LOST CAUSE MOVEMENT TIMELINE

1860 (November 6): Abraham Lincoln was elected the sixteenth president of the United States and the first from the Republican Party.

1860 (December) – 1861 (January): The first seven states seceded from the Union.

1861 (February): The secessionist states organized the Confederate States of America in Montgomery, Alabama. Jefferson Davis was appointed its first President.

1861 (March 4): Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated in Washington, D.C.

1861 (March 11): The Confederate Constitution was ratified.

1861 (April 12): Southern naval forces initiated the Civil War with an attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

1861 (April 15): President Lincoln declared an insurrection and called for mobilization of Union military forces.

1862: Jefferson Davis, became a member of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia.

1865 (December 24): The Ku Klux Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee.

1865 (April 3): Jefferson Davis was informed that Confederate forces were unable to defend Richmond and ordered a fire to be set in the city that would destroy potential supplies for advancing Union forces.

1865 (April 9): General Robert E. Lee formally surrendered Confederate forces to General Grant at Appomattox Court House.

1865 (April 14): President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth.

1870 (January 26): The Commonwealth of Virginia was readmitted to the United States and military forces were withdrawn.

1877: The informal Compromise of 1877 secured the election of Republican candidate Rutherford Hayes, initiating a period of white political control throughout the South what has been referred to as the Jim Crow Era.

1894: The United Daughters of the Confederacy was formed in Nashville, Tennessee and later headquartered in Richmond, Virginia.

1896 (February 22): The Confederate Museum (later the Museum of the Confederacy) was established.

1924 (May 21): A statue honoring Robert E. Lee astride his horse, Traveller,” that was donated by Paul Goodloe McIntire was unveiled in a segregated city park in Charlottesville, Virginia.

1970 The Confederate Museum changed its name to the Museum of the Confederacy as part of an initiative designed to assume a more contemporary museum posture.

2013: The American Civil War Museum was created by a merger between the American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy.

2012 (February 26): Seventeen year-old Trayvon Martin was shot and killed by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida.

2013 (November): The Museum of the Confederacy and the American Civil War Center at Tredegar merged to create the American Civil War Museum. The new name was announced the following year.

2013: The Black Lives Matter movement emerged following the acquittal of George Zimmerman on murder and manslaughter charges in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin.

2014 (July 17): Forty-three-year-old Eric Garner was killed in the Staten Island borough of New York City borough after, a New York City Police Department officer, Daniel Pantaleo, was placing him under arrest.

2014 (August 9): Eighteen year-old Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by a white Ferguson police officer, Darren Wilson, in Ferguson, Missouri.

2015 (June 17): Dyllan Roof killed nine African-American parishioners during a Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

2015: The 2015 Episcopal Church’s General Convention passed a resolution that called for the universal discontinuation of display of the Confederate Battle Flag.

2015: Washington National Cathedral announced that it was removing Confederate battle flags from two windows in the cathedral honoring Confederate generals.

2017 (August 11-12): In Charlottesville, Virginia, at a Unite the Right rally associated with the Alt-Right movement that opposed the removal of a Robert E. Lee memorial Statue an Alt-Right supporter, James Fields, drove his vehicle into a crowd of counter-protestors, killing Heather Heyer and injuring nineteen other individuals.

2020 (May 25): Forty-six year-old George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, Minnesota by a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, who was later convicted and imprisoned.

2020 (and after): Removal of Confederate symbols (monuments, named buildings, statues, streets) in public space and buildings continued to accelerate throughout the United States.

2021 (January 6): Numerous confederate flags were visible during the insurrection and the U.S. Capitol.

2021 (July): The Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia was removed from its public park setting.

2021 (September): The Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia was removed from its plinth.

2023 (April): The Governor of Mississippi proclaimed April as Confederate History Month.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

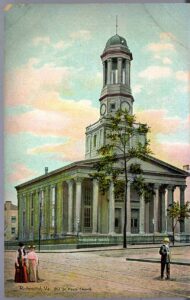

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the Union was fragmented, beset by what Taylor (2021) refers to as “rival regions.” While slavery was not the only division facing a fragile Union, the nation was deeply divided sectionally over slavery in 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected the sixteenth president of the United States and its first Republican. The Republican Party generally opposed the extension of slavery into U.S. territories. Signaling the deep political division in the nation, Lincoln was  elected with less than forty percent of the popular vote and did not received significant support in any state that would become part of the Confederacy. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1860 seven southern states had seceded, the Confederate States of America had been formed, and within a month the Civil War had commenced with the southern naval attack on Fort Sumpter. [Image at right]

elected with less than forty percent of the popular vote and did not received significant support in any state that would become part of the Confederacy. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated in March 1860 seven southern states had seceded, the Confederate States of America had been formed, and within a month the Civil War had commenced with the southern naval attack on Fort Sumpter. [Image at right]

Religion was an important component of the north-south division during the Civil War. The situation was fluid and conflicted. There were conflicts within the major Protestant denominations that led to north-south denominational divisions, as well as ongoing intra-denominational divisiveness. Organizational turmoil within and between religious groups was exacerbated by military ebb and flow, and the ability of churches even to hold services varied depending on which military force controlled the territory on which they were situated. Not all of these divisions were permanent. In the case of the Episcopal Church, for example, the division began in 1861, when the southern component became the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, but ended shortly after the war in 1866, with Bishop John Johns leading the campaign for reunification.

In addition to the broad North-South division and disputes and schisms within institutional religion, there was also persistent and determined religiously-based resistance to the foundational premises on which the Confederacy was based. The slave population’s version of Christianity featured themes of freedom, redemption and punishment for their oppressors and was practiced at their secret “hush harbors.” This resistance to assertions of the legitimacy of slavery by enslaved populations only served to intensify efforts by whites to shore up their ideology (Irons 2008).

Denominational disputes notwithstanding, religious fervor surged on both sides during the war. Missionaries and colporteurs spread the gospel to troops, and revivals broke out on both sides periodically during the second half of the war. For example, the Army of Northern Virginia enjoyed its greatest revivals in the spring and summer of 1863. Newspapers published reports of a surge in church attendance and even mass conversions (Irons 2020). A newspaper in Tennessee reported that “immense congregations assembled to hear the word … and many sinners led to cry for mercy; a chaplain informed me that 1,000 men in his division had professed the faith.” In Richmond in 1864, the Richmond Daily Dispatch reported that “the religious interest in the army is unchilled by the cold weather. Meetings are still held in every part of the army; and in many, if not all the brigades, meeting-houses have been constructed for their own use, and faithful chaplains nightly preach to large and deeply attentive congregations” (Stout 2021).

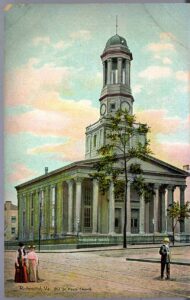

Events on April 3, 1865 signaled an impending conclusion to the Civil War. Reportedly, while in attendance at St. Paul’s, Jefferson Davis was informed that Confederate forces were unable to defend Richmond any longer. Davis left the church and ordered what became known as “the fire” be set in the city of Richmond to destroy supplies potentially useful to advancing Union forces. However, the fire raged out of control, ultimately destroying about 800 buildings in the city. [Image at right] The railroad bridge across the James River was also burned to slow the Union army advance (Slipek 2011). Just six days later, on April 9, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his forces to General Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Appomattox Court House in Appomattox County, Virginia, effectively ending Civil War combat.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the eleven secessionist states faced massive dislocation as a product of military defeat, mass loss of life (well over 300,000 military deaths and probably twice that number of total casualties), political submission, an economy (an agricultural plantation system and captive labor force) and infrastructure (roads, bridges, harbors, railway systems) that had collapsed, and a culture and way of life that was in chaos.

The process referred to as Reconstruction actually began prior to the end of the war, with a combination of national legislation and constitutional amendments on one side and legal and extra-legal maneuvering to replace slavery with racial segregation on the other side. 1877 was a watershed year with the implementation of the informal Compromise of 1877, which resolved an impasse in the 1876 presidential election, removed remaining federal control over southern states, and resulted in solid democratic control in the former states of the Confederacy. What followed was what has been referred to as the Jim Crow era in which racial segregation replaced slavery as a form of control.

Following the end of the war, the economic base in southern states began to shift. As Hillyer has observed (2007:193-94):

As early as 1869, despite the residual animosity of the Civil War and political upheaval of Reconstruction, business-oriented Southerners advertised the wealth of untapped natural resources in the South and courted Northerners for capital and expertise…. Southern industrialists perceived economic diversification as a means towards regional self-sufficiency.

Whereas in antebellum Richmond the interests of the commercial elite were complementary to, if not dependent upon, the plantation economy, the “new race” of Richmond exemplified the rising class of businessmen and industrialists who owed their growing economic power to allegiances with northern business interests. This “new race” sought to promote an era of national reconciliation and a climate favorable to business and industrial expansion.

However, as Rawls (2017) has noted, reconstruction and economic development would be achieved while preserving white supremacy. Slavery was replaced by segregation in former Confederate states. Over the next century, control over state and local government created a formal legal and political framework for white political control. Extra-legal enforcement was provided by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. The KKK was formed in Tennessee as the war was ending; the first Grand Wizzard was Nathan Bedford Forrest, a former Confederate general and wealthy slave trader. The KKK employed tactics ranging from voter intimidation to lynching in defense of white supremacy. The KKK was one of the sources of the 4,000 lynchings and other executions of African Americans over this century (Bill of Rights Institute 2022). “Lost Cause” emerged in southern states as a revisionist history and legitimating narrative for racial suppression, one that was supported by an active network of organizations in southern states (Domby 2020).

DOCTRINES/RITUALS

Like Reconstruction, sacralization of the southern cause actually began before the end of the war. For example, a sermon preached on Thanksgiving Day 1861 at historic St. John’s Episcopal Church in Richmond asserted that (Stout 2021):

God has given us of the South today a fresh and golden opportunity—and so a most solemn command—to realize that form of government in which the just, constitutional rights of each and all are guaranteed to each and all. … He has placed us in the front rank of the most marked epochs of the world’s history. He has placed in our hands a commission which we can faithfully execute only by holy, individual self-consecration to all of God’s plans.

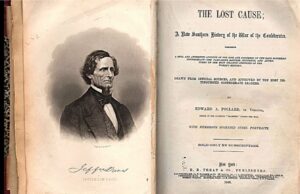

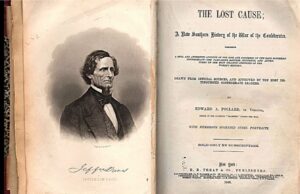

As it developed, the Lost Cause served as a means of retrospectively redefining the meaning and outcome of the Civil War. [Image at right] Military defeat became moral victory. As one veteran who fought for the Confederacy put the matter, “If we cannot justify the South in the act of Secession, we will go down in History solely as a brave, impulsive but rash people who attempted in an illegal manner to overthrow the Union of our Country” (Williams 2017).

The mythology contained several key elements (Wilson 2009; Janney 2021; Williams 2017):

At the center of the myth is the assertion that secession was not about slavery at all; rather, secession was a constitutionally legitimate process, a protection of states’ rights, and a defense of agrarian southern culture against the northern infidels. The Confederacy preferred to refer to the Civil War as the War between the States. Confederate states asserted that secession was an institutional right of every state. In that sense secession was viewed in many ways akin to the original American revolution as a fight against tyranny. The disavowal of slavery as the central element of secession was belied by its prominence the declarations of secession in a number of Confederate states.

In Lost Cause mythology, slavery was benevolent. Slaves were depicted as happy with their status, faithful to the masters, protected within the plantation system, and unprepared for the responsibilities of living independently. Christianizing the slaves was presented as part of southerners’ religious mission. In fact, slaves are depicted as not only accepting their status but also as standing with their owners in resisting northern aggression (Levin 2019).

The Confederacy in the Lost Cause myth was not understood to have been so much defeated as simply overwhelmed. The North possessed a numerical and technological advantage of such magnitude that even determined resistance and enormous sacrifice was insufficient to win the day. However, the moral superiority of southern society and culture would ultimately prevail.

In this narrative, Confederate soldiers were portrayed as valiant and heroic defenders of their way of life, with General Robert E. Lee being its sanctified leader. For their part, women in the Confederacy were saintly figures who made enormous sacrifices for the cause (Janney 2008, 2021). Women were particularly prominent and critical to the cause since so many men were serving in the Confederate army or had been killed in battle.

The myth has remained publicly visible through more recent American history. For example, at the beginning of World War I when then President Woodrow Wilson, who was seeking to assemble a large wartime army, spoke at a gathering of the United Confederate Veterans in Arlington National Cemetery. He stated that (Paradis 2020):

There are many memories of the Civil War that thrill along the blood and make one proud to have been sprung of a race that could produce such bravery and constancy.” To a standing ovation of applause and rebel yells, Wilson warmly recalled how “heroic things were done on both sides.

In 1948, the Confederate flag was adopted by the Dixiecrat Party, led by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurman, which withdrew from the Democratic Party in response to the Democrats’ more progressive stance on civil rights issues.

In 1962, a Confederate flag was placed outside of the statehouse in South Carolina as a response to the Civil Rights Movement.

In 2007, in Richmond, Virginia, a year-long celebration of Robert E. Lee’s two hundredth birthday was planned that included a restoration of his Monument Avenue, a memorial ceremony at his birthplace, and a symposium at Washington and Lee University (Sampson 2007; Bohland 2006:3).

In 2023, the Governor of Mississippi proclaimed April as Confederate History Month.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

At the end of the Civil War Southerners were faced with responding to their disempowered circumstances. Symbolically, they faced the option of acknowledging that their social order was based on systematic oppression and exploitation through slavery or recasting the war as a moral victory, a sacred struggle to maintain their superior cultural heritage and resist northern aggression. Lost Cause represented the latter response. Local and state Jim Crow legal provisions created a set of social mechanisms through which voting restrictions and racial segregation replaced slavery so that white supremacy was asserted and maintained. For example, in Virginia the state constitution was amended in 1902 to impose poll taxes and require literacy and understanding provisions for voting eligibility. Extra-legally, mob violence and lynching functioned to suppress resistance. For example, the number of lynchings, virtually none of which resulted in legal prosecution, has been estimated at about 4,000 between 1877 and 1950 (Wolfe 2021; Equal Justice Initiative 2017).

Support for Lost Cause was organized through a loosely-coupled movement that included organizations such as churches, memorial groups, museums, cemeteries, history education monitoring groups, veterans organizations, and newspapers. These groups shared in common a goal controlling physical, social and cultural space. The movement was remarkably determined and successful for a considerable period in post-Civil War history. It surged during surged between 1877 following the Compromise of 1877 and World War I and again during the 1950s and 1960s in response to the civil rights movement. The current resurgence is linked to initiatives designed to eliminate Lost Cause memorialization (See, Issues/Challenges).

Memorialization is a power creation and consolidation strategy and was one of the primary ways that Lost Cause narrative was promoted (Anderson 1983; Hobsbawm and Ranger 1983). For example, monuments, particularly those in public spaces, connected present and past and created symbolic ownership of those spaces. There have been well over 1,000 memorials of various kinds created in the United States since the end of the Civil War, even if predominantly in states comprising the Confederacy. These memorials have often been constructed using public funds. Palmer and Wessler (2018) report that between 2008 and 2018 over $40,000,000 of public funds was spent on such projects and the organizations that organize them. As the American Historical Association described the process of monument construction (2017):

The bulk of the monument building took place not in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War but from the close of the 19th century into the second decade of the 20th. Commemorating not just the Confederacy but also the “Redemption” of the South after Reconstruction, this enterprise was part and parcel of the initiation of legally mandated segregation and widespread disenfranchisement across the South. Memorials to the Confederacy were intended, in part, to obscure the terrorism required to overthrow Reconstruction, and to intimidate African Americans politically and isolate them from the mainstream of public life. A reprise of commemoration during the mid-20th century coincided with the Civil Rights Movement and included a wave of renaming and the popularization of the Confederate flag as a political symbol.

Across the country, the Daughters of the Confederacy, which was headquartered in Richmond, sponsored hundreds of commemorative monuments beginning in the late nineteenth century (Breed 2018).

Two major Lost Cause monuments were the Stone Mountain Project outside of Atlanta, Georgia and Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia. The Stone Mountain Project was originally envisioned as a memorial to the Confederacy. There was to be a mountainside sculpture of Confederate soldiers on  horseback riding with members of the Ku Klux Klan (Lowery 2021). The site became a state park in 1958, the sculpture was completed In 1972. The memorial ultimately took the form of a carving of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson astride their horses. [Image at right] The Ku Klux Klan held cross burning rituals at the summit on several occasions through the early 1960s. The U.S Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp in 1970. For many years Stone Mountain was the most popular tourist destination in Georgia.

horseback riding with members of the Ku Klux Klan (Lowery 2021). The site became a state park in 1958, the sculpture was completed In 1972. The memorial ultimately took the form of a carving of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson astride their horses. [Image at right] The Ku Klux Klan held cross burning rituals at the summit on several occasions through the early 1960s. The U.S Postal Service issued a commemorative postage stamp in 1970. For many years Stone Mountain was the most popular tourist destination in Georgia.

Monument Avenue in Richmond combined memorialization with residential segregation. The avenue grew out of a post-war search for a memorialization site for Robert E. Lee, and was given momentum by the “City Beautiful” movement of that era. It became a segregated upper-status residential development project in Richmond’s West End. The development included restrictive covenants that prohibited sale of properties to buyers of “African descent.” The City of Richmond added several restrictive ordinances that buttressed  impediments to integrated residential areas in the first decades of the twentieth century. The first memorial statue, Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller, was dedicated in 1890. [Image at right] The dedication attracted a gathering of over 100,000 attendees. Monuments subsequently were added to other military leaders of the Confederacy: J.E.B. Stuart and Jefferson Davis in 1907 and Stonewall Jackson in 1919.

impediments to integrated residential areas in the first decades of the twentieth century. The first memorial statue, Robert E. Lee on his horse Traveller, was dedicated in 1890. [Image at right] The dedication attracted a gathering of over 100,000 attendees. Monuments subsequently were added to other military leaders of the Confederacy: J.E.B. Stuart and Jefferson Davis in 1907 and Stonewall Jackson in 1919.

While memorial monuments to the Confederacy have been contested and removed in recent years, new additions also have been made. Between 2000 and 2017, thirty-two new monuments were dedicated (Holpuch and Chalabi 2017).

Churches were an important component of legitimating Lost Cause mythology. Confederate imagery was frequently found in church sanctuaries across the south during that last half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. Episcopalians were particularly prominent in this regard: because “the Episcopal church was the church of the antebellum planter class” (Wilson 2009:35). The denomination established the National Cathedral in Washington, and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia became known as the Cathedral of the Confederacy. As Griggs (2017:42) notes:

Of all of Richmond’s churches, none was more closely associated with the Southern Confederacy than St. Paul’s. President Jefferson Davis worshipped there, as did Robert E. Lee when he was in Richmond….On many Sundays, St. Paul’s was filled with soldiers in gray and many women dressed in black to symbolize that they had lost a loved one.

Davis became a member of the congregation in 1862. It was Episcopal Bishop John Johns who baptized Jefferson Davis in the Executive Mansion of the Confederacy and confirmed him in St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Most of the St. Paul’s congregation at that time were involved in the slavery economy in some fashion.

At St. Paul’s, it became popular during the 1890s to memorialize family members with wall plaques in the sanctuary, some of which featured Confederate battle flags (Kinnard 2017). The church erected memorials to Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis in the 1890s and embraced the “Lost Cause”narrative (Wilson 2009:25). In an 1889 mural, for example, a youthful Moses is presented in a way that resembles Robert E. Lee as a young officer in the Confederacy (Chilton 2020). The accompanying inscription read:

By faith Moses refused to be called the son of Pharoah’s Daughter choosing rather to suffer affliction with the Children of God for he endured as seeing Him who is invisible. In grateful memory of Robert Edward Lee born January 19 1807.

Another way that Lost Cause proponents sought cultural legitimacy, one which had broad social impact, was through control of the secular presentation of the Civil War history in textbooks and library collections. Early in the twentieth century, the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and United Confederate Veterans (UCV) created a “Historical Committee,” which had as its mission to combat “long-legged Yankee lies,” and to “select and designate such proper and truthful history of the United States, to be used in both public and private schools of the South,” and to “put the seal of their condemnation upon such as are not truthful histories” (McPherson 2004:87).

One leader of this formidable effort was Mildred L. Rutherford, a Georgia teacher and “historian general” of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In 1915, she delivered a UDC address in San Francisco titled “The Historical Sins of Omission and Commission” that urged the organization to become a textbook watchdog. In 1920, she published a pamphlet, A Measuring Rod to Test Textbooks and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries. The publication warned against books that failed to assert that states rights and not slavery were the cause of secession, that referred to Confederate soldiers as traitors, that denigrated slaveholders, that described the war as a rebellion, or that celebrated Abraham Lincoln and denigrated Jefferson Davis. Elements of the Lost Cause narrative continued to be represented in American popular culture and in educational materials well into the next century (Thompson 2013a, 2013b; Greenlee 2019; Coleman 2017). Indeed, by 1940 the Lost Cause narrative dominated textbooks throughout the U.S. (Ford 2017).

If educational materials have been an important means of buttressing the Lost Cause mythology, museums have created an additional means of narrating Lost Cause through the selection and arrangement of display objects and presentations that thematize and interpret their meaning (Luke 2002). Memorial museums are scattered around the nation, although predominantly in former Confederate states: South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum (South Carolina), Corydon’s Civil War Museum (Indiana), Confederate Memorial Hall Museum (Louisiana), General Longstreet Headquarters Museum (Tennessee), Confederate Memorial Museum (Texas). Virginia has been a center of museum commemoration: Lee Chapel Museum (Washington and Lee University), VMI Museum (Virginia Military Institute), Old Court House Civil War Museum (Winchester), Warren Rifles Confederate Museum (Front Royal) (Wilson 2009).

The foremost museum, of course, has been the Richmond museum that originated as the Confederate Museum, later became the Museum of the Confederacy, and ultimately the American Civil War Museum. (Coski 2021; Davenport 2019). As Davenport reports, the early museum initially was closely linked to Lost Cause:

Opened as the Confederate Museum in 1896, what later became the Museum of the Confederacy emerged directly from the Lost Cause propaganda machine, which itself had largely been steered from Richmond. Lost Cause organizations, like the all-female Confederate Memorial Literary Society, which funded and operated the Confederate Museum, campaigned to shift public opinion to a more sympathetic, pro-Confederate understanding of the South’s “true” reasons for fighting the Civil War.

The museum was located in the former Confederate White House. As Coski (2021) described the museum:

The museum assigned rooms to each of the eleven Confederate states, along with Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland; the center parlor of the house was designated the “Solid South Room” and displayed the Great Seal of the Confederate States of America and other artworks and artifacts deemed important to the entire Confederacy.

The museum subsequently underwent a rather dramatic transformation (See, Issues/Challenges).

A variety of other forms of memorialization were also developed that promoted Lost Cause mythology. After the war ended, special cemeteries were created for the fallen (Confederated Southern Memorial Association), veterans of the war organized voluntary associations (Confederate Veterans, United Sons of Confederate Veterans). Veterans groups sponsored educational activities and participated in memorial activities and battlefield re-enactments. Most Confederate military personnel were granted amnesty following the war. Confederate generals were among them. By 1917, U.S. Army policy stipulated that southern military bases could be named for Confederate officers. Nine U.S. army bases ultimately were so named.

Confederate cemeteries were one means of creating sacred space for fallen soldiers (Confederated Southern Memorial Association). Women’s groups, such as the Daughters of the Confederacy, which was headquartered in Richmond, became a major organizer of commemorative groups (Janney 2008; Cox 2003). For example, Mary Dunbar Williams of Winchester, Virginia was particularly active in this mission and went on to lead cemetery memorialization campaigns across southern states. New publications (Southern Historical Society Papers, The Confederate Veteran) were established. Confederate veterans formed post-war associations (United Confederate Veterans, United Sons of Confederate Veterans). Soldiers’ aid organizations transformed into commemorative groups. Confederate cemeteries and memorial days for fallen soldiers were created (Confederated Southern Memorial Association). Confederate veterans held meetings, participated in dedication of monuments, and organized battle re-enactments.

Lost Cause was even thematized sporting events (Howard 2017). Gudmestad (1998) observes that in Richmond:

In many ways, the Richmond Virginia baseball team became representative of the city during the first half of the 1880s. Because many of the men who formed the Virginia Base-Ball Association had fought in the Civil War, the club served as a tangible link to the conflict, not yet two decades distant. Baseball in the former capital of the Confederacy fit neatly with romantic conceptions of war that began to emerge with the mythology of the Lost Cause. Those who directed the club used the game to promote the veneration of the Confederacy, while the team itself became a visible reminder of the recent struggle.

Later, the Blue-Gray football classic matched college seniors from former Confederate states against northern states. It was established in 1939 and was played annually through 2001, with a few minor exceptions. It was not desegregated until 1963.

Richmond, Virginia was a center of organization and activity for many of the Lost Cause movement groups. The White House of the Confederacy, Museum of the Confederacy, Confederate Memorial Chapel, headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, St. Paul’s Episcopal Church (the Cathedral of the Confederacy) and Hollywood Cemetery were among the organizations located there. There is a KKK klavern just outside of Richmond in Powhatan County.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The Lost Cause movement grew and became highly influential in establishing some components of its mission over the century following the end of the Civil War. Two of the movement’s most successful initiatives were memorialization and education. These were public matters as memorial monuments often were placed in public spaces and Lost Cause was included in textbooks used in public schools. The movement began experiencing setbacks more frequently after 2000 and major reversals after 2010. The pace increased of the removal of Confederacy-themed interior décor and renaming of public and private buildings, public streets, statues and monuments on public and private land, and public libraries (Anderson and Svrluga 2021). Because Virginia, and Richmond in particular, was a center of Lost Cause organization and activity, the growing opposition to Lost Cause was particularly visible there.

The most significant museum promoting the Lost Cause was The Confederate Museum. The museum changed its name to the Museum of the Confederacy in 1970 to adopt a more conventional museum  posture as it began to present a more “inclusive” set of exhibitions and added permanent exhibitions focused on the exploitation and abuses associated with slavery (Brundage 2005:298-99). An even more dramatic change occurred in 2013 when The American Civil War Museum [Image at right] was formed as the product of a merger between the American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. The American Civil War Center incorporated three sites: The White House of the Confederacy in Richmond, the American Civil War Museum at Historic Tredegar in Richmond, and the American Civil War Museum at Appomattox. The earlier Lost Cause orientation of the museum was criticized both by the new museum itself but also in articles published in the prestigious Smithsonian Museum’s periodical (Davenport 2019; Palmer and Wessler 2018). Other museums that challenge Lost Cause mythology had also been established in recent years, most notably The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. Established in 2018, the museum, along with its counterpart National Memorial for Peach and Justice, is devoted specifically an historical portrayal of lynching (McFadden 2019).

posture as it began to present a more “inclusive” set of exhibitions and added permanent exhibitions focused on the exploitation and abuses associated with slavery (Brundage 2005:298-99). An even more dramatic change occurred in 2013 when The American Civil War Museum [Image at right] was formed as the product of a merger between the American Civil War Center and the Museum of the Confederacy. The American Civil War Center incorporated three sites: The White House of the Confederacy in Richmond, the American Civil War Museum at Historic Tredegar in Richmond, and the American Civil War Museum at Appomattox. The earlier Lost Cause orientation of the museum was criticized both by the new museum itself but also in articles published in the prestigious Smithsonian Museum’s periodical (Davenport 2019; Palmer and Wessler 2018). Other museums that challenge Lost Cause mythology had also been established in recent years, most notably The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. Established in 2018, the museum, along with its counterpart National Memorial for Peach and Justice, is devoted specifically an historical portrayal of lynching (McFadden 2019).

The Confederate memorial on Stone Mountain in Georgia went into decline after being a major tourist site since its origin. The corporation operating the site for the State of Georgia ended its contract after suffering financial losses in 2017 and 2018, with continuing controversy being one of the reasons for their action. In 2017, the Ku Klux Klan applied for a permit to hold a gathering at the site but was denied. The at the time Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams made Stone Mountain a campaign issue, referring to the sculpture as a “blight upon our state (Fausset 2018). In 2020, over 100 protestors gathered at Stone Mountain to call for removal of the carving. A month later a white nationalist group attempted to organize a gathering, which led to the park being temporarily closed. The site subsequently received little interest from other potential management firms, and the future of the site remained opaque after 2022 (Fausset 2018; Shah 2018; King and Buchanan 2020).

The evolution of memorialization along Richmond, Virginia’s Monument Avenue is another instructive example of Lost Cause decline (One Monument Avenue 2022).

Monument Ave Looking back over the past 50 years, we can see even more clearly how the Lost Cause narrative began to unravel. By the end of the 1970s, changes to the racial profile of local and state governments, especially in the South, allowed African Americans to shape how their communities commemorated the past. New monuments rose up and key public sites were renamed. Historic places such as Colonial Williamsburg began to address some of the more challenging aspects of their pasts, such as slave auctions.

In 1965, the City Planning Commission in Richmond, Virginia issued a report in which it referred to the five existing monuments along Monument Avenue as “a bridge from the past into the present” and proposed the addition of seven more statues in various locations (Black and Varley 2003). The first significant change in the set of monuments along the avenue occurred in 1996 with the dedication of the Arthur Ashe monument. The situation had changed dramatically by 2010. In that year Virginia Governor Robert McDonnell issued a proclamation that the month of April would be Confederate History Month. There was backlash and McDonnell almost immediately withdrew the proclamation and announced that April would be celebrated as Civil War History Month.

The broader Confederate memorial removal movement gained momentum after 2010, particularly as a response to the deaths of African Americans at the hands of whites. In 2012, seventeen year-old African American Trayvon Martin was killed by George Zimmerman in Florida. Zimmerman was subsequently acquitted of criminal charges. In 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement emerged, with Trayvon  Martin’s death as a major impetus. Martin’s death was followed by the deaths of African Americans Eric Garner and Michael Brown Jr. in encounters with police the following year. 2015 was a flashpoint year as white teenager Dyllan Roof killed nine African-American parishioners during a Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Photographs later emerged of Roof, who was convicted of the crimes, carrying a Confederate flag. [Image at right]. The monument removal campaign gained further momentum in 2017 when a Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville motivated by the planned removal of the Robert E. Lee monument from a public park turned violent, killing one and injuring nineteen. All of the monuments, except the Lee memorial, along Richmond’s Monument Avenue were removed in 2020. Two additional, significant successes in removal campaign in Virginia were the removal of the Robert

Martin’s death as a major impetus. Martin’s death was followed by the deaths of African Americans Eric Garner and Michael Brown Jr. in encounters with police the following year. 2015 was a flashpoint year as white teenager Dyllan Roof killed nine African-American parishioners during a Bible study at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Photographs later emerged of Roof, who was convicted of the crimes, carrying a Confederate flag. [Image at right]. The monument removal campaign gained further momentum in 2017 when a Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville motivated by the planned removal of the Robert E. Lee monument from a public park turned violent, killing one and injuring nineteen. All of the monuments, except the Lee memorial, along Richmond’s Monument Avenue were removed in 2020. Two additional, significant successes in removal campaign in Virginia were the removal of the Robert  E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia in July 2021 and a similar removal in Richmond, Virginia [Image at right] in December of that year.

E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia in July 2021 and a similar removal in Richmond, Virginia [Image at right] in December of that year.

The movement to eliminate the display of Confederate symbols accelerated in 2020 following the murder of forty six year-old George Floyd by white police officer Derek Chauvin. Over 160 Confederate Symbols of all kinds were removed, renamed or relocated in 2020, following the murder of George Floyd that year. Virginia removed the largest number, followed by North Carolina, Texas, and Alabama. The total number of removals was greater than the four previous years combined. The U.S. military has recommended the renaming of eight military bases currently honoring Confederate military leaders by 2023. The replacement names would be more contemporary and diverse than the earlier names (Martinez and Khan 2022). The remarkable pace of memorialization removal notwithstanding, many Confederate symbols remain in place and a number of states have taken steps to protect them against local removal actions (McGreevy 2021; Anderson and Svrluga 2021; Kennicott 2022). Eight busts of Confederate leaders, with two busts being selected by each state, remain in place in the U.S. Capitol.

A number of religious denominations have responded to their own histories of direct support for Lost Cause mythology or their implication in slavery. The Episcopal Church has been the most highly visible in this campaign as it established the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, which was popularly referred to as the “Cathedral of the Confederacy.” In 2006, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church issued a resolution requesting that denominational churches, which are predominantly white, undertake studies of how they benefited from the practice of slavery. The Episcopal Church followed this up in 2018 with a three-year audit of church leadership. In part the audit proposal stated that

the church’s leadership, like its membership, is overwhelmingly white, and it found that white leaders and leaders of and leaders of color tend to perceive discrimination differently. People of color said they have often felt marginalized – despite the church’s professed commitment to racial reconciliation. White Episcopalians, on the other hand, frequently weren’t aware of how race has shaped their lives and their church (Paulsen 2021).

Predominantly white denominations in several states followed suit, including the Presbyterian Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Both passed resolutions (in 2004 and 2019, respectively) to study the denominations’ role in slavery and have begun the process of determining how to make reparations.

Among Protestant denominations, the Episcopal Church has had the highest profile on what the church termed “reconciliation” efforts. In 2006, the General Convention requested that local dioceses study how they profited from slavery, and dioceses in several states responded. The Church followed up in 2018 with a three-year audit of church leadership. In part the audit proposal stated that

the church’s leadership, like its membership, is overwhelmingly white, and it found that white leaders and leaders of and leaders of color tend to perceive discrimination differently. People of color said they have often felt marginalized – despite the church’s professed commitment to racial reconciliation. White Episcopalians, on the other hand, frequently weren’t aware of how race has shaped their lives and their church (Paulsen 2021).

Three years later the Episcopal Church’s Presiding Bishop, Michael Curry, announced a “churchwide racial truth and reconciliation effort,” noting that “Many congregations and schools and seminaries have done this – not all, but many have (Millard 2021). He went on to state that

The proposal will include ways to “tell the truth about our collective racial and ethnic history and present realities, to reckon with our church’s historic and current complicity with racial injustice, make commitments to right old wrongs and repair breaches and discern a vision for healing and reconciliation,” Curry said. To do that, the group will conduct a review of past and present truth and reconciliation processes within The Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion and in the countries where those churches are present, such as South Africa, Rwanda and New Zealand.

In the state of New York, the Episcopal Bishop, Andrew M.L. Dietsche, addressed the clergy in 2019 and stated that “The Diocese of New York played a significant, and genuinely evil, part in American slavery,” …. “We must make, where we can, repair.” In the address he reminded the audience that churches had owned slaves and that abolitionist Sojourner Truth had been a slave in the diocese. Following his address, a reparations fund was established for the “Year of Reparation” (Moscufo 2022).

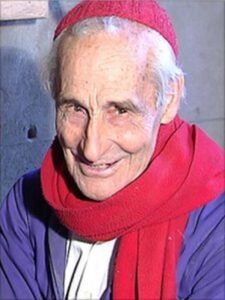

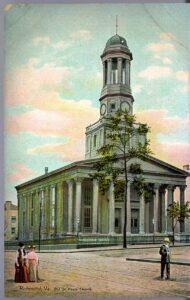

A most instructive case of confronting Lost Cause was St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, [Image at right] as it had been popularly known as the Cathedral of the Confederacy and openly supported Lost Cause during and following the Civil War. St. Paul’s continued to exhibit various forms of Confederate memorialization in its sanctuary but, as Richmond changed demographically and the church congregation changed, the church had already become a progressive Episcopal church by the mid-2010s. The church sponsored a variety of projects, including funding for public health, educational, and fair housing projects (St. Paul’s n.d.).

The watershed moment for the denomination as a whole and for St. Paul’s specifically came in 2015 in the wake of the murder by white nationalist Dylann Roof of nine African-American parishioners during a Bible study at A.M.E Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In that year the Washington National Cathedral, which is Episcopal, announced that it was removing two Confederate battle flags from windows honoring Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson. St. Paul’s removed battle flags and Confederate embroidered kneels; it also retired its coat of arms.

St. Paul’s Church announced the History and Reconciliation Initiative in 2015 following the Dylann Roof murders (St. Paul’s n.d.):

We are part of a living and evolving history. Our story began in 1844 as the United States’ economic and political structures fully embraced racial slavery. The resources that made this church possible came directly from the profits of factories and businesses, built on the backs of enslaved African American people. During those years, many white Protestants sought to justify slavery as God’s plan. St. Paul’s members also supported, along with most proslavery Protestants, a theology that insisted that God ordained racial inequality and that, as white people, they had a responsibility to govern black people. St. Paul’s became inextricably entwined with the Confederacy during the American Civil War. It was the home church to Confederate officials and officers and the scene of dramatic events at the end of the conflict. In the aftermath of the Civil War, St. Paul’s officially recognized its connections to Robert E. Lee, who worshipped here, and Jefferson Davis, who was baptized as a member of the parish, by marking their pews and installing windows in their honor.

The church began removing Confederate memorials in 2015. Underscoring the complexity of fully reversing its history with regard to race, the Truth and Reconciliation Initiative took five years to reach a point of an initial milestone and a plan for future continuation of the project, with the presentation of its project report, Blindspots.

While there has been a trend toward removal of Lost Cause perspectives on the Civil War in public school textbooks, the skirmish over content on that subject (as well as a number of others) has continued as decisions are typically made by state school boards (Thevnot 2015). In Texas, opposition to earlier renderings of history produced organized opposition, with the result that in 2018

…the Texas state school board decided that public school curricula should be changed to emphasize slavery as a primary cause of the Civil War, when it previously prioritized sectionalism and states rights; those changes are scheduled to go in effect this school year for middle and high school students (Greenlee 2019).

In Florida, by contrast, Governor Ron DeSantis developed a Civics Literacy Initiative that limited what content public schools can teach in the areas of race, gender identity, including Civil War history. For example, the destructive effects of slavery are modulated. The continuing tensions dividing the U.S. population is indicated in the governor’s portrayal (Ceballos and Brugal 2022):

They are trying to establish a religion of their own. This woke ideology functions as a religion, obviously it is not the Judeo-Christian tradition, but they want that to be effectively the governing faith of our country.

Nationally, at least thirty-sex states, including all of the secessionist states, have taken steps to limit teaching material related to race and racism. By contrast, only seventeen states have expanded teaching material in these areas (Leonard 2022).

The trend toward marginalization of Civil War era Lost Cause mythology and material representations notwithstanding, there are new forms of resistance that echo the same underlying cultural values (Schneider 2022). The states on either side of the most contentious social/political issues (gun ownership, abortion regulations, racism, electoral eligibility) in the U.S. often roughly coincide with the set of states that did and did not secede from the Union. For example, the strong and growing opposition to Critical Race Theory recalls the denial of a racist social structure in the Confederate states. The endorsement of Replacement Theory tracks to the same sense of displacement created by the freeing of slaves, the revocation of racial segregation statutes, and the increasing diversity of the American population. The debate over abortion has often been couched in terms of states rights as opposed to nationally protected individual rights of all citizens. While the Ku Klux Klan is no longer the imposing force that it once was, it was visible at the Charlottesville rally and at Stone Mountain and is a close relative of the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers. Stolen election claims resemble the Lost Cause claims of the war that was not lost. Confederate symbolism in public places may be diminished, but the Confederate flag was a visible presence at the U.S. Capitol insurrection. [Image at right] And Trumpism in its most generic form incorporates the kind of white nationalism that is compatible with Lost Cause. Since the forces on one side of this now great divide seek to re-establish a world that never was and the forces on the other side seek to build a global social order that remains emergent, it is likely that intense polarization of the kind witnessed during the Civil War will remain a persistent force in unfolding American history.

The debate over abortion has often been couched in terms of states rights as opposed to nationally protected individual rights of all citizens. While the Ku Klux Klan is no longer the imposing force that it once was, it was visible at the Charlottesville rally and at Stone Mountain and is a close relative of the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers. Stolen election claims resemble the Lost Cause claims of the war that was not lost. Confederate symbolism in public places may be diminished, but the Confederate flag was a visible presence at the U.S. Capitol insurrection. [Image at right] And Trumpism in its most generic form incorporates the kind of white nationalism that is compatible with Lost Cause. Since the forces on one side of this now great divide seek to re-establish a world that never was and the forces on the other side seek to build a global social order that remains emergent, it is likely that intense polarization of the kind witnessed during the Civil War will remain a persistent force in unfolding American history.

IMAGES

Image #1: Flag of the Confederate States of America.

Image #2: The burned over district in Richmond, Virginia following the 1865 fire.

Image #3: The Lost Cause authored by Edward Pollard in 1896.

Image #4: The carving of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Stonewall Jackson on Stone Mountain.

Image #5: Statue of Robert E. Lee on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia.

Image #6: Dyllan Roof holding a Confederate flag.

Image #7: St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.

Image #8: The removal of Robert E. Lee’s statue from its pinth on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia.

Image #9: An insurrectionist in the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021 carrying a Confederate flag.

REFERENCES

American Civil War Museum website. 2022. American Civil War Museum. Accessed from https://acwm.org/ on 20 June 2022.

American Historical Association. 2017. “AHA Statement on Confederate Monuments.” Accessed from https://www.historians.org/news-and-advocacy/aha-advocacy/aha-statement-on-confederate-monuments on 10 June 2022.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

Anderson, Nick and Susal Syrluga. 2021. “From slavery to Jim Crow to George Floyd: Virginia universities face a long racial reckoning.” Washington Post, November 26. Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/11/26/virginia-universities-slavery-race-reckoning/?utm_campaign=wp_local_headlines&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&wpisrc=nl_lclheads&carta-url=https%3A%2F%2Fs2.washingtonpost.com%2Fcar-ln-tr%2F356bfa2%2F61a8b7729d2fdab56bae50ef%2F597cb566ae7e8a6816f5e930%2F9%2F51%2F61a8b7729d2fdab56bae50ef on 4 December 2021.

Bill of Rights Institute. 2022. “Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching.” Accessed from https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/ida-b-wells-and-the-campaign-against-lynching on 5 July 2022.

Black, Brian and Bryn Varley. 2003. “Contesting the Sacred: Preservation and Meaning on Richmond’s Monument Avenue.” Pp. 234-50 in Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art and the Landscapes of Southern Memory, edited by Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

Bohland, Jon. 2006. A Lost Cause Found: Vestiges of Old South Memory in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Ph.D Dissertation: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. 2005. The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Breed, Allen. 2018. “‘The lost cause’: the women’s group fighting for Confederate monuments.” Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/aug/10/united-daughters-of-the-confederacy-statues-lawsuit on 18 November 2101.

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. 2005. The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Cameron, Chris. 2022. “How Army Bases in the South Were Named for Defeated Confederates.” New York Times, December 2. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/02/us/politics/army-base-names-south-confederates.html?login=email&auth=login-email on 12 December 2022.

Ceballos, Ana and Sommer Brugal. 2022. “Some teachers alarmed by Florida civics training approach on religion, slavery.”Tampa Bay Times, July 1. Accessed from https://www.tampabay.com/news/florida-politics/2022/06/28/some-teachers-alarmed-by-florida-civics-training-approach-on-religion-slavery/?utm_source=Pew+Research+Center&utm_campaign=23452861df-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_07_01_01_39&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_3e953b9b70-23452861df-399904145 on 2 July 2022.

Chilton, John. 2020. “St. Paul’s Richmond to rededicate Lee and Davis windows with new meaning.” Episcopal Café, July 12. Accessed from https://www.episcopalcafe.com/st-pauls-richmond-to-rededicate-lee-and-davis-windows-with-new-meaning/ on 1 November 2021.

Coleman, Arica. 2017. “The Civil War Never Stopped Being Fought in America’s Classrooms. Here’s Why That Matters.” Time, November 8. Accessed from https://time.com/5013943/john-kelly-civil-war-textbooks/ on 5 February 2022.

Coski, John. 2021. “Museum of the Confederacy. Encyclopedia Virginia. Accessed from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/museum-of-the-confederacy on 20 June 2022.

Coski, John. 1996. “A Century of Collecting,” The Museum of the Confederacy Journal #74.

Cox, Karen. 2003. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Davenport, Andrew. 2019. “A New Civil War Museum Speaks Truths in the Former Capital of the Confederacy.” Smithsonian Magazine, May 2. Accessed from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/civil-war-museum-speaks-truths-former-capital-of-confederacy-180972085/ on 20 June 2022.

Domby, Adam. 2020. The False Cause: Fraud, Fabrication, and White Supremacy in Confederate Memory. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Equal Justice Initiative. 2017. Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. Equal Justice Initiative. Accessed from https://eji.org/reports/lynching-in-america/ on 20 June 2022.

Fausset, Richard. 2018. “Stone Mountain: The Largest Confederate Monument Problem in the World.” The New York Times, Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/18/us/stone-mountain-confederate-removal.html on 2 July 2022.

Ford, Matt. 2017. “What Trump’s Generation Learned About the Civil War. The Atlantic, August 28. Accessed from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/08/what-donald-trump-learned-about-the-civil-war/537705/ on 5 February 2022.

Greenlee, Cynthia. 2019. “How history textbooks reflect America’s refusal to reckon with slavery.” Vox, August 26. Accessed from https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/8/26/20829771/slavery-textbooks-history on 5 February 2022.Griggs, Walter. 2017. Historic Richmond Churches & Synagogues. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Gudmestad, Robert. 1998. “Baseball, the lost cause, and the new South in Richmond, Virginia, 1883-1890.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography; Richmond 106:267-300.

Hillyer, Reiko. 2007. Designing Dixie: Landscape, Tourism, and Memory in the New South, 1870-1917. Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University.

Hobsbawm, Eric and Terence Ranger, eds. 1983. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holpuch, Amanda and Mona Chalabi. “Changing history’? No – 32 Confederate monuments dedicated in past 17 years.” The Guardian, August 16. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/aug/16/confederate-monuments-civil-war-history-trump on 20 June 2022.

Howard, Josh. 2017. “Baseball as Political Theater in the Virginias.” Accessed from https://ussporthistory.com/2017/10/12/baseball-as-political-theater-in-the-virginias/ on 30 December 2021.

Irons, Charles. 2020. “Religion during the Civil War.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Accessed from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/religion-during-the-civil-war/ on 18 November 2021.

Irons, Charles. 2008. The Origins of Proslavery Christianity: White and Black Evangelicals in Colonial and Antebellum Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Janney, Caroline. “The Lost Cause. 2021. Encyclopedia of Virginia. Accessed from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lost-cause-the on 9 November 2021.

Janney, Caroline E. 2008. Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Kennicott, Phillip. 2022. “Richmond took down its Confederate statues. But not all of them are gone.” Washington Post, July 19. Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/07/23/richmond-confederate-statues-stonewall-hill/ on 24 July 2022.

King, Michael and Christopher Buchanan. 2020. “‘I’m in your house’ | Armed group condemns systemic and overt racism, marches to Stone Mountain.” 11 Alive, July 4. Accessed from https://www.11alive.com/article/news/local/stone-mountain/group-of-demonstrators-enter-stone-mountain-park/85-2ea0c153-8a88-46bd-bca7-faf19ec2c8ba on 2 July 2022.

Kinnard, Meg. 2017. “Episcopalians struggle with history of Confederate symbols.” Associated Press, September 18. Accessed from https://gettvsearch.org/lp/prd-best-bm-msff?source=google display&id_encode=187133PWdvb2dsZS1kaXNwbGF5&rid=15630&c=10814666875&placement=www.whsv.com&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIl6eUipjp8wIVVcLhCh3mbgFkEAEYASAAEgIG4vD_BwE on 26 October 2021.

Leonard, Bill. 2022. “‘The Religion of the Lost Cause’ is back, and it may be winning.” Baptist News, May 13. Accessed from https://baptistnews.com/article/the-religion-of-the-lost-cause-is-back-and-it-may-be-winning/#.YsHo1OzMIQY on 3 July 2022.

Levin, Kevin. 2020. “Richmond’s Confederate Monuments Were Used to Sell a Segregated Neighborhood. The Atlantic, June 11. Accessed from the https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/its-not-just-the-monuments/612940/ on 20 June 2022.

Levin, Kevin. 2019. Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. Chapel Hil: University of North Carolina Press.Levin, Kevin. 2011. “Not Your Grandfather’s Civil War

Commemoration The Atlantic, December 13. Accessed from https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/12/not-your-grandfathers-civil-war-commemoration/249920/ on 20 June 2022.

Lowery, Malinda Maynor. 2021. “The Original Southerners: American Indians, the Civil War, and Confederate Memory.” Accessed from https://www.southerncultures.org/article/the-original-southerners/ on 5 February 2022.

Martinez, Luis and Mariam Chan. 2022. “Fort Bragg to be renamed Fort Liberty among Army bases losing Confederate names: Exclusive. ABC News, May 24. Accessed from https://nwnewsradio.com/abc-news/abc-national/fort-bragg-to-be-renamed-fort-liberty-among-army-bases-losing-confederate-names-exclusive/ on 2 July 2022.

McFadden, Jane. 2019. “Equal Justice Initiative National Memorial for Peace and Justice.’” Journal of American History 106:703-708.

McPherson, James. 2004. “Long-Legged Yankee Lies: The Southern Textbook Crusade.” Pp. 64-78 in The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture, edited by Alice Fahs and Joan Waugh. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

McGreevy, Nora. 2021. “The U.S. Removed Over 160 Confederate Symbols in 2020—but Hundreds Remain.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 25. Accessed from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/us-removed-over-160-confederate-symbols-2020-more-700-remain-180977096/

Moscufo, Michaela. 2022. “Churches played an active role in slavery and segregation. Some want to make amends.” NBC News, April 3. Accessed from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/churches-played-active-role-slavery-segregation-want-make-amends-rcna21291?utm_source=Pew+Research+Center&utm_campaign=8092da544f-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2022_04_04_01_47&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_3e953b9b70-8092da544f-399904145

On Monument Avenue website. n.d. One Monument Avenue. Accessed from https://onmonumentave.com/ on 20 June 2022.

Palmer, Brian and Seth Freed Wessler. 2018. “The Costs of the Confederacy.” Smithsonian Magazine, December. Accessed from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/costs-confederacy-special-report-18 on 2 July 2022.

Paradis, Michel. 2020. “The Lost Cause’s Long Legacy.” The Atlantic, June. Accessed from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/the-lost-causes-long-legacy/613288/0970731/ on 9 June 2022.

Paulsen, David. 2021. “Episcopal Church releases racial audit of leadership, citing nine patterns of racism in church culture.” Episcopal New Service, April19. Accessed from https://www.episcopalnewsservice.org/2021/04/19/episcopal-church-releases-racial-audit-of-leadership-citing-nine-patterns-of-racism-in-church-culture/ on 4 December 2021.

Pennyfarthing, Aldous. 2023. “Mississippi’s GOP governor signs Confederate Heritage Month proclamation and dates it … April 31.” Daily Kos, April 5. Accessed from https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2023/4/5/2162217/-Mississippi-s-GOP-governor-signs-Confederate-Heritage-Month-proclamation-and-dates-it-April-31 on 7 April 2023.

Rawls, Margaret. 2017. The Nature and Life of Contested History and Memorials: The Story of Charlottesville. Charlottesville: University of Virginia.

Rutherford, Milfred. 2018 [1920]. A Measuring Rod to Test Text Books, and Reference Books in Schools, Colleges and Libraries. London: Forgotten Books.

Rutherford, Milfred. 1915. “Historical Sins of Omission and Commission.” United Daughters of the Confederacy Address, October 22. San Francisco: United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Sampson, Zinie. 2007. “Virginia marks 200th birthday of Robert E. Lee: NAACP questions use of state money, class lessons about Lee.” Star News Online. Accessed from https://www.starnewsonline.com/story/news/2007/01/19/virginia-marks-200th-birthday-of-robert-e-lee/30289973007/ on 10 June 2022.

Schneider, Gregory. 2022. “Virginia county poised to take unusual step to preserve Confederate statue.” Washington Post, December 2. Accessed from https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/12/02/mathews-county-virginia-confederate-statue-vote/ on 2 December 2022.

Shah, Khushbu. 2018. “The KKK’s Mount Rushmore: the problem with Stone Mountain.” The Guardian, October 24. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/cities/ng-interactive/2018/oct/24/stone-mountain-is-it-time-to-remove-americas-biggest-confederate-memorial on 2 July 2022.

Slipek, Edwin. 2011. “After the Fire.” Style Weekly, May 10. Accessed from https://m.styleweekly.com/richmond/after-the-fire/Content?oid=1477651 on 26 October 2021.

Stout, Harry. 2021. “Religion in the Civil War: The Southern Perspective.” Accessed from

http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/cwsouth.htm on 18 November

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. n.d. “History and Reconciliation Initiative.” Accessed from https://www.stpaulsrva.org/HRI on 27 October 20Thevnot, Brian. 2015). “Hijacking History.” Texas Tribune, January 12. Accessed from https://www.texastribune.org/2010/01/12/sboe-conservatives-rewrite-american-history-books/ on 20 June 2022.

Taylor, Alan. 2021. AMERICAN REPUBLICS: A Continental History of the United States, 1783-1850. New York: W. W. Norton & Company

Thompson, Tracy. 2013a. The New Mind of the South. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Thompson, Tracy. 2013b. “The South still lies about the Civil War.” Salon, March 16. Accessed from https://www.salon.com/2013/03/16/the_south_still_lies_about_the_civil_war/ on 30 December 2021.

Williams, David. 2017. “Lost Cause Religion.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. Accessed from https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/lost-cause-religion/ on 10 June 2022.

Wilson, Charles. 2009. Baptized in Blood: The Religion of the Lost Cause, 1865-1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Wolfe, Brendan. 2021. “Lynching in Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Accessed from https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lynching-in-virginia/ on 20 June 2022.

Publication Date:

7 July 2022

incorporating these into John Frum ideology and liturgy. These included shrines decorated with red painted soldiers, airplanes, crosses (from military ambulances), and symbolic dog tags, as well as American flags, military uniforms, radio antennae, and drill teams that march with rifles made of lengths of bamboos. [Image at right] Team members paint USA on their bare chests. In addition to the annual February 15 celebration, Sulphur Bay leaders also declared Friday to be John Frum’s sabbath. Every Friday “teams” of supporters from villages across Tanna have walked down to the Bay to sing John Frum hymns and to dance through the night, although Friday sabbath participation declined, in 2000, when the Sulphur Bay organization split into three factions.

incorporating these into John Frum ideology and liturgy. These included shrines decorated with red painted soldiers, airplanes, crosses (from military ambulances), and symbolic dog tags, as well as American flags, military uniforms, radio antennae, and drill teams that march with rifles made of lengths of bamboos. [Image at right] Team members paint USA on their bare chests. In addition to the annual February 15 celebration, Sulphur Bay leaders also declared Friday to be John Frum’s sabbath. Every Friday “teams” of supporters from villages across Tanna have walked down to the Bay to sing John Frum hymns and to dance through the night, although Friday sabbath participation declined, in 2000, when the Sulphur Bay organization split into three factions.

Quimby (1802–1866), Emmet Fox (1886–1951), Ernest Holmes (1887–1960), Napoleon Hill (1883–1970), Norman Vincent Peale (1898–1993), and Catherine Ponder (b.1927) as further inspirations (Virtue 1996:xiii; 1997a:xiii; 1997b: xvi). Elsewhere, she recalled listening to taped lectures by Elizabeth Clare Prophet (1939–2009) of the

Quimby (1802–1866), Emmet Fox (1886–1951), Ernest Holmes (1887–1960), Napoleon Hill (1883–1970), Norman Vincent Peale (1898–1993), and Catherine Ponder (b.1927) as further inspirations (Virtue 1996:xiii; 1997a:xiii; 1997b: xvi). Elsewhere, she recalled listening to taped lectures by Elizabeth Clare Prophet (1939–2009) of the  her writing into a more overtly supernaturalist and New Age direction. In 1997, Hay House published Virtue’s first book about angels, Angel Therapy : Healing Messages for Every Area of Your Life, in which she outlined a form of psychological healing reliant on angelic communication. [Image at right] In her foreword, she relayed how she had felt angelic presences near her as a child but had only begun “listening to angels” after they warned her about an attempted carjacking she experienced in an Anaheim parking lot in July 1995 (Virtue 1997b:viii–ix). This incident exerted a sufficient impact on her that she referred to it repeatedly in later publications (Virtue 1997a:153–54; 2001:15; 2003b:5; 2008:23, 35). Angel Therapy included material presented as having been directly channeled from the angels through a process of automatic writing: “I would lose consciousness of my body while The Angelic Realm transcribed through my mind and hands directly onto the keyboard of my computer” (Virtue 1997b:x).

her writing into a more overtly supernaturalist and New Age direction. In 1997, Hay House published Virtue’s first book about angels, Angel Therapy : Healing Messages for Every Area of Your Life, in which she outlined a form of psychological healing reliant on angelic communication. [Image at right] In her foreword, she relayed how she had felt angelic presences near her as a child but had only begun “listening to angels” after they warned her about an attempted carjacking she experienced in an Anaheim parking lot in July 1995 (Virtue 1997b:viii–ix). This incident exerted a sufficient impact on her that she referred to it repeatedly in later publications (Virtue 1997a:153–54; 2001:15; 2003b:5; 2008:23, 35). Angel Therapy included material presented as having been directly channeled from the angels through a process of automatic writing: “I would lose consciousness of my body while The Angelic Realm transcribed through my mind and hands directly onto the keyboard of my computer” (Virtue 1997b:x). which people could engage in cartomancy, a form of divination. (Image at right) All were published by Hay House. Her output was prolific and she eventually became, she observed, “the bestselling New Age author at the top New Age publishing house” (Virtue 2020:29).

which people could engage in cartomancy, a form of divination. (Image at right) All were published by Hay House. Her output was prolific and she eventually became, she observed, “the bestselling New Age author at the top New Age publishing house” (Virtue 2020:29). ase of a takeover by an authoritarian government (Virtue 2020:76).

ase of a takeover by an authoritarian government (Virtue 2020:76). 2020:98, 103). She later related that on that day she “surrendered my life to Jesus as my Lord and Savior” (Virtue 2020:xii), and was baptized in the sea near Kawaihae Harbor the following month [Image at right] (Virtue 2020:122; Aldrich 2017). However, within a few years she concluded that, while her conversion was legitimate, the vision had in fact been a demon masquerading as Christ to lead her astray (Virtue 2020b; FAQ 2021).

2020:98, 103). She later related that on that day she “surrendered my life to Jesus as my Lord and Savior” (Virtue 2020:xii), and was baptized in the sea near Kawaihae Harbor the following month [Image at right] (Virtue 2020:122; Aldrich 2017). However, within a few years she concluded that, while her conversion was legitimate, the vision had in fact been a demon masquerading as Christ to lead her astray (Virtue 2020b; FAQ 2021).

Gotaishi Mountain of the Fukui Prefecture in May of 2003, the caravan would first pass through the Ōsaka, Kyoto, Fukui, Gifu, Nagano, and Yamanashi prefectures. [Image at right]

Gotaishi Mountain of the Fukui Prefecture in May of 2003, the caravan would first pass through the Ōsaka, Kyoto, Fukui, Gifu, Nagano, and Yamanashi prefectures. [Image at right] attacks, the Pana-Wave Laboratory members began to gown themselves from head to toe in white uniforms. [Image at right] According to one member, Pana-Wave Laboratory members wore “white clothes made of 100 % cotton in order to protect [themselves] from artificial scalar waves that the extremists were firing into the Pana-Wave Research Center” (E-mail from Pana-Wave Laboratory member, July 2004). The actual Pana-Wave Laboratory uniform consisted of a white lab coat, a strip of white cloth used as a headpiece, a white mask and white rubber boots. Similar white coverings wrapped other material accessories such as eyewear and watches.

attacks, the Pana-Wave Laboratory members began to gown themselves from head to toe in white uniforms. [Image at right] According to one member, Pana-Wave Laboratory members wore “white clothes made of 100 % cotton in order to protect [themselves] from artificial scalar waves that the extremists were firing into the Pana-Wave Research Center” (E-mail from Pana-Wave Laboratory member, July 2004). The actual Pana-Wave Laboratory uniform consisted of a white lab coat, a strip of white cloth used as a headpiece, a white mask and white rubber boots. Similar white coverings wrapped other material accessories such as eyewear and watches. data from electromagnetic waves, monitoring solar activity, running medical tests on Chino, and composing rough drafts for Love Righteous, a journal that they produced and sold back to members. [Image at right] In the view of the Pana-Wave Laboratory, “any authentic religion always has a scientific base” and the combination of these often-contradictory enterprises functioned in tandem (E-mail from Pana-Wave Laboratory member, July 2004).

data from electromagnetic waves, monitoring solar activity, running medical tests on Chino, and composing rough drafts for Love Righteous, a journal that they produced and sold back to members. [Image at right] In the view of the Pana-Wave Laboratory, “any authentic religion always has a scientific base” and the combination of these often-contradictory enterprises functioned in tandem (E-mail from Pana-Wave Laboratory member, July 2004). Laboratory believed that somehow the former USSR used this Tesla Coil to produce electromagnetic wave weaponry. [Image at right] According to Chino, this Tesla Coil was also distributed to the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) as a tool to conduct brainwashing programs in Japan. The Pana-Wave Laboratory contended that a surplus of electrical power cable attached to electrical poles were actually electromagnetic scalar wave generators in disguise. Indeed, these wound-up cables attached to electrical power lines roughly resemble the spiral formation of the Tesla Coil.

Laboratory believed that somehow the former USSR used this Tesla Coil to produce electromagnetic wave weaponry. [Image at right] According to Chino, this Tesla Coil was also distributed to the Japanese Communist Party (JCP) as a tool to conduct brainwashing programs in Japan. The Pana-Wave Laboratory contended that a surplus of electrical power cable attached to electrical poles were actually electromagnetic scalar wave generators in disguise. Indeed, these wound-up cables attached to electrical power lines roughly resemble the spiral formation of the Tesla Coil. Wave Laboratory’s version of this mechanism was the Scalar Wave Deflector Coil (SWDC). [Image at right] These SWDCs were placed all over the laboratory and could be found strategically covering certain portions of Pana-Wave Laboratory members’ bodies.

Wave Laboratory’s version of this mechanism was the Scalar Wave Deflector Coil (SWDC). [Image at right] These SWDCs were placed all over the laboratory and could be found strategically covering certain portions of Pana-Wave Laboratory members’ bodies. A similar mechanism that was used by the Pana-Wave Laboratory was produced through reasoning that scalar waves could be captured and then redirected toward a panel that neutralizes the effects of the radiation. This mechanism was referred [Image at right] to as the Direction Specific Wave Diffuser (DSWD). SWDC and DSWD were artificial security mechanisms; however, Pana-Wave Laboratory also believed that nature could act as a defense against electromagnetic waves. One such natural defense mechanism was the physical structure of trees. According to Pana-Wave Laboratory members, the trunk portion of trees actually acted as a repository for scalar waves. Similar to the DSWD, the trunk of a tree first captures scalar waves, then discharges them into the air