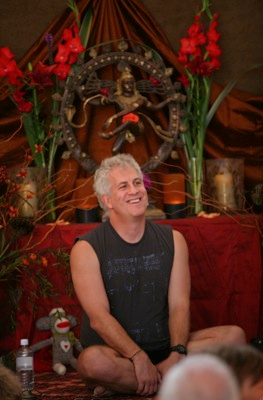

He stated that “If we raise a generation of students who don’t believe in the process of science, who think everything that we’ve come to know about nature and the universe can be dismissed by a few sentences translated into English from some ancient text, you’re not going to continue to innovate” (Lovan 2012). For his part, Ham attempted to substantiate the YEC model of the universe’s origins. He reasserted that Earth was created by God approximately 6,000 years ago and dinosaurs and humans once coexisted, as it is specifically stated in the Genesis. Nye sought to refute Ham’s claims by citing widely supported observations by scientists that the Earth is approximately 4.5 billion years old. Ham responded that “I believe science has been hijacked by secularists…and that there is a difference between historical science and observational science” (“Bill Nye Debates Ken Ham” 2014). Nye pointed out that a variety of methodologies (radiometric dating, ice core data, and the light from distant stars) supports the position that the Earth is much older than 6,000 years (Lovan 2012). When Ham referred to the Genesis flood narrative and Noah’s Ark, Nye pointed out that the Ark as described in the Book of Genesis would not float. Nye also pointed out that, using Nye’s calculations, an ark containing 7,000 kinds of animals would require that approximately eleven new species would have to come into existence every day for the Earth to contain all presently known species (O’Neil 2014). While Ham does not have appeared to have won over a majority of the audience, he seemed unconcerned. From his perspective, the publicity generated by the debate was a source of fundraising for AIG’s construction of the Ark Encounter theme park (Chowdhury 2014). She referred him to Douglas Brooks, a scholar of Tantra who teaches at Rochester University. Brooks was, at that time, translating the Kularnava Tantra while residing at Shree Muktananda Ashram, a major center for Siddha Yoga – a type of meditation-based yoga brought to the United States in the 1970s by Muktananda and now led by Gurumayi. Friend consulted with Brooks just as he was translating a sentence from the scripture as, “By stepping into the current of grace, the student becomes capable of holding what is of value from the guru.” The word anusara comes from saras, which means flowing. The literature of Anusara yoga translates anusara as “flowing with grace,” drawing on the larger context of the sentence. Friend continued to consult scholars of Tantra whom he had befriended during his stays at this ashram as he developed Anusara yoga, but Friend is the ultimate architect.

She referred him to Douglas Brooks, a scholar of Tantra who teaches at Rochester University. Brooks was, at that time, translating the Kularnava Tantra while residing at Shree Muktananda Ashram, a major center for Siddha Yoga – a type of meditation-based yoga brought to the United States in the 1970s by Muktananda and now led by Gurumayi. Friend consulted with Brooks just as he was translating a sentence from the scripture as, “By stepping into the current of grace, the student becomes capable of holding what is of value from the guru.” The word anusara comes from saras, which means flowing. The literature of Anusara yoga translates anusara as “flowing with grace,” drawing on the larger context of the sentence. Friend continued to consult scholars of Tantra whom he had befriended during his stays at this ashram as he developed Anusara yoga, but Friend is the ultimate architect. 1,500 instructors and 500,000 practitioners in seventy countries. All of this came to a grinding halt in 2012 – just at the start of Friend’s “Igniting the Center 2012 World Tour” that was to add yantras (sacred geometry) and pyramid power to the mixture of practices. In February, a website posted incriminating evidence against Friend, which is detailed in the Issues/Challenges section below. Currently, after a brief hiatus for self-reflection and therapy, Friend is back on a touring schedule, acting outside of the Anusara yoga organization as an independent hatha yoga instructor – albeit “one of the most knowledgeable and experienced hatha yoga teachers in the world,” according to Friend’s website (“About John Friend” n.d.).

1,500 instructors and 500,000 practitioners in seventy countries. All of this came to a grinding halt in 2012 – just at the start of Friend’s “Igniting the Center 2012 World Tour” that was to add yantras (sacred geometry) and pyramid power to the mixture of practices. In February, a website posted incriminating evidence against Friend, which is detailed in the Issues/Challenges section below. Currently, after a brief hiatus for self-reflection and therapy, Friend is back on a touring schedule, acting outside of the Anusara yoga organization as an independent hatha yoga instructor – albeit “one of the most knowledgeable and experienced hatha yoga teachers in the world,” according to Friend’s website (“About John Friend” n.d.). teachers are now the owners and managers of the newly formed Anusara School of Hatha Yoga (ASHY) ®: BJ Galvan, William Savage, and Jane Norton.

teachers are now the owners and managers of the newly formed Anusara School of Hatha Yoga (ASHY) ®: BJ Galvan, William Savage, and Jane Norton. William “Doc” Savage specializes in one-on-one yoga therapy sessions. He has been teaching yoga for five years after studying under many teachers, including John Friend, Adam Ballenger, BJ Galvan, and Martin and Jordan Kirk. Savage also traveled to India with Douglas Brooks in order to deepen his understanding of Tantra. Prior to teaching yoga, he spent twenty-two years in the U.S. Air Force. He and his wife, Donna, teach yoga in the Black Hills of South Dakota as well as regionally under the moniker Dakota Yogi.

William “Doc” Savage specializes in one-on-one yoga therapy sessions. He has been teaching yoga for five years after studying under many teachers, including John Friend, Adam Ballenger, BJ Galvan, and Martin and Jordan Kirk. Savage also traveled to India with Douglas Brooks in order to deepen his understanding of Tantra. Prior to teaching yoga, he spent twenty-two years in the U.S. Air Force. He and his wife, Donna, teach yoga in the Black Hills of South Dakota as well as regionally under the moniker Dakota Yogi. recover from injury and chronic pain conditions. From 2005-2007,she toured the United States as Anusara yoga’s boutique manager. Norton lives on the island of Martha’s Vineyard and enjoys cooking, beachcombing, and gardening.

recover from injury and chronic pain conditions. From 2005-2007,she toured the United States as Anusara yoga’s boutique manager. Norton lives on the island of Martha’s Vineyard and enjoys cooking, beachcombing, and gardening. The body becomes the axis mundi toward which all levels of reality coalesce and which elevates the physical toward the spiritual. Each Anusara yoga class begins with an invocation that Friend had learned from his mother at an early age and which he encountered again during his time with Siddha Yoga. He asked Krishna Das to write a melody for the verses, which serve to unite Anusara yoga students from around the world. The Sanskrit words are rendered on the back of Anusara yoga invocation cards as, “I honor the essence of Being, the Auspicious One, the luminous teacher within and without, who assumes the forms of Truth, Consciousness, and Bliss, is never absent, full of peace. Who is ultimately free and sparkles with a divine luster.” (This is more of an interpretation than direct translation; the first words, for example, namah shivaya gurave translate more directly as, “I bow to the Guru, who is Shiva.”) If the class is being taught in a more secular setting such as a gym, the opening mantra may be omitted or replaced with a simple chant of om three times.

The body becomes the axis mundi toward which all levels of reality coalesce and which elevates the physical toward the spiritual. Each Anusara yoga class begins with an invocation that Friend had learned from his mother at an early age and which he encountered again during his time with Siddha Yoga. He asked Krishna Das to write a melody for the verses, which serve to unite Anusara yoga students from around the world. The Sanskrit words are rendered on the back of Anusara yoga invocation cards as, “I honor the essence of Being, the Auspicious One, the luminous teacher within and without, who assumes the forms of Truth, Consciousness, and Bliss, is never absent, full of peace. Who is ultimately free and sparkles with a divine luster.” (This is more of an interpretation than direct translation; the first words, for example, namah shivaya gurave translate more directly as, “I bow to the Guru, who is Shiva.”) If the class is being taught in a more secular setting such as a gym, the opening mantra may be omitted or replaced with a simple chant of om three times. “opening the heart” is an integral part of the class experience. Following class, community is built in some Anusara yoga studios through chatting over tea. Some Anusara yoga kulas (communities) organize social outings and support each other in times of need by preparing food or offering transportation. Some groups also hold benefits to provide donations to non-profit service organizations.

“opening the heart” is an integral part of the class experience. Following class, community is built in some Anusara yoga studios through chatting over tea. Some Anusara yoga kulas (communities) organize social outings and support each other in times of need by preparing food or offering transportation. Some groups also hold benefits to provide donations to non-profit service organizations. and he had no aspirations of it taking off. Today, it is estimated that UCTAA has over 10,000 members in over 40 countries, but no accurate membership records exist (“History” n.d.). Tyrrell is responsible for the bulk of the website’s maintenance. He personally responds to questions from the public, which he then posts on the site in a section called “Ask the Patriarch.”

and he had no aspirations of it taking off. Today, it is estimated that UCTAA has over 10,000 members in over 40 countries, but no accurate membership records exist (“History” n.d.). Tyrrell is responsible for the bulk of the website’s maintenance. He personally responds to questions from the public, which he then posts on the site in a section called “Ask the Patriarch.” loose rule. There is commentary on the website, but disciples are encouraged to interpret the articles as they see fit. According to the founder, the first article is based on the belief that faith is not the same as empirical knowledge, and thus there is no evidence for or against the existence of a Supreme Being. The only certain position on the matter is that we do not know. The second article proposes that if there is a Supreme Being, it is indifferent to our existence. This is contingent on the understanding that all events in our Universe are explainable regardless of the existence or nonexistence of a Supreme Being. The final article maintains that, based on the first two, there is no reason to trouble oneself with pondering the existence of a Supreme Being.

loose rule. There is commentary on the website, but disciples are encouraged to interpret the articles as they see fit. According to the founder, the first article is based on the belief that faith is not the same as empirical knowledge, and thus there is no evidence for or against the existence of a Supreme Being. The only certain position on the matter is that we do not know. The second article proposes that if there is a Supreme Being, it is indifferent to our existence. This is contingent on the understanding that all events in our Universe are explainable regardless of the existence or nonexistence of a Supreme Being. The final article maintains that, based on the first two, there is no reason to trouble oneself with pondering the existence of a Supreme Being.

Quebec) on September 14, 1921. Despite an early wish to live a celibate religious life, she was advised against that course by the Church. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917- 1997 ) who worked at various jobs and also went into local politics. In 1948, they moved to the town Saint-Georges de Beauce. A life full of sickness and suffering for both her and her husband ensued. Her marital life proved to be so problematic (a “nightmare” in her words) that it led to a divorce in 1957 and an out-of-home placement of her five children (André Louise, Michèle, Pierre, and Danielle). However, much later, after she had established the Army of Mary, she partially reconciled with her husband when he became a member of the movement. Meanwhile, while trying to overcome her traumas by giving a place to the celestial voices she had been hearing since she was twelve, Giguère was increasingly drawn into Marian spirituality and devotionalism. Although Giguere had been hearing certain “interior voices” since her teenage years, these mystical encounters increased significantly after 1957. The unveiling of her providential destiny, which was first announced to her in 1950, finally took place in 1958. While hearing voices and receiving messages from Jesus Christ and Mary, she started writing down her life story and started interpreting the mystical phenomena she was experiencing. The titles of her autobiographical volumes, such as Vie Purgative (Purgative Life), Victoire (Victory), and Vie Céleste (Heavenly Life), indicate the progressive transformations she experienced.

Quebec) on September 14, 1921. Despite an early wish to live a celibate religious life, she was advised against that course by the Church. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917- 1997 ) who worked at various jobs and also went into local politics. In 1948, they moved to the town Saint-Georges de Beauce. A life full of sickness and suffering for both her and her husband ensued. Her marital life proved to be so problematic (a “nightmare” in her words) that it led to a divorce in 1957 and an out-of-home placement of her five children (André Louise, Michèle, Pierre, and Danielle). However, much later, after she had established the Army of Mary, she partially reconciled with her husband when he became a member of the movement. Meanwhile, while trying to overcome her traumas by giving a place to the celestial voices she had been hearing since she was twelve, Giguère was increasingly drawn into Marian spirituality and devotionalism. Although Giguere had been hearing certain “interior voices” since her teenage years, these mystical encounters increased significantly after 1957. The unveiling of her providential destiny, which was first announced to her in 1950, finally took place in 1958. While hearing voices and receiving messages from Jesus Christ and Mary, she started writing down her life story and started interpreting the mystical phenomena she was experiencing. The titles of her autobiographical volumes, such as Vie Purgative (Purgative Life), Victoire (Victory), and Vie Céleste (Heavenly Life), indicate the progressive transformations she experienced. teachings when they were published. But, from the early 1980s, people became increasingly worried after closely reading the first published volume of Marie-Paule’s Vie d’Amour. In addition, regional authorities and media were alarmed by the building activities of the Army at the edge of the lake, activities that strengthened the idea of an institutionalizing, self-supportive sectarian community. Nonetheless, it was only after a stream of newspaper articles expressing astonishment at what was actually professed in her scriptures that the bishop of Quebec realized his misjudgment and started to take action against the doctrinal deviations. It caused the new archbishop of Quebec to withdraw the approval of his predecessor. On May 4, 1987, he declared the movement schismatic and disqualified it as a Catholic association because of its false teachings. The Vatican judged their doctrine to be “heretical.” To be completely sure, the archbishop-to-be asked Cardinal Ratzinger to have Marie-Paule’s scriptures also screened by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In a brief note of February 27, 1987, Ratzinger, too, concluded that the movement was in “major and very severe error.” The particular concern was the idea of the alleged existence of an Immaculate Marian Trinity, in which Mary is no longer just Mother of the Son of God, but the divine spouse of God. As a consequence, the theological exegesis of Marie-Paule’s writing by her “theologian,” Marc Bosquart, was likewise condemned. Hence, the Army was forbidden to organize any celebration or to propagate their devotion for the Lady of All Peoples. Priests from the Quebec diocese who got involved would be removed from their priestly functions, although the penalty of excommunication or condemnation was not yet called for.

teachings when they were published. But, from the early 1980s, people became increasingly worried after closely reading the first published volume of Marie-Paule’s Vie d’Amour. In addition, regional authorities and media were alarmed by the building activities of the Army at the edge of the lake, activities that strengthened the idea of an institutionalizing, self-supportive sectarian community. Nonetheless, it was only after a stream of newspaper articles expressing astonishment at what was actually professed in her scriptures that the bishop of Quebec realized his misjudgment and started to take action against the doctrinal deviations. It caused the new archbishop of Quebec to withdraw the approval of his predecessor. On May 4, 1987, he declared the movement schismatic and disqualified it as a Catholic association because of its false teachings. The Vatican judged their doctrine to be “heretical.” To be completely sure, the archbishop-to-be asked Cardinal Ratzinger to have Marie-Paule’s scriptures also screened by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In a brief note of February 27, 1987, Ratzinger, too, concluded that the movement was in “major and very severe error.” The particular concern was the idea of the alleged existence of an Immaculate Marian Trinity, in which Mary is no longer just Mother of the Son of God, but the divine spouse of God. As a consequence, the theological exegesis of Marie-Paule’s writing by her “theologian,” Marc Bosquart, was likewise condemned. Hence, the Army was forbidden to organize any celebration or to propagate their devotion for the Lady of All Peoples. Priests from the Quebec diocese who got involved would be removed from their priestly functions, although the penalty of excommunication or condemnation was not yet called for. “apocalyptic calculation” of verse 5-6 of the book of Revelation. Her passing was expected to take place 1260 days after the start of the Terrestrial Paradise on April 4, 2010. The day passed peacefully, however.

“apocalyptic calculation” of verse 5-6 of the book of Revelation. Her passing was expected to take place 1260 days after the start of the Terrestrial Paradise on April 4, 2010. The day passed peacefully, however. eschatology (nicknamed “The Poet of the End of the Times”) got notice of the Amsterdam apparitions. By 1966, he had already organized a successful conference on the Amsterdam Lady in Paris where he tried to connect the outcome of the Second Vatican Council on Mary to the Amsterdam messages. He stated that all issues that were brought up during and around the Council had to be interpreted as a confirmation of what was revealed in the Amsterdam messages. The text of the conference was published under the transparent title, La Dame de tous les peuples, and he became the single major international propagandist for the Amsterdam cultus. The French book found its way to Catholic Quebec and was given to Giguère by a friend. After rereading it several times, she recognized the resemblances in the messages she and Peerdeman received and became convinced of the structured connection of both mystic experiences. This idea ultimately brought Auclair and Giguère into contact with each other in 1971. Five years later he joined the Army. In those years, with the Church’s condemnation of the Amsterdam cultus and suppression of its local devotional practice, Marie-Paule’s interest in the Lady of All Nations became stronger. The universality of the Amsterdam messages matched her divine promptings and personal ambitions for a global Marian movement within the Marian era. As a result Marie-Paule wanted to meet visionary Peerdeman. In 1973, 1974 and 1977, she visited the Amsterdam shrine of the Lady of All Nations. Her last visit proved to constitute a new sequel to the Amsterdam apparitions and created an impulse for a shift of the core of cultus to Quebec. Marie-Paule claimed that during mass at the shrine in Amsterdam the visionary Peerdeman pointed at her (Giguère) while saying, “She is the Handmaiden.” This was taken as proof of what was proclaimed in the Lady’s fifty first message, in which Mary announced her return to earth: “I will return, but in public.” This moment was understood to be a recognition of The Lady of All Nations in the person of Giguère by the visionary Peerdeman. Through this maneuver, Marie-Paule retrospectively appropriated the prophesized public return of Mary on Earth ( Messages 1999: 151). Hence, Giguère claimed the devotion of the Lady in Lac-Etchemin to be the sole continuation of the Amsterdam cultus.

eschatology (nicknamed “The Poet of the End of the Times”) got notice of the Amsterdam apparitions. By 1966, he had already organized a successful conference on the Amsterdam Lady in Paris where he tried to connect the outcome of the Second Vatican Council on Mary to the Amsterdam messages. He stated that all issues that were brought up during and around the Council had to be interpreted as a confirmation of what was revealed in the Amsterdam messages. The text of the conference was published under the transparent title, La Dame de tous les peuples, and he became the single major international propagandist for the Amsterdam cultus. The French book found its way to Catholic Quebec and was given to Giguère by a friend. After rereading it several times, she recognized the resemblances in the messages she and Peerdeman received and became convinced of the structured connection of both mystic experiences. This idea ultimately brought Auclair and Giguère into contact with each other in 1971. Five years later he joined the Army. In those years, with the Church’s condemnation of the Amsterdam cultus and suppression of its local devotional practice, Marie-Paule’s interest in the Lady of All Nations became stronger. The universality of the Amsterdam messages matched her divine promptings and personal ambitions for a global Marian movement within the Marian era. As a result Marie-Paule wanted to meet visionary Peerdeman. In 1973, 1974 and 1977, she visited the Amsterdam shrine of the Lady of All Nations. Her last visit proved to constitute a new sequel to the Amsterdam apparitions and created an impulse for a shift of the core of cultus to Quebec. Marie-Paule claimed that during mass at the shrine in Amsterdam the visionary Peerdeman pointed at her (Giguère) while saying, “She is the Handmaiden.” This was taken as proof of what was proclaimed in the Lady’s fifty first message, in which Mary announced her return to earth: “I will return, but in public.” This moment was understood to be a recognition of The Lady of All Nations in the person of Giguère by the visionary Peerdeman. Through this maneuver, Marie-Paule retrospectively appropriated the prophesized public return of Mary on Earth ( Messages 1999: 151). Hence, Giguère claimed the devotion of the Lady in Lac-Etchemin to be the sole continuation of the Amsterdam cultus. In order to give public access to Our Lady of All Peoples in Lac-Etchemin, a church was built within the international Spiri-Marie Center complex. The complex is more a headquarters of an international movement than a dedicated shrine for the Lady of All Peoples or her reincarnation. In an adjacent building to the church, a big shop where books, images, DVD’s are stacked and show the missionary character of the center. Candles, rosaries and all kinds of other devotional material also can be bought for home use or in the Spiri-church. The morphology of the objects seems to be mainstream Catholic, although the symbolism is adapted to the Community’s teachings. Many of the devotional practices are to a large extent in line with those of the formal Catholic Church. The whole décor of the interior is directly inspired by the “original” Amsterdam shrine of the Lady and its imagery. However, a closer look at the décor also shows the symbolism and texts of the movement’s heretical doctrines. For example, one

In order to give public access to Our Lady of All Peoples in Lac-Etchemin, a church was built within the international Spiri-Marie Center complex. The complex is more a headquarters of an international movement than a dedicated shrine for the Lady of All Peoples or her reincarnation. In an adjacent building to the church, a big shop where books, images, DVD’s are stacked and show the missionary character of the center. Candles, rosaries and all kinds of other devotional material also can be bought for home use or in the Spiri-church. The morphology of the objects seems to be mainstream Catholic, although the symbolism is adapted to the Community’s teachings. Many of the devotional practices are to a large extent in line with those of the formal Catholic Church. The whole décor of the interior is directly inspired by the “original” Amsterdam shrine of the Lady and its imagery. However, a closer look at the décor also shows the symbolism and texts of the movement’s heretical doctrines. For example, one  can pray with a combined image of Jesus and Mary that suggests that Mary is present in the eucharist. The central devotional practice is dedicated to the “Triple White” (the eucharist, the Immaculate Mary, and the Pope) through which the sanctification of one’s soul should be realized, inspire the world and the spread the evangelical message of love and peace in anticipation of the return of Christ. Within the cultus no public Marian apparition rituals are known; all messages and appearances seem to be privately received by Giguère.

can pray with a combined image of Jesus and Mary that suggests that Mary is present in the eucharist. The central devotional practice is dedicated to the “Triple White” (the eucharist, the Immaculate Mary, and the Pope) through which the sanctification of one’s soul should be realized, inspire the world and the spread the evangelical message of love and peace in anticipation of the return of Christ. Within the cultus no public Marian apparition rituals are known; all messages and appearances seem to be privately received by Giguère. well, as the feminine (the immaculate) is also present in God. Their explanation states that the first coming of the Immaculate Mary is symbolized in the first number 5, and the second coming (Marie-Paule) is represented in double five’s. The double fives represents her actions with the “True Spirit,” namely the Holy Spirit of Mary, a work that started in the year 2000 and which will realize the number 555 when it is finished. This will occur when the new millennium has arrived. In the movement’s systematization, the numbers are supposed to connect the cultus to its origins and close the circle. It would place the formation of the cultus in line with what God reportedly prophesied to Giguère in 1958 about her crucifixion and reincarnation, and about the existence of a Marian trinity. The full number of 55 555 then (the Quinternity ) is the symbol of the actions of the Lady of All Peoples with the True (Marian) Holy Spirit. The figure is presented as a holy number that symbolizes future victory over evil (symbolized in the human number of the beast (666)) and the conditional coming of the new millennium (cf Baum 1970:49-63).

well, as the feminine (the immaculate) is also present in God. Their explanation states that the first coming of the Immaculate Mary is symbolized in the first number 5, and the second coming (Marie-Paule) is represented in double five’s. The double fives represents her actions with the “True Spirit,” namely the Holy Spirit of Mary, a work that started in the year 2000 and which will realize the number 555 when it is finished. This will occur when the new millennium has arrived. In the movement’s systematization, the numbers are supposed to connect the cultus to its origins and close the circle. It would place the formation of the cultus in line with what God reportedly prophesied to Giguère in 1958 about her crucifixion and reincarnation, and about the existence of a Marian trinity. The full number of 55 555 then (the Quinternity ) is the symbol of the actions of the Lady of All Peoples with the True (Marian) Holy Spirit. The figure is presented as a holy number that symbolizes future victory over evil (symbolized in the human number of the beast (666)) and the conditional coming of the new millennium (cf Baum 1970:49-63). ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP  Church. Father Jean-Pierre is the head of the Church of John, the Church of Love, which is described by the movement as a “transmutation” of the Roman Church of Peter.

Church. Father Jean-Pierre is the head of the Church of John, the Church of Love, which is described by the movement as a “transmutation” of the Roman Church of Peter. his scientific interests and an ordinary life as a bank employee were not enough; he also became a scholar in Sanskrit literature, and ultimately chose to follow a spiritual path.

his scientific interests and an ordinary life as a bank employee were not enough; he also became a scholar in Sanskrit literature, and ultimately chose to follow a spiritual path. on mantras from Indian tantric traditions (Lowe 2011). A certified teacher gives the mantra to the meditator, and the TM style of meditation is said to be natural, modest and uncomplicated. The meditation technique taught in AoL is quite similar: Sahaj Samadhi Meditation (or Art of Meditation) is what the organization calls a “graceful, natural and effortless” meditation technique.

on mantras from Indian tantric traditions (Lowe 2011). A certified teacher gives the mantra to the meditator, and the TM style of meditation is said to be natural, modest and uncomplicated. The meditation technique taught in AoL is quite similar: Sahaj Samadhi Meditation (or Art of Meditation) is what the organization calls a “graceful, natural and effortless” meditation technique. headquarters in Bangalore, India [Image at right] and Bad Antogast, Germany. Creating a new religion can be a smart business strategy, and, in many ways, AoL functions like any multi-national company. The organization has centers and groups all over the world. Its participants are also customers, who pay for courses, retreats, and brand associated products (like books, DVDs, or Ayurvedic health supplements). AoL brand management is rather successful, which is reflected in the organization’s significant online and social media presence. Business-wise, it makes sense for a movement like AoL to use different “elements of successful branding [which] include fashioning visually striking material artifacts, instituting communally celebrated festivities, creating easily identifiable symbols that designate affiliation, and using iconography and public discourse in order to elevate the […] leader to near-mythic status” (Hammer 2009: 197). The guru can now travel comfortably around the world enjoying the fruits of his labor as a religious entrepreneur (Bainbridge and Stark 1985). While AoL does not attack competing movements, as many devotees have or have had connections to other gurus and movements, Shankar has been known to criticize other religious or secular leaders when the opportunity arises (Tøllefsen 2012).

headquarters in Bangalore, India [Image at right] and Bad Antogast, Germany. Creating a new religion can be a smart business strategy, and, in many ways, AoL functions like any multi-national company. The organization has centers and groups all over the world. Its participants are also customers, who pay for courses, retreats, and brand associated products (like books, DVDs, or Ayurvedic health supplements). AoL brand management is rather successful, which is reflected in the organization’s significant online and social media presence. Business-wise, it makes sense for a movement like AoL to use different “elements of successful branding [which] include fashioning visually striking material artifacts, instituting communally celebrated festivities, creating easily identifiable symbols that designate affiliation, and using iconography and public discourse in order to elevate the […] leader to near-mythic status” (Hammer 2009: 197). The guru can now travel comfortably around the world enjoying the fruits of his labor as a religious entrepreneur (Bainbridge and Stark 1985). While AoL does not attack competing movements, as many devotees have or have had connections to other gurus and movements, Shankar has been known to criticize other religious or secular leaders when the opportunity arises (Tøllefsen 2012). reported extensive damage to water bodies and vegetation at the 1,000-acre festival venue, and a National Green Tribunal committee suggested a fine of 120 crore rupees (about $28,000,000). The fine was subsequently reduced to 50,000,000 rupees (a little over $750,000). A news report in The Diplomat reports “Sri Sri declaring defiantly ‘We’ll go to jail but not pay the fine. We have done nothing wrong’. The matter was ultimately settled after much hullabaloo with AOL coughing up a tiny fraction of the imposed fine.” The World Culture Festival and AoL’s political connections can, however, open the door to further analyses of the organization in a Hindutva context.

reported extensive damage to water bodies and vegetation at the 1,000-acre festival venue, and a National Green Tribunal committee suggested a fine of 120 crore rupees (about $28,000,000). The fine was subsequently reduced to 50,000,000 rupees (a little over $750,000). A news report in The Diplomat reports “Sri Sri declaring defiantly ‘We’ll go to jail but not pay the fine. We have done nothing wrong’. The matter was ultimately settled after much hullabaloo with AOL coughing up a tiny fraction of the imposed fine.” The World Culture Festival and AoL’s political connections can, however, open the door to further analyses of the organization in a Hindutva context. concede that the U.S. was one of, if not the major player in the birth of global Pentecostalism. They further concede that Charles Fox Parham provided a critical theological plank that differentiated Pentecostalism from other Protestant revivals and from the fundamentalist movement. Clearly the healing movement of the late nineteenth century paved the way for Pentecostal experiences, but not all who embraced divine healing would become Pentecostal. It was Parham’s theological linking of the “baptism in the Holy Ghost” to the “evidence” of speaking in tongues (glossolalia) that separated Pentecostals from critics who did not accept the validity of equating what they pejoratively labeled “gibberish” with biblical accounts of “speaking in tongues.” In 1901 Agnes Ozman, a student at Parham’s College of Bethel, a Bible school for adults, added credence to Parham’s theology when she was heard to speak in tongues, an event that many contend launched the Pentecostal movement (Seymour, 2012; Hollenweger 1997; Robeck 2006).