Heaven’s Gate

]]>]]>]]>]]>

HEAVEN’S GATE

HEAVEN’S GATE TIMELINE

1927 Bonnie Lu Trousdale was born in Houston, Texas.

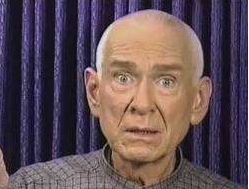

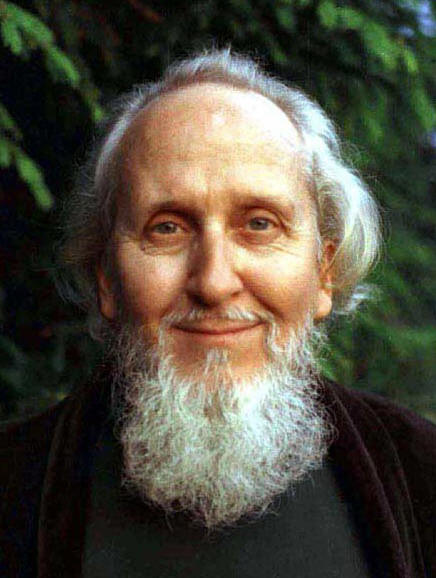

1931 Marshall Herff Applewhite was born in Spur, Texas.

1952 Applewhite enrolled at Austin College in Sherman, Texas.

1954 Applewhite graduated from Austin College with a music degree.

1966 Applewhite was appointed Assistant Professor at University of St. Thomas in Texas.

1970 Applewhite was dismissed from University of St. Thomas.

1972 Applewhite and Nettles met at Bellaire General Hospital in Houston, Texas.

1973 Applewhite and Nettles left Houston, claiming to be ‘‘The Two.”

1973 Applewhite and Nettles were imprisoned for automobile theft and fraud.

1975 “The Two” organized public meetings.

1976 (21 April) Applewhite and Nettles announced that the “Harvest is closed” and that there would be no further opportunities offered to seekers.

1976 (Summer) The Two set up a remote camp near Laramie, Wyoming.

Late 1970s Group was organized into “cells.”

1985 Nettles died of liver cancer.

1991-1992 Total Overcomers Anonymous made the “last call.”

1993 Total Overcomers Anonymous made a “final offer.”

1994 Public meetings resumed.

1996 (October) Heaven’s Gate group rented a ranch at Santa Fe, San Diego.

1996 The Hale Bopp comet appeared.

1997 39 Heaven’s Gate members committed suicide.

1997 Wayne Cooke (Jstody) committed suicide.

1998 Chuck Humphrey (Rkkody) committed suicide.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

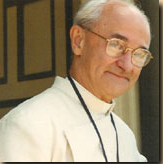

Bonnie Lu Nettles Trousdale was born in Houston, Texas and grew up in a Baptist family. She became interested in the occult, and  joined the Theosophical Society (Houston Lodge) in 1966. She also had an interest in channeling. She trained as a nurse, and first met Marshall Herff Applewhite in a hospital in Houston in 1972. The exact circumstances are disputed (Balch 1995:141).

joined the Theosophical Society (Houston Lodge) in 1966. She also had an interest in channeling. She trained as a nurse, and first met Marshall Herff Applewhite in a hospital in Houston in 1972. The exact circumstances are disputed (Balch 1995:141).

Applewhite was the son of a Presbyterian minister and, having obtained a philosophy degree, entered Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia. He abandoned his theological studies after a single semester, deciding to study music instead. He obtained a master’s degree in the subject from the University of Colorado, and embarked on an academic career, obtaining a position at the University of Alabama, and later at St. Thomas’s University in Houston. In 1970, he was dismissed from the university.

Applewhite met Nettles, and the pair established a close friendship. Their relationship was spiritual rather than sexual, and they came to believe that their acquaintance was in fulfillment of biblical prophecy. In 1973, they proclaimed themselves as the Two Witnesses mentioned in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 11:1-2), and they hired a car to take their message to various U.S. and Canadian states. The couple’s failure to return the hired car, together with credit card fraud by Nettles, led to their arrest and subsequent prison sentences (Applewhite; in Chryssides 2011:19-20).

Applewhite met Nettles, and the pair established a close friendship. Their relationship was spiritual rather than sexual, and they came to believe that their acquaintance was in fulfillment of biblical prophecy. In 1973, they proclaimed themselves as the Two Witnesses mentioned in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 11:1-2), and they hired a car to take their message to various U.S. and Canadian states. The couple’s failure to return the hired car, together with credit card fraud by Nettles, led to their arrest and subsequent prison sentences (Applewhite; in Chryssides 2011:19-20).

It was during his six-month period in prison that Applewhite appeared to have developed his teachings. They subsequently focused less on occultism, but more on UFOs and the notion of The Evolutionary Level Above Human (TELAH), which he and Nettles began to teach after being re-united. They believed that there would be a “demonstration” that would provide empirical proof of extraterrestrials who would arrive to collect their “crew.” (Applewhite 2011:21-22).

In order to assemble a “crew,” the couple advertised numerous public meetings. Their first advertisement read:

“UFO’S

Why they are here.

Who they have come for.

When they will leave.

NOT a discussion of UFO sightings or phenomena

Two individuals say they were sent from the level above human, and are about to leave the human level and literally (physically) return to that next evolutionary level in a spacecraft (UFO) within months! “The Two” will discuss how the transition from the human level to the next level is accomplished, and when this may be done.”

“This is not a religious or philosophical organization recruiting membership. However, the information has already prompted many individuals to devote their total energy to the transitional process. If you have ever entertained the idea that there may be a real, PHYSICAL level beyond the Earth’s confines, you will want to attend this meeting” (Chryssides 1999:69).

In its early days the group was called the Anonymous Sexaholics Celibate Church, but this was soon changed to Human Individual Metamorphosis (HIM), which alluded to the group’s aim of aspiring to TELAH. The Two typically gave themselves pseudonyms of matching pairs. In the early days they referred to themselves as Guinea and Pig, alluding to the idea that they were all participating in a cosmic experiment that the Next Level was undertaking. Other adopted names were Bo and Beep, and Do (pronounced “doe”) and Ti, the name by which the public later came to know them (Chryssides 2011:186).

The Two organized 130 meetings at various venues in the U.S. and Canada. At Waldport, near Eugene, Oregon in September, 1975 there were some 200 attendees, and 33 of them decided to join. Joining entailed giving up their conventional lifestyle, leaving home and going “on the road” with Do and Ti, and obtaining food and accommodation (and sometimes cash) in exchange for labor.

Later that year, Do and Te decided to withdraw from public view. They decided that the group should be divided into “cells,” dispersing to various parts of the country. Each member was assigned a partner of the opposite sex, but no physical relationship was permitted. This was one of a number of strict rules that were imposed on followers. Sex was prohibited; members had to cut their ties with the outside world; they were not permitted to watch television or read newspapers; and friendships of any kind of socializing were to be given up. Personal adornment was disallowed: women could not wear jewelry and men were required to shave off beards. It was at this point that members assumed new names ending in “-ody,” such as Jwnody (pronounced “June-ody”) or Qstody (“Quest-ody”). The suffix “-ody” was apparently a corruption of the leaders’ assumed names “Do-Ti,” and the prefix was a contraction of a personal name or some abstract quality associated with the member (DiAngelo 2007:21-22). Many of the group were unable to accept the austere lifestyle, and roughly half of them left.

In 1976, Do and Ti re-appeared and asked followers to meet them at a remote camp near Laramie, Wyoming. The group was divided into “star clusters,” smaller groups, but not dispersed this time. At this point, the group began to wear the “uniforms” with which they came to be associated: nylon anoraks and hoods. The group’s finances also improved, although the precise reasons for this are unclear. Some have suggested that two members inherited a legacy of $300,000, but others have attributed their financial improvement to the services offered by group members, principally technical writing, information technology, and automobile repairs (Balch 1995:157; DiAngelo 2007:50-51).

In the early 1980s, Nettles’ health began to deteriorate. She was diagnosed with cancer, and one of her eyes had to be surgically removed in 1983. She died two years later. Applewhite told the rest of the group that she had abandoned her body in order to arrive at the Next Level, where she would await the others.

The group made itself publicly visible once more in 1992 under the name of Total Overcomers Anonymous (or simply Total Overcomers, or TO). An advertisement by TO was placed in USA Today May 27, 1993, informing readers that the Earth was about to be “spaded under” because of its inhabitants’ lack of evolutionary progress. It made a “final offer” for people to contact the group, which secured around twenty respondents.

This final period in the group’s life was marked by renewed vigor. Concerned about continuing sexual urges, some members had resorted to medication to control their hormones. Others went further; a few, including Applewhite himself, underwent castration. This period, Applewhite taught, was humanity’s “last chance to advance beyond human,” and his message was more urgently apocalyptic than ever before (Balch 1995:163; DiAngelo 2007:57-58).

In 1996, the group rented a mansion in Rancho Santa Fé, some 30 miles outside of San Diego. The group continued with its IT  consultancy work, under the name of Higher Source. During the third week in March, 1997, the group requested that there should be no visitors. There had been reports about the arrival of Hale-Bopp comet, and Applewhite believed that there was a spacecraft behind it that contained a Representative of the Kingdom of Heaven.

consultancy work, under the name of Higher Source. During the third week in March, 1997, the group requested that there should be no visitors. There had been reports about the arrival of Hale-Bopp comet, and Applewhite believed that there was a spacecraft behind it that contained a Representative of the Kingdom of Heaven.

During this final week, Rio DiAngelo (NEody) left the group on the grounds that he had “work to do outside the class for the Next Level” (DiAngelo:104). The rest of the group began to make video-recordings of farewell messages. DiAngelo kept in contact with the group, but he failed to receive e-mail replies on Monday, March 24. The following day he received a package containing the recorded messages. On Wednesday he returned to the mansion with a friend and discovered the 39 bodies, including Applewhite. All but two of the group were laying under purple shrouds; they were wearing black trousers and Nike trainers. Those who wore spectacles had laid them out neatly at their sides; and a small baggage case lay beside each bed (DiAngelo 2007:105-09).

BELIEFS/DOCTRINES

In common with several UFO-religions, Heaven’s Gate combined belief in UFOs with biblical ideas, particularly, although not exclusively, drawing on the Book of Revelation. Nettles and Applewhite cast themselves as the Two Witnesses mentioned in the book, who had the responsibility of delivering the message to humankind. The group’s key teachings are contained in their website, “ How and When Heaven’s Gate May Be Entered.”

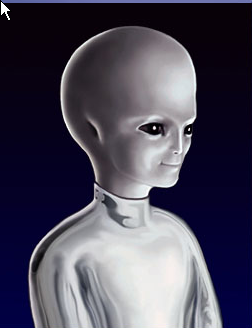

According to Heaven’s Gate’s cosmology, there existed three types of being: those living on earth, those inhabiting The Evolutionary Level Above Human, and ‘adversarial space races’ known as the Luciferians. These Luciferians are “fallen” ancestors of TELAH members. They created a civilization with advanced technology, and continue to retain some of their scientific knowledge. They can build spacecrafts and carry out genetic engineering. However, they are morally degenerate, perpetrating misinformation among the human race, abducting humans for genetic experiments, and securing their allegiance for their nefarious purposes (Applewhite 1993).

The bodies of these Next Level (TELAH) beings are physical, although markedly different from human bodies. They have eyes, ears,  and a rudimentary nose, and have a voice box, although they do not need to use it since they can communicate telepathically. These Next Level members have “tagged” selected individuals with “deposit chips” or souls, in order to prepare them for the Next Level Above Human. These humans need to make progress towards “metamorphic completion” with the aid of the Next Level “Reps’” (representatives’) teachings. Some individuals decide “not to pursue,” thereby making themselves followers of Lucifer. Others may make insufficient progress, in which case they will be “put on ice” until the Next Level Reps re-visit the earth; they will then be given a new physical body.

and a rudimentary nose, and have a voice box, although they do not need to use it since they can communicate telepathically. These Next Level members have “tagged” selected individuals with “deposit chips” or souls, in order to prepare them for the Next Level Above Human. These humans need to make progress towards “metamorphic completion” with the aid of the Next Level “Reps’” (representatives’) teachings. Some individuals decide “not to pursue,” thereby making themselves followers of Lucifer. Others may make insufficient progress, in which case they will be “put on ice” until the Next Level Reps re-visit the earth; they will then be given a new physical body.

Such terrestrial visits by the Next Level are rare. The last was two thousand years ago, when one of the Older Members of TELAH sent a representative to earth. This was his son, Jesus, also referred to as “the Captain,” who brought an “away team” with him with the task of preaching the message of how the kingdom of God might be entered. However, the Luciferians incited the human race to kill the Captain and his crew, and encouraged them to propagate false teachings. Such falsehoods include the belief that Jesus was born as an infant. The truth, Applewhite affirmed, is that Jesus’ body was ‘tagged’ by an Older Member. He matured spiritually until his baptism, which heralded his earthly mission, and his transfiguration, which completed his spiritual maturation. At his resurrection, Jesus assumed a new Next Level body and was taken up to heaven by a UFO at his ascension.

Two millennia later another “away team” entered selected human bodies. This time it was a male and female couple: the “Admiral” (also called the “Father”) was Bonnie Nettles, who worked through Marshall Applewhite (the “Captain”), purportedly proclaiming Jesus’ message and continuing his incomplete work. To underline the fact that the Two worked as one, they chose complementary names like Bo and Peep, and Ti and Do. Their mission was to collect “tagged” individuals who had been selected for the Next Level. As with Jesus’ followers, Applewhite’s community was to cut all earthly ties, and to train for the coming opportunity to enter the Next Level.

Little time was left. The Earth was coming to the end of its 6,000-year life, and Earth was suffering irreparably from pollution and dwindling resources. It had now to be “spaded over” in order to be made ready for the next era. The year 1997, arguably, fell exactly 2,000 years after Jesus’ birth, which Applewhite dated (in common with many historians) as 4 B.C.E. The arrival of the Hale Bopp comet in that year was therefore regarded as a significant portent. The group’s belief that there was a “companion” body behind it indicated the presence of the TELAH spacecraft that had arrived to enable the members to leave the world and join Ti’s crew.

The collective suicide supposedly enabled Applewhite’s followers to rise again in the new Next Level bodies. It was regarded as a triumph rather than a disaster. As he taught, “The true meaning of ‘suicide’ is to turn against the Next Level when it is being offered.” The passage in Revelation which speaks of the Two Witnesses concludes, “Then they heard a loud voice from heaven saying to them, ‘Come up here’. And they went up to heaven in a cloud, while their enemies looked on” (Revelation 11:12).

RITUALS

Apart from the final suicide in March, 1997, the Heaven’s Gate group had few, if any, practices that could be described as rituals. The only activities that could be described as “ritual,” or perhaps more accurately as pieces of symbolism, were The Two’s practice of having two members sit on either side of them during public lectures: they were to serve as “buffers” to deflect negative energy from the audience. Another ritual feature was Applewhite’s practice of lecturing beside an empty white chair: this was for his deceased partner, Ti, who was believed to be still present in spirit. There were also periods known as “tomb time” during which members were not allowed to speak to each other. Such periods could last for several days, and they caused some members to report an awareness of spaceships that had supposedly come into close range.

Despite the relative absence of formal rituals, the group had a highly structured routine. According to Balch, there was “a procedure for every conscious moment in life” (Lewis 1995:156). Members were required to give up contacts with the world and their former lives. In the last years of the group, members wore androgynous clothing resembling that of monks. Detailed rules of behavior were laid down in “The 17 Steps,” which gave instructions about how to performing assigned tasks, and lists of “Major Offenses” and “Lesser Offenses” were meticulously defined. Applewhite kept a procedure book, which was updated every day. Members were assigned “check partners” to whom they had to report daily, inquiring whether any aspect of their behavior differed from their “Older Members,” Ti and Do (DiAngelo 2007:27-29).

There were rules about food and clothing. Applewhite prohibited fish and mushrooms, and at one point in the group’s life members had a six-week period of fasting in which they only consumed “Master Cleanser,” a drink made from lemon or lime juice combined with maple syrup and cayenne pepper (DiAngelo 2007:47).

This group had its own distinctive vocabulary for describing its teachings and practices. For example, the body was described as one’s “vehicle,” one’s mind as the “operator,” the house as a “craft,” and money as “sticks.” Breakfast, lunch and dinner were called the first, second, and third “experiments” respectively, and recipes were “formulas.”

Importantly, group members did not go out UFO-spotting. Applewhite declared that he was the Next Level’s sole contactee (Balch 1995:154).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Applewhite and Nettles were the exclusive leaders of the group until the latter’s death in 1985, when Applewhite assumed full control. As mentioned above, the group was split into “cells” in the late 1970s and subsequently reunited.

During its history the group adopted various names: Anonymous Sexoholics Celibate Church, Total Overcomers Anonymous

(1991-92), Human Individual Metamorphosis (HIM), and finally Heaven’s Gate. The trading name of the group’s web design company was Higher Source.

At its peak, the group had around 200 members. The number who committed suicide on March 22-23, 1997 was 39, including Applewhite. Three other members were not present. Two subsequently took their own lives in the same ritual manner, while Rio DiAngelo remains alive and committed to spreading the group’s message. Although the Heaven’s Gate organization died with its members, its website has been mirrored, and remains online.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

The most obvious issue raised by Heaven’s Gate is how a group of followers can be brought to commit collective suicide. The group was not subject to any external threat, and there is no evidence that Applewhite’s supporters were mentally ill, vulnerable, or unduly credulous. The event gave further impetus to “brainwashing” theories, to which the public has given credence, and which are fuelled by the anti-cult movement and the media. The presence of brainwashing becomes less plausible, however, when one considers that only a very small proportion felt constrained to give up worldly ties to follow Nettles and Applewhite, and the majority of those subsequently left the group.

A further issue relates to the media coverage of Heaven’s Gate. The inevitable portrayal of such groups as “bizarre” and “wacky” “cults” gained further momentum through the media’s use of so-called “cult experts.” These commentators tend to lack formal qualifications in relevant academic fields such as religion, psychology, sociology, or even counseling, and in reality are vociferous anti-cult spokespersons. The Heaven’s Gate group was largely unknown, either in the academic community or among the public, but this did not appear to prevent these spokespersons from expressing opinions about the group. This was in contrast to academics who later gained expertise on Heaven’s Gate’s history and doctrines, but needed adequate time to study and reflect on the events.

Allied to the theme of public and media perceptions of Heaven’s Gate is the profiling of group members. Those who join NRMs are often assumed to be young and impressionable, but this was certainly untrue of Heaven’s Gate. Although the youngest member was 26, the oldest was 72, and the average age was 47. Most of the group were well-educated, indeed professional people, and did not conform to the popular or anti-cult stereotypes.

Three further issues have been identified for academic discussion: the role of the internet, the theme of violence, and millennialism. When the news of the Heaven’s Gate deaths first hit the headlines, the internet was in its infancy, and the public were largely ignorant about its nature and potential. Because much of its material could be viewed worldwide, many assumed that it was a powerful recruiting tool. Although Applewhite’s group was one of the first NRMs to use the World Wide Web, and although there is evidence that at least one seeker found the group through its web site, there is no evidence that its web presence was instrumental in attracting substantial numbers of followers, most of whom were attracted through the leaders’ more traditional public lectures. In 1997, the internet was largely confined to providing information, and arguably, since most web surfers would view information outside the group’s environment, they would be in a better position to reflect and evaluate its ideas than they would have been in more traditional settings.

Perhaps surprisingly, it is not simply the anti-cult movement that identifies Heaven’s Gate as an example of millennial violence. James R. Lewis (2011:93) writes about “The Big Five,” which encompass the Peoples Temple, Waco’s Branch Davidians, the Solar Temple, Aum Shinkrikyo, and Heaven’s Gate. Such characterization is debatable. The Heaven’s Gate group was certainly not “big,” and it was not violent, unless one simply means that it ended with multiple unnatural deaths. Members did not harm others and, although they owned a few guns, possessing such weapons is commonplace in the U.S., and they were not used.

Heaven’s Gate is sometimes characterized as a “millennial” group. This term needs to be used with some caution. The group was millennial in the sense of preaching an imminent end to affairs on earth (it would soon be “spaded over”), and the fact that its members’ demise occurred exactly two millennia after Jesus’ presumed birth date is no doubt significant. However, despite Applewhite’s preoccupation with the Book of Revelation, the group never believed in any thousand-year period during which Satan would be bound (Revelation 20:2). Applewhite taught from the Bible but, as Zeller (2010) has pointed out, uses “an extraterrestrial hermeneutic.”

REFERENCES

Applewhite, Marshall Herff. 1993. “‘UFO Cult’ Resurfaces with Final Offer.” Accessed from http://www.heavensgate.com/book/1-4.htm on 28 December 2012.

Applewhite, Marshall Herff. 1988. “’88 Update—The UFO Two and their Crew.” Pp.17-35 in Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group, edited by George D. Chryssides. Farnham: Ashgate.

Balch, Robert W. 1995. “Waiting for the Ships: Disillusionment and the Revitalization of Faith in Bo and Peep’s UFO Cult.” Pp. 137-66 in The Gods Have Landed: New Religions from Other Worlds, edited by James R. Lewis. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Chryssides, George D., ed. 2011. Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group. Farnham: Ashgate.

Chryssides, George D. 1999. Exploring New Religions. London and New York: Cassell.

DiAngelo, Rio. 2007. Beyond Human Mind: The Soul Evolution of Heaven’s Gate. Beverly Hills CA: Rio DiAngelo.

Lewis, James R., ed. 2011. Violence and New Religious Movements. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, James. 1995. The Gods Have Landed: New Religions from Other Worlds. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Zeller, Benjamin E. 2010. “ Extraterrestrial Biblical Hermeneutics and the Making of Heaven’s Gate.” Nova Religio 14:34-60.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Balch, Robert W. 2002. “Making Sense of the Heaven’s Gate Suicides.” Pp. 209-28 in Cults, Religion and Violence, edited by David G. Bromley and J. Gordon Melton. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Balch, Robert W. 1998. “The Evolution of a New Age Cult: From Total Overcomes Anonymous to Death at Heaven’s Gate: A Sociological Analysis.” Pp. 1-25 in Sects, Cults, and Spiritual Communities, edited by William W. Zellner and Marc Petrowsky. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Balch, Robert W. 1985. “When the Light Goes Out, Darkness Comes: A Study of Defection from a Totalistic Cult.” Pp 11-63 in Religious Movements: Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers, edited by Rodney Stark. New York: Paragon House Publishers.

Balch, Robert W. 1980. “Looking Behind the Scenes in a Religious Cult: Implications for the Study of Conversion.” Sociological Analysis 41:137-43.

Balch, W. Robert and David Taylor. 2003. “Heaven’s Gate: Implications for the Study of Religious Commitment.” Pp. 211-37 in Encyclopedic Sourcebook of UFO Religions, edited by James R. Lewis. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Balch, W. Robert and David Taylor. 1977. “Seekers and Saucers: The Role of the Cultic Milieu in Joining a UFO Cult.” American Behavioral Scientist 20:839-60.

Brasher, E. Brenda. 2001. “The Civic Challenge of Virtual Theology: Heaven’s Gate and Millennial Fever in Cyberspace.” Pp. 196-209 in Religion and Social Policy, edited by Paul D. Nesbitt. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Chryssides, George D. 2013 (forthcoming). “Suicide, Suicidology and Heaven’s Gate.” In Sacred Suicide, edited by James R. Lewis. Farnham: Ashgate.

Chryssides, George D. 2005. “Heaven’s Gate: End-Time Prophets in a Post-Modern Era.” Journal of Alternative Spiritualities and New Age Studies 1:98-109.

Davis, Winston. 2000. “Heaven’s Gate: A Study of Religious Obedience.” Nova Religio 3:241-67.

Goerman, L. Patricia. 2011. “Heaven’s Gate: The Dawning of a New Religious Movement.” Pp. 57-76 in Heaven’s Gate: Postmodernity and Popular Culture in a Suicide Group, edited by George Chryssides. Farnham: Ashgate.

Goerman, L. Patricia. 1998. “Heaven’s Gate: A Sociological Perspective.” M.A. thesis, Department of Sociology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Lalich, Janja. 2004. “Using the Bounded Choice Model as an Analytical Tool: A Case Study of Heaven’s Gate.” Accessed from http://www.culticstudiesreview.org/csr_member/mem_articles/lalich_janja_csr0303d.htm on April 15, 2005.

Lewis, James R. 2003. “Legitimizing Suicide: Heaven’s Gate and New Age Ideology.” Pp. 103-28 in UFO Religions, edited by Christopher Partridge. London: Routledge.

Lewis, James . 2000. “Heaven’s Gate.” Pp. 146-49 in UFO’s and Popular Culture, edited by James R. Lewis. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Marty, E. Martin. 1997. “Playing with Fire: Looking at Heaven’s Gate.” Christian Century 114: 379-80.

Miller, D. Patrick, Jr. 1997. “Life, Death, and the Hale-Bopp Comet.” Theology Today 54:147-49.

Muesse, Mark W. 1997. “Religious Studies and ‘Heaven’s Gate’: Making the Strange Familiar and the Familiar Strange.” Chronicle of Higher Education, April 25.

Nelson, Dear. 1997. “To Heaven on a UFO? Heaven’s Gate Forces Us to Ask if It’s ‘Stupid’ to Die for Our Beliefs.” Christianity Today 41:14-15.

Peters, Ted. 2004. ”UFOs, Heaven’s Gate, and the Theology of Suicide.” Pp 239-50 in Encyclopedic Sourcebook of UFO Religions, edited by James R. Lewis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Peters, Ted. 1998. “Heaven’s Gate and the Theology of Suicide.” Dialog 37:57-66.

Robinson, Gale Wendy. 1997. “Heaven’s Gate: The End?” Journal of Computer and Mediated Communication. Accessed from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol3/issue3/robinson.html on 5 April 2005.

Rodman, Rosamond. 1999. “Heaven’s Gate: Religious Otherworldliness American Style.” Pp 157-73 in Bible and the American Myth: A Symposium in the Bible and Constructions of Meaning, edited by Vincent L. Wimbush. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

Urban, Hugh. 2000. “The Devil at Heaven’s Gate: Rethinking the Study of Religion in the Age of Cyber-Space.” Nova Religio 3:268-302.

Wessinger, Catherine. 2000. How the Millennium Comes Violently: From Jonestown to Heaven’s Gate. New York: Seven Bridges Press.

Zeller, Benjamin E. 2006. “Scaling Heaven’s Gate: Individualism and Salvation in a New Religious Movement.” Nova Religio 10:75-102.

Author:

George D. Chryssides

Post Date

30 December 2012

Home | About Us |Partnerships |Profiles |Resources |WRSP Authors |Donate |Contact

Copyright © 2016 World Religions & Spirituality Project• All Rights Reserved

During the 1940s Blighton worked as a draftsman and engineer for the General Railway Signal Company and the Rochester Telephone Company. He also helped build radio stations for the United States Navy and designed optical instruments for Eastman Kodak. Blighton invented an electrical apparatus that he called the ultra theory ray machine. By irradiating patients with a sequence of colored light, he gained some success as a spiritual healer. Ultimately, this work led to his arrest and conviction for practicing medicine without a license in 1946.

During the 1940s Blighton worked as a draftsman and engineer for the General Railway Signal Company and the Rochester Telephone Company. He also helped build radio stations for the United States Navy and designed optical instruments for Eastman Kodak. Blighton invented an electrical apparatus that he called the ultra theory ray machine. By irradiating patients with a sequence of colored light, he gained some success as a spiritual healer. Ultimately, this work led to his arrest and conviction for practicing medicine without a license in 1946. taught that the material or spiritual conditions that a person sought in their lives could be gained through the visualization of esoteric symbols on the mental plane and by speaking the “word of power” (Lucas 1995:38). Blighton thought that all things in the universe were first derived from the circle, square, and triangle. The circle represented the Godhead and “the unity of all things” (1995:39). The triangle represented the process of creation. The square represented the “material plane” (1995:39). The symbol for the order became a triangle within a circle within a square.

taught that the material or spiritual conditions that a person sought in their lives could be gained through the visualization of esoteric symbols on the mental plane and by speaking the “word of power” (Lucas 1995:38). Blighton thought that all things in the universe were first derived from the circle, square, and triangle. The circle represented the Godhead and “the unity of all things” (1995:39). The triangle represented the process of creation. The square represented the “material plane” (1995:39). The symbol for the order became a triangle within a circle within a square. (Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America.

(Lofland and Richardson 1984:32-39); among them were Shiloh Youth Revival Centers, at first known as the “House of Miracles,” and later as “Shiloh” to its adherents (Di Sabatino 1994; Goldman 1995; Isaacson 1995; Richardson et al. 1979; Stewart 1992; Taslimi et al. 1991). Shiloh was one of the largest, if not the largest, in membership of the North American Christian (or any other religious) communes established during and shortly after the 1960’s hippie era. Internal estimates of those who passed through Shiloh’s 180 communal portals ranged as high as 100,000; the group claimed about 1,500 members in 37 communes and 20 churches or “fellowships” in early 1978. Bodenhausen, drawing on Shiloh’s internal records, reported 11,269 visits and 168 conversions during a five-week period in 1977. Shiloh embodied a hippie-youth vanguard of the post-war shift to Evangelical Protestantism in mid-to-late twentieth century North America. resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join.

resulted in renaming the movement “Shiloh,” by establishing a large rural commune in Dexter, Oregon, and by working with leaders of other Pentecostal denominations (the Open Bible Standard churches, and Faith Center, a small Foursquare church in Eugene). In 1971, sociologist James T. Richardson lead a team of graduate students to Shiloh’s “Berry Farm” in Cornelius, Oregon to study the group, efforts that continued in a series of contacts over the 1970s and became fully realized in Organized Miracles (1979). One unanticipated consequence was that an article published by his team in Psychology Today stirred a wave of seekers who wrote to the sociologists asking how to join. so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority.

so gifted, leader teams, and Quaker-like testimony-sharing-and-prayer meetings, to “Bible Studies” led by internally-credentialed authoritarian leaders. The original leadership consisted of four married couples: John and Jacquelyn Higgins, Lonnie and Connie Frisbee, Randy and Sue Morich, Stan and Gayle Joy (Higgins 1973; 1974a; 1974b). The Frisbees, Morichs, and Stan Joy left Shiloh by 1970; Jacquelyn Higgins left in the mid-1970s. Only Gayle Joy and John Higgins continued, and both remarried. This allowed Higgins to consolidate his authority. challenge. Secondary to this was the provision of nutritious food. Twenty-something Shiloh leaders found themselves thrust into the role of caring for large numbers of people. In response, Shiloh developed its Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book with recipes for five, 25, and 50 servings, organized dumpster diving and produce runs to recycle food, applied for USDA surplus food, and planted community gardens. Following a “prophetic” understanding that “agriculture was to be the foundation of the ministry,” Shiloh purchased an orchard, pastures, a goat dairy and livestock; leased a commercial berry farm; ran a commercial fishing boat; and developed a cannery to provide both income and food to distribute throughout its communal system.

challenge. Secondary to this was the provision of nutritious food. Twenty-something Shiloh leaders found themselves thrust into the role of caring for large numbers of people. In response, Shiloh developed its Shiloh Christian Communal Cooking Book with recipes for five, 25, and 50 servings, organized dumpster diving and produce runs to recycle food, applied for USDA surplus food, and planted community gardens. Following a “prophetic” understanding that “agriculture was to be the foundation of the ministry,” Shiloh purchased an orchard, pastures, a goat dairy and livestock; leased a commercial berry farm; ran a commercial fishing boat; and developed a cannery to provide both income and food to distribute throughout its communal system. leading Shiloh in an unacceptable direction. However, the 1978 coup d’état that followed did derail the movement with the result that hundreds of communards suddenly had to find their way in the world.

leading Shiloh in an unacceptable direction. However, the 1978 coup d’état that followed did derail the movement with the result that hundreds of communards suddenly had to find their way in the world. formerly strict membership requirements, monitoring systems, and virtually all of the other complex organizational structures that previously had defined TFI (Zerby and Kelly 2009; Shepherd and Shepherd 2010:212-13). The new approach, couched in both social science and self-realization terminology, encouraged individual TFI members to make their own life choices and set their own levels of Christian commitment to missionary activities. Communitarian living and all its attendant social and moral offshoots would no longer be expected. Individuals could now lead normal lives in secular communities, seek secular education, and hold secular jobs. Members were not mandated to make these changes, but the practical result was that, with the disappearance of WS guidance and other institutional controls, most have subsequently done so.

formerly strict membership requirements, monitoring systems, and virtually all of the other complex organizational structures that previously had defined TFI (Zerby and Kelly 2009; Shepherd and Shepherd 2010:212-13). The new approach, couched in both social science and self-realization terminology, encouraged individual TFI members to make their own life choices and set their own levels of Christian commitment to missionary activities. Communitarian living and all its attendant social and moral offshoots would no longer be expected. Individuals could now lead normal lives in secular communities, seek secular education, and hold secular jobs. Members were not mandated to make these changes, but the practical result was that, with the disappearance of WS guidance and other institutional controls, most have subsequently done so. but not officially binding and some as merely opinion and even wrong. A review of all Berg’s writings (primarily the MO Letters) has been undertaken by Maria and Peter and a small group of former Board chairs to identify those teachings deemed to be “enduring or timeless” and therefore appropriate for continued TFI purposes. The take on Berg’s overall body of writing now is that much of it was “time contextual,” i.e., applicable and appropriate only for the time and circumstances prevailing when it was written. The task, then, is to highlight those teachings that harmonize with TFI current official belief and mission statements (see below). The end result of this winnowing review will likely be stringent, with only a few hundred passages excerpted from Berg’s voluminous writings that will be retained.

but not officially binding and some as merely opinion and even wrong. A review of all Berg’s writings (primarily the MO Letters) has been undertaken by Maria and Peter and a small group of former Board chairs to identify those teachings deemed to be “enduring or timeless” and therefore appropriate for continued TFI purposes. The take on Berg’s overall body of writing now is that much of it was “time contextual,” i.e., applicable and appropriate only for the time and circumstances prevailing when it was written. The task, then, is to highlight those teachings that harmonize with TFI current official belief and mission statements (see below). The end result of this winnowing review will likely be stringent, with only a few hundred passages excerpted from Berg’s voluminous writings that will be retained. Translation work for both Activated! and Aurora products is administered by Public Affairs, as are member reports and financial contributions from the website and responses to requests/questions from website readers, both members and non-members. PA chairs in turn make monthly reports for Maria and Peter and, occasionally, travel from their various locations around the world to meet as a group with Maria and Peter for discussions about TFI’s future.

Translation work for both Activated! and Aurora products is administered by Public Affairs, as are member reports and financial contributions from the website and responses to requests/questions from website readers, both members and non-members. PA chairs in turn make monthly reports for Maria and Peter and, occasionally, travel from their various locations around the world to meet as a group with Maria and Peter for discussions about TFI’s future. humanitarian grant funding enterprise, and Activated Ministries, also headquartered in Southern California, continues as a sister international operation to carry out a range of combined religious-education and charitable projects. A number of dedicated TFI members have migrated from their previous TFI communal and organizational capacities to serve in these humanitarian vehicles as an outlet for their talents, idealistic impulses, and evangelical motivation. Ostensibly, these are autonomous organizations that have developed and are guided by the policies and procedures stipulated in their own respective business plans and operational charters and do not request or receive approval and direction from TFIS.

humanitarian grant funding enterprise, and Activated Ministries, also headquartered in Southern California, continues as a sister international operation to carry out a range of combined religious-education and charitable projects. A number of dedicated TFI members have migrated from their previous TFI communal and organizational capacities to serve in these humanitarian vehicles as an outlet for their talents, idealistic impulses, and evangelical motivation. Ostensibly, these are autonomous organizations that have developed and are guided by the policies and procedures stipulated in their own respective business plans and operational charters and do not request or receive approval and direction from TFIS.