VISUAL ARTS TIMELINE

1821 (July 16): Mary Baker, later Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science, was born in Bow, New Hampshire.

1850 (date unknown): Painter James Franklin Gilman was born, possibly in Woburn (Massachusetts).

1874 (June 10): Painter and muralist Violet Oakley was born in Bergen Heights, New Jersey.

1875: Mary Baker published the first edition of her main theoretical work, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which includes several comments on the visual arts.

1879: The Church of Christ (Scientist) was founded.

1893: Mary Baker Eddy started the construction in Boston of the Mother Church, Christian Science’s architectural masterpiece.

1893: Eddy and Gilman published the illustrated book Christ and Christmas.

1893 (December 21): Winifred Nicholson was born in Oxford.

1902-1927: Oakley produced a key work in the history of American muralism by decorating the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg.

1903 (December 18): British painter and muralist Evelyn Dunbar was born in Reading, United Kingdom.

1903 (December 24): Joseph Cornell was born in Nyack, New York.

1910 (December 3): Mary Baker Eddy died in Newton, Massachusetts.

1920: Canadian artist Lawren Harris painted The Christian Scientist, a portrait of his future second wife Bess Housser.

1920: Lawren Harris founded in Toronto the Group of Seven, whose members were either Theosophists, including Harris himself, or Christian Scientists.

1920 (November 5): Winifred Nicholson married in London Ben Nicholson, also a Christian Scientist.

1925: Joseph Cornell converted to Christian Science.

1929: James Franklin Gilman died in Westborough, Massachusetts.

1938: Ben and Winifred Nicholson divorced.

1938 (November 17): Ben Nicholson married in London sculptor Barbara Hepworth, in turn raised a Christian Scientist.

1960 (May 12): Evelyn Dunbar died in Hastingleigh, United Kingdom.

1961 (February 25): Violet Oakley died in Philadelphia.

1972 (December 29): Joseph Cornell died in New York.

1981 (March 5): Winifred Nicholson died in Carlisle, United Kingdom.

VISUAL ARTS TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

“Divine Science, rising above physical theories, excludes matter, resolves things into thoughts, and replaces the objects of material sense with spiritual ideas” (Eddy 1934:123). Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910) wrote these words to indicate the very core of Christian Science spirituality. They could also serve as an aesthetic and artistic program. “The crude creations of mortal thought,” Eddy added, “must finally give place to the glorious forms which we sometimes behold in the camera of divine Mind, when the mental picture is spiritual and eternal. Mortals must look beyond fading, finite forms, if they would gain the true sense of things” (Eddy 1934:123).

Eddy mentioned explicitly the visual arts in her most important work, Science and Health. “The artist,” she wrote, “is not in his painting. The picture is the artist’s thought objectified” (Eddy 1934:310). An artist devoted to Christian Science, she claimed, would be in a position to state: “I have spiritual ideals, indestructible and glorious. When others see them as I do, in their true light and loveliness, – and know that these ideals are real and eternal because drawn from Truth, – they will find that nothing is lost, and all is won, by a right estimate of what is real” (Eddy 1934:359-60).

Christian Science never dictated a formal aesthetics. However, Eddy’s idea that a more perfect divine world existed beyond the illusion of matter guided several artists who were committed Christian Scientists. Each of them translated the Christian Science inspiration into his or her own artistic language. In Eddy’s thought, “once matter is recognised as nothing more than an illusion, (…) it can be transcended, returning the believer to a state of perfect health and harmony with the universe” (Kent 2015:474). Christian Science artists try to depict this state of ideal harmony: a state that, for a Christian Science, is in fact more real than the material illusion of daily life.

NOTABLE MEMBERS ARTISTS

Carline, Hilda (1889-1950). British painter.

Chabas, Maurice (1862-1947). French painter, later a Theosophist.

Cornell, Joseph (1903-1972). American assemblage artist.

Dunbar, Evelyn (1906-1960). British painter and muralist.

Gilman, James Franklin (1850-1929). American painter.

Grier, Edmund Wyly ( 1862-1957). Canadian painter.

Hepworth, Barbara (1903-1975). British sculptor.

Johnston, Frank Hans (Franz) (1888-1949). Canadian painter.

Nicholson, Ben (1894-1982). British painter.

Nicholson, Winifred (1893-1981). British painter.

Oakley, Violet (1874-1961). American painter and muralist.

MOVEMENT INFLUENCED NON-MEMBER ARTISTS

Harris, Lawren (1885-1970). Canadian painter.

Li Yuan-Chia (1929-1994). Chinese painter.

MacDonald, James Edward Hervey (1873-1932). Canadian painter.

INFLUENCE ON ARTISTS

Christian Science built, from its very beginnings, impressive churches. The founder, without imposing one particular style, recommended remaining faithful to the Christian tradition. The first Christian Science churches were neo-Romanic or neo-Gothic, sometimes with Renaissance or classic elements (Ivey 1999). Later, modernist architects were also hired, such as Hendrik Petrus Berlage (1856-1934) for the church in The Hague (Ivey 1999, 200-201). The stained-glass windows o f The Mother Church in Boston [Image at right] were prepared by the local company of Phipps Slocum & Co., under the direction of Christian Science leadership (Pinkham 2009), in a rather conventional style. Some comments emphasized the prevalence of female characters, which was somewhat typical of early Christian Science imagery. The artists, however, were not Christian Scientists.

f The Mother Church in Boston [Image at right] were prepared by the local company of Phipps Slocum & Co., under the direction of Christian Science leadership (Pinkham 2009), in a rather conventional style. Some comments emphasized the prevalence of female characters, which was somewhat typical of early Christian Science imagery. The artists, however, were not Christian Scientists.

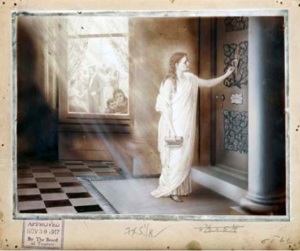

James Franklin Gilman (1850-1929), an itinerant artist who came from Vermont to Massachusetts, was the first professional painter who became a Christian Scientist (Gilman 1935). In 1893, Gilman worked with Mrs. Eddy to illustrate her poem Christ and Christmas (Painting a Poem 1998). The illustrations largely told the story of Mrs. Eddy, although she wrote that they “refer not to personality, but present the type and shadow of Truth’s appearing in the womanhood as well as in the manhood of God, our divine Father and Mother” (Eddy 1924:33).

Christ and Christmas [Image at right] was an extraordinary cooperative enterprise between a religious leader and an artist, as  evidenced by the changes Eddy requested for subsequent editions (Painting a Poem 1998). What Mrs. Eddy sought from Gilman was, at that time, a didactic art illustrating the truths of divine science. But what about an art inspired by Christian Science principles but not directly illustrating its textbook? This was a challenge for a subsequent generation of artists. In 1900, Violet Oakley (1874-1961) started a process that led to her conversion to Christian Science. She was a member for sixty years of her Christian Science church in Philadelphia, where she also served as one of the two readers (i.e. lay ministers conducting the service). Together with Jesse Willcox Smith (1863-1935) and Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), Oakley was one of the three “Red Rose Girls.” All well-off socialites and all pupils of the famous Swedenborgian illustrator Howard Pyle (1853-1911), the three young women decided to live together in Philadelphia’s Red Rose Inn between 1899 and 1901 and to seek a place in a profession dominated by men (Carter 2002).

evidenced by the changes Eddy requested for subsequent editions (Painting a Poem 1998). What Mrs. Eddy sought from Gilman was, at that time, a didactic art illustrating the truths of divine science. But what about an art inspired by Christian Science principles but not directly illustrating its textbook? This was a challenge for a subsequent generation of artists. In 1900, Violet Oakley (1874-1961) started a process that led to her conversion to Christian Science. She was a member for sixty years of her Christian Science church in Philadelphia, where she also served as one of the two readers (i.e. lay ministers conducting the service). Together with Jesse Willcox Smith (1863-1935) and Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954), Oakley was one of the three “Red Rose Girls.” All well-off socialites and all pupils of the famous Swedenborgian illustrator Howard Pyle (1853-1911), the three young women decided to live together in Philadelphia’s Red Rose Inn between 1899 and 1901 and to seek a place in a profession dominated by men (Carter 2002).

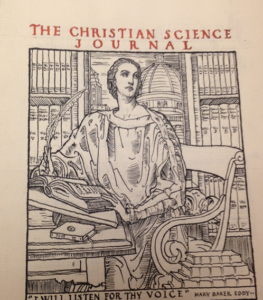

Oakley became famous as the first American woman to receive a public mural commission. [Image at right] The forty-three murals in Harrisburg’s Pennsylvania State Capitol, executed between 1902 and 1927, were masterpieces of American muralism and led to several other commissions. They included the decoration of the Vassar College’s Alumnae House Living Room in Poughkeepsie, New York, where she introduced images dear to Christian Scientists, such as the Woman Clothed with the Sun and the crown of Christian glory (Mills 1984). We read in the main monograph about Oakley that “her firm Christian Science beliefs strongly influenced her life and work” and that art was for her “a way to teach moral values that would elevate the human spirit.” “Sometimes her wholeheartedly devotion [to Christian Science] was refreshing, but some of her associates resented her proselytizing lectures” (The Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee 2002:28)

Yet, we may still ask ourselves in what sense Oakley was a Christian Science artist. She worked for Christian Science publications and painted two portraits of Eddy, now at the Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston. She claimed, however, that Christian Science inspired her non-religious work as well. Oakley considered her best work the mural called Unity, celebrating the end of Civil War and slavery, in the Pennsylvania Senate Chamber. It expressed, she said, “beauty and harmony and inspiration and the effect of these: Peace in the mind of the beholder” (The Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee 2002:133). Some of Oakley’s murals tried to summarize more explicitly the tenets of Christian Science. They include Divine Law: Love and Wisdom, her first mural for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Angels carry the letters forming the words “Love and Wisdom” and the Divine Truth, half-concealed, half-revealed, looms in the background (The Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee 2002:89).

Coincidentally, British Christian Science painter Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1960) also started her career as a muralist, working under her Royal College of Arts teacher Charles Mahoney (1903-1968) in the Brockley County School for Boys, South London. Mahoney and Dunbar’s otherwise close relationship was always plagued by the fact that he was an agnostic, while she was born into Christian Science and very committed to her religion. Hailed as one of the most promising British young painters, in 1940 Dunbar was commissioned to work as the only official UK woman war artist. She focused on the home front and became well known during the war for her realistic and unsentimental paintings, focusing on how the war affected British women. After the war, Dunbar settled in the Warwickshire with her husband, the economist Roger Folley (1912-2008). Folley is depicted in one of her most famous paintings, Autumn and the Poet (1958-1960), typical of Dunbar’s late more metaphorical style.

Dunbar was a very committed Christian Scientist throughout all her life. “Her Christian Science beliefs pervaded much of her work” (Clarke 2006:163). Dunbar herself explained that she wanted to show that “all that is made is the work of God and all is good” (Clarke 2006:163: actually a quote from Eddy 1934:521), even in the most difficult circumstances.

Both Winifred Nicholson (1893-1981) and Hilda Carline (1889-1950) expressed similar feelings towards nature. Carline is mostly well known for her stormy marriage and divorce with fellow painter Stanley Spencer (1891-1959). Critics, however, increasingly recognize her art as a significant voice in British post-impressionism, quite apart from the relationship with Spencer. Carline’s firm belief in Christian Science was not shared by Spencer, and contributed to the crisis of their marriage (Thomas 1999).

Nicholson, a celebrated neo-Impressionist British painter, converted to Christian Science in the 1920s. She attributed to Christian Science her almost miraculous recovery after a fall during her first pregnancy in 1927. Christian Science “gradually became central to her thinking and to her art” (Andreae 2009:66). Nicholson was one of the best colorists in modern British art. She infused new life to the painting of flowers. Her flowers showed the world as the perfect work of God and a demonstration of divine beauty. For instance, Daffodils and Bluebells (1950-1955) is a highly symbolic painting, where the beauty of the flowers directs the gaze towards a church window and divine light.

In 1954, Nicholson wrote in The Christian Science Monitor that these paintings represented “the still order behind turmoil,” “a place where the harmony of space is giving its verdict” (Nicholson 1954). Nicholson did not paint flowers and landscapes only. She found the same spiritual beauty in family life, children, and simple joys of the countryside. By her children’s accounts, “she couldn’t have been a better mother” (Andreae 2009:92) and this loving relationship found a place in her art.

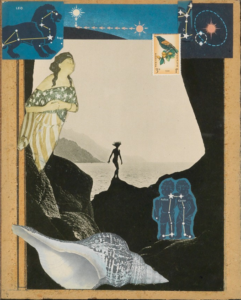

Nicholson also experimented with the abstract as a way of capturing the essence of world’s beauty and goodness as early as  1935. The title of her most well-known non-figurative work, Quarante Huit Quai d’Auteuil, refers to her address in Paris, where she started a lifelong friendship with Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). From the abstract experiments, however, Nicholson consistently returned to flowers. Later in life, she formed a close association with Chinese abstract painter Li Yuan-Chia (1929-1994). Under his influence, she experimented with prisms, producing a whole series of painted meditations about light, a symbol of Christ and of Divine Science dispelling the errors of the mortal mind. [Image at right]

1935. The title of her most well-known non-figurative work, Quarante Huit Quai d’Auteuil, refers to her address in Paris, where she started a lifelong friendship with Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). From the abstract experiments, however, Nicholson consistently returned to flowers. Later in life, she formed a close association with Chinese abstract painter Li Yuan-Chia (1929-1994). Under his influence, she experimented with prisms, producing a whole series of painted meditations about light, a symbol of Christ and of Divine Science dispelling the errors of the mortal mind. [Image at right]

Winifred used throughout her whole artistic career the last name Nicholson, that she acquired at age twenty-six when marrying fellow artist Ben Nicholson (1894-1982), although they were divorced in 1938 after eighteen years of marriage. Ben was also a Christian Scientist, and moved from landscapes to abstract art under the decisive influence of Christian Science and its idea that a perfect world exists beyond the material illusion. He stated repeatedly that without considering the influence of Christian Science, critics would run the risk of not understanding his art at all, and “Christian Science was a driving force in his life” (Kent 2015:474).

After his divorce from Winifred, Ben married sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), who had been raised as a Christian Scientist and kept being influenced by Eddy’s idea about transcending matter in her whole career, although in later years she became closer to the Church of England (Curtis and Stephens 2015).

After she divorced Ben, Winifred Nicholson found a congenial spirit in Mondrian, a very committed Theosophist (Introvigne 2014). Artists who were respectively Christian Scientists and Theosophists often befriended each other, and some went from Christian Science to Theosophy. The Theosophical Society was founded in New York in 1875, only two weeks after the first publication of Science and Health. Both movements were created by women, and found followers in the same urban and progressive milieu. The two teachings were, however, as Stephen Gottschalk (1941-2005) noted, “wholly irreconcilable” (Gottschalk 1973:156). Theosophy’s founder, Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891), attacked Christian Science as a wrong interpretation of human psychic and occult powers, and Mrs. Eddy regarded Theosophy as a particularly malignant form of animal magnetism, i.e. of the malicious attempt to control other human minds.

Notwithstanding this doctrinal conflict, relationships between individual Theosophist and Christian Scientists were often good,particularly in the artistic milieu. The well-known British composer Cyril Scott (1879-1970), who was first interested in Christian Science and later became a Theosophist, claimed that he was introduced to Theosophy through Christian Science friends (Chandley 1994, 38). The French symbolist painter Maurice Chabas (1862-1947) [Image at right] “called himself a Christian Scientist” (Reiss-de Palma 2 004:82) during World War I, before joining the Theosophical Society in 1917 (Reiss-de Palma 2004:93). Christian Science influences, together with his Catholic heritage, help explain the persistence of Christian themes in Chabas’ work well after he became a Theosophist.

004:82) during World War I, before joining the Theosophical Society in 1917 (Reiss-de Palma 2004:93). Christian Science influences, together with his Catholic heritage, help explain the persistence of Christian themes in Chabas’ work well after he became a Theosophist.

A case in point is the Group of Seven, Canada’s most significant twentieth century group of artists. The founder, Lawren Harris (1885-1970), had a Christian Science mother but later moved to Theosophy. Among the members, James Edward Hervey MacDonald (1873-1932) was a Theosophist with a Christian Scientist wife, and Frank Hans (Franz) Johnston (1888-1949), was a Christian Scientist. Harris’ beloved second wife Bess Housser (1891-1969), was a Christian Scientist who later became herself a Theosophist. In 1920, long before they got married, Harris painted her as The Christian Scientist. Almost all members of their circle of friends were either Theosophists or Christian Scientists.

Although firmly committed to Theosophy, Lawren [Image at right] and Bess Harris continued to rely on the key Christian Science  concept of animal magnetism. Harris became concerned that art could inadvertently become a vehicle of animal magnetism, when it tried to influence through symbols. This eventually contributed to the passage from his signature Canadian landscapes to the abstract works of his later years (see Introvigne 2016).

concept of animal magnetism. Harris became concerned that art could inadvertently become a vehicle of animal magnetism, when it tried to influence through symbols. This eventually contributed to the passage from his signature Canadian landscapes to the abstract works of his later years (see Introvigne 2016).

Johnston was the only member of the Group of Seven who “remained a faithful and devout follower [of Christian Science] all his life. He started each day with a prayer and Bible reading” (Mason 1998:21). Johnston was persuaded to join Christian Science by Sir Edmund Wyly Grier (1862-1957), an academic portrait painter who would go on to become in 1929 the president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Although his “traditionalist” style quickly went out of fashion, Grier should be added to the list of recognized artists who were loyal Christian Scientists.

Harris’ implication that somewhat parallel conclusions about the arts may be deduced from Christian Science and Theosophy, as theoretically irreconcilable as the two systems may be, leads us again to the question of what kind of aesthetics an artist may derive from Christian Science. This was a lifelong problem for Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), perhaps the most important Christian Science artist.

Cornell came from a well-to-do New York family, but the premature death of his father when he was fourteen left him as the breadwinner for his family, including mother, two younger sisters, and a brother who suffered from cerebral palsy. Joseph himself was tormented by severe stomach pains.

In 1925, he turned to Christian Science, experienced a significant “physical healing experience” (Starr 1982:2) and became a lifelong active and enthusiastic member of the church (Solomon 1997). Cornell’s journals (Caws 2000) make abundantly clear that Christian Science became a primary interest in his life. He credited Christian Science with “the supreme power to meet any human need” (Doss 2007:122). He turned to art in the 1930s as a way to affirm his faith, and “in 1951-1952 he considered giving up art, if necessary, in favor of working in a more pragmatic matter in the practice of his beliefs” (Starr 1982:1). He started preparing collages and “boxes” in order to “organize the sensual world (the world of matter) into the conceptual realm advocated by Christian Science” (Doss 2007:115).

Mistaken for a Surrealist because of his dreamy boxes, and included in an exhibition of Surrealists at MoMA, the New York Museum of Modern Art, in 1936, he wrote to curator Alfred Barr (1902-1981) that he was not one and did not “share in the subconscious and dream theories of the Surrealists” (Starr 1982:21). For a fervent Christian Scientist, these were dangerously close to animal magnetism. His boxes were not celebrating chaos but imposing order on it (see Blair 1999).

Particularly at the time of the hundredth anniversary of his birth (2003), some critics tried to downplay the Christian Science element in Cornell and his boxes. But in fact “all [his] work is ultimately a variation on the single theme of Christian Science metaphysics” (Starr 1982:2), according not only to interpreters but to Cornell himself. He always described Science and Health as his book “most read of all, exc. Bible” (Starr 1982:1). “To separate Cornell’s aesthetics from the metaphysical ideas to which they bear witness is to deprive the work of its vitality” (Starr 1982:7).

In the assemblage of objects The Crystal Cage (1943), [Image at right] Cornell included references to Charles (Émile) Blondin (1824- 1897), the French acrobat who crossed more than three hundred times the Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Blondin epitomized for Cornell the Christian Science idea that a trained mind can triumph on physical and material limitations. Blondin was forgotten in the twentieth century, but Cornell found a reference to him in Mrs. Eddy’s Science and Health: “Had Blondin believed it impossible to walk the rope over Niagara’s abyss of waters, he could never have done it. His belief that he could do it gave his thought-forces, called muscles, their flexibility and power which the unscientific might attribute to a lubricating oil” (Eddy 1934: 199).

the rope over Niagara’s abyss of waters, he could never have done it. His belief that he could do it gave his thought-forces, called muscles, their flexibility and power which the unscientific might attribute to a lubricating oil” (Eddy 1934: 199).

For the pathologically shy Cornell, the same ability of subduing mental fears was demonstrated by the evolution of ballerinas and actresses before an audience. Ballet, in particular, demonstrated for Cornell the “flexibility and power of the thought-forces called muscles” mentioned by Mrs. Eddy. He was a great collector of ballet memorabilia. Later, Cornell became particularly interested in Marilyn Monroe (1926-1962). He started preparing a “dossier” on her when he learned that she had been raised Christian Scientist, first (shortly) by her mother Gladys Baker (1902-1984) and then for five years by her beloved “Aunt Ana,” i.e. Ana E. Lower (1880-1948), a Christian Science practitioner with whom she lived between 1938 and 1942. As a grown-up, Monroe left the faith. She never acknowledged receipt of a box Cornell sent to her. After her tragic death, however, the artist, in his own words, “experienced a totally unexpected revelation.” He acquired a new certainty of “Christian Science’s faith in the infinity of divine mind, in death as a pathway to eternal life” and came to believe that Monroe attained in death “an escape from the worldly realm of matter; the triumph of divine spirit” (Doss 2007:134-35).

A famous Cornell box, The Pink Palace (1946-1950) was a reference to the Sleeping Beauty fairy tale (and ballet). The princess awakens after hundred years of sleep, yet she has remained young and beautiful. For Cornell, this related to Christian Science teaching about “the error of thinking that we are growing old, and the benefits of destroying that illusion” (Eddy 1934:245). Mrs. Eddy told the story of a British girl who, “disappointed in love in her early years, […] became insane and lost all account of time. Believing that she was still living in the same hour which parted her from her lover, taking no note of years, she stood daily before the window watching for her lover’s coming. In this mental state, she remained young. Having no consciousness of time, she literally grew no older” (Eddy 1934:245). “Years had not made her old, because she had taken no cognizance of passing time nor thought of herself as growing old. The bodily results of her belief that she was young manifested the influence of such a belief. She could not age while believing herself young, for the mental state governed the physical” (Eddy 1934:245).

Cornell’s art ultimately aimed at creating “palaces” free of the limitations of the matter and the mortal mind, where the mental state fully governed the physical. Perhaps, this was the true aim of all Christian Science artists. Although no “Christian science art” as a unified artistic language exists, a common theme in all artists who were either members of, or influence by, Christian Science may perhaps be identified. It is the idea that a different world exists, the world of Divine Mind (not to be confused with the fallible human mind), and that artists are in a unique position for co-operating with Eddy’s grand project by portraying in their works, although with the obvious limitations of the material tools they use, at least something alluding to this higher world.

IMAGES**

** All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

Image #1: The Mother Church, Boston.

Image #2: James Franklin Gilman, illustration for Christ and Christmas with changes approved by Mary Baker Eddy. Courtesy of The Mary Baker Eddy Library, Boston.

Image #3: Violet Oakley, Mary Baker Eddy, cover design for The Christian Science Journal. Courtesy of The Mary Baker Eddy Library, Boston.

Image #4: Winifred Nicholson, Consciousness (1980).

Image #5: Maurice Chabas, Vers l’au-delà – Marche à deux, date unknown.

Image #6: Lawren Harris, The Christian Scientist (1920).

Image #7: Joseph Cornell, Penny Arcade (1962).

REFERENCES

Andreae, Christopher. 2002. Winifred Nicholson. Farnham, United Kingdom and Burlington, VT: Lund Humphries.

Blair, Lindsay. 1999. Joseph Cornell’s Vision of Spiritual Order. London: Reaktion Books.

Carter, Alice A. 2002. The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Caws, Mary Ann, ed. 2000. Joseph Cornell’s Theatre of the Mind: Selected Diaries, Letters, and Files. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Chandley, Paul F.S. 1994. “Cyril Meir Scott and Theosophical Symbolism: A Biographical and Philosophical Study.” Musical Arts Dissertation. Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri – Kansas City.

Clarke, Gill. 2006. Evelyn Dunbar: War and Country. Bristol: Sansom and Company.

Curtis, Penelope – Christ Stephens, eds. 2015. Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World. London: Tate Publishing.

Doss, Erika. 2007. “Joseph Cornell and Christian Science.” Pp. 113-35 in Joseph Cornell: Opening the Box, edited by Jason Edwards and Stephanie L. Taylor. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1934. Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1924. Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896. Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society.

Gilman, James F. 1935. Recollections of Mary Baker Eddy, Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, as Preserved in the Diary Records of James F. Gilman Written during the Making of the Illustrations for Mrs. Eddy’s Poem, Christ and Christmas, in 1893. Reprint. Freehold, NJ: Rare Book.

Gottschalk, Stephen. 1973. The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2016. “Lawren Harris and the Theosophical Appropriation of the National Tradition in Canada.” Pp. 355-86 in Theosophical Appropriations: Kabbalah, Western Esotericism and the Transformation of Tradition, edited by Boaz Huss and Julie Chajes. Be’er Sheva, Israel: Ben Gurion University Press.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2014. “From Mondrian to Charmion von Wiegand: Neoplasticism, Theosophy and Buddhism.” Pp. 47-59 in Black Mirror 0: Territory, edited by Judith Noble, Dominic Shepherd and Robert Ansell. London, England: Fulgur Esoterica.

Ivey, Paul Eli. 1999. Prayers in Stone: Christian Science Architecture in the United States 1894-1930. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Kent, Lucy. 2015. “ Immortal Mind: Christian Science and Ben Nicholson’s Work of the 1930s.” The Burlington Magazine 1348/157:474-81.

Mason, Roger Burford. A Grand Eye for Glory: A Life of Franz Johnston. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn Press.

Painting a Poem: Mary Baker Eddy and James F. Gilman Illustrate Christ and Christmas. 1998. Boston: The Christian Science Publication Society.

Mills, Sally. 1984. Violet Oakley: The Decoration of the Alumnae House Living Room. Poughkeepsie, NY: Vassar College Art Gallery.

Nicholson, Winifred. 1954. “I Like to Have A Picture In My Room.” The Christian Science Monitor, November 9.

Pinkham, Margaret M. 2009. A Miracle in Stone: The History of the Building of the Original Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1894. 2 volumes. Santa Barbara, CA: Nebbadoon Press.

Reiss-de Palma, Myriam. 2004. “Maurice Chabas (1862-1947): Du Symbolisme à l’Abstraction. Essai et catalogue raisonné. ” Ph.D. Dissertation. Paris, France: Université of Paris IV – Sorbonne.

Solomon, Deborah. 1997. Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell. Boston: MFA Publications.

Starr, Sandra Leonard. 1982. Joseph Cornell: Art and Metaphysics. New York: Castelli, Feigen, Corcoran.

The Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee. 2002. A Sacred Challenge: Violet Oakley and the Pennsylvania Capitol Murals. Harrisburg, PA: The Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee.

Thomas, Allison. 1999. The Art of Hilda Carline: Mrs Stanley Spencer. Farnham, England: Lund Humphries.

Post Date:

18 December 2016