Cerchio Druidico Italiano

CERCHIO DRUIDICO ITALIANO (ITALIAN DRUIDIC CIRCLE) TIMELINE

1970: Luigi “Ossian” D’Ambrosio was born in Nordhorn, Germany.

1980: D’Ambrosio moved to Biella, Italy, with his family.

1994: The Branco dell’Antica Quercia (The Ancient Oak Pack) was established and the website launched.

1996: The group celebrated its first Beltane Festival at Zumaglia Castle (Biella, Italy).

1998: The Branco dell’Antica Quercia became the Antica Quercia (The Ancient Oak).

2001: D’Ambrosio married and received his first initiation.

2002-2003: The festival location moved to Magnano (Biella, Italy) and then to Mottalciata (Biella, Italy).

2003: Antica Quercia joined the Circolo dei Trivi (the Wiccan group set in Milan) for the organization of the second National Convention on Wicca that took the name of “The Council of Druids and Witches.” The partnership between Antica Quercia and Circolo dei Trivi became one of the most durable in the Italian neopagan landscape.

2005: The festival took place at Arcobaleno Park in Masserano (Biella, Italy).

2008 (May): The Cerchio Druidico Italiano (Italian Druidic Circle) was established up during the Beltane Festival in Masserano.

2008 (June): During the midsummer solstice celebration, D’Ambrosio created guidelines for the Cerchio Druidico.

2008 (October): Philip Carr Gomm, president of The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, conducted a seminar for the first time in Italy.

2009: D’Ambrosio was invited to celebrate the Summer Solstice in Stonehenge.

2015: Antica Quercia, Circolo dei Trivi and several pagan associations created Unione delle Comunità Neopagane (UCN Italia – Union of Neopagan Communities).

2016: The twentieth Beltane Festival was celebrated in Masserano (Biella, Italy).

2018 (May): Caroline Wise, president of the Fellowship of Isis, came to the Beltane Festival to celebrate the Cerchio Druidico’s tenth anniversary.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Cerchio Druidico Italiano is a spiritual movement based on the ancient spirituality of the Celts, rediscovered for the first time in the eighteenth century on the British Isles. The movement changed and adapted to sociocultural circumstances and to other movements, such as occultism. Cerchio Druidico spread throughout Europe and arrived in Italy during the 1990s, intertwining re-enactment and spirituality. That is, some associations are born as reminiscent and later face spirituality, while others are born as explicitly spiritual but then face the historical discourse to discover the ancient Celtic past. Historical studies cause these cultural associations to face the break with the pagan past in two different ways: on the one hand, there are those who call themselves reconstructors; on the other hand, there are those who admit the reinvention of tradition.

Elaborating a chronology of Italian groups is a complicated operation since many have lifespans that do not exceed twenty years, and they often alter their names multiple time and/or change leaders. The first appearances that can be documented date back to 1996 with the birth of the Festival of Beltane in Biella, organized by the Cultural Association Antica Quercia (initially established in 1992) and Celtica (organized in the Aosta Valley by the Mor Arth Association). Also in 1996, the Cultural Association Terra Insubre was established in Varese, where it deals with historical and archaeological research on Alpine, Celtic and Germanic peoples. Unlike other groups claiming to be apolitical, this one has a more explicit political mission. In 1998, the first Trigallia International Celtic Festival was held; it then took place every two years until 2005, when its last event occurred. This event was replaced by the Trigallia Celtic Cultural Association, founded again in 1998 following the success of the festival.

It was a few years later that openly spiritual groups began to appear. The first, the Reformed Spiritual Movement of Insubria Natives, dates to 2003, but it survived for only a few years. In 2008, the Cerchio Druidico Italiano was created during the Beltane festival of that year. There were two other relevant but transitory groups, the Italian Bardica and Druidic Academy (OLNO, Oltre la Nona Onda) and the Grand Druidic Lodge of Italy (GralDrui). In Italy, there is also a national section of the OBOD that offers an online course.

The founder and leader of Cerchio Druidico Italiano is Luigi “Ossian” D’Ambrosio. [Image at right] Ossian was born in Nordhorn, Germany in 1970. During his childhood, his family moved to Biella, Italy, where he has continued to live. He is an artisan jeweler and a journalist on esotericism. He is also a musician. In 1988, he founded the Opera IX, a black metal band that is among the most long-running in Italy. This bond with music is very important to him, because it is through this musical genre that he approached paganism for the first time during his adolescence, thanks to the lyrics of various foreign bands.

His spiritual path has been multifaceted. He initially approached the first forms of organized Italian neopaganism, associations connected to modern witchcraft. He appreciated their structure and activities, but he didn’t recognize himself in that spirituality. Consequently, he began to research neopaganism and met Emanuele Pauletti, who became his mentor. Pauletti was associated with the Breton Druidic tradition and lead Ossian to seek more direct links with the northern Italian territory. Then, he studied shamanism at the Michael Harner Shamanic Studies Foundation and discovered Celtic shamanism. During his research, he founded his first association in 1994, Branco of the Antica Quercia (Ancient Oak Pack), which later became the Anticaquercia Association, through which he organized the first Beltane Festival in 1998. The main objective of the Association was research and profile-raising.

The Beltane Festival is one of the longest-running Celtic Italian festivals; it was established at Arcobaleno Park in Masserano, Biella. During the 2008 Beltane Festival, the Cerchio Druidico Italiano (Italian Druidic Circle) was founded. As Ossian recounts in his book, La via delle querce (2013), the birth of the Cerchio Druidico allowed a division of interests between the two different associations, leaving them free to better focus on certain features: the Antica Quercia Association (Antica Quercia Association website n.d.) deals with the most artistic and cultural side, while the Cerchio engages itself in the spiritual path, allowing the creation of a more neo-druidic space within the group.

In October of the same year, Philip Carr Gomm (The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids’ president) was invited by D’Ambrosio and Davide “Cronos” Marré (the Circolo dei Trivi’s president (the first Italian Wiccan coven, in Milan) to give a seminar. That seminar was one of the most important events for the Cerchio Druidico Italiano as it served as an educational moment for the entire membership.

In 2009, D’Ambrosio became the first Italian Druid invited to the celebration of the Summer Solstice in Stonehenge, which is celebrated by The Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids (OBOD).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Neo-druidism is one of the movements in the broader category of Neopaganism; movements in this category share in common the project of revitalizing or reconstructing the traditions of pre-Christian polytheistic cults (Harvey 2016). There are two different and antipodal ways to live neo-druidism in Italy: some interpret spirituality as a lifestyle potentially applicable to any religion while others live it as a religion. Cerchio Druidico Italiano follows this second path and is the only group in northern Italy that offers such an explicit spiritual path.

The group puts into practice a process of reinvention of tradition. Their leader is aware of the rift with the ancient tradition caused by the advent of Christianity. He has not sought to reclaim the earlier Celtic spirituality, given the difficulties of accurate historical reconstruction (D’Ambrosio 2013). Rather, the Cerchio Druidico offers a contemporary spiritual path in order to create a deep link between humans and nature. They envision a connection with the land, a sort of rediscovery of the history and the peculiarity of the territory where people have lived. The goal is to create a neopagan community based on mutual support and self-responsibility. The aim is clearly ecological and is consistent with neopagan movements as nature-based religions (Harvey 2016).

Indeed, Cerchio Druidico Italiano puts ecopaganism at the centre of its spirituality and practice. Its ecological activism is entrusted to the sensitivity of the individual, but what the group proposes is a practical and constant action in order to establish positive relations between the human being and other living creatures. The objective is to restore humanity back to its place in nature in order to allow peaceful coexistence. The ethical mission of neopaganism is revealed by the choice of the place where Cerchio Druidico Italiano holds its meeting. The group chose Arcobaleno Park, a private park in a protected area that is in environmental recovery, as it is an abandoned quarry.

This link with nature is also expressed in the representation of divinities. Neopaganism shares with neodruidism placing bi-theism at the centre of its beliefs; The God and The Goddess thus represent two aspects of the universe. This allows them to propose that every deity humanity has ever conceived over the centuries is no more than the manifestation of a specific aspect of these two entities.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Cerchio Druidico Italiano shares with broader Neopaganism the Wheel of the Year, a cyclic annual calendar with eight seasonal festivities.[Image at right] Half of these festivals are solar and the other half are lunar; the most recent are defined as fire festivals. This is a canon common to every contemporary Paganism, with names having been reconstructed by different traditions (Hutton 2008). Only the celebrations of Samhain and Beltane are public; the others are all private for the members of Cerchio Druidico.

Solar festivities are agro-pastoral celebrations. Cerchio Druidico uses the names proposed by the Bard Iolo Morgangaw rather than the more traditional titles (Yule, Ostara, Litha and Imbolc):

The Spring Equinox, Alban Eiler (Earth’s Light), falls between March 21 and 22.

The Winter Solstice, Alban Arthuan (Arthur’s Light), falls between December 20 and 23.

The Summer Solstice, Alban Hefin (Shore’s Light), falls between June 20 and 23.

The Autumn Equinox, Alban Elfed (Water’s Light), falls between September 20 and 21.

Fire festivities are:

Samonios, celebrated between October and November, is the Celtic New Year’s Day.

Brigantia/Imbolc, celebrated in the first days of February.

Beltane, celebrated in the first days of May.

Lugnasa, celebrated in the first days of August.

For these ceremonies, members of Cerchio Druidico Italiano meet in an open space in nature, usually Arcobaleno Park. They gather in a circle and follow a ritual on a script the group has developed. These ceremonies all have the same primary structure: the circle opens; there is a greeting and calling for the four cardinal points and the respective divinities; specific ritual gestures of the holiday are performed; the circle then closes, dismissing the forces previously called. Each ceremony draws on folkloristic elements from different traditions. An integral part of the ceremony is the following meal shared by the group. In this way, sacred and profane aspects merge, blurring the boundaries between the two and allowing the creation of a space of conviviality among the members.

In addition to these festivities linked to the Wheel of the Year, there are many other ritual moments, mainly connected with group members’ life cycles. The Welcome Rite and the New-born Presentation to the community happens when parents give the child his/her name in front of the whole group. Other ritual moments follow the most important events in the child’s life (e.g. losing the first tooth or the first day at school). The second and third rituals are the Sacred Union and Separation. The Sacred Union is a marriage where a couple presents itself as a family; Separation is the ritual redefining the relationship with the whole group in case the former fails. Sacred marriages are offered both during the year and during the Feast of Beltane and are celebrated not only by Ossian but by each member of Cerchio Druidico who has achieved initiation. Finally, there is the Transition Rite, the funerals or memorials to honour the elders. Other ritual moments are dedicated to the initiation of group members. These rites are the first and last steps of a specific spiritual path.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Cerchio Druidico celebrated its first ten years of life in May 2018, and during this decade so many participants joined the group that an independent “grove” had to be created: the Triplice Cinta Druidica. [Image at right]

The structure of Cerchio Drudico Italiano is peculiar: Ossian is its centre and engine, but the group denies any form of pyramidal power in favour of a circular assembly. The group’s position is that a leader is needed to coordinate the actions of the different members who, like pieces of a gear, must take care of each one of their tasks (D’Ambrosio 2013).

The spiritual path in Cerchio Druidico consists of three steps: bard, ovate and druid. During the bard stage, neophytes must work on their creativity and their emotional sphere. Neophytes become Bards after attending the Cerchio Druidico for a year and a day. At that point they are “dedicated.” The Ovate is a doctor and a fortune-teller. Ovates are now identified with shamans because they are the ones who can move between both worlds. Again, after a year and a day the person is initiated into Cerchio Druidico.

Bards are preservers of the historical memory of the people. They are the artists who preserve and transmit tradition through their work. They are the ones who make ideas tangible, thus manifesting the will of the divinity. The symbolism linked to this figure is varied. Bards are assigned the colour blue, the water element and the West direction; the season is spring and the tree is the birch (“beith”), both symbols of the beginning (D’ambrosio 2013).

What inspires the Bard is the Awen, one of the main elements of modern Druidism. It is the name and symbol that Iolo Morgangw assigns to inspiration, which enables the Goddess to speak through the Bard. In many bardic ceremonies there is a moment when songs are dedicated to the invocation of the Awen that must descend over the participating Bards to inspire them for the performance (Harvey 1997). Cerchio Druidico in this is no exception; in all ceremonies there is a moment at the beginning during which the Awen is invoked in chorus to inspire and connect the divinity with the participants.

Ovates are shamans and healers. They are the ones who travel between worlds, being able to speak with what is more than human. Thanks to this ability, they can also perform the function of seers and interpret messages from the gods. This connection with the divine allows a profound connection with nature to be taken care of by the modern Ovate. The colour associated with the Ovate is green, the seasons are autumn and winter, the night is its moment, and the associated Ogham tree is the yew (Harvey 1997; D’ambrosio 2013).

Modern Druid functions are carried out in nature and in the recovery of rituals set in the woods that serve to recreate the link with the environment. Associated with the druid are the colour white, the oghamic trees of the oak and the mistletoe, the East direction, where the sun rises, and the summer season.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Cerchio Druidico has faced both internal and external issues. Internally, the group has attempted to create a network with other Italian druidic groups. However, that effort has not yet been successful as the various groups have been unable to agree on spiritual guidelines

Externally, Cerchio Druidico is located outside the Catholic cultural mainstream in Italy and therefore has been vulnerable to being labelled a “cult” (Wallis 1976). Although members are in fact well integrated into Italian society, they sometimes conceal group membership to avoid a negative label. The group is seeking to counter negative attribution by joining in the “Article 8 Project.” This project is supported by the Unione delle Comunità Neopagane (UCN), a coalition of associations, groups and individual pagans (Unione delle Comunità Neopagane website n.d.). The goal of UCN is the recognition of a neopagan religion by the Italian government or, alternatively, the recognition of different individual neopagan groups. Government recognition would be a significant step in gaining public acceptance.

IMAGES

Image #1: Luigi “Ossian” D’Ambrosio.

Image #2: A Cherchio Druidico ritual gathering.

Image #3: The Cherchio Druidico logo.

REFERENCES

AnticaQuercia. n.d. Antica Quercia website. Accessed from http://www.anticaquercia.com on 10 June 2018.

Cerchio Druidico Italiano. 2016. Il Druidismo Moderno del Cerchio Drudico Italiano: Testo Introduttivo.

Cerchio Druidico Italiano. 2012. Cerchio Druidico Italiano website. Accessed from http://www.cerchiodruidico.it on 10 June 2018.

D’Ambrosio, Ossian. 2013. La via delle querce. Introduzione al druidismo moderno, Psiche 2.

Harvey, Graham. 2016. “Paganism.” Pp. 345-67 in Religions in the Modern World, edited by Linda Woodhead, Christopher Partridge and Hiroko Kawanami, London: Routledge.

Harvey, Graham. 1997. Listening People, Speaking Earth, Contemporary Paganism, New York: New York University Press.

Hutton, Ronald. 2008. Modern Pagan Festival: A Study in the Nature of Tradition, Folklore 119:251-73.

Wallis, Roy. 1977. The Road to Total Freedom. A Sociological analysis of Scientology, New York: Columbia University Press.

Unione delle Comunità Neopagane website. n.d. Accessed from http://www.neopaganesimo.it/ on 20 March 2019.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Harvey, Graham. 2011. Contemporary Paganism: Religions of the Earth from Druids and Witches to Heathens and Ecofeminists, Second Edition. New York: New York University Press.

Post Date:

12 November 2019

Joaquim Silva Vilela

JOAQUIM SILVA VILELA TIMELINE

1950 (April 20): Joaquim Silva Vilela was born in Pocrane in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

1960: Vilela moved to the federal district surrounding Brasília with his family, the year of the new capital city’s inauguration.

1977: Vilela participated in his first juried artist salon. The following year (1978) he received a prize in the 1º Salão de Artes Plásticas das Cidades Satélites.

1977 or 1978: Vilela visited the Valley of the Dawn for the first time.

1990s: Vilela abandoned painting and began producing spirit portraits on his computer using Photoshop.

BIOGRAPHY

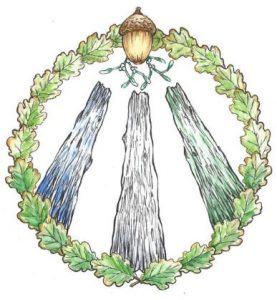

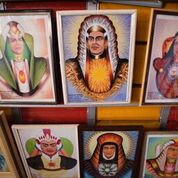

Joaquim Vilela (b. 1950) is a self-taught painter and illustrator responsible for much of the iconography of the Valley of the Dawn (Vale do Amanhecer), one of Brazil’s largest alternative religions. [Image a t right] Founded in the early 1960s by an itinerant truck driver and clairvoyant affectionately referred to as Aunt Neiva (1925-1985), the Valley of the Dawn has affiliated temples in every Brazilian state as well as Portugal, England, the United States and other international locales. Its headquarters, the Mother Temple, is located in the town of Planaltina in the federal district outside the Brazilian capital of Brasília. Vilela’s artwork is an integral part of the movement, whose Space Age cosmology synthesizes elements drawn from Christianity, Spiritism, and Afro-Brazilian religions, as well as Theosophy and other esoteric traditions.

t right] Founded in the early 1960s by an itinerant truck driver and clairvoyant affectionately referred to as Aunt Neiva (1925-1985), the Valley of the Dawn has affiliated temples in every Brazilian state as well as Portugal, England, the United States and other international locales. Its headquarters, the Mother Temple, is located in the town of Planaltina in the federal district outside the Brazilian capital of Brasília. Vilela’s artwork is an integral part of the movement, whose Space Age cosmology synthesizes elements drawn from Christianity, Spiritism, and Afro-Brazilian religions, as well as Theosophy and other esoteric traditions.

According to Valley doctrine, all human beings are inherently mediums and Vilela asserts that his particular faculty of mediumship allows him to visualize spiritual dimensions far beyond the physical world. This process is central to his artistic production. “The artist is a visionary, an intermediary,” he said in an interview, “registering on the physical plane that which he brings from the spiritual” (Hayes 2019). The imagery that Vilela has produced over the years has influenced profoundly how Valley members imagine an alternative universe to which they orient not only their ritual practices but their lives. In making otherwise invisible spiritual realities visible, Joaquim Vilela’s work brings the Valley’s imaginary world and its complex theology to life for adherents. His renderings of the highly evolved spirit mentors central to the Valley of the  Dawn’s are prominently displayed in public and private settings and are a focal point for individual prayer and petitions for spiritual intercession. [Image at right]

Dawn’s are prominently displayed in public and private settings and are a focal point for individual prayer and petitions for spiritual intercession. [Image at right]

Vilela was born in 1950, one of nine children in a devoutly evangelical Christian family in Pocrane, a small town in the interior state of Minas Gerais. From an early age he displayed an aptitude for art and wrote and illustrated his own comic books inspired by his love of science-fiction adventure tales. He was captivated especially by the futuristic technology depicted in Flash Gordon comic strips and considers its creator Alex Raymond a visionary who foresaw things that would only be invented generations later. Vilela’s early artwork often featured fantastic creatures, beings glimpsed in dreams or conjured by the restless mind of a child obsessed with stories of superheroes and interstellar space travel. Even as a small boy Vilela knew that his fantasy world was better kept private since such fanciful creations had no place within the rigidly conservative faith of his parents, for whom there was only God and the devil.

Although it was only later that he fully understood this, Vilela reported that his art “always had a spiritual influence” (Hayes 2019). Images of “inferior beings, suffering spirits, other dimensions and planes of existence” frequently appeared in his early works. Vilela attributes this to a precocious mediumship, which manifested as “extremely strange and terrifying visions.” These experiences were distressing in and of themselves, but even more so because he felt that he could not tell his parents: “I suffered greatly because I was alone and I couldn’t talk about it with anyone because my parents’ religious beliefs did not permit them to even speak of such a thing. Because if I said anything I was excommunicated.” He was particularly afraid of angering his father, who “would give me beating and say that I was inventing things” (Hayes 2019). Drawing and painting offered the young Vilela a way to objectify and assimilate these experiences.

In 1960, Vilela’s family moved to the new federal district where the Brazilian government was constructing the new capital city of Brasília. Like thousands of other Brazilians, they were inspired by President Juscelino Kubitschek’s vision for a new, modern Brazil. And, like many of these new migrants, the family settled in one of the nondescript satellite cities ringing the capital.

As a young man Vilela got a job at a local print shop and practiced his own art on the side. He says that when a customer offered him a lot of money for one of his paintings, he was emboldened to quit the print shop in order to pursue his dream of being an artist. He vowed to never work again for someone else’s gain, although it would be some time before he was able to fully realize that goal. In 1977, Vilela began to enter his work in local juried artist exhibitions and won multiple prizes over the years.

Around the same time that he participated in his first exhibition, Vilela was approached by a friend about doing some illustrations for Aunt Neiva, a well-known spirit healer in the area. Like many others at that time, he had an unfavorable impression of the Valley. “We thought it was just a pack of crazies,” he explained, “that whole thing about the spirits was seen very negatively.” But he needed the money so he agreed to meet Aunt Neiva.

And it was very interesting because she said ‘do you think you can paint these entities for me?’ And I said ‘yes I can.’ I had no idea what she was talking about at that time. But I said, ‘sure, I can do it.’ I hoped I could do it. Because I’ve never shied away from a challenge, I like a challenge. So then she told me to prepare a large canvas, two meters long by one meter wide, because I needed to paint the spiritual planes. And I had absolutely no notion of what she was talking about, I had never heard of the spiritual planes. But I told her that I could paint them. I prepared

the canvas and brought it with me and we started the painting. Seventeen days later the painting, which she named ‘Os Mundinhos’ [the Beloved Worlds], was finished” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

She called it Os Mundinhos because the painting encapsulates all of the fundamentals of our Doctrine,” Vilela explained. “You have all of the dimensions of existence, the spiritual planes, the origins of everything represented in the painting. It is remarkable. And I was able to paint this painting in seventeen days. When I finished it she was very excited and called everyone over to see it and told them ‘finally, the person whom Father White Arrow [Aunt Neiva’s spirit guide] has promised me for 2,000 years has arrived.’ It was me. She had been waiting for 2,000 years for me to help her complete her work. (Hayes 2019).

It was Aunt Neiva’s great dream to have this painting,” Vilela affirmed. “Because it’s one thing for her to say to someone, ‘look, the spiritual world is like this or like that.’ It’s another thing for her to show them. Because by experiencing something visually the human being can understand with much more facility, a person can enter into the image and travel there directly in their mind. (Hayes 2019).

Os Mundinhos was the beginning of a synergistic collaboration between the Vilela and Aunt Neiva that lasted until the latter’s death in 1985.

As the official illustrator of the Doctrine, Vilela worked to transform Aunt Neiva’s on-going spiritual visions into a body of religious artwork that today comprises hundreds  of works in various formats and media. Most of the iconographic representation in the Mother Temple and its surroundings are by Vilela’s hand and include paintings of highly evolved mentor spirits, as well as large (up to nine-meter high), two-dimensional images of figures important within the movement like Jesus Christ and Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the sea. [Image at right] Vilela’s illustrations also adorn doctrinal literature and badges worn on the uniforms worn by members working in the temple. Vilela reproduces and sells his artwork in the form of stickers, post cards, prints, and t-shirts, which can be found in homes, hotels, restaurants, and public places throughout the small town that encircles the Mother Temple.

of works in various formats and media. Most of the iconographic representation in the Mother Temple and its surroundings are by Vilela’s hand and include paintings of highly evolved mentor spirits, as well as large (up to nine-meter high), two-dimensional images of figures important within the movement like Jesus Christ and Yemanjá, the Afro-Brazilian goddess of the sea. [Image at right] Vilela’s illustrations also adorn doctrinal literature and badges worn on the uniforms worn by members working in the temple. Vilela reproduces and sells his artwork in the form of stickers, post cards, prints, and t-shirts, which can be found in homes, hotels, restaurants, and public places throughout the small town that encircles the Mother Temple.

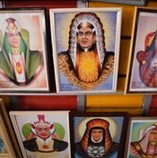

Since Aunt Neiva’s death, Vilela’s artistic production mostly has been devoted to creating commissioned portraits of Valley members’ individual spirit guides, using a form of mediumship he calls psycho-pictography. “Psycho-pictography is a grand fusion of psychic structure, or mediumship ability, with the knowledge of drawing,” he explained. “You have to have the technical ability to transcribe what you are visualizing and you have to have equilibrium so that you don’t lose yourself in the process of registering it.” The process begins when a client tells Vilela the name of their spirit mentor. “Once I have the entity’s name,” he explained, “I become a psychic antenna,” able to open a channel into otherwise invisible realities beyond the physical plane (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

2019). [Image at right]

According to the Doctrine, innumerable “entities of light” work with Valley members as spiritual guides and mentors. Together they form the Indian Space Current, a collective of beings who are so evolutionarily ahead of humans that they have advanced beyond the material plane and exist as pure energy or spirit. “They inhabit dimensions that we cannot even fathom,” Vilela said. “They are voyagers from the stars, creatures who come from another intergalactic system” (Hayes 2015). Because they exist outside of the physical realities of the terrestrial world, these cosmic beings must take on a particular “roupagem,” or material form, in order to interact with humans. These material forms are the subject of Vilela’s portraits. Vilela sees this work as a vital part of his mission and keeps his prices affordable so that his spirit portraits are accessible to all Valley members.

For many years his preferred medium was oil, but in the late 1990s Vilela abandoned oil painting all together and embraced digital technology, developing ways  of using Photoshop to create his portraits. The computer, according to Vilela, gives him “the opportunity to express myself through the utilization of an absolutely innovative and futuristic technology, which offers me tools like: paintbrushes, rulers, masks, erasers, line removers, airbrushes, sixty-two million colors of light, along with textures and much more” (Vilela 2002). Vilela initially encountered resistance among some Valley members, who felt that the digital portraits tended to look alike and suspected that the artist was using a computer program to create them. He scoffs at this notion. “It’s a lack of knowledge, including of the technique, which is a whole thing by itself. You have to know the technique….The machine offers you all of the basic elements to work, but it’s not alive, it doesn’t have a soul, it doesn’t have the faculty of mediumship to materialize an entity on the screen” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

of using Photoshop to create his portraits. The computer, according to Vilela, gives him “the opportunity to express myself through the utilization of an absolutely innovative and futuristic technology, which offers me tools like: paintbrushes, rulers, masks, erasers, line removers, airbrushes, sixty-two million colors of light, along with textures and much more” (Vilela 2002). Vilela initially encountered resistance among some Valley members, who felt that the digital portraits tended to look alike and suspected that the artist was using a computer program to create them. He scoffs at this notion. “It’s a lack of knowledge, including of the technique, which is a whole thing by itself. You have to know the technique….The machine offers you all of the basic elements to work, but it’s not alive, it doesn’t have a soul, it doesn’t have the faculty of mediumship to materialize an entity on the screen” (Hayes 2019). [Image at right]

Since going digital, all of Vilela’s work is created using Photoshop on a desktop computer and printed at his studio steps away from the Mother Temple. There he does a brisk business selling imagery in various formats as well as his  commissioned portraits. [Image at right] Also for sale are numerous books that Vilela has authored on spiritual and other topics.

commissioned portraits. [Image at right] Also for sale are numerous books that Vilela has authored on spiritual and other topics.

Although the computer was “an amazing advance” for Vilela’s artwork, he is now thinking about the next step: “I dream of the time that I will have holography in my hands, working with holography. So I am thinking in 3-D: the idea that you can create an image that can be projected as an electro-magnetic field. Can you imagine arriving at a temple and encountering an image that is three meters in height, made of light, color or energy? Projected as an electro-magnetic field? It will be an enormous advance and I believe that it will be a new era for us….Do you see what I am saying? Suddenly I can create a holographic image and, who knows, maybe even provide a portal, a concrete manifestation of an entity. Which is amazing…today this is fictional for us but it is very important for our evolution.” He concluded: “I believe that I’ve always been a little ahead of my time and I still have a lot to explore” (Hayes 2019).

Vilela’s view of reality, while affirming Valley doctrine, also goes beyond it in certain ways. He has explored his convictions about energy and the extraterrestrial dimensions of existence in a series of self-published books with titles like Spirituality: The Riddle that Psychoanalysis and Neuroscience Can’t Unravel (Espiritualidade: O Enigma que a Psicanálise e a Neurociência não Conseguem Decifrar) (Vilela 2012) and From the First Atom to Eternity (Do Primeiro Átomo à Eternidade) (Vilela, n.d.). He illustrated important events and figures in Brazilian history in a book of digital artworks called Brasil: 502 Anos de Vida, Formas e Cores (Vilela 2002).

With their saturated colors, simple lines, static poses, and frontal perspective, Vilela’s images recall traditions of naïve or folk art and express a style more influenced by science fiction and superheroes than movements in mainstream or contemporary art. [Image at right] Like the Valley of the Dawn itself, Vilela’s work draws freely from esoteric and mass-media sources, mixing elements from Theosophy, Spiritualism and various other religions present in Brazil with ideas and images prevalent in adventure fiction, popular Spiritualist literature, comic books, and television serials. The end result is a kaleidoscopic, yet cohesive universe that blends a contemporary discourse centred on science and technology with an esoteric metaphysics.

With their saturated colors, simple lines, static poses, and frontal perspective, Vilela’s images recall traditions of naïve or folk art and express a style more influenced by science fiction and superheroes than movements in mainstream or contemporary art. [Image at right] Like the Valley of the Dawn itself, Vilela’s work draws freely from esoteric and mass-media sources, mixing elements from Theosophy, Spiritualism and various other religions present in Brazil with ideas and images prevalent in adventure fiction, popular Spiritualist literature, comic books, and television serials. The end result is a kaleidoscopic, yet cohesive universe that blends a contemporary discourse centred on science and technology with an esoteric metaphysics.

IMAGES**

** Clickable enlargements are available for all of the images in this profile.

Image #1: Joaquim Vilela. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #2: Quadro. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #3: Os Mundinhos. Courtesy of Joaquim Vilela.

Image #4: Yemanjá. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #5: João Nunes. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #6: Vilela at Work. Copyright Márcia Alves.

Image #7: Loja. Copyright Kelly E. Hayes.

Image #8: Guides. Copyright Márcia Alves.

REFERENCES

Hayes, Kelly E. 2015. Interview with Joaquim Vilela, July 15. Vale do Amanhecer, Brazil.

Hayes, Kelly E. 2019. “I am a Psychic Antenna: The Art of Joaquim Vilela.” Black Mirror, Elsewhere 2:144-77.

Vilela, Joaquim. n.d. Do Primeiro Átomo à Eternidade. Brasília: Self-published.

Vilela, Joaquim. 2002. Brasil: 502 Anos de Vida, Formas e Cores. Brasília: Self-published.

Vilela, Joaquim. 2012. Espiritualidade: O Enigma que a Psicanálise e a Neurociência não Conseguem Decifrar. Brasília: Self-published.

Post Date:

4 November 2019

Minji Lee

Dr. Minji Lee is a medievalist who specializes in the interactions between mysticism and medicine in the Middle Ages. Her Ph.D. thesis, “Bodies of Medieval Women as Dangerous, Liminal, and Holy: Medical and Religious Representations of Female Bodies in Hildegard of Bingen’s Causae et curae and Scivias” (Rice University 2018), explores how Hildegard of Bingen defended the female sexual/reproductive body as positive in the images of re-creation and salvation against the misogynic medieval and religious culture of her age. After completing a visiting scholarship in the Institute for Medical Humanities, University of Texas Medical Branch, Dr. Lee is now teaching in the Department of Religion and Medical Humanities Program at Montclair State University, New Jersey. Currently, she is researching the ways in which medieval European medical theories and modern Korean folk medicine allow women to maintain their reproductive health and to understand their own bodies in positive ways. Dr. Lee participated in making a Korean independent documentary project, “For Vagina’s Sake (2017)” that demonstrates how Western premodern medicine “diabolized” women’s menstrual bodies. She also volunteered at Reunion Institute to promote public awareness in religion.

Hildegard of Bingen

HILDEGARD OF BINGEN TIMELINE

1098: Hildegard of Bingen was born at Bermersheim, 45 km south of Mainz, Germany.

1106 (?): At the age of eight, Hildegard was put in the care of Jutta of Sponheim, a pious noblewoman.

1112 (November 1): With Jutta, Hildegard entered an enclosure belonging to the Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg, 60 km southwest of Mainz, Germany. At an unknown date, Hildegard took formal vows to become a nun.

1136: Jutta died, and Hildegard was appointed leader of the women’s convent at Disibodenberg. The convent was part of a double monastery, housing both men and women in separate quarters, under the direction of Abbot Burchard.

1141: Having undergone a major mystical experience, and encouraged by the monastery schoolmaster Volmar, Hildegard began writing her first book, Scivias, in which she revealed the visions she had received since childhood.

1147–1148: At the Synod of Trier, Hildegard presented Scivias for papal approval with support from the Disibodenberg Abbot Kuno.

1150: Hildegard established a women’s monastery at Rupertsberg in Bingen, 29 km west of Mainz, Germany. She and eighteen nuns moved to the new location. Abbot Kuno refused to transfer the nuns’ dowries from the convent at Disibodenberg to the new convent at Rupertsberg .

1152: The archbishop of Mainz consecrated the main altar of the church at the Rupertsberg convent.

1155: Kuno, Abbot of Disibodenberg, died after agreeing to provide the nuns at Rupertsberg what was owed them, in a deal brokered by Hildegard. His successor, however, repudiated the agreement.

1158: Arnold, Archbishop of Mainz, granted a charter to secure the nuns’ property from Disibodenberg, and arranged for pastoral and priestly visits to the community of women in the Rupertsberg convent.

1165: Due to the growth of the Rupertsberg convent, Hildegard founded another monastery for women in Eibingen, near Bingen, and became the abbess of two women’s monasteries.

1179 (September 17): Hildegard died at Rupertsberg.

1226: Petition for her canonization was begun by Hildegard’s followers.

1227 (January 27): Pope Gregory IX began the official canonization process for Hildegard.

2012 (May 10): Pope Benedict XVI canonized Hildegard of Bingen, and declared her to be a “Doctor of the Church,” one of only four Catholic women so designated.

BIOGRAPHY

Hildegard of Bingen was born in the diocese of Mainz in the Rhineland of Germany. The oldest record, from Abbot Trithemius of Sponheim, gives Böckelheim as her birthplace, while scholars tend to prefer Bermersheim (Esser 2015). The youngest of seven children, Hildegard began having mystical experiences at an early age. Her wealthy and noble parents, Hildebert and Mechtilde, were faithful Christians, and supported her piety. They sent their devout young daughter, aged eight, to live under the care of a female hermit named Jutta of Disibodenberg (1092–1136), the daughter of Count Stephan of Sponheim. Only six years older than Hildegard, Jutta was an anchoress who lived in an enclosure next to the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg. Here, Hildegard had a chance to study religion, receiving basic knowledge about Christianity. Under Jutta’s guidance, she learned how to read and write in Latin and how to interpret Scripture, especially the Psalms (on Hildegard’s literacy, see Bynum 1990:5). Although her prose required corrections and elaborations, she was one of the few medieval women who could write (Newman 1987:22–25). As her fame grew, Hildegard of Bingen increasingly came into contact with scholars who could teach her, as she reported in her books and letters, although she frequently called herself “uneducated” in her writings, claiming that her knowledge came from God. “Thus the things I write are those that I see and hear in my vision, with no words of my own added. And these are expressed in unpolished Latin, for that is the way I hear them in my vision, since I am not taught in the vision to write the way philosophers do” (Letter to the Monk Guibert 103r, in Hildegard 1998:23).

Alongside her formal education, Hildegard stated that she was continuously having visions and receiving messages from God. She claimed to have started experiencing visions at the age of five, and even maintained that God had given her a vision before she was born, while she was in her mother’s womb. Sometime between 1112 and 1115 the teenager made formal vows to pursue the virginal life in accordance with the Rule of Saint Benedict. Nevertheless, Hildegard kept her visions secret until she went through a major mystical experience in 1141, which led to her conviction that she was God’s messenger as she claimed in the “Declaration” of the Scivias (Hildegard 1990:59–61). She described the vision:

Heaven was opened and a fiery light of exceeding brilliance came and permeated my whole brain, and inflamed my whole heart and my whole breast, not like a burning but like a warming flame, as the sun warms anything its rays touch. And immediately I knew the meaning of the exposition of the Scriptures, namely the Psalter, the Gospel and the other catholic volumes of both the Old and the New Testaments, though I did not have the interpretation of the words of their texts or the division of the syllables or the knowledge of cases or tences (“Declaration” in Scivias, 1990:59).

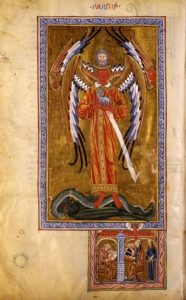

Finally, Hildegard disclosed her holy communications with God to Jutta. After hearing that her protégé was receiving visions, Jutta introduced Hildegard to a monk, Volmar of Disibodenberg (d. 1173), who became her teacher, spiritual guide, and scribe until his death in 1173. [Image at right]

After Jutta’s death in 1136, Hildegard succeeded her as a magistra (spiritual teacher) and as the abbess of the convent at Disibodenberg. At that time double monasteries existed, which maintained separate quarters for men and women under the same roof. Disbodenberg was one such religious house. As the abbess overseeing her female charges, Hildegard moved the convent to Rupertsberg in 1150, seeking more independence from the male community in her administration and spiritual leadership. When the abbot of Disibodenberg opposed Hildegard’s plans for a separate convent, she pursued the request anyway, saying that it was God’s command. She then fell ill, and insisted that her sickness had religious significance since it was caused by “male priests’ and leaders’” disobedience to God’s will (Newman 1987:27–29). Eventually the abbot had to withdraw his objection and accept Hildegard’s decision.

After the convent was successfully relocated to Rupertsberg, Hildegard established the rules and secured financial resources. She adapted the architectural space and liturgical elements to benefit her leadership and her nuns’ autonomy in religious life. This granted more independence than sharing the same place with male monks, which resulted in being ruled by male authorities. In this new monastery, Hildegard successfully ran the women’s religious community by establishing monastic disciplines as well as financial security with her teaching, preaching, and writing on God’s words. Therefore, her relocation of the women’s monastery was “for the sake of the salvation of our souls and our concern for the strict observance of the Rule” (Letter to the Congregation of Nuns 195r, in Hildegard 1994:170).

Furthermore, Hildegard wished to find a place where her nuns could practice devotion with proper rules and liturgies. She wanted the nuns to have their independence in a new monastery so they could better observe the Benedictine Rule (Petty 2014:140). Hildegard composed songs for liturgies and developed dramas, probably as a way of inviting, and even encouraging, the nuns to share her transcendent experiences by acting in her mystical plays (Newman 1990:13).

This was just one of the many ways in which Hildegard was able to use her spiritual experiences of pain and her visions from God. Other instances in which she utilized mystical insights were when she raised her voice against church authorities (including the pope, secular leaders, and the German emperor) when she felt that their claims went against God’s wishes (Flanagan 1998:6). She believed that her frequent sickness had given her a “propensity for visions,” and so took her pain for a blessing (Newman 1990:11–12).

Despite her illnesses, Hildegard enjoyed a long and active life until she died at the age of eighty-one. When she was about sixty years-old, she even undertook a preaching tour near the Main River, the largest tributary into the Rhine. Hildegard of Bingen died on September 17, 1179, and she was first buried in the graveyard of the Disbodenberg convent. In 1642, her remains were moved and buried in the Eibingen parish church. Despite her popularity and authority, she was not canonized until 2012, although she had already begun to be treated like a saint in her own lifetime.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

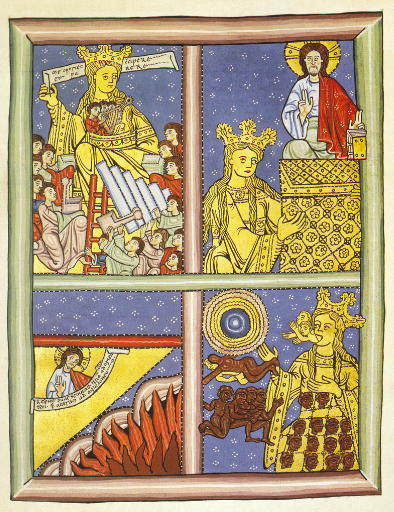

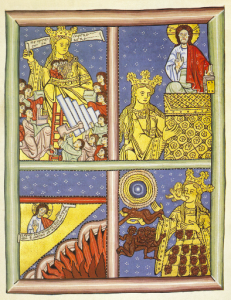

Hildegard of Bingen believed she received direct interpretations and hidden knowledge of scripture from God. Her major trilogy of religious knowledge, which she believed originated from God, included: the Scivias (Knowing the Ways of God, 1141–1151) and the Liber vitae meritorum (Book of Life’s Merits, 1158–1163). In the Liber vitae meritorum, Hildegard introduced thirty-five pairs of the virtues and vices of human  beings, ending with a chapter on purgatory and hell. People were to be judged by how they behaved. The last volume of the trilogy was the Liber divinorum operum (Book of Divine Works, 1163–1173/74). [Image at right] In this work, Hildegard presented herself as a prophet, offering ten visions in three parts. This final volume contains her understanding of cosmology, rooted in her treatment of the close relationships between the worldly elements, human bodies, human souls, and God’s intentions. In analyzing them, Hildegard argued that everything was created by God’s will with proper reason. Even when people make mistakes and commit sins, their nature knows what is right and wrong, and God’s will has the power to bring people back to goodness. These books all present Hildegard’s optimistic views on the world and human beings.

beings, ending with a chapter on purgatory and hell. People were to be judged by how they behaved. The last volume of the trilogy was the Liber divinorum operum (Book of Divine Works, 1163–1173/74). [Image at right] In this work, Hildegard presented herself as a prophet, offering ten visions in three parts. This final volume contains her understanding of cosmology, rooted in her treatment of the close relationships between the worldly elements, human bodies, human souls, and God’s intentions. In analyzing them, Hildegard argued that everything was created by God’s will with proper reason. Even when people make mistakes and commit sins, their nature knows what is right and wrong, and God’s will has the power to bring people back to goodness. These books all present Hildegard’s optimistic views on the world and human beings.

The Scivias is considered Hildegard’s most important book, which shows her theology and visions. In it she revealed her conviction that she was God’s messenger: “The person [Hildegard] whom I [God] have chosen and whom I have miraculously stricken as I willed, I have placed among great wonders, beyond the measure of the ancient people who say in Me many secrets” (Hildegard 1990:59–61). Although she claimed that she had been receiving visions and having mystical experiences from before her birth, it was in 1141 that she had a life-changing mystical event. In this vision, God called Hildegard his messenger and ordered her to write down the holy secrets he revealed to her. It took ten years for her to finish this book with the help of Volmar, the school master at Disibodenberg, and later her friend and companion Richardis von Stade (d. 1152). Volmar and the Cistercian mystic Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153) helped Hildegard to obtain an approval and blessing from Pope Eugenius III (p. 1145–1153) to continue her writing. Scivias is the product of her transformative vision that made Hildegard identify herself as a speaker of God.

The Scivias consists of a sequence of Hildegard’s visions and their interpretations, which are often voiced as if God were speaking. Addressed to a clerical and monastic audience, the Scivias consists of three books in which Hildegard’s visionary witness is accompanied by God’s explanatory voice. Each chapter is arranged to begin with a description of what Hildegard saw in her vision, followed by the exegetical explanation of it that she reported she had received directly from God. The first book discusses God’s creation of the world; the second book the redemption of the world through Christ with sacraments such as baptism and the Eucharist; and the third the “sanctification” of the world, by which she meant how God’s dispensation will be fulfilled through history and morality. Together, these three books can be seen as representing the past, present, and future of God’s works, and the role of the church in them, reminding readers of the doctrine of the Trinity.

Each book contains between six and thirteen visions, and each vision starts with Hildegard’s description of what she saw or heard from heaven. First, Hildegard described each part of her vision in detail. Then, speaking in God’s voice, she drew out the details of the vision with frequent references to Scripture, morality, the priesthood, humanity, and various other topics. She often alternated between her own voice and that of God, which sometimes makes it difficult to distinguish whether Hildegard or God is speaking at any given moment.

An analysis of Hildegard’s exegesis, visions, letters, and other writing reveals a pro-female (though not proto-feminist) anthropology, ecclesiology, and biology. An optimistic and even up-beat theology emerges in her thought. For example, when Hildegard analyzed the fall of Adam and Eve in her medical book Causae et curae (Causes and Cures, an abbreviation of Liber compositae medicinae aegritudinum causis, signis atque curis, 1150s?), she maintained that human beings did not lose God’s power and knowledge (Causae et curae Lib. II, in Hildegard 2008). Human beings retained this sacred knowing, which eventually will enable women and men to return to a pristine state to be saved by God. Hildegard agreed with many other medieval theologians that the body of the first human beings, Eve and Adam, became degraded and began to require reproduction as a result of original sin and losing eternal life (Causae et curae Lib. II, Hildegard 2008). However, Hildegard saw that God’s power, which created Adam, still remains in the bodies of women and is at work when they give birth to babies. In this way, even after human beings sinned against God, they still could benefit from God’s creative power present in women’s bodies (she does not mention men’s bodies). At the same time, human beings have simply forgotten that they have God’s knowing in them; it will flourish again when they have salvation through the Savior.

And thus Man, having been delivered, shines in God, and God in Man; Man, having community in God, has in Heaven more radiant brightness than he had before. This would not have been so if the Son of God had not put on flesh, for if Man had remained in Paradise, the Son of God would not have suffered on the cross. But when Man was deceived by the wily serpent, God was touched by true mercy and ordained that His Only-Begotten would become incarnate in the most pure Virgin. And thus after Man’s ruin many shining virtues were lifted up in Heaven, like humility, the queen of virtues, which flowered in the virgin birth, and other virtues, which lead God’s elect to the heavenly places (Scivias 1.2.31, in Hildegard 1990:87–88).

Human beings will then be reestablished as they once were in paradise. Nothing is ever lost in people. Salvation is not something alien or extremely difficult to achieve. Even when people sin, they can come back to Ecclesia (that is, the church) to do penance, thereby cleansing sin from their bodies and souls.

In Vision Three in Book Two of the Scivias, Hildegard mystically saw Ecclesia as a woman wearing white clothes. Whereas it is very common in traditional exegesis to depict the church as a female and the church’s redemptive role as motherly, Hildegard vividly described the vivid image of Ecclesia giving birth.[Image at right]

And this I saw the image of a woman as large as a great city, with a wonderful crown on her head and arms from which a splendor hung like sleeves, shining from Heaven to earth. Her womb was pierced like a net with many openings, with a huge multitude of people running in and out. She had no legs or feet, but stood balanced on her womb in front of the altar that stands before the eyes of God, embracing it with her outstretched hands and gazing sharply with her eyes throughout all of Heaven.

And that image spreads out its splendor like a garment, saying, “I must conceive and give birth!”

Then I saw black children moving in the air near the ground like fishes in water, and they entered the womb of the image through the openings that pierced it. But she groaned, drawing them upward to her head, and they went out by her mouth, while she remained untouched. And behold, that serene light with her figure of a man in it, blazing with a glowing fire, which I had seen in my previous vision, again appeared to me, and stripped the black skin off each of them and threw it away; and it clothed each of them in a pure white garment and opened to them the serene light (Scivias II.3, in Hildegard 1990:169).

According to this vision, Ecclesia is having an inverted version of childbirth to give new life to sinful souls that enter the lower part of Ecclesia through her womb. They are cleaned in the body of Ecclesia, and then go out from the Ecclesia’s mouth as purified. In this passage, Hildegard clearly juxtaposes women’s childbirth and Ecclesia’s redemption as well as women’s reproduction and Ecclesia’s re-creation of human beings.

Hildegard’s writings show relatively more compassion to women in general than do texts by either female or male contemporaries. She presents the woman’s body as less contaminated by original sin, which is unusual in medieval theology and medicine. For example, Thomas Aquinas devalued the woman’s reproductive process so much that he argued that in the moment of Jesus’ conception, the Holy Spirit was entirely separated from the Virgin Mary’s reproductive parts and blood. In other words, the blood used in the conception of Christ never visited Mary’s lower regions. “For then the blood was brought together in the Virgin’s womb and fashioned into a child by the operation of the Holy Spirit. And so Christ’s body is said to be formed of the most chaste and purest blood of the Virgin” (Summa Theologiae IIIa. a.31 q.6: 29, in Thomas Aquinas 2006).

Hildegard appreciated women’s bodies as more purifying and more able to be purified. According to the creation narrative in Genesis 2, Adam was made from dirt whereas Eve was produced from Adam’s rib by God; therefore Hildegard concluded that Adam and male descendants are harder, more rigid, and difficult to change compared to women, both physically and psychologically. Because of this hardness in Adam, his body deteriorated so much that it became polluted, while Eve’s body began to have flows, in other words, menstruation. Hildegard further insisted that it was better that Eve, the woman, committed the first sin because humankind might have a better chance to recover her pure body and mind. If Adam had brought the sin first, his hardness would have made it difficult for his descendants to repent and return to God.

At the same time, Hildegard argued that the female body has the power to nullify the man’s deadly nature, which inevitably originated from God’s power to make Adam; women, however, could overcome men’s noxious semen and create children. In Causae et curae Hildegard explained that during intercourse and conception the woman’s foam tempers the polluted nature of semen, kindling it and converting it into an appropriate state so it can be generated as a fetus.

And her blood is stirred by the man’s love and she emits something like foam, but more bloody than white, toward the man’s semen; the foam conjoins itself to it (i.e. the semen), and strengthens it and makes it warm and bloody; for after it falls into its place and lies there, it becomes cool. And for a long time it is just like venomous foam until fire, namely heat, warms it up and until air, namely breath, dries it out, and until water, namely flow, sends pure moisture to it, and until earth, namely skin, constrains it. And thus it will be bloody—i.e. it is not entirely blood, but just mixed with a little blood. And the four humors, which a human being draws from the four elements, remain around the same semen moderately and temperately until the flesh is kind of coagulated and firmed up, so that the form of a human being can be figured in it (Causae et Curae, Lib. II in Hildegard 2008:51–52).

Hildegard thus asserted that all four elements (earth, water, air, and fire) and all four humors generated from them (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile, as identified in Greek medicine) of the female body work together to generate a fetus by giving semen appropriate qualities. Again, the interesting point is that in Hildegard’s understanding the woman’s body neutralizes the poisonous character of the man’s semen, emphasizing the positive power of the woman’s body. This contrasts with the majority of folk and Christian medicine that regarded the woman’s body as fatally polluting due to blood from menstruation and childbirth.

Hildegard also emphasized the abiding potency of God present and working in women during the process of childbirth. During childbirth, the eternal power of God is awakened and stirring the mother’s body so that a baby can be born out of her body, just as Adam was produced by God.

With childbirth imminent, the vessel in which the infant had been enclosed, is split. The power of eternity, which brought forth Eve from Adam’s side, arriving soon, is present and overturns every corner of the dwelling place of the woman’s body. All the joints of the woman’s body become involved with that force and they assist it and open themselves. They hold themselves while the infant emerges, and then resume their former arrangement. While the infant emerges, his soul feels the power of eternity, and is happy (Causes and Cures, Lib. II, in Hildegard 2008:56).

These descriptions from Hildegard of Bingen’s medical and theological writings show her appreciation of the beneficial power in the woman’s body.

Of course, Hildegard was not arguing for women’s equality. She continued to believe that women were weaker than men and that women could not become priests. She kept insisting that she was nothing but an uneducated woman. She nevertheless transformed these medieval gender stereotypes into views more favorable to women. Because the woman’s body was weaker, it made it easier to be corrected and to make human salvation less difficult. Woman could not become priests, because their reproductive duties were strongly tied them but since men were not fulfilling their duties of priesthood, Hildegard had to become a messenger of God instead of men. She argued that if women have the virginal life, they could be like priests in giving people new life as a spiritual reproduction although she was still against women taking priestly office (Clark 2002:14–15). Even when Hildegard did not support women’s equality, she still suggested that the woman’s body could be represented and understood as positive, purifying, and re-creative. She expressed this in numerous spiritual and medical writings.

As we have seen, Hildegard’s Scivias presents Ecclesia’s salvific process replicated in the woman’s reproductive process. In her vision, Ecclesia, having the female body, draws the souls through her womb and gives birth to them after cleansing their sins. This power in the woman’s reproductive body is also related to Hildegard’s cosmological view that the power of giving a life (originated from God is present in every creature of God, and makes the whole universe move.

This power of making life was named viriditas by Hildegard of Bingen through her various writings. Although there is no exact equivalent word in English, Hildegard called it “greening power.” Viriditas is the capacity within plants to absorb natural elements and generate them into green leaves. She described this greening power as dominating in summer, in contrast with the dryness prevailing in winter (Book of Divine Works in Hildegard 2018:169). Viriditas could actually be present in any creation of God. For example, according to Hildegard’s Physica (Natural Science, ca. 1150), the gem emerald possesses such viriditas that it can heal people by being placed upon their bodies (Hildegard 1998:138).

Viriditas is not only present in plants, but also in all creatures of God. Thus, Hildegard’s theology contributed to a creation-centered spirituality. If a person is full of viriditas, it means she or he judges what is right and wrong and follows the good will of God. If the person lacks viriditas, they do not follow the soul’s right discernment between good and evil. Just as a plant could bear fruits only by having this greening power, people cannot have good outcome without viriditas (Book of Divine Works in Hildegard 2018:196).

By relating viriditas to menstruation, Hildegard established herself as a kind of medieval medical expert knowledgeable about women’s health and reproduction.

The stream of a woman’s menstrual period is her life-giving vital force and her exuberant vigor. This sprouts into offspring, as a tree with its vital force [viriditas] sprouts and flowers, producing leaves and fruits. So a woman, from the vital force [viriditas] of the menstrual blood, produces flowers and leaves in the fruit of her womb (Causae et curae Liber II, in Hildegard 2008:87).

Hildegard’s concept of viriditas is not only a natural scientific idea but also a theological construct because she described it as the power given to humankind by God. God used this greening power to create the whole world. “In the beginning, all creation was verdant, / in the middle, flowers blossomed; / later, the viriditas came down” (Ordo Virtutum 481vb, in Hildegard 2007:253–54). After Adam and Eve committed the original sin, this greening power seemed to be repressed in their bodies (Marder 2019:138), but the Virgin Mary revivified viriditas by becoming viridissima virga, “the very green branch,” by herself, bringing back salvation and revitalization to human beings (“Song to the Virgin 19.1” in Symphonia, in Hildegard 1998:127). Viriditas is the vital power of greening in Hildegard’s natural science; at the same time, it is her understanding of salvation and the restoration of humanity in her theology.

Viriditas, the greening power enlivening creatures of God, expressed in her visionary writings, also appears in Hildegard’s music, revealing how important Hildegard considered this idea. The following was the responsory sung by her nuns, which originated from her book Scivias III.13.7b.

O. nobilissima viriditas Responsory for Virgins

R. noblest green viridity,

you’re rooted in the sun

and in the clear

bright calm

you shine within a wheel

no earthly excellence

can comprehend:R. You are surrounded by

the embraces of the service,

the ministries divine.V. As morning’s dawn you blush,

as sunny flame you burn (Responsory for Virgins).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Hildegard of Bingen encouraged women’s participation in religious services and dramas. Although her religious life was restricted to the convent, her influence extended outwards to both women and men in many ways. By composing liturgical songs and mystery plays that featured women performers, she especially encouraged women’s involvement in church liturgy. In this way, Hildegard shared what she learned from others (and God’s direct instruction to her) with the nuns and other female colleagues. For example, her play, the Ordo virtutum (Order of the Virtues), the first surviving morality play, which was written in 1151, depicts a soul’s struggle between sin and virtue and presents Hildegard’s style of exegesis.

At the same time, Hildegard used homilies to deliver her understanding of scripture to the women in her care as abbess. Using these means, and supported by her theological knowledge and experience as a woman, Hildegard created gateways for religious women’s more active participation in liturgy. In particular, her music and plays were more accessible to her nuns once she moved her abbey to Rupertsberg and separated from the double monastery at Disibodenberg.

Although Hildegard of Bingen did not think of herself as a composer, she composed seventy-seven songs, mainly for practical use by the nuns in her convent. Hildegard treated music and singing as an essential part of the monastic life following the rule of Saint Benedict. Many of her songs were antiphons, accompanying the psalm reading or liturgies. Others are responsory, sequences, and hymns, which could be used for various liturgies. Although her music is highly religious, it seems that Hildegard must have been exposed to non-religious musical components as she mentioned “a lyre” in the Liber vitae meritorum (White 1998:14).

Hildegard’s music concretely conveys her theological views. In fact, her visions were mostly sung to musical accompaniment. She frequently emphasized what she saw and heard. Often, Hildegard reported that she heard music in her visions, demonstrating the significance of the musical component in her religious life. In the last vision in the Scivias, Hildegard says, “Then I saw the lucent sky, in which I heard different kinds of music, marvelously embodying all the meanings I had heard before” (Scivias, in Hildegard 1990:525). Then, she wrote down nine songs recording what she claimed to have heard in her visions. Furthermore, they embodied her mystical experiences, providing meaning through music. In other words, music was the ultimate medium of her visions.

LEADERSHIP

Hildegard of Bingen was an unusual woman in that she was a strong and able leader who enjoyed fame in her own lifetime. She not only supervised nuns in two convents, but she also influenced male authorities. Living in a time when women were forbidden to teach or preach, Hildegard was able to use holy visions and spiritual illness as sources of spiritual and secular influence. She corresponded with many people, men as well as women, to deliver her message. At the same time, Hildegard cared for her charges through her teaching, writing, and administration.

Hildegard might have been considered a threat to male authorities in the church due to her direct visions from God; she certainly made broad claims to authority as God’s messenger. In fact, she explicitly criticized male authorities by saying that these men with power did not do what God asked them to do; and that was why she called her contemporary time an “effeminate age” (Newman 1985:174). When men were not accomplishing their duties, in her opinion, it was time for women to do the job. Thus, Hildegard claimed to be the proper messenger of God since men were not fulfilling God’s orders; she advocated for her works of preaching and teaching, which were strongly prohibited by the church for women (Newman 1985:175).

Hildegard’s theology and belief in her God-given visionary authority challenged the medieval view that women, as the weaker sex, were susceptible to evil and the devil (Caciola, 2015:27–28).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Like other medieval female saints, Hildegard faced a number of issues both in the Catholic Church and in secular society. Even after she was publicly accepted as a God’s messenger by Pope Eugenius III when he approved her Scivias in 1148, she was sometimes involved with theological or political conflicts with other theologians or the emperor, Frederick Barbarossa (1122–1190). For example, Hildegard was not afraid to rebuke Frederick Barbarossa regarding the German papal schism although he was the imperial protector of her Rupertsberg monastery. She called him an infant and a madman, threatening him with God’s voices although he kept his promise to protect her monastery (Newman 1987:13).

Hildegard faced serious objections from the monks of Disibodenberg when she wanted to move the monastery for women. Although Abbott Kuno tried to interfere with her plan by refusing to transfer the nuns’ dowries, she persisted, declaring that her intention was God’s intention, and insisting that her physical illness was caused by the monks’ hard hearts as a punishment of God until they yielded and changed their opinion (Newman 1985:175). Hildegard was not afraid to hold firm to her opinion in the face of church authorities’ opposition or displeasure, because she was convinced that she was a vessel to deliver God’s words. Hildegard and her women’s monastery at Rupertsberg even received an interdict (that is, a prohibition on participating in church rites) from prelates in Mainz because the nuns did not obey an order from church officials in the Mainz diocese, although it was quickly removed. This case shows that Hildegard of Bingen was not afraid to raise her voice against male church authorities in the Middle Ages when women were subjected to men and mystics were also subjected to ecclesiastical censure. She strongly pursued her goals while holding to her conviction that she was doing the right thing.

These struggles show that Hildegard of Bingen asserted what she believed was her divinely given spiritual authority to meet challenges to her actions on the part of male authorities in political and religious conflicts.

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Hildegard of Bingen’s life and productivity have been extensively studied and researched. Like other women of her era, she began to attract scholarly attention due to the emergence of feminist studies in history in the twentieth century. Afterwards, her works on theology as well as secular topics were translated and analyzed in many books and articles. To gain a complete understanding of this medieval mystic, it would be necessary to read her works in a holistic way that encompasses her religious, physiological, cosmological, medical, astronomical, and musical theories.

Although Hildegard of Bingen was widely welcomed by modern feminist scholars as a woman who was intelligent and powerful in the Middle Ages, it is also true that she accepted and perpetuated the gender stereotypes of her peers. Although she stated that women’s bodies purified men’s semen and contained God’s power in childbirth, in her medical and theological writings, she insisted that women were weaker than men and they were subject to men. She also argued that women should not become priests, although she believed that some of women’s roles were similar to priestly duties. While she said that women should not approach an altar, she also wrote that women had a more direct relation to the Holy Spirit because they could have Jesus as their husband. Is Hildegard of Bingen’s theology woman-repressing or woman-empowering? It shows how important it is for modern readers to understand her theology within its medieval context.

Hildegard was not the only case in which a woman was called “teacher” in the Middle Ages, but she was exceptionally famous and respected for her spiritual knowledge during her lifetime. She was unusual among medieval religious women, because she could read and write by herself, even if she still needed to accept male guidance. Having joined her mentor Jutta in the religious life during her childhood, Hildegard began her studies quite early. Even when she did not mention other theologians by name in her books, her writings show that she must have been trained in theology by Jutta, by Volmar, and through her independent study of books in the monastery library. Moreover, her correspondence with contemporary theologians and male elites indicates that she was sufficiently educated to make effective theological arguments. Equipped with physical and visionary forms of religious experience, and an education, Hildegard was able to live up to her renowned status, which she had created by presenting herself as a prophet with an authoritative voice in her spiritual writings, and by comparing herself to the biblical prophets such as Moses and John the Evangelist (Newman 1999:19–24). Her own followers compared her to female prophets in the Bible, such as Deborah, Huldah, Hannah the mother of Samuel, and Elizabeth the mother of John the Baptist (Letter to Hildegard 75, Newman 1987:27).

The fact that Hildegard wrote about medicine and the natural sciences, as well as described her religious visions and spiritual understanding, also makes her different from many women of her time. In her books, she brought the spiritual knowledge that she claimed to have received from God to bear on secular subjects in addition to religious ones. She wrote on medicine, mineralogy, musicology, and natural science, among other topics. For her, these “secular” disciplines could belong to theology because they explained God’s order in a micro-macro cosmology. Her vivid illustrations of the human as the micro version of the macro cosmos penetrate all her writings.

Her writings assert that she was a legitimate messenger of God, even though a woman. Granted, she was not totally free from the patriarchal culture of the Catholic Church and medicine; but using femininity to signify weakness (Newman 1987:88), as a teacher, she eventually turned her weaker sex into an advantage. When women were not allowed to preach or to teach theology, Hildegard articulated a justification appropriate for her time about why she could teach: men abandoned their privileged duty to teach God’s words to people and they had lost viriditas, so now women should become “manly” and take over their job (Liber divinorum operum 3.8.5, in Hildegard 2018:430–31). In her medical writings, Hildegard argued that women’s weaker, softer body, which lacked semen, kept women safe from the poisonous degradation of semen, whereas Adam, with the stronger body, had semen, which was degrading and polluting (Cause et curae, Hildegard 2009:140). This view is quite different from that of her contemporaries, who claimed that women should be subjected to men in the Church because of their weaker bodies, their lack of semen, and their monthly pollution through menstruation. Hildegard made women’s weaknesses into strengths, and wrote that women were more flexible because they did not have polluted semen and thus were not stubborn in either mind or body. She claimed to receive all religious and secular knowledge from God, pointing out that she was such a simple and unlearnt woman that she could not possibly have made up or fabricated these ideas on her own (Scivias “Declaration,” Hildegard 1990:56).

Relying, then, on the legitimacy of divinely given visions, Hildegard of Bingen advocated for women in the monasteries, and developed a female-centered science to explain gender differences. Her concept of viriditas and creation-centered spirituality has greatly influenced both Christian ecofeminists and other feminist theologians. For example, Mary Judith Ress appreciated Hildegard’s viriditas as a bio-spirituality to remind readers that all creations are closely linked to God in this greening power (2008:385). Although Hildegard’s cosmology can be seen as anthropocentric (that human beings represent the center of God’s creation) her micro/macro-cosmism that emphasizes human beings’ links and responsibilities to all of God’s creations is appreciated by feminist theologians (Maskulak 2010:46–47). Along with Hildegard’s concept of viriditas, Jane Duran argues that Hildegard’s ontology is also highly gynocentric. She uses very feminine conceptions, such as connectedness and relatedness, as opposed to men’s normative and distanced qualities. In doing so, she presents personified individual virtues that exist in women as well as men (Duran 2014:158–59, 165).

IMAGES

Image #1: “Frontispiece of Scivias, showing Hildegard receiving a vision, dictating to Volmar, and sketching on a wax tablet” from a miniature of Rupertsberg Codex of des Liver Scivias Facsimile, Fol. 1r.