PEOPLES TEMPLE AND JONESTOWN ENCLAVES TIMELINE

1927 (January 8): Marceline Mae Baldwin was born in Richmond, Indiana.

1931 (May 13): James Warren Jones was born in Crete, Indiana.

1949 (June 12): Marceline Baldwin married Jim Jones in Indianapolis, Indiana.

1954 (October) – 1955 (March): Jim Jones led services at Laurel Street Tabernacle, a Latter Rain Pentecostal church in Indianapolis.

1955 (April 2): The first announcement was made of a Peoples Temple meeting at 1502 N. New Jersey, Indianapolis, a building purchased by Jim Jones, Marceline Jones, and Lynetta Jones through the Wings of Deliverance corporation.

1957 (December 18): The Peoples Temple congregation moved to a synagogue building at 975 N. Delaware, Indianapolis. This was larger than the facility at 15th and New Jersey.

1962 (February): Jim and Marceline Jones moved to Belo Horizonte, Brazil with their five youngest children. They also visited British Guiana (pre-Independence name) that year.

1963: The Jones family moved to Rio de Janeiro

1963 (December): The Jones family returned to Indianapolis.

1965 (Summer): The Jones family and 140 Indianapolis Temple members relocated to Redwood Valley, in the northern California wine country.

1969: Construction of the Peoples Temple church facility in Redwood Valley was completed by volunteers.

1969: Temple members held their first worship service at Benjamin Franklin Junior High School in San Francisco.

1971 (February): Temple members held their first service at Embassy Auditorium in Los Angeles.

1972 (April): Peoples Temple bought Happy Acres in Redwood Valley, a ranch and residential facility for mentally challenged young adults.

1972 (September 3–4): Peoples Temple church at 1366 S. Alvarado Street in Los Angeles was dedicated and blessed. The building was purchased that year.

1972 (December): Peoples Temple bought a former Scottish Rite temple at 1859 Geary Street, in the largely African American Fillmore District of San Francisco, and began weekly worship services there.

1973 (October 8): The Peoples Temple Board of Directors adopted a resolution to establish a “branch church and agricultural mission” in Guyana.

1973 (December): Peoples Temple members met with officials from the Government of Guyana to lease acreage for an agricultural project.

1974 (June): The first pioneers went to Matthews Ridge, Guyana to begin construction on what would become Jonestown.

1976 (February 25): The Government of Guyana and Peoples Temple signed lease for 3,852 acres in the Northwest District of Guyana, a territory disputed by Venezuela.

1976 (December 31): Peoples Temple headquarters moved from Redwood Valley to San Francisco.

1977 (Spring): An oppositional group called Concerned Relatives formed to rescue friends and family from Peoples Temple by enlisting the aid of reporters and government officials.

1977 (Summer): A tax audit by the Internal Revenue Service along with an exposé by New West Magazine prompted mass migration of more than 700 Temple members to Guyana.

1978 (Summer): Residents of Jonestown studied the Russian language and political science in the hope of moving to the Soviet Union. Temple leaders in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital city, made frequent visits to the embassies of Communist countries, including Hungary, North Korea, Cuba, and the Soviet Union.

1978 (October): The Soviet attaché to Guyana, Feodor Timofeyev, visited Jonestown.

1978 (November 17–18): U.S. Congressman Leo J. Ryan visited Jonestown with reporters and members of the Concerned Relatives.

1978 (November 18): Gunmen from Jonestown shot and killed Congressman Ryan and four others at the Port Kaituma airstrip, six miles from Jonestown. Residents of Jonestown murdered their children and then either were murdered or committed suicide themselves.

1978 (November 23–27): 918 Jonestown bodies were repatriated to the United States by the U.S. Air Force.

1979 (May): 408 unclaimed and unidentified bodies from Jonestown were buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California.

2011 (May 29): A memorial to Jonestown dead was dedicated at Evergreen Cemetery.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

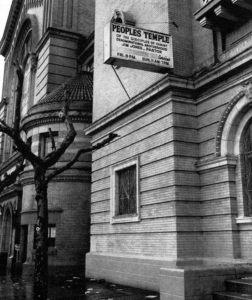

Evolving residential patterns (individual, enclave, communal) marked the institutional organization of Peoples Temple over its twenty-five year history. The movement began in the 1950s as a Pentecostal church in the American Midwest, where members promoted racial equality in the highly segregated neighborhoods of Indianapolis. It migrated to rural northern California in the 1960s where it began to function as an economic and residential enclave, before expanding to the urban cores of San Francisco [Image at right] and Los Angeles. It terminated as a communal experiment in the jungles of Guyana in South America in the 1970s. These different locations enabled the group to change its ideology, program, and practices over time, moving from a fundamentalist Christian orientation to a Social Gospel-style message, and finally, a militant form of Marxist socialism. As Hall notes, “Despite the collapse in apparently irrational murder and mass suicide, Peoples Temple developed innovative forms of social organization based on its economic organization” (Hall 1988:65S).

Peoples Temple was founded in Indianapolis by Jim Jones, his wife Marceline Mae Baldwin, and his mother Lynetta Jones in 1955, when they incorporated as Wings of Deliverance. Jim Jones played an active role in the “Healing Revival” movement of the 1950s (Collins 2019). Even before founding his own church, he was a popular evangelist on the revival circuit, and briefly led the congregation at Laurel Tabernacle in Indianapolis, a church in the Latter Rain tradition of Pentecostalism.

A number of White members of Laurel Tabernacle followed Jones to the newly-established Peoples Temple in 1955. A racially mixed congregation met at a church at the corner of 15th Street and New Jersey Avenue, which was purchased by Wings of Deliverance. [Image at right] Advertisements in local newspapers proclaimed the Temple’s commitment to brotherhood and equality. In 1957 the congregation moved to a larger building, a former synagogue at 975 N. Delaware, also purchased by the corporation. Marceline Jones, a registered nurse, successfully opened several nursing homes, which helped to support the family of five (adopted daughter Stephanie dies in a car accident). The homes also provided housing for elderly church members and jobs for capable ones. The Temple acquired additional nursing homes, which were managed by Marceline’s father Walter Baldwin. Most of the congregation lived in either owner-occupied or rental housing, and had employment outside and apart from the Temple. Given the segregated neighborhoods in Indianapolis at the time, Whites resided apart from Blacks. At that point in its existence, Peoples Temple operated as a traditional church.

Reputedly prompted by an article in Esquire Magazine, which identified Belo Horizonte, Brazil as one of the safest places to live in case of nuclear attack, Jones moved his family to Brazil in 1961. Given the subsequent history of the Temple and its geographic instability, however, Jones was probably scouting a location for a future Temple abroad, since his itinerary included British Guiana (the country’s name before independence in 1966). The family returned to Indianapolis in late 1963, where they found a greatly reduced Peoples Temple congregation.

A few families relocated to northern California and encouraged Jones to move the Temple there. In 1965, an integrated caravan of 140 people made the journey and settled in Redwood Valley, a rural enclave located about 115 miles north of San Francisco on Highway 101. “Jones chose an ideal area for building a closed community,” according to Tim Reiterman (Reiterman with Jacobs 1982:102). The migrants lived scattered throughout the valley, which had vineyards, orchards, and a lumber mill. Initially they convened jointly with members of Christ’s Church of the Golden Rule in nearby Willits, until there was a falling out. They met for a time in a garage, before a new church building opened in 1969, constructed with volunteer labor.

At first, individual members scraped together whatever jobs they could find: working in the local Masonite factory, serving as school teachers and health aids, or becoming part of the social services system in Mendocino County. The church raised money through petty revenue-generating ventures: a food truck, bake sales, clothing drives, offerings. But when the Temple began to buy property in the area, such as a small shopping center with Temple offices upstairs and a laundromat and small businesses on the ground floor, a more cohesive enclave developed. The center of action was the church complex, with members living within a few miles of the hub. Communal living commenced, but only on a small scale, with members simply sharing housing with each other or taking in children under guardianships and foster care.

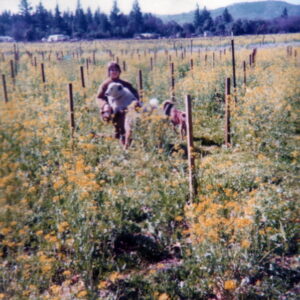

At this same time, a “home care care franchise system” started, according to Hall. “Dealing with the clients of the welfare state became a central business of Peoples Temple” (Hall 1988:67S). In 1972, the Temple acquired Happy Acres, a ranch and residential facility for mentally challenged young adults. [Image at right] Marceline Jones and others worked in the area’s health and welfare systems; eventually Temple members purchased houses they converted into care facilities to shelter the elderly, disabled, and mentally challenged. While at least nine such homes were officially licensed, additional Temple accommodations undoubtedly housed people under informal church auspices.

While members tended to keep to themselves, leaders adopted a more visible profile. Jim Jones served as Chair of the Mendocino County Grand Jury, while Temple attorney Tim Stoen was a deputy district attorney for the county. According to an exposé written in 1977, Jones became “a political force” in the county, able to control about 16 percent of the vote. One county supervisor claimed that “I could show anybody the tallies by precinct and pick out the Jones vote” (Kilduff and Tracy 1977). In short, Redwood Valley presents a type of enclave in which Peoples Temple drew boundaries against the wider community, but, at the same time, attempted to influence that community.

Nevertheless, Temple members found it difficult living in largely White Redwood Valley. African American members stood out. Racial incidents occurred in schools and in the Masonite factory. They therefore began to missionize in San Francisco and in 1969 held their first worship service at Benjamin Franklin Junior High School, 1430 Scott Street in the predominantly African American Fillmore District of the city. They conduct their first service in Los Angeles in 1971 at the Embassy Auditorium, the corner of 9th and Grand.

These forays into urban areas, populated with large numbers of African Americans and progressive White liberals, persuaded the leadership to purchase church buildings in Los Angeles [Image at right] and San Francisco.While the LA Temple provided large financial support through offerings from its members, the SF Temple served as the locus for developing a political presence in city and county government. Communal living intensified, with close to 400 individuals living in 32 different residences in San Francisco (Moore 2022). These were generally apartments, some of which the Temple owned, and some owned by Temple members. In addition, at least one hundred members in the Bay Area “go communal,” which meant they donated their paycheck, if they worked outside jobs, or worked for the Temple itself. Either way, room, board, and expenses comprised their remuneration.

Despite living in close proximity to each other in San Francisco (though much less so in Los Angeles, despite the purchase of the Terrace Apartments located directly next to the church), Temple members had difficulty developing an enclave in these large and diffuse urban areas. Indeed, being in the Fillmore District of San Francisco brought the congregation into more contact, rather than less, with other progressives committed to the cause of racial justice. They thus found themselves part of a larger enclave (or ghetto) of African Americans living in the Fillmore. The Temple tried to get redevelopment grants to acquire properties near its main building on Geary Boulevard, but the project, “which may have been an attempt to create a ‘mission’ in San Francisco to house all the members in one place,” was abandoned (Hollis 2004:90). Nevertheless, the Temple established its own welfare system for members, taking the form of a bureaucracy “loosely coupled to a wide range of social service organizations” (Hall 2004:94). This explains its popularity with those accessing its services as well as its unpopularity with competing public and nonprofit agencies.

The repressive political situation in the United States ostensibly prompted the Temple Board of Directors in October 1973 to decide to launch a branch church and agricultural project in Guyana. The inability to create a true enclave in either rural or urban areas, however, may have been yet another reason for looking abroad. Mass emigration was a complicated process (Shearer 2018), especially the acquisition of land, a place to settle. In 1973 the government of Guyana proposed a 20,000 to 25,000-acre leasehold to Temple negotiators. A lease for 3,852 acres, with 3,000 acres to be cultivated, was eventually signed in 1976 (Beck 2020). During the intervening years, a group of Temple pioneers began clearing the jungle in the Northwest District of Guyana, an area located near a contested border with Venezuela.

The agricultural project, eventually named Jonestown, was constructed from the ground up, and was designed to model socialist organization. [Image at right] It was hardly an enclave, given its geographical isolation, but rather a utopian communal experiment. Its dependence on the goodwill of Guyana officials, coupled with its need to retain friendly relations with U.S. Embassy officials, created a sense of vulnerability among the residents, despite their distance from day-to-day oversight.

Early settlers expressed satisfaction with their work, and enthusiastic hope pervaded the encampment (Blakey 2018). The Jonestown pioneers cleared the land for cultivating crops, constructed barns and outbuildings for livestock, and erected central service structures, including a laundry, kitchen, school, community center, library, workshops, garage, health clinic, and most importantly, housing. Infrastructure projects, such as water, electricity, sanitation, roads and walkways, dominated the thoughts of those involved in construction. Jonestown, therefore, was an independent village with a socialist, or communal, economy that would eventually grow to a thousand people escaping the “Babylon” of the United States.

Despite these impressive efforts, the settlement was not ready to meet the needs of 700 new arrivals in 1977. That year also marked the arrival of Jim Jones, whose drug addiction and megalomania seemed to interfere with the smooth operation of the community. Overcrowding compounded problems not yet resolved by the early settlers. Yet Jonestown was truly communal: no one was paid a wage for their labor, but no one paid anything for food, housing, clothing, medicine, and so on. Panic over an invasion by real and imagined enemies replaced ordinary anxieties about paying the rent or putting food on the table. An oppositional group called the Concerned Relatives, who feared for the safety of family members in Jonestown, encouraged journalists and government officials to mount investigations into conditions at the agricultural project. This in turn heightened Jonestown residents’ apprehension about conspiracies against the group. Security tightened in the community, dissidents were silenced or punished, and residents practiced suicide drills to prepare them for the inevitable deaths they believed they would face when an invasion came.

At the same time, however, residents prepared for yet another migration, this one to the Soviet Union. They practiced Russian language, studied international politics, and talked with Soviet visitors to the project. As early as March 1978, residents stated that the Soviet Union was its spiritual home (“Temple Declares Soviet Union is its Motherland” 1978). In October, Temple representatives met on an almost daily basis with a Soviet Embassy official regarding both visiting and immigrating to the U.S.S.R. (“Peoples Temple Meetings with the Soviet Embassy” 1978). That same month, three Jonestown leaders compiled a list of possible places to move in the Soviet Union that weren’t too cold, given the fact that the majority of Jonestown residents were comfortable in the tropical climate of Guyana (Chaikin, Grubbs, and Tropp 1978). They speculated that the Soviets would prefer to locate the group in an unpopulated area, however, which meant a colder, more forbidding climate. Finally, during the last hours of life in Jonestown, one resident asked the assembly if it was too late for Russia, in the full expectation that the group was planning to move there (FBI Audiotape Q042 1978).

On November 1, Leo J. Ryan, a Congressman from the San Francisco Peninsula, informed Jim Jones that he planned to visit Jonestown. On November 5, the residents told the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown that Ryan was not welcome. State Department officials both in Washington, D.C. and in Guyana repeatedly warned Ryan that he had no authority as a U.S. government legislator, and that as a private citizen he had no special rights in Guyana. The people in Jonestown were not obligated to open their community to him. Yet, at the urging of Marceline Jones, the group allowed Ryan and his small entourage of reporters and relatives, to come into Jonestown on November 17. The party returned the next day, where they received a cool welcome. About fifteen people said they want to leave with the congressman. They departed shortly after Ryan scuffled with a knife-wielding attacker. Gunmen from the community killed the congressman and four others at a jungle airstrip in Port Kaituma, six miles away from Jonestown. Nine others were wounded, some quite seriously. Back in Jonestown, a vat of cyanide-laced fruit drink was brought out. Jones exhorted the residents to take the poison calmly while children were dosed by parents and medical staff. And, just as they had lived together in Jonestown, the residents died together.

The U.S. Army Graves Registration team recovered the bodies, which were airlifted to Dover Air Force Base. There the unclaimed and unidentified languished for six months, until a group of interfaith leaders in San Francisco obtained funding from the Peoples Temple Receiver to transport the bodies to California. They had a difficult time finding a cemetery willing to bury the 408 bodies. Evergreen Cemetery, in Oakland, California agreed to excavate a hillside, [Image at right] and stacked the coffins into a mass grave before recontouring the hill. In 2011, after many delays, four granite plaques were inlaid on the hillside, listing the names of all who died on November 18, 1978. The journey of Peoples Temple members was finally over.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Just as each location dictated the ways in which Peoples Temple members lived, so too each site shaped beliefs and teachings (Moore 2022). In Indianapolis, the Temple began as a Pentecostal church, emphasizing the gifts of prophecy, healing, and speaking tongues. The church also expressed a clear commitment to integration in all its publicity. An ad from 1956 bore the headline: “Peoples Temple. Interracial-Interdenominational.” To make sure the message was clear, the tag line at the bottom stated: “We Teach and Practice complete integration in the family, church and vocational fields” (“Peoples Temple Ad” 1956). Indianapolis in the 1950s had a relatively large population of African Americans due to the Great Migration of the early twentieth century and the post-war economic boom after 1945 (Thornbrough 2000). Both de facto and de jure segregation existed in the capital city, however, and housing stock was low for many African Americans, even those with middle class status and income. Peoples Temple concentrated on programs in the tradition of the Christian Social Gospel: integration of neighborhoods and businesses, including restaurants, barber shops, and hospitals. In addition, human service programs such as a food pantry and free restaurant met the needs of poor people. The focus was strictly local.

With the move to California, the Christian aspects of the Temple seemed to mask a socialist ideology. In sermons from Redwood Valley, Jones declared that “Socialism is God,” that is, perfect love. In San Francisco, members and pastor adopted a more militant and public position regarding social issues. Under the guise of liberal Protestantism, Peoples Temple supported many worthy causes: from protesting the eviction of low income tenants, to picketing for freedom of the press. Jones and his leadership team courted Democratic politicians and played a significant role in the close mayoral election of 1975. It was not that the Temple had that many voters, but rather its ability to produce votes (by leafletting neighborhoods, transporting voters to the polls, hosting rallies, and showing up at campaign events) that made it important in party politics.

The Temple also began to adopt an internationalist perspective in Los Angeles and San Francisco. It hosted speakers from African nations seeking liberation, Chilean refugees from the 1974 coup, and radicals like Communist Party member and professor Angela Davis and American Indian Movement leader Dennis Banks. The Temple co-sponsored an event in Los Angeles with the Nation of Islam, at which W. Deen Mohammed spoke.

The internationalization process was complete with the move to the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, which had a mixed economy but was turning toward socialism in the 1970s. Temple leaders meeting with Guyanese officials explicitly stated their support of socialism. They removed religious symbolism from the Temple letterhead for documents going to Communist countries. Planning meetings for community development—health, agriculture, manufacturing—replaced religious services in Jonestown. In what may be a revisionist autobiography, Jim Jones declared that he had always been a Communist, and asserted that he was an atheist as well. By the end, atheistic humanism seemed to be the dominant ideology in the community.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

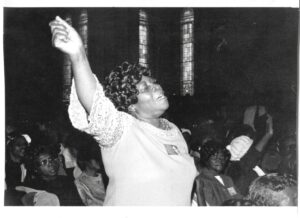

During the 1950s and 1960s, Peoples Temple functioned in all respects as an independent church that followed “the model of the emotionally expressive Pentecostal tradition” (Harrison 2004:129). [Image at right] Although Jim Jones was White, he adopted a Spirit-filled worship style that appealed to African Americans and working class Whites. Following the revivalist model, services included music, multiple appeals for money, a call-and-response style of sermonizing, and (what everyone waited for) healings.

Jones retained the Pentecostal style in California, even as the internal doctrine was shifting from the Christian God to Divine Socialism. Healings remained part of the ministry, but they had become sacred theater in which assistants provided “proof” that cancers had been excreted or vomited by those being healed. The healings were necessary, argued members, in order to attract followers and to demonstrate the truth of the message. In Jonestown, however, healings disappeared, although members in the United States were told that Jones restored a severed hand to someone who supposedly lost it in a construction accident.

The practice of public confession started in Indianapolis, but became “Deeper Life Catharsis” in Redwood Valley. Writing in 1970, Patricia Cartmell described the process. “Each member of the body was encouraged to stand and get off his chest everything that was in any way a hindrance to fellowship between himself and another member or between himself and the group, or the leader even” (Cartmell 2005:23). Some confessions seem honest, like reading the newspaper during worship or stealing a pack of gum. Other confessions, which occurred with eerie and increasing regularity, included admissions of being a child molester, desiring Jim Jones sexually, and having homosexual impulses.

Catharsis became more abusive among leaders of the elite Planning Commission in San Francisco. There the group took turns excoriating an individual who was “on the floor,” meaning the one who was targeted for criticism that evening. Members found fault with every little thing (clothing, speech, attitude, appearance) and stripped bare (sometimes literally) the person under the microscope.

A time for praise and punishment occurred on a weekly basis among the most committed church members in Redwood Valley and San Francisco. Children, as well as adults, were brought on the floor for offenses like discourtesy, sexism, bullying, lying, stealing, skipping school, and irresponsibility. Punishments might be the assignment of chores, such as soliciting donations to the Temple on street corners; paddlings with a board; beatings; and boxing matches. With the congregation’s approval, for instance, three women hit a young man because he was two-timing his girlfriend, and slap his new partner for helping the original girlfriend get an abortion (Roller 1976).

Praise and punishment continued in Jonestown. The entire community participated. Children, adults, and seniors were rewarded with words of praise or special privileges; they were punished with the assignment of extra chores on the Learning Crew. Those who were particularly obstinate or disobedient might be sentenced to “the box,” a small isolation container in which the miscreant was sent for a day or two (on at least one occasion, a week) of solitary confinement. The box was not introduced until February 1978. The most recalcitrant dissidents or troublemakers might end up in the Extended Care Unit, where they received heavy doses of tranquilizers. It appears that only a handful received this treatment.

A final ritual of note was the suicide rehearsal. Sometimes called White Nights (which were frequent civil defense alerts) suicide drills seemed to have occurred about six times in Jonestown. A number of individuals declared their willingness to die at these ritualistically organized community meetings. More significantly, they expressed their desire to ensure that the children are not tortured, and thus parents stated their commitment to “take care of the children” by killing them first. Those assembled then lined up and took what was purportedly poison. Thus, the rhetoric of sacrificial death was rehearsed, and on Jonestown’s final day, people knew what to say and what to do.

ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Peoples Temple was hierarchically structured, and can be characterized as either a social pyramid (Moore 2018) or a series of concentric circles (Hall 2004). Jim Jones was the top, or central, figure surrounded by a cadre of mostly White women, who carried out his orders. The further from Jones, the less responsibility a member had. On the bottom, or periphery, were the rank-and-file, who knew little about the inner decision-making process.

In Jonestown, a level of middle managers, called Assistant Chief Administrative Officers (ACAOs) oversaw daily operations. They administered food procurement, preparation, service, and clean-up. Other managers oversaw various agricultural departments that handled livestock, insecticides, irrigation, tools and equipment, seeds, and much more. The ACAOs kept a sharp eye on the workers, and reported good and bad attitudes at the weekly Peoples Rallies and Forum, the body that governed Jonestown comprised of all residents, including children. Jim Jones remained at the top of the organizational chart, however, and ultimately made all decisions, regardless of what the people decided.

Given their “geographic” location in the hierarchy, surviving Temple members had very different accounts of their experiences in the group. The closer to Jones, the more abuse a member received, especially sexual abuse, at least in the United States. In Jonestown, however, where the community was small enough that everyone participated, physical and emotional abuse were routinely dispensed to anyone called up on the floor.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Two key issues remain to challenge our understanding Jonestown. The first is that of race in the Temple, a topic generally neglected until the twenty-first century. A White preacher, who relied on a White cohort of associates, led a predominantly Black congregation to their deaths. The irony of the Temple’s commitment to racial equality in light of this is overwhelming. In the aftermath, the racial imbalance continues, with White apostates dominating media coverage. The absence of Black voices, let alone those of the citizens of Guyana, means that the story of Jonestown and Peoples Temple is incomplete.

This imbalance is slowly being corrected with the publication of memoirs (Wagner-Wilson 2008; Smith 2021), literary works (Gillespie 2011; Hutchinson 2015; scott 2022), religious and political analyses (Moore, Pinn, and Sawyer 2004; Kwayana 2016), and interviews of Guyanese eyewitnesses (Johnson 2019; James 2020). Given the fact that seventy percent of those who died in Jonestown were African American, and forty-six percent of those who lived in Jonestown were Black females, more scholarly investigation is needed.

The second challenge concerns the geographical isolation of Jonestown, perhaps the most important factor contributing to the tragedy. The village of Port Kaituma was six miles away from Jonestown, but the capital city of Georgetown (home to Guyanese officials and American Embassy personnel) was 125 miles away, with nothing but jungle in between. [Image at right] Those emigrating from California took a twenty-four hour journey by boat along the north coast of Guyana and up the Kaituma River. The Temple did maintain a house in Georgetown in a neighborhood called Lamaha Gardens, where members stayed when they first arrived, when they needed medical appointments, or when special events were planned. A few people lived there more or less permanently, and maintained frequent contact with government officials.

Jonestown was thus an independent, self-contained communal enterprise, rather than an enclave. Its residents were responsible for the survival not only of themselves and their families, but for the entire community. Guyana was a hospitable place for the community: the national language is English, people of color, especially of African descent, make up the population, and though life is difficult it is sunny and warm, both in climate and temperament. With Jonestown’s survival imperiled by the Concerned Relatives, however, residents looked to the Soviet Union as a place where they might live out their socialist ideals in peace. A move to Russia, though (with its foreign language, its White demographic majority, and its harsh climate) would mean a return to enclave status as a minority group.

The remoteness of Jonestown seems to indicate that group encapsulation might play a very significant role in predicting religious violence (see e.g., the summary in Dawson 1998:148–52). As long as members of Peoples Temple could physically walk away from the group, and retained the possibility of direct contact with friends, relatives, law enforcement officials, and others (as they would in the United States), the ultimate catastrophe remained out of reach. Abuses occurred, but there were limits due to the proximity of neighbors. The move to Redwood Valley allowed Jones and the leadership cadre to begin a process of self-isolation, living as an enclave in a rural area. Enclave status was undermined in San Francisco and Los Angeles, however, where Peoples Temple was just one more religious group within the larger enclave of African American urbanites. Moreover, members were in contact with outsiders on a daily basis. With the migration to the jungles of South America, and the establishment of a utopian, socialist commune, complete geographical isolation was possible. When that seclusion was violated, tragedy followed.

IMAGES

Image # 1: Peoples Temple building at 1859 Geary Boulevard in San Francisco in the 1970s. The building was destroyed in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Image # 2: Peoples Temple’s first church building, located at 1502 N. New Jersey Street, Indianapolis. Photo taken in 2012.

Image # 3: Happy Acres, a ranch purchased in Redwood Valley by Peoples Temple in 1972. Claire Janaro shown in overgrown vineyard, 1975.

Image # 4: Los Angeles branch of Peoples Temple at 1366 S. Alvarado Street. The church currently houses a Latino Seventh-day Adventist congregation. Photo taken in twenty-first century.

Image # 5: Lester Matheson and David Betts (Pop) Jackson pose in front of road recently carved out of the jungle, 1974.

Image # 6: Monument at Evergreen Cemetery, Oakland, California listing names of all who died on November 18, 1978. The plaques were installed in 2011, and the site was refurbished in 2018, when photo was taken.

Image # 7: Spirit-filled woman at the Los Angeles temple, date unknown.

Image # 8: Aerial view of part of Jonestown, showing extent of construction and cultivation completed by 1978.

REFERENCES

Beck, Don. 2020. “Maps of Proposed Leasehold.” Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=94022 on 15 January 2022.

Blakey, Phil. 2018. “Snapshots from a Jonestown Life.” the jonestown report 20 (October). Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=81310 on 15 January 2022.

Cartmell, Patricia. 2005. “No Haloes Please.” Pp. 23-24 in Dear People: Remembering Jonestown, edited by Denice Stephenson. San Francisco: California Historical Society Press and Berkeley: Heyday Books.

Chaikin, Eugene, Tom Grubbs, and Richard Tropp. 1978. “Possible Resettlement Locations in USSR.” Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13123 on 15 January 2022.

Collins, John. 2019. “The ‘Full Gospel’ Origins of Peoples Temple.” the jonestown report 21 (October). Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=92702 on 15 January 2022.

Dawson, Lorne L. 1998. Comprehending Cults: The Sociology of New Religious Movements. New York: Oxford University Press.

FBI Audiotape Q042. 1978. Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29079 on 15 January 2022.

Gillespie, Carmen. 2011. Jonestown: A Vexation. Detroit, MI: Lotus Press.

Hall, John R. 1988. “Collective Welfare as Resource Mobilization in Peoples Temple: A Case Study of a Poor People’s Religious Social Movement.” Sociological Analysis 49 Supplement (December): 64S–77S.

Hall, John R. 2004. Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Harrison, Milmon F. 2004. “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions.” Pp. 123-38 in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hollis, Tanya M. 2004. “Peoples Temple and Housing Politics in San Francisco.” Pp. 81-102 in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hutchinson, Sikivu. 2015. White Nights, Black Paradise. Los Angeles, CA: Infidel Books.

James, Clifton. 2020. “Interview with Preston Jones.” Military Response to Jonestown, Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BCPAeyIhgFo on 15 January 2022.

Johnson, Major Randy. 2019. “Interview with Preston Jones.” Military Responses to Jonestown, Accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9zKk3RhFGc on 15 January 2022.

Kilduff, Marshall and Phil Tracy. 1977. “Inside Peoples Temple.” New West Magazine. Available on Alternative Considerations. https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14025.

Kwayana, Eusi, ed. 2016. A New Look at Jonestown: Dimensions from a Guyanese Perspective. Los Angeles: Carib House.

Moore, Rebecca. 2022. Peoples Temple and Jonestown in the Twenty-first Century. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger Publisher.

Moore, Rebecca, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary R. Sawyer, eds. 2004. Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

“Peoples Temple Ad.” 1956. The Indianapolis Recorder, June 2. Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/47337437072/in/album-72157706000175671/ on 15 January 2022.

“Peoples Temple Meetings with the Soviet Embassy.” 1978. Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=112381 on 15 January 2022.

Reiterman, Tim, with John Jacobs. 1982. Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Roller, Edith. 1976. “Edith Roller Journals,” December. Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35685 on 15 January 2022.

scott, darlene anita. 2022. Marrow. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Shearer, Heather. 2018. “‘Verbal Orders Don’t Go—Write It!’: Building and Maintaining the Promised Land.” Nova Religio 22:65–92.

Smith, Eugene. 2021. Back to the World: A Life After Jonestown. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University.

“Temple Declares Soviet Union is its Motherland.” 1978. Alternative Considerations. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=112395 on 15 January 2022.

Thornbrough, Emma Lou. 2000. Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century. Edited and with a final chapter by Lana Ruegamer. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Wagner-Wilson, Leslie. 2008. Slavery of Faith. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

The Alternative Considerations of Peoples Temple and Jonestown (shortened to Alternative Considerations), contains a wealth of primary source documents, digitized audiotapes and transcripts, and articles and analyses at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/.

The Peoples Temple/Jonestown Gallery on Flickr houses hundreds of photographs, many available in the public domain, at https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/albums.

Aerial views of Jonestown, from 1974 to 1978, are available at https://www.flickr.com/photos/peoplestemple/albums/72157714106792153/with/4732670705/.

Maps and schematics of Jonestown are available at https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35892.

Publication Date:

18 January 2022