OUR LADY OF GUADALUPE TIMELINE

1322: A shepherd in Extremadura, Spain, found a 59 cm statue of the black Virgin of Guadalupe.

1340: A sanctuary to Guadalupe was founded by King Alfonso XI at Villuercas, Extremadura, Spain.

Pre-Hispanic Period: Goddess Tonantzin-Coatlicue was venerated at the Tepeyac Hill in Mexico.

1519: A banner with the Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception was brought by Hernán Cortés during his conquest of Mexico.

1531: Five apparitions of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe took place at the Tepeyac Hill, Mexico

1556: Fray Francisco de Bustamante delivered a sermon denouncing the excessive cult attached to a painting of Guadalupe by the Indigenous artist, Marcos Cipac de Aquino.

1609: The first Spanish sanctuary to Guadalupe was built at the Tepeyac Hill.

1648 and 1649: The first historical references to the Mexican Guadalupe cult were published in essays by Miguel Sánchez and Luis Lasso de la Vega, respectively.

1737: Guadalupe was proclaimed the official patroness of Mexico City.

1746: Guadalupe was proclaimed the official patroness of all of New Spain (Mexico).

1754: An official Guadalupe’s holiday was established in the Catholic calendar.

1810-1821: Guadalupe played a patriotic role during the Mexican War of Independence.

1895: Guadalupe was crowned.

1910: Guadalupe was declared patroness of Latin America.

1935: Guadalupe was proclaimed patroness of the Philippines.

1942: Guadalupana Societies were funded by Mexican American Catholic women.

1960s: Guadalupe became a cultural icon for the United Farmworkers strike and other Movimiento Chicano struggles.

1966: Guadalupe was granted a golden rose by pope Paul VI.

1970s-Present: Deconstruction, appropriation, and transformation of the traditional Guadalupe image by groups of Chicanos/as for various social and political causes have taken place.

2002: Pope John Paul II canonized the Indian Juan Diego, who was the object of Guadalupe’s apparitions in 1531.

2013: Pope Francis granted Guadalupe a second golden rose.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Documentation by various sources dating back to the sixteenth century confirms that, before Cortés’s Conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in 1519–1521, Mesoamerican peoples worshipped the Mother Goddess Tonantzin-Ciuacoatl (Our Mother–Wife of the Serpent/Snake Woman) in her many forms, performing a yearly pilgrimage to her shrine on the Tepeyac hill. Tonantzin was revered in the same location where the Virgin of Guadalupe’s 1531 apparitions later took place and where the Virgin’s Basilica stands today. The sixteenth-century Franciscan Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, referring to the state of things at the onset of the Conquest, affirmed: “[O]n Tepeyacac . . . . they had a temple consecrated to the mother of the gods, called Tonantzin, which means ‘our mother’ . . . and people came from afar . . . and they brought many offerings” (Sahagún 1956, volume 3:352). Sahagún’s testimony was further confirmed by Fray Juan de Torquemada and the Jesuit Clavijero. During the conversion process of the Indian population, the ancient sacred place of Tepeyac was imbued with new powers by substituting the preexistent Aztec goddess with a Christian holy figure. This common practice was promoted by the church. Although this mandate was carried out, the goddess Tonantzin-Ciuacoatl did not disappear. More correctly, she was synthesized into the Virgin of Guadalupe. This new hybrid figure proved to be an ideal focal point of common faith for the eclectic population of the Spanish Vice-Royalty of New Spain. The process, however, did not occur without surprises.

According to the Virgin of Guadalupe legend, Mary appeared to the humble Indian Juan Diego Cuauhtlatonzin on the Tepeyac hill in 1531, expressing her will that a temple be built for her there. This Nahuatl account of the apparitions, titled Nican Mopohua (Here Is Being Said), attributed to the learned Indian Antonio Valeriano, was published by Lasso de la Vega in 1649 (Torre Villar and Navarro de Anda 1982:26-35). It took four apparitions, a miraculous healing, roses out of season, and the imprint of Mary’s image on Juan Diego’s rustic tilma (cloak) to finally convince Archbishop Zumárraga that the apparitions were true. Interestingly, sixteenth-century sources, such as Sahagún’s Historia general, document the great devotion to the goddess Tonantzin-Ciuacoatl centered on the Tepeyac hill, but there is no written record of the apparitions or of the Virgin of Guadalupe until the mid-seventeenth century. In 1648, Imagen de la Virgen María Madre de Dios Guadalupe, milagrosamente Aparecida en la ciudad de México (Image of Virgin Mary Mother of God Guadalupe, Miraculously Appeared in Mexico City) by Miguel Sánchez, and in 1649, the Nican Mopohua, were published. In fact, what can be found prior to 1648 are omissions or attacks regarding the Tepeyac cult (Maza 1981:39–40). For example, on September 8, 1556, Fray Francisco de Bustamante delivered a sermon in Mexico City, denouncing the excessive cult attached to a painting made by the Indian Marcos and placed in the Guadalupe shrine, because he saw this cult as idolatrous:

It seemed to him that the devotion that this city has placed on a certain hermitage or house of Our Lady, that they titled Guadalupe, (was) in great harm of the natives, because they made them believe that that image which an Indian [Marcos] painted was performing miracles . . . and that now to tell them [the Indians] that an image painted by an Indian was performing miracles, that this would be a great confusion and would undo the good that was sowed, because other devotions, like Our Lady of Loreto and others, had great grounds and that this one would be erected so much without foundation, he was astonished” (Torre Villar and Navarro de Anda 1982:38-44).

Even now, a great controversy surrounds the issue of the apparitions of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the newly baptized Indian Juan Diego. In countless studies related to different aspects of the apparitions and the famous image itself, such as those analyzing the paint, the fabric, the reflections in the Virgin’s eyes, and so on, aparicionistas (those who believe in the apparitions) and antiaparicionistas (those who oppose the apparitions), try to prove their point. What we know for sure is that apparitions are impossible to prove, especially six centuries later. Whether they were real or constructed, we will concentrate on the consequences the alleged apparitions brought to the colonial church, to the national cause, and to the people of Mexico.

Following a precedent established by other Span

Following a precedent established by other Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores, Hernán Cortés came to Tenochtitlan (today’s Mexico City) in 1519, under the protecting banners of the Apostle Santiago (Saint James) and the Virgin Mary. In Spanish minds, the Conquest of America was the continuation of the Reconquista or Reconquest of Spain opposing eight centuries (AD 711–1492) of domination by the Moors. The year 1492, a date that marks the “discovery” of America, held multiple significance. It was the year of the final defeat of the Moors in Granada and of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Another important event of 1492 was the publication of the first Spanish (Castilian) grammar book and the first printed grammar of a vernacular language, The Art of the Castillian Language, by Antonio de Nebrija. These actions reflect the zeal to reinforce the political unity of Spaniards by “cleansing” their faith and by systematizing the official language of the newly united Spain. The popular dramatized dances of Moros y cristianos, representations of battles between Moors and Spaniards, continued in the New World as Danza de la conquista, Danza de la pluma, and Tragedia de la muerte de Atahuallpa, with one alteration, the Moors were replaced by the new infidels, the Indians. The Virgin Mary, traditionally connected to the seas, was long the protectress of the sailors (Nuestra Señora de los Navegantes) and of the Conquest. Cristóbal Colón (Columbus) named his flagship caravel “Santa María” in her honor. Hernán Cortés, like many other conquerors of the New World, came from the impoverished Spanish region of Extremadura. He was a devotee of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Villuercas, whose famous sanctuary was located near his place of origin, Medellín. Villuercas, founded

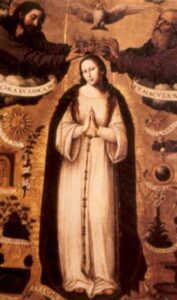

ish and Portuguese conquistadores, Hernán Cortés came to Tenochtitlan (today’s Mexico City) in 1519, under the protecting banners of the Apostle Santiago (Saint James) and the Virgin Mary. In Spanish minds, the Conquest of America was the continuation of the Reconquista or Reconquest of Spain opposing eight centuries (AD 711–1492) of domination by the Moors. The year 1492, a date that marks the “discovery” of America, held multiple significance. It was the year of the final defeat of the Moors in Granada and of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Another important event of 1492 was the publication of the first Spanish (Castilian) grammar book and the first printed grammar of a vernacular language, The Art of the Castillian Language, by Antonio de Nebrija. These actions reflect the zeal to reinforce the political unity of Spaniards by “cleansing” their faith and by systematizing the official language of the newly united Spain. The popular dramatized dances of Moros y cristianos, representations of battles between Moors and Spaniards, continued in the New World as Danza de la conquista, Danza de la pluma, and Tragedia de la muerte de Atahuallpa, with one alteration, the Moors were replaced by the new infidels, the Indians. The Virgin Mary, traditionally connected to the seas, was long the protectress of the sailors (Nuestra Señora de los Navegantes) and of the Conquest. Cristóbal Colón (Columbus) named his flagship caravel “Santa María” in her honor. Hernán Cortés, like many other conquerors of the New World, came from the impoverished Spanish region of Extremadura. He was a devotee of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Villuercas, whose famous sanctuary was located near his place of origin, Medellín. Villuercas,  founded in 1340 by King Alfonso XI, was the most favored Spanish sanctuary from the fourteenth century until the times of the Conquest. It contained the famous black, triangular, fifty-nine-centimeter-high statue of the Virgin with the Christ on her lap, supposedly found by a local shepherd in 1322 (Lafaye 1976:217, 295). [Image at right]

founded in 1340 by King Alfonso XI, was the most favored Spanish sanctuary from the fourteenth century until the times of the Conquest. It contained the famous black, triangular, fifty-nine-centimeter-high statue of the Virgin with the Christ on her lap, supposedly found by a local shepherd in 1322 (Lafaye 1976:217, 295). [Image at right]

What demands our attention, though, is a different representation of the Virgin Mary carried on a banner accompanying Cortés in his Conquest of Mexico, currently in Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle museum. This image portrays a gentle, olive-skinned Mary with folded hands, her head slightly tilted to the left, with hair parted in the middle. A red robe drapes her body, and a crown with twelve stars rests on her mantle-covered head. This rendering of the Virgin Mary bears a striking resemblance to the famous representation of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe. The Italian historian Lorenzo Boturini (1702–1775) described Cortés’s banner thus: “A beautiful image of the Virgin Mary was painted on it. She was wearing a gold crown and was surrounded by twelve gold stars. She has her hands together in prayer, asking her son to protect and give strength to the Spaniards so they might conquer the heathens and christianize them” (quoted in Tlapoyawa 2000). According to Kurly Tlapoyawa, the Indian Markos Zipactli’s (Marcos Cipac de Aquino’s)  painting, which was placed at the Tepeyac temple, was based on Cortés’s banner. This image is also very similar to an eight-century Italian painting called Immaculata Tota Pulcra, [Image at right] and to a 1509 central Italian representation of the Madonna del Soccorso by Lattanzio da Foligno and by Francesco Melanzio. The expression of her face, the pattern of her robe and mantle, and the halo surrounding her body and crown are almost identical to those of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe. The difference is that on the Madonna del Soccorso paintings Mary is represented defending her child from the devil with a whip or a club. Moreover, Francisco de San José, in his Historia, affirms that the Mexican Guadalupe is a copy of a relief sculpture of Mary placed in the choir opposite the Spanish Guadalupe statue in her Villuercas sanctuary. On the other hand, Lafaye (1976:233) as well as Maza (1981:14) and O’Gorman (1991:9–10) believe that the original effigy placed by the Spaniards at Tepeyac was that of the Spanish Guadalupe, La Extremeña, which only years later was replaced by the Mexican Virgin. Lafaye supposes that the change of images corresponds to the change of the dates of the Guadalupe celebration in Mexico from December 8 or 10 to December 12: “we know for certain . . . that the substitution of the image took place after 1575 and the change of the feast day calendar after 1600” (Lafaye 1976:233). December 8 was the day of the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Villuercas, Spain, as well as that of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. Fray Bustamante’s sermon discussed previously further supports this view.

painting, which was placed at the Tepeyac temple, was based on Cortés’s banner. This image is also very similar to an eight-century Italian painting called Immaculata Tota Pulcra, [Image at right] and to a 1509 central Italian representation of the Madonna del Soccorso by Lattanzio da Foligno and by Francesco Melanzio. The expression of her face, the pattern of her robe and mantle, and the halo surrounding her body and crown are almost identical to those of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe. The difference is that on the Madonna del Soccorso paintings Mary is represented defending her child from the devil with a whip or a club. Moreover, Francisco de San José, in his Historia, affirms that the Mexican Guadalupe is a copy of a relief sculpture of Mary placed in the choir opposite the Spanish Guadalupe statue in her Villuercas sanctuary. On the other hand, Lafaye (1976:233) as well as Maza (1981:14) and O’Gorman (1991:9–10) believe that the original effigy placed by the Spaniards at Tepeyac was that of the Spanish Guadalupe, La Extremeña, which only years later was replaced by the Mexican Virgin. Lafaye supposes that the change of images corresponds to the change of the dates of the Guadalupe celebration in Mexico from December 8 or 10 to December 12: “we know for certain . . . that the substitution of the image took place after 1575 and the change of the feast day calendar after 1600” (Lafaye 1976:233). December 8 was the day of the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Villuercas, Spain, as well as that of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. Fray Bustamante’s sermon discussed previously further supports this view.

Whether appearing in person or on canvas, Guadalupe is clearly a syncretic figure, possessing both Catholic and Native Mesoamerican elements. Her original name comes from the Arabic wadi (riverbed) and Latin lupus (wolf) (Zahoor 1997). There have been speculations arguing that the Mexican Guadalupe’s name comes from the Nahuatl Cuauhtlapcupeuh (or Tecuauhtlacuepeuh), She Who Comes from the Region of Light as an Eagle of Fire (Nebel 1996:124), or Coatlayopeuh, the Eagle Who Steps on the Serpent (Palacios 1994:270). Curiously, Juan Diego’s name was Cuauhtlatonzin (or Cauhtlatoahtzin). Cuahtl means “eagle,” Tlahtoani is “the one who speaks,” and Tzin means “respectful.” This would suggest that Juan Diego was the Eagle Who Speaks, someone of a very high rank in the Order of Eagle Knights, continuing the mission of the last Aztec emperor Cuauhtemoc, the Eagle Who Descends (“Where Does the Name Guadalupe Come From?” 2000), but some scholars doubt the very existence of Juan Diego. Since the Nahuatl language does not include the sounds of “d” and “g,” the use of Guadalupe’s name with the above meaning may indicate a native adaptation of the Arab-Spanish word.

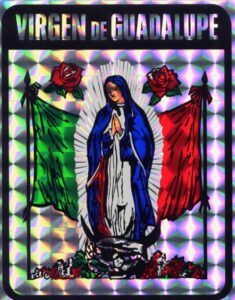

As to other particularities of the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe, her attire is of primary importance. Guadalupe’s mantle is not blue, a characteristic of the European Virgins, but turquoise or blue-green, which in Aztec mythology symbolizes water, fire, prosperity, and abundance. [Image at right] In native Mexican languages, such as Nahuatl, there is only one word for blue and green. Blue-green, jade, or turquoise was a sacred color and it was worn by the high priest of Huitzilopochtli. Turquoise is also the sacred color of the earth and moon Mother Goddess Tlazolteotl (Goddess of Filth), the water and fertility goddess Chalchutlicue (The One with a Skirt of Green Stones), and the fire and war god of the south, Huitzilopochtli. This god was believed to be “immaculately” conceived with a feather by his mother, the goddess Coatlicue (Lady of the Serpent Skirt). Blue is also the color of the south and of fire, and “in Mexican theological language ‘turquoise’ means ‘fire.’” On the other hand, the Virgin’s robe is red, signifying the east (rising sun), youth, pleasure, and rebirth (Soustelle 1959:33–85). Thus, the Aztec symbology of the main colors worn by Mary (red and blue-green) corresponds to her Christian duality as young virgin and mature mother. It is indeed remarkable that the skin tone of the faces of both Guadalupe and the angel are brown, as in the image of Cortés’s banner and the faces of the Indians themselves.

Additional correlations surface in prophetic literature between Guadalupe, the woman of the Apocalypse, and the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. According to the Book of Revelation, “there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and a moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown with twelve stars” (The Holy Bible). In her Mexican representations prior to the nineteenth century, Guadalupe also wore the crown with twelve stars, present on the image of Cortés’s banner. Later, the crown was eliminated. Obviously, the distinctive elements of the Apocalyptic woman were reproduced quite precisely in the Virgin of Guadalupe image, who also wears a starry mantle, a crown of twelve stars, is surrounded by the rays of the sun, and stands on the moon. These cosmic elements (the sun, the moon, and the stars) played an important part in the Aztec religion as well. In fact, Tonacaciuatl, the goddess of the upper skies and the Lady of Our Nutrition, was also called Citlalicue, the One with a Starry Skirt (Soustelle 1959:102). Other goddesses such as Xochiquetzal (Flowery Quetzal Feather), Tlazolteotl-Cihuapilli (Goddess of Filth-Fair Lady), Temazcalteci (Grandmother of the Bathhouse), Mayahuel (Powerful Flow, Lady Maguey), and Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina (Goddess of Filth-Lady Cotton) were represented with crescent-shaped adornments as part of their attire. Moreover, the passage from Revelation “And when the dragon saw that he was cast unto the earth, he persecuted the woman . . . And to the woman were given two wings of a great eagle, that she might fly to the wilderness, into her place, where she is nourished” (quoted in Quispel 1979:162) coincides with the Aztec foundational legend. The legend describes how the Aztecs were instructed to look for the sign of an eagle devouring a serpent while perched on a nopal cactus. The sign functioned as a divine indication of a permanent homeland, Tenochtitlan, for the nomadic people coming from the northern region of Aztlán. The eagle motif occurs frequently in Aztec mythology. For example, the goddess Ciuacoatl, or Wife of the Serpent (also identified with Tonantzin), appears in her warrior aspect adorned with eagle feathers:

The eagle

The eagle Quilaztli

With blood of serpents

Is her face circled

With feathers adorned

Eagle-plumed she comes

. . .

Our mother

War woman

Our mother

War woman

Deer of Colhuacan

In plumage arrayed

(“Song of Ciuacoatl,” Florentine Codex, Sahagún 1981, vol. 2: 236).

The association of the Virgin of Guadalupe with the eagle and the cactus may be seen in New Spain’s iconography as early as 1648, and it intensifies during the nationalist surge of the mid-eighteenth century.

The first historical references to the Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe devotion appeared in the form of essays by Miguel Sánchez in 1648 and Lasso de la Vega in 1649. According to Lafaye, “they had a special meaning . . . for they were the first step toward recognition of Guadalupe as a Mexican national symbol.” The Creole bachiller Sánchez created a prophetic vision of the Spanish Conquest, stating “that God executed his admirable design in this Mexican land, conquered for such glorious ends, gained in order that a most divine image might appear here.” As the title of the first chapter of his book, “Prophetic Original of the Holy Image Piously Foreseen by Evangelist Saint John, in Chapter Twelve of Revelation,” makes explicit, Sánchez draws a parallel between the appearance of Guadalupe at Tepeyac and Saint John’s vision of the Woman of the Apocalypse at Patmos (Lafaye 1976:248–51). Eighteenth-century paintings, such as Gregorio José de Lara’s Visión de san Juan en Patmos Tenochtitlan and the anonymous Imagen de la Virgen de Guadalupe con san Miguel y san Gabriel y la visión de san Juan en Patmos Tenochtitlan, illustrate Saint John’s vision of a winged Guadalupe and of a Guadalupe accompanied by the Aztec eagle at the Tepeyac hill. By providing a parallel not only between the Woman of the Apocalypse and Guadalupe but also between Patmos and Tenochtitlan, local painters portrayed Mexico as a chosen land. This idea was also reflected in poetry. In 1690, Felipe Santoyo wrote:

Let the World be admired;

the Sky, the Birds, the Angels and Men

suspend the echoes,

repress the voices:

because in New Spain

about another John it is being heard

a new Apocalypse,

although the revelations are different! (quoted in Maza 1981:113)

It is evident that “the identification of Mexican reality with the Holy Land and the prophetic books,” as well as statements such as “I have written [this book] for my patria, for my friends and comrades, for the citizens of this New World” and “the honor of Mexico City . . . the glory of all the faithful who live in this New World” (quoted in Lafaye 1976:250–51), make Miguel Sánchez a Creole patriot whose writings had important consequences for the emancipation of Mexico. Developments in the iconography reflecting Mexican history make it apparent that the Virgin of Guadalupe has gained increasing agency in the social and political realms.

There certainly was a need for a powerful protective entity among the populace of New Spain. From the late seventeenth century to the mid-eighteenth century, thousands fell victim to yearly calamities such as floods, earthquakes, and epidemics. There was also an urgency for the appearance of a native symbolic figure, one that could reconcile and fraternize the diverse racial, ethnic, cultural, and class components of Mexico, serve the purpose of identification, and instill national pride. The historical perspective explains why Guadalupe becomes a presence sine qua non during colonial times; there is no important image or event from which she may be omitted. The nineteenth-century Mexican historian Ignacio Manuel Altamirano made reference to the 1870 Guadalupe celebrations when he wrote that the worship of Guadalupe united “all races . . . all classes . . . all castes . . . all the opinions of our politics . . . The cult of the Mexican Virgin is the only bond that unites them” (quoted in Gruzinski:199-209).

This increase in devotion to Guadalupe responded to a need by Creoles to find a feature of their own that would clearly distinguish them from the Spaniards: “[T]here will be then the Creoles, who in the seventeenth century will give a definitive position in history to guadalupanismo” (Maza 1981:40). As a consequence, the first Spanish sanctuary was built at Tepeyac in 1609. As early as 1629 the image of Guadalupe was carried in solemn procession from Tepeyac to Mexico City by pilgrims who implored her to deliver the population from the menace of floods. Having achieved this goal, Guadalupe was proclaimed the city’s “principal protectress against inundations,” and she “achieved supremacy over the other protective effigies of the city” (Lafaye 1976:254). By the end of the seventeenth century, a legend was added to the image of Guadalupe, thus making her emblem complete. The legend, Non fecit talliter omni nationi ([God] Has Not Done the Like for Any Other Nation), was taken by Father Florencia from Psalm 147. It became attached to the sacred image (Lafaye 1976:258), further reinforcing its national character. But it wasn’t until the mid-eighteenth century that Guadalupe became the center of collective fervor. In 1737 the effigy was proclaimed the official patroness of Mexico City, and, in 1746, of all of New Spain. In 1754, Pope Benedict XIV confirmed this oath of allegiance, and Guadalupe’s holiday was established in the Catholic calendar (Gruzinski 1995:209).

Our Lady of Guadalupe also played an important role in the Mexican War of Independence from Spain (1810–1821). She was then carried on banners of the insurgents, led by Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and later by Father José María Morelos, confronting the Spanish royalists who carried the Peninsular Virgen de los Remedios. The first president of independent Mexico changed his name from Manuel Félix Fernández to Guadalupe Victoria in homage to the patriotic Virgin. Other Mexican political and social struggles, such as the War of Reformation (Guerra de la Reforma, 1854–1857), the Mexican Revolution (1910–1918), and the Cristeros Rebellion (1927–1929), were also performed under the banners of Guadalupe (Herrera-Sobek 1990:41–43). The process of exaltation of the Virgin of Guadalupe and of Juan Diego continues. On July 30, 2002, Pope John Paul II canonized the Mexican Indian, declaring him an official saint of the Catholic Church. This was done in spite of the fact that even some Mexican Catholic priests, such as father Manuel Olimón Nolasco, doubt the actual existence of Juan Diego (Olimón Nolasco 2002:22). In turn, on December 1, 2000, after being sworn in as the new Mexican president, Vicente Fox directed his first steps to the Virgin of Guadalupe Basilica at the Tepeyac hill, where he asked the Virgin for grace and protection during his presidency. This constituted an unprecedented case in Mexican politics (“Fox empezó la jornada en la Basílica” 2000), as a strong division between church and state has been officially enforced since the Mexican Revolution. Once again, the Virgin of Guadalupe claimed victory over official customs and rules.

From the onset, the patriotic significance of the Virgin of Guadalupe was exhibited in iconography and other artistic expressions. As her image achieved increasing national and political significance, it was placed above the Aztec coat of arms (the eagle devouring a serpent on a nopal (prickly pear) and Mexico City-Tenochtitlan. Sometimes the image was framed by allegorical figures representing Americas and Europe, as in the eighteenth-century painting Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de México, Patrona de la Nueva España (Our Lady of Guadalupe, Patron of New Spain) (see Cuadriello, Artes de México 52). In  Josefus de Ribera i Argomanis’s 1778 painting Verdadero retrato de santa María Virgen de Guadalupe, patrona principal de la Nueva España jurada en México (Real Portrait of Holy Mary Virgin of Guadalupe, Main Patron of New Spain Sworn in Mexico), her image was framed by a non-Christianized Indian representing America, and Juan Diego, a European-influenced one. In contemporary art, we see the progressive Mexicanization of Guadalupe reflected in the use of the colors of the Mexican flag (red, green, and white) as well as in the darkening and the Indianization of her features. [Image at right]

Josefus de Ribera i Argomanis’s 1778 painting Verdadero retrato de santa María Virgen de Guadalupe, patrona principal de la Nueva España jurada en México (Real Portrait of Holy Mary Virgin of Guadalupe, Main Patron of New Spain Sworn in Mexico), her image was framed by a non-Christianized Indian representing America, and Juan Diego, a European-influenced one. In contemporary art, we see the progressive Mexicanization of Guadalupe reflected in the use of the colors of the Mexican flag (red, green, and white) as well as in the darkening and the Indianization of her features. [Image at right]

Thus, Guadalupe played an important role in Mexican struggles for independence from foreign aggressors, for freedom, and for social justice.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The veneration of Our Lady of Guadalupe, also called the Virgin of Guadalupe, is part of the Catholic religion, and Guadalupe is one of the manifestations of the Virgin Mary (Mother of God). She is believed to be the one who gave birth to the Savior, Jesus Christ, conceived in a miraculous manner, without the intervention of man. Mary herself is also believed to be conceived in an immaculate way, thus one of her expressions is called the Immaculate Conception. Among the myriad of other manifestations, there is the Virgin of the Pillar, of El Carmen, of Montserrat, of Fatima, of Sorrows, of Regla, of Częstochowa, etc. Some of them are black, some brown, and others white. Sometimes the Virgin is portrayed seated with her divine child on her lap, and at others she is standing alone; nevertheless, all her images refer to the same historical Mary who lived in Nazareth and gave birth to Jesus at Bethlehem, at the beginning of the Common Era. Devotees venerate the Virgin as Guadalupe, often above any other divinity of the church, and place her images and altars in their homes. They see her as a protective mother who is always there for them, feeds them and shields them from danger, especially in times of wars and calamities. This phenomenon happens across social classes, but is especially notable among disenfranchised population who experience hardships and great need. This isn’t a new tradition, as the Virgin is a heir to the Great Goddess of Life, Death, and Regeneration as the mother who feeds and protects their children, but also receives them at death.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The rituals for the Virgin of Guadalupe are the same ones practiced for all Virgin Marys, and they include Rosaries, Novenas, and masses. Specifically, there is a huge, yearly international pilgrimage to her basilica at the Tepeyac hill in Mexico City, in which people of all nationalities and walks of life arrive, often after walking for weeks, and sometimes on their knees, in order to give her homage on December 12, the day of her feast. This is the most-visited Catholic shrine in the world (Orcult 2012). Another frequent practice are the petitions, promises (votos) and the offering of ex-votos, objects dear to the devotees who were granted favors by the Virgin. They include jewels, crutches, and symbolic  representations of the afflictions that were cured, or of the favors granted. She appears on portraits and altars, both in churches and other public spaces, as well as in the intimacy of people’s homes. Oftentimes, she is the object of shrines in front of private homes, on buildings, and on public roads. [Image at right]

representations of the afflictions that were cured, or of the favors granted. She appears on portraits and altars, both in churches and other public spaces, as well as in the intimacy of people’s homes. Oftentimes, she is the object of shrines in front of private homes, on buildings, and on public roads. [Image at right]

She offers protection and guidance to the faithful and is believed to be very miraculous. Although her devotion is officially part of Catholicism, it trespassed the boundaries of religion, and in many cases the cult to the Virgin of Guadalupe stands by itself, regardless of the faith of the devotees. Our Lady is believed to be the purest of women and her symbol is a rose-colored rose.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The organization and leadership of the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe occurs within the Catholic Church structure, but specific groups, such as the Guadalupanas, and those that organize the Rosaries and other events in her honor, are often led by women devotees. Sociedades Guadalupanas (Guadalupe Societies) are Catholic religious associations funded by Mexican American women in 1942 (“Guadalupanas”; “Sociedades Guadalupanas”). The most important Guadalupe day is December 12, the Feast of Guadalupe, when millions of pilgrims visit her basilica in Mexico City, but also in many other places locally. There is an extensive network of named Guadalupe churches, shrines, and chapels especially in Mexico, Latin America, the United States. The basilica in Mexico City that houses the miraculous portrait of Guadalupe imprinted on Juan Diego’s tilma (cloak) that allegedly withstood ca. 500 years without damage, is the most-visited Catholic site in the world. Since the mid-eighteenth century, when Our Lady of Guadalupe was declared the official patroness of New Spain, and her official holiday was established, she has been the object of numerous endorsements by different popes. She was crowned on her feast day in 1895, and was declared the patroness of Latin America in 1910, and of the Philippines in 1935. In 1966, she was granted a symbolic golden rose by pope Paul VI, and in 2013 by pope Francis. Pope John Paul II canonized Juan Diego in 2002, and declared Our Lady of Guadalupe Patroness of the Americas (“Our Lady of Guadalupe”).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

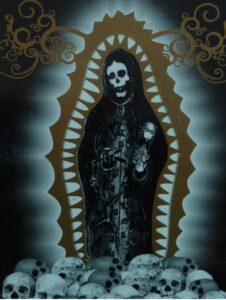

Since the inception of the Virgin of Guadalupe devotion, there has been a controversy between aparicionistas and antiaparicionistas, as described above. The former firmly believe in the miraculous apparitions of Guadalupe at the Tepeyac Hill in 1531. The latter claim that her new image was commissioned to the Indigenous artist Marcos Cipac de Aquino who painted her following traditional images of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, including Mexico’s conqueror Hernán Cortés banner. In this latter view,  her persona and devotion were constructed for the purpose of Christianization during colonial times. Later, she served as a unifying force for the multiethnic Mexican nation and the enhancement of feelings of patriotism. In addition, the contemporary transformations and appropriations of her image, mainly by U.S. Chicanx groups, to convey political, social, or feminist ideas, are often met with great controversy, and the rejection of the church and traditional Catholics. A development of the past twenty years is the competition between Guadalupe and unofficial saints, particularly La Santa Muerte, [Image at right] whose following is greatly increasing. Many devotees feel abandoned by and mistrust official church and state institutions, and prefer to pray to powerful holy figures that don’t judge them and do not require intermediaries, such as La Santa Muerte (see Oleszkiewicz-Peralba 2015:103-35).

her persona and devotion were constructed for the purpose of Christianization during colonial times. Later, she served as a unifying force for the multiethnic Mexican nation and the enhancement of feelings of patriotism. In addition, the contemporary transformations and appropriations of her image, mainly by U.S. Chicanx groups, to convey political, social, or feminist ideas, are often met with great controversy, and the rejection of the church and traditional Catholics. A development of the past twenty years is the competition between Guadalupe and unofficial saints, particularly La Santa Muerte, [Image at right] whose following is greatly increasing. Many devotees feel abandoned by and mistrust official church and state institutions, and prefer to pray to powerful holy figures that don’t judge them and do not require intermediaries, such as La Santa Muerte (see Oleszkiewicz-Peralba 2015:103-35).

IMAGES

Image #1: Our Lady of Guadalupe, Villuercas, Spain (From the archives of the late Antonio D. Portago).

Image #2: Immaculata Tota Pulchra, Italy, 8th Century.

Image #3: Virgin of Guadalupe, Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City.

Image #4: Virgin of Guadalupe with the colors of Mexican flag. Photograph by author.

Image #5: Street altar of Guadalupe. El Paso Street, San Antonio, Texas. Photograph by author.

Image #6: Santa Muerte as Our Lady of Guadalupe. Cover, La biblia de la santa muerte.

REFERENCES

Unless otherwise noted, the material in this profile is drawn from The Black Madonna in Latin America and Europe: Tradition and Transformation (University of New Mexico Press 2007, 2009, and 2011). All translations in this text are by the author.

Cuadriello, Jaime, comp. n.d. Artes de México 29: Visiones de Guadalupe. Santa Ana, CA: Bowers Museum of Cultural Art.

Cuadriello, Jaime. n.d. “Mirada apocalíptica: Visiones en Patmos Tenochtitlan, La Mujer Aguila.” Cuadriello 10–23.

“Fox empezó la jornada en la Basílica.” 2000. Diario de Yucatán, December 2, February 7, 2003. Accessed from http://www.yucatan.com.mx/especiales/tomadeposesion/02120008.asp on 5 April 2022.

“Guadalupanas.” 2022. Immaculate Heart of Mary Church, April 6. Accessed from http://ihmsatx.org/guadalupana-society.html on 5 April 2022.

Gruzinski, Serge. La guerra de las imágenes: De Cristóbal Colón a “Blade Runner” (1492–2019). 1994. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1995.

Herrera-Sobek, María. 1990. The Mexican Corrido. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

The Holy Bible. n.d. King James version. Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company.

La Biblia de la Santa Muerte. n.d. Mexico: Ediciones S.M.

Lafaye, Jacques. Quetzalcóatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813. 1974. Translated by. Benjamin Keen. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

Maza, Francisco de la. El gaudalupanismo mexicano. 1981 [1953]. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Nebel, Richard. 1996 [1995] Santa María Tonantzin Virgen de Guadalupe. Translated by Carlos Warnholtz Bustillos. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1996.

Nebrija, Antonio de. 1926. Gramática de la lengua castellana (Salamanca, 1492): Muestra de la istoria de las antiguedades de España, reglas de orthographia en la lengua castellana. Edited by Ig. González-Llubera. London and New York: H. Milford and Oxford University Press.

O’Gorman, Edmundo. 1991. Destierro de sombras: Luz en el origen de la imagen y culto de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Tepeyac. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Oleszkiewicz-Peralba, Małgorzata. 2018 [2015]. Fierce Feminine Divinities of Eurasia and Latin America: Baba Yaga, Kali, Pombagira, and Santa Muerte. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY.

Olimón Nolasco, Manuel. 2002. “Interview.” Gazeta Wyborcza. July 27–28.

Orcult, April. 2012. “World Most-Visited Sacred Sites.” Travel and Leisure, January 4. Accessed from travelandleisure.com on 6 April 2022.

“Our Lady of Guadalupe Patron Saint of Mexico.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed from britannica.com on 4 April 2022.

Palacios, Isidro Juan. 1994. Apariciones de la Virgen: Leyenda y realidad del misterio mariano. Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy.

Quispel, Gilles. 1979. The Secret Book of Revelation. New York: McGraw-Hill,.

Sahagún, Fray Bernardino de. Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain. Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson. Santa Fe, NM: School for American Research; Salt Lake City: University of Utah, book 1, 1950; book 2, 1951 (Second Edition, 1981); books 4 and 5, 1957 (Second Edition, 1979); book 6, 1969 (Second Edition, 1976).

Quispel, Gilles. 1956. Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España. 4 Volumes. 1938. Edition. Angel María Garibay K. Mexico City: Porrúa.

“Sociedades Guadalupanas.” 2022. TSHA Texas State Historical Association. Accessed from tshaonline.org on 6 April 2022.

Soustelle, Jaques. 1959. Pensamiento cosmológico de los antiguos mexicanos. Paris: Librería Hermann y Cia. Editores.

Tlapoyawa, Kurly. 2000. “The Myth of La Virgen de Guadalupe.” Accessed from http://www.mexica.org/Lavirgin.html on 24 February 2003.

“Where Does the Name Guadalupe Come From?” 2000. The Aztec Virgin. Sausalito, CA: Trans-Hyperborean Institute of Science. Accessed from http://www.aztecvirgin.com/guadalupe.html on 3 March 2003.

Torre Villar, Ernesnto de la, and Ramiro Navarro de Anda, comps. and eds. 1982. Testimonios históricos guadalupanos. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Zahoor, A. 1997 [1992]. Names of Arabic Origin in Spain, Portugal and the Americas. Accessed from http:cyberistan.org/islamic/places2.html on 15 March 2003.