SHILOH YOUTH REVIVAL CENTERS TIMELINE

1968 The first “House of Miracles” in Costa Mesa, California was sponsored by Calvary Chapel.

1969 All Houses of Miracles “submitted” to John J. Higgins, Jr., Randy Morich, and Chuck Smith as “elders.”

1970 The Houses of Miracles moved to Oregon and took the name “ Shiloh” at the invitation of “Open Bible Standard” pastors.

1970 Rev. Wonleey Gray (OBS Pastor) gave the corporate shell of “ Oregon Youth Revival Center” to Shiloh.

1970 Shiloh bought 70 acres near Dexter, Oregon (“the Land”) to build a central commune and Bible school (the “ Shiloh Study Center”).

1971 The first communal Pastors’ Meeting was held at “the Land.”

1971 Shiloh began its “Agricultural Foundation of Ministry,” eventually buying or leasing five farms in Oregon; sociologists from University of Nevada, Reno began to study Shiloh.

1971-1978 Shiloh sent out numerous teams across U.S., U.S. territories, and Canada to open “Shiloh Houses” and “Fellowships;” members moved between the Shiloh Study Center, work parties, and evangelical teams, who made new communal “foundations.”

1974 Shiloh centralized its resources to allow for central planning and control under the rubric of “one communal pot” and began to give “personal allocations” based on rank.

1975 Shiloh abandoned full communitarianism (“one pot”) in the face of the growth of its married population and started “fellowships” (churches) for marrieds.

1978 The Study Center/Work/Team cycle was suspended; ministry “Bishop,” John J. Higgins, Jr. was suspended and fired by the Shiloh Board of Directors; members began a mass out-movement from the 37 communes open at this time. Higgins moved to Arizona to start Calvary Chapels.

1978-1982 Ken Ortize presided over the retrenchment of Shiloh to “the Land” alone. He left to start a Calvary Chapel in Spokane, Washington.

1982-1987 Joe Peterson, leader of House of Elijah in Yakima, Washington, was invited to lead Shiloh and make “the Land” a retreat center.

1986 The Internal Revenue Service sued Shiloh for unpaid “Unrelated Business Income Tax” due for income earned by Shiloh treeplanting work teams.

1987 The “Last Reunion” of Shiloh members was held on “the Land.”

1989 “Shiloh Youth Revival Centers” disincorporated.

1993 Lonnie Frisbee, one of Shiloh’s original leaders, died from complications after contracting AIDS.

1998 The “Shiloh ‘Twentieth’ Reunion” was held in Eugene, Oregon.

2002 Keith Kramis and others created Shiloh websites and discussion forums as virtual spaces for those in the Shiloh diaspora.

2010 Shiloh appeared on Facebook.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

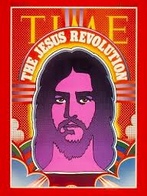

The North American Jesus Movement of the late 1960’s through early 1980’s spawned a host of religious movement organizations (Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America.

(Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America.

Shiloh passed through seven major periods in its organizational history and “afterlife” (Stewart and Richardson 1999a).

The House of Miracles phase began on May 17, 1969 when John J. Higgins, Jr. (b. April 1939 in Queens, New York and raised Roman Catholic) and his wife, Jacquelyn, founded the House of Miracles in Costa Mesa, California (Higgins 1973). For the prior two years they had been members of Calvary Chapel of Costa Mesa under the pastorship of Chuck Smith, a former Foursquare Gospel minister. Calvary Chapel gave partial financial support to this first step (Higgins 1973).

When Higgins moved with a team of communards to Lane County, Oregon in the spring of 1969, he initiated a process that  resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join.

resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join.

In 1974, all Shiloh communes became part of a centralized planned economy. During this time Higgins de-emphasized charisma and moved millenarian views onto center stage. Centralizing funds allowed Shiloh to form work teams, to bid on reforestation and other mass-work contracts, support a school operation, and to send out evangelistic teams all over the U.S., from Fairbanks to Boston and from Maui to the Virgin Islands. As individuals married and moved out of the communes during the following period, Shiloh Fellowship churches were organized along the lines of a Franciscan “third order.”

However, in the spring of 1978 Shiloh’s Board, made up primarily of old House of Miracles’ house pastors and some second generation leaders, impeached and fired its surviving charismatic founder. The movement entered a period of chaos, retrenchment, and eventual collapse as trust fractured. Several successor groups operated “rump” communes or publications, founded Calvary Chapels, or later, Vineyard Christian Fellowships. Some worked as evangelists and church planters in Latin America, Southeast Asia, and the former Soviet Union.

Circa 1982, one remnant group developed new purpose in maintaining the central Shiloh commune in Dexter, Oregon, as a retreat center. This group invited Joe Peterson, a former “House of Elijah” ( Yakima, Washington) leader, to take the helm. In 1986, Shiloh was sued by the Internal Revenue Service for failure to pay taxes on unrelated business enterprises, a suit that eventually was lost. The beloved “Land” was forfeited to the tax attorneys in lieu of fees. Shiloh disincorporated in 1989.

Though the corporate shell was gone, all the people had gone “somewhere.” They had become church members and leaders of all denominational stripes, joined missionary organizations, or deconverted and become Buddhists, agnostics, and atheists. Many played significant leadership roles in the Calvary Chapel and Vineyard movements. Among them was Lonnie Frisbee, Shiloh’s most famous member and early leader, who died of AIDS in 1993. Some earned advanced degrees, studying and writing about what happened to them (e.g., Murphy 1996; Peterson 1990, 1996; Stewart 1992; Stewart and Richardson 1999a; Taslimi et al. 1991).

As they had time to process their own histories with Shiloh, Shiloh’s “afterlife” blossomed from nostalgia. Former communards organized major reunions (e.g., 1987, 1998, and 2010) and many localized ones, initiated electronic discussion lists, and set-up web sites (Kramis 2002-2013). Shiloh members labeled the first and second phases “Old Shiloh,” the third “New Shiloh,” thought of the fourth as a metaphorical “holocaust,” and denied the existence of subsequent periods. Shiloh’s “twentieth reunion” in 1998 marked the time from Higgins’s fall—a more significant event for Shiloh alumni than the founding (1968) or disincorporation (1989). This reunion also marked an effort by reunion organizers and several former Shiloh Board Members (now pastors of Calvary Chapels) to rehabilitate Higgins’ reputation, an effort that continued through subsequent reunions.

The advent of Shiloh on Facebook in 2010 allowed Shiloh alumni (or “Shilohs” as they call themselves) from all eras and locales to discover one another. Some had never understood what had happened in 1978 and sought to know the details of their own history. Others took occasion to share their old photos and wistful memories.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Shiloh ’s beliefs would coordinate well with the “Statement of Faith” for the National Association of Evangelicals. Shiloh, especially at its beginning, was Charismatic/Pentecostal in practice. However, Shiloh members ran into trouble with both Evangelicals and Pentecostals because the group permitted its hippie male members to wear long hair (a “shame” as per 1 Cor. 11:14) and held all property in common (Acts 2:44-45). Starting with the first “submission” to Higgins in 1969 and continuing with the annual pastors’ meeting from 1971 on, “Shilohs” pledged commitment to Shiloh and its elders in annual commitment meetings. This included giving property (“laying it at the apostles’ feet,” Acts 4:34-35), wages, and the like to the group. A. T. Pierson’s biography of George Muller (2008), a member of the Plymouth Brethren and orphanage founder, influenced Shiloh to depend on prayer for financial provision. Gifts from members were seen as a result.

Besides the acknowledging and privileging of charismatic gifts and total commitment to the cause, evangelical writers such as A.W. Tozer in his Knowledge of the Holy (1992) and last-day prophets such as Chuck Smith in his studies of biblical eschatology (e.g., pre-tribulation rapture; soon-coming of Christ) contributed to Shiloh’s nascent theology. During the period when Higgins consolidated his leadership (1972-1978), he de-emphasized “other voices” while stressing his own particular teaching. Among the new teachings was one based on Ecclesiastes 11:3, “where a tree falls that’s where it lies” (per a Shiloh paraphrase). At the time this meant that anyone sinning in thought, word, or deed at the (precise) moment of death would receive eternal punishment. (This teaching was later nicknamed “eternal insecurity”). Such an assertion was a giant step away from Calvary Chapel’s “Calminianism—a calque for Calvinism + Arminianism, i.e. a middle-of-the-road posture between the predestination of the believer to “salvation” and the freewill of the believer to choose and maintain “salvation.” A second novelty, concerning “the synagogue of Satan” (Rev 2:9; 3:9), proved controversial with movement leaders, setting the stage for the crisis of 1978.

Communal life lead to a large number of rules to ease the friction of life together. For instance, sanitary pit-privies would have a sign reminding members to toss in a scoop of agricultural lime after each use adding, “He who is faithful in little will be faithful in much” (a Shiloh paraphrase of Matt 25:21). This notion, along with the doctrine of “salvation-insecurity” above, provided a way for members “to exhort” or exercise their spiritual authority over each other. The urgency felt for the Second Coming combined with the fear of sin’s eternal consequences for an ill-timed lapse bolstered Shilonites’ submission to leaders, compliance to rules, and “commitment.” Shiloh was a “high-commitment” organization. As one member said: “Some went to Vietnam; we went to Shiloh.”

During the Vietnam War, Shiloh allowed the exercise of personal conscience as to whether one should submit to the draft or not. Consequently, some “Shilohs” sought the draft status of “conscientious objector,” making use of counseling materials prepared by the Mennonite Central Committee. In 1970, one Shiloh leader refused induction into the military and went to prison for five months. However, this early commitment to a peace position did not survive the decade.

Shiloh ’s “legalism” and rejection of “the security of the believer” was the inverse image of the classic Christian notion of “grace.” Young leaders (teenagers and twenty-somethings; Higgins in his thirties) struggled with their confusion about this (Higgins 1974a). It did not come under active theological discussion until late in the “New Shiloh” period. Indeed, all of Shiloh’s theology remained in process. Chuck Smith’s influence on Higgins did lead to an annual Bible reading program led by house pastors in “twenty-chapter studies.” The “whole” Bible, implicitly, was given authority by this read-through and its reading contributed to continuing theological development. “Shilohs” paraphrased and reified the King James Bible in speech, song, letters, publications, performances, and arts and crafts (Stewart 1992).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Shiloh moved from a quasi-democratic, communalist, and egalitarian movement, exemplified by free display of charismata by any so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority.

so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority.

All of the original leaders claimed prophetic authority from visions and auditions (Higgins 1974b). Higgins, for instance, claimed that the name of the organization, Shiloh, came to him by prophecy and was based on Genesis 49:10. But by 1978 the leadership was fully hierarchical: Higgins as “Bishop” at the top; the Pastors’ Council of elders in the second rank; House pastors and patronesses, third. Women could not teach men and wives were to submit to husbands. Shiloh adopted the New Testament “Household Codes” (e.g., Ephesians 5:22-6:9) to manage its social relations. However, Shiloh did allow women to hold the offices of Exhorter, Deaconess and Patroness (the latter was conceptualized as women’s ordination, and these women typically pastored “Girl’s Houses”) in a parallel structure with men’s roles. This move evidenced a slight accommodation to the birthing feminist movement in the 1970s. In 1977, Jo Ann Brozovich, became editor of Shiloh Magazine , leading a mixed gender staff. Nevertheless, all members were to “submit” to those “above” them.

The twelve member Pastors’ Council, with no women present except a stenographer, met weekly to run things under Higgins’ aegis. These second “generation” leaders included five early House of Miracles pastors, some teachers from the Shiloh Study Center (including Ken Ortize who would take over the retrenching Shiloh in 1978), and some leaders of technical departments.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

For the early Shiloh movement, management of the hordes of nomadic youth who sought shelter represented the primary

challenge. Secondary to this was the provision of nutritious food. Twenty-something Shiloh leaders found themselves thrust into the role of caring for large numbers of people. In response, Shiloh developed its Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book with recipes for five, 25, and 50 servings, organized dumpster diving and produce runs to recycle food, applied for USDA surplus food, and planted community gardens. Following a “prophetic” understanding that “agriculture was to be the foundation of the ministry,” Shiloh purchased an orchard, pastures, a goat dairy and livestock; leased a commercial berry farm; ran a commercial fishing boat; and developed a cannery to provide both income and food to distribute throughout its communal system.

challenge. Secondary to this was the provision of nutritious food. Twenty-something Shiloh leaders found themselves thrust into the role of caring for large numbers of people. In response, Shiloh developed its Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book with recipes for five, 25, and 50 servings, organized dumpster diving and produce runs to recycle food, applied for USDA surplus food, and planted community gardens. Following a “prophetic” understanding that “agriculture was to be the foundation of the ministry,” Shiloh purchased an orchard, pastures, a goat dairy and livestock; leased a commercial berry farm; ran a commercial fishing boat; and developed a cannery to provide both income and food to distribute throughout its communal system.

Financial stability was always a concern. Group work projects to support the commune followed out of early group work efforts to run a melon farm in Fontana, California in 1969; to salvage lumber from house teardowns to build “the Land” in 1970; and to pick apples in Wenatchee, Washington. The most successful Shiloh work projects resulted from Weyerhauser reforestation contracts, the eventual issue in an IRS attempt to recover taxes for “Unrelated [to Shiloh’s 501(c) (3) tax exempt status] Business Income.” Shilonites marrying and having children also became unmanageable in 1972-1973. Non-leadership couples moved out of communes to support themselves. The search for financial stability to feed, house, and care for the Shiloh membership moved from early dependence on prayer and donations to increasingly rational attempts to centralize, plan, and control.

Governmental pressures challenged, and ultimately, distorted Shiloh’s ideological positions. Zoning that prohibited “people of unrelated blood” confronted the communards in numerous cities. A typical Shiloh response to city councils and zoning boards was: “God has made of one blood all men” ( Shiloh paraphrase of Acts 17:26). That is, civil law could be nullified by divine law. Draft resistance and draft counseling offered to Shiloh conscientious objectors lead to monitoring by the FBI. Confronting the question of whether personal allowances were “pay” lead to theologizing about the nature of “sharing all things in common,” “vows of poverty,” and conscientious objection to social security. Shiloh had its attorneys draw up new incorporation papers to make it a 501(d) “apostolic communal organization” (like the Hutterites), but finally balked at following through. In this regard, Shiloh sent one of its leaders to visit and consult with Hutterite communities. In 1976, the IRS audited Shiloh leaders who had claimed vows of poverty on their tax returns; in 1978, the IRS audited the organization’s 990 return. In response to IRS pressures, Shiloh theologized all work as “spiritual” labor and placed a statement to this effect in its by-laws as an effort to speak to governmental concerns (Stewart and Richardson 1999a; 1999b). Shiloh had formalized its vision that there was no separation between secular and sacred worlds; all was sacred to the vanguard believer. In the late 1970s, two Shiloh members were kidnapped and deprogrammed when the organization was labeled by some as a “cult.” Even as Shiloh was shifting toward socially mainstream Christian practice and diluting some of its countercultural positions, it found itself accused. This lead to internal speculation that the tax audits, a fate that befell other Jesus Movement communal groups who supported themselves by work teams (e.g., Gospel Outreach; Servant Ministry), was a veiled “anti-cult” move by the government. The group now saw itself as persecuted.

The final challenge for Shiloh-as-commune/ity was what to do with its original leader. Some leaders perceived that Higgins was  leading Shiloh in an unacceptable direction. However, the 1978 coup d’état that followed did derail the movement with the result that hundreds of communards suddenly had to find their way in the world.

leading Shiloh in an unacceptable direction. However, the 1978 coup d’état that followed did derail the movement with the result that hundreds of communards suddenly had to find their way in the world.

REFERENCES

Bodenhausen, Nancy. 1978. “The Shiloh Experience.” Willamette Valley Observer 4/5:10.

Di Sabatino, David. 2007. Frisbee: The Life and Death of a Hippie Preacher: A Bible Story. Jester Media.

Di Sabatino, David. 1994. “The Jesus People Movement: Counterculture Revival and Evangelical Renewal.” M.T.S. thesis. Toronto: McMaster College.

Goldman, Marion. 1995. “Continuity in Collapse: Departure from Shiloh.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34:342-53.

Higgins, John J. 1974a. “Ministry History.” Cold Waters 2/1: 21-23, 29.

Higgins, John J. 1974b. “Ministry History.” Cold Waters 2/2: 25-28, 32.

Higgins, John J. 1973. “The Government of God: Ministry History and Governments.” Cold Waters 1/1: 21-24, 44.

Isaacson, Lynne. 1995. “Role Making and Role Breaking in a Jesus Commune.” Pp. 181-201 in Sex, Lies, and Sanctity, edited by Mary Jo Neitz,. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Kramis, Keith. 2002-2013. “Shiloh Youth Revival Centers Alumni Association.” Accessed from www.shilohyrc.com/ on 27 February 2013.

Lofland, John and James T. Richardson. 1984. “Religious Movement Organizations: Elemental Forms and Dynamics.” Pp. 29-52 in Research in Social Movements, Conflict and Change, edited by Louis Kriesberg, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Murphy, Jean. 1996. “A Shiloh Sister’s Story.” Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living 92: 29-32.

Peterson, Joe V. 1996. “The Rise and Fall of Shiloh.” Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living 92: 60-65.

Peterson, Joe V. 1990. “Jesus People: Christ, Communes and the Counterculture of the Late Twentieth Century in the Pacific Northwest.” Master of Religion thesis. Eugene, OR: Northwest Christian College.

Pierson, Arthur Tappan. 2008. George Muller of Bristol and his Witness to a Prayer-Hearing God . Peabody, MA: Hendrickson.

Richardson, James T. 1979. Organized Miracles: A Study of a Contemporary, Youth, Communal Fundamentalist Organization. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Stewart, David Tabb. 1992. “A Survey of Shiloh Arts.” Communal Societies 12:40-67.

Stewart, David Tabb and James T. Richardson. 1999a. “Mundane Materialism: How Tax Policies and Other Governmental Regulations Affected Beliefs and Practices of Jesus Movement Organizations.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 67/4:825-47.

Stewart, David Tabb and Richardson, James T. 1999b. “Economic Practices of Jesus Movement Groups.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 14/3: 309-324.

Taslimi, Cheryl Rowe, Ralph W. Hood, and P.J. Watson. 1991. “Assessment of Former Members of Shiloh: The Adjective Check List 17 Years Later.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30:306-11.

Tozer, Aiden Wilson. 1992. Knowledge of the Holy: The Attributes of God: Their Meaning in the Christian Life. New York: HarperOne.

Youth Revival Centers, Inc. 1973. Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book. Dexter, OR: Youth Revival Centers, Inc.

Authors:

David Tabb Stewart

Post Date:

4 March 2013