AUGUSTA E. STETSON TIMELINE

1842 (day and month unknown): Augusta Emma Simmons was born to Peabody Simmons and Salome Sprague in Waldoboro, Maine.

1866 (August 14): Augusta Simmons married Captain Frederick J. Stetson, a mariner.

1866–1870: The Stetsons sailed around the world, including lengthy stops in such places as Bombay, India.

1870: Capt. Stetson’s health broken, the couple moved to Damariscotta, Maine.

1873: The Stetsons moved in with Augusta’s parents in Somerville, Massachusetts.

1875: Mary Baker Eddy published Science and Health.

1879 (June): Eddy organized the Church of Christ (Scientist) in Lynn, Massachusetts. She moved services to Boston later that year.

1882: Augusta E. Stetson enrolled in Boston’s Blish School of Oratory.

1884 (Spring): Stetson heard Eddy lecture in Charlestown, Massachusetts.

1884 (November): At Eddy’s invitation, Stetson took a two-week class on Christian Science at Eddy’s Massachusetts Metaphysical College.

1884–1885: After she became a Christian Science practitioner (healer) in Boston, Stetson spent several weeks in Skowhegan, Maine and Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, successfully treating sick patients.

1885–1886: Eddy asked Stetson to preach for her on Sundays in Hawthorne Hall, Boston.

1886 (February): Stetson took a Normal class with Eddy to become a teacher of Christian Science.

1886 (November): Eddy sent Stetson to New York City to help introduce Christian Science.

1887 (November 29): Stetson organized what became First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York (hereafter known as First Church).

1890 (October 21): Stetson was ordained as pastor of her church.

1891 (July 24): Stetson opened the New York Christian Science Institute, where she taught classes on Christian Science.

1891 (October): After friction with Stetson, Eddy student Laura Lathrop and others withdrew from Stetson’s church to organize what became Second Church of Christ, Scientist, New York.

1892: Eddy established The Mother Church in Boston.

1894 (December 30): Eddy abolished pastors and ordained the Bible and Science and Health as the church pastors. Stetson became First Reader of her church in New York.

1895: Eddy published her constantly revised Church Manual.

1896 (September 27): Stetson dedicated the first edifice of her church, the 1,000-seat former Episcopal Church of All Souls, located on West 48th Street. For the previous nine years, Stetson’s congregation had worshipped in rented quarters, beginning with a room over a store.

1901 (July 6): Frederick Stetson, still an invalid, died in New York.

1903 (November 29): Stetson opened and dedicated, free of debt, the $1,150,000, 2,200-seat edifice of First Church on New York’s Central Park West.

1908 (November 30): The executive board of Stetson’s church voted to purchase a large lot on Riverside Drive for an 8,000-seat branch of her church, an action that became a violation of Eddy’s Church Manual in 1909.

1909 (July 24): Eddy asked the governing Christian Science Board of Directors of The Mother Church to investigate Stetson. Eddy subsequently asked the Directors to let Stetson’s church handle the case.

1909 (November 4): In a lengthy report, Stetson’s church completely exonerated her of Mother Church charges that included undue control over her students, failure to recognize other branch churches as legitimate, deification of Eddy, and violations of the Church Manual.

1909 (November 18): The Mother Church excommunicated Stetson; she soon resigned from First Church, New York.

1913: Stetson published Reminiscences, Sermons, and Correspondence.

1914: Stetson published Vital Issues in Christian Science.

1918: Stetson founded the New York Oratorio Society of the New York City Christian Science Institute, consisting of her students.

1923: Stetson published Letters and Excerpts from Letters, 1889–1909, from Mary Baker Eddy . . . to Augusta E. Stetson.

1925: Stetson published Sermons Which Spiritually Interpret the Scriptures and Other Writings on Christian Science.

1926: Stetson launched radio station WHAP, which featured nativist programming and concerts by the Oratorio Society.

1928 (October 12): Augusta E. Stetson died in Rochester, New York at the age of eighty-six.

2004: Stetson’s church dissolved itself, merged with Second Church, Lathrop’s former church, to become a newly constituted First Church. The original church building was sold for $15,000,000.

BIOGRAPHY

Augusta E. Stetson [Image at right] was an irrepressible, multi-faceted religious leader who broke new ground for women, garnered deep affection from hundreds of followers, and dealt harshly with competitors. Some scholars have termed her “brilliant, volatile,” a “complicated charismatic character,” and a latter-day apostle, while others have painted her as a “heretic, power grabber, [and] worshipper of Mammon” (cited in Swensen 2008:76). Almost a century after her death, it is time to examine her role as a leader in Christian Science with greater objectivity.

Augusta Emma Simmons was born to Peabody Simmons and Salome Sprague in Waldoboro, Maine in 1842 (day and month unknown). She had a “complete education for her day,” including the local Lincoln Academy, the equivalent of a high school (Cunningham 1994:15). Recognizing her musical ability, her father arranged for her to become the organist of the local Methodist church when she was fourteen. When she was twenty-two, she married Captain Frederick J. Stetson, a middle-aged ship broker, and lived with him in such places as England, India, and Burma. After Frederick’s health deteriorated in 1870, the couple moved to Damariscotta, Maine. Three years later they moved in with Augusta’s parents in Somerville, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston. In 1882, she enrolled in the Blish School of Oratory in Boston to hone her public speaking skills. Her plan was that she would give public lectures to earn money to support herself and her husband, who had become an invalid (Cunningham 1994:13–26).

While in Boston, Stetson learned of Christian Science, a “new Christian identity” (Voorhees 2021:8) recently founded by Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910), to “commemorate the word and works of our Master [Jesus], which should reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing” (Eddy 1936:17). Four years after publishing her textbook, Science and Health (1875), Eddy had founded the Church of Christ (Scientist) in Lynn, Massachusetts with twenty-six followers, moving her services to Boston later that same year (Swensen 2018:92–93). After disbanding her first unruly Boston church in 1889, Eddy founded the centralized Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, three years later. Proclaiming that both men and women were perfect children of a perfect God, Eddy affirmed, “We have not as much authority in science, for calling God masculine as feminine, the latter being the last, therefore the highest idea given of Him” (Eddy 1875:238; Hicks 2004:47). This was a striking idea, but it was not entirely new. According to historian of religion Elaine Pagels, the Holy Spirit was originally conceptualized as a “feminine spirit” or the “Motherly” side of the divinity (Pagels 2006:8). Eddy built her healing faith around the concept of Father–Mother God.

When Stetson first heard Eddy lecture in Charlestown, Massachusetts in 1884, she knew she had found her niche. As Stetson later described her reaction to Eddy’s preaching: “I there caught a glimpse of the power of the Christ-mind, and its application to sin and sickness, the power which Jesus utilized, and which he taught to his disciples” (Stetson 1913/1917:852). According to scholar of religion Rosemary R. Hicks, Eddy encouraged women to “resume the mantle of healing that institutional medicine had usurped and to take leadership positions in ministry and education” (Hicks 2004:58). As scholar of religion Sarah Gardner Cunningham observes about Augusta E. Stetson, “Christian Science offered a coterie of discerning women of some social refinement, an opportunity for a kind of status and economic independence as a Christian Science practitioner [healer] and teacher, and spiritual treatment for Frederick and for herself” (Cunningham 1994:27). Because of her forceful personality, Stetson quickly became known as “Fighting Gus” (Strickler 1909:175).

When Eddy asked Stetson to go to help introduce the faith to New York City in 1886, she initially hesitated to leave familiar surroundings and venture into a large and strange city. Yet Stetson took the plunge and journeyed to the Empire City. “As here and there an individual member of a family embraced the healing truth,” she recalled, “households were gradually drawn into the fellowship of the new joy of spiritual dominion” (Stetson 1914/1917:105). Largely spearheaded by newly liberated women, Christian Science began its rapid ascent primarily because of healings of physical ailments. Proving herself an effective healer who often brought about instantaneous cures, Stetson exulted to Eddy, “The healing is astounding” (Stetson 1894).

Stetson soon began to attract attention. In 1894, one local journalist reported that she maintained that “woman is better fitted than man to fill the pulpit, because she expresses the highest order of humanity” (Unattributed clipping 1894). After renting space for services for almost ten years, in 1896 Stetson purchased the 1,000-seat building of a former Episcopal Church on West 48th Street. In an article entitled “Christian Science Churches Thronged,” one local reporter described a Sunday service at Stetson’s church: “Beautiful women richly gowned, superb in beautiful coloring, swept up and down the aisles, stopping here and there chatting in groups, in twos and threes, and well[-]groomed men taking their part in what was more like a reception at a Fifth Avenue mansion than the ending of a religious service” (quoted in Cunningham 1994:82). Biographer Gillian Gill writes that Stetson had “managed to project the image of a stylish, cultured woman that appealed to New York’s nouveau riche population” (Gill 1998:534). Scholar of Christian Science Stephen Gottschalk observes that Stetson was a “precursor of a tendency among some Christian Scientists to live out an uneasy compromise between the rhetoric of spirituality and the reality of a subtle—and sometimes not so subtle—materialism” (Gottschalk 2006:379).

All members of Stetson’s loyal inner circle were grateful for the healings they experienced through her work. One of her first patients was Edwin F. Hatfield, a former railroad executive and scion of distinguished Presbyterian clerics in New York, who was “quickly healed of nervous prostration, which physicians had failed to relieve” (Stetson 1913/1917:21). Hatfield became the chairman of the board of Stetson’s church for almost twenty years. George F. DeLano, a successful New York lawyer, rejoiced that he had “discovered the Principle of healing that had brought my wife and myself from a state of chronic invalidism to perfect health” (First Church, New York Trustees Minutes 1903). Both William Taylor of Scranton, Pennsylvania, who owned several stores and had large mining interests, and his wife had been healed by Stetson and were her fervent followers since about 1895. “Both had been invalids. . . . Both are perfectly well now and have been all this time. They trust everything absolutely to Principle, their children, health and business” (Alexander 1923–1939, 1:108). Stetson drew into her fold many affluent people, as well as those of more limited means (Swensen 2008:84; Swensen 2010:12-14; Johnston 1907:161).

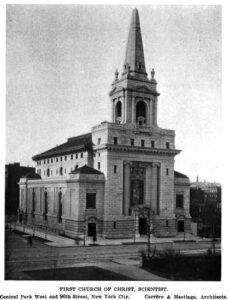

Attendance at Stetson’s church skyrocketed, necessitating larger quarters. After four years of planning and cutting no corners with funds freely contributed by her church members, Stetson’s $1,150,000 majestic Beaux Arts edifice on Central Park West at 96th Street, [Image at right] designed by the renowned architectural firm of Carrere and Hastings, was completed late in 1903. Built of New Hampshire granite (from Eddy’s home state) with its steeple visible across Central Park, the structure boasted walnut pews capable of accommodating 2,200 worshippers, marble floors, and a large stained-glass window by the celebrated American artist John La Farge (see Swensen 2008:84). Just before the opening and dedication, Stetson wrote to Eddy, “We are ready at last to dedicate the church edifice which our love and gratitude have erected as a tribute to you. It is not necessary for me to tell you what this means to me—you know it all—the long and perilous passage, the fears and foes within and without, and the opposition of envy and all evil” (Stetson 1913/1917:170).

There were concerns about Stetson’s embrace of wealth, fashion, and materialism. Annie Dodge, a member of Stetson’s church, reported to Eddy, “Everything here seems to be frills and frothiness” (Dodge 1901). A few months before her church building was completed, Eddy warned Stetson:

Your material church is another danger in your path. It occupies too much of your attention it savors of the goddess of the Ephesians, the great Diana. O turn ye to one God. . . . I had hoped the interval from Readership would give you a great growth in healing and this is needed more than all else on earth (Eddy 1903, underline in original).

After Eddy suggested three-year terms for branch church Readers in 1902, Stetson was slow to accept this new Church Manual bylaw. In 1905, Eddy again urged, “What I need for help in my life-labor more than all else on earth is a—healer such as I were when practising. I beg and pray that you become that” (Eddy 1905).

By 1908, attendance was so great at Stetson’s church that there were 200 to 300 people standing during the Sunday morning service. Late that year the church trustees voted to purchase a large lot on Riverside Drive to build an 8,000-seat branch church there (Peel 1977:334), which flouted Eddy’s rule that only The Mother Church in Boston could have branch churches (Eddy 1936:71). Annie Dodge warned Eddy that Stetson and “her ‘dupes’ might start a Church . . . which to all appearances would be a branch of the Mother Church in Boston, but in reality would be only a branch (or Annex) of First Church here” (Dodge 1909, underline in original). Thus, Stetson was viewed as challenging Eddy and The Mother Church, although Stetson always claimed she was following Eddy.

In the summer of 1909, at Eddy’s request, the governing Board of Directors of The Mother Church (composed of five former successful businessmen) began an investigation of Stetson and her leadership and institutions. Charges included domination of her students, that she labelled all other branch churches, at least in New York City, as illegitimate, that she deified Eddy, and that she violated the Church Manual. On November 18, 1909, after Stetson and sixteen of her practitioners were examined by the Directors in Boston, Stetson was excommunicated from The Mother Church. Four days later she resigned from First Church, New York.

After her ouster, Stetson actively continued her work, maintaining her loyalty to Eddy, claiming that Eddy had chosen her to carry on true Christian Science, and indefatigably defending herself. In 1913, she published Reminiscences, Sermons, and Correspondence Proving Adherence to the Principle of Christian Science as Taught by Mary Baker Eddy, which included her autobiography, sermons, articles, and letters to and from students. As she wrote to a friend in the year the volume was published:

I must, as an [sic] historian, give to the world a record of the events which occurred when the separation came, between the Christian Scientists who composed the material organization, and the advanced Christian Scientists who had risen to the spiritual interpretation of the text-book of Christian Science, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, and our revered Leader’s other writings (Stetson 1913/1917:1176).

Stetson’s publication in the following year of Vital Issues in Christian Science was intended to counter “continued denunciation of my teaching by the constituted authorities of the material organization [The Mother Church]” (Stetson 1914/1917:362). This volume contained The Mother Church charges against her and excerpts of testimony at the Directors’ hearings, with her attempted refutations of all accusations. In 1923 she published Letters and Excerpts from Letters, 1889–1909, from Mary Baker Eddy . . . to Augusta E. Stetson, which contained only Eddy’s positive comments and omitted all of Eddy’s efforts to counsel and correct her student. The next year, Stetson published Sermons Which Spiritually Interpret the Scriptures and Other Writings on Christian Science, the “last of Stetson’s scrap-book type collections” (Paulson, Mathis, Bargmann 2021:200).

Of Stetson’s estimated 800 students, about half remained staunchly loyal to her after her ties to the organized Christian Science movement were severed. As Arnold Blome, Stetson’s student, wrote to her, “I am sure you know, but I had not fully realized, what grateful, loving, generous students you have until I began to gather the sheaves” (Blome 1918). Her students reverently addressed her as “Teacher.” Stetson’s student Amy R. Lewis affirmed, “You are a Rock in the Temple of Love” (Lewis 1923). Some Christian Science writers, including Robert Peel, have failed to note the devotion that Stetson’s students felt toward her. In 1920, when New York’s First Church tried and failed to excommunicate Stetson loyalists, the struggle was front-page news (New York Herald 1920:1).

In addition to her many administrative accomplishments, Stetson was a published poet and song writer. In 1918 she founded the 300-member New York Oratorio Society of the New York City Christian Science Institute, largely consisting of her students, who sang recognized and new sacred works and her songs, including General Anthems: Light the Torch and Our America: National Anthem. As she remarked to an interviewer from Musical America, “Only those who undertake the work of community singing under the inspiration of a divine purpose will succeed in the hearts of the people” (Stanley 1917:11). During the 1920s, Stetson’s radio station, WHAP, broadcast nativist and Ku Klux Klan political commentary and concerts by the Oratorio Society, sometimes accompanied by members of the New York Philharmonic Society. Stetson’s commitment to oratorios stood in contrast to the organized Christian Science movement, since Eddy had abolished choirs in 1898 at The Mother Church and at branches about two years later.

Although Stetson asserted that she would live forever, she passed away on October 12, 1928 in Rochester, New York at the age of eighty-six. In 2004, with its attendance down to a handful, First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York disbanded, sold its Beaux Arts edifice for $15,000,000, and merged with Second Church to form a new First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York.

According to Cunningham, “Stetson never accepted the changed corporate character of the church. She refused to abandon the intimate, interpersonal, nineteenth-century vocabulary and feminine frame of reference that characterized her original understanding” (1994:9). For former Mother Church Director and Eddy biographer John V. Dittemore (1876-1937), Stetson “lacked her leader’s capacity of growth. She always remained at the standpoint of 1884” (Bates and Dittemore 1932:442). Stetson’s highly successful effort to build up her church and secure the love and loyalty of hundreds of her pupils was a notable accomplishment, but it was hobbled by her intractability, which led directly to her downfall at the hands of five male Directors of The Mother Church.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Stetson wrote, “I am like a mathematician who stands before the blackboard working out a mathematical conclusion. The audience is the world, interested only in the solution” (1914:646). From the time Stetson arrived in New York City in 1886, she taught students about Christian Science. After the founding of the New York Christian Science Institute in 1891, she organized her teaching more methodically and, until forbidden by Eddy, tried to teach classes in other cities. Following Eddy’s Church Manual, first published in 1895, Stetson taught one class of up to thirty-three students annually, called “Class Instruction.” (In 1899, Eddy decreased the number of students per annual class to thirty.) Here is how Stetson’s devoted student Stella Hadden Alexander described her 1901 class:

It is a wonderful class, 13 men, all middle aged, scholarly or business men, many of them deep thinkers, as you can see from the discussions in class, their answers to Mrs. Stetson’s questions, and their questions to her (Alexander 1923–1939, 1:102).

Alexander exulted to her mother that she had found a “new and beautiful view of life” (Alexander 1923–1939, 1:96). Soon afterward she wrote to her parents, “Oh! How great Christian Science is! How it unites people! The church seems like one great family” (Alexander 1923–1939, 1:104). Writing shortly after Stetson’s passing, Lutheran clergyman and historian Altman K. Swihart reported that “Mrs. Stetson’s loyal students held her in affectionate, reverential esteem” (Swihart 1931:70).

As Stetson claimed, “In my teaching and practice I am closely following the textbook of Christian Science [Science and Health], as I have done for twenty-five years” (Stetson 1913/1917:643). In 1909, Stetson wrote to Eddy,

I have taught my students to look straight at and through the brazen serpent of false personality, and to behold the immortal idea, man, where the mortal seems to be. Malicious animal magnetism still persists in its efforts, by its indiscriminate denunciation of personality in general, to slay the spiritual idea, Christian Science, to which you have given birth (Stetson 1913/1917:227).

Stetson’s teaching of obstetrics was unusual, and in some ways, protofeminist, but it strayed beyond Eddy’s boundaries. “To attend properly the birth of the new child, or divine idea,” Eddy wrote, “you should detach thought from its material conceptions, that the birth will be natural and safe” (Eddy 1934:463). The typed text of Stetson’s “Obstetrics” lesson consists of class notes taken by a student. “There is but one Mother [God],” Stetson declared, “and Her law is the only law of harmony, peace, purity, immortality” (Stetson n.d.:2). Speaking metaphysically, she denied the existence of male and female genitalia, maintaining that there was no sex, fertilized egg, race, gender, or sexual intercourse (Stetson n.d.:12). As Stetson taught, “There is no matter—no male or female—no material conception—no foetal growth—no material man—no male or female baby—no baby to lose—no belief of baby” (Stetson n.d.:12; see also Bates and Dittemore 1932:365).

For Stetson, Eddy was the female Christ or “Messiah,” a characterization that Eddy repeatedly rejected. “But darling,” Eddy warned, “you injure the cause and disobey me in thinking that I am Christ or saying such a thing” (Eddy 1900b; Thomas 1994:274). Stetson’s students, such as Arnold Blome, continued to assert that Jesus epitomized the “fatherhood of God,” while Eddy represented the “motherhood of God” (Blome 1918). One year before she passed, Stetson reaffirmed, “To me Mrs. Eddy is the motherhood of God as Jesus was the fatherhood. God is both father and mother” (New York Times 1927:10).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The Christian Science movement was built on healing. A remarkably successful healer, this portion of Stetson’s work was increasingly sidelined by her close attention to her church and students. Nevertheless, healing was an important aspect of Stetson’s New York City church. The healing activities were mentioned in a copy of her extemporaneous address to her church on Thanksgiving Day 1908 that she sent to Eddy. During this address, Stetson mentioned the “practitioners [in her church] who are healing the sick and awaking the sinner, and church members whose service of time and money has been a work of love” (Stetson 1913/1917:156). More than 45,000 people a year visited the Christian Science Reading Room located in the First Church, New York building; of 4,523 cases of illness treated by the twenty-five practitioners on duty, over 3,000 were “healed or permanently benefitted” (Strickler 1909:257; First Church, New York 1909b).

Despite her other interests, Stetson continued to be an exceptional healer. “I am moved to write you,” she reported in a letter to Eddy in 1904, “in regard to a case to which I was recently called, that, during two years, had been diagnosed by thirteen physicians, and treated as malignant cancer.” Stetson recounted:

The healing went on, and the cancer passed off gradually day by day as painlessly and as freely as if removed by a surgeon’s knife, until in two weeks there was no evidence of the disease except the after effects” (Stetson 1913/1917:173).

There were two or three relapses (the patient was allegedly once “pulseless” for sixteen hours), but Stetson claimed that the healing was complete (Stetson 1913/1917:175).

Stetson encouraged social and cultural events among her students, including recitals and dramatic productions, which were sidelined by other Christian Science teachers. Stetson informed Eddy that she did not have time to attend cultural events, but her church was a beehive of activities, which were reduced when Eddy frequently limited the bustle of branch churches through her evolving Church Manual. Such restrictions included evicting the 25 practitioners who had small offices on an upper floor of Stetson’s church (Eddy 1936:74). The approximately 75 linear feet of records of First Church, New York at the Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston demonstrate the many cultural activities and social events that were associated with Stetson and her church. These records might offer branch churches today at least a few ideas about how to fill their empty church auditoriums (see Baxter 2004:110).

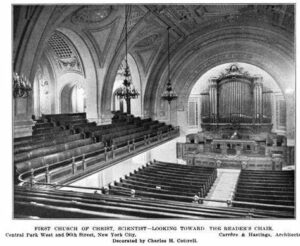

Sunday services and Wednesday testimony meetings at Stetson’s church were moving and dramatic. [Image at right] In 1906, she wrote to Eddy:

How often during the church services I wish you could see the great congregation, and hear the testimonies of the people, of wonderful deliverance from sin, sickness, sorrow, and death, and their appreciation of your great work, and of your book, Science and Health; and could hear your words in your hymns ring out from hundreds of voices, which fill the lofty dome until the music seems to blend with the unseen angel choir and the great organ of eternity swells its diapason in Te Deums of praise to God for your ministry to mankind (Stetson 1913/1917:181).

Mary Pinney, a Stetson student who commanded the 66-rank, four-manual Hutchings–Votey organ, was probably the only female organist at a large church in New York City. The congregation would rise as Stetson entered the sanctuary, a practice that ran counter to Eddy’s disdain of “personality.”

Since Stetson claimed that her branch church was paramount in New York City, she held it aloof from other Christian Science branch churches in the city, even refusing to participate in a joint Christian Science Reading Room. According to Stetson, “branch churches originating in qualities other than unity and love cannot properly be regarded in the spiritual sense as legitimate Christian Science churches.” That is, Stetson viewed all other branch churches in New York City as “schismatic” (Stetson 1914/1917:307).

LEADERSHIP

According to Swihart, Stetson sought personal fealty from her followers, whereas Eddy required obedience through her Church Manual. In common with Eddy, Stetson chose loyal men to run her church, which “became a marvel of efficiency and of attachment to the dominating figure who controlled all its activities” (Swihart 1931:57). Stetson’s control of her church exasperated Eddy. Many of the bylaws in Eddy’s evolving Church Manual, including her decision to abolish pastors and establish lay readers, were directed partly at Stetson. In a Christian Science congregation, two Readers alternately read passages from the Bible and Science Health, these texts being designated the pastors of the Church of Christ, Scientist in the Church Manual (see Peel 1977:32-33; Gottschalk 2006:226-228). Eddy later limited the terms of Readers to three years, another move aimed at curtailing Stetson’s authority in her church. Despite these strictures, Stetson repeatedly claimed a special relationship with Eddy, prompting the latter to write to her, “Do not claim that you are my chosen one for you are not” (Eddy 1893b). Yet, as Stetson later wrote to Eddy, “You and I seem to be held up to the world together but all the fiery darts of the enemy fail to separate us” (Stetson 1897).

One contemporary magazine characterized Stetson as possessing “unbreakable reserve power” (Johnston 1907:159). The methods Stetson employed, however, produced strong ripples of discontent among Eddy’s adherents in Stetson’s New York City flock. “I took Mrs. Lathrop from your church to rescue her from oppression,” Eddy wrote to Stetson. “You would not allow her to speak in your meetings nor allow your students to attend hers on penalty of leaving your church” (Eddy 1895). As Eddy had previously written to her adopted son, “The misunderstanding carried out between Mrs. Stetson and me is a sure sign of . . . the disruption of all our expectations” (Eddy 1893a, underline in original). Trying to rein in her headstrong yet talented student, Eddy was extraordinarily patient, often calling her “darling” in letters and repeatedly asking her to purchase bonnets and dresses for her in New York City (Peel 1971:177; Peel 1977:331; Gottschalk 2006:368–71).

Stetson’s influence in the Christian Science movement extended far beyond New York City. Three branch churches were essentially branches of First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City through close connection between Stetson and her students: Albany, New York; Wilmington, North Carolina; and Cranford, New Jersey (Strickler 1909:208). Her students were also very active in places such as Atlanta, Georgia; Butte, Montana; and, until 1898, Portland, Oregon. Despite Eddy’s repeated denials, Stetson believed that she would succeed Eddy as leader of the denomination (Peel 1977:332; Gottschalk 2006:371).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Eddy once observed to Stetson, “You have always been the most troublesome student that I call loyal. . .” (Eddy 1897a). Stetson’s alleged domination of members of her congregation caused the defection from her orbit of her close follower and former assistant pastor Carol Norton in 1897. Eddy warned Stetson that, if she did not cease her “mad ambition,” the “blow will at length fall and ‘the stone that you reject will grind you to powder’” (Eddy 1897b). At the very time Stetson’s imposing church edifice opened in 1903, one disaffected member remarked, “Here you are confronted by a sort of mental Mafia and mental assassination” (New York Times 1903:5). Social historian Robert David Thomas notes Stetson’s “divisiveness” (Thomas 1994:268), while Gill describes Stetson as a “troublesome healer” (Gill 1998:537). Those who opposed Stetson’s wishes and exhibited “refractory” behavior were ostracized or even excommunicated from her church, including the future First Reader of The Mother Church, William D. McCrackan (1864–1923), who broke with Stetson in 1906 (Swensen 2010:7).

After reports of the proposed branch church on Riverside Drive appeared in the press early in July 1909, Stetson sent to Eddy a composite letter, consisting of brief, laudatory statements about her by her students. In this letter, Arnold Blome exclaimed to Stetson, “Your perfect life, [is] fast approaching the perfect idea of Love,” while Kate Y. Remer exulted, “You have taken us back into the real garden of Eden” (Stetson 1909:2). Shaken by the composite letter, Eddy asked the Mother Church Directors to start an investigation of Stetson, call her to Boston for questioning, and threaten expulsion from the church if she did not desist from her headstrong views and practices (Peel 1977:336–43; Gottschalk 2006:371–79; Bates and Dittemore 1932:432–33). Although Eddy tried to reason with Stetson, she asked Archibald McLellan, editor of the Christian Science periodicals and a Director, to write a “clear strong statement of The Mother Church’s rebuke of Augusta E. Stetson’s stuff published in the name of Christian Science” (Eddy 1909a).

Virgil O. Strickler (1863-1921), First Reader of Stetson’s church and a former Omaha attorney and Populist Party leader, kept a diary after Stetson invited him to her two-hour daily meetings with her inner circle of practitioners in January 1909. According to Strickler, Stetson claimed that the other New York City Christian Science churches were not legitimate, that these “organizations had to die” (Strickler 1909:54), and warned that Laura Lathrop (1845–1922) should stop fighting her. “If you [Lathrop] are not right you must go out, and the quicker you go out the better, and the more you suffer the better” (Strickler 1909:187, underline in original). Stetson threatened that “If Archibald Mclelland [sic] does not look out he will go six feet under the ground” (Strickler 1909:189), and declared that, since “the Mother Church is in in the hands of the devil,” it must wither and die (Strickler 1909:208–09). After Stetson returned from meeting with the Directors, Strickler described her as “almost hysterical,” claiming that “it was not her that took them [Directors/Lathrop] up; that it was the human that said those things and that the human was not her real self” (Strickler 1909:277). Stetson was claiming that her perfect self, in God’s image (see Gen. 1:27), did not utter those threats. Unaware of these comments, in early August Eddy instructed the Directors to let First Church, New York handle the matter of Stetson’s church leadership, in accordance with the Church Manual.

When Strickler showed his diary to the Mother Church Directors on August 30, 1909, they were “simply overjoyed and speechless that at last Mrs. Eddy and themselves were to have the truth about the hidden mysteries of First Church of New York City” (Strickler 1909:306). When the Directors reported the contents of Strickler’s diary to Eddy, she asked them to deal with Stetson’s “impious conduct” (Eddy 1909c). Now thoroughly exasperated with Stetson, Eddy warned her that she was “dark in your perception of me and my thoughts” (Eddy 1909b). During the Directors’ questioning of sixteen of Stetson’s practitioners, it was revealed that Stetson and some of her students had lied under oath to ensure that First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City received $60,000 in the case involving the contested will of Helen C. Brush in 1901 (Gill 1998:513). Almost all of the sixteen practitioners remained loyal to Stetson and followed her out of the organized Christian Science movement. As Eddy wrote to the Directors, “if it can be done safely, drop Mrs. Stetson’s connection with the Mother Church. Let no one know what I have written to you on this subject” (Eddy 1909d).

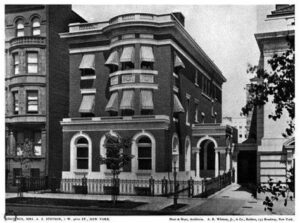

Yet Stetson, who lived in a townhouse adjacent to the church edifice she had built, [Image at right] remained influential in her congregation. At a tumultuous meeting of First Church, New York City on November 4, 1909, a report of over 1,000 pages, written by members of Stetson’s inner circle and including detailed interviews with many church members, found her innocent of all charges (see First Church, New York 1909a). As Strickler recorded the scene at the meeting, “The report precipitated a riot. For six hours people yelled and shouted and otherwise behaved themselves like so many wild indians [sic]” (Strickler 1909:327). Eddy condemned the “disgraceful revolt in Stetson’s Church. . . . Mrs. Stetson . . . will awake to the thunders of Sinai. . .” (Eddy 1909e). On November 18, 1909, after six intense hours of cross-examination by the Directors spread over three days, Stetson was excommunicated from The Mother Church. Four days later she resigned as a member of the church she had founded and guided for twenty-three years. In January 1910 at a contentious annual meeting of First Church, New York, urged on by Eddy, members decisively defeated Stetson’s slate of officers (Bates and Dittemore 1932:439-42). Stetson continued to live in her townhouse and regularly meet with her loyal students until her passing in 1928.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Augusta E. Stetson was one of Mary Baker Eddy’s “newly empowered women” who introduced Christian Science and its gospel of healing to the public, but she became an obstacle to Eddy’s plan to subjugate “‘personality’ and place her movement under successful men acceptable to patriarchal culture” (Swensen 2008:75, 76). [Image at right] Since Stetson often stated that she was brave and constantly had to defend her church, Eddy once responded with exasperation, “You are brave but you are a woman in the eyes of men. . .” (Eddy 1900a). That is, Eddy was concerned that Stetson did not seem to realize or care that she was operating without self-restraint in a patriarchal culture and that opposition was increasing against her from both men and women. Eddy was well aware of the social opposition that she and Christian Science faced (Peel 1977:194–97, 200–02, 229–33; Gottschalk 2006:17–20, 46-47, 260–82; Bates and Dittemore 1932:372, 378, 384, 403–18). Even the New York Times referred to Eddy as the “High Priestess” of a “pestilent cult,” and charged that the “Christian Science type” was a “mushy-brained” and “imperious female” (New York Times 1904, quoted in Swensen 2008:83)

Yet Stetson continued to reject patriarchal dominance. “Down through the line of commutual thought,” she reasoned, “women have responded to the divine interpretation and are demanding emancipation from man-made laws and mental slavery” (Stetson 1913/1917:715). As she wrote in a letter to the press:

The story as told by Luke shows that Jesus was visible to the women, but that, although Peter and other men went to the sepulchre, and found that the material body of their Master was not there, they failed to recognize the spiritual man—“Him they saw not” (Stetson 1913/1917:955).

Stetson was even more explicit about the scriptural role of women: “It was the woman in Revelation who was to be clothed with light to interpret the Word of God” (Stetson 1913/1917:87). Here Stetson was unabashedly claiming that Eddy was that “woman clothed with the sun” (Rev. 12:1–2). She was not alone in asserting this view of Eddy (Thomas 1994:271-273).

Religion scholar Susan Hill Lindley has written that “any potential rivals [to Eddy] who arose, most notably her disciple, Augusta Stetson, were ruthlessly cut off” (Lindley 1996:270). Lindley is correct that Eddy saw herself as the only “Leader” of her movement, but both Stetson and the Mother Church Directors acted in a heavy-handed manner. According to Mother Church spokesman Alfred A. Farlow (1860-1919), Stetson’s expulsion was an “act of discipline” (Farlow, 1909, quoted in Swensen 2020:39). Another powerful woman was also cast aside at this time. Dittemore told Strickler that the Board of Directors had recently investigated a “large church where a woman was to all appearances as strongly intrenched as Mrs. Stetson is in First Church [New York].” The Directors engineered her ouster “within the space of 48 hours” (Strickler 1909:245). Since Eddy “looked to [professional] men as the public face of Christian Science” and depended on self-effacing women to “build the movement from the ground up” (Gottschalk 2006:185), Stetson’s towering presence and her polarizing efforts constituted a severe threat to that strategy.

Stetson’s expulsion marked the beginning of the Mother Church Directors’ campaign to achieve corporate-style centralization, conformity, and unity in the Church of Christ, Scientist denomination, a process that included both men and women. This process gained momentum after Eddy’s death late in 1910. By 1912, Farlow, who had been for many years the powerful and independent Manager of the Committees on Publication for The Mother Church, found himself “by no means as influential as he was” (Hendrick 1912:482). He became ill, took a lengthy leave of absence, and resigned his post in 1914 (New York Tribune 1914:1). (In 1900 Eddy had instituted state Committees on Publication—two for California—to act as watchdogs to protect the movement from clerical, medical, and legislative threats.) In 1922, the Directors further consolidated their authority when they expelled the three independent-minded male Trustees of the Christian Science Publishing Society after a protracted and bitter lawsuit in 1919–1921, dubbed the “Great Litigation” (Swensen 2020:40–46). In 1919, the Directors fired the uncooperative Dittemore and replaced him with Eddy student Annie M. Knott (1850–1941), the first woman to serve on the Board. At the start of the legal proceedings, Stetson noted, “Now there is another trial in Boston. We see verified the words in Psalm 7:15” (quoted in Cunningham 1994:198). This verse reads “He made a pit, and digged it, and is fallen into the ditch which he made” (KJV). Therefore, the jettisoning of Stetson was part of a major restructuring of the Christian Science movement (Swensen 2020:49).

Superb organizer, builder of the celebrated Beaux Arts church edifice in New York City, successful healer, gifted speaker, talented poet, and writer of spiritual music, was, for a time, a model of a successful woman religious leader. Beloved by her students, she nonetheless fell by the wayside when her assertive behavior threatened the controversial church organization that Eddy and her male Directors were building. Stetson’s numerous accomplishments invite further study, and a place in the history of the world’s religious leaders.

IMAGES

Image #1: Augusta E. Stetson (1842-1928). Courtesy of Library of Congress, #94508910.

Image #2: First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, Central Park West and 96th Street. Carrere & Hastings, Architects. Photo Architectural Record, January 1904. Copyright expired.

Image #3: Interior of the First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, Central Park West and 96th Street. Carrere & Hastings, Architects. Decorated by Charles H. Carttell. Photo Architectural Record, January 1904. Copyright expired.

Image #4: Residence of Augusta E. Stetson, New York City. The rear of the edifice of First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City is pictured to the right. Hunt & Hunt, Architects. Copyright expired.

Image #5: Portrait of Augusta E. Stetson in 1908 wearing a pin consisting of a portrait of Mary Baker Eddy encircled with diamonds and set in gold, which Eddy gave to Stetson in 1898. On the back of the pin is engraved, “Mother, 1898.” Library of Congress. See Longyear Museum, https://www.longyear.org/learn/research-archive/a-miniature-portrait-of-mary-baker-eddy-finds-its-way-to-longyear-museum/.

REFERENCES

Alexander, Stella Hadden. 1923–1939. “Illuming Light: Glimpses of Home and Records.”Three Volumes. Typescript. Union Theological Seminary (hereafter cited as UTS).

Bates, Ernest Sutherland, and John V. Dittemore. 1932. Mary Baker Eddy: The Truth and the Tradition. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Baxter, Nancy Niblock. 2004. Open the Doors of the Temple: The Survival of Christian Science in the Twenty-first Century. Carmel, IN: Hawthorne Publishing.

Blome, Arnold. 1918. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, December 11. Subject File (hereafter cited as SF), Augusta E. Stetson. Mary Baker Eddy Collection, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, Boston, Massachusetts (hereafter cited as EC).

Dodge, Annie. 1909. Letter to Mary Baker Eddy, May 12. 028b.11.067. EC.

Dodge, Annie. 1901. Letter to Mary Baker Eddy, November 4. 028b.11.005. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1934. Science and Health, with Key to the Scriptures. Boston: Trustees under the Will of Mary Baker G. Eddy

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1936. Manual of The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist in Boston, Massachusetts. Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1900a. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, March 21. V01708. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1900b. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, December 17. H00069. EC. Original at Huntington Library (hereafter HL).

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1909a. Letter to Archibald McLellan, July 31. L03237. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1909b. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, October 9. L16643. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1909c. Letter to Christian Science Board of Directors, September 9. L0062. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1909d. Letter to Christian Science Board of Directors, October 12. L08770. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1909e Letter to Virgil O. Strickler, November 9. L08974. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1903. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, August 4. L02565. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1905. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, May 25. H00094. EC. Original at HL.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1897a. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, October 26. V01549. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1897b. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, December 10. V01554. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1875. Science and Health. 1st ed. Boston: Christian Scientist Publishing Company.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1893a. Letter to Ebenezer Foster Eddy, January 5. V01186. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1893b. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, December 28. V01279. EC.

Eddy, Mary Baker. 1895. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, September 10. L11229. EC.

Farlow, Alfred A. 1909. Circular letter, November 24. Special #30. Committee on Publication 30. EC.

First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City (hereafter First Church, New York). 1903. Trustees Minutes, January 19. Records Management Field Collection (hereafter RMFC), box 535164. folder 357207. EC.

First Church, New York. 1909a. Reports Read at Annual Meeting of First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, January 18. RMFC, box 535157, folder 356644. EC.

First Church, New York. 1909b. Church Inquiry of First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, November 4. RMFC, box 535174. folder 357207. EC.

Gill, Gillian. 1998. Mary Baker Eddy. Reading, MA: Oxford Perseus Books.

Gottschalk, Stephen. 2006. Rolling Away the Stone: Mary Baker Eddy’s Challenge to Materialism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Hendrick, Burton J. 1912. “Christian Science since Mrs. Eddy.” McClure’s Magazine 39 (May–October): 481–94. Hathitrust.

Hicks, Rosemary R. 2004. “Religion and Remedies Reunited: Rethinking Christian Science.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 20:25–58.

Johnston, William Allen. 1907. “Christian Science in New York.” Broadway Magazine 18:154–66. Box 531514. EC.

Lewis, Amy R. 1923. Letter to Augusta E. Stetson, April 13. SF, Augusta E. Stetson. EC.

Lindley, Susan Hall. 1996. “You Have Stept Out of Your Place”: A History of Women and Religion in America. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

New York Herald. 1920. “Ousted Christian Scientists Block Church Expulsion,” December 10, p. 1.

New York Times. 1927. “Mrs. Stetson Says She Will Never Die,” August 1, p. 10.

New York Times. 1904. “Our Hats Are All Alike,” June 2, p. 8.

New York Times. 1903. “Built from Plans Divinely Inspired,” November 30, p. 5.

New York Tribune. 1914. “Science Leader Resigns: Alfred Farlow Forced by Illness to Quit Committee,” May 26, p. 1.

Pagels, Elaine. 2006. “Introduction.” Pp. 1-8 in Secrets of Mary Magdalene: The Untold Story of History’s Most Misunderstood Woman, edited by Dan Burstein and Arne J. De Keijzer. New York: CDS Books.

Paulson, Shirley, Helen Mathis, and Linda Bargmann. 2021. An Annotated Bibliography of Academic and Other Literature on Christian Science. Chesterfield, MO: Scholarly Works on Christian Science.

Peel, Robert 1977. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Peel, Robert 1971. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Trial. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Stanley, May. 1917. “Mrs. Stetson Discusses Her Musical Beliefs,” July 14. Musical America 26:11-12.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1914/1917. Vital Issues in Christian Science: A Record of Unsettled Questions which Arose in the Year 1909, Between the Directors of the Mother Church, the First Church of Christ, Scientist, Boston, Massachusetts, and First Church of Christ, Scientist, New York City, Eight of its Nine trustees and Sixteen of its Practitioners. Second Edition. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1913/1917. Reminiscences, Sermons, and Correspondence Proving Adherence to the Principle of Christian Science as Taught by Mary Baker Eddy. 2nd ed. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1909. Composite Letter, July 10. Field Collection (hereafter cited as FLDC) 6, box 535174. EC.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1897. Letter to Mary Baker Eddy, July 10. (CH92 (c1). EC.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1894. Letter to Mary Baker Eddy, June 22. CH92 (c1). EC.

Stetson, Augusta E. n.d. “Obstetrics” AS550. Typescript. Augusta E. Stetson Collection, HL.

Strickler, Virgil. 1909. Diary. FLDC 6, box 535174. EC.

Swensen, Rolf. 2020. “A ‘Green Oak in a Thirsty Land’: The Christian Science Board of Directors Routinizes Charisma, 1910–1925.” Nova Religio 24 32–58.

Swensen, Rolf. 2018. “Mary Baker Eddy’s ‘Church of 1879’: Boisterous Prelude to The Mother Church.” Nova Religio 22, no. 1: 87–114.

Swensen, Rolf. 2010. “A Metaphysical Rocket in Gotham: The Rise of Christian Science in New York City, 1885-1910.” Journal of Religion and Society 12:1–24.

Swensen, Rolf. 2008. “‘You Are Brave but You Are a Woman in the Eyes of Men’: Augusta E. Stetson’s Rise and Fall in the Church of Christ, Scientist.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 24: 75–89.

Swihart, Altman K. 1931. Since Mrs. Eddy. New York: H. Holt and Company.

Thomas, Robert David. 1994. “With Bleeding Footsteps”: Mary Baker Eddy’s Path to Religious Leadership. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Voorhees, Amy B. 2021. A New Christian Identity: Christian Science Origins and Experiences in American Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Unattributed clipping. 1894. CH92 (c1). EC.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Campion, Nardi Reeder. 1976. Ann the Word. Boston: Little, Brown.

Gottschalk, Stephen. 1973. The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1924. Sermons Which Spiritually Interpret the Scriptures and Other Writings on Christian Science. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1923. Letters and Excerpts from Letters, 1889–1909, from Mary Baker Eddy . . . to Augusta E. Stetson, C.S.D. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1917. General Anthems: Light the Torch. New York: G. Schirmer.

Stetson, Augusta E. 1901. Poems: Written on the Journey from Sense to Soul. New York: Holden and Motley.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Mary Baker Eddy Library; Burke Library, Union Theological Seminary; and the Huntington Library. The staff of the Mary Baker Eddy Library at The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, Boston, Massachusetts, carefully reviewed the profile for accuracy of text and references. The Committee on Publication of The Mother Church graciously helped me with the permissions process. Opinions expressed by the author in this work are solely his own and are not endorsed by The Mary Baker Eddy Library or The Mary Baker Eddy Collection.

Publication Date:

23 January 2023