ALLIANCE FOR THERAPEUTIC CHOICE AND

SCIENTIFIC INTEGRITY TIMELINE

1992 (March): The National Association for Psychoanalytic Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH) was founded.

1992 (December 18): The organizing committee of NARTH, with twenty-three members, met at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.

1992: The World Health Organization removed homosexuality from the International Classification of Diseases.

1993 (May 20): NARTH held its first annual conference in San Francisco.

1997: NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the Hawaii Supreme Court to oppose legalizing same-sex marriage.

2000 (May 17): NARTH and several ex-gay ministries published a full-page newspaper ad in USA Today and held a press conference in Chicago to protest the American Psychiatric Association’s cancellation of a debate on therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation.

2001: Evangelical Christian psychologist James Dobson of Focus on the Family declared NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi to be the “foremost expert on homosexuality.”

2002: NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the Kansas Supreme Court, which ruled that a “transsexual” is not a woman, voiding her marriage and inheritance.

2003: Psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, who advocated in 1973 to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder, published a study based on participants recruited through NARTH and Exodus International, that concluded sexual orientation change is possible.

2005 (December 25): NARTH co-founder Charles Socarides died.

2009: Reacting to NARTH and others promoting the belief that homosexuality is a disorder and sin that can be changed through therapy and religious interventions, the American Psychological Association evaluated the peer-reviewed research literature on sexual orientation change efforts and found no scientific evidence to support their efficacy.

2009: NARTH established the Journal of Human Sexuality.

2010: NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the California Supreme Court to oppose legalizing same-sex marriage.

2010: George Rekers resigned from NARTH’s Scientific Advisory Board after a newspaper reported that he hired a male escort to accompany him on a trip to Europe.

2010: NARTH Executive Secretary Arthur Goldberg resigned from NARTH after it was publicly revealed that he served time in federal prison for conspiracy to commit fraud.

2012: Robert Spitzer repudiated and sought to retract his 2003 study, saying it was flawed. He also apologized for the harm it caused.

2012: NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the U.S. Supreme Court to uphold the Defense of Marriage Act.

2012: California became the first state to ban conversion therapy with minors.

2012: Exodus International removed NARTH materials from its website. Exodus President Alan Chambers renounced reparative therapy.

2012: NARTH lost its tax-exempt status.

2013: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the constitutionality of California’s ban on conversion therapy with minors.

2013: The World Medical Association released a statement condemning “so-called ‘conversion’ or ‘reparative’ methods.”

2013: The American Psychiatric Association removed “Gender Identity Disorder” from the DSM and replaced it with “Gender Dysphoria.”

2014: NARTH leaders rebranded the organization as the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity and established “the NARTH Institute” as one of its divisions.

2014: Members of The United Nations Committee against Torture expressed concern about conversion therapy on youth in the United States.

2015 (June 1): The Office of the United Nations Commissioner for Human Rights issued a report calling for all nations to ban “conversion therapies.”

2015 (June 25): Jews Offering New Alternatives to Homosexuality (JONAH) lost a consumer fraud civil lawsuit brought by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

2015 (August): The American Bar Association adopted a resolution urging legislation to prohibit conversion therapy on minors.

2015 (October): NARTH co-founder Benjamin Kaufman relinquished his medical license amid allegations of gross negligence and unprofessional conduct.

2017 (March 8): NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi died.

2017 (May 1): The U.S. Supreme Court rejected a challenge to California’s law banning conversion therapy with minors.

2018-2019: Joseph Nicolosi, Jr. trademarked “reparative therapy” and “reintegrative therapy,” in 2018 and 2019 respectively.

2019: Retailer Amazon.com announced a decision to stop selling books on conversion therapy.

2020: The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit invalidated two ordinances in Florida (the city of Boca Raton and Palm Beach county) that banned conversion therapy with minors based on “free speech.”

2021: The American Psychological Association adopted a resolution opposing gender identity change efforts and another strengthening its stance against sexual orientation change efforts.

2021: For the first time, legislation to protect conversion therapy was introduced in a few states.

2022: More than half of the states and several U.S. cities had some form of conversion therapy ban, by statute or regulation.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity (ATCSI) is “a multi-disciplinary professional and scientific organization” headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is

dedicated to preserving the right of individuals to obtain the services of therapists and medical professionals who honor the clients’ values; advocating for integrity and objectivity in social science research; and ensuring that competent licensed professional assistance is available for persons who experience unwanted same-sex erotic attractions or who experience conflict between their biological sex and perceived gender identity (ATCSI 2022).

Its motto is “Because your values matter.”

ATCSI was originally founded as a scientific, professional organization under a different name in March of 1992 by Charles Socarides, Joseph Nicolosi, and Benjamin Kaufman (NARTH Bulletin 1993a, Kaufman 2001-2002). The organizing committee of NARTH, with twenty-three members, met at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City. Twenty-three members attended (NARTH Bulletin 1993a). Its founders, religiously conservative mental health professionals, created the organization to protect and advocate for the interests of licensed psychotherapists to offer sexual orientation and/or gender identity “conversion therapies.” Conversion therapists were gradually marginalized in the U.S. mental health professions (Drescher 2015a; Kaufman 2001-2002) in the years following the 1973 American Psychiatric Association decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. In response to threat of a lawsuit (Isay 1996), the American Psychoanalytic Association became the last major mental health professional organization to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation in the training of psychoanalysts (Drescher 2015a). This was the catalyst for creating NARTH.

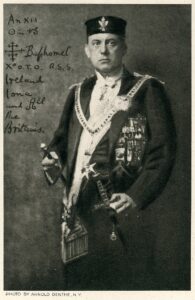

ATCSI was originally named the National Association for Psychoanalytic Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (Socarides and Kaufman 1994). It was renamed the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality [Image at right] the same year. The organization existed as NARTH  until it rebranded as ATCSI in 2014. It is one of the most influential partners in the transnational conversion ministry movement and the anti-LGBT Christian Right (Moss 2021, Robinson and Spivey 2019), both of which were inaugurated during the 1970s. The founders attempted to establish NARTH as a scientific association and promote therapy as an effective method for treating homosexuality, which they viewed as a gender identity disorder (Bennett 2003, Robinson and Spivey 2007). To date, the organization’s legacy includes revitalizing the market for conversion therapy and developing a global advocacy network for its practitioners. For many years, NARTH also rendered some credibility for its two major partners, the ministry networks that promise the possibility of change and Christian political groups opposed to LGBT rights.

until it rebranded as ATCSI in 2014. It is one of the most influential partners in the transnational conversion ministry movement and the anti-LGBT Christian Right (Moss 2021, Robinson and Spivey 2019), both of which were inaugurated during the 1970s. The founders attempted to establish NARTH as a scientific association and promote therapy as an effective method for treating homosexuality, which they viewed as a gender identity disorder (Bennett 2003, Robinson and Spivey 2007). To date, the organization’s legacy includes revitalizing the market for conversion therapy and developing a global advocacy network for its practitioners. For many years, NARTH also rendered some credibility for its two major partners, the ministry networks that promise the possibility of change and Christian political groups opposed to LGBT rights.

No major mental health professional organization has ever recognized NARTH as a scientific organization. NARTH has repeatedly been described as pseudo-scientific (Cianciatto and Cahill 2006, Drescher 2015a, Ford 2001, Haldeman 1999, Panozzo 2013) and accused of distorting and misusing scholars’ research (Besen 2003, ILGA World and Mendos 2020, Robinson and Spivey 2015, Waidzunas 2015, Williams 2011). Beginning in 1992, major professional health organizations began to publish position statements and resolutions opposing attempts to change sexual orientation (NASW 1992), and later, gender identity (NASW 2015), citing the absence of scientific support, among other concerns (see Shidlo, Schroeder, and Drescher 2001). In 1992, the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from the International Classification of Diseases, a diagnostic tool used around the world for reimbursement systems in health care. Today, all prominent professional mental health and medical associations “reject ‘conversion therapy’ as a legitimate medical treatment” (AMA 2019) to change sexual orientation or gender identity as well as the etiologies on which they are based (APA 2021a, APA 2021b).

Several scholars have questioned or disputed NARTH’s claim to be a secular organization (Alumkal 2017; American Psychiatric Association 2000; Besen 2003; Burack and Josephson 2005; Clucas 2017; Drescher 1998, 2015; Grace 2008; Haldeman 1999; ILGA World and Mendos 2020; Queiroz, D’Elio and Maas 2013; Robinson and Spivey 2007, 2019). Beverley’s (2009) Illustrated Guide to Religions lists NARTH as an organization that is critical of pro-gay theology. Psychologist John Gonsiorek (2004:758) referred to conversion therapy as “theocracy in scientistic drag.” Jurist Craig Konnoth (2017:283) argued that conversion therapy is “quintessentially a form of religious practice.” Scholars (Babits 2019, Martin 1984) have documented the central role of religion in conversion therapies since the early twentieth century. Religion itself remains the “primary driving force that perpetuates” conversion therapy in the U.S. and globally (Horne and McGinley 2022:221).

Although NARTH was neither established as nor officially affiliated with a religious organization, religion has been essential to the work and vitality of the organization and its leaders throughout its thirty-year history. Despite  repeated assertions found in NARTH’s literature and by its representatives that NARTH is not a religious organization, NARTH’s newsletter, conference presentations, journals, and website promote socially conservative religious beliefs and practices. Religion is the keystone on which the vocation and professional work of conversion therapists depend, since most clients who seek therapy do so based on moral or religious conflicts related to their own or their children’s sexuality or gender (Flentje, Heck and Cochran 2013; Haldeman 2022; Nicolosi and Nicolosi 2002; Rosik 2014; Spivey and Robinson 2010; Streed, Anderson, Babits and Ferguson 2019).

repeated assertions found in NARTH’s literature and by its representatives that NARTH is not a religious organization, NARTH’s newsletter, conference presentations, journals, and website promote socially conservative religious beliefs and practices. Religion is the keystone on which the vocation and professional work of conversion therapists depend, since most clients who seek therapy do so based on moral or religious conflicts related to their own or their children’s sexuality or gender (Flentje, Heck and Cochran 2013; Haldeman 2022; Nicolosi and Nicolosi 2002; Rosik 2014; Spivey and Robinson 2010; Streed, Anderson, Babits and Ferguson 2019).

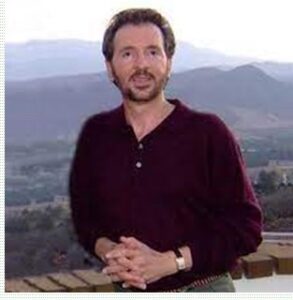

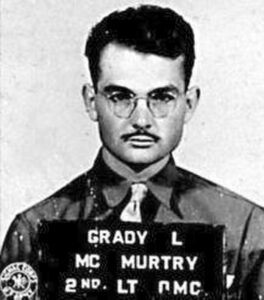

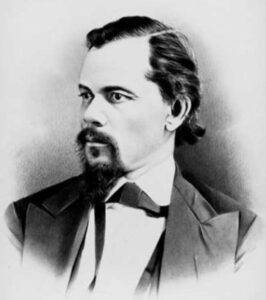

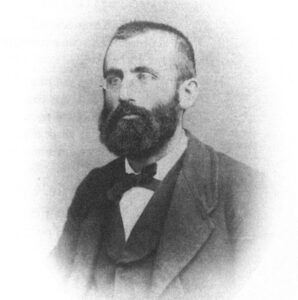

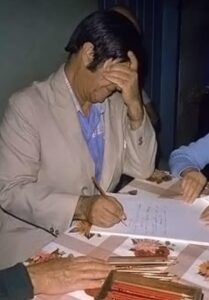

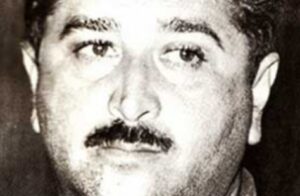

The organization’s founders were religious conservatives. Joseph Nicolosi, [Image at right] a Roman Catholic who served as the organization’s first executive director, was a psychologist and consultant for the Los Angeles Catholic Archdiocese (Christianson 2005) prior to co-founding NARTH and consistently integrated religion into his psychotherapy practice  with clients (Nicolosi 1991, 2001, 2012). For many years, NARTH was headquartered at Nicolosi’s Thomas Aquinas Psychological Clinic. Charles Socarides, [Image at right] a psychiatrist who served as the organization’s first president, was one of the most vocal opponents of the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. In a magazine published by the Jesuits of the United States, Socarides described his clinical work with homosexual men as “…a kind of ‘pastoral care’…. many of us thought we were quietly doing God’s work” (Socarides 1995). He called the idea, found in some pro-gay literature, that God made people gay “blasphemy.” Benjamin Kaufman was a Jewish psychiatrist (Thorn 2015) who served as the organization’s first vice-president.

with clients (Nicolosi 1991, 2001, 2012). For many years, NARTH was headquartered at Nicolosi’s Thomas Aquinas Psychological Clinic. Charles Socarides, [Image at right] a psychiatrist who served as the organization’s first president, was one of the most vocal opponents of the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. In a magazine published by the Jesuits of the United States, Socarides described his clinical work with homosexual men as “…a kind of ‘pastoral care’…. many of us thought we were quietly doing God’s work” (Socarides 1995). He called the idea, found in some pro-gay literature, that God made people gay “blasphemy.” Benjamin Kaufman was a Jewish psychiatrist (Thorn 2015) who served as the organization’s first vice-president.

Early in NARTH’s first decade, its officers intentionally developed working partnerships with several established “ex-gay” Christian networks, which had already begun to incorporate psychoanalytic etiologies of homosexuality and “transsexuality” into their ministries, based on the teachings of two theologians, Leanne Payne and Elizabeth Moberly (Ford 2001, Robinson and Spivey 2007, 2019). In its first year, NARTH established a leadership structure, which included “Liaison with Religious and Ex-Gay Ministries.” “Mr. and Mrs. Bill Grasso and Rev. Tom Mullen” first served in these roles (NARTH 1993a). In 1993, NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi spoke as a psychologist in a video titled “Choosing to Change from Homosexuality,” sold by the largest ex-gay ministry Exodus International, an evangelical Christian organization. The video featured Exodus president Joe Dallas and religious testimonies of change. Bob Davies, former executive director of Exodus, acknowledged that the organization worked with NARTH to help Exodus boost its credibility (Davies 1998). Randy Thomas, former executive vice-president of Exodus, revealed in a recent documentary that “There was a symbiotic relationship between our need for credibility and then, of course, the therapists who get clients. Our networks were infused with their books… teachings… and therapeutic approach. It sounds awful, but it was a mutually beneficial business arrangement” (Stolakis 2021).

Several NARTH officers had prior working relationships with and held leadership positions in ex-gay ministries and Christian political organizations. NARTH officers had also engaged in anti-LGBT political activities (Drescher 1998, 2001; George 2016; Robinson and Spivey 2019) prior to developing formal partnerships with major Christian political and legal organizations such as Liberty Counsel and the Pacific Justice Institute. NARTH and its officers sought to establish the idea that sexual orientation is not an immutable characteristic (Byrd and Olsen 2001-2002), a criterion considered by the US judiciary to grant protected class status (Nussbaum 2010, Knauer 2021). In 1993, Charles Socarides and Harold Voth submitted affidavits in support of an amendment to Colorado’s constitution to ban cities from passing ordinances to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation (Socarides 1993, Drescher 1998). Joseph Nicolosi appeared in a documentary by Summit Ministries titled “Gay Rights, Special Rights: Inside the Homosexual Agenda,” touting his American Psychological Association membership to claim that gays can change their behavior and attractions, in support of the film’s message that gays are not a minority group entitled to protected class status. Socarides submitted an affidavit in 1995 in support of the state’s defense of the Tennessee sodomy law (Dresher 1998).

In 1995, NARTH intentionally cultivated partnerships with major Christian Right political organizations. It established as goals “networking with conservative public policy organizations such as Focus on the Family, the American Family Association, the Family Research Council, and the Heritage foundation” and “interfacing with religious organizations, including ex-gay ministries, Christian counseling services, orthodox ‘Jewish’ groups, and the National Association of Christian Educators” (NARTH Bulletin 1995:2). By the end of NARTH’s first decade, the organization had solidified mutually beneficial partnerships with ex-gay ministries and Christian Right political and legal organizations (Barack and Josephson 2005; Robinson and Spivey 2019). In 2001, co-founder Joseph Nicolosi secured the blessing of powerhouse evangelical Christian psychologist James Dobson, who endorsed him as “the foremost authority on the treatment and prevention of homosexuality” (Dobson 2001:18).

NARTH continued to reap the harvest of its labors at the end of its first decade. In 2001, psychiatrist Robert Spitzer, who advocated in 1973 to remove homosexuality from the DSM, presented a peer-reviewed study at the American Psychiatric Association, based on participants recruited through NARTH and Exodus International, that concluded that is possible for some people to change sexual orientation through therapy and religious practices. NARTH and its partners touted Spitzer’s study as validation of its claims. Its publication in a peer-reviewed journal (Spitzer 2003) generated a firestorm of political and scholarly debate (Drescher and Zucker 2006). The publicity benefitted conversion therapists and invited renewed interest, and greater scrutiny of, the ex-gay movement, including NARTH, by journalists (Besen 2003), scholars (Silverstein 2003, Stewart 2005), activists, and others. In 2002, NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the Kansas Supreme Court in support of a lawsuit filed by Liberty Counsel. The court ruled that a “transsexual” is not a woman, voiding her marriage and inheritance (Robinson and Spivey 2019). In 2005, co-founder Charles Socarides died.

By 2007, several members of the American Psychological Association became so concerned about NARTH and other organizations promoting the belief that homosexuality is a disorder that can be changed through therapeutic and religious interventions, that it formed a task force to evaluate the peer-reviewed research literature on sexual orientation change efforts (SOCE) (Drescher 2015b). The task force report found no scientific evidence to support the efficacy of SOCE (APA 2009; Dresher 2015b). In 2009, the APA also passed a resolution stating that psychologists should avoid misrepresenting the efficacy of SOCE when working with individuals distressed by their own or others’ sexual orientation. Infuriated by the findings of the APA Task Force, NARTH established the Journal of Human Sexuality in 2009 and devoted the first volume to NARTH’s response to the Task Force report. Subsequent issues of the journal published articles and book reviews, mostly by prominent NARTH officers.

Two high-profile scandals severely damaged NARTH’s reputation toward the end of its second decade. In 2010, NARTH officer George Rekers, a psychologist and Baptist minister who also co-founded the Family Research Council, resigned from NARTH’s Scientific Advisory Board after a newspaper reported that he hired a male escort to accompany him on a trip to Europe, where he allegedly received nude massages. Rekers had also frequently provided expert testimony to support discrimination based on sexual orientation in adoption cases and in other areas (Rekers 2006). The same year, NARTH executive secretary Arthur Goldberg, co-founder of the ex-gay ministry Jews Offering New Alternatives to Homosexuality, resigned after it was publicly revealed that he had served time in federal prison for conspiracy to commit fraud (Kent 2010). These events led to more bad press. In 2011, CNN journalist Anderson Cooper aired a special report titled “The Sissy Boy Experiment,” which revealed Rekers’ role in overseeing shocking experiments designed to extinguish effeminate behavior and prevent homosexuality in boys, one of whom committed suicide as an adult. At the close of NARTH’s second decade, Warren Throckmorton (2011), a former NARTH member who previously supported reorientation therapy, revealed that seventy-five percent of NARTH’s members were neither scientists nor therapists, but “lay people, ministers, and activists.”

The beginning of NARTH’s third decade is marked by turmoil and organizational reconstruction. 2012 ushered in a series of major setbacks. In 2012, psychiatrist Robert Spitzer sought to retract the 2003 study that claimed sexual orientation change was possible, saying it was flawed, and apologized for the harm it caused. NARTH submitted an amicus brief to the US Supreme Court to uphold the Defense of Marriage Act, which they partially invalidated, and directed the federal government to recognize state-sanctioned same-sex marriages. NARTH lost its tax-exempt status after neglecting to file the necessary paperwork. The most devastating event for NARTH in 2012 occurred when California became the first state to pass a law banning licensed health professionals from engaging in conversion therapy with minors. NARTH sued and lost. In 2013, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld the constitutionality of the law. The Supreme Court denied a request for further appeal. Exodus International removed NARTH materials from its website and its president, Alan Chambers, publicly renounced reparative therapy. This prompted several Exodus officers and ministries to leave the organization and form a rival ministry network called The Restored Hope Network. NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi joined RHN’s Board. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association removed “Gender Identity Disorder” from the DSM and replaced it with “Gender Dysphoria,” which depathologized people who are transgender and non-binary (APA 2013). The same year, the World Medical Association released a statement (WMA 2013) that “condemns so-called ‘conversion’ or ‘reparative’ methods” by health care professionals. NARTH’s response was published in the official journal of the Catholic Medical Association (Rosik 2014).

These events prompted NARTH’s leaders to entirely rebrand the organization and its messaging. In 2014, the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity became the organization’s new name and “the NARTH Institute” was placed alongside one of ATCSI’s new divisions. ATCSI represents a significant departure from its previous incarnation. In addition to renaming the organization and broadening its mission, ATCSI’s leaders also announced they had created a global advocacy organization, the International Federation for Therapeutic and Counselling Choice (IFTCC), and located ATCSI within that federation. The language of IFTCC’s organizational mission is almost identical to ATCSI’s. The most significant aspect of IFTCC is its “anthropological approach,” which “is based on a Judeo-Christian understanding of the body, marriage and the family” (IFTCC 2022). This development is an official acknowledgement of the religious commitments of the federation and its member organizations, particularly the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity.

NARTH’s founders endeavored to frame the organization as scientific and secular. Despite many years of successfully marketing etiologies of disorder and “reparative therapy” to clients, NARTH’s conversion to ATCSI, which positions “therapeutic choice” before “scientific integrity,” and its new practice guidelines (ATCSI 2018) for change therapy endorsed by the organization, Sexual Attraction Fluidity Exploration in Therapy (SAFE-T), appears as a concession. NARTH’s appeals to science have not protected licensed mental health practitioners against professional and legal regulation. As psychologist Charles Silverstein (2003:33) observed, the “concept of ‘choice’ currently favored by the conservative Christian right is a regression to an earlier religious belief in ‘free will.’”

In 2012, the Southern Poverty Law Center filed a consumer fraud civil lawsuit against an ex-gay organization, Jews Offering New Alternatives to Homosexuality (JONAH), which was co-founded by former NARTH officer Arthur Goldberg. NARTH officers Joseph Nicolosi, Joseph Berger, Christopher Doyle, and James Phelan provided expert declarations in advance of the trial and testified in court in support of JONAH. In 2015, the judge declared that, as a matter of law, homosexuality is not a mental illness and excluded their testimony (Dubrowski 2015). The jury returned a unanimous verdict, finding JONAH liable for consumer fraud. The scientific claims of NARTH experts are increasingly being rejected by the courts (Dubrowski 2015). While ATCSI maintains, despite evolving stances of the mental health establishment to the contrary, that the therapy they endorse is effective, ethical, and safe, it is clear that NARTH’s salvation can no longer rely on its appeals to science alone. Since 2014, ATCSI has more intentionally leveraged rights-based arguments (client autonomy, self-determination, religious liberty, religious diversity, conscience, free speech, and parents’ rights) to defend the legitimacy of its profession (Clucas 2017, Robinson and Spivey 2019).

The first years of ATCSI were extremely difficult. In 2014, members of The United Nations Committee against Torture questioned officials in the U.S. State Department about why 48 states allow conversion therapy with minors (Margolin 2014). In 2015, The Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (United Nations 2015) issued a report calling for all nations to ban “conversion therapies.” In 2015, NARTH co-founder Benjamin Kaufman relinquished his medical license amid allegations of gross negligence and unprofessional conduct (Truth Wins Out 2016). The American Bar Association adopted a resolution urging “…all federal, state, local, territorial and tribal governments to enact laws prohibiting state-licensed professionals from using conversion therapy on minors” (ABA 2015). In 2016, the World Psychiatric Association declared conversion therapy to be “wholly unethical.” In 2017, NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi died, a couple of months before the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a challenge to California’s law banning conversion therapy with minors. Nicolosi’s practice had been harmed by this law, and he was a plaintiff in the lawsuit challenging it (as was NARTH). After his father’s death, Joseph Nicolosi, Jr. trademarked “reparative therapy” and “reintegrative therapy,” in 2018 and 2019 respectively (Justia 2018, 2019). In 2019, juggernaut retailer Amazon.com announced its decision to stop selling books on conversion therapy.

ATCSI’s rights-based rhetorical strategy garnered a significant legal victory in 2020, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit invalidated two ordinances in Florida (the city of Boca Raton and Palm Beach county) that banned conversion therapy with minors. Liberty Counsel, the Christian litigation firm that has worked closely with NARTH/ATCSI for several years (Robinson and Spivey 2019), represented two therapists, former NARTH President Julie Hamilton and Robert Otto. They challenged these ordinances as a violation of free speech. Only time will tell if this is a harbinger of future success.

In 2021, the American Psychological Association adopted a resolution that strengthened its stance against SOCE (APA 2021a) as well as its first resolution opposing gender identity change efforts (APA 2021b). For the first time in the U.S., pro-conversion therapy legislation was “quietly” introduced in five state legislatures (Terkel 2021). Oklahoma’s bill, “The Parental and Family Rights in Counseling Protection Act,” was patroned by Rep. Jim Olson, who quoted ATCSI board member, pediatrician Michelle Cretella, to claim that conversion therapy can be effective and is not harmful (Brack 2021). Arizona’s bill sought to prohibit state agencies from punishing practitioners who engage in therapy “consistent with conscience or religious belief.” None of these bills was passed into law. As of 2022, more than half of the states, and several U.S. cities, have some form of conversion therapy ban, by law or regulation (Movement Advancement Project 2022). Almost all of these prohibit conversion therapy on minors by state-licensed health providers.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

NARTH’s founding goal was to protect the livelihoods of professionals who provide counseling to clients who are distressed about their same-sex attractions and gender nonconformity. In an early Statement of Policy, NARTH asserted that homosexuality “…is inimical to the preservation of the family unit” (NARTH Bulletin 1993a:2). The worldview that NARTH promoted and that ATCSI continues to promote (and shares with its transformational ministry and Christian Right partners) is that the patriarchal, nuclear family structure is God-ordained, is reflected in the natural order, and is the keystone of a healthy society. All of society’s institutions (religion, law, medicine, etc.) should preserve and protect this grand design and the essential gender structure on which it depends (Burack and Josephson 2005; Robinson and Spivey 2007, 2015, 2019).

ATCSI promotes the belief that homosexuality and gender variance are gender identity disorders that develop from gender-deviant parenting/family dynamics or other childhood trauma, which are abetted and exacerbated on a societal level by feminism, gay rights, and the transgender movement (Robinson and Spivey 2007, 2019). Its efforts to market the treatment and prevention of “gender confusion” are reinforced by conservative Judeo-Christian theology and laws that deny LGBT people human and civil rights. ATCSI remains an active partner in these endeavors as well, and currently features on its website a webinar by Liberty Counsel attorney Mat Staver on why The Equality Act, which would add anti-discrimination protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity to federal law, should be opposed.

NARTH’s officers and organizational literature from 1992-2013 attempted to establish a scientific rationale for conversion therapy. The vast majority of the organization’s officers, board members, and advisors during its thirty-year history are individuals who hold religiously conservative positions on the morality of homosexuality and gender variance. In addition, several officers and board members simultaneously held prominent positions in and/or work closely with ex-gay ministry networks and Christian anti-LGBT political organizations. Despite declarations that NARTH is primarily a scientific organization, its literature consistently expressed and encouraged conservative Judeo-Christian condemnation of homosexuality and gender non-conformity. Reparative therapy, which integrates and prioritizes religion within a therapeutic model that prescribes gender resocialization (Robinson and Spivey 2007, 2015, 2019), was developed by theologian Elizabeth Moberly (1983). It has been the dominant “treatment” model since the late 1980s. It was popularized, and possibly plagiarized, by NARTH co-founder Joseph Nicolosi (Besen 2003, Erzen 2006). It has been the most prominent therapy promoted by NARTH and Christian and Jewish ministries around the world for diagnosing and “healing” people of their same-sex attractions and gender dysphoria (Hall 2017, Mikulak 2020, Robinson and Spivey 2015).

In 2014, when the organization rebranded as the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity and developed new practice guidelines, science became secondary to “therapeutic choice” and the religious values and rights of clients and practitioners.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The original goal of NARTH was to protect licensed mental health practitioners who offer SOGIE change therapy from professional regulation. The organization also sought to market therapy to clients, who primarily pursued therapy based on religious conflicts. Both are likely more difficult in a society that increasingly accepts and recognizes the civil rights of LGBT people.

Through NARTH, conversion advocates appeared to engage in all of the familiar activities of a scholarly, scientific professional association. They provided stable leadership, generated a membership, and created an organizational structure to facilitate its work. NARTH sponsors a newsletter, hosts an annual conference (since 1993), maintains a website (since 2006), and publishes its own journal (since 2009). NARTH purported to uphold science as the foundation for research and therapy and to be a secular organization. Its endeavors were exceedingly fruitful for developing mutually beneficial collaborations with change ministry networks and Christian political and legal organizations. NARTH provided scientific legitimacy for ministries and expert testimony for Christian Right litigation, legislation, and policy advocacy. In return, these partners supplied publicity, client referrals, and legal counsel (see Robinson and Spivey 2019). In addition to its scientific practices, NARTH has always operated, de facto, as a religious organization in every aspect of its work (Clucas 2017; Drescher 1998).

ATCSI’s organizational literature (newsletter, website, conference presentations, and journal) has always disseminated and promoted conservative, Judeo-Christian religious views of homosexuality and gender variance. Most of its officers and board members who are licensed mental health professionals integrated theology and/or prescribed religious practices (prayer, reading scripture, attending church or ministry support groups) into their work with clients. The organization’s own survey (Nicolosi, Byrd and Potts 2000) found that most “reorientation psychotherapists” incorporate religion into their work with clients at least some of the time.

ATCSI’s leadership has always represented an interfaith alliance of socially conservative Christians and Jews. The overwhelming majority of ATCSI’s officers, board and committee members, past and present, hold religious affiliations representing conservative Catholic, Jewish, LDS, mainline Protestant, nondenominational and evangelical Christian traditions. Every President in the organization’s history has been a Christian. They commonly publish their work in religious journals and presses (Waidzunas 2015).

ATCSI’s leaders worked closely with and frequently held prominent positions in ex-gay ministry organizations (Robinson and Spivey 2015, 2019; Waidzunas 2015). James Phelan is the former President of Transforming Congregations, a Methodist ministry (Kuyper 1999). Arthur Goldberg co-founded JONAH, a Jewish ministry. David Pruden, Dean Byrd, Shirley Cox, Jerry Harris, and David Matheson served prominently in the LDS ministry, Evergreen International (Petrey 2020). Michael Davidson directs a ministry in the U.K. Charles Socarides, Joseph Nicolosi, Janelle Hallman, Richard Fitzgibbons (Tushnet 2021) and others worked closely with Courage International, a Catholic ministry. Over the years, NARTH/ATCSI conferences regularly included leaders of these ministries as well as Exodus International, One by One, the Restored Hope Network, the International Healing Foundation, and others.

ATCSI also collaborates closely with Christian legal, political, and medical organizations, particularly Liberty Counsel, Focus on the Family, and the American College of Pediatricians (Robinson and Spivey 2019; Spivey and Robinson 2010). Representatives of these and other similar groups often speak at ATCSI conferences. ATCSI’s board members have also held significant leadership roles in Christian political and medical organizations. Former NARTH psychologist and Baptist minister George Rekers co-founded the Family Research Council. Jewish psychiatrist Jeffrey Satinover served as the medical advisor for Focus on the Family. Catholic pediatrician Michelle Cretella was president of the American College of Pediatricians.

In addition to ATCSI’s success in disseminating its literature and ideas through formidable and fruitful partnerships with conservative religious organizations, its leaders have also been prolific advocates, providing media interviews and appearing on popular television shows. A significant aspect of its ability to resist against professional and legal regulation, attract clients, and justify its existence in the public sphere is its rhetorical appeals. Scholars have analyzed the rhetorical “framing” strategies used by NARTH/ATCSI leaders to defend conversion therapy and appeal to various audiences (Arthur et al. 2014, Bennett 2003, Burack and Josephson 2005, Clucas 2017, Conrad and Angell 2004, Robinson and Spivey 2019, Stewart 2005, Waidzunas 2015). While the organization maintains, despite the evolving stances of the mental health establishment to the contrary, that therapy is effective, ethical, and safe, it is clear that ATCSI’s future must depend on a different approach. As SOGIE change therapy became increasingly regulated by the mental health profession and the law, ATCSI’s framing emphasized “client autonomy” and religious rationales more than science. This is the essence of what is reflected by rebranding NARTH as The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity is highly bureaucratized. [Image at right] NARTH’s original leadership structure consisted of an executive director, president, and vice-president, first staffed by Joseph Nicolosi, Charles Socarides, and Benjamin Kaufman (respectively). Nicolosi also edited the NARTH Bulletin and served as the first secretary-treasurer. NARTH established several committees during its first year (NARTH Bulletin 1993a), including: an advisory committee to government, educational and mental health agencies; a committee on media, religious and social service organizations; a committee on the public information/pamphlets, a committee on political and academic intimidation, and a committee to liaison with religious and ex-gay ministries. Jack Hale initially provided legal counsel. NARTH received tax exempt status as a private, non-profit organization in 1993 (NARTH Bulletin 1993b). In 1994, it added a research committee (NARTH Bulletin 1994). NARTH also established a board of directors and a scientific advisory committee.

The NARTH Newsletter (1992:7), renamed “NARTH Bulletin” thereafter, delineated the original categories of membership. These include member (“for individuals engaged in psychological treatment or research of homosexuality… open to psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, and certified social workers [who] have completed a Masters’ [sic] Degree level training sexuality, family, and MFC programs”), associate member (“for educators, public health officials, religious leaders, social scientists and historians, as well as writers in the field of sexuality and family health [including] any individual in the behavioral sciences with a particular interest in homosexuality”), and friends of NARTH (for “individuals who wish to further and encourage the educational and therapeutic aims of this organization”). The membership form noted that NARTH offers client referrals for members in the first category.

NARTH created and dissolved several ad hoc committees from 1992-2013, including an interfaith committee. However, its leadership, organizational and membership structures remained relatively stable as the organization grew. The size of organization’s membership, which was occasionally mentioned in the newsletter and at the annual conference, grew steadily during its first decade. In 2003, NARTH’s membership was “approaching 1,500 and rapidly growing” (Byrd 2003:5). In 2009, NARTH established The Journal of Human Sexuality and created new positions (such as managing editor, and later, an editorial board) to carry out the journal’s work.

In 2014, when NARTH became the Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity, the organization’s leadership originally located “the NARTH Institute,” alongside the organization’s newly-developed divisions within ATCSI. Eventually, the NARTH acronym was phased out altogether. To date, ATCSI’s six divisions include three “public advocacy” divisions (Ethics, Family & Faith; Public Education; and Client Rights) and three “professional” divisions (Clinical, Research, and Medical). Each division has its own goals, a working committee, and an advisory committee.

In 2014, NARTH’s officers also established a global organization, The International Federation for Therapeutic and Counselling Choice, with an explicitly Judeo-Christian worldview, and announced ATCSI as a member of this federation.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

In 30 years, ATCSI has accomplished a great deal of its founders’ vision. Its charter members successfully developed a network of devoted professionals and supporters to advance the organization’s mission and carry out its work. By cultivating synergetic partnerships with established ministry networks and religious political, legal, and health organizations, ATCSI’s efforts revitalized the profession of conversion therapy in the United States, and strengthened the transnational conversion therapy movement. ATCSI has endured loss, weathered scandals, and persisted through negative publicity involving some of its leaders and former allies; however, its primary obstacles are external. ATCSI’s efforts and accomplishments also raise a number of unresolved issues.

The most pressing challenge facing ATCSI is professional and/or legal regulation. ACTSI has formidable opponents, including and beyond mental health, medical, and legal professional associations. These include non-profit organizations that have worked to educate, advocate, legislate, and litigate against conversion therapy, such as Truth Wins Out, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the National Center for Lesbian Rights, and the Trevor Project. To what extent and in what ways can/will mental health associations, state licensing boards, and legislatures regulate conversion therapists? Will the movement to pass state laws banning licensed health providers from engaging in conversion therapy with minors maintain momentum? What is the likelihood of regulating this through existing laws protecting children from abuse (Hicks 1999)? Scholars have identified limitations and loopholes of these approaches (Alexander 2017, Calvert 2020, Drescher 2022). What about consumer fraud legislation, such as the proposed federal Therapeutic Fraud Prevention Act, which would make advertising conversion therapy in exchange for remuneration a fraudulent practice for minors and adults? What about state and federal legislation to “defund” Alexander 2017) or deny the use of public funds to pay for it, such as the proposed Prohibition of Medicaid Funding for Conversion Therapy Act? In what ways might the daunting prospect of “high-tech” conversion therapies present new opportunities for conversion proponents, and more complex challenges for regulating them (Earp, Sandberg, and Savulescu 2014)?

In three decades, ATCSI has proven resilient and has largely resisted attempts by professional associations and advocacy organizations to discourage or obstruct SOGIE change therapy. The consensus position of the mental health establishment is that no sexual orientation or gender identity is a mental illness. Should clients be allowed to pursue attempts to change anyway, for themselves or their children, based on their religious beliefs or any other reason? While some licensed practitioners have been affected by state laws and regulations banning therapy with minors, most have largely avoided legal and/or professional regulation (IRTC 2020). This is particularly true for unlicensed, religious counselors, whose religious practices are beyond the regulatory reach of U.S. law (Cruz 1998-1999, Knauer 2020). ATCSI’s division on client rights is dedicated to resisting professional and legal control, and earned a significant, recent victory that invalidated two ordinances. To what extent will ATCSI’s religious freedom and rights-based arguments succeed in the judiciary? What about the court of public opinion? How will furthering the human and civil rights of LGBT people, which have advanced significantly since NARTH began in 1992, affect the demand for conversion therapy? The market today remains robust.

IMAGES

Image #1: Joseph Nicolosi

Image #2: Charles Socarides

Image #3: Logo of National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

Image #4: The Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity.

REFERENCES

Alexander, Melissa Ballengee. 2017. “Autonomy and Accountability: Why Informed Consent, Consumer Protection, and Defunding May Beat Conversion Therapy Bans.” University of Louisville Law Review 55:283-322.

Alumkal, Antony. 2017. Paranoid Science: The Christian Right’s War on Reality. New York: New York University Press.

American Bar Association. 2015. Accessed from https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/-administrative/crsj/committee/aug-15-conversion-therarpy.authcheckdam.pdf on 10 April 2022.

American Medical Association. 2019. “LGBTQ Change Efforts (So-called ‘Conversion Therapy’).” Accessed from https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-12/conversion-therapy-issue-brief.pdf on 10 April 2022.

American Psychiatric Association. 2013. DSM-5 Fact Sheet: Gender Dysphoria. Accessed from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/-educational-resources/dsm-5-fact-sheets on 10 April 2022.

American Psychiatric Association. 2000. “Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies).” APA Document Reference 200001. Accessed from http://media.mlive.com/news/detroit_impact/other/APA_position_conversion%20therapy.pdf on 10 April 2022.

American Psychological Association. 2021a. “APA Resolution on Sexual Orientation Change Efforts.” Accessed from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-sexual-orientation-change-efforts.pdf on 10 April 2022.

American Psychological Association. 2021b. “APA Resolution on Gender Identity Change Efforts.” Accessed from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/resolution-gender-identity-change-efforts.pdf on 10 April 2022.

American Psychological Association. 2009. Report of the American Psychological Association Task Force on Appropriate Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Accessed from http://www.apa.org/pi/lgbc/publications/therapeutic-resp.html on 10 April 2022.

American Psychological Association. 2009. Resolution on Appropriate Affirmative Responses to Sexual Orientation Distress and Change Efforts. Washington, D.C.: APA.

Arthur, Elizabeth, Dillon McGill, and Elizabeth H. Essary. 2014. “Playing It Straight: Framing Strategies among Reparative Therapists.” Sociological Inquiry 84:16–41.

ATCSI. 2022. “Mission Statement.” Alliance for Therapeutic Choice and Scientific Integrity. Accessed from https://www.therapeuticchoice.com/our-mission on 10 April 2022.

ATCSI. 2018. “Guidelines for the Practice of Sexual Attraction Fluidity Exploration in Therapy.” The Journal of Human Sexuality 9:3-58.

Babits, Chris. 2019. To Cure a Sinful Nation: Conversion Therapy and the Making of Modern America, 1930 to Present Day. Doctoral Dissertation. Austin, TX: University of Texas.

Bennett, Jeffrey A. 2003. “Love Me Gender: Normative Homosexuality and ‘Ex-Gay’ Performativity in Reparative Therapy Narratives.” Text and Performance Quarterly 23:331-52.

Besen, Wayne R. 2003. Anything but Straight: Unmasking the Scandals and Lies Behind the Ex-Gay Myth. New York: Harrington Park Press.

Beverley, James A. 2009. Nelson’s Illustrated Guide to Religions: A Comprehensive Introduction to the Religions of the World. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Brack, Hayley Twyman. 2021. “Bill to Protect Conversion Therapy in Oklahoma Passes State Committee.” The Oklahoma Counseling Institute, February 10. Accessed from https://ecpd.memberclicks.net/ on 10 April 2022.

Burack, Cynthia, and Jyl J. Josephson. 2005. A Report from “Love Won Out.” New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Byrd, A. Dean. 2003. “NARTH: On Track for the Future.” NARTH Conference Reports. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

Byrd, A. Dean and Stony Olsen. 2001-2002. “Homosexuality: Innate and Immutable?” Regent University Law Review 14:383-422.

Calvert, Clay. 2020. “Testing the First Amendment Validity of Laws Banning Sexual Orientation Change Efforts on Minors: What Level of Scrutiny Applies after Becerra and Does and Proportionality Approach Provide a Solution?” Pepperdine Law Review 47:1-44.

Christianson, Alice. 2005. “A Re-Emergence of Reparative Therapy.” Contemporary Sexuality 39: 8-17.

Cianciatto, Jason and Sean Cahill. 2006. Youth in the Crosshairs: The Third Wave of Ex-Gay Activism. Washington, DC: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force.

Clucas, Rob. 2017. “Sexual Orientation Change Efforts, Conservative Christianity and Resistance to Sexual Justice.” Social Sciences 6:1-49.

Conrad, Peter and Alison Angell. 2004. “Homosexuality and Remedicalization.” Society 41:32-39.

Cruz, David B. 1998-1999. “Controlling Desires: Sexual Orientation Conversion and the Limits of Knowledge and Law.” Southern California Law Review 72:1297-1400.

Davies, Bob. 1998. History of Exodus International: An Overview of the Worldwide Growth of the “Ex-Gay” Movement. Seattle, WA: Exodus International-North America.

Dobson, James. 2001. Bringing up Boys. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House.

Drescher, Jack. 2022. “Foreword.” Pgs. xi-xv in The Case against Conversion “Therapy”: Evidence, Ethics, and Alternatives, edited by Douglas C. Haldeman. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association.

Drescher, Jack. 2015a. “Can Sexual Orientation be Changed?” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health 10:84-93.

Drescher, Jack. 2015b. “Out of DSM: Depathologizing Homosexuality.” Behavioral Sciences 5:565-75.

Drescher, Jack. 2001. “Ethical Concerns Raised When Patients Seek to Change Same-Sex Attractions.” Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy 5:181-210.

Drescher, Jack. 1998. “I’m Your Handyman: A History of Reparative Therapies.” Journal of Homosexuality 36:19-42.

Drescher, Jack and Ken Zucker. 2003. Ex-Gay Research: Analyzing the Spitzer Study and its Relation to Science, Religion, Politics, and Culture. New York: Routledge.

Dubrowski, Peter R. 2015. “The Ferguson v JONAH Verdict and a Path Towards National Cessation of Gay-to-Straight ‘Conversion Therapy.’” Northwestern University Law Review 110:77-117.

Earp, Brian D., Anders Sandberg, and Julian Savulescu. 2014. “Brave New Love: The Threat of High-Tech ‘Conversion’ Therapy and the Bio-Oppression of Sexual Minorities.” AJOB Neuroscience 5:4-12.

Erzen, Tanya. 2006. Straight to Jesus: Sexual and Christian Conversions in the Ex-Gay Movement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Flentje, Anessa, Heck, Nicholas C., and Cochran, Bryan N. 2013. “Sexual Reorientation Therapy Interventions: Perspectives of Ex-Ex-Gay Individuals.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 17:256–77.

Ford, Jeffry G. 2001. “Healing Homosexuals: A Psychologist’s Journey through the Ex-Gay Movement and the Pseudo-Science of Reparative Therapy.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy 5:69-86.

George, Marie-Amelie. 2016. “The Custody Crucible: The Development of Scientific Authority about Gay and Lesbian Parents.” Law and History Review 34:487-529.

Gonsiorek, John C. 2004. “Reflections from the Conversion Therapy Battlefield.” The Counseling Psychologist 32:750-59.

Grace, Andre P. 2008. “The Charisma and Deception of Reparative Therapies: When Medical Science Beds Religion.” Journal of Homosexuality 55:545-80.

Haldeman, Douglas C., ed. 2022. The Case Against Conversion “Therapy”: Evidence, Ethics, and Alternatives. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association.

Haldeman, Douglas C. 1999. “The Pseudo-Science of Sexual Orientation Conversion Therapy.” Angles: The Policy Journal of the Institute for Gay and Lesbian Strategic Studies 4:1-4.

Hall, Dorota. 2017. “Religion and Homosexuality in the Public Domain: Polish Debates about Reparative Therapy.” European Societies 19:600-22.

Hicks, Karolyn Ann. 1999. “‘Reparative’ Therapy: Whether Parental Attempts to Change a Child’s Sexual Orientation Can Legally Constitute Child Abuse.” American University Law Review 49:505-47.

Horne, Sharon G. and Mallaigh McGinley. 2022. “Sexual Orientation Efforts and Gender Identity Change Efforts in International Contexts: Global Exports, Local Commodities.” Pp. 221-46 in The Case against Conversion “Therapy”: Evidence, Ethics, and Alternatives, edited by Douglas C. Haldeman. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association.

IFTCC. 2022. Accessed from https://ftcc.org/about on 10 April 2022.

ILGA World and Lucas Ramon Mendos. 2020. Curbing Deception: A World Survey on Legal Regulation of So-Called “Conversion Therapies.” Geneva: ILSA World.

IRTC. 2020. It’s Torture, Not Therapy: A Global Overview of Conversion Therapy: Practices, Perpetrators, and the Role of States. Copenhagen: International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims. Accessed from https://irct.org/publications/thematic-reports/146 on 10 April 2022.

Isay, Richard A. 1996. Becoming Gay: The Journey to Self-Acceptance. New York: Pantheon.

Justia. 2019. Accessed from https://Trademarks.justia.com/876/99/reintegrative-87699885.htm on 10 April 2022.

Justia. 2018. Accessed from https://Trademarks.justia.com/876/99/reparative-87699798.htm on 10 April 2022.

Kaufman, Benjamin. 2001-2002. “Why NARTH? The American Psychiatric Association’s Destructive and Blind Pursuit of Political Correctness.” Regent University Law Review 14:423-42.

Kaufman, Benjamin. 1993. “Why NARTH?” NARTH Conference, December 14. Encino, CA: NARTH.

Kent, Norm. 2010. “National Anti-Gay Leader is a Convicted Felon, Con Man.” South Florida Gay News. February 10. https://southfloridagaynews.com/National/ex-gay-is-ex-con.html on 10 April 2022.

Knauer, Nancy J. 2020. “The Politics of Eradication and the Future of LGBT Rights.” The Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law 21:615-70.

Konnoth, Craig J. 2017. “Reclaiming Biopolitics: Religion and Psychiatry in the Sexual Orientation Change Therapy Cases and Establishment Clause Defense.” Pgs. 276-87 in Law, Religion and Health in the United States, edited by Holly Fernandez Lynch, I. Glenn Cohen, and Elizabeth Sepper. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kuyper, Robert L. 1999. Crisis in Ministry: A Wesleyan Response to the Gay Rights Movement. Anderson, IN: Bristol House.

Margolin, Emma. 2014. “UN Panel Questions Gay Conversion Therapy in the US.” Accessed from https://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/gay-conversion-therapy-un-committee-msna458431 on 10 April 2022.

Martin, A. Damien. 1984. “The Emperor’s New Clothes: Modern Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation.” Pps. 24-57 in Psychotherapy with Homosexuals, edited by Emery S. Hetrick and Terry S. Stein. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Mikulak, Magdalena. 2020. “Telling a Poor Man He Can be Rich: Reparative Therapy in Contemporary Poland.” Sexualities 23:44-63.

Moberly, Elizabeth R. 1983. Homosexuality: A New Christian Ethic. Cambridge: Clarke & Co.

Moss, Kevin. 2021. “Russia’s Queer Science, or How Anti-LGBT Scholarship is Made.” The Russian Review 80:17-36.

Movement Advancement Project. 2022. “Conversion Therapy Laws.” Accessed on https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/conversion_therapy 10 April 2022.

NARTH. 2012. Brief of Amicus Curiae in the Supreme Court of the United States. Accessed from http://www.2012-may-31-gill-v-opm-first-circuit-ruling.pdf on 10 April 2022.

NARTH. 2010. Brief of Amicus Curiae in the Supreme Court of the State of California. Accessed from https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2021/may/27/shawn-vestal-matt-shea-out-at-tcapp-over-schism-wi/ on 10 April 2022.

NARTH. 2007. Brief of Amicus Curiae, Hawaii Supreme Court. www.qrd.org/qrd/usa/legal/-hawaii/baehr/1997/brief.natl.assn.research.and.therapy.of.homosexuality-03.24.97 on 10 April 2022.

NARTH Bulletin. 1995. Volume 3, Number 1, April. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

NARTH Bulletin. 1994. Volume 2, Number 1, (March.. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

NARTH Bulletin. 1993a. Volume 1, Number 2, March.. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

NARTH Bulletin. 1993b. Volume 1, Number 3, July. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

NARTH Newsletter. 1992. Volume 1, Issue 1, December. Encino, CA: National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality.

NASW. 2015. Sexual Orientation Change Efforts and Conversion Therapy with Lesbians, Gay Men, Bisexuals, and Transgender Persons. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Work.

NASW. 1992. “Position Statement on Reparative or Conversion Therapies for Lesbians and Gay Men.” Washington, DC: National Association of Social Work.

Nicolosi, Joseph. 2012. “A Call for a Psychologically-Informed Ministry for Homosexual Catholics,” Pp, 523-35 in Loving in Difference: The Forms of Sexuality in Catholic Thought: Interdisciplinary Study, edited by Livio Melina and Sergio Belardinelli: Vatican City: Vatican Publishing House.

Nicolosi, Joseph. 2001. “A Developmental Model for Effective Treatment of Male Homosexuality: Implications for Pastoral Counseling.” American Journal of Pastoral Counseling 3:87-99.

Nicolosi, Joseph. 1991. Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality: A New Clinical Approach. New York, NY: Jason Aronson.

Nicolosi, Joseph, A. Dean Byrd, and Richard Potts. 2000. “Beliefs and Practices of Therapists Who Practice Sexual Reorientation Psychotherapy.” Psychological Reports 86:689-702.

Nicolosi, Joseph and Linda Ames Nicolosi. 2002. A Parent’s Guide to Preventing Homosexuality. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Nussbaum, Martha. 2010. From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law. New York: Oxford University Press.

Panozzo, Dwight. 2013. “Advocating for an End to Reparative Therapy: Methodological Grounding and Blueprint for Change.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 25:362-77.

Petrey, Taylor G. 2020. Tabernacles of Clay: Sexuality and Gender in Modern Mormonism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Phelan, James E., Whitehead, Neil and Sutton, Philip M. 2009. “What Research Shows: NARTH’s Response to the APA Claims on Homosexuality.” Journal of Human Sexuality 1:1-82.

Queiroz, Jandira, Fernando D’Elio, and David Maas. 2013. The Ex-Gay Movement in Latin America: Therapy and Ministry in the Exodus Network. Somerville, MA: Political Research Associates.

Rekers, George A. 2006. “An Empirically-Supported Rational Basis for Prohibiting Adoption, Foster Parenting, and Contested Child Custody by Any Person Residing in a Household that includes a Homosexually-Behaving Member.” St. Thomas Law Review 18:325-424.

Robinson, Christine M. and Sue E. Spivey. 2019. “Ungodly Genders: Deconstructing Ex-Gay Movement Discourses of ‘Transgenderism’ in the USA.” Social Sciences 8:191-219.

Robinson, Christine M. and Sue E. Spivey. 2015. “Putting Lesbians in their Place: Deconstructing Ex-Gay Discourses of Female Homosexuality in a Global Context.” Social Sciences 4:879-908.

Robinson, Christine M. and Sue E. Spivey. 2007. “The Politics of Masculinity and the Ex-Gay Movement.” Gender & Society 21:650-75.

Rosik, Christopher. 2014. “NARTH Response to the WMA Statement on Natural Variations of Human Sexuality.” The Linacre Quarterly 81:111-14.

Shidlo, Ariel, Michael Schroeder, and Jack Drescher, editors. 2001. Sexual Conversion Therapy: Ethical, Clinical, and Research Perspectives. New York: Haworth Press.

Silverstein, Charles. 2003. “The Religious Conversion of Homosexuals: Subject Selection is the Voir Dire of Psychological Research.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy 7:31-53.

Socarides, Charles W. 1995. “How America Went Gay.” America 173:20-22. Accessed from https://www.dioceseoflansing.org/sites/default/files/2017-03/courage_1015.pdf on 10 April 2022.

Socarides, Charles. 1993. District Court, City and County of Denver, Colorado. Case No. 92 CV 7223. Affidavit of Charles W. Socarides, M.D., Evans vs Romer.

Socarides, Charles W. and Benjamin Kaufman. 1994. “Reparative Therapy.” American Journal of Psychiatry 151:157-58.

Spitzer, Robert L. 2003. “Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation? 200 Participants Reporting a Change from Homosexual to Heterosexual Orientation.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 32:403-17.

Spivey, Sue E. and Christine M. Robinson. 2010. “Genocidal Intentions: The Ex-Gay Movement and Social Death.” Genocide Studies and Prevention 5:68-88.

Stewart, Craig O. 2005. “A Rhetorical Approach to News Discourse: Media Representations of a Controversial Study on ‘Reparative Therapy.’” Western Journal of Communication 69:147-66.

Stolakis, Kristine (director/producer). 2021. Pray Away. Accessed from https://www.prayawayfilm.com/team on 10 April 2022.

Streed, Carl G. Jr., J. Seth Anderson, Chris Babits, and Michael A. Ferguson. “Changing Medical Practice, Not Patients: Putting an End to Conversion Therapy.” New England Journal of Medicine 381:500-02.

Terkel, Amanda. 2021. “Republicans Quietly Push ‘Conversion Therapy’ Bills in Anti-LGBTQ Fight.” https://www.huffpost.com/entry/republicans-state-legislatures-conversion-therapy-lgbtq_n_60771da7e4b0e554e81a6a6b

Thorn, Michael. 2015. “Ex-Gay Movement.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. October 28. Accessed from www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/ on 10 April 2022.

Throckmorton, Warren. 2011. “NARTH is Not Primarily Composed of Mental Health Professionals.” Accessed from http://www.patheos.com/blogs/warrenthrockmorton/2011/10/24/narthis-not-primarily-composed-of-mental-health-professionals/ on 10 April 2022.

Tozer, Erin. E. and Hayes, Jeffrey A. 2004. “The Role of Religiosity, Internalized Homonegativity, and Identity Development: Why Do Individuals Seek Conversion Therapy?” The Counseling Psychologist 32:716-40.

Truth Wins Out. 2016. Press Release. Accessed from https://truthwinsout.org/pressrelease/2016/03/40834/ on 10 April 2022.

Tushnet, Eve. 2021. “Conversion Therapy is Still Happening in Catholic Spaces and its Effects on L.G.B.T. People Can be Devastating.” America: The Jesuit Review. Accessed from https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2021/05/13/conversion-therapy-lgbt-catholic-240635 on 10 April 2022.

United Nations. 2015. Discrimination and Violence against Individuals Based on Their Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights). Geneva: United Nations.

Waidzunas, Tom. 2015. The Straight Line: How the Fringe Science of Ex-Gay Therapy Reoriented Sexuality. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Williams, Alan Michael. 2011. “Mormon and Queer at the Crossroads.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 44(1): 53-84.

World Medical Association. 2013. “WMA Statement on Natural Variations of Human Sexuality.” Accessed from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-natural-variations-of-human-sexuality/ on 10 April 2022.

Publication Date:

12 April 2022

typically belong to the Boston church (formally known as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and also known as The Mother Church), as well as a local “branch” church. Local churches are found all over the world. The Christian Bible and Science and Health serve as pastor for all churches. [Image at right] Eddy’s book has been translated into seventeen languages as well as Braille.

typically belong to the Boston church (formally known as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and also known as The Mother Church), as well as a local “branch” church. Local churches are found all over the world. The Christian Bible and Science and Health serve as pastor for all churches. [Image at right] Eddy’s book has been translated into seventeen languages as well as Braille. ,” there were women who were able to face this disparity, becoming public faces for the movement as well as making things happen. In 1913, Laura E. Sargent (1858–1915), who had studied under Eddy and served as her companion for a number of years, became the first woman to teach in the Church’s Board of Education, training Christian Science practitioners (healers who advertise their services) to be teachers.

,” there were women who were able to face this disparity, becoming public faces for the movement as well as making things happen. In 1913, Laura E. Sargent (1858–1915), who had studied under Eddy and served as her companion for a number of years, became the first woman to teach in the Church’s Board of Education, training Christian Science practitioners (healers who advertise their services) to be teachers. publications; the editor-in-chief was a man.

publications; the editor-in-chief was a man. Christian Science Board of Lectureship. [Image at right] Glenn had also served as a Second Reader in church services in Boston. It was not until 1977 that Grace Channell Wasson (1907–1978) became the first woman appointed to the First Reader role, leading the weekly church services. Previously, only men had held that three-year position at the Boston headquarters.

Christian Science Board of Lectureship. [Image at right] Glenn had also served as a Second Reader in church services in Boston. It was not until 1977 that Grace Channell Wasson (1907–1978) became the first woman appointed to the First Reader role, leading the weekly church services. Previously, only men had held that three-year position at the Boston headquarters.

until it rebranded as ATCSI in 2014. It is one of the most influential partners in the transnational conversion ministry movement and the anti-LGBT Christian Right (Moss 2021, Robinson and Spivey 2019), both of which were inaugurated during the 1970s. The founders attempted to establish NARTH as a scientific association and promote therapy as an effective method for treating homosexuality, which they viewed as a gender identity disorder (Bennett 2003, Robinson and Spivey 2007). To date, the organization’s legacy includes revitalizing the market for conversion therapy and developing a global advocacy network for its practitioners. For many years, NARTH also rendered some credibility for its two major partners, the ministry networks that promise the possibility of change and Christian political groups opposed to LGBT rights.

until it rebranded as ATCSI in 2014. It is one of the most influential partners in the transnational conversion ministry movement and the anti-LGBT Christian Right (Moss 2021, Robinson and Spivey 2019), both of which were inaugurated during the 1970s. The founders attempted to establish NARTH as a scientific association and promote therapy as an effective method for treating homosexuality, which they viewed as a gender identity disorder (Bennett 2003, Robinson and Spivey 2007). To date, the organization’s legacy includes revitalizing the market for conversion therapy and developing a global advocacy network for its practitioners. For many years, NARTH also rendered some credibility for its two major partners, the ministry networks that promise the possibility of change and Christian political groups opposed to LGBT rights. repeated assertions found in NARTH’s literature and by its representatives that NARTH is not a religious organization, NARTH’s newsletter, conference presentations, journals, and website promote socially conservative religious beliefs and practices. Religion is the keystone on which the vocation and professional work of conversion therapists depend, since most clients who seek therapy do so based on moral or religious conflicts related to their own or their children’s sexuality or gender (Flentje, Heck and Cochran 2013; Haldeman 2022; Nicolosi and Nicolosi 2002; Rosik 2014; Spivey and Robinson 2010; Streed, Anderson, Babits and Ferguson 2019).

repeated assertions found in NARTH’s literature and by its representatives that NARTH is not a religious organization, NARTH’s newsletter, conference presentations, journals, and website promote socially conservative religious beliefs and practices. Religion is the keystone on which the vocation and professional work of conversion therapists depend, since most clients who seek therapy do so based on moral or religious conflicts related to their own or their children’s sexuality or gender (Flentje, Heck and Cochran 2013; Haldeman 2022; Nicolosi and Nicolosi 2002; Rosik 2014; Spivey and Robinson 2010; Streed, Anderson, Babits and Ferguson 2019). with clients (Nicolosi 1991, 2001, 2012). For many years, NARTH was headquartered at Nicolosi’s Thomas Aquinas Psychological Clinic. Charles Socarides, [Image at right] a psychiatrist who served as the organization’s first president, was one of the most vocal opponents of the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. In a magazine published by the Jesuits of the United States, Socarides described his clinical work with homosexual men as “…a kind of ‘pastoral care’…. many of us thought we were quietly doing God’s work” (Socarides 1995). He called the idea, found in some pro-gay literature, that God made people gay “blasphemy.” Benjamin Kaufman was a Jewish psychiatrist (Thorn 2015) who served as the organization’s first vice-president.

with clients (Nicolosi 1991, 2001, 2012). For many years, NARTH was headquartered at Nicolosi’s Thomas Aquinas Psychological Clinic. Charles Socarides, [Image at right] a psychiatrist who served as the organization’s first president, was one of the most vocal opponents of the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. In a magazine published by the Jesuits of the United States, Socarides described his clinical work with homosexual men as “…a kind of ‘pastoral care’…. many of us thought we were quietly doing God’s work” (Socarides 1995). He called the idea, found in some pro-gay literature, that God made people gay “blasphemy.” Benjamin Kaufman was a Jewish psychiatrist (Thorn 2015) who served as the organization’s first vice-president.

League, one of several early socialist movements emerging in England. He was expelled the following year due to accusations of operating as a spy for the Prussian police (despite scant evidence) (Howe and Möller 1978). During the 1890s, Reuss moved in several esoteric and masonic groups. [Image at right] This is where Reuss met Carl Kellner, whom Reuss later claimed wished to create an “Academia Masonica” uniting all masonic degrees and systems (Reuss 1912:15). Around the year 1900, Reuss obtained charters to establish several high-degree masonic rites in Germany via Gérard Encausse (alias Papus, 1865–1916), founder of the Martinist Order; William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), Freemason and co-founder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn; and the Freemason John Yarker (1833–1913). In 1902, Reuss began issuing the periodical Oriflamme as a vehicle for his ideas (Höwe and Möller 1978; Kaczynski 2012).

League, one of several early socialist movements emerging in England. He was expelled the following year due to accusations of operating as a spy for the Prussian police (despite scant evidence) (Howe and Möller 1978). During the 1890s, Reuss moved in several esoteric and masonic groups. [Image at right] This is where Reuss met Carl Kellner, whom Reuss later claimed wished to create an “Academia Masonica” uniting all masonic degrees and systems (Reuss 1912:15). Around the year 1900, Reuss obtained charters to establish several high-degree masonic rites in Germany via Gérard Encausse (alias Papus, 1865–1916), founder of the Martinist Order; William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), Freemason and co-founder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn; and the Freemason John Yarker (1833–1913). In 1902, Reuss began issuing the periodical Oriflamme as a vehicle for his ideas (Höwe and Möller 1978; Kaczynski 2012). Christian sect, Crowley was no novice to esoteric activity. In 1898, he had joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in London, rising quickly through the grades. His involvement with the order ended in 1900. In 1904, on honeymoon with his first wife Rose (née Kelly, 1874–1932), [Image at right] Crowley was visited by a discarnate entity named Aiwass, whom Crowley considered to be a messenger of the god Horus. Over three days, Aiwass dictated a text to Crowley: The Book of the Law, later given the technical title Liber AL vel Legis (Crowley 2004). Though initially skeptical of the book’s message, Crowley eventually accepted his status as prophet of a new religion: Thelema (Greek for “will”), of which The Book of the Law became the central sacred text. In 1907, Crowley and his former Golden Dawn mentor George Cecil Jones (1873–1960) founded the Order of the Silver Star or A\A\, which drew on the degree structure and ritual magical practices of the Golden Dawn combined with yogic techniques Crowley had learned travelling in Asia (Crowley 1994). Crowley also made study of the “Holy Books of Thelema” part of the A\A\ curriculum (Crowley 1909). Like Reuss, Crowley was a periodical publisher, having issued The Equinox as a vehicle of A\A\ since 1909.

Christian sect, Crowley was no novice to esoteric activity. In 1898, he had joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in London, rising quickly through the grades. His involvement with the order ended in 1900. In 1904, on honeymoon with his first wife Rose (née Kelly, 1874–1932), [Image at right] Crowley was visited by a discarnate entity named Aiwass, whom Crowley considered to be a messenger of the god Horus. Over three days, Aiwass dictated a text to Crowley: The Book of the Law, later given the technical title Liber AL vel Legis (Crowley 2004). Though initially skeptical of the book’s message, Crowley eventually accepted his status as prophet of a new religion: Thelema (Greek for “will”), of which The Book of the Law became the central sacred text. In 1907, Crowley and his former Golden Dawn mentor George Cecil Jones (1873–1960) founded the Order of the Silver Star or A\A\, which drew on the degree structure and ritual magical practices of the Golden Dawn combined with yogic techniques Crowley had learned travelling in Asia (Crowley 1994). Crowley also made study of the “Holy Books of Thelema” part of the A\A\ curriculum (Crowley 1909). Like Reuss, Crowley was a periodical publisher, having issued The Equinox as a vehicle of A\A\ since 1909. ceremonially sworn to secrecy. Crowley claimed to have retorted that he, ignorant of the order’s secret, could hardly be guilty of revealing it, to which Reuss responded by indicating a passage from Crowley’s The Book of Lies (first published in 1912, see Crowley 1980). Crowley describes how realization dawned on him. On April 21, Reuss thus conferred the IX° on Crowley, appointing him National Grand Master of OTO in Great Britain and Ireland (Crowley 1989:709–10). [Image at right] Reuss also appointed Crowley OTO representative for the U.S.. Parts of Crowley’s account are called into question by the lack of evidence of OTO existing as a membership organization prior to 1912. Though the order’s first constitution is dated to January 22, 1906, the document was likely produced closer to 1912, and it is thus reasonable to assume that OTO as a functioning organization emerged from Reuss’s and Crowley’s collaboration and mainly from 1912 on (cf. Howe and Möller 1978).

ceremonially sworn to secrecy. Crowley claimed to have retorted that he, ignorant of the order’s secret, could hardly be guilty of revealing it, to which Reuss responded by indicating a passage from Crowley’s The Book of Lies (first published in 1912, see Crowley 1980). Crowley describes how realization dawned on him. On April 21, Reuss thus conferred the IX° on Crowley, appointing him National Grand Master of OTO in Great Britain and Ireland (Crowley 1989:709–10). [Image at right] Reuss also appointed Crowley OTO representative for the U.S.. Parts of Crowley’s account are called into question by the lack of evidence of OTO existing as a membership organization prior to 1912. Though the order’s first constitution is dated to January 22, 1906, the document was likely produced closer to 1912, and it is thus reasonable to assume that OTO as a functioning organization emerged from Reuss’s and Crowley’s collaboration and mainly from 1912 on (cf. Howe and Möller 1978). teachings. From the outset, several women held executive offices within the order, including Crowley’s first Grand Secretary General, Vittoria Cremers, and succeeding Secretaries, Leila Waddell (1880–1932) and Leah Hirsig (1883–1975) (cf. Hedenborg White 2021b). [Image at right]