Pope Michael

POPE MICHAEL TIMELINE

1958 (October 9): Pope Pius XII died.

1959 (January 25): The new pope, John XXIII, announced his intention to summon a general council in Rome.

1959 (September 2). David Bawden was born in Oklahoma City.

1962–1965: The Second Vatican Council was held in Rome.

1969 (April 5): Pope Paul VI promulgated a new Roman Order of the Mass, colloquially known as the Novus Ordo.

1970: French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre founded the traditionalist Society of St. Pius X (SSPX).

1970–1973: The new Roman Missal, translated into the vernacular, was gradually implemented throughout the Catholic world, drastically limiting the possibility of using the pre-conciliar Order of the Mass.

1972: The Bawden family stopped attending Novus Ordo parishes and sought Masses, said by traditionalist priests, including priests from SSPX.

1973: Excommunicated Mexican Jesuit Joaquín Sáenz y Arriaga published Sede Vacante, arguing that Paul VI was not a valid pope and that a new conclave should be held.

1976 (May 22): Archbishop Lefebvre confirmed David Bawden in Stafford, Texas.

1977 (September): Bawden was admitted to SSPX’s seminary in Ecône, Switzerland.

1978 (January): Bawden was transferred from Ecône to the SSPX seminary in Armada, Michigan.

1978 (December): Bawden was dismissed from the seminary

1979: The Bawden family moved to St Marys, Kansas, where David Bawden worked at the SSPX-run school.

1981 (March): Bawden resigned from his work at the school and left SSPX.

1981–1983: Vietnamese Archbishop Pierre Martin Ngo-Dinh Thuc consecrated sedevacantist bishops who, in their turn, consecrated other bishops for work in the United States.

1983 (26 December): David Bawden signed an open letter arguing that none of the traditionalist groups conferred valid sacraments as they lacked proper jurisdiction.

1985: Bawden wrote “Jurisdiction during the Great Apostasy,” developing his ideas about the lack of sacramental validity in the traditionalist movement.

1987: Bawden began to be convinced that a new conclave would be possible.

1988: Bawden examined, and for some time believed in, the claim that Cardinal Giuseppe Siri was elected pope in the 1963 conclave but was forced to decline.

1989 (March 25): Bawden took a vow to work towards the election of a pope.

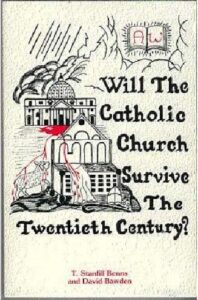

1989 (May): Mainly based on earlier writings, Teresa Stanfill Benns and David Bawden started preparing a book where the case for the conclave was expounded.

1990 (January): Benns and Bawden published Will the Catholic Church Survive the Twentieth Century? It was distributed to sedevacantist clergy and laypeople calling for a papal election.

1990 (16 July): A conclave with six electors was held in Belvue, Kansas. Bawden was elected pope, taking Michael I as his papal name. The Vatican in Exile was established.

1993: The Bawden family moved to Delia, Kansas.

2000: Pope Michael initiated an active online ministry.

2006: The group planned the ordination and consecration of Pope Michael, but the ceremonies were canceled shortly before the event should take place.

2007: Teresa Benns and two others who had participated in the 1990 conclave left, denouncing the validity of the election and, consequently, Bawden’s papal claims.

2011 (December 9-10): Independent Catholic bishop Robert Biarnesen ordained Pope Michael, a priest, consecrated him a bishop, and crowned him pope.

2013: Pope Michael moved to Topeka, Kansas.

2022: (August 2): Pope Michael died in Kansas City.

2023 (July 29): Archbishop Rogelio del Rosario Martínez was elected the successor of Pope Michael at a conclave in Vienna. He took Michael II as his papal name.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

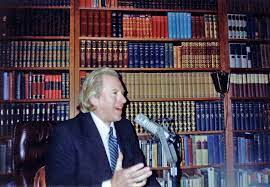

David Bawden (1959–2022) was elected Pope Michael I in a 1990 conclave in Kansas. [Image at right] He was neither the first nor the last man to become an alternative pope during the twentieth century. There have been dozens of others who claimed that they, not the vastly more recognized pope in Rome, are the true leader of the Catholic Church. Generally, they argue that we live in an era of general apostasy and that the modern church, particularly after the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), has nothing to do with true Catholicism. Several of the latest Roman pontiffs were antipopes and leaders of a new non-Catholic religion (cf. Lundberg 2020 and forthcoming). Most alternative popes assert that they were elected through direct heavenly intervention, and David Bawden was the first elected in an alternative conclave. He claimed the pontificate for thirty-two years, leading a small group of followers.

The Second Vatican Council (a meeting of more than 2000 bishops) was arguably the most crucial event in modern Catholic history. Summoned by Pope John XXIII (1881–1963), the bishops met for four long sessions from 1962 through 1965. Eventually, Pope Paul VI (1897–1978) promulgated the final documents.

According to John XXIII, the council should be encompassed in the term aggiornomento (Italian for “updating”). During the conciliar sessions, the bishops debated many central theological issues: revelation, the church and its relation to modern society, liturgy, mission, education, freedom of religion, ecumenism, relations to non-Christians, and the role of bishops, priests, religious and laity. Though interpretations of their radicality differ, the final documents were very different from the original schemata (drafts) that the preparatory committees presented to the conciliar fathers. The changes became more substantial than initially expected.

During the council, there was a small but vocal group of so-called traditionalist bishops and theologians who more or less actively opposed many of the changes. The vast majority, however, signed the final documents. Even in the case of the much-discussed Dignitatis humanae, the Council’s Declaration on Religious Freedom, eventually, only three percent of the more than 2,300 bishops present voted against it. (For a detailed study on the deliberations and conflicts at Vatican II, see O’Malley 2008).

Building on Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Council’s Constitution on the Liturgy, in 1969, Pope Paul VI promulgated a new Roman Order of the Mass, often referred to as the Novus Ordo. It replaced the 1962 revision of the so-called Tridentine Mass, decreed by Pope Pius V in 1570. Soon, the new Missal was translated into many vernacular languages and implemented worldwide from 1970 onwards. The clergy had to accept the new liturgical books, and the possibility of saying Mass according to the old rite was increasingly difficult and, with few exceptions, impossible.

Though many Catholics welcomed or, at least, accepted the changes, groups of clergy and lay people, from the late 1960s onwards, felt betrayed and bewildered by the post-conciliar development. The new Order of the Mass, including the use of the vernacular, was the most apparent change noticed by ordinary Catholics. Opponents claimed that the Novus Ordo fundamentally changed the sacrificial character of the Mass. Some wondered how bishops, particularly the Roman pontiff, could endorse changes that they thought contradicted traditional Catholic teachings. (On post-conciliar traditionalism and the Mass reform, see, e.g., Cuneo 1997 and Airiau 2009).

In 1959, the same year John XXIII summoned what would be known as the Second Vatican Council, David Allen Bawden, the future pope Michael, was born in Oklahoma City. His mother, Clara (“Tickie”), [Image at right] was a cradle Catholic, while his father, Kennett, was a convert from Protestantism. The family was actively practicing parishioners, and David Bawden felt an early vocation to the priesthood.

In several of his written works, Pope Michael describes the family’s gradual alienation from the post-conciliar church. By the mid-1960s, some parishioners, including his parents, had noticed changes in the preaching and teaching of the catechism. However, changes became much more evident by 1971, when the Novus Ordo was introduced. (If not otherwise stated, Bawden’s biography and his group’s development are based on Pope Michael 2005, 2006, 2011, 2013a, 2013b, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2020.)

In late 1972, the Bawdens decided not to attend Novus Ordo churches anymore, instead approaching priests solely saying the traditional Mass. Such traditionalist clergy sometimes only arrived in the city a few times a year. By 1973, the Bawdens met priests from the newly founded and rapidly growing Society of St. Pius X (SSPX). Like other traditionalist groups, the Society had no permanent presence in Oklahoma, and priests arrived from Texas to say Mass in private homes, including Bawden’s (cf. The Daily Oklahoman, July 22, 1978).

SSPX was founded in 1970 by French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre (1905–1991), who was increasingly critical of the conciliar reforms. Its original vision was to educate seminarians who should continue saying the Tridentine Mass. SSPX’s center was in Swiss Ecône. The Society received provisional permission from the local bishop and soon attracted many seminarians. During the next couple of years, their activities were supervised by both diocesan and papal authorities. In 1974, Lefebvre wrote a Declaration where he saw the Vatican II and the post-conciliar development as signs of “neo-Modernist and the neo-Protestant tendencies,” in contrast to the “Eternal Rome, the Mistress of wisdom and truth.”

In 1975, the diocese decided not to renew SSPX’s status, ordering Lefebvre to disband the organization, and the pope publicly rebuked him, something almost unheard of. Lefebvre was explicitly forbidden to ordain priests for the SSPX. He did so anyway and was suspended. Still, despite the verdicts by the diocese and the Holy See, the SSPX activities continued and grew in France, Switzerland, and Germany, but not least in the United States, where they opened up a seminary in Armada, Michigan, in 1974, and established mass centers in many places. Lefebvre was very critical of the conciliar post-developments and the teachings of Pope Paul VI. In 1976, he referred to the Novus Ordo as a “bastard Mass,” and though he never explicitly declared either Paul VI or John Paul II heretics pope, he stated that a future pope could pass such a verdict. (On Lefebvre and SSPX, see, e.g., Sudlow 2017 and, for an inside perspective, see Tissier de Mallerais 2002).

However, other groups went further, claiming that Paul VI was a manifest heretic and antipope; therefore, the Holy See was vacant, a position later known as sedevacantism. One early advocate was Francis K. Schuckardt (1937–2006), who, from the late 1960s onwards, traveled the United States denouncing the Second Vatican Council and the Novus Ordo, claiming that Paul VI was a false pope. His group became known as the Fatima Crusade. Still, after an independent Catholic bishop had consecrated Schuckardt in 1971, it was formally known as the Tridentine Latin Rite Church, though understood as nothing else but the Catholic Church. With centers in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and later in Spokane, Washington, they counted thousands of members and large religious communities. (On Schuckardt, see Cuneo 1997:102–13).

Another early sedevacantist exponent was the excommunicated Mexican Jesuit Joaquín Sáenz y Arriaga (1899–1976). In several texts written in the early 1970s, he declared Paul VI a manifest heretic, an antipope, and even the Antichrist. He argued the need for a new conclave to solve the problem, went to Rome to explain his position to well-known traditionalist cardinals but met no support, and then tried to convince traditionally minded bishops. (On Sáenz y Arriaga, see Pacheco 2007).

According to Bawden, on May 22, 1976, while visiting Stafford, Texas, Sáenz y Arriaga met Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre to present his case. The latter did neither assume the sedevacantist position nor the need for a new conclave. The same day the two traditionalists met, Lefebvre confirmed David Bawden. According to Bawden’s later testimonies, the place bubbled with rumors about the papal question and the possibility of a new conclave. The problem with this assertion is that Sáenz y Arriaga died in late April 1976. However, Bawden never explicitly claimed that he had met Sáenz y Arriaga but mentioned that two other Mexican sedevacantist priests were present. That would be possible, and later the community in Stafford would turn to the sedevacantist position. What is clear is that Sáenz y Arriaga and Lefebvre did meet, but that was in France in 1973.

In 1977, aged eighteen, Bawden was admitted to the SSPX seminary at Swiss Ecône, beginning his studies for the priesthood. The more natural solution, as he did not know French, was to study at the SSPX seminary in Armada, but he was informed that it was full. Still, in early 1978, he was transferred there (cf. Daily Oklahoman, July 22, 1978).

The papal question and the possible sede vacante were much discussed within the SSPX. Bawden mentioned that in 1977, he heard an SSPX priest publicly declaring the Holy See vacant and that someday a pope had to be elected. According to Bawden, in the early 1980s, most SSPX priests in the United States were de facto sedevacantists. They thought Lefebvre was too diplomatic in his contacts with the Holy See, especially after the election of John Paul II (1920–2005). Many priests left or were expelled from SSPX for holding sedevacantist views, refusing to pray for the pope in Mass, and not wanting to use the 1962 Missal, revised by John XXIII, but stuck to the pre-1955 editions. (On sedevacantism, see Airiau 2014. For a U.S. inside perspective, See Cekada 2008).

David Bawden’s stay at the SSPX seminary in Armada would be brief, and towards the end of 1978, he was dismissed. In his later texts, Bawden claims that he was given no reason for the decision. Though he successfully appealed to Marcel Lefebvre, who stated that he would be re-admitted to one of the SSPX seminaries, in the end, he was not.

In 1979, the Bawden family moved to St. Marys, Kansas, a small town that had become one of SSPX’s district headquarters. There, David Bawden was employed at the boarding school recently opened by the SSPX. He left work in March 1981. In his later writings, Bawden stated he encountered many “un-Catholic things going on” and chose to leave. At the same time, he also abandoned SSPX for good.

Several families had moved to St. Marys in search of a traditionalist haven. Still, they harshly criticized the SSPX district superior, who also was the school’s rector, and questioned the school’s economic basis. Some of the disenfranchised members left the town, while others stayed. According to articles published in The Kansas City Star in 1982, the superior had banished several families, including the Bawdens, from entering campus and forbade them from receiving the sacraments from any other priest (The Kansas City Star, April 18 and 19, 1982).

Leaving his work at the school, in the following years, David Bawden made a living as, e.g., a real estate agent, a furniture maker, and a homeschool tutor. Realizing that it would be difficult to become a Catholic priest under current circumstances, Bawden approached various traditionalist priests, seeking advice. Still, according to him, none of them was forthcoming. At the same time, he pursued theological studies on his own, gathering an extensive collection of older Catholic literature, mainly from closed-down seminary libraries (cf. Des Moines Register, November 4, 1990).

In the early 1980s, the traditionalist scene in the United States changed as several sedevacantist groups received bishops of their own. Vietnamese Archbishop Pierre Martin Ngo-din Thuc (1897–1984), who had lived in exile in Europe for two decades, stepped forward as a prolific consecrator. The bishops Thuc consecrated from 1976 onwards was a very heterogeneous group, but he did provide apostolic succession to a few sedevacantists, who could ordain priests and consecrate bishops. In 1982, Mexican Thuc-bishop Moisés Carmona-Rivera (1912–1991) consecrated George J.Musey (1928–1992), who, in his turn, almost immediately consecrated, Louis Vezelis (1930–2013), a bishop.

Thuc also consecrated Michel Louis Guérard des Lauriers (1898–1988), who held a somewhat different position, generally known as sedeprivationism. He claimed that the pope was validly elected and that the Holy See was “materially occupied,” but as the elected pope was a heretic, it was not “formally occupied.” There was no true pope, but he would become one if he abjured from his heresies and confessed the true Catholic faith. Laurier consecrated Robert Fidelis McKenna (1927–2015), a bishop active in the United States. (On Thuc and his consecrations, see Jarvis 2018a, cf. Boyle 2007a).

In the early 1980s, the question about a possible sede vacante primarily dealt with Paul VI and his successors and whether they had not been validly elected or had fallen into heresy after their election. At this time, the validity of the papacy of John XXIII was not a significant issue, even if traditionalists were critical of many of his teachings and often considered him at least a dubious pope. Still, some held that he was not validly elected either and that there had been no true pope after the death of Pius XII in 1958 (Airiau 2014).

On December 26, 1983, Bawden wrote an open letter arguing that Traditionalist priests administered the sacraments without proper jurisdiction and necessary papal licenses. They lost their office and incurred excommunication upon themselves. During the Great Apostasy, there was a time when sacraments, including the Mass, would not be celebrated. As a result, Bawden distanced himself from the traditionalist movement, and in 1985, he published another letter on the same issues, presenting more details. (The letters were re-published in, e.g., Pope Michael 2013b).

In 1988, Bawden heard about the reports that traditionalist Cardinal Giuseppe Siri (1906–1989), archbishop of Genua, had been elected in the 1963 conclave taking the papal name Gregory XVII. Still, due to Zionist, Masonic, and Communist threats, he was hindered from accepting office. Instead, Cardinal Montini (Paul VI) was elected in his place.

The Cardinal Siri thesis was initially presented by a small group of French traditionalists and convinced people in the United States, too. In 1988, Peter Tran Van Khoat, a Vietnamese who lived in Port Arthur, Texas, and claimed to be a Catholic priest went to Rome to investigate the matter. During their meeting, Siri said nothing about the election but referred to the vow of silence. In 1988, Bawden traveled to Khoat to talk about the matter and spent some time with his congregation. In his later writings, Bawden played down his interest in the Siri thesis, but in correspondence from 1988, he wrote that he believed that Siri was the pope and would submit to his authority. In any case, Siri died in 1989 without officially claiming the papacy. (On the Siri thesis, see Cuneo 1997:85-86; for evidence of Bawden’s views in 1988, see Hobson 2008).

From the early 1980s, several individuals and small groups on both sides of the Atlantic called for a conclave to re-establish papal jurisdiction; they were known as conclavists. In 1987, Bawden became convinced that it would be possible, and even necessary, to convene a conclave, including laypeople. On March 25, 1989, he took a formal vow to work toward the election of a pope:

We bind ourselves by this vow to place all our efforts toward the accomplishment of a papal election to end the current Sede Vacante. We shall not encumber ourselves with worldly pursuits, but will pursue Thy Kingdom instead until the completion of the task.

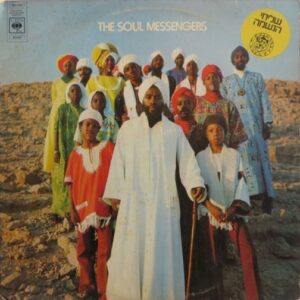

In May 1989, Bawden and his friend Teresa Stanfill Benns began compiling a series of earlier and new texts presenting the case for a conclave; Benns was the principal author. The result was a sizeable book titled Will the Catholic Church Survive the Twentieth Century? [Image at right] It was published in January 1990 and sent to known sedevacantist clergy and lay people in North America, Europe, and other places. In all, some 200 copies were distributed to more than twenty countries.

The gist of the book was the argument that the Holy See had been vacant from 1958 onwards, that there are no valid cardinals, and that the current bishops and priests lack jurisdiction. Still, the church is indefectible; it will exist until the end. A sede vacante could be prolonged but not perpetual. According to the authors, there was a possibility, and thus a duty for the small remnant, including laypeople, to elect a pope. Before that, however, they had to adjure their heretical positions and profess the true Catholic faith. After that, they could proceed with the election. (For details, see DOCTRINES/BELIEFS).

About half a year after the book’s publication, on 16, 1990, the conclave was held in Kennett Bawden’s consignment store in the small town of Belvue, Kansas. The vast majority of the book recipients did not even consider coming, but a small group showed interest. In the end, only eleven did arrive. Seeing that the planned conclave would be very small, some tried to stall the process. (For counter-arguments from one who was present but chose not to attend the conclave, see Henry 1998).

Eventually, eight people assembled for the conclave, of which six were electors, the others being minors: David Bawden, his parents, Teresa Benns, and a married couple from Minnesota. Bawden was elected in the first ballot, accepting the office and taking Michael I as his papal name. Several U.S. newspapers reported about the unique event: that there was a group that claimed that the real pope was not in Rome but in small-town Kansas (see, e.g., The Manhattan Mercury, July19, 1990; Kansas City Star, July 23, 1990; The Wichita Eagle, July 290, 199; Macon Telegraph and News, August 7, 1990; and The Miami Herald, August 17, 1990).

With the papal election, the Holy See was moved from Rome and became the Vatican in Exile, located at the place where the pope lived. The adherents believed that papal jurisdiction was reinstated, but it did not imply that Bawden was ordained a priest. Still, he hoped that some true Catholic bishops who lived behind the iron curtain or in China had not taken part in Vatican II and never celebrated the sacraments according to the post-conciliar forms. He anticipated that one of them would ordain him (cf. The Miami Herald, August 17, 1990).

With his parents, Pope Michael moved from St. Marys in 1993 and lived for twenty years in Delia, a village close to Topeka, Kansas, to which the Vatican in Exile was transferred. From there, he remained in contact with his small group of adherents by letter and phone. His father died in 1995, and he lived alone with his mother.

In 2000, Pope Michael began a very active internet ministry, constructing several websites. Though the number of followers remained low, only a few dozen, he became more widely known through the websites. Though the vast majority of the visitors found the papal claim ridiculous, Pope Michael’s group of adherents became a more international group, including individuals from, e.g., Europe, Asia, and the Americas. (One of the few published texts about Pope Michael in the early 2000s is Frank 2004:217–24).

Still, more than fifteen years after his election, Pope Michael was not ordained though he actively sought an independent Catholic bishop who could provide him with the necessary apostolic succession. In 2006, the papal press secretary was informed that after submitting to the papal authority, an independent Catholic bishop of the Mathew Harris lineage would ordain Pope Michael a priest, consecrate him a bishop, and celebrate the papal coronation (Mascarenhas 2006). Still, the plans were abandoned at the last moment.

In 2007, Teresa Benns and the Hunt couple who took part in the 1990 conclave left Pope Michael’s jurisdiction, accusing him of heresy, and concluded that they had not been valid electors and that Bawden was never the true pope. Thus, the only people left from the 1990 conclave were the pope and his mother. In 2009, Teresa Benns, the Hunt couple, and others signed a petition demanding that David Bawden abandon his false papal claims (Benns 2007; Benns 2009 and Benns et al. 2009).

In 2007, three film students from the University of Notre Dame made a short film about Pope Michael (The South Bend Tribune, January 20, 2008). As a continuation of the project, one of the filmmakers, Adam Fairfield, envisioned a full-length feature movie. As a preparation, he visited Pope Michael at his home on various occasions in 2008 and 2009. The result was the hour-and-half-hour-long documentary Pope Michael, which made the Kansan pontiff known in broader circles. [Image at right] It had a respectful tone, letting the pontiff explain his claims, following his daily life and his teaching of a few seminarians (Pope Michael 2010).

Shortly after the documentary movie was released, in December 2011, Pope Michael was finally ordained and consecrated by independent Catholic bishop Robert Biarnesen after submitting to the pope’s jurisdiction. Biarnesen had been made a bishop only a month earlier and claimed his apostolic succession through the Duarte Costa and Mathew Harris lineages. (On Duarte Costa and his lineage, See Jarvis 2018b, cf. Boyle 2007b. For Biarnesen, See also [“Database of Independent Bishops”])

In 2013, David Bawden moved to Topeka, Kansas. He continued his online ministry on several websites (e.g., www.pope-michael.com, www.vaticaninexile.com, and www.pope-speaks.com). The material on the website included books and articles on the heresies taught by modern antipopes and the defense of his claim to the papacy, but also more general spiritual reflections. From 2016 onwards, the group published The Olive Tree, a monthly journal. [Image at right] Pope Michael also had a Facebook account with numerous followers and a Youtube channel, posting new videos regularly. The contents included answers to questions and brief lectures. Sermons and Masses were also live-streamed.

Pope Michael and his close associate Fr. Francis Dominic, who was ordained a priest in 2018. started St. Helen Catholic Mission – St. Helen Catholic Church in Topeka. Masses, sermons, and catechetical material from the church are spread through social media and a website (Saint Helen Catholic Mission website).

In early July 2022, Pope Michael suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and had to undergo emergency surgery. At first, he seemed to recover but eventually passed away on August 2, 2022, aged sixty-two. With his death, the Holy See became vacant, and his adherents began to plan a conclave to elect a successor.

In June 2023, Filipino Archbishop Rogelio del Rosario Martínez (b. 1970) announced that a conclave would be held in Vienna starting on July 25. There were four papabili: two bishops and two priests. A candidate was elected in the first conclave session on July 25, but declined. In the fourth session on July 29, a new candidate was elected, but he, too, declined. Eventually, in the same session, Archbishop Martínez was selected and accepted the election. He took Michael II as his papal name. The result was publicly announced on August 9 (Lundberg 2023).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The case for the post-1958 vacant see, the non-validity of traditionalist clergy during the sede vacante, the necessity of re-establishing papal jurisdiction, and the validity of the 1990 conclave are the central themes in most texts authored by David Bawden/Pope Michael. The case was first outlined in the pre-conclave book, Will the Catholic Church Survive the Twentieth Century? written mainly by Teresa Benns but with contributions by Bawden. With various degrees of detail, Pope Michael presented the same ideas in numerous works (see Pope Michael 2003, 2005, 2006, 2011, 2013a, 2013b, 2016a, 2016b, 2016c, 2020), as well as in brief texts published on his websites.

The writings were based on interpretations of official church teachings in papal and conciliar documents and Canon Law. But they also build on a wide array of pre-1958 Catholic theologians. To some extent, he also includes end-time prophecies. Long quotations from sources make up a significant part of Pope Michael’s publications.

Among sedevacantists, there had been discussion as to whether Paul VI was not validly elected or if he lost office with the promulgation of the final documents of Vatican II in 1965 or earlier. Similarly, there was some discussion on whether John XXIII had lost the papal office or was not validly elected. There was a problem if a pope could be deposed, as only a pope could finally decide whether a pope had become a heretic. Another question was whether a person who was a heretic could be a validly elected pope.

To substantiate the claim that a heretic could not be validly elected a pope, some, Bawden included, referred to Paul IV’s bull Cum Ex Apostolatus Officio. In the bull, the pope decreed that if a bishop, cardinal, or pontiff before his elevation had “deviated from the Catholic Faith or fallen into some heresy.” In such a case, “the election shall be null, void and worthless.” Thus, even if the elect accepted the office, he would not be the pope and would not receive papal jurisdiction or authority (Quoted in Pope Michael 2003).

Pope Michael argued that Cardinal Roncalli (John XXIII) was not a validly elected pope and that the sede vacante began with the death of Pius XII in 1958. He claimed that Roncalli had been a known heretic before his elevation, e.g., because he was a freemason who had advocated the liberty of religion and ecumenism. The cardinal was a false prophet as he summoned a council whose explicit goal was to bring the church up to date, though the Catholic Church could never change. Roncalli was an evil version of John the Baptist who prepared the way for the Antichrist–Cardinal Montini, i.e., Paul VI, e.g., by appointing large numbers of masonic cardinals that would ensure his election.

According to this line of argument, as Roncalli’s election was invalid, his elevation of new cardinals was null and void, as was the conclave held after his death. Put more radically: If Roncalli was the false prophet paving the way for the Antichrist, Paul VI was the Antichrist. Drawing an analogy to the second beast in Rev. 13:11-17, Pope Michael claimed, “Montini transferred his power and that of Roncalli to the two horns; John Paul I and John Paul II; so that the beast appeared to be slain, but recovered and lived anew.” Needless to say, Pope Michael taught that Benedict XVI and Francis were antipopes, too.

Through Vatican II and the post-conciliar changes in the rites of sacraments, Montini being the Antichrist, “abolished the Continual Sacrifice” through his changes of substantial parts of the Order of the Mass. During this time, the Mass will cease temporarily and be supplied with “the abomination of desolation,” an expression from the Old Testament Book of Daniel. The effect was the creation of a new religion with new beliefs and rituals. In this new religion, the human being, not God, was venerated.

During the prolonged sede vacante beginning in 1958, there was no possibility of a valid Mass or administering most other sacraments as even the traditionalist clergy lacked jurisdiction, and their bishops acted as if they were popes. In fact, they were vitandi (excommunicated people that should be avoided) as they belonged to non-Catholic sects and were consecrated without necessary papal mandate. The proliferation of different traditionalist groups contradicted the belief in the unity of the Catholic church.

In the era of the Great Apostasy, Satan tries to destroy the church. Still, he will not be entirely successful as the Church is constituted by indefectibility, and St. Peter will have perpetual successors until the end. Though the vacancy was significantly prolonged, it cannot be perpetual. The question was who would elect a pope under current circumstances. Due to the extinction of the College of the cardinals (the ordinary electors) they were not an option, as they belonged to a new religion.

Pope Michael argued that in such a state of emergency, clergy and laity or even a group solely made up of laity could elect a pope. He pointed to the principle of equity, often referred to by the Greek word epikeia. Applied to the prolonged sede vacante and the absence of normal electors, for a greater good (the salvation of souls) others, including laypeople, have the right and subsequent duty to elect a pope. In such circumstances, “the church could reluctantly supply the jurisdiction for this one act, for no other more qualified body exists to perform such an act.”

According to Will the Catholic Church Survive the Twentieth Century? the potential electors should cease attending traditionalist services and not receive any sacraments during the time that remained until the conclave. Instead, they should devote themselves to prayer and studying the Catechism of the Council of Trent. Before the conclave, they should make a perfect act of contrition and a public abjuration of their heresies, pronounce the Holy See vacant, and confess the true Catholic faith according to Trent and the (First) Vatican Council. Only thus could they become qualified electors.

According to Bawden’s interpretation of Pius XII’s address to the Lay Apostolate World Conference on October 5, 1957, the criteria for being a papabile (someone who could be elected a pope) was that a person baptized male who has the use of reason and has not departed from the church through schism, heresy, or apostasy. Further, if the pope-elect was a layman, he must be willing to be ordained a priest as soon as possible.

Following these criteria, and according to Canon 219, a pontiff “legitimately elected, immediately upon accepting the election, obtains by divine law the full power of supreme jurisdiction.” It did not matter if the conclave was very small; David Bawden (Michael I) claimed that he was the true pope as he was elected “first in time” and thus “first in right.” Consequently, no other conclave should be held until after his death.

The “Papal Election Law of Pope Michael,” promulgated on August 26, 2008, provided several details about the procedure. It decreed that a successor should be selected within days of his death.

Our successor will be elected by a special, temporary Collegium, consisting of a Convenor and others, names which will not be disclosed to the general public, but which will be conveyed to those named as members. – – –

Immediately upon the death of the pope, the electors shall be contacted by phone and by all other modern means of communications as shall be found necessary by the convenor and the Collegium assembled shall proceed to gather for the election of a successor – – –

[T]he election shall commence at 9:00 am on the third day after the pope’s death, unless the electors have gathered earlier and decide to commence, although, if it is found necessary, the election may be delayed ten days (Quoted in Pope Michael 2011).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Though being elected the pope in 1990, Bawden remained a layman. This papal-layman status enabled him to perform duties regarded as jurisdictional and part of the teaching office, but he could not confer sacraments. Pope Michael could infallibly teach and interpret the Catholic doctrine and write and interpret canon law. He could preach, bless, and exorcise. Further, the pope could absolve priests and bishops who abjured their heresies and submitted to his jurisdiction. He was also able excommunicate church members. Like all laypeople, he could baptize and witness marriages. As a layman, however, he could not say Mass nor administer the sacraments of Penance, Extreme Unction, Confirmation, or Ordination (Pope Michael 2011).

Already in his first official papal communication written just after the conclave, he wrote: “Sadly we report that non of the reverend clergy has seen fit to submit themselves to the Apostolic See and remain under the censures of suspension and excommunication for their various crimes.” (Quoted in The Miami Herald, August 17, 1990). Thus, he continued a layman.

In a 2009 article, Teresa Benns, who was one of the electors in 1990 and remained an adherent until 2007 when she denounced the papal claim, writes that as most followers lived very far away from the pope’s home, they rarely met him and mainly communicated by phone, letters, and, later, email. Pope Michael also distributed sermons and other religious texts to the followers. According to Benns, as for sacraments, nothing changed by the election: “We simply continued to pray at home” (Benns 2009).

It would take twenty-one years until Pope Michael was ordained a priest and consecrated a bishop. Though he had contacts with several possible consecrators, for decades, no bishop submitted to his jurisdiction. Eventually, in 2011, Pope Michael was ordained a priest, consecrated a bishop, and crowned pope. The consecrator was independent Catholic Bishop Robert Biarnesen, who had been consecrated just a month earlier by Bishop Alexander Swift Eagle Justice, archbishop of the Holy Orthodox Native American Catholic Archdiocese.

Through them, Pope Michael could claim apostolic succession from several independent Catholic sources, such as the Duarte Costa, Vilatte, and Harris Mathew lineages. Through them, he was related to bishops of, e.g., the Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church, the Mexican Catholic Apostolic Church, the Old Roman Catholic Church, the Tridentine Catholic Church, and the Ecumenical Catholic Diocese of America. (See Pope Michael 2016d and for details on his lineages, cf. [“Database of Independent Bishops.”] On independent Catholicism and the centrality of the apostolic succession, See Plummer and Mabry 2006 and Byrne 2016),

With his ordination and consecration, Pope Michael thus could administer all sacraments of the Catholic Church, including daily Mass. To become part of the Catholic Church, now led by Pope Michael, a person had to make the Profession of Faith of Trent amended by the (First) Vatican Council but also make a special declaration of obedience and submission to the pontiff:

I accept the authority of the Roman Pontiff, that when he shall decide a matter it is forever closed. I accept the laws of the Church as the Church interprets them and reject any interpretation that contradicts the interpretation of the Church. I submit fully to Pope Michael I, Successor of St. Peter (Pope Michael 2005).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

As the pontiff of the true Catholic Church, Pope Michael was the unquestionable leader from his election in 1990 to his death in 2022, reigning from his Vatican in Exile. The offices of the Holy See were located in his home in St. Marys/Belvue (1990–1993), Delia (1993–2013), and Topeka (2013–2022), all places within a thirty-mile distance from each other. [Image at right]

Pope Michael never had a large gathering of adherents. Though the numbers were oscillating, for most of his papacy, they could be counted by the dozens. Just after his election in 1990, he claimed some twenty or thirty adherents (The Des Moine Register, November 4, 1990). In the early 2000s, the number seems to have been equal, and in the documentary movie, recorded in 2008–2009, Pope said there were “some 30 solid ones.” A few years later, they were between 30 and 50, though he claimed that a larger group showed interest in joining (The Salina Journal, May 28, 2005 and The Kansas City Star, December 30, 2006, Pope Michael 2010; Interview with Pope Michael 2010)

After his ordination and consecration, a few priests submitted to Pope Michael. 2013, he had two priests under his jurisdiction and claimed three others soon. In 2018, Pope Michael ordained his first priest, Fr Francis Dominic, who was, and still is, very active in publishing spiritual reflections and sermons through social media and teaching catechism via a website. He is based at the St. Helen Catholic Church in Topeka and worked closely with Pope Michael until his death (www.facebook.com/PopeMichael1, www.facebook.com/PatronSaintHelen, www.sainthelencatholicmission.org, and www.traditionalcatechism.com).

In an interview recorded shortly before his death in 2022, Pope Michael claimed that the number of adherents had grown substantially in recent years. He had several clerics under his jurisdiction, including one archbishop in the Philippines, Rogelio Del Rosario Martinez Jr. (b. 1970), a married man who had earlier been consecrated in the Duarte Costa lineage. In 2020, Martinez submitted to Michael as the pope and reconciled. Apart from the bishop, seven priests had joined his jurisdiction, and he had tonsured one brother. In the interview, Pope Michael stated that the total membership was probably at least a hundred, including groups in Topeka, St. Louis, Phoenix, and the Philippines, but with individual members in other countries (Interview with Pope Michael 2022; on Bishop Martínez, see The Olive Tree, October 2022 issue.)

After Pope Michael’s death, the church was defined as sedevacantist but announced that there would, indeed, be a conclave. In “An Open Letter to Concerned Catholics,” published in the October 2022 issue of The Olive Tree, Brother Stephen explained that Father Francis Dominic is the Camerlengo. He “is the chief in conducting the normal business of the Church after the death of the Pope,” and he is “also charged with the preparation of a new papal election.”

In September 2022, Archbishop Martinez wrote, “we have to establish first a solid community of Christ’s faithful who are aware of what we are doing, and who support our cause. Then we can proceed to the conclave if it is already ripe. Yet we must set a definite time table for it” (The Olive Tree, September 2022 issue). A few months later, Martinez wrote: “Let us not be in a hurry in getting into conclave. Haste is the enemy of sanctity” (The Olive Tree, November 2022 issue).

It was not until June 2023 that the church announced the date and place of the conclave to elect a new pope. The conclave was held in Vienna beginning on July 25. In the fourth session on July 29, Archbishop Rogelio Martinez was elected and took Michael II as his papal name (Lundberg 2023).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The official Roman Catholic Church has never issued any official statement about the 1990 conclave and the pontificate of Michael. A week after the conclave, a representative of the diocese of Kansas City said, “The archdiocese has no comment at all. If someone wants to leave the church, that’s up to them” (The Kansas City Star, August 14, 1990).

Very few traditionalists, even those who were conclavists, regarded the 1990 conclave and the papal election as valid. It was impossible for a conclave made up of only laypeople to elect a pope, much less one that included women. Some tried to organize new conclaves, including both sedevacantist clergy and laypeople.

In the 1990s, two other conclaves were held. One took place in Assisi, Italy, in 1994, where a group of around twenty sedevacantist clergy and laypeople elected the South African priest Victor von Pentz (b. 1958) pope. He took Lius II as his papal name. Though he accepted the office, his public ministry based in Great Britain seems to have been minimal. While he has never made any public statement on the matter, he does not appear to have claimed the papacy for many years (Lundberg 2016a).

Another conclave was held in Montana in 1998 when the former Capuchin priest Lucian Pulvermacher (1918–2009) became pope. It is unknown how many electors took part, probably a few dozen, though most were not physically present but phoned in. Pulvermacher took Pius XIII as his papal name but later changed it to Peter II. Like the other conclavist popes, he had a minimal number of adherents, and soon after the election, many left or were expelled. Still, Pius XIII had an active ministry for several years, publishing encyclicals and other official documents on a website (Lundberg 2016b).

In 2007, three original electors, including Teresa Benns, left Pope Michael’s jurisdiction, accusing him of heresy and claiming that the 1990 conclave and election were invalid and that David Bawden had never been the pope and should publicly renounce the office. Even in a state of emergency, she argued a conclave made up entirely of laypeople could not elect a pope, and women could never take part in a valid conclave (Benns 2009, 2012, 2013, 2018; Benns et al. 2009).

IMAGES

Image #1: Pope Michael (David Bawden).

Image #2: Pope Michael with his mother, Clara (“Tickie”).

Image #3: Cover of Will the Catholic Church Survive the Twentieth Century?

Image #4: Pope Michael documentary announcement.

Image #5: The Olive Tree journal logo.

Image #6: Pope Michael with his mother and a seminarian at his home in Delia.

REFERENCES

Airiau, Paul. 2014. “Le pape comme scandale: Du sédevacantisme et d’autres antipapismes dans le catholicisme post Vatican-II”. In La participation des laïcs aux débats ecclésiaux après le concile Vatican II, edited by Jean-François Galinier-Pallerola et al. Paris: Parole et Silence.

Airiau, Paul. 2009. “Des théologiens contre Vatican II, 1965–2005.” In Un nouvel âge de la théologie, 1965–1980, edited by Dominique Avon and Michel Fourcade. Paris: Editions Karthala.

Benns, Teresa. 2018. The Phantom Church in Rome: How neo-Modernists Corrupted the Church to Establish Antichrist’s Kingdom. St. Petersburg, Florida: BookLocker.com, Inc.,

Benns, Teresa. 2013. “How I Became Involved in a Papal Election and Supported a Traditionalist Antipope.” Accessed from www.betrayedcatholics.com on 15 February 2023.

Benns, Teresa. 2012. “I Was an Elector in a Conclavist Election Attempt.” Accessed from www.betrayedcatholics.com on 15 February 2023.

Benns, T[eresa] Stanfill. 2009. “No Apostolic Succession, No Pope: Laity Excluded from Election Process.” Accessed from www.betrayedcatholics.com on 15 February 2023.

Benns, Teresa Stanfill, et al. 2009. “Petition: Pope Michael abandon your ‘papal’ claim.” Accessed from www.gopetion.com on 15 February 2023.

Boyle, Terrence J. 2007a. “The Ngo Dinh Thuc Consecrations for Various Groups.” Accessed from www.tboyle.net/Catholicism/Thuc_Consecrations.html on 15 February 2023.

Boyle, Terrence J. 2007b. “The Duarte Costa Consecrations.” Accessed from www.tboyle.net/Catholicism/Costa_Consecrations.html on 15 Fegruary 2023.

Byrne, Julie. 2016. The Other Catholics: Remaking America’s Largest Religion. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cekada, Anthony. 2008. “The Nine vs. Lefebvre: We Resist You to Your Face.” Accessed from www.traditionalmass.org/images/articles/NineVLefebvre.pdf on 15 February 2023.

Cuneo, Michael W. 1997. The Smoke of Satan: Conservative and Traditionalist Dissent in Contemporary American Catholicism. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

“Database of Independent Bishops.” Accessed from www.sites.google.com/site/gnostickos/ on 15 February 2023.

Frank, Thomas. 2004. What is the Matter with Kansas: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Henry, Patrick. 1998. “What do David Bawden and Teresa Benns teach?” Accessed from www.jmjsite.com/what_do_benns_and_bawden_teach.pdf on 15 February 2023.

“He’s Pope For a Small Flock.” 1990. The Kansas City Star, July 23.

Hobson, David. 2008. “From the Depths of Obscurity to the Heights of Blasphemy: An Overview of Saboteur David Bawden.” Accessed from www.todayscatholicworld.com/mar08tcw.htm on 15 February 2023.

Interview with Pope Michael. 2022. Pontifacts pod. Accessed from https://pontifacts.podbean.com/e/interview-with-pope-michael-posthumous-release/ on 15 February 2023.

Interview with Pope Michael. 2010. Accessed from www.kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/12673 on 15 February 2023.

Jarvis, Edward. 2018a. Sede Vacante: The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Thuc. Berkeley: Apocryphile Press.

Jarvis, Edward. 2018b. God, Land & Freedom, The True Story of ICAB; The Brazilian Catholic Apostolic Church, Its History, Theology, Branches and Worldwide Offshoots. Berkeley: Apocryphile Press.

“Kansas Catholic Finds Being Pope Has its Problems/” 1990. Macon Telegraph and News, 7 August.

“Kansas ‘Pope’ Has Few Followers.” 2005. The Salina Journal, May 28.

“Kansas Worshipers Secede, Elects a Pope,” The Miami Herald, 17 August 1990.

Lundberg, Magnus. Forthcoming. Could the True Pope Please Stand Up: Twentieth and Twenty-First-Century Alternative Popes.

Lundberg, Magnus, 2023. ”Habemus Papam: Michael II.” Accessed from www.magnuslundberg.net/2023/08/10/habemus-papam-michael-ii on 16 August 2023.

Lundberg, Magnus. 2020. A Pope of Their Own: El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Second Edition. Uppsala: Uppsala Studies in Church History. E-book. Accessed from www.uu.diva portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1441386&dswid=-556

Lundberg, Magnus. 2016a. “Modern Alternative Popes 17: Linus II.” Accessed from www.magnuslundberg.net/2016/05/15/modern-alternative-popes-18-linus-ii/ on 15 February 2023.

Lundberg, Magnus. 2016b. “Modern Alternative Popes 18: Pius XIII.” Accessed from www.magnuslundberg.net/2016/05/15/modern-alternative-popes-18-pius-xiii/ on 15 February 2023.

Mascarenhas, Lúcio. 2006. “Coronation of His Holiness Pope Michael I.” Accessed from www.lucius-caesar.livejournal/393.html on 15 February 2023.

O’Malley, John W. 2008. What Happened at Vatican II. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Pacheco, Maria Martha. 2007. “Tradicionalismo católico postconciliar, el caso Sáenz y Arriaga,” Pp. 54-65 in Religion y sociedad en México durante el siglo XX, edted by María Martha Pacheco Hinojosa. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México.

“Papal Pretender Twits the Real One.” 1990. Des Moines Register, November 4.

Plummer, John P. and John R. Mabry. 2006. Who are the Independent Catholics? An Introduction to the Independent and Old Catholic Churches. Berkeley: Aprocryphile Press.

Pope Michael. 2020. Will the Real Catholic Church Please Stand Up?: The World Groaned and Found Itself Modernist. Independently Published.

Pope Michael. 2016a. Passion of the Mystical Body of Christ and Resurrection of the Catholic Church. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Pope Michael. 2016b. An Enemy Has Done This: The Infiltration of the Catholic Church. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Pope Michael. 2016c. The Comparative Number of the Saved and the Lost. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Pope Michael. 2016d. “Validity of The Ordination and Consecration of Pope Michael.” Accessed from www.pope-michael.com/old/pope-michael/summary-of-the-position/validity-of-the-ordination-and-consecration-of-pope-michael/ on 15 February 2023.

Pope Michael. 2013a. 54 years that changed the Catholic Church: 1958–2012. Christ the King Library.

Pope Michael. 2013b. What Convinced me that We Needed to Elect a Pope.

Pope Michael. 2011. Upon this Rock: Doctrine of the Papacy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Pope Michael. 2006. Decision on Legitimacy of Orders Among the Traditionalists.

Pope Michael. 2005. Truth is One. Accessed from www.pope-michael.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Truth-Is-One-Original.pdf on 15 February 2023

Pope Michael. 2003. Where is the Catholic Church?

Pope Michael Facebook page. 2023. Accessed from

https://www.facebook.com/PopeMichael1 on 15 February 2023.

Pope Michael website. n.d. Accessed from the www.pope-michael.com on 15 February 2023.

“’Pope’ Says He’s One and Only.” 1990. The Manhattan Mercury, July 19.

“Seminary Study Due.” 1977. The Daily Oklahoman, December 31.

St. Helen Catholic Church. 2023. Accessed from https://www.sainthelencatholicmission.org/ on 15 February 2023.

Sudlow, Brian. 2017. “The Frenchness of Marcel Lefebvre and the Society of St Pius X: A New Reading,” French Cultural Studies 28:79–94.

“The Jayhawk Pope: Kansan’s Papacy Claim Highlights ND Film Fest.” 2008. The South Bend Tribune, January 2008.

The Olive Tree, 2016–2023. Accessed from www.vaticaninexile.com on 15 February 2023.

The Pope Speaks, 2012–2022. Accessed from www.pope-speaks.com and www.vaticaninexile.com/the_pope_speaks.php on 15 February 2023.

Tissier de Mallerais, Bernard. 2002. Marcel Lefebvre: une vie. Paris: Clovis.

Traditional Catechism website. 2023. Accessed from www.traditionalcatechism.com on 15 February 2023.

Vatican in Exile website. 2023. Accessed from the www.vaticaninexile.com on 15 February 2023.

Publication Date:

19 February 2023

Update:

15 August 2023

marry after three dates. They were married in April 1961. After marrying, the Bakkers dropped out and became itinerant Pentecostal evangelists. Especially popular was their puppet show, which Tammy brought to life, giving the puppets voices and personalities. [Image at right]

marry after three dates. They were married in April 1961. After marrying, the Bakkers dropped out and became itinerant Pentecostal evangelists. Especially popular was their puppet show, which Tammy brought to life, giving the puppets voices and personalities. [Image at right]

miniature railroad, paddleboats, a state-of-the-art television studio, and several condominium and housing developments. [Image at right] By 1986, it was one of the most popular attractions in the United States, drawing 6,000,000 visitors that year, third only to Disneyland and Disney World.

miniature railroad, paddleboats, a state-of-the-art television studio, and several condominium and housing developments. [Image at right] By 1986, it was one of the most popular attractions in the United States, drawing 6,000,000 visitors that year, third only to Disneyland and Disney World.

popularly and officially within the state. The achievement of their most important goal (permanent settlement in the Holy Land) has given them a renewed confidence. Indeed, they have become something of a model minority, serving in the army, creating small businesses, spending time with leaders, and receiving much positive coverage since then (Esensten 2019; Esensten website 2023). Both the AHIJ and Israel have benefited from these good relations, and they have sometimes acted as representatives of Israel (for example the Eurovision Song Contest in 1999, and at the Durban World Conference Against Racism in 2001). [Image at right] In April 2021, however, forty-six families whose legal status had not been resolved were issued with deportation orders; these were subsequently postponed after appeal, but the situation has not been resolved as of December 2022.

popularly and officially within the state. The achievement of their most important goal (permanent settlement in the Holy Land) has given them a renewed confidence. Indeed, they have become something of a model minority, serving in the army, creating small businesses, spending time with leaders, and receiving much positive coverage since then (Esensten 2019; Esensten website 2023). Both the AHIJ and Israel have benefited from these good relations, and they have sometimes acted as representatives of Israel (for example the Eurovision Song Contest in 1999, and at the Durban World Conference Against Racism in 2001). [Image at right] In April 2021, however, forty-six families whose legal status had not been resolved were issued with deportation orders; these were subsequently postponed after appeal, but the situation has not been resolved as of December 2022.

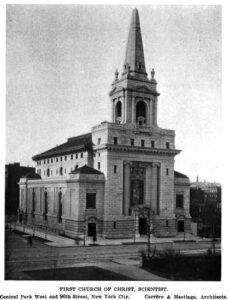

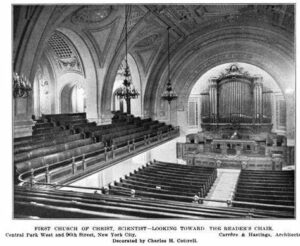

supporting efforts to create new reader groups, and digitizing nearly all relevant historical materials. Like some other religious organizations (for instance, the Church of Scientology or Church of Christ, Scientist), the Urantia Foundation continues to maintain control over its trademarks in both the name “The Urantia Book” and the concentric circles design [Image at right] but has not engaged in active litigation over the marks since the early 2000s.

supporting efforts to create new reader groups, and digitizing nearly all relevant historical materials. Like some other religious organizations (for instance, the Church of Scientology or Church of Christ, Scientist), the Urantia Foundation continues to maintain control over its trademarks in both the name “The Urantia Book” and the concentric circles design [Image at right] but has not engaged in active litigation over the marks since the early 2000s.

Mountain Saints became the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Prairie Saints formed a variety of smaller groups in the subsequent decades, many of them eventually coalescing under the leadership of Joseph Smith III, the oldest son of the founding Mormon prophet (Shipps 2002). Smith III had been a reluctant leader, [Image at right] continually turning down invitations to lead groups in the 1850s until he answered the call of a miniscule Midwestern group calling itself “the New Organization” in 1860. This changed the fate of this group. During his tenure as its leader, the small group, eventually known as the RLDS Church, grew from only 300 members to well over 74,000 by Smith III’s death in 1914 (Launius 1988).

Mountain Saints became the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Prairie Saints formed a variety of smaller groups in the subsequent decades, many of them eventually coalescing under the leadership of Joseph Smith III, the oldest son of the founding Mormon prophet (Shipps 2002). Smith III had been a reluctant leader, [Image at right] continually turning down invitations to lead groups in the 1850s until he answered the call of a miniscule Midwestern group calling itself “the New Organization” in 1860. This changed the fate of this group. During his tenure as its leader, the small group, eventually known as the RLDS Church, grew from only 300 members to well over 74,000 by Smith III’s death in 1914 (Launius 1988). elaborated by Brigham Young’s church in the 1850s and beyond. RLDS believed there would be a temple in Zion someday, but their theology of temples was inchoate. For example, the RLDS Church owned and operated the earliest Mormon temple, the Kirtland Temple in Kirtland, Ohio. [Image at right] The latter structure had been dedicated by Smith III’s father in 1836. However, unlike LDS temples in Utah, RLDS treated the Kirtland Temple much like any other meeting house structure and held public worship meetings in it every Sunday (Howlett 2014).

elaborated by Brigham Young’s church in the 1850s and beyond. RLDS believed there would be a temple in Zion someday, but their theology of temples was inchoate. For example, the RLDS Church owned and operated the earliest Mormon temple, the Kirtland Temple in Kirtland, Ohio. [Image at right] The latter structure had been dedicated by Smith III’s father in 1836. However, unlike LDS temples in Utah, RLDS treated the Kirtland Temple much like any other meeting house structure and held public worship meetings in it every Sunday (Howlett 2014).