Exu (Eshu)

EXU (ESHU) TIMELINE

1700s: Records exist from the period of the importance of the cult of Legba (Eshu) considered a “great god” and protector of the kings of ancient Dahomey.

1741: The oldest written reference to Exu or Legba was found in Brazil in the “Obra Nova de Língua Geral de Mina,” by Antonio da Costa Peixoto, written from the Ewe language spoken by enslaved Africans in Minas Gerais, Brazil. In this work, the term “Leba” (Legba) was translated as “Demon.”

1800s: Yoruba-English Ewe-French dictionaries published in Europe translated “Exu/Legba” as “Demon.” Yoruba versions of the Bible and Quran followed this translation.

1869: The Public Market of Porto Alegre (Brazil) where the oldest public settlement of Exu (Bará) in Brazil is located was founded; it was constructed by the Africans who built the Market.

1885: The first source in French of a myth about Eshu and a drawing of an altar (image) of the divinity made by Father Baudin in West Africa was published.

1896: The first ethnographic description of a settlement (altar) of Exu in Salvador, Brazil, by physician Raimundo Nina Rodrigues, was published.

1913: The first text on Yoruba myths about the creation of the world in which Eshu takes part was published.

1934: The first photographic record in Brazilian literature of a wooden statue of Exu with a kind of knife in his head and holding two ogós in his hands .

1946: An initiate for Exu in Brazil with her ritual clothes was photographically recorded for the first time.

1960s-and 1970s: Neo-Pentecostal churches formed in Brazil that will start a violent movement of persecution of Afro-Brazilian religions, through the demonization of the Exus and Pombagiras.

2013: The largest collection of photographs of Eshu statues of African and African American origin was published in Eshu, Divine Trickster.

2022: Exu, An Afro-Atlantic God in Brazil, which analyzed the presence of Exu in Africa and the Americas and contained the largest collection of Exu/Legba myths of African, Cuban, and Brazilian origin was published.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Exu or Legba is a messenger god, according to the Fon-Yoruba of West Africa. He is the guarantor of fertility and dynamism, and he took part in the creation of the world and of mankind. He is the guardian of order and, because of his nature as a trickster, of disorder. He is feared, respected, and praised before all others. He is worshipped on a piece of rock (laterite), on a mound of earth shaped like a human head from which protrudes a large phallus (ogó) or an anthropomorphic statue covered in cowries. From the top of his head, he projects a braid or plait, shaped like a penis, or a knife, often culminating in a face. He holds a staff in his hand, also shaped like a penis, and he uses this to move about in time and space. He accepts blood offerings (goats, black cocks, dogs, and pigs) and libations of alcohol and palm oil. He likes to be remembered at crossroads and at thresholds (where boundaries are crossed) as well as in the marketplace (where exchanges take place).

With the arrival of Christianity in Africa at the start of the sixteenth century, Exu was labelled a “Black Priapus,” and his worship was perceived as a demonic act. The kinds of animals offered to him were associated with images used to depict the devil: anthropomorphic beings with ram horns, tails and pig or goat’s hooves, or a “black dog.” Indeed, the offerings Exu “ate” in Africa are comprised of the very same animals whose “bodies shaped the devil” in Europe. One of the results of this “vicious hermeneutic cycle” was the use of the term “Exu” to translate the word “Devil” in the Yoruba version of the Bible, and to substitute “Iblis” and “Shaitan” in the Yoruba version of the Qur’an (Dopamu 1990:20).

In the nineteenth Century, Exu continued to be condemned by modern critics who rejected the kind of magical thinking that prevailed in possession cults (of “animists”) which consecrated “god-objects” and exalted the sacred through music, dance, and the human body. Religions that had not undergone some form of secularization, bureaucratization and “de-mystification” were viewed as especially antagonistic to the development of modernity, even though science and religion were already autonomous spheres.

And so it is that Exu synthesizes an “ethical and moral crossroads” when viewed and interpreted by Western Europe. This goes back to Medieval Europe, which saw its own demons spread throughout the four corners of the globe, so that, by the nineteenth Century, it had come to distinguish rational thought from magical-religious thinking, expansionism from communitarianism, modernity from traditional thinking, and to define good and evil, science and faith in absolute terms.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

In Brazil, due to slavery and forced conversion of enslaved Africans to Catholicism, Exu took on a variety of different forms, including that of messenger god and “keeper of the order,” as well as trickster and engineer of social disorder.

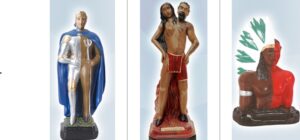

In the first case, he was associated with Catholicism’s mediators, such as Jesus, the Virgin Mary, saints, angels, and martyrs. In Cuba, he was associated with The Boy Jesus. In Brazil, this association stretched to St. Anthony (the martyr who leans on a staff), St. Gabriel (the messenger of the Annunciation), St. Benedict (a black saint who leads Catholic processions to impede rain) and St. Peter, (the gatekeeper who bears the keys to heaven). These Catholic saints share with Exu the arduous task of clearing paths that show humanity the road to God and to the Orishas (in Brazil, Orixás).

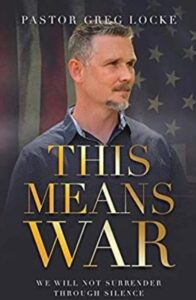

In the second case, Exu was associated with the devil and the spirits of the dead, called “apparitions” or “spirits,” which are believed to torment and trouble people and so must be vanquished (dispatched) in rituals of spiritual cleansing. When incorporated into Umbanda (the African-Brazilian religion with the largest number of followers in Brazil these Exus manifest in people and adopt the names of biblical demons such as Beelzebub [Image at right] and Lucifer.

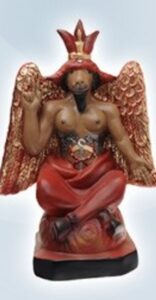

Alternatively they give themselves nicknames borrowed from their dwelling spaces, such as 7 Crossroads-Exu, Gateway-Exu, Catacomb- Exu, Skull-Exu, Mud-Exu, Shadow-Exu, Cemetery-Exu. [Image at right] In their female guise, these Exus are called Pombagira, and in contemporary Brazil are depicted much as devils were depicted in medieval prints, and, throughout the twentieth century, in mystery and horror stories. Whereas in Candomblé there are fewer than a dozen avatars of Exu (Exu Tiriri, Exu Lonã, Exu Marabô etc…) in Umbanda there are many dozens.

According to the “theory of disguises” and “syncretism,” African gods had to conceal themselves “beneath the clothes of Catholic saints” to avoid persecution, and, with the passage of time, this created confusion between them. I argue that these “Demon-Exus” provide continuity with the African concept of Exu and differ from Christian concepts of the devil. Considering the active role played by African agency in this process of cultural contact, it seems to me that this “Demon-Exu” is much more African than he seems. First, because these “Demon-Exus” continue to act as mediators, just like an African Exu. Some of the names listed in these examples were extracted from the Bible, but the vast majority mention points of passage (crossroads, gateways), of intercession between the world of the living and of the dead (cemeteries, catacombs, skulls), intermediate states of matter (mud, shadow) and duality (a cape, black on one side and red on the other, like the two-colored cap that Exu wears).

Exu also mediates between specific mythical and social universes, as a sort of “dual being” that contains within itself its own mediated parts. [Image at right] When manifest as Xoroque, Exu-Ogum, he is half St. George (white) and half demon (black, or mixed-race). It is as if St. George (who represents good) can’t be perceived as a separate entity from the dragon (the evil/devil) that he vanquished: just as the slave-master couldn’t have built his colonial world without slave labor. The second image of Exu Two Heads shows that gender identity is defined through contrast: men and women can’t be defined other than in relation to each another. And lastly, the third image, Xoroque-Indian Spirit-Exu, shows miscegenation as the driving force behind Brazilian society: a mixed-race or black person depicts an Indian wearing a head-dress while a white or black person’s skin is tinted “red,” reminiscent of both Exu and the devil.

It’s worth remembering that the concept of Two-Faced Exu is no stranger to African cosmology. One of the mythical characteristics of Exu is his double-face, which he uses to look ahead and to look back.

Furthermore, these “Demon-Exus” can do both good (solving health, legal, employment and amorous problems) and bad (causing  separations, leaving people destitute etc). They do what they are asked to do. As such, the Christian devil, from the perspective of Africa’s Exu, is seen less as absolute evil than as an angel before the fall from grace. In other words, Exu “is” not the devil, and the devil “is” not Exu; rather, both can establish relations with the other, expanding their original concept and generating new meanings. If, on the one hand, there has been a demonization of an African Exu, on the other, there has been an “Exuzation” of the biblical devil, pre-framing the Christian oversimplification of good and evil within African relativism.

separations, leaving people destitute etc). They do what they are asked to do. As such, the Christian devil, from the perspective of Africa’s Exu, is seen less as absolute evil than as an angel before the fall from grace. In other words, Exu “is” not the devil, and the devil “is” not Exu; rather, both can establish relations with the other, expanding their original concept and generating new meanings. If, on the one hand, there has been a demonization of an African Exu, on the other, there has been an “Exuzation” of the biblical devil, pre-framing the Christian oversimplification of good and evil within African relativism.

Traditional leaders within Candomblé, some committed to the “re-africanization”and/or “decatholicising” of the religion (Silva 1995), have criticized this “Catholic vision” of Exu and promoted a “recovery” or “neo-orishazation” of the African-Brazilian pantheon within its Yoruba-Fon background. Essential to this process is the availability in Brazil of images and texts relating to orisha worship in West Africa as well as exchanges between Brazilian, Cuban, and African priests. As a result of this, what was once almost impossible (initiation to Exu) is now more commonplace [Image at right] And with this resurgence it is now possible to see Exu descend on an initiate and wear the traditional conical hat, as well as strips of red and black cloth encrusted with cowries around the waist, while brandishing the  deity’s characteristic phallic staff; or even wearing rustic raffia clothing or luxurious white linen. [Image at right] Many of these clothes and insignia reproduce the outfits that African Exus wear and which have themselves become canonical images associated with orisha worship that are articulated with local religious practices in national and international context on both sides of the black Atlantic.

deity’s characteristic phallic staff; or even wearing rustic raffia clothing or luxurious white linen. [Image at right] Many of these clothes and insignia reproduce the outfits that African Exus wear and which have themselves become canonical images associated with orisha worship that are articulated with local religious practices in national and international context on both sides of the black Atlantic.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

In Brazil, Exu is worshipped at the entrance to temples at a collective shrine on the ground and in the open air, on which offerings are made. This is because no initiation can take place without singing his praise first and giving him his offering before all others. It is Exu’s job to protect temples against negative forces and to work in favor of the rituals that are about to take place in the temple that he watches over. His altars can take different shapes and express different concepts in accordance with the rite taking place.

In some temples, his altar is a ritually prepared mound of earth that grows in size in accordance with the volume of offerings it receives, which include animal blood, palm oil, foodstuffs and coins, etc. [Image at right] In other temples this altar may present anthropomorphic representations of Exu on whose phallus palm oil is poured.

In some temples, his altar is a ritually prepared mound of earth that grows in size in accordance with the volume of offerings it receives, which include animal blood, palm oil, foodstuffs and coins, etc. [Image at right] In other temples this altar may present anthropomorphic representations of Exu on whose phallus palm oil is poured.

As well as this collective shrine, Exu is also worshipped in individual shrines that are consecrated during a specific initiation and are kept inside a specific room set aside for Exu. Every initiate worships an individual Exu that protects him and helps maintain the dynamism and communication with his orisha.

The oldest images of Exu shrines date back at least to the 1930s, when the first ethnographic studies about the theme were published. Earlier descriptions focus on shrines made from a “cake” shaped with a mix of clay kneaded with the blood of birds, palm oil and an infusion of plants, giving rise to a head with eyes and a mouth made of cowries. These shrines gradually took on human shapes, and we can see the transformation of the phallic protuberance from Exu’s head into a pair of horns (as if the original phallus had been duplicated). This phallus can also be observed in Cuban heads made of sand and cement, where the Exus (that Cubans call Eleguás) exhibit a small, sharp knob (usually made with a nail) emanating from the forehead.

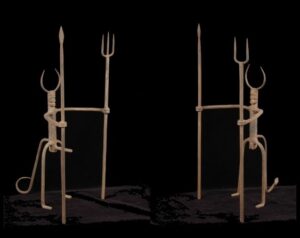

With the advent of wrought iron foundries, depictions of Exu with horns and a tale, holding a staff became extremely popular. In the image published in 1937, Exu’s sword has seven blades (signifying the seven paths) from which a handgun hangs. The presence of this firearm may indicate his role as a Keeper of order and of sacred spaces (a type of policeman) as well as a promoter of disorder, in tandem with life on the streets, with the criminal underworld, subversion and danger.

With the passage of time, Exu’s anthropomorphic body took on a cylindrical form, in a likely reference to the phallus and his staff, as well as a three-pronged fork (trident) for the male Exu, and two-pronged fork for the feminine version, called Pombagira. [Image at right] These statues proliferated in the temples and have become the best-known images of the deity, both inside and outside of temples.

For many, the fork is a direct echo of the diabolical trident. However, a horned-Exu was a common representation of the deity in West Africa, at least until the first half of the nineteenth Century (Maupoil 1943), being associated with power and fecundity. Statues of Exu with horns are also sold in Brazil by merchants from West Africa.

Not only is Exu worshipped in temples, but he is also worshipped in public spaces, such as in forests, cemeteries, stones, at crossroads, on the sand in beaches, at the foot of a tree, public markets, shop entrances etc, all of which are places of passage.

One of the places best known for Exu worship is set in the public area of Porto Alegre’s Municipal Market, in the state of Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil. [Image at right] Slaves built the market in the nineteenth Century, and, according to local legend, they buried a shrine to Bará (Exu) at the intersecting point between the market’s four paths. Nowadays it is where worshippers of African-Brazilian religions place coins in passing, as they visit the market to buy supplies and artifacts for their temples. It is also where neophytes are expected to go after their initiations to buy food from the sellers’ stands in order to ensure prosperity and abundance. According to myth, Exu eats everything that can fit in the mouth, which is why those who praise him will always have plenty to eat.

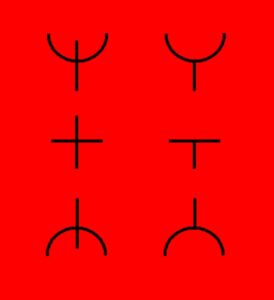

According to myth, Exu moves through time and space (towards the four cardinal points) with the aid of his staff. The crossroads, where all paths meet and cross, is one of his favored spaces, and it is where he receives most of his offerings. It is common in Umbanda temples to designate paths that meet in an “X” (4 points) to Exu, and those that meet in a “T” (three points) to Pombagira.

Pombagira is a female Exu charged with challenging the patriarchal order of Brazilian society through her refusal to accept a woman’s subordination to traditional domestic roles such as wife and mother. A “lady of the streets,” as opposed to a “home-builder,” she reflects the stereotype of the prostitute that eschews family, maternity, and marriage to affirm herself as a woman and express her femininity. She stresses anatomical differences (between a penis and a vagina) associated with biological sex (male and female) and gender roles (masculine and feminine) to question and invert, in a highly provocative and licentious way, (as if she were a “trickster in a skirt”) the social structure that perpetuates male-dominant relations.

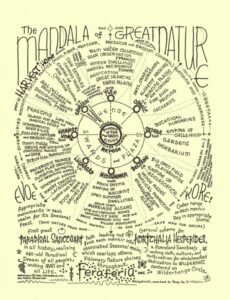

The mythical emphasis on the symbolism of the phallus and the vagina seems to have been re-elaborated in the various shapes of the trident and of the places where offerings are made, and which allude to the human body and its gender differences. I have chosen to depict these figures in abstract form, [Image at right] showing the forks (with two and three prongs) on the first line, and the crossroads (shaped like an “X” and a “T”) on the second line. Note that they are in alignment with variations of the male and female bodies in the third line.

Penis and horns, therefore, come to express not only Exu’s Catholic subjugation to the Devil, but the meeting point of these mythologies that use the language of body parts to produce myths that expose issues of power, the body, sexuality, and transformation.

The forks synthesize issues of transition, passage, and sexuality with such efficiency that they have become transnational symbols of the orishas and are also present in line drawings associated with the divinity.

These “drawn signs” are emblems elaborated by different Exus to identify themselves when they have taken possession of their initiates in Umbanda temples. Normally the Exus draw their signs and light candles over them to create a force field in which to carry out magical procedures.

The trident shape also supplies the standard for fabrication for Exu’s staffs, or tools. [Image at right]

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Among the symbols most celebrated by Brazilian culture, inside and outside the country, are samba, carnival, capoeira, Candomblé, a black bean stew called feijoada, caipirinha, mulatas and soccer. However, until the first decades of the twentieth century, samba was seen as lascivious, capoeira as a symbol of physical violence (expressive of “black criminal culture”) and Candomblé and Umbanda as witchcraft, charlatanism and “black magic.” Many of its practitioners were jailed. The black bean stew called feijoada, made up of cuts of meat rejected as not good enough for the slave-master’s table, was considered a “left-over.” The eventual acceptance of such ethnic symbols, with their black African roots, and their transformation into national symbols (glorified by the State and the people) underwent an array of conflicts and negotiations in various political, economic, and historical contexts. In terms of class, the sharing of these value systems between different ethnic groups was already prevalent in society, but it was only in the 1930s, during Getúlio Vargas’s presidency, when Rio de Janeiro was the country’s capital city, that many of these urban symbols were chosen and transformed to represent Brazil. During this period, the State transformed capoeira into a form of national gymnastics, sponsored carnival parades and elected samba the music of national integration. Outside Brazil, Carmem Miranda reinforced this image  by singing samba songs in traditional clothes from Bahia that have, at their core, references to Candomblé priestess’s dress.

by singing samba songs in traditional clothes from Bahia that have, at their core, references to Candomblé priestess’s dress.

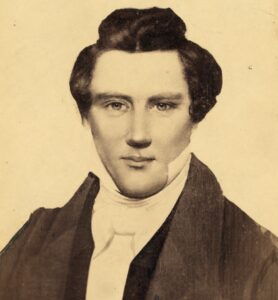

Walt Disney, when he was in Rio de Janeiro in the 1940s, was seduced by the images of a festive nation, given to the exotic and sensual, with its spicy food and vibrant colors. He created especially for Brazil, “José (Zé) Carioca,, a green and yellow parrot known for his cheery, gregarious nature, and laziness. [Image at right] In other words, an expert at the art of what Brazilians call the jeitinho, the “gift of gab,” along with a creative ability to survive without having to work, typifying the bon-vivant crooks of the era.

In Umbanda, the spirit of this crooked fellow (a Rio version of a bohemian dandy who walks the streets at night and is generally knifed to death or shot because of a woman or a gambling debt) is worshipped as Zé Pilintra. [Image at right] This spirit is considered by many an urban Exu, dwelling in ports and red-light districts, alongside his female counterpart, Pombagira. He wears a white suit with white shoes and a red tie and handkerchief folded into his breast pocket. His immaculate presentation is part of his ruse, as it conceals his impoverished and marginal condition, while drawing attention to a strict dress code that purposefully excludes itself from an already exclusive Brazilian social order. Zé Carioca is thus a comic personification of such a bohemian crook, common to the city of Rio and immortalized in spirit form in Umbanda.

Exu, due to his ambiguous nature, has served as a leimotiv for dilemmas facing Brazilian society, such as the incorporation of African values into society and the exclusion of blacks from society. In his classic novel Macunaíma (1922), author Mario de Andrade tells the story of a “characterless hero” who is born “the blackest dark-brown” to an Indian, and then becomes white. Macunaíma is the “African-Indigenous” trickster, an “Indian Exu.”

Jorge Amado, Brazil’s best-known author, chose the world of Candomblé as the source for many of his books, and elected Exu to guard over his oeuvre. A shrine for the deity stands at the front of the Fundação Casa de Jorge Amado, in Salvador’s Pelourinho district, on the same site where a sculpture of Exu by artist Tati Moreno stands.

Numerous artists have taken to depicting Exu in their sculptures, photographs, and prints. Many of these works are part of collections in museums, galleries and exhibited in public spaces.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Exu’s role as “anti-hero,” as the street spirit that undermines the established order, has made him the obvious choice for carnival’s Patron Saint. Indeed,  many carnival groups make offerings to him before they parade. And many of the larger carnival groups have created the habit of representing him in the front guard, a committee of dancers that open the parade and protect the parade as a unit. [Image at right]

many carnival groups make offerings to him before they parade. And many of the larger carnival groups have created the habit of representing him in the front guard, a committee of dancers that open the parade and protect the parade as a unit. [Image at right]

Exu is, therefore, the key to understanding this long-standing dialogue between African, American, and European cosmologies which have been merging ever since the sixteenth century. The demonization of Exu and the orishazation of the devil, or its mediations, express reciprocal readings of cultural universes that have come into contact.

Miscegenation does not only generate biological “hybrid” beings; it also generates cultural “hybrids.” Desire, repulsion, fascination with the exotic and fear of witchcraft are some of the feelings these “hybrid bodies” awaken in their dual capacity to perceive themselves on the margins of society (like Zé Pilintra and Pombagira) while recognizing themselves as agents of transformation, through a birth-right, or inherited ability to manipulate “sacred staffs.” Images of “half-and-half” beings, therefore, provide a metaphor of a society that perceives itself in light (and darkness) of a transatlantic trade in bodies and cultures that shaped a united and divided world, both unique and multi-faceted. It is through this capacity to interact and divide, to create consensus and disagreement, to merge opposites and split similars, to obey and subvert rules, that Exu, through his countless faces, exercises his power in Brazil.

IMAGES

Image #1: Beelzebub-Exu. Catalogue of the company “Gesso Bahia.” http://www.imagensbahia.com.br

Image #2: Cemetery-Exu. Catalogue of the company “Gesso Bahia.” http://www.imagensbahia.com.br

Image #3: Exu as Xoroque, Exu-Ogum, Exu Two Heads, and Xoroque-Indian Spirit-Exu.

Image #4: Initiation to Exu. Pai Leo’s Temple. São Paulo. Photo: Vagner Gonçalves da Silva, 2011.

Image #5: Exu, Pai Pérsio’s Temple, São Paulo. Photo: Roderick Steel.

Image #6: Shrine to Exu (barro) at the entrance to Mãe Sandra’s temple. The growth of its body due to the offerings represents its dynamic force. Photo: Vagner Gonçalves da Silva, São Paulo, 2011.

Image #7: Male and Female Exu. Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, University of São Paulo. Photo: Rita Amaral, 2001.

Image #8: Offerings to Exu (on the black cloth, right) and Pombagira (red cloth on the left). Access road to the Annual Umbanda Festival in Praia Grande, São Paulo. Photo: Vagner Gonçalves da Silva.

Image #9: Abstract presentation of the mythical emphasis on the symbolism of the phallus and the vagina.

Image #10: Ferramenta de Exu. Produtor: Santo Atelier. Foto: Fernanda Procópio e Luciano Alves. Coleção do autor.

Image#11: “José (Zé) Carioca,, a green and yellow parrot cartoon character created by Walt Disney.

Image #12: Mocidade Alegre carnival group’s Opening Committee, 2003. Photo: Vagner Gonçalves da Silva.

REFERENCES**

** Unless otherwise noted material in this profile is drawn from Silva, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2022).

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Amaral, Rita. 2001. “Coisas de Orixás – notas sobre o processo transformativo da cultura material dos cultos afro-brasileiros.” TAE – Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia – Revista inter e intradisciplinar de Ciências Sociais. Sociedade Portuguesa de Antropologia, 41:3-4.

Bastide, Roger. 1945. Imagens do Nordeste Místico em Branco e Preto. Rio de Janeiro: Edições O Cruzeiro.

Carneiro, Édison. 1937. Negros bantus. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

CARYBÉ (Iconografia dos Deuses Africanos no Candomblé da Bahia). 1980. Aquarelas de Carybé. Textos de Carybé, Jorge Amado, Pierre Verger e Waldeloir Rego, edição de Emanoel Araujo – Salvador, Editora Raízes Artes Gráficas, Fundação Cultural da Bahia, Instituto Nacional do Livro e Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Dopaumu, P. Ade. 1990. Exu. O inimigo invisível do homem. São Paulo, Editora Oduduwa.

Engler, Steven. 2012. “Umbanda and Africa.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 15:13-35.

Fernandes, Gonçalves. 1937. Xangôs do Nordeste. Rio de Janeiro. Civilização Brasileira.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. 1988. The Signifying Monkey. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mapoil, Bernard. 1988 [1943]. La géomancie à l`ancienne Cote dês Esclaves. Paris: Institut D´Ethnologie.

Ogundipe, Ayodele. 1978. Esu Elegbara. The Yoruba god of change and uncertainty. A study in Yoruba Mithology. Ph.D.Dissertation, Indiana University.

Pelton, Robert D. 1980. The trickster in West Africa. A study of mythic irony and sacred delight. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pemberton, John. 1975. Exu-Elegba: The Yoruba Trickster God. African Arts 9:20-27, 66-70, 90-92. Los Angeles: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center.

Ramos, Artur. 1940 [1934]. O negro brasileiro. São Paulo: Ed. Nacional.

Schmidet, Bettina E. and Steven Engler, eds. 2016. Handbook of Contemporary Religions in Brazil. Leiden: Brill.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2022. Exu, An Afro-Atlantic God in Brazil, São Paulo: Publisher of the University of São Paulo

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2015. Exu – O Guardião da Casa do Futuro. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Pallas.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2013. “Brazil’s Eshu: At the Crossroads of the Black Atlantic.” In Eshu: The Divine Trickster, edited by George Chemeche, New York: Antique Collectors’ Club.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2012. “Exu do Brasil: tropos de uma identidade afro-brasileira nos trópicos.” Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, DA-FFLCH-USP. 55:2.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2007. Neo-Pentecostalism and Afro-Brazilian religions: explaining the attacks on symbols of the African religious heritage in contemporary Brazil. Translated by David Allan Rodgers. Mana 3.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 2005. Candomblé e umbanda: Caminhos da devoção brasileira. São Paulo: Ática.

Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. 1995. Orixás da metrópole. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1993. Face of the Gods. Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas. New York. The Museum for African Art.

Thompson, Robert Farris. 1981. The four moments f the Sun. Kongo art in two worlds. Washington Nacional Gallery of Art.

Valente, Waldemar. 1955. Sincretismo Religioso Afro-Brasileiro. São Paulo: Editora Nacional.

Publication Date:

13 February 2022

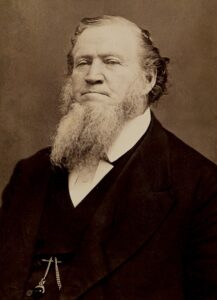

Jane Elizabeth Manning was born on a spring day in the early 1820s, most likely at her family’s home in Wilton, Connecticut. [Image at right] Her mother, Philes, was enslaved at birth, but had been free for at least a decade by the time of Jane’s birth. Philes’ mother, also called Philes, remained enslaved as she was too old to benefit from the gradual emancipation laws that the Connecticut legislature had passed in 1784. Little is known of Isaac Manning, Jane’s father, though a local historian claimed in the late 1930s that Manning had come from Newtown, Connecticut, about eighteen miles from Wilton. Isaac and Philes had at least five children together, including Jane, before Isaac died in about 1825.

Jane Elizabeth Manning was born on a spring day in the early 1820s, most likely at her family’s home in Wilton, Connecticut. [Image at right] Her mother, Philes, was enslaved at birth, but had been free for at least a decade by the time of Jane’s birth. Philes’ mother, also called Philes, remained enslaved as she was too old to benefit from the gradual emancipation laws that the Connecticut legislature had passed in 1784. Little is known of Isaac Manning, Jane’s father, though a local historian claimed in the late 1930s that Manning had come from Newtown, Connecticut, about eighteen miles from Wilton. Isaac and Philes had at least five children together, including Jane, before Isaac died in about 1825.

choose to do so. (Baptisms for living people are performed outside temples in natural bodies of water or in purpose-built baptismal fonts.) Before the first temple was completed in Utah, this ritual was performed on a regular basis in a building known as the Endowment House. [Image at right] In September 1875, Brigham Young directed that the Endowment House be made available for Black members to perform baptisms for the dead, which Jane and a group of others did with the help of a handful of White priesthood-holders. Jane was also baptized for several of her female relatives in the Logan, Utah Temple in 1888; and for a niece in the Salt Lake Temple in 1894.

choose to do so. (Baptisms for living people are performed outside temples in natural bodies of water or in purpose-built baptismal fonts.) Before the first temple was completed in Utah, this ritual was performed on a regular basis in a building known as the Endowment House. [Image at right] In September 1875, Brigham Young directed that the Endowment House be made available for Black members to perform baptisms for the dead, which Jane and a group of others did with the help of a handful of White priesthood-holders. Jane was also baptized for several of her female relatives in the Logan, Utah Temple in 1888; and for a niece in the Salt Lake Temple in 1894.

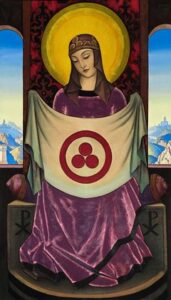

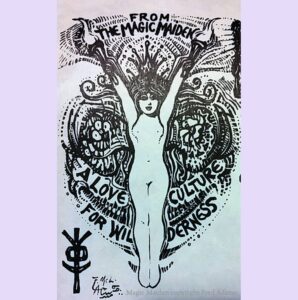

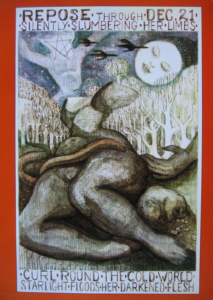

Northwest, centers around Persephone and Aidoneus (Hades). Repose, however, is devoted to Kore as Arretos Koura (“Nameless Maiden” [(Frederick Adams 1970)]), “the creatrix of universe and divinities” (Fred Adams n.d.) (Image at right). Though dyadic female-male pairs characterize the seasonal festivals, Feraferia envisions the feminine as the dominant face of the divine. The goddess’s name appears before the god’s in Feraferia’s descriptions of the festivals, and Repose, the core of the liturgical year, emphasizes the feminine divine almost exclusively. Fred’s 1956 epiphany of God as female remains persistent within the tradition. Fred’s interpretations of the nine festivals are memorialized visually in his published collection of paintings, Nine Royal Passions of the Year.

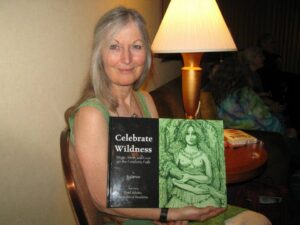

Northwest, centers around Persephone and Aidoneus (Hades). Repose, however, is devoted to Kore as Arretos Koura (“Nameless Maiden” [(Frederick Adams 1970)]), “the creatrix of universe and divinities” (Fred Adams n.d.) (Image at right). Though dyadic female-male pairs characterize the seasonal festivals, Feraferia envisions the feminine as the dominant face of the divine. The goddess’s name appears before the god’s in Feraferia’s descriptions of the festivals, and Repose, the core of the liturgical year, emphasizes the feminine divine almost exclusively. Fred’s 1956 epiphany of God as female remains persistent within the tradition. Fred’s interpretations of the nine festivals are memorialized visually in his published collection of paintings, Nine Royal Passions of the Year. workshops about Feraferia’s history and Feraferia rituals at PantheaCon frequently from around 2012. (PantheaCon announced 2020 as its final conference.) She [Image at right] and her husband John also manage a large website (feraferia website 2022) and a Feraferia Facebook Page, keeping community connected as well as reaching potential new members and initiates. Jo published Celebrate Wildness: Magic, Mirth and Love on the Feraferia Path in 2014, and she is currently working on creating The Tarot of Feraferia, based on Fred’s art and the Enneasphere, Feraferia’s “psycho-cosmic-tuning system.” Jo and others also see the continuation of Feraferia through their infusion of Feraferian ideas and techniques into other Pagan traditions that they practice.

workshops about Feraferia’s history and Feraferia rituals at PantheaCon frequently from around 2012. (PantheaCon announced 2020 as its final conference.) She [Image at right] and her husband John also manage a large website (feraferia website 2022) and a Feraferia Facebook Page, keeping community connected as well as reaching potential new members and initiates. Jo published Celebrate Wildness: Magic, Mirth and Love on the Feraferia Path in 2014, and she is currently working on creating The Tarot of Feraferia, based on Fred’s art and the Enneasphere, Feraferia’s “psycho-cosmic-tuning system.” Jo and others also see the continuation of Feraferia through their infusion of Feraferian ideas and techniques into other Pagan traditions that they practice.

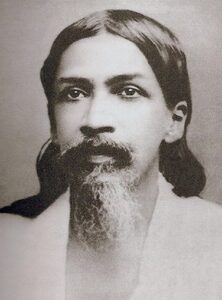

Yogananda replied, “I will never ask anything of you, that God does not tell me to ask.” That answer satisfied Walters, who henceforth became Yogananda’s disciple (Kriyananda 1977). [Image at right]

Yogananda replied, “I will never ask anything of you, that God does not tell me to ask.” That answer satisfied Walters, who henceforth became Yogananda’s disciple (Kriyananda 1977). [Image at right]

destroyed most of the homes and other buildings in 1976. Several families left as a result of the fire’s destruction (Helin 2021b). [Image at right]

destroyed most of the homes and other buildings in 1976. Several families left as a result of the fire’s destruction (Helin 2021b). [Image at right] longer periods. The Ananda website includes a brief free YouTube video modeling the practice and various support materials for purchase: an app with an audio guide, a longer DVD, and a booklet with illustrations drawn from those created by Yogananda (Neumann 2019).

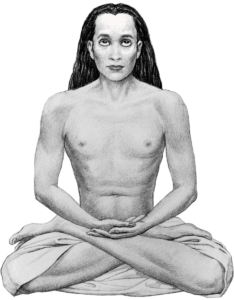

longer periods. The Ananda website includes a brief free YouTube video modeling the practice and various support materials for purchase: an app with an audio guide, a longer DVD, and a booklet with illustrations drawn from those created by Yogananda (Neumann 2019). result, people are better able to concentrate, are more successful in business, and “become better people in every way” (Ananda website n.d.). [Image at right]

result, people are better able to concentrate, are more successful in business, and “become better people in every way” (Ananda website n.d.). [Image at right]

The only offense detected was a minor tax violation (Beccaria 2006:134-135; Dimitri and Lai 2006:132). The acquittal was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in January 2000 (Beccaria 2006:162). In July 2004 the Court of Appeal in Bologna ordered a compensation of 100,000 Euros to Dimitri for having unjustly served thirteen months in jail (Beccaria 2006:165). [Image at right] Finally, in 1999 two additional sets of charges involving sexual violence were brought against Dimitri. Again, in both cases the testimonies were inconsistent, and the accusations were ruled to have no merit (Beccaria 2006:159-60).

The only offense detected was a minor tax violation (Beccaria 2006:134-135; Dimitri and Lai 2006:132). The acquittal was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in January 2000 (Beccaria 2006:162). In July 2004 the Court of Appeal in Bologna ordered a compensation of 100,000 Euros to Dimitri for having unjustly served thirteen months in jail (Beccaria 2006:165). [Image at right] Finally, in 1999 two additional sets of charges involving sexual violence were brought against Dimitri. Again, in both cases the testimonies were inconsistent, and the accusations were ruled to have no merit (Beccaria 2006:159-60).