Ramtha School of Enlightenment

Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment

Founder: JZ Knight

Date of Birth: 1946

Birth Place: New Mexico , USA

Year Founded: 1988

Sacred or Revered Texts: The White Book

Size of Group: As of October, 2000, JZ Knight has around 3000 devotees. 1

History

JZ Knight, founder of Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, was born in Roswell, New Mexico where she experienced psychic and paranormal phenomenon from an early age. An elderly Yacqui Indian woman held JZ in her arms when she was a mere infant and declared that she was destined to “see what no one else sees.” Then, when JZ was older, she and some friends saw “blinding red flashes of light” while at a sleepover. The light abruptly stopped, and the girls apparently forgot the bizarre incident. Years later, JZ recalled the strange flashing lights. She was intrigued by their cause and why she had forgotten about them. JZ believed UFO’s or some higher power may have been responsible, beginning her interest in the paranormal. 2

Despite a turbulent childhood caused by an alcoholic father, she graduated high school and went on to a small business college. Financial difficulties forced her to quit school, but she managed to get a decent job with a cable company. In 1973, she started her own communications company. Her coworkers quickly found that JZ had an uncanny ability to determine when (and to whom) to sell. In fact, some of them believed she could predict the future. 3

Whatever psychic influence JZ had might have been inherited from her mother, who claimed she could foresee the future in her dreams. JZ’s mother knew about a family member’s death or even whether JZ made the school majorette team before the event occurred. 4

JZ’s psychic experiences continued, helping her to realize that she was indeed special. One psychic saw a great force within JZ, a force nearly as powerful as Jesus Christ. This force would help bring peace to the world. Later, an event occurred that can only be described as a miracle. A friend had forced JZ to see an evangelical healer due to her faltering health. JZ, who had become disillusioned with the hypocritical church long ago, openly denounced the minister’s healing powers. In that instant, a flash of blue light knocked the minister down. The congregation was stunned. JZ was cured of her ills. She believed she had seen the hand of God. 5

One of the most important events in her life occurred when she accompanied her friend to a psychic reading one afternoon. The psychic took a strong interest in JZ. She predicted that JZ would move to a place with “great mountains” and “tall pines.” This was where she would meet The One. This entity, the psychic foresaw, would give JZ “great influence” and destiny. Sure enough, JZ received a job offer in the mountain country of Tacoma, Washington. She took the job with the psychic’s powerful words echoing in the back of her mind. 6

The next few years were uneventful in terms of paranormal phenomenon, but JZ and her second husband Jeremy dabbled in psychic communication and mysticism. Jeremy , in particular, became interested in the properties of pyramids, which were believed to harness psychic energy. One day in February, 1977, while JZ and Jeremy were playing with some pyramids in their home, The One appeared before her. 7

Standing in her kitchen a mere ten feet from JZ was an enormous figure, dressed in flowing robes and surrounded by purple light. He proclaimed, “I am Ramtha, the Enlightened One. I have come to help you over the ditch.” He went on to say to a bewildered JZ: “It is the ditch of limitation and fear I will help you over. For you will, indeed, beloved woman become a light unto the world.” Ramtha then warned JZ that she was in danger and she must leave the house immediately, at which point he disappeared. JZ heeded this warning, moving her family into a new home. Days later, the house was ransacked by thugs. The trusting relationship between JZ and Ramtha was thus cemented. 8

The Beginning of RSE

With the help of experts in the field of psychic communication and channeling, JZ was able to turn her body over to Ramtha so that he could spread his teachings. Ramtha first spoke to the public in 1978, when he made an impact with his vast knowledge and insight. The local media soon picked up on this story helping Ramtha’s (and JZ’s) popularity to spread. The fact that Ramtha emerged in the heart of the New Age movement considerably helped his cause; people were lining up to hear him speak. JZ became a full time channel and began charging money for admittance (an idea brought to her by Ramtha himself). Even Actresses Shirley McLean and Joan Hackett became disciples of Ramtha (The Enlightened One predicted McLean would win the “highest award” for her role in Terms of Endearment). Knight’s popularity among the stars lead to her appearance on the Merv Griffin Show in 1985. 9

The RSE Today

JZ’s school has earned her millions of dollars and lots of adoration. She is among the leading New Age channelers with 3000 followers. Disciples come to her ranch in Yelm, Washington to learn the Great Work (see Beliefs and Practices). Ramtha offers courses for beginners and advanced students which are designed to let the disciples harness their divine powers. Aside from lectures by Ramtha, the students participate in “field work” which is designed to focus their concentration and energy (C&E). Field work usually involves searching a vast field for index cards while blindfolded. JZ also built a massive maze known as the Tank in her ranch which she uses for various lessons. Although the lessons seem strange to the students and outsiders, each one has a specific purpose that progresses them on the path to enlightenment. 10

Ramtha’s School tends to attract an older audience than most New Age Movements. The average age for a beginning student is mid-thirties, with some starting as young as age 6, however. According to a study of the advanced students, the typical students “are in midlife, have high levels of education and occupational prestige, and are now choosing to orient themselves in a new direction.” 11

The RSE has become more commercial in the late 1990’s. Students must purchase and watch an introductory video before attending classes. The sale of Ramtha books, video’s, and audio cassettes has become a profitable business. 12

JZ’s success, however, is not without a price. Critics claim that JZ is a fraud, and that she uses mind control techniques. Lawsuits have hurt her in recent years, including a case brought by her ex-husband who says she used Ramtha’s influence to coerce him out of a fair divorce settlement (see controversies).

Beliefs

Ramtha’s teachings are encompassed in a work known as the White Book, and these ideas are based on ancient Gnosticism of the Mediterranean. The core principles of Ramtha’s School are 1) a supreme deity is a part of every man, and 2) the key to reaching the God within us is through Gnosis or knowledge. 13 Ramtha himself does not wished to be revered as a God, but rather as an equal. He says in one of his channeling sessions, “I am but a teacher, servant, brother unto you.” 14

Who Is Ramtha?

Ramtha is a 35,000 year old warrior from the ancient city of Lemuria. The Lemurians were oppressed by highly advanced citizens of Atlantis because they believed the Lemurians were “soulless.” At age 14, Ramtha led a small army against the Atlantians and defeated them. More people joined his army, and he soon became a great warrior. He was stabbed severely during one battle, but miraculously he did not die. His enemies began to believe he was immortal. Ramtha “learned the mysteries of the unknown god and became enlightened” during the seven years he was recovering from his wound. He rose through higher levels of consciousness and eventually transformed into a being of light. He ascended as a God, but vowed to return. 15

Indeed, 35,000 years later, Ramtha returned to meet JZ Knight. Ramtha chose to channel through JZ rather than present himself in human form for several reasons. First, he did not want to be worshipped as a deity, but rather an equal. He felt that if he presented himself, he would be idolized by his students. Second, his human form limited him to a male entity. Channeling himself through a woman presented the dual male/female nature of God. Third, for reasons of his own, he believed JZ Knight was especially suited to the task at hand. 16

Ramtha’s Worldview

Ramtha’s goal with beginner students is to break them away from the traditional Western worldview. This worldview limits the individual and suppresses his power as a divine being. Ramtha aims to make the student not only believe in his divine power, but to manifest it. 17 Ramtha’s Creation myth and the philosophies stemming from it are complex and abstract, but they are essential to understanding his teachings.

The universe started as a Void of nothingness. This Void “turned in upon itself” creating consciousness and energy. Consciousness and Energy fused together causing the Void to become aware of itself. This awareness was represented in the Void as single- dimensional entity called Point Zero. Other dots of awareness formed, and the high energy reactions between the various dots created time and space. As these dot entities interacted, seven energy levels developed. The entities of awareness left Point Zero to “explore” other levels of the Void in order to “make known the unknown.” As the entities progressed from Point Zero (the highest level) to level 1, energy and time slowed. At the lower levels, the entities took on form and substance. When the entities reached the first level, they “coagulated” into human form. It was at this level that life as we know it began. 18

This theory of Creation is difficult to grasp. The main point, however, is that consciousness exists on multiple levels, with human form being the lowest. The higher the level, the greater the level of consciousness. The entities (Gods) used consciousness to create objects at their whim. In other words, they manifested their dreams to create all the objects in the world. The Gods came down to the lowest levels to experience life in its material form, but they still had their divine powers. The early humans could easily move between levels and manifest their dreams or desires. Over time, however, this ability was lost. Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment allows students to regain these powers, and carry on the task of Gods: to make known the unknown. 19

Humans often move to other consciousness levels without realizing it. The most common occurrence is moving up to the second level while dreaming. Near-death experiences, psychic visions and other phenomenon can be attributed to moving to another plane of consciousness. 20

When humans lost the power of the Gods, they fell into the “ditch of limitation,” the same ditch that Ramtha mentioned during his first encounter with JZ. Ramtha holds the Church partly responsible for this limitation when it “took God outside of Man, [and] put him far, far away.” The Church “unenlightened” man by claiming that God is far superior to humans. Ramtha’s teachings indicate that the Church “created” God to keep men in line. He even goes so far as to say Hell and the devil were “created through religious dogma for the purpose of intimidating the masses into a controllable organization.” 21

The Great Work

The Great Work of Ramtha’s teaching is literally manifesting dreams and desires. In essence, the Great Work requires reaching maximum potential of the mind. The key to manifestations lies in the cerebrum, which, according to Ramtha, has the power to make dreams a reality. In the past, humans would hold a dream or desire in their mind, and it would manifest. Today, humans play a passive role to manifestations. They absorb the world around them in their mind, and this then becomes reality. In a sense, they are trapped in the present reality. Ramtha desires to teach students the power to manifest any desire and make known the unknown. 22

Issues and Challenges

Any new religion has its share of controversy, and the RSE is no exception. The public generally perceives New Age Religions, groups in a negative light, usually without any evidence. Ramtha’s messages are certainly not mainstream, and the way in which JZ presents them is also subject to controversy. Some critics claim JZ is a fraud whose only goal is to make money. Others say that she uses brainwashing techniques to keep her students from leaving. There are a number of opinions on the matter and no clear answers.

Is JZ a Channeler?

JZ has undergone a lot of scrutiny as one of the most prominent American channelers. Her overall performance as Ramtha is seamless. While she is channeling, her posture, walk, voice and the color of her eyes changes. Actress Linda Evans, a student of Ramtha’s, argued that if JZ is a fraud then “she is the greatest actress in the world.” 23 A skeptical psychologist became uncertain of JZ’s legitimacy when JZ put her hand on his head revealing such power that he “could hardly take it.” 24 Even if Ramtha was not real, he said, there was definitely a power within her that science could not explain. Later, a team of scientists did tests on JZ during channeling episodes over the course of a year. The results of the test categorically ruled out fraud or multiple personality disorders. 25 “We know something’s going on here,” said one of the researchers, “we just can’t say, at this point, specifically what it is.” 26 Her students swear that JZ and Ramtha have entirely different personas leading them to believe that Ramtha is indeed channeling through JZ.

Other evidence points to the contrary. One of JZ’s business managers saw her “practicing” the Ramtha personality. Her husband Jeff Knight also noticed her slip in and out of the trance to take cigarette breaks (JZ, unlike Ramtha, was a smoker). 27 And then there is the common sense argument, according to the Skeptics Dictionary Website: “…it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that the likelihood of a 35,000 year old Cro-Magnon ghost suddenly appearing in a Tacoma kitchen to a homemaker to reveal profundities about centers and voids, self-love and guilt-free living, or love and peace, is close to zero.” 28 It takes a great leap of faith to believe that JZ is a channeler, although scientific evidence may not be enough to discredit Ramtha.

Criticism of the RSE

Publicity surrounding Ramtha’s School has been negative for the most part in recent years. A 20/20 segment portrayed JZ as a fraud who was exploiting peoples’ beliefs in Ramtha for money. The show also claimed that Ramtha was teaching people that they are above morality due to their divine status. These beliefs, they surmised, could only lead to amoral behavior. The 20/20 exposure led to more attacks from the press on JZ and the School. 29

J. Gordon Melton, a leading scholar on new religious movements, thoroughly investigated the RSE and found that these criticisms were unfounded. Melton attributes most of the bad press to sensationalist journalism that critiques unconventional beliefs for a good story. Furthermore, anti-cult and counter-cult sentiments are popular with Americans, which intensifies the controversy. 30 . Melton’s book gave important facts rather than insinuations and smear campaigns

Anti-cultists respond that Melton’s book is biased because (1) Melton was hired to testify for JZ in a court case against her in 1992, (2) JZ provided funding for the book and (3) Melton established close ties with JZ and the school during the research thus damaging his credibility as an objective researcher. Melton also neglected to mention several incidents where people were injured during blindfolded field activities. 31 Although this omission does not make JZ a dangerous cult leader, it makes one wonder what else Melton left out of his book.

Criticism from the public caused JZ to withdraw from the public in the early 1990’s. During this period she devoted her time to her school and to Ramtha. Under Ramtha’s guidance, she reappeared to the public in the late 1990’s. As Ramtha’s school continues to succeed, it is receiving “signs of a certain legitimacy among the religious community.” 32 Today, JZ has an unprecedented number of students, and her books and tapes are selling well.

Scandals

Several scandals have marred JZ’s reputation among the religious community. The first involves a student of Ramtha’s who was hired to run stress management programs for the Federal Aviation Administration in 1984. This student, Gregory May, a psychologist from California, used techniques that were “far beyond routine.” Some of the training activities involved tying employees together for long periods of time, forcing women to shower together, sleep deprivation and verbal abuse. Several employees brought charges against the FAA for trauma occasioned by May. 33 These unorthodox techniques cannot be directly linked to Ramtha’s teachings. Nevertheless, the media was quick to point out the connection between bizarre training techniques and (what they perceived to be) a destructive cult.

Another scandal occurred because of JZ’s fondness for horses. Overstepping her boundaries as a religious leader, she advised some of her students to invest in Arabian horses. These students followed her advice as if advised by Ramtha himself. Many of them lost money in this venture and bitterly left the school. Later, JZ compensated them for their losses, but the damage had been done. She had given the critics ammunition to use against her. 34

In addition to these scandals, JZ had a turbulent personal life. She was married five times, and at least once she was caught in an affair with a young student. She divorced her fifth husband, Jeffrey Knight, in 1989. Jeffrey claimed that JZ used Ramtha’s influence to coerce him out of a fair divorce settlement. He took the case to court, embroiling JZ in an intense legal battle. 35 Meanwhile, JZ faced serious financial burdens from bill collectors and taxes. She kept these problems from the public, but eventually the media picked up on them.

Conclusion

Although Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment is surrounded by controversy, there is no clear evidence that JZ is a fraud or that the school is a danger to anyone. Sociologists and psychologists do not believe that students are “brainwashed” to follow this movement, nor are they held against their will. Ramtha’s students are searching for answers to life’s most important questions, and the School is helping them resolve these issues. Until undisputable evidence arises that JZ is harming people, the media and anti-cultists should be careful with their criticisms.

Bibliography

Brown, Michael. “The Channeling Zone.” Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. 1977.

Carrol, Robert Todd. “Ramtha aka J.Z. Knight.” The Skeptics Dictionary. http://skepdic.com/channel.html

Diamond, Steve. “Into the Mystic: Ramtha Meets the Scholars.” The New Times. Accessed at http://www.newtimes.org/issue/9705/97-05-jz.html

McDonald, Sally. “J.Z. Knight Channeling New Support.” Seattle Times May 9, 1998. Accessed at http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com

McDonald, Sally. “Christianity vs. New Age.” Seattle Times May 9, 1998. Accessed at http://archives.seattletimes.nwsource.com

Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. Hillsboro, OR: Beyond Words Publishing, Inc. 1998.

Neill, Michael. “Sure, blame the caveman: channeler J.Z. Knight’s troubles put 35,000 year old Ramtha on trial”. People Weekly Oct. 12, 1992 p. 123.

“Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment – The American Gnostic School.” http://www.ramtha.com

“The Guru and the FAA.” Newsweek , March 6 1995 p. 32.

References

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom: FAQ’s.” http://www.ramtha.com/html/aboutus/faqs/students/how-many.stm

- Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. p. 3-4

- Ibid. 9

- Ibid. 4

- Ibid. 9-12

- Ibid. 7-9

- Ibid. 14-15

- Ibid. 14-15

- Ibid. 46-52

- Ibid. 108-109

- Ibid. 126-127

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom:RSE Store.” http://ramtha.com/html/rse-store/product-details/v1.42.stm

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom:About US.” http://ramtha.com/html/aboutus/faqs/school/gnostic-beliefs.stm

- Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. p. 58

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom:About US.” http://ramtha.com/html/aboutus/faqs/teacher/who.stm

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom:About US.” http://ramtha.com/html/aboutus/faqs/teacher/why-jz.stm

- Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. p. 58

- Ibid. 78-80.

- Ibid. 81-84

- Ibid. 85

- Ibid. 59- 61.

- Ibid. 85

- Ibid. 146

- Brown, Michael. The Channeling Zone. p. 12

- “Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment, The School of Ancient Wisdom:About US.” http://ramtha.com/html/aboutus/faqs/jz/proof.stm

- Diamond, Steve. “Into the Mystic: Ramtha Meets the Scholars.” http://www.newtimes.org/issue/9705/97-05-jz.html

- Szimhart, Joe. “Book Review/Essay on Melton’s Study.” http://www.kelebekler.com/cesnur/txt/ram2.htm

- Carrol, Robert Todd. “Ramtha aka J.Z. Knight.”

- Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. 137-139

- Ibid. 144-145

- Szimhart, Joe. “Book Review/Essay on Melton’s Study.” http://www.kelebekler.com/cesnur/txt/ram2.htm

- McDonald, Sally. “J.Z. Knight Channeling New Support.”

- “The Guru and the FAA.” Newsweek March6, 1995.

- Melton, J. Gordon. Finding Enlightenment. p. 147-148

- “Sure, blame the caveman.” People Weekly October 12, 1992

Created by Joseph M. Khattab

For Soc 257: New Religious Movements

Fall term, 2000

University of Virginia

Last modified: 07/23/01

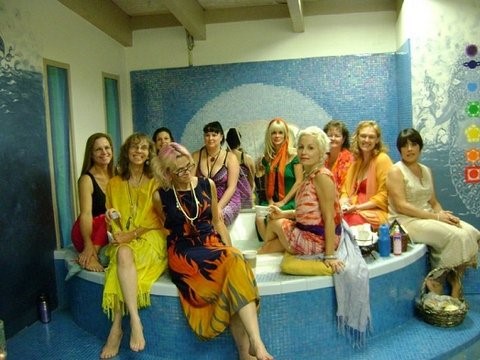

cover story describing the Phoenix Goddess Temple as “nothing more than a New Age brothel” (Stern 2016), A police investigation of the Temple was then launched that led to the arrest of Elise [Image at right] and other Temple staff members and a shutdown of the temple in September 2011

cover story describing the Phoenix Goddess Temple as “nothing more than a New Age brothel” (Stern 2016), A police investigation of the Temple was then launched that led to the arrest of Elise [Image at right] and other Temple staff members and a shutdown of the temple in September 2011 levels and involve instruction from or interaction with a practitioner. Female practitioners are referred to as “goddesses” [Image at right] and generally assume goddess identities such as Shakti, Isis and Aphrodite. Male practitioners are commonly called “touch healers.” According to the Temple website, the church healers “seek to help women, men and couples discover their own divine connection between soul, light body and sacred vessel” and “offer group classes and one-on-one teachings and training, play shops and internships,” all meant to “make use of the gifts of the Goddess” and allow seekers to, among other things, “feel the light of your own soul” and “feel the chakra wheels spinning your self into physical existence.”

levels and involve instruction from or interaction with a practitioner. Female practitioners are referred to as “goddesses” [Image at right] and generally assume goddess identities such as Shakti, Isis and Aphrodite. Male practitioners are commonly called “touch healers.” According to the Temple website, the church healers “seek to help women, men and couples discover their own divine connection between soul, light body and sacred vessel” and “offer group classes and one-on-one teachings and training, play shops and internships,” all meant to “make use of the gifts of the Goddess” and allow seekers to, among other things, “feel the light of your own soul” and “feel the chakra wheels spinning your self into physical existence.” sessions and classes, and organizes events. [Image at right] Temple participants include guests (who seek information about the Temples activities), seekers (“who have a spiritual practice or have had in the past, and are now feeling led to find new sources of energy, direction and connection to the Higher Power”), initiates (“who have found genuine soul-food in our temple”), brothers and sisters (“who have decided to really support the Goddess Temples”), priests and priestesses (“who have a gift for channeling light into matter”), and healers and guides (who have “gifts to give as well as receive”) (Phoenix Goddess Temple n.d. “In Temple”).

sessions and classes, and organizes events. [Image at right] Temple participants include guests (who seek information about the Temples activities), seekers (“who have a spiritual practice or have had in the past, and are now feeling led to find new sources of energy, direction and connection to the Higher Power”), initiates (“who have found genuine soul-food in our temple”), brothers and sisters (“who have decided to really support the Goddess Temples”), priests and priestesses (“who have a gift for channeling light into matter”), and healers and guides (who have “gifts to give as well as receive”) (Phoenix Goddess Temple n.d. “In Temple”). her final argument to the jury, she set up a small alter on the defense table”with pine cones and goddess figurines, then told the court that she was “letting the holy spirit guide me today through this trial” (Brinkman 2016). (Image at right) Finally, she sang the Star Spangled Banner just prior to being sentenced (Walsh 2016).

her final argument to the jury, she set up a small alter on the defense table”with pine cones and goddess figurines, then told the court that she was “letting the holy spirit guide me today through this trial” (Brinkman 2016). (Image at right) Finally, she sang the Star Spangled Banner just prior to being sentenced (Walsh 2016).

reported Mary’s request for the distribution of not only “Mary’s Message,” but also several other books published by the Shepherds of Christ Ministries, including God’s Blue Book and Rosaries from the Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Further, many of the messages conveyed God’s wrath with human sinfulness and the failure to listen to previous messages, threatening humanity with fire, even citing religious negligence and divine wrath as the source of contemporary wildfires across Florida. There have also been prophecies of an imminent Endtime. All of Ring’s messages have been discerned by Father Carter.

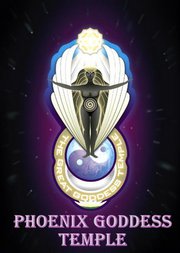

reported Mary’s request for the distribution of not only “Mary’s Message,” but also several other books published by the Shepherds of Christ Ministries, including God’s Blue Book and Rosaries from the Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Further, many of the messages conveyed God’s wrath with human sinfulness and the failure to listen to previous messages, threatening humanity with fire, even citing religious negligence and divine wrath as the source of contemporary wildfires across Florida. There have also been prophecies of an imminent Endtime. All of Ring’s messages have been discerned by Father Carter. leave offerings to the Virgin, such as “candles, flowers, fruit, [and] beads, and participate in individual acts of piety (Posner 1997:2). Mary’s requests for pilgrims, as reported by Ring, include prayer, a daily recitation of the Ten Commandments at the site, recitation of the rosary, and an observance of the First Saturday devotion. In order to fulfill the Virgin’s requests to distribute her messages and lead others into prayer, audiotapes of “Mary’s Message” are played and rosaries, pamphlets, and brochures are provided by site staff (Swatos 2002:192). The focus on individual worship, rather than “the communal sense of the Mass,” is one of the primary factors setting the Clearwater group’s organization apart from traditional Catholic configuration (Swatos 2002).

leave offerings to the Virgin, such as “candles, flowers, fruit, [and] beads, and participate in individual acts of piety (Posner 1997:2). Mary’s requests for pilgrims, as reported by Ring, include prayer, a daily recitation of the Ten Commandments at the site, recitation of the rosary, and an observance of the First Saturday devotion. In order to fulfill the Virgin’s requests to distribute her messages and lead others into prayer, audiotapes of “Mary’s Message” are played and rosaries, pamphlets, and brochures are provided by site staff (Swatos 2002:192). The focus on individual worship, rather than “the communal sense of the Mass,” is one of the primary factors setting the Clearwater group’s organization apart from traditional Catholic configuration (Swatos 2002). the Shepherds of Christ Ministry. She reportedly began receiving “private revelations” from Jesus and Mary in 1991, several years prior to reporting messages associated with the image at Our Lady of Clearwater. More is known about Father Edward Carter. He was brought up I Cincinnati, attended Xavier University, was ordained in the Jesuit Order when he was 33 years-old, and taught theology at Xavier University for nearly three decades. Carter reports having begun receiving messages from Jesus during the summer, 1993, and on the day before Easter in 1994 was told that he would now begin to receive messages for others (Carter 2010). He founded the Shepherds of Christ Ministry in 1994 after the Batavia Vissionary was instructed to include him with the other priests who were to receive messages through her and to carry out the special mission of establishing the Shepherds of Christ. Carter also received a message from Jesus in which he was told to undertake this mission and to include Rita Ring: ” I am requesting that a new prayer movement be started under the direction of Shepherds of Christ Ministries…. I will use this new prayer movement within My Shepherds of Christ Ministries in a powerful way to help in the renewal of My Church and the world. I will give great graces to those who join this movement…. I am inviting My beloved Rita Ring to be coordinator for this activity” (“About” 2006).

the Shepherds of Christ Ministry. She reportedly began receiving “private revelations” from Jesus and Mary in 1991, several years prior to reporting messages associated with the image at Our Lady of Clearwater. More is known about Father Edward Carter. He was brought up I Cincinnati, attended Xavier University, was ordained in the Jesuit Order when he was 33 years-old, and taught theology at Xavier University for nearly three decades. Carter reports having begun receiving messages from Jesus during the summer, 1993, and on the day before Easter in 1994 was told that he would now begin to receive messages for others (Carter 2010). He founded the Shepherds of Christ Ministry in 1994 after the Batavia Vissionary was instructed to include him with the other priests who were to receive messages through her and to carry out the special mission of establishing the Shepherds of Christ. Carter also received a message from Jesus in which he was told to undertake this mission and to include Rita Ring: ” I am requesting that a new prayer movement be started under the direction of Shepherds of Christ Ministries…. I will use this new prayer movement within My Shepherds of Christ Ministries in a powerful way to help in the renewal of My Church and the world. I will give great graces to those who join this movement…. I am inviting My beloved Rita Ring to be coordinator for this activity” (“About” 2006). validated (“discerned) her messages. For a time she received messages daily that were made available in the Message Room along with video tapes. Ring visited what became the ” Mary Image Building” on the fifth of each month. Beginning in 2000, the year of Jubilee, the image has appeared to turn completely gold on that day.

validated (“discerned) her messages. For a time she received messages daily that were made available in the Message Room along with video tapes. Ring visited what became the ” Mary Image Building” on the fifth of each month. Beginning in 2000, the year of Jubilee, the image has appeared to turn completely gold on that day.

of Christ Ministries presents itself as a lay Catholic organization but has no formal relationship to the church. Site representatives have taken care not to challenge Roman Catholic Church authority. For example, the group indicated that it would seek permission from the local diocese before constructing a chapel at the site. Father Carter has repeatedly stated that “I recognize and accept that the final authority regarding private revelations rests with the Holy See of Rome, to whose judgment I willingly submit” (“News” n.d.). The Catholic diocese of St. Petersburg has disavowed any connection to Shepherds of Christ and has called the image a “naturally explained phenomenon.” However, the diocese has not launched an investigation of the site and has not condemned it (“Clearwater Madonna Changes Hands” 1998; Tisch 2004:4). There have other criticisms from within the Catholic community that conclude the apparitions are not authentic (Conte 2006).

of Christ Ministries presents itself as a lay Catholic organization but has no formal relationship to the church. Site representatives have taken care not to challenge Roman Catholic Church authority. For example, the group indicated that it would seek permission from the local diocese before constructing a chapel at the site. Father Carter has repeatedly stated that “I recognize and accept that the final authority regarding private revelations rests with the Holy See of Rome, to whose judgment I willingly submit” (“News” n.d.). The Catholic diocese of St. Petersburg has disavowed any connection to Shepherds of Christ and has called the image a “naturally explained phenomenon.” However, the diocese has not launched an investigation of the site and has not condemned it (“Clearwater Madonna Changes Hands” 1998; Tisch 2004:4). There have other criticisms from within the Catholic community that conclude the apparitions are not authentic (Conte 2006). St. Maria Goretti Catholic Church. There, several young people as well as Father Jack Spaulding reported apparitions or locutions of Jesus and of Our Lady, appearing as Our Lady of Joy. These messages from Jesus have been published in six volumes of I Am Your Jesus of Mercy. In 1989, the diocese of Phoenix investigated the Scottsdale apparitions and took a neutral position on the matter.

St. Maria Goretti Catholic Church. There, several young people as well as Father Jack Spaulding reported apparitions or locutions of Jesus and of Our Lady, appearing as Our Lady of Joy. These messages from Jesus have been published in six volumes of I Am Your Jesus of Mercy. In 1989, the diocese of Phoenix investigated the Scottsdale apparitions and took a neutral position on the matter. Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Now run by Mt. St. Mary’s University, the site centers upon a replica of the 1858 apparition site in Lourdes, France, and also features a Glass Chapel and visitor’s center. A walkway winds through Stations of the Cross and a Rosary Walk, ending at the foot of a large metal Crucifix atop a wooded hill. This is where Gianna received her first apparition in Emmitsburg. Our Lady, clothed in a blue dress and white veil, invited Gianna and Michael to move to the small town, if they were willing. They were given three days to make the decision, and returned home to Arizona to consider the invitation.

Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Now run by Mt. St. Mary’s University, the site centers upon a replica of the 1858 apparition site in Lourdes, France, and also features a Glass Chapel and visitor’s center. A walkway winds through Stations of the Cross and a Rosary Walk, ending at the foot of a large metal Crucifix atop a wooded hill. This is where Gianna received her first apparition in Emmitsburg. Our Lady, clothed in a blue dress and white veil, invited Gianna and Michael to move to the small town, if they were willing. They were given three days to make the decision, and returned home to Arizona to consider the invitation. Group at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Emmitsburg. Gianna received a vision at her first prayer meeting, surprising fellow devotees when she fell to her knees and began conversing with Our Lady. Father Alfred Pehrsson, C.M., the parish pastor she had met during her January visit to Emmitsburg, explained to parishioners what had happened and implored them to keep quiet about what they had seen so as not to call undue attention to Gianna or the prayer group. Nevertheless, attendance at the Thursday Marian Prayer Group grew as news of the visionary spread. As many as 1,000 visitors attended weekly (Gaul 2002), including several priests, bishops from other countries, and even non-Catholic visitors. Close to 700,000 people attended between 1994 and 2008 (G. Sullivan 2008). Church groups throughout the region organized bus trips to Emmitsburg, and many families drove several hours to spend the day visiting the town. The numbers of conversions and confessions increased, and Fr. Pehrsson even heard confessions from Jewish and Protestant attendees (Pehrsson n.d.). Many attendees reported miracles during the service: a spinning sun or two suns, healings, and once, the lights of heaven visible in Gianna’s eyes during ecstasy. Every week, several rows of pews were reserved at the church for parishioners, but others had to arrive before noon (for the 7 PM service) in order to find a seat. Overflow crowds were directed to the church rectory across the street, where a television screen was set up so that all could see Gianna. Problematically, crowds set up blankets and chairs on the lawn and cemetery surrounding the church, and parked illegally throughout the small town. In response, some Protestant churches in the area opened their parking lots to pilgrims.

Group at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Emmitsburg. Gianna received a vision at her first prayer meeting, surprising fellow devotees when she fell to her knees and began conversing with Our Lady. Father Alfred Pehrsson, C.M., the parish pastor she had met during her January visit to Emmitsburg, explained to parishioners what had happened and implored them to keep quiet about what they had seen so as not to call undue attention to Gianna or the prayer group. Nevertheless, attendance at the Thursday Marian Prayer Group grew as news of the visionary spread. As many as 1,000 visitors attended weekly (Gaul 2002), including several priests, bishops from other countries, and even non-Catholic visitors. Close to 700,000 people attended between 1994 and 2008 (G. Sullivan 2008). Church groups throughout the region organized bus trips to Emmitsburg, and many families drove several hours to spend the day visiting the town. The numbers of conversions and confessions increased, and Fr. Pehrsson even heard confessions from Jewish and Protestant attendees (Pehrsson n.d.). Many attendees reported miracles during the service: a spinning sun or two suns, healings, and once, the lights of heaven visible in Gianna’s eyes during ecstasy. Every week, several rows of pews were reserved at the church for parishioners, but others had to arrive before noon (for the 7 PM service) in order to find a seat. Overflow crowds were directed to the church rectory across the street, where a television screen was set up so that all could see Gianna. Problematically, crowds set up blankets and chairs on the lawn and cemetery surrounding the church, and parked illegally throughout the small town. In response, some Protestant churches in the area opened their parking lots to pilgrims. Commission was unfair to Gianna, spending very little time with her and prohibiting her supporters (including theologians) from speaking on her behalf. Gianna was permitted to answer only the questions posed to her by the Commission, rather than tell her whole story.

Commission was unfair to Gianna, spending very little time with her and prohibiting her supporters (including theologians) from speaking on her behalf. Gianna was permitted to answer only the questions posed to her by the Commission, rather than tell her whole story. Cult Watch , took a negative view of the apparitions, supporters, and visionary. Father Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., Gianna’s spiritual advisor, was silenced when Cardinal Keeler ordered Fr. Kavanaugh’s superior to temporarily restrict the priest from attending the monthly prayer meetings. Father Alfred Pehrsson, the parish priest at St. Joseph who had since been relocated to another parish, was also asked by his superiors not to speak about the Emmitsburg apparitions. Both men have remained reticent to speak about the Emmitsburg events.

Cult Watch , took a negative view of the apparitions, supporters, and visionary. Father Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., Gianna’s spiritual advisor, was silenced when Cardinal Keeler ordered Fr. Kavanaugh’s superior to temporarily restrict the priest from attending the monthly prayer meetings. Father Alfred Pehrsson, the parish priest at St. Joseph who had since been relocated to another parish, was also asked by his superiors not to speak about the Emmitsburg apparitions. Both men have remained reticent to speak about the Emmitsburg events. leadership, Gianna wrote a letter to Archbishop O’Brien informing him of the history of the apparitions in Emmitsburg and assuring him that she would comply with his wishes regarding the monthly prayer meetings held at Lynfield. Archbishop O’Brien did not respond to Gianna’s letter directly, but instead released a Pastoral Advisory in 2008 repeating the Church’s position that the messages were not supernatural. While he admitted in the Pastoral Advisory that there is nothing necessarily sacrilegious about the messages, he asserted his view that the “alleged apparitions are not supernatural in origin” (O’Brien 2008). He further “strongly” cautioned Mrs. Gianna Talone-Sullivan not to communicate in any manner whatsoever, written or spoken, electronic or printed, personally or through another in any church, public oratory, chapel or any other place or locale, public or private, within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Baltimore any information of any type related to or containing messages or locutions allegedly received from the Virgin Mother of God.

leadership, Gianna wrote a letter to Archbishop O’Brien informing him of the history of the apparitions in Emmitsburg and assuring him that she would comply with his wishes regarding the monthly prayer meetings held at Lynfield. Archbishop O’Brien did not respond to Gianna’s letter directly, but instead released a Pastoral Advisory in 2008 repeating the Church’s position that the messages were not supernatural. While he admitted in the Pastoral Advisory that there is nothing necessarily sacrilegious about the messages, he asserted his view that the “alleged apparitions are not supernatural in origin” (O’Brien 2008). He further “strongly” cautioned Mrs. Gianna Talone-Sullivan not to communicate in any manner whatsoever, written or spoken, electronic or printed, personally or through another in any church, public oratory, chapel or any other place or locale, public or private, within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Baltimore any information of any type related to or containing messages or locutions allegedly received from the Virgin Mother of God. many messages assuring them that she is not leaving Emmitsburg. The February 5, 2006 message, for instance, assures listeners that Emmitsburg is the Center of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart despite opposition from some Church leaders, then continues, “Know that I am not leaving and that I intercede for all good things for you before the Throne of God.” The October 5, 2008 message (just before the Pastoral Advisory was released) repeats this theme: “know that I am here with you. I am not leaving , even if you think I am far away.”

many messages assuring them that she is not leaving Emmitsburg. The February 5, 2006 message, for instance, assures listeners that Emmitsburg is the Center of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart despite opposition from some Church leaders, then continues, “Know that I am not leaving and that I intercede for all good things for you before the Throne of God.” The October 5, 2008 message (just before the Pastoral Advisory was released) repeats this theme: “know that I am here with you. I am not leaving , even if you think I am far away.” Revelations 12:1 is another helpful source of historical information. Both organizations maintain websites easily accessible by any internet search engine, the Foundation of the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary and Private Revelations of Our Lady of Emmitsburg . Both organizations officially are located in Pennsylvania and are thus outside the jurisdiction of the Baltimore Archdiocese and its prohibitions. Notably, Gianna disavowed any involvement with The Foundation in her 2008 response to the Pastoral Advisory.

Revelations 12:1 is another helpful source of historical information. Both organizations maintain websites easily accessible by any internet search engine, the Foundation of the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary and Private Revelations of Our Lady of Emmitsburg . Both organizations officially are located in Pennsylvania and are thus outside the jurisdiction of the Baltimore Archdiocese and its prohibitions. Notably, Gianna disavowed any involvement with The Foundation in her 2008 response to the Pastoral Advisory. age and was never able to pinpoint the exact moment of her conversion. She married Walter Palmer on September 28, 1827. They had six children, three of whom lived to adulthood. The Palmers were active laypeople in the Methodist Episcopal Church and participated in numerous charitable activities. Both taught Sunday school classes. In 1839, Phoebe Palmer became the first woman to lead a class of both women and men in New York City.

age and was never able to pinpoint the exact moment of her conversion. She married Walter Palmer on September 28, 1827. They had six children, three of whom lived to adulthood. The Palmers were active laypeople in the Methodist Episcopal Church and participated in numerous charitable activities. Both taught Sunday school classes. In 1839, Phoebe Palmer became the first woman to lead a class of both women and men in New York City. churches and at camp meetings [Image at right], which generally were held outdoors in more rural areas. The content of her sermons was the same regardless of the location. Palmer did not ignore the goal of bringing sinners to Christ through sermons, which was historically the focus of revivals, but her emphasis was on holiness. By 1853 her schedule included Canada. Her labors there in 1857 resulted in more than 2,000 conversions and hundreds of Christians who claimed the baptism of the Holy Ghost or holiness (Palmer 1859:259). Her ministry there contributed to the general Prayer Revival of 1857–1858, which resulted in more than 2,000,000 converts in the United States and the British Isles. Between 1859 and 1863, Palmer preached at fifty-nine locations throughout the British Isles (White 1986:241–42). At one meeting in Sunderland, 3,000 attended her services held over a period of twenty-nine days, with some people turned away. She reported 2,000 seekers there, including approximately 200 who experienced holiness under her preaching (Wheatley 1881:355, 356). Between 1866 and 1870 she held services throughout the United States and eastern Canada (Raser 1987:69–70). At a camp meeting in Goderich, Canada in 1868, about 6,000 gathered to hear her preach (Wheatley 1881:445, 415). Palmer continued to accept preaching engagements until shortly before her death. Overall, she preached before hundreds of thousands of people at more than 300 camp meetings and revivals.

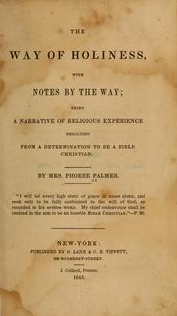

churches and at camp meetings [Image at right], which generally were held outdoors in more rural areas. The content of her sermons was the same regardless of the location. Palmer did not ignore the goal of bringing sinners to Christ through sermons, which was historically the focus of revivals, but her emphasis was on holiness. By 1853 her schedule included Canada. Her labors there in 1857 resulted in more than 2,000 conversions and hundreds of Christians who claimed the baptism of the Holy Ghost or holiness (Palmer 1859:259). Her ministry there contributed to the general Prayer Revival of 1857–1858, which resulted in more than 2,000,000 converts in the United States and the British Isles. Between 1859 and 1863, Palmer preached at fifty-nine locations throughout the British Isles (White 1986:241–42). At one meeting in Sunderland, 3,000 attended her services held over a period of twenty-nine days, with some people turned away. She reported 2,000 seekers there, including approximately 200 who experienced holiness under her preaching (Wheatley 1881:355, 356). Between 1866 and 1870 she held services throughout the United States and eastern Canada (Raser 1987:69–70). At a camp meeting in Goderich, Canada in 1868, about 6,000 gathered to hear her preach (Wheatley 1881:445, 415). Palmer continued to accept preaching engagements until shortly before her death. Overall, she preached before hundreds of thousands of people at more than 300 camp meetings and revivals. synonyms for holiness, such as sanctification, full salvation, promise of the Father, entire consecration, and perfect love. Her first book, The Way of Holiness with Notes by the Way (1843), [Image at right] was her spiritual autobiography that provided a roadmap for achieving holiness. Based on her own pursuit of holiness she explained a “shorter way,” which consisted of three steps: consecration, followed by faith, and then testimony.

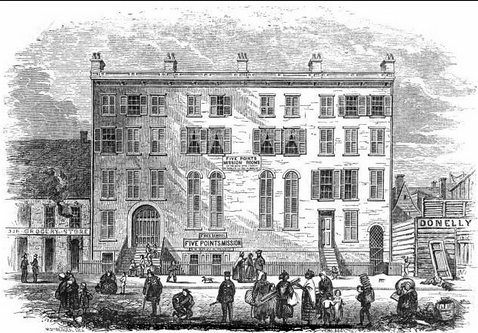

synonyms for holiness, such as sanctification, full salvation, promise of the Father, entire consecration, and perfect love. Her first book, The Way of Holiness with Notes by the Way (1843), [Image at right] was her spiritual autobiography that provided a roadmap for achieving holiness. Based on her own pursuit of holiness she explained a “shorter way,” which consisted of three steps: consecration, followed by faith, and then testimony. holiness believers engaged in activities that exhibited God’s love to those around them. This expression of social Christianity motivated by God’s love has become known as social holiness. It reflected Palmer’s emphasis on the responsibility of holiness adherents to be useful. Her ministry in the slums of New York City modeled social holiness. A notable example was her prominent role in founding the Five Points Mission in 1850 in lower Manhattan where the worst slums in New York City converged. Committed to addressing both the spiritual and physical needs of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, the Mission became one of the first settlement houses in the United States with a chapel, schoolrooms, and housing for twenty families (Raser 1987, 217).

holiness believers engaged in activities that exhibited God’s love to those around them. This expression of social Christianity motivated by God’s love has become known as social holiness. It reflected Palmer’s emphasis on the responsibility of holiness adherents to be useful. Her ministry in the slums of New York City modeled social holiness. A notable example was her prominent role in founding the Five Points Mission in 1850 in lower Manhattan where the worst slums in New York City converged. Committed to addressing both the spiritual and physical needs of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, the Mission became one of the first settlement houses in the United States with a chapel, schoolrooms, and housing for twenty families (Raser 1987, 217).

knowledge” there was no medical explanation for the cure. The theologians concluded that the boy had been healed through miraculous intercession. On December 19, 2011, the Holy Father authorized the promulgation of the decree recognizing the miracle attributed to the intercession of Kateri Tekakwitha. On October 21, 2012, her canonization was celebrated in Rome by Pope Benedict XVI in front of thousands of North American Native Catholics. Since 2012, more visitors have been coming to the shrine which is regarded as a pilgrimage center.

knowledge” there was no medical explanation for the cure. The theologians concluded that the boy had been healed through miraculous intercession. On December 19, 2011, the Holy Father authorized the promulgation of the decree recognizing the miracle attributed to the intercession of Kateri Tekakwitha. On October 21, 2012, her canonization was celebrated in Rome by Pope Benedict XVI in front of thousands of North American Native Catholics. Since 2012, more visitors have been coming to the shrine which is regarded as a pilgrimage center. Tekakwitha around the Church on October 20, 2014. The procession was followed by the testimonies of a person healed by the intercessory prayers to Saint Kateri. The ceremony concluded with the Our Father in the Mohawk language. The exact anniversary, October 21, began with the Eucharistic celebration; Ron Boyer narrated “The life of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.” Eucharistic Adoration and Benediction followed. In the afternoon, the Anointing with Saint Kateri’s relic and Blessed oil was offered, and the day closed on Our Father prayed in Mohawk.

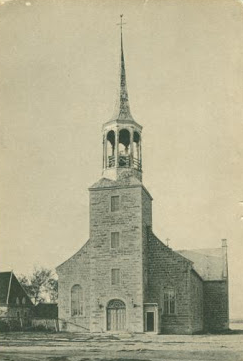

Tekakwitha around the Church on October 20, 2014. The procession was followed by the testimonies of a person healed by the intercessory prayers to Saint Kateri. The ceremony concluded with the Our Father in the Mohawk language. The exact anniversary, October 21, began with the Eucharistic celebration; Ron Boyer narrated “The life of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.” Eucharistic Adoration and Benediction followed. In the afternoon, the Anointing with Saint Kateri’s relic and Blessed oil was offered, and the day closed on Our Father prayed in Mohawk. where a cemetery must have been. All of the buildings were constructed with grey Montreal stone. The old bell donated by King William IV of England stands on the left lawn on the street side. The Kateri Center, located in a nearby house, publishes the quarterly Kateri and administers all the activitites at the sanctuary.

where a cemetery must have been. All of the buildings were constructed with grey Montreal stone. The old bell donated by King William IV of England stands on the left lawn on the street side. The Kateri Center, located in a nearby house, publishes the quarterly Kateri and administers all the activitites at the sanctuary. rectangular white Carrara marble tomb bears the inscription: “Kaiatanoron Kateri Tekakwitha, 1656-1680”. Kaiatanoron means “blessed, precious and dear.”

rectangular white Carrara marble tomb bears the inscription: “Kaiatanoron Kateri Tekakwitha, 1656-1680”. Kaiatanoron means “blessed, precious and dear.” decades of conquest, being the allies of the British, the Iroquois were mostly evangelized by Protestant missionaries, and when New France became part of the British Empire, many Catholic Mohawks joined various Protestant denominations. This trend is also visible in their speaking English even though the reservation is located within French speaking Quebec. When in conflict with the Quebec authorities and police forces, they make a point of not speaking French as a sign of resistance (as occurred during the Oka Crisis that in 1990 involved Kahnawake and the Mercier Bridge that straddles part of it). Even if everything in the shrine is bilingual, it is connected historically to the French period of colonization and may have suffered from this.

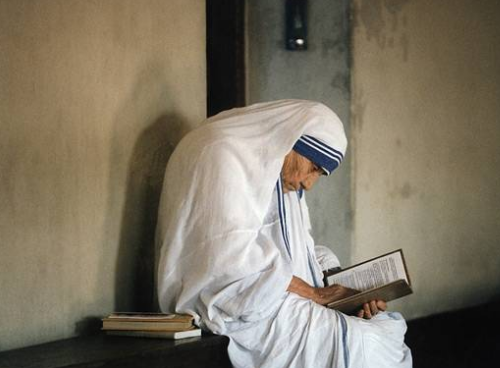

decades of conquest, being the allies of the British, the Iroquois were mostly evangelized by Protestant missionaries, and when New France became part of the British Empire, many Catholic Mohawks joined various Protestant denominations. This trend is also visible in their speaking English even though the reservation is located within French speaking Quebec. When in conflict with the Quebec authorities and police forces, they make a point of not speaking French as a sign of resistance (as occurred during the Oka Crisis that in 1990 involved Kahnawake and the Mercier Bridge that straddles part of it). Even if everything in the shrine is bilingual, it is connected historically to the French period of colonization and may have suffered from this. live her life for God and service to others. After a childhood and adolescence spent devoted to church activities, including singing, playing the mandolin, participating in a youth group, as well as teaching the catechism to younger members, in 1928, at eighteen years old, Agnes left her home to join the Loreto Sisters of Dublin. She first travelled to France to be interviewed, and when found suitable, was sent her to Ireland where she learned English and took the name “Mary Teresa,” for Saint Therese of Lisieux, the patron saint of missions (Greene 2008:17-18). In 1929, during her novitiate period, she was sent to Calcutta, India, to teach at St. Mary’s High School for Girls. During her time as a novice, she learned Bengali and Hindi, taught geography and history, and took her initial vows in 1931. When she took her final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in 1937, she also took the name “Mother,” to precede Teresa, as is the custom in the order of the Loreto Sisters.

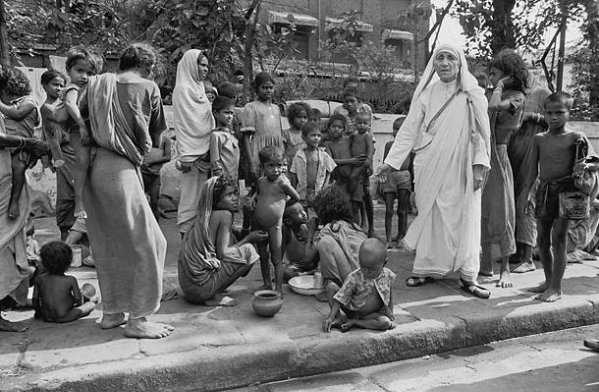

live her life for God and service to others. After a childhood and adolescence spent devoted to church activities, including singing, playing the mandolin, participating in a youth group, as well as teaching the catechism to younger members, in 1928, at eighteen years old, Agnes left her home to join the Loreto Sisters of Dublin. She first travelled to France to be interviewed, and when found suitable, was sent her to Ireland where she learned English and took the name “Mary Teresa,” for Saint Therese of Lisieux, the patron saint of missions (Greene 2008:17-18). In 1929, during her novitiate period, she was sent to Calcutta, India, to teach at St. Mary’s High School for Girls. During her time as a novice, she learned Bengali and Hindi, taught geography and history, and took her initial vows in 1931. When she took her final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in 1937, she also took the name “Mother,” to precede Teresa, as is the custom in the order of the Loreto Sisters. impoverished adults, and opening a home for the dying, Mother Teresa had garnered financial as well as local community support. She obtained permission from the Vatican to start her own order with twelve other women who were either former students or teachers at St. Mary’s High School for Girls in Calcutta. They came to be called “Missionaries of Charity,” and were known for taking a fourth vow. After vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, the sisters of this new order also vowed to “give whole-hearted and free service to the poorest of the poor” (Greene 2008:48). Pope John Paul VI awarded Missionaries of Charity the Decree of Praise in 1965, which allowed the order to expand internationally. With the help of organized lay people and lay faithful, called Co-Workers, Missionaries of Charity opened over 600 hospices, schools, counseling services, medical care facilities, homeless shelters, orphanages, and programs for alcoholism and addiction in more than 120 countries by 1997. The Missionaries succeeded in reaching countries in six of the seven continents with their aid.

impoverished adults, and opening a home for the dying, Mother Teresa had garnered financial as well as local community support. She obtained permission from the Vatican to start her own order with twelve other women who were either former students or teachers at St. Mary’s High School for Girls in Calcutta. They came to be called “Missionaries of Charity,” and were known for taking a fourth vow. After vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, the sisters of this new order also vowed to “give whole-hearted and free service to the poorest of the poor” (Greene 2008:48). Pope John Paul VI awarded Missionaries of Charity the Decree of Praise in 1965, which allowed the order to expand internationally. With the help of organized lay people and lay faithful, called Co-Workers, Missionaries of Charity opened over 600 hospices, schools, counseling services, medical care facilities, homeless shelters, orphanages, and programs for alcoholism and addiction in more than 120 countries by 1997. The Missionaries succeeded in reaching countries in six of the seven continents with their aid. group to the Sisters, The Missionary of Charity Brothers, was established. Three years later Fr. Ian Travers-Ball (Brother Andrew), a Jesuit priest from Australia assumed leadership of the Brothers and headed the group for the first twenty years of its history. Contemplative branches of the Missionaries of Charity, sisters and brothers, were established in 1976 and 1979, respectively, and are devoted to prayer, penance and service. Daily routine in the contemplative branches involves substantial time devoted to prayer, spiritual reading, and silence. The Corpus Christi Movement for Priests was formed in 1981, after expressions of interest by a number of priests. Finally, in 1984, Mother Teresa co-founded the Missionaries of Charity Fathers with Friar Joseph Langford. Other organizations affiliated with the Missionaries of Charity include The Co-Workers of Mother Teresa, The Sick and Suffering Co-Workers, and The Lay Missionaries of Charity (Greene 2008:140).

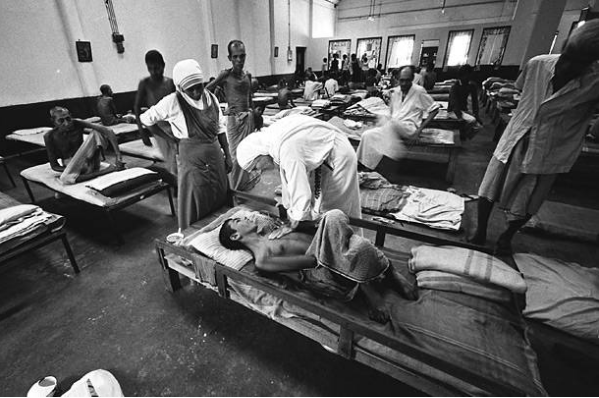

group to the Sisters, The Missionary of Charity Brothers, was established. Three years later Fr. Ian Travers-Ball (Brother Andrew), a Jesuit priest from Australia assumed leadership of the Brothers and headed the group for the first twenty years of its history. Contemplative branches of the Missionaries of Charity, sisters and brothers, were established in 1976 and 1979, respectively, and are devoted to prayer, penance and service. Daily routine in the contemplative branches involves substantial time devoted to prayer, spiritual reading, and silence. The Corpus Christi Movement for Priests was formed in 1981, after expressions of interest by a number of priests. Finally, in 1984, Mother Teresa co-founded the Missionaries of Charity Fathers with Friar Joseph Langford. Other organizations affiliated with the Missionaries of Charity include The Co-Workers of Mother Teresa, The Sick and Suffering Co-Workers, and The Lay Missionaries of Charity (Greene 2008:140). States Senators during the 1980s Savings and Loan crisis. The Missionaries of Charity has also been accused of allowing and ignoring squalid conditions to persist at Charity supported facilities, such as hospices and orphanages, while refusing to make public accountings of their expenditures of funds to support these facilities (Hitchens 1995). As one critic reported, “The donations rolled in and were deposited in the bank, but they had no effect on our ascetic lives and very little effect on the lives of the poor we were trying to help” (Shields 1998). Another critic has alleged that homes for the dying run by the Missionaries of Charity are known for having a lack of doctors to properly diagnose patients’ illnesses, using previously used or unsanitary hypodermic needles, refusing to administer pain killers to those in excruciating pain, and otherwise relying on outdated and dangerous medical practices (Fox 1994). An undercover volunteer authored reports of abusive treatment of children; he reports having seen children bound, force-fed, and left outside at night during monsoon rains (MacIntyre 2005). In addition to criticism from the medical personnel and investigative journalists, former co-workers and former Sisters in the Missionaries of Charity, including Colette Livermore (2008), have written similar accounts of the poor treatment of the suffering the Sisters were ostensibly committed to helping. According to Fox (1994), the Missionaries of Charity justify what would appear to be the furthering of suffering of the needy, abandoned, and afflicted, as reflecting Mother Teresa’s teaching that suffering brings one closer to Jesus. She allegedly has equated the suffering of man with that of Christ and therefore a gift. This “theology of suffering,” has caused the disillusionment among a number of former co-workers and Sisters (Livermore 2008), and caused skepticism about the organizations commitment to the fourth vow of “wholehearted and free service to the poorest of the poor.”

States Senators during the 1980s Savings and Loan crisis. The Missionaries of Charity has also been accused of allowing and ignoring squalid conditions to persist at Charity supported facilities, such as hospices and orphanages, while refusing to make public accountings of their expenditures of funds to support these facilities (Hitchens 1995). As one critic reported, “The donations rolled in and were deposited in the bank, but they had no effect on our ascetic lives and very little effect on the lives of the poor we were trying to help” (Shields 1998). Another critic has alleged that homes for the dying run by the Missionaries of Charity are known for having a lack of doctors to properly diagnose patients’ illnesses, using previously used or unsanitary hypodermic needles, refusing to administer pain killers to those in excruciating pain, and otherwise relying on outdated and dangerous medical practices (Fox 1994). An undercover volunteer authored reports of abusive treatment of children; he reports having seen children bound, force-fed, and left outside at night during monsoon rains (MacIntyre 2005). In addition to criticism from the medical personnel and investigative journalists, former co-workers and former Sisters in the Missionaries of Charity, including Colette Livermore (2008), have written similar accounts of the poor treatment of the suffering the Sisters were ostensibly committed to helping. According to Fox (1994), the Missionaries of Charity justify what would appear to be the furthering of suffering of the needy, abandoned, and afflicted, as reflecting Mother Teresa’s teaching that suffering brings one closer to Jesus. She allegedly has equated the suffering of man with that of Christ and therefore a gift. This “theology of suffering,” has caused the disillusionment among a number of former co-workers and Sisters (Livermore 2008), and caused skepticism about the organizations commitment to the fourth vow of “wholehearted and free service to the poorest of the poor.” Holy See, governed by Pope John Paul II, started the process in 1997. She was beatified in 2003, making her known to the Catholic community as “Blessed” Mother Teresa. The Holy See also abandoned the process of adversarial investigation, a process to critically explore her extraordinary work. Two miracles, involving the personal intercession of Mother Teresa, are also required as part of the process of consideration for sainthood. There is currently only one claim of a miracle, made by a Bengali woman who maintains that she was miraculously healed after holding a locket with a picture of Mother Teresa to her abdomen. However, this one claim is contested as both the woman’s husband and the attending physician insist that the woman’s cysts were cured after nearly a year of medication and treatment (Rohde 2003).

Holy See, governed by Pope John Paul II, started the process in 1997. She was beatified in 2003, making her known to the Catholic community as “Blessed” Mother Teresa. The Holy See also abandoned the process of adversarial investigation, a process to critically explore her extraordinary work. Two miracles, involving the personal intercession of Mother Teresa, are also required as part of the process of consideration for sainthood. There is currently only one claim of a miracle, made by a Bengali woman who maintains that she was miraculously healed after holding a locket with a picture of Mother Teresa to her abdomen. However, this one claim is contested as both the woman’s husband and the attending physician insist that the woman’s cysts were cured after nearly a year of medication and treatment (Rohde 2003). and organizations, she has become a prominent and much loved figure in India, the Catholic community, and all over the world. In 1971, Mother Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize for “bringing help to suffering humanity.” She was also awarded honors such as India’s Padma Shri and the Jawajarlal Nehru Award for International Understanding, England’s Order of Merit, the Gold Medal of the Soviet Peace Committee, the United States Congressional Gold Medal, along with over a hundred other awards, including honorary degrees from a number of other countries and organizations for her endeavors with Missionaries of Charity. Perhaps the most impressive indicator of widespread respect for Mother Teresa is that she was ranked first in the United States’ 1999 Gallup Poll’s List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20 th Century, ahead of luminaries such as Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, and Pope John Paul II.

and organizations, she has become a prominent and much loved figure in India, the Catholic community, and all over the world. In 1971, Mother Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize for “bringing help to suffering humanity.” She was also awarded honors such as India’s Padma Shri and the Jawajarlal Nehru Award for International Understanding, England’s Order of Merit, the Gold Medal of the Soviet Peace Committee, the United States Congressional Gold Medal, along with over a hundred other awards, including honorary degrees from a number of other countries and organizations for her endeavors with Missionaries of Charity. Perhaps the most impressive indicator of widespread respect for Mother Teresa is that she was ranked first in the United States’ 1999 Gallup Poll’s List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20 th Century, ahead of luminaries such as Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, and Pope John Paul II. had six children (George, Benjamin, Jr., John, Jane, Sammy and Rebecca) (Newport 2006 :117). The Rodens joined a Seventh-day Adventist church at Kilgore, Texas in 1940. They were fully committed to the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist prophet

had six children (George, Benjamin, Jr., John, Jane, Sammy and Rebecca) (Newport 2006 :117). The Rodens joined a Seventh-day Adventist church at Kilgore, Texas in 1940. They were fully committed to the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist prophet  Israel during the next several years trying to achieve this goal. They created a pilot settlement at Amirim, which Lois directed. But the group as a whole never moved there (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:199). Whereas Ben was quiet, Lois was characterized as “exceptionally dynamic and [the leader of] the group for a number of years” (Newport 2006:115, 136).

Israel during the next several years trying to achieve this goal. They created a pilot settlement at Amirim, which Lois directed. But the group as a whole never moved there (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:199). Whereas Ben was quiet, Lois was characterized as “exceptionally dynamic and [the leader of] the group for a number of years” (Newport 2006:115, 136). published a mimeographed three-part study entitled By His Spirit (Roden 1980). The group secured an offset press, and in December 1980 she launched SHEkinah, [Image at right] a regularly published journal for disseminating her teaching (Roden and Doyle 1980–1983). She, along with Clive Doyle as co-editor and printer, searched newspapers, popular magazines and academic publications for articles that explored the ideas of the feminine character of God and the ordination of women. Some mainline Protestant denominations had begun ordaining women in the 1950s, and many more denominations began ordaining women as ministers in the 1970s. Meanwhile, feminist scholars studying the early Christian churches found evidence for belief in the feminine character of God and the existence of female clergy among early Christian churches.

published a mimeographed three-part study entitled By His Spirit (Roden 1980). The group secured an offset press, and in December 1980 she launched SHEkinah, [Image at right] a regularly published journal for disseminating her teaching (Roden and Doyle 1980–1983). She, along with Clive Doyle as co-editor and printer, searched newspapers, popular magazines and academic publications for articles that explored the ideas of the feminine character of God and the ordination of women. Some mainline Protestant denominations had begun ordaining women in the 1950s, and many more denominations began ordaining women as ministers in the 1970s. Meanwhile, feminist scholars studying the early Christian churches found evidence for belief in the feminine character of God and the existence of female clergy among early Christian churches. to meet the needs of her day. Victor Houteff [Image at right] established the style of leadership practiced among the Davidians/Branch Davidians. He set forth the organization of the General Association of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists in a constitution he called The Leviticus (Houteff 1943). In it he was named the president; the other executive officers ( vice president, treasurer and secretary ) were family members and one close associate who held office only as long as they were approved by the president. Following Houteff’s lead, Ben Roden also composed a Leviticus for the General Association of the Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists.

to meet the needs of her day. Victor Houteff [Image at right] established the style of leadership practiced among the Davidians/Branch Davidians. He set forth the organization of the General Association of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists in a constitution he called The Leviticus (Houteff 1943). In it he was named the president; the other executive officers ( vice president, treasurer and secretary ) were family members and one close associate who held office only as long as they were approved by the president. Following Houteff’s lead, Ben Roden also composed a Leviticus for the General Association of the Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists. challenges to her leadership from male competitors. First, her son George [Image at right] was a rival throughout her years of prophetic leadership. He offered both gender and theological arguments to support his claim to succeed his father as prophet; failing that, he resorted to force. He was mentally unstable and violent, carrying a gun on the Mount Carmel grounds and into the church and threatening people (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:53–54). Because of fear of George Roden’s violence, the majority of the Branch Davidians, along with their new leader

challenges to her leadership from male competitors. First, her son George [Image at right] was a rival throughout her years of prophetic leadership. He offered both gender and theological arguments to support his claim to succeed his father as prophet; failing that, he resorted to force. He was mentally unstable and violent, carrying a gun on the Mount Carmel grounds and into the church and threatening people (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:53–54). Because of fear of George Roden’s violence, the majority of the Branch Davidians, along with their new leader to live there while her son George took control of the property. She died on November 10, 1986 at age seventy, and her body was transported to Israel for burial. George Roden lost control of the Mount Carmel property to Koresh’s Branch Davidians in 1988 while George was imprisoned for threatening a judge. He subsequently killed a man and spent the rest of his years in a state mental hospital.

to live there while her son George took control of the property. She died on November 10, 1986 at age seventy, and her body was transported to Israel for burial. George Roden lost control of the Mount Carmel property to Koresh’s Branch Davidians in 1988 while George was imprisoned for threatening a judge. He subsequently killed a man and spent the rest of his years in a state mental hospital. Ellen Bracewell, was a nanny for the local gentry and her father, Bruce Bracewell, was a tradesman and interior decorator for great manor homes in England. His ancestors had been weavers. Olga loved reading, showed an early talent in music, and possessed a clear and pure soprano voice. She attended various schools in the suburbs of Birmingham until the age of fourteen when she won a scholarship to Aston Pupil Teachers’ Centre for three years, intending to become a teacher.

Ellen Bracewell, was a nanny for the local gentry and her father, Bruce Bracewell, was a tradesman and interior decorator for great manor homes in England. His ancestors had been weavers. Olga loved reading, showed an early talent in music, and possessed a clear and pure soprano voice. She attended various schools in the suburbs of Birmingham until the age of fourteen when she won a scholarship to Aston Pupil Teachers’ Centre for three years, intending to become a teacher. understanding, Charles Sydney McGaffin, who after his death became her spiritual partner working with her from the life beyond death.

understanding, Charles Sydney McGaffin, who after his death became her spiritual partner working with her from the life beyond death. recounted in Between Time and Eternity, these came entirely unsought, and at first she was uncomfortable with them. It was only in her later years that she spoke of them to friends, and compiled her spiritual records for distribution to acquaintances who expressed interest. By this time such experiences were so extensive that she simply accepted their unusualness, and hoped they would be of help to others.

recounted in Between Time and Eternity, these came entirely unsought, and at first she was uncomfortable with them. It was only in her later years that she spoke of them to friends, and compiled her spiritual records for distribution to acquaintances who expressed interest. By this time such experiences were so extensive that she simply accepted their unusualness, and hoped they would be of help to others. frequently, on almost a or weekly basis. Some of Olga’s most significant visions are described in her own words on a website containing her self-published writings: the story of the psychic vase and its shattering; a viewing of the panorama of religions throughout the ages; an experience of the Cosmic Christ as Osiris in the Great Pyramid of Giza; an out-of-body tour of the Church of Christ of the Future; an account of the Temple of God Consciousness; and her receiving of third-eye vision (“The Communion Service” n.d.).