AUROVILLE TIMELINE

1872: Aurobindo was born in Calcutta (Kolkata), India.

1878: Mirra Alfassa’s was born in Paris, France.

1910: Aurobindo was exiled to Pondicherry, France.

1920: Mirra Alfassa settled in Pondicherry.

1947: India achieved independence.

1950: Sri Aurobindo died.

1954: Pondicherry was returned to India by France.

1961: The Sri Aurobindo Society (S.A.S) was founded to finance the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and Auroville.

1966: The organizing concept of Auroville was adopted by UNESCO.

1968: Auroville was founded; its charter was adopted on February 28.

1968: The reforestation of Auroville’s land began.

1970: Auroville received a new endorsement from UNESCO.

1972: Construction of the Matrimandir began.

1973: Mirra Alfassa, the Mother, died.

1973-1980: Auroville’s succession war took place.

1976: Eight Aurovilians were temporarily imprisoned after a complaint by the SriAurobindo Society.

1976: The Court of Justice of Calcutta removed S.A.S.’s financial control of Auroville.

1978-1982: The Mother’s Agenda was published.

1980: The Indian State assumed full control of Auroville.

1983: Auroville received a new endorsement from UNESCO.

1988: Auroville was institutionalized as a trust under the supervision of the Indian State.

1989: The “Auroville Act” was passed unanimously by the Indian Parliament.

2008: Construction on the Matrimandir building was completed.

2012: The Auroville Sadhana Forest Project received the Humanitarian Water and Food Award in Copenhagen, Denmark.

2016: The Auroville Earth Institute received 1st International COP22 Low Carbon Award.

2018: The Auroville Golden Jubilee was held; Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Auroville.

2020: A lockdown was put in place in response to the Covid19 pandemic.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Mirra Alfassa was born on February 21, 1878 in Paris. [Image at right] She was the daughter of an Egyptian mother, Mathilde and a Turkish father, a banker named Maurice Moïse Alfassa, both non-observant Jews. Mirra studied Arts at Julian Academy and specialized in painting. Her artwork was exhibited at the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (1903-1905). She married the painter Henri Morisset. They had a son together and were divorced in 1908.

Mirra Alfassa had also a tremendous interest in the esoteric and the occult path. In 1911 she married diplomat Paul Richard, and they traveled together to Pondicherry in 1914. There she met Aurobindo Ghose who recognized her spiritual awareness. Mirra and Paul Richard went back to France because of the war and traveled to Japan in 1916. They returned to Pondicherry in 1920 and settled down near Sri Aurobindo. Eventually, her husband became upset, left their home, and asked her for a divorce in 1922.

Mirra Alfassa and Sri Aurobindo became spiritual partners, with the goal of emancipating mankind from its suffering condition. Apparently, they had no sexual union, and they both recommended that their disciples avoid sexual relationships. On his side, Sri Aurobindo had practiced brahmacharya since his involvement into politics.

Aurobindo Ackroyd Ghose, named Aurobindo Ghose after 1902 and Sri Aurobindo after 1920, [Image at right] was first a brilliant student in England where he got awards in Literature, Latin, and Greek translation. He also studied European languages such as Italian, German, and French. He went back to India in 1893 with the revolutionary project to free India from the British. He became one of the national revolutionary leaders in 1905 in Calcutta as redactor of Bande Mataram, one of the first nationalist newspapers in which they claimed independence for India. In 1907, police caught him, his brother Barin and his companions and put them in jail at Alipore. His brother Barin had tried to bomb an English citizen but failed and was under arrest. During the one year Aurobindo Ghose spent in prison, he practiced yoga and meditation and learned another view of mankind’s limitations. Prison was the occasion for him to get free from ordinary consciousness, to join the Moksha and to awake from the usual narrow human mind. He received freedom as a result of work by a brilliant Indian lawyer one year later and ran away from Calcutta, heading first to Chandernagor and then to Pondicherry, the colonial French counters. He stayed secretly in Pondicherry under French secret services control, studying Vedas and yoga in a house. His meeting with Paul Richard and Mirra Alfassa gave him first the occasion to have part of his work published and the possibility to speak loudly, because Paul Richard was an official diplomat and had been a French congressman candidate. But his yogic retreat was well-known by his disciples as was his status as a Indian for the independence, and so he received the honorific name of Sri Aurobindo.

Sri Aurobindo renamed Mirra Alfassa the Mother in 1926 and gave her the responsibility to lead his Ashram and his disciples. Meanwhile, he retreated to his room to meditate and write until the end of his life in 1950. Therefore, the Mother had already been leading the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and his disciples for twenty-four years when he died.

The number of disciples had increased since the Word War II because many Indians had run away from the North of India, which was under the military threat of Japan. Entire families kept arriving at Pondicherry so the Mother necessarily had to change her mind about having only brahmacharyin disciples. Instead, she welcomed Gujuratis and Bengalis in the Ashram (Beldio 2018). She founded the school of the Ashram and started to give public talks to children and their parents. But her aspiration was to found another type of society, more like Charles Fourier’s in the lineage of the XIX social utopia, as scholar Leela Gandhi highlighted.

The Mother’s was well connected to the political elite of New Delhi, including Indira Gandhi and Prime Minister Nehru. She was more strongly linked to Indira Gandhi since she had facilitated the attachment of Pondicherry to India. She had also recommended Maurice Schuman, for example, and was even able to convince Delhi to let the Sri Aurobindo Society buy a piece of dry Land in Tamil Nadu, ten kilometers away from Pondicherry in order to found Auroville. The Sri Aurobindo Society was founded in 1961 by the Mother and supported by affluent Indians (Kapur 2021:145).

Auroville was founded on February 28, 1968, in Tamil Nadu by Mirra Blanche Alfassa, the Indian president and 124 National Representatives of the World with the support of UNESCO. The official purpose of the Indian Government for the Auroville’s project was defined as founding a “cultural international city” (Minor 1999:91) whereas the Mother aimed to found a “spiritual city” corresponding to Sri Aurobindo’s ideals (Heehs 2016). She wrote the Auroville Charter in 1968 (The Mother 1991:27). While Sri Aurobindo represents the etymological origin and the cornerstone of Auroville, Mirra Alfassa, the Mother, inspired the consciousness of Aurovilians and was the one who realized Aurobindo’s spiritual vision by founding and building Auroville.

The early settlement took place in Forecomer, Certitude, Auro-orchad, Hope and the Aspiration and Promesse communities (Southeast from the actual Auroville center), which are closer to Pondicherry. The Mother and the Sri Aurobindo Society were able to buy territories, especially between 1964 and 1976, and this process has not yet been finished. The acquisition process is detailed by Dayanand (2007), Dayanand, one of the Mother’s disciples, was in charge of buying the land (Dayanand 2007). He discussed with every owner why the community wanted to purchase the land and obtained agreement from neighbors in order to set the land’s official limits. However, even in 2006 nearly a quarter of the urban area (280 acres) and two-thirds of the greenbelt (2,000 acres) didn’t belong to Auroville but rather to the villages. A further complication has been that when land is not occupied, local people have the right to occupy it. And it eventually becomes their property. In addition, while the construction of Auroville started with the support by UNESCO (1966, 1970 and 1983) and the Federal State of India, approval of the Local Plan by Chennai had not been granted. An exemption was granted (Ospina-Rodriguez 2014:31) in this case.

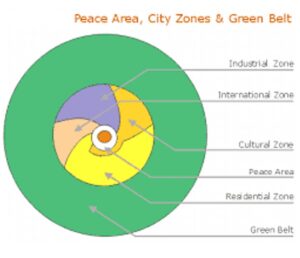

Auroville is organized around the Matrimandir at the centre, [Image at right] which literally means the temple of the Mother, and consists of a thirty-six Mt. diameter geode covered by a layer of fine gold. It is surrounded by gardens and located close to the banyan tree which represents the historical centre of Auroville. It was the only big tree in the neighborhood in 1968. There is a meditation room on the top floor, with a 70 cm. diameter crystal globe ceiling receiving sunlight and reflects its luminance.

After the death of the Mother in 1973 and before the Matrimandir was built, the Sri Aurobindo Society, owner of Auroville’s territories, tried to repossess the entire project and brought that case to the High Court of Calcutta. Aurovilians awaited a verdict for years. Their first victory occurred in 1976 when The Court of Justice of Calcutta removed S.A.S.’s financial control of Auroville. In a second victory, in 1980, the Auroville Foundation regained control over territories from SAS Auroville. The community then was placed partially under the Indian State’s control.

These outcomes were attributable in part to Indira Gandhi, who had supported the Auroville project in many ways. First, she appointed a committee to investigate the Sri Aurobindo Society in 1976 (Breme 2016:306), which led Auroville being allowed to open a bank account. Second, she created the Auroville Foundation Act 1980, which established community status for Auroville. This was extended until the Auroville Foundation law was passed in 1988 under Indira Gandhi’s successor, Rajiv Gandhi (Breme 2016:298).

Auroville’s members have been working since 1988 to demonstrate their ability to live a sustainable, spiritual and ecological life. This charts a course between both the mainstream western and the traditional Indian way of life. Major projects in developing the Aurovillian mission include:

The community has reforested the dry land of Auroville with 3,000,000 trees of different species since 1968.

Construction of the Matrimandir was completed in 2008, with the labor from neighboring villagers.

Auroville has created private enterprises and collective services to the surrounding community, such as schools and a solar kitchen that serves dinners.

The community has developed specific ecotechnology and agroforestry programs that have furthered India’s development, especially the wind electrical production in Tamil Nadu.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Auroville was originally conceived as “an international city of the future” where all people would live in peace and unity. However, the understanding of this initial goal implied (according to the Mother) leaving all doctrines and beliefs from the past behind. In this sense, Auroville has been futuristic, and this future is actually plural. Further, the Mother’s long speech could be interpreted in many different  ways, and one of her core values was that one action contains more meaning than a text or a thought, so that the future will reveal itself through innovative actions. Overall the Mother’s Agenda [[Image at right] may be the best guide to Auroville’s core values because of its reverence for the Mother’s speech and her status as the community’s founder and spiritual guide. There is, of course, some paradox about the reverence in which the Mother is held as beliefs and doctrines are considered remains from a past that is expected to disappear the practice of any religion within the community is prohibited. Although the Mother’s Agenda has been rejected by the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, the Auroville community was built around the Matrimandir (literally the temple of the Mother), and it has adopted the vision of the Mother rather than that of the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo.

ways, and one of her core values was that one action contains more meaning than a text or a thought, so that the future will reveal itself through innovative actions. Overall the Mother’s Agenda [[Image at right] may be the best guide to Auroville’s core values because of its reverence for the Mother’s speech and her status as the community’s founder and spiritual guide. There is, of course, some paradox about the reverence in which the Mother is held as beliefs and doctrines are considered remains from a past that is expected to disappear the practice of any religion within the community is prohibited. Although the Mother’s Agenda has been rejected by the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry, the Auroville community was built around the Matrimandir (literally the temple of the Mother), and it has adopted the vision of the Mother rather than that of the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo.

There are other influential texts on Auroville authored by the Mother and Sri Aurobindo that have been published by the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo in Pondicherry. Further, Mother’s Agenda has been published in France by Satprem, a nom de plume used by Bernard Enginger that was given by the Mother. Enginger was one of her favourite spiritual sons, and the Mother had been in conversation with him for thirteen years. Mother’s Agenda is the compilation of these conversations, which he recorded and transcribed. This book is especially important for Aurovilians who arrived after the Mother passed away in 1973 because it offers deeper insight of her vision. Satprem also was “overtly supportive of the rebellion” by Aurovilians against the Sri Aurobindo Society, which sought to take over Auroville in 1975 (Kapur 2021:148).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The main practice of any follower of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother is integral yoga (Heehs 2016) (also named purna-yoga), which might include karma yoga (yoga of work described in the Bhagavad Gita), jnana-yoga (yoga of knowledge and consciousness), bhakti yoga (yoga of love and devotion), and the yoga of self-perfection. The yoga of self-perfection contains three steps: it begins with the transformation of the ordinary consciousness by realizing the psychic being. It continues with the realization of a spiritual consciousness (also called enlightenment) that is the goal of Buddhism and Vedanta teaching. It ends with the supramentalization (or “deification”) of mind, heart and the body’s cells. Aurovilians are generally more dedicated to the karma yoga, but practise the integral yoga as individuals, according to their specific aspirations.

Even though rituals and religious practices originally were banned from Auroville, there are two main rituals that take place each year in Auroville near the Matrimandir [Image at right] in a huge amphitheater: a bonfire commemorating the birth of Auroville on February 28, and another one celebrating Sri Aurobindo’s birthday on August 15.

As Horassius (2018:50) described the February 28 ritual:

The bonfires consist of morning meetings (4 a.m.) for a silent meditation. Sitting in the amphitheatre near the Matrimandir, a large fire is lit before sunrise (about 5 a.m.) After this silent meditation, the recorded voice of the Mother spreads the message of the Charter and a text from the Mother or Sri Aurobindo is read.

Apart from these two annual rituals, the Matrimandir itself contains a meditation room where Aurovilians are invited to spend their free time concentrating on the divine. It was built between 1972 and 2008, and it is generally considered the spiritual heart of Auroville. It represents the collective meaning of participation and is a major symbol for the community

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Auroville was originally constructed to support as many as 50,000 residents, but it has never approached that population size. Over the first few decades the population was only a few hundred. Most of the early residents were from India, Germany, and France. The population later grew to over 2,000 adult members from almost sixty nations.The first Aurovilians were 1970s era young adults whose envisioning was closer to a libertarian thought than to a religious discipline. And Mother had suggested that Auroville should be a kind of “divine anarchy.” As a result, the community resembled what David Graeber refers to as a zone of democratic improvisation (Graeber 2014:105–06):

…spaces composed of a motley amalgam of people, most of whom have historically experienced methods of democratic self-government, and placed outside the immediate control of the state (…) that they may find themselves at the confluence of global influences. On the one hand, these communities are absorbing ideas from all over the world, and their example is having an important impact on social movements around the world.

The community charter reflected this spiritual idealism:

Auroville belongs to nobody in particular. Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole. But, to live in Auroville, one must be a willing servitor of the Divine Consciousness.

Auroville will be the place of an unending education, constant progress, and a youth that never ages.

Auroville wants to be the bridge between the past and the future. Taking advantage of all discoveries from without, and from within. Auroville will boldly spring towards future realizations.

Auroville will be a site of material and spiritual research for a living embodiment of an actual human unity.

Auroville’s organizational structure gone through three phases. Until 1973, the community functioned under the charismatic authority of the Mother. Between 1973 and 1988, charismatic authority resided in the community itself as it sought to demonstrate that it could survive as a community. Beginning in 1989, the Master Plan Development phase began under the control of the Indian State.

As Marie Horassius has described the early days (2021):

In the early days of Auroville, it was the Mother who was called upon to make decisions and harmonize coexistence. During the meetings known as “meetings in aspiration” (the settlements), she elaborated some guidelines. She had been explaining, since 1972, that the superior principle would be a “Divine Anarchy”: to try to have as few rules as possible and to observe the individual constancy on one’s practice. The Yoga discipline applied to guarantee the equanimity of the being and the temperance of the spirit. She had previously mentioned the idea that if Auroville achieved its goal (of hosting a spiritualized community), a group of seven to eight people with “intuitive intelligence” could then form a committee from which the residents would request decisions for the community. In the meantime, prior to 1973, the residents had followed the principle of charismatic authority of the mother managing their lives, the community’s economy, the property management and the construction.

Upon the Mother’s death in 1973 the community faced a new challenge without its charismatic leader and with a split between the Sri Aurobindo Society and the community. The community governance system proved unwieldy as it sought to incorporate its archaic ideal, bureaucratic realities, and the need for transparency. Finally, the Central Government of India enacted the Auroville Foundation Act in 1988, giving the community a status and the possibility to organize itself. In this act, Aurovilians were asked to build a clear structure.

According to this structure, the whole property is managed by the Indian Government.“The “Assembly of Residents” where all decisions are made selects a working committee to manage some things to be done in cooperation with the Governing board and the Foundation. There also are two external oversight groups: the Governing Board (GB) and the International Advisory Council (IAC). Finally, below the Assembly of Residents there are two other subgroups both responsible for external and internal community affairs: the Working Committee and the Auroville Advisory Council.

Wishing to break with the spontaneous participation that has eventually led to conflicts of interest, Aurovilians subsequently set up new selection systems. Several multi-person tables select, among their peers, the people considered the most “likely to become good decision makers,” and these proposals are pooled and deliberated upon until a harmonious decision emerges. This “new model of selection” remains very common in Auroville. It is similar to what has existed before, but with an increased focus on the “meritocratic” judgment of peers among themselves, linked to the reputation and distinction within the collective.

Even though Auroville was initially conceived as an international city, it has been slowly reframing its identity into a spiritual ecovillage that fits the global ecology paradigm. In this regard, Auroville Earth Institute has been specializing in eco-house research (Fricot 2021:38) since 1989, which led to its winning a COP22 Low carbon Award in 2016. Also, Sadhana Forest is a recent community specialized in sustainable development in dry land and reforestation.

Auroville’s complete territory is estimated between 20km2 and 25km2 (Horassius 2021: 237), a one-kilometre circle’s diameter for the center divided into four areas around the Matrimandir: the cultural, the industrial, the international and the residential area. Beyond these four zones there is the Greenbelt, where organic farms and forests are settled. [Image at right]

Auroville has become a kind of healthy green paradise and it is a current attraction for investments and tourism. However, the process of becoming a member is not easy. It requires time and goodwill (The goodwill is a core value of Auroville as the Chart of Auroville reminds it: “one must be a willing servitor of the Divine Consciousness”). Further, the aurovilian community defends its main aim, especially when there are several other tendencies such as conceiving it as an international city, a place for a lifestyle closer to nature, the yogic vision of mankind or even the socioeconomic and technological view, among others.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Wealthy Indians from the Sri Aurobindo Society, owner of Auroville before 1988, were probably closer to nationalistic Hinduism than the Congress and Indira Gandhi, who had just established the Emergency State (Breme 2016:309). At that time, The Sri Aurobindo Society sought the surrender of Auroville’s legal trust and the elimination of the “hippies’ lifestyle” in the area. The tension between Auroville and The Sri Aurobindo Society is suggested by rumors that villages were paid to fight with Aurovilians and, on one occasion, the Society convinced the police to temporarily jail eight Aurovilians (Kapur 2021:155; Heehs 2016). However, Satprem intervened, called the foreign embassies in New-Delhi and used “his connections to help Auroville” (Kapur 2021:155). A week later, foreigner prisoners were released and, on that occasion, the Auroville’s project became of a great Indian public concern (Heehs 2016). After Auroville’s takeover by the Indian Central State in 1988, Auroville addressed its first challenge by becoming more stable step by step and by being recognized by the rural neighborhood.

Auroville has experienced a number of other challenges. Joukhi and Horassius have reported that the most recurrent conflicts in Auroville are about the buying and selling of land (Joukhi 2006:100; Horassius 2021:226; Jukka Joukhi 2006). This issue was partly mitigated due to the Aurovilian’s need for labour and Tamil’s need for jobs and income. Further, Aurovilian volunteers contributed energy to open schools for villagers, provide drinkable water, build health centres, etc.

Jessica Namakal (2012) has offered a broader critique of Auroville: that western culture often takes advantage of other civilizations by establishing colonial-like systems. In this case, Auroville employs more than 5,000 Tamoul villagers every day, which implies an economical and hierarchical relation between Auroville’s wealthy members and impoverished villagers. So, Auroville is not an anti-capitalist paradise as some Aurovilians might have dreamed. However, it might also be argued that Auroville remains preferable to the pure capitalist market in which young Indian and Bangladeshi children work every day producing cheap clothes for the West while risking their own lives. Auroville enforces some unemployment rules, and so most villagers, especially women, prefer to look for jobs in Auroville because of these better working conditions.

Several women have commented on this situation: Usha, working more than 12 years by Wellpaper in Auroville, stated that:

The government is not doing anything for people in these villages. They only come during the elections and offer bribes in exchange for votes! That is why Auroville has a good reputation. Working here is like working in a government job. It provides us with many benefits and conveniences. Will our government be willing to offer us this kind of job opportunities? I do not think so (Gürkaya, 2018:35).

Lakshimi, working more than 20 years by “Naturellement” in Auroville, stated that:

That’s why Auroville jobs are beneficial for women in these villages. The jobs outside are more difficult and have less benefits. That is why I will always prefer here than elsewhere! Even if they pay me more, I would not change it for the world (Gürkaya, 2018:36).

Auroville is not a wealthy community overall. Most of Aurovilians’ foreigners are highly educated, but not necessarily wealthy, and Auroville depends as a whole on foreign donations. The community does offer support to members in need as some poor Aurovilians completely depend on “maintenance,” an amount of money given to everyone in Auroville.

As the community continues to evolve, some Aurovilians are becoming native and some Tamoul villagers are turning into businessmen with others Aurovilians. Therefore, a neo-colonial domination couldn’t be described only with categories of ethnicity, gender, and class. Instead, categories of deep-ecology followers versus urban builders and planners need to be considered. As the New York Times (Schmall 2022) described this division during a recent conflict over the direction of development, “The divide between those Aurovilians who want to follow the Mother’s urban development plans — known as constructivists — and those who want to let the community continue developing on its own — organicists — has long existed.” There is also currently a common fight between some Aurovilians linked to certain villagers against other Aurovilians linked to other villagers. Auroville’s project was meant to be the international city of peace and truth. However it is clear that this goal is elusive and will involve continuing struggle.

IMAGES

Image #1: Mirra Alfassa.

Image #2: Sri Aurobindo (Aurobindo Ackroyd Ghose).

Image #3: Arial view of the schema of Auroville’s sectors. Accessed from https://auroville.org/contents/691 on 15 October 2021.

Image #4: Cover of Mother’s Agenda. Accessed from https://auroville.org/contents/527 on 15 October 2021.

Image #5: The Matrimandir.

Image #6: Auroville’s territory, with the a one-kilometre circle divided into four areas around the Matrimandir.

REFERENCES

Auroville Foundation Act. 1988. Accessed from https://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1988-54.pdf on 2 September 2021

Auroville Organization & Governance. Accessed from https://auroville.org/categories/13 on 1 September 2021

Beldio, Patrick. 2018. The Mother Profile, Accessed from https://wrldrels.org/2018/10/13/the-mother-nee-mirra-blanche-rachel-alfassa/

Bey, Hakim. 2011. T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. Autonomedia Anti-copyright.

Brême, David. 2018. La figure de la Mère, Mirra alfassa (1878 — 1973). Une analyse des hybridations culturelles de ses représentations. Thesis in Religious Studies, Uqam. Accessed from https://archipel.uqam.ca/11515/ on 28 November 2021.

Brême, David. 2016. “L’État indien et le statut “spirituelˮ d’Auroville.” Religiologique, Intersection du Droit, de l’État et du religieux no 34. Accesed from www.religiologique.uqam.ca on 28 November 2021.

Dayanand. 2007. Premiers pas sur la terre d’Auroville. Accessed from https://www.auroville-france.org/index.php/acres-for-auroville on 28 November 2021.

Fortin, Andrée. 1985. “Du collectif utopique à l’utopie collective.” Anthropologie et Sociétés 9:53–64.

Fricot, Pauline. 2021. “Auroville, l’utopie fait de la résistance.” Géo 506:28-41.

Graeber, David. 2014. Des fins du capitalisme. Possibilités I – hiérarchie, rébellion, désir. Translated by Maxime Rovere and Matin Rueff. Paris: Payot.

Gürkaya, Cansu. 2018. L’Empowerment des femmes villageoises au sein des unités de travail à Auroville. Les cas de Wellpaper et de Naturellement, Mémoire de sociologie, Master Genre, Politique et Sexualité, Dir. Pruvost Geneviève, EHESS, Paris.

Heehs, Peter. 2016. Integral yoga. World Religions and Spirituality Project. Accessed from https://wrldrels.org/2016/10/08/integral-yoga-aurobindo/ on 28 November 2021.

Horassius, Marie. 2021. Ethnographie d’une utopie, Auroville cite international en Inde du sud. Thèse non publiée.

Horassius, Marie. 2018. “Rituels et foi au coeur d’une utopie : oscillations et négociations autour des pratiques croyantes à Auroville.” Religioscope. Accessed from www.religioscope.org/cahiers/15.pdf on 28 November 2021.

Horassius, Marie. 2012. Aire de recherche, ère de la quête du sens. Ethnographie d’une utopie : l’exemple de la communauté internationale d’Auroville. Mémoire de maitrise. Paris: École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Joukhi, Jukka. 2006. Imagining the other: Orientalism and Occidentalism in Tamil-European Relations in South India. Thesis of Ethnology, University of Jyvaskyla.

Kapur, Akash. 2021. Better to have gone. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Larroquette, Jean. Auroville, un aller simple ? Paris: éditions Chemins de tr@verse

Minor, Robert N. 1999. The Religious, the Spiritual and the Secular: Auroville and Secular India. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Mother, the (Mirra Alfassa). 1991. La Mère parle d’Auroville. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department.

Mother, the (Mirra Alfassa) & Satprem (Bernard Enginger). 1979-1982. Mother’s Agenda. Thirteen volumes. New York: Institute for Evolutionary Research.

Namakkal, Jessica. 2012. “European Dreams, Tamil Land. Journal for the Study of Radicalism 6:59-88.

Ospina-Rodriguez V. 2014. AV Bio-Region. Integration territoriale d’Auroville dans sa bio-region. Master thesis, (dir.) Foucher-Dufoix Valérie, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris-Belleville.

Patenaude, Monique. 2005. Made in Auroville. Montréal: Édition tryptique.

Schmall, Emily. 2022. “Build a New City or New Humans? A Utopia in India Fights Over Future.” New York Times, March 5. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/05/world/asia/auroville-india.html?searchResultPosition=1 on 10 March 2022.

Publication Date:

30 November 2021