The Shakers

THE SHAKERS TIMELINE

1747: The Wardley society, from which the Shakers emerged, formed as a distinct group in Manchester, England.

1773: Ann Lee assumed leadership in the group.

1774: Nine Shakers, including Ann Lee, her brother William and her husband Abraham Standerin, sailed to America, following God’s command received by “Mother Ann.”

1776: The first settlement at Niskeyuna, New York was established.

1784: Ann Lee died, following a successful two-year missionary tour of New England. James Whittaker took over as the sect’s leader.

1787: James Whittaker died and was succeeded by Joseph Meacham. Under Meacham, the United Society assumed a communal organization and scattered believers were “gathered” into villages.

1796: Lucy Wright succeeded Meacham as the sect’s leader. She later founded a four-member collective leadership institution, the Ministry.

Late 1700s – early 1800s: Various aspects of Shaker doctrine, ritual and everyday life were codified and institutionalized.

1806–1824: Several villages were established in Kentucky, Ohio and Indiana, following a mission to the west.

1837–c. 1850: The “Era of Manifestations,” a period of intense religious revival swept through Shaker settlements.

Mid-1800s: The United Society reached its peak population of around 4,500, living in more than twenty villages.

Late 1800s: The processes of depopulation, feminization and other forms of decline began and had continued until mid-twentieth century.

1959: With the closing of Hancock, Massachusetts, the last two Shaker villages remained in Canterbury, New Hampshire and Sabbathday Lake, Maine.

1960: Theodore Johnson, a new convert, joined Sabbathday Lake and proceeded to reinvigorate various aspects of Shaker everyday and religious life.

1963: Eldress Emma King of Canterbury, formally the leader of the Society, refused to accept any new converts and urged Sabbathday Lake to do the same. The Maine village disobeyed, which led to a conflict.

1992: The last Shaker sister died at Canterbury, leaving Sabbathday Lake the only surviving Shaker village. Four years earlier, the Central Ministry was dissolved.

2017: Sister Francis Carr, the eldest member of the Sabbathday Lake community, died at eighty-nine. As of this writing, only two Shakers remain: sister June Carpenter and brother Arnold Hadd.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The Shakers, established in the United States as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, should not be confused with Indian Shakers, a syncretic religious movement among Native Americans founded in late nineteenth century by the prophet John Slocum (Wilson 1973:353–64). Their origins go back to England, where, in 1747 in Manchester, James and Jane Wardleys founded a group which was to become the core of Shakerism. The Wardley society was itself a product of two major influences: Quakerism, with its pacifism and the conception of inner light with which God may fill the soul of a believer without the mediation of a church, and the so-called French Prophets. The latter, spiritual leaders of some of the French Protestants (Huguenots) who fled France after the suppression of the anti-Catholic Camisard revolt in the Cevennes region in early eighteenth century, found themselves refugees in various European countries, including England. There, they continued to claim divine revelations which manifested in the form of violent bodily movements, inarticulate sounds and other trans-like phenomena (Garrett 1987). Even though the Manchester group was formed long after the French Prophets became inactive, their memory lived on, partly through the Methodist movement. The Wardley followers had the same faith in direct divine revelation and exhibited similar ecstatic behavior (characteristic also for early, but not mid-eighteenth century Quakerism), which later earned the group the nickname “Shakers,” a derogatory term used by the critics, but happily adopted by the believers themselves.

Ann Lee, the founder of the Shakerism proper, was born in a working-class family in Manchester in 1736. Initially she was, together with members of her family, a rather passive follower of the Wardleys, but towards the late 1760’s, when she began to display her prophetic gifts, she assumed a more prominent role, gradually displacing Wardleys as leaders of the group. Returning from a thirty-day imprisonment in 1773 (for disturbing services of other churches), she announced she had been filled with Christ’s spirit and called herself “Ann the Word.” Next year, having received another revelation, she led a handful of her most devoted followers, including her brother William (plus her husband Abraham Standerin, who never converted) on a trip to America (Cohen 1973:42–47). The journey on board Mariah strengthened the group’s foundational myth, since Lee was believed to have quieted the storm that was threatening to sink the ship.

Once in New York in August 1774, the group initially dispersed, but soon managed to buy a tract of land in Niskeyuna in New York state. In the late 1770s, missionary activity began which yielded a considerable number of converts, especially from among New Light and Free Will Baptists, exhausted and disillusioned after one of the fiery revivals of upstate New York and southern New England. The price of this relative success was high, however: Shakers were met with hostility, beaten, tarred-and-feathered and imprisoned on numerous occasions. This no doubt took its toll on Ann Lee, who died at Niskeyuna in September 1784 (Francis 2000: Part II).

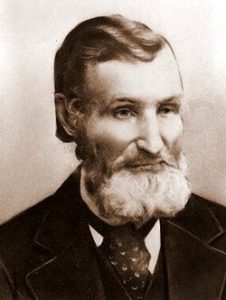

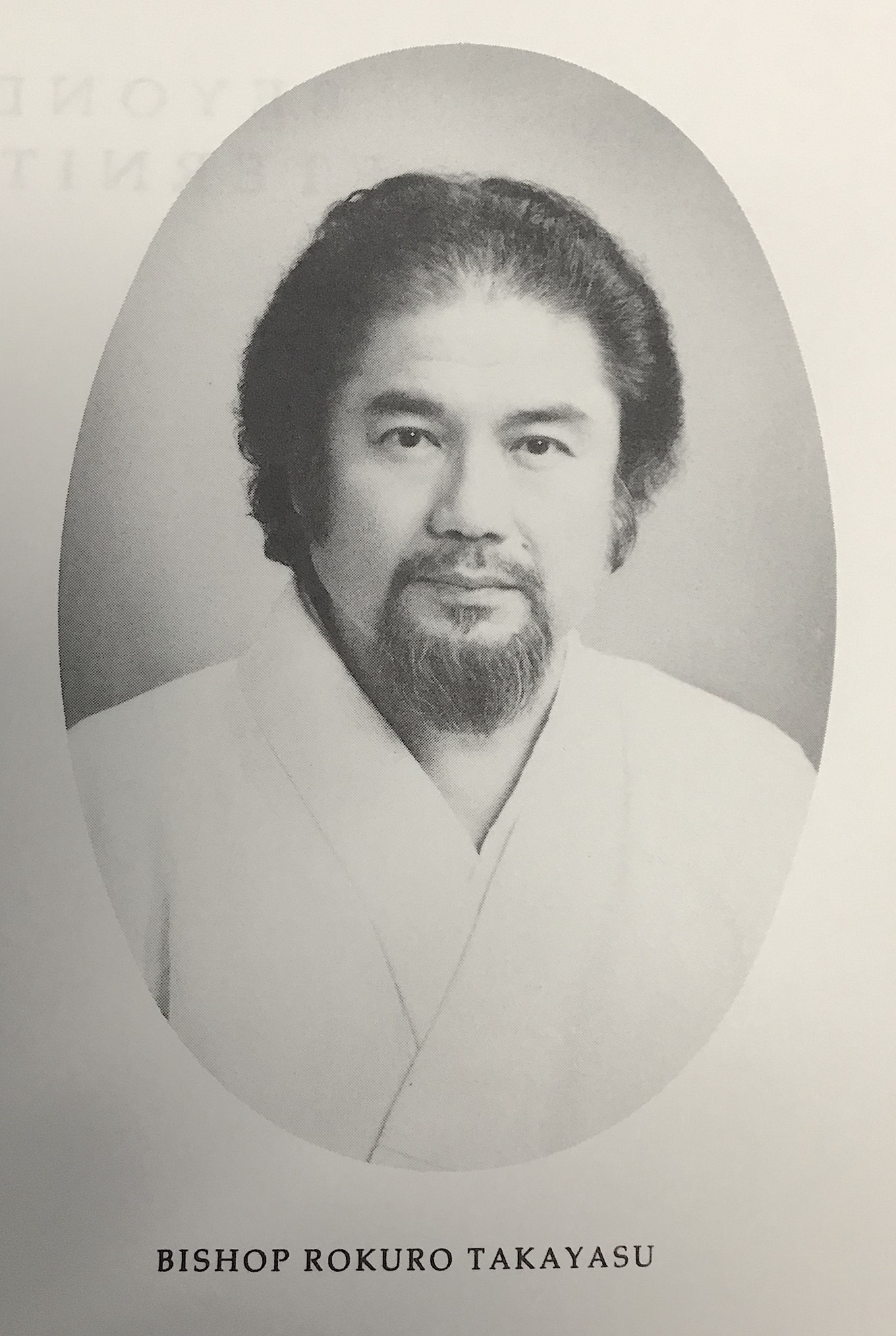

Ann Lee was succeeded by James Whittaker, one of her English followers, who devoted his energies to consolidating the emerging Shaker settlements that resulted from the missionary activities. He died soon, in 1787, and was replaced by Joseph Meacham, [Image at right] the first American-born leader of the Shakers, who, in turn, was succeeded by Lucy Wright in 1796.

Under Meacham and Wright, the Society underwent a process of institutionalization of various aspects of its existence. The members, many of them initially staying with their biological families even after conversion to Shakerism, were obligated to move to the villages and adopt communal lifestyle, grounded in a more and more formalized code of conduct. The doctrine, initially deduced from inspired utterings of the group’s prophetic leaders, was systematized and written down. Standardized communal forms of worships, group dances with fixed steps etc. gradually displaced the spontaneous ecstatic phenomena (without, however, losing entirely its charismatic qualities). Finally, in terms of political organization, the initial individual leadership with charismatic succession mechanisms (e.g. a “battle of gifts” between challengers on the grave of James Whittaker) gave way to collective leadership based on the procedure of cooptation (Potz 2012:382–85).

The first decades of the nineteenth century were also a period of Shakerism’s westward expansion. As a result of a missionary tour in the midst of a revival, as many as seven Shakers villages were established in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio between 1806 and 1824 (Paterwic 2009:xxi).

Towards the middle of the nineteenth century, the social and religious life of Shaker communities became stable and predictable. However, it was not to last for long. In 1837, a group of teenage girls from Niskeyuna (Watervliet) community began receiving revelations. This marked the beginning of the longest period of religious revival in the group’s history (referred to as the Era of Manifestations or Mother Ann’s Work) which lasted, with varying intensity, for more than a decade. Revelations soon spread to all Shaker settlements. They were communicated by various spiritual beings, ranging from God, through Mother Ann and other deceased Shaker leaders, to historical figures who supposedly converted to Shakerism in the afterlife, such as George Washington, Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander the Great. The inspired messages urged Believers to purge themselves from sin, renounce materialism and other temptations of the “world,” and spiritually refresh their faith. They introduced spiritual names for the communities and numerous new ceremonies, such as mock feasts during which the Believers consumed spiritual food such as “Mother’s love in a pulverized form” or “sweeping gift,” when they pretended to cleanse the community of sin with invisible brooms (Andrews and Andrews 1969:25).

The Era of Manifestations lends itself to various interpretations. Sociologically, it served to reinvigorate the faith of the generation which did not experience the original enthusiasm of early Shakerism and might find the daily routine of farm work dull and unappealing. Politically, Manifestations provided a vehicle of empowerment for the underprivileged segments of Shaker communities (the rank-and-file members and especially women and youth) who could now play important social roles as divinely inspired media or “instruments” (Humez 1993:210, 218–19). This occasionally led to power struggles between the leaders, with their official authority, and instruments attempting to subvert it by invoking their charismatic gifts. Ultimately, the leaders prevailed, and the Shaker communities returned to business as usual towards the end of the 1840s (Potz 2012:397–400).

Around this time, Shakerism, strengthened by the influx of disillusioned Millerites, reached its peak population of around 4,000–4,500 members (Murray 1995:35). From this point on, the story in the United Society has been one of steady decline. The trends of depopulation, feminization and the weakening of communal forms of life and worship, initiated in the second half of the nineteenth century, have never been reversed. Communal and celibate lifestyles had become been less and less attractive with so many alternatives opening up in the era of industrialization. Orphans brought up by the group (a major source of new members, given lack of adult converts and Shakers’ celibacy) rarely remained with the group once they reached the age of eighteen. Nor were the Shakers immune to the outside influences. The traditional lifestyle had often yielded to modernizing trends, with emphasis on individualism, rationalism and personal well-being, represented by Frederick Evans, an informal Shaker leader, apologist and reformer from New Lebanon (Stein 1992: Part IV).

In the twentieth century these trends have only been compounded. One by one, Shaker villages were closing when the last members died. Central Ministry, all-female since 1939, moved to Hancock, Massachusetts, and to Canterbury, New Hampshire. Since 1960, with the closing of Hancock, Canterbury and Sabbathday Lake, Maine, were the last two surviving Shaker communities. The two villages soon found themselves in conflict over what is often referred to as the “closing of the covenant”: the refusal by the Canterbury sisters, under the leadership of Eldress Emma King, to accept any new members. Although this did not amount to formally “closing of the covenant” according to Shaker laws (Paterwic 2009:42–43), the group in fact committed what I have termed “institutional suicide,” which means consciously sentenced Shakerism, as a religious group, to extinction (Potz 2009).

Meanwhile, an enthusiastic new convert named Theodore Johnson joined the Sabbathday Lake village. Convinced of the truth of Shakerism, he proceeded energetically to renew various aspects of the community’s life: he wrote on Shaker theology, organized a library, published a magazine, revived some traditional industries and, perhaps most importantly, reintroduced communal worship. Eldress King of Canterbury was strongly against accepting Johnson into the community, but Sabbathday Lake disobeyed, which lead to a protracted conflict. The result was the cutting of payments the Maine community received from the Shaker Central Trust Fund, created to administer assets from the liquidated villages.

In 1992, the Canterbury village was closed. Sabbathday Lake, after brother Johnson’s death in 1986, continued to accept new members, but this did not significantly change the group’s prospects. Today, 272 years after the founding of the group in England and 245 years after its arrival to America, only two Shakers remain: sister June Carpenter, age eighty, and brother Arnold Hadd, age sixty-two.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Shaker beliefs, while derived from Christianity, are in many respects distinct and unorthodox. They strongly emphasize dual, masculine and feminine aspects of one, incorporeal God, often referred to as Eternal Father and Eternal Mother or Holy Mother Wisdom, the Eternal Parents. While, theologically, this position is fairly standard for all Christianity (few theologians would seriously claim that God is male), it obviously goes against culturally embedded patriarchal images of God.

The emphasis on male and female elements of the Godhead leads to similar views on Christology. Christ is the highest spirit which dwelled in Jesus, and, on His Second Coming, revealed its feminine aspect, inhabiting a woman, Ann Lee (Evans 1859:110). But it also dwells in other Believers, and Lee was just the first to receive it. Formally, it may not imply that Mother Ann was the Christ, but this fine distinction was probably lost on most of her followers who simply treated her as the female incarnation of Christ (something that, predictably, aroused a lot of repulsion and hostility, especially in the Puritan New England).

In its view of Jesus, Shaker Christology is, technically, adoptionist: Jesus was not the Christ or God-anointed from his birth, he was only filled with God’s spirit upon his baptism in Jordan (Johnson 1969: 6–7). Symmetrically, Ann Lee was “baptized with, and led by, the same Christ Spirit” (Evans 1859: 83) at some point in her life. Shakers also reject the trinity dogma, regarding it unscriptural. Christ and the Holy Ghost are the highest ranking spiritual entities rather than being identical with God.

An important element of Shaker theology is the doctrine of continuous or continuing revelation, according to which God’s revelation through Old Testament prophets and Evangelists was not final. Instead, God continues to guide his people, speaking to them through prophets and other inspired instruments (Potz 2016: 172–76). The spiritual gifts abundant in the early period, both in England and America, and later during the Era of Manifestations, are an obvious sign of that. As a consequence, since revelation is ongoing, the Bible is not the summation of God’s law. It contains truth, because the authors were inspired, but is not the ultimate and only source of truth (Johnson 1969:10–11).

Finally, Shakers are millenarian, but their millennialism is specific: the thousand-year kingdom on earth, instead of being preceded by cataclysmic events, has already come quietly with the descension of the Christ spirit on Ann Lee. All believers who accepted her teachings and live a Shaker life in Christ spirit, partake in the millennium. This aspect of Shaker doctrine made it particularly attractive for potential converts disappointed in their millenarian expectations aroused by date-fixing prophets of the sort of William Miller (Potz 2016:188–90). As regards the afterlife, Shaker beliefs are fairly similar to Protestant notions: hell and heaven are non-physical states in which the soul is, respectively, separated from or united with God.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

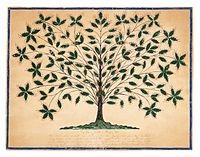

True to their name, Shaker worship was from the very beginning marked with ecstatic practices initiated spontaneously during meetings and interpreted as signs of the operation of the Holy Spirit. Thus, they would shake, tremble, whirl, dance, roll on the floor, run after one’s outstretched hand, laugh, bark, howl, speak in unknown tongues (glossolalia) or prophesy (Morse 1980:68–70). These enthusiastic forms of worship were gradually curbed and  formalized into more conventional services with readings, sermons and group dances, such as the famous Shaker circular dance. [Image at right] The services were later open to the outsiders, who treated them as curiosity and diversion. But the charismatic element was not lost entirely, at least until mid-nineteenth century, and it manifested itself strongly during the Era of Manifestations, when hardly a meeting could pass without spirit possession, revelation and other spiritual gifts. No comparable revival occurred later, and the ecstatic elements gradually evaporated from Shaker worship. In the twentieth century, no outward occurrences of spiritual possession accompanied Shaker worship, which came to resemble mainstream Protestant services. Later on, in most of the surviving villages all forms of communal worship were abandoned altogether (to be revived since the 1960 in Sabbathday Lake), giving way to individual prayer and contemplation.

formalized into more conventional services with readings, sermons and group dances, such as the famous Shaker circular dance. [Image at right] The services were later open to the outsiders, who treated them as curiosity and diversion. But the charismatic element was not lost entirely, at least until mid-nineteenth century, and it manifested itself strongly during the Era of Manifestations, when hardly a meeting could pass without spirit possession, revelation and other spiritual gifts. No comparable revival occurred later, and the ecstatic elements gradually evaporated from Shaker worship. In the twentieth century, no outward occurrences of spiritual possession accompanied Shaker worship, which came to resemble mainstream Protestant services. Later on, in most of the surviving villages all forms of communal worship were abandoned altogether (to be revived since the 1960 in Sabbathday Lake), giving way to individual prayer and contemplation.

Shaker faith is, to use Theodore Johnson’s expression, “suprasacramental” (Johnson 1969:7–8); they do not believe in sacraments as means of producing a certain effect, but, rather, as signs of spiritual bond with God, of which living in Christ Spirit is the ultimate fulfillment. More generally, high importance attached by Shakers to work makes it plausible to treat it as a form of worship, too, as indicated by the oft-repeated Ann Lee’s maxim “Hands to work, hearts to God.”

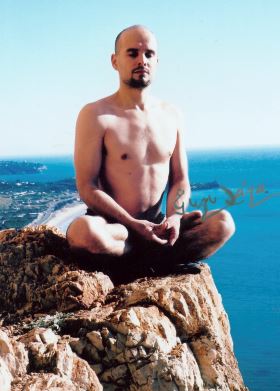

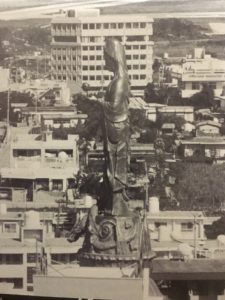

Songs were another important element of Shaker life and worship. The most famous perhaps, Simple Gifts by elder Joseph Brackett, which penetrated to American popular culture, is just one of estimated 10,000 songs of various kinds (hymns, working and dancing songs etc.) written by the Shakers. Many of them originated during the Era of Manifestations, the time when some of  the finest examples of Shaker religious art, with the famous Tree of Life by Hannah Cahoon, [Image at right] were also created (these pieces of art, received under inspiration, were called gift songs and gift drawings, respectively; see Patterson 1983).

the finest examples of Shaker religious art, with the famous Tree of Life by Hannah Cahoon, [Image at right] were also created (these pieces of art, received under inspiration, were called gift songs and gift drawings, respectively; see Patterson 1983).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Basic principles, on which the organization of Shaker communities rested, included:

Communism (or communalism): the quadruple community of goods, production, consumption and living. Apart from small personal belongings, Shakers held all property in common. They worked together, rotating various tasks in farms and workshops to avoid dull routine. They had communal meals and received other goods and services according to their needs. And they lived together in large communal buildings.

Celibacy. Already in England, Ann Lee came to a conclusion that sexual desire is at the root of most evil in the world, a conviction that was no doubt influenced by her forced, unhappy marriage and miscarriage of four children. Hence Shakers were forbidden any intimate relations whatsoever. Men and women lived together but separately: they slept in the same buildings, but at the opposite sides; they used separate stairs, dined at separate tables, sat at the opposite sides of the meeting house at worship services and had little direct contact during daily chores. To alleviate some of the tension it must have created, weekly meetings were organized where male and female members could enjoy a more or less free conversation, on, to be sure, innocent topics. If families joined the Society together, they were separated. All children were brought up communally.

Non-violence. Despite a high level of social control within the communities, Shakers rejected the use of physical force between themselves and tried to avoid it whenever possible in relation to strangers, even in self-defense. They were pacifists: they objected to military service and, when forced to it, many of them refused to accept their pay.

Shakers lived in villages, divided into “families,” social units whose members were not biologically related, but lived and worked together. New converts were accepted into a novitiate (“Gathering order”), before, after approximately a year, becoming full members. These new members of Shaker communes entered into a “covenant,” a document setting out the doctrines they declared their faith in, specifying their obligations towards the leaders and other members, consecrating their property to the group and forfeiting any claims to it (Constitution of the United Societies (1978) [1833]). Thus, the religious status of an individual was strictly conditioned upon the economic sacrifice he or she was supposed to make (Desroche 1971:188–89).

All Shakers were also bound by the so-called Millennial Laws, a lengthy code of conduct developed in the phase of routinization of early charismatic authority, which comprised extremely detailed and stringent regulations of virtually all spheres of life in the community, down to which foot one is supposed to start ascending stairs or which knee should touch the floor first while kneeling (right in both cases, if you are curious) or what distance to keep when looking out the window (Millennial Laws 1963 [1845]). From the point of view of power relations, these legal norms performed a number of functions: they affirmed the divine sanction of the leaders (the covenants emphasized their “apostolic succession” from the Shakerism’s prophetic founder Ann Lee), made it a religious duty to obey them and created a kind of highly regulated, patterned, monastery-like environment with little room for individual deviation, which is easy to control, particularly when compared to early Shaker communities characterized by ecstatic cult forms and spontaneous outbreaks of uncontrolled behaviour. These legal norms thus paved the way to high level of political control [this paragraph is adapted from Potz 2020: Chapter 4].

As regards the sect’s political system, the original charismatic authority had gradually been replaced with the charisma of office (to borrow Max Weber’s category), even though the leaders had not completely renounced their claim to divine inspiration at least until late into the nineteenth century. Joseph Meacham instituted a four-member Central Ministry, composed of two male and two female members. Technically with authority over the New Lebanon bishopric only, it actually performed the role of the entire sect’s governing body. Similar power structures, also based on sex parity, grounded, as indicated above, in Shaker theology, were replicated at the level of each bishopric (a unit of several villages) and each “family.” (Brewer 1986:25–27). The succession procedure within the ministry was co-optation by the surviving members, which contrasted with the acclamation, typical of the succession of the first three leaders in the charismatic period. Both procedures were theocratic in that they sought to transmit and confer on the new leaders a divine sanction (more on Shaker succession procedures and other aspects of their political system, see Potz 2012) [this paragraph is adapted from Potz 2014].

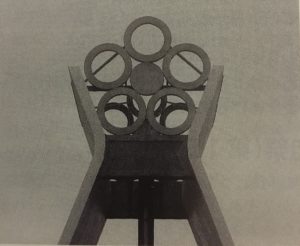

Shaker economy was based on farming and various related industries, such as the very profitable sale of seeds. Some Shaker crafts came to be very highly valued. This is true especially for their furniture, [Image at right] which entered antique market with the closure of many settlements in the twentieth century and commanded prices going into tens of thousands of dollars.

profitable sale of seeds. Some Shaker crafts came to be very highly valued. This is true especially for their furniture, [Image at right] which entered antique market with the closure of many settlements in the twentieth century and commanded prices going into tens of thousands of dollars.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Each period of Shaker history brought its unique problems and challenges. In the 18th century, their image as a radical sect with unorthodox doctrine, weird worship practices and female leadership aroused almost universal hostility: Shakers were harassed in various ways, tarred-and-feathered, accused of sexual licentiousness and, in America, of being British spies to boot (Stein 1992:13–14).

In the nineteenth century, relations with the “world” gradually settled and Shakers came to be perceived as peaceful neighbors, industrious, hard-working farmers and reliable business partners. Instead, internal problems crept in, such as leadership disputes during Era of Manifestations, laxing discipline or claims of ex-members and members’ families. The most serious challenge, however, was, by far, the dwindling membership, a trend initiated in mid-nineteenth century and never to be reversed. As the years went by, Shakers had been unable to keep the children brought up by the Society when they reached adulthood, and the adult converts, increasingly coming from the cities, very often joined for economic, rather than spiritual reasons. In fact, these three variables: long time spent among Shakers in childhood, urban origin and joining at a time of economic recession were the strongest predictors of apostacy (Murray 1995).

The twentieth century added new challenges, discussed in the history section above: the “closing of the covenant” by Canterbury leadership, disputed by Sabbathday Lake, [Image at right] and the accompanying management and financial problems regarding the remaining Society’s assets. After a period of revival at Sabbathday Lake lasting from the 1960s into the twenty-first century, with new members joining and the community religious life resuming, Shakers are again facing the existential challenge of survival. With only two members remaining, this seems a long call indeed.

The twentieth century added new challenges, discussed in the history section above: the “closing of the covenant” by Canterbury leadership, disputed by Sabbathday Lake, [Image at right] and the accompanying management and financial problems regarding the remaining Society’s assets. After a period of revival at Sabbathday Lake lasting from the 1960s into the twenty-first century, with new members joining and the community religious life resuming, Shakers are again facing the existential challenge of survival. With only two members remaining, this seems a long call indeed.

With their decline, as the celibate, communitarian Shakers ceased to be perceived as a challenge to the American core values of individualism, private property and traditional model of family, they were absorbed into the mainstream of American culture. In the process, their potentially “un-American” features were deemphasized, and their material culture was discovered, mainly due to the work of Edward Deming Andrews. This romanticized, sentimental image of Shakers as peaceful spiritual seekers inhabiting simple yet harmonious interiors furnished with their beautiful chairs and multi-drawer chests, has become a fixture of American popular culture (Potz 2014).

IMAGES

Image #1: John Meacham.

Image #2: Shaker circular dance.

Image #3: The Tree of Life by Hannah Cahoon.

Image #4: Shaker furntiture.

Image #5: Sabbathday Lake community.

REFERENCES

Andrews, Edward D. and Faith Andrews. 1969. Visions of the heavenly sphere: a study in Shaker religious art. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Brewer, Priscilla. 1986. Shaker Communities, Shaker Lives. Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

Cohen, Daniel. 1973. Not of the World. A History of the Commune in America. Chicago: Follet.

Desroche, Henri. 1971. The American Shakers. From Neo-Christianity to Presocialism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Evans, Frederick. 1859. Shakers. Compendium of the Origins, History, Principles, Rules and Regulations, Government and Doctrine. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

Francis, Richard. 2000. Ann the Word. The Story of Ann Lee, Female Messiah, Mother of the Shakers, The Woman Clothed With the Sun. New York: Penguin

Garrett, Clarke. 1987. Origins of the Shakers. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Humez, Jean. 1993. “’The Heavens are Open’. Women’s Perspectives on Midcentury Spiritualism.” Pp. 209-29 in Mother’s First-Born Daughters. Early Shaker Writings on Women and Religion, edited by J. Humez. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Johnson, Theodore. 1969. Life in the Christ Spirit. Sabbathday Lake: United Society.

Millennial Laws or Gospel Statutes and Ordinances adapted to the Day of Christ’s Second Appearing [1845], Part II, Section V. Reprinted in: The People Called Shakers. A Search for the Perfect Society. 1963. Edited by E. D. Andrews. New York: Dover Publications.

Morse, Flo. 1980. The Shakers and the World’s People. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co.

Murray, John E. 1995. “Determinants of Membership Levels and Duration in a Shaker Commune, 1780–1880”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 34:35–48.

Patterson, Daniel W. 1983. Gift Drawings and Gift Songs. Sabbathday Lake, ME: The United Society of Shakers

Paterwic, Stephen J. 2009. The A to Z of the Shakers. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press.

Potz, Maciej. 2020. Political Science of Religion: Theorising the Political Role of Religion. London: Palgrave Macmillan (forthcoming).

Potz, Maciej. 2016. Teokracje amerykańskie. Źródła i mechanizmy władzy usankcjonowanej religijnie. Łódź: Wydawnictwo UŁ.

Potz, Maciej. 2014. “American Shakers – Dying Religion, Emerging Cultural Phenomenon.” Studia Religiologica 47:307–20.

Potz, Maciej. 2012. “Legitimation mechanisms as third dimension power practices: the case of the Shakers.” Journal of Political Power 5:377–409.

Potz, Maciej. 2009. “Shakerzy – stadium instytucjonalnego samobójstwa.” In: O wielowymiarowości badań religioznawczych, edited by Z. Drozdowicz. Poznań: UAM.

Stein, Stephen. 1992. The Shaker Experience in America. A History of the United Society of Believers. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Wilson, Bryan. 1975. Magic and the Millennium. New York: Harper and Row.

Publication Date:

20 August 2019

hermitages in Italy, including Porto Venere, on the Ligurian coast, Lumignano, near Vicenza, Sperlonga, located between Rome and Naples, [Image at right] and Arco, in the Province of Trento.

hermitages in Italy, including Porto Venere, on the Ligurian coast, Lumignano, near Vicenza, Sperlonga, located between Rome and Naples, [Image at right] and Arco, in the Province of Trento. seminars and festivals.

seminars and festivals. successful that, after a new successful pilgrimage to India, a monastery was inaugurated in the village of Odrlice, near Olomouc. [Image at right] Other smaller centers called kitakus or tao ki tak (playing on both the Japanese word for “place of welcome” and the Czech expression “tak i tak,” meaning “either way”) followed, in 1999 in Zlín and Olomouc, Czech Republic, in Dharamshala, India, and in the village of Horní Bečva in the Beskids Mountains, the latter a smaller, secluded branch of the Odrlice monastery.

successful that, after a new successful pilgrimage to India, a monastery was inaugurated in the village of Odrlice, near Olomouc. [Image at right] Other smaller centers called kitakus or tao ki tak (playing on both the Japanese word for “place of welcome” and the Czech expression “tak i tak,” meaning “either way”) followed, in 1999 in Zlín and Olomouc, Czech Republic, in Dharamshala, India, and in the village of Horní Bečva in the Beskids Mountains, the latter a smaller, secluded branch of the Odrlice monastery. Prague, generating considerable attention. [Image at right]

Prague, generating considerable attention. [Image at right]

and the course teaching how to express themselves through Astrofocus art is one of the most popular among the Path’s students. [Image at right]

and the course teaching how to express themselves through Astrofocus art is one of the most popular among the Path’s students. [Image at right] and teaches techniques aimed at strengthening the aura, thus creating a magical protection against them. [Image at right]

and teaches techniques aimed at strengthening the aura, thus creating a magical protection against them. [Image at right] “meditative calm of normal practice in stressful situations” (Manek 2015:118–19). [Image at right] Bungee jumping meditation is part of a wider set of techniques, devised by Jára to customize traditional meditation methods in a way understandable by contemporary Western disciples,

“meditative calm of normal practice in stressful situations” (Manek 2015:118–19). [Image at right] Bungee jumping meditation is part of a wider set of techniques, devised by Jára to customize traditional meditation methods in a way understandable by contemporary Western disciples, and open to everybody, including non-members and even atheists. “Spiritual trekking” may also be learned through actual trekking, preferably in areas where the energy of the environment may interact with the student’s own energy in a special way: holy mountains, forests, traditional pilgrimage sites. [Image at right]

and open to everybody, including non-members and even atheists. “Spiritual trekking” may also be learned through actual trekking, preferably in areas where the energy of the environment may interact with the student’s own energy in a special way: holy mountains, forests, traditional pilgrimage sites. [Image at right] members. In the Philippines, the ashram has four permanently resident nuns, and “temporary monks” (and nuns) coming from other countries to stay in Siargao for some weeks or months. Most Czech members visit Siargao once or twice a year. [Image at right]

members. In the Philippines, the ashram has four permanently resident nuns, and “temporary monks” (and nuns) coming from other countries to stay in Siargao for some weeks or months. Most Czech members visit Siargao once or twice a year. [Image at right] cancelled by the local organizers due to media attacks, but in general at least a part of the art community remained willing to celebrate Jára’s artistic achievements even after he was convicted for sexual abuse in Zlín and detained in the Philippines. [Image at right

cancelled by the local organizers due to media attacks, but in general at least a part of the art community remained willing to celebrate Jára’s artistic achievements even after he was convicted for sexual abuse in Zlín and detained in the Philippines. [Image at right Those responsible were never identified. Another branch monastery, called B7, was quietly opened to replace it in 2002; it was eventually sold in 2011 in order to finance the construction of the ashram in the Philippines. [Image at right]. In 2004, arsonists attacked the main monastery in Odrlice. The devotees managed to save the building, but the property of a neighbor was destroyed. Physical violence continued to be a feature of the anti-cult campaign. Jára himself barely escaped two personal assault attempts in 2005, which he regarded as consequences of the campaign.

Those responsible were never identified. Another branch monastery, called B7, was quietly opened to replace it in 2002; it was eventually sold in 2011 in order to finance the construction of the ashram in the Philippines. [Image at right]. In 2004, arsonists attacked the main monastery in Odrlice. The devotees managed to save the building, but the property of a neighbor was destroyed. Physical violence continued to be a feature of the anti-cult campaign. Jára himself barely escaped two personal assault attempts in 2005, which he regarded as consequences of the campaign. Frontiers 2017; Fautré 2017). On June 10, 2015, the Czech police unsuccessfully tried to forcibly deport Jára back to Prague from the Philippines, while his asylum case was pending. [Image at right]

Frontiers 2017; Fautré 2017). On June 10, 2015, the Czech police unsuccessfully tried to forcibly deport Jára back to Prague from the Philippines, while his asylum case was pending. [Image at right]

of FM-2030’s disciples, Max More, became director of Alcor.

of FM-2030’s disciples, Max More, became director of Alcor. Transhumanist Association adopted a new name, Humanity Plus or Humanity+, [Image at right] and Natasha Vita-More became its director. She and Max More had been leading disciples of FM-2030, like him having adjusted their names to stress a focus on the future. In 2013, they edited the anthology, The Transhumanist Reader, which includes a chapter by Prisco.

Transhumanist Association adopted a new name, Humanity Plus or Humanity+, [Image at right] and Natasha Vita-More became its director. She and Max More had been leading disciples of FM-2030, like him having adjusted their names to stress a focus on the future. In 2013, they edited the anthology, The Transhumanist Reader, which includes a chapter by Prisco. derives from the Church-Turing thesis, a standard principle in mathematics and computer science, developed by two mathematicians, Alonzo Church and Alan Turing. [Image at right] The thesis concerns the general principle of deriving results through a series of rigorously defined transformative steps, such as the procedures in a computer program. In the religious context, the Church-Turing thesis suggests that if God does not exist, the only way to create God is through a series of rigorous scientific discoveries and engineering inventions, perhaps primarily inside computers. This seems to deny the possibility of true transcendence of material reality, and it must be noted that current research in quantum computing may escape the Church-Turing thesis, although we cannot yet be certain about any such rediscovery of transcendence.

derives from the Church-Turing thesis, a standard principle in mathematics and computer science, developed by two mathematicians, Alonzo Church and Alan Turing. [Image at right] The thesis concerns the general principle of deriving results through a series of rigorously defined transformative steps, such as the procedures in a computer program. In the religious context, the Church-Turing thesis suggests that if God does not exist, the only way to create God is through a series of rigorous scientific discoveries and engineering inventions, perhaps primarily inside computers. This seems to deny the possibility of true transcendence of material reality, and it must be noted that current research in quantum computing may escape the Church-Turing thesis, although we cannot yet be certain about any such rediscovery of transcendence. as a series of dynamic conversations often preserved as videos, occasionally held in the Second Life virtual world, [Image at right] and often conducted in video conferencing systems. As of August 1, 2019, the website for the Turing Church had three “editors,” Prisco and two men whose descriptions express both similarity and diversity: “Lincoln Cannon is a technologist and philosopher, and leading advocate of technological evolution and postsecular religion.” “Micah Redding – Christian Transhumanism: Faith & science, religion & technology, the future of humanity. Host of the Christian Transhumanist Podcast.” This trio are also “admins” of the Turing Church Facebook group, along with Nupur Munshi, a freelance research writer in India, and Kathy Wilson, an artist and researcher on spiritual experiences in Utah. It is noteworthy that leaders in the Turing Church are not bishops but editors and admins, in accordance with post-modern Internet culture.

as a series of dynamic conversations often preserved as videos, occasionally held in the Second Life virtual world, [Image at right] and often conducted in video conferencing systems. As of August 1, 2019, the website for the Turing Church had three “editors,” Prisco and two men whose descriptions express both similarity and diversity: “Lincoln Cannon is a technologist and philosopher, and leading advocate of technological evolution and postsecular religion.” “Micah Redding – Christian Transhumanism: Faith & science, religion & technology, the future of humanity. Host of the Christian Transhumanist Podcast.” This trio are also “admins” of the Turing Church Facebook group, along with Nupur Munshi, a freelance research writer in India, and Kathy Wilson, an artist and researcher on spiritual experiences in Utah. It is noteworthy that leaders in the Turing Church are not bishops but editors and admins, in accordance with post-modern Internet culture.

meditate for at least five minutes as soon as they wake up each morning on the topic of being “used by God” as an agent of love (Winfrey 2019). [Image at right] She explains that this practice sets the correct intention for the day and centers the mind on reality rather than illusions. Williamson also encourages people to use similar meditations and prayers during difficult situations, particularly when upset, angry, or sad in order to achieve miracles.

meditate for at least five minutes as soon as they wake up each morning on the topic of being “used by God” as an agent of love (Winfrey 2019). [Image at right] She explains that this practice sets the correct intention for the day and centers the mind on reality rather than illusions. Williamson also encourages people to use similar meditations and prayers during difficult situations, particularly when upset, angry, or sad in order to achieve miracles.

(Sinnett 1976:35; Cranston 1993:29). Many accounts attest that as a child she already displayed talents of a spiritualist and occult nature (Sinnett 1976:20, 32, 42–43, 49–50).

(Sinnett 1976:35; Cranston 1993:29). Many accounts attest that as a child she already displayed talents of a spiritualist and occult nature (Sinnett 1976:20, 32, 42–43, 49–50).

and Olcott’s attention [Image at right] was directed towards India and its religious traditions. They left New York City on December 17, 1878, just a few months after Blavatsky had become an American citizen on July 8, 1878. In India, the Theosophical Society expanded with great success and established the journal The Theosophist edited by Blavatsky. In 1884, Blavatsky left for Paris, London, and Elberfeld in Germany only to return to India in 1885; she subsequently left India for good, sailing to Naples and onward to Würzburg, Germany and Ostend, Belgium, in July 1886 to work on her second major opus The Secret Doctrine.

and Olcott’s attention [Image at right] was directed towards India and its religious traditions. They left New York City on December 17, 1878, just a few months after Blavatsky had become an American citizen on July 8, 1878. In India, the Theosophical Society expanded with great success and established the journal The Theosophist edited by Blavatsky. In 1884, Blavatsky left for Paris, London, and Elberfeld in Germany only to return to India in 1885; she subsequently left India for good, sailing to Naples and onward to Würzburg, Germany and Ostend, Belgium, in July 1886 to work on her second major opus The Secret Doctrine. Secret Doctrine. [Image at right] Blavatsky went to live in Besant’s home, which also became the location of the Blavatsky Lodge. Since Blavatsky’s health was failing, she and Besant co-edited Lucifer. Many of her most devoted disciples and colleagues stayed with Blavatsky until her death in 1891.

Secret Doctrine. [Image at right] Blavatsky went to live in Besant’s home, which also became the location of the Blavatsky Lodge. Since Blavatsky’s health was failing, she and Besant co-edited Lucifer. Many of her most devoted disciples and colleagues stayed with Blavatsky until her death in 1891.

consecrated virgins died as martyrs in order to remain faithful to their commitment to the Lord. For example, it is reported that Agnes of Rome [Image at right] refused to marry the city’s governor because of her dedication to chastity and, as a result, was killed. Cecilia of Rome, Agatha of Catania, Lucy of Syracuse, Thecla of Iconium, Apollonia of Alexandria, Restituta of Carthage, and Justa and Rufina of Seville are other women believed to have been martyred due to their commitment to chastity in the first three centuries of Christianity (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018).

consecrated virgins died as martyrs in order to remain faithful to their commitment to the Lord. For example, it is reported that Agnes of Rome [Image at right] refused to marry the city’s governor because of her dedication to chastity and, as a result, was killed. Cecilia of Rome, Agatha of Catania, Lucy of Syracuse, Thecla of Iconium, Apollonia of Alexandria, Restituta of Carthage, and Justa and Rufina of Seville are other women believed to have been martyred due to their commitment to chastity in the first three centuries of Christianity (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018).

generous self-giving to the Lord and to her neighbour” (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018). If the woman is accepted for consecration, [Image at right] the bishop and the woman will determine the details of the celebration, which will include the participation of the church community.

generous self-giving to the Lord and to her neighbour” (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018). If the woman is accepted for consecration, [Image at right] the bishop and the woman will determine the details of the celebration, which will include the participation of the church community. gown and veil during the consecration ceremony, and they wear a wedding ring as a symbol of their commitment to Christ. [Image at right]

gown and veil during the consecration ceremony, and they wear a wedding ring as a symbol of their commitment to Christ. [Image at right] may choose to voluntarily join in an association. [Image at right] The United States Association of Consecrated Virgins (USACV) states it “is formed in accord with Canon 604.2. ‘Virgins can be associated together to fulfill their pledge more faithfully and to assist each other to serve the Church in a way that befits their state’” (United States Association of Consecrated Virgins 2019).

may choose to voluntarily join in an association. [Image at right] The United States Association of Consecrated Virgins (USACV) states it “is formed in accord with Canon 604.2. ‘Virgins can be associated together to fulfill their pledge more faithfully and to assist each other to serve the Church in a way that befits their state’” (United States Association of Consecrated Virgins 2019).

leaders in antiquity, and from Shinto (Reichl 1993b). The Ijun logo, five dark circles around a lighter central circle, is said to represent the major world religious traditions coming together in Ijun. [Image at right] This recalls the logo of Seichō no Ie. Both Ijun and Seichō no Ie encourage followers to attend other churches as well. At the same time, many Ijun concepts are from Ryukyuan culture, including the sibling creator deities, Amamikyu and Shinerikyu (See Doctrines/Beliefs), and the primary deity Kinmanmon. Although Ijun no longer exists in a formal legal sense, some adherents continue to practice informally. It is unclear to what extent the company Culture Ijun continues religious activity.

leaders in antiquity, and from Shinto (Reichl 1993b). The Ijun logo, five dark circles around a lighter central circle, is said to represent the major world religious traditions coming together in Ijun. [Image at right] This recalls the logo of Seichō no Ie. Both Ijun and Seichō no Ie encourage followers to attend other churches as well. At the same time, many Ijun concepts are from Ryukyuan culture, including the sibling creator deities, Amamikyu and Shinerikyu (See Doctrines/Beliefs), and the primary deity Kinmanmon. Although Ijun no longer exists in a formal legal sense, some adherents continue to practice informally. It is unclear to what extent the company Culture Ijun continues religious activity.