CHAPEL CARS TIMELINE

1880s: The Russian Orthodox Church supported a number of chapel cars along the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

1890 (April 28): Bishop William David Walker contracted with the Pullman Palace Car Company to build America’s first cathedral car.

1890 (November): Bishop Walker left Chicago in “Church of the Advent,” the Cathedral Car of North Dakota, headed for Fargo, North Dakota.

1891: The first chapel car of Northern Michigan was likely in use with the Episcopal bishop, G. Mott Williams.

1891 (May 23): “Evangel,” the first Baptist chapel car, was dedicated in Cincinnati, Ohio.

1893 (May 24): “Emmanuel,” the second car built by the Baptists, was dedicated in Denver, Colorado.

1894 (May 25): The Baptist chapel car, “Glad Tidings,” was dedicated in Saratoga Springs, New York.

1895: The second chapel car of Northern Michigan was in operation, serving the Episcopal Church.

1895 (June 1): “Good Will,” the Baptist car sent to serve the people of Texas, was dedicated in Saratoga Springs, New York.

1898 (May 21): “Messenger of Peace,” the fifth Baptist chapel car to be built, was dedicated in New York. Messenger of Peace was referred to as “the Ladies’ Car” because Baptist women from across the country raised the funds necessary for its construction.

1900 (May 27): “Herald of Hope” was dedicated in Detroit, Michigan. This car was also known as “The Young Men’s Car” because the young Baptist men of Detroit’s Woodward Avenue Church raised the first thousand dollars for its construction.

1904 (April 30 – 1904 (December 1): Messenger of Peace was on display at the World’s Fair in St. Louis. Father Francis Clement Kelley visited the chapel car and subsequently took the idea to the Catholic Extension Society.

1907 (June 16): “St. Anthony, the first Catholic chapel car, was officially blessed in Chicago, Illinois.

1912 (June 30): “St. Peter”, the second of the Catholic chapel cars, was dedicated in Dayton, Ohio. This chapel car, unlike its predecessor, St. Anthony, was constructed of steel.

1915 (March 14): The last of the Catholic chapel cars, “St. Paul,” was dedicated in New Orleans, Louisiana.

1915 (May 21): “Grace,” donated to the Baptists by the Conway family in their daughter’s memory, was dedicated in Los Angeles, California. Grace was the last Baptist chapel car to be built, as well as the only Baptist chapel car to be constructed of steel.

1962: St. Paul, the last chapel car to remain mobile, ended its service in Montana.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

During the last half of the nineteenth century, established religious traditions in several nations developed innovative means of reaching new settlement populations. Beginning a century earlier, religious missionaries in America who came to be called “circuit riders” had sought out dispersed and isolated frontier populations on horseback to spread the gospel. Methodists were particularly noted as circuit riders. The advent of railroads offered a new means of accomplishing this missionizing goal, chapel cars. Particularly for nations with vast geographic areas being settled, such as the United States, Australia, and Russia, chapel cars proved to be a viable option for a number of years. The  Russian Orthodox Church operated five train cars in the 1880s along the Trans-Caspian and Trans-Siberian railroads. [Image at right] These cars carried two priests per car who would administer the sacraments each day as the trains traveled the rail lines (Walker 1896:577; bmberry 2019; Miklós 2014).

Russian Orthodox Church operated five train cars in the 1880s along the Trans-Caspian and Trans-Siberian railroads. [Image at right] These cars carried two priests per car who would administer the sacraments each day as the trains traveled the rail lines (Walker 1896:577; bmberry 2019; Miklós 2014).

Elsewhere, It is has been reported that Pope Pius IX used a specially fitted railway car that allowed him to administer sacraments when traveling through the Papal States (Kelley 1922:69). Additionally, chapel cars were said to have been used for missionary service in some areas of Africa, although information on these chapel cars does not go further than their mention in mission publications (Walker 1896:577). The best documented history of chapel cars is in the United States.

The beginnings of a national railroad system began in the 1860s with the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad, and as the railroad network expanded, new communities developed. These frontier communities were often small, with few inhabitants and limited initial infrastructure. When people moved to the frontier, they had to decide what organizational investments to make. The inhabitants of these towns tended to prioritize investing in the economy, rather than religion or culture (Lacitis 2012). However, as towns became more established and their populations rose, markers of settled life, such as businesses and schoolhouses, began to appear with more frequency. By the 1890s, the majority of the United States’ West was deemed “settled,” but remained “frontier region” for the Episcopal, Baptist, and Catholic Churches (Taylor and Taylor 1999:18). These different churches were involved in missionary work across the frontier, but the dispersion of the population made this work difficult and time-consuming.  Chapel cars offered a new means of reaching distant and diverse population settlements.

Chapel cars offered a new means of reaching distant and diverse population settlements.

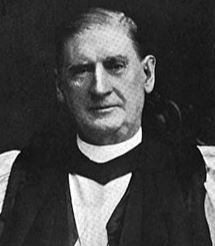

David Walker, [Image at right] who was the first to produce a chapel car and introduce it into service. As bishop of North Dakota, Walker oversaw an expansive territory with few established churches or congregations, despite the prevalence of small towns which had sprung up along the rail lines. On a trip to Russia, Walker saw the Orthodox chapel cars and brought the idea to other Episcopalians as a solution to the unique situation of missionizing in the North Dakota territory. A church on wheels would allow religious leaders to provide services to those in the newly settled towns without having to invest the capital needed to establish physical churches (Taylor and Taylor 1999:13-14, 18).

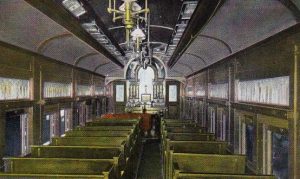

In 1890, after raising the necessary funds, Walker contracted with the Pullman Palace Car Company to build the first American chapel car. This car, “Church of the Advent,” the Cathedral Car of North Dakota, was sixty feet long with an area for religious services to be held and a small living apartment for Bishop Walker. The car was equipped with portable chairs and the features that Bishop Walker  would need to conduct religious services, such as an altar, a lectern, a font, and an organ. Many of the car’s items and furnishings were given by Episcopalians across the county (Taylor and Taylor 1999:18-20). [Image at right]

would need to conduct religious services, such as an altar, a lectern, a font, and an organ. Many of the car’s items and furnishings were given by Episcopalians across the county (Taylor and Taylor 1999:18-20). [Image at right]

Bishop Walker’s plan was to travel the rail lines, sending news of his upcoming visit days before he arrived at a town. Upon arriving at a destination, the cathedral car would be moved to a sidetrack where it would stay for a period of time, allowing Bishop Walker to offer religious services to the population in the area. When Walker was ready to move on to another town, the cathedral car would be picked up by another train, and the process would continue. Walker’s chapel car plan proved to be a success. In the first three months that the car was in service, thirteen stops were made, with the car often filling to capacity during services (Taylor and Taylor 1999:20-21).

Walker continued his success as he traveled across the North Dakota territory. Along with providing religious services, distributing literature, confirming members to the Church, and establishing missions, Walker was responsible for caring for the cathedral car. He discovered that the cathedral car appealed not only to Episcopalians but also to those of other faiths and those without religious affiliations. The cathedral car sparked curiosity and drew in visitors when it arrived at a town, with people traveling from neighboring areas to attend services (Taylor and Taylor 1999:21). With the cathedral car, Walker had found a solution to reaching those in the expanse of the North Dakota frontier and getting them involved in Episcopal services.

Not long after Church of the Advent began its travels across the North Dakota frontier, the first Baptist chapel car, Evangel, [Image at right] entered service. The Baptist chapel car had come about after two brothers, Wayland and Colgate Hoyt, traveled via train across the Western frontier. Wayland Hoyt, a pastor, was surprised by the paucity of churches he saw as the train passed by the numerous small communities that had emerged alongside the rail lines. Wayland felt that the railroad companies could build a missionary car that would serve the people of these churchless communities. At the time, Colgate Hoyt was vice president of the Northern Pacific Railroad and had made a name for himself in the railroad business. After his brother pitched the idea of a chapel car, Colgate Hoyt organized a chapel car syndicate that included John D. Rockefeller, Charles L. Colby, and James B. Colgate. The men who comprised the syndicate saw the potential benefits of a chapel car, both as businessmen with desire to see railroad communities gain stability and as Baptists who felt moral good could come from this new approach to missionary service. Wayland Hoyt called on a Minnesota Sunday school missionary, Boston Smith, to sketch a plan for a chapel car that would include living quarters for a missionary and a place to conduct services. This sketch was turned into reality by the Barney & Smith Car Company (Taylor and Taylor 1999:29-34).

This first Baptist chapel car, Evangel, was dedicated in Cincinnati, Ohio on May 23, 1891. The car was equipped with pews (featuring built-in hymnal racks), a pump organ, a brass lectern, and other features common in Baptist churches. A number of items aboard the chapel car had been donated by Baptists across the country. The living apartment, similar to that of the Church of the Advent, contained a sink, stove, desk, shelving for books, and an upper and lower bed (Taylor and Taylor 1999:37-38).

Boston Smith was the first missionary to serve on Evangel, and because an assistant had not been found for the start of Evangel’s journey, Smith’s twelve-year-old daughter accompanied him and served as the car’s organist. As Smith traveled on Evangel, flyers were posted announcing the chapel car’s arrival and Christian literature was handed out along the route. Circulars were also printed with a picture of the chapel car and information about the mission goals during the chapel car’s stops. These techniques worked to draw in crowds. For instance, on Sunday at Evangel’s first stop in Brainerd, Minnesota, six meetings were held, each one with overflowing crowds. Smith reported an average of two meetings each day, and from five to seven services every Sunday. Speaking to the success of Smith and Evangel, within a month aboard the chapel car, Smith had received invitations that would have kept the car booked for two years. In December 1891, Smith turned Evangel over to the first appointed missionaries, the Wheelers. The Wheelers would continue Evangel’s success in Oregon and Washington until 1894 when the Evangel began service in the Southeast (Smith 1896:5-8; Taylor and Taylor 1999:39-47).

In the period from 1891 to 1900, seven more chapel cars were introduced into service. Two of these were Episcopal cars; five were Baptist cars. The two Episcopal cars were converted under the plan of Bishop G. Mott Williams and served Northern Michigan. Bishop Mott felt that a chapel car could aid him in reaching the unchurched in the isolated territory of Northern Michigan. Some of the challenges faced by Williams in his missionary work included: communities that became difficult to reach when the waterways used for transportation became impassable during cold months, substantial populations of non-English speaking immigrants, and mining schedules that interfered with morning church services (Taylor and Taylor 1999:64-65).

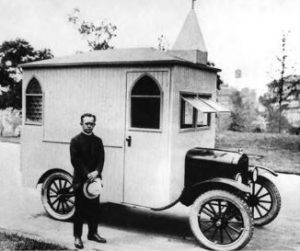

The first chapel car of Northern Michigan may have been in use as early as 1891 and served in small towns and villages, as well as mining and lumber camps. However, this car was old and borrowed, and due to its inconvenience was retired around 1894. Unlike other chapel car proponents, Williams did not receive the donations or funding that would have enabled him to build a new chapel car. This did not stop him from believing in the benefits of a chapel on wheels. By 1895, Williams had another converted car operating as a chapel car in Michigan. Along with typical travel in towns along the rail line, this car served, for a time, as the temporary church in a town which had lost its church to a fire. After falling into disuse, the second chapel car of Northern Michigan was sold around 1903. Williams appears to have tried other means of mobile chapels after both chapel cars were retired from service. These other means included a boat which served a number of island communities, a portable chapel which could be transported by wagon or train, and an automobile chapel (Taylor and Taylor  1999:65-71).

1999:65-71).

Emmanuel, the second Baptist chapel car to be built, was dedicated in Denver on May 24, 1893. [Image at right] This car was ten feet longer than its predecessor, Evangel, and could seat 115 people. Emmanuel was constructed during the financial panic of 1893 and the cost quoted for the car by the Barney & Smith Car Company did not include any interior features. Therefore, items needed for the car from airbrakes to furnishings were donated by both businesses and churches. The first missionaries to travel with Emmanuel were the Wheelers, the same husband and wife who were the first missionaries on Evangel. While traveling on Emmanuel, the Wheelers held revival services in towns they had visited when aboard Evangel, administered baptisms, organized Sunday schools and churches, and established missions. In 1895, the Wheelers took the chapel car in for repairs and headed home for a stay in Minnesota. While traveling, their train was involved in a wreck and Mr. Wheeler was tragically killed. After the death of Mr. Wheeler, a stained glass image of him was installed in the door leading into the living apartment of the Emmanuel. Under a number of other missionaries, Emmanuel continued its service in the West and Northwest until its official retirement in 1942 (Taylor and Taylor 1999:75-100).

Glad Tidings, dedicated on May 25, 1894, was the third Baptist chapel car to enter into service. The car was a gift of William Hills, a New York businessman, who had been one of the donors for Evangel. Hills paid for the cost of Glad Tidings in honor of his wife. His gift was given upon the condition that the money for a fourth chapel car be raised by the close of 1894 (Taylor and Taylor 1999:105). The first missionaries to serve aboard Glad Tidings were Reverend Charles Herbert Rust and his wife, Mrs. Bertha Rust. Along with the typical inclusions for a chapel car, Glad Tidings housed a library of approximately sixty volumes of Christian literature that were loaned out to the townspeople during stops. These small towns rarely included libraries or book stores, and without the presence of a church, religious literature was hard to obtain. For the chapel car missionaries like the Rusts, the loaning of literature and distribution of tracts became a vital part of their service (Rust 1905:8-9, 73).

It is important to note that while the idea for a chapel car was conceived with the purpose of helping those who had settled in frontier towns, rail workers were also served by this unique form of missionary service [Image at right]. Many of the men who worked for the railroads were frequently away from their homes and unable to attend traditional religious services. The chapel car offered them a church that welcomed them as they were and was understanding of their scheduling constraints. Reverend Rust was known to hand out cards to these rail workers that stated, “Come just as you are” (Rust 1905:103). Men would arrive for service in their work clothes and leave when they needed to attend to their duties, even if this meant they were unable to attend the entire service (Rust 1905:103-04).

The Rusts served on Glad Tidings for a number of years, part of this time with their daughter Ruth. When their second daughter was born, the Rusts set up a home near St. Paul, Minnesota. Mrs. Rust and the children spent most of their time at this location, while Reverend Rust continued to serve on Glad Tidings with an assistant (Rust 1905:24-25). Rust eventually left chapel car service to spend more time with his family. His book, A Church on Wheels, which was published in 1905, recounted his experience on Glad Tidings and was a considerable contribution to chapel car ministry. After Reverend Rust left chapel car work, Glad Tidings continued its travels in the hands of other missionaries before being removed from service in 1926 (Taylor and Taylor 1999:127-28).

The fourth Baptist chapel car, Good Will, was built after the agreement with William Hills was fulfilled. Dedicated in 1895, Good Will began its service in Texas. In 1900, the car was damaged during the Galveston hurricane, the deadliest natural disaster in modern American history. Fortunately, the missionaries who were assigned to the car were not aboard at the time of the hurricane and were thus unharmed. Boston Smith travelled to Texas in November of 1900 to speak to churches on the importance of chapel car work and encourage donations for Good Will’s repairs. Texas Baptist congregations raised money and the Texas Baptist General Convention granted funds to cover the costs of repairs (Taylor and Taylor 1999:140-41). During its subsequent years in service, Good Will served areas in the Midwest, West, and Pacific Northwest before being parked in California in 1938.

Messenger of Peace was the fifth Baptist chapel car to be built. Dedicated in 1898, this car was also referred to as “the Ladies’ Car” due to the fact that all of the funds necessary for constructing the car were collected by Baptist women across the country. This car began its service in the Midwest, and later served in the West and Pacific Northwest. In 1904, the American Baptist Publication Society displayed Messenger of Peace at the World’s Fair in St. Louis. It is reported that during one day alone, the car had more than 10,000 visitors. A marriage was also performed on the car, with the wedding reception provided by the Pullman Company. It was also during the World’s Fair that Father Francis Kelley visited the Messenger of Peace. The car left an impression on Kelley and he later constructed three Catholic chapel cars with the Catholic Church Extension Society (Taylor and Taylor 1999:163-67).

In 1910, Messenger of Peace and its missionaries were chosen to work with the Railroad YMCA. This work lasted about a year. Along with typical chapel car activities, such as offering religious services and distributing literature, missionaries were tasked with promoting area Railroad YMCAs. These YMCA locations offered rail workers a safe environment with beds, food, spiritual guidance, and chance for physical recreation. After its contracted service with the railroad YMCA ended, Messenger of Peace continued its travels (Taylor and Taylor 1999:169-70). During wartime, the missionaries aboard Messenger of Peace found themselves ministering to an additional population, soldiers who were stationed near the railroad stops. The missionaries encouraged soldiers to attend chapel car meetings by providing cakes and games along with their religious services. After almost fifty years of serving diverse groups across the United States, Messenger of Peace was officially retired in 1949 (Taylor and Taylor 1999:179-80).

Herald of Hope, the sixth Baptist chapel car, was nicknamed “the Young Men’s Car,” after the young men of Detroit’s Woodward Avenue Church who contributed the first thousand dollars for the cost of the car. Dedicated in 1900, Herald of Hope was furnished by Baptists of Detroit and elsewhere. After more than a decade of service in the Midwest, Herald of Hope underwent repairs and was rededicated, continuing its service primarily in West Virginia. Much of the work undertaken in West Virginia focused on miners and loggers. Many of the mining and logging centers did not have churches within a reasonable distance. The chapel car was able to provide religious services in a simple and direct manner that encouraged attendance among men in these communities (Taylor and Taylor 1999:185-207). In 1931, the decision was made to retire Herald of Hope and place the car on a foundation to be used as a permanent church in West Virginia.

The promise and proven success of chapel car ministry caught the attention of Father Francis Clement Kelley, who subsequently brought this new form of reaching the masses to the Catholic Church. Kelley attended the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis where the Baptist chapel car Messenger of Peace was on display. Kelley was impressed by what he learned about chapel cars. In 1906, after becoming the first president of the Catholic Church Extension Society, Kelley wrote about the potential benefits of chapel cars in a publication for the society in hopes of raising support for a Catholic car. Kelley’s piece on chapel cars caught the attention of Ambrose Petry, who was in street car advertising. Petry saw the benefits of a chapel car in terms of  “advertising” for the Catholic Church. He donated the money to buy a used sleeper car and Richmond Dean, a vice president of the Pullman Company, had the interior of the car redone to fit the needs of a chapel car [Image at right]. The car was designed to hold sixty-five people during services and had two small rooms for the priest and attendant. This car, which was officially blessed in 1907, was named St. Anthony (Kelley 1922:71; Taylor and Taylor 1999:213-16).

“advertising” for the Catholic Church. He donated the money to buy a used sleeper car and Richmond Dean, a vice president of the Pullman Company, had the interior of the car redone to fit the needs of a chapel car [Image at right]. The car was designed to hold sixty-five people during services and had two small rooms for the priest and attendant. This car, which was officially blessed in 1907, was named St. Anthony (Kelley 1922:71; Taylor and Taylor 1999:213-16).

St. Anthony began its travels in Kansas and would later continue its service across the country, including stops along the East Coast. When St. Anthony set out, the normal routine was to stay in a town approximately a week. Each day there would be a sermon and Mass in the morning, instruction in the afternoon for children, and a sermon and benediction in the evening (Kelley 1922:90). The priest and attendant also distributed literature during stops, which proved to be a successful missionary strategy (Kelley 1922:70). Crowds were large and baptisms were common during chapel car stays. As Kelley had hoped, St. Anthony proved to be a positive addition to the Catholic missionary cause. He later wrote about chapel cars in The Story of Extension, saying:

The most wonderful thing about the Chapel Cars is their ‘pulling power.’ They discover their own congregations. When a Chapel Car comes to town everyone knows about it and Catholics begin to spring up all around it. People who had never before been known as Catholics suddenly show interest in the Church, and come to the services…The beauty and the up-to-dateness of the Chapel Car give [fallen away members] a sense of sharing in its glory; and they begin to boast, amongst their surprised neighbors, of the Church they had never before claimed as their own (Kelley 1922:97).

Despite its success, St. Anthony was upstaged when a new chapel car, St. Peter, was constructed. During one of St. Anthony’s stops in Ohio, a businessman named Peter Kuntz visited the chapel car. After viewing this wooden, repurposed car, Kuntz suggested that a new chapel car should be built for use by the Catholic Church, and he donated the necessary funds. This new car, St. Peter, was dedicated in 1912 (Kelley 1922:91-92). Constructed of steel, St. Peter was eighty-four feet long with modern designs and a mahogany-finished interior (Taylor and Taylor 1999:242). Before being given to the Diocese of North Carolina in 1939, St. Peter served areas including the Midwest, West, and Pacific Northwest.

The third and final Catholic chapel car to be constructed was St. Paul, which was also donated by Peter Kuntz. Dedicated in 1915 in New Orleans, St. Paul featured a number of improvements over its predecessor to make life on the chapel car more convenient and comfortable for the priest and attendants. St. Paul served primarily in the Southeast, fulfilling a request by Peter Kuntz that the car work in this area. After a short stint traveling in the Midwest, St. Paul was put into storage, where it sat until being included as an exhibit in the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. St. Paul then went through another period of disuse before its donation to the Catholic Diocese of Great Falls, Montana in 1936. Although the Catholic Church was the last to begin building chapel cars, it was also the Church to have the last chapel car mobile (Taylor and Taylor 1999:268-79). While St. Paul holds the claim to being the last mobile chapel car, the Baptist chapel car Grace is the car which has remained “in service” for the longest period of  time.

time.

Grace was the last of the Baptist chapel cars to be constructed. The only Baptist chapel car to be made of steel, it was dedicated in California in 1915. The funds needed to build this chapel car were donated by the Conway family in memory of their daughter, Grace. [Image at right] As early as 1913, the American Baptist Publication Society began working on raising the funds for a new chapel car. Although more than a decade had passed since the last chapel car had been dedicated and new modes of missionary transport (such as chapel boats and chapel automobiles) had entered service, the American Baptist Publication Society still felt that there was a distinct need for chapel cars. Grace was built to have more of a “church look” with arch designs and stained glass touches. One of the first places Grace made a stop was San Francisco to attend the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which was also attended by the Catholic chapel car St. Peter. During the exposition, services were conducted, tours were given of the chapel car, and Baptist tracts were distributed (Taylor and Taylor 1999:283-85). Grace went on to serve in the West and Midwest before being moved to Green Lake, Wisconsin, where it has remained on public display (Taylor and Taylor 1999:298-302).

For a variety of reasons (See, Issues/Challenges), the chapel car era drew to a close in the United States around  the time of World War I, although some chapel cars have continued to operate elsewhere, most notably Russia.

the time of World War I, although some chapel cars have continued to operate elsewhere, most notably Russia.

There were some attempts to replace railroad chapel cars with automotive chapel cars, [Image at right] but this innovation never achieved the same level of popularity and did not possess the same geographic reach of their railway counterparts.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

While particular religious beliefs varied among the different Churches who owned and operated chapel cars, Baptists, Episcopalians, and Catholics shared the belief that chapel cars were valuable instruments of missionary service. As the settlement boundaries of the United States were expanded, religious organizations and their missionaries adopted new methods of missionary work to meet the needs of frontier communities and settlers. Religious organizations believed that it was their duty to spread Christian morals to these communities and help direct inhabitants away from lives of sin. Missionaries assigned to frontier locations found that homes were scattered across great distances and communities often lacked any sort of religious activity. Frontier missionaries often traveled by foot or horseback to reach settlers and had difficulty finding lodging. Chapel cars offered a solution to these challenges while appealing to both those who were religiously affiliated and those who were not (Kelley 1922:97; Rust 1905:72; Taylor and Taylor 1999:63-65).

Religious leaders and supporters of chapel cars believed that there was a need for the influence of religion in the American frontier and that the presence of chapel cars could help positively influence frontier communities. Hoping to garner support and raise funds for the first Catholic chapel car, Father Kelley outlined the benefits of chapel cars in an editorial for the Catholic Extension publication:

Railroads pull Chapel Cars free of charge. They cost little to maintain. They house both pastor and congregation; the last for the period of the religious service; the first all the time, for the car is a fairly comfortable living room. Chapel Cars solve the problem of poor hotels and dugout quarters in pioneer states. Chapel cars insure neglected places being visited regularly. The very novelty of the visit draws non-Catholics to hear the missionary. Literature can be carried in quantities in a Chapel Car, and Mass said daily—not a slight consideration for a spiritually hungry priest. A Chapel Car could supply scattered families with all they need of ‘mission goods,’ for there is room to keep them in stock. The missionary priest could have a place in which to instruct children where only few families are to be found, and stay contented as long as necessary, without worry or lonesomeness (Kelley 1922:69-70).

Father Kelley’s editorial highlights the importance that was placed on providing religious experiences to those in “neglected” places, as well as the hope that chapel cars were the novel approach needed for this new type of mission environment. He was not alone in his beliefs about the potential of chapel cars, as Episcopal and Baptist proponents of chapel cars before him had expressed similar thoughts. Charles Rust, a Baptist missionary, believed that chapel cars could help revive Christianity in the American frontier and show that “Christianity [was] not dying, but [was] on the move” (Rust 1905:121).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Religious rituals and practices varied among chapel cars of different denominations, with missionaries carrying out the expected practices for their particular type of religious service. The articles aboard chapel cars allowed the missionaries to carry out practices just as they would in a physical church building. For instance, the Catholic chapel car, St. Anthony, was equipped with a communion railing which could be moved and converted into a confessional, an altar with storage drawers for sacred vessels and vestments, and a holy water font (Kelley 1922:89; Taylor and Taylor 1999:216).

Despite their differences, there were some practices shared in common by the Episcopal, Baptist, and Catholic cars. One example of shared practice was music, which played an important role in the services of chapel cars. It was common for chapel cars to have an organ on board that was played by the missionary or attendant. Additionally, hymns were sung by the congregation in attendance, and musically gifted attendants or missionary wives would perform solos (Kelley 1922:88; Rust 1905:81-95). Reverend Charles Rust remarked on the powerful role of his wife’s singing, stating that, “her message in song is as important as the preacher’s message in word” (Rust 1905:88). It was also common for missionaries to supplement services by distributing religious literature, holding meetings for children, and visiting homes in the surrounding area. These additional activities helped the missionaries attract people to their services and helped ensure continued attendance throughout the chapel car’s stay.

Reverend Charles Rust detailed the method for a week’s meetings with townsfolk aboard the Baptist chapel car, Glad Tidings. Rust would begin the week by discussing the “value of their lives in God’s sight,” the harm which could be caused by sin, and how the “Saviour…can cleanse and beautify them” (Rust 1905:64). By the fourth or fifth meeting, Rust would ask attendees to yield their hearts to Christ and to let Rust know if they had chosen to do so. By Sunday, those who had decided to yield their hearts to Christ would feel comfortable discussing their decision with their friends and neighbors. According to Rust, this would often result in others wanting to yield their hearts to Christ as well. If the chapel car stayed in a town for more than a week, subsequent meetings would focus on the Church and how to live the Christian life (Rust 1905:64-65).

One week was the typical length of a chapel car’s stay, although lengthier visits were not uncommon when there was a particular need in the town, such as the construction of a church. For Baptists, a successful stop in a town often resulted in scheduled  prayer meetings, the creation of a young people’s or woman’s aid society, or the organization of Sunday school. [Image at right] During a chapel car’s stop, it was not uncommon for funds to be raised to construct a church building and/or to hire a preacher. While chapel car missionaries often extended their stays to help in the construction of new churches, an established church was not the immediate goal for all communities. Chapel car missionaries had to be cognizant of the funds required to start and maintain a church. For some communities, missionaries encouraged starting prayer groups, establishing Sunday schools, or hiring itinerant preachers as steps toward establishing churches (Rust 1905:125, 141-42, 150, 168).

prayer meetings, the creation of a young people’s or woman’s aid society, or the organization of Sunday school. [Image at right] During a chapel car’s stop, it was not uncommon for funds to be raised to construct a church building and/or to hire a preacher. While chapel car missionaries often extended their stays to help in the construction of new churches, an established church was not the immediate goal for all communities. Chapel car missionaries had to be cognizant of the funds required to start and maintain a church. For some communities, missionaries encouraged starting prayer groups, establishing Sunday schools, or hiring itinerant preachers as steps toward establishing churches (Rust 1905:125, 141-42, 150, 168).

Not all towns that chapel cars visited were churchless. Chapel car missionaries frequently encountered towns (especially after frontier areas became more populated) with established churches, but waning participation. Chapel cars were able to revitalize religious participation by sparking interest in both “fallen away” members and those who were not yet religiously affiliated. Additionally, chapel car missionaries could help reorganize activities like Sunday school and could help the existing church raise funds needed for repairs or securing a pastor (Kelley 1922:97-98, Rust 1905:104).

LEADERSHIP/ORGANIZATION

Chapel cars and their missionaries fell under the leadership of the religious institution to which they belonged. For instance, the first chapel car, Church of the Advent, was constructed and operated under the care of William David Walker, who was Episcopal Bishop of North Dakota. Part of Bishop Walker’s duties included overseeing missionary work in that area. After developing the idea for a chapel car, he turned to the Mission Board of the Protestant Episcopal Church to help him raise the funds necessary for the car’s construction. After Bishop Walker was called to serve in New York in 1897, use of Church of the Advent stopped. Walker’s successor did not share the same opinion about the effectiveness of chapel cars and felt that funds would be put to better use elsewhere (Taylor and Taylor 1999:18, 23-24).

In the case of the Baptist denomination, chapel cars fell under the care of the American Baptist Publication Society, which was just one of many Baptist organizations. In the early years of chapel car service, chapel car missionaries were expected to only partake in activities that fell under the authority of the American Baptist Publication Society, such as organizing Sunday schools or distributing Baptist literature. However, as chapel cars and their missionaries began to establish a record of success in the field, they began to take on activities, such as establishing churches, which had previously only been the domain of other Baptist organizations (Rust 1905:155-61).

The three chapel cars of the Catholic Church fell directly under the watch of the Catholic Church Extension Society. Father Francis Kelley served as the first president of this society, which was founded in 1905. The main goal of this society was to raise money that would enable the Catholic faith to be brought to isolated, underserved communities. Given his position in this society, Bishop Walker easily made the case for the usefulness of chapel cars (Taylor and Taylor 1999:214-15).

Individual missionaries had quite a bit of autonomy in terms of determining needs within a particular community, deciding on the length of stays in towns, and organizing activities during their stops. The missionary often had a role in deciding what towns were visited, with communities often putting in requests for chapel car service. However, these decisions were ultimately overseen by the missionary’s religious organizations, which could schedule stops and events that were thought to be the best use of the chapel car. Additionally, the religious organizations ultimately determined who served where and missionaries could be transferred to another area of the country or separated from chapel car service.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Chapel cars, of course, were never a complete answer to reaching unchurched populations. Ultimately they were relatively few in number, and there were many locations they simply could not reach. Another similar form during this same era was chapel boats. These floating chapels serviced residents and seafaring workers populations in coastal areas and inland rivers (Kyriakodis 2014). For example, the Seamen’s Church Institute was founded by Episcopalians  in New York to serve sailors passing through New York Harbor and constructed the Church of Our Savior floating chapel to support this mission (“Floating Chapels” 2018). [Image at right] Floating churches of various kinds have also been identified in Australia, Cambodia, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom. Most recently, the Russian Orthodox Church constructed the Prince Saint Vladamir in 2004, which serves populations along the Volga River (Bishop 2011).

in New York to serve sailors passing through New York Harbor and constructed the Church of Our Savior floating chapel to support this mission (“Floating Chapels” 2018). [Image at right] Floating churches of various kinds have also been identified in Australia, Cambodia, Germany, Russia, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom. Most recently, the Russian Orthodox Church constructed the Prince Saint Vladamir in 2004, which serves populations along the Volga River (Bishop 2011).

Chapel cars faced a number of challenges through their brief history and were gradually retired from service. One of the most substantial challenges for chapel car proponents was securing funding and support. Most chapel cars were funded by wealthy donors, denominational supporters, and railway car construction companies. While supporters were willing to underwrite chapel car construction, there was considerably less enthusiasm for paying for ongoing maintenance and repair costs. At best, chapel cars were viable only so long as railway companies agreed to transport the cars free of charge and to give the accompanying clergy and assistants free travel passes. Railroad companies faced another problem as well as chapel cars required sidetracks if they were to remain in any location for more than a brief period. Tying up sidetracks limited other transportation needs and created scheduling problems.

Chapel cars also created arduous work for the missionaries responsible for operating them. Reverend Rust, who served on Glad Tidings, described the long list of duties facing the chapel car missionary in the following way:

The missionary on the chapel car [was] expected to be preacher at four hundreds meetings a year; to be able to call at every home in a large parish in a few weeks; to help in the cooking department of his parsonage and the janitor work in the chapel; to train and organize the new material into all forms of Christian service; to prepare them for baptism and church-membership; to lead in raising money for a new church building; to personally go over the country to secure this money, and to help actually in the hauling of stone, laying the foundation, putting up the building, and paying the bills. All of this to be done in two or three months, and sometimes in six or seven weeks” (Rust 1905:79).

All of these functions had to be carried out with very little space and very few amenities.

One of the most important factors in the decline of chapel cars was changes in railway regulations. New U.S. American Railway Association (ARA) regulations prohibited operating wooden cars (too dangerous) on mainline railroads after 1910 and U.S. ICC regulations barred the railroads from transporting the cars for free. The combination of moving from wood to steel construction and elimination of cost-free transportation dramatically reduced the viability of chapel cars. Another factor was World War I era regulations requiring that train tracks be kept clear for troop and war materials transportation (“The Movement Ends” 2017). In 1917 the government took over control and operation of the railroads, which meant that missionaries could no longer rely on their relationships with railroad officials to assist in the transportation of chapel cars. While rail lines were restored to private operation in 1920, railway companies faced rising costs and financial hardships that reduced their inclination for financial largesse. Finally, much of what had once been considered “frontier” religious territory had been touched by the missionary efforts of various religious groups, and so there simply was less “unclaimed” religious territory.

As cars became too costly or inconvenient to operate, they were simply retired from service. Some of these retired chapel cars were moved to towns where they served as stationary churches, some were dismantled with items being given to churches for their use, and some were abandoned and forgotten (Taylor and Taylor 1999:320-63). In recent decades, a number of chapel cars have undergone restoration projects by those interested in religious or rail history (“Chapel Car Emmanuel” n.d.; Deseret News 2010; Emerson and HistoryLink.org Staff 2011; Lacitis 2012).

The legacy of chapel cars has lived on in other forms of mobile churches. Perhaps the most comparable successors to chapel cars have been trucker churches, which provide mobile chapels at truck stops across the United States. They resemble chapel cars in that they emerged in response to the construction of Interstate Highway System and the corresponding rise of long-distance truck transportation. Like railway chapel cars, trucker churches primarily serve a group that has limited access to religious services, in this case due to demanding work schedules and considerable time spent away from home. Organizations like TFC (Transport for Christ) Global found success in offering religious services to truckers in converted truck trailers, and because of this success, began to establish permanent chapels at some truck stops (Hott and Bromley 2014).

Although no rail chapel cars currently operate in the United States, they do continue elsewhere with a somewhat different purpose. For example, Russian Railway Tours, a company started in 2005, offers a fourteen night Trans-Siberian trip. In order to meet the needs of passengers during this extended  travel, a temple car was constructed. This car is designed to “conduct Orthodox worships on both passage and at the stops” and contains common elements of a church including an altar and iconostasis (Burger 2019). Perhaps the latest and most innovative chapel car also is Russian. [Image at right] This car is parachute dropped into remote areas by the Orthodox Church. Priests also arrive by parachute Wainright 2013).

travel, a temple car was constructed. This car is designed to “conduct Orthodox worships on both passage and at the stops” and contains common elements of a church including an altar and iconostasis (Burger 2019). Perhaps the latest and most innovative chapel car also is Russian. [Image at right] This car is parachute dropped into remote areas by the Orthodox Church. Priests also arrive by parachute Wainright 2013).

IMAGES

Image #1: Russian Orthodox chapel car on the Manchurian Railway.

Image #2: Episcopal Bishop, William David Walker.

Image #3: The first American chapel car, Church of the Advent, the Cathedral Car of North Dakota.

Image #4: The first Baptist chapel car, Evangel.

Image #5: The second Baptist chapel car, Emmanuel.

Image #6: Railroad workers inside the chapel car Glad Tidings.

Image #7: Interior of the St. Anthony chapel car.

Image #8: Grace chapel car with a “church look.”

Image #9: Automotive chapel car.

Image #10: A Young People’s meeting at the Glad Tidings chapel car.

Image #11: Church of Our Savior floating chapel.

Image #12: Russian paradrop church.

Bishop, Bill. 2011.”‘Holy Boat’ Batman.” Marine Installers Rant, May 15. Accessed from http://themarineinstallersrant.blogspot.com/2011/05/holy-boat-batman.html on 20 October 2019.

bmberry. 2019. “America’s Chapel Car.” Timetoast.com. Accessed from https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/america-s-chapel-car on 20 October 2019.

Burger, John. 2019. “Trans-Siberian train features Orthodox chapel on board.” Aleteia, February 13. Accessed from https://aleteia.org/2019/02/13/trans-siberian-train-features-orthodox-chapel-on-board/ on 12 July 2019.

“Chapel Car Emmanuel.” n.d. Historic Prairie Village. Accessed from https://www.prairievillage.org/chapel-car/ on 10 July 2019.

Deseret News. 2010. “First Baptist Church train-car chapel in Rawlins now 85 years old.” Deseret News, July 2. Accessed from https://www.deseret.com/2010/7/2/20125439/first-baptist-church-train-car-chapel-in-rawlins-now-85-years-old on 12 July 2019.

Emerson, Stephen and the HistoryLink.org Staff. 2011. “Historic Messenger of Peace railroad chapel car begins long road to restoration on September 13, 2007.” HistoryLink.org, May 18. Accessed from https://www.historylink.org/File/9825 on 14 July 2019.

“Floating chapels for 19th century sailor souls.” 2018. Ephemeral New York. Accessed from

https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2018/05/14/the-floating-chapels-for-19th-century-sailors/ on 10 November 2019.

Green, George. 2007. Special Use Vehicles: An Illustrated History of Unconventional Cars and Trucks Worldwide. Jefferson & Co.: McFarland & Company.

Hott, Leah and David G. Bromley. 2014. “Trucker Churches.” World Religions and Spirituality Project, January 18. Accessed from https://wrldrels.org/2016/10/08/trucker-churches/ on 10 July 2019.

Kelley, Francis Clement. 1922. The Story of Extension. Chicago, IL: Extension Press. Accessed from https://books.google.com/books?id=27QOAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false on 10 July 2019.

Kyriakodis, Harry. 2014. “The Floating Church And Its Successors Along The Delaware.” Accessed from https://hiddencityphila.org/2014/02/the-floating-church-and-its-successors-along-the-delaware/ on 10 November 2019.

Lacitis, Erik. 2012. “Holy roller restored: Old train car that brought religion now being saved.” The Seattle Times, December 27. Accessed from http://o.seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2019996234_chapelcar27m.html on 12 July 2019.

Miklós, Vincze. 2014. “These Train Cars Converted Into Churches Are Literal Holy Rollers.” Gizmodo. Accessed from https://io9.gizmodo.com/these-train-cars-converted-into-churches-are-literal-ho-1598991193 on 23 October 2019.

Rust, Charles Herbert. 1905. A Church on Wheels; Or, Ten Years on a Chapel Car. Philadelphia, PA: American Baptist Publication Society. Accessed from https://books.google.com/books/about/A_Church_on_Wheels.html?id=7doEAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button#v=onepage&q&f=false on 10 July 2019.

Smith, Boston W. 1896. The Story of Our Chapel Car Work. Philadelphia, PA: American Baptist Publication Society. Accessed from http://baptiststudiesonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ on 10 July 2019.

Taylor, Wilma Rugh and Norman Thomas Taylor. 1999. This Train is Bound for Glory: The Story of America’s Chapel Cars. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press.

“The Movement Ends.” 2017. The Pullman State Historic Site. Accessed from http://www.pullman-museum.org/ on 20 October 2019.

“The Religious World: The Gospel on Wheels.” 1896. The Outlook: A Family Paper 54.10:436. Accessed from https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=2qwjAQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA417 on 11 July 2019.

Wainright, Oliver. 2013. “Russian army introduces the flying Orthodox church-in-a-box.” The Guardian, April 2. Accessed from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/architecture-design-blog/2013/apr/02/russian-army-flying-church on 10 November 2019.

Walker, William D. 1896. “Annual Report of the Missionary Bishop of North Dakota.” The Spirit of Missions 61.12:576-78. Accessed from https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=PLnSAAAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.PA578 on 10 July 2019.

14 November 2019