WICCA

WICCA TIMELINE

1951 The 1735 Witchcraft Laws, which had made the practice of Witchcraft a crime in Great Britain, were abolished.

1951 The Witchcraft Museum on the Isle of Man opened with backing from Gerald Gardner.

1954 Gardner published the first non-fiction book on Wicca, Witchcraft Today .

1962 Raymond and Rosemary Buckland, initiated Witches, came to the United States and began training others.

1971 The first feminist coven was formed in California by Zsuzsanna Budapest.

1979 Starhawk published The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess .

1986 Raymond Buckland published the Complete Book of Witchcraft.

1988 Scott Cunningham published Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner .

2007 The United States Armed Services permitted the Wicca pentagram to be placed on graves in military cemeteries.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Gerald Gardner, a British civil servant, is credited with the creation of Wicca, although some disagreement continues to swirl around whether or not that is true. Gardner contended that he was initiated into the New Forest Coven, by Dorothy Clutterbuck in 1939. Members of this coven claimed that theirs was a traditional Wiccan coven whose rituals and practices had been passed down since pre- Christian times.

around whether or not that is true. Gardner contended that he was initiated into the New Forest Coven, by Dorothy Clutterbuck in 1939. Members of this coven claimed that theirs was a traditional Wiccan coven whose rituals and practices had been passed down since pre- Christian times.

In 1951, laws prohibiting the practice of witchcraft in England were repealed, and soon thereafter, in 1954, Gardner published his first non-fiction book, Witchcraft Today (Berger 2005:31). His account came into question, first by an American practitioner Aiden Kelly (1991) and subsequently by others (Hutton 1999; Tully 2011) Hutton (1999), a historian who wrote the most comprehensive book on the development of Wicca, claims that Gardner did something more profound than merely codifying and making public a hidden old religion: he created a new vibrant religion that has spread around the world. Gardner was helped in this endeavor by Doreen Valiente, who wrote much of the poetry used in the rituals, thereby helping to make them more spiritually moving (Griffin 2002:244).

Some of Gardner’s students or students of those trained by him, such as Alex and Maxine Saunders, created variations of Gardner’s spiritual and ritual system, spurring new sects or forms of Wicca to develop. From the beginning there were some who claimed to have been initiated into other covens that had been underground for centuries. None of these garnered either the success of Gardner’s version or the scrutiny. It is most probable that some of them were influenced by many of the same social influences that had informed Gardner, including the Western occult or magical tradition, folklore and the romantic tradition, Freemasonry, and the long tradition of village folk healers or wise people (Hutton 1999).

It has typically been believed that British immigrants Raymond and Rosemary Buckland brought Wicca to the United States. But, the history is actually more complex as evidence suggests that copies of Gardner’s fictional account of Witchcraft and his non-fiction book, Witchcraft Today were brought over to the United States prior to the arrival of the Bucklands (Clifton 2006:15). Nonetheless the Bucklands were important in the importation of the religion as they created the first Wiccan coven in the United States and initiated others. Once on American soil, the religion became attractive to feminists looking for a female face of the divine and environmentalists who were drawn to the celebration of the seasonal cycles. Both movements, in turn, helped to transform the religion. Although the Goddess was celebrated, the coven led by the High Priestess Gardner had not developed a feminist form of spirituality. It was common, for example, for the High Priestess to be required to step down when she was no longer young (Neitz 1991:353).

Miriam Simos, who writes under her magical name, Starhawk, was instrumental in bringing feminism and feminist concerns to  Wicca. She was initiated into the Fairie Tradition of Witchcraft and into Zsuzsanna Budapest’s Feminist Spirituality group. Starhawk’s first book, The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (1979), which brought together both threads of her training, sold over 300,000 copies.(Salomonsen 2002:9). During this same period the religion went from a mystery religion (one in which sacred and magical knowledge is reserved for initiates), with a focus on fertility, to an earth based religion (one that came to see the earth as a manifestation of the Goddess — alive and sacred) ( Clifton 2006:41). These two changes helped to make the religion appealing to those touched by feminism and environmentalism both in the United States and abroad. The religion’s spread was further aided by the publication of relatively inexpensive books and journals and the growth of the Internet.

Wicca. She was initiated into the Fairie Tradition of Witchcraft and into Zsuzsanna Budapest’s Feminist Spirituality group. Starhawk’s first book, The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess (1979), which brought together both threads of her training, sold over 300,000 copies.(Salomonsen 2002:9). During this same period the religion went from a mystery religion (one in which sacred and magical knowledge is reserved for initiates), with a focus on fertility, to an earth based religion (one that came to see the earth as a manifestation of the Goddess — alive and sacred) ( Clifton 2006:41). These two changes helped to make the religion appealing to those touched by feminism and environmentalism both in the United States and abroad. The religion’s spread was further aided by the publication of relatively inexpensive books and journals and the growth of the Internet.

Initially the Bucklands, following Gardner’s dictate, claimed that a neophyte needed to be trained by a third degree Wiccan, someone who had been trained in a coven and gone through three levels or degrees of training, similar to those in the Freemasons. However, Raymond Buckland changed his position on this. He eventually published a book and created a video explaining how individuals could self-initiate. Others, most notably Scott Cunningham, also wrote how-to books that resulted in self-initiation becoming common. Wicca: A Guide for Solitary Practice (Cunningham 1988) alone has sold over 400,000 copies. His book and other how-to books have helped to fuel the trend toward most Wiccans practicing alone. The large number of Internet sites and the growth of umbrella groups (that is, groups that provide information, open ritual, and at times religious retreats, referred to as festivals) make it possible for Wiccans and other Pagans to maintain contact with others whether they practice in a coven or alone. The growth of these books and websites helped to make Wicca less of a mystery religion. Initially it was in the coven that esoteric knowledge was taught, often as secret knowledge that could only be passed on to others who were initiated into the religion. Little, if any, of the rituals or knowledge now remains secret.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Belief in Wicca is less important than experience of the divine or magic. It is common for Wiccans to say they don’t believe in the Goddess (es) and God(s); they experience them. It is through ritual and meditation that they gain this experience of the divine and perform magical acts. The religion is non-doctrinal, with the Wiccan Rede “Do as thou will as long as thou harm none” being the only hard and fast rule. The religion, according to Gardner, existed throughout Europe prior to the advent to Christianity. In Gardner’s presentation, the Goddess and the God balance what he called male and female energies. Groups, referred to as covens, are ideally to mimic that balance by being composed of six women and six men with an additional woman who is High Priestess. One of the men in the group serves as the High Priest but the Priestess is the group leader. In actuality few covens have this exact number of participants, although most are small groups (Berger 1999:11-12).

The ritual calendar is based on an agricultural calendar that emphasizes fertility. This emphasis is reflected in the changing

relationship between the Goddess and the God as portrayed in the rituals. The Goddess is viewed as eternal but changing from the maid, to mother, to crone; then, in the spiral of time, she returns in the spring as a young woman. The God is born of the mother in midwinter, becomes her consort in the spring, dies to ensure the growth of crops in the fall; then he is reborn at the winter solstice. The God is portrayed with horns, a sign of virility. The image is an old one that was converted to the image of the Devil within Christianity. All goddesses are viewed as aspects of the one Goddess just as all gods are believed to be aspects of the one God.

relationship between the Goddess and the God as portrayed in the rituals. The Goddess is viewed as eternal but changing from the maid, to mother, to crone; then, in the spiral of time, she returns in the spring as a young woman. The God is born of the mother in midwinter, becomes her consort in the spring, dies to ensure the growth of crops in the fall; then he is reborn at the winter solstice. The God is portrayed with horns, a sign of virility. The image is an old one that was converted to the image of the Devil within Christianity. All goddesses are viewed as aspects of the one Goddess just as all gods are believed to be aspects of the one God.

The image of Wicca as the old religion, led by women, that celebrated fertility of the land, animals and people was taken by Gardner from Margaret Murray (1921), who wrote the foreword to his book. She argued that the witch trials were an attack on practitioners of the old religion by Christianity. Gardner took from Murray the image of witches of the past as healers who used their knowledge of herbs and magic to help individuals in their community deal with illness, infertility and other problems. At the time that Gardner was writing, Murray was considered an expert on the witch trials, although her work subsequently came under attack and is no longer accepted by historians.

Magic and magical practices are integrated into the belief system of Wiccans. The magical system is one that is based on the work of Aleister Crowley, who codified Western esoteric knowledge. He defined magic as the act of changing reality to will. Magical practices have waxed and waned in the West but have never disappeared (Pike 2004). They can be traced back to twelfth century appropriations of the Cabbala and ancient Greek practices by Christianity and were important during the scientific revolution (Waldron 2008:101).

Within Wiccan rituals, a form of energy is believed to be raised through dancing, chanting, meditation, or drumming, which can be directed toward a cause, such as healing someone or finding a job, parking place, or rental apartment. It is believed that the energy that an individual sends out will return to her/him three-fold and hence the most common form of magic is healing magic. Performing healing both helps to show that the Witch has magical power and that s/he uses it for good ( Crowley 2000:151-56). For Wiccans the world is viewed as magical. It is commonly believed that the Goddess or the God may send an individual a sign or give them direction in life. These may come during a ritual or meditation or in the course of everyday life as people happen upon old friends or find something in the sand at the beach that they believe is of import. Magic therefore is a way of connecting with the divine and with nature. Magic is viewed as part of the natural world and indicative of individuals’ connection to nature, to one another, and to the divine.

directed toward a cause, such as healing someone or finding a job, parking place, or rental apartment. It is believed that the energy that an individual sends out will return to her/him three-fold and hence the most common form of magic is healing magic. Performing healing both helps to show that the Witch has magical power and that s/he uses it for good ( Crowley 2000:151-56). For Wiccans the world is viewed as magical. It is commonly believed that the Goddess or the God may send an individual a sign or give them direction in life. These may come during a ritual or meditation or in the course of everyday life as people happen upon old friends or find something in the sand at the beach that they believe is of import. Magic therefore is a way of connecting with the divine and with nature. Magic is viewed as part of the natural world and indicative of individuals’ connection to nature, to one another, and to the divine.

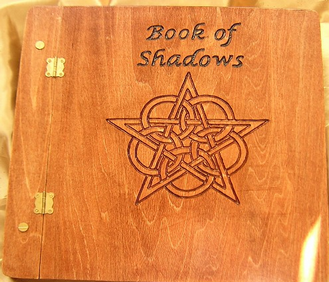

Wiccans traditionally keep a Book of Shadows, which includes rituals and magical incantations that have worked for them. It is common for the High Priestess and High Priest, leaders of the coven, to share their Book of Shadows with those they are initiating, permitting them to copy some rituals entirely. Each Book of Shadows is unique to the Wiccan who has created it and often is a work of art in its own right.

Most, although not all, Wiccans believe in reincarnation (Berger et al 2003:47). The dead are believed to go to Summerland between lives, a place where their soul or essence has a chance to reflect on the life they lived before rejoining the world again to continue their spiritual growth. Karma of their past actions will influence their placement in their new life. But, unlike Eastern concepts of reincarnation that emphasize the desire to end this cycle of birth, death and reincarnation, returning to life is viewed positively by Wiccans. The inner being is able to interact again with those who were important in past lives, learn and evolve spiritually.

RITUALS

Within Wicca, rituals are more important than beliefs as they help put the practitioner in touch with spiritual or magical elements. The major rituals involve the circle of the year (the eight sabbats that occur six weeks apart throughout the year) and are conducted on the solstices, equinoxes and what are known as the cross days between them. These commemorate the beginning and height of each season and the changing relationship between the God and the Goddess. Birth, growth, and death are all seen as a natural part of the cycle and are celebrated. The changes in nature are believed to be reflected in individuals’ lives. Samhain (pronounced Sow-en), which occurs on October 31 st, is considered the Wiccan New Year and is of particular import. The veils between the worlds, that of the living and that of the spirit, are believed to be particularly thin on this evening. Wiccans deem this the easiest time of the year to be in contact the dead. This is also a time during which people will do magical working to rid their lives of habits, behaviors, and people that are no longer a positive force in their lives. For example, someone may perform a ritual to eliminate procrastination or to help them gather their energies to leave a dead end job or a dead end relationship. In the spring, the sabbats celebrate spring and fertility in nature and in people’s lives. There is always a balance in rituals between the changes in nature and the changes in individuals’ lives (Berger 1999:29-31).

Esbats, the celebration of the moon cycles, are also of import. Drawing Down the Moon, which is possibly the best known ritual within Wicca because of a book by that title by Margot Adler (1978, 1986), involves an invocation in which the Goddess or her powers enters the High Priestess. For the duration of the ritual she becomes the Goddess incarnate (Adler 1986:18-19). This ritual is held on the full moon, which is associated with the Goddess in her phase as Mother. New moons or dark moons, which are associated with the crone, are also typically celebrated. Less often a ritual is held for the crescent or maiden moon. There are also rituals for marriages (referred to as hand-fastings); births (Wiccanings); and changing statuses of participants, such as coming of age or becoming an elder or a crone. Rituals are held for initiation and for those who becoming first, second, or third degree Wiccans or Witches. Rituals can also be done for personal reasons, including rituals for healing, for help with a particular problem or issue, for celebration of a happy event, or for thanking the deities for their help.

Wiccans conduct their magical and sacred rites within a ritual Circle that is created by “cutting” the space with an athame (ritual  knife). Because Wiccans do not normally have churches, they need to create sacred space for the ritual in what is normally mundane space. This is done in covens by the High Priestess and High Priest walking around the circle while extending athames out in front of them and chanting. Participants visualize a blue or white light radiating up in a sphere to create a safe and sacred place. The High Priestess and High Priest then call in or invoke the watchtower, that is, the powers of the four directions (east, south, west and north) and the deities associated with each of those. They normally consecrate the circle and the participants with elements that are associated with each of these directions, which are placed on an altar in the center of the circle (Adler 1986:105-106). Altars are typically decorated to reflect the ritual being celebrated. For example, at Samhain, when death is celebrated as part of the cycle of life, pictures of deceased relatives and friends may decorate the altar; on May Day (May 1 st) there would be fresh flowers and fruit on the altar, symbolizing new life and fertility.

knife). Because Wiccans do not normally have churches, they need to create sacred space for the ritual in what is normally mundane space. This is done in covens by the High Priestess and High Priest walking around the circle while extending athames out in front of them and chanting. Participants visualize a blue or white light radiating up in a sphere to create a safe and sacred place. The High Priestess and High Priest then call in or invoke the watchtower, that is, the powers of the four directions (east, south, west and north) and the deities associated with each of those. They normally consecrate the circle and the participants with elements that are associated with each of these directions, which are placed on an altar in the center of the circle (Adler 1986:105-106). Altars are typically decorated to reflect the ritual being celebrated. For example, at Samhain, when death is celebrated as part of the cycle of life, pictures of deceased relatives and friends may decorate the altar; on May Day (May 1 st) there would be fresh flowers and fruit on the altar, symbolizing new life and fertility.

Once the circle is cast, participants are said to be between the worlds in an altered state of consciousness. The rite for the  particular celebration is then conducted. The Circle also serves to contain energy that is built up during the rites until it is ready to be released in what is known as the Cone of Power. Singing, dancing, meditation, and chanting can all be used by Wiccans to raise power during a ritual. The cone of power is released for a purpose set by the Wiccan practitioners. There can be one shared purpose, such as healing a particular person or the rainforest, or each person may have his or her own particular magical purpose (Berger 1999:31). The ceremony ends with a cup of wine being raised and an athame dipped into it, symbolizing the union between the Goddess and the God. The wine is then passed around the Circle with the words “Blessed Be” and drunk by the practitioners. Cakes are blessed by the High Priestess and Priest; they are also passed around with the words “blessed be” and then eaten (Adler 1986:168). Sometimes rituals are conducted naked (skyclad) or in ritual robes, depending on the Wiccan tradition and the place the ritual is conducted. Outdoor or public rituals are normally conducted in robes or street clothes. At the end of the rites, the Circle is opened and the Watchtowers are symbolically taken down. Traditionally, people then share a meal, as eating is seen as needed to ground participants (i.e., help them leave a magical state and return to the mundane world).

particular celebration is then conducted. The Circle also serves to contain energy that is built up during the rites until it is ready to be released in what is known as the Cone of Power. Singing, dancing, meditation, and chanting can all be used by Wiccans to raise power during a ritual. The cone of power is released for a purpose set by the Wiccan practitioners. There can be one shared purpose, such as healing a particular person or the rainforest, or each person may have his or her own particular magical purpose (Berger 1999:31). The ceremony ends with a cup of wine being raised and an athame dipped into it, symbolizing the union between the Goddess and the God. The wine is then passed around the Circle with the words “Blessed Be” and drunk by the practitioners. Cakes are blessed by the High Priestess and Priest; they are also passed around with the words “blessed be” and then eaten (Adler 1986:168). Sometimes rituals are conducted naked (skyclad) or in ritual robes, depending on the Wiccan tradition and the place the ritual is conducted. Outdoor or public rituals are normally conducted in robes or street clothes. At the end of the rites, the Circle is opened and the Watchtowers are symbolically taken down. Traditionally, people then share a meal, as eating is seen as needed to ground participants (i.e., help them leave a magical state and return to the mundane world).

Solitary practitioners may join with other Wiccans or Pagans for the sabbats or esabats or perform the rituals alone. Some groups offer public rituals, often in a rented space at a liberal church or the backroom of a metaphysical bookstore. If the practitioner does a ritual alone they modify the ritual as needed. Books and some websites provide suggestions to enable solitary practitioners to do these rituals individually.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

According to the American Religious Identity survey conducted in 2008, there are 342,000 Wiccans in the United States. This is consistent with the number of teenage and emerging adult Wiccans found in The National Survey of Youth and Religion (Smith with Denton 2005:31; Smith with Snell 2009:104) Many experts believe this number is too small, based on book sales of Wiccan books and traffic on Pagan websites. Nonetheless, the religion is a minority religion. Wiccans live throughout the United States, with the largest concentration in California where ten percent of all Wiccans reside. The District of Columbia and South Dakota have the lowest percentage, with one-tenth of one percent of Wiccans living in either of those areas (Berger unpublished).

There is no single leader for all Wiccans or Witches. Most pride themselves on being leaderless. Traditionally, Wicca has been taught in covens, but a growing number of Wiccans are self-initiated, having learned about the religion primarily from books and secondarily from Websites. Some individuals are well-respected and known within the community, mostly because of their writing. Miriam Simos, who writes under her magical name, Starhawk, has been called the most famous Witch of the West (Eilberg-Schwatz 1989). Her books have had an important impact on the religion, and she was the founder and one of the leaders of her tradition, The Reclaiming Witches. Even those who have not read her books may be influenced by the ideas as they have become so much a part of the core thinking of many in the religion. There are some Pagan umbrella organizations, such as the Covenant of the Goddess (CoG), EarthSpirit Community, and Circle Sanctuary that organize festivals, have open rituals for the major sabbats, provide a webpage with information, and fight against discrimination for all Pagans. They normally charge a small fee for being a member and other fees for open rituals and festival attendance. No one is required to be a member, and there is a growing number of Wiccans who are not members of any organization. Nonetheless, these groups remain important and many of their leaders are well known within the larger Pagan community.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

There is a longstanding debate among practitioners about the group’s sacred history as presented by Gardner. Although most Wiccans now regard it as a foundation myth, a small but vocal minority believe it to be literally true. Several academics, such as Hutton and Tully have had their credentials and work brought into question by practitioners who disagree with their historical or archeological findings. Hutton (2011:227) claims that those who critique him and others who have questioned Gardner’s claim to an unbroken history between antiquity and current practices of Witchcraft have provided no new evidence to support their claims. Hutton (2011, 1999), Tully (2011) and others note that there are some elements of continuity between pre-Christian practices and current ones, particularly in terms of magical beliefs and practices, but that this does not indicate an unbroken religious tradition or practice. Hutton argues that some elements of earlier Pagan practices were incorporated into Christianity and some remained as folklore and were absorbed by Gardner creatively. Wiccan practices are informed by past practices according to him and others but that does not mean that those who were executed as witches in the early modern period were practitioners of the old religion as Margaret Murray claimed or that current practitioners are in a unbroken line of pre-Christian Europeans or Britons.

Although Wicca has gained acceptance in the past twenty years, it remains a minority religion and continues to have to fight for  religious freedom. Wiccans have won a number of court cases resulting in the pentagram being an accepted symbol on graves in military cemeteries, and, recently in California, the recognition that Wiccan prisoners must be provided with their own clergy (Dolan 2013). Nonetheless, there continues to be discrimination. For example, on Sunday, February 17, 2013 Friends of Fox anchors mocked Wicca when reporting that the University of Missouri recognized all Wiccan holidays (in reality only the Sabbats were recognized). The three anchors went on to proclaim Wiccans were either dungeons and dragons players or twice divorced middle-aged women who live in rural areas, are mid-wives and like incense. This portrait is both demeaning and inaccurate as all research indicates that while most Wiccans are women, they tend to live in urban and suburban areas and are as likely to be young as middle aged, and tend to be better educated than the general American public (Berger 2003:25-34). After a protest lead mostly by Selena Fox of Circle Sanctuary, the network apologized. Nonetheless most Wiccan believe that negative images, such as the one presented on Fox news, are common and can affect individuals’ chances of promotions and their ability to take time from work to celebrate their religious holidays. However, there does appear to be a shift from Wiccans being seen as dangerous devil worshippers to being regarded as silly but harmless. Many Wiccans have been working to have their religion recognized as a legitimate and serious practice. They are active in inter-faith work and participate in the World Parliament of Religions.

religious freedom. Wiccans have won a number of court cases resulting in the pentagram being an accepted symbol on graves in military cemeteries, and, recently in California, the recognition that Wiccan prisoners must be provided with their own clergy (Dolan 2013). Nonetheless, there continues to be discrimination. For example, on Sunday, February 17, 2013 Friends of Fox anchors mocked Wicca when reporting that the University of Missouri recognized all Wiccan holidays (in reality only the Sabbats were recognized). The three anchors went on to proclaim Wiccans were either dungeons and dragons players or twice divorced middle-aged women who live in rural areas, are mid-wives and like incense. This portrait is both demeaning and inaccurate as all research indicates that while most Wiccans are women, they tend to live in urban and suburban areas and are as likely to be young as middle aged, and tend to be better educated than the general American public (Berger 2003:25-34). After a protest lead mostly by Selena Fox of Circle Sanctuary, the network apologized. Nonetheless most Wiccan believe that negative images, such as the one presented on Fox news, are common and can affect individuals’ chances of promotions and their ability to take time from work to celebrate their religious holidays. However, there does appear to be a shift from Wiccans being seen as dangerous devil worshippers to being regarded as silly but harmless. Many Wiccans have been working to have their religion recognized as a legitimate and serious practice. They are active in inter-faith work and participate in the World Parliament of Religions.

REFERENCES

Adler, Margot. 1978, 1986. Drawing Down the Moon. Boston: Beacon Press.

Berger, Helen., A. 2005. “Witchcraft and Neopaganism.”Pp 28-54 in Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America, edited by. H elen A. Berger, 28-54. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Berger, Helen A. 1999. A Community of Witches: Contemporary Neo-Paganism and Witchcraft in the United States. Columbia, SC: The University of South Carolina Press.

Berger, Helen A. unpublished “The Pagan Census Revisited: an international survey of Pagans.

Berger, Helen. A., Evan A. Leach and Leigh S. Shaffer. 2003. Voices from the Pagan Census: Contemporary: A National Survey of Witches and Neo-Pagans in the United States. Columbia: SC: The University of South Carolina Press.

Buckland, Raymond. 1986. Buckland’s Complete Book or Witchcraft. St. Paul, Mn: Llewellyn Publications.

Clifton, Chas S. 2006. Her Hidden Children: The rise of Wicca and Paganism in America. Walnut Creek , CA: AltaMira Press.

Crowley, Vivianne. 2000. “Healing in Wicca.” Pp. 151-65 in Daughters of the Goddess: Studies of Healing, Identity, and Empowerment, edited by Wendy Griffin. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press

Cunningham, Scott. 1988. Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications.

Dolan, Maura. 2013 “ Court Revives Lawsuit Seeking Wiccan Chaplains in Women’s Prisons” Los Angeles Times , February 19. Accessed from http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2013/02/court-revives-lawsuit-over-wiccan-chaplains-in-womens-prisons.html on March 27, 2013.

Eilberg-Schwatz, Howard. 1989. “Witches of the West: Neo-Paganism and Goddess Worship as Enlightenment Religions.” Journal of Feminist Studies of Religion 5:77-95.

Griffin, Wendy. 2002. “Goddess Spirituality and Wicca.” Pp 243-81 in Her Voice, Her Faith: Women Speak on World Religions, edited by Katherine K. Young and Arvind Sharma. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Hutton, Ronald . 2011 “Revisionism and Counter-Revisionism in Pagan History” The Pomegranate12:225-56

Hutton, Ronald. 1999. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kelly, Aiden. A. 1991. Crafting the Art of Magic: Book I. St. Paul, MN: LLewellyn Publications.

Murray, Margaret A. 1921, 1971. The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Neitz, Mary-Jo. 1991. “In Goddess We Trust.” Pp.353-72 in In Gods We Trust edited by Thomas Robbins and Dick Anthony. New Brunswick NJ: Transaction Press.

Pike , Sarah . M. 2004. New Age and Neopagan Religions in America . New York: Columbia University Press.

Salomonsen, Jone. 2002. Enchanted Feminism: The Reclaiming Witches of San Francisco. London: Routledge Press.

Smith, Christian with Melinda. L. Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Christian with Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starhawk. 1979. The Spiral Dance. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers

Tully, Caroline. 2011. ” Researching the Past is a Foreign Country: Cognitive Dissonance as a Response by Practitioner Pagans to Academic Research on the History of Pagan Religions.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Religion, Orlando, FL.

Waldron, David. 2008. The Sign of the Witch: Modernity and the Pagan Revival. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Author:

Helen A. Berger

Post Date:

5 April 2013