FATHER DIVINE PEACE MISSION TIMELINE

1879: George Baker was born to a poor black family in Rockville, Maryland.

Circa 1900: Baker settled in Baltimore, and worked as a gardener and a preacher.

1906: Baker visited the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles where he reportedly spoke in tongues.

1907: Baker met and began working with Samuel Morris. Baker took the name “the Messenger.”

1908: John Hickerson joined the two men and the group began preaching together.

1912: The group broke up and the Messenger traveled to Georgia to preach.

1913: The Messenger began to call himself God when preaching to his large audience. A few local pastors had him arrested and taken to court, where he was declared insane. He was asked not to return to Georgia.

1914: The Messenger and the movement moved to New York City and began to live communally among his followers.

Circa 1915: The Messenger reportedly married Peninah.

1915-1919: During this period, the Messenger changed his name to Major Jealous Devine, shortened to M.J. Devine. This evolved into Father Divine.

1929: Widespread desperation due to the Great Depression gave Father Divine and the Movement an influx of followers.

1930: Hundreds of people visited the house each Sunday and began irritating the surrounding community.

1931: On Sunday November 15, the police broke into 72 Macon St. and arrested Father Divine and eighty of his devotees.

1932: Father Divine was convicted by the court and sentenced to prison. He was released soon after, following the death of the presiding judge.

1937: Former follower Verinda Brown sued Father Divine for money donated to the movement.

1940: Father Divine incorporated several Peace Mission Movement centers to avoid future lawsuits.

1940: The Peace Mission Movement gathered 250,000 signatures on an anti-lynching petition.

1940: Father Divine announced the passing of Peninah.

1942: Father Divine moved the headquarters out of New York to Philadelphia.

1946 (August): Father Divine at age sixty six announced his marriage to a twenty-one-year old white female, Edna Rose Ritchings, who was known in the movement as Sweet Angel. She later took the name Mother Divine.

1953: Father Divine and his wife moved to Woodmont, a large estate outside of Philadelphia that has remained the headquarters of the Peace Mission Movement.

1965: Father Divine passed away.

1968: Tommy Garcia, reported to be the adopted son of Father Divine, ran away from Woodmont.

1971: Jim Jones arrived at the Woodmont estate and claimed to be the incarnation of Father Divine.

1992: The Movement’s newspaper, the New Day, ceased publication.

2012: Two major hotels operated by the Movement were sold.

2012: Construction of a building that would hold archives of the movement began.

2017 (March 4): Mother Divine died at Woodmont at age ninety-two.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

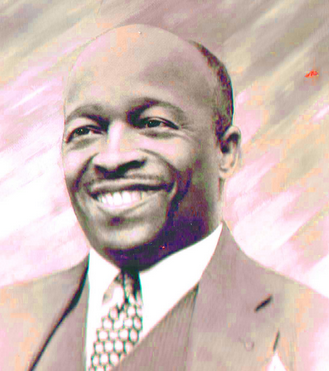

There are a number of conflicting biographical accounts of the man who became known as Father Divine. The most common and probable account is that he was born as George Baker in 1879 to parents Nancy and George Baker Sr., two ex-slaves living in Rockville, Maryland. Father Divine himself spoke little of his childhood or background. He was almost certainly born between 1860 and 1880, with 1878 the most frequently reported year. Baker lived in an impoverished town called Monkey Run, where he attended a segregated public school and Jerusalem Methodist Church. He remained in Monkey Run until his mother’s death in 1897. He then simply left his family behind, with his destination unknown.

Prior to 1900, there is little consensus about Baker’s whereabouts or activities. There are unverified accounts that he was jailed for riding in the white section of a trolley, and refusing to attend segregated schools (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). By 1900, Baker was living in Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked as a gardener and assistant preacher in a local Baptist storefront church. He attended the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 and experienced a major spiritual awakening as he spoke in tongues. For the first time he began to recognize his inner divinity and think of himself in god-like terms (Watts 1995:25). In 1907, Baker met a man named Samuel Morris, a preacher to whom Baker was drawn and who called himself Father Jehovia. Baker found the philosophy that Morris taught, that God is within each individual, to be compelling. According to some reports, Morris referred to himself as God. The two men began working together, and Baker began to refer to himself as “the Messenger,” while sharing the godship with Father Jehovia.

riding in the white section of a trolley, and refusing to attend segregated schools (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). By 1900, Baker was living in Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked as a gardener and assistant preacher in a local Baptist storefront church. He attended the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 and experienced a major spiritual awakening as he spoke in tongues. For the first time he began to recognize his inner divinity and think of himself in god-like terms (Watts 1995:25). In 1907, Baker met a man named Samuel Morris, a preacher to whom Baker was drawn and who called himself Father Jehovia. Baker found the philosophy that Morris taught, that God is within each individual, to be compelling. According to some reports, Morris referred to himself as God. The two men began working together, and Baker began to refer to himself as “the Messenger,” while sharing the godship with Father Jehovia.

In 1908, John Hickerson began working with Baker and Morris. Hickerson was another African American preacher in the area, who had taken the name St. John the Vine. The trio worked together until 1912 when the partnership broke up, likely due to the difficulty of sharing their divinity. The Messenger relocated to the South and settled in Valdosta, Georgia where his congregation was predominantly black women. In 1913, he had a disagreement with preachers in Savannah that led to his spending sixty days on a chain gang. Once he was released from the camp, however, he continued to preach and began to gain a group of followers. Despite his moderate success, he faced harassment from local preachers that resulted in his arrest. He was declared insane, largely, it appears, due to his claim that he himself was God. Some sources report that the Messenger was briefly committed to an asylum (Miller 1995), though others report that he was simply advised to leave Georgia and never return (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). Whatever the sequence of events, The Messenger left Georgia with about a dozen followers, and traveled north to New York City in 1919. One of those followers was Peninah, the woman who he would later marry. There is very little known about Peninah’s (also Penninah, Peninnah, Penniah) life prior to her joining The Messinger.

The Messenger and his followers stayed in Manhattan briefly, and then settled in Brooklyn in 1914 where they lived communally  in a small house for several years. The Messenger took on responsibility for finding jobs for his followers, and they, in turn, returned their earnings to him. With those funds The Messenger paid for the rent, food, and living expenses. During this time, the group was growing slowly. Peninah, managed the house and prepared food for the group. At this time, or perhaps earlier as some sources suggest, The Messenger married Peninah despite his ban on marriage for his disciples. He stated that the marriage was spiritual and not sexual, as celibacy was required by the group’s moral code. It is not clear whether a marriage license was obtained. While living in New York, The Messenger decided to change his name once again. This time he assumed the name Major Jealous Devine, which was later abbreviated M.J. Devine. Subsequently, the name M.J. Devine evolved into Father Divine (2008).

in a small house for several years. The Messenger took on responsibility for finding jobs for his followers, and they, in turn, returned their earnings to him. With those funds The Messenger paid for the rent, food, and living expenses. During this time, the group was growing slowly. Peninah, managed the house and prepared food for the group. At this time, or perhaps earlier as some sources suggest, The Messenger married Peninah despite his ban on marriage for his disciples. He stated that the marriage was spiritual and not sexual, as celibacy was required by the group’s moral code. It is not clear whether a marriage license was obtained. While living in New York, The Messenger decided to change his name once again. This time he assumed the name Major Jealous Devine, which was later abbreviated M.J. Devine. Subsequently, the name M.J. Devine evolved into Father Divine (2008).

In 1919, Father Divine and his group of approximately two-dozen moved to Sayville, Long Island, a predominantly white community. It was around this time that he declared that he was the Second Coming of the Christ (Baer and Singer 2002). The small group constituted the first African American presence in Sayville. They settled in a house at 72 Macon Street, whose ownership was listed in the name of Mrs Peninnah Divine, where they would remain for about ten years. Father Divine continued with his employment office and found jobs for his followers and other locals, while spending his time in various domestic pursuits, such as gardening. The neighborhood benefited from his services and seemed friendly, as the followers were quiet and followed strict moral codes. The community treated Father Divine with respect.

Throughout the 1920s, membership of the Peace Mission Movement increased steadily and began attracting white converts, with Father Divine providing both economic and spiritual security for his followers. Eventually, the movement obtained multiple hotels and other businesses. His followers refurbished the buildings and then worked for no wages, blacks and whites together, relying on Father Divine’s leadership. The beginning of the Great Depression and the increasing hardships that poor blacks faced provided an opportunity for Father Divine to advocate for his egalitarian heaven on Earth (Miller 1995). The Peace Mission Movement expanded to 150 “heavenly extensions;” Peace Mission gatherings were held in Canada, Australia, and several European countries. Membership in New York and Long Island peaked at 10,000 around this time. The Peace Mission drew members from the poor black community impacted by the Great Depression, white members who were attracted by the New Thought doctrines, and blacks who had participated in the Universal Negro Improvement Association before founder Marcus Garvey’s deportation in 1927. Watts (1995:85) estimates overall movement membership in the early 1930s as between 20,000 and 30,000.

Father Divine providing both economic and spiritual security for his followers. Eventually, the movement obtained multiple hotels and other businesses. His followers refurbished the buildings and then worked for no wages, blacks and whites together, relying on Father Divine’s leadership. The beginning of the Great Depression and the increasing hardships that poor blacks faced provided an opportunity for Father Divine to advocate for his egalitarian heaven on Earth (Miller 1995). The Peace Mission Movement expanded to 150 “heavenly extensions;” Peace Mission gatherings were held in Canada, Australia, and several European countries. Membership in New York and Long Island peaked at 10,000 around this time. The Peace Mission drew members from the poor black community impacted by the Great Depression, white members who were attracted by the New Thought doctrines, and blacks who had participated in the Universal Negro Improvement Association before founder Marcus Garvey’s deportation in 1927. Watts (1995:85) estimates overall movement membership in the early 1930s as between 20,000 and 30,000.

The movement grew locally as groups from Harlem and Newark traveled to Saysville to attend the elaborate banquets prepared atthe house. The meals were free to all who wanted to hear God speak, and each Sunday more people would visit. By 1930, hundreds of people were arriving by bus and automobile, which began to irritate the surrounding community. It was during the early  1930s that the group adopted the name “the International Peace Mission movement.” In 1934, Father Divine, who himself had created a type of communal socialism, forged a short-lived alliance with the Communist Party in the U.S. for a time after being impressed with its commitment to civil rights.

1930s that the group adopted the name “the International Peace Mission movement.” In 1934, Father Divine, who himself had created a type of communal socialism, forged a short-lived alliance with the Communist Party in the U.S. for a time after being impressed with its commitment to civil rights.

While the Peace Mission was growing and expanding, it did attract local opposition. The banquets, sermons, and hallelujahs at its meetings became louder as the movement grew, and the neighborhood began to appeal to the police. Initially, parking tickets were given to discourage attendance. The district attorney subsequently hired a female agent to work undercover at the house. She attempted to prove that Father Divine had sexual relations with females in the house, but was unable to find any evidence. Her ploy to seduce Father Divine also failed, as the official report she filed stated that he simply ignored her (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). A series of town meetings were convened, and a group of respected citizens from the community were chosen to visit Father Divine at the house to state their grievances. Father Divine simply argued politely that he and his group were a benefit to the community, and that they had done nothing illegal. A few days later, the police broke into the house and arrested Father Divine and eighty of his disciples.

Father Divine was indicted and brought to trial, with Lewis J. Smith as the presiding judge. The records make it clear that Smith, a white man, was hostile toward Father Divine. In fact, the judge canceled Father Divine’s bail, ensuring that he would remain in jail throughout the trial (Miller 1995). Father Divine was prosecuted for obstructing traffic and being a public nuisance, and the judge also claimed that Father Divine was a disruptive figure in the community and lacked ministerial credentials. He was sentenced to one year in jail and a fine of five hundred dollars. However, three days later the judge suddenly died from a heart attack. Father Divine is reported to have commented that “I hated to do it,” which only added to his legendary stature (West 2003). Father Divine appealed his case, and the appellate court overturned his conviction and sentence. Father Divine then reassumed his mission with enhanced popularity and status.

The movement became more politically active following the 1935 Harlem Riot, and i n January, 1936, the movement organized a convention with a political platform that incorporated the Doctrine of Father Divine. Divine then led a Peace Mission Movement in New York City under the “Righteous Government Platform” with the goal of gaining justice for blacks. The most important, immediate goal was to abolish lynching. In addition, the platform aimed to stop segregation, and increase government responsibility in this area. Later, in 1940, the Movement gathered 250,000 signatures on an anti-lynching petition. The movement’s political messages on race relations were both controversial and ahead of their time. Delegates also opposed school segregation and many of Franklin Roosevelt’s social programs, which they interpreted as “handouts.” Other planks called for the nationalization and government control of the major banks and industries in the U.S.

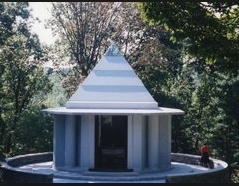

Peninah became ill in the late 1930s but appeared to have recovered before dying in the early 1940s  (the date is uncertain). Apparently, only a few of Father Divine’s inner circle knew of Peninah’s death, and she was quietly buried in an unmarked grave Father Divine never discussed her death, but in August 1946 he suddenly announced his marriage to a twenty-one year-old white follower, Edna Rose Ritchings, who was called Sweet Angel and had been one of his secretaries. Father Divine announced that Ritchings’ and Peninah’s spirits had joined together and thereby the two women had become one. Ritchings subsequently was known as Mother Divine within the movement. Father Divine once again emphasized that this marital union was spiritual and not sexual. This interracial marriage sparked public anger, shock among his followers, and some defections. However, she was accepted and revered within the movement. Father Divine and asserted that she was the incarnation of Peninah (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). The couple moved the headquarters to their current location, the Woodmont Estate, which is located outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1953. Mother Divine significantly aided Father Divine in managing the movement during her younger years, and as his health declined she took on many more duties.

(the date is uncertain). Apparently, only a few of Father Divine’s inner circle knew of Peninah’s death, and she was quietly buried in an unmarked grave Father Divine never discussed her death, but in August 1946 he suddenly announced his marriage to a twenty-one year-old white follower, Edna Rose Ritchings, who was called Sweet Angel and had been one of his secretaries. Father Divine announced that Ritchings’ and Peninah’s spirits had joined together and thereby the two women had become one. Ritchings subsequently was known as Mother Divine within the movement. Father Divine once again emphasized that this marital union was spiritual and not sexual. This interracial marriage sparked public anger, shock among his followers, and some defections. However, she was accepted and revered within the movement. Father Divine and asserted that she was the incarnation of Peninah (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). The couple moved the headquarters to their current location, the Woodmont Estate, which is located outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1953. Mother Divine significantly aided Father Divine in managing the movement during her younger years, and as his health declined she took on many more duties.

Father Divine died in 1965 and was interred in a mausoleum on the Woodmont property. After his death, Mother Divine assumed leadership of the movement but moved away from the more political beliefs and actions that had been Father Divine’s primary focus (Miller 1995). Following Father Divine’s death, the membership in the Peace Mission Movement decreased. However, the group showed little interest in  recruitment, preferring to preserve its elite status. The few hundred members scattered around the U.S. and Europe have continued to abide by the strict moral code that Father Divine instituted. A small number of members remain at Woodmont, aiding Mother Divine in giving tours of the property and performing day-to-day managerial duties (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). Mother Divine has generally been accepted as the incarnation of Father Divine, and has been treated as such, though his immortal spirit continues to be honored (Weisbrot 1995).

recruitment, preferring to preserve its elite status. The few hundred members scattered around the U.S. and Europe have continued to abide by the strict moral code that Father Divine instituted. A small number of members remain at Woodmont, aiding Mother Divine in giving tours of the property and performing day-to-day managerial duties (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). Mother Divine has generally been accepted as the incarnation of Father Divine, and has been treated as such, though his immortal spirit continues to be honored (Weisbrot 1995).

While Peace Mission membership has continued to dwindle and properties have been sold off since Father Divine’s death, there have been recent efforts to restore some of the movement’s famous landmarks. The Divine Lorraine hotel was recently purchased and is now being refurbished. It had been sitting unoccupied on Broad Street in Philadelphia for years, but work is underway to remove the graffiti and to restructure the interior of the building. The firm that purchased the property has stated that it hopes to operate a hotel in on the premises, a tribute to the movement and the lively culture it brought to the city (Bloomwuist 2014).

Mother Divine died on March 4, 2017 at Woodmont at age ninety-two (Grimes 2017). There subsequently has been legal contestation of the estate and property ownership.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Peace Mission Movement has roots in Christianity, with a strong emphasis on the New Thought stand of that tradition.  Members were taught that they possessed an inner divinity and that Christ was present in every part of every individual’s body. Father Divine was heavily influenced by writings of Robert Collier that advocate for a universal potential in humans, and that success can be realized through the use of their inner divinity. Father Divine focused on the self-image of members. A righteous individual is one with God and this requires positive thinking and an affirmative self-image. Father Divine stated, “The positive is a reality! We dispel the negative and the undesirable…” (Erikson 1977). This positive way of thinking brings the follower closer with God, and closer to the truth. Father Divine purchased copies of New Thought works and gave them to his disciples (Watts 1995). Many white followers were attracted to his movement by the New Thought teachings. Required reading for members included both the Bible and the Divine newspapers, until their publication was discontinued in 1992.

Members were taught that they possessed an inner divinity and that Christ was present in every part of every individual’s body. Father Divine was heavily influenced by writings of Robert Collier that advocate for a universal potential in humans, and that success can be realized through the use of their inner divinity. Father Divine focused on the self-image of members. A righteous individual is one with God and this requires positive thinking and an affirmative self-image. Father Divine stated, “The positive is a reality! We dispel the negative and the undesirable…” (Erikson 1977). This positive way of thinking brings the follower closer with God, and closer to the truth. Father Divine purchased copies of New Thought works and gave them to his disciples (Watts 1995). Many white followers were attracted to his movement by the New Thought teachings. Required reading for members included both the Bible and the Divine newspapers, until their publication was discontinued in 1992.

While Father Divine was influenced by Christian theology, and New Thought in particular, he departed from Christian doctrine in a number of ways. For example, early in the Movement, Father Divine rejected the notion of an afterlife in Christian eschatology and advocated for creating an egalitarian heaven on Earth. In this regard, Father Divine was reverential toward America, which he referred to as the “Kingdom of God,” and expected his followers to identify themselves as Americans. He regarded the nation’s founding documents (the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the Constitution) to be divinely inspired. The basic principles in these documents resonated with the primary tenet of the Peace Mission Movement, equality and brotherhood among all people. Everyone should be granted the same dignity and respect irrespective of their race or social background. He defined English as “the universal language,” and children were taught only in English (Watts 1995). Father Divine downplayed Africa and the black heritage, despite the fact that some of his followers took pride in this heritage.

Creating the egalitarian heaven on earth that Father Divine envisioned required a rejection of some important aspects of human nature. A disavowal of these things, Father Divine taught, created a purity of the body and soul and allowed God to enter a follower’s consciousness. Once this presence was recognized, the follower would act and think differently, with a new personality. There would be a spiritual awakening that would result in an “immortal soul” reborn from the old soul (Erikson 1977). With this consciousness, earthly success was possible and would be experienced.

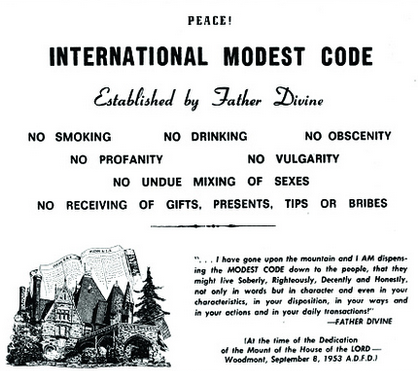

The centerpiece of Father Divine’s moral code was the International Modest Code. The code specifically banned smoking, drinking, obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, undue mixing of the sexes, and receiving gifts, presents or bribes. The restrictions on men and women were stringent. Women were not to wear slacks or short skirts and men short-sleeves. Those who stayed at the hotels owned by the Movement, such as the Divine Lorraine, were asked to abide by the code, which was said to prompt “modest, independence, honesty, and righteousness” (Primiano 2013). A plaque was posted in each room containing the rules and regulations. Guests were separated by gender. Although times have changed, the rules for modest dress remained important up until the closing of the Divine Lorraine in 1999. Women were asked to avoid wearing pants, short skirts, bare midriffs, halters, and low cut necklines, and hair curlers. Men could not wear hats, sleeveless shirts, or untucked shirts. A plaque was posted in each room stating the rules and regulations (Primiano 2013). More significantly both for members and the future of the movement, men and women were required to remain celibate. This mandate was gradually extended from Father Divine’s inner circle to all serious followers. Father Divine taught that humans born as a product of sexual intercourse were “born wrong” and that learning how not to be born was the key to learning how not to die (Black n.d.). In stipulating this code of conduct, Father Divine taught that there was no small crime, and that all crimes stem from the same evil impulses (Weisbrot 1995).

obscenity, vulgarity, profanity, undue mixing of the sexes, and receiving gifts, presents or bribes. The restrictions on men and women were stringent. Women were not to wear slacks or short skirts and men short-sleeves. Those who stayed at the hotels owned by the Movement, such as the Divine Lorraine, were asked to abide by the code, which was said to prompt “modest, independence, honesty, and righteousness” (Primiano 2013). A plaque was posted in each room containing the rules and regulations. Guests were separated by gender. Although times have changed, the rules for modest dress remained important up until the closing of the Divine Lorraine in 1999. Women were asked to avoid wearing pants, short skirts, bare midriffs, halters, and low cut necklines, and hair curlers. Men could not wear hats, sleeveless shirts, or untucked shirts. A plaque was posted in each room stating the rules and regulations (Primiano 2013). More significantly both for members and the future of the movement, men and women were required to remain celibate. This mandate was gradually extended from Father Divine’s inner circle to all serious followers. Father Divine taught that humans born as a product of sexual intercourse were “born wrong” and that learning how not to be born was the key to learning how not to die (Black n.d.). In stipulating this code of conduct, Father Divine taught that there was no small crime, and that all crimes stem from the same evil impulses (Weisbrot 1995).

Father Divine was a proponent of capitalism, and the movement owned and operated a network of businesses. At the same time, he was a strong advocate for self-reliance, which led him to oppose a variety of common economic practices. He strongly distrusted the banking system and encouraged his followers not to deposit their money in banks. Followers were to use cash in making personal purchases, never credit. They were forbidden to take out insurance policies, as doing so demonstrated mistrust in God, and life insurance was to be canceled. They were not to take out any loans and were to pay off any existing debts. In addition, individuals were not allowed to receive welfare, as Father Divine largely advocated for self-help, and for his followers to trust deeply in him. Similarly, business owners within the movement accepted only cash, did not accept tips, and, consistent with the group’s moral code, did not sell alcohol or tobacco (Watts 1995).

Father Divine’s spiritual status continued to rise through his life. He began as the Messenger, and around 1920 began to refer to himself as the second coming of Christ. At various times he alluded to himself as God, but it was in 1951 that he clearly made this declaration. He stated that “I have personified myself, Almighty God!” (Erikson 1977). He later defined God as “God is not only personified and materialized. He is repersonified and rematerialized. He rematerialized and He rematerialates. He rematerialates and He is rematerializatable. He repersonificates and He repersonifitizes” (Watts 1995). He described this process in the following way: “Condescendingly I came as an existing Spirit unembodied, until condescendingly inputting MYSELF in a Bodily form in the likeness of men I came, that I might speak to them in their own language, coming to a country that is supposed to be the Country of the Free, where mankind is privileged to serve GOD according to the dictates of his own conscience” (Watts 1995: 177-78 ). He seemed to believe, and led his followers to believe, that he was immortal and would not die physical or spiritually. However, after the first generation of followers had passed, the movement altered some of its views on death and the afterlife. Nonetheless, they continued to consider Father Divine to be immortal and to still live in spirit. They have expressed this belief by leaving a place at the table for him at the communion and wedding anniversary banquet (Weisbrot 1995).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The Peace Mission holds regular church services on Sundays that involve singing of hymns and songs, reading from scripture, playing recordings of sermons by Father Divine, words from Mother Divine, and sermons from other countries or from visitors. The services do not include donations or offertory (International Peace Mission Movement n.d.).

A central ritual in the Peace Mission Movement is the large, elaborate Communion Banquets that Father Divine began holding  during the Great Depression to provide free meals to his followers. There were, and still are, multiple courses served by waiters. Father Divine blessed each dish before it was served. The large gatherings and various courses called for a lengthy dinner that incorporated joyful songs by the different choruses in attendance. At the end of the dinner celebration, Father Divine would stand and give his sermon. The audience would respond with exuberant shouting, jumping, and crying. These banquets, given weekly, were a sign of Father Divine’s charity as well as his wealth. To his followers, the banquets signified his support and his kindness, and they drew many people to him. These banquets are still hosted by the small groups that remain active (Schaefer and Zellner 2008).

during the Great Depression to provide free meals to his followers. There were, and still are, multiple courses served by waiters. Father Divine blessed each dish before it was served. The large gatherings and various courses called for a lengthy dinner that incorporated joyful songs by the different choruses in attendance. At the end of the dinner celebration, Father Divine would stand and give his sermon. The audience would respond with exuberant shouting, jumping, and crying. These banquets, given weekly, were a sign of Father Divine’s charity as well as his wealth. To his followers, the banquets signified his support and his kindness, and they drew many people to him. These banquets are still hosted by the small groups that remain active (Schaefer and Zellner 2008).

In addition to the large Communion Banquets, the marriage between Father Divine and Mother Divine is celebrated each year on April 29 as an “international, interracial, universal holiday.” The anniversary symbolizes for followers the “Marriage of Christ to his Church” and the “fusion between heaven and Earth.” Members gather at the Woodmont estate to share the largest and most exciting banquet of the year ( Schaefer and Zellner 2008).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

In the earlier years of the movement, committed members of the Peace Mission either lived communally or with other followers. The other main group lived at home but attended church services and events. Father Divine believed that having the members live in integrated spaces among each other enhanced their closeness with him, and encouraged the equality that he preached. In the original communal houses that Father Divine owned and ran, he provided employment services for the community. Members would turn their wages over to him in exchange for food, housing, and other support. Since Father Divine’s death, membership has dwindled. However, a few groups in the U.S. and overseas remain active, including the group located on the Woodmont estate with Mother Divine (Schaefer and Zellner 2008).

Following the moral code that Father Divine instituted involved a strong commitment to the movement and a strict behavioral code on a number of matters. The movement discouraged marriage, along with “excessive” mingling of the sexes. In the “Heavens” and other living spaces the movement maintained, men and women were kept separate.

When families arrived at the communal houses, family members (husbands and wives, brothers and sisters) were separated and had limited contact. Children were assigned to substitute parents (West 2003; International Peace Mission Movement n.d.). Prior friendships also were abandoned, and contact with outsiders was minimized. Father Divine sought a spiritual family consisting of all his disciples with himself as the head and parent. Although Father Divine rejected marriage and required celibacy of members, he himself was married twice. He professed that both relationships were spiritual and not sexual. Indeed, Mother Divine was regarded within the movement as the “Spotless Virgin.”There were also financial constraints as well. Members were instructed to avoid banks and insurance policies, and loans; use only cash and avoid credit and debt; or to accept welfare.

Racial integration was actively promoted within the movement, and integration at all movement events was mandatory. Black followers were to change their names, as the old names symbolized mortality, as well as being the names of their ancestor’s slave masters (Watts 1995). Likewise, Father Divine promoted gender equality, and women assumed a variety of traditionally male jobs.

Under Father Divine’s leadership, the Peace Mission was politically active and publically advocated for equality and desegregation, as well as anti-lynching laws and further government involvement during the Great Depression. Father Divine led movements and events in New York with his followers. Although Father Divine and the movement participated in meetings and parades with the Communist Party USA, the movement would not be active in the Civil Rights Movement that occurred years later. During the Red Scare, Father Divine took a more anti-communist stance. Later, Mother Divine did not continue his political activity, and the movement became much less politically involved.

as well as anti-lynching laws and further government involvement during the Great Depression. Father Divine led movements and events in New York with his followers. Although Father Divine and the movement participated in meetings and parades with the Communist Party USA, the movement would not be active in the Civil Rights Movement that occurred years later. During the Red Scare, Father Divine took a more anti-communist stance. Later, Mother Divine did not continue his political activity, and the movement became much less politically involved.

The Peace Mission established three auxiliary groups: the Rosebuds, the LilyBuds, and the Crusaders. The Rosebuds is a group for young girls and women, the LilyBuds is for middle to older aged women, and the Crusaders is for boys and men of all ages. Each group has a characteristic uniform and creed, with brightly colored clothes to distinguish them from the rest of the disciples. These orders operate as different choirs, leading and performing various hymns at services and events. Under Father Divine, about half of all disciples were members of one of the auxiliary groups (Weisbrot 1995). The movement also supported two publications: The Spoken Word (1934–1937) and the New Day (1936–1989). Both were available to members and the general public. These publications contained articles on issues of the day as well as world and local events.

auxiliary groups (Weisbrot 1995). The movement also supported two publications: The Spoken Word (1934–1937) and the New Day (1936–1989). Both were available to members and the general public. These publications contained articles on issues of the day as well as world and local events.

Before his death in 1965, Father Divine was the unchallenged leader of the Peace Mission. Other heavenly extensions had their own directors, but the divinity of Father Divine made him as the spiritual guide for the movement. The movement owned a number of businesses, including hotels, restaurants, and clothing shops. Members rather than Father Divine usually held the deeds on property, and members were able to live in movement owned properties inexpensively. Father Divine did not receive a personal salary. However, since members returned their salaries to Father Divine, was able to live well and to host the lavish banquets for which the movement became famous. After Father Divine’s death, Mother Divine and her staff were supported by the Peace Mission and its businesses.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Peace Mission faced a variety of challenges throughout its history. For example, early in the movement’s history Father Divine faced arrest in Georgia as local ministers organized in opposition to his teachings and as local residents opposed the ever growing size of the audience attending his Sunday services. In another incident, public uneasiness with the movement increased when the young daughter of two members died after refusing medical attention in favor of faith in Father Divine (Watts 1995). A financial dispute occurred when a Peace Mission couple, Thomas and Verinda Brown, sought return of money they had given the movement after they decided, in violation of Peace Mission rules, that they wanted to live together. The case resulted in a law suit in which the Browns were victorious, but Father Divine moved the Peace Mission from New York to Philadelphia, outside of the court’s jurisdiction, in order to avoid paying the required settlement. While he was successful in this regard, the move also separated him from his primary recruitment base. Black Nationalists were critical of the Peace Mission as they regarded his mandate of celibacy as racial suicide if widely adopted.

Given that the Peace Mission advocated celibacy, lived communally, divided married couples who joined the movement while Father Divine was married twice in what he deemed “spiritual marriages,” it is not surprising that the sexual practices of the Peace Mission were of considerable interest. Father Divines marriage to Mother Divine, fifty years his junior and white, was scandalous during that period. One sexual abuse scandal that occurred with the movement involved an illicit sexual relationship between an adult Peace Mission member, John Hunt, who took seventeen year-old Delight Dewett across state lines for “immoral purposes” after she came to believe that she was to be the Virgin Mary and mother of the next redeemer. Although Father Divine castigated Hunt and supported his criminal conviction, public suspicion of the movement and negative publicity increased.

Mission were of considerable interest. Father Divines marriage to Mother Divine, fifty years his junior and white, was scandalous during that period. One sexual abuse scandal that occurred with the movement involved an illicit sexual relationship between an adult Peace Mission member, John Hunt, who took seventeen year-old Delight Dewett across state lines for “immoral purposes” after she came to believe that she was to be the Virgin Mary and mother of the next redeemer. Although Father Divine castigated Hunt and supported his criminal conviction, public suspicion of the movement and negative publicity increased.

The most sensational dispute involving Father Divine directly was with Peace Mission member, Faithful Mary (Black n.d.; Watts 1995). After what began as a financial dispute, Faithful Mary formed a sectarian offshoot movement, the Universal Light Movement, which attracted a number of Peace Mission members. Faithful Mary subsequently authored a book, “God”: He’s Just a Natural Man (1937) accusing Father Divine of financial corruption and slave-like working conditions. The most inflammatory accusations, however, were that there was ongoing sexual activity between disciples, sexual orgies, and homosexuality in Peace Mission communal living quarters. She directly accused Father Divine of personally having sexual relationships with his younger female followers, including her. She wrote that “He regularly seduced other, young female disciples, getting them to come to his quarters late at night, individually or in small groups. When they were either partially or fully naked, he would masturbate them to orgasm, all while telling them that they were not sinning but giving themselves to God.” Despite the acrimonious relationship with Father Divine, Faithful Mary subsequently returned to the Peace Mission after her schismatic movement collapsed. Nonetheless, Black (n.d.) notes that “Although the Peace Mission was at its apex, the public revelations about its sordid sexual underpinnings led credence to the suspicion that the movement was a Black-led White sex slavery cult which lured people in, took all their money, and brainwashed its gullible followers. The scandal took their [sic] toll.”

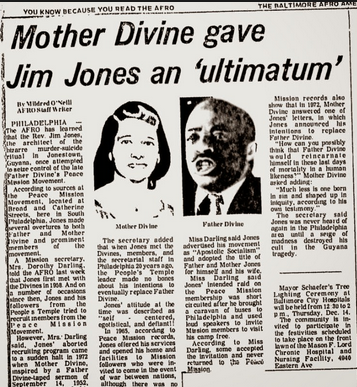

Finally, the Peace Mission became involved in a controversy with Jim Jones, founder of the Peoples Temple. Jim Jones was deeply  influenced by Father Divine (Hall 1987). He visited Father Divine in Philadelphia multiple times during the 1950s, and Divine was welcoming and warm to Jones. Both Jones and Divine had roots in Pentecostalism, advocated for racial equality and promoted an integrated church. Jones found appeal in Father Divine’s claim of his own divinity, the idea of being the “Father” within the movement, the message of the inner divinity of all humans, the promised land theme that would allow an escape from poverty and repression. Early in Jim Jones career, he modeled activities after Father Divine’s Peace Mission. He instituted a church adoption fund, which, like Father Divine’s endeavors, was funded through church dinners and businesses; opened a free social service and meals center in the Peoples Temple basement that gave away thousands of meals each month, as well as encouraging integration; and established a free grocery store, gave away clothing, and provided other social services. At the same time, Father Divine and Jim Jones took separate paths on other matters. Jones advocated socialism as the answer to most of America’s problems, while Father Divine championed Black capitalism (Chidester 1988).

influenced by Father Divine (Hall 1987). He visited Father Divine in Philadelphia multiple times during the 1950s, and Divine was welcoming and warm to Jones. Both Jones and Divine had roots in Pentecostalism, advocated for racial equality and promoted an integrated church. Jones found appeal in Father Divine’s claim of his own divinity, the idea of being the “Father” within the movement, the message of the inner divinity of all humans, the promised land theme that would allow an escape from poverty and repression. Early in Jim Jones career, he modeled activities after Father Divine’s Peace Mission. He instituted a church adoption fund, which, like Father Divine’s endeavors, was funded through church dinners and businesses; opened a free social service and meals center in the Peoples Temple basement that gave away thousands of meals each month, as well as encouraging integration; and established a free grocery store, gave away clothing, and provided other social services. At the same time, Father Divine and Jim Jones took separate paths on other matters. Jones advocated socialism as the answer to most of America’s problems, while Father Divine championed Black capitalism (Chidester 1988).

Jones’ interest and admiration for Father Divine culminated in his 1971 trip to Philadelphia, as part of the summer bus tours that sought out converts across the country. Jones attempted to target the Peace Mission followers still in Philadelphia after the death of Father Divine. Jones claimed to be a reincarnation of Father Divine. He hoped to bring converts back to California. However, he was met with an angry Mother Divine, who stated publicly “We have entertained Pastor Jones and the People’s Temple. We were entertaining angels of the other fellow! We no longer extend to them any hospitality whatsoever…They are not welcome!” (Hall 1987).

The Peace Mission peaked during the 1930s amid the poverty and unemployment of the Great Depression and the movement’s advocacy for equality for African Americans. Ultimately, the movement faced an almost certain demise due to Father Divine’s policies of not recruiting new members and the requirement of celibacy. Membership in the movement continued to dwindle after Father Divine’s death. Only a few hundred members remained, and, fewer than two dozen lived with Mother Divine at Woodmont (Blaustein 2014). The small group of aging followers “…spent their days preparing for the Holy Communion banquet,”….“They grow their own food. They bake their own bread. They polish the silver. Each day is filled with actions to prepare for the sacred meal” (Blaustein 2014).

With Mother Divine’s passing and the even smaller number of core followers at Woodmont, the future of the movement remains uncertain. In the wake of Mother Divine’s death, a struggle for control of the estate and remaining property ensued. Tommy Garcia, born to one of Father Divine’s followers and raised as Father Divine’s adopted son, has laid claim to the movement’s property and money. Garcia left Woodmont when he was fifteen years-old. His claims have been rejected by the movement, and no final legal determination has been made (Pirro 2017; Blookquist 2009).

REFERENCES

Baer, Hans A. and Merril Singer. 2002. African American Religion. Knoxville, TN: Uniersity of Tennessee Press.

Black, E. n.d. “Jonestown and Woodmont: Jim Jones, Mother Divine and the Fulfillment of Father Divine’s Intention of a Vanishing Divine City.” Accessed from http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=40227 on 15 July 2014.

Blaustein, Jonathan. 2014. “Philadelphia, City of Father Divine.” New York Times, December 29. Accessed from http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/12/29/philadelphia-city-of-father-divine/?_r=0# on 3 March 2015.

Bloomquist, Sarah. 2014. “Redevelopment Underway at the Divine Lorraine Hotel.” ABC 6 Action News. Accessed from http://6abc.com/realestate/redevelopment-underway-at-the-divine-lorraine-hotel/96154/ on 10 June 2014.

Bloomquist, Sarah. 2009. “Father Divine and the International Peace Movement.” 6abc.com, October 16. Accessed from https://6abc.com/news/father-divine-and-the-international-peace-movement/1789153/ on 20 March 2019.

Chidester, David. 1988. Salvation and Suicide: An Interpretation of Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Erickson, Keith V. 1977. “Black Messiah: The Father Divine Peace Mission Movement.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 63:428-38.

Faithful Mary. 1937. “God”: He’s Just a Natural Man.” Philadelphia: Universal Light.

Grimes, William. 2017. “Mother Divine, Who Took Over Her Husband’s Cult, Dies at 91.” New York Time, March 14. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/14/us/mother-divine-dead-peace-mission-leader.html on 20 March 2019.

Hall, John R. 1987. Gone From the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction.

Pirro, J.F. 2017. “The Adopted Son of a Peace Mission Leader Returns to Gladwyne.” Mainline Today, August. Accessed from http://www.mainlinetoday.com/Main-Line-Today/August-2017/The-Adopted-Son-of-a-Peace-Mission-Leader-Returns-to-Gladwyne/ on 20 March 2019.

Primiano, Leonard N. 2013. “Father Divine: Still Looking Over Philadelphia” Essayworks. Accessed from http://www.newsworks.org/index.php/local/speak-easy/51031-father-divine-still-looking-over-philadelphia on 10 June 2014.

Satter, Beryl. 2012. “Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement.” Pp. 386-87 in The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Social History , edited by Lynn Dumenil, Lynn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schaefer, Richard T. and William W. Zellner. 2008. “The Father Divine Movement.” Pp. 239-78 in Extraordinary Groups: An Examination of Unconventional Lifestyles. New York: Worth Publishers.

Watts, Jill. 1995. God, Harlem U.S.A.: The Father Divine Story. Berkley: University of California Press.

West, Sandra L. 2003. “Father Divine.” Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. Accessed from http://www.fofweb.com/History/MainPrintPage.asp?iPin=EHR0116&DataType=AFHC&WinType=Free on 10 June 2014.

Weisbrot, Robert. 1995. “Father Divine’s Peace Mission Movement.” Pp. 285-90 in America’s Alternative Religions, edited by Timothy Miller. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Weisbrot, Robert. 1983. Father Divine: The Utopian Evangelist of the Depression Era Who Became an American Legend. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Publication Date:

18 July 2014

FATHER DIVINE PEACE MISSION VIDEO CONNECTIONS