FUNDAMENTALIST LATTER-DAY SAINTS TIMELINE

1843: Joseph Smith announced his revelation on plural marriage.

1862: The U.S. Congress passed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act.

1882: The U.S. Congress passed the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act.

1886 (September 26-27): Fundamentalists claimed that John Taylor received a revelation about the continuation of plural marriage while on the underground.

1887: The U.S. Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act.

1890 (October 6): Wilfred Woodruff announced a Manifesto forbidding plural marriage.

1904-1907: Hearings were held in the U.S. Senate on the seating of Reed Smoot as Senator from Utah.

190 (April 6: ) A second Manifesto was issued by Joseph F. Smith that threatened excommunication for LDS members who engaged in plural marriage.

1910: LDS Church began a policy of excommunication for new plural marriages.

1929-1933: Lorin C. Woolley created the “Priesthood Council.”

1935 (September 18): Lorin C. Woolley died, and Joseph Leslie Broadbent became head of the Priesthood Council.

1935: Broadbent died, and John Y. Barlow became head of the Priesthood Council.

1935: Truth magazine began publication.

1941: Leroy S. Johnson and Marion Hammon were ordained to the Priesthood Council by John Y. Barlow

1942: The United Effort Plan Trust was established.

1944 (March 7-8): The Boyden polygamy raid was conducted.

1949 (December 29): John Y. Barlow died, leading to a succession crisis in the Priesthood Council.

1952: The Priesthood Council split when Joseph W. Musser announced that Rulon Allred would become a new member. Result was two factions: the FLDS (Leroy S. Johnson) and the Apostolic United Brethren (Rulon Allred).

1953 (August 16): In the case of In re Black the U.S. Supreme Court held that polygamous parents have no rights as parents.

1953 (July 26): The raid on the polygamist community at Short Creek was conducted.

1954 (January 12): With Joseph Musser’s death, Rulon Allred became the head of the Priesthood Council.

1985: Colorado City was incorporated.

1986: Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints organized.

1986 (September 26): J. Marion Hammon dedicated Centennial Park (new intentional community formed by the Second Warders).

1986 (November 25): Leroy S. Johnson died, and Rulon T. Jeffs became the FLDS leader.

2002 (September 8): Rulon Jeffs died.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

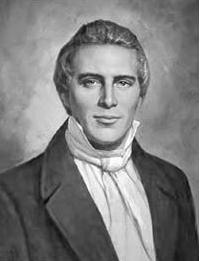

Mormon fundamentalism originated in the teachings of the Latter-day Saint Prophet, Joseph Smith, who introduced the doctrine of a plurality of wives to a select group of his followers in the 1840s. By the time of his death in 1844, according to scholar George D. Smith’s analysis, at least 196 men and 717 women had entered the practice privately (Smith 2008:573-639). His vision for the “new and everlasting covenant of marriage” became part of LDS scripture on July 12, 1843 with the 132 nd section of the Doctrine and Covenants. He positioned the uniquely Mormon interpretation of the significance of marriage, in the restoration of the model of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. According to the revelation, “Celestial marriage” was marriage for time and eternity. Men with priesthood authority had the power to seal men and women for eternity. Essential for the highest level of salvation in what Smith described as the “Celestial” kingdom, Smith interpreted plural marriage “as a uniquely exalted form of ‘celestial marriage’—the ‘further order’ of the patriarchal order of marriage mentioned in Doctrine of Covenants” (Bradley 1993:2)

of a plurality of wives to a select group of his followers in the 1840s. By the time of his death in 1844, according to scholar George D. Smith’s analysis, at least 196 men and 717 women had entered the practice privately (Smith 2008:573-639). His vision for the “new and everlasting covenant of marriage” became part of LDS scripture on July 12, 1843 with the 132 nd section of the Doctrine and Covenants. He positioned the uniquely Mormon interpretation of the significance of marriage, in the restoration of the model of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. According to the revelation, “Celestial marriage” was marriage for time and eternity. Men with priesthood authority had the power to seal men and women for eternity. Essential for the highest level of salvation in what Smith described as the “Celestial” kingdom, Smith interpreted plural marriage “as a uniquely exalted form of ‘celestial marriage’—the ‘further order’ of the patriarchal order of marriage mentioned in Doctrine of Covenants” (Bradley 1993:2)

The next three presidents of the LDS church were also polygamists. Brigham Young, John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff led a church that had at its center the doctrine of plural marriage. As prophet and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Brigham Young expanded the practice of plurality, married at least fifty-five women himself, and had fifty-seven children (Johnson 1987). Like Young, President John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff continued to tie the Mormon concept of salvation and the afterlife to the doctrine of plural marriage. With the 1890 Manifesto, the church began a multi-year process of ending the official practice of plural marriage among the Latter-day Saints.

Despite LDS claims to priesthood authority or the revelatory origins of the doctrine, the federal government fought the church and its practice of plural marriage through the second half of the nineteenth century. After the public announcement of the practice by Apostle Orson Pratt from the pulpit in front of an Utah audience of thousands of Latter-day Saints, the Congress passed a series of bills designed to limit the practice, punish those who continued to violate the law, and ultimately to damage the church corporation itself. These included the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862, the Poland Act of 1874, the Edmunds Act of 1882, and, finally, the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887. During the 1880s and the federal pursuit of polygamists, men and women went on the “underground” to avoid arrest, hiding in Arizona, Nevada, Idaho and throughout Utah. Church president John Taylor went into hiding in January, 1885 and died two years later on the underground (Bradley 1993:5).

In important ways, the story of the FLDS begins with the 1890 Manifesto. President Wilford Woodruff introduced the Manifesto at the October semiannual conference of the Church. Eventually included in the Doctrine and Covenants, it was initially essentially a press release. It denied that the LDS church advocated continuing in the practice of plural marriage, stating that “We are not teaching polygamy or plural marriage, nor permitting any person to enter into its practice….” It went on to assert:

Inasmuch as laws have been enacted by Congress forbidding plural marriages, which laws have been pronounced constitutional by the court of last resort, I hereby declare my intention to submit to those laws, and to use my influence with the members of the Church over which I preside to have them do likewise….I now publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land (Doctrine and Covenants).

The impact of the Manifesto was neither absolute nor swift in causing plural marriages to cease. In fact, for the next two decades at least 250 new marriages were performed in secret in the Salt Lake Valley, the Canadian or Mexican colonies or in other areas throughout the church (Hardy 1992:167-335, Appendix II).

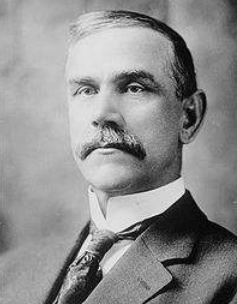

During the U.S. Senate hearings over the confirmation of Utah Senator Reed Smoot between 1904-1907, plural marriage surfaced  again as a national issue. Smoot was not himself a polygamist, but the issue was whether he would be loyal to the laws of the United States or those of his church. In response to this new pressure, President Joseph F. Smith in April conference, 1904 announced the “Second Manifesto” that added the threat of excommunication to those who failed to follow the prohibition against plural marriages. The document decried allegations that new marriages had occurred “with the sanction, consent or knowledge of the Church” (Allen and Leonard 1976:443).

again as a national issue. Smoot was not himself a polygamist, but the issue was whether he would be loyal to the laws of the United States or those of his church. In response to this new pressure, President Joseph F. Smith in April conference, 1904 announced the “Second Manifesto” that added the threat of excommunication to those who failed to follow the prohibition against plural marriages. The document decried allegations that new marriages had occurred “with the sanction, consent or knowledge of the Church” (Allen and Leonard 1976:443).

President Smith framed the discussion with reference to the church’s patriotism and particularly the importance of the guarantee of freedom of religion. “What our people did in disregard of the law and the decisions of the Supreme Court affecting plural marriages,” he said, “was in the spirit of maintaining religious rights under constitutional guarantees, and not in any spirit of defiance or disloyalty to the government.” Importantly, “the Church abandoned the controversy and announced its intention to be obedient to the laws of the land” (Clark 1965-75:4:151).

Regardless of the Second Manifesto, considerable ambiguity still existed in the church over the issue of plural marriage. Marriages continued to be performed without the official sanction of the Church president and sometimes by General Authorities of the church. A significant tightening of the policy and punishment for disobedience of the prohibition occurred during the 1910s under presidents Joseph F. Smith and Heber Grant. Church President Grant spoke publicly about priesthood authority, and clarified the official LDS position, asserting that the “keys” rested only in the prophet and in the Church (Bradley 1933:13).

Although Short Creek, Arizona became publicly identifiable in 1953 with the Arizona raid on its polygamous community, settlers first came to the area in the 1910’s. Nestled in the stark desert landscape at the base of the Vermillion Cliffs, beginning in the late 1920s, Short Creek became the home to polygamists seeking refuge from persecution from the world outside. When John Y. Barlow became senior member of the Priesthood Council and fundamentalist leader, he encouraged his followers to gather at Short Creek. Practicing the principle of the gathering, like mid-nineteenth century Latter-day Saints, true believers formed communities apart from the mainstream where they could continue in their practice of a plurality of wives. It is estimated that forty families settled in the isolated landscape of the Arizona strip country.

In 1935, the LDS church excommunicated Short Creek polygamists, Price W. Johnson, Edner Allred, and Carling Spencer. While Barlow was absent from his leadership role and visiting with fundamentalists throughout the region, Joseph Jessop, and later his son, Fred Jessop, guided social life in Short Creek and helped with economic growth and development. The Barlows, Jessops and Johnsons became closely connected through religious and community ties through the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1944, in the first mass arrest of polygamists, federal and state officials arrested fifty men and women in both Utah and Arizona. The Boyden Raid executed charges of conspiracy, Mann Act and Lindberg Act violations. Eventually, fifteen men served in the Utah State penitentiary before signing a loyalty oath that allowed some of them to return to their families before their terms had transpired (Bradley 1993:79).

On July 26, 1953, the government of Arizona raided the polygamous community of Short Creek. As more than 100 vehicles of the  state rolled over the rocky roadbeds leading into town, Governor Howard Pyle justified the raid over the radio, announcing his fight against “insurrection within [ Arizona’s] own borders,” with the intent “to protect the lives and future of 263 children . . . . the product and the victims of the foulest conspiracy . . . . a community dedicated to the production of white slaves. . . . degrading slavery.” He elaborated further on this theme:

state rolled over the rocky roadbeds leading into town, Governor Howard Pyle justified the raid over the radio, announcing his fight against “insurrection within [ Arizona’s] own borders,” with the intent “to protect the lives and future of 263 children . . . . the product and the victims of the foulest conspiracy . . . . a community dedicated to the production of white slaves. . . . degrading slavery.” He elaborated further on this theme:

Here is a community—many of the women, sadly right along with the men—unalterably dedicated to the wicked theory that every maturing girl child should be forced into the bondage of multiple wifehood with men of all ages for the sole purpose of producing more children to be reared to become mere chattels of this totally lawless enterprise.

As the highest authority in Arizona, on whom is laid the constitutional injunction to ‘take care that the laws be faithfully executed,’ I have taken the ultimate responsibility for setting into motion the actions that will end this insurrection (Pyle 1953).

More than one hundred Arizona state officials brought with them the warrants for thirty-six men and eighty-six women. Thirty- nine of the warrants were for individuals who lived on the Utah side of town. The charges included: rape, statutory rape, carnal knowledge, polygamous living, cohabitation, bigamy, adultery, and misappropriation of school funds (Bradley 1993:131). The raid sought to “rescue 263 children from virtual bondage under the communal United Effort Plan,” according to Attorney General Paul LaPrade. “The principle objective is to rescue these children from a life-time of immoral practices without their ever having had an opportunity to learn of or observe the outside world and its concepts of decent living” (LaPrade 1953).

nine of the warrants were for individuals who lived on the Utah side of town. The charges included: rape, statutory rape, carnal knowledge, polygamous living, cohabitation, bigamy, adultery, and misappropriation of school funds (Bradley 1993:131). The raid sought to “rescue 263 children from virtual bondage under the communal United Effort Plan,” according to Attorney General Paul LaPrade. “The principle objective is to rescue these children from a life-time of immoral practices without their ever having had an opportunity to learn of or observe the outside world and its concepts of decent living” (LaPrade 1953).

Over the next three days the state set up a magistrate’s court in the schoolhouse at the center of town. The men would be transported for a preliminary hearing in Kingman on August 31, 1953. The state also held juvenile court where Judges Lorna Lockwood and Jesse Faulkner took custody of each child and made them wards of the court. Judges, deputy sheriffs and court photographers visited the homes of polygamous families in Short Creek gathering evidence to support the accusations. On the third day after the raid, the state gave mothers the chance to travel with their children (153 in total) to foster homes in Mesa, Phoenix and other locations nearby where they stayed for the next two years while their cases played out in the court and they appeared before state agencies. Two years after the raid all of the women had returned to Short Creek with the exception of one who had been a minor at the time of the raid, but who returned once she was legally old enough to do so.

Utah took a different tack in attempting to dismantle plural families. Judge David F. Anderson, of Utah’s Sixth District Juvenile Court in St. George, Utah devised a legal tactic that attacked the alleged neglect of the children of polygamous children. Although Anderson filed twenty different petitions alleging that eighty children had been neglected, he chose to make Vera and Leonard Black a test case of the legitimacy of this approach. The polygamous couple had eight children together by 1953. Anderson depended on Section 55-10-6, Utah Code Annotated, 1953 for the definition of neglect: “A child who lacks proper parental care by reason of the fault or habits of the parent, guardian or custodian….A child whose parent, guardian or custodian neglects or refuses to provide proper or necessary subsistence, education, medical or surgical care or other care necessary for his health, morals or well-being. A child who is found in a disreputable place or who associates with vagrant, vicious, or immoral persons.”

The case, In Re Black , moved through the courts for almost two years, eventually in 1955 ending up on appeal at the Utah Supreme Court. In 1955, the Court upheld the decision of the lower court against the mother, concluding that polygamists have no right to the custody of their children. The majority opinion stated: “the practice of polygamy, unlawful cohabitation and adultery are sufficiently reprehensible, without the innocent lives of children being seared by their evil influence. There can be no compromise with evil” (Driggs 1991:3) After staying in foster care for three years, Vera gained custody of her children, but only after she signed an oath denying she believed in plural marriage (Bradley 1993:178).

Estimates of the number of individuals practicing plural marriage in the late twentieth century, ranged from thirty to fifty thousand. Before he died, polygamist Ogden Kraut estimated that “there are probably at least 30,000 people who consider themselves Fundamentalist Mormons, espousing at least the belief in the doctrine of plural marriage” (Kraut 1989). Historian Richard Van Wagoner also estimated 30,000 fundamentalists in 1986 (Van Wagoner 1992). In 2009, Melton offered the same estimate (Melton 2009:650). Since its inception among the Mormons in the 1840s, the practice of a plurality of wives has proceeded beneath the surface in a private, subterranean world protected by religious ritual and belief, behavior and life practice, and sometimes, as in the case of Short Creek, Arizona, by the protection provided by the natural world.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The FLDS believe in the core doctrines of the nineteenth century Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, including the Principle (the doctrine of plural marriage), consecration and stewardship (a type of communal organization), the plurality of Gods (the potential for every righteous man to become a God in the afterlife), and the right of a prophet to receive revelations from God. Many describe the LDS Church as God’s church and some participate in LDS temple rituals, serve LDS missions or pay tithes in LDS wards before they are excommunicated for their polygamous beliefs or life style.

Although outsiders commonly describe Mormon fundamentalists as polygamists, the FLDS themselves use a variety of terms to describe their unique practice of a plurality of wives: “the Principle,” “Celestial Marriage,” the “New and Everlasting Covenant,” “plural marriage,” or the “Priesthood work” (Quinn 1993:240-41).

The principal point of division between the FLDS and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is over priesthood authority. The fundamentalists believe that the LDS Church moved off course with the 1890 Manifesto and eventually lost priesthood authority to perform Celestial marriages. The FLDS believe that a plurality of wives is a core doctrine of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, essential to salvation and a sign of individual righteousness. Moreover, the FLDS recognize priesthood authority in their own leadership, authority they trace to 1886 through the narrative of Lorin C. Woolley. Woolley claimed that in 1886 President John Taylor was living in Centerville, Utah on the underground hiding from federal officials. He reported being was visited by the Prophet Joseph Smith and pledging that he would “suffer my right hand to be cut off” before he would sign a document ordering the desertion of plural marriage (Musser 1934). According to Joseph Musser’s 1912 account, Taylor allegedly instructed Woolley and the other men present: George Q. Cannon, L. John Nuttall, John W. Woolley, Samuel Bateman, Daniel R. Bateman, Charles H. Wilkins, Charles Birrell, and George Earl to continue the practice of plural marriages. If the LDS Church abandoned the practice, or the “Principle,” a smaller group of five men—Cannon, Wilkins, Bateman, John W. Woolley, and Lorin C. Woolley would carry priesthood authority forward to perform plural marriages and could ordain others to do the same (Bradley 1993: 19). By 1929, Woolley was the only one of these men still alive. He transferred the same priesthood power to a select group in the “Council of Friends or the Priesthood Council.” These men became the leaders of the movement that would eventually be known as Mormon fundamentalism, former Latter-day Saints who continued in the practice of a plurality of wives.

For the FLDS, the marriage relationship was the nucleus of a family kingdom. The primary aim of marriage, however, was not love, but a celestial social order. Plural marriage was part of a deferential and hierarchical society strictly ordered along patriarchal lines. The child was subordinate to the mother; the mother bowed to her husband’s authority; he, in turn, looked to the prophet for direction; while the prophet was answerable to and spoke for Jesus Christ. As God was at the head of the world, the husband was the earthly head of the family. The appropriate behavior directed toward one’s superior consisted of deference and obedience. The appropriate behavior directed toward one’s subordinates consisted of instruction, benevolence, and the meting out of either rewards or punishments (Bradley 1993:101).

Men and women married to “Multiply and replenish the earth.” Sexuality had religious significance and was tied to procreation. Musser taught that “every normal woman yearns for wifehood and motherhood. She yearns to wear the crown of glory. The most precious and yearned for jewels are children to call her mother” (Musser 1948:134).

Joseph Musser articulated the meaning of the difference between men and women for Truth magazine in 1948: “Thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee. In placing man at the head, he bearing the Priesthood, a law, an eternal law, was announced.” The roles of men and women were scripturally defined and existed to create social order. “Man, with divine endowments, was born to lead, and woman to follow, though often times the female is endowed with rare talents of leadership. But women, by right, look to the male members for leadership and protection.” According to Musser, women should “respect and revere themselves, as holy vessels, destined to sustain and magnify the eternal and sacred relationship of wife and mother.” Women’s role was related to that of men, as the “ornament and glory of man; to share with him a never fading crown, and an eternally increasing dominion” (Musser 1948:134).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The scriptures used by the FLDS are the same as those of the LDS church: the Book of Mormon, the Bible, the Pearl of Great Price and the Doctrine and Covenants. Beliefs such as the plurality of Gods, the Word of Wisdom, the nature of heaven and the afterlife are virtually the same. Both churches are founded on the structure of male, priesthood authority.

Although many of the religious rituals practiced by the FLDS resemble those practiced by the Latter-day Saints, the tradition of holding Sunday School in private homes where the sacrament is served, rather than in the meetinghouse, is one significant  difference. The Johnson meetinghouse at the center of the community in Colorado City is the size of two LDS stake centers and is the backdrop for group worship services, community dances, and community business meetings. The central meeting space holds an audience of between 1,500 and 2,500. Also, the FLDS hold worship meetings throughout the week as was true in the nineteenth century LDS church. Like the LDS, fundamentalists wear sacred priesthood undergarments and choose modest clothing over modern popular styles.

difference. The Johnson meetinghouse at the center of the community in Colorado City is the size of two LDS stake centers and is the backdrop for group worship services, community dances, and community business meetings. The central meeting space holds an audience of between 1,500 and 2,500. Also, the FLDS hold worship meetings throughout the week as was true in the nineteenth century LDS church. Like the LDS, fundamentalists wear sacred priesthood undergarments and choose modest clothing over modern popular styles.

Priesthood leaders, and ultimately the group’s prophet, arrange marriages among the FLDS in a practice called placement marriage. One plural wife commented that “we were raised believing that the Priesthood [Council] would choose our mate and that we were not to allow ourselves to fall in love with anybody,” and another FLDS youth said “In our group we don’t date” (Quinn 1992:257). The church president and leader of the Priesthood Council prays for God’s instruction about marriage partnerships. For the FLDS, arranged marriages create social stability and a sense of familial structure that has eternal significance.

The FLDS family is strictly patriarchal, although in the day-to-day life of a family women play key economic and social roles. Many have a high degree of functional autonomy. There are multiple styles of housing for families in FLDS communities. Some families prefer to have all of the wives and their children in the same household and other have multiple households for different mothers and their children. Colorado City/Hildale and Centennial Park are distinguished by the number of large-scale family homes. Local architect, Edmund Barlow, in 2003 suggested that as homes became larger in terms of square footage, they had to accommodate housing codes for apartment units. Large families with multi-families under a single roof built Sunday School rooms for family worship in their homes.

Joseph Smith revealed the principle of consecration and stewardship to the nineteenth century church. In Utah, the “United Order” functioned as an intentional community and the expression of religious ideals. Under the United Order, members consecrated property and received a stewardship that obligated them to use resources for the good of the group as well as the individual. Under Barlow’s leadership, the Priesthood Council in 1936 formed the United Trust. Besides land, the trust owned a sawmill and equipment used for agriculture “for the purpose of building up the Kingdom of God” (Driggs 2011:88). Six years later, the community dissolved the trust and returned the property. The second attempt at a communal organization of property was the United Effort Plan, which was a property holding or business trust rather than religious organization. At one point, the property in the UEP was valued at more than $100 million and “subject to the disposal of the UEP board or the Priesthood Council (Hammon and Jankowiak 2011:52).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The pinnacle of FLDS leadership and organization is the Priesthood Council, which they believe holds authority to perform plural marriages and which is considered higher in authority than the LDS church itself. Members of the group, also called the Council of Friends, are apostles of Jesus Christ or high priest apostles (Hammon and Jankowiak 2011:44). The president of the high priesthood, the senior member of the group, leads the council. According to the fundamentalists, John W. Woolley led the Priesthood Council until his death in 1928. At that time, Lorin Woolley called new members to the council, ordaining four new men as apostles: J. Leslie Broadbent, John Y. Barlow, Joseph W. Musser, and Charles F. Zitting (Hammon and Jankowiak 2011:45). Typically, the senior apostle or president of the council receives a revelation about who will be called to the council, or the Brethren. During these same years, the LDS church distanced itself from the practice of a plurality of wives. The movement eventually known as Mormon fundamentalism organized around those individuals who believed plural marriage was essential to their salvation and questioned both the authority and the course that the LDS church had taken.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Between the 1930s and the present, educational training has varied. In 1991, the community developed an elaborate plan for “Barlow University,” with a physical plan for a horseshoe loop of educational buildings like that at the University of Utah. Under the leadership of Warren Jeffs in the first decade after 2000, parents took their children out of public schools and home schooled them. For decades before that, children attended schools funded with tax dollars including an elementary school, middle school and high school. Many members of the community attended Southern Utah State College at Cedar City to receive their teaching credentials, and according to D. Michael Quinn’s estimate in 1993, 85 percent of the young men and women in the group attended college, including Mohave County Community College that was located in town (Quinn 1993:267). In 1960, Short Creek changed its name to Colorado City/Hildale and built a community school—the Colorado City Academy. Until its closure in 1980, the Academy offered an education grounded in religious instruction as an alternative to public education.

In 1981, the community of the FLDS divided into two groups over priesthood leadership (priesthood council vs. one man doctrine), different interpretations of private/collective property (entitlements), and social practices (varying degrees of scriptural and social orthodoxy). Known from that time forward as “First Warders” or “Second Warders,” the split created competing and sometimes hostile sects. After 1984, Leroy Johnson led the FLDS under the “one man doctrine” and dismantled the Priesthood Council until the second coming of Christ (Driggs 2011:91). When Rulon T. Jeffs succeeded Johnson as prophet of the First Ward in 1986, the newly organized Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, excommunicated the members of the Second Ward.

REFERENCES

Allen, James B. and Glen A. Leonard. 1976. The Story of the Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company and the Historical Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Bradley, Martha Sontag. 1993. The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Clark, James R., ed. 1965-1975. Messages of the First Presidency. Vol. 4. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft.

Hardy, B. Carmon. 1992. Solemn Covenant: The Mormon Polygamous Passage. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Johnson, Jeffrey Ogden. 1987. “Determining and Defining ‘Wife’ — The Brigham Young Households.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 20:57-70.

Kraut, Ogden. 1989. “The Fundamentalist Mormon: A History and Doctrinal Review.” Paper presented at the Sunstone Theological Symposium. Salt Lake City, Utah.

LaPrade, Paul, quoted in Arizona Daily Star. July 27, 1953.

Melton, J. Gordon. 2009. “Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.” Pp. 649-50 in Melton’s Encyclopedia of American Religion, 8 th Edition. Detroit, MI: Gale, Cengage Learning.

Musser, Joseph White. 1948. “The Inalienable Rights of Women.” Truth , 14 October, p. 134.

Musser, Joseph White. 1934. The New and Everlasting Covenant of Marriage an Interpretation of Celestial Marriage, Plural Marriage. Salt Lake City: Truth Publishing Company.

“Official Declaration 1.” 1890. Doctrine and Covenants. Salt Lake City, UT, October 6. Accessed from http://www.lds.org/scriptures/dc-testament/od/1?lang=eng on 15 October 2012.

Pyle, Howard W. 1993. Radio Address. July 26, 1953. KTAR Radio. Phoenix, Arizona.

Quinn, D. Michael. 1993. “Plural Marriage and Fundamentalism.” Pp. 240-93 in Fundamentalisms and Society: Reclaiming the Sciences, the Family, and Education , edited by Martin E. Marty and R. Scott Appleby. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

Smith, George D. 2008. Nauvoo Polygamy: “But We Called It Celestial Marriage.” Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books.

Van Wagoner, Richard. 1992. Mormon Polygamy: A History. Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Allred, B. Harvey. 1933. A Leaf in Review. 2d ed. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers.

Allred, Rulon C. 1981. Treasures of Knowledge: Selected Discourses and Excerpts from Talks. 2 vols. Hamilton, MN: Bitterroot Publishing.

Allred, Vance L. 1984. “Mormon Polygamy and the Manifesto of 1890: A Study of Hegemony and Social Conflict.” Senior Thesis. Missoula, MT: University of Montana.

Altman, Irwin and Joseph Ginat. 1996. Polygamous Families in Contemporary Society. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, J. Max. 1979. The Polygamy Story: Fiction and Fact. Salt Lake City: Publishers Press.

Baird, Mark J. and Rhea A. Kunz Baird, eds. [ca. 2003] Reminiscences of John W. and Lorin C. Woolley. 5 vols. 2nd edition. Salt Lake City: Lynn L. Bishop.

Barlow, John Y. 2005. “A Selection of the Sermons of John Y. Barlow, 1940-49.” ebooks@thoughtfactory. B17.

Batchelor, Mary, Marianne Watson, and Anne Wilde. 2000. Voices in Harmony: Contemporary Women Celebrate Plural Marriage. Salt Lake City: Principle Voices.

Bennion, Janet. 1998. Women of Principle: Female Networking in Contemporary Mormon Polygyny. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bistline, Benjamin. 1998. The Polygamists: A History of Colorado City. Colorado City, Arizona: Ben Bistline and Associates.

Bradley, Martha. 2004. “Cultural Configurations of Mormon Fundamentalist Polygamous Communities.” Nova Religio 8:5- 38.

Bradley, Martha Sontag. 2012. Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

Daynes, Kathryn M. 2001. More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840-1910. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Driggs, Ken. 2005. “Imprisonment, Defiance, and Division: A History of Mormon Fundamentalism in the 1940s and 1950s.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 38:65-95.

Driggs, Ken. 2001. “This Will Someday Be the Head and Not the Tail of the Church.’” Journal of Church and State 43:49-80.

Driggs, Ken. 1992. “’Who Shall Raise the Children?’ Vera Black and the Rights of Polygamous Utah Parents.” Utah Historical Quarterly 60:27-46.

Driggs, Ken. 1991a. “Twentieth-Century Polygamy and Fundamentalist Mormons and Southern Utah.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 24:44-58.

Driggs, Ken. 1991b. “ Utah Supreme Court Decides Polygamist Adoption Case.” Sunstone 15: 67-8. Accessed from http://www.childbrides.org/politics_sunstone_UT_Supreme_Court_decides_polyg_adoption_case.html on 15 October 2012.

Driggs, Ken. 1990a. “After the Manifesto: Modern Polygamy and Fundamentalist Mormons.” Journal of Church and State 32:367-89.

Driggs, Ken. 1990b. “Fundamentalist Attitudes toward the Church as Reflected in the Sermons of the Late Leroy S. Johnson.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23: 38-60.

Hales, Brian C. 2006. Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations after the Manifesto. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books.

Hales, Brian C., and J. Max Anderson. 1991. The Priesthood of Modern Polygamy: A LDS Perspective. Portland, OR: Northwest Publishers.

Jacobson, Cardell. 2011. Mormon Polygamy in the United States: Historical, Cultural, and Legal Issues. New York: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Leroy S. The L. S. Johnson Sermons, 1983-1984. 7 vols. Hildale, Utah: Twin Cities Courier.

Kunz, Rhea Allred. 1978. Voices of Women Approbating Celestial or Plural Marriage. Draper, UT: Review and Preview Publishers.

Kunz, Rhea Allred, ed. 1984. A Second Leaf in Review. n.p.

Marty, Martin, and R. Scott Appleby, eds. 1991-1995. The Fundamentalism Project. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Musser, Joseph White. 1953-57. Star of Truth. 4 vols. n.p.

Quinn, D. Michael. 1998. “Plural Marriage and Mormon Fundamentalism.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 311-68.

Quinn, D. Michael. 1983. J. Reuben Clark: The Church Years. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press.

Solomon, Dorothy Allred. 2003a. Daughter of the Saints: Growing Up in Polygamy. New York: W. W. Norton.

Solomon, Dorothy Allred. 2003b. Predators, Prey, and Other Kinfold: Growing Up in Polygamy. New York: W. W. Norton.

Solomon, Dorothy Allred. 1984. In My Father’s House. New York: Franklin Watts.

Watson, Marianne T. 2003. “Short Creek: ‘A Refuge for the Saints.’” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 36:71-87.

Wright, Stuart A. and James T. Richardson. 2011. Saints under Siege: The Texas State Raid on the Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints. New York : New York University Press.

Post Date:

31 October 2012

FUNDAMENTALIST CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS VIDEO CONNECTIONS