THE PUBLIC UNIVERSAL FRIEND TIMELINE

1752 (November 29): Jemima Wilkinson was born into a Quaker family in Cumberland, Rhode Island Colony.

1775-1776: Wilkinson began attending New Light Baptist meetings.

1776 (July 4): The United States declared independence from England.

1776 (September): The Smithfield monthly meeting of Quakers expelled Wilkinson from the congregation as punishment for her New Light association.

1776 (October 5): Wilkinson fell ill with a fever.

1776 (October 11): Wilkinson recovered from the fever as The Public Universal Friend.

1777: The Friend expanded public preaching from local venues to other locations in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

1777 (September): The Smithfield Quakers disowned Jeremiah Wilkinson, The Friend’s father.

1778: The Friend and Sarah Skilton Richards met in Watertown, Connecticut.

1779: The Friend established a ministry at Little Rest, Rhode Island and began preaching in Connecticut, establishing greater influence and a sizeable following.

1779: The Friend published Some Considerations, Propounded to the Several Sorts and Sects of Professors of This Age, the first written teachings.

1779: Captain James Parker and Abner Brownell became followers of The Friend.

1780: Judge William Potter became a follower, along with nine of his thirteen children.

1782 (October): The Friend visited Philadelphia in order to win more converts and was attacked by a mob.

1782 (October): Abner Brownell published Enthusiastical Errors, Transpired and Detected, purporting to expose The Friend as a fraud.

1783 (September 18): Society of Universal Friends was formally established.

1784 (August): The Friend again visited Philadelphia, returned after a short time to New England, and began planning the establishment of a colony in western New York.

1784 (November): The Universal Friend’s Advice, to Those of the Same Religious Society, outlining The Friend’s doctrines, was published.

1785: The Friend’s brother, Jeptha Wilkinson, dispatched to the western New York wilderness to explore the prospect of land purchase.

1786: The Society of Universal Friends established a fund to purchase land, and decided upon the Genesee area in western New York as the site for their new community settlement.

1786: After the death of her husband, Sarah Richards, a close associate of The Friend, became a member of The Friend’s household, serving as its practical and financial manager.

1787: A small party began exploration of the area known as Genesee Country in order to find suitable property for settlement

1788: William Parker, who joined the Society of Universal Friends in 1779, purchased land from a New York consortium known as The Lessees, unaware that their rights to make such a sale were disputed on multiple fronts.

1788 (June): Twenty-five Universal Friends, led by James Parker, arrived to begin settling on the land in Genesee.

1788 (July): Survey of the Preemption Line started. Upon completion of the survey, it was discovered that the Universal Friends had located their settlement on land that belonged to New York State.

1789: The Universal Friends group was large enough to gain official recognition as a religious denomination in Rhode Island. Settlers continued migrating to the Friends’ settlement in western New York.

1790: The Friend arrived at the settlement with a handful of followers. The population grew to around 260, becoming the largest white community in western New York.

1791 (Spring): James Parker traveled to New York City in order to petition Governor George Clinton to resolve the land ownership issue.

1791: The Society of Universal Friends gained legal recognition as a religious denomination from New York State.

1791 (December): The United States concluded its war of independence against England.

1792 (October 10): New York State granted clear title to William Potter, James Parker, and Thomas Hathaway for the property in Genesee.

1793 (November 30): Sarah Richards died.

1794 (February 20): The Friend moved to a new house on a new property called Jerusalem, about twelve miles west of the Society of Universal Friends settlement in Genesee.

1796: Eliza Richards, Sarah’s daughter, eloped with Enoch Malin, the brother of two close associates of The Friend, Rachel and Margaret Malin.

1798: In an attempt to lay legal claim to The Friend’s property, Enoch and Eliza Malin brought an ejectment suit against The Friend. Claiming that the marriage conferred ownership of all the property held in Sarah’s name, Enoch began selling off The Friend’s property.

1799 (June): Trial was held in the Ontario County Circuit Court. The Friend was found not guilty of trespassing.

1799 (September 17): James Parker issued a warrant for the Friend’s arrest, on charges of blasphemy.

1800 (June): The Friend went to court in Canandaigua, the county seat of Ontario County, to face charges of blasphemy. As blasphemy was not a crime in New York State, the case was rejected.

1819 (July 1): The Friend died at home in Jerusalem.

1840: The Society of Universal Friends ceased functioning.

BIOGRAPHY

Jemima Wilkinson, the eighth child of Quaker farmers Jeremiah and Amey Wilkinson, was born November 29, 1752 in Cumberland, Rhode Island Colony. The Public Universal Friend came into existence on October 11, 1776, when Jemima was not quite twenty-four.

Jemima’s early life was shaped by the massive social and spiritual upheaval generated by the American Revolution (1765–1791), and the persistent enthusiasms of the First Great Awakening (1730–1740s). Three of Jemima’s brothers were expelled from the Society of Friends for joining the War for Independence, directly counter to the core Quaker principle of pacifism. Her older sister Patience was also ousted for giving birth to a child out of wedlock. Jemima herself was disciplined “for not attending Friends meetings and not using the plain language” (Wisbey 1964:7), and in September 1776 was expelled entirely from the Smithfield meeting for attending meetings of the New Light Baptist Congregation in Abbott Run. The then-radical and revolutionary embrace of evangelism, emotional fervor and conversion experiences of the so-called New Lights separated and alienated them from the more staid and comparatively more authoritarian “Old Light” Baptist and Congregationalist denominations. Besides the fact that Jemima had been failing to attend Quaker meetings, the evangelical excitement of the New Lights ran counter to the Quaker value of Quietism, further justifying the expulsion. Moreover, the evangelical fervor driving the New Lights and other schismatic movements within mainstream Protestantism was also beginning to affect the Quakers, as “Separators” began to break away from established meeting “and rejected church doctrine in favor of individual conscience” (Moyer 2015:17).

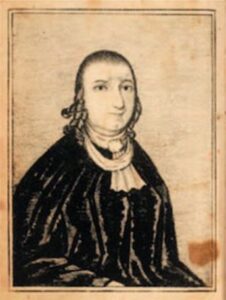

Shortly after her expulsion, on Tuesday, October 5, Jemima became seriously ill from a fever, possibly typhus. The following Friday, upon a sudden recovery, the person formerly known as Jemima announced that she was dead, in heaven, and that God had reanimated the body with a divine spirit. [Image at right] This spirit was neither male nor female, no longer Jemima, but identified as The Public Universal Friend. The Friend refused to answer to the name Jemima or to any female pronouns, preferring any variant of the title that avoided pronouns. (Respecting that desire, scholars today either refer to The Friend in the third person plural, or avoid pronouns altogether.) The Friend’s followers did the same, referring to their leader variously as The Dear Friend, Dearest of Friends, Best-Friend, The Friend, All-Friend. The Friend often self-identified as The Comforter, an allusion to John 14:16 and 15:26 implying that The Friend’s nature was the Holy Spirit sent from God to warn humanity of Christ’s return and offer a path to salvation. Available sources do not say why the Spirit chose the specific title “Public Universal Friend.”

Presumably the “Friend” designation derives from the Quaker term for themselves, in keeping with the nonhierarchical nature of their faith and their view of their personal relationship with God: “No longer do I call you servants, for the servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you,” said Jesus (John 15:15). The “Public Universal” aspect emphasized the more strongly evangelical nature of the Spirit’s mission, whose primary message was the availability of salvation for everyone.

The following Sunday, after attending a meeting at the old Elder Miller Baptist Meeting House at Abbott Run, The Friend delivered the first public sermon under a large tree in the churchyard (Wisbey 1964:14–15). By early 1777, The Friend was attracting followers, speaking by invitation at churches and meeting houses, inns, or in the homes of the new faithful. In September 1777, after the Smithfield Quakers expelled Jeremiah Wilkinson for his association with The Friend, he joined The Friend’s following. Five other family members eventually also converted.

Among the hundreds of followers The Friend began to amass, several individuals emerged who were to become key to the movement. Two women were particularly important in the Universal Friend’s community early on. Ruth Pritchard, who joined in 1777, eventually became official record-keeper and chronicler for the Society of Universal Friends established in 1783. Sarah Richards, who began following The Friend in 1778, became such a close companion that followers came to refer to her as “Sarah Friend.” Eventually fully managing their Friend’s finances, business dealings, and household affairs, Sarah was generally accepted within the community as “mistress of the household,” but was sometimes referred to as “the prime minister” by detractors (Dumas 2010:42). William Parker, who had served as a captain in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, surrendered his commission when he joined the Universal Friends in 1779. Judge William Potter, who joined in 1780, likewise sacrificed his considerable political standing, but brought a great deal of wealth and respectability to the community, as well as nine of his thirteen children as converts.

As The Friend’s ministry expanded through Rhode Island and Connecticut, focus turned next to Philadelphia, then the capital city of the new nation. The unusual appearance of The Friend and the women in the company, who tended toward androgynous apparel, caused a sensation, stirred up by the newspapers of the time. Shortly after The Friend arrived in the capitol city with a small retinue, the boarding house where the company was staying was attacked by a mob throwing stones and bricks. Although The Friend made only one convert during this disastrous visit, the group made two return visits, one for nine months in 1784, where they were welcomed by the community of Free Quakers. In addition to disaffected Quakers, The Friend drew a few converts from the Pennsylvania Schwenkfelders, followers of the Protestant mystic Kasper Schwenkfeld (1490–1561). Among these was the Wegener family. Abraham, one of the sons, eventually founded the village of Penn Yan, New York.

The difficulty of attaining new followers, frustration at the unlikely prospect of saving the world from its apocalyptic fate, and increasingly sensationalized coverage by a press that had no idea what to make of The Friend’s unusual manners or ministry, all led to The Friend’s decision to create a private community in a less populated area. While the Ephrata colony and the Shakers may have served as models, the Universal Friends did not aim to operate communally. They intended to retain individual ownership of their homes, land, and possessions, serve The Friend, and advance their mission of creating a new Jerusalem solely for themselves.

To this end, Jeptha Wilkinson, The Friend’s brother, was sent to western New York in order to explore the feasibility of purchasing land. The plentiful, fertile land in the area between the Genesee River and Seneca Lake, then referred to as the Genesee Country, initially seemed promising. General John Sullivan’s genocidal campaign of 1779 devastated the Haudenosaunee native inhabitants. While the campaign created opportunities for land speculation and white settlement, multiple parties claimed ownership. Both New York and Massachusetts did so by presumed right of colonial charter. British Canada had an interest as well, which it sought to advance with its now much-diminished indigenous former allies, who up until Sullivan’s campaign had unquestionably been the rightful occupants, and still retained land ownership throughout much of the region.

As part of a compromise agreement between New York and Massachusetts in December 1786, the two states established a boundary line in the disputed territory, referred to as the Preemption Line. The official survey of the Preemption Line was not conducted until 1788, however. Moreover, although New York State law prohibited individuals from buying land directly from the Native Americans who still actually owned it, a group of New York speculators, allied with some Canada-based British officials and led by John Livingston, a prominent Hudson Valley landowner, endeavored to profit from the situation. They did so by forming the New York Genesee Land Company and the Niagara Genesee Land Company sometime in 1787. Their aim was to strike an agreement with the Seneca allowing the Land Company to lease Seneca-owned land to unwary potential settlers in search of a bargain, under the name The Lessee Company, typically referred to as The Lessees. One such unfortunate individual was James Parker, one of The Friend’s most trusted community members, who had been commissioned to acquire land for the planned community.

Parker had invested a great deal of money toward this purchase, as had several other Friends. While each one who contributed did so with an understanding that the portion of the land they received would be proportional to their contribution, this understanding was never codified as a written contract. Individuals unable to contribute to the fund apparently also expected, again in absence of any kind of clear written agreement or contract, that other Friends would assist them so they too could have some share of the property. Consequently, through a combination of fraud, conflicting legal claims, poor planning, poor communication, and outright confusion, the parcel of land Parker finally managed to obtain on behalf of the community (a narrow strip of approximately 1,100 acres) was considerably less than the 14,000 acres he and the Society of Universal Friends thought they had purchased from The Lessees. Community members who had invested large sums found themselves with drastically reduced acreage as their share, and the poorer members could not be accommodated at all.

In 1790, after difficult travel, The Friend arrived at the settlement, along with several companions. The population, now at 260, represented the largest settlement in western New York, and about twenty percent of the White  population in the region. Faced with food shortages due to bad harvests, the community erected a grist mill which, along with government aid, alleviated the worst hunger issues. They also erected a meeting house and a home for The Friend, and in 1791, received recognition as a religious organization from New York State, which the community assumed would solidify their claim to the land and enable them to more easily acquire more. [Image at right]

population in the region. Faced with food shortages due to bad harvests, the community erected a grist mill which, along with government aid, alleviated the worst hunger issues. They also erected a meeting house and a home for The Friend, and in 1791, received recognition as a religious organization from New York State, which the community assumed would solidify their claim to the land and enable them to more easily acquire more. [Image at right]

Once established, the settlement began to prosper, until a second survey of the Preemption Line revealed that the land actually belonged to the State of New York, and not The Lessees or any other of the land companies involved in the deal. In 1791, James Parker on behalf of the Society directly petitioned George Clinton, then the governor of New York, for resolution. Based on the fact that the Society had extensively improved the land, the petition succeeded. Parker’s was the only name on the title, however, and the fact that the original land had been sold and resold several times made matters worse. In the meantime, several Society members, frustrated by what they regarded as Parker’s mishandling of the situation, appointed two other members, Thomas Hathaway and William Potter, to resolve the ongoing title issues.

On October 10, 1792, Governor Clinton deeded 14,040 acres to Parker, Potter, and Hathaway, as tenants in common. Given that other Society members had paid an original share for the purchase and that all who had settled there had put in hard labor that improved the value of the land, the situation became intolerable. After a series of meetings in summer 1793, the entire tract was divided into twelve sections, with shares distributed in a way that did not take into account either the existing homes and farms of the current settlers or the financial stake of any of the original contributors. As a result, Parker emerged as owner of nearly half the share. Only seventeen people total received shares, not all of whom were original settlers or early financial contributors. As a result, many people received either no land after all their efforts, or lost the value of their improvements.

The Friend, who had only just arrived to the settlement in 1790, became quickly dismayed by the perpetual conflict and secured an entirely different parcel of land. Because The Friend refused to use a birth name or sign it on any legal document, already complex property transactions became even more byzantine. Followers Thomas Hathaway, Benedict Robinson, and a few others obtained another parcel of property west of the original settlement. The Friend in turn purchased a sizeable portion of this parcel from Hathaway and Benedict. Sarah Richards, acting as agent and trustee, obtained the property on behalf of The Friend in her own name. The Friend took up residence in this new settlement, called Jerusalem, in 1794, soon joined by several other families wishing to escape the perpetual conflict that had beset the original community.  Unfortunately, Sarah Richards, who had been The Friend’s close companion, business manager, and trustee, died in 1793 of an illness, before she could move into the house they had planned to live in together. [Image at right]

Unfortunately, Sarah Richards, who had been The Friend’s close companion, business manager, and trustee, died in 1793 of an illness, before she could move into the house they had planned to live in together. [Image at right]

Besides the emotional loss of a close companion and most trusted ally, Sarah’s death left The Friend bereft of her considerable business and household management skills as well. While Rachel Malin and her sister Margaret took over many of Sarah’s responsibilities, the fact that The Friend was besieged with a series of personal and legal attacks shortly thereafter suggests that the sisters may have been less than effective.

The Friend’s move to Jerusalem shifted personal and political dynamics within the community in several significant ways. Several families who had suffered losses from Parker and Potter’s arguably unscrupulous land dealings followed The Friend to Jerusalem, establishing property and building homes near to The Friend’s own home. Several other families, many of them former Quakers, established homesteads there as well. A number of smaller houses surrounded The Friend’s home, the vast majority of them female-headed households, occupied by widows, single women, and their families. Somewhere between sixteen and eighteen people, again mostly women, resided in The Friend’s home, generally referred to as The Friend’s family. These women who lived close to The Friend or in The Friend’s house, about forty-eight in number, were called “The Faithful Sisterhood,” and remained The Friend’s most loyal followers.

Although several families in the old settlement remained on good terms with The Friend, James Parker and William Potter, whose unscrupulous land dealings kept many Society members from receiving their fair share, retained positions of considerable power and influence both within and outside the Society of Universal Friends. They, along with a growing number of once loyal followers, broke away from The Friend, becoming actively hostile. Significantly, the apostate faction was comprised almost entirely of men, many of them, like Parker and Potter, wealthy, influential, politically connected to mainstream institutions of power and government, and aggrieved by what they regarded as the usurpation of their natural authority by The Friend and the most loyal female followers.

On September 17, 1799, Parker, who six years prior had been appointed Justice of the Peace for Ontario County, issued a warrant for The Friend’s arrest, on the charge of blasphemy. After two unsuccessful attempts to apprehend The Friend, a posse of around thirty men, most of them apostate followers, broke violently into The Friend’s home. A doctor who had accompanied the men determined that The Friend, aging and chronically ill, was too unwell to be brought to jail in the middle of the night, so the mob agreed that The Friend might appear voluntarily before the Canandaigua County court.

The Friend did so in June of the following year. The charge of blasphemy was supported by the accusation that The Friend had claimed to be Jesus Christ. Moreover, the argument ran, the level and degree of authority supposedly claimed over the Society indicated that The Friend presumed to be exempt from the laws of the state. Further testimony, implying that The Friend “actively worked to undermine the institution of marriage,” along with a social order built on gender and class hierarchies, revealed the extent to which the legal action served primarily to undermine The Friend’s authority (Moyer 2015:173). Since blasphemy was not, in fact, a crime in the State of New York, however, The Friend could not be prosecuted on those charges, and the case was thrown out of court.

Unsuccessful in this attempt to undermine The Friend’s authority, the antagonistic faction returned to the perennial issue of property ownership claims. In this they were more successful, and the attack much more personal. In 1793, three years after Sarah Richards died, her sixteen-year-old daughter Eliza eloped with Enoch Malin, Rachel and Margaret’s younger brother. As Eliza’s husband, Enoch now owned all of the property she inherited from her mother. Although Sarah Richards did own some property on her own, most of it she had bought as a trustee on behalf of The Friend, who refused to sign any name but The Public Universal Friend or a cross-mark on any legal document. Sarah had described this arrangement in her will, but with apparently enough ambiguity that Enoch Malin attempted to seize control of all the land originally purchased in Sarah Richards’ name, first by attempting in June 1799 to evict The Friend for trespassing with an ejectment lawsuit, a legal action in civil court to recover possession or title to land against someone supposedly trespassing or otherwise occupying it illegally. When this failed, he began selling off parcels of The Friend’s land in his own name.

In 1811, Rachel Malin, on behalf of The Friend, countered with an ejectment lawsuit against Enoch and Eliza Malin, and everyone who had bought property from Enoch. By the time this suit was finally taken up in the Court of the Chancery five years later, however, Enoch and Eliza had bowed out of their original lawsuit, sold their rights to any claim, and moved to Canada in 1812. When Enoch died shortly after the move, Eliza moved to Ohio with their two children, where she also died three years later.

In the meantime, Elisha Williams, an outsider and a lawyer who had been an associate of the New York Lessees that had defrauded James Parker on the original property deal, took up the lawsuit. The legal battles continued until 1828, when the Court for the Trial of Impeachments and the Correction of Errors, commonly called the Court of Errors and at that time the highest appellate authority in New York State, decided in favor of The Friend. Unfortunately, this final victory occurred nine years after The Friend’s death in 1819, most likely of congestive heart failure. The prolonged battle had drained the Society of most of its finances. Rachel and Margaret Malin eventually were forced to sell off much of the property before they both died in the 1840s. What property remained was distributed to their own families rather than to surviving Society members. While several descendants remain in the area (now the village of Penn Yan, New York), neither the religion nor the movement survived the death of The Friend’s most devout followers, particularly the Malin sisters who had replaced Sarah Richards as managers, trustees, and closest confidantes.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Strictly speaking, The Friend’s ministry occurred between the First Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s and the Second Great Awakening (c. 1790-1840). Historian Paul B. Moyer argues, however, that the radical unrest of the American Revolution amplified and continued the earlier religious upheavals, and that the ministry of the Universal Friend “confirms that the years between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries represent an unbroken era of religious ferment” (2015:5). In further support of this thesis, he points out that “Insurgent denominations like the Methodists and Baptists had their roots in the colonial period, but rose to prominence during the Revolution, while even more radical sects such the Shakers, Society of Universal Friends, Free Will Baptists, and Universalists also came into being” (2015:6).

As far outside the mainstream as an emergent religious movement led by an adamantly genderless prophet may have been, The Friend’s ministry was not, in terms of doctrine, belief, or practice, particularly unusual or original. The first publication of those teachings attributed to The Friend, Some Considerations, Propounded to the Several Sorts and Sects of Professors of This Age, was overtly plagiarized, apparently by Abner Brownell, a follower who later became a detractor (Brownell 1783). His sources were two well-known Quaker texts: the 1681 The Works of Isaac Pennington and William Sewel’s 1722 The History of the Rise, Increase, and Progress of the Christian People Called Quakers.

The Friend’s essential message was drawn largely from Jemima Wilkinson’s Quaker upbringing, combined with elements of the New Light Baptist teachings that had originally drawn the young Jemima away from Quakerism. The Quaker aspects included a strong emphasis on free will and the promise of salvation for every human who led a righteous and penitent life and served the Lord. Human beings, according to The Friend, “came pure from God, their Creator, and have remained so till they reached the years of understanding, and became old enough to know good from evil” (Cleveland 1873, cited in Dumas 2010:56). This message of innocence at birth, free will, and universal salvation put The Friend’s teaching squarely at odds with the then-predominant Calvinist doctrine of predestination. In keeping with Quaker principles, The Friend opposed slavery. Some teachings, such as the value of inspired speech, the perils of sin, the importance of righteous behavior, and the availability of God’s grace outside of established religious structures, as well as the overall evangelistic approach, were informed by New Light theology. The Friend’s self-positioning as an inspired prophet through whom God spoke and thus claiming divine authority over followers, however, differed from the emphasis on direct individual experience of God that characterized most evangelical Protestantism of the time.

The teaching had an apocalyptic focus, with a premillennial emphasis on the Final Judgment as divine punishment, and apparently regarded the Universal Friend’s emergence into the world after the purported death of Jemima Wilkinson in 1776 as evidence not only of the coming apocalypse, but that The Friend and the Society had a key role in the anticipated battle. As chronicler turned apostate Abner Brownell describes, “she has advanc’d something in a prophetic manner of the fulfilment of the prophecy of Daniel, and what is told of in revelation, that the time began when she began to preach of the thousand two hundred and ninety days . . . and that she seem’d to have an allusion that she was the woman spoken of in revelations, that was now fled into the wilderness. . .” (Brownell 1783:12–13; see Rev. 12).

If the mission of salvation was straightforward, free-will Protestantism, the nature and source of The Friend’s spiritual authority, remained notably ambiguous. Detractors accused The Friend of claiming to be the Messiah, the Second Coming of Christ. Although some of their followers may well have believed it, The Friend never made this claim. The most specific role The Friend would claim was as “Comforter” or Holy Spirit sent from God in aid of all humanity. The most direct statement The Friend would make to address the question, according to an anonymous letter published in The Freeman’s Journal of March 28, 1787, was “I am that I am” (cited in Moyer 2015:24). At the very least, acceptance and membership into the Society required acknowledgment of The Friend’s authority as a prophet.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Certain surface similarities exist between The Friend and Mother Ann Lee (1736–1784), leader of the Shakers, with whom she was a contemporary. The roots of both communities were in Quakerism, feature leaders who were biologically female, and granted equal leadership authority to men and women, in accordance with Quaker teaching. Both at various points in their histories suffered attacks (occasionally physical) for transgressing socially prescribed gender roles. There were, however, some important differences. The Society of Universal Friends was never intended to be a communal society, nor were they particularly utopian. Family members remained together, maintaining individual households, finances, and property. Members lived with as much material comfort as their means could afford.

The Universal Friend “accepted the principal doctrines of the Christian faith, but rejected the formalities and ceremonies generally practiced. With more zeal for the spirit than the form of faith, [The Friend] inculcated sobriety, temperance, chastity, all the higher virtues and humility before God as necessary to the new life, and entrance into a better world” (Cleveland 1873:42). Like Quakers, they conducted meetings that mostly involved members sitting silently, unless the Holy Spirit moved one of them to speak, and then only after The Friend had spoken first. The meetings began at 10:00 a.m., continued for several hours, and were held most days of the week.  Members also gathered regularly for more informal prayer meetings. The Society’s members kept the Sabbath, regarding Sunday as a day of rest, but later also observed Saturday Sabbath.

Members also gathered regularly for more informal prayer meetings. The Society’s members kept the Sabbath, regarding Sunday as a day of rest, but later also observed Saturday Sabbath.

The Friend typically dressed in long clothes: capes, gowns, and shirts that appeared masculine to observers, a large plain hat of the sort more typically worn by Quaker men, and long, loose hair in the style of male ministers of the time. [Image at right] The Friend usually wore women’s shoes, however. Though there was no specific dress code, many of the followers dressed in a similar, somewhat androgynous manner, with long robes and long, loose hair. The style presumably derived from the Quaker emphasis on modesty, simplicity, and plainness, but struck onlookers as peculiar. As a further departure from Quaker plain style, The Friend also adopted a personal seal. Emblazoned on the side of The Friend’s carriage as well as many personal possessions, the seal  represented a noteworthy early awareness of the power of brand recognition.

represented a noteworthy early awareness of the power of brand recognition.

Modesty in personal conduct and speech were similarly required. [Image at right] Wine was to be consumed in moderation if at all. While smoking was not explicitly forbidden, it was discouraged. While not forbidden, sexual relations were discouraged as well. The Friend practiced lifelong celibacy, and encouraged, but did not require, followers to follow suit. Followers could marry if they wished.

Communicating with God through dreams was a common practice. Several of the followers kept dream journals, regularly sharing and interpreting each other’s dreams in order to better apprehend divine messages. Early in the mission, The Friend occasionally practiced faith healing, but was known to heal the sick also through practical means such as bone-setting, herbal medicines, and folk remedies familiar to frontier communities.

LEADERSHIP

As God’s emissary on earth, The Friend exercised absolute spiritual authority over the Society, and supervised various facets of their everyday life as well. The Friend settled disputes, maintained discipline among the followers, advised on household and other matters, and was materially supported by followers in matters of food, clothing, and shelter. During Sabbath meetings, The Friend was the first to speak, and the first to be served at meals; no others were served until The Friend had finished eating.

The Society was noteworthy, relative to similar sects of the time, for maintaining an unusual degree of gender equality. In the early itinerant phase of the ministry, The Friend typically traveled with a gender-balanced retinue of three or four each of men and women. Once the Society formed its New York settlement, power struggles ensued. Clearly gendered in nature, they also played out geographically. A close community consisting of several dozen mostly single and celibate women developed in service to The Friend. Dubbed “The Faithful Sisterhood” by later chroniclers, these women, some four dozen, attained a great deal of spiritual authority within the community, speaking and praying at meetings and serving The Friend in various capacities. Avowed to lead celibate, single lives, most of them lived within The Friend’s household; a few others lived in small houses closest to the main house. Some women, such as Sarah Richards and the Malin sisters, wielded power as intermediaries between The Friend and the outside world and served as business managers, property agents, and advisers as well. Furthest from The Friend, emotionally, spiritually, and geographically, were men such as Judge William Potter and James Parker, who were wealthy and well-connected with the political structures of the outside world. These men and their cohorts remained in City Hill, the original settlement, where their financial maneuverings left them majority landowners. They worked actively to undermine The Friend’s spiritual and financial authority. The fact that Enoch Malin, whose sisters had settled in Jerusalem and were among The Friend’s closest confidantes, collaborated with Parker and Potter and others against The Friend indicates, however, that tensions existed within the Jerusalem settlement as well as outside it.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

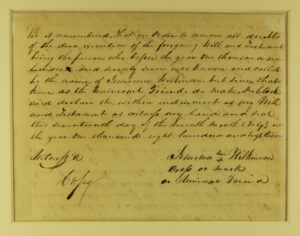

Two major issues persisted throughout The Friend’s ministry: non-adherence to contemporary gender norms, and whether or not the prophet was actually Christ returned for the Second Coming. The Friend’s refusal to acknowledge either an original birth name or assigned gender, including signatures on legal documents, requiring others to purchase property and sign on the prophet’s behalf, left property rights disastrously open to legal challenge, as evinced by the fact that the legal challenges to Sarah Richards’ will continued for a decade  after The Friend’s death. In order to avoid similar issues with The Friend’s own Last Will and Testament, [Image at right] the compromise was to allow someone else to write the name “Jemima Wilkinson” above The Friend’s characteristic cross-shaped mark, and to specify in the document: “Be it remembered that in order to remove all doubts of the due execution of the foregoing Will and Testament, being the person who before the year one thousand one hundred and seventy seven was known and called by the name of Jemima Wilkinson, but since that time as the Universal Friend. . . .” Although The Friend’s refusal to claim or disavow messianic status, the will claimed divine justification for disavowing the birth name in the very first paragraph: “who in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy six was called Jemima Wilkinson and ever since that time the Universal Friend a new name which the mouth of the Lord hath named” (Public Universal Friend’s Will 1818).

after The Friend’s death. In order to avoid similar issues with The Friend’s own Last Will and Testament, [Image at right] the compromise was to allow someone else to write the name “Jemima Wilkinson” above The Friend’s characteristic cross-shaped mark, and to specify in the document: “Be it remembered that in order to remove all doubts of the due execution of the foregoing Will and Testament, being the person who before the year one thousand one hundred and seventy seven was known and called by the name of Jemima Wilkinson, but since that time as the Universal Friend. . . .” Although The Friend’s refusal to claim or disavow messianic status, the will claimed divine justification for disavowing the birth name in the very first paragraph: “who in the year one thousand seven hundred and seventy six was called Jemima Wilkinson and ever since that time the Universal Friend a new name which the mouth of the Lord hath named” (Public Universal Friend’s Will 1818).

While The Friend never claimed messianic status, detractors justified their denunciations by seizing on the fact that the prophet did not directly refute the perceptions of followers who may have held such beliefs. Both of these factors, along with the continuing property disputes within the New York settlement, led to irreconcilable tensions within the community, defection of some key members, and internal attacks directed against The Friend, particularly launched by male community members who had held positions of trust and authority. In Moyer’s analysis, the key issue was that The Friend’s detractors found the high degree of female authority and independence that characterized the Society, as well as the Friend’s sustained gender ambiguity, to be “unsettling” (2015:164). The property disputes that beset the New York frontier community from its inception, along with the sustained challenges to The Friend’s authority from within the Society itself, were the main reasons that it failed to survive beyond their lifetime.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

The Friend’s theology was not particularly original, nor, within the various communal experiments of the time was the Society of Universal Friends all that unusual in providing a space and voice for women in religious life. What the ministry did provide is a space within religious life for gender expression radically outside the norm.

Women certainly participated within the movement in significant and unusual ways. The preponderance of women in positions of authority within the community, along with the high percentage of female-led households in the settlement is noteworthy. Scholarship has yet to fully analyze or properly interpret the clear same-sex partnerships the movement accommodated, as exemplified by The Friend and Sarah Richards. It is impossible to say whether the Society represented a refuge for lesbian couples. Most of the unmarried women outwardly followed The Friend’s model of celibacy. The concept of gay or lesbian persons did not exist in the colonial era, and the existence and presence of same-sex sexual partnerships as we understand them were never documented.

Paul Moyer’s definitive study of The Friend’s life and work demonstrates that the American Revolution and the various religious movements of the early- to mid-eighteenth century allowed for a degree of participation by women in every level of public, private, and religious life that “pushed the boundaries of the gendered status quo” (2015:199). Within this context, The Universal Friend’s life, work, and self-presentation, “provided a space for a renegotiation of what it meant to be a man and a woman,” particularly for female followers who enjoyed within their community a degree of autonomy and authority far beyond the typical roles of wife and mother (2015:200).

But The Friend’s lifelong refusal to acknowledge gender in writing, speech, and legal affairs, mixed-gender self-presentation in clothing choices and leadership style described by contemporaries as masculine, “presented a far more radical challenge to the status quo [and] called into question the very distinctions between man and woman” (Moyer 2015:200). Though detractors were quick to refer to The Friend derisively as “Jemima” and to apply female pronouns, followers themselves avoided using gendered pronouns when referring to the prophet (Brekus 1998:85). Ultimately, The Friend attracted followers not because of the message or as a woman leading a religious movement, but because a person whose presentation of a religious message involved the complete rejection of gender signifiers was so unfathomable as to seem otherworldly. As religion and gender studies scholar Scott Larson observes, “Otherworldliness was an embodied theological practice, and as a resurrected spirit, the Friend performed overlapping, conflicting, and multiple categories of being and, by mixing gender signifiers, indicated divine presence and power within the world” (Larson 2014:578).

The Friend’s self-presentation continues to challenge contemporary discussions of gender,particularly the ways gender is produced and reproduced within language. Until recently, scholarly works on The Friend bypassed the problem entirely, simply referring to The Friend as Jemima Wilkinson, with feminine pronouns. Among the first to address the issue directly, Moyer opted, uneasily, to use the pronoun “she” when referring to Jemima Wilkinson, and “he” when referring to The Friend. Following understandings advanced by current gender scholars, particularly those whose focus is on trans identity, but also reflecting The Friend’s well-documented refusal of gender, historian Scott Larson uses no gendered pronouns in his discussion in order to “practice new grammatical structures out of the recognition that grammars of gender are themselves historical,” in order to “unsettle the ease with which gender seems to translate across time and across radically different structures of belief” (2014:583). It is in this radical unsettling of language, the structures by which humans comprehend and organize their world, that The Public Universal Friend’s life, ministry, and self-definition may well have opened a space for comprehension beyond the ordinary framework of being, thus potentially redefining the very work of religion.

IMAGES

Image #1: Portrait of The Public Universal Friend.

Image #2: A document from 1791 in which the signatories describe themselves as a religious body with trustees entrusted to carry out legal affairs and property transactions on behalf of the Society. Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Hamilton College.

Image #3: Home of The Public Universal Friend, Town of Jerusalem, northwest of the Village of Penn Yan, New York.

Image #4: 1815 portrait, depicting The Friend’s characteristic mode of dress.

Image #5: The Friend’s seal.

Image #6: The second page of The Friend’s Will, bearing the “x or cross” mark and the title “Universal Friend.” Courtesy of the Yates County History Center.

REFERENCES

Brekus, Catherine. 1998. Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Brownell, Abner. 1783. Enthusiastical Errors, Transpired and Detected in a Letter to His Father, Benjamin Brownell. New London, CT: self-published.

Cleveland, Stafford C. 1873. History and Gazetteer of Yates County. Penn Yan, NY: self-published.

Dumas, Frances. 2010. The Unquiet World: The Public Universal Friend and America’s First Frontier. Dundee, NY: Yates Heritage Tours Project.

Larson, Scott. 2014. “‘Indescribable Being’: Theological Performances of Genderlessness in the Society of the Publick Universal Friend, 1776-1819.” Early American Studies. Special Issue: Beyond the Binaries: Critical Approaches to Sex and Gender in Early America 12:576–600.

Moyer, Paul B. 2015. The Public Universal Friend: Jemima Wilkinson and Religious Enthusiasm in Revolutionary America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

The Public Universal Friend’s Will. 1818. Penn Yan: Yates County History Center. February 25.

Wisbey, Herbert A. 1964. Pioneer Prophetess: Jemima Wilkinson, the Publick Universal Friend. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Hudson, David. 1844. Memoir of Jemima Wilkinson, a Preacheress of the Eighteenth Century; Containing an Authentic Narrative of her Life and Character, and of the Rise, Progress, and Conclusion of her Ministry. Bath, NY: R.L. Underhill.

Publication Date:

24 March 2022