Swedenborgianism and the Visual Arts

VISUAL ARTS TIMELINE

1688 (January 29): Emanuel Swedenborg was born in Stockholm.

1755 (July 6): John Flaxman was born in York, England.

1757 (November 28): William Blake was born in London.

1772 (March 29): Swedenborg died in London.

1783 (December 5): An organization (named “Theosophical Society” in 1784) devoted to promoting Swedenborg’s teachings was founded in London. At least seven of its first members were artists.

1789 (April): The first General Conference of the Swedenborg–inspired New Church was held in London. William Blake was among the participants.

1793: Prussian sculptor John Eckstein moved to Philadelphia and joined the local congregation of the New Church there.

1805 (June 29): Hiram Powers was born in Boston, Vermont.

1825 (May 1): George Inness was born in Newburgh, New York.

1826 (December 7): John Flaxman died in London.

1827 (August 12): William Blake died in London.

1847 (October 15): Ralph Albert Blakelock was born in New York.

1865: The Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco was built with the cooperation of several Swedenborgian artists.

1873 (June 27): Hiram Powers died in Florence, Italy.

1894 (August 3): George Inness died in Bridge of Allan, Scotland.

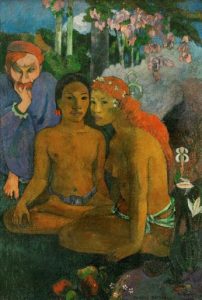

1902: Paul Gauguin painted the Swedenborg–inspired Contes barbares.

1909: Swedenborgian architect Daniel H. Burnham produced what became known as the 1909 Plan for the City of Chicago.

1913–1919: The Bryn Athyn Cathedral was built in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

1919 (August 9): Ralph Albert Blakelock died in Elizabethtown, New York.

1932: Jean Delville painted Séraphita, based on the homonymous Swedenborgian novel by Honoré de Balzac.

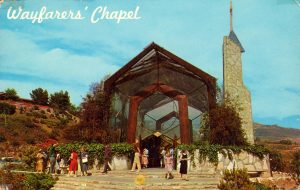

1949–1951: The Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, designed by architect Lloyd Wright, the son of Frank Lloyd Wright, was built.

Early 1980s–1988: Lee Bontecou lived in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

1985 (April): The first installation/performance in Chicago of Angels of Swedenborg, by Ping Chong took place.

2011 (March 30–April 30): Pablo Sigg exhibited in Los Angeles the installation The Swedenborg Room.

2012 (January 26): The performance/installation of La Chambre de Swedenborg at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Strasbourg, France took place.

VISUAL ARTS TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

In more than 13,000 pages of his collected writings, where he discussed an immense variety of different topics, Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) [Image at right] did not offer a theory of aesthetics or art. Yet, according to American art historian Joshua Charles Taylor (1917–1981), among the new forms of spirituality, in the nineteenth century “only the Swedenborgian teaching had a direct impact on art” (Dillenberger and Taylor 1972:14).

an immense variety of different topics, Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) [Image at right] did not offer a theory of aesthetics or art. Yet, according to American art historian Joshua Charles Taylor (1917–1981), among the new forms of spirituality, in the nineteenth century “only the Swedenborgian teaching had a direct impact on art” (Dillenberger and Taylor 1972:14).

Taylor’s comment should be qualified since, in the nineteenth century, at least Rosicrucianism should be added, while Theosophy and Christian Science had their greatest impact on art in the twentieth century. There is, however, little doubt that Swedenborg had an influence on artists that can only be qualified as exceptional, the more so if we consider that the Swedenborgian movement was, and remains, comparatively small and divided into different branches. How was this possible?

In the works of several leading spiritual teachers—including Theosophy’s Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and Christian Science’s Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910)—there is no explicit theory of aesthetics, but there is what Jane Williams-Hogan (1942–2018), the American scholar who first researched the influence of Swedenborg on the visual arts, regarded as an implicit aesthetic philosophy (Williams-Hogan 2012, 2016). This implicit aesthetic theory can be summarized in four points.

First, Swedenborg maintained that beauty is predicated of truth (Arcana Cœlestia § 3080, 3821, 4985, 5199, and 10,540: I follow the Swedenborgian tradition of quoting Swedenborg’s works by paragraphs). This is based on a solid tradition. For Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), “pulchrum proprie pertinet ad rationem causae formalis” (“the beauty, strictly speaking, is connected with reason as its formal cause,” Summa Theologiae, I, q.5, a.4, ad1). That “verum et bonum et pulchrum convertuntur” (“truth, goodness, and beauty converge”) was often repeated by later theologians, although neither Aquinas nor his predecessors explicitly used these words.

Second, truth for Swedenborg has two foundations, one from the Word, i.e. from divine Revelation, and the other from nature. The first human beings were able to see immediately the truth of the Revelation, and to see nature as a manifestation of the divine. Unfortunately, we have lost this ability. But we are not without hope.

Third, for Swedenborg, the tool for recovering something of the lost gaze of the ancients is the theory of correspondences. “Nothing can exist anywhere in the material world that does not have a correspondence with the spiritual world—because if it did, it would have no cause that would make it come into being and then allow it to continue in existence. Everything in the material world is an effect. The causes of all effects lie in the spiritual world, and the causes of those causes in turn (which are the purposes those causes serve) lie in a still deeper heaven” (Secrets of Heaven §5711).

Fourth, art is in itself a divine enterprise. While Swedenborg’s theory of correspondences can be applied by anybody who would care to study it to both the interpretation of the Bible and personal spiritual life, real artists are inherently equipped to perceive, and show to others, the divine causes beyond natural effects.

NOTABLE MEMBERS ARTISTS

Anshutz, Thomas (1851–1912). American painter.

Blake, William (1757–1827). English painter and poet

Blakelock, Ralph Albert (1847–1919). American painter.

Bontecou, Lee (1931–). American sculptor.

Burnham, Daniel Hudson (1846–1912). American architect.

Byse, Fanny Lee (1849–1911). Swiss sculptor and painter.

Chazal, Malcolm de (1902–1981). Mauritian painter.

Clark, Joseph (1834–1926). British painter.

Clover, Joseph (1779–1853). British painter.

Cosway, Richard (1742–1821). British portrait painter.

Cranch, Christopher Pearse (1813–1892). American painter.

Duckworth, Dennis (1911–2003). British New Church minister and painter.

Eckstein, Frederick (1787–1832). Son of John Eckstein, American sculptor.

Eckstein, John (1735–1817). German painter and sculptor.

Emes, John (1762–1810). English engraver and painter.

Flaxman, John (1755–1826). English sculptor.

Fry, Henry Lindley (1807–1895). British-American woodcarver.

Fry, William Henry (1830–1929). British-American woodcarver, son of Henry Lindley Fry.

Gailliard. Jean–Jacques (1890–1976). Belgian painter.

Gates, Adelia (1825–1912). American painter.

Giles, Howard (1876–1955). American painter.

Girard, André (1901–1968). French painter.

Hyatt, Winfred (1891–1959). Canadian stained-glass artist.

Inness, George (1825–1894). American painter.

Keith, William (1838–1911). Scottish-American painter.

Khnopff, Fernand (1858–1921). Belgian painter.

Loutherbourg, Philippe-Jacques de (1740–1812). French-British painter.

Page, William (1811–1885). American painter.

Pitman, Benn (1822–1910). British-American wood engraver.

Porter, Bruce (1865–1953). San Francisco painter and stained-glass artist.

Powers, Hiram (1805–1873). American sculptor.

Pyle, Howard (1853–1911). American illustrator.

Pyle, Katharine (1863–1938). American illustrator, sister of Howard Pyle.

Richardson, Daniel (active 1783–1830). Irish painter.

Roeder, Elsa (1885–1914). American painter.

Sanders, John (1750–1825). English painter.

Sewall James, Alice Archer (1870–1955). American poet and painter.

Sharp, William (1749–1824). English engraver.

Sigstedt, Thorsten (1884–1963). Swedish woodcarver.

Smit, Philippe (1886–1948). Dutch painter.

Spencer, Robert Carpenter (1879–1931). American painter.

Worcester, Joseph (1836–1913). Swedenborgian minister and Arts and Craft architect and decorator.

Warren, H. Langford (1857–1917). American architect.

Yardumian, Nishan (1947–1986). American painter

MOVEMENT INFLUENCED NON–MEMBER ARTISTS

Aguéli, Ivan (1869–1917). Swedish painter.

Bergman, Oskar (1879–1963). Swedish painter.

Birgé, Jean Jacques (1952–). French multimedia artist.

Bisttram, Emil (1895–1976). Hungarian-born American painter.

Chong, Ping (1946–) Toronto–born American video and performance artist.

Čiurlionis, Mikalojus Konstantinas (1875–1911). Lithuanian painter and composer.

De Morgan, Sophia (1809–1892). English author of key works on spirit paintings; produced sketches of her visions.

Delville, Jean (1867–1953). Belgian painter, primarily a Theosophist.

Ensor, James (1860–1949). Belgian painter.

Gallen-Kallela, Akseli (1865–1931). Finnish painter.

Gauguin, Paul (1848–1903). French painter.

Jonsson, Adolf (1872–1945). Swedish sculptor.

Milles, Carl (1875–1945). Swedish sculptor.

Munch, Edvard (1863–1944). Norwegian painter.

Powers, Preston (1843–1931). Son of Hiram Powers, American sculptor.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel (1828–1882). English painter.

Shawk Brooks, Caroline (1840–1913). American sculptor.

Sigg, Pablo (1974–). Mexican video artist.

Simberg, Hugo (1873–1917). Finnish painter.

Strindberg, August (1849–1912). Swedish writer and painter.

Tholander, Carl August (1835–1910) Swedish painter.

Vedder, Eliuh (1836–1923). American painter and illustrator.

Willcox Smith, Jessie (1863–1935). American illustrator.

Wyeth, Newell Conwers (1882–1945). American illustrator.

Wright, Lloyd (1890–1978). American architect, son of Frank Lloyd Wright.

INFLUENCE ON THE VISUAL ARTS

Swedenborg’s vision of art and beauty obviously appealed to artists. We can distinguish three concentric circles: those baptized into a Swedenborgian church or maintaining at any rate Swedenborgianism as a primary interest in their lives; those directly influenced by Swedenborg’s writings; and those reached by Swedenborg indirectly, i.e. through other artists or writers.

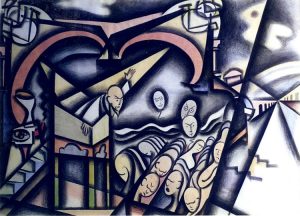

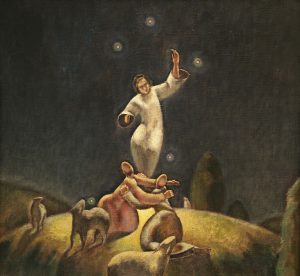

We cannot elaborate here on the third circle. A complete list should include hundreds of names. One example would be the Belgian symbolist painter Jean Delville (1867–1953). He probably did not read Swedenborg personally, but was influenced by novelists and painters interested in Swedenborg, such as Balzac (1799–1850)—in 1932, Delville painted  Séraphitus-Séraphita, the perfectly androgynous being born to Swedenborgian parents in the 1834 Balzac’s novel Séraphita (see Introvigne 2014:89)— [Image at right] and Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921).

Séraphitus-Séraphita, the perfectly androgynous being born to Swedenborgian parents in the 1834 Balzac’s novel Séraphita (see Introvigne 2014:89)— [Image at right] and Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921).

Another example is Lithuanian painter and composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911). Scholars of Čiurlionis, including Genovaitė Kazokas (1924–2015), found in his works influences of Swedenborg’s theories of correspondences and of angels (although his, unlike Swedenborg’s, have wings), which possibly reached the artist through Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867; see Kazokas 2009:86).

A further example of the third circle is Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944), who learned of Swedenborg during his Berlin years through Swedish writer and painter August Strindberg (1849–1912). Strindberg, who had a lifelong interest in Swedenborgianism, in turn noted that Munch’s paintings “recall the visions of Swedenborg” (Steinberg 1995:24).

Nina Kokkinen studied Finnish symbolist painter Hugo Simberg (1873–1917) as an artist who referred explicitly to Swedenborg only once, yet was deeply influenced by Swedenborgian ideas through Finnish master Akseli Gallen–Kallela (1865–1931), who had read several of Swedenborg’s works (Kokkinen 2013).

Another example is Newell Convers Wyeth (1882–1945). Celebrated as one of America’s greatest illustrators, he recalled how Swedenborg was read to him by his teacher and mentor, Swedenborgian Howard Pyle (1853–1911); Lamouliatte 2016; Swedenborgian Church North America 2017).

Perhaps the most illustrious representative of the second circle was Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). He learned about Swedenborg by reading Balzac and Baudelaire, but studied the Swedish mystic’s texts directly, and explicitly acknowledged Swedenborg’s influence. Jane Williams-Hogan has analyzed his mature painting Contes barbares (1902) as a clear example of his use of Swedenborg’s theory of correspondences (Williams-Hogan 2016:131–32). [Image at right]

He learned about Swedenborg by reading Balzac and Baudelaire, but studied the Swedish mystic’s texts directly, and explicitly acknowledged Swedenborg’s influence. Jane Williams-Hogan has analyzed his mature painting Contes barbares (1902) as a clear example of his use of Swedenborg’s theory of correspondences (Williams-Hogan 2016:131–32). [Image at right]

A further example of the second circle is Pre–Raphaelite British painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882). In 2013, Anna Francesca Maddison demonstrated in her Ph.D. dissertation that Rossetti was part of English circles studying both Spiritualism and Swedenborg, whose influence is apparent in paintings such as Beata Beatrix (1864–1870) (Maddison 2013).

Prominent in what Addison calls the “Swedenborgian–Spiritualist” milieu of London was Sophia de Morgan (1809–1892), mother of potter William de Morgan (1839–1917), whose wife Evelyn (1855–1919), a Spiritualist, is someone referred to as the last Pre–Raphaelite painter. Sophia had a lifelong interest in Swedenborg and passed to her family her own Swedenborgian interpretation of Spiritualist phenomena (Lawton Smith 2002:43–45).

Architects of the second circle include Lloyd Wright (1890–1978), the son of Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959). While his more famous father had multiple esoteric interests, the younger Wright familiarized himself with  Swedenborg when he designed the Swedenborgian Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, his masterpiece, built between 1949 and 1951. [Image at right]

Swedenborg when he designed the Swedenborgian Wayfarers Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, his masterpiece, built between 1949 and 1951. [Image at right]

Symbolists were often interested in Swedenborg, both in Europe and the U.S. Elihu Vedder (1836–1923) had his “Swedenborg period” in the years following the Civil War, although his enthusiasm for the Swedish mystic seems to have waned in his later years (Dillenberger 1979; Colbert 2011:159; see Vedder 1910:345).

In Sweden, artists with Swedenborgian connections included sculptors Adolf Jonsson (1872–1945) and Carl Milles (1875–1945), and painters Carl August Tholander (1835–1910), Ivan Aguéli (1869–1917: Sorgenfrei 2019), who eventually converted to Islam, and Oskar Bergman (1879–1963). Bergman also collected valuable first editions of Swedenborg but, when Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie (1892–1975) visited Sweden in 1954, he gave all these books to him, believing he was somewhat connected with Swedenborg’s prophecies (Carlsund 1940; Westman 1997).

In Belgium, several symbolist painters were interested in Swedenborg as part of their eclectic explorations of esotericism. They include James Ensor (1860–1949), who co-authored a life of Swedenborg (Gailliard and Ensor 1955), while Fernand Khnopff, who for several years attended Swedenborgian services in Brussels (Librizzi 2012), belongs to the first circle.

The latter, including artists who were affiliated with one of the Swedenborgian churches at least for a period of their lives, or regarded themselves as Swedenborgians, is not small. Among the members of the Theosophical Society, created in London in 1783 to promote Swedenborg (not to be confused with Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society, founded in 1875 in New York), at least seven were professional artists (Gabay 2005:71). One was John Flaxman (1755–1826), the most celebrated English sculptor of his time (Bayley 1884, 318–339) and one who illustrated Swedenborg’s Arcana Cœlestia (Gyllenhaal 2016, 2014).

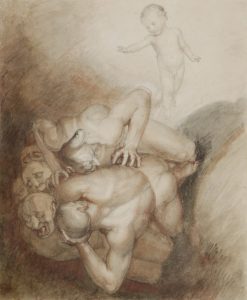

Art historian Horst Waldemar Janson (1913–1982) claimed that, in his prolific funerary work, Flaxman was the first to depict the soul in human form, an idea that later became common but was clearly based on Swedenborg (Janson 1988). Jane Williams-Hogan analyzed the drawing Evil Spirits Thrust Down by a Little Child by Flaxman, [Image at right] intended to illustrate Arcana Cœlestia §1271 and §1272, as true to both the letter (including the image of “women wearing black peaked hats” as part of the evil spirits) and the worldview of Swedenborg (Williams-Hogan 2016:125–26).

Art historian Horst Waldemar Janson (1913–1982) claimed that, in his prolific funerary work, Flaxman was the first to depict the soul in human form, an idea that later became common but was clearly based on Swedenborg (Janson 1988). Jane Williams-Hogan analyzed the drawing Evil Spirits Thrust Down by a Little Child by Flaxman, [Image at right] intended to illustrate Arcana Cœlestia §1271 and §1272, as true to both the letter (including the image of “women wearing black peaked hats” as part of the evil spirits) and the worldview of Swedenborg (Williams-Hogan 2016:125–26).

Among the other early members of the Swedenborgian Theosophical Society were painters Richard Cosway (1742–1821), Philippe–Jacques de Loutherbourg (1740–1812), Daniel Richardson (active 1783–1830), and John Sanders (1750–1825), and engravers John Emes (1762–1810) and William Sharp (1749–1824) (Gabay 2005:71).

William Blake (1757–1827), one of the leading artists associated with Swedenborg, was a friend of both Flaxman and Sharp. Both he and his wife, Catherine Boucher (1762–1831), signed the registers of the General Conference, which convened in 1789 as a development of the early Theosophical  Society, to establish a church based on Swedenborg’s writings (Gabay 2005:77).

Society, to establish a church based on Swedenborg’s writings (Gabay 2005:77).

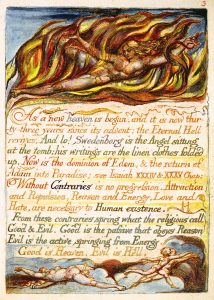

Later, however, Blake grew disenchanted with Swedenborg, and in 1790–1793 wrote an anti–Swedenborgian satire, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Bellin and Ruhl 1985). On the other hand, Blake remained influenced by the Swedish mystic’s doctrines, including the theory of correspondences, until the very end of his life (Deck 1978; Rix 2003). [Image at right

Another early member of the General Conference was Joseph Clover (1779–1853), a British painter and the uncle of Victorian pioneer of anesthesia, Joseph T. Clover (1825–1882), also a Swedenborgian. Clover was one of the founders of the Norwich School of landscape art (Lines 2012:43).

Joseph Clark (1834–1926), a member of the Argyle Square and later Willesden Swedenborgian churches in London, was mostly well-known for his paintings of family life. However, he also represented biblical scenes. In his painting and etching Hagar and Ishmael (1860), for example, Clark interpreted the biblical story according to Arcana Cœlestia § 2661, with reference to the Spiritual Church (Galvin 2016). [Image at right]

John Eckstein (1735–1817) might have been the first American Swedenborgian artist. A well-known Prussian sculptor, he moved to Philadelphia in 1793, where he became a member of the local branch of New Church together with his son, Frederick Eckstein (1787–1832). John Eckstein also sculpted the first known bust of Swedenborg, in 1817. Eckstein Jr. was also an artist and the teacher of Hiram Powers (1805–1873), who would become the leading American neoclassical sculptor (Ambrosini and Reynolds 2007). Hiram was in turn a devoted Swedenborgian (Williams-Hogan 2012:113–15), unlike his son, Preston Powers (1843–1931), who ,had however been raised as a Swedenborgian and sculpted in 1879 another popular bust of Swedenborg (Gyllenhaal 2015:201–08).

Sculptors often took Swedenborg as a subject. They included Caroline Shawk Brooks (1840–1913), famous for her sculptures in butter (Simpson 2007), who was not a Swedenborgian, while Swedish sculptor Adolf Jonsson (1872–1945), whose bust was in Chicago’s Lincoln Park from 1924 to 1976 (when it was stolen; a copy by Magnus Persson replaced it in 2012) was a reader of Swedenborg, and Swiss Fanny Lee Byse (1849–1911), who  also sculpted a bust of the Swedish mystic, was a devout Swedenborgian (Gyllenhaal 2015:208–29).

also sculpted a bust of the Swedish mystic, was a devout Swedenborgian (Gyllenhaal 2015:208–29).

Hiram Powers spent a good part of his life in Italy and hosted the first New Church services there in his home in Florence (Bayley 1884:292–300). [Image at right] Among those in attendance was American painter William Page (1811–1885) (Lines 2004:40), who was deeply influenced by Swedenborg’s doctrine of correspondences, although he was also a Spiritualist (Williams-Hogan 2012:115–117; Taylor 1957).

Some Swedenborgian artists came to the United States from England. In 1851, the woodcarvers Henry Lindley Fry (1807–1895) and William Henry Fry (1830–1929), father and son, members of the New Church in Bath, England, settled in Cincinnati, and soon joined the local New Jerusalem congregation. In 1853, another member of the Bath New Church, wood engraver Benn Pitman (1822–1910), joined them in Cincinnati. Pittman and the Frys were instrumental in launching the Arts and Craft movement in the American Midwest (Trapp 1982).

Other Swedenborgian artists perpetuated the tradition of an art inspired by Swedenborg in the United Kingdom. Dennis Duckworth (1911–2003) was both a painter and a New Church  minister, serving in the latter capacity for over fifty years. In fact, Duckworth was invited to join the Royal College of Arts but declined as he preferred to continue the study of Swedenborgian theology (Glencairn Museum News 2017). [Image at right] The connection between Swedenborgianism and the artistic milieus in the United Kingdom is also confirmed by the career of Ralph Nicholas Wornum (1812–1877), a member of the New Church who became Keeper of the National Gallery in London (Lines 2012:43).

minister, serving in the latter capacity for over fifty years. In fact, Duckworth was invited to join the Royal College of Arts but declined as he preferred to continue the study of Swedenborgian theology (Glencairn Museum News 2017). [Image at right] The connection between Swedenborgianism and the artistic milieus in the United Kingdom is also confirmed by the career of Ralph Nicholas Wornum (1812–1877), a member of the New Church who became Keeper of the National Gallery in London (Lines 2012:43).

A special case of a Swedenborgian artist was Adelia Gates (1825–1912). A specialized botanical painter whose drawings (now at the Smithsonian Institution) greatly helped the science of botany, Gates was a pious Swedenborgian who traveled through several continents in search of plants, always trying to spread at the same time the knowledge of Swedenborg (Silver 1920:250–56).

Perhaps America’s greatest Swedenborgian artist was George Inness (1825–1894), formally baptized in the New Church in 1868. He offered himself Swedenborgian interpretations of some of his paintings, including The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1867), which he explained through Swedenborg’s notion of spiritual rebirth (Promey 1964; Jolly 1986). [Image at right]

Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847–1919), a member of the Swedenborgian church of East Orange, New Jersey, was rediscovered recently and hailed as the American equivalent of Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890), both for his color palette and for the fact that he spent part of his life in  psychiatric institutions (Davidson 1996; Vincent 2003). [Image at right]

psychiatric institutions (Davidson 1996; Vincent 2003). [Image at right]

American painter Christopher Pearse Cranch (1813–1892) read Swedenborg with interest and regarded himself as an independent Swedenborgian. He confessed that he “could be a New Church man, were it not for the doctrine of the identity of Jesus and God” (Ohge 2014:23).

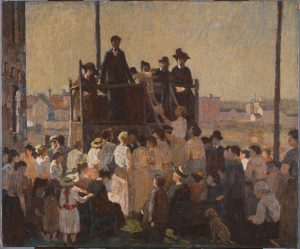

Pennsylvania impressionist and landscape painter Robert Carpenter Spencer (1879–1931) was raised as a Swedenborgian (his father founded and edited the Swedenborgian journal The New Christianity: Peterson 2004:3–4). Although later in life he was quite reserved on his religious ideas, one of his most well-known works, The Evangelist (ca. 1918–1919, now at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC) alludes affectionately to his father’s career as an itinerant Swedenborgian preacher (Peterson 2004:113–15).

[Image at right]

The construction of the Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco in 1867 saw the cooperation of several Swedenborgian artists: Joseph Worcester (1836–1913), minister of that church and decorator; Bruce Porter (1865–1953), painter and stained-glass artist, and William Keith (1838–1911), a Scottish-American painter (Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco 2019; Zuber 2011).

A Canadian artist engaged in multiple Swedenborgian projects was Winfred Hyatt (1891–1959), the principal stained-glass artist for Bryn Athyn Cathedral and later Glencairn, the castle-like mansion of the wealthy Swedenborgian Pitcairn family, now a museum, in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. He also produced Nativity scenes, including one for the Eisenhower White House (Gyllenhaal and Gyllenhaal 2007). Bryn Athyn hosts the headquarters of the General Church of the New Jerusalem, which separated in 1890 from the Swedenborgian Church of North America over doctrinal disagreements. Bryn Athyn has attracted several  Swedenborgian artists, and both its Cathedral (Glenn 2011) [Image at right] and Glencairn Museum host significant works of Swedenborg-inspired art.

Swedenborgian artists, and both its Cathedral (Glenn 2011) [Image at right] and Glencairn Museum host significant works of Swedenborg-inspired art.

One Swedenborgian artist attracted to Bryn Athyn was Swedish woodcarver Thorsten Sigstedt (1884–1963). Sigstedt kept a studio in Bryn Athyn and in the 1950s became well-known for his Stations of the Cross for St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church in Roxborough, a neighborhood in Northwest Philadelphia (Glencairn Museum News 2013). He was also involved in the 1937 schism in the General Church of the New Jerusalem, which led to the foundation of The Lord’s New Church Which is Nova Hierosolyma as a separate denomination (Sigstedt 2001 [1937]).

In general, architects have not been absent among Swedenborgian artists. H. Langford Warren (1857–1917), son of a New Church clergyman, was an active Swedenborgian and designed two Swedenborgian churches. At the time of his death, he was dean of the Harvard School of Architecture and president of the Society of Arts and Crafts (Meister 2003). Daniel H. Burnham (1846–1912) was for forty years a member of the Swedenborgian Church of Chicago. Hailed as “the father of urban planning,” his 1909 Plan of Chicago was influenced by Swedenborg’s idea that the structure of a city should reflect the divine order. He was also called “the father of the Chicago skyscraper.” His works include the celebrated (but now demolished) Rand McNally building (Silver 1920:247–50).

Thomas Pollock Anshutz (1851–1912: Gyllenhaal, Gladish, Holmes and Rosenquist 1988), Howard Pyle (Carter 2002), Alice Archer Sewall James (1870–1955) (Skinner 2011), and Howard Giles (1876–1955; Pasquine 2000:20–21), were Swedenborgian artists who mostly excelled as art teachers. Giles had among his students the Hungarian-American painter Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), who maintained throughout his life a serious interest in Swedenborg, although he was mostly inclined towards Theosophy and Agni Yoga (Pasquine 2000). His encaustics were intended as portals leading into an imminent New Age (Shaull, Parsons and Bottigheimer [Boettigheimer] 2013).

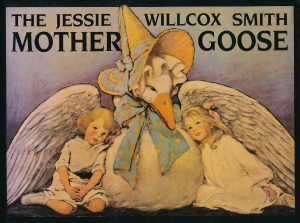

Howard Pyle’s pupils included Swedenborgian painter Elsa Roeder (1875–1914), the daughter of New Church minister Adolph Roeder (1857–1931) (Silver 1920, 260–261), and Jessie  Willcox Smith (1863–1935), a member of Philadelphia’s New Church (Silver 1920:261) who would become a well-known American illustrator. [Image at right] Pyle also taught his younger sister Katharine Pyle (1863–1938). Katharine was herself a member of the New Church according to Ednah C. Silver (1838–1928), who incorrectly refers to her as “Margaret” (Silver 1920:261). In fact, Margaret was the name of Howard and Katharine Pyle’s mother, Margaret Churchman Painter (1828–1885), who was not a painter despite her last name.

Willcox Smith (1863–1935), a member of Philadelphia’s New Church (Silver 1920:261) who would become a well-known American illustrator. [Image at right] Pyle also taught his younger sister Katharine Pyle (1863–1938). Katharine was herself a member of the New Church according to Ednah C. Silver (1838–1928), who incorrectly refers to her as “Margaret” (Silver 1920:261). In fact, Margaret was the name of Howard and Katharine Pyle’s mother, Margaret Churchman Painter (1828–1885), who was not a painter despite her last name.

Among the pupils of Alice James was John William Cavanaugh (1921–1985), “the 20th century’s master of hammered lead.” The artist studied at the Swedenborgian Theological Sch ool in Cambridge, although later he went through a religious crisis (Alt, Strange and Thorson 1985).

ool in Cambridge, although later he went through a religious crisis (Alt, Strange and Thorson 1985).

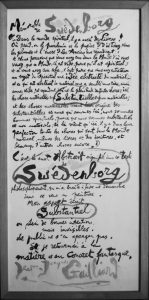

Belgian painter Jean-Jacques Gailliard (1890–1976), a student of Delville, was a member of the Swedenborgian Church and decorated its Brussels chapel in Rue Gachard, inaugurated in 1925 (Clerbois 2013). [Image at right]

Perhaps the most influential twentieth century artist of Mauritius was poet ad painter Malcom de Chazal (1902–1981). He was raised a Swedenborgian and continued to attend for several years Mauritius’ Swedenborgian Church (Hallengren 2013:23), whose founder had been his great-uncle, Joseph Antoine Edmond de Chazal (1809–1879).

In the Netherlands, painter Philippe Smit (1886–1948) became acquainted with the New Church when Theodore Pitcairn (1893–1973) commissioned him to paint several portraits of Swedenborgian ministers. He ended up being baptized in 1926, and believed that Swedenborg had solved the problems he had struggled with in his previous study of the Bible (Gyllenhaal 2014).

French painter André Girard (1901–1968) also met Pitcairn, through Swedenborgian composer Richard Yardumian (1917–1985), and came to accept Swedenborg’s writings as the “true light.” The composer’s son, Nishan Yardumian (1947–1986), studied under Girard and later taught art at the Bryn Athyn College, becoming himself a Swedenborgian painter (Gyllenhaal, Gladish, Holmes and Rosenquist 1988; Glencairn Museum News 2018). [Image at right, below]

In the early 1980s, celebrated American sculptor Lee Bontecou (b. 1931) moved to Bryn Athyn,  where she remained until 1988 (Williams-Hogan 2016:132–37). She described in an interview the community as “Swedenborg–governed,” a positive feature for her since Swedenborg was “a wonderful character” (Ashton 2009). She was regarded by the New York art community as “missing in action” (Tomkins 2003) and got the definite impression that critics did not like that an avant-garde artist was so much involved in esoteric spirituality.

where she remained until 1988 (Williams-Hogan 2016:132–37). She described in an interview the community as “Swedenborg–governed,” a positive feature for her since Swedenborg was “a wonderful character” (Ashton 2009). She was regarded by the New York art community as “missing in action” (Tomkins 2003) and got the definite impression that critics did not like that an avant-garde artist was so much involved in esoteric spirituality.

Swedenborg, however, remains a fascinating reference for contemporary artists, as evidenced by Angels of Swedenborg (1985) by American video and installation artist Ping Chong (Neely 1986), The Swedenborg Room installation (2011) by Mexican artist Pablo Sigg (Mousse Magazine 2011), and the 2012 multimedia show in Strasbourg La chambre de Swedenborg by French artist Jean–Jacques Birgé (Birgé 2011).

Jane Williams-Hogan reminds us, quoting art historian Abraham A. Davidson (1935–2011), that Swedenborg did not offer “aesthetic prescriptions.” But she adds that “his writings provide a radically new way of seeing reality,” which includes an “aesthetic judgment” (Williams-Hogan 2012:107–08; see Davidson 1996:131). There is no “Swedenborgian art,” just as there is no “Theosophical art” or “Catholic art.” But there were and are Swedenborgian artists, who were inspired in different way, and with different results, by Swedenborg’s worldview, particularly by his theory of correspondences, to produce an art with deep spiritual implications.

IMAGES**

** All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

Image #1: Portrait of Emanuel Swedenborg, by non-Swedenborgian Swedish artist Carl Frederik von Breda (1759–1818).

Image #2: Jean Delville (1867–1953), Séraphita (1932).

Image #3: Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Contes barbares (1902).

Image #4: The Wayfarers Chapel, Rancho Palos Verdes, California, as depicted in a postcard, circa 1960.

Image #5: John Flaxman (1755–1826), Evil Spirits Thrust Down by a Little Child (date unknown).

Image #6: William Blake (1757–1827), from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790).

Image #7: Joseph Clark (1834–1926), Agar and Ishmael, etching of 1862 corresponding to the painting of 1860.

Image #8: Hiram Powers (1805–1873), Proserpine (1844)

Image #9: Dennis Duckworth (1911–2003). The Pulpit—The Tedium of Perpetual Worship (ca. 1940). The painting is based on Swedenborg’s True Christian Religion § 737: in the afterlife, some religionists who believed that eternal joy will consist in hearing endless pious sermons will discover that this is in fact extremely boring.

Image #10: George Inness (1825–1894), The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1867).

Image #11: Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847–1919), Moonlight (1885–1889).

Image #12: Robert Carpenter Spencer (1879–1931), The Evangelist (ca. 1918–1919).

Image #13: Bryn Athyn Cathedral, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania.

Image #14: Jessie Willcox Smith (1863–1935), cover for The Jessie Willcox Smith Mother Goose (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1914).

Image #15: Jean-Jacques Gailliard (1890–1976), Mémorable Swedenborg (date unknown).

Image #16: Nishan Yardumian (1947–1986), Annunciation to the Shepherds (1977).

REFERENCES

Alt, Gordon J., Maren Strange, and Victoria Thorson. 1985. In Search of Motion: John Cavanaugh, Sculptor, 1921 to 1985. Bibliography/Catalogue Raisonné. Washington DC: The John Cavanaugh Foundation.

Ambrosini, Lynne D., and Rebecca A.G. Reynolds. 2007. Hiram Powers: Genius in Marble. Cincinnati, Ohio: Taft Museum of Art.

Ashton, Dore. 2009. “Oral History Interview with Lee Bontecou, 2009, January 10.” Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Accessed from https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral–history–interview–lee–bontecou–15647 on 23 September 2019.

Bayley, Jonathan. 1884. New Church Worthies, or Early but Little-Known Disciples of the Lord in Diffusing the Truths of the New Church. London: James Speirs.

Bellin, Harvey F., and Darrell Ruhl, eds. 1985. Blake and Swedenborg: Opposition is True Friendship. The Sources of William Blake’s Arts in the Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. New York: Swedenborg Foundation.

Birgé, Jean-Jacques. 2011. “L’Europe des Esprits ou la fascination de l’occulte, 1750-1950.” Drame.org, November 2. Accessed from http://www.drame.org/blog/index.php?2011/11/02/2161-leurope-des-esprits-ou-la-fascination-de-l-occulte-1750-1950 on 24 September 2019.

Carlsund, Otto G. 1940. Oskar Bergman: En Studie. Stockholm: Fritzes Kungl Hovbokhandel.

Carter, Alice A. 2002. The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love. New York: H.N. Abrams.

Clerbois, Sébastien. 2013. “Jean–Jacques Gailliard (1890–1976) as a ‘Swedenborgian’ Painter: A Forgotten Avant–Garde Heritage in the Highest Ranks of Sacred Art?” Revue de l’histoire des religions 230:85–111.

Colbert, Charles. 2011. Haunted Visions: Spiritualism and the American Art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Davidson, Abraham A. 1996. Ralph Albert Blakelock. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Deck, Raymond Henry, Jr. 1978. “Blake and Swedenborg.” Ph.D. dissertation. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University.

Dillenberger, Jane. 1979. “Between Faith and Doubt: Subjects for Meditation.” Pp. 115–27 in Perceptions and Evocations: The Art of Elihu Vedder, by Regina Soria, Joshua Charles Taylor, Jane Dillenberger, and Richard Murray, Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Dillenberger, Jane, and Joshua C. Taylor. 1972. The Hand and the Spirit: Religious Art in America, 1700–1900. Berkeley: University Art Museum, University of California.

Gabay, Alfred J. 2005. The Covert Enlightenment: Eighteenth Century Counterculture and Its Aftermath. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Swedenborg Foundation Press.

Galliard, Jacques, and James Ensor. 1955. Vie de Swedenborg. Douze linogravures de Jean Jacques Gailliard et texte de James Ensor. Bruxelles: Dutilleul.

Galvin, Eric. 2016. Joseph Clark: A Popular Victorian Artist and His World. Wells, Somerset: Portway Publishing.

Glencairn Museum News. 2018. “‘A Window to the Soul: Nishan Yardumian’s Biblical Art.’” Glencairn Museum News 4, May 9. Accessed from https://glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2018/5/7/a-window-to-the-soul-nishan-yardumians-biblical-art on 23 September 2019.

Glencairn Museum News. 2017. “‘Five Artists Inspired by the Writings of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772).’” Glencairn Museum News 6, June 1. Accessed from https://glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2017/5/31/five-artists-inspired-by-the-writings-of-emanuel-swedenborg-1688-1772 on 23 September 2019.

Glencairn Museum News. 2013. “‘The Way of the Cross: Sculptures by Thorsten Sigstedt.’” Glencairn Museum News 9, September 25. Accessed from https://glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/september-2013-the-way-of-the-cross-sculptures-by-thorsten-s.html on 24 September 2019.

Glenn, E. Bruce. 2011. Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church. Second Edition. Bryn Athyn, PA: Bryn Athyn Church.

Gyllenhaal, Ed. 2015. “Swedenborg in Lincoln Park: Adolf Jonsson’s 1924 Bust of Emanuel Swedenborg and Its Cultural Antecedents.” The New Philosophy 118:201–40.

Gyllenhaal, Ed, and Kirsten Gyllenhaal. 2007. “Nativity Scenes by Winfred S. Hyatt (1929).” New Church History Fun Facts, November 29. Accessed from http://www.newchurchhistory.org/funfacts/index9fa1.html?p=230 on 24 September 2019.

Gyllenhaal, Martha. 2014. “The Art of Philippe Smit.” Bryn Athyn, PA: Bryn Athyn College.

Gyllenhaal, Martha. 1996. “John Flaxman’s Illustrations to Swedenborg’s Arcana Cœlestia.” Studia Swedenborgiana 9:1–71.

Gyllenhaal, Martha. 1994. “John Flaxman’s Illustrations to Swedenborg’s Arcana Cœlestia.” M.A. Thesis. Philadelphia: Temple University.

Gyllenhaal, Martha, Robert W. Gladish, Dean W. Holmes, and Kurt R. Rosenquist. 1988. New Light: Ten Artists Inspired by Emanuel Swedenborg. Bryn Athyn, PA: Glencairn Museum.

Hallengren, Anders. 2013. “E Pluribus Unum: Mauritian Reflections.” The Messenger (Swedenborgian Church of North America) 235:1, 20–23.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2014. “Zöllner’s Knot: Jean Delville (1867–1953), Theosophy, and the Fourth Dimension.” Theosophical History: A Quarterly Journal of Research XVII:84–118.

Janson, Horst Waldemar. 1988. “Psyche in Stone: The Influence of Swedenborg on Funerary Art.” Pp. 115-26 in Emanuel Swedenborg: A Continuing Vision, edited by Robin Larsen, Stephen Larsen, James F. Lawrence and William Ross Woofenden. New York: Swedenborg Foundation.

Jolly, Robert. 1986. “George Inness’s Swedenborgian Dimension.” Southeastern College Art Conference Review 11:14–22.

Lines, Richard. 2012. A History of the Swedenborg Society 1810–2010. London: South Vale Press.

Lines, Richard. 2004. “Swedenborgian Ideas in the Poetry of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning.” Pp. 23-44 in In Search of the Absolute: Essays on Swedenborg and Literature, edited by Stephen McNeilly. London: The Swedenborg Society.

Kazokas, Genovaitė. 2009. Musical Paintings: Life and Work of M.K. Čiurlionis (1875–1911). Vilnius: Logotipas.

Kokkinen, Nina. 2013. “Hugo Simberg’s Art and the Widening Perspective into Swedenborg’s Ideas.” Pp. 246-66 in Emanuel Swedenborg—Exploring a “World Memory”: Context, Content, Contribution, edited by Karl Grandin. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Center for History of Science.

Lamouliatte, Helena. 2016. “Andrew Wyeth and the Wyeth Tradition, or ‘the Anxiety of Influence.’” Angles: French Perspectives on the Anglophone World, July 20. Accessed from http://angles.saesfrance.org/index.php?id=654 on 21 September 2019.

Lawton Smith, Elise. 2002. Evelyn Pickering De Morgan and the Allegorical Body. Lanham (Maryland) and Plymouth (UK): Farleigh Dickinson University Press and Rowman & Littlefield.

Librizzi, Jane. 2012. “Nothing by Chance: Villa Khnopff.” The Blue Lantern, February 20. Accessed from http://thebluelantern.blogspot.com/2012/02/nothing-by-chance-villa-khnopff.html on 23 September 2019.

Maddison, Anna Francesca. 2013. “Conjugial Love and the Afterlife: New Readings of Selected Works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in the Context of Swedenborgian-Spiritualism.” Ph.D. Dissertation. Ormskirk, Lancashire, England: Edge Hill University.

Meister, Maureen. 2003. Architecture and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Boston:

Harvard’s H. Langford Warren. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Mousse Magazine. 2011. “Pablo Sigg at LTD Los Angeles.” Accessed from http://moussemagazine.it/pablo–sigg–at–ltd–los–angeles/ on 23 September 2019.

Neely, Kent. 1986. “Review of The Angels of Swedenborg by Ping Chong; A Country Doctor by Len Jenkin.” Theatre Journal 38:215–17.

Ohge, Christopher. 2014. “‘Lest We Get Too Transcendental’: Christopher Pearse Cranch’s Changes of Mind in ‘Journal. 1839.’” Scholarly Editing: The Annual of the Association for Documentary Editing 35:1–29.

Pasquine, Ruth. 2000. “The Politics of Redemption: Dynamic Symmetry, Theosophy, and Swedenborgianism in the Art of Emil Bisttram (1895–1976).” Ph.D. dissertation. New York: The City University of New York.

Peterson, Brian H. 2004. The Cities, the Towns, the Crowds: The Paintings of Robert Spencer. Philadelphia and Doylestown, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press and James A. Michener Art Museum.

Promey, Sally. 1994. “The Ribband of Faith: George Inness, Color Theory, and the Swedenborgian Church.” The American Art Journal 26:44–65.

Rix, Robin. 2003. “William Blake and the Radical Swedenborgians.” Esoterica V:95–137.

Shaull, Warren L., James Parsons, and Larry Bottigheimer [sic: in fact, Boettigheimer]. 2013. Emil James Bisttram, Encaustic Compositions 1936–1947: A Pictorial Monograph with Essays. Salina, KS: G&S Publishing.

Sigstedt, Thorsten. 2001 [1937]. “The Impact of an Encounter with the New Doctrine Proclaimed from The Hague: Thorsten Sigstedt’s Example” (letter by Thorsten Sigstedt dated April 24, 1937). De Hemelse Leer: Magazine Devoted to an Interior Examination of the Last Testament XIII:20–22.

Silver, Ednah C. 1920. Sketches of the New Church in America on a Background of Civic and Social Life. Boston: The Massachusetts New Church Union.

Simpson, Pamela H. 2007. “Caroline Shawk Brooks: The ‘Centennial Butter Sculptress.’” Woman’s Art Journal 28:29–36.

Skinner, Alice Blackmer. 2011. Stay by Me, Roses: The Life of American Artist, Alice Archer Sewall James, 1870–1955. West Chester, PA: Swedenborg Foundation Press.

Sorgenfrei, Simon. 2019. “The Great Aesthetic Inspiration: On Ivan Aguéli’s Reading of Swedenborg.” Religion and the Arts 23:1–25.

Steinberg, Norma S. 1995. “Munch in Color.” Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin 3:7–54.

Swedenborg Church North America. 2017. “Early Swedenborgianism in America.” Accessed from https://swedenborg.org/beliefs/history/early–history–in–america/ on 21 September 2019.

Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco. 2019 [last updated]. “Origin of the Swedenborgian Church of San Francisco.” Accessed from http://216.119.98.92/tour/tour.asp on 24 September 2019.

Taylor, Joshua C. 1957. William Page: The American Titian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tomkins, Calvin. 2003. “Missing in Action.” The New Yorker, August 4, 36–42.

Trapp, Kenneth R. 1982. “To Beautify the Useful: Benn Pitman and the Women’s Woodcarving Movement in Cincinnati in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Pp. 174-92 in Victorian Furniture: Essays from a Victorian Society Autumn Symposium, edited by Kenneth L. Ames. Philadelphia: Victorian Society in America.

Vedder, Elihu. 1910. The Digressions of V: Written for His Own Fun and That of His Friends. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Vincent, Glyn. 2003. The Unknown Night: The Genius and Madness of R.A. Blakelock, an American Painter. New York: Grove Press.

Westman, Lars. 1997. X-et och Saltsjöbaden. Borås, Sweden: Carlsson Bokförlag.

Williams-Hogan, Jane. 2016. “Influence of Emanuel Swedenborg’s Religious Writings on Three Visual Artists.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 19:119–44.

Williams-Hogan, Jane. 2012. “Emanuel Swedenborg’s Aesthetic Philosophy and Its Impact on Nineteenth-Century American Art.” Toronto Journal of Theology 28:105–24.

Zuber, Devin. 2011. “‘For the Beauty of the Earth’: Sunday Message for the San Francisco Swedenborgian Church, 06/11/2011.” Accessed from http://geewhizlabs.com/swedenborg/Sermons/LaySermons/20110612-DZ-ForTheBeautyOfTheEarth.pdf on 24 September 2019.

Publication Date:

27 September 2019

became a rabbi and a Torah educator, and in 1988 was employed by Arakhim, an adult education institution teaching Judaism mostly to irreligious Israelis. Successful in Judaic outreach, he started his own yeshiva and, eventually, his own Hasidic group thus becoming the Rebbe of Lev Tahor. [Image at right]

became a rabbi and a Torah educator, and in 1988 was employed by Arakhim, an adult education institution teaching Judaism mostly to irreligious Israelis. Successful in Judaic outreach, he started his own yeshiva and, eventually, his own Hasidic group thus becoming the Rebbe of Lev Tahor. [Image at right] and expand his community in Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, Quebec, a small town about a hundred kilometers northwest of Montreal. [Image at right]

and expand his community in Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, Quebec, a small town about a hundred kilometers northwest of Montreal. [Image at right] using it exclusively for prayer and Torah study, but insist on speaking Yiddish among themselves, or, at least, before they master Yiddish, the language of their respective non-Jewish milieu. [Image at right]

using it exclusively for prayer and Torah study, but insist on speaking Yiddish among themselves, or, at least, before they master Yiddish, the language of their respective non-Jewish milieu. [Image at right] take credit for initiating this practice and for manufacturing these capes but not for the extreme gender separation enforced among Lev Tahor members. [Image at right] Unlike other Haredi groups, Lev Tahor boys are encouraged to do horticultural work, take care of vegetable gardens, and do other chores of maintaining the community grounds.

take credit for initiating this practice and for manufacturing these capes but not for the extreme gender separation enforced among Lev Tahor members. [Image at right] Unlike other Haredi groups, Lev Tahor boys are encouraged to do horticultural work, take care of vegetable gardens, and do other chores of maintaining the community grounds. made him and Lev Tahor in general attractive to inquisitive minds in search of uncompromising consistency. Focusing on asceticism, long prayers and meditation, [Image at right] Lev Tahor draws in spiritually alert Jews rather than those in search of reassuring comfort. Reportedly, every member has to sign an oath of allegiance to the Rebbe before joining the community (“More on” 2017). This practice is rather rare among Hasidic groups.

made him and Lev Tahor in general attractive to inquisitive minds in search of uncompromising consistency. Focusing on asceticism, long prayers and meditation, [Image at right] Lev Tahor draws in spiritually alert Jews rather than those in search of reassuring comfort. Reportedly, every member has to sign an oath of allegiance to the Rebbe before joining the community (“More on” 2017). This practice is rather rare among Hasidic groups. became impressed by Lev Tahor and authentically joined it, eventually becoming a second in command in the community. [Image at right] In view of the attention Israel’s security agencies paid to the community, the campaign likely began when the community was domiciled in Israel in the late 1980s.

became impressed by Lev Tahor and authentically joined it, eventually becoming a second in command in the community. [Image at right] In view of the attention Israel’s security agencies paid to the community, the campaign likely began when the community was domiciled in Israel in the late 1980s. religious subjects to the exclusion of much of the general curriculum. [Image at right] However, it was only in the case of Lev Tahor that child protection agencies demanded to remove children from the parental homes.

religious subjects to the exclusion of much of the general curriculum. [Image at right] However, it was only in the case of Lev Tahor that child protection agencies demanded to remove children from the parental homes. who treated the case of Lev Tahor after they moved from Quebec affirmed that what was at issue was perpetuation of the group through its children (Forte 2014). [Image at right]

who treated the case of Lev Tahor after they moved from Quebec affirmed that what was at issue was perpetuation of the group through its children (Forte 2014). [Image at right]

headdresses, and wigwams. Here we see a Tauren student sitting at the feet of arch druid Hamuul Runetotem, on the Elder Rise at the Tauren city of Thunder Bluff. [Image at right]

headdresses, and wigwams. Here we see a Tauren student sitting at the feet of arch druid Hamuul Runetotem, on the Elder Rise at the Tauren city of Thunder Bluff. [Image at right] Moonrage will be expecting you. I have poured the phial of water you brought to me into this vessel to bring to him… You will find him at the moonwell in Dolanaar.” Corithras offers further instruction: [Image at right] “First, let me tell you more of the task you must complete. The druids in Darnassus use the water of the moonwells of Teldrassil, and their moonwell must be replenished from time to time. Using these specially crafted phials, you can collect the water of the moonwells.”

Moonrage will be expecting you. I have poured the phial of water you brought to me into this vessel to bring to him… You will find him at the moonwell in Dolanaar.” Corithras offers further instruction: [Image at right] “First, let me tell you more of the task you must complete. The druids in Darnassus use the water of the moonwells of Teldrassil, and their moonwell must be replenished from time to time. Using these specially crafted phials, you can collect the water of the moonwells.” organization that guides all druids regardless of race, most visibly since the Cataclysm expansion. The image below [Image at right] shows an ordinary Night Elf standing on the balcony of the Temple of the Moon, between Malfurion Stormrage, the historic founder of the druids, and Tyrande Whisperwind, whom he married during the Cataclysm.

organization that guides all druids regardless of race, most visibly since the Cataclysm expansion. The image below [Image at right] shows an ordinary Night Elf standing on the balcony of the Temple of the Moon, between Malfurion Stormrage, the historic founder of the druids, and Tyrande Whisperwind, whom he married during the Cataclysm. normal Night Elves, one or another of them may criticize the avatar’s choice of that abnormal class. Not so for demon hunters among the Blood Elves, one of whom is shown here [Image at right].

normal Night Elves, one or another of them may criticize the avatar’s choice of that abnormal class. Not so for demon hunters among the Blood Elves, one of whom is shown here [Image at right].

non-members of Shincheonji, was incorporated (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018a). One of the main events HWPL organized was the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul, on September 18, 2014. [Image at right] On March 14, 2016, the Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War (DPCW) was proclaimed. In 2017, HWPL was granted special consultative status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Chairman Lee continued to conduct world tours and visiting heads of states, religious leaders, and chiefs of international organizations.

non-members of Shincheonji, was incorporated (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018a). One of the main events HWPL organized was the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul, on September 18, 2014. [Image at right] On March 14, 2016, the Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War (DPCW) was proclaimed. In 2017, HWPL was granted special consultative status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Chairman Lee continued to conduct world tours and visiting heads of states, religious leaders, and chiefs of international organizations. 2019b:3), and the two spiritual seeds reappear through the whole of human history. In the Garden of Eden, the two seeds correspond to God, who is the tree of life, and the devil, who is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Lee 2014: 377–383) [Image at right]

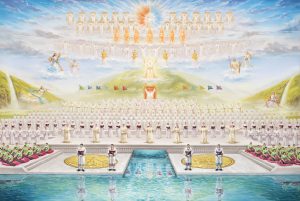

2019b:3), and the two spiritual seeds reappear through the whole of human history. In the Garden of Eden, the two seeds correspond to God, who is the tree of life, and the devil, who is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Lee 2014: 377–383) [Image at right] completed their quotas of 12,000 “priests.” And not all members of Shincheonji will be part of the 144,000. Some will belong to the “Great White Multitude” (Revelation 7:9–10). [Image at right] Satan “will be locked up during the 1,000 years, but he will be set free again when the 1,000 years are over,” although “those inside the holy city [Shincheonji] will not be harmed” (Lee 2014:141). After the 1,000 years and this final temptation, Satan and those corrupted by him will be thrown into hell (Revelation 20:7–10), while those belonging to the seed of God will live forever in the new heaven and new earth.

completed their quotas of 12,000 “priests.” And not all members of Shincheonji will be part of the 144,000. Some will belong to the “Great White Multitude” (Revelation 7:9–10). [Image at right] Satan “will be locked up during the 1,000 years, but he will be set free again when the 1,000 years are over,” although “those inside the holy city [Shincheonji] will not be harmed” (Lee 2014:141). After the 1,000 years and this final temptation, Satan and those corrupted by him will be thrown into hell (Revelation 20:7–10), while those belonging to the seed of God will live forever in the new heaven and new earth.

there are cases when students older than eighty graduated with a very high score (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2018:54–55). [Image at right] The graduation is celebrated in style, as the graduates are regarded as “walking Bibles,” ready even for the harshest missionary fields. Although there are few full-time missionaries, each Zion graduate is expected to devote some time to proselytization activities.

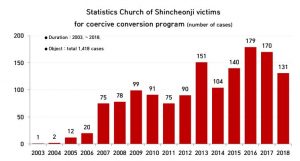

there are cases when students older than eighty graduated with a very high score (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2018:54–55). [Image at right] The graduation is celebrated in style, as the graduates are regarded as “walking Bibles,” ready even for the harshest missionary fields. Although there are few full-time missionaries, each Zion graduate is expected to devote some time to proselytization activities. targeted, the largest number of cases concern Shincheonji. In 2019, Shincheonji reported 1,418 cases of deprogramming since 2003, the year when the practice started in South Korea. [Image at right] Korean deprogrammers are specialized pastors from the mainline churches, most of them Presbyterian. “Cultists” are often kidnapped and imprisoned by their relatives. Two members of Shincheonji, Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa (1959–2007) in 2007 and Ms. Gu Ji-In (1992–2018) in 2018, died in connection with deprogramming attempts. Kim was beaten by her husband with a metal bar, and died on October 11, 2007, from traumatic subdural hemorrhage resulting from blunt force trauma at Dongkang Medical Center in Taehwa-dong, Jung-gu, Ulsan (CAP-LC and others 2019).

targeted, the largest number of cases concern Shincheonji. In 2019, Shincheonji reported 1,418 cases of deprogramming since 2003, the year when the practice started in South Korea. [Image at right] Korean deprogrammers are specialized pastors from the mainline churches, most of them Presbyterian. “Cultists” are often kidnapped and imprisoned by their relatives. Two members of Shincheonji, Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa (1959–2007) in 2007 and Ms. Gu Ji-In (1992–2018) in 2018, died in connection with deprogramming attempts. Kim was beaten by her husband with a metal bar, and died on October 11, 2007, from traumatic subdural hemorrhage resulting from blunt force trauma at Dongkang Medical Center in Taehwa-dong, Jung-gu, Ulsan (CAP-LC and others 2019).