Helena Petrovna Blavatsky

HELENA PETROVNA BLAVATSKY TIMELINE

1831 (August 11/12): Helena Petrovna von Hahn was born in Ekaterinoslav, Ukraine, Russia (July 31 according to the Julian calendar).

1849 (July 7): Helena Petrovna von Hahn married General Nikifor V. Blavatsky (b. 1809).

1849–1873: Helena Petrovna Blavatsky embarked on extensive travels around the world, including Russia, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, Canada, United States, South America, Japan, India, Ceylon, perhaps Tibet, France, Italy, United Kingdom, Germany, Serbia, Syria, Lebanon and the Balkans.

1873 (July 7): Helena Petrovna Blavatsky arrived in New York and began her public writing career.

1875 (November 17): Helena Petrovna Blavatsky co-founded the Theosophical Society in New York.

1877 (September 29): Helena Petrovna Blavatsky published her first major work, Isis Unveiled.

1879 (February 16): Helena Petrovna Blavatsky arrived in India, founded a new journal The Theosophist, and with Henry Steel Olcott relocated the headquarters of the Theosophical Society from New York City first to Bombay (now Mumbai), and in 1882 to Adyar, Madras (now Chennai), India.

1880–1884: Letters from Blavatsky’s two primary Masters, Koot Hoomi (K.H.) and Morya, were received in India by A. P. Sinnett and A. O. Hume. Sinnett’s letters were subsequently published as The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett (1923).

1884–1886: Blavatsky traveled around Europe and visited Nice, Paris, Elberfeld, London and Naples before settling in Ostend for nearly a year to work on The Secret Doctrine.

1884: Alexis and Emma Coulomb, a married couple working at the Theosophical Society’s headquarters in Adyar, published allegations that Blavatsky wrote the “Mahatma Letters” instead of their being “precipitated” communications from her teachers, the Masters of the Wisdom. Richard Hodgson of the Society for Psychical Research traveled to India to investigate.

1885: The Hodgson Report, the “Account of Personal Investigations in India, and Discussion of the Authorship of the ‘Koot Hoomi’ Letters,” was published. Hodgson concluded that Blavatsky had passed off her own writings as miraculously delivered letters from her Masters.

1887 (May–September): Helena P. Blavatsky relocated to London, founded the journal Lucifer and the Blavatsky Lodge, which in 1890 became the European headquarters of the Theosophical Society.

1888 (October–December): Helena P. Blavatsky published her second major work, The Secret Doctrine, and publicly announced the founding of the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society.

1889 (March 10): Annie Besant went to meet Helena P. Blavatsky after she read and reviewed The Secret Doctrine and joined the Theosophical Society. Besant’s home in London became the Blavatsky Lodge of the Theosophical Society, where Blavatsky lived until her death.

1891 (May 8): Helena P. Blavatsky died from the flu in relation to her chronic kidney disease at age fifty-nine.

1986: Vernon Harrison, member of the Society for Psychical Research, published “J’Accuse: An Examination of the Hodgson Report of 1885,” in which he criticized the Hodgson Report.

1997: Vernon Harrison published “J’Accuse d’autant plus: A Further Study of the Hodgson Report,” in which he concluded that the Hodgson Report was biased and based on unscientific methodology.

BIOGRAPHY

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky [Image at right] (née von Hahn) is generally regarded as one of the most influential people contributing to the emergence of modern alternative religious and esoteric traditions. She has been compared to Martin Luther and Emperor Constantine in terms of her influence on the modern religious landscape (Hammer and Rothstein 2013:1). Blavatsky’s impact includes the promotion of the idea of spirituality as opposed to the institutionalization of religion; and the notion of spiritual evolution in connection with her popularization of Asian concepts of reincarnation and karma as alternative explanations for the meaning and function of the cosmos (Hanegraaff 1998:470–82; Chajes 2019).

Blavatsky’s life was remarkable and unconventional, to say the least. Historical information about her life prior to her shift of residence to New York City on July 7, 1873 is, however, in some respects difficult to reconstruct owing to lack of sufficient source material; some of the events after 1873 are also at times unclear.

Helena von Hahn was of Russian noble descent, the daughter of Peter Alexeyevich von Hahn (1798–1873), who was captain of the horse artillery in the Russian army, and the famous novelist Helena Andreyevna (1814–1842). Her maternal grandmother was Princess Helena Pavlovna Dolgorukov (1789–1860), daughter of Prince Pavel Dolgorukov (1755–1837), a descendant of one of Russia’s oldest families. Her paternal grandfather was Lieutenant Alexis Gustavovich von Hahn whose German family branch can be traced back to the famous crusader Count Rottenstern in the Middle Ages and Countess Elizabeth Maksimovna von Pröbsen, of equally prominent descent.

Since her mother died in 1842 when Helena was only ten years old, and her father was often away on military campaigns, her early life was either spent traveling from place to place with her father or staying for long periods of time with her maternal grandparents. According to Vera Petrovna de Zhelihovsky (1835–1896), Helena’s younger sister, Helena was an unusual child who experienced all of nature as permeated with life and spirits  (Sinnett 1976:35; Cranston 1993:29). Many accounts attest that as a child she already displayed talents of a spiritualist and occult nature (Sinnett 1976:20, 32, 42–43, 49–50).

(Sinnett 1976:35; Cranston 1993:29). Many accounts attest that as a child she already displayed talents of a spiritualist and occult nature (Sinnett 1976:20, 32, 42–43, 49–50).

In October 1849 at age eighteen, a few months after her marriage to Nikifor V. Blavatsky, [Image at right] from whom she received her surname Blavatsky, she embarked on her first series of extensive travels around the globe. This was quite unusual for a woman at the time. It appears that she may have arrived in Cairo, Egypt from Constantinople in 1850–1851 where she and her friend, the American writer and artist Albert Leighton Rawson (1828–1902), met the Copt magician Paulos Metamon with whom Blavatsky wanted to form a society for the study of occult research in Cairo. During the early 1850s Blavatsky also appears to have been in Western Europe, particularly London and Paris where she frequented Spiritualist and mesmerist circles. After further travels in Canada, the United States, Mexico, South America, the West Indies, Ceylon, India, Japan, Burma, and possibly Tibet, Blavatsky was supposedly back in Paris in 1858. From there she returned to Russia in December 1858 where she seemed to have stayed until 1865 (Sinnett 1976:75–85; Cranston 1993:63–64).

Sometime in 1865 Blavatsky [Image at right] left Russia and traveled through the Balkans, Egypt, Syria, Italy, India, possibly Tibet, and Greece, until she finally arrived in Cairo for the second time in late 1871. In Cairo, Blavatsky again mingled with Spiritualists on a visit to the pyramids (Algeo 2003:15–17), and she formed a society named “Société Spirite” for the investigation of mediums and phenomena according to the theories and philosophy of Allan Kardec (1804–1869) (Algeo 2003:17–23; Godwin 1994:279–80; Caldwell 2000:32–36). This society, however, proved a disappointment to Blavatsky because of the many frauds involved in the séances, and she therefore left Cairo for Paris in the spring of 1873 where she planned to stay with one of her von Hahn cousins (Godwin 1994:280). Her stay, however, lasted only two months as, according to Blavatsky’s own narrative, she was ordered by her Masters, who communicated with her by occult means, to go to the United States “to prove the phenomena and their reality and—show the fallacy of the Spiritualistic theories of ‘Spirits’” (Godwin 1994:281–82, italics in original).

One of the exceptional modern esoteric elements associated with Blavatsky is her idea of a secret global brotherhood of Masters assisting humanity with its spiritual development. Blavatsky claimed to be in contact with this brotherhood and, among others, especially associated with Masters known as Koot Hoomi and Morya. She said she first met Morya in person in 1851 in London. Blavatsky perceived her mission to help these Masters with various tasks related to spiritual matters, including forming organizations and writing books and articles with their assistance. The Masters are often talked about as exalted human beings with seemingly physical bodies residing in physical locations, such as Tibet or Luxor, Egypt and as “spiritual teachers” and great souls or “mahatmas” (Blavatsky 1972:348; Blavatsky 1891:201). Blavatsky also emphasized, however, that the true nature of the mahatmas is beyond the physical, as she defined them as spiritual entities, higher mental entities in the realm of abstract thought only visible to the true intellectual sight (not the physical) after much training and spiritual development (Blavatsky 1950–1991, vol. 6:239). These Masters became particularly characteristic of the development of Theosophy in India where Alfred Percy Sinnett (1840–1921) and Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912), who wished to meet them and learn about their ideas, received the first so-called Mahatma Letters.

Upon instructions from her Masters, Blavatsky arrived in New York City on July 7, 1873. A year later she encountered the New York journalist and lawyer Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907) on October 14, 1874 at a series of séances held by the brothers William Eddy and Horatio Eddy as mediums at their farmhouse in Chittenden, Vermont (Olcott 2002:1–26). Blavatsky and Olcott became lifelong platonic partners and, beginning in 1876, lived together in a New York City apartment dubbed “the Lamasery,” by a reporter. The Lamasery received many visitors from near and far.

On September 8, 1875, a number of like-minded individuals, including Blavatsky and Olcott, founded the Theosophical Society for the investigation of the mysteries of the universe and the reality of spiritual phenomena. Henry Steel Olcott was elected president, Helena P. Blavatsky corresponding secretary, and William Q. Judge (1851–1896) vice-president.

The Theosophical Society later came to be guided by the universalist motto that “There is no Religion Higher than Truth.” The group adopted three basic goals:

To form a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity without distinction of race, creed, sex, caste, or color.

To encourage the study of comparative religion, philosophy, and science.

To investigate the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in humanity.

A few years after the founding of the Theosophical Society, Blavatsky and Olcott’s attention [Image at right] was directed towards India and its religious traditions. They left New York City on December 17, 1878, just a few months after Blavatsky had become an American citizen on July 8, 1878. In India, the Theosophical Society expanded with great success and established the journal The Theosophist edited by Blavatsky. In 1884, Blavatsky left for Paris, London, and Elberfeld in Germany only to return to India in 1885; she subsequently left India for good, sailing to Naples and onward to Würzburg, Germany and Ostend, Belgium, in July 1886 to work on her second major opus The Secret Doctrine.

and Olcott’s attention [Image at right] was directed towards India and its religious traditions. They left New York City on December 17, 1878, just a few months after Blavatsky had become an American citizen on July 8, 1878. In India, the Theosophical Society expanded with great success and established the journal The Theosophist edited by Blavatsky. In 1884, Blavatsky left for Paris, London, and Elberfeld in Germany only to return to India in 1885; she subsequently left India for good, sailing to Naples and onward to Würzburg, Germany and Ostend, Belgium, in July 1886 to work on her second major opus The Secret Doctrine.

Her final years from 1887 onward were spent in London. In 1887 Blavatsky initiated a journal titled Lucifer, which she edited and for which she wrote. The next year she founded the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society in order to teach the most devoted followers to unite with the One Universal Self and to develop spiritual powers. The two volumes of The Secret Doctrine were published in 1888.

In 1889, the notorious Englishwoman orator, Fabian socialist, freethinker, and feminist, Annie Besant (1847–1933), sought out Blavatsky after she had read and reviewed The  Secret Doctrine. [Image at right] Blavatsky went to live in Besant’s home, which also became the location of the Blavatsky Lodge. Since Blavatsky’s health was failing, she and Besant co-edited Lucifer. Many of her most devoted disciples and colleagues stayed with Blavatsky until her death in 1891.

Secret Doctrine. [Image at right] Blavatsky went to live in Besant’s home, which also became the location of the Blavatsky Lodge. Since Blavatsky’s health was failing, she and Besant co-edited Lucifer. Many of her most devoted disciples and colleagues stayed with Blavatsky until her death in 1891.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Blavatsky’s active writing period spans from late 1874 until her death. At this time she actively engaged with esoteric, religious, and intellectual currents such as evolutionism, the history of religions, and translations of Eastern philosophy and mythology. She was primarily engaged with the following seven themes.

First, Theosophy, which she understood to be Truth with a capital T. Theosophy is, on the one hand, [Image at right] a metaphysical, eternal, and divine wisdom that we can learn to perceive with higher spiritual faculties and, on the other hand, the historical root of all the major world religions. This Wisdom-Religion, as she called it, at the root of all religions, is also the reason why religious myths share so many apparent similarities. The notion of an ancient universal wisdom that can be traced in all the world religions is something Blavatsky wrote much about and tried to prove via the comparative method. For example, she wrote in Isis Unveiled (1877):

As cycle succeeded cycle, and one nation after another came upon the world’s stage to play its brief part in the majestic drama of human life, each new people evolved from ancestral traditions its own religion, giving it a local color, and stamping it with its individual characteristics. While each of these religions had its distinguishing traits, by which, were there no other archaic vestiges, the physical and psychological status of its creators could be estimated, all preserved a common likeness to one prototype. This parent cult was none other than the primitive “wisdom-religion” (Blavatsky 1877, vol. 2:216).

Our work, then, is a plea for the recognition of the Hermetic philosophy, the anciently universal Wisdom-Religion, as the only possible key to the Absolute in science and theology (Blavatsky 1877, vol. 1:vii).

Second, Blavatsky also wrote much about Spiritualism, mesmerism, and occult forces, trying to distinguish Theosophy and occultism from the general current of Spiritualism popular at the time. One difference she emphasized was the distinction between being passively possessed by a spirit, as in Spiritualism, which she discouraged, against the active cultivation of the will to attain higher occult powers, which she regarded as central to occultism (Rudbøg 2012:312–64). Blavatsky was one of the first to use the noun “occultism” in English, and generally used the term to designate ancient or true spiritualism; in other words, an ancient science about the spiritual forces in nature. According to Blavatsky, each individual human being “embraces the whole range of psychological, physiological, cosmical, physical, and spiritual phenomena” (Blavatsky 1891:238).

Third, Blavatsky concentrated on what she perceived to be the problems with organized religions, especially the Roman Catholic Church and its theological dogmas. She viewed most of these dogmas as distortions of truths derived from older, more original, pagan traditions. This is also, according to Blavatsky, why most religions are so irrational and cannot defend their spiritual nature in the face of modern scientific critique. In contrast, Theosophy was supposed to be the rational religion of nature restoring the true esoteric core present in all religions, including Christianity, to its original glory (Rudbøg 2012:206–51).

Fourth, Blavatsky also focused critically on what she perceived to be the dangerous materialism of modern science and its false authority.

The Satan of Materialism now laughs at all alike, and denies the visible as well as the invisible. Seeing in light, heat, electricity, and even in the phenomenon of life, only properties inherent in matter, it laughs whenever life is called VITAL PRINCIPLE, and derides the idea of its being independent of and distinct from the organism (Blavatsky 1888, vol. 1:602–03).

Against this, Blavatsky worked towards keeping the link between spirit and matter in the study of humans and nature that had previously existed in the unity of religion, philosophy, and science by emphasizing the notion of a spiritual principle and living beings behind physical forces (Rudbøg 2012:252–311).

Fifth, Blavatsky’s most heartfelt concern was establishing a universal brotherhood of humankind, and this is one of the themes that she emphasized the most in her many articles and in her practical Theosophical work in India. Blavatsky clearly emphasized the unity of truth, spirit, the cosmos, and all living beings, including humanity. She argued that as long as unnatural or human-made hierarchies exist between people in the form of sectarian religions, cultural values, and structures, humanity will not be free (Rudbøg 2012:409–43).

Sixth, she also wrote extensively to develop a grand cosmological system, which included both the spiritual and the physical dimensions; she claimed that this system was the secret “trans-Himalayan” doctrine known to her Masters residing in Tibet.

Seventh and finally, she wrote on the spiritual development of humanity and how to attain enlightenment and insight into the hidden universe (Rudbøg 2012:397–408).

These themes were all developed in her writings. She wrote primarily in English, but also published in French and Russian. The largest part of her oeuvre consists of articles written for various newspapers and Spiritualist and occult journals, especially on topics related to mesmerism, Spiritualism, Western Esoteric traditions, ancient religions, Asian religions, science and Theosophy. The journals The Theosophist, founded in 1879, and Lucifer, founded in 1887, also address these topics, and Blavatsky contributed extensively to them until her death. She also wrote occult and travel-related fiction, such as her Nightmare Tales (1892) and From the Caves and Jungles of Hindustan (1892), first published as installments in journals and later posthumously published in book form. All of her articles and stories have been gathered and republished in her Collected Writings, edited by Boris de Zirkoff, consisting of fourteen main volumes plus additional volumes (1950–1991).

Her major works (Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888)) were composed with the help of a number of her theosophically-oriented colleagues. [Image at right] Their contents are generally claimed to have been communicated to Blavatsky by the Masters of the Wisdom, “the Mahatmas,” by occult means. Both works each extend over 1,300 pages and were published in two volumes. Both were intended to prove the existence of an ancient universal secret doctrine or wisdom. Isis Unveiled was especially meant as a critique of Christian theology and modern science, while The Secret Doctrine exemplifies her most elaborate attempt to develop a grand cosmological system of spiritual and physical evolution on a massive scale. This system is composed of elements from various traditions and from various ages, including the so-called Book of Dzyan, an ancient Asian manuscript apparently known only to Blavatsky. Together these works constituted the primary exposition of Theosophical ideas and doctrines to first-generation Theosophists.

Blavatsky also wrote several other works, such as The Key to Theosophy (1889), intended to be a popular exposition in question and answer form of the main views of the Theosophists, concerning karma, reincarnation, after-death states, and the spiritual structure of each human. The same year, Blavatsky published a small volume entitled The Voice of the Silence (1889), which she said she translated from an esoteric work given to disciples undergoing spiritual initiation in Tibet. It includes elements from Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, such as the cultivation of the bodhisattva ideal of sacrificing the attainment of nirvana in order to guide others from suffering to enlightenment. Her Theosophical Glossary was published posthumously in 1892.

The following three propositions from The Secret Doctrine (1888, vol. 1:14–18) outline Blavatsky’s cosmological system. She quotes extensively from a variety of sources, including from the mysterious Book of Dzyan.

(a) An Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable PRINCIPLE on which all speculation is impossible, since it transcends the power of human conception and could only be dwarfed by any human expression or similitude. It is beyond the range and reach of thought. . . .

(b) The Eternity of the Universe in toto as a boundless plane; periodically “the playground of numberless Universes incessantly manifesting and disappearing,” called “the manifesting stars,” and the “sparks of Eternity.” “The Eternity of the Pilgrim” is like a wink of the Eye of Self-Existence (Book of Dzyan). “The appearance and disappearance of Worlds is like a regular tidal ebb of flux and reflux.”

(c) The fundamental identity of all Souls with the Universal Over-Soul, the latter being itself an aspect of the Unknown Root; and the obligatory pilgrimage for every Soul—a spark of the former—through the Cycle of Incarnation (or “Necessity”) in accordance with Cyclic and Karmic law, during the whole term…. The pivotal doctrine of the Esoteric philosophy admits no privileges or special gifts in man, save those won by his own Ego through personal effort and merit throughout a long series of metempsychoses and reincarnations.

Basically, The Secret Doctrine teaches that there is an original unity of all. Periodically the entire universe is born or comes into manifestation, lives and, after a certain period of time, dies and returns to its source. This process is seemingly never-ending. As a part of the birth of a universe with its seven distinct planes or lokas (both micro- and macrocosmically), spirit metaphorically gradually descends into matter (involution) from its high point, and after a long process of evolution in the lower planes attains higher and higher forms of experience in matter and finally returns to its source.

The evolutionary process thus takes place on several levels, including the level of solar systems, planets, and the natural kingdoms that inhabit a single planet.

Before returning to the source and becoming fully realized, the human monad must pass through long evolutions as mineral, plant, animal, human (in principle including seven distinct evolutionary “root races” and evolution on seven distinct continents on Earth, including past “continents” such as the legendary Atlantis), and thereafter in superhuman form. All off this is directed by the universal and impersonal law of karma (Chajes 2019:65-86).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Blavatsky was a devoted anti-ritualist and disliked most organized forms of religion, so no formal rituals or ceremonies were practiced in the early Theosophical Society. That said, both Blavatsky and the early Theosophists around her were interested in a number of occult practices, such as astral travel and physical materializations. Later in life, Blavatsky emphasized a number of ethical rules including brotherhood, selflessness, and vegetarianism as a way of life. These rules, which also included meditation practices and the use of colors, were however primarily for the members of the Esoteric Section.

LEADERSHIP

Perhaps by design, Blavatsky was never the official president of the Theosophical Society, a position Henry Steel Olcott held until his death in 1907, but rather its corresponding secretary. In practice, however, she may be considered its primary leader for at least three reasons. First, Blavatsky was the principal link between the Theosophical Society and the secret Mahatmas, the great spiritual masters who were the supposed real source of the Theosophical Society and its teachings. The Masters were the true authorities and, by extension, so was Blavatsky. Second, she also appears to have been a highly charismatic and strong-willed woman whom people naturally respected. Third, Blavatsky was the key original thinker and formulator of the teachings of the early Theosophical Society. The combination of these three factors have thus given her a lasting place as an authority in modern spirituality and esotericism.

In practical organizational terms Blavatsky did, however, become the leader of the Esoteric Section of the Theosophical Society (1888–1891), [Image at right] which was an independent organization for the most devoted Theosophists; she was likewise the leader of the elite “Inner Group” that emerged around the same time. According to Blavatsky’s analogy to the structure of each human being, the “Inner Group” was the manas or higher intellect of the Theosophical Society, the Esoteric Section the lower manas, and the Theosophical Society the quaternary or the personal instinctive nature (Spierenburg 1995:27). This division gives an indication of the structure of the Theosophical Society at the time and perhaps reflects the differences between Blavatsky’s strong emphasis on occultism and Olcott’s downplaying of occultism, especially after the Coulomb Affair in 1884, in favor of the cultivation of Buddhism and the exoteric organization with headquarters in India (Wessinger 1991).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

During her lifetime, Blavatsky had many admirers and followers, but she also faced many challenges and much criticism. The biggest challenge she encountered, as repeated in most accounts of her life, was the highly negative report issued by the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in 1885.

The SPR was founded in London in 1882 by Sir William Fletcher Barrett (1844–1925), an English physicist, and Edmund Dawson Rogers (1823–1910), a journalist with a background in modern Spiritualism. Given the popularity of Spiritualism, Barrett and Rogers wanted to create a forum for the impartial scientific study of such phenomena. Thus, not long after the founding of the SPR, its founders became interested in Blavatsky as they wanted to examine the rumored psychical phenomena surrounding her. In 1884, they formed a committee to collect information and evidence. The information gathered was generally inconclusive with regard to occult phenomena and, because of the good reputation of many of the Theosophists interviewed, the SPR committee decided to issue a “preliminary and provisional Report” in December of the same year (Society for Psychical Research Committee 1884). This provisional report, circulated privately, was fairly open-minded and indefinite in its conclusions.

However, around the same time in Adyar, India at the Theosophical Society’s headquarters, the so-called Coulomb case, or Coulomb Affair, was about to unfold. While Blavatsky and Olcott were away in Europe for several months between March and October 1884, Emma and Alexis Coulomb, a married couple, had turned against Blavatsky. With the help of the Rev. George Patterson, editor of the Madras Christian College Magazine, they had published several letters, purportedly written by Blavatsky. Entitled “The Collapse of Koot Hoomi,” the letters appeared in the September and October 1884 issues of the magazine. According to Mme. Coulomb, she had helped Blavatsky in the production of fraudulent occult phenomena on a large scale (Vania 1951:238–41; Gomes 2005:7–8). The SPR found this new situation very interesting and wanted to examine it before judging the veracity of the recently published letters. The SPR appointed a young Cambridge scholar and student of psychical phenomena, Richard Hodgson (1855–1905), to travel to India and investigate the circumstances firsthand.

Hodgson’s findings were put into the two hundred pages that constitute what is now known as the Hodgson Report, the “Account of Personal Investigations in India, and Discussion of the Authorship of the ‘Koot Hoomi’ Letters” (Hodgson 1885:207–380). A very large part of the report is focused on Blavatsky’s alleged forgery of Mahatma letters. In brief, the Hodgson Report concluded:

For our own part, we regard her [Helena P. Blavatsky] neither as the mouthpiece of hidden seers, nor as a mere vulgar adventuress; we think that she has achieved a title to permanent remembrance as one of the most accomplished, ingenious, and interesting impostors in history. — Statement and Conclusions of the Committee (Hodgson 1885:207).

An assessment of the Hodgson Report was undertaken by Vernon Harrison (1912–2001) in the twentieth century. Harrison was president of the Royal Photographic Society (1974–1976), co-founder of The Liszt Society, a long-standing active member of the SPR, and a professional handwriting and documents expert. For many years, Harrison had privately been occupied with the Hodgson Report and the “Blavatsky case” not only because he thought it was interesting, but also because he found it to be highly problematic. In 1986, his first critical conclusions on the Hodgson Report were published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research under the title: “J’Accuse: An Examination of the Hodgson Report of 1885.” Harrison attempted to determine if Blavatsky had produced the early Mahatma letters received by Alfred Percy Sinnett and Allan Octavian Hume in India in a disguised handwriting.

In 1997, Harrison continued his research with the publication of “J’Accuse d’autant plus: A Further Study of the Hodgson Report.” In Harrison’s extended study he analyzed each of the 1,323 slides comprising the complete set of the letters found in the British Library. He concluded that the Hodgson Report is unscientific. Harrison wrote:

I shall show that, on the contrary, the Hodgson Report is a highly partisan document forfeiting all claim to scientific impartiality. [. . .] I make no attempt in this paper to prove that Madame Blavatsky was guiltless of charges preferred against her. [. . .] My present objective is a more limited one: to demonstrate that the case against Madame Blavatsky in the Hodgson Report is NOT PROVEN—in the Scots sense (Harrision 1997:Part 1).

BE IT KNOWN THEREFORE that it is my professional OPINION derived from a study of this case extending over a period of more than fifteen years, that future historians and biographers of the said Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the compilers of reference books, encyclopaedias and dictionaries, as well as the general public, should come to realise that The Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate Phenomena Connected with The Theosophical Society, published in 1885 by the Society for Psychical Research, should be read with great caution, if not disregarded. Far from being a model of impartial investigation so often claimed for it over more than a century, it is badly flawed and untrustworthy (Harrision 1997:Affidavit).

The investigations undertaken by the SPR were a blow to Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society, and the critical judgments have been responsible for much of the negative publicity published ever since. Even though a more nuanced picture has been cast on the matter within recent years, particularly with the work of Harrison, this is only now beginning to disseminate into more mainstream knowledge.

Another associated controversy related to Blavatsky and her writings is the allegations of plagiarism that already began during her lifetime. “The Sources of Madam Blavatsky writings” (1895) by William Emmette Coleman (1843–1909) has been especially instrumental in this regard (Coleman 1895). According to Coleman’s short sixteen-page analytical tract, nearly all of Blavatsky’s works are one big plagiarizing assemblage. Coleman argued that her writings are filled with thousands of passages copied directly from other books without acknowledgment and that every idea she used and developed was taken from others and much of what she took she distorted (Coleman 1895:353–66; Rudbøg 2012:29–32). Coleman brought critical attention to Blavatsky’s sources, which remains an important issue, but more recently, cultural historian Julie Chajes has contextualized Coleman’s critique. Chajes writes, “In sum, Coleman was a plagiarism hunter” or someone at the time who made a sport of finding borrowings and allusions in the works of others (Chajes 2019:27) and that towards the end of the nineteenth century there was a trend in Britain, which found it acceptable to borrow and imitate the works of others (Chajes 2019:27). Chajes thus states that, “By the time he [Coleman] wrote his articles on Blavatsky, not everyone shared his notions of acceptable literary practice. As if to prove this, and in a rather ironic fashion, Coleman was himself accused of plagiarism in his lifetime” (Chajes 2019:28).

According to Coleman, the so-called Stanzas of Dzyan, on which The Secret Doctrine is based, was also a product of Blavatsky’s own brain rather than an ancient text existing in some obscure corner of the world (Coleman 1895:359). While the text has not been located, David and Nancy Reigle of the Eastern Tradition Research Archive continue to search for manuscripts and related Sanskrit and Tibetan texts (Reigle [2019]).

The question of Eastern sources has also led to the critique of Blavatsky as a bricoleur who has appropriated or misappropriated elements of many different religious traditions in a distorting way (Clarke 2002:89-90). While the critique in some cases is true, the picture of Blavatsky’s appropriation of Eastern ideas is more complex when read in relation to the nineteenth-century context (Rudbøg and Sand 2019).

Another controversial issue that arose in the twentieth century concerns Blavatsky’s concept of seven root races particularly the fifth race in that system of thought, which Blavatsky designated the “Aryan-race” (the term being derived from Sanskrit, Max Müller’s studies and those of others at the time), and the connection this racial doctrine might have with racism and Nazism. Popular literature has associated the two (Blavatsky and Nazism). While the doctrine of seven root races is a statement of racialism, or the belief that humankind consists of different races, religious studies scholar James A. Santucci has argued that Blavatsky’s views were primarily related to explaining the evolution of consciousness in the cosmos and the types of spiritual experiences the spiritual monad would evolve through (Santucci 2008:38). In this connection, the idea of race was secondary or used as a term of convenience to explain this evolution rather than to mobilize a racist argument. This observation ties in with the notion of a single humanity, which was important to Blavatsky (Santucci 2008:38), and the Theosophical work to mobilize this unity of humanity through “universal brotherhood,” which is a core element of Theosophy (Rudbøg 2012:409–43; Ellwood and Wessinger 1993). Lubelsky has likewise historically argued that racist discourse could be found almost everywhere in pre-1930s Europe and that “the racial doctrine of the Theosophists derived largely from the attempt to create an alternative history for their followers . . . by reflecting common scientific and cultural motifs of the time” (Lubelsky 2013:353). There is evidence that some of the concepts cultivated by Blavatsky, in combination with other intellectual discussions about races and the concept of an Aryan race at the time, filtered into the works of Guido von List (1848–1919) and Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels (1874–1954). With them some of these ideas were transfigured from their original theosophical meanings (Goodrick-Clarke 1985:33–55, 90–122), but no link directly connects these ideas in any historically convincing way with Hitler or Nazism (Goodrick-Clarke 1985:192–225; Lubelsky 2013:354).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGION

Despite these controversies, Helena P. Blavatsky remains one of the most influential religious figures of the nineteenth century; she is therefore often referred to as the mother or even great-grandmother of the New Age, modern occultism, and modern spirituality (Chajes 2019:1; Cranston 1993:521–34; Lachman 2012). She helped to introduce Asian religious and philosophical ideas to the West and continues to influence the way these ideas have been understood and spread. Blavatsky and, by extension, the Theosophical movement, supported and popularized Buddhism and Hinduism in many Western nations, as well as in India and Sri Lanka. They made a number of doctrines (such as karma and reincarnation) accessible to a wide audience. Blavatsky also facilitated the modern interest in the paranormal, occultism, subjectivity, spiritual bodies, astral travel, and the idea of “human potential.” We find the origins of beliefs in the existence of universal truths in all traditions, eclecticism, universal brotherhood, spiritual evolution, relying on one’s own experience and one’s own path to truth, and even the origins of the New Age movement in her teachings (Wessinger, deChant, and Ashcraft 2006:761; Chajes 2019:189; Hanegraaff 1998:442–82; Goodrick-Clarke 2004:18). Finally, she inspired the trend to emphasize spirituality over institutional religion, which has become a widespread phenomenon in the twenty-first century.

IMAGES:

Image #1: Helena P. Blavatsky in London, 1889.

Image #2: Helena P. Blavatsky, ca. 1860.

Image #3: Helena P. Blavatsky, ca. 1868.

Image #4: Helena P. Blavatsky in India with Subba Row and Bawaji, ca. 1884.

Image #5: Helena P. Blavatsky with James Morgan Pryse and G. R. S. Mead in London, 1890.

Image #6: Helena P. Blavatsky, 1877.

Image #7: Helena P. Blavatsky in London 1888, with her sister Vera Petrovna de Zhelihovsky on the right (seated), and shown standing left to right, Vera Vladimirovna de Zhelihovsky, Charles Johnston, and Henry Steel Olcott.

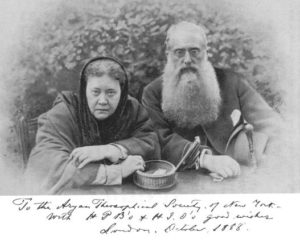

Image #8: Helena P. Blavatsky with Henry Steel Olcott in London, 1888.

REFERENCES

Algeo, John, assisted by Adele S. Algeo and the editorial committee for the letters of H. P. Blavatsky: Daniel H. Caldwell, Dara Eklund, Robert Ellwood, Joy Mills, and Nicholas Weeks, eds. 2003. The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky 1861–1879. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1972 [1889]. The Key to Theosophy. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1950–1991. Collected Writings, ed. Boris de Zirkoff. 15 vols. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1920. [1889]. The Voice of the Silence. Los Angeles: United Lodge of Theosophists.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1892. The Theosophical Glossary. London: Theosophical Publishing Society.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1888. The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy. 2 Volumes. London: Theosophical Publishing Company.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1877. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. 2 Volumes. New York: J. W. Bouton.

Caldwell, Daniel H., comp. 2000 [1991]. The Esoteric World of Madame Blavatsky: Insights into the Life of a Modern Sphinx. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Chajes, Julie. 2019. Recycled Lives: A History of Reincarnation in Blavatsky’s Theosophy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Clarke, J. J. 2003. Oriental Enlightenment the Encounter between Asian and Western Thought. London: Routledge.

Coleman, William Emmette. 1895. “The Sources of Madame Blavatsky’s Writings.” Pp. 353–66 in A Modern Priestess of Isis, Vsevolod Sergyeevich Solovyoff. Translated and edited by Walter Leaf. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Cranston, Sylvia. 1993. HPB: The Extraordinary Life and Influence of Helena Blavatsky, Founder of the Theosophical Movement. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Ellwood, Robert, and Catherine Wessinger. 1993. “The Feminism of ‘Universal Brotherhood’: Women in the Theosophical Movement.” Pp. 68–87 in Women’s Leadership in Marginal Religions: Explorations Outside the Mainstream, edited by Catherine Wessinger. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Godwin, Joscelyn. 1994. The Theosophical Enlightenment. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 1985. The Occult Roots of Nazism: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890–1935. Wellingborough: The Aquarian-Press.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. 2004. “Introduction: H. P. Blavatsky and Theosophy.” Pp. 1–20 in Helena Blavatsky, edited by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Gomes, Michael. 2005. The Coulomb Case. Occasional Papers 10. Fullerton, CA: Theosophical History.

Hammer, Olav, and Mikael Rothstein. 2013. “Introduction.” Pp. 1–12 in Handbook of the Theosophical Current, edited by Olav Hammer and Mikael Rothstein. Leiden: Brill.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1998. New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Harrison, Vernon. 1997. “H. P. Blavatsky and the SPR: An Examination of the Hodgson Report of 1885, Part 1.” Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press. Accessed from https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/hpb-spr/hpb-spr1.htm on 3 July 2019.

Harrison, Vernon. 1997. “H. P. Blavatsky and the SPR: An Examination of the Hodgson Report of 1885, Affidavit.” Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press. Accessed from https://www.theosociety.org/pasadena/hpb-spr/hpbspr-a.htm on 3 July 2019.

Hodgson, Richard. 1885. “Account of Personal Investigations in India, and Discussion of the Authorship of the ‘Koot Hoomi’ Letters,” Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 3 (May): 203–05, 207–317, appendices at 318–81.

Lachman, Gary. 2012. Madam Blavatsky: The Mother of Modern Spirituality. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

Lubelsky, Isaac. 2013. “Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy.” Pp. 335–55 in Handbook of the Theosophical Current, edited by Mikael Rothstein and Olav Hammer. Leiden: Brill.

Olcott, Henry Steel. 2002 [1895]. Old Diary Leaves: The History of the Theosophical Society. 6 Volumes. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

Reigle, David. [2019]. Eastern Tradition Research Archive. Accessed from http://www.easterntradition.org on 22 June 2019.

Rudbøg, Tim, and Erik R. Sand. 2019. Imagining the East: The Early Theosophical Society. New York: Oxford University Press (forthcoming).

Rudbøg, Tim. 2012. “H. P. Blavatsky’s Theosophy in Context: The Construction of Meaning in Modern Western Esotericism.” PhD dissertation, University of Exeter.

Santucci, James A. 2008. “The Notion of Race in Theosophy.” Nova Religio 11:37–63.

Santucci, James A. 2005. “Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna.” Pp. 177-85 in Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism, edited by Wouter Hanegraaff. Leiden: Brill.

Sinnett, Alfred Percy. 1976 [1886]. Incidents in the Life of Madame Blavatsky. New York: Arno Press.

Society for Psychical Research Committee. 1884. First Report of the Committee of the Society for Psychical Research, Appointed to Investigate the Evidence for Marvellous Phenomena Offered by Certain Members of the Theosophical Society. London: n.p.

Spierenburg, Henk J., comp. 1995. The Inner Group Teachings of H. P. Blavatsky to Her Personal Pupils (1890–91). Second revised and enlarged edition. San Diego: Point Loma Publications.

Vania, K. F. 1951. Madame H. P. Blavatsky: Her Occult Phenomena and The Society for Psychical Research. Bombay: SAT Publishing.

Wessinger, Catherine. 1991. “Democracy vs. Hierarchy: The Evolution of Authority in the Theosophical Society.” Pp. 93–106 in When Prophets Die: The Post-Charismatic Fate of New Religious Movements, edited by Timothy Miller. Albany: State University of New York.

Wessinger, Catherine, Dell deChant, and William Michael Ashcraft. 2006. “Theosophy, New Thought, and New Age Movements.” Pp. 753-68 (Volume 2) in Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America, edited by Rosemary Skinner Keller and Rosemary Radford Ruether. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Publication Date:

5 July 2019

consecrated virgins died as martyrs in order to remain faithful to their commitment to the Lord. For example, it is reported that Agnes of Rome [Image at right] refused to marry the city’s governor because of her dedication to chastity and, as a result, was killed. Cecilia of Rome, Agatha of Catania, Lucy of Syracuse, Thecla of Iconium, Apollonia of Alexandria, Restituta of Carthage, and Justa and Rufina of Seville are other women believed to have been martyred due to their commitment to chastity in the first three centuries of Christianity (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018).

consecrated virgins died as martyrs in order to remain faithful to their commitment to the Lord. For example, it is reported that Agnes of Rome [Image at right] refused to marry the city’s governor because of her dedication to chastity and, as a result, was killed. Cecilia of Rome, Agatha of Catania, Lucy of Syracuse, Thecla of Iconium, Apollonia of Alexandria, Restituta of Carthage, and Justa and Rufina of Seville are other women believed to have been martyred due to their commitment to chastity in the first three centuries of Christianity (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018).

generous self-giving to the Lord and to her neighbour” (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018). If the woman is accepted for consecration, [Image at right] the bishop and the woman will determine the details of the celebration, which will include the participation of the church community.

generous self-giving to the Lord and to her neighbour” (Braz de Aviz and Carballo 2018). If the woman is accepted for consecration, [Image at right] the bishop and the woman will determine the details of the celebration, which will include the participation of the church community. gown and veil during the consecration ceremony, and they wear a wedding ring as a symbol of their commitment to Christ. [Image at right]

gown and veil during the consecration ceremony, and they wear a wedding ring as a symbol of their commitment to Christ. [Image at right] may choose to voluntarily join in an association. [Image at right] The United States Association of Consecrated Virgins (USACV) states it “is formed in accord with Canon 604.2. ‘Virgins can be associated together to fulfill their pledge more faithfully and to assist each other to serve the Church in a way that befits their state’” (United States Association of Consecrated Virgins 2019).

may choose to voluntarily join in an association. [Image at right] The United States Association of Consecrated Virgins (USACV) states it “is formed in accord with Canon 604.2. ‘Virgins can be associated together to fulfill their pledge more faithfully and to assist each other to serve the Church in a way that befits their state’” (United States Association of Consecrated Virgins 2019).

leaders in antiquity, and from Shinto (Reichl 1993b). The Ijun logo, five dark circles around a lighter central circle, is said to represent the major world religious traditions coming together in Ijun. [Image at right] This recalls the logo of Seichō no Ie. Both Ijun and Seichō no Ie encourage followers to attend other churches as well. At the same time, many Ijun concepts are from Ryukyuan culture, including the sibling creator deities, Amamikyu and Shinerikyu (See Doctrines/Beliefs), and the primary deity Kinmanmon. Although Ijun no longer exists in a formal legal sense, some adherents continue to practice informally. It is unclear to what extent the company Culture Ijun continues religious activity.

leaders in antiquity, and from Shinto (Reichl 1993b). The Ijun logo, five dark circles around a lighter central circle, is said to represent the major world religious traditions coming together in Ijun. [Image at right] This recalls the logo of Seichō no Ie. Both Ijun and Seichō no Ie encourage followers to attend other churches as well. At the same time, many Ijun concepts are from Ryukyuan culture, including the sibling creator deities, Amamikyu and Shinerikyu (See Doctrines/Beliefs), and the primary deity Kinmanmon. Although Ijun no longer exists in a formal legal sense, some adherents continue to practice informally. It is unclear to what extent the company Culture Ijun continues religious activity.

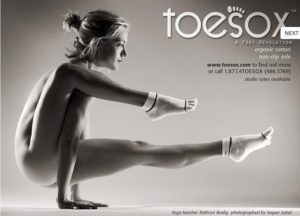

Body As Temple” ad campaign began in 2008, which features Budig completely nude other than the ToeSox® on her feet in a variety of advanced postural poses. [Image at right] Tastefully photographed by Jasper Johal, the images rocketed her to instant stardom. In 2010, the ad campaign experienced heavy criticism from prominent teachers, feminists, and other activists in yoga who argued that images like those featured in “The Body As Temple” campaign contributed to the sexualization and exploitation of women in the yoga industry (Miller 2016). Ironically, the controversy surrounding the ToeSox® advertisements helped Budig reach wider audiences, a process facilitated by new social media forms like Facebook (which was available for public use starting in 2006) and Instagram (founded in 2010). Budig quickly gathered large numbers of followers on these platforms, becoming one of the best-known yoga teachers in the country.

Body As Temple” ad campaign began in 2008, which features Budig completely nude other than the ToeSox® on her feet in a variety of advanced postural poses. [Image at right] Tastefully photographed by Jasper Johal, the images rocketed her to instant stardom. In 2010, the ad campaign experienced heavy criticism from prominent teachers, feminists, and other activists in yoga who argued that images like those featured in “The Body As Temple” campaign contributed to the sexualization and exploitation of women in the yoga industry (Miller 2016). Ironically, the controversy surrounding the ToeSox® advertisements helped Budig reach wider audiences, a process facilitated by new social media forms like Facebook (which was available for public use starting in 2006) and Instagram (founded in 2010). Budig quickly gathered large numbers of followers on these platforms, becoming one of the best-known yoga teachers in the country.

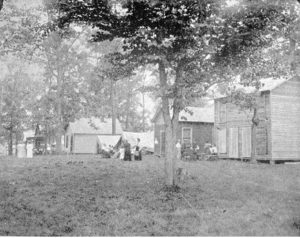

Spiritualists, as well as the religion of Spiritualism as a whole, is nothing short of prodigious. From around 1909 until her death in 1961, Reverend Mable Riffle [Image at right] steered Camp Chesterfield with a strong hand as Secretary of the association. Rev. Riffle’s resounding mantra during her long years of service to the IAOS and Spiritualism was a simple question: Is it good for Camp? (Richey 2009). This was her response to any proposal, idea or change that the Board of Trustees, mediums, residents, or members would endeavor to implement. If the answer were “no,” then it would go no further. Her lifelong dedication to the “good” of Camp Chesterfield is evident in the huge growth that occurred under her watchful guidance.

Spiritualists, as well as the religion of Spiritualism as a whole, is nothing short of prodigious. From around 1909 until her death in 1961, Reverend Mable Riffle [Image at right] steered Camp Chesterfield with a strong hand as Secretary of the association. Rev. Riffle’s resounding mantra during her long years of service to the IAOS and Spiritualism was a simple question: Is it good for Camp? (Richey 2009). This was her response to any proposal, idea or change that the Board of Trustees, mediums, residents, or members would endeavor to implement. If the answer were “no,” then it would go no further. Her lifelong dedication to the “good” of Camp Chesterfield is evident in the huge growth that occurred under her watchful guidance.

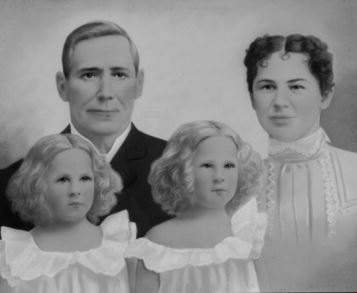

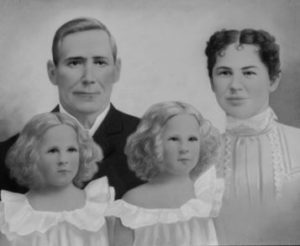

Richmond, Indiana in the early 1920’s. He sat for the portrait of his wife, Lizzie, and she appeared. He asked why the twins, Mary and Christina, could not come, and they then appeared. [Image at right] Dr. Daughtery was not in spirit, but was sitting for the portrait.

Richmond, Indiana in the early 1920’s. He sat for the portrait of his wife, Lizzie, and she appeared. He asked why the twins, Mary and Christina, could not come, and they then appeared. [Image at right] Dr. Daughtery was not in spirit, but was sitting for the portrait. display represent a significant and tangible glimpse into the history of Spiritualism and precipitated spirit art, [Image at right] of which Camp Chesterfield and the Indiana Association of Spiritualists have the singular duty as the primary custodians to preserve and protect these works as it is an unparalleled collection and is the world’s largest repository of precipitated spirit art.

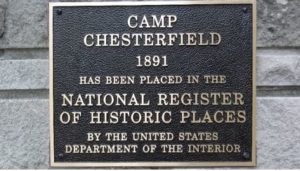

display represent a significant and tangible glimpse into the history of Spiritualism and precipitated spirit art, [Image at right] of which Camp Chesterfield and the Indiana Association of Spiritualists have the singular duty as the primary custodians to preserve and protect these works as it is an unparalleled collection and is the world’s largest repository of precipitated spirit art. porch chatting and exchanging messages they received from loved ones. Camp Chesterfield is historically significant for Indiana, being listed on the National Park Service’s “National Register of Historic Places” as a historic district. [Image at right] Camp Chesterfield has served as a spiritual center of light for generations of Hoosiers, contributing greatly to the religious fabric that makes up Indiana’s unique religious history.

porch chatting and exchanging messages they received from loved ones. Camp Chesterfield is historically significant for Indiana, being listed on the National Park Service’s “National Register of Historic Places” as a historic district. [Image at right] Camp Chesterfield has served as a spiritual center of light for generations of Hoosiers, contributing greatly to the religious fabric that makes up Indiana’s unique religious history. want or need to attend in the morning. This is indeed a throwback to the time when such an arrangement was needed and necessary in order to accommodate its worshipers.

want or need to attend in the morning. This is indeed a throwback to the time when such an arrangement was needed and necessary in order to accommodate its worshipers. more mainstream Christian tradition, they brought with them vestiges and customs that were a part of their religious upbringings and belief systems. [Image at right]

more mainstream Christian tradition, they brought with them vestiges and customs that were a part of their religious upbringings and belief systems. [Image at right]

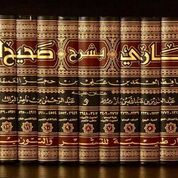

(815-875), which have often been published with extensive commentaries [image at right]. While the Quran is the same for all Muslims, these hadith collections are distinctively Sunni.

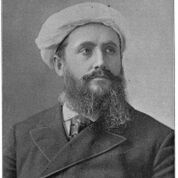

(815-875), which have often been published with extensive commentaries [image at right]. While the Quran is the same for all Muslims, these hadith collections are distinctively Sunni. was not really established in America until the twentieth century. The first known mosque in America, built in New York in 1893 by Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb (1846-1914), [image at right] soon closed (Abd-Allah 2006:17-18). It was after the Second World War that new patterns of global migration first brought significant numbers of Sunni Muslims to North America and Western Europe.

was not really established in America until the twentieth century. The first known mosque in America, built in New York in 1893 by Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb (1846-1914), [image at right] soon closed (Abd-Allah 2006:17-18). It was after the Second World War that new patterns of global migration first brought significant numbers of Sunni Muslims to North America and Western Europe. vacations in Europe (Sedgwick 2010), while the leading South Asian modernist, the Indian Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898) [image at right], stressed his loyalty to the British Empire, joined the (British) Viceroy’s Council, and was rewarded with a knighthood.

vacations in Europe (Sedgwick 2010), while the leading South Asian modernist, the Indian Syed Ahmad Khan (1817-1898) [image at right], stressed his loyalty to the British Empire, joined the (British) Viceroy’s Council, and was rewarded with a knighthood. such as Abul A’la Maududi (1903-1979) in India and then Pakistan, and by Hassan al-Banna (1906-1949) [image at right] in Egypt (Kraemer 2010). These Islamist ideologies generally criticized both capitalism and socialism and promoted Islam as a “third way” that was not only superior to non-Islamic alternatives but also more culturally authentic.

such as Abul A’la Maududi (1903-1979) in India and then Pakistan, and by Hassan al-Banna (1906-1949) [image at right] in Egypt (Kraemer 2010). These Islamist ideologies generally criticized both capitalism and socialism and promoted Islam as a “third way” that was not only superior to non-Islamic alternatives but also more culturally authentic. especially images of humans and animals, which are thought to be forbidden by the sunna. For many centuries, Sunni visual art was primarily non-representational; art forms such as tile-work with geometric patterns thus became highly developed [image at right]. Photographs, film and video are now almost universally accepted, but residences are still often decorated with finely-calligraphed Quranic texts or painted images of uninhabited landscapes, and representational images are never found in mosques (Sedgwick 2006: 30-131, 134). Representation of the Prophet is understood as entirely forbidden. Many Shi’i Muslims, in contrast, do not consider images, including images of the Prophet, to be forbidden.

especially images of humans and animals, which are thought to be forbidden by the sunna. For many centuries, Sunni visual art was primarily non-representational; art forms such as tile-work with geometric patterns thus became highly developed [image at right]. Photographs, film and video are now almost universally accepted, but residences are still often decorated with finely-calligraphed Quranic texts or painted images of uninhabited landscapes, and representational images are never found in mosques (Sedgwick 2006: 30-131, 134). Representation of the Prophet is understood as entirely forbidden. Many Shi’i Muslims, in contrast, do not consider images, including images of the Prophet, to be forbidden. madrasas found in the major cities. Some of these major madrasas are famous across the Sunni world, as some major universities are famous across the West. Among them are the Qarawiyyin in Morocco [image at right] and the Azhar in Cairo, both of which are based in equally famous mosques. These madrasas and their students and staffs of researchers and teachers were independent, self-governing institutions financed by waqf, normally land and property that had been given by the rich and powerful in earlier ages for charitable purposes. As well as madrasas, waqf also supported public services from non-teaching mosques to hospitals, baths and soup kitchens. The administrators of waqf were normally themselves ulama, giving the ulama economic power in addition to religious and intellectual prestige, and buttressing their independence.

madrasas found in the major cities. Some of these major madrasas are famous across the Sunni world, as some major universities are famous across the West. Among them are the Qarawiyyin in Morocco [image at right] and the Azhar in Cairo, both of which are based in equally famous mosques. These madrasas and their students and staffs of researchers and teachers were independent, self-governing institutions financed by waqf, normally land and property that had been given by the rich and powerful in earlier ages for charitable purposes. As well as madrasas, waqf also supported public services from non-teaching mosques to hospitals, baths and soup kitchens. The administrators of waqf were normally themselves ulama, giving the ulama economic power in addition to religious and intellectual prestige, and buttressing their independence.

and is thought by some to have moved from its Islamist roots to being the vehicle of its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 1954) [image at right], and (less famously) PAS, the Malaysian Islamic Party, which has won and lost numerous state elections, though it has never done well in federal elections.

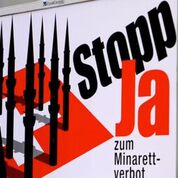

and is thought by some to have moved from its Islamist roots to being the vehicle of its leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 1954) [image at right], and (less famously) PAS, the Malaysian Islamic Party, which has won and lost numerous state elections, though it has never done well in federal elections. uncomfortable for Western Muslims, as does an increasingly hostile political environment, represented in the United States by President Trump’s attempted “Muslim Ban” and in Europe by anti-Islamic rhetoric from populist nationalist parties [image at right]. So far, European legislation such as the ban in many countries on the niqab (the face-veil) has directly impacted relatively few Muslims, as it is only a minority (mostly Salafis) that believes the niqab to be required. Many Muslims who are not directly affected by such legislation, however, fear further measures that may adversely affect them.

uncomfortable for Western Muslims, as does an increasingly hostile political environment, represented in the United States by President Trump’s attempted “Muslim Ban” and in Europe by anti-Islamic rhetoric from populist nationalist parties [image at right]. So far, European legislation such as the ban in many countries on the niqab (the face-veil) has directly impacted relatively few Muslims, as it is only a minority (mostly Salafis) that believes the niqab to be required. Many Muslims who are not directly affected by such legislation, however, fear further measures that may adversely affect them.