Wicca

WICCA

WICCA TIMELINE

1951 The 1735 Witchcraft Laws, which had made the practice of Witchcraft a crime in Great Britain, were abolished.

1951 The Witchcraft Museum on the Isle of Man opened with backing from Gerald Gardner.

1954 Gardner published the first non-fiction book on Wicca, Witchcraft Today .

1962 Raymond and Rosemary Buckland, initiated Witches, came to the United States and began training others.

1971 The first feminist coven was formed in California by Zsuzsanna Budapest.

1979 Starhawk published The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess .

1986 Raymond Buckland published the Complete Book of Witchcraft.

1988 Scott Cunningham published Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner .

2007 The United States Armed Services permitted the Wicca pentagram to be placed on graves in military cemeteries.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Gerald Gardner, a British civil servant, is credited with the creation of Wicca, although some disagreement continues to swirl around whether or not that is true. Gardner contended that he was initiated into the New Forest Coven, by Dorothy Clutterbuck in 1939. Members of this coven claimed that theirs was a traditional Wiccan coven whose rituals and practices had been passed down since pre- Christian times.

around whether or not that is true. Gardner contended that he was initiated into the New Forest Coven, by Dorothy Clutterbuck in 1939. Members of this coven claimed that theirs was a traditional Wiccan coven whose rituals and practices had been passed down since pre- Christian times.

In 1951, laws prohibiting the practice of witchcraft in England were repealed, and soon thereafter, in 1954, Gardner published his first non-fiction book, Witchcraft Today (Berger 2005:31). His account came into question, first by an American practitioner Aiden Kelly (1991) and subsequently by others (Hutton 1999; Tully 2011) Hutton (1999), a historian who wrote the most comprehensive book on the development of Wicca, claims that Gardner did something more profound than merely codifying and making public a hidden old religion: he created a new vibrant religion that has spread around the world. Gardner was helped in this endeavor by Doreen Valiente, who wrote much of the poetry used in the rituals, thereby helping to make them more spiritually moving (Griffin 2002:244).

Some of Gardner’s students or students of those trained by him, such as Alex and Maxine Saunders, created variations of Gardner’s spiritual and ritual system, spurring new sects or forms of Wicca to develop. From the beginning there were some who claimed to have been initiated into other covens that had been underground for centuries. None of these garnered either the success of Gardner’s version or the scrutiny. It is most probable that some of them were influenced by many of the same social influences that had informed Gardner, including the Western occult or magical tradition, folklore and the romantic tradition, Freemasonry, and the long tradition of village folk healers or wise people (Hutton 1999).

It has typically been believed that British immigrants Raymond and Rosemary Buckland brought Wicca to the United States. But, the history is actually more complex as evidence suggests that copies of Gardner’s fictional account of Witchcraft and his non-fiction book, Witchcraft Today were brought over to the United States prior to the arrival of the Bucklands (Clifton 2006:15). Nonetheless the Bucklands were important in the importation of the religion as they created the first Wiccan coven in the United States and initiated others. Once on American soil, the religion became attractive to feminists looking for a female face of the divine and environmentalists who were drawn to the celebration of the seasonal cycles. Both movements, in turn, helped to transform the religion. Although the Goddess was celebrated, the coven led by the High Priestess Gardner had not developed a feminist form of spirituality. It was common, for example, for the High Priestess to be required to step down when she was no longer young (Neitz 1991:353).

Miriam Simos, who writes under her magical name, Starhawk, was instrumental in bringing feminism and feminist concerns to  Wicca. She was initiated into the Fairie Tradition of Witchcraft and into Zsuzsanna Budapest’s Feminist Spirituality group. Starhawk’s first book, The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (1979), which brought together both threads of her training, sold over 300,000 copies.(Salomonsen 2002:9). During this same period the religion went from a mystery religion (one in which sacred and magical knowledge is reserved for initiates), with a focus on fertility, to an earth based religion (one that came to see the earth as a manifestation of the Goddess — alive and sacred) ( Clifton 2006:41). These two changes helped to make the religion appealing to those touched by feminism and environmentalism both in the United States and abroad. The religion’s spread was further aided by the publication of relatively inexpensive books and journals and the growth of the Internet.

Wicca. She was initiated into the Fairie Tradition of Witchcraft and into Zsuzsanna Budapest’s Feminist Spirituality group. Starhawk’s first book, The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (1979), which brought together both threads of her training, sold over 300,000 copies.(Salomonsen 2002:9). During this same period the religion went from a mystery religion (one in which sacred and magical knowledge is reserved for initiates), with a focus on fertility, to an earth based religion (one that came to see the earth as a manifestation of the Goddess — alive and sacred) ( Clifton 2006:41). These two changes helped to make the religion appealing to those touched by feminism and environmentalism both in the United States and abroad. The religion’s spread was further aided by the publication of relatively inexpensive books and journals and the growth of the Internet.

Initially the Bucklands, following Gardner’s dictate, claimed that a neophyte needed to be trained by a third degree Wiccan, someone who had been trained in a coven and gone through three levels or degrees of training, similar to those in the Freemasons. However, Raymond Buckland changed his position on this. He eventually published a book and created a video explaining how individuals could self-initiate. Others, most notably Scott Cunningham, also wrote how-to books that resulted in self-initiation becoming common. Wicca: A Guide for Solitary Practice (Cunningham 1988) alone has sold over 400,000 copies. His book and other how-to books have helped to fuel the trend toward most Wiccans practicing alone. The large number of Internet sites and the growth of umbrella groups (that is, groups that provide information, open ritual, and at times religious retreats, referred to as festivals) make it possible for Wiccans and other Pagans to maintain contact with others whether they practice in a coven or alone. The growth of these books and websites helped to make Wicca less of a mystery religion. Initially it was in the coven that esoteric knowledge was taught, often as secret knowledge that could only be passed on to others who were initiated into the religion. Little, if any, of the rituals or knowledge now remains secret.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

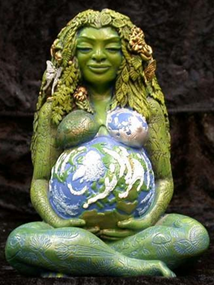

Belief in Wicca is less important than experience of the divine or magic. It is common for Wiccans to say they don’t believe in the Goddess (es) and God(s); they experience them. It is through ritual and meditation that they gain this experience of the divine and perform magical acts. The religion is non-doctrinal, with the Wiccan Rede “Do as thou will as long as thou harm none” being the only hard and fast rule. The religion, according to Gardner, existed throughout Europe prior to the advent to Christianity. In Gardner’s presentation, the Goddess and the God balance what he called male and female energies. Groups, referred to as covens, are ideally to mimic that balance by being composed of six women and six men with an additional woman who is High Priestess. One of the men in the group serves as the High Priest but the Priestess is the group leader. In actuality few covens have this exact number of participants, although most are small groups (Berger 1999:11-12).

The ritual calendar is based on an agricultural calendar that emphasizes fertility. This emphasis is reflected in the changing

relationship between the Goddess and the God as portrayed in the rituals. The Goddess is viewed as eternal but changing from the maid, to mother, to crone; then, in the spiral of time, she returns in the spring as a young woman. The God is born of the mother in midwinter, becomes her consort in the spring, dies to ensure the growth of crops in the fall; then he is reborn at the winter solstice. The God is portrayed with horns, a sign of virility. The image is an old one that was converted to the image of the Devil within Christianity. All goddesses are viewed as aspects of the one Goddess just as all gods are believed to be aspects of the one God.

relationship between the Goddess and the God as portrayed in the rituals. The Goddess is viewed as eternal but changing from the maid, to mother, to crone; then, in the spiral of time, she returns in the spring as a young woman. The God is born of the mother in midwinter, becomes her consort in the spring, dies to ensure the growth of crops in the fall; then he is reborn at the winter solstice. The God is portrayed with horns, a sign of virility. The image is an old one that was converted to the image of the Devil within Christianity. All goddesses are viewed as aspects of the one Goddess just as all gods are believed to be aspects of the one God.

The image of Wicca as the old religion, led by women, that celebrated fertility of the land, animals and people was taken by Gardner from Margaret Murray (1921), who wrote the foreword to his book. She argued that the witch trials were an attack on practitioners of the old religion by Christianity. Gardner took from Murray the image of witches of the past as healers who used their knowledge of herbs and magic to help individuals in their community deal with illness, infertility and other problems. At the time that Gardner was writing, Murray was considered an expert on the witch trials, although her work subsequently came under attack and is no longer accepted by historians.

Magic and magical practices are integrated into the belief system of Wiccans. The magical system is one that is based on the work of Aleister Crowley, who codified Western esoteric knowledge. He defined magic as the act of changing reality to will. Magical practices have waxed and waned in the West but have never disappeared (Pike 2004). They can be traced back to twelfth century appropriations of the Cabbala and ancient Greek practices by Christianity and were important during the scientific revolution (Waldron 2008:101).

Within Wiccan rituals, a form of energy is believed to be raised through dancing, chanting, meditation, or drumming, which can be directed toward a cause, such as healing someone or finding a job, parking place, or rental apartment. It is believed that the energy that an individual sends out will return to her/him three-fold and hence the most common form of magic is healing magic. Performing healing both helps to show that the Witch has magical power and that s/he uses it for good ( Crowley 2000:151-56). For Wiccans the world is viewed as magical. It is commonly believed that the Goddess or the God may send an individual a sign or give them direction in life. These may come during a ritual or meditation or in the course of everyday life as people happen upon old friends or find something in the sand at the beach that they believe is of import. Magic therefore is a way of connecting with the divine and with nature. Magic is viewed as part of the natural world and indicative of individuals’ connection to nature, to one another, and to the divine.

directed toward a cause, such as healing someone or finding a job, parking place, or rental apartment. It is believed that the energy that an individual sends out will return to her/him three-fold and hence the most common form of magic is healing magic. Performing healing both helps to show that the Witch has magical power and that s/he uses it for good ( Crowley 2000:151-56). For Wiccans the world is viewed as magical. It is commonly believed that the Goddess or the God may send an individual a sign or give them direction in life. These may come during a ritual or meditation or in the course of everyday life as people happen upon old friends or find something in the sand at the beach that they believe is of import. Magic therefore is a way of connecting with the divine and with nature. Magic is viewed as part of the natural world and indicative of individuals’ connection to nature, to one another, and to the divine.

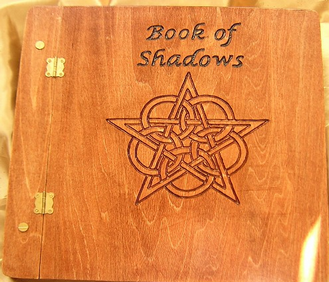

Wiccans traditionally keep a Book of Shadows, which includes rituals and magical incantations that have worked for them. It is common for the High Priestess and High Priest, leaders of the coven, to share their Book of Shadows with those they are initiating, permitting them to copy some rituals entirely. Each Book of Shadows is unique to the Wiccan who has created it and often is a work of art in its own right.

Most, although not all, Wiccans believe in reincarnation (Berger et al 2003:47). The dead are believed to go to Summerland between lives, a place where their soul or essence has a chance to reflect on the life they lived before rejoining the world again to continue their spiritual growth. Karma of their past actions will influence their placement in their new life. But, unlike Eastern concepts of reincarnation that emphasize the desire to end this cycle of birth, death and reincarnation, returning to life is viewed positively by Wiccans. The inner being is able to interact again with those who were important in past lives, learn and evolve spiritually.

RITUALS

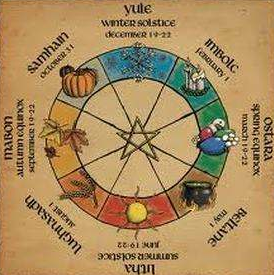

Within Wicca, rituals are more important than beliefs as they help put the practitioner in touch with spiritual or magical elements. The major rituals involve the circle of the year (the eight sabbats that occur six weeks apart throughout the year) and are conducted on the solstices, equinoxes and what are known as the cross days between them. These commemorate the beginning and height of each season and the changing relationship between the God and the Goddess. Birth, growth, and death are all seen as a natural part of the cycle and are celebrated. The changes in nature are believed to be reflected in individuals’ lives. Samhain (pronounced Sow-en), which occurs on October 31 st, is considered the Wiccan New Year and is of particular import. The veils between the worlds, that of the living and that of the spirit, are believed to be particularly thin on this evening. Wiccans deem this the easiest time of the year to be in contact the dead. This is also a time during which people will do magical working to rid their lives of habits, behaviors, and people that are no longer a positive force in their lives. For example, someone may perform a ritual to eliminate procrastination or to help them gather their energies to leave a dead end job or a dead end relationship. In the spring, the sabbats celebrate spring and fertility in nature and in people’s lives. There is always a balance in rituals between the changes in nature and the changes in individuals’ lives (Berger 1999:29-31).

Esbats, the celebration of the moon cycles, are also of import. Drawing Down the Moon, which is possibly the best known ritual within Wicca because of a book by that title by Margot Adler (1978, 1986), involves an invocation in which the Goddess or her powers enters the High Priestess. For the duration of the ritual she becomes the Goddess incarnate (Adler 1986:18-19). This ritual is held on the full moon, which is associated with the Goddess in her phase as Mother. New moons or dark moons, which are associated with the crone, are also typically celebrated. Less often a ritual is held for the crescent or maiden moon. There are also rituals for marriages (referred to as hand-fastings); births (Wiccanings); and changing statuses of participants, such as coming of age or becoming an elder or a crone. Rituals are held for initiation and for those who becoming first, second, or third degree Wiccans or Witches. Rituals can also be done for personal reasons, including rituals for healing, for help with a particular problem or issue, for celebration of a happy event, or for thanking the deities for their help.

Wiccans conduct their magical and sacred rites within a ritual Circle that is created by “cutting” the space with an athame (ritual  knife). Because Wiccans do not normally have churches, they need to create sacred space for the ritual in what is normally mundane space. This is done in covens by the High Priestess and High Priest walking around the circle while extending athames out in front of them and chanting. Participants visualize a blue or white light radiating up in a sphere to create a safe and sacred place. The High Priestess and High Priest then call in or invoke the watchtower, that is, the powers of the four directions (east, south, west and north) and the deities associated with each of those. They normally consecrate the circle and the participants with elements that are associated with each of these directions, which are placed on an altar in the center of the circle (Adler 1986:105-106). Altars are typically decorated to reflect the ritual being celebrated. For example, at Samhain, when death is celebrated as part of the cycle of life, pictures of deceased relatives and friends may decorate the altar; on May Day (May 1 st) there would be fresh flowers and fruit on the altar, symbolizing new life and fertility.

knife). Because Wiccans do not normally have churches, they need to create sacred space for the ritual in what is normally mundane space. This is done in covens by the High Priestess and High Priest walking around the circle while extending athames out in front of them and chanting. Participants visualize a blue or white light radiating up in a sphere to create a safe and sacred place. The High Priestess and High Priest then call in or invoke the watchtower, that is, the powers of the four directions (east, south, west and north) and the deities associated with each of those. They normally consecrate the circle and the participants with elements that are associated with each of these directions, which are placed on an altar in the center of the circle (Adler 1986:105-106). Altars are typically decorated to reflect the ritual being celebrated. For example, at Samhain, when death is celebrated as part of the cycle of life, pictures of deceased relatives and friends may decorate the altar; on May Day (May 1 st) there would be fresh flowers and fruit on the altar, symbolizing new life and fertility.

Once the circle is cast, participants are said to be between the worlds in an altered state of consciousness. The rite for the  particular celebration is then conducted. The Circle also serves to contain energy that is built up during the rites until it is ready to be released in what is known as the Cone of Power. Singing, dancing, meditation, and chanting can all be used by Wiccans to raise power during a ritual. The cone of power is released for a purpose set by the Wiccan practitioners. There can be one shared purpose, such as healing a particular person or the rainforest, or each person may have his or her own particular magical purpose (Berger 1999:31). The ceremony ends with a cup of wine being raised and an athame dipped into it, symbolizing the union between the Goddess and the God. The wine is then passed around the Circle with the words “Blessed Be” and drunk by the practitioners. Cakes are blessed by the High Priestess and Priest; they are also passed around with the words “blessed be” and then eaten (Adler 1986:168). Sometimes rituals are conducted naked (skyclad) or in ritual robes, depending on the Wiccan tradition and the place the ritual is conducted. Outdoor or public rituals are normally conducted in robes or street clothes. At the end of the rites, the Circle is opened and the Watchtowers are symbolically taken down. Traditionally, people then share a meal, as eating is seen as needed to ground participants (i.e., help them leave a magical state and return to the mundane world).

particular celebration is then conducted. The Circle also serves to contain energy that is built up during the rites until it is ready to be released in what is known as the Cone of Power. Singing, dancing, meditation, and chanting can all be used by Wiccans to raise power during a ritual. The cone of power is released for a purpose set by the Wiccan practitioners. There can be one shared purpose, such as healing a particular person or the rainforest, or each person may have his or her own particular magical purpose (Berger 1999:31). The ceremony ends with a cup of wine being raised and an athame dipped into it, symbolizing the union between the Goddess and the God. The wine is then passed around the Circle with the words “Blessed Be” and drunk by the practitioners. Cakes are blessed by the High Priestess and Priest; they are also passed around with the words “blessed be” and then eaten (Adler 1986:168). Sometimes rituals are conducted naked (skyclad) or in ritual robes, depending on the Wiccan tradition and the place the ritual is conducted. Outdoor or public rituals are normally conducted in robes or street clothes. At the end of the rites, the Circle is opened and the Watchtowers are symbolically taken down. Traditionally, people then share a meal, as eating is seen as needed to ground participants (i.e., help them leave a magical state and return to the mundane world).

Solitary practitioners may join with other Wiccans or Pagans for the sabbats or esabats or perform the rituals alone. Some groups offer public rituals, often in a rented space at a liberal church or the backroom of a metaphysical bookstore. If the practitioner does a ritual alone they modify the ritual as needed. Books and some websites provide suggestions to enable solitary practitioners to do these rituals individually.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

According to the American Religious Identity survey conducted in 2008, there are 342,000 Wiccans in the United States. This is consistent with the number of teenage and emerging adult Wiccans found in The National Survey of Youth and Religion (Smith with Denton 2005:31; Smith with Snell 2009:104) Many experts believe this number is too small, based on book sales of Wiccan books and traffic on Pagan websites. Nonetheless, the religion is a minority religion. Wiccans live throughout the United States, with the largest concentration in California where ten percent of all Wiccans reside. The District of Columbia and South Dakota have the lowest percentage, with one-tenth of one percent of Wiccans living in either of those areas (Berger unpublished).

There is no single leader for all Wiccans or Witches. Most pride themselves on being leaderless. Traditionally, Wicca has been taught in covens, but a growing number of Wiccans are self-initiated, having learned about the religion primarily from books and secondarily from Websites. Some individuals are well-respected and known within the community, mostly because of their writing. Miriam Simos, who writes under her magical name, Starhawk, has been called the most famous Witch of the West (Eilberg-Schwatz 1989). Her books have had an important impact on the religion, and she was the founder and one of the leaders of her tradition, The Reclaiming Witches. Even those who have not read her books may be influenced by the ideas as they have become so much a part of the core thinking of many in the religion. There are some Pagan umbrella organizations, such as the Covenant of the Goddess (CoG), EarthSpirit Community, and Circle Sanctuary that organize festivals, have open rituals for the major sabbats, provide a webpage with information, and fight against discrimination for all Pagans. They normally charge a small fee for being a member and other fees for open rituals and festival attendance. No one is required to be a member, and there is a growing number of Wiccans who are not members of any organization. Nonetheless, these groups remain important and many of their leaders are well known within the larger Pagan community.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

There is a longstanding debate among practitioners about the group’s sacred history as presented by Gardner. Although most Wiccans now regard it as a foundation myth, a small but vocal minority believe it to be literally true. Several academics, such as Hutton and Tully have had their credentials and work brought into question by practitioners who disagree with their historical or archeological findings. Hutton (2011:227) claims that those who critique him and others who have questioned Gardner’s claim to an unbroken history between antiquity and current practices of Witchcraft have provided no new evidence to support their claims. Hutton (2011, 1999), Tully (2011) and others note that there are some elements of continuity between pre-Christian practices and current ones, particularly in terms of magical beliefs and practices, but that this does not indicate an unbroken religious tradition or practice. Hutton argues that some elements of earlier Pagan practices were incorporated into Christianity and some remained as folklore and were absorbed by Gardner creatively. Wiccan practices are informed by past practices according to him and others but that does not mean that those who were executed as witches in the early modern period were practitioners of the old religion as Margaret Murray claimed or that current practitioners are in a unbroken line of pre-Christian Europeans or Britons.

Although Wicca has gained acceptance in the past twenty years, it remains a minority religion and continues to have to fight for  religious freedom. Wiccans have won a number of court cases resulting in the pentagram being an accepted symbol on graves in military cemeteries, and, recently in California, the recognition that Wiccan prisoners must be provided with their own clergy (Dolan 2013). Nonetheless, there continues to be discrimination. For example, on Sunday, February 17, 2013 Friends of Fox anchors mocked Wicca when reporting that the University of Missouri recognized all Wiccan holidays (in reality only the Sabbats were recognized). The three anchors went on to proclaim Wiccans were either dungeons and dragons players or twice divorced middle-aged women who live in rural areas, are mid-wives and like incense. This portrait is both demeaning and inaccurate as all research indicates that while most Wiccans are women, they tend to live in urban and suburban areas and are as likely to be young as middle aged, and tend to be better educated than the general American public (Berger 2003:25-34). After a protest lead mostly by Selena Fox of Circle Sanctuary, the network apologized. Nonetheless most Wiccan believe that negative images, such as the one presented on Fox news, are common and can affect individuals’ chances of promotions and their ability to take time from work to celebrate their religious holidays. However, there does appear to be a shift from Wiccans being seen as dangerous devil worshippers to being regarded as silly but harmless. Many Wiccans have been working to have their religion recognized as a legitimate and serious practice. They are active in inter-faith work and participate in the World Parliament of Religions.

religious freedom. Wiccans have won a number of court cases resulting in the pentagram being an accepted symbol on graves in military cemeteries, and, recently in California, the recognition that Wiccan prisoners must be provided with their own clergy (Dolan 2013). Nonetheless, there continues to be discrimination. For example, on Sunday, February 17, 2013 Friends of Fox anchors mocked Wicca when reporting that the University of Missouri recognized all Wiccan holidays (in reality only the Sabbats were recognized). The three anchors went on to proclaim Wiccans were either dungeons and dragons players or twice divorced middle-aged women who live in rural areas, are mid-wives and like incense. This portrait is both demeaning and inaccurate as all research indicates that while most Wiccans are women, they tend to live in urban and suburban areas and are as likely to be young as middle aged, and tend to be better educated than the general American public (Berger 2003:25-34). After a protest lead mostly by Selena Fox of Circle Sanctuary, the network apologized. Nonetheless most Wiccan believe that negative images, such as the one presented on Fox news, are common and can affect individuals’ chances of promotions and their ability to take time from work to celebrate their religious holidays. However, there does appear to be a shift from Wiccans being seen as dangerous devil worshippers to being regarded as silly but harmless. Many Wiccans have been working to have their religion recognized as a legitimate and serious practice. They are active in inter-faith work and participate in the World Parliament of Religions.

REFERENCES

Adler, Margot. 1978, 1986. Drawing Down the Moon. Boston: Beacon Press.

Berger, Helen., A. 2005. “Witchcraft and Neopaganism.”Pp 28-54 in Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America, edited by. H elen A. Berger, 28-54. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Berger, Helen A. 1999. A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-Paganism and Witchcraft in the United States. Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press.

Berger, Helen A. unpublished “The Pagan Census Revisited: an international survey of Pagans.

Berger, Helen. A., Evan A. Leach and Leigh S. Shaffer. 2003. Voices from the Pagan Census: Contemporary: A National Survey of Witches and Neo-Pagans in the United States. Columbia: SC: The University of South Carolina Press.

Buckland, Raymond. 1986. Buckland’s Complete Book or Witchcraft. St. Paul, Mn: Llewellyn Publications.

Clifton, Chas S. 2006. Her Hidden Children: The rise of Wicca and Paganism in America. Walnut Creek , CA: AltaMira Press.

Crowley, Vivianne. 2000. “Healing in Wicca.” Pp. 151-65 in Daughters of the Goddess: Studies of Healing, Identity, and Empowerment, edited by Wendy Griffin. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press

Cunningham, Scott. 1988. Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

Dolan, Maura. 2013 “ Court Revives Lawsuit Seeking Wiccan Chaplains in Women’s Prisons” Los Angeles Times , February 19. Accessed from http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2013/02/court-revives-lawsuit-over-wiccan-chaplains-in-womens-prisons.html on March 27, 2013.

Eilberg-Schwatz, Howard. 1989. “Witches of the West: Neo-Paganism and Goddess Worship as Enlightenment Religions.” Journal of Feminist Studies of Religion 5:77-95.

Griffin, Wendy. 2002. “Goddess Spirituality and Wicca.” Pp 243-81 in Her Voice, Her Faith: Women Speak on World Religions, edited by Katherine K. Young and Arvind Sharma. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hutton, Ronald . 2011 “Revisionism and Counter-Revisionism in Pagan History” The Pomegranate12:225-56

Hutton, Ronald. 1999. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, Aiden. A. 1991. Crafting the Art of Magic: Book I. St. Paul, MN: LLewellyn Publications.

Murray, Margaret A. 1921, 1971. The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Neitz, Mary-Jo. 1991. “In Goddess We Trust.” Pp.353-72 in In Gods We Trust edited by Thomas Robbins and Dick Anthony. New Brunswick NJ: Transaction Press.

Pike , Sarah . M. 2004. New Age and Neopagan Religions in America . New York: Columbia University Press.

Salomonsen, Jone. 2002. Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco. London: Routledge Press.

Smith, Christian with Melinda. L. Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Christian with Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starhawk. 1979. The Spiral Dance. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers

Tully, Caroline. 2011. ” Researching the Past is a Foreign Country: Cognitive Dissonance as a Response by Practitioner Pagans to Academic Research on the History of Pagan Religions.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, Orlando, FL.

Waldron, David. 2008. The Sign of the Witch: Modernity and the Pagan Revival. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Author:

Helen A. Berger

Post Date:

5 April 2013

cover story describing the Phoenix Goddess Temple as “nothing more than a New Age brothel” (Stern 2016), A police investigation of the Temple was then launched that led to the arrest of Elise [Image at right] and other Temple staff members and a shutdown of the temple in September 2011

cover story describing the Phoenix Goddess Temple as “nothing more than a New Age brothel” (Stern 2016), A police investigation of the Temple was then launched that led to the arrest of Elise [Image at right] and other Temple staff members and a shutdown of the temple in September 2011 levels and involve instruction from or interaction with a practitioner. Female practitioners are referred to as “goddesses” [Image at right] and generally assume goddess identities such as Shakti, Isis and Aphrodite. Male practitioners are commonly called “touch healers.” According to the Temple website, the church healers “seek to help women, men and couples discover their own divine connection between soul, light body and sacred vessel” and “offer group classes and one-on-one teachings and training, play shops and internships,” all meant to “make use of the gifts of the Goddess” and allow seekers to, among other things, “feel the light of your own soul” and “feel the chakra wheels spinning your self into physical existence.”

levels and involve instruction from or interaction with a practitioner. Female practitioners are referred to as “goddesses” [Image at right] and generally assume goddess identities such as Shakti, Isis and Aphrodite. Male practitioners are commonly called “touch healers.” According to the Temple website, the church healers “seek to help women, men and couples discover their own divine connection between soul, light body and sacred vessel” and “offer group classes and one-on-one teachings and training, play shops and internships,” all meant to “make use of the gifts of the Goddess” and allow seekers to, among other things, “feel the light of your own soul” and “feel the chakra wheels spinning your self into physical existence.” sessions and classes, and organizes events. [Image at right] Temple participants include guests (who seek information about the Temples activities), seekers (“who have a spiritual practice or have had in the past, and are now feeling led to find new sources of energy, direction and connection to the Higher Power”), initiates (“who have found genuine soul-food in our temple”), brothers and sisters (“who have decided to really support the Goddess Temples”), priests and priestesses (“who have a gift for channeling light into matter”), and healers and guides (who have “gifts to give as well as receive”) (Phoenix Goddess Temple n.d. “In Temple”).

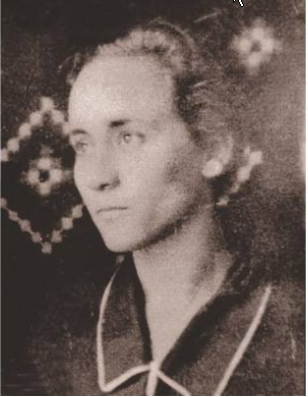

sessions and classes, and organizes events. [Image at right] Temple participants include guests (who seek information about the Temples activities), seekers (“who have a spiritual practice or have had in the past, and are now feeling led to find new sources of energy, direction and connection to the Higher Power”), initiates (“who have found genuine soul-food in our temple”), brothers and sisters (“who have decided to really support the Goddess Temples”), priests and priestesses (“who have a gift for channeling light into matter”), and healers and guides (who have “gifts to give as well as receive”) (Phoenix Goddess Temple n.d. “In Temple”). her final argument to the jury, she set up a small alter on the defense table”with pine cones and goddess figurines, then told the court that she was “letting the holy spirit guide me today through this trial” (Brinkman 2016). (Image at right) Finally, she sang the Star Spangled Banner just prior to being sentenced (Walsh 2016).

her final argument to the jury, she set up a small alter on the defense table”with pine cones and goddess figurines, then told the court that she was “letting the holy spirit guide me today through this trial” (Brinkman 2016). (Image at right) Finally, she sang the Star Spangled Banner just prior to being sentenced (Walsh 2016).

knowledge” there was no medical explanation for the cure. The theologians concluded that the boy had been healed through miraculous intercession. On December 19, 2011, the Holy Father authorized the promulgation of the decree recognizing the miracle attributed to the intercession of Kateri Tekakwitha. On October 21, 2012, her canonization was celebrated in Rome by Pope Benedict XVI in front of thousands of North American Native Catholics. Since 2012, more visitors have been coming to the shrine which is regarded as a pilgrimage center.

knowledge” there was no medical explanation for the cure. The theologians concluded that the boy had been healed through miraculous intercession. On December 19, 2011, the Holy Father authorized the promulgation of the decree recognizing the miracle attributed to the intercession of Kateri Tekakwitha. On October 21, 2012, her canonization was celebrated in Rome by Pope Benedict XVI in front of thousands of North American Native Catholics. Since 2012, more visitors have been coming to the shrine which is regarded as a pilgrimage center. Tekakwitha around the Church on October 20, 2014. The procession was followed by the testimonies of a person healed by the intercessory prayers to Saint Kateri. The ceremony concluded with the Our Father in the Mohawk language. The exact anniversary, October 21, began with the Eucharistic celebration; Ron Boyer narrated “The life of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.” Eucharistic Adoration and Benediction followed. In the afternoon, the Anointing with Saint Kateri’s relic and Blessed oil was offered, and the day closed on Our Father prayed in Mohawk.

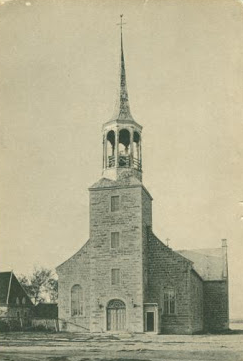

Tekakwitha around the Church on October 20, 2014. The procession was followed by the testimonies of a person healed by the intercessory prayers to Saint Kateri. The ceremony concluded with the Our Father in the Mohawk language. The exact anniversary, October 21, began with the Eucharistic celebration; Ron Boyer narrated “The life of Saint Kateri Tekakwitha.” Eucharistic Adoration and Benediction followed. In the afternoon, the Anointing with Saint Kateri’s relic and Blessed oil was offered, and the day closed on Our Father prayed in Mohawk. where a cemetery must have been. All of the buildings were constructed with grey Montreal stone. The old bell donated by King William IV of England stands on the left lawn on the street side. The Kateri Center, located in a nearby house, publishes the quarterly Kateri and administers all the activitites at the sanctuary.

where a cemetery must have been. All of the buildings were constructed with grey Montreal stone. The old bell donated by King William IV of England stands on the left lawn on the street side. The Kateri Center, located in a nearby house, publishes the quarterly Kateri and administers all the activitites at the sanctuary. rectangular white Carrara marble tomb bears the inscription: “Kaiatanoron Kateri Tekakwitha, 1656-1680”. Kaiatanoron means “blessed, precious and dear.”

rectangular white Carrara marble tomb bears the inscription: “Kaiatanoron Kateri Tekakwitha, 1656-1680”. Kaiatanoron means “blessed, precious and dear.” decades of conquest, being the allies of the British, the Iroquois were mostly evangelized by Protestant missionaries, and when New France became part of the British Empire, many Catholic Mohawks joined various Protestant denominations. This trend is also visible in their speaking English even though the reservation is located within French speaking Quebec. When in conflict with the Quebec authorities and police forces, they make a point of not speaking French as a sign of resistance (as occurred during the Oka Crisis that in 1990 involved Kahnawake and the Mercier Bridge that straddles part of it). Even if everything in the shrine is bilingual, it is connected historically to the French period of colonization and may have suffered from this.

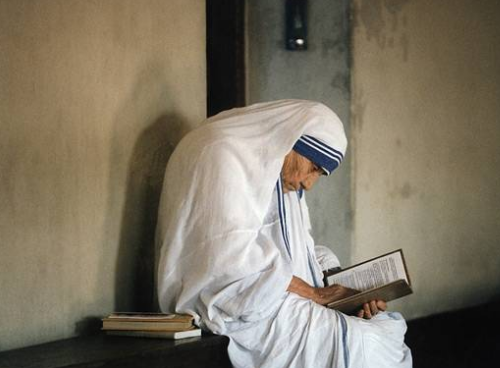

decades of conquest, being the allies of the British, the Iroquois were mostly evangelized by Protestant missionaries, and when New France became part of the British Empire, many Catholic Mohawks joined various Protestant denominations. This trend is also visible in their speaking English even though the reservation is located within French speaking Quebec. When in conflict with the Quebec authorities and police forces, they make a point of not speaking French as a sign of resistance (as occurred during the Oka Crisis that in 1990 involved Kahnawake and the Mercier Bridge that straddles part of it). Even if everything in the shrine is bilingual, it is connected historically to the French period of colonization and may have suffered from this. live her life for God and service to others. After a childhood and adolescence spent devoted to church activities, including singing, playing the mandolin, participating in a youth group, as well as teaching the catechism to younger members, in 1928, at eighteen years old, Agnes left her home to join the Loreto Sisters of Dublin. She first travelled to France to be interviewed, and when found suitable, was sent her to Ireland where she learned English and took the name “Mary Teresa,” for Saint Therese of Lisieux, the patron saint of missions (Greene 2008:17-18). In 1929, during her novitiate period, she was sent to Calcutta, India, to teach at St. Mary’s High School for Girls. During her time as a novice, she learned Bengali and Hindi, taught geography and history, and took her initial vows in 1931. When she took her final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in 1937, she also took the name “Mother,” to precede Teresa, as is the custom in the order of the Loreto Sisters.

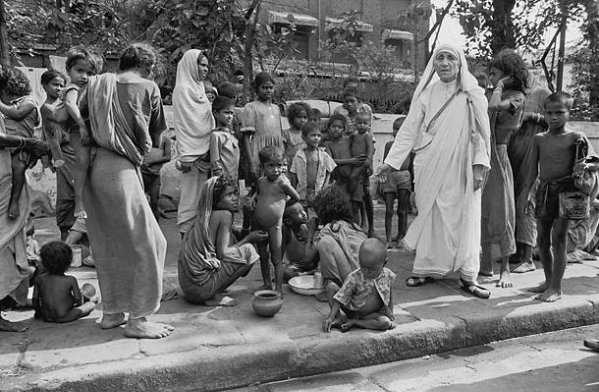

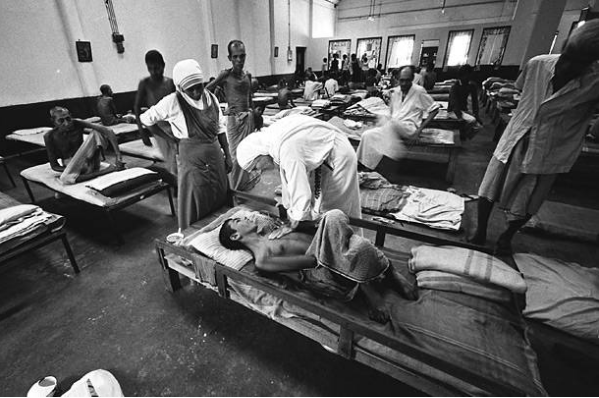

live her life for God and service to others. After a childhood and adolescence spent devoted to church activities, including singing, playing the mandolin, participating in a youth group, as well as teaching the catechism to younger members, in 1928, at eighteen years old, Agnes left her home to join the Loreto Sisters of Dublin. She first travelled to France to be interviewed, and when found suitable, was sent her to Ireland where she learned English and took the name “Mary Teresa,” for Saint Therese of Lisieux, the patron saint of missions (Greene 2008:17-18). In 1929, during her novitiate period, she was sent to Calcutta, India, to teach at St. Mary’s High School for Girls. During her time as a novice, she learned Bengali and Hindi, taught geography and history, and took her initial vows in 1931. When she took her final vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in 1937, she also took the name “Mother,” to precede Teresa, as is the custom in the order of the Loreto Sisters. impoverished adults, and opening a home for the dying, Mother Teresa had garnered financial as well as local community support. She obtained permission from the Vatican to start her own order with twelve other women who were either former students or teachers at St. Mary’s High School for Girls in Calcutta. They came to be called “Missionaries of Charity,” and were known for taking a fourth vow. After vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, the sisters of this new order also vowed to “give whole-hearted and free service to the poorest of the poor” (Greene 2008:48). Pope John Paul VI awarded Missionaries of Charity the Decree of Praise in 1965, which allowed the order to expand internationally. With the help of organized lay people and lay faithful, called Co-Workers, Missionaries of Charity opened over 600 hospices, schools, counseling services, medical care facilities, homeless shelters, orphanages, and programs for alcoholism and addiction in more than 120 countries by 1997. The Missionaries succeeded in reaching countries in six of the seven continents with their aid.

impoverished adults, and opening a home for the dying, Mother Teresa had garnered financial as well as local community support. She obtained permission from the Vatican to start her own order with twelve other women who were either former students or teachers at St. Mary’s High School for Girls in Calcutta. They came to be called “Missionaries of Charity,” and were known for taking a fourth vow. After vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, the sisters of this new order also vowed to “give whole-hearted and free service to the poorest of the poor” (Greene 2008:48). Pope John Paul VI awarded Missionaries of Charity the Decree of Praise in 1965, which allowed the order to expand internationally. With the help of organized lay people and lay faithful, called Co-Workers, Missionaries of Charity opened over 600 hospices, schools, counseling services, medical care facilities, homeless shelters, orphanages, and programs for alcoholism and addiction in more than 120 countries by 1997. The Missionaries succeeded in reaching countries in six of the seven continents with their aid. group to the Sisters, The Missionary of Charity Brothers, was established. Three years later Fr. Ian Travers-Ball (Brother Andrew), a Jesuit priest from Australia assumed leadership of the Brothers and headed the group for the first twenty years of its history. Contemplative branches of the Missionaries of Charity, sisters and brothers, were established in 1976 and 1979, respectively, and are devoted to prayer, penance and service. Daily routine in the contemplative branches involves substantial time devoted to prayer, spiritual reading, and silence. The Corpus Christi Movement for Priests was formed in 1981, after expressions of interest by a number of priests. Finally, in 1984, Mother Teresa co-founded the Missionaries of Charity Fathers with Friar Joseph Langford. Other organizations affiliated with the Missionaries of Charity include The Co-Workers of Mother Teresa, The Sick and Suffering Co-Workers, and The Lay Missionaries of Charity (Greene 2008:140).

group to the Sisters, The Missionary of Charity Brothers, was established. Three years later Fr. Ian Travers-Ball (Brother Andrew), a Jesuit priest from Australia assumed leadership of the Brothers and headed the group for the first twenty years of its history. Contemplative branches of the Missionaries of Charity, sisters and brothers, were established in 1976 and 1979, respectively, and are devoted to prayer, penance and service. Daily routine in the contemplative branches involves substantial time devoted to prayer, spiritual reading, and silence. The Corpus Christi Movement for Priests was formed in 1981, after expressions of interest by a number of priests. Finally, in 1984, Mother Teresa co-founded the Missionaries of Charity Fathers with Friar Joseph Langford. Other organizations affiliated with the Missionaries of Charity include The Co-Workers of Mother Teresa, The Sick and Suffering Co-Workers, and The Lay Missionaries of Charity (Greene 2008:140). States Senators during the 1980s Savings and Loan crisis. The Missionaries of Charity has also been accused of allowing and ignoring squalid conditions to persist at Charity supported facilities, such as hospices and orphanages, while refusing to make public accountings of their expenditures of funds to support these facilities (Hitchens 1995). As one critic reported, “The donations rolled in and were deposited in the bank, but they had no effect on our ascetic lives and very little effect on the lives of the poor we were trying to help” (Shields 1998). Another critic has alleged that homes for the dying run by the Missionaries of Charity are known for having a lack of doctors to properly diagnose patients’ illnesses, using previously used or unsanitary hypodermic needles, refusing to administer pain killers to those in excruciating pain, and otherwise relying on outdated and dangerous medical practices (Fox 1994). An undercover volunteer authored reports of abusive treatment of children; he reports having seen children bound, force-fed, and left outside at night during monsoon rains (MacIntyre 2005). In addition to criticism from the medical personnel and investigative journalists, former co-workers and former Sisters in the Missionaries of Charity, including Colette Livermore (2008), have written similar accounts of the poor treatment of the suffering the Sisters were ostensibly committed to helping. According to Fox (1994), the Missionaries of Charity justify what would appear to be the furthering of suffering of the needy, abandoned, and afflicted, as reflecting Mother Teresa’s teaching that suffering brings one closer to Jesus. She allegedly has equated the suffering of man with that of Christ and therefore a gift. This “theology of suffering,” has caused the disillusionment among a number of former co-workers and Sisters (Livermore 2008), and caused skepticism about the organizations commitment to the fourth vow of “wholehearted and free service to the poorest of the poor.”

States Senators during the 1980s Savings and Loan crisis. The Missionaries of Charity has also been accused of allowing and ignoring squalid conditions to persist at Charity supported facilities, such as hospices and orphanages, while refusing to make public accountings of their expenditures of funds to support these facilities (Hitchens 1995). As one critic reported, “The donations rolled in and were deposited in the bank, but they had no effect on our ascetic lives and very little effect on the lives of the poor we were trying to help” (Shields 1998). Another critic has alleged that homes for the dying run by the Missionaries of Charity are known for having a lack of doctors to properly diagnose patients’ illnesses, using previously used or unsanitary hypodermic needles, refusing to administer pain killers to those in excruciating pain, and otherwise relying on outdated and dangerous medical practices (Fox 1994). An undercover volunteer authored reports of abusive treatment of children; he reports having seen children bound, force-fed, and left outside at night during monsoon rains (MacIntyre 2005). In addition to criticism from the medical personnel and investigative journalists, former co-workers and former Sisters in the Missionaries of Charity, including Colette Livermore (2008), have written similar accounts of the poor treatment of the suffering the Sisters were ostensibly committed to helping. According to Fox (1994), the Missionaries of Charity justify what would appear to be the furthering of suffering of the needy, abandoned, and afflicted, as reflecting Mother Teresa’s teaching that suffering brings one closer to Jesus. She allegedly has equated the suffering of man with that of Christ and therefore a gift. This “theology of suffering,” has caused the disillusionment among a number of former co-workers and Sisters (Livermore 2008), and caused skepticism about the organizations commitment to the fourth vow of “wholehearted and free service to the poorest of the poor.” Holy See, governed by Pope John Paul II, started the process in 1997. She was beatified in 2003, making her known to the Catholic community as “Blessed” Mother Teresa. The Holy See also abandoned the process of adversarial investigation, a process to critically explore her extraordinary work. Two miracles, involving the personal intercession of Mother Teresa, are also required as part of the process of consideration for sainthood. There is currently only one claim of a miracle, made by a Bengali woman who maintains that she was miraculously healed after holding a locket with a picture of Mother Teresa to her abdomen. However, this one claim is contested as both the woman’s husband and the attending physician insist that the woman’s cysts were cured after nearly a year of medication and treatment (Rohde 2003).

Holy See, governed by Pope John Paul II, started the process in 1997. She was beatified in 2003, making her known to the Catholic community as “Blessed” Mother Teresa. The Holy See also abandoned the process of adversarial investigation, a process to critically explore her extraordinary work. Two miracles, involving the personal intercession of Mother Teresa, are also required as part of the process of consideration for sainthood. There is currently only one claim of a miracle, made by a Bengali woman who maintains that she was miraculously healed after holding a locket with a picture of Mother Teresa to her abdomen. However, this one claim is contested as both the woman’s husband and the attending physician insist that the woman’s cysts were cured after nearly a year of medication and treatment (Rohde 2003). and organizations, she has become a prominent and much loved figure in India, the Catholic community, and all over the world. In 1971, Mother Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize for “bringing help to suffering humanity.” She was also awarded honors such as India’s Padma Shri and the Jawajarlal Nehru Award for International Understanding, England’s Order of Merit, the Gold Medal of the Soviet Peace Committee, the United States Congressional Gold Medal, along with over a hundred other awards, including honorary degrees from a number of other countries and organizations for her endeavors with Missionaries of Charity. Perhaps the most impressive indicator of widespread respect for Mother Teresa is that she was ranked first in the United States’ 1999 Gallup Poll’s List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20 th Century, ahead of luminaries such as Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, and Pope John Paul II.

and organizations, she has become a prominent and much loved figure in India, the Catholic community, and all over the world. In 1971, Mother Teresa received the Nobel Peace Prize for “bringing help to suffering humanity.” She was also awarded honors such as India’s Padma Shri and the Jawajarlal Nehru Award for International Understanding, England’s Order of Merit, the Gold Medal of the Soviet Peace Committee, the United States Congressional Gold Medal, along with over a hundred other awards, including honorary degrees from a number of other countries and organizations for her endeavors with Missionaries of Charity. Perhaps the most impressive indicator of widespread respect for Mother Teresa is that she was ranked first in the United States’ 1999 Gallup Poll’s List of Most Widely Admired People of the 20 th Century, ahead of luminaries such as Martin Luther King, Albert Einstein, and Pope John Paul II. the elder. He was born with the name Aristide Pierre Maurin in Oultet, France in 1877, the son of French peasant farmers and one of 24 children. Born into a Catholic family, as a young man he considered religious life, joining the Christian Brothers. A creative yet quiet person inspired by French personalist philosophy, especially the work of Emmanuel Mounier, Maurin sought to live a simple and dignified life of manual labor. In 1909, he migrated to Canada and later to the U.S., working in a variety of jobs as a manual laborer, which eventually brought him to New York City.

the elder. He was born with the name Aristide Pierre Maurin in Oultet, France in 1877, the son of French peasant farmers and one of 24 children. Born into a Catholic family, as a young man he considered religious life, joining the Christian Brothers. A creative yet quiet person inspired by French personalist philosophy, especially the work of Emmanuel Mounier, Maurin sought to live a simple and dignified life of manual labor. In 1909, he migrated to Canada and later to the U.S., working in a variety of jobs as a manual laborer, which eventually brought him to New York City. in Staten Island, New York. When she voiced her desire to convert to Catholicism and to have their baby baptized, Forster, an atheist who wanted little to do with religion, urged her not to go through with it. The two ended up separating, an experience that Day later described as one of the most painful decisions of her life: choosing the Church over her love for Forster.

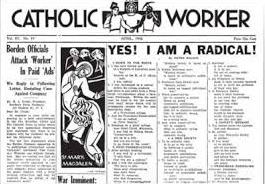

in Staten Island, New York. When she voiced her desire to convert to Catholicism and to have their baby baptized, Forster, an atheist who wanted little to do with religion, urged her not to go through with it. The two ended up separating, an experience that Day later described as one of the most painful decisions of her life: choosing the Church over her love for Forster. personal sacrifice. Over time, their efforts grew into a group of volunteers who lived in a Lower East Side building (eventually called “St. Joseph House”) with people seeking shelter from the streets, running a daily soup line that often stretched down the block and publishing pieces in The Catholic Worker newspaper critiquing the social, spiritual, and personal crises underlying problems, such as poverty and racism. Over time, the newspaper (and the Catholic Worker community) became focused on issues of violence and militarism as well, with the group’s pacifist stance and nonviolent civil disobedience becoming more central to its existence during the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Vietnam War, and into present time.

personal sacrifice. Over time, their efforts grew into a group of volunteers who lived in a Lower East Side building (eventually called “St. Joseph House”) with people seeking shelter from the streets, running a daily soup line that often stretched down the block and publishing pieces in The Catholic Worker newspaper critiquing the social, spiritual, and personal crises underlying problems, such as poverty and racism. Over time, the newspaper (and the Catholic Worker community) became focused on issues of violence and militarism as well, with the group’s pacifist stance and nonviolent civil disobedience becoming more central to its existence during the Spanish Civil War, World War II, the Vietnam War, and into present time. newspapers describing their work, began to spring up around the United States. By 1940, over thirty Catholic Worker communities were formed by local groups around the country interested in the kind of work that Day and Maurin described in their newspaper. The movement’s growth was, and has continued to be, decentralized and unorganized. No one’s permission is needed to start a Catholic Worker community, nor do incarnations of Catholic Worker vision and practice need to follow a particular set of rules or models. Indeed, Day’s anarchist past nurtured her commitment to a movement that was informed by those directly involved, which left room for spontaneity and creativity rather than authority and leadership dictating the boundaries for communities. While the de facto leaders of different communities were sometimes familiar with each other, connections between different Catholic Worker communities rarely extended beyond informal friendships.

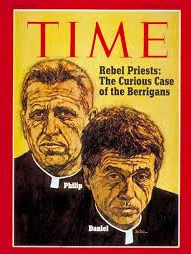

newspapers describing their work, began to spring up around the United States. By 1940, over thirty Catholic Worker communities were formed by local groups around the country interested in the kind of work that Day and Maurin described in their newspaper. The movement’s growth was, and has continued to be, decentralized and unorganized. No one’s permission is needed to start a Catholic Worker community, nor do incarnations of Catholic Worker vision and practice need to follow a particular set of rules or models. Indeed, Day’s anarchist past nurtured her commitment to a movement that was informed by those directly involved, which left room for spontaneity and creativity rather than authority and leadership dictating the boundaries for communities. While the de facto leaders of different communities were sometimes familiar with each other, connections between different Catholic Worker communities rarely extended beyond informal friendships. and behavior in the gospels as being nonviolent (e.g., turn the other cheek) while also disrupting the status quo (e.g., when Jesus overturned the tables of the temple money lenders). During the Vietnam War, Catholic priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan (friends of the Catholic Worker) staged draft card burnings inspired by their Catholic faith. The Worker’s support of the Berrigans and similar anti-war activists solidified its reputation as a major force of nonviolent activism, opposition to war, and Catholic peace activism during a period when many young people had become disillusioned by war and violence. Increasingly, Catholic Worker communities around the country began to attract war resisters looking for communities where their views would be supported, especially if they were Catholics, since the Catholic Church’s official teachings were much more open to war and violence in certain circumstances.

and behavior in the gospels as being nonviolent (e.g., turn the other cheek) while also disrupting the status quo (e.g., when Jesus overturned the tables of the temple money lenders). During the Vietnam War, Catholic priests Philip and Daniel Berrigan (friends of the Catholic Worker) staged draft card burnings inspired by their Catholic faith. The Worker’s support of the Berrigans and similar anti-war activists solidified its reputation as a major force of nonviolent activism, opposition to war, and Catholic peace activism during a period when many young people had become disillusioned by war and violence. Increasingly, Catholic Worker communities around the country began to attract war resisters looking for communities where their views would be supported, especially if they were Catholics, since the Catholic Church’s official teachings were much more open to war and violence in certain circumstances. appointments, while someone else makes dinner for the community, which always begins at 5 PM. Someone from Maryhouse, the other New York City house of hospitality located two blocks away, comes with a grocery cart to pick up their portion of the dinner. After everyone is finished eating, the dishes must be done, tables cleaned, and floors mopped. On Tuesday nights, these rituals are followed by a Catholic mass: a priest comes to the house each week just for the occasion. On Friday nights, they are followed by open-to-the-public “Friday night meetings” on topics varying from the spirituality of St. Teresa of Avila to the prison at Guantanamo Bay.

appointments, while someone else makes dinner for the community, which always begins at 5 PM. Someone from Maryhouse, the other New York City house of hospitality located two blocks away, comes with a grocery cart to pick up their portion of the dinner. After everyone is finished eating, the dishes must be done, tables cleaned, and floors mopped. On Tuesday nights, these rituals are followed by a Catholic mass: a priest comes to the house each week just for the occasion. On Friday nights, they are followed by open-to-the-public “Friday night meetings” on topics varying from the spirituality of St. Teresa of Avila to the prison at Guantanamo Bay. each community’s rituals differ as well. Some do not hold regular masses at their houses of hospitality. Some are not regularly involved in civil disobedience. However, most have some form of a meal shared with the homeless and other impoverished populations: if there is any ritual common to most communities, it would be this type of activity. The rituals of shared meals, shared time in jail, shared celebration of mass, and others not only enable Catholic Workers to live out their beliefs but also serve to bind them together, creating close-knit communities.

each community’s rituals differ as well. Some do not hold regular masses at their houses of hospitality. Some are not regularly involved in civil disobedience. However, most have some form of a meal shared with the homeless and other impoverished populations: if there is any ritual common to most communities, it would be this type of activity. The rituals of shared meals, shared time in jail, shared celebration of mass, and others not only enable Catholic Workers to live out their beliefs but also serve to bind them together, creating close-knit communities. people at any one time) includes regular volunteers as well as people who attend Friday Night Meetings, house masses, or other community activities. In terms of wider interest and support, the community’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, has over 20,000 subscribers around the country. The community is financed entirely through private donations from individual supporters, who might loosely be considered part of the movement due to their support of its ongoing work.

people at any one time) includes regular volunteers as well as people who attend Friday Night Meetings, house masses, or other community activities. In terms of wider interest and support, the community’s newspaper, The Catholic Worker, has over 20,000 subscribers around the country. The community is financed entirely through private donations from individual supporters, who might loosely be considered part of the movement due to their support of its ongoing work. donors happy. There is a history of this refusal to compromise within the movement. As mentioned earlier, during World War II, Dorothy Day wrote in The Catholic Worker newspaper about her unwillingness to compromise her pacifist stance on the war. Her views were very unpopular, and the paper lost thousands of subscribers (and donors) as a result. Still, Day was convinced that she was right and that God would provide for the community in other ways, and the community survived that period and other rough periods in its history.

donors happy. There is a history of this refusal to compromise within the movement. As mentioned earlier, during World War II, Dorothy Day wrote in The Catholic Worker newspaper about her unwillingness to compromise her pacifist stance on the war. Her views were very unpopular, and the paper lost thousands of subscribers (and donors) as a result. Still, Day was convinced that she was right and that God would provide for the community in other ways, and the community survived that period and other rough periods in its history. Congregational Church her family was attending when she came of age, but only after informing the pastor that she did not subscribe to the doctrines of either the fall or predestination (Eddy 1892).

Congregational Church her family was attending when she came of age, but only after informing the pastor that she did not subscribe to the doctrines of either the fall or predestination (Eddy 1892). the alternative medicine treatments popular at the time, including hydropathy (water cure) and Sylvester Graham’s nutritional system. In 1862, she heard of healer Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and traveled to his practice in Maine. Quimby had studied mesmerism and developed his own system for healing, sometimes called, Mind Cure. The cure rested on the idea that since illness arose in the mind, freeing the mind of diseased thought would lead to healing.

the alternative medicine treatments popular at the time, including hydropathy (water cure) and Sylvester Graham’s nutritional system. In 1862, she heard of healer Phineas Parkhurst Quimby and traveled to his practice in Maine. Quimby had studied mesmerism and developed his own system for healing, sometimes called, Mind Cure. The cure rested on the idea that since illness arose in the mind, freeing the mind of diseased thought would lead to healing. Version of the Bible , constitutes the core of Christian Science theology and practice. Over the years, Eddy produced over four hundred editions of what she called the Christian Science textbook.

Version of the Bible , constitutes the core of Christian Science theology and practice. Over the years, Eddy produced over four hundred editions of what she called the Christian Science textbook. women pastors of the branch churches with this text and the Bible. She continued developing the church organization and produced the first edition of the Manual of the Mother Church in 1895. A comprehensive text, it contains rules determining all functions of the organization from the order of worship in services to the election of the Board of Directors. The material in the 1908 Manual (the last version) cannot be changed without the permission of Mary Baker Eddy.

women pastors of the branch churches with this text and the Bible. She continued developing the church organization and produced the first edition of the Manual of the Mother Church in 1895. A comprehensive text, it contains rules determining all functions of the organization from the order of worship in services to the election of the Board of Directors. The material in the 1908 Manual (the last version) cannot be changed without the permission of Mary Baker Eddy. not subject to sickness, sin, or death since these are not part of God’s creation and hence are not real. To realize that the creation is spiritual, not material, is to exist in the reflection of God and to be well. To be sure, people can feel ill, but this is an error of the material sense.

not subject to sickness, sin, or death since these are not part of God’s creation and hence are not real. To realize that the creation is spiritual, not material, is to exist in the reflection of God and to be well. To be sure, people can feel ill, but this is an error of the material sense. trained through a twelve session course, The Primary Class, that was designed by Mary Baker Eddy and is offered by church approved teachers. According to one of the church’s websites, Healing Unlimited, authorized practitioners are considered professionals by the church and charge for their services, which focus on the prayerful resolution of problems that include “the whole spectrum of human fears, griefs, wants, sins, and ills. Practitioners are called upon to give Christian Science treatment not only in cases of physical disease and emotional disturbance, but in family and financial difficulties, business problems, questions of employment, schooling, professional advancement, theological confusion, and so forth” (Healing Unlimited 2012). Practitioners work with individuals seeking Christian Science healing by praying with and for them and guiding them to appropriate passages in Science and Health and the Bible.

trained through a twelve session course, The Primary Class, that was designed by Mary Baker Eddy and is offered by church approved teachers. According to one of the church’s websites, Healing Unlimited, authorized practitioners are considered professionals by the church and charge for their services, which focus on the prayerful resolution of problems that include “the whole spectrum of human fears, griefs, wants, sins, and ills. Practitioners are called upon to give Christian Science treatment not only in cases of physical disease and emotional disturbance, but in family and financial difficulties, business problems, questions of employment, schooling, professional advancement, theological confusion, and so forth” (Healing Unlimited 2012). Practitioners work with individuals seeking Christian Science healing by praying with and for them and guiding them to appropriate passages in Science and Health and the Bible.  music; other music includes a performance by a paid soloist and hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal. There are no clergy in Christian Science; instead the service is led by a First and Second Reader who are elected for a three year term. The First Reader, always a female, opens the service with a brief statement and reads from Science and Health. The Second reader, a male, reads from the King James Version of the Bible. The passages are prescribed by an anonymous committee in Boston. The Bible Lesson, used in all churches, is read by the First and Second Readers. Through the Christian Science Quarterly, congregants have access to the weekly Bible and Science and Health passages along with the Bible Lesson in advance and can study them prior to attending the Sunday service.

music; other music includes a performance by a paid soloist and hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal. There are no clergy in Christian Science; instead the service is led by a First and Second Reader who are elected for a three year term. The First Reader, always a female, opens the service with a brief statement and reads from Science and Health. The Second reader, a male, reads from the King James Version of the Bible. The passages are prescribed by an anonymous committee in Boston. The Bible Lesson, used in all churches, is read by the First and Second Readers. Through the Christian Science Quarterly, congregants have access to the weekly Bible and Science and Health passages along with the Bible Lesson in advance and can study them prior to attending the Sunday service. which states that “ The Church officers shall consist of the Pastor Emeritus, a Board of Directors, a President, a Clerk, a Treasurer, and two Readers” (Eddy 1910). Mary Baker Eddy is the Pastor Emeritus; she abolished the role of pastor completely in 1894 so there are no Christian Science clergy. Baker Eddy included several committees in her institutionalization of the church. These include the Board of Education and the Board of Lectureship. The Committee on Publication was tasked by Eddy with directly addressing any misinformation appearing about Christian Science. Branch churches are administered by their local members who must abide by the Manual. No emendations to the Manual (or the by-laws) can occur without the written permission of Mary Baker Eddy.

which states that “ The Church officers shall consist of the Pastor Emeritus, a Board of Directors, a President, a Clerk, a Treasurer, and two Readers” (Eddy 1910). Mary Baker Eddy is the Pastor Emeritus; she abolished the role of pastor completely in 1894 so there are no Christian Science clergy. Baker Eddy included several committees in her institutionalization of the church. These include the Board of Education and the Board of Lectureship. The Committee on Publication was tasked by Eddy with directly addressing any misinformation appearing about Christian Science. Branch churches are administered by their local members who must abide by the Manual. No emendations to the Manual (or the by-laws) can occur without the written permission of Mary Baker Eddy. Rooms where material approved by the Board of Directors would be available to the public to read free of charge. Staffed by Christian Scientist volunteers, the Reading Rooms also distribute copies of Christian Science materials.

Rooms where material approved by the Board of Directors would be available to the public to read free of charge. Staffed by Christian Scientist volunteers, the Reading Rooms also distribute copies of Christian Science materials. featured poorly researched articles about Eddy. A scathing fourteen-installment series by Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine appeared in McClure’s Magazine between 1906 and 1908. In response to what she believed were unfair press reports, Eddy founded the Christian Science Monitor in 1908 in order to print the news fairly and thoroughly. Ironically, the Monitor has gone on to win several Pulitzer Prizes.

featured poorly researched articles about Eddy. A scathing fourteen-installment series by Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine appeared in McClure’s Magazine between 1906 and 1908. In response to what she believed were unfair press reports, Eddy founded the Christian Science Monitor in 1908 in order to print the news fairly and thoroughly. Ironically, the Monitor has gone on to win several Pulitzer Prizes. of Bliss Knapp emerged. Knapp had been a devoted follower of Eddy and had written a book in 1947, The Destiny of the Mother Church , which proclaimed Eddy to be the Second Coming of Christ (Knapp 1991). In light of the large amount of funding this would bring to the recently diminished church coffers, the Board of Directors agreed to publish the book. Many Christian Scientists took issue with this decision and several protesting groups coalesced. This was not the first time the issue of who exactly Eddy was had presented itself, and Eddy herself had prohibited what she called “deification of personality” when she felt some followers where aligning her too closely with Jesus (Eddy 1894). The protestors saw Eddy’s prohibition of “deification” as clearly precluding publication of the Knapp text. The Board excommunicated several vocal protesters, a move that was rare but not unprecedented. Several key staff resigned, and the Board found themselves in a very contentious Annual Meeting in 1993. Ultimately, the Board left the decision of whether or not to carry and/or sell the Knapp book up to the local Christian Science Reading Rooms, and published a wide range of other biographies of Eddy. By the time the Mary Baker Eddy Library and archives opened in 2002, the protests were subsiding.