ANANDA TIMELINE

1920: Yogananda arrived in the U.S.

1924: Yogananda established Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) headquarters in Los Angeles.

1926: Donald Walters was born in Teleajen, Romania.

1939: Walters and his family moved to the U.S.

1948: Walters read Autobiography of a Yogi, moved to California, and became Yogananda’s disciple.

1952: Yogananda died.

1955: Walters took Swami vows and became Swami Kriyananda.

1955-1958: Kriyananda toured SRF centers in the US and Europe, lecturing and teaching yoga.

1958-1960: Kriyananda visited India, settled there and taught.

1960: Kriyananda returned to the US for six months; Kriyananda traveled back to India planning to establish an ashram in New Delhi.

1961: Kriyananda and the SRF leadership fell out over ashram plans.

1962: The SRF Board of Directors removed Kriyananda from the organization.

1962-1967: Kriyananda did some teaching, singing, and writing as he determined what to do with his life.

1967: Kriyananda purchased land to start Ananda.

1968: The Ananda Retreat Center was constructed.

1969: Kriyananda purchased additional acreage and the Ananda World Brotherhood Village began.

1970-1975: Approximately 100 new members joined the community.

1974: New land was purchased.

1976: A forest fire destroyed most of the community’s buildings.

1977: Kriyananda’s autobiography, The Path: Autobiography of a Western Yogi was published; Circle of Joy (now Ananda Sangha) and Sacramento city ashram were established.

1978-1980: Kriyananda and Ananda members conducted Joy Tours across the US, lecturing and promoting The Path.

1978: The Nevada County Board of Supervisors approved the master Plan for Ananda Village.

1979: New land was purchased and Ananda World Brotherhood Retreat (now The Expanding Light) was established.

1980: East-West Bookshop and ashram opened in Menlo Park.

1981: Kriyananda informally exchanged vows with Kimberly Moore.

1983: An Ananda community was established in Veglio, Italy near Lake Como.

1985: Moore left Kriyananda; Kriyananda renounced his vows and married Rosanna Golia.

1987: The Festival of Light was incorporated into Sunday services; land was purchased in Assisi, Italy for a European Ananda retreat.

1990: Ananda added “Self-Realization” to its name

1990-2002: Self-Realization Fellowship Church’s lawsuit against Ananda Church of Self-Realization and Kriyananda took place.

1994: Kriyananda and Golia divorced.

1995: Kriyananda resumed his monastic vows.

1997-1998: Anne-Marie Bertolucci’s lawsuit against Kriyananda and Ananda took place.

2003: Kriyananda moved to India.

2004-2009: Italian officials investigated Ananda’s Assisi community.

2009: Kriyananda established the Nayaswami order.

2013: Kriyananda died in Assisi, Italy; Jyotish became president.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Oil geologist Ray Walters and his Paris-trained violinist wife Gertrude were living in Teleajen, Romania near Ploiesti when their son James Donald was born on May 19, 1926. Donald grew up speaking English, Romanian, and German and traveling throughout Europe. His family traveled to the U.S. for a summer vacation in 1939, where they remained throughout World War II. After graduating from Haverford College, Walters was introduced to Indian spirituality and cosmology through a book in his mother’s library and began to consume classical Indian texts (Novak 2005).

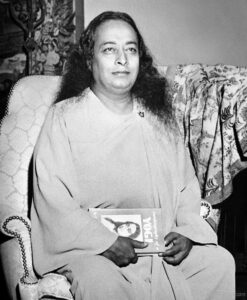

Later that year, he encountered the book that would change his life. “Autobiography of a Yogi is the greatest book I have ever read,” Walters later reflected. “One perusal of it was enough to change my entire life. From that time on my break with the past was complete. I resolved in the smallest detail of my life to follow Paramahansa Yogananda’s teaching” (Kriyananda 1977). [Image at right]

Yogananda was born in India in 1893. His mentor, Swami Sri Yukteswar, taught a “scientific” pathway to divine encounter through Kriya Yoga. In 1915, Yogananda took vows to become a member of the Swami Order. An opportunity to share Kriya Yoga with Westerners came when he traveled to the United States as a delegate to the 1920 International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, where he delivered a talk on the “Science of Religion.” He made Los Angeles the national headquarters of Self-Realization Fellowship, which aimed to develop devotees’ “physical, mental and spiritual natures” as they communicated with God through scientific concentration and meditation (Neumann 2019).

When Walters finished Autobiography, he immediately decided to travel to Southern California to become Yogananda’s discipline. He left a note for his godfather that said, “I’m going to California to join a group of people who, I believe, can teach me what I want to know about God and about religion.” At his first encounter with Yogananda, Walters was struck by Yogananda’s grace and beauty. “What large, lustrous eyes now greeted me! What a compassionate smile! Never before had I seen such divine beauty in a human face.” Yogananda seemed reluctant to take Walters in, as he was accepting few disciples at the time. At last he relented, but asked for total devotion from Walters. Walters was bold enough to ask if he had to obey even when he disagreed with Yogananda, to which  Yogananda replied, “I will never ask anything of you, that God does not tell me to ask.” That answer satisfied Walters, who henceforth became Yogananda’s disciple (Kriyananda 1977). [Image at right]

Yogananda replied, “I will never ask anything of you, that God does not tell me to ask.” That answer satisfied Walters, who henceforth became Yogananda’s disciple (Kriyananda 1977). [Image at right]

For over three years, Yogananda mentored Walters as a member of Self-Realization Fellowship. Life changed dramatically when Yogananda died at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles in 1952 during a celebration dinner for the first Indian ambassador to the U.S. Walters felt Yogananda’s presence while he stood in front of his master’s crypt shortly after the interment and was convinced that Yogananda continued to be present, guiding his life (Neumann 2019).

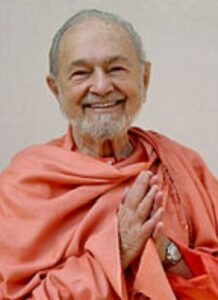

Walters took his final vows in 1955 under SRF president Daya Mata, becoming Swami Kriyananda. He traveled to India for the first time in 1958 and was promoted to vice-president of SRF in 1960. His restlessness over the strictures of institutional religion, combined with ongoing tensions with the leadership, led to his ouster from the organization in 1962. [Image at right]

After being forced out of SRF, Kriyananda felt disillusioned, unsure what to do with his life severed from the organization that had given that life meaning. As he wandered physically and spiritually, he explored Episcopalian monasteries in three states, lived briefly in a Catholic hermitage near Big Sur, became an ashram minister in San Francisco, and contemplated joining a religious site in Lebanon (Kriyananda 1977).

In 1967, at the height of the counterculture, Kriyananda and a few like-minded individuals began construction of a community in the Sierra Nevada mountains that epitomized the era’s communes. Well-known Beat figures Allen Ginsberg, Richard Baker, and Gary Snyder joined with Kriyananda to purchase several hundred acres near Nevada City northeast of Sacramento. Kriyananda used his portion for the creation of Ananda, a cooperative community (Miller 2010).

Kriyananda’s communal vision sprang from the “brotherhood communities” Yogananda had called for decades earlier when he returned from India. Kriyananda envisaged “places to facilitate the development of an integrated, well-balanced life, and as examples to all mankind of the advantages of such a life.” Not isolated from the larger world, they would be “an integral part of the age in which we live.” Ananda’s focus on “householders” offered a sharp contrast with SRF, which devoted substantial attention to strengthening monastic communities, even though the vast majority of rank-and-file SRF members were married devotees (Kriyananda 1977).

Kriyananda displayed great ambivalence about the virtues of a monastic life compared with the attractions of sexual intimacy. He was informally married to Kimberly Moore, whom he met during a trip to Hawaii. He introduced her to the community as “Parameshwari” and they exchanged vows, though this was not a legally recognized marriage, as Moore had not divorced her husband. Kriyananda and Moore separated in 1985. The same year, he married Rosanna Golia, an Italian Catholic-charismatic woman from Assisi. The two divorced in 1994. Between his two marriages, Kriyananda had several consensual sexual relationships with Ananda community members, but after his divorce from Golia he renewed his monastic vows and later insisted, in agreement with traditional swami doctrine, that celibacy was essential for spiritual development (Yogananda for the World).

In the early 1970s, the community grew to around one hundred full time residents, who attempted to figure out how to live together and how to earn a living. Kriyananda established formal membership for Ananda. There though was tremendous fluidity, especially in the early years, there were also some hard and fast rules: no drugs or alcohol and no dogs. Kriyananda used the retreat as a source of income and established a publishing house. Others experimented with a variety of businesses, including jewelry making, essential oils, and health food candy. The community’s commitment was sorely tested when a forest fire  destroyed most of the homes and other buildings in 1976. Several families left as a result of the fire’s destruction (Helin 2021b). [Image at right]

destroyed most of the homes and other buildings in 1976. Several families left as a result of the fire’s destruction (Helin 2021b). [Image at right]

One source of income, and a key text for the community, was Kriyananda’s autobiography, The Path: Autobiography of a Western Yogi. The book, whose title consciously echoed Yogananda’s autobiography, was published in 1977 after the writing project, begun in 1974, was disrupted by the fire. Beginning in 1978, the community conducted two road trips called The Joy Tours to promote the book.

In 1978, the Nevada County Board of Supervisors approved the Master Plan for Ananda Village, which had languished for four years. The approval lifted a moratorium on building. Over the next several years, through trial and considerable error, the community built several housing clusters. The community shifted to a more sustainable model with the addition of integrated infrastructure, widened roads, electricity and the modern conveniences it enabled. Several young families joined the community which shifted primarily to householders, rather than single adults.

As the community began to grow, Kriyananda sought to share the good news of Kriya Yoga outside Ananda. The first center outside Ananda was established in Sacramento when two community members rented a house there and began advertising for yoga classes. In 1991, Ananda Sacramento relocated to a 3.5-acre property with forty-eight apartments in Rancho Cordova. A new center was established in Palo Alto to staff East West Bookshop and eventually moved into a seventy-two-unit apartment complex. A Seattle center was launched in 1986 and a Portland center the following year. In the inventive spirit of a community born in the counterculture, Ananda launched several ventures that ultimately failed. A San Francisco ashram begun in the early 1980s closed before the end of the decade. A second Ananda Village, called Oceansong, was launched in Santa Rosa in 1979 but closed as an Ananda community in 1986.

These experiments extended overseas as well. A small center was established in a summer villa near Lake Como. Using that center as a base, devotees spread out to Western Europe, Yugoslavia, and Russia to share the word about Kriya Yoga (Helin 2021a).

Beginning in the 1990s, Ananda experienced a number of challenges. Some of these, discussed in more detail below, involved lawsuits that led the community to file for bankruptcy. Then Kriyananda, the leading force and guiding spirit of the community, died in 2013 in Assisi, Italy at age eighty-six. John “Jyotish” Novak, has led the community since. A friend of Kriyananda’s since 1966, Jyotish was long expected to be his successor. Though Jyotish is the official leader, his wife Devi shares leadership of the community with him.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Ananda’s beliefs, like those of Kriyananda’s guru Paramahansa Yogananda, are syncretistic. Foundational beliefs derive from the Vedas and yoga texts, but frequently reference Christian traditions. Kriyananda affirmed that “the universe is projected from God through vibration” of the primordial sound “AUM.” Indeed, AUM is God. Meditating on this sound allows a practitioner to “sing in harmony with the universe.” The world, while real, is also in a profound sense maya, or delusion. The “essence of the spiritual path,” according to Ananda, is “freeing ourselves from maya.” This happens when the ego experiences Self Realization, full recognition of its identity as “One with All that is,” or Satchitananda, which Ananda defines, quoting Yogananda, as “ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new bliss.” Ananda refers to God in personal terms, including use of the male pronoun and frequent references to Divine Mother. In line with Yogananda’s Advaita Vedanta, however, personal terms for the deity are only aids that enable humans to relate to Brahman, or ultimate reality, which is beyond attributes and thus non-personal. Human experience is fundamentally shaped by one’s karma, the “law of cause and effect,” the “action, whether physical or mental, individual or performed by a group,” which always bear a consequence. Karma from past reincarnations can shape one’s present life, and can be collective as well as individual. Individuals do not need to suffer all of the consequences of their karma. It can be burned up through meditation or borne sacrificially by a guru who is free from karma (Yogic Encyclopedia 2021).

If Ananda is rooted in Hindu cosmology, it is also strongly shaped by Yogananda’s fascination with Jesus Christ and his desire to draw connections between Christianity’s founder and yogic truth. For more than a decade, Yogananda offered commentary in his East-West magazine on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in the New Testament entitled “The Second Coming.” Yogananda used the term to refer to the experience of Self Realization, which he often termed “Christ Consciousness.” Kriyananda’s 2007 Revelations of Christ: Proclaimed by Paramhansa Yogananda endorsed Yogananda’s views on Jesus. Ananda thus baptizes Jesus a guru who practiced Kriya Yoga and it frequently mentions him on its website, explaining that he “became one with God” but that he did not die to save people from their sins (Ananda website n.d.).

Gurus play a central role in Ananda. Traditionally, humans be liberated from the limitations and confusions of human existence only through the guidance of a living guru. Ananda has modified this teaching because Yogananda announced before his death that he was the last in his line of gurus. Just before Kriyananda’s death, he explained that he was Ananda followers’ guru not because he was a direct disciple of Yogananda, but rather because God is the ultimate guru who works not only through Yogananda and his line of gurus, but also through the disciples “who have received that power from these gurus” (Ananda website n.d.).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Many of Ananda’s practices are drawn directly from those taught by Kriyananda’s mentor, Yogananda. The first is a set of “energization exercises,” a sort of prelude to yoga. Yogananda seems to have adapted the exercises from nineteenth-century Danish physical culturalist J. P. Muller. Beginning with proper posture, practitioners perform a set of up to thirty-nine exercises to concentrate on muscles and then systematically tense and relax them. With practice, the exercise routine can be completed in less than fifteen minutes. By “drawing Cosmic Energy into the body through the medulla oblongata by the power of will,” practitioners receive practical benefits including energy, a sense of well-being, tension release, and the ability to sit still for  longer periods. The Ananda website includes a brief free YouTube video modeling the practice and various support materials for purchase: an app with an audio guide, a longer DVD, and a booklet with illustrations drawn from those created by Yogananda (Neumann 2019).

longer periods. The Ananda website includes a brief free YouTube video modeling the practice and various support materials for purchase: an app with an audio guide, a longer DVD, and a booklet with illustrations drawn from those created by Yogananda (Neumann 2019).

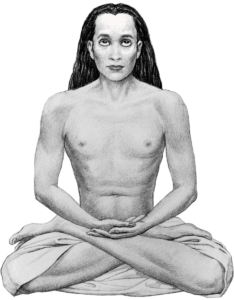

The second and more important Ananda practice that derives from Yogananda is Kriya Yoga. Yogananda presented Kriya as a practice that disappeared millennia ago and was reintroduced through the special revelation of the great yogi Babaji [Image at right] to Lahiri Mahasaya, who in turn introduced it to Sri Yukteswar, Yogananda’s guru. Kriya Yoga largely reflects classical yoga traditions, including guidance on breath control, concentration, meditation, and the repetition of mantras to realize that the true self must not be confused with the individual body. According to Ananda, Kriya Yoga “helps the practitioner control the life force by mentally drawing the life force up and down the spine, with awareness and will.” As a  result, people are better able to concentrate, are more successful in business, and “become better people in every way” (Ananda website n.d.). [Image at right]

result, people are better able to concentrate, are more successful in business, and “become better people in every way” (Ananda website n.d.). [Image at right]

Following Yogananda’s lead, Ananda often highlights the practical benefits of Kriya, and gradually makes the spiritual benefits clearer as practitioners continue. The more esoteric goal of Kriya Yoga is Samadhi, which Ananda defines as “the state in which the yogi perceive [sic] the identity of his soul as spirit. It is an experience of divine ecstasy as well as of superconscious perception; the soul perceives the entire universe.” Nirbikalpa samadhi, the highest stage of samadhi, is required to achieve moksha, or liberation (Yogic Encyclopedia 2021).

Disciples can only learn Kriya in person through initiation, which they can prepare for in three ways. Those who live near an Ananda Center can take courses in person. Others who live further away can register for online courses, a modern version of the yoga correspondence course that Yogananda pioneered a century ago. The online course takes a year or more, depending on the pace of the disciple. Interested parties can also purchase a series of books, which are presented as a useful resource even for those learning at a center or online (Neumann 2019).

Those who are ready participate in a ceremony that initiates them into discipleship to Yogananda, which is a prelude to Kriya Yoga initiation. Though Ananda does not provide details about the current ceremony to outsiders, in the early days of the community the ceremony took three hours and consisted of three parts. After opening chants, there was a fire ceremony that consumed accumulated bad karma. Then initiates made three lifetime vows: commitment to the line of gurus that culminates in Yogananda, a promise never to reveal Kriya secrets to anyone, and promise to practice Kriya every morning and evening. Finally, initiates presented themselves individually before Ananda leadership for Kriya baptism and a blessing. The ceremony concluded with the explanation of Kriya and a celebration involving a special beverage and singing of the Rose Chant, the only time the community sang this song (Ball 1982).

Apart from classes on meditation and yoga, Ananda members take courses on spirituality, health and well-being, and vegetarian cooking. Some of these are offered in person, but many are provided online. They also participate in devotional gatherings, chant spiritual songs (known as kirtans), and go on retreats (Kirby 2014).

Ananda has a series of annual celebrations that create a liturgical rhythm for community members. Every year it celebrates key anniversaries in Yogananda’s life and has especially commemorated major milestones: the centennial of his 1920 arrival in the U.S. (1920), the seventy-fifth anniversary of Autobiography of a Yogi’s 1946 publication, and the seventieth anniversary of his mahasamādhi, a self-realized guru’s conscious release of the body. Kriyananda, too, is regularly honored. His birthday, the anniversary of his death, and the anniversary of his discipleship to Yogananda are all celebrated annually by the community. Every year, Ananda also celebrates Spiritual Renewal Week, a conference and convocation. 2019 marked a major milestone as Ananda celebrated its fiftieth anniversary as an organization with a week-long program and dedication of a new Temple of Light (Ananda website n.d.).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The early Ananda community shared the egalitarian spirit and voluntarist ethos of other communes of the counterculture era. Early members were often college educated spiritual seekers, with a disproportionate number of Jews. Though initially mostly single people, the community was eventually dominated by families. Inspired in part by Kriyananda’s own foray into romantic relationships, several singles in the community ended up marrying over time (Ball 1982; Reflections 1998).

As a larger spiritual organization that transcends the Sierra Nevada community, however, Ananda has also been shaped by normative beliefs and a hierarchical leadership structure. Indeed, even in the early years Ananda established levels of membership because people settled in the community with varying degrees of commitment to Kriyananda’s larger vision. Like Yogananda, Kriyananda always insisted on the importance of a guru, or spiritual teacher, for growth on the spiritual path and Ananda has maintained that view since his death. Jyotish and Devi Novak have played this role since Kriyananda’s death, but other long-term members and advanced yoga practitioners also serve as teachers and leaders.

Ananda embraces practices associated with Hindu tradition alongside modern syncretic practices. In additional to embracing Sanskrit texts and their practices, Ananda gives individuals Sanskrit names when they become members. Like traditional swamis, Yogananda often wore an ochre robe, a practice adopted by SRF. To distinguish themselves from that organization, Ananda leaders wear blue robes. Kriyananda created a new swami order called the Nayaswami order. Literally meaning “new swami” it recognizes the possibility that serious discipleship does not require singleness (though it does require celibacy). Ananda maintains altars that display portraits of Yogananda and the members of his spiritual lineage, as well as Jesus Christ. Yogananda, believed to have entered mahasamādhi in 1952, remains a spiritual presence, guiding leaders and inspiring members. Although Ananda members believe that Kriyananda had the mantle of leadership from Yogananda’s commissioning of him, he was not added to this pantheon after his death and Ananda does not offer prayers to him (Ananda website n.d.).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Ananda has faced a number of significant challenges in a little over a half-century of existence. First, the very viability of the Ananda community was an open question for many years. It had a very rocky start as a communal experiment in the Sierra Nevada foothills with no preexisting infrastructure and little capital. As described above, a 1976 fire destroyed most buildings less than a decade into its life. The early community experienced some suspicion from neighbors and county officials. Permit approval dragged on, and Ananda’s 1980 attempt to incorporate as a city was ultimately unsuccessful. (Ball 1982; Reflections 1998; Helin 2021a)

The second and by far more significant challenge came from the lawsuits brought against Ananda and the controversies that surrounded them. In 1990, Kriyananda decided to add “Self-Realization” to Ananda’s name. This triggered a lawsuit in which Self-Realization Fellowship claimed that it had sole right to use of the term, to publish Yogananda’s writings (even though some texts had never been formally copyrighted and others, like Autobiography, had expired copyrights), to use of Yogananda’s name, and to use photographs of him. At stake was Ananda’s ability to represent itself as an organization devoted to Yogananda (Parsons 2012; Asha Swami Kriyananda)

During this lawsuit, a former member of Ananda, Anne-Marie Bertolucci of Palo Alto, sued senior minister Danny Levin, vice president of Ananda’s publishing wing, Crystal Clarity. Later, she added Swami Kriyananda to the suit, alleging that he made unwanted sexual advances toward her when she appealed to him for help. Ananda acknowledged an affair between Bertolucci and Levin but steadfastly denied the charges against Kriyananda. Seven women ultimately testified under oath to sexual harassment at Ananda, and a $1,800,000 judgment was brought against the organization (Anning 1997).

Ananda won parts of the copyright lawsuit: the organization was allowed to use Yogananda’s name, some photographs of him, and the term “Self-Realization.” More importantly, anyone could publish Autobiography of a Yogi and a few other books without threat of suit by SRF. One point of contention in the lawsuit was the many changes SRF had made to Autobiography over the years, so Ananda makes a point of providing the original 1946 edition of the text. Between legal expenses and the Bertolucci judgment, Ananda filed for bankruptcy. Punitive damages were reduced on appeal and the community managed to regroup and survive the financial and reputational damage. Since then, Ananda faced an additional legal challenge when Italian authorities raided the Assisi ashram on suspicion of fraud. The investigation ended in 2009 after a judge dismissed the case as lacking substance (Gao 1999; Bate 2004).

Finally, Kriyananda’s death constituted a crisis of sorts. The brilliant founder of Ananda was a charismatic figure and a direct disciple of Yogananda. Although no successor could fill his shoes, he never claimed to be a fully self-realized guru worthy of divine reverence. Kriyananda’s own weaknesses, including sexual affairs with members of Ananda that became public during the Bertolucci lawsuit, eased the leadership transition. Ananda members respect him and refer to him affectionately, but they reserve their devotion for his mentor, Paramhansa Yogananda.

IMAGES

Image #1: Cover of Autobiography of a Yogi.

Image #2: Paramahansa-Yogananda.

Image #3: Swami Kriyananda.

Image #4: Anada community.

Image #5: Babaji.

Image #6: Yogananda with Hatha yoga disciples (with Kriyananda meditating at the bottom left).

REFERENCES

Ananda website. 2021. Accessed from https://www.ananda.org on 6 November 2021.

Anning, Vicky. 1997. “Courts: Ananda Church Founder Takes the Stand.” Palo Alto Online, December 5. Accessed from https://www.paloaltoonline.com/weekly/morgue/news/

1997_Dec_5.WALTERS.html on 6 November 2021.

Asha, Nayaswami. 2019. Swami Kriyananda: Lightbearer: The Life and Legacy of a Direct Disciple of Paramhansa Yogananda. Accessed from https://www.yoganandafortheworld.com/

story/an-intimate-account-of-a-direct-disciple-of-paramhansa-yogananda/ on 6 November 2021.

Ball, John. 1982. Ananda: Where Yoga Lives. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green University Popular Press.

Bate, Jamie. 2004. “Swami Clear in Italy Case: Ananda Founder Safe from Arrest, Supporters Say.” The Union, March 27.

Gao, Helen. 1999. “Sex and the Singular Swami.” San Francisco Weekly, March 10. Accessed from https://archives.sfweekly.com/sanfrancisco/sex-and-the-singular-swami/Content?oid=2136254 on 6 November 2021.

Helin, Sadhana Devi. 2021a. Expanding the Light: A History of Ananda, Part II: 1997-1990. Accessed from https://www.ananda.org/free-inspiration/books/expanding-light/ on 8 November 2021.

Helin, Sadhana Devib. Many Hands Make a Miracle: A History of Ananda, 1968-1976. Accessed from https://www.ananda.org/free-inspiration/books/many-hands-make-a-miracle/ on 6 November 2021.

Kirby, Prisha. 2014. “Ananda and the World Brotherhood Communities Movement.” Communal Studies 34:185-216.

Kriyananda, Swami. 1997. The Path: Autobiography of a Western Yogi. Nevada City, CA: Ananda Publications.

Miller, Timothy. 2010. “The Evolution of American Spiritual Communities, 1965–2009.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 13:14-33.

Neumann, David J. 2019. Finding God Through Yoga: Paramahansa Yogananda and Modern American Religion in a Global Age. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Novak, Devi. 2005. “Faith is my Armor:” The Life of Swami Kriyananda. Nevada City, CA: Crystal Clarity.

Parsons, Jon R. 2012. A Fight for Religious Freedom: A Lawyer’s Personal Account of Copyrights, Karma and Dharmic Litigation. Nevada City, CA: Crystal Clarity.

Reflections on Living: 30 Years in a Spiritual Community. 1998. Nevada City, CA: Ananda Publications.

Yogananda, Paramahansa. 1946. Autobiography of a Yogi. New York: Philosophical Library.

Yogananda for the World website. Accessed from https://yoganandafortheworld.com/ on 9 November 2021.

The Yogic Encyclopedia: The True Meaning of Sanskrit Words website. 2021. Accessed from https://www.ananda.org/yogapedia on 9 November 2021.

Publication Date:

14 November 2021