ARMY OF MARY / COMMUNITY OF THE LADY OF ALL PEOPLES TIMELINE

1921 (September 14): On the feast day of the Holy Cross, Marie-Paule Giguère was born in Sainte-Germaine du Lac-Etchemin, Quebec, Canada.

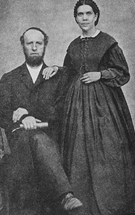

1944 (July 1): Marie-Paule Giguère married Georges Cliche.

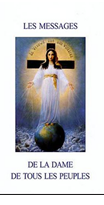

1945 (March 25): A series of apparitions and messages of the Lady of All Nations to visionary Ida Peerdeman began in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

1950 (January 2): Giguère heard a voice stating that the reason for her suffering “will be all unveiled.”

1954: Giguère started working for the radio and adopted her media identity as Marie-Josée. God spoke to her about The Army of Mary.

1957 (April): Giguère became a member of local groups of the earlier established Legion of Mary.

1957 (September): Cliche and Giguère divorced and their children were placed out of house.

1958: Giguère was ordered by her spiritual leader to start writing on her life and mystical-spiritual experiences.

1968: Giguère formed a prayer group with lay and religious friends.

1971 (August 28): During a pilgrimage with her prayer group to the Marian shrine at Lac Etchémin, the creation of an Army of Mary was revealed to Giguère.

1971: The first contact with French eschatology author, Raoul Auclair, was established; Giguère gets knowledge from him of the Amsterdam apparitions and the messages of the Lady of All Nations.

1973 (March 20): For the first time Giguère met Lady of All Nations-visionary Ida Peerdeman in Amsterdam.

1975 (March 10): Cardinal Maurice Roy of Quebec approved the Army of Mary as a formal Roman Catholic pious association.

1978: Giguère introduced herself as the (mystical) reincarnation of Mary.

1979: The publication of the autobiographical and spiritual writings (“Vie d’amour”) of Marie-Paule Giguère started.

1983: Major land acquisitions were realized in Lac-Etchémin for the creation of a major devotional complex for the movement.

1987 (February 27): The congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith declared the writings of the movement to be in “major and severe error.”

1987 (May 4): A declaration by archbishop Louis-Albert Vachon of Quebec called the Army of Mary schismatic; it ceased to be a Catholic association.

1988 (March 2): An appeal by the movement to annul the declaration of May 4, 1987 was rejected by the Canadian archbishop.

1991 (20 April): The Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura in Rome confirmed the declaration of May 4, 1987; it was the ‘final’ decision in the appeal of the Army of Mary to the verdict of being schismatic.

1997: Giguère is elected as Superior-General of the Community.

1998: The sympathizing Canadian bishops of Antigonish and Alexandria-Cornwall secretly ordained Army of Mary priests.

2001 (June 29): A doctrinal note of the Canadian Bishops Conference on the Army of Mary stated that the doctrines are contrary to those of the Catholic Church.

2002 (May 31): Bishop Punt of Haarlem-Amsterdam declared the Amsterdam apparitions and messages for authentic; he rejected the pretentions of Marie-Paule regarding the devotion of the Lady of All Nations/Peoples within her movement.

2007 (March 26): Archbishop Marc Ouellet of Quebec stated that the teachings of the Army of Mary are false and that its leaders are excluded form the Catholic Church.

2007 (May 31): Padre Jean-Pierre, superior Father of the movement and newly called the “Church of John,” promulgated the dogma of Mary Coredemptrix, Mediatrix and Advocate under the title of Lady of All Peoples.

2007 (July 11): The Roman Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith excommunicated the regular members and ordained deacons and priests of the Community of the Lady of All Peoples; the movement was judged as “heretical.”

2013: Visionary Giguère, old and bedridden, was supposed to pass away on her birthday, September 14, day of the Holy Cross; the movement keeps low profile.

2015 (April): Visionary Giguère died at age 93.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Marie-Paule Giguère was born in the French Canadian municipality of Sainte-Germaine du Lac-Etchemin (sixty miles southeast of Quebec) on September 14, 1921. Despite an early wish to live a celibate religious life, she was advised against that course by the Church. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917- 1997 ) who worked at various jobs and also went into local politics. In 1948, they moved to the town Saint-Georges de Beauce. A life full of sickness and suffering for both her and her husband ensued. Her marital life proved to be so problematic (a “nightmare” in her words) that it led to a divorce in 1957 and an out-of-home placement of her five children (André Louise, Michèle, Pierre, and Danielle). However, much later, after she had established the Army of Mary, she partially reconciled with her husband when he became a member of the movement. Meanwhile, while trying to overcome her traumas by giving a place to the celestial voices she had been hearing since she was twelve, Giguère was increasingly drawn into Marian spirituality and devotionalism. Although Giguere had been hearing certain “interior voices” since her teenage years, these mystical encounters increased significantly after 1957. The unveiling of her providential destiny, which was first announced to her in 1950, finally took place in 1958. While hearing voices and receiving messages from Jesus Christ and Mary, she started writing down her life story and started interpreting the mystical phenomena she was experiencing. The titles of her autobiographical volumes, such as Vie Purgative (Purgative Life), Victoire (Victory), and Vie Céleste (Heavenly Life), indicate the progressive transformations she experienced.

Quebec) on September 14, 1921. Despite an early wish to live a celibate religious life, she was advised against that course by the Church. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917- 1997 ) who worked at various jobs and also went into local politics. In 1948, they moved to the town Saint-Georges de Beauce. A life full of sickness and suffering for both her and her husband ensued. Her marital life proved to be so problematic (a “nightmare” in her words) that it led to a divorce in 1957 and an out-of-home placement of her five children (André Louise, Michèle, Pierre, and Danielle). However, much later, after she had established the Army of Mary, she partially reconciled with her husband when he became a member of the movement. Meanwhile, while trying to overcome her traumas by giving a place to the celestial voices she had been hearing since she was twelve, Giguère was increasingly drawn into Marian spirituality and devotionalism. Although Giguere had been hearing certain “interior voices” since her teenage years, these mystical encounters increased significantly after 1957. The unveiling of her providential destiny, which was first announced to her in 1950, finally took place in 1958. While hearing voices and receiving messages from Jesus Christ and Mary, she started writing down her life story and started interpreting the mystical phenomena she was experiencing. The titles of her autobiographical volumes, such as Vie Purgative (Purgative Life), Victoire (Victory), and Vie Céleste (Heavenly Life), indicate the progressive transformations she experienced.

In her journalistic work for magazines and radio during the 1950’s, she used the pen name Marie-Josée. After 1958, she referred to herself as Marie-Paule (although also sometimes “Mère Paul-Marie”). She established a foundation for moral support to other organizations and to stimulate priestly vocations under the name Mère Paul-Marie.

After participating in a group visit to an existing small Marian shrine on the edge of Lake Etchemin in the evening on August 28, 1971, Marie-Paule received a revelation confirming the necessity of creating an Army of Mary (“Armée du Marie”). She started the new religious community with approximately seventy five like-minded devotees. This new Army of Mary group was meant to be an alternative to the existing Legion of Mary ( Legio Mariae ), the lay Marian world association founded in 1921 in which she had been involved previously. Against the backdrop of the 1960s counterculture and the Second Vatican Council, her new Army required for members to manifest “personal interior reform” toward the traditional devotional trinity: “The Triple White” (the Eucharist, Mary and the Pope) was to be performed in “an authentically Christian way of life” and also in “fidelity to Rome and the Pope.”

Through the appeal of her messages, her charismatic gifts and her vocal and singing capacities, she enthused her followers and established a successful traditionalist grass-roots Marian movement. The next year, in 1972, a Quebec priest, Philippe Roy, joined the movement and became its director.

It was due to the friendship (through their joint Militia of Jesus Christ membership) of Marie-Paule with an important Church official, the Dutch-Belgian Jean-Pierre van Lierde, sacrista/vicar general of the Vatican State and supporter of the Amsterdam apparitions, that Québecqois archbishop Maurice Roy was persuaded to acknowledge the movement in 1975 as a formal pious association of the Church. This move was the result of inattention and eagerness from his side towards religious initiatives in a time of decay of the Church. He neglected – whether or not intentiously – to conduct a proper investigation on the movement’s ideological stance. Presumably due to the fact that the texts with Marie-Paule’s views were not published before 1979, the movement remained under the radar and unknown to those who were responsible to check its compliance with the doctrines of the faith. It has been reported that Van Lierde stimulated both visionaries, Ida and Marie-Paule, to meet each other.

As a consequence of recognition by the Church, the now formalized movement peaked in the following years. In about ten years the movement, stimulated by their own proselytes and official status, the movement started to expand outside Quebec, finding some thousands of devotees (and not more than that) distributed over approximately twenty (Western) countries.

In 1977, due to another revelation to Marie-Paule, the Militia of Jesus Christ was introduced in Canada and connected to the Army of Mary. That year 200 soldiers of the Army also joined the Militia Christi. The Militia, a chivalric neo-order for stimulating Marian devotion and doing social work, was instituted in France in 1973 without approval of the Church. In 1981, Giguère’s Army of Mary movement modernized its name as the Family and the Community of the Sons and Daughters of Mary. Although this renaming seems less offensive, it connected the movement or “Family” provocatively and directly to its leader, Mary (her reincarnation), or Marie-Paule.

The growth of the movement since the 1970’s also quietly generated a strong flow of financial resources. The Quebec community was therefore taken by surprise when in 1983 major land acquisitions and investments took place in and around Lac-Etchemin in order to create a world center for the Army of Mary and its Militia. These expansions created for the sectarian group a closed, supportive, social and ideological habitat, one that was hostile to external world and authorities and one where not only the ideas grew and the mission started but also the religious practice took place. The group not only organized itself internally. It also created a semi-independent geographical zone, the international center, with monastery-like housing facilities, noviciate, retraites (Spiri-Maria-Alma and Spiri-Maria-Pietro), ateliers, guest houses, press office and radio station, in and around Lac-Etchemin, but mainly at the Route du Sanctuaire 626.

“ Misled” by the formal approbation of the Church, a part of the following did not fully realize the implications of the new  teachings when they were published. But, from the early 1980s, people became increasingly worried after closely reading the first published volume of Marie-Paule’s Vie d’Amour. In addition, regional authorities and media were alarmed by the building activities of the Army at the edge of the lake, activities that strengthened the idea of an institutionalizing, self-supportive sectarian community. Nonetheless, it was only after a stream of newspaper articles expressing astonishment at what was actually professed in her scriptures that the bishop of Quebec realized his misjudgment and started to take action against the doctrinal deviations. It caused the new archbishop of Quebec to withdraw the approval of his predecessor. On May 4, 1987, he declared the movement schismatic and disqualified it as a Catholic association because of its false teachings. The Vatican judged their doctrine to be “heretical.” To be completely sure, the archbishop-to-be asked Cardinal Ratzinger to have Marie-Paule’s scriptures also screened by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In a brief note of February 27, 1987, Ratzinger, too, concluded that the movement was in “major and very severe error.” The particular concern was the idea of the alleged existence of an Immaculate Marian Trinity, in which Mary is no longer just Mother of the Son of God, but the divine spouse of God. As a consequence, the theological exegesis of Marie-Paule’s writing by her “theologian,” Marc Bosquart, was likewise condemned. Hence, the Army was forbidden to organize any celebration or to propagate their devotion for the Lady of All Peoples. Priests from the Quebec diocese who got involved would be removed from their priestly functions, although the penalty of excommunication or condemnation was not yet called for.

teachings when they were published. But, from the early 1980s, people became increasingly worried after closely reading the first published volume of Marie-Paule’s Vie d’Amour. In addition, regional authorities and media were alarmed by the building activities of the Army at the edge of the lake, activities that strengthened the idea of an institutionalizing, self-supportive sectarian community. Nonetheless, it was only after a stream of newspaper articles expressing astonishment at what was actually professed in her scriptures that the bishop of Quebec realized his misjudgment and started to take action against the doctrinal deviations. It caused the new archbishop of Quebec to withdraw the approval of his predecessor. On May 4, 1987, he declared the movement schismatic and disqualified it as a Catholic association because of its false teachings. The Vatican judged their doctrine to be “heretical.” To be completely sure, the archbishop-to-be asked Cardinal Ratzinger to have Marie-Paule’s scriptures also screened by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. In a brief note of February 27, 1987, Ratzinger, too, concluded that the movement was in “major and very severe error.” The particular concern was the idea of the alleged existence of an Immaculate Marian Trinity, in which Mary is no longer just Mother of the Son of God, but the divine spouse of God. As a consequence, the theological exegesis of Marie-Paule’s writing by her “theologian,” Marc Bosquart, was likewise condemned. Hence, the Army was forbidden to organize any celebration or to propagate their devotion for the Lady of All Peoples. Priests from the Quebec diocese who got involved would be removed from their priestly functions, although the penalty of excommunication or condemnation was not yet called for.

Despite all measures, the movement did not seem to decline. On the contrary, its mission continued as members were convinced of the real truth that was revealed to them. In 2001, the media frequently reported that the movement consisted of 25,000 followers. In fact, the movement never reached that size; the movement itself estimated in 1995 that its membership was “several thousand” followers spread over fourteen countries. This included forty brothers/seminarians, forty three priests as The Sons of Mary (“Les Fils de Marie”), and 75 celibate women known as members of The Daughters of Mary (“Les Filles de Marie”). There were convents in Green Valley and Little Rock. Most of the following were located in Canada and the U.S., with a few hundred in the Western part of Europe. For example, in the Netherlands a group of approximately twenty devotees was and is active in a Nijmegen-based prayer group. After the interventions of the Church, many left the movement again, and a smaller group of dedicated followers remained.

2007 seems to have been a pivotal year for the movement. When the movement and its teachings were declared false in March, the group strongly reacted with a series of ceremonial feasts (May 31–June 3). During this period, their own new “pope,” Padre Jean-Pierre, promulgated the dogma of Mary/Lady as Coredemptrix, canonized the group’s first saint, Raoul-Marie, and ordained six priests. As a planned final blow to the movement, the Vatican excommunicated the whole movement in July. Since then, not much seems to have changed in community’s policy, although the various measures did winnow the following and, presumably, reduced its means for mission and propaganda. Following this period, the power of Marie-Paule appears to have declined while the influence of her theologians increased. The teachings became increasingly esoteric and the idea of an alternative Church of John (in place of the “degenerated” Church of Petrus) came into being (Martel 2010). After their excommunication, the core following has become more convinced on the demise of the Roman Church of Petrus and the false path the bishop walks by dancing to the tune of Rome and leaving out the major line within the prayer that was given by the Lady. That line (“the Lady who once was Mary”) demonstrated that Marie-Paule was indeed the incarnated, new Mary and Co-Redemptor.

A passing of bedridden Marie-Paule had been predicted for her birthday on September 14, 2013. The prophecy was based on an

“apocalyptic calculation” of verse 5-6 of the book of Revelation. Her passing was expected to take place 1260 days after the start of the Terrestrial Paradise on April 4, 2010. The day passed peacefully, however.

“apocalyptic calculation” of verse 5-6 of the book of Revelation. Her passing was expected to take place 1260 days after the start of the Terrestrial Paradise on April 4, 2010. The day passed peacefully, however.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Community of the Lady of All Peoples regards itself a Catholic movement claiming “ Providential Work with Universal Dimensions.” With this phrasing and by positioning their “Church of St. John” in opposition to the apostolic Catholic tradition of the “Church of St. Peter,” they have distanced themselves from Rome. The group has been declared “non-Catholic” by the Vatican, as it is understood to be a schismatic movement with excommunicated leaders and “heretic” writings. Although it still spreads its theological material, which continues to assert its fidelity to Rome and the Pope, its actual practices are the opposite. The former Army/present-day Community is better understood as a visionary movement with Catholic roots that transformed into a millennial sectarian group with mixed Catholic-esoteric beliefs. They regard their deviating views as Catholic but with “extra” beliefs, for which the Roman Church, they explain, “is not yet ready.”

At the outset, the Army of Mary seemed to be more a new Catholic revival movement reacting to debated modernizations of the Church after the Second Vatican Council. As the role and position of the idiosyncratic visionary and leader Giguère became stronger, especially after her election as Superior-General in 1997, the movement showed more and more characteristics of a sectarian movement. The mystic prose was not focused on God, but became fully centered on Giguère as Mary and/or the Lady of All Peoples reincarnated in her. The Mother (Mary/Marie-Paule) is in their view equal to the Father and of the same nature as Jesus Christ, and so is represented in the Eucharist. Maria has become God for them. Given that position, the theology was not complementary to Christology or Mariology; it was replacement with a completely new doctrine. A growing distinction between adherents and non-adherents to her Vie d’Amour theology came to the surface, leaving less and less space for individual mysticism. New revelations to Marie-Paule, who had first-hand experiences with the divine, changed the movement into a cult of a revelatory kind, where the truth is revealed and individual seekers have to become strict adherents. However, the Army of Mary/Community is in fact not fully a closed cult. The Community has a particularized revealed truth that only partly rejects the paradigms of the Church. It elaborated on the public revelation of the Roman Catholic Church and on fundamental principles, but it started to deviate on some of the basic teachings and the course set out by the Vatican. The Army of Mary claims their teachings overrule verified truth, as mediated by Mary herself and adapted to the modern state of the world, despite their rejection and suppression by the ecclesiastical powers and institutions.

Although Giguère is the divine medium, she did not produce a full exegesis on all dimensions of her mystic experiences. Therefore, two “theologians” were appointed to systematize, elaborate and interpret her mystic writings into a more coherent theology and to elaborate her providential role within the universality of Christianity. This development enhanced the group’s sectarian character. Although the theology is Christian-based, it integrates millennial views, with Marie-Paule as savior (Mary/God), in combination with heretical theological, gnostic esoteric and cosmological teachings. The themes were documented in detail in the research of the movement’s teachings by the Canadian theologian Raymond Martel in 2010 . He described the theology of the Quebec movement as the making of a “Marian gnosis.” In this way the Quebec teachings also deviated from the apocalyptic and end-time interpretations of Hans Baum (1970) for whom the Amsterdam messages are anti-gnostic.

The basis of the theology, redemptive prophecies and eschatology, can be traced to two major sources. The first is Marie-Paule’s scriptures. These include a “revelation” consisting of a series of fifteen volumes titled Life of Love (Vie d’Amour), an auto-biographical and auto-hagiographical corpus of thousands of pages that deals with her life story and mystical experiences. Reading Theresia of Lisieux’s inspirational autobiography, The Story of a Soul (L’histoire d’une âme), and being active as a writer for journals, made Marie-Paule think of putting her life to paper. In 1958, her spiritual superior told her to commence. The text was said to be partly dictated by the Lord himself, not by means of voices or apparitions but by a communication, as she stated, “from spirit to spirit,” initially at the “level of the heart” and later at the level “of the head,” underlining in this way their concurrence. The books form the paradigm and the underpinning of her concept of the Lady of All Peoples and her role within the divine salvific plan. The works also ultimately position Giguère as the embodied appearance of the Lady of All Peoples.

The French Raoul Auclair (1906-1996), radio journalist and author of books on Nostradamus, apparitions, revelations and  eschatology (nicknamed “The Poet of the End of the Times”) got notice of the Amsterdam apparitions. By 1966, he had already organized a successful conference on the Amsterdam Lady in Paris where he tried to connect the outcome of the Second Vatican Council on Mary to the Amsterdam messages. He stated that all issues that were brought up during and around the Council had to be interpreted as a confirmation of what was revealed in the Amsterdam messages. The text of the conference was published under the transparent title, La Dame de tous les peuples, and he became the single major international propagandist for the Amsterdam cultus. The French book found its way to Catholic Quebec and was given to Giguère by a friend. After rereading it several times, she recognized the resemblances in the messages she and Peerdeman received and became convinced of the structured connection of both mystic experiences. This idea ultimately brought Auclair and Giguère into contact with each other in 1971. Five years later he joined the Army. In those years, with the Church’s condemnation of the Amsterdam cultus and suppression of its local devotional practice, Marie-Paule’s interest in the Lady of All Nations became stronger. The universality of the Amsterdam messages matched her divine promptings and personal ambitions for a global Marian movement within the Marian era. As a result Marie-Paule wanted to meet visionary Peerdeman. In 1973, 1974 and 1977, she visited the Amsterdam shrine of the Lady of All Nations. Her last visit proved to constitute a new sequel to the Amsterdam apparitions and created an impulse for a shift of the core of cultus to Quebec. Marie-Paule claimed that during mass at the shrine in Amsterdam the visionary Peerdeman pointed at her (Giguère) while saying, “She is the Handmaiden.” This was taken as proof of what was proclaimed in the Lady’s fifty first message, in which Mary announced her return to earth: “I will return, but in public.” This moment was understood to be a recognition of The Lady of All Nations in the person of Giguère by the visionary Peerdeman. Through this maneuver, Marie-Paule retrospectively appropriated the prophesized public return of Mary on Earth ( Messages 1999: 151). Hence, Giguère claimed the devotion of the Lady in Lac-Etchemin to be the sole continuation of the Amsterdam cultus.

eschatology (nicknamed “The Poet of the End of the Times”) got notice of the Amsterdam apparitions. By 1966, he had already organized a successful conference on the Amsterdam Lady in Paris where he tried to connect the outcome of the Second Vatican Council on Mary to the Amsterdam messages. He stated that all issues that were brought up during and around the Council had to be interpreted as a confirmation of what was revealed in the Amsterdam messages. The text of the conference was published under the transparent title, La Dame de tous les peuples, and he became the single major international propagandist for the Amsterdam cultus. The French book found its way to Catholic Quebec and was given to Giguère by a friend. After rereading it several times, she recognized the resemblances in the messages she and Peerdeman received and became convinced of the structured connection of both mystic experiences. This idea ultimately brought Auclair and Giguère into contact with each other in 1971. Five years later he joined the Army. In those years, with the Church’s condemnation of the Amsterdam cultus and suppression of its local devotional practice, Marie-Paule’s interest in the Lady of All Nations became stronger. The universality of the Amsterdam messages matched her divine promptings and personal ambitions for a global Marian movement within the Marian era. As a result Marie-Paule wanted to meet visionary Peerdeman. In 1973, 1974 and 1977, she visited the Amsterdam shrine of the Lady of All Nations. Her last visit proved to constitute a new sequel to the Amsterdam apparitions and created an impulse for a shift of the core of cultus to Quebec. Marie-Paule claimed that during mass at the shrine in Amsterdam the visionary Peerdeman pointed at her (Giguère) while saying, “She is the Handmaiden.” This was taken as proof of what was proclaimed in the Lady’s fifty first message, in which Mary announced her return to earth: “I will return, but in public.” This moment was understood to be a recognition of The Lady of All Nations in the person of Giguère by the visionary Peerdeman. Through this maneuver, Marie-Paule retrospectively appropriated the prophesized public return of Mary on Earth ( Messages 1999: 151). Hence, Giguère claimed the devotion of the Lady in Lac-Etchemin to be the sole continuation of the Amsterdam cultus.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

In order to give public access to Our Lady of All Peoples in Lac-Etchemin, a church was built within the international Spiri-Marie Center complex. The complex is more a headquarters of an international movement than a dedicated shrine for the Lady of All Peoples or her reincarnation. In an adjacent building to the church, a big shop where books, images, DVD’s are stacked and show the missionary character of the center. Candles, rosaries and all kinds of other devotional material also can be bought for home use or in the Spiri-church. The morphology of the objects seems to be mainstream Catholic, although the symbolism is adapted to the Community’s teachings. Many of the devotional practices are to a large extent in line with those of the formal Catholic Church. The whole décor of the interior is directly inspired by the “original” Amsterdam shrine of the Lady and its imagery. However, a closer look at the décor also shows the symbolism and texts of the movement’s heretical doctrines. For example, one

In order to give public access to Our Lady of All Peoples in Lac-Etchemin, a church was built within the international Spiri-Marie Center complex. The complex is more a headquarters of an international movement than a dedicated shrine for the Lady of All Peoples or her reincarnation. In an adjacent building to the church, a big shop where books, images, DVD’s are stacked and show the missionary character of the center. Candles, rosaries and all kinds of other devotional material also can be bought for home use or in the Spiri-church. The morphology of the objects seems to be mainstream Catholic, although the symbolism is adapted to the Community’s teachings. Many of the devotional practices are to a large extent in line with those of the formal Catholic Church. The whole décor of the interior is directly inspired by the “original” Amsterdam shrine of the Lady and its imagery. However, a closer look at the décor also shows the symbolism and texts of the movement’s heretical doctrines. For example, one  can pray with a combined image of Jesus and Mary that suggests that Mary is present in the eucharist. The central devotional practice is dedicated to the “Triple White” (the eucharist, the Immaculate Mary, and the Pope) through which the sanctification of one’s soul should be realized, inspire the world and the spread the evangelical message of love and peace in anticipation of the return of Christ. Within the cultus no public Marian apparition rituals are known; all messages and appearances seem to be privately received by Giguère.

can pray with a combined image of Jesus and Mary that suggests that Mary is present in the eucharist. The central devotional practice is dedicated to the “Triple White” (the eucharist, the Immaculate Mary, and the Pope) through which the sanctification of one’s soul should be realized, inspire the world and the spread the evangelical message of love and peace in anticipation of the return of Christ. Within the cultus no public Marian apparition rituals are known; all messages and appearances seem to be privately received by Giguère.

In the Spiri-church, the devotion for the “Quinternity” is presented. The sacred number, 55 555, was introduced into the teachings as the basis for explaining the logic of the Marian Trinity, consisting of the Immaculate Mary, Marie-Paule, and the Holy Spirit. The devotion states that the combination of the Marian Trinity with the classic trinity (the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit) creates a total of five “elements,” as the Holy Spirit is regarded as the same for both Trinities. This ensemble is said to be one as well, as the feminine (the immaculate) is also present in God. Their explanation states that the first coming of the Immaculate Mary is symbolized in the first number 5, and the second coming (Marie-Paule) is represented in double five’s. The double fives represents her actions with the “True Spirit,” namely the Holy Spirit of Mary, a work that started in the year 2000 and which will realize the number 555 when it is finished. This will occur when the new millennium has arrived. In the movement’s systematization, the numbers are supposed to connect the cultus to its origins and close the circle. It would place the formation of the cultus in line with what God reportedly prophesied to Giguère in 1958 about her crucifixion and reincarnation, and about the existence of a Marian trinity. The full number of 55 555 then (the Quinternity ) is the symbol of the actions of the Lady of All Peoples with the True (Marian) Holy Spirit. The figure is presented as a holy number that symbolizes future victory over evil (symbolized in the human number of the beast (666)) and the conditional coming of the new millennium (cf Baum 1970:49-63).

well, as the feminine (the immaculate) is also present in God. Their explanation states that the first coming of the Immaculate Mary is symbolized in the first number 5, and the second coming (Marie-Paule) is represented in double five’s. The double fives represents her actions with the “True Spirit,” namely the Holy Spirit of Mary, a work that started in the year 2000 and which will realize the number 555 when it is finished. This will occur when the new millennium has arrived. In the movement’s systematization, the numbers are supposed to connect the cultus to its origins and close the circle. It would place the formation of the cultus in line with what God reportedly prophesied to Giguère in 1958 about her crucifixion and reincarnation, and about the existence of a Marian trinity. The full number of 55 555 then (the Quinternity ) is the symbol of the actions of the Lady of All Peoples with the True (Marian) Holy Spirit. The figure is presented as a holy number that symbolizes future victory over evil (symbolized in the human number of the beast (666)) and the conditional coming of the new millennium (cf Baum 1970:49-63).

Apart from pilgrimages to the Spiri-Marie center, most of the devotional practices among the adherents take place in the various countries locally within prayer groups. These groups usually meet in informally constructed chapels in houses or garages, as the movement is not allowed to make use of Catholic church buildings. The clean and smooth Spiri-Maria buildings show few decorations and symbolism and do not have burning candles or offerings. An adapted (including a Holy Spirit) painting of the Lady of All Peoples is positioned next to the altar. A sign explains for the visitors the “quinternity.”

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

New branches have been added to the original Army of Mary since 1980. The present overall Community of the Lady of All Peoples consists of five “works” or branches:

● The Army of Mary (l’Armée de Marie ), established in 1971.

● The Family of Sons and Daughters of Mary (La Famille des Fils et Filles de Marie), established in the early 1980s.

● The Community of Sons and Daughters of Mary (la Communauté des Fils et Filles de Marie) established in 1981. This organization is a religious, pastoral order of priests and sisters, with Marie-Paule as Superior-General since 1997.

● Les Oblats-Patriotes, established in 1986 (August 15). The goal of this organization is renewal of society.

● The Marialys Institute, established in 1992. This organization serves priests who are not part of the Community but share the doctrines.

Those outside of the movement, the media and the Roman Catholic Church, usually still depict the overall movement in a reductionist way as the Army of Mary.

From the beginning, Marie-Paule Giguère has been the central figure. There is considerable information about her past due to her writings. There is less information about her later life as her movement came under pressure, she appeared less often in public, and the group became a more closed sect. Most of the contact with the outside world took place through her assistant, the Belgian sister Chantal Buyse, who also takes care of her hospitalization.

When in 1978 Raoul Auclair moved to Quebec and became the editor of L’Etoile (The Star), the then journal of the movement (since 1982 Le Royaume ), his role as intellectual within the Community started to rise. Ultimately he became the central theologian and interpreter of the movement, for which he was canonized by the Community after his death.

Since 2007, Father Jean-Pierre Mastropietro, wearing a Byzantine crown, has been “acting like a pope” according to the Catholic Church. Father Jean-Pierre is the head of the Church of John, the Church of Love, which is described by the movement as a “transmutation” of the Roman Church of Peter.

Church. Father Jean-Pierre is the head of the Church of John, the Church of Love, which is described by the movement as a “transmutation” of the Roman Church of Peter.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

As of 2007, the Army of Mary was excommunicated, and the movement has been placed outside the Catholic Church and will not be allowed to return. The question is whether the Roman Catholic Church will fully ignore the movement or will continue to actively oppose it as the Community seems to still be able to contact and attract the “ignorant.” Presumably the Church will take a practical stance and will wait for the death of the visionary who reached the age of 92 in 2013, is half paralyzed, has mentally deteriorated, and lives in “great agony.” It is likely that after the death of the visionary, their leader and reincarnated Mary, the movement will fall into a crisis. However, followers state that then her Church will be taken over by others within the movement.

A second issue is the relation with the Amsterdam-based shrine of the Lady of All Nations, the inspirational apparitional source for Giguère. It has become a formally acknowledged apparitional site through the recognition by Bishop Jozef Punt of Haarlem-Amsterdam. Both sites and devotions still stand in competition with one another. The organization in Amsterdam is, given its official recognition, distancing itself more strongly than ever from Giguère and her movement. Within the movement the number of references to its roots, the Amsterdam visions of Ida Peerdeman of the Lady of All Nations (instead of Peoples) has been reduced to a functional minimum and is usually limited to texts of the messages and the transfer of the status of being chosen from Ida to Marie-Paule. Nevertheless some of Marie-Paule’s following does not reject Amsterdam and its messages, as this is perceived as the basis for Marie-Paule’s church. They do, however, resent the change of the basic verse line in the prayer that was given by the Lady.

REFERENCES

Au Sujet de l’Armée de Marie. 2000. Revue Pastorale Quebec 112, no. 8 (June 26).

Auclair, Raoul. 1993. La fin des temps . Quebec: Ed. Stella.

Baum, Hans. 1970. Die apokalyptische Frau aller Völker. Kommentare zu den Amsterdamer Erscheinungen en Prophezeiungen . Stein am Rhein: Christiana-Verlag.

Bosquart, Marc . 2003. Marie-Paule and Co-Redemption . Lac-Etchemin: Ed. du Nouveau Monde.

Bosquart, Marc . 2003. The Immaculate, the Divine Spouse of God . Lac-Etchemin: Ed. du Nouveau Monde.

Bosquart, Marc. 2002. New Earth New Man . Lac-Etchemin: Ed. du Nouveau Monde.

Communauté de la Dame de Tous Les Peuples. n.d. Accessed from http://www.communaute-dame.qc.ca/oeuvres/OE_cinq-oeuvres_FR.htm on 17 May 2013.

De Millo, Andrew. 2007. “Six Catholic Nuns In Arkansas Excommunicated For Heresy.” The Morning News , September 26, 2007.

“Note Doctrinale des Évêques Catholiques du Canada sur l’Armée de Marie.” n.d. Accessed from www.cccb.ca/site/Files/NoteArDeMarie.html on 17 May 2013.

“Declaration of the bishop of Haarlem-Amsterdam on the Amsterdam and Quebec Devotions.” 2007. Accessed from http://www.de-vrouwe.info/en/notice-regarding-the-qarmy-of-maryq-2007 on 20 May 2013.

“Declaration of the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith. 2007 ( July 11). Accessed from www.cccb.ca/site/images/stories/pdf/decl_excomm_english.pdf on 17 May 2013.

Geoffroy, Martin and Jean-Guy Vaillencourt. 2001. ‘Les groupes catholiques intégristes. Un danger pour les institutions sociales?’ Pp. 127-41 i n La peur des sects , edited by Jean Duhaime and Guy-Robert St-Arnaud. Montréal: Editions Fides.

Kruk, Ester. 2003. Zoals sneeuwvlokken over de wereld dwarrelen. De hedendaagse devotie rond Maria, de Vrouwe van Alle Volkeren. Amsterdam: Aksant.

Laurentin, René and Patrick Sbalchiero eds. 2007. Pp. 1275-76 in Dictionnaire des “apparitions“ de la Vierge Marie. Inventaire des origines à nos jours. Méthodologie, bilan interdisciplinaire, prospective . Paris: Fayard.

Marie-Paule [Giguère]. 1979-1987. Vie D’Amour , 15 vols. Lac-Etchemin: Vie D’Amour Inc.

Margry, Peter Jan. 2012. “Mary’s Reincarnation and the Banality of Salvation: The Millennialist Cultus of the Lady of All Nations/Peoples.” Numen: International Review for the History of Religions 59:486-508.

Margry, Peter Jan . 2009a. “Paradoxes of Marian Apparitional Contestation: Networks, Ideology, Gender, and The Lady of All Nations.” Pp. 182-99 in Moved by Mary: The Power of Pilgrimage in the Modern World , edited by Anna-Karina Hermkens, Willy Jansen, and Catrien Notermans. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Margry, Peter Jan . 2009b. “Marian Interventions in the Wars of Ideology: The Elastic Politics of the Roman Catholic Church on Modern Apparitions.” History and Anthropology 20:245-65.

Margry, Peter Jan. 1997. “Amsterdam, Vrouwe van Alle Volkeren.” Pp. 161-70 i n Bedevaartplaatsen in Nederland , volume 1, edited by Peter Jan Margry and Charles Caspers. Hilversum: Verloren.

Martel, Raymond. 2010. La face cachée de l’Armée de Marie . Anjou, Quebec: Fides.

Matter, Ellen A. 2001. “Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in the Late Twentieth Century: Apocalyptic, Representation, Politics.” Religion 31:125-53.

Messages of the Lady of All Nations, The New Edition . 1999. Amsterdam: The Lady of All Nations Foundation.

Paul-Marie, Mère. 1985. Lac-Etchemin. La Famille des Fils et Filles de Marie . Limoilou: Vie D’Amour.

Poulin, Andree, ‘Achats énigmatiques des terrains’, in La Voix de Ste-Germaine , 31 January 1984.

Robinson, Bruce. n.d. “Roman Catholicism. The Army of Mary: An Excommunicated Roman Catholic Group.” Accessed from http://www.religioustolerance.org/army_mary.htm on 9 June 2013.

Le Royaume. Périodique bimestriel christique, marial et oecuménique, organe de formation spirituelle et d’information de la Communauté de la Dame de Tous les Peuples . Accessed from http://www.communaute-dame.qc.ca/actualites-royaume/fr/archives.html.

Post Date:

28 October 2013

in Lebanon and migrated to Canada around 1990 (Yonke 2010). She resided in East Windsor in Ontario at the time her messages from the Virgin Mary began (Willick 2010). Ibrahim attended the St. Ignatius of Antioch Church, an Orthodox Christian church.

in Lebanon and migrated to Canada around 1990 (Yonke 2010). She resided in East Windsor in Ontario at the time her messages from the Virgin Mary began (Willick 2010). Ibrahim attended the St. Ignatius of Antioch Church, an Orthodox Christian church. discovered that it was dispensing oil. It was a request from Mary that led her to then build an enclosed pedestal on her front lawn to display the statue. Visitors began to appear immediately, and some brought flowers. According to Ibrahim, Mary was pleased. She states that the statue was smiling and secreting oil. Shortly after the statue was placed outside the home, Ibrahim began to report oil secreting from her own hands. Ibrahim stated the oil came from the statue and was of the Virgin Mary (Yonke 2010). Daily attendance at the statue rose to as many as 1,000 visitors per day (Willick 2010).

discovered that it was dispensing oil. It was a request from Mary that led her to then build an enclosed pedestal on her front lawn to display the statue. Visitors began to appear immediately, and some brought flowers. According to Ibrahim, Mary was pleased. She states that the statue was smiling and secreting oil. Shortly after the statue was placed outside the home, Ibrahim began to report oil secreting from her own hands. Ibrahim stated the oil came from the statue and was of the Virgin Mary (Yonke 2010). Daily attendance at the statue rose to as many as 1,000 visitors per day (Willick 2010). Virgin Mary. Although in place for a very short time, the statue in Windsor became a pilgrimage site for believers in Marian apparitions. Visitors reported being overcome with emotion upon simply looking at the statue. Worshipers also repeated prayers, such as the Hail Mary, and held religious items such as rosaries and Bibles while worshiping. Even after the statue had been placed in the St. Charbel Maronite Catholic Church, believers attested to the statue’s secreting of tears: “I swear to God, honestly — we’re in church right now — by the fourth decat you could see it, it was just so clear,” Ms. Rizk said. “The tear formed on the top of the eye and dripped down and stopped at the bottom of the eye. It was a statue one second and then it became a miracle, right in front of my eyes” (Yonke 2010).

Virgin Mary. Although in place for a very short time, the statue in Windsor became a pilgrimage site for believers in Marian apparitions. Visitors reported being overcome with emotion upon simply looking at the statue. Worshipers also repeated prayers, such as the Hail Mary, and held religious items such as rosaries and Bibles while worshiping. Even after the statue had been placed in the St. Charbel Maronite Catholic Church, believers attested to the statue’s secreting of tears: “I swear to God, honestly — we’re in church right now — by the fourth decat you could see it, it was just so clear,” Ms. Rizk said. “The tear formed on the top of the eye and dripped down and stopped at the bottom of the eye. It was a statue one second and then it became a miracle, right in front of my eyes” (Yonke 2010). through direct contact with the statue itself, with the hand of Ibrahim, or with the hands of those who did touch the statue. Ibrahim only allowed a handful of visitors actually touch the statue. These lucky few would place their hands on the heads of other visitors and bless them. Visitors brought with them ziploc bags, cotton balls, and makeup remover to collect the Virgin’s tears of oil and bring them home (Wilhelm 2010). Sometimes Ibrahim would use her hands to make a cross with the on the forehead of visitors. One woman described the experience as overwhelming: “When she touched me, I just felt overwhelmed and everything seemed to come out,” said Rosanne Paquette. “I felt this warmth, and it was unbelievable.” Another woman testified that her teenage granddaughter was cured of leukemia after Ibrahim anointed her with the oil: “She just put the oil on her, prayed for her…. The doctor said her blood, everything was normal” (Willick 2010).

through direct contact with the statue itself, with the hand of Ibrahim, or with the hands of those who did touch the statue. Ibrahim only allowed a handful of visitors actually touch the statue. These lucky few would place their hands on the heads of other visitors and bless them. Visitors brought with them ziploc bags, cotton balls, and makeup remover to collect the Virgin’s tears of oil and bring them home (Wilhelm 2010). Sometimes Ibrahim would use her hands to make a cross with the on the forehead of visitors. One woman described the experience as overwhelming: “When she touched me, I just felt overwhelmed and everything seemed to come out,” said Rosanne Paquette. “I felt this warmth, and it was unbelievable.” Another woman testified that her teenage granddaughter was cured of leukemia after Ibrahim anointed her with the oil: “She just put the oil on her, prayed for her…. The doctor said her blood, everything was normal” (Willick 2010). Neighbors disliked the large increased traffic and noise in the neighborhood, which only increased when the U.S. began to report about it (Caldwell 2010). Neighbors quickly complained to the city and organized a petition against the statue that was delivered to municipal officials. Due to the lack of a building permit and to building code violations, the city gave Ibrahim until November 19 to remove the statue. Ibrahim quickly objected to the city’s notice and collected hundreds of donations and signatures for a petition to save the statue before finally acceding to the city’s demands. Ironically, a city solicitor at the time, George Wilkki, spoke to the media telling them there was an easy solution to the city’s issues with the statue. Ibrahim simply needed to apply for a minor variance and a building permit. Then, the statue could remain at its location in her front yard (Wilhelm 2010).

Neighbors disliked the large increased traffic and noise in the neighborhood, which only increased when the U.S. began to report about it (Caldwell 2010). Neighbors quickly complained to the city and organized a petition against the statue that was delivered to municipal officials. Due to the lack of a building permit and to building code violations, the city gave Ibrahim until November 19 to remove the statue. Ibrahim quickly objected to the city’s notice and collected hundreds of donations and signatures for a petition to save the statue before finally acceding to the city’s demands. Ironically, a city solicitor at the time, George Wilkki, spoke to the media telling them there was an easy solution to the city’s issues with the statue. Ibrahim simply needed to apply for a minor variance and a building permit. Then, the statue could remain at its location in her front yard (Wilhelm 2010).

the elder. He was born with the name Aristide Pierre Maurin in Oultet, France in 1877, the son of French peasant farmers and one of 24 children. Born into a Catholic family, as a young man he considered religious life, joining the Christian Brothers. A creative yet quiet person inspired by French personalist philosophy, especially the work of Emmanuel Mounier, Maurin sought to live a simple and dignified life of manual labor. In 1909, he migrated to Canada and later to the U.S., working in a variety of jobs as a manual laborer, which eventually brought him to New York City.

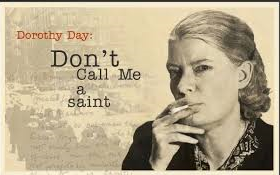

the elder. He was born with the name Aristide Pierre Maurin in Oultet, France in 1877, the son of French peasant farmers and one of 24 children. Born into a Catholic family, as a young man he considered religious life, joining the Christian Brothers. A creative yet quiet person inspired by French personalist philosophy, especially the work of Emmanuel Mounier, Maurin sought to live a simple and dignified life of manual labor. In 1909, he migrated to Canada and later to the U.S., working in a variety of jobs as a manual laborer, which eventually brought him to New York City. in Staten Island, New York. When she voiced her desire to convert to Catholicism and to have their baby baptized, Forster, an atheist who wanted little to do with religion, urged her not to go through with it. The two ended up separating, an experience that Day later described as one of the most painful decisions of her life: choosing the Church over her love for Forster.

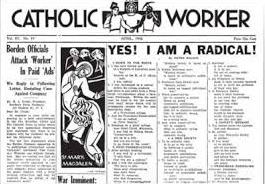

in Staten Island, New York. When she voiced her desire to convert to Catholicism and to have their baby baptized, Forster, an atheist who wanted little to do with religion, urged her not to go through with it. The two ended up separating, an experience that Day later described as one of the most painful decisions of her life: choosing the Church over her love for Forster. personal sacrifice. Over time, their efforts grew into a group of volunteers who lived in a Lower East Side building (eventually called “St. Joseph House”) with people seeking shelter from the streets, running a daily soup line that often stretched down the block and publishing pieces in The Catholic Worker newspaper critiquing the social, spiritual, and personal crises underlying problems, such as poverty and racism. Over time, the newspaper (and the Catholic Worker community) became focused on issues of violence and militarism as well, with the group’s pacifist stance and nonviolent civil disobedience becoming more central to its existence during the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Vietnam War, and into present time.

personal sacrifice. Over time, their efforts grew into a group of volunteers who lived in a Lower East Side building (eventually called “St. Joseph House”) with people seeking shelter from the streets, running a daily soup line that often stretched down the block and publishing pieces in The Catholic Worker newspaper critiquing the social, spiritual, and personal crises underlying problems, such as poverty and racism. Over time, the newspaper (and the Catholic Worker community) became focused on issues of violence and militarism as well, with the group’s pacifist stance and nonviolent civil disobedience becoming more central to its existence during the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Vietnam War, and into present time. newspapers describing their work, began to spring up around the United States. By 1940, over thirty Catholic Worker communities were formed by local groups around the country interested in the kind of work that Day and Maurin described in their newspaper. The movement’s growth was, and has continued to be, decentralized and unorganized. No one’s permission is needed to start a Catholic Worker community, nor do incarnations of Catholic Worker vision and practice need to follow a particular set of rules or models. Indeed, Day’s anarchist past nurtured her commitment to a movement that was informed by those directly involved, which left room for spontaneity and creativity rather than authority and leadership dictating the boundaries for communities. While the de facto leaders of different communities were sometimes familiar with each other, connections between different Catholic Worker communities rarely extended beyond informal friendships.

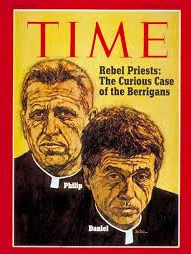

newspapers describing their work, began to spring up around the United States. By 1940, over thirty Catholic Worker communities were formed by local groups around the country interested in the kind of work that Day and Maurin described in their newspaper. The movement’s growth was, and has continued to be, decentralized and unorganized. No one’s permission is needed to start a Catholic Worker community, nor do incarnations of Catholic Worker vision and practice need to follow a particular set of rules or models. Indeed, Day’s anarchist past nurtured her commitment to a movement that was informed by those directly involved, which left room for spontaneity and creativity rather than authority and leadership dictating the boundaries for communities. While the de facto leaders of different communities were sometimes familiar with each other, connections between different Catholic Worker communities rarely extended beyond informal friendships. and behavior in the gospels as being nonviolent (e.g., turn the other cheek) while also disrupting the status quo (e.g., when Jesus overturned the tables of the temple money lenders). During the Vietnam War, Catholic priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan (friends of the Catholic Worker) staged draft card burnings inspired by their Catholic faith. The Worker’s support of the Berrigans and similar anti-war activists solidified its reputation as a major force of nonviolent activism, opposition to war, and Catholic peace activism during a period when many young people had become disillusioned by war and violence. Increasingly, Catholic Worker communities around the country began to attract war resisters looking for communities where their views would be supported, especially if they were Catholics, since the Catholic Church’s official teachings were much more open to war and violence in certain circumstances.

and behavior in the gospels as being nonviolent (e.g., turn the other cheek) while also disrupting the status quo (e.g., when Jesus overturned the tables of the temple money lenders). During the Vietnam War, Catholic priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan (friends of the Catholic Worker) staged draft card burnings inspired by their Catholic faith. The Worker’s support of the Berrigans and similar anti-war activists solidified its reputation as a major force of nonviolent activism, opposition to war, and Catholic peace activism during a period when many young people had become disillusioned by war and violence. Increasingly, Catholic Worker communities around the country began to attract war resisters looking for communities where their views would be supported, especially if they were Catholics, since the Catholic Church’s official teachings were much more open to war and violence in certain circumstances. appointments, while someone else makes dinner for the community, which always begins at 5 PM. Someone from Maryhouse, the other New York City house of hospitality located two blocks away, comes with a grocery cart to pick up their portion of the dinner. After everyone is finished eating, the dishes must be done, tables cleaned, and floors mopped. On Tuesday nights, these rituals are followed by a Catholic mass: a priest comes to the house each week just for the occasion. On Friday nights, they are followed by open-to-the-public “Friday night meetings” on topics varying from the spirituality of St. Teresa of Avila to the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

appointments, while someone else makes dinner for the community, which always begins at 5 PM. Someone from Maryhouse, the other New York City house of hospitality located two blocks away, comes with a grocery cart to pick up their portion of the dinner. After everyone is finished eating, the dishes must be done, tables cleaned, and floors mopped. On Tuesday nights, these rituals are followed by a Catholic mass: a priest comes to the house each week just for the occasion. On Friday nights, they are followed by open-to-the-public “Friday night meetings” on topics varying from the spirituality of St. Teresa of Avila to the prison at Guantanamo Bay. each community’s rituals differ as well. Some do not hold regular masses at their houses of hospitality. Some are not regularly involved in civil disobedience. However, most have some form of a meal shared with the homeless and other impoverished populations: if there is any ritual common to most communities, it would be this type of activity. The rituals of shared meals, shared time in jail, shared celebration of mass, and others not only enable Catholic Workers to live out their beliefs but also serve to bind them together, creating close-knit communities.

each community’s rituals differ as well. Some do not hold regular masses at their houses of hospitality. Some are not regularly involved in civil disobedience. However, most have some form of a meal shared with the homeless and other impoverished populations: if there is any ritual common to most communities, it would be this type of activity. The rituals of shared meals, shared time in jail, shared celebration of mass, and others not only enable Catholic Workers to live out their beliefs but also serve to bind them together, creating close-knit communities. people at any one time) includes regular volunteers as well as people who attend Friday Night Meetings, house masses, or other community activities. In terms of wider interest and support, the community’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, has over 20,000 subscribers around the country. The community is financed entirely through private donations from individual supporters, who might loosely be considered part of the movement due to their support of its ongoing work.

people at any one time) includes regular volunteers as well as people who attend Friday Night Meetings, house masses, or other community activities. In terms of wider interest and support, the community’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, has over 20,000 subscribers around the country. The community is financed entirely through private donations from individual supporters, who might loosely be considered part of the movement due to their support of its ongoing work. donors happy. There is a history of this refusal to compromise within the movement. As mentioned earlier, during World War II, Dorothy Day wrote in The Catholic Worker newspaper about her unwillingness to compromise her pacifist stance on the war. Her views were very unpopular, and the paper lost thousands of subscribers (and donors) as a result. Still, Day was convinced that she was right and that God would provide for the community in other ways, and the community survived that period and other rough periods in its history.

donors happy. There is a history of this refusal to compromise within the movement. As mentioned earlier, during World War II, Dorothy Day wrote in The Catholic Worker newspaper about her unwillingness to compromise her pacifist stance on the war. Her views were very unpopular, and the paper lost thousands of subscribers (and donors) as a result. Still, Day was convinced that she was right and that God would provide for the community in other ways, and the community survived that period and other rough periods in its history. Congregational Church her family was attending when she came of age, but only after informing the pastor that she did not subscribe to the doctrines of either the fall or predestination (Eddy 1892).

Congregational Church her family was attending when she came of age, but only after informing the pastor that she did not subscribe to the doctrines of either the fall or predestination (Eddy 1892). the alternative medicine treatments popular at the time, including hydropathy (water cure) and Sylvester Graham’s nutritional system. In 1862, she heard of healer Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and traveled to his practice in Maine. Quimby had studied mesmerism and developed his own system for healing, sometimes called, Mind Cure. The cure rested on the idea that since illness arose in the mind, freeing the mind of diseased thought would lead to healing.

the alternative medicine treatments popular at the time, including hydropathy (water cure) and Sylvester Graham’s nutritional system. In 1862, she heard of healer Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and traveled to his practice in Maine. Quimby had studied mesmerism and developed his own system for healing, sometimes called, Mind Cure. The cure rested on the idea that since illness arose in the mind, freeing the mind of diseased thought would lead to healing. Version of the Bible , constitutes the core of Christian Science theology and practice. Over the years, Eddy produced over four hundred editions of what she called the Christian Science textbook.

Version of the Bible , constitutes the core of Christian Science theology and practice. Over the years, Eddy produced over four hundred editions of what she called the Christian Science textbook. women pastors of the branch churches with this text and the Bible. She continued developing the church organization and produced the first edition of the Manual of the Mother Church in 1895. A comprehensive text, it contains rules determining all functions of the organization from the order of worship in services to the election of the Board of Directors. The material in the 1908 Manual (the last version) cannot be changed without the permission of Mary Baker Eddy.

women pastors of the branch churches with this text and the Bible. She continued developing the church organization and produced the first edition of the Manual of the Mother Church in 1895. A comprehensive text, it contains rules determining all functions of the organization from the order of worship in services to the election of the Board of Directors. The material in the 1908 Manual (the last version) cannot be changed without the permission of Mary Baker Eddy. not subject to sickness, sin, or death since these are not part of God’s creation and hence are not real. To realize that the creation is spiritual, not material, is to exist in the reflection of God and to be well. To be sure, people can feel ill, but this is an error of the material sense.

not subject to sickness, sin, or death since these are not part of God’s creation and hence are not real. To realize that the creation is spiritual, not material, is to exist in the reflection of God and to be well. To be sure, people can feel ill, but this is an error of the material sense. trained through a twelve session course, The Primary Class, that was designed by Mary Baker Eddy and is offered by church approved teachers. According to one of the church’s websites, Healing Unlimited, authorized practitioners are considered professionals by the church and charge for their services, which focus on the prayerful resolution of problems that include “the whole spectrum of human fears, griefs, wants, sins, and ills. Practitioners are called upon to give Christian Science treatment not only in cases of physical disease and emotional disturbance, but in family and financial difficulties, business problems, questions of employment, schooling, professional advancement, theological confusion, and so forth” (Healing Unlimited 2012). Practitioners work with individuals seeking Christian Science healing by praying with and for them and guiding them to appropriate passages in Science and Health and the Bible.

trained through a twelve session course, The Primary Class, that was designed by Mary Baker Eddy and is offered by church approved teachers. According to one of the church’s websites, Healing Unlimited, authorized practitioners are considered professionals by the church and charge for their services, which focus on the prayerful resolution of problems that include “the whole spectrum of human fears, griefs, wants, sins, and ills. Practitioners are called upon to give Christian Science treatment not only in cases of physical disease and emotional disturbance, but in family and financial difficulties, business problems, questions of employment, schooling, professional advancement, theological confusion, and so forth” (Healing Unlimited 2012). Practitioners work with individuals seeking Christian Science healing by praying with and for them and guiding them to appropriate passages in Science and Health and the Bible.  music; other music includes a performance by a paid soloist and hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal. There are no clergy in Christian Science; instead the service is led by a First and Second Reader who are elected for a three year term. The First Reader, always a female, opens the service with a brief statement and reads from Science and Health. The Second reader, a male, reads from the King James Version of the Bible. The passages are prescribed by an anonymous committee in Boston. The Bible Lesson, used in all churches, is read by the First and Second Readers. Through the Christian Science Quarterly, congregants have access to the weekly Bible and Science and Health passages along with the Bible Lesson in advance and can study them prior to attending the Sunday service.

music; other music includes a performance by a paid soloist and hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal. There are no clergy in Christian Science; instead the service is led by a First and Second Reader who are elected for a three year term. The First Reader, always a female, opens the service with a brief statement and reads from Science and Health. The Second reader, a male, reads from the King James Version of the Bible. The passages are prescribed by an anonymous committee in Boston. The Bible Lesson, used in all churches, is read by the First and Second Readers. Through the Christian Science Quarterly, congregants have access to the weekly Bible and Science and Health passages along with the Bible Lesson in advance and can study them prior to attending the Sunday service. which states that “ The Church officers shall consist of the Pastor Emeritus, a Board of Directors, a President, a Clerk, a Treasurer, and two Readers” (Eddy 1910). Mary Baker Eddy is the Pastor Emeritus; she abolished the role of pastor completely in 1894 so there are no Christian Science clergy. Baker Eddy included several committees in her institutionalization of the church. These include the Board of Education and the Board of Lectureship. The Committee on Publication was tasked by Eddy with directly addressing any misinformation appearing about Christian Science. Branch churches are administered by their local members who must abide by the Manual. No emendations to the Manual (or the by-laws) can occur without the written permission of Mary Baker Eddy.

which states that “ The Church officers shall consist of the Pastor Emeritus, a Board of Directors, a President, a Clerk, a Treasurer, and two Readers” (Eddy 1910). Mary Baker Eddy is the Pastor Emeritus; she abolished the role of pastor completely in 1894 so there are no Christian Science clergy. Baker Eddy included several committees in her institutionalization of the church. These include the Board of Education and the Board of Lectureship. The Committee on Publication was tasked by Eddy with directly addressing any misinformation appearing about Christian Science. Branch churches are administered by their local members who must abide by the Manual. No emendations to the Manual (or the by-laws) can occur without the written permission of Mary Baker Eddy. Rooms where material approved by the Board of Directors would be available to the public to read free of charge. Staffed by Christian Scientist volunteers, the Reading Rooms also distribute copies of Christian Science materials.

Rooms where material approved by the Board of Directors would be available to the public to read free of charge. Staffed by Christian Scientist volunteers, the Reading Rooms also distribute copies of Christian Science materials. featured poorly researched articles about Eddy. A scathing fourteen-installment series by Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine appeared in McClure’s Magazine between 1906 and 1908. In response to what she believed were unfair press reports, Eddy founded the Christian Science Monitor in 1908 in order to print the news fairly and thoroughly. Ironically, the Monitor has gone on to win several Pulitzer Prizes.

featured poorly researched articles about Eddy. A scathing fourteen-installment series by Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine appeared in McClure’s Magazine between 1906 and 1908. In response to what she believed were unfair press reports, Eddy founded the Christian Science Monitor in 1908 in order to print the news fairly and thoroughly. Ironically, the Monitor has gone on to win several Pulitzer Prizes. of Bliss Knapp emerged. Knapp had been a devoted follower of Eddy and had written a book in 1947, The Destiny of the Mother Church , which proclaimed Eddy to be the Second Coming of Christ (Knapp 1991). In light of the large amount of funding this would bring to the recently diminished church coffers, the Board of Directors agreed to publish the book. Many Christian Scientists took issue with this decision and several protesting groups coalesced. This was not the first time the issue of who exactly Eddy was had presented itself, and Eddy herself had prohibited what she called “deification of personality” when she felt some followers where aligning her too closely with Jesus (Eddy 1894). The protestors saw Eddy’s prohibition of “deification” as clearly precluding publication of the Knapp text. The Board excommunicated several vocal protesters, a move that was rare but not unprecedented. Several key staff resigned, and the Board found themselves in a very contentious Annual Meeting in 1993. Ultimately, the Board left the decision of whether or not to carry and/or sell the Knapp book up to the local Christian Science Reading Rooms, and published a wide range of other biographies of Eddy. By the time the Mary Baker Eddy Library and archives opened in 2002, the protests were subsiding.

of Bliss Knapp emerged. Knapp had been a devoted follower of Eddy and had written a book in 1947, The Destiny of the Mother Church , which proclaimed Eddy to be the Second Coming of Christ (Knapp 1991). In light of the large amount of funding this would bring to the recently diminished church coffers, the Board of Directors agreed to publish the book. Many Christian Scientists took issue with this decision and several protesting groups coalesced. This was not the first time the issue of who exactly Eddy was had presented itself, and Eddy herself had prohibited what she called “deification of personality” when she felt some followers where aligning her too closely with Jesus (Eddy 1894). The protestors saw Eddy’s prohibition of “deification” as clearly precluding publication of the Knapp text. The Board excommunicated several vocal protesters, a move that was rare but not unprecedented. Several key staff resigned, and the Board found themselves in a very contentious Annual Meeting in 1993. Ultimately, the Board left the decision of whether or not to carry and/or sell the Knapp book up to the local Christian Science Reading Rooms, and published a wide range of other biographies of Eddy. By the time the Mary Baker Eddy Library and archives opened in 2002, the protests were subsiding. Missouri. As a child, Zell read the Greek myths and fairy tales, which instilled in him an affinity for myth and magic. He also had paranormal experiences, such as experiencing visions from his grandfather’s life. Zell enrolled in Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri in 1961 and was married for the first time in 1963. Timothy and Martha (McCance) Zell had a son that same year. Zell went on to receive his undergraduate degree in psychology from Westminster in 1965, enrolled as a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis for a short time, and then enrolled in Life Science College in Rolling Meadows, Illinois. Two years later was awarded a Doctor of Divinity degree.

Missouri. As a child, Zell read the Greek myths and fairy tales, which instilled in him an affinity for myth and magic. He also had paranormal experiences, such as experiencing visions from his grandfather’s life. Zell enrolled in Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri in 1961 and was married for the first time in 1963. Timothy and Martha (McCance) Zell had a son that same year. Zell went on to receive his undergraduate degree in psychology from Westminster in 1965, enrolled as a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis for a short time, and then enrolled in Life Science College in Rolling Meadows, Illinois. Two years later was awarded a Doctor of Divinity degree. organizations. He separated from and divorced his first wife, and had brief relationships with other women before marrying Diana Moore (Morning Glory Ravenheart) at a public Pagan handfasting. Moore, who was born in 1948 in Long Beach, had attended Methodist and Pentecostal churches during her childhood, but broke with Christianity as a teen. She began practicing witchcraft at seventeen and changed her name to Morning Glory at twenty. She was married for a short time before meeting and soon marrying Zell in 1973. The couple sustained a lifelong, but sexually open (polyamorous), marital relationship. Among these relationships were the formation of a triad with Diane Darling, who became editor of Green Egg in 1988, and a triad with Wolf Dean Stiles, which led to the adoption of Ravenheart as a family name for all three partners.

organizations. He separated from and divorced his first wife, and had brief relationships with other women before marrying Diana Moore (Morning Glory Ravenheart) at a public Pagan handfasting. Moore, who was born in 1948 in Long Beach, had attended Methodist and Pentecostal churches during her childhood, but broke with Christianity as a teen. She began practicing witchcraft at seventeen and changed her name to Morning Glory at twenty. She was married for a short time before meeting and soon marrying Zell in 1973. The couple sustained a lifelong, but sexually open (polyamorous), marital relationship. Among these relationships were the formation of a triad with Diane Darling, who became editor of Green Egg in 1988, and a triad with Wolf Dean Stiles, which led to the adoption of Ravenheart as a family name for all three partners. Ecosophical Research Association, Universal Federation of Pagans, Grey School of Wizardry). The Ecosophical Research Association offered a source of income for a time as the Zells produced unicorns by breeding and surgically altering white goats, four of which were sold to Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1984. The following year the organization, which aims to “explore the territory of the archetype, the basis of legends and the boundaries between the sacred and the secular” and specializes in crypozoology, undertook a search for mermaids in the South Seas (Adler 1975:317). The Grey School of Wizardry, founded in 2004, is a magickal education system that is organized online.

Ecosophical Research Association, Universal Federation of Pagans, Grey School of Wizardry). The Ecosophical Research Association offered a source of income for a time as the Zells produced unicorns by breeding and surgically altering white goats, four of which were sold to Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1984. The following year the organization, which aims to “explore the territory of the archetype, the basis of legends and the boundaries between the sacred and the secular” and specializes in crypozoology, undertook a search for mermaids in the South Seas (Adler 1975:317). The Grey School of Wizardry, founded in 2004, is a magickal education system that is organized online.

of the Goddess,” which was later developed into “The Gaea Thesis.” It posits that “the entire Biosphere of the Earth comprises a single living organism” and is composed of all living life-forms (Cusack 2010:65; Adler 1975:298). Zell (2010) traces the evolution of the Biosphere of the Earth back to a single living cell:

of the Goddess,” which was later developed into “The Gaea Thesis.” It posits that “the entire Biosphere of the Earth comprises a single living organism” and is composed of all living life-forms (Cusack 2010:65; Adler 1975:298). Zell (2010) traces the evolution of the Biosphere of the Earth back to a single living cell: credited with inventing the concept of polyamory in “A Bouquet of Lovers.” As she describes polyamorous relationships, “The goal of a responsible Open Relationship is to cultivate ongoing, long-term, complex relationships which are rooted in deep mutual friendships.” Polyamory is thus one of the expressions of human interconnectedness and protests against divisive exclusivity. Open relationships are sustained by honesty, transparency, mutual agreement. A further provision is that unprotected sexual relationships may by practiced only within the group, which is the “Condom Compact” (Morning Glory Zell n.d.).