SHINCHEONJI TIMELINE

1931 (September 15): Lee Man Hee was born at Punggak-myeon, Hyeonri-ri, Cheongdo District, North Gyeongsang Province, Korea (now South Korea).

1946: Lee was among the first graduates of Punggak Public Elementary School after the Japanese left Korea.

1950–1953: Lee served in the South Korean Army’s 7th Infantry Division during the Korean War.

1957–1967: Lee participated in the religious activities of the Olive Tree movement.

1967: Having left the Olive Tree, Lee joined another Korean Christian new religious movement, the Tabernacle Temple, in Gwacheon, Gyeonggi Province.

1979–1983: Lee repeatedly wrote letters to the leaders of the Tabernacle Temple, denouncing the corruption in the movement and urging them to repent. As a result, he was threatened and beaten.

1984 (March 14): After leaving the Tabernacle Temple, Lee founded Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony.

1984 (June): The first Shincheonji temple was opened in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea.

1986: Branch churches were established across South Korea. Shincheonji counted some 120 members.

1990 (June): The Zion Christian Mission Center was established in Seoul.

1993: Missionary activity was started abroad. The first Shincheonji National Olympiad was organized in Seoul.

1995: The Twelve Tribes of Shincheonji were formally organized.

1996: The first church in the West was inaugurated in Los Angeles.

1999: Headquarters were moved from Anyang to Gwacheon.

2000: The first church in Europe was inaugurated in Berlin, Germany.

2003: Mannam Volunteer Organization was established.

2003: The first cases of deprogramming of Shincheonji members occurred in South Korea.

2007: Shincheonji membership reached 45,000.

2007 (October 12): Shincheonji member Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa was killed by her husband in connection with her attempted deprogramming.

2012: The first church in Africa was inaugurated in Cape Town, South Africa. Worldwide membership reached 120,000.

2012 (May): Chairman Lee conducted his first World Peace Tour.

2013 (May 25): Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light (HWPL) was established. The Declaration of World Peace was proclaimed.

2014 (September 18): HWPL organized the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul.

2016 (March 14): The Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War (DPCW) was proclaimed in Seoul by HWPL.

2017: HWPL was granted special consultative status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC).

2018 (January 9): Shincheonji member Ms. Gu Ji-in died, eight days after having been hospitalized during her second attempted deprogramming.

2018 (January 28): More than 120,000 gathered in Seoul and other Korean cities to protest deprogramming and the death of Ms. Gu.

2018: Worldwide Shincheonji membership reached 200,000.

2019 (June 20): A statement asking South Korea to put an end to the deprogramming of Shincheonji members was submitted by the NGO CAP-LC at the forty-first session of the United Nations Human Rights Council and published on the United Nations’ Web site. An oral statement followed on July 3.

2020 (February 18): A Shincheonji female member from Daegu, South Korea was hospitalized after a car accident and identified as infected with COVID-19.

2020 (March 2): Shincheonji founder Lee Man Hee held a press conference at which he apologized for possible mistakes and delays in supplying information to the government and promising ongoing full cooperation.

2022 (August 12): The Supreme Court in South Korea upheld the acquittal of Lee Man Hee on charges that he obstructed the government’s response to COVID-19 outbreaks in 2020.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The story of Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony (in short, Shincheonji), as it often happens in the world of religions, may present the same events in different terms, depending on whether they are told from the emic point of view of the members or the secular perspective of outside observers. The emic story, in turn, cannot be ignored by scholars, as it offers crucial elements on the self-perception of the members.

Lee Man Hee [Image at right] was born on September 15, 1931, at Punggak Village, Cheongdo District, North Gyeongsang Province, Korea (now South Korea). In 1946, he was among the first graduates of Punggak Public Elementary School after the Japanese left Korea. Lee did not receive any higher education, but is proud of his level of knowledge and understanding of all books in the Bible, which he attributes to revelations he received from Heaven.

Lee started his life of faith by praying fervently with his grandfather, who was a devout Christian (Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2019a:3–4; Personal interviews 2019). Lee served in the South Korean Army’s 7th Infantry Division during the Korean War and, when the war ended, settled in his native village of Hyeonri-ri, Punggak-Myeon, Gyeongsang Province as a farmer. As he later reported, he started experiencing visions and revelations from divine messengers and from Jesus himself. For ten years, between 1957 and 1967, he participated in the religious activities of the Olive Tree, founded in 1955 by Park Tae-seon (1915–1990), which had a religious village in Sosa District, Bucheon, Gyeonggi Province, and was at that time the most successful Christian new religious movement in Korea, with an estimated 1,500,000 followers. Although repeatedly arrested and tried for fraud, Park managed to achieve what many regarded as a phenomenal success.

During the 1960s, Park’s message [Image at right] evolved into a direction that positioned the Olive Tree far away from traditional Christianity. He started claiming that he was God incarnate and had a position higher than Jesus Christ. The number of members rapidly decreased, and several senior pastors and laypersons left the Olive Tree, including Lee. In 1966, under the leadership of Yoo Jae Yul (b. 1949), seven people gathered on the Cheonggye Mountain, where they remained for 100 days, asking the Spirit of God to teach them. Following what they believed was the will of God, they established the Tabernacle Temple. Lee was among its first members. The seven who gathered with Yoo had not received a formal theological education, but their sermons appeared as persuasive to many who gathered around the Tabernacle Temple. However, corruption and divisions soon developed. Yoo was arrested for fraud. In first degree, in 1976, he was sentenced to five years in prison, but his sentence was shortened to two and a half years with four years probation on appeal (Dong-A Ilbo 1976; Kyunghyang Shinmun 1976).

Giving voice to many members, Lee wrote to the seven denouncing the corruption prevailing in the Temple and calling them to repent. As a result, he was repeatedly threatened and beaten, until he gave up his attempts at reforming the Temple. The Tabernacle Temple, in the meantime, had collapsed.

In 1980, when General Chun Doo-hwan (b. 1931) led a military coup and became President of South Korea, the government launched an anti-cult campaign known as the “religious purification policy” (part of a broader program of “society purification”), and promoted an institution called the Stewardship Education Center, which was introduced in the mainline Christian churches with the aim of unifying their action against the “cults.” In order to avoid the consequences of the anti-cult campaign, Oh Pyeong Ho, an evangelist of the Tabernacle who had a certificate as pastor from the Presbyterian Church, was appointed as the new head of the Tabernacle, replacing Yoo. Oh introduced the Stewardship Education Center into the Tabernacle, which eventually caused the whole of the Tabernacle to merge into the Presbyterian Church, with all its members and assets. Yoo willingly gave up his position as leader of the Tabernacle, and eventually left for the United States in the late 1980s, to study theology there and escape dangerous accusations of being a “cult” leader by the Korean authoritarian government.

Lee continued to visit the Tabernacle Temple when the latter was in the process of joining the Presbyterian Church. He denounced the corruption prevailing in the Temple to its members. Having listened to his testimony, several members came out of the Temple and followed Lee. With them, Lee founded his own separate organization, Shincheonji (“New Heaven and New Earth”) on March 14, 1984. Since then, Lee continued to expose the corruption of the Temple and what he believed to be the destructive role performed by the Stewardship Education Center. Finally, the Stewardship Education Center closed its doors in 1990.

All these events, according to Shincheonji, were not coincidental, and represented the fulfillment of key prophecies in the Book of Revelation (Lee 2014:176–278). The Cheonggye Mountain in Gwacheon, Shincheonji argues, is the location where these prophecies were physically fulfilled, and for this reason God commanded Lee to join the Tabernacle Temple. As foretold in the Book of Revelation, first seven stars (Revelation 1–3: the seven leaders of the Tabernacle, whose representative was Yoo) appeared, then the heretic “Nicolaites” (Revelation 2:6 and 15: those in the Tabernacle Temple who corrupted the doctrine), seven destroyers (the pastors of the Stewardship Education Center, or the destroyers of the Tabernacle from outside) and a “chief destroyer” (Revelation 13: Oh Pyeong Ho, the destroyer of the Tabernacle from inside). Finally, the “one who overcomes” manifested himself (Revelation 2–3: Lee), fought and was victorious over the Nicolaites and the chief destroyer, and became the “promised pastor of the New Testament” Jesus had announced. As the time when the new heaven and the new earth (Shincheonji) were created, 1984 according to the movement also represents the year when the universe completed its orbit and returned to its point of origin (see Kim and Bang 2019:212).

The first temple of Shincheonji was opened in June 1984 in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. [Image at right] The beginnings of the new church were not easy. Branch churches were opened between 1984 and 1986 in Busan (now Busan Metropolitan City), Gwangju (now a Metropolitan City, then in South Jeolla Province), Cheonan (South Chungcheong Province), Daejeon (now a Metropolitan City, then in South Chungcheong Province) and in the Seongbuk district of Seoul. However, the total membership in 1986 did not exceed 120 (Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2019a:8).

A key event for the expansion of Shincheonji was the establishment of Zion Christian Mission Center in Seoul in June 1990. Members started being prepared through courses and exams. The first graduation ceremony, in 1991, involved twelve graduates. In South Korea, the work progressed through the territorial division of the members into Twelve Tribes, formally established in 1995. The South Korean tribes were also assigned responsibility for missions abroad, which led to the inauguration of the first church in a Western country in 1996, in Los Angeles, the first in Europe, in Berlin, in 2000, the first in

Australia, in Sydney, in 2009, and the first in Africa, in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2012.

In 1999, the headquarters were moved from Anyang to Gwacheon, [Image at right] an area with great spiritual and prophetic significance in Shincheonji’s theology. Shincheonji became also known to the public through the activities of the Shincheonji Mannam Volunteer Organization (established in 2003) and the Shincheonji National Olympiads, started in 1993. By 2007, membership had reached 45,000, and the growth accelerated in subsequent years. According to the movement’s own statistics, there were 120,000 members in 2012, 140,000 in 2014, 170,000 in 2016, and 200,000 in 2018 (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2019a:8).

This growth could not go unnoticed from mainline Christian churches, particularly because most new members of Shincheonji were converted from among their flocks. They started increasingly vocal campaigns against Shincheonji, and 2003 saw the first cases of deprogramming (see below, under “Issues/Challenges.”)

Controversies, however, did not stop Shincheonji’s growth, nor the development of its peace and humanitarian activities. In May 2012, Chairman Lee conducted his first World Peace Tour. On May 25, 2013, he proclaimed a “Declaration of World Peace,” and Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light (HWPL), an NGO also including  non-members of Shincheonji, was incorporated (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018a). One of the main events HWPL organized was the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul, on September 18, 2014. [Image at right] On March 14, 2016, the Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War (DPCW) was proclaimed. In 2017, HWPL was granted special consultative status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Chairman Lee continued to conduct world tours and visiting heads of states, religious leaders, and chiefs of international organizations.

non-members of Shincheonji, was incorporated (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018a). One of the main events HWPL organized was the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul, on September 18, 2014. [Image at right] On March 14, 2016, the Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War (DPCW) was proclaimed. In 2017, HWPL was granted special consultative status at the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Chairman Lee continued to conduct world tours and visiting heads of states, religious leaders, and chiefs of international organizations.

For several years, he was accompanied in his tours by Ms. Kim Nam Hee, a close disciple who critics argued may become his “successor” in leading the movement. Shincheonji, however, dismissed these as mere rumors, and stated that there are no projects for electing a successor of Chairman Lee. In fact, it seems it was Ms. Kim herself who was fueling the rumors. When it became clear that Shincheonji would not accept her as leader or “successor,” Ms. Kim started creating her own splinter group, which met with limited success. She was expelled from Shincheonji in January 2018, and she had to face a trial at the Seoul Central District Court on charges of embezzling 1,400,000,000 won from the Shincheonji-owned SMV Broadcasting and occupying the broadcasting station by force. On July 26, 2019, the Seoul Central District Court sentenced her to two years in prison, with three years of probation, for embezzlement. Some congregation members of Shincheonji also accused her of having fraudulently collected 16,000,000,000 won from church devotees.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Shincheonji insists that, strictly speaking, it does not have a “doctrine,” as doctrines are created by humans while Shincheonji’s teachings are all found in the Bible. The Bible is interpreted allegorically and through the method historians of Christianity call “typology,” where events of the Old Testament are considered as “types” to which parallel “antitypes” correspond in the New Testament. Shincheonji believes that, although the Bible records historical facts, prophecies are expressed through parables. These prophecies are the promises that will be fulfilled in the future. Shincheonji teaches that, when the prophecies are physically fulfilled, the true meaning of the parables can be understood (Shincheonji 2019b:8). For example, the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil in the Garden of Eden were not real trees but symbols referring to two types of pastors and spirits working with them, coming respectively from God and Satan.

Regarding the content, the Bible according to Shincheonji is divided into history, moral instruction, prophecy, and fulfillment. Shincheonji teaches that promised future events in the Bible are announced in prophecies, and these prophecies are presented in parables. When the events develop according to the prophecies, the true meaning of the parables becomes known. According to Shincheonji, there is a consistency between the Old and the New Testament. The prophecies in the Old Testament were fulfilled during Jesus’ first coming, and the prophecies of the New Testament are fulfilled during the Second Coming. The Second Coming is today, and the fulfillment of the New Testament prophecies is Shincheonji itself.

Shincheonji believes that God created both the spiritual and the physical realm. Because in the spiritual realm Satan sinned and separated from God, in the physical realm two seeds, the seed of God and the seed of Satan, were sowed in the heart of humans (Lee 2014:289–304). “The parable of the two seeds [Matthew 13:24–30] is the first parable we should understand out of all the parables Jesus told” (Shincheonji Church of Jesus  2019b:3), and the two spiritual seeds reappear through the whole of human history. In the Garden of Eden, the two seeds correspond to God, who is the tree of life, and the devil, who is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Lee 2014: 377–383) [Image at right]

2019b:3), and the two spiritual seeds reappear through the whole of human history. In the Garden of Eden, the two seeds correspond to God, who is the tree of life, and the devil, who is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Lee 2014: 377–383) [Image at right]

In Daniel 4, the evil King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon is also described as a tree, and represents the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, while God’s chosen people represents the tree of life (Lee 2014: 379–380). In the Gospels, Jesus is the tree of life, the true vine (John 15:1–5), and the Pharisees are the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

In the Lord’s Prayer, whose interpretation is also crucial for Shincheonji (Lee 2014:314–23), Christians ask God that “his will be done on earth as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10). God’s will is done in heaven, but after Adam’s sin, it was not done on earth. God acted on earth for the restoration of his will through several providential figures or “pastors,” including Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Joshua. A scheme of salvation (through a covenant with God) after betrayal and destruction was repeated throughout the different eras. Among the people God chooses, some betray and destroy his covenant until a new covenant is fulfilled (Lee 2014:55–56).

Shincheonji views the Bible as a succession of covenants between God and groups identified as the “recipients” of each covenant. The covenant God established with the Israelites in the era of the Old Testament was not faithfully kept by the recipients. God thus changed the recipients of the covenant, substituting the Physical Israelites with the Spiritual Israelites (i.e. the Christians) in the new covenant that was established by Jesus. Today, Christians need to keep the new covenant made with Jesus’ blood (Luke 22:14-20) and join the New Spiritual Israel.

Jesus saved humans from their sins by carrying the cross (Matthew 1:21). God’s spirit came and dwelt with Jesus. At the first coming of Jesus, the Physical Israel came to an end and was replaced by the Spiritual Israel. However, Jesus was betrayed by Judas Iscariot (just as one of the Twelve Tribes, Dan, had betrayed the Physical Israel), and, after Jesus left this earth and ascended to heaven, his message was gradually betrayed by the Catholic and Protestant churches. Shincheonji teaches that the New Testament and the Book of Revelation prophesy that a “promised pastor” will come, overcome the false pastors representing the group led by Satan (the “Nicolaites” of Revelation 2 and 3), and establish the third Israel, the New Spiritual Israel.

The promised pastor of the New Testament, however, could only appear after a figure, or figures, performing the role of John the Baptist would manifest themselves, and after a new process of betrayal and destruction (2 Thessalonians 2:1–4). Shincheonji teaches that the events prophesied in the Book of Revelation were physically fulfilled in Korea in the twentieth century (Lee 2014:176–278). The role of John the Baptist was performed (at the second coming of Jesus) by the seven messengers of the Tabernacle Temple, the seven lampstands (Revelation 1:20), holding lamps that burned in the night for a time until the promised pastor came. According to Shincheonji, the betrayal prophesied in different books of the New Testament (2 Thessalonians 2:1–4; Matthew 8:11–12; Matthew 24:12), in addition to the Book of Revelation, was fulfilled through the corruption of the Tabernacle Temple, and Oh Pyeong-Ho was the chief destroyer who persuaded many in the Tabernacle to receive the mark of the Beast (Revelation 13), i.e. the false teachings of the mainline Christian churches.

At that time, just when Satan’s Nicolaites had invaded the tabernacle where the seven messengers worked (Revelation 2 and 3), “one who overcomes” appeared, defeated Satan’s pastor, the destroyer, and received authority from God and Jesus as the promised pastor. He received an opened book from an angel coming from Heaven after Jesus had broken the seven seals (Revelation 6 and 8) of the sealed book of Revelation 5, which corresponds to the sealed book mentioned by Isaiah (29:9–12). The scroll is now open, and the promised pastor can testify the words of prophecy recorded in the book and their physical fulfillment.

The promised pastor of the New Testament that Shincheonji announces is Chairman Lee. This teaching is often misunderstood by critics, who claim that Shincheonji regards Chairman Lee as God or Jesus. This is not the case. Chairman Lee is regarded as a man, not as God, although in the last days God works through Chairman Lee, who is the pastor and teacher announced by the prophecies of the New Testament, serves as the “advocate” for humankind, and ushers in the Kingdom of God (Lee 2014:78–85). In John 14:16–17 and 26, the “advocate” is the Holy Spirit. This, Shincheonji teaches, refers to a “spiritual advocate” whom Jesus sends to earth in the last days. However, the “spiritual advocate” works and speaks through a physical advocate (John 14:17), i.e. Chairman Lee.

Having conquered the evil Nicolaites, the promised pastor established the new heaven and new earth (Shincheonji) as the New Spiritual Israel, and restored the Twelve Tribes. From the new Twelve Tribes, 144,000 saints (Revelation 7:2–8 and 14:1–5), the sealed 12,000 from each tribe, will participate in the “first resurrection,” unite with the souls of the martyrs who will descend from Heaven, and reign on earth with Jesus for 1,000 years as priests and kings. The return of the martyrs is not intended as a sort of “possession” of humans by the martyrs’ souls. The martyrs will resurrect in spiritual, heavenly bodies (1 Corinthians 15) and will reign together with the 144,000 saints in a family relationship of sorts.

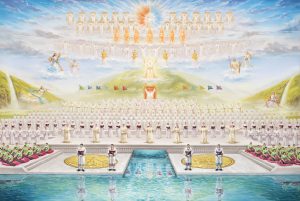

Today, Shincheonji has more than 144,000 members. However, it was anticipated that some would betray and form their own “apostate sects.” Some tribes have not yet  completed their quotas of 12,000 “priests.” And not all members of Shincheonji will be part of the 144,000. Some will belong to the “Great White Multitude” (Revelation 7:9–10). [Image at right] Satan “will be locked up during the 1,000 years, but he will be set free again when the 1,000 years are over,” although “those inside the holy city [Shincheonji] will not be harmed” (Lee 2014:141). After the 1,000 years and this final temptation, Satan and those corrupted by him will be thrown into hell (Revelation 20:7–10), while those belonging to the seed of God will live forever in the new heaven and new earth.

completed their quotas of 12,000 “priests.” And not all members of Shincheonji will be part of the 144,000. Some will belong to the “Great White Multitude” (Revelation 7:9–10). [Image at right] Satan “will be locked up during the 1,000 years, but he will be set free again when the 1,000 years are over,” although “those inside the holy city [Shincheonji] will not be harmed” (Lee 2014:141). After the 1,000 years and this final temptation, Satan and those corrupted by him will be thrown into hell (Revelation 20:7–10), while those belonging to the seed of God will live forever in the new heaven and new earth.

Prophecies, Shincheonji claims, indicate that the promised pastor will not die and will enter the millennial Kingdom of God with his body. However, when asked what would happen if Chairman Lee, who turned eighty-nine in 2019, will die, Shincheonji members simply answer that everything will happen according to the will of God, who until now has fulfilled every promise he made.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Shincheonji’s services are offered twice a week, on Wednesday and Sunday. Shincheonji members kneel during the services, therefore, there are no chairs (except for the elderly and infirm) in their churches. Churches are often located in large buildings where other floors serve different purposes. Devotees wear white shirts (an allusion to Revelation 7 and 14) and signs of different colors corresponding to their affiliation to one or another of the Twelve Tribes (Revelation 21:19–20). The services mostly consist of singing hymns and hearing a sermon, often preached by Chairman Lee himself and broadcast all over the world. The themes come from the entire Bible, but the Book of Revelation is emphasized.

Once a month, a Wednesday meeting includes the sharing of information about Shincheonji’s main activities in the month. Once a year, a General Assembly reports on the year’s activities in Shincheonji and includes a statement about the church’s finances.

Special services are held four times during the year, [Image at right] for Passover (January 14), the Feast of the Tabernacles (July 15), the Feast of Ingathering (September 24), and for commemorating the day when the church was founded in 1984 (March 14).

Shincheonji does not hold events celebrating Christmas or Easter, as it believes they are not appropriate celebration in the time of Jesus’s second coming. Rather than celebrating Jesus’ birth, it is time to greet Jesus at his second coming. Furthermore, instead of celebrating Jesus’ resurrection, it is now time to participate in the “first resurrection.” Shincheonji believes that his teachings reveal the true meaning of Christmas and Easter, making their celebration unnecessary.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Shincheonji regards itself as the only church where one enters not through baptism, but by completing a Bible study course (for which it refers to Revelation 22:14). This is an extremely serious matter for the members. They should follow through Zion Christian Mission Center, across all South Korea and abroad, a course of at least six months (divided into beginner, intermediate, and advanced stages) and prepare for the exams. The courses can now be followed also via Internet, in different languages.

The exams, in written form, are uniformly described by members as difficult and severe. They consist of three questionnaires with a total of 300 questions about the Book of Revelation. It is not uncommon to repeat them several times (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2018). On average, women score better than men. The highest scores for age cohorts are by those in their forties, but  there are cases when students older than eighty graduated with a very high score (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2018:54–55). [Image at right] The graduation is celebrated in style, as the graduates are regarded as “walking Bibles,” ready even for the harshest missionary fields. Although there are few full-time missionaries, each Zion graduate is expected to devote some time to proselytization activities.

there are cases when students older than eighty graduated with a very high score (Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony 2018:54–55). [Image at right] The graduation is celebrated in style, as the graduates are regarded as “walking Bibles,” ready even for the harshest missionary fields. Although there are few full-time missionaries, each Zion graduate is expected to devote some time to proselytization activities.

All the organization of Shincheonji is articulated through the Twelve Tribes, each with a tribe leader: John, Peter, Busan James, Andrew, Thaddeus, Philip, Simon, Bartholomew, Matthew, Matthias, Seoul James, Thomas. The Twelve Tribes oversee 128 churches in twenty-nine countries (seventy-one churches in South Korea, fifty-seven overseas). As mentioned earlier, missions outside South Korea are also distributed among the various Korean tribes.

Many around the world are cooperating with Chairman Lee through HWPL. Opponents of Shincheonji, media, and even academic scholars (Cawley 2019:162–63) claim that HWPL and other organizations are simply fronts for Shincheonji’s proselytization activities. These claims seem, however, incorrect. HWPL promotes international peace through peace education, inter-religious dialogue, “peace walks” and a campaign to “legislate peace” through international law (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018a). Presidents and prime ministers, international organizations dignitaries, and leaders of different religions participate in these initiatives (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018b). While it is correct to say that they increase the visibility of Chairman Lee as a global religious and humanitarian leader, obviously Shincheonji does not expect that these international luminaries will convert to its faith.

Promoting world peace is seen by Shincheonji members as a necessary part, solidly grounded in the Bible and in Jesus’ own teachings, of the efforts to usher in the Kingdom of God in the last days. However, HWPL activities are not limited to Christians, and indeed one of its main efforts is the promotion of the comparative study of the world’s holy scriptures as part of an endeavor to prevent religious conflicts. For this, HWPL is organizing inter-religious dialogues through the HWPL World Alliance of Religions’ Peace (WARP) Offices in over 130 countries.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Through its history, Shincheonji has faced allegations of cultic organization and brainwashing practices and, more recently, allegations of intensifying the spread of COVID-19.

Shincheonji’s rapid growth largely happened by converting members of other Christian churches. They reacted by accusing Shincheonji of “sheep stealing,” “heresy,” and being a “cult” (see e.g. Kim 2016). South Korea is a country where old stereotypes about “cults” survive, promoted by both secular media and mainline Christian churches, particularly those part of the Christian Council of Korea (CCK).

Apart from “heresy,” an accusation liberally traded between Christians since the times of the Apostles, Shincheonji has been accused of dissimulation and “brainwashing.” Indeed, Shincheonji does admit that Christians and others invited to its meetings are not immediately told that the organizer is Shincheonji. The movement justifies this by explaining that opponents of Shincheonji spread derogatory information through seminars organized by CCK churches and media outlets, thus causing a vicious circle. Because of the media slander and CCK propaganda, few would attend events if the name Shincheonji would be mentioned, as the movement is described negatively as problematic to society. In turn, the fact that the name of the church is not immediately advertised is used by critics to claim Shincheonji is a “cult” that practices “dissimulation.” There is also, Shincheonji claims, a Biblical justification for this behavior. Apostle Paul in 1 Thessalonians 5:2 prophesied that at his second coming Jesus will come “as a thief in the night,” which Shincheonji interprets to the effect that the harvesting will be very difficult due to organized opposition, and suggests a cautious approach.

The idea that new religious movements use “brainwashing” has been debunked decades ago by Western scholars of new religious movements (Richardson 2015, 2014, 1996), but is still used by popular media and seems to maintain supporters among Korean mainline Christian churches. Because they were “brainwashed,” opponents of new religious movements claimed in the 20th century in North America and Europe, “cultists” needed to be “deprogrammed,” i.e. kidnapped, confined, and submitted to intensive anti-cult indoctrination (Bromley and Richardson 1983). By the end of the twentieth century, deprogramming had been declared illegal in most Western countries (Richardson 2011). It survived for some years in Japan, until courts there reached the same conclusions. The only democratic country where deprogramming is still widely practiced is Korea.

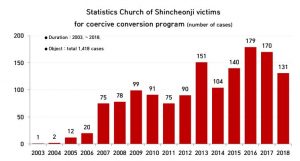

Although other groups (Providence, World Mission Society Church of God) are also  targeted, the largest number of cases concern Shincheonji. In 2019, Shincheonji reported 1,418 cases of deprogramming since 2003, the year when the practice started in South Korea. [Image at right] Korean deprogrammers are specialized pastors from the mainline churches, most of them Presbyterian. “Cultists” are often kidnapped and imprisoned by their relatives. Two members of Shincheonji, Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa (1959–2007) in 2007 and Ms. Gu Ji-In (1992–2018) in 2018, died in connection with deprogramming attempts. Kim was beaten by her husband with a metal bar, and died on October 11, 2007, from traumatic subdural hemorrhage resulting from blunt force trauma at Dongkang Medical Center in Taehwa-dong, Jung-gu, Ulsan (CAP-LC and others 2019).

targeted, the largest number of cases concern Shincheonji. In 2019, Shincheonji reported 1,418 cases of deprogramming since 2003, the year when the practice started in South Korea. [Image at right] Korean deprogrammers are specialized pastors from the mainline churches, most of them Presbyterian. “Cultists” are often kidnapped and imprisoned by their relatives. Two members of Shincheonji, Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa (1959–2007) in 2007 and Ms. Gu Ji-In (1992–2018) in 2018, died in connection with deprogramming attempts. Kim was beaten by her husband with a metal bar, and died on October 11, 2007, from traumatic subdural hemorrhage resulting from blunt force trauma at Dongkang Medical Center in Taehwa-dong, Jung-gu, Ulsan (CAP-LC and others 2019).

For Gu, this was her second deprogramming, after a previous attempt in 2016 had failed, as she only pretended to have been “de-converted” and, once freed from captivity, rejoined Shincheonji. On December 29, 2017, Gu’s parents used as a pretext a family trip to abduct her again. She was taken to a secluded recreational lodge in Hwasun (Jeonnam, South Jeolla Province), where she was held captive. As she threatened to escape, the parents bound and gagged her, causing suffocation. Gu lost her consciousness and was pronounced brain-dead on December 30, 2017. Her heart ceased to beat on January 9, 2018 (Fautré 2019b).

On January 28, 2018, more than 120,000 gathered in Seoul and other Korean cities to protest deprogramming and the death of Ms. Gu. [Image at right] Shincheonji members created a Human Rights Association for Victims of Coercive Conversion Programs (HAC) to fight deprogramming in South Korea. The protests were mentioned in the 2019 U.S. State Department Report on Religious Freedom, including violations of religious freedom in the year 2018 (U.S. Department of State 2019:7). However, there were new cases of deprogramming even after Gu’s death (CAP-LC and others 2019; Fautré 2019a).

On June 20, 2019, a statement asking South Korea to put an end to the deprogramming of Shincheonji members was submitted by the NGO with ECOSOC (Economic and Social Council of the United Nations) special consultative status CAP-LC at the forty-first session of the United Nations Human Rights Council and published on the United Nations’ Web site (CAP-LC 2019b). An oral statement followed on July 3 (CAP-LC 2019a), and a letter of several NGOs to South Korean President Moon Jae-in (CAP-LC and others 2019).

These NGOs claimed that South Korean authorities have not taken adequate actions against the deprogrammers. Relatives who hired the deprogrammers and kidnapped and held captive the victims, and those who used violence, including Ms. Kim Sun-Hwa’s husband (sentenced to ten years in jail) have sometimes been investigated (Ms. Gu’s father is a fugitive from justice at the time of this writing), indicted and found guilty by Korean courts, but the deprogrammers themselves have so far largely escaped punishment. Media and even judges regard deprogramming as a “family matter,” and suing one’s own parents is considered as contrary to Korean traditional ethos. In fact, when victims of deprogramming sue their parents, opponents denounce this as a confirmation that “Shincheonji destroys families,” and end up blaming the victims rather than the perpetrators.

South Korean authorities also seem to be unaware of the fact that the defense that victims submitted “voluntarily” to deprogramming, or even signed (under coercion) statements to that effect, has been dismissed by courts of law in other democratic countries.

Deprogramming is also supported by hate speech going well beyond the normal boundaries of religious controversy and de-humanizing members of Shincheonji, thus justifying and preparing violence against them. Specialized cycles of lectures called “Cult Seminars” have a key role in propagating these forms of hate speech, while “Cult Counseling Offices” and “Heresy Research Centers” operated by some mainline Christian churches and pastors put relatives in touch with the deprogrammers (CAP-LC 2019b). While a reaction by mainline Christian churches against teachings they regard as “heretic” and proselytization techniques perceived as involving dissimulation is understandable, the verbal violence against Shincheonji is often extreme, and may indeed lead to physical violence.

Although the threat of deprogramming is a serious problem for Shincheonji members in South Korea, the international protest against the practice is growing, and it is becoming difficult for Korean authorities to ignore it. On the other hand, both Shincheonji and HWPL continue their growth, confirming that violent opposition, although causing significant distress for members, met with only limited success.

Shincheonji became embroiled in the controversy surrounding the spread of COVID-19 early in 2020. On February 18, a Shincheonji female member from Daegu, South Korea, was hospitalized after a car accident and identified as infected with COVID-19. She was designated as Patient 31, and, before being diagnosed, had attended several functions of Shincheonji. As a result, she became the origin of hundreds of new infection cases, most of them involving fellow members of Shincheonji.

The authorities asked Shincheonji for a full list of its members. It was supplied but included members, not those (called “students” in the movement) who attend Shincheonji churches but have not (yet) become members. When the list of “students” was requested, it was also supplied. Authorities complained that the delay contributed to the spread of the virus, while Shincheonji claimed it was being scapegoated to distract the public attention from the authorities’ own shortcomings in handling the crisis.

Anti-cultists went much further, accusing Shincheonji members of intentionally spread the virus and behaving irresponsibly, trusting that God would protect them from the epidemics. Violence followed. Shincheonji members were beaten and fired from their jobs, and in Ulsan, on February 26, a Shincheonji female member died after falling from a window on the seventh floor of the building where she lived. The incident occurred while her husband, who had a history of violent hostility to her faith and claimed the fall was accidental, was attacking her and trying to compel her to leave Shincheonji.

On March 2, Shincheonji founder Lee Man Hee held a press conference apologizing for possible mistakes and delays in supplying the lists of members, promising full cooperation with the authorities. Meanwhile, the City of Seoul filed a complaint against Lee and other Shincheonji leaders for homicide, claiming the delayed cooperation with the authorities caused the loss of human lives.

The Korean police raided Shincheonji churches and seized the lists of members. After comparing these with the lists supplied by Shincheonji, they concluded that discrepancies were but minor and that the church did not voluntarily submit incomplete or altered lists (Kim 2020). CESNUR and the Belgian NGO Human Rights Without Frontiers published in March 2020 a “White Paper” on Shincheonji and the coronavirus, concluding that the church did commit some mistakes in its handling of the crisis but they did not amount to criminal negligence (Introvigne, Fautré, Šorytė, Amicarelli and Respinti 2020). The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom also expressed concerns that Shincheonji’s religious liberty may be violated in South Korea (USCIRF 2020).

In what may be the final chapter of the government’s case against Lee Man Hee for violating the infectious disease control law, he was acquitted of that charge but was convicted of embezzlement. The court issued a three-year suspended jail term sentence (“South Korea sect” 2021). In 2022, the Supreme Court upheld lower courts’ acquittal of Lee Man-hee of charges that he obstructed the government’s response to COVID-19 outbreaks in 2020 (Yonhap 2022).

The anti-Shincheonji campaign has been fueled by both Christian anti-cult opponents, who have argued for the dissolution of the movement and spread discrediting rumors about it, and international media who have repeated depictions of Shincheonji as the “coronavirus cult.” What effect the crisis will have on Shincheonji future remains to be seen.

IMAGES

Image #1: Chairman Lee interviewed by the author of this profile, Gwacheon, South Korea, June 6, 2019 (in front of the Palace of Peace).

Image #2: Park Tae-seon.

Image #3: The first temple of Shincheonji, opened in June 1984 in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea.

Image #4: Shincheonji headquarters in Gwacheon.

Image #5: A moment of the World Alliance of Religions’ Peace Summit in Seoul, 2014.

Image #6: Teaching aid about the two seeds.

Image #7: An artistic rendering of the New Jerusalem.

Image #8: A Founding Day Shincheonji service (2019).

Image #9: Exams in Seoul (Peter tribe).

Image #10: Graphic showing the number of attempted deprogrammings of Shincheonji members.

Image #11: January 28, 2018 manifestation protesting deprogramming.

REFERENCES

Bromley, David, and James T. Richardson, eds. 1983. The Brainwashing/Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal and Historical Perspectives. New York and Toronto: The Edwin Mellen Press.

CAP-LC (Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience). 2019a. Oral statement. Human Rights Council of the United Nations, Forty-first session, July 3, 2019. Accessed from http://webtv.un.org/search/item4-general-debate-21st-meeting-41st-regular-session-human-rights-council-/6055074714001/?term=&lan=english&cat=Meetings%2FEvents&page=3 [No. 62, 01:55:53], on 14 July 2019.

CAP-LC (Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience). 2019b. “Forcible deprogramming of members of Shincheonji in the Republic of Korea.” Written statement, Human Rights Council of the United Nations, Forty-first session, June 20, 2019. Accessed from https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G19/177/94/pdf/G1917794.pdf?OpenElement on 14 July 2019.

CAP-LC (Coordination des Associations et des Particuliers pour la Liberté de Conscience) and others. 2019. “Forced Conversion in South Korea Should Be Put to an End: An Open Letter to President Moon Jae-in.” Accessed from https://www.eifrf-articles.org/Forced-Conversion-in-South-Korea-Should-Be-Put-to-an-End-An-Open-Letter-to-President-Moon-Jae-in_a234.html on 22 July 2019.

Cawley, Kevin N. 2019. Religious and Philosophical Tradition of Korea. Abingdon, UK and New York: Routledge.

Dong-A Ilbo. 1976 “장막성전 교주에 징역 5년을 선고” (Sentenced to Five Years Imprisonment). March 1.

Fautré, Willy. 2019a. “South Korea: Hyeon-Jeong KIM: 50 days of confinement for forced de-conversion (1).” Human Rights Without Frontiers, August 22. Accessed from https://hrwf.eu/south-korea-hyeon-jeong-kim-50-days-of-confinement-for-forced-de-conversion-1/ on 23 August 2019.

Fautré, Willy. 2019b. “South Korea: A Young Woman Died in an Attempt to Forcibly De-Convert Her in Sequestration Conditions.” Human Rights Without Frontiers, July 8. Accessed from https://hrwf.eu/south-korea-a-young-woman-died-in-an-attempt-to-forcibly-de-convert-her-in-sequestration-conditions/ on 22 August 2019.

Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light. 2018a. Declaration of Peace and Cessation of War White Paper. Seoul: Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light.

Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light. 2018b. Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light 2018. Seoul: Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light.

Introvigne, Massimo, Willy Fautré, Rosita Šorytė, Alessandro Amicarelli and Marco Respinti. 2020. “Shincheonji and coronavirus in South Korea: Sorting Fact from Fiction. A White Paper.” Brussels: CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers. Accessed from https://www.cesnur.org/2020/shincheonji-and-covid.htm on 20 March 2020.

Kim, So-Hyun. 2020. “Shincheonji didn’t lie about membership figures.” The Korea Herald, March 17. Accessed from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200317000667 on 20 March 2020.

Kim, David W., and Bang Won-il. 2019. “Guwonpa, WMSCOG, and Shincheonji: Three Dynamic Grassroots Groups in Contemporary Korean Christian NRM History.” Religions 10:1–18. DOI: 10.3390/rel10030212.

Kim, Young Sang. 2016. “The Shincheonji Religious Movement: A Critical Evaluation.” M.A. Thesis, University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Kyunghyang Shinmun. 1976. “장막성전 교주에 집행유예를 선고” (Leader of Tabernacle Temple Sentenced to Probation), July 10.

Lee, Man Hee, ed. 2018. The True Story of Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light: Peace and Cessation of War. Seoul: Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light.

Lee, Man Hee. 2014. The Creation of Heaven and Earth. Second English edition. Gwacheon, South Korea: Shincheonji Press.

Personal Interviews. 2019. Personal interviews were conducted with members of Shincheonji in Seoul and Gwacheon in March and June 2019, including one with Chairman Lee in Gwacheon on June 6, 2019.

Richardson, James T. 2015. “’Brainwashing’ and Mental Health.” Pp. 210–15 in Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Second Edition, edited by Howard S. Friedman,. New York: Elsevier.

Richardson, James T. 2014. “’Brainwashing’ as Forensic Evidence.” Pp. 77–85 in Handbook of Forensic Sociology and Psychology, edited by Stephen J. Morewitz and Mark L. Goldstein, New York: Springer.

Richardson, James T. 2011. “Deprogramming: From Private Self-Help to Governmental Organized Repression.” Crime, Law and Social Change 55:321–36. DOI 10.1007/s10611-011-9286-5.

Richardson, James T. 1996. “Sociology and the New Religions: ‘Brainwashing,’ the Courts, and Religious Freedom.” Pp. 115–37 in Witnessing for Sociology: Sociologists in Court, edited by Pamela Jenkins and Steve Kroll-Smith. Westport, CT and London: Praeger.

Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony. 2019a. Introduction Materials for Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony. Gwacheon, South Korea: Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony.

Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony. 2019b. Shincheonji Core Doctrines. Gwacheon, South Korea: Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony.

Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony. 2018. Examination for Shincheonji 12 Tribes: Verifying They Are Sealed. Gwacheon, South Korea: Shincheonji Church of Jesus the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony.

“South Korea sect leader cleared of hindering virus effort.” 2021. Yahoo News Australia, January 13. Accessed from https://au.news.yahoo.com/south-korea-sect-leader-cleared-064218607.html on 15 January 2021.

USCIRF (United States Commission on International Religious Freedom). 2020. “The Global Response to the Coronavirus: Impact on Religious Practice and Religious Freedom.” Washington D.C.: USCIRF. Accessed from https://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/2020%20Factsheet%20Covid-19%20and%20FoRB.pdf on 20 March 2020.

U.S. Department of State. 2019. “Republic of Korea 2018 International Religious Freedom Report.” Accessed from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/KOREA-REP-2018-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUS-FREEDOM-REPORT.pdf on 7 July 2019.

Yonhap. 2022. “Supreme Court upholds acquittal of Shincheonji leader.” Korea Herald, August 12. Accessed from https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20220812000335&np=1&mp=1 on 13 August 2022.

Publication Date:

30 August 2019