SANTA MUERTE TIMELINE

850: Zapotecs built Lyobaa, City of the Dead, later called Mitla (the Aztec appellation for it as it they saw it as linked to Mictlan, their name for the underworld). This was the most important religious center for the Zapotec where they worshiped their primary deities, two death deities, consisting of a couple who were sacrificed to and propitiated for healing. This was also where they honored their deceased ancestors.

1019: Beneath the city of Chichen Itza, the Mayans built a series of cave chambers that represent Xibalba, the underworld. They held rituals to death deities such as Cizen, Ah Puch, among others.

1375: Aztecs established their capital at Tenochtitlan (the site of modern Mexico City). Their empire dominates central Mexico culturally and politically until 1519. The Aztec belief system included Mictecacihuatl, the Aztec goddess of death traditionally represented as a human skeleton or carnal body with a skull for a head.

1519-1521: The Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, Zapotecs, Mayans and other groups who worshipped death deities such as the Mixtec took place, driving traditional Indigenous beliefs and devotions underground as the colonial era commenced. The Spanish brought in the figure of the Grim Reaper who was interpreted by some Indigenous groups to be a death deity and locals began to worship the figure.

1700’s: Spanish Inquisition documents recorded that clergy castigated locals for worship of figures of the Grim Reaper and for conducting rituals in her honor, in some cases this figure was documented as being called “Santa Muerte.” The practice remained occult as those who practiced such worship were accused of heresy and punished; the deathly figures were destroyed by the clergy.

1860s: On the northern frontier of what had been until recently the Viceroy of New Spain, in New Mexico and southern Colorado, a group of mestizo Penitentes were discovered worshiping death. The figure was venerated and referred to interchangeably as Santa Muerte and Comadre (co-godmother) Sebastiana.

1870s-1900: There was virtually no mention of Santa Muerte in the traditional written historical record.

1940’s: Santa Muerte reappeared in ethnographies penned by Mexican and North American anthropologists, primarily as a folk saint being appealed to by women seeking the saint’s help to bring back errant husbands and boyfriends.

2001: On All Saints Day, Enriqueta Romero Romero placed her Santa Muerte statue outside the shop where she sold quesadillas. She thereby established the first public shrine dedicated to the devotion of death in the downtown Mexico City neighborhood of Tepito.

2003: Self-declared “Archbishop” David Romo’s temple, the Traditional Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, Mex-USA was granted official recognition by the Mexican government. On August 15, the feast day of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, the church celebrated the inclusion of Santa Muerte in its set of beliefs and practices.

2003: The Santuario Universal de Santa Muerte (Universal Sanctuary of Santa Muerte) was founded by “Professor” Santiago Guadalupe, a Mexican immigrant from the state of Veracruz, in Los Angeles.

2004: One of Romo’s disgruntled priests filed a formal complaint over the church’s inclusion of the Santa Muerte in its devotional paradigm.

2005: The Mexican government stripped the Traditional Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, Mex-USA of its official recognition. However, Mexican law did not require such sanctions, and the incident provoked political controversy.

2008: After the death of her son, Jonathan Legaria Vargas, who had erected the largest effigy of Santa Muerte in Tultitlán Mexico City, his mother Enriqueta Vargas established the largest Santa Muerte network of transnational churches to honor Santa Muerte.

2009: A growing number of people, in particular women, started establishing shrines to Santa Muerte across Mexico.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Santa Muerte’s name reveals much about her identity. La Muerte means death in Spanish and is a feminine noun (denoted by the feminine article “la”) as it is in all Romance languages. “Santa” is the feminine version of “santo,” which can be translated as “saint” or “holy,” depending on the usage. Santa Muerte is a folk saint, that is to say a saint of the folk, who is not recognized by the Catholic Church. Unlike official saints, who have been canonized by the Catholic Church, folk saints are spirits of the dead. [Image at right] They are considered holy for their miracle working powers by the local populace, to whom they are linked by locality and culture. Generally, they are local people who died tragic deaths and who thereafter were believed to listen to prayers and answer them with miracles. In Mexico and Latin America in general, folk saints command widespread devotion and are often more popular than the official saints. Where Santa Muerte differs from other folk saints is that for most devotees, she is the personification of death itself and not of a deceased human being.

The folk saint was created by the folk from an admixture of Indigenous death deities and the Grim Reaper during the colonial era when the Spanish introduced Catholicism. The most common version of the story of the saint’s indigenous identity in Northern Mexico gives her Aztec origins but others give her Purépecha, Mayan or even Zapotec origins. For those in Northern Mexico, Santa Muerte is thought to have originated as Mictecacihuatl, the Aztec goddess of death who, along with her husband Mictlantecuhtli, ruled over the underworld, Mictlan. Like Santa Muerte, the deathly couple was traditionally represented as human skeletons or carnal bodies with skulls for heads. Aztecs believed that those who died of natural causes ended up in Mictlan, and they also invoked the gods’ supernatural powers for earthly causes.

When Spanish clergy came as part of the colonial conquest of the “New World,” they brought with them the figures of Mary, Jesus, the saints and the Grim Reaper to teach catechism during their conversion mission. While for the Spanish the Grim Reaper was but a representation of death, Indigenous people, following on from their devotion to death deities, took the Grim Reaper as a saint of death to be venerated for favors just like other saints, and Jesus. Drawing on traditions of sacred ancestral bones, worship of death deities and interpreting Christianity through their own cultural lens, they took the church’s skeletal figure of death for a saint in its own right. She was worshiped covertly for hundreds of years in total secrecy, due to punishment by the Spanish when they discovered Indigenous worshipers supplicating Santa Muerte.

Spanish colonial documents from 1793 and 1797 housed in the archives of the Inquisition describe local devotion to Santa Muerte in the present-day Mexican states of Querétaro and Guanajuato. The inquisitorial documents describe separate cases of “Indian idolatry” revolving around skeletal figures of death petitioned by Indigenous citizens for political favors and justice. [Image at right] Neither Mexican nor foreign observers recorded her presence again until the 1940s.

The first written references to the skeleton saint in the twentieth century mention her in the context of acting as a supernatural love doctor summoned by a red candle. Saint Death of the crimson candle comes to the aid of women and girls who feel betrayed by the men in their lives. Three anthropologists, one Mexican and two American, mentioned her role as a love sorceress in their research conducted in the 1940s and 1950s.

From the 1790s until 2001, Santa Muerte was venerated clandestinely. Altars were kept in private homes, out of public sight, and medallions and scapulars of the skeleton saint were hidden underneath the shirts of devotees, unlike today when many proudly display them, along with T-shirts, tattoos, and even tennis shoes as badges of their belief.

The folk saint emerged publicly when Enriqueta Romero, a quesadilla-seller in Tepito, Mexico City placed her statue outside her modest home in 2001 in thanks to the folk saint for her son’s manumission from gaol. After this, devotion to death exploded, with many becoming devotees or declaring their faith publicly. Following in the footsteps of Romero, men and women began opening temples to the saint of death. Jonathan Legaria Vargas, aka Comandante Pantera, started a temple which was later expanded by his mother, Enriqueta Vargas, upon his death by gunfire. She established the largest transnational ministry to the skeleton saint in 2008, and many others followed suit, opening their own churches to the saint of death.

It is female leaders who have been at the forefront of this movement, given its focus on the female folk saint of death. Unlike the Catholic Church, which precludes women from accessing positions of power, Santa Muerte considers all equal before death, and that includes all genders. This has allowed women to emerge as prestigious and powerful spiritual leaders from Yuri Mendez in Cancun, who established the largest shrine in the city, and perhaps even in Quintana Roo. Over a decade ago Elena Martinez Perez established the largest shrine to the folk saint in the region of Oaxaca. A prayer to Santa Muerte for women, originally written by Yuri Mendez, reveals the importance of women not only in spreading devotion but also in the many needs they have, their desires, their fears and why they turn to the female folk saint of death who they believe will treat them as an equal.

Santa Muerte, I, your fervent servant, ask you for me and for all those women who work hard every day to bring sustenance to the home, that we do not lack prosperity, that the doors of success be opened, I also ask for those who are studying, help them to fulfill their objectives satisfactorily.

“Protect our path, remove all evil and danger that surrounded us.

Drive away any man who wants to harm us, bless our marriage or our courtship.

Ensure that love is not lacking in our lives.

Santa Muerte, whatever my problems are, I trust you and I know that you will not leave me alone and you will help me (here the devotee should make their request as per the problem that they are going through)

I am a woman, I am your devotee, and I will be until the last day of my life, my life is in your hands, and I will walk calmly because I know that you are with me and you will not leave me all alone.

Bless and protect my family, my friends, keep all falsehood and hypocrisy away from me.

I thank you, I know that you listen to me and that always will listen to whatever I have to say. Give me much wisdom and sufficient temperance to walk within this society.

And I ask for nothing but respect, because I am a woman and I have the same rights as anyone else.

You are fair, and you will not allow me to suffer any humiliation from anyone.

I am a woman, I am your devotee and I will be until the last day of my life, may my requests will be heard

Amen

Several notable men have also established churches, but these have been fleeting. For example, David Romo who established the Traditional Holy Catholic Apostolic Church, Mex-USA was arrested in 2011 on various charges, including kidnapping, and his Church abruptly closed. Jonathan Legaria Vargas, also known as “Comandante Pantera” (Commander Panther) and “Padrino (Godfather) Endoque,” was a charismatically outspoken leader in the growing public devotional tradition surrounding Santa Muerte. He had built a towering seventy-five-foot-tall effigy of Santa Muerte in Tultitlan on the gritty outskirts of Mexico City, and was on his way to becoming a centralizing figure in the loose knit community of Santa Muertistas. However, in 2008 he was gunned down in his car as assailants sprayed it with 150 bullets, killing him instantly. His mother, Enriqueta Vargas however, made Santa Muerte spread transnationally by opening churches in Colombia, Costa Rica and across Mexico.

Trans figures have also been drawn to the folk saint. Since death judges no one since death comes to us all, the saint has a large LGBTQ+ following. One such trans leader in New York is Arely Vasquez who opened a shrine to Santa Muerte in Queens about a decade ago.

Santa Muerte is prayed to by a motley crew of followers from businesswomen and men, to housewives and lawyers to politicians and nurses. She is known above all for her appeal to those living at the margins of society and close to death. Indeed, much of the Saint’s popularity comes from a context of heightened awareness of death in Mexico, given the tragic amount of violence, death and destruction caused by the ongoing drug war which has been raging across Mexico for many decades and is only escalating under the current president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, whose policy of “abrazos no balazos,” (“hugs not bullets”) has proved ineffectual and only worsened the lives of those who must face narcoviolence on their doorstep daily. Femicide is also a major issue in Mexico with ten women murdered daily and a woman is raped every twenty seconds. Such gendered violence is treated with impunity. In such an environment, many rather than fearing death have forged a relationship with a saint of death, whom they ask for life and for protection from the heinous violence on the streets on Mexico.

Santa Muerte provides miracles to devotees, granting them love, luck, health, wealth, protection, well-being and much more. Santa Muerte is the only female saint of death in the Americas. She is most often depicted as a female Grim Reaper outfitted with a scythe and wearing a shroud. [Image at right] Often, she holds a set of scales representing her ability to deliver justice to those in trouble with the law, or who require revenge. Santa Muerte sometimes holds a globe that symbolizes her global dominion over the world as death herself. She typically appears with an owl perched at her feet. In Western iconography, the owl symbolizes wisdom, and some Mexicans view this nocturnal bird similarly. However, the Mexican interpretation relates much more to death. Indigenous death deities, the underworld and night were often linked to owls in precolonial times. Owls and their linkage as a harbinger of death are encapsulated in the popular Mexican proverb: “When the owl screeches, the Indian dies.”

The Pope and many bishops have decried Santa Muerte as a narco-saint and those who follow her as heretical. Even the government has followed this tack, especially under Calderon, who destroyed thousands of shrines on the US-Mexico border in a futile attempt to expunge the drug trade. Sometimes exorcisms are even carried out by Catholic Clergy to expunge apostates of her spirit. However, most Santa Muertistas (followers of Santa Muerte) view devotion to the folk saint as complementary to their Catholic faith or even a part of it, despite condemnation.

Santa Muerte has many familiar nicknames. She is known variously as the Skinny Lady, the Bony Lady, White Sister, Godmother, co-Godmother, Powerful Lady, White Girl, and Pretty Girl, among others. As godmother and sister, and often described as a mother, the saint becomes a supernatural family member, approached with the same type of intimacy Mexicans would typically accord their relatives. She is seen as caring, kind but also like any woman who is scorned, may also be wrathful. As part of their offerings, devotees may share their meals, alcoholic beverages, and tobacco, as well as marijuana products, with her.

In some ways adherents view her as a supernatural version of themselves. One of the main attractions of folk saints is their similarities with devotees and often a favorite offering, such as a particular brand of beer is also the devotee’s favorite. For this very reason people feel closer to folk saints and believe they can establish stronger bonds as they typically share the same nationality and social class with their folk saint. This is much the case with Santa Muerte, who is said to understand the needs of her devotees. Additionally, many devotees are attracted by the leveling effect of Santa Muerte’s scythe, which obliterates divisions of race, class and gender. One of the most oft-repeated acclamations is that the Bony Lady “doesn’t discriminate.”

Herein lies one of Santa Muerte’s great advantages in the increasingly competitive religious marketplace of Mexico and in the greatest faith economy on earth here in the United States. Much more than Jesus, the canonized saints, and the myriad advocations of Mary, Saint Death’s present identity is highly flexible. It is largely dependent on how individual devotees perceive her. Despite her skeletal form, which suggests death and dormancy to the uninitiated, the Bony Lady is a supernatural action figure who heals, provides, and punishes, among other things.

It has been estimated that 5,000,000 to 7,000,000 Mexicans venerate Santa Muerte, but numbers are hard to gauge and no official polls exist to date. The folk saint appeals to a motley crew that includes high school students, nurses, housewives, taxi drivers, drug traffickers, politicians, musicians, doctors, teachers, farmers and lawyers. Because of her condemnation by both Catholic and Protestant churches, more affluent believers tend to keep their devotion to the saint of death private, adding to the difficulty of quantifying just how many individuals are devoted to the skeleton saint. The saint has a huge following among the most marginalized and those whose professions entail that death is always at their door. This could be drug dealers, but also policemen, prostitutes, prisoners, delivery drivers, taxi drivers, firefighters, or miners. In Mexico, many occupations we consider safe in the U.S. are perilous. For example, delivery drivers are at high risk of being held at gunpoint by criminals and having their merchandise and van stolen, they may not live to tell the tale. Poverty is also high in Mexico, over Sixty-two percent of people live on very low income and forty-two percent below the poverty line. Given lack of income, precarious living conditions and narco-violence, death is never far away, and so many poor feature among the Bony Lady’s faithful. Women are also very drawn to the folk saint because, as pointed out, the religion proffers them opportunities in leadership roles. But women also join as they are a high-risk group in Mexico given that femicide is severe; over ten women murdered daily and many more kidnapped to be raped, killed or sold into prostitution. Narcos do not only peddle drugs, they also work in the sex trade, the slave trade and the organs trafficking trade, among other iniquitous industries. Many women ask the Bone Mother to proffer protection to them from such nefarious characters, and to keep their families safe from them too.

In terms of regions, the saint is most popular in the following five areas: Guerrero, San Luis Potosi, Chiapas, Veracruz, Oaxaca and Mexico City. Guerrero, home to Acapulco has a fervent following due to high criminality in the area. However, the saint is venerated across the country where she occupies more shelf and floor space than any other saint in dozens of shops and market stalls specializing in the sale of religious and devotional items throughout Mexico. Her candles are often sold in mainstream supermarkets, especially in areas where many worship her. Votive candles are the best selling of all the Santa Muerte products. Costing only a dollar or two, they afford believers a relatively cheap way of thanking or petitioning the saint, but some unable to afford them may use any candle they can find.

Santa Muerte, as a new religious movement, is generally informal and unorganized and only recently became widespread in 2001. Because of this and the lack of any official body overseeing the faith, it has absorbed many influences from other religions such as Palo Mayombe and Santeria (in Veracruz and other places where Cubans interact with Mexicans, especially in such regions in the U.S.). New Age influences have also become integral to Santa Muerte, with the most obvious example of this being the use of the seven colors corresponding to the seven chakras being integrated into the faith as Santa Muerte’s seven powers.

Over the last two decades, the Bony Lady has been accompanying her devotees in their crossings into the United States, establishing herself along the 2,000 milelong border and in U.S. cities with Mexican immigrant communities. It is in the border states where she is most popular: Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, California, and Arizona. The faith as practised by Latino/as, although similar, tends to differ in some respects, especially in second generation devotees whose praxis changes from that of their parents who brought with them more Mexican traditions. In the younger generations, praxis becomes especially syncretic, absorbing influences from other Hispanic faiths as well as incorporating Heavy Metal elements popular in the U.S. Beyond these border states, devotion to Santa Muerte has spread to cities and towns deeper within the U.S., as indicated by the increasing availability of her devotional paraphernalia.

Los Angeles is the American mecca of the skeleton saint. It has two religious article stores bearing her name (Botanica Santa Muerte and Botanica De La Santa Muerte), and most botanicas stock many shelves of Santa Muerte paraphernalia. The City of Angels offers devotees three places of worship where they can thank the Angel of Death for miracles granted or petition her for assistance: Casa de Oración de la Santísima Muerte (Most Holy Death House of Prayer) and Templo Santa Muerte (Saint Death Temple) and one of the largest shrines to the folk saint, La Basilica de la Santa Muerte. These are three of the first temples dedicated to her in the United States.

In Mexican, Texan, and Californian penitentiaries, worship of the Bony Lady is so widespread that in many she is the leading object of devotion and even prison guards may worship her. In less than a decade the folk saint has become the matron saint of the Mexican penal system and is also popular in American prisons. Almost all TV news coverage of her rapidly increasing folk faith in the United States has been provided by local stations in border cities. These news reports tend to be sensationalistic, playing up Saint Death’s alleged ties to drug trafficking, murder, and even human sacrifice, but these fail to portray the more commonplace devotion among the many other groups who worship the folk saint. The mushrooming devotional base is a heterogeneous group with various afflictions and aspirations who turn to her for a range of favors the most popular of which tend to be love, health and wealth.

The media portray the skeleton saint as a dark deity turned to for dirty deeds, since like most folk saints she is amoral she can be asked for anything, including to bless criminal activities. Nevertheless, Santa Muerte as worshiped by most believers is neither the morally pure virgin nor the amoral spiritual mercenary who perpetrates all kinds of dark deeds but a flexible supernatural figure who can be called on for all manner of miracles and it is precisely her multifaceted miracle-working that has ensured her flourishing follower among devotees from all walks of life.

Much more than an object of contemplation, [Image at right] the Bony Lady is a saint of action. Santa Muerte’s popularity as a folk saint also derives from her unique control over life and death. This is especially appealing in spaces of violence, such as prisons or drug-riddled neighborhoods; however, this does not mean only narcos worship her, for their violence puts many other populations at risk, including children who also feature among her followers. Devotion, as I have noted in my fieldwork, can start very young. Children fearing danger for themselves or their parents may turn to the folk saint and although unable to buy her lavish offerings they may express their faith in  other ways, such as cleaning an altar, gifting a candy they got to her or saying a novena (a nine-day prayer) to the folk saint. [Image at right]

other ways, such as cleaning an altar, gifting a candy they got to her or saying a novena (a nine-day prayer) to the folk saint. [Image at right]

Her reputation as the most powerful and fastest acting saint is above all what attracts results-oriented believers to her altar. Most devotees perceive her as ranking higher than other saints, martyrs, and even the Virgin Mary in the celestial hierarchy. Saint Death is sometimes conceived of as an archangel (of death) who only takes orders from God himself. At other times she may be even considered more powerful than God since death is the ultimate power and become Goddess-like in her omnipotence and omniscience.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The logic of reciprocity underlies the way in which rank and file believers seek divine intervention. Much as in Christian contexts, the request for a miracle begins with a vow or promise. Thus, devotees request miracles from Saint Death in the same way they would from other saints, both folk and official, they then promise to repay her, often with offerings of victuals or libations, but they might also offer to change their ways, such as to stop gambling, taking drugs, drinking or driving recklessly.

Since many devotees are extremely poor even the smallest offering can be of significance, such as a bottle of water, especially in a country where clean water is a precious commodity. What distinguishes contracts with Santa Muerte is their binding power. If she is considered by many to be the most potent miracle worker on the religious landscape, she also has a reputation as a harsh punisher  of those who disrespect her. Santa Muerte is said to bring revenge on those who break their promises, [Image at right] this could be by causing minor misfortunes or even visiting death upon their family or friends.

of those who disrespect her. Santa Muerte is said to bring revenge on those who break their promises, [Image at right] this could be by causing minor misfortunes or even visiting death upon their family or friends.

Most devotees visit shrines to pay their respects to the folk saint and give her offerings; this is also where they say prayers and light candles. However, most largely practice the faith within the privacy of their own homes, at ad hoc altars that they have assembled. These may be simple or ornate, depending on the income of the devotee and the space they have. They might consist of nothing but a small statue of Santa Muerte or even just a votive with offerings to the folk saint, or the altar could contain many large and lavish statues of the saint and figurines, such as owls and other items related to the folk saint, like skulls. Offerings at altars and chapels often consist of alcohol, sometimes tequila or other hard liquors, such as mezcal and whisky for the more affluent and beer for the impecunious. Devotees also love to offer flowers, the colors of which general correspond to the favor being asked; the more lavish and larger the bouquet the better. They also gift her foods; these may be homemade items such as tamales, or they may be fruits. Apples are a favorite offering. They may also provide nuts, bread rolls chocolate and candy, among other foods. In Mexico cigarettes are typically offered, while taking from the Cuban influence in the U.S. cigars are also frequently offered. The Bony Lady is always offered glasses or bottles of water as, like her forebear la Parca, she is said to be perpetually parched.

Prayers, novenas, rosaries, and even “masses” for Santa Muerte generally preserve Catholic form and structure if not content. In this way, the new religious movement offers neophytes the familiarity of Mexican Catholicism along with the novelty of venerating an emerging folk saint. Most shrines and chapels hold a rosary once a month in the honor of the folk saint. However, witchcraft and folk medicine beliefs are also central to the faith. Devotees believe in hexes and the need to seek protection from the folk saint to break them. They also often believe in folk medicine and the importance of spiritual cleansing.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Drawing heavily on Catholic modes of worship, devotees employ a colorful range of rituals, however, they also practice witchcraft, and, as detailed, the rituals also incorporate elements from New Age spirituality. The general lack of formal doctrine and organization means that adherents are free to communicate with Saint Death in whatever manner suits them, and so there is tremendous heteropraxy, with some devotees using tarot, dreams or other methods to “talk” to their saint. Prayers are sometimes impromptu and designed ad hoc for the purpose. However, as chap books and other tomes, such as the Biblia de la Santa Muerte (a prayer book featuring petitions to the folk saint featured on amazon) circulate, a certain amount of orthopraxy is emerging.

One such typical prayer that has emerged was pioneered by the godmother of the new religious movement, Enriqueta Romero Romero (affectionately known as Doña Queta). She created the rosary to Santa Muerte (el rosario) by adapting a Catholic series of prayers dedicated to the Virgin. She took these prayers and largely swapped the Virgin’s name for Santa Muerte’s to honor the folk saint within a Catholic framework. Doña Queta organized the first public rosaries at her Tepito shrine in 2002, and since then the practice has proliferated throughout Mexico and in the United States. The monthly worship service at Doña Queta’s altar regularly attracts several thousand faithful.

Among the most common ways to petition Santa Muerte is through votive candles, often color coded for the specific type of intervention desired. Santa Muertistas may employ votive candles in the traditional Catholic way or they may add to this ritual with witchcraft rites. Spell books circulate which often advise devotees to recite prayers, light candles, but also use items as used in witchcraft during rituals. For example, a love spell may feature the use of a red Santa Muerte image, [Image at right] a red Santa Muerte statue but also a lock of hair or piece of clothing from a loved on that will need to be used in a specific way for the spell to be cast.

Most devotees use votive candles as mainline Catholics would, offering these wax lights as symbols of vows, for thanks or prayers. In addition to candles, devotees make offerings that correspond to things they desire. For example, red roses may be given for a petition for love, or money may be offered for good fortune. The main colors used in Santa Muerte rituals are red, white and black. This trio dominated in the earlier stages, but many have been added since then. Red has typically been for favors related to love and passion. White has been for cleansing, healing and harmony. Black has notoriously been said to be the color of black magic, hexing and for narcos and criminals seeking blessings and help with their nefarious activities. However, this is an incorrect portrayal; many use black for protection and safety and more recently, since COVID-19, this color is being used for protection and healing from the virus.

Votive candles, flowers and statue colors correspond to the favors being asked:

red: love, romance, passion, petitions of a sexual nature

black: vengeance, harm; protection and safety from coronavirus

white: purity, protection, gratitude, consecration, health, cleansing

blue: focus, insight and concentration; popular with students

brown: enlightenment, discernment, wisdom

gold: money, prosperity, abundance

purple: supernatural healing, for working magic, access to spiritual realms

green: justice, equality before the law

yellow: overcoming addiction

yellow, white and blue: road opener

yellow and green: business prosperity and money

black and red: reversing black magic and ill fortune, sending hexes back to sender

multicolored: multiple interventions

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The long period of furtive devotion ended on All Saints Day, 2001. Doña Queta, [Image at right] who at the time worked as a quesadilla vendor, publicly displayed her life-size Santa Muerte effigy outside her home in Tepito, Mexico City’s most notoriously dangerous barrio. In the decade since then, her historic shrine has become the new religious movement’s most popular in Mexico. More than any other devotional leader, Doña Queta has played the starring role in transforming occult veneration of the saint into a very public new religious movement.

Just a few miles away, self-declared “Archbishop” David Romo founded the first church dedicated to the Santa Muerte. Borrowing heavily from Roman Catholic liturgy and doctrine, the Traditional Holy Catholic Apostolic Church Mex-USA offered “masses,” weddings, baptisms, exorcisms, and other services commonly found at most Catholic churches in Latin America, but it was closed down in 2011 when Romo was arrested for multiple criminal charges, including kidnapping.

In the United States, the Los Angeles based Templo Santa Muerte offers a full range of Catholic-like sacraments and services, including weddings, baptisms, and monthly rosaries. The Templo’s website hosts a chat room and streams music and podcasts of masses to those who cannot make it to the services offered by “Professors” Sahara and Sisyphus, founders of the Templo. Both leaders emigrated to the United States from Mexico. The latter’s training included an apprenticeship with two Mexican shamans, one of whom “taught him to speak to Most Holy Death.” Their rituals are very much influenced by New Age rites and are highly syncretic due to the U.S. influence.

A few miles across town is the Santuario Universal de Santa Muerte (Saint Death Universal Sanctuary). The Sanctuary is located in the heart of LA’s Mexican and Central American immigrant community. “Professor” Santiago Guadalupe, originally from Catemaco, Veracruz, a town famous for witchcraft, is the Santa Muerte shaman who presides over this storefront church. Faithful believers visit the Sanctuary for baptisms, weddings, rosaries, novenas, exorcisms, cleansings, and individual spiritual counseling.

Enriqueta Vargas [Image at right] was one of the most famous leaders. She started The SMI (Santa Muerte Internacional) temple in Tultitlan in 2008, beneath the feet of the largest statue of Santa Muerte in the world, which her son had built before his murder. She established a network of shrines across Mexico and into other Latin American countries, such as Costa Rica, spreading the faith. Through her innovative use of social media platforms and digital communication tools, along with her charismatic Evangelical-style leadership, the organization has become a popular source for information on Santa Muerte. It is built upon a strong global community of devotees connected through live video coverage of regular worship services at the shrine and digital outreach on Facebook. When she died in 2018 from cancer, her daughter took over and continues her mother’s work.

Aside from these most famous shrines, innumerable chapels have been started across Mexico, with men and women spreading the faith. In large part it has been women who have established the most shrines to the Saint of Death, creating prestige and power for themselves and guiding community relations. Other famous female shrine owners and Santa Muerte leaders include Yuri Mendez, who over a decade ago established the largest shrine to Santa Muerte in Cancun; it is also the most prominent in the region of Quintana Roo. The chapel features innumerable statues of the female folk saint of death, and some have Mayan-derived names, such as Yuritzia, the most important and powerful statue in the shrine with whom Mendez has a special bond. Mendez is considered a guide within her community. As a self-identified witch, shaman and healer, she offers services of healing, magic and curanderismo (curing  through plant medicines). As a “bruja de la 3 virtudes” (witch of the three virtues), she offers red, black and white magic to devotes. Her rosary every second day of the month attracts hundreds of devotees. Mendez has a distinctly feminist outlook on devotion to death, using her prestige and social capital as a Santa Muerte leader to highlight women’s issues. These include femicide, and aiding women with distinctly feminine issues, such as domestic violence or men who do not pay for child support.

through plant medicines). As a “bruja de la 3 virtudes” (witch of the three virtues), she offers red, black and white magic to devotes. Her rosary every second day of the month attracts hundreds of devotees. Mendez has a distinctly feminist outlook on devotion to death, using her prestige and social capital as a Santa Muerte leader to highlight women’s issues. These include femicide, and aiding women with distinctly feminine issues, such as domestic violence or men who do not pay for child support.

Elena Martinez Perez [Image at right] is another notorious Santa Muerte figure in the region of Oaxaca. The Indigenous Zapotec sabia (wise woman) established her shrine in Oaxaca to thank Santa Muerte for a miracle of healing in c. 2002. It has expanded from a small makeshift structure and has been rebuilt several times; it is now a large and renowned chapel that receives hundreds of weekly visits. Her family, largely the female members, help her run, clean and decorate it, while her sons and grandsons play a lesser but still important role in construction and other tasks that require heavy lifting. Her daughter-in-law and daughter more recently opened a shop by the shrine where they sell candles to the many devotees who come to pray. The shrine is famous in the region for its incredible celebrations honoring Santa Muerte during Day of the Dead in November. This includes two days of rituals, music and festivities during which the shrine is decorated sumptuously. These celebrations are uniquely Oaxacan and influenced by Indigenous culture.

Other notable female shrine owners are Adriana Llubere who became a devotee in the year 2000 and in 2010 erected a chapel  featuring a statue which she calls Cañitas, in San Mateo Atenco. [Image at right] Measuring one meter eighty centimeters high, Cañitas is perhaps the only representation of Santa Muerte that is capable of standing or sitting, as required for different times or circumstances. Llubere is known for rolling her statue around in a wheelchair, especially during special occasions. The statue is the unofficial matron saint of those who have been falsely incarcerated. After being freed from jail for what she claims was bogus charges, Llubere commissioned the prisoners of Almoloya de Juárez to make the statue for her. To this day the prisoners there, in penitentiaries across Mexico, and even in the U.S., have a special attachment to this effigy, especially those who believe they were innocent. Upon their release, many make a pilgrimage to thank Cañitas, whose name means little inmate, as being “en cana” (slang for being in jail).

featuring a statue which she calls Cañitas, in San Mateo Atenco. [Image at right] Measuring one meter eighty centimeters high, Cañitas is perhaps the only representation of Santa Muerte that is capable of standing or sitting, as required for different times or circumstances. Llubere is known for rolling her statue around in a wheelchair, especially during special occasions. The statue is the unofficial matron saint of those who have been falsely incarcerated. After being freed from jail for what she claims was bogus charges, Llubere commissioned the prisoners of Almoloya de Juárez to make the statue for her. To this day the prisoners there, in penitentiaries across Mexico, and even in the U.S., have a special attachment to this effigy, especially those who believe they were innocent. Upon their release, many make a pilgrimage to thank Cañitas, whose name means little inmate, as being “en cana” (slang for being in jail).

Other notable shrine owners are Sorraya Arredondo who owns a large chapel called “Angel Alas Negras” (Angel with Black Wings) in Tula in Hidalgo that is dedicated uniquely to Santa Muerte in her black form and features a large befeathered statue known as La Guerrera Azteca, the Aztec Warrior. It honors the folk saint as of Nahua origin. About an hour and a half away in Tizayuca Hidalgo, Maria Dolores Hernández owns a shrine known as La Niña Blanca de Tizayuca, the White Girl of Tizayuca where she offers tarot and other spiritual services. Michelle Aguilar Espinoza and her family own a famous shrine in San Juan Aragon called la Capilla de Alondra since its wooden effigy of Santa Muerte is called Alondra. It wields a wooden scythe that has been passed down for generations and is believed to have special powers.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

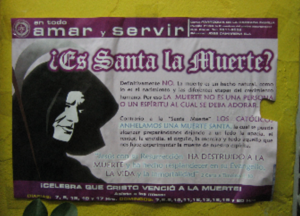

The Catholic Church in Mexico has taken a decisive stance against Santa Muerte, denouncing the new religious movement on the grounds that the veneration of death is tantamount to honoring an enemy of Christ. [Image at right] The Church argues that Christ defeated death through resurrection; therefore, his followers must align themselves against death and its representatives, including Santa Muerte. The previous Mexican president, Felipe Calderon, was a member of the National Action Party (PAN), founded by conservative Roman Catholics in 1939. Calderon’s administration declared Santa Muerte religious enemy number one of the Mexican state. In March 2009 the Mexican army bulldozed dozens of roadside shrines dedicated to the folk saint along the US-Mexico border. However, under the current president, AMLO, there has been less pressure to destroy shrines.

A number of high-profile drug kingpins and individuals affiliated with kidnapping organizations are Santa Muertistas. The prevalence of Santa Muerte altars at crime scenes and in the cells of those imprisoned has created the impression that she is a narco-saint; however, this is due to press sensationalism. Many narcos worship St. Jude, Jesus, the Virgin of Guadalupe, El Nino de Atocha (an advocation of the Christ Child), these figures have not attracted the same media attention. Many of her devotees are members of society who have been marginalized by the prevailing socio-order. This could be due to their sexual orientation or due to their class, since the working class is typically looked down upon. In either event, because of their low status in the eyes of the upper classes and the powerful, they and their faith are often dismissed as deviant.

IMAGES**

** All photos contained herein are the intellectual property of Kate Kingsbury or R. Andrew Chesnut. They are featured in the profile as part of a one-time licensing agreement with the World Religions and Spirituality Project. Reproduction or other use is prohibited.

Image #1: A volcanic rock statue of Santa Muerte in the temple to the folk saint in Morelia, Michoacán with votive candles burning.

Image #2: An Indigenous depiction of Santa Muerte replete with Aztec plumed headdress.

Image #3: Santa Muerte depicted as she who delivers justice, holding the scales in her hand.

Image #4: Devotee of Santa Muerte holding his two statues, which he has brought to Tepito to be blessed at the Rosary held at Doña Queta’s famous shrine.

Image #5: Young female devotee of Santa Muerte clutching her statue of the Saint of Death just as she clutches onto life living in the dangerous neighbourhood of Tepito.

Image #6: A Santa Muerte Addiction card on which a devotee makes a pledge to the folk saint to stop drinking or taking drugs or engaging in other vices for a specific period of time.

Image #7: Santa Muerte Votive Candle burning brightly with the deepest desires of a Santa Muerte devotee who has lit it to supplicate the saint for a special favour.

Image #8: Doña Queta blessing a child in her shop in Tepito that abuts the world famous shrine she established to Santa Muerte.

Image #9: Enriqueta Vargas, the other major devotional pioneer, who established a transnational network of churches known as SMI (Santa Muerte Internacional) that extends across the Americas and even into the U.K.

Image #10: Yuri Mendez, leader of the largest shrine to Santa Muerte in Quintana Roo, She self-identifies as a bruja (witch), curandera (healer) and shaman of Santa Muerte.

Image #11: Doña Elena, leader of the first and most important chapel to Santa Muerte in the region of Oaxaca. The Zapotec leader stands before a statue of Santa Muerte depicted as Indigenous.

Image #12: Poster denouncing Santa Muerte as satanic.

REFERENCES**

** The material in this profile is drawn from the following papers and book: Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “Mexican Folk Saint Santa Muerte: The Fastest Growing New Religious Movement in the West,” The Global Catholic Review; Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2021. “Syncretic Santa Muerte: Holy Death and Religious Bricolage.” Religions 12:212-32; and R. Andrew Chesnut, Devoted to Death (Oxford 2012).

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Aguirre, Beltran. 1958. Cuijla esbozo etnográfico de un pueblo negro Lecturas Mexicanas.

Aridjis, Eva, dir. 2008. La Santa Muerte. Navarre, FL: Navarre Press.

Aridjis, Homero. 2004. La Santa Muerte: Sexteto del amor, las mujeres, los perros y la muerte. Mexico City: Conaculta.

Bernal S., María de la Luz. 1982. Mitos y magos mexicanos. Second Edition. Colonia Juárez, Mexico: Grupo Editorial Gaceta.

Chesnut, R. Andrew. 2012. “Santa Muerte: Mexico’s Devotion to the Saint of Death.” Huffington Post, January 7. Accessed from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/r-andrew-chesnut/santa-muerte-saint-of-death_b_1189557.html

on 25 March 2021.

Chesnut, R. Andrew. 2003. Competitive Spirits: Latin America’s New Religious Economy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cortes, Fernando, dir. 1976. El miedo no anda en burro. Diana Films.

Del Toro, Paco, dir. 2007. La Santa Muerte. Armagedon Producciones.

Graziano, Frank. 2007. Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm. 1974. “Godfather Death.” Tale 44 in The Complete Grimm’s Fairy Tales. New York: Pantheon. Accessed from http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm044.html on 20 February 2012.

Holman, E. Bryant. 2007. The Santisima Muerte: A Mexican Folk Saint. Self-published.

Kelly, Isabel. 1965. Folk Practices in North Mexico: Birth Customs, Folk Medicine, and Spiritualism in the Laguna Zone. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Kingsbury, Kate 2021. “Danger, Distress and Death: Female Followers of Santa Muerte.” In A Global Vision of Violence: Persecution, Media, and Martyrdom in World Christianity, edited by D. Kirkpatrick and J. Bruner. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Kingsbury, Kate. 2021.”Death in Cancun: Sun, Sea and Santa Muerte.”’Anthropology and Humanism Quarterly 46:1-16

Kingsbury, Kate. 2020. “At Death`s Door in Cancun: Meeting Santa Muerte Witch Yuri Mendez.” Skeleton Saint. Accessed from https://skeletonsaint.com/2020/02/21/at-deaths-door-in-cancun-meeting-santa-muerte-witch-yuri-mendez/ on 25 March 2021.

Kingsbury, Kate. 2020. “Death is Women’s Work: the Female Followers of Santa Muerte.”’ International Journal of Latin American Religions 5:1-23.

Kingsbury, Kate. 2020. “Doctor Death and Coronavirus.” Anthropologica 63:311-21.

Kingsbury, Kate. 2018. “Mighty Mexican Mothers: Santa Muerte as Female Empowerment in Oaxaca.” Skeleton Saint. Accessed from https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=Mighty+Mexican+Mothers%3A+Santa+Muerte+as+Female+Empowerment+in+Oaxaca on 25 March 2021.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2021. “Syncretic Santa Muerte: Holy Death and Religious Bricolage.” Religions 12:212-32.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “Holy Death in Times of Coronavirus: Santa Muerte, the Salubrious Saint of Mexico.” International Journal of Latin American Religions 4:194-217.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “Life and Death in the Time of Coronavirus: Santa Muerte, the ‘Holy Healer’,” The Global Catholic Review. Accessed from https://www.patheos.com/blogs/theglobalcatholicreview/2020/03/life-and-death-in-the-time-of-coronavirus-santa-muerte-the-holy-healer/ on 25 March 2021.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “Mexican Folk Saint Santa Muerte: The Fastest Growing New Religious Movement in the West,” The Global Catholic Review. Accessed from https://www.patheos.com/blogs/theglobalcatholicreview/2019/10/mexican-folk-saint-santa-muerte-the-fastest-growing-new-religious-movement-in-the-west/ on 25 March 2021.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “Not Just a Narcosaint: Santa Muerte as Matron Saint of the Mexican Drug War.” International Journal of Latin American Religions 4:25-47.

Kingsbury, Kate and Chesnut, Andrew. 2020. “Santa Muerte: Sainte Matronne de l’amour et de la mort.” Anthropologica 62:380-93.

Kingsbury, Kate and Andrew Chesnut. 2020. “The Materiality of Mother Muerte in Michoacan: The Tangibility of Devotion to Saint Death.” Skeleton Saint. Accessed from https://skeletonsaint.com/2020/12/12/the-materiality-of-mother-muerte-in-michoacan/ on 25 March 2021.

La Biblia de la Santa Muerte. 2008. Mexico City: Editores Mexicanos Unidos.

Lewis, Oscar. 1961. The Children of Sánchez: Autobiography of a Mexican Family. New York: Random House.

Lomnitz, Claudio. 2008. Death and the Idea of Mexico. New York: Zone Books.

Martínez Gil, Fernando. 1993. Muerte y sociedad en la España de los Austrias. Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Navarrete, Carlos. 1982. San Pascualito Rey y el culto a la muerte en Chiapas. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas.

Olavarrieta Marenco, Marcela. 1977. Magia en los Tuxtlas, Veracruz. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional Indigenista.

Perdigón Castañeda, J. Katia. 2008. La Santa Muerte: Protectora de los hombres. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Thompson, John. 1998. “Santísima Muerte: On the Origin and Development of a Mexican Occult Image.” Journal of the Southwest 40:405-436.

Toor, Frances. 1947. A Treasury of Mexican Folkways. New York: Crown.

Villarreal, Mario. “Mexican Elections: The Candidates.” American Enterprise Institute. Accessed from http://www.aei.org/docLib/20060503_VillarrealMexicanElections.pdf. on 20 February 2012.

Publication Date:

26 March 2021