FERAFERIA TIMELINE

1928 (November 2): Frederick “Fred” McLaren Adams was born.

1935: Svetlana Butyrin was born.

1956: Enrolled as a graduate student at Los Angeles State College, Fred experienced a mystical revelation that instilled in him the lasting belief that God is principally feminine.

1957: Fred and a group of friends founded the Hesperian Fellowship. Fred wrote “Hesperian Life and the Mother Way” (later published as “Hesperian Life and The Maiden Way”).

1967 (August 2): Feraferia was incorporated as a 501(c)3 church in California. The earliest issues of Feraferia’s newsletter, Korythalia, were published. Fred published Nine Royal Passions of the Year.

1989: Jo Carson began filming interviews and traveling to sacred sites with Fred for the project that became Dancing With Gaia.

1990s: Fred and Svetlana relocated to Nevada City, California to be near Svetlana’s adult children.

1998: Peter “Phaedrus” Tromp befriended Fred and started a Feraferia group in Amsterdam, making Feraferia ritual scripts available in Dutch.

2008: Upon his death, Fred was honored with a Feraferia Whole Earth Initiation (a funerary ritual that Fred himself had authored during his lifetime).

2009: Jo Carson’s Dancing With Gaia premiered at the Fairfax Documentary Film Festival.

2010 (May 6): Svetlana died after relapsing from pneumonia.

2011: Jo Carson accepted the position of President of the Board and High Priestess of Feraferia. She and her husband, John Reed, created a website repository for Feraferia lore.

2012: A Feraferia Facebook page was launched that has remained an active site for information and announcements.

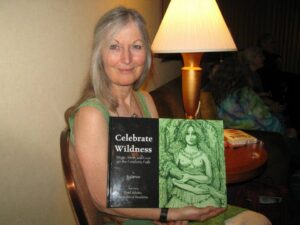

2014: Jo Carson published Celebrate Wildness: Magic, Mirth and Love on the Feraferia Path.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Feraferia tradition of Neo-Paganism was founded in the 1960s by Frederick “Fred” McLaren Adams (1928–2008), with significant input from his partner Svetlana “Lady Svetlana” Butyrin (1935–2010). Its members say its name means “celebration of wildness” from the Latin fera (wild) and feria (festival).

Fred was a lifelong student who studied mythology and esoterism since his youth and, in his adulthood, pursued degrees in psychiatry, cinematography, anthropology, and art. He was a graduate student at Los Angeles State College, studying anthropology and fine arts, when he had an ecstatic experience and realization that God is female, which led him to the founding of Feraferia in his late twenties. In 1957, Fred and a group of friends founded the Hesperian Fellowship. Fred wrote “Hesperian Life and the Mother Way” (later published as “Hesperian Life and The Maiden Way”). The tradition evolved into Feraferia and was incorporated as a 501(c)3 church in California in 1967. The organization produced a newsletter, titled Korythalia, several issues of which are preserved in the Graduate Theological Union’s New Religious Movements collection.

Fred and Svetlana met in the mid-1960s and had tremendous chemistry. [Image at right] They were life partners as well as becoming the pillars of the developing Feraferia tradition. Together, they wrote the majority of its rituals.

Fred and Svetlana felt like soulmates, but each did have other partners at times during the 1980s and 1990s. Then they were back together until Fred passed away from skin cancer (August 9, 2008), and Svetlana died only two years later after relapsing from a severe case of pneumonia (Carson 2009b; n.d.). Fred was memorialized in a Feraferia Whole Earth Initiation, a ceremony written by Fred himself that “magically dedicates the body systems of the beloved dead to related parts of the greater Earth body” (Carson 2009b) in September 2008 (Poke, 60).

Feraferia reached a peak in the 1970s. Although Feraferia was never a large group, the tradition inspired many and has been included in several scholarly discussions of contemporary Paganism, demonstrating its significance at least to historians (Adler 2006; Ellwood 1971; Clifton 2006). Fred has been compared to William Blake, sometimes being dubbed “the American William Blake” (C.f. P. Runyon 2011, 59). Describing the elegance that has defined Feraferia, Margot Adler writes: “Considered by its small following to be the aristocrat of Neo-Paganism, it has all the advantages and disadvantages that the word ‘aristocrat’ implies” (Adler 2006, 247). Feraferia’s alleged aristocratic aesthetics and belief system were its blessing and its curse; it appealed to some and deterred others. Receiving criticism for its seeming elitism, Feraferia responded:

Several readers [of Feraferia’s newsletter Korythalia] have raised objections to “difficult” and “obscure” terminology of the sort that crops out…fairly often. Unless you have read somewhat in ancient history and in the esoteric and occult, these terms will stop you—but only momentarily, we hope. In most cases there simply are no other terms that mean ‘the same.’ Maybe we eventually can coin some satisfactory substitutes. Till then, keep a dictionary at hand. We aren’t forgetting about the objections; but for the present, a glossary is beyond our resources of time and energy. (Anyone want to volunteer to work on one?) (RJS [Richard J. Stanewick], in Feraferia 1970:4)

A contributor to the movement, Stanewick defended its more obscure terminology (for “there simply are no other terms”) yet conveyed a sentiment of openness to change and, especially, openness to assistance. Contemporaneously, Ellwood observed (1971:137):

Adams’s exercise of the leadership role has illustrated the problems inherent in this vocation. The vision is preeminently his, and he has himself done most of the writing, created most of the art, and devised most of the rites. In some ways he approaches religious genius, and undoubtedly without his labors the movement would not exist…. Yet there are those who feel that his personality stifles the creativity of others in the evolution of Feraferia…. Some feel his vision is so personal and intricate it does not communicate as easily as it should.

Ellwood reports that some “left [Feraferia] to establish their own henges and forms of neopaganism,” and we might presume that the obscurity of the Feraferia tradition was one motivating factor behind the offshoots.

Although Feraferia’s “pulse” was strongest during Fred and Svetlana’s lifetimes, Fred’s original rituals are preserved by a few committed disciples, such as Peter “Phaedrus” Tromp, who brought Feraferia to Amsterdam and translated the seasonal festivals into Dutch; Lady Selena, a professional belly dancer operating out of New Mexico, who integrated Feraferia principles and aesthetics within her inspired dance performances; and filmmaker Jo Carson in Northern California. In the late 1980s, driven by their mutual interest in preserving Fred’s ideas and teachings and the reality of his ailing health, Jo and Fred began filming interviews with active participants in the Feraferia tradition and with Pagan leaders outside of Feraferia. Included in their filming was also location footage from ancient sacred sites. Jo developed the footage into the documentary Dancing With Gaia (Carson 2009a). Interviewees included Fred Adams, Francesca DeGrandis, Monica Sjoo, Joan Marler, and Kathy Jones, among other influential Pagan/Goddess movement leaders. The documentary premiered at the Fairfax Documentary Film Festival in 2009. Jo was appointed President of the Board and High Priestess of Feraferia in 2011. Today, Jo and her husband John Reed lead rituals and foster community from their Fairfax, California henge and temple. They also manage a web presence for Feraferia.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Michael Strmiska (2005) describes two poles as defining most contemporary Paganism: reconstructionism and eclecticism. Reconstructionist groups, such as those from Asatru, Druidry, Hellenism, and Khemeticism, typically adhere to the reconstruction of one specific pre-Christian pagan, polytheistic and/or shamanistic, cultural belief system, including its rituals. Representative of the eclectic pole of contemporary Paganism, Wicca, in contrast, is an amalgamation of belief systems and ritual practices predominantly from Europe, but it is not the recreation of any one particular ethnic pagan culture. Feraferia is unique within this range, landing somewhere between the poles of reconstructionist and eclectic.

Feraferia is clearly aligned with Greek/Hellenic paganism. Its deity names consistently derived from Greek gods and goddesses, and its seasonal festivals aligned with ancient Greek mystery traditions. Yet, its founders from the beginning embraced creation and new inspiration in shaping Feraferia’s tradition and practice. Fred read widely, particularly from the Greco-Roman classics of antiquity. He envisioned the Eleusinian Mysteries from ancient Greece to be the “rootstock” of Feraferia (Carson n.d.). He considered Carl Kerenyi’s Eleusis: Archetypical Image of Mother and Daughter to be the most authoritative resource on the ancient Eleusinian Mysteries and placed much weight on Kerenyi’s interpretations.

Fred was clearly influenced by Wicca and other forms of Neo-Paganism developing around him in California as well, especially evidenced in Feraferia’s festivals matching the Wiccan Sabbats. Fred collaborated with Tim “Oberon” Zell (also known as Oberon Zell-Ravenheart), who founded the Church of All Worlds, and Feraferia’s newsletter Korythalia frequently pointed to the Church of All Worlds’ magazine The Green Egg as an additional resource. Fred was deeply invested in worldwide faerie lore. Jo Carson believes that Fred influenced Max Freedom Long on the importance of the Goddess. Long, in turn, was highly influential on Victor Anderson (a co-founder of Feri Tradition).

Feraferia shares much with mid-twentieth-century Gardnerian Wicca, but with a particularly Hellenistic aesthetic to its mythology and ritual traditions. The tradition emphasizes unity in masculine-feminine partnerships, with an underlying primacy of the feminine divine principle. That is, Goddess has primacy within the tradition, yet the dynamics between female and male are emphasized in the seasonal festivals. In this regard, Feraferia is similar to Gerald Gardner’s Wicca and Janet and Stewart Farrar’s (Alexandrian) Wicca (Gardner 1954:19; Farrar and Farrar 1987; see also Adler 2006:258–62); yet Feraferia has its own unique style and aesthetics independent of Wicca.

In addition to Feraferia’s juxtaposition between reconstructionism and eclecticism, Feraferia’s theology is bordered between hard polytheism and monism. Monism refers to a belief system that is polytheistic on the surface but ultimately embraces the ideal of unity among the deities as “manifestations” of the great divine. Contemporary Pagans have used the terms “hard polytheism” and “soft polytheism” to discuss the patterns of radical polytheism and a form of monism among their traditions (see also Lewis 1999:123). A popular quote from esotericist Dion Fortune, “All the goddesses are one goddess” (Fortune 1938:291), is a key example for the construct of “soft polytheism,” or what scholars might call a form of monism, in contemporary Paganism. To this discussion, Jo Carson adds: “Feraferia does not consider all goddesses to be aspects of one Goddess…. At a certain point we have to admit that we don’t know exactly what the relationship is between the Gods; it is part of the Mystery” (Carson personal communicaation).

Each Feraferia festival is informed by (often involving the reenactment of) a Greek myth about a female deity and a male deity. The emphasis on these distinct deities receiving worship each year suggests a degree of hard polytheism. Yet, the overarching pattern of one goddess and one god receiving worship at each seasonal festival (the Goddess receiving worship at Repose) suggests instead a soft polytheism, wherein each goddess-and-god pair represents a universal balance.

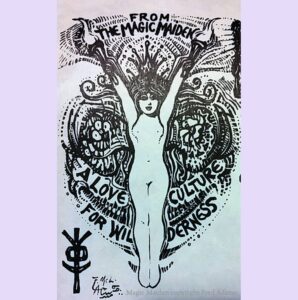

In alignment with Fred’s emphasis on the Eleusinian Mysteries, the Goddess Kore is at the center of all things Feraferia. [Image at right] In ancient Greek paganism, Kore (translated “maiden”) was a name of the goddess Persephone. The Eleusinian Mysteries were the festival mysteries associated with worship of Demeter, which occurred at Eleusis in ancient Greece. The rites are believed to have revolved around the mythic narratives of mother and daughter goddesses, Demeter and Persephone. Kore (Persephone) is also known as the Queen of the Underworld, with respect to her role as Hades’s bride, according to the same general myth. The underworld romance of Persephone and Hades is ritualized in Feraferia’s Samhain ritual.

The Feraferia aesthetic is utopian and paradisiacal. Fred and Svetlana were vegetarians, and they advocated wild food and foraging over complex agricultural systems. Jo Carson explains that, “in keeping [with the original intent] of promoting paradisal sanctuaries that are also bowers of edenic plenty,” the group is now promoting horticulture and aboriculture “because the fruit and nut trees provide excellent sustenance with relatively little ‘work’” (Carson personal communication).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

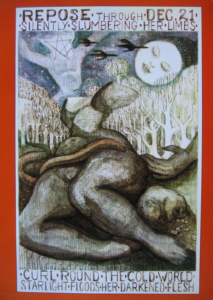

The Feraferia calendar is predominantly aligned with the Wiccan Wheel of the Year, with a few exceptions. In Feraferia, there are nine festivals, in contrast with the eight Wiccan Sabbats. To the standard eight, Feraferia adds a ninth festival: Repose and Cosmos (or simply, “Repose”), which is the seven-week period between Samhain and Yule and which unites the others (its rites observed at the midpoint between Samhain and Yule). The addition to the standard Wiccan Sabbats, Repose is conceptualized as the Center of the Wheel of the Year.

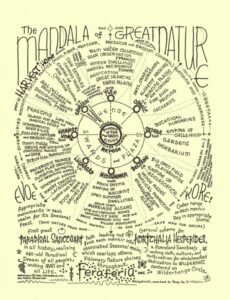

Symmetry and balance shape the Feraferia ritual calendar. [Image at right] After Repose, each festival is associated with a cardinal direction (Fred Adams n.d.). Again with the exception of Repose, each festival centers around a goddess-and-god pair. Some of the pairings are well established in common knowledge of Greek mythology (e.g. Hera and Zeus, Psyche and Eros, and Aphrodite and Adonis); other pairings, such as Artemis and Dionysos at Pomona, are less known but are found in ancient texts as well as in modern interpretations of Greek mythology. Yule, associated with North, centers around Hera and Zeus. Oimelc, associated with Northeast, centers around Amphitrite and Poseidon. Ostara, associated with East, centers around Hebe and Ganymede. Beltane, associated with Southeast, centers around Psyche and Eros. Hymenaea (which corresponds with Wiccan Litha), associated with South, centers around Selene and Helios. Lugnasad or Lammas, associated with Southwest, centers around Aphrodite and Adonis. Pomona (which corresponds with Wiccan Mabon), associated with West, centers around Artemis and Dionysos. (Pomona is the name of a Roman goddess associated with fruit trees and orchards, who has no known direct Greek counterpart.) Samhain, associated with  Northwest, centers around Persephone and Aidoneus (Hades). Repose, however, is devoted to Kore as Arretos Koura (“Nameless Maiden” [(Frederick Adams 1970)]), “the creatrix of universe and divinities” (Fred Adams n.d.) (Image at right). Though dyadic female-male pairs characterize the seasonal festivals, Feraferia envisions the feminine as the dominant face of the divine. The goddess’s name appears before the god’s in Feraferia’s descriptions of the festivals, and Repose, the core of the liturgical year, emphasizes the feminine divine almost exclusively. Fred’s 1956 epiphany of God as female remains persistent within the tradition. Fred’s interpretations of the nine festivals are memorialized visually in his published collection of paintings, Nine Royal Passions of the Year.

Northwest, centers around Persephone and Aidoneus (Hades). Repose, however, is devoted to Kore as Arretos Koura (“Nameless Maiden” [(Frederick Adams 1970)]), “the creatrix of universe and divinities” (Fred Adams n.d.) (Image at right). Though dyadic female-male pairs characterize the seasonal festivals, Feraferia envisions the feminine as the dominant face of the divine. The goddess’s name appears before the god’s in Feraferia’s descriptions of the festivals, and Repose, the core of the liturgical year, emphasizes the feminine divine almost exclusively. Fred’s 1956 epiphany of God as female remains persistent within the tradition. Fred’s interpretations of the nine festivals are memorialized visually in his published collection of paintings, Nine Royal Passions of the Year.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Like some other groups founded by charismatic leaders, Feraferia is nearly synonymous with its founder Fred Adams. Close insiders report that Fred and Svetlana led the organization together, and many of the rituals were written by Svetlana.

Regarding the organization and leadership of seasonal rituals, “Priestess” and “Priest” are liturgical roles. Emblematic of the primacy of the Goddess (Kore) in Feraferia, Priestesses are required far more than are Priests, at least according to the ritual scripts published in Phaedrus’s online collection (Frederick Adams, Butyrin, and Phaedrus n.d.). Priests are called for only occasionally (“The Evocation of Zenith, Nadir and Centre” of Lugnasad), and non-gender-specific Celebrants and a Priest/ess are included in the Pomona script. Yet, every ritual in the collection requires a Priestess.

As with many other contemporary Pagan traditions, initiation exists in Feraferia. Ellwood described four components of the Feraferia initiation ritual (which was still in the process of being developed at the time of Ellwood’s observance) the evocation of twenty-two “biomes of earth” including “archetypal landscapes” (e.g. “forest, arctic, swamps”) and “the principle astronomical bodies”; the invocation of these same elements “to the center of the henge, where they mystically form the body of the Magic Maiden”; the initiand’s mapping of one’s own body onto the same elements; and ecstatic dancing and an optional pledge to Kore (Ellwood 1971:136).

Feraferia’s influence has been great, but its numbers rather small. In 1971, Robert Ellwood reported a membership of about twenty (Ellwood 1971:137).) Today, there are small pockets of organized Feraferia activity, under independent leadership of a few students of Fred’s, most especially Jo Carson.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

As indicated by its history, the greatest challenge facing Feraferia has been its own survival. The group was active in Southern California in the 1960s and 1970s and re-emerged in Nevada City, California (just outside the Tahoe National Forest) in the 1990s when Svetlana and Fred moved there to be near Svetlana’sk grown children (Carson, n.d.; 2009b).

Feraferia is what we might call an “endangered” Neo-Pagan tradition. New religious movements that are reliant on particular charismatic leaders and that do not reach a certain membership level during the leader’s lifetime are likely to reach endangerment and/or extinction. Robert Ellwood predicted this outcome back in 1971: “It [Feraferia] is essentially a circle around a charismatic leader and has no real structure otherwise. It is not clear whether at this point it has any potential to survive him as a sociological entity” (Ellwood 1971:137). As a contrasting example, the Church of All Worlds (CAW) is virtually inseparable from its founder Oberon Zell, yet CAW’s membership reached several hundred in the 1990s and exists today in the United States, Australia, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Though Zell, now seventy-nine years old, is still the chief influencer for CAW, there are by far enough members, leaders, and nests to continue CAW for at least another generation going forward. The difference, it seems, lies in the expansion of the movement during the founder’s lifetime and the fostering of the movement’s foundation to exist independently of the founder.

Despite challenges to Feraferia’s growth over recent decades, current leadership is optimistic and believes Feraferia is on an upswing. Jo and other members believe that the message of Feraferia may be more important now than it was in Fred’s lifetime, clearly disagreeing with Ellwood’s 1971 prediction for Feraferia. Instead, members’ current belief is in keeping with Fred’s predictions, for he was known to say that “he doesn’t think the vision will even begin to be realized until after his lifetime” (Adler 2006:251). Prioritizing outreach, Jo led both  workshops about Feraferia’s history and Feraferia rituals at PantheaCon frequently from around 2012. (PantheaCon announced 2020 as its final conference.) She [Image at right] and her husband John also manage a large website (feraferia website 2022) and a Feraferia Facebook Page, keeping community connected as well as reaching potential new members and initiates. Jo published Celebrate Wildness: Magic, Mirth and Love on the Feraferia Path in 2014, and she is currently working on creating The Tarot of Feraferia, based on Fred’s art and the Enneasphere, Feraferia’s “psycho-cosmic-tuning system.” Jo and others also see the continuation of Feraferia through their infusion of Feraferian ideas and techniques into other Pagan traditions that they practice.

workshops about Feraferia’s history and Feraferia rituals at PantheaCon frequently from around 2012. (PantheaCon announced 2020 as its final conference.) She [Image at right] and her husband John also manage a large website (feraferia website 2022) and a Feraferia Facebook Page, keeping community connected as well as reaching potential new members and initiates. Jo published Celebrate Wildness: Magic, Mirth and Love on the Feraferia Path in 2014, and she is currently working on creating The Tarot of Feraferia, based on Fred’s art and the Enneasphere, Feraferia’s “psycho-cosmic-tuning system.” Jo and others also see the continuation of Feraferia through their infusion of Feraferian ideas and techniques into other Pagan traditions that they practice.

IMAGES

Image #1: Frederick “Fred” McLaren Adams and Svetlana Butyrin by Harold Moss from https://wildhunt.org/2010/05/pagan-passages-barbara-stacy-and-lady-svetlana.html.

Image #2: The Goddess Kore. Copyright by Jo Carson.

Image #3: Feraferia ritual calendar. Copyright by Jo Carson.

Image #4: “Repose.” Copyright by Jo Carson.

Image #5: Jo Carson. Copyright by Jo Carson.

REFERENCES

Adams, Fred. n.d. “Feraferia Seasonal Festivals.” Accessed from http://www.phaedrus.dds.nl/fera2.htm on 9 February 2021.

Adams, Frederick. 1970. “Eco-Psychic Mandala for Feraferia.” Feraferia. Graduate Theological Union’s New Religious Movements Organizations: Vertical Files Collection.

Adams, Frederick, Svetlana Butyrin, and Phaedrus. n.d. “Feraferia Seasonal Rituals.” Accessed from http://www.phaedrus.dds.nl/fera2.htm on 18 February 2021.

Adler, Margot. 2006. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers and Other Pagans in America. Revised and Updated with a new resource guide. New York: Penguin Books.

Carson, Jo. 2012. Feraferia’s Facebook Page. Accessed from https://www.facebook.com/Feraferia/?ref=page_internal on 18 December 2021.

Carson, Jo. 2009a. Dancing With Gaia: A Jo Carson Documentary. Natural Motion Pictures.

Carson, Jo. 2009b. “Fred Adams and Feraferia.” Accessed from http://feraferia.org/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=87:fred-adams-his-life-and-work&catid=65:founders&Itemid=104 on 18 December 2021.

Carson, Jo. n.d. Roots of Feraferia. Accessed from http://feraferia.org/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=63:roots-of-feraferia&catid=67:early-feraferia&Itemid=69 on 16 July 2021.

Carson, Jo. n.d. “Svetlana Butyrin, Lady Svetlana of Feraferia.” Accessed from http://feraferia.org/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=88:svetlana-butyrin-lady-svetlana-of-feraferia&catid=65:founders&Itemid=104 on 18 December 2021.

Clifton, Chas S. 2006. Her Hidden Children: The Rise of Wicca and Paganism in America. Boulder: AltaMira Press.

Ellwood, Robert S. 1971. “Notes on a Neopagan Religious Group in America.” History of Religions 11:125–39.

Farrar, Janet, and Stewart Farrar. 1987. The Witches’ Goddess: The Feminine Principle. Blaine, WA: Phoenix. Files Collection.

Feraferia website. 2022. Accessed from http://feraferia.org/joomla// on 5 January 2022.

Fortune, Dion. 1938. The Sea Priestess. London: Society of the Inner Light.

Gardner, Gerald B. 1954. Witchcraft Today. London: Rider & Company.

Lewis, James R. 1999. Witchcraft Today: An Encyclopedia of Wiccan and Neopagan Traditions. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Runyon, Poke. 2011. “Frederick Adams: The American William Blake.” Pp. 59-60 in The Seventh Ray, Book Three, “The Green Ray,” by The Church of the Hermetic Sciences and Ordo Templi Astartes, edited by Caroll “Poke” Runyon. Silverado, CA: The Church of the Hermetic Sciences, Inc.

Strmiska, Michael F. 2005. “Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives.” Pp. 1-53 in Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Michael F. Strmiska. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Publication Date:

5 January 2022