PEOPLES TEMPLE TIMELINE

1931 (May 13): James (Jim) Warren Jones was born in Crete, Indiana.

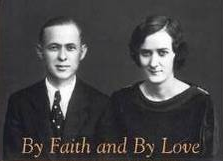

1949 (June 12): Marceline Mae Baldwin married James (Jim) Warren Jones.

1954: Jim and Marceline Jones founded Community Unity Church in Indianapolis, Indiana.

1956: Peoples Temple, the renamed Wings of Deliverance (first incorporated 1955), opened in Indianapolis.

1960: People Temple officially became a member of The Disciples of Christ (Christian Church) denomination.

1962: Jim Jones and family lived in Brazil.

1965 (July): Jones, his family, and 140 members of his interracial congregation moved to Redwood Valley, California.

1972: Peoples Temple purchased church buildings in Los Angeles (September) and San Francisco (December).

1974 (Summer): Peoples Temple pioneers began clearing land in the Northwest District of Guyana, South America to develop the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project.

1975 (December): Al and Jeannie Mills, Peoples Temple apostates, founded the Human Freedom Center.

1976 (February): Peoples Temple signed a lease with the Government of Guyana “to cultivate and beneficially occupy at least one-fifth” of 3,852 acres located in the Northwest District of Guyana.

1977 (Summer): Approximately 600 Peoples Temple members moved to Jonestown in a three-month period.

1977 (August): New West Magazine published an exposé of life inside Peoples Temple based upon apostate accounts.

1977 (Summer): Tim Stoen founded the “Concerned Relatives,” an activist group of apostates and family members that urged government agencies and media outlets to investigate Peoples Temple.

1977 (September): A “six-day-siege” staged by Jim Jones occurred in Jonestown in which residents believe they are under attack.

1978 (November 17): California Congressman Leo J. Ryan, members of the Concerned Relatives, and members of the media visited Jonestown.

1978 (November 18): Ryan, three journalists (Robert Brown, Don Harris, and Greg Robinson) and one Peoples Temple member (Patricia Parks) were killed in an ambush of gunfire at the Port Kaituma airstrip, six miles from Jonestown. After the assault at the airstrip more than 900 residents, following the orders of Jones, ingested poison in the Jonestown pavilion. Jones died of a gunshot wound to the head.

1979 (March): The Guyana Emergency Relief Committee obtained funding to transport more than 400 unidentified and unclaimed bodies from Dover, Delaware to be interred at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California. A small monument was erected.

2011 (May 29): A dedication service occurred observing the installation of four memorial plaques at Evergreen Cemetery listing the names of all who died in Jonestown.

2018 (November 18): A memorial service marked the renovation of the burial site, along with the installation of a small monument noting the 2011 dedication.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

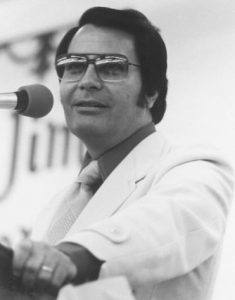

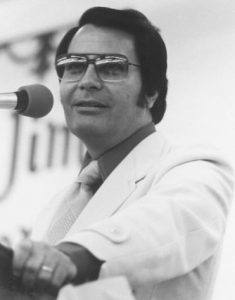

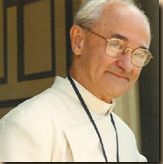

James Warren Jones [Image at right] was born May 13, 1931 to a working class family at the height of the Great Depression in Crete, Indiana (Hall 1987:4). His father, James Thurman Jones, was a disabled veteran, while his mother, Lynetta Putnam Jones, was the principal breadwinner and responsible parent in the family. She greatly influenced her son’s interests in social justice and equality. She was skeptical of organized religion, but did believe in spirits—a belief she communicated to her son (Hall 1987:6). A neighbor took him to Pentecostal church services as a child, and this undoubtedly shaped his understanding of worship as an intensely emotional experience. What emerged from these influences was a self-styled theology that combined aspects of Pentecostalism with social idealism. Jones met Marceline Baldwin in Richmond, Indiana, and the 18-year-old Jones married the 22-year-old on June 12, 1949. The couple moved to Indianapolis in 1951 to attend school.

By 1954, Jones had established his own church, called Community Unity, in Indianapolis (Moore 2009:12). That same year, he preached as a guest minister at the Laurel Street Tabernacle in Indianapolis, Indiana, an Assemblies of God church within the Pentecostal tradition (Hall 1987:42). While the church administrative board lamented Jones’ inclusion of African Americans from his Community Unity Church, his charismatic style attracted a number of working class white members away from the Laurel Street congregation. Jim and Marceline incorporated the Wings of Deliverance on April 4, 1955; a year later, they re-incorporated, moved, and renamed their organization Peoples Temple (Hall 1987:43). By 1957 the Peoples Temple Apostolic Church had gained a reputation in Indianapolis for practicing a social gospel ministry. The congregation voted in 1959 to  affiliate with the Disciples of Christ (Christian Church), and in 1960 the Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel [Image at right] became an official member of the denomination (Moore 2009:13).

affiliate with the Disciples of Christ (Christian Church), and in 1960 the Peoples Temple Christian Church Full Gospel [Image at right] became an official member of the denomination (Moore 2009:13).

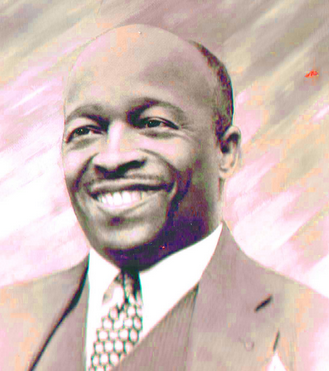

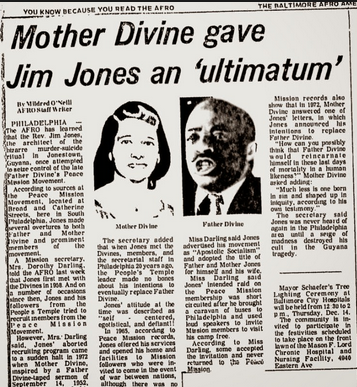

Throughout the 1950s, Jim and Marceline visited Father Divine’s Peace Mission in Philadelphia. Jones was impressed with Father Divine’s interracial vision, his charismatic abilities, and his successful business cooperatives. He also adopted Divine’s practice of having parishioners call him “Father,” and calling Marceline “Mother.” After Father Divine died, Jones attempted to take over the Peace Mission, but Mother Divine rejected his advances. Nevertheless, a number of elderly African American members were attracted to the Temple’s message and moved westward (Moore 2009:16-17).

Jones’ commitment to racial equality led him briefly to chair the Indianapolis Human Rights Commission in 1961. But a vision of nuclear holocaust, coupled with an article in the January 1962 issue of Esquire Magazine identifying the safest places in case of nuclear attack, prompted him to take his family to Belo Horizonte, Brazil, one of the places listed. The Temple continued in Indianapolis without Jones, but faltered without his leadership. Upon his return in 1965, he persuaded about 140 people, half of them African Americans and half Caucasians, to move to Redwood Valley in the California wine country, another safe venue identified by Esquire (Hall 1987:62). There they constructed a new church building and several administrative offices, and began operating a number of care homes for senior citizens and mentally challenged youth.

The progressive political scene in California was yet another reason for Jones’ move west (Harris and Waterman 2004). In Redwood Valley Jones began to recruit young, college-educated whites to complement the large number of working class families who already belonged to Peoples Temple. This cadre of relatively affluent members—most of whom had developed a commitment to peace and justice as part of the Civil Rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests—assisted poorer members in navigating the social welfare system. They provided a number of services that enabled the poor to receive the benefits to which they were entitled, especially senior citizens who had trouble collecting the Social Security payments they had earned. When the Temple opened a church in the Fillmore District of San Francisco, it attracted thousands of African Americans as well as city officials and political figures. In the heart of the ghetto, the group offered free blood pressure testing for senior citizens, free sickle-cell anemia testing for African Americans, and free child care for working parents. It also hosted a variety of progressive political speakers, from Angela Davis to Dennis Banks.

Hundreds of Temple members lived communally in Redwood Valley, San Francisco, and, less so, in Los Angeles. Older members signed life-care contracts, contributing their Social Security checks in return for room and board, health care, and the goods and services needed for their retirement. In Redwood Valley, Temple members established and operated several care homes for the elderly, the mentally ill, and the mentally challenged, and these enterprises raised money for the group. Those who “went communal,” as Temple members describe it, donated their paychecks to the group and received minimal life support: cramped quarters, a small allowance for necessities, communal meals. Traditional fundraising appeals through mass mailings supported some of the Temple’s many social programs (Levi 1982:xii). A Planning Commission, comprised of about 100 Temple leaders, discussed major organizational decisions, with Jones retaining final decision-making authority.

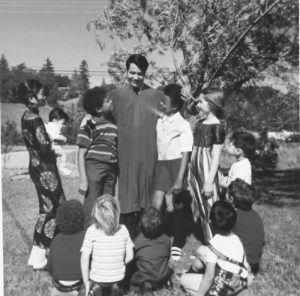

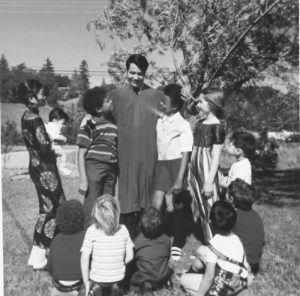

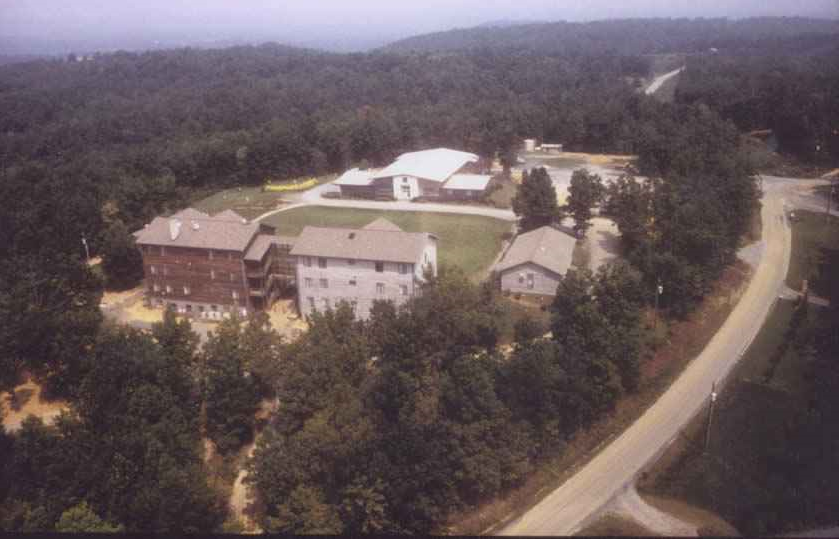

In 1974, the Temple leadership negotiated with the South American nation of Guyana to develop nearly 4,000 acres in the Northwest District of the country on the  Venezuelan border. By the time the Temple signed an official lease for the land in 1976, pioneers from the group had already spent two years of back-breaking labor [Image at right] to clear jungle in Guyana in order to establish what they called the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. Guyana, a multiracial state and the only English-speaking country in South America, declared itself to be a cooperative socialist republic. Its black minority government welcomed the prospect of serving as a refuge for Americans fleeing a racist and oppressive society. Moreover, having a large group of ex-patriate Americans so close to the border with Venezuela assured U.S. interest in the area under dispute (Moore 2009:42). The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project grew slowly at first, housing only about 50 people as late as the first months of 1977, but it expanded to more than 400 residents by April, and to 1,000 by the end of the year (Moore 2009:44).

Venezuelan border. By the time the Temple signed an official lease for the land in 1976, pioneers from the group had already spent two years of back-breaking labor [Image at right] to clear jungle in Guyana in order to establish what they called the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project. Guyana, a multiracial state and the only English-speaking country in South America, declared itself to be a cooperative socialist republic. Its black minority government welcomed the prospect of serving as a refuge for Americans fleeing a racist and oppressive society. Moreover, having a large group of ex-patriate Americans so close to the border with Venezuela assured U.S. interest in the area under dispute (Moore 2009:42). The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project grew slowly at first, housing only about 50 people as late as the first months of 1977, but it expanded to more than 400 residents by April, and to 1,000 by the end of the year (Moore 2009:44).

Various pressures led to the relatively speedy immigration from California to Guyana. One impetus was the U.S. Internal Revenue Service’s examination of the Temple’s business-related income. This threatened the church’s tax-exempt status, and raised the potential of shutting down the organization (Hall 1987:197-98). Another incentive derived from the activities of a group of disaffected former members and relatives of current members of Peoples Temple. Known as The Concerned Relatives, the group lobbied various government agencies to investigate the Temple, alleging a number of abuses as well as criminal activity. The Concerned Relatives also brought these same allegations to news media outlets. A highly critical article published in New West Magazine featuring criticism from former members who publicly blasted the Temple and its leadership, was apparently the precipitating factor to drive Jones immediately to Guyana, which he never left (Moore 2009:38-39).

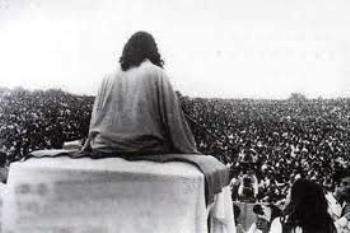

At some point in 1977, the agricultural project became known as Jonestown. [Image at right] Conditions were difficult, but hope was high for life in the “Promised Land,” as Temple members back in the U.S. called it. The work needed to maintain a community of a thousand souls was immense. Members worked in agriculture, construction, maintenance (such as cooking and laundry), childcare for the 304 minors under the age of 18 living there, education, healthcare, and fundraising (making items to sell in Georgetown, which was not easily accessible from Jonestown). Everyone contributed to the community, at times working eleven hours a day, six days a week. Evenings were filled with meetings, educational programs, Russian language lessons (for what people believed was an imminent move to the Soviet Union) and other duties. Residents lived in dormitories, and frequently children were raised apart from their biological parents.

At first the diet was adequate, but as more people arrived, portions became relatively smaller, consisting mainly of beans and rice, with meat or green vegetables reserved for meals when outsiders visited the community. When people such as U.S. Embassy officials, Guyana government representatives, and supportive family members and friends did visit, residents of Jonestown received lengthy briefings to ensure that the image portrayed of Jonestown was positive and convincing.

Although the Temple boasted 20,000 members, it is more likely that California membership peaked at 5,000, with regular attendees totaling between 2,000 and 3,000 (Moore 2009:58). A number of those who left over the years had been members of the upper echelon of Temple leadership, including those responsible for key decision-making, financial and legal planning, and oversight of the organization. They became apostates, that is, public opponents of Peoples Temple (as distinct from individuals who simply abandoned the organization). Among these “defectors” was Tim Stoen, the Temple attorney and Jim Jones’ right-hand man. Stoen gave the fledgling Concerned Relatives group both its star power and organizational acumen, and was key to the success of a public relations campaign designed both to rescue relatives living in Jonestown, and to bring down Jim Jones and Peoples Temple. The Concerned Relatives alleged that Jonestown operated as a concentration camp, and claimed that Jones brainwashed individuals who went to Guyana and held them there against their will (Moore 2009:64-65; see their “Accusation of Human Rights Violations“ published 11 April 1978).

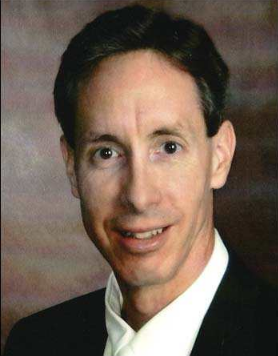

The poster child for the Concerned Relatives (and, coincidentally, for Peoples Temple) was a young boy named John Victor Stoen, [Image at right] the son of Grace Stoen, another apostate. Although Tim Stoen was the putative father, he had signed an affidavit which said that he had encouraged a sexual encounter between his wife and Jim Jones, and that John Victor had been the product of that liaison (Moore 2009:60-61). Tim and Grace joined forces to fight for custody of the boy, and Jones’ vow to hold onto John Victor, even unto death, galvanized the two factions.

As the Stoen custody battled festered, former Temple members Deborah Layton and Yolanda Crawford defected from Jonestown and signed affidavits detailing what they experienced while living there. Family members began contacting the State Department, which in turn directed U.S. Embassy officials in Guyana to visit Jonestown and check on various relatives. In addition to being a party to the John Victor custody case, Tim Stoen filed a number of nuisance lawsuits against the Temple in order to recover money and property for other former members.

The pressure exerted by the Concerned Relatives served to demoralize Jones and the people in Jonestown, and it is clear that Jones’ health and leadership deteriorated significantly. As a result, a leadership corps comprised principally of women ran day-to-day operations in the community (Maaga 1998). At times, Jones became incapacitated through using prescription drugs such as Phenobarbital (Moore 2009:74-75). He would fly into rages, only to calm down moments later. He also had trouble speaking at times, although he also would ramble on for hours well into the night on the community’s public address system, reading news reports from Soviet and Eastern Bloc sources, which presented anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist perspectives highly critical of America. He frequently “portrayed the United States as beset by racial and economic problems” that his followers had escaped by coming to Jonestown (Hall 1987:237). As a result of their long hours in the fields during the day, and their nights punctuated by meetings and harangues over the P.A. system, Jonestown residents became increasingly exhausted and sleep-deprived.

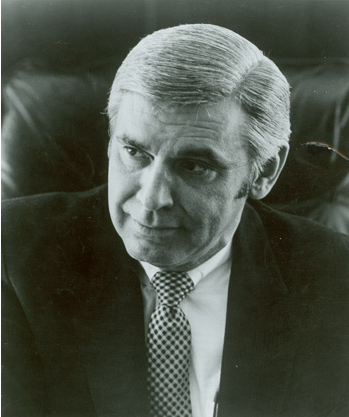

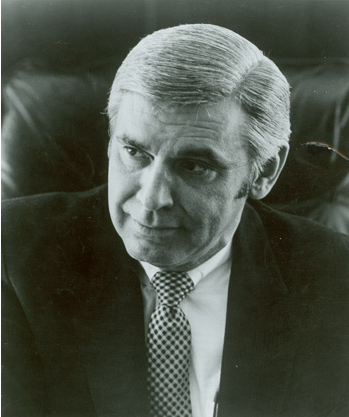

The Concerned Relatives’ letter-writing campaigns to members of Congress finally paid off, and they found an ally in California  Congressman Leo J. Ryan. [Image at right] A constituent, Sammy Houston, claimed that his son Robert had been murdered by Temple members. (There is no evidence to substantiate his claim, which was investigated by the police at the time of Robert’s death, and was re-examined after events in Jonestown.)

Congressman Leo J. Ryan. [Image at right] A constituent, Sammy Houston, claimed that his son Robert had been murdered by Temple members. (There is no evidence to substantiate his claim, which was investigated by the police at the time of Robert’s death, and was re-examined after events in Jonestown.)

Ryan announced his plans to travel to Jonestown in November 1978. The congressman claimed he was conducting a neutral fact-finding mission, but the people of Jonestown did not see it this way. No other members of Congress accompanied Ryan to Guyana, but several members of the Concerned Relatives, along with news reporters who had written critical articles about the Temple did. The party left for Guyana on November 14, 1978 and spent two days in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital (Moore 2009:91). After lengthy negotiations with Jonestown leadership, Ryan, several of the Concerned Relatives, and most of the journalists were allowed to enter the community on November 17 to interview residents, as well as to seek out people allegedly being held against their will. Jones told Ryan that anyone who wished to leave Jonestown was welcome to do so. The day ended with a rousing performance by the Jonestown Express, the community’s band, and with Ryan announcing that Jonestown looked like it was the best thing that had happened to many people. The crowd cheered. That night, however, a disaffected resident slipped a note to both the U.S. Embassy Deputy Chief of Mission and to an NBC News reporter who were present. The note asked for help to get out of Jonestown (Stephenson 2005:118-19).

Ryan and his entourage continued to interview Jonestown residents the next day, but the upbeat mood of the night before had dissipated. As the day progressed, sixteen residents—including members of two long-time Temple families—asked to leave with the Ryan party. The congressman gathered his group together amid considerable strife. As Ryan attempted to leave Jonestown, a resident named Don Sly, the former husband of a Concerned Relative, attacked Ryan with a knife, inflicting superficial cuts on himself but not the congressman (Moore 2009:94). The congressional party made its way in a truck to the airstrip, located six miles from Jonestown in Port Kaituma, the nearest settlement. As they began to board two small planes to take them to Georgetown, a handful of Jonestown residents who had followed the congressman and his party to the airstrip opened fire. Killed in the ambush were Congressman Leo Ryan, three journalists—Robert Brown, Don Harris, and Greg Robinson—and one Peoples Temple member—Patricia Parks, who had wished to leave Jonestown. A dozen members of the media, defecting members, and staff from Ryan’s office were seriously wounded. Two defectors were shot by Larry Layton, who had posed as a defector, and was already aboard one plane when the shooting began outside (Stephenson 2005:120-27).

Back in Jonestown, the residents congregated in the central pavilion. The mood was grim after the defections. Jones proclaimed that the end had come for the people of Jonestown. He said the outside world had forced them to this extreme situation, and that “revolutionary suicide” was their only option. One resident, Christine Miller, dissented, and asked about going to Russia, saying she thought the children should have a chance to live. Other residents shouted her down, however, and the deaths began (Moore 2009:95-96). Parents were the first to give the drink to infants and children; many mothers poured the poison down their children’s throats before they took the poison themselves (Hall 1987:285). Adults then took the poison from a large vat of purple Flav-R-Aid, a British version of Kool-Aid, mixed with potassium cyanide and a variety of sedatives and tranquilizers (including Valium, Penegram, and chloral hydrate) (Hall 1987:282). Some were injected, some drank from a cup, and some had it squirted into their mouths. Although armed guards stood by to prevent anyone from leaving, in the end they also took the poison. Jones, however, died of a gunshot wound to the head: an autopsy could not determine whether his death had been murder or suicide. Despite early reports to the contrary, only one other person died of a gunshot wound, Annie Moore. Sharon Amos, living in the Temple’s house at Lamaha Gardens, in Georgetown, received the order from Jonestown to commit suicide. She killed  her three children and herself in the bathroom of the Georgetown headquarters. The final death toll in Guyana that day was 918: 909 in Jonestown; five at the Port Kaituma airstrip, and four at the Temple’s house in Georgetown. [Image at right]

her three children and herself in the bathroom of the Georgetown headquarters. The final death toll in Guyana that day was 918: 909 in Jonestown; five at the Port Kaituma airstrip, and four at the Temple’s house in Georgetown. [Image at right]

There were about one hundred survivors. Two families and some young adults left early on the morning of the 18th and hiked up the railroad tracks that led to the community of Matthews Ridge, thirty miles away from Jonestown. Three young men were sent out of the area with suitcases full of cash destined for the Soviet Embassy. Two other young men fled as the deaths were occurring, and two elderly people hid in plain sight. Another half dozen were on procurement missions in Venezuela and on boats in the Caribbean. Finally, about eighty Temple members who had been staying in Lamaha Gardens (including members of the Jonestown basketball team) escaped the deaths by virtue of being 150 miles away.

The government of Guyana denied the request of the U.S. State Department to bury  the bodies in Jonestown. A U.S. Army Graves Registration team bagged the remains, which the U.S. Air Force then transported to Dover Air Force Base for identification by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. [Image at right] (Interviews with participants in the bodylift are available at “Military Response to Jonestown” 2020). Routine embalming of all bodies began almost immediately, but one result was that vital forensic evidence was destroyed, which prevented accurate determination of death for seven individuals autopsied by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Relatives claimed approximately one half of the number of bodies, while about 400 bodies remained unidentified or unclaimed. The majority of the unidentified were children. An interfaith group in San Francisco found a cemetery in Oakland, California willing to bury these bodies, after facing rejection by a number of other cemeteries afraid of criticism. In May, 2011 four memorial plaques were placed at the burial site in Evergreen Cemetery, listing the names of all those who died on November 18, 1978.

the bodies in Jonestown. A U.S. Army Graves Registration team bagged the remains, which the U.S. Air Force then transported to Dover Air Force Base for identification by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. [Image at right] (Interviews with participants in the bodylift are available at “Military Response to Jonestown” 2020). Routine embalming of all bodies began almost immediately, but one result was that vital forensic evidence was destroyed, which prevented accurate determination of death for seven individuals autopsied by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. Relatives claimed approximately one half of the number of bodies, while about 400 bodies remained unidentified or unclaimed. The majority of the unidentified were children. An interfaith group in San Francisco found a cemetery in Oakland, California willing to bury these bodies, after facing rejection by a number of other cemeteries afraid of criticism. In May, 2011 four memorial plaques were placed at the burial site in Evergreen Cemetery, listing the names of all those who died on November 18, 1978.

Temple lawyers in San Francisco filed for bankruptcy of the corporation in December 1978, and the San Francisco Superior Court agreed to the dissolution the next month. Judge Ira Brown appointed Robert Fabian to serve as Receiver of the assets, and the local attorney was able to track down more than $8.5 million in banks around the world, in addition to assets traced to San Francisco. Judge Brown ordered all claimants against the Temple to petition the court within four months: 709 claims were made (Moore 1985:344). In May 1980, Fabian proposed a plan to settle the $1.8 billion in claims against the group, by issuing “Receiver’s Certificates” for prorated shares of Temple funds to 403 plaintiffs who had filed wrongful death claims (Moore 1985:351). In November, 1983, a few days before the fifth anniversary of the deaths, Judge Brown signed the order which formally terminated Peoples Temple as a nonprofit corporation. The court had paid out more than $13 million (Moore 1985:354-55).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The belief system of Peoples Temple combined a number of different religious and social ideas, including Pentecostalism, the Christian Social Gospel, socialism, communism, and utopianism. The charisma of Jim Jones and the idealism of Temple members who believed that their vision would create a better world held together this wide-ranging mix of beliefs and practices. Hall calls Peoples Temple an “apocalyptic sect,” which expected the imminent end of the capitalistic world (Hall 1987:40). Wessinger classifies Peoples Temple as a catastrophic millennial group, characterized by a radical dualism that pitted the “Babylon” of the United States against the New Eden of Jonestown (Wessinger 2000:39). All of these views describe the Temple in part.

Jones initially practiced a lively form of Christianity borrowed largely from Pentecostalism. He relied upon the prophetic texts of the Bible to exhort his congregation to work for social justice. An analysis of audiotaped worship services from Peoples Temple in Indiana and California indicates Jones’ debt to Black Church traditions (Harrison 2004). Services followed a free-form style in which music played a key role, the organ emphasizing Jones’ call-and-response style of preaching. His sermons bore themes important to the Black Church: liberation, freedom, justice, and judgment.

The theology of the Temple changed, however, as the role and person of Jim Jones became more exalted. Chidester argues that a coherent theology emerges from Jones’ sermons (Chidester 1988:52). In this theology, Jones asserted that the “Sky God” of  traditional Christianity did not exist, but a genuine God, referred to as Principle or Divine Socialism, did exist in the person of Jim Jones. [Image at right] If God is Love, and Love is Socialism, then humans must live socialistically to participate in God. Moreover, this allowed for personal deification, as Jones quoted John 10:34: “ye all are gods” (Chidester 1988:53). Thus, members of Peoples Temple practiced what they called “apostolic socialism,” that is, the socialism of the early Christian community described in Acts 2:45 and 4:34-35. “No one can privately own the land. No one can privately own the air. It must be held in common. So then, that is love, that is God, Socialism” (Chidester 1988:57, quoting Jones on Tape Q 967).

traditional Christianity did not exist, but a genuine God, referred to as Principle or Divine Socialism, did exist in the person of Jim Jones. [Image at right] If God is Love, and Love is Socialism, then humans must live socialistically to participate in God. Moreover, this allowed for personal deification, as Jones quoted John 10:34: “ye all are gods” (Chidester 1988:53). Thus, members of Peoples Temple practiced what they called “apostolic socialism,” that is, the socialism of the early Christian community described in Acts 2:45 and 4:34-35. “No one can privately own the land. No one can privately own the air. It must be held in common. So then, that is love, that is God, Socialism” (Chidester 1988:57, quoting Jones on Tape Q 967).

As Jones felt more secure in his California base, he exchanged religious rhetoric for political rhetoric more and more. He denounced traditional Christianity and excoriated the Bible, which he referred to as the “Black Book” that had enslaved so many of their forebears. In the early 1970s, he published a twenty-four page booklet titled “The Letter Killeth,” in which he listed all of the contradictions and atrocities contained in the Old and New Testaments. Once the group moved to Guyana, Jones dropped all religious references, except when visitors came (Moore 2009:55). No worship services were conducted in Jonestown. Community planning meetings, news readings, and public events replaced worship. It seems likely, though, that older members retained traditional Christian beliefs (Sawyer 2004).

Although Jones claimed to be a communist, the Communist Party USA had no records of his membership, and disavowed any connection with him after the deaths in Jonestown. Jones made up his communism as he went along, creating an eclectic blend of class consciousness, anti-colonial struggle, selected Marxist ideas, and his perceptions of the community’s needs at the moment. Whatever radical politics he and the group may have shared were somewhat muted, given the fact that they openly supported a variety of Democratic candidates in local, state, and national politics once they relocated to San Francisco. A number of writers have asserted that the Temple helped to elect George Moscone as San Francisco mayor, perhaps even committing fraud to do so, “but the voting clout of actual Temple members in San Francisco seems to have been grossly misperceived” (Hall 1987:166).

Rather than doctrinaire communism, the ideology of Peoples Temple focused on commitment to the community, and to elevating the group above the individual. Members deemed self-sacrifice the highest form of nobility, and selfishness as the lowest of human behavior. In addition, commitment to Jim Jones was required. Loyalty tests ensured commitment to the cause as well as to the leader. No one looked askance at various practices because they made sense within a worldview that anticipated an imminent apocalypse, either through nuclear war or genocide against people of color. By fleeing the United States and attempting to create an alternative society, Temple members believed they might survive this harsh inevitability, perhaps even serving as a new model for humanity. At the same time, though, Jones’ pervasive rhetoric concerning the coming Armageddon undermined any sort of hopeful outlook.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

To promote the shift from the self-centered, elitist individualism promoted by capitalism, Jones encouraged re-training, or indoctrination, in the selfless, populist communalism promoted by socialism through a practice known as “catharsis.” Even in Indianapolis,  “corrective fellowship” meetings were held in which church members offered self-criticism. But catharsis as a regular part of Temple practice took root in Redwood Valley. [Image at right] Catharsis sessions required public confession and communal punishment for transgressions against the community and its members (Moore 2009:32-33). For example, if a teenager was accused of being rude to a senior citizen, the congregation would hear the evidence and vote on the teenager’s innocence or guilt, and on the punishment to be received. The penalty could be a severe spanking administered by one of the seniors. When Jones introduced the “Board of Education,” a one-by-four inch board two and a half feet long, he assigned a large woman to administer the beatings: “She was strong and knew how to whip hard,” according to Mills (1979). Adults who transgressed were punished by being forced to box with other Temple members. A diary kept by Temple member Edith Roller, for example, reported a boxing match between a young man accused of sexism, and a young woman. The woman knocked out the man, to the delight of the crowd in attendance (Moore 2009:32-33).

“corrective fellowship” meetings were held in which church members offered self-criticism. But catharsis as a regular part of Temple practice took root in Redwood Valley. [Image at right] Catharsis sessions required public confession and communal punishment for transgressions against the community and its members (Moore 2009:32-33). For example, if a teenager was accused of being rude to a senior citizen, the congregation would hear the evidence and vote on the teenager’s innocence or guilt, and on the punishment to be received. The penalty could be a severe spanking administered by one of the seniors. When Jones introduced the “Board of Education,” a one-by-four inch board two and a half feet long, he assigned a large woman to administer the beatings: “She was strong and knew how to whip hard,” according to Mills (1979). Adults who transgressed were punished by being forced to box with other Temple members. A diary kept by Temple member Edith Roller, for example, reported a boxing match between a young man accused of sexism, and a young woman. The woman knocked out the man, to the delight of the crowd in attendance (Moore 2009:32-33).

Transgressions revealed in catharsis ranged from selfishness, sexism, and discourtesy to drug or alcohol abuse, and petty crimes for which members could be arrested and convicted by law enforcement. Temple members considered catharsis sessions as a way to improve individual behavior without resorting to authorities like the police or public welfare officials. Mills (1979) claims that members said what they thought Jones wanted to hear, though others apparently believed in the efficacy of catharsis to solve personal and family problems (Moore 1986).

While ritualized catharsis sessions seemed to end with the move to Jonestown, self-criticism and collective condemnation of transgressors continued during Peoples Rallies. These meetings transpired quite frequently in the evenings after the work day. Individuals responsible for various departments, such as the health clinic or the livestock, reported on progress and problems. In addition, individuals would be criticized for decisions that went awry and behavior that seemed self-serving. Family members and partners had a special responsibility to chastise their own.

Peoples Rallies faced inward, addressing the conditions existing in Jonestown. White Nights, on the other hand, looked outward, responding to the threats, real and imagined, that beset the community. A White Night, so-named to counter racist stereotypes (blackmail, blacklist, blackball, etc.), was an emergency drill called by Jones to prepare community members to defend themselves again imminent attack. Some precedent for these drills may have been set when Jones faked an attack upon his person in Redwood Valley (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:201-02). White Nights “signified a severe crisis within Jonestown and the possibility of mass death during, or as a result of, an invasion” (Moore 2009:75). The first one in Jonestown probably occurred in September, 1977, when the lawyer for Tim and Grace Stoen traveled to Guyana to serve court papers upon Jones. Men, women, and children armed themselves with machetes and other farm implements, and stood along the perimeter of the settlement for days, sleeping and eating in shifts. Usually White Nights corresponded to perceived threats, such as when allies in the Guyana government were out of the country. As audiotapes recovered from Jonestown indicate, White Nights usually included discussions of suicide, during which individuals declared their willingness to kill their children, their relatives, and themselves rather than submit to the attackers.

Suicide drills have been conflated with White Nights, but were quite different in that people actually practiced taking what was supposedly poison. These drills, which served as tests of loyalty to the cause, were discussed as early as 1973 when eight young high profile Temple members defected (Mills 1979:231). In 1976 Jones staged a test for members of the Planning Commission, telling them that the wine they had drunk was actually poison to see how they would react (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982:294-96). Piecing together documents from Deborah Layton, Edith Roller, and other accounts, it appears that there were at least six suicide rehearsals in Jonestown in 1978 (Layton 1998; Roller Journal, Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple). Even when suicide was not being rehearsed, it progressively became part of the general conversation more and more, especially during Peoples Rallies (Moore 2006). Individuals also wrote notes to Jones describing assassination and martyrdom plans, such as blowing up the Pentagon or other buildings in Washington, D.C. (Moore 2009:80). Thus, when they were not re-enacting suicide, Temple members were thinking and talking about it.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The Temple had a pyramidal organizational structure, with Jim Jones and a few select leaders at the very tip; a Planning Commission comprising about 100 members near the top; members who lived communally at the next level; and the general rank and file at the base (Moore 2009:35-36). Individuals close to the base of the pyramid did not experience the same levels of coercion, or commitment, as those who had “gone communal” or were further up the pyramid. Even within the Planning Commission, there were a number of inner circles. These included those who helped Jones to fake miraculous healings; those who arranged questionable property transfers; those who practiced dirty tricks (like going through people’s garbage); and those who carried cash to foreign banks.

Despite the rhetoric of racial equality, race and class distinctions continued to exist. According to Maaga, “It was almost impossible for black persons to make their way into positions of influence in the Temple” (Maaga 1998:65). An interracial group of eight young adults defected in 1973, leaving behind a note excoriating the advancement of unproven new white members over time-tested black members:

You said that the revolutionary focal point at present is in the black people. There is no potential in the

white population, according to you. Yet, where is the black leadership, where is the black staff and black attitude? (“Revolutionaries Letter,” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown).

Although some African Americans held leadership positions in Jonestown, the major decision-making power (including planning for mass suicide) remained with whites.

Jones used sex to control Temple members. He arranged marriages, broke up partnerships, and separated families, all in order to make himself the principal object of people’s sexual desire. Encouraging infidelity to one’s partner, Jones demanded fidelity to himself alone, even from the men and women he forced to have sex with him. At the same time, in an effort to create a new, multi-racial society, Jones promoted bi-racial partnerships and the adoption or birth of bi-racial children. A Relationship Committee run by the Planning Commission was established to approve and monitor partnerships between couples.

Jones also accused everyone of being gay; he frequently proclaimed himself to be the only true heterosexual (Hall 1987:112). Harvey Milk, the first openly-gay San Francisco County Supervisor, frequently visited the Temple and was a strong supporter, especially after he received dozens of condolence messages from members following his partner’s suicide. While embracing Milk’s support, Jones also suggested that homosexuality was a problem that did not exist in a true communist society. The Bellefountaines’ examination of the way gays and lesbians were treated within the Temple reveals a contradictory environment of anti-gay rhetoric coupled with an acceptance of gay relationships (Bellefountaine and Bellefountaine 2011).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Given the tragic demise of hundreds of Americans, a number of issues of controversy have arisen. Five major questions seem to recur in popular and scholarly literature: 1) What was the level of violence throughout the course of the Temple’s existence? 2) Was Jonestown a concentration camp? 3) What was the status of Jim Jones’ mental health from earliest childhood until his death? 4) Is it accurate to call the deaths in Jonestown suicide, or was it murder? 5) Did the CIA stage the deaths in Jonestown? Two additional controversies have emerged more recently; 6) the first concerns the debate over whether or not to include Jones’ name on a memorial plaque that listed all those who died on November 18,1978; 7) the other concerns the significance of Jonestown in American life and culture.

1. What was the level of violence in Peoples Temple? It is clear that violence existed inside Peoples Temple at certain moments in its history, ranging from verbal abuse, to corporal punishment, to mental torture, to physical torture. Moore (2011) identified four types of violence that occurred, noting increasingly brutal mistreatment in the final year at Jonestown. The most socially acceptable form of violence consisted of discipline, by which individuals were punished for moral infractions such as lying, stealing, cheating, or social infractions such as smoking or using drugs. The punishment tended to fit the crime: a child who had bitten another, was bitten himself; children who stole cookies from the store were spanked with twenty-five whacks. The next level comprised behavior modification in order to change bourgeois patterns of behavior (racism, sexism, classism, elitism, ageism, and so on). Corporal punishment, such as boxing, or nonviolent penance such as housecleaning or paying fines, tended to be used to deal with these crimes against the group. One of the most extreme forms of behavior modification was the time a pedophilic member was beaten on the penis until it bled (Mills 1979:269).

“While discipline and behavior modification might be considered more or less socially accepted (at least in theory if not in practice), two additional forms of violence existed within the Temple that did not mirror the larger society: behavior control and terror” (Moore 2011:100). Behavior control included separating families, informing on other members (and on one’s own thoughts), regulating sexual activity, and, once in Jonestown, governing all aspects of individual life and thought to the extent possible. Jones inculcated a sense of generalized terror beginning in the 1960s with predictions of nuclear war, and continuing in the 1970s with prophecies of racial genocide, fascist takeover, and terrible torture. Terror became more personal in Jonestown, with people fearing for their lives during White Nights, and with actual incidents of torture, such as punishing a woman by having a snake crawl over her; or, tying two young boys up in the jungle and telling them tigers would get them (Moore 2011:103). Residents believed that enemies were intent upon their destruction, and although this is somewhat true (the Concerned Relatives did indeed intend the annihilation of Jonestown), they were convinced their foes planned kidnappings, torture, and murder. When Leo Ryan announced his visit to Jonestown, the widespread sense of terror only intensified.

2. Was Jonestown a concentration camp? There is broad agreement that conditions in Jonestown, though difficult by middle-class standards, were acceptable, and even agreeable, until late 1977. Reports by U.S. Embassy visitors were generally favorable. U.S. Ambassador Maxwell Krebs described the atmosphere in the small jungle community as “quite relaxed and informal” in 1975. “My impression was of a highly motivated, mainly self-disciplined group, and of an operation which had a good chance of at least initial success” (U.S. Committee on Foreign Affairs 1979:135). By mid-1977, however, an influx of more immigrants than the community could handle created a number of serious problems, especially in the areas of food and housing. Deterioration in living and working conditions, coupled with an intensification in terror, began in 1978, and serious decline occurred in the summer months of that year.

It is true, as the Concerned Relatives charged in their declaration of “Human Rights  Violations,” that incoming and outgoing mail was censored; that travel was restricted; that family members could not visit relatives in Jonestown; and that residents put their best face forward for visitors. [Image at right] Situated in the middle of dense jungle, with only two villages accessible by road (Port Kaituma six miles away and Matthews Ridge 30 miles distant) and connected only by air or river travel to the rest of the world, Jonestown was an encapsulated community, almost completely isolated from contact with outsiders. At the same time, Jonestown did not acquire its totalistic profile apart from the agitation of its “cultural opponents” (Hall 1995). As Hall observes, anticult activists played a role in the outcomes in Jonestown and at Mt. Carmel. In their article that analyzes the endogenous (internal) factors leading to violence in new religious movements and the exogenous (external) factors, Anthony, Robbins, and Barrie-Anthony (2011) describe a “toxic interdependence” of “anticult and cult violence,” and suggest that “some groups may be so highly totalistic that they are very vulnerable to [a] triggering effect,” that is, acting out totalistic projections from the outside world (2011:82). In other words, conditions in Jonestown may have declined in response to the level of threat residents believed to exist.

Violations,” that incoming and outgoing mail was censored; that travel was restricted; that family members could not visit relatives in Jonestown; and that residents put their best face forward for visitors. [Image at right] Situated in the middle of dense jungle, with only two villages accessible by road (Port Kaituma six miles away and Matthews Ridge 30 miles distant) and connected only by air or river travel to the rest of the world, Jonestown was an encapsulated community, almost completely isolated from contact with outsiders. At the same time, Jonestown did not acquire its totalistic profile apart from the agitation of its “cultural opponents” (Hall 1995). As Hall observes, anticult activists played a role in the outcomes in Jonestown and at Mt. Carmel. In their article that analyzes the endogenous (internal) factors leading to violence in new religious movements and the exogenous (external) factors, Anthony, Robbins, and Barrie-Anthony (2011) describe a “toxic interdependence” of “anticult and cult violence,” and suggest that “some groups may be so highly totalistic that they are very vulnerable to [a] triggering effect,” that is, acting out totalistic projections from the outside world (2011:82). In other words, conditions in Jonestown may have declined in response to the level of threat residents believed to exist.

3. What was the status of Jim Jones’ mental health? The introduction to Rosenbaum’s Explaining Hitler (1998) presents an overview of his analysis of the many attempts to understand how Adolf Hitler came to be who and what he was. The subtitle, The Search for the Origins of His Evil, could equally describe a number of popular and scholarly works about Jim Jones. Rosenbaum’s catalog of explanations (mountebank, true believer, mesmeric occult messiah, scapegoat, criminal, abused child, “Great Man,” and victim, among others) can be and have been applied to Jones. Accounts range from Jones being crazy and evil from his youth (Reiterman and Jacobs 1982, Scheeres 2011); that his “herculean conscience” to do good ultimately overwhelmed him (Rose 1979); that “audience corruption” deluded him into believing his own rhetoric (Smith 2004); and other evaluations.

It is clear that Jones was charismatic, manipulative, sensitive, and egocentric. Not as clear is the extent of his abilities as a faith healer. One thing that many Jonestown survivors and former Temple members agree on is that Jones had paranormal abilities. Although sham faith healings occurred in the San Francisco Temple, even some critics of those healings admit that on occasion the healings were genuine (compare Beck 2005 and Cartmell 2006).

Equally clear is that Jones began using barbiturates in San Francisco, and possibly earlier, to manage his schedule. His long-term drug abuse became apparent in Jonestown. U.S. Embassy officials visiting 7 November 1978 noted that his speech was “markedly slurred” and that he seemed mentally impaired (U.S. Committee on Foreign Affairs 1979:143). Audiotapes made in Jonestown confirm Jones’ mental and speech deficiencies. His autopsy revealed toxic levels of pentobarbital in his liver and kidneys, thus indicating a drug addiction (“Autopsies” 1979).

4. Were the deaths in Jonestown suicide or murder? The question of whether or not residents of Jonestown voluntarily committed suicide, or whether they were coerced, and therefore murdered, continues in lively online debates (“Was It Murder or Suicide?” 2006). Evidence from the audiotape made 18 November (Q 042) as well as eyewitness accounts indicate that parents killed their children; even if youngsters voluntarily drank the poison, the 304 children and minors under age eighteen are considered murder victims. Some senior citizens were found dead in their beds, evidently injected, and these individuals were also murdered. Debate centers on the able-bodied adults, and if they actually chose to die or if they were physically coerced by members of the Jonestown security team. After a brief inspection of the scene, Dr. Leslie Mootoo, the chief pathologist for the government of Guyana, reported seeing syringes without needles, presumably to insert poison into the mouths of children or unwilling adults. He also stated that he saw needle puncture marks on the backs of eighty-three out of 100 individuals he examined (Moore 2018a). Yet according to Odell Rhodes, an eyewitness, most people died “more or less willingly” and Grover Davis, who watched the suicides before deciding to hide himself in a ditch, said “I didn’t hear nobody say they wasn’t willing to take suicide shots… They were willing to do it” (Moore 1985:331). No one rushed the vat, according to Skip Roberts, the Assistant Police Commissioner for Crime in Guyana investigating the deaths, “because they wanted to die. The guards weren’t even necessary at the end” (Moore 1985:333).

Members of Peoples Temple had long been conditioned to accept the necessity of giving their lives for the cause of justice and freedom. African Americans living in the 1960s and 1970s saw the ranks of political activists decimated in the violent deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and the leaders of the Black Panther Party. The Panthers’ Huey Newton had observed that activism required a commitment to “revolutionary suicide,” that is, a willingness to put one’s life on the line because radical politics in the 1970s were suicidal. Although Jones appropriated Newton’s language, he altered the concept in a significant way. Newton argued that revolutionary activism, by definition, leads to conflict with the state, and that the state eventually kills its opponents in defense of itself and its institutions. Jones interpreted “revolutionary suicide” more literally, meaning that one must kill oneself in order to advance the revolution (Harris and Waterman 2004).

The rhetoric of suicide is evident in many Temple documents. Programs at the Temple in San Francisco and issues of the group’s newspaper, Peoples Forum, focused on the ever-present reality of torture and death. Letters and notes written to Jones and to family members expressed a willingness to die for their beliefs. Audiotapes affirm these revolutionary vows to commit suicide. The Concerned Relatives pointed out that one Jonestown resident wrote in April 1978 that the group would rather die than be hounded from one continent to the next (Moton 1978). Further reports of suicide drills came from Yolanda Crawford that April and from Deborah Layton in June.

Although residents of Jonestown took the rhetoric of suicide seriously, it would be a mistake to conclude that, on the last day, they believed they were participating in simply another drill. The defections of long-time members had sobered the community, and with the news of the deaths at the airstrip, they understood that the end of their communal experiment was in sight. The vehemence with which Christine Miller argued against suicide indicates that she took the plan seriously. And when the first persons taking the poison died, it was immediately clear that this was the real thing. If parents did indeed poison their own children first, it seems likely that they intended to poison themselves as well. They had believed that their children would be tortured by government forces in the wake of Ryan’s assassination; they saw the end of the Promised Land with the invasion of Ryan and their enemies; they had practiced taking the poison; and they believed that loyalty to each other and to their cause required death. Nevertheless, questions remain, and, as Bellefountaine writes, “When confronted with the question of whether the deaths in Jonestown should be classified as murders or suicides, most people feel comfortable joining the two words into a phrase that covers both options [murders-suicides]. But it doesn’t quite fit” (Bellefountaine 2006).

5. Was Jonestown the result of a government conspiracy? A number of conspiracy theories have arisen concerning the deaths in Jonestown because of conflicting accounts of the deaths, inconsistencies in news accounts, and the demise of other groups that shared the Temple’s radical politics. The earliest report of the deaths came from the Central Intelligence Agency, in a message communicated over an intelligence communications network (“The NOIWON Notation” 1978). This, coupled with the fact that Richard Dwyer, the Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in Georgetown, was probably working for the CIA, as was U.S. Ambassador John Burke, has served as fuel for a large number of conspiracy theories in both print and electronic forms (Moore 2005). Some claim that Jim Jones was a rogue CIA agent who was involved in a mind control experiment. Others assert that the United States government killed all of the inhabitants of Jonestown because it feared the propaganda victory for the Soviet Union if it did indeed become the new home for Peoples Temple. Still others argue that Jonestown represented a right wing conspiracy to execute genocide on black Americans (Helander 2020). None of these theories are considered here because, to date, no evidence beyond conjecture and speculation has been presented. Psychological analyses that rely on assumptions of brainwashing or coercive persuasion also fail to adequately address what happened and why. Theories of the all-powerful cult leader, able to turn sensible people into mindless zombies, collapse when we listen to the community’s conversations captured on Jonestown’s audiotapes and to the discussions that former members of Peoples Temple still have about their experiences within the movement.

6. Should Jim Jones’ name be on a Jonestown memorial? The Rev. Jynona Norwood, an African American pastor from Los Angeles, whose mother, aunt, and cousins died in Jonestown, has conducted a memorial service at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California [Image at right] every November 18 since 1979. Norwood raised money to construct a memorial on the site, and in 2008 unveiled two enormous granite blocks with the names of some, but not all, adults who had died in Jonestown. According to Ron Haulman, manager of the cemetery, however, the fragile hillside could not support the size or weight of the monuments (Haulman 2011). In 2010, frustrated with the slow pace of the memorialization process, three relatives of Jonestown victims (Jim Jones Jr., John Cobb, and Fielding McGehee) created the Jonestown Memorial Fund and signed a contract with Evergreen Cemetery, agreeing to create a monument consistent with environmental constraints at the hillside (McGehee 2011). In 2011 the three raised $20,000 in three weeks from 120 former Temple members, relatives, scholars, and others. In May 2011, Norwood sued to halt installation of the memorial, claiming that she had a prior claim with the cemetery. The court ruled against her, given that by the time of her suit, the new memorial (four granite plaques that list the names of all who died) was already in place.

whose mother, aunt, and cousins died in Jonestown, has conducted a memorial service at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California [Image at right] every November 18 since 1979. Norwood raised money to construct a memorial on the site, and in 2008 unveiled two enormous granite blocks with the names of some, but not all, adults who had died in Jonestown. According to Ron Haulman, manager of the cemetery, however, the fragile hillside could not support the size or weight of the monuments (Haulman 2011). In 2010, frustrated with the slow pace of the memorialization process, three relatives of Jonestown victims (Jim Jones Jr., John Cobb, and Fielding McGehee) created the Jonestown Memorial Fund and signed a contract with Evergreen Cemetery, agreeing to create a monument consistent with environmental constraints at the hillside (McGehee 2011). In 2011 the three raised $20,000 in three weeks from 120 former Temple members, relatives, scholars, and others. In May 2011, Norwood sued to halt installation of the memorial, claiming that she had a prior claim with the cemetery. The court ruled against her, given that by the time of her suit, the new memorial (four granite plaques that list the names of all who died) was already in place.

In addition to the claims of priority, Norwood objected to the inclusion of Jim Jones in the listing of names. Though aware of opposition and concern about including Jones’ name on the monument, the organizers of the Jonestown Memorial Fund nevertheless argued that the four-by-eight stones serve as an historical marker of the deaths of all who died on November 18, 1978. For this reason, Jim Jones’ name appears, listed alphabetically among all of the other persons named “Jones” who died that day.

7. What are the lessons of Jonestown? Jonestown and Jim Jones have entered American discourse as code for the perils of cults and cult leaders (Moore 2018b). In the conflict between anticultists and members of new religions in the 1980s, parents, deprogrammers, exit counselors, and psychiatrists pointed to Jonestown as the paradigm for all that could go wrong with unconventional religions (Shupe, Bromley, and Breschel 1989). As these authors wrote, “There was inestimable symbolic value for a countermovement in an event such as Jonestown” (1989:163-66). More than thirty years after the event, Jonestown and Jim Jones continue to symbolize evil, danger, and madness. Those who survived, however, consider it a failed experiment that had its strength in members’ commitment to racial equality and social justice.

In addition, the expression “drinking the Kool-Aid” has found a permanent place in American lexicon (Moore 2003). It is paradoxically used to mean either blindly jumping on the bandwagon, or being a team player, and finds its most frequent usage in the contexts of sports, business, and politics. As is the case with many idiomatic phrases, most of the people who now use the expression are too young to remember its origins in the events of Jonestown. Surviving members of Peoples Temple are horrified and offended by the expression, and the way it trivializes those who died (Carter 2003).

Debate about these and other issues continues, and will undoubtedly continue given the shocking nature of the deaths. [Image at right] Moreover, the fact that hundreds, if not thousands, of government documents still remain classified, suggests that the final story is yet to be written. These files may lend credence to conspiracy theories by exposing the extent of government foreknowledge of the deaths in Jonestown. Alternatively, the information they provide may not do much more than add details to parts of the story that remain vague. Whatever these documents reveal, the story will always remain incomplete and contested, and researchers present and future will continue to wrestle with the enigma that remains Jonestown.

IMAGES

Image #1: Jim Jones speaking from the pulpit of sanctuary in San Francisco, 1976. Photo courtesy The Jonestown Institute.

Image # 2: Peoples Temple Full Gospel Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Photo courtesy Duane M. Green, 2012, The Jonestown Institute..

Image # 3: Jonestown pioneers visited by Jim Jones, 1974. Photo courtesy Doxsee Phares Collection, The Jonestown Institute.

Image #4: Aerial shot of Jonestown, 1978. Photo courtesy The Jonestown Institute.

Image # 5: John Victor Stoen, the object of a custody battle between Jim Jones and Grace and Timothy Stoen. Photo courtesy California Historical Society.

Image #6: Congressman Leo J. Ryan, who was assassinated on 18 November 1978 by residents of Jonestown. Four other people died in the attack. Photo courtesy California Historical Society.

Image #7: Aerial view of Jonestown with bodies somewhat visible. Photo courtesy The Jonestown Institute.

Image #8: U.S. military personnel engaged in gathering remains in Jonestown. Photo courtesy Preston Jones, John Brown University.

Image # 9: Idealized portrait of Jim Jones standing with children of different races. This was considered the “Rainbow Family,” a goal of Peoples Temple members. Photo courtesy The Jonestown Institute.

Image #10: Children and teenagers enter the sanctuary of San Francisco church, 1974. Photo courtesy The Jonestown Institute.

Image # 11: Agricultural worker in Jonestown. Photo courtesy California Historical Society.

Image #12: Four granite plaques installed at Evergreen Cemetery in Oakland, California, in 2011. There was controversy about including the name of Jim Jones on the plaques. Photo courtesy John Cobb and Regina Hamilton.

Image #13: The road to Jonestown in 2018. Photo courtesy Rikke Wettendorf.

REFERENCES

Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu on 4 June 2012.

Anthony, Dick, Thomas Robbins, and Steven Barrie-Anthony. 2011. “Reciprocal Totalism: The Toxic Interdependence of Anticult and Cult Violence.” Pp. 63-92 in Violence and New Religious Movements, edited by James R. Lewis. New York: Oxford University Press.

“Autopsies.” 1979. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/JimJones.pdf on 4 June 2012.

Beck, Don. 2005. “The Healings of Jim Jones.” The Jonestown Report 7. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=32369 on 7 November 2014.

Bellefountaine, Michael. 2006. “The Limits of Language.” The Jonestown Report 8. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31975 on 7 November 2014.

Bellefountaine, Michael, with Dora Bellefountaine. 2011. A Lavender Look at the Temple: A Gay Perspective of the Peoples Temple. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Carter, Mike. 2003. “Drinking the Kool-Aid.” The Jonestown Report, August 5. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=16987 on 7 May 2021.

Cartmell, Mike. 2006. “ Temple Healings; Magical Thinking.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31911 on 4 June 2012.

Chidester, David. 1988 (reissued 2004). Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Concerned Relatives. 1978. “Accusation of Human Rights Violations made by Concerned Relatives, 11 April 1978. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13080 on 7 November 2014.

Hall, John R. 1995. “Public Narratives and the Apocalyptic Sect: From Jonestown to Mt. Carmel.” Pp. 205-35 in Armageddon in Waco: Critical Perspectives on the Branch Davidian Conflict, edited by Stuart A. Wright. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hall, John R. 1987 (reissued 2004). Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

Harrison, F. Milmon. 2004. “Jim Jones and Black Worship Traditions.” Pp. 123-38 in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary Sawyer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Haulman, Ronald. 2011. “Declaration of Ronald Haulman in Opposition to Application for a Temporary Restraining Order.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Norwood5a.pdf on 4 June 2012.

Helander, Henri. 2020. “Alternative History (Conspiracy) Theory Index.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=95357 on 12 March 2020.

Layton, Deborah. 1998. Seductive Poison: A Jonestown Survivor’s Story of Life and Death in the Peoples Temple. New York: Anchor Books.

Levi, Ken. 1982. Violence and Religious Commitment: Implications of Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple Movement. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Maaga, McCormick Mary. 1998. Hearing the Voices of Jonestown. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

McGehee, Fielding M. III. 2011. “The Campaign for a New Memorial: A Brief History.” The Jonestown Report 11. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=34364 on 7 November 2014.

“Military Response to Jonestown.” 2020. Siloam Springs, AR: John Brown University, at https://www.militaryresponsetojonestown.com/ on 20 March 2020.

Mills, Jeannie. 1979. Six Years With God: Life Inside Rev. Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple. New York: A & W Publishers.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018a. “Examinations by Dr. Leslie Mootoo.” Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=83848 on 12 March 2020.

Moore, Rebecca. 2018b. “Godwin’s Law and Jones’ Corollary: The Problem of Using Extremes to Make Predictions.” Nova Religio 22:145–54.

Moore, Rebecca. 2011. “Narratives of Persecution, Suffering, and Martyrdom: Violence in Peoples Temple and Jonestown.” Pp. 95-11 in Violence and New Religious Movements, edited by James R. Lewis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moore, Rebecca. 2009 [2018]. Understanding Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Moore, Rebecca. 2006. “The Sacrament of Suicide.” The Jonestown Report 8. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31985 on 7 November 2014.

Moore, Rebecca. 2005. “Reconstructing Reality: Conspiracy Theories About Jonestown.” Pp. 61-78 in Controversial New Religions, edited by James R. Lewis and Jesper Aagaard Petersen. New York: Oxford University Press. Also available at http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=16582.

Moore, Rebecca. 2003. “Drinking the Kool-Aid: The Cultural Transformation of a Tragedy.” Nova Religio 7: 92-100. Also available at http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=16584.

Moore, Rebecca. 1986. The Jonestown Letters: Correspondence of the Moore Family 1970-1985. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Moore, Rebecca. 1985. A Sympathetic History of Jonestown: The Moore Family Involvement in Peoples Temple. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Moton, Pam. 1978. “Exhibit A to Concerned Relatives Accusation of 11 April 1978, Letter to Members of Congress, 14 March 1978.“ Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13084 on 4 June 2012.

“The NOIWON Notation.” 1978. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13678 on 4 June 2012.

Reiterman, Tim, with John Jacobs. 1982. Raven: The Untold Story of The Rev. Jim Jones and His People. New York: E.P. Dutton.

Roller, Edith. “Journals.” Alternative Consideration of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=35667 on 4 June 2012.

Rose, Steve. 1979. Jesus and Jim Jones: Behind Jonestown. New York: Pilgrim Press.

Rosenbaum, Ron. 1998. Explaining Hitler: The Search for the Origins of His Evil. New York: Random House.

Sawyer, R. Mary. 2004. “The Church in Peoples Temple.” Pp. 166-93 in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary Sawyer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Scheeres, Julia. 2011. A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception, and Survival at Jonestown. New York: Free Press.

Shupe, Anson, David Bromley, and Edward Breschel. 1989. “The Peoples Temple, the Apocalypse at Jonestown, and the Anti-Cult Movement.” Pp. 153-71 in New Religious Movements, Mass Suicide, and Peoples Temple: Scholarly Perspectives on a Tragedy, edited by Rebecca Moore and Fielding McGehee III. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

Smith, Archie Jr. 2004. “An Interpretation of Peoples Temple and Jonestown: Implications for the Black Church.” Pp. 47-56 in Peoples Temple and Black Religion in America, edited by Rebecca Moore, Anthony B. Pinn, and Mary Sawyer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Stephenson, Denice, ed. 2005. Dear People: Remembering Jonestown. San Francisco and Berkeley: California Historical Society Press and Heyday Books.

U.S. Committee on Foreign Affairs. 1979. “The Assassination of Representative Leo J. Ryan and the Jonestown, Guyana Tragedy.” U.S. House of Representatives, 96th Congress, First Session. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

“Was It Murder or Suicide?” 2006. The Jonestown Report 8. Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=31981 on 7 November 2014.

Wessinger, Catherine. 2000. How the Millennium Comes Violently. New York: Seven Bridges Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple is a comprehensive digital library of primary source literature, first-person accounts, and scholarly analyses. It currently provides live streaming of more than 925 audiotapes made by the group during its twenty-five year existence, as well as photographs taken by group members. Approximately 500 tapes are currently available online, along with transcripts and summaries. Founded in 1998 at the University of North Dakota to coincide with the twentieth anniversary of the deaths in Jonestown, the website moved to San Diego State University in 1999, where it has been housed ever since at. The SDSU Library and Special Collections currently manages Alternative Considerations, one of the largest digital archives of a new religion in existence. The site memorializes those who died in the tragedy; documents the numerous government investigations into Peoples Temple and Jonestown (such as more than 70,000 pages from the FBI, including records from its investigation as well as its collection of Temple documents, and 5,000 from the U.S. State Department); and presents Peoples Temple and its members in their own words through articles, tapes, letters, photographs and other items. The site also conveys ongoing news regarding research and events relating to the group.

Bibliography and Audiotape Resources:

A comprehensive bibliography of resources on Peoples Temple and Jonestown can be found here.

Audiotapes recovered in Jonestown, 300 of which are streaming live, can be found here: http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=27280

Items Referenced in the profile: The following items, referenced in the above article, can be found on the Alternative Considerations website.

Lease signed between Government of Guyana and Peoples Temple, February 25, 1976. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13131.

Affidavit signed by Tim Stoen stating that Jim Jones was the father of John Victor Stoen, February 6, 1972. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=13836

Transcript and audiostreaming of Tape Q 042 (the so-called Death Tape), made November 18, 1978. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=29084.

Text of “The Letter Killeth.” http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14111

Text of the “Gang of Eight Letter.” http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=14075.

Publication Date:

22 June 2012

Update: 9 May 2021

(Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America.

(Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America. resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join.

resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join. so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority.

so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority. challenge. Secondary to this was the provision of nutritious food. Twenty-something Shiloh leaders found themselves thrust into the role of caring for large numbers of people. In response, Shiloh developed its Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book with recipes for five, 25, and 50 servings, organized dumpster diving and produce runs to recycle food, applied for USDA surplus food, and planted community gardens. Following a “prophetic” understanding that “agriculture was to be the foundation of the ministry,” Shiloh purchased an orchard, pastures, a goat dairy and livestock; leased a commercial berry farm; ran a commercial fishing boat; and developed a cannery to provide both income and food to distribute throughout its communal system.