ISLAMIC STATE TIMELINE

1999: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi first met Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan and went on to set up a competing jihadi training camp.

2001: Zarqawi’s jihadi group, Jama‘at al-Tawhid wa’l-Jihad (JTL), began operations in Jordan.

2003 (March): The U.S. invasion of Iraq took place; Zarqawi returned to Iraq with JTL to confront the U.S.

2004 (September): Zarqawi declared loyalty to Osama bin Laden and renamed his group al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

2006 (June): A U.S. air strike killed Zarqawi; Abu Ayyub al-Masri emerged as the new leader of AQI.

2006 (October): al-Masri renamed AQI as the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) and identified Abu Omar al-Baghdadi as the leader.

2010 (April): Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi emerged as leader of ISI after al-Masri and Abu Omar al-Baghdadi were killed in a U.S.-Iraqi military operation.

2013 (April): ISI announced that it was absorbing Jabhat al-Nusra, a Syrian-based jihadi group affiliated with al-Qaeda; ISI was renamed as the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham/Syria (ISIS).

2013 (December): ISIS took control of Ramadi and Fallujah.

2014 (February): al-Qaeda renounced ties to ISIS.

2014 (June): Mosul fell to ISIS; al-Baghdadi renamed ISIS as the Islamic State (IS) and declared himself caliph.

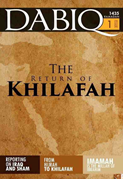

2014 (July): The first issue of the IS online magazine, Dabiq, appeared.

2014 (August): The U.S. began its air campaign against IS targets in Iraq; IS began to carry out several highly publicized beheadings of Western captives, among them James Foley.

2014 (September): An international coalition to defeat IS took shape under U.S. direction.

2014 (November): An Islamist militant group operating in Egypt’s Sinai, Ansar Beit al-Maqdis, declared its allegiance to IS and renamed itself Wilayat Sinai or province of Sinai.

2015 (January): Islamist militants in Libya, identifying themselves as a province of IS, Wilayat Tarablus, kidnapped twenty-one Egyptian workers who were beheaded the next month for shock value.

2015 (May): IS captured Ramadi, Iraq, and Palmyra, Syria, even as it lost other territory.

2015 (November): IS claimed responsibility for attacks against Shia in Beirut, Lebanon; one week later IS members carry out multiple assaults in and around Paris, killing 130 and wounding hundreds.

2016 (March): IS members carried out attacks at the Brussels airport and metro station. Boko Haram, the Nigerian militant group, declared its allegiance to IS.

2016 (October): IS-affiliated Sinai Province downed Russian airliner over the Sinai Peninsula, killing over 200.

2017 (October): IS’s battle for Raqqa, Syria ended in defeat.

2017 (November): IS-linked militants attacked a mosque in Bir al-Abed, Egypt, killing hundreds.

2018 (May): An IS-linked family carried out suicide bombings in Surabaya, Indonesia.

2019 (March): The final defeat of IS in the Syrian town of Baghouz took place, marking the end of the caliphate.

2019 (April): IS-linked militants carried out coordinated attacks against hotels and Catholic churches in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

2019 (October): IS leader Abu Bakr Baghdadi killed during a raid by U.S. forces.

2022 (February): Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Quraishi, inheritor of the mantle of leadership after Baghdadi, was killed during a raid by U.S. forces.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The group currently known as the Islamic State (IS) [Image at right] has changed its name several times throughout its brief history. It has also undergone dramatic transformations in its social structure: starting as a localized jihadist militia, expanding into a cross-border Sunni insurgency, evolving into a Salafi-Jihadi quasi-state-cum-caliphate, and operating currently as a fragmented global jihadist organization. In the narrative that follows, the various identities are acknowledged for the appropriate time periods as are its structural transformations. It is important to note that IS continues to be referred to in multiple, and sometimes confusing, ways in Western sources: the most common alternative usages are Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (=Syria) or ISIS and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant or ISIL; the distinction here relates to the best rendering of the Arabic transliteration “al-Sham,” the region once known as Greater Syria, with some preferring the English “the Levant.” In the Arab world, al-Dawla al-Islamiyya fi’l-Iraq and al-Sham or Daesh has become popular, in part because the acronym allows for satiric and disrespectful plays on other Arabic words. Some have questioned the wisdom of adopting references like ISIS, ISIL or even Islamic State (IS) since, in the context of an ongoing propaganda war, they may inadvertently lend support to the movement’s claim of holding legitimate Islamic political authority.

At the height of its power, IS represented a new generation of global Islamist formation that combined Salafi-Jihadi ideology, sophisticated public relations, guerilla warfare, and state-building aspirations. It emerged as a dominant force when the chaos of two failing Middle Eastern states, Iraq and Syria, allowed an otherwise isolated jihadist militia to reinvent itself and play upon political, economic, and social disillusionment in the region and beyond. The short-term success of IS has raised important questions about the political cohesion of nation-states in the Middle East, Western foreign policy in the region and the broader Muslim world, the volatility of global Muslim identity, and the ability of jihadist groups to capitalize on the failures, real and perceived, of modernity.

IS has both an ideological genealogy and organizational history, and their interconnection is important for understanding the way the group has played into the modern Muslim imagination about religion-state relations. The ideological roots of IS trace back to Islamism (sometimes referred to as political Islam) and the Islamist claim that Islam, not secular nation-states, holds the answers to development and political identity in the Muslim world. For its original advocates, Hasan al-Banna of Egypt and Mawlana Mawdudi of India (and later Pakistan), Islamism provided an authentic counter narrative to the Western modernity that had, in the first half of the twentieth century, attracted so many Muslims as the most viable means of establishing a place within the emerging international system of nation-states. The seeds of Islamism were planted, not coincidentally, at the very time that Muslim-majority countries were facing the challenge of colonialism and deciding upon their own political futures. And the historic institution of the caliphate proved an essential topic for Muslim political thinking and identity politics

Founded in 632 C.E. upon the death of the Prophet Muhammad, the caliphate was officially abolished in 1924 after the leader of newly formed nation-state of Turkey, the remaining remnant of the Ottoman Empire, cast off its Islamic cultural baggage and created a Euro-centric (i.e., secular) future. In a very real sense, the end of the caliphate signaled the rise of political modernity in the Middle East, and Islamism emerged as an Islam-centered response, an attempt to modernize along a path that maintained a distinctively different identity for Muslims, even when this path mimicked many of the same structural and institutional configurations as Western nation-states. Most Muslim-majority nation-states came to reject Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s explicit embrace of secularization (in the form of French laïcité), but they did adopt political systems with secular underpinnings, including legal structures.

Rather than disappear from the historical scene, Islamist movements, like the Society of Muslim Brothers in Egypt, founded by Hasan al-Banna in 1928, became a voice of political opposition, one that was sometimes suppressed quite brutally. The authoritarian nature of many states in the Middle East made it difficult for Islamists to advocate openly for their version of an Islamic state, and the occasional outburst of political violence by Islamists gave authoritarian regimes reason to crack down even harder on these movements. Over time, Islamists divided over the most effective means to bring about their ideal Islamist order within the framework of autocratic nation-states that allowed little opportunity to engage in open political debate: some, following the lead of Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb, in his radical primer Milestones, [Image at right] turned to militancy as the only way to eliminate what for them had become apostate rulers, if not godless societies; most, however, advocated a moderate path of preaching, teaching and charitable outreach.

Islamists gave authoritarian regimes reason to crack down even harder on these movements. Over time, Islamists divided over the most effective means to bring about their ideal Islamist order within the framework of autocratic nation-states that allowed little opportunity to engage in open political debate: some, following the lead of Muslim Brotherhood ideologue Sayyid Qutb, in his radical primer Milestones, [Image at right] turned to militancy as the only way to eliminate what for them had become apostate rulers, if not godless societies; most, however, advocated a moderate path of preaching, teaching and charitable outreach.

All of this might seem far removed from IS, but the militant trend among Islamists within Muslim-majority nations took a dramatic turn in the aftermath of the Afghan-Soviet war (1979-1989), giving rise to the global jihadism of al-Qaeda, which was the precursor to IS. Activist Muslims, some Islamists, some not, flocked to the battlefields of Afghanistan, intent on waging jihad against the Soviet invaders; and they were supported in their efforts, secretly at the time, by the intelligence services of the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. After the Soviets were defeated, some of the so-called “Arab Afghans” stayed on in Afghanistan and a few gravitated to Osama bin Laden’s call to continue the jihad but take it global. al-Qaeda was comprised, in part, of militant Islamists from places like Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Tunisia, and Jordan, who had pushed the Islamist agenda in their home countries and failed to make headway against governments unfriendly to their political goals (Wright 2006:114-64). For example, al-Qaeda’s second in command, Ayman al-Zawahiri, had been jailed in Egypt for his involvement with the Jihad Organization, which had assassinated President Anwar Sadat in 1981. But what distinguished the global jihadism of al-Qaeda from the militant Islamism of, say, Hamas in Palestine or Jihad in Egypt, was its identification of the West, in particular the United States, as the most important threat and focus of jihad. Whereas militant Islamists directed their attention toward the “near enemy” of secularized Arab-Muslim elites (viewed as apostates), global jihadist saw the “far enemy” of the West as the ultimate challenge to the victory of Islam. Moreover, whereas moderate Islamists had, over time, made peace with the modern state system, even agreeing to form political parties and participate in elections, global jihadist came to see such engagement as an embrace of Western ways and a betrayal of the Islamic cause.

A primary factor, then, in the emergence of global jihadism was the failure of Islamism to be accommodated within the “instrumental politics” of nation-states in the Middle East (Devji 2005:2). Islamism went global because it found the path to power blocked by authoritarian states unfriendly to its political goals, and global jihadism could only take root beyond the effective sovereignty of any state. Thus, it was the chaos of war-ravaged Afghanistan that allowed bin Laden to organize al-Qaeda, establish jihadist training camps, and go on to wage war against what he called “the global Crusaders.” And it was the chaos of Iraq that served as the backdrop to the organizational history of IS.

The person who capitalized on and exacerbated this chaos was Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, [Image at right] a Jordanian jihadist with a history of brutal terrorist acts. After serving a prison sentence in Jordan, he traveled to Afghanistan in 1999, where he met Osama bin Laden and, with bin Laden’s assistance, started a competing jihadi training camp nearby. While sharing many of al-Qaeda’s views and goals, Zarqawi remained independent. He founded Jama‘at al-Tawhid wa’l-Jihad (JTL), which established a record of terrorism in both the Middle East and Europe, all of which drew the attention of U.S. intelligence agencies. He shifted his base of operations to Iraq after the U.S. invaded in 2003 to confront Western forces. By 2004, Zarqawi had pledged allegiance to bin Laden, and JTL was rebranded as al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI). Between 2004 and his targeted killing by a U.S. airstrike in 2006, Zarqawi waged a sectarian war, presumably with the approval of bin Laden, against Iraqi Shi‘a in an effort to divide the country and drive the Sunni population into the camp of AQI. So bloody were Zarqawi’s methods that he drew a rebuke from Zawahiri about the need to avoid alienating Muslims from the jihadist cause (Cockburn 2015:52; Weiss and Hassan 2015:20-39).

After Zarqawi’s death, command of AQI fell to Abu Ayyub al-Masri, who renamed the organization Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) a few months later and identified Abu Omar al-Baghdadi as the leader. From 2007 onward, ISI encountered increasing pressure from the Sunni Awakening, a joint effort of Sunni tribes and U.S. military to eliminate the jihadist threat. By 2010, ISI had witnessed a severe decline in its capacity to engage the enemy, whether Shi‘a or coalition forces, and the killing of both Masri and al-Baghdadi seemed to confirm this situation. The new leader of ISI, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, inherited a much-weakened organization, but the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq in 2011 provided an opening to reinvigorate terrorist actions. ISI received added impetus from the civil war that broke out in neighboring Syria by the end of 2011 because of the Arab spring uprisings. Syria’s long-oppressed Sunni majority rose up against President Bashar al-Assad, who drew his support from the Alawite minority (a Shi‘i subsect). Much of the initial Sunni opposition in Syria reflected secular leanings, but it was quickly outpaced and out-financed by Islamist and jihadist groups. Thus, what began as a broad-based protest against the regime to demand political and economic rights for Sunnis turned into a religious sectarian battle that drew in regional powers, such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Iran—all intent on promoting their own political agendas.

Meanwhile, in Iraq, the newly elected president, Nouri Kamal al-Maliki, implemented a series of policies that strengthened the Shi‘i majority, often at the expense of the Sunni minority that had ruled the country under Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime. Iraq’s Sunnis had already experienced a dramatic decline in political and economic power because of the de-Baathification policies introduced under the U.S. occupation, including the disbanding of the Iraqi army. Their sense of disenfranchisement grew when the Shi‘i-dominated government in Baghdad strengthened its ties to Iran, drew on the support of Shi‘i militias, and targeted Sunnis/Baathists accused of attempting to regain power. The protest of Sunnis in Syria became a rallying cry for Sunnis in Iraq, and ISI was there to capitalize on the situation. A seeming perfect storm of beleaguered Sunnis and self-serving Shi‘i rulers in Syria and Iraq provided ISI with the opportunity to fan the flames of sectarianism and insinuate itself into the volatile mix of identity politics.

The instrument of ISI’s intervention in Syria was an AQI-affiliated group, Jabhat al-Nusra (JN), which established itself among the array of opposition fighters by early 2013. Claiming that it had sent JN to gain a foothold for ISI in Syria, Baghdadi declared the two groups had merged to form the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham/Syria (ISIS). The leader of JN, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, rejected the merger, and a falling out between ISIS and al-Qaeda ensued, with Zawahiri attempting to restrict Baghdadi’s field of operations to Iraq. Infighting among jihadist groups was common in Syria, but the rift between ISIS and al-Qaeda threatened to split the core group that had come to define global jihadism. By early 2014, al-Qaeda and ISIS had renounced one another, and in June of that year ISIS made a bold military push in Iraq that included the taking of Mosul, the country’s second largest city, and a highly dramatized “smashing the borders” campaign that removed the barrier between Syria and Iraq.

With the border under its control, ISIS claimed that the era of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret treaty dividing the Middle East into spheres of colonial influence, negotiated in 1916 between France and Britain, had come to an end, and so too had the Western ideology that separated Muslim people in the region: nationalism. ISIS used this occasion to declare the establishment of the Islamic State (IS) and a return of the caliphate, with Baghdadi named the “commander of the faithful,” [Image at right] the person to whom all Muslims around the world owe allegiance and obedience. In a symbolic demonstration of his new title, Baghdadi, dressed in traditional garb, delivered the Friday sermon, on July 4, in the Great Mosque of Mosul and led the congregation in prayer. His sermon made clear that the world had, with the (re-)creation of the caliphate, split into two opposing forces: “the camp of Islam and faith, and the camp of kufr (disbelief) and hypocrisy.” Muslims around the world were now religiously obligated to emigrate to the state where Islam and faith ruled (Dabiq 1:10). It is important to note that the caliphate had been part of bin Laden’s theoretical range of vision. In an interview one month after 9/11, he stated:

So I say that, in general, our concern is that our umma unites either under the Words of the Book of God or His Prophet, and that this nation should establish the righteous caliphate of our umma…that the righteous caliph will return with the permission of God (Bin Laden 2005:121).

But bin Laden [Image at right] and his successor, Zawahiri, maintained their militant focus on the “far enemy,” never articulating the precise parameters that would allow the caliphate to reemerge. IS would later argue that it was fulfilling bin Laden’s deepest desire, thereby bringing bin Laden into its jihadi ancestry and isolating Zawahiri as an ineffectual pretender. Indeed, the rapid pace of IS’s initial territorial gains in Iraq and Syria seemed to confirm, at least to true believers,that the time for the caliphate had arrived and was divinely sanctioned. Volunteers began arriving from around the world, much to the chagrin of Western nations that witnessed some of their fellow Muslim citizens abandoning their seemingly comfortable lives to join a jihadist organization committed to fostering global conflict (Taub 2015). And IS was quick to publicize images of recent arrivals from the West burning their passports and shouting jihadist slogans. In fact, provocation proved an essential feature of IS public relations, and propaganda of the deed became an all-too-common style: Middle Eastern Christian communities attacked, the men killed, and women sold into slavery; Western journalist held hostage and later executed; a Jordanian pilot burned alive in a cage; Egyptian Coptic Christians taken hostage and beheaded en masse. IS made images of these deeds public through social media and reprinted them in issues of Dabiq, the glossy, English-language online magazine it began to publish in July 2014.

In September 2014, a Global Coalition Against Daesh, also referred to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, formed to target IS strongholds, counter its propaganda, and prevent flows of fighters and funding; it has grown over the years to include some eighty-six countries around the world. In response, IS ratcheted up its taunting and bloodletting, and articulated a strategy of “remaining and expanding,” which entailed strengthening its hold over lands already under its control and bringing new territory into its orbit of influence. In the fifth issue of Dabiq, entitled “Remaining and Expanding,” IS announced the inclusion of several wilayat (provinces) into the caliphate: the Arabian Peninsula, Yemen, Sinai Peninsula, Libya, and Algeria (Dabiq 5:3). Its stated goal was to “reach into the homelands and living rooms of ordinary people living thousands of miles away in western cities and suburbs,” and it envisioned itself as a “global player” (Dabiq 5:36). And just as coalition forces started to attack IS territory, IS called upon its supporters to carry out attacks in the West: “If you can kill a disbelieving American or European (especially the spiteful and filthy French) or an Australian, or a Canadian, or any other disbeliever from the disbelievers waging war against the Islamic State, then rely upon Allah, and kill him in any manner or way however it may be” (Dabiq 5:37). After organized and lone-wolf attacks began to occur on a regular basis, the UN Security Council declared IS “a global and unprecedented threat to international peace and security” (The United Nations Security Council 2015).

At its peak, in late-2014, IS controlled over 100,000 square miles and a population of some 12,000,000 (Jones, et.al. 2015). By early 2015, however, coalition forces had begun to push IS fighters out of areas of Syria and Iraq, and the battle lines against IS expanded (and became more politically complicated) after Syrian President al-Assad, under pressure to reclaim lost lands and defend his beleaguered regime, negotiated for Russian military aid and ground support. It would take more than four years of intensive fighting to break IS’s control over the region. Urban warfare in the Iraqi cities of Ramadi, Falluja, Mosul, and Ramadi proved especially devastating for civilians and essential infrastructure. In March 2019, the final battle occurred in the Syrian town of Baghouz, bringing an end to the slowly diminishing territorial caliphate. Throughout these last years of fighting, terrorist attacks, either directly led by IS operatives or proxies, continued, often with dramatic effect. France, a member of the anti-IS coalition, was targeted several times: some 130 were killed and hundreds wounded in and around Paris in 2015, and Nice experienced a truck bomb attack on Bastille Day 2016, killing and wounding hundreds. Suicide bombers targeted Brussels airport and metro station in March 2016, resulting in thirty-six dead and some 300 wounded. A Russian airliner, with 224 passengers aboard, was downed over the Sinai Peninsula in October 2015, in retaliation for Russian-Syrian air campaigns against IS forces. Attacks in other locations around the world (Spain, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Afghanistan) speak to the ideological and tactical reach of IS, even as its “caliphate” was under siege.

Despite the March 2019 defeat at Baghouz, a small but effective group of IS insurgents has continued to operate in northern Syria, kept alive by the chaotic aftermath of war, limitations of the Assad regime’s power, foreign intervention, and the jihadists’ determination to maintain some semblance of the territorial caliphate. The group has carried out small scale attacks and thwarted efforts to dislodge it. IS leadership, however, has been under constant attack. Abu Bakr a-Baghdadi, the avowed caliph, was killed in a raid carried out by U.S. forces in October 2019; his replacement, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi, met a similar fate in February 2022; and Turkish forces claim to have killed the latest IS leader, Abu Hussein al-Quraishi, in May 2023. While IS power has diminished dramatically in its heartland, its various provinces have remained a tangible threat. According to the Global Terrorism Index, IS and its affiliates “remained the world’s deadliest terrorist group in 2022 for the eighth consecutive year, with attacks in 21 countries” (Institute for Economics & Peace 2023).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

IS portrayed itself as the true remnant of Islam in the modern world and defined its beliefs largely in relation to what it rejects among the dominant trends in Muslim societies, which it regards as unbelief (kufr). Like Islamism, IS framed its very existence as a return to or restoration of what had been lost by modern Muslims due to the impact of secularism and un-Islamic leadership. And like militant Islamism, it espoused a set of millennial ideas and practices that transforms Muslim societies, if not the entire world, into a battleground between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. This battleground took on territorial specificity once ISIS established the Islamic State (=caliphate) and invoked the traditional division between the abode of Islam and abode of unbelief (dar al-Islam, dar al-kufr).

After establishing its provisional capital in Raqqa, IS began a program to teach religious functionaries (imams and preachers) its “methodology of truth.” Those selected to participate had previously served in these roles in the area, but they needed IS sanction to continue. The book selected for the one-month seminar of instruction was written by Sheikh Ali al-Khudair, an influential Saudi Wahhabi scholar known for his past support of jihadist activities. Its appeal rested on its firm grounding in the teaching of the founder of Wahhabism, Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, and its willingness to confront the evils of the age and pronounce the takfir (declaring someone a kafir, unbeliever; excommunication) against sinful individuals, even if they are unaware of their sinfulness (Islamic State Report 1:3). Many of the religious experts affiliated with IS, those in charge of educating the Muslim masses and rendering religious judgments, are Saudis with a strong commitment to the kingdom’s Wahhabi doctrine, though not the royal family. In its publications, IS casts itself as Salafi-Wahhabi, with a strong aversion to “deviant” innovations that emerged within Islamic tradition after the lifetime of the pious ancestors (al-salaf al-salih), deviants identified as Shi’is, Asharis, Mu’tazilis, Sufis, Murji’is, and Kharijis.

IS embraces Salafism’s generic creedal focus on the oneness of God (tawhid) and the rejection of any beliefs or practices that detract from divine unity. It also, like Salafism, places great attention on the details of textual argumentation, legitimizing every decision with reference to the Qur’an and Sunna and presenting its interpretation as the only authentic one. Indeed, creedal and moral certainty informs everything IS does, and serves as a strong selling point for those modern Muslims searching for clarity in a world of half-truths and lies. IS committed itself to founding a “caliphate on Prophetic methodology,” a phrase used often in its literature to signal a return to authentic Islam and to lay “claim to both religious and political authority over all Muslims” (Olidort 2016:viii). Thus, the Muslim identity IS offers has no equal: it is above reproach in its adherence to correct belief and practice, and it induces a sense of truth and righteousness that permits easy judgment of other Muslims (Haykel 2009:33-38). Nowhere was this concern about Islamic legal and moral rectitude more apparent than in the way IS justified its use of violence, especially when the victims were fellow Muslims. In keeping with its movement orientation, IS shaped its creedal stance in the dynamic environment of the very violent conflict to which it had contributed. It was, in effect, carrying out brutal acts of violence, of terror, at the same time it was arguing for the virtue and necessity of these acts. The primary audience for this argument was the Muslim world, a world that seemed largely in agreement that IS had taken a dangerous turn and was threatening both Muslim lives and Islam’s image. In fact, IS had provoked an Islam vs. Islam debate on a global scale, and the terms of the debate included historical references to ongoing Muslim discourse about the nature of modern politics and the limits of legitimate rebellion.

Muslim critics of IS, including Islamists, often resorted to accusing the group of being or behaving like Kharijis, the notorious seventh-century sectarian movement known for its hyper-piety and violence against fellow Muslims. According to traditional Islamic sources, the Kharjis accused fellow Muslims of being apostates to justify their murder (takfir), sowed social and political dissension, and undermined the legitimacy of two of the four Rightly Guided caliphs in Sunni Islam. Indeed, mainstream Sunni orthodoxy emerged, at least in part, by defining itself over and against the actions and image of Kharijis (sometimes rendered Khawarij or Kharijites). In the mid-twentieth century, the name of this sect had been invoked by Muslim religious and political authorities to anathematize Islamists, whether moderate or militant, and to influence public opinion about Islamism, extremism, and the sanctity of the state; in Egypt, members of Society of Muslim Brothers, such as Hasan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb, were commonly linked to Kharijis in the media (Kenney 2006). For its part, IS viewed the accusation of being Khariji as propaganda intended to weaken the Muslim community by allowing the un-Islamic behavior of corrupt Muslims, especially political leaders, to continue. As a result, it did not hesitate, out of fear of being labeled Khariji, from passing judgment against what it deemed apostate Muslims and shedding their blood. Thus, even as IS rejected the label “Kharijis,” it engaged in the very behavior that had made the sect infamous. When first accused of being Khariji, IS responded in two ways: first, IS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-‘Adnani participated in a formal exchange of curses (what is referred to in Islamic tradition as mubahala) that asked God’s punishment if IS were in fact Khariji. This was part of a larger debate with other jihadist groups, during which one leader claimed that IS was “more extreme than the original” Kharijis (Dabiq 2:20). Second, in what appeared a manufactured situation, IS uncovered a Khariji cell operating within its territory and threatening to attack the caliphate. The cell was subsequently “disbanded and punished” according to Islamic law, making it seem that IS acknowledged illegitimate violence of the Kharjis (Dabiq 6:31).

In its defense of violence, even the glorification of it, IS adopted an interpretive stance, common among all reformist Muslims, of framing modern challenges in terms of those that faced the Prophet Muhammad. But the focus for IS was the broader historical condition in which Muhammad had to introduce the message of Islam (referred to as jahiliyya or ignorance) and how he dealt with the challenges. Islamic tradition casts jahiliyya as the time before the advent of Islam, before Muhammad brought truth and knowledge; it is the sinful period during which Arabs had reverted to depravity and polytheism. Put simply, jahiliyya represents an inversion of Islam. Following a line of thought elaborated by Qutb in his radical primer Milestones, and then adopted by Islamist militants everywhere, IS portrayed the modern world, particularly Muslim societies, as drowning in a sea of jahiliyya. As a result, sinfulness and corruption reign; Muslims have lost their way and are in need of guidance; and many Muslims have forgotten or renounced Islam falling into the recurring condition of jahiliyya. The only response, so the argument goes, is for true believers to act as Muhammad and his early followers had, to oppose and eliminate the pagan forces of jahiliyya by waging jihad on behalf of the faith. In one of the many textbooks produced by IS, the famous Battle of Badr (624CE), between Muhammad’s army of believers and the polytheists of Mecca, is recounted for dramatic effect. Readers are encouraged to glean important life lessons from the experience of the Islamic army in the battle: that God is on the side of believers, that “terrorizing (irhab) unbelievers and frightening them” is required, that “killing families is a requirement when necessary and is a way of restoring [society’s] well-being” (Olidort 2016:21).

IS wanted Muhammad’s confrontation with jahiliyya to come alive for Muslims, to both inspire them and compel them to make a life-altering decision. And that decision was IS’s own caliphate, a carved-out exception in the modern world where Muslims could live under Islamic law, where they could finally lead true Muslim lives. Of course, IS did more than invite; it claimed that it was every Muslim’s duty (fard ayn) to emigrate (hijra) from jahiliyya to the Islamic State, to submit to the authority of the caliph, and to wage jihad.

In IS propaganda, the formation of the Islamic State and declaration of the caliphate had given rise to a new doctrinal obligation; these events had brought about “the extinction of the grayzone,” just as the coming of Muhammad created a clear-cut choice between jahiliyya and Islam (Dabiq 7:54-66). Everyone now had to make a decision, and live or die with the consequences. Failure to act was not an option, for it meant siding with the unbelievers and falling into apostasy. If migration was not an option for those true believers living among infidels in the West, the land of the Crusaders, they could avoid a “death of jahiliyya” by declaring their oath of loyalty (bay’a) to the caliph and fighting to the death wherever they were (Dabiq 9:54). Here again, IS was directing

Muslims to follow in the footsteps of the Prophet Muhammad, who also emigrated to ensure Islam’s survival and success. Much to the horror of many Muslims, IS also drew on the example of the Muhammad to justify gruesome acts of violence, such as the immolation of a Jordanian pilot shot down during a bombing run over IS territory or the beheading of captives (Dabiq 7:5-8). [Image at right] “Prophetic methodology,” it seems, allowed IS to terrorize and kill at will.

For IS, individuals who performed the hijra and took up jihad were participating in a larger God-ordained plan for humanity that was unfolding in the region: the coming great battle (al-malahim al-kubra) that precedes and sparks the final hour. Syria was linked with a number of end time prophecies in Islamic tradition, and IS drew on them to demonstrate the historic importance of events materializing within the caliphate and to inspire Muslims to  participate. The title of the IS magazine, Dabiq, [Image at right] for example, refers to a site in Syria, attested to in hadith, where the final battle between Muslims and Romans (understood to mean Christian Crusaders) will take place, and which will result in a great Muslim victory, followed by the signs of the hour: the appearance of the Antichrist (Dajjal), the descent of Jesus, and Gog and Magog. A provocative reference to this prophecy, supposedly made by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, appeared on the content page of each issue of the magazine: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify, by Allah’s permission, until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.”

participate. The title of the IS magazine, Dabiq, [Image at right] for example, refers to a site in Syria, attested to in hadith, where the final battle between Muslims and Romans (understood to mean Christian Crusaders) will take place, and which will result in a great Muslim victory, followed by the signs of the hour: the appearance of the Antichrist (Dajjal), the descent of Jesus, and Gog and Magog. A provocative reference to this prophecy, supposedly made by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, appeared on the content page of each issue of the magazine: “The spark has been lit here in Iraq, and its heat will continue to intensify, by Allah’s permission, until it burns the crusader armies in Dabiq.”

IS played on prophesies of this kind to heighten attention to its unique time in history and the significance of the fighting, in the Islamic State proper and beyond. This fighting eventually enmeshed both regional and international powers and seemed to confirm IS claims of a coming battle of historic, if not cosmic, significance. Every minor battle, every inspirational speech, every newly declared province, every terrorist attack, every military response by the West, and every new Muslim arrival to the Islamic State became another sign of prophecies being fulfilled and the coming ultimate conflagration that will end with Islam’s global victory. Even a seeming breach of Islamic ethics provided an occasion to promote the unique historical period in which people were supposedly now living. When IS encountered Yazidis, an ancient Mesopotamian people with a syncretic set of religious beliefs and rituals, in the Nineveh province of Iraq, it treated them as polytheists (mushrikun), not monotheists, and, following Islamic legal rulings, saw fit to enslave their women. In its discussion of this decision, IS drew attention to the fact that “slavery has been mentioned as one of the signs of the Hour as well as one of the causes behind” the coming great battle (Dabiq 4:15). This incident was revisited in a later issue of Dabiq by a female writer, Umm Sumayyah al-Muhajirah, who defended the decision to enslave women and used it to taunt IS enemies:

I write this while the letters drip of pride. Yes, O religions of kufr altogether, we have indeed raided and captured the kafirah women, and drove them like sheep by the edge of the sword…Or did you and your supporters think we were joking on the day we announced the Khilafah upon the prophetic methodology? I swear by my Lord, it is certainly Khilafah with everything it contains of honor and pride for the Muslim and humiliation and degradation for the kafir (Dabiq 9:46).

The writer ends the piece in a provocative and insulting aside, claiming that, if Michelle Obama were to be enslaved, she would not earn much of a profit.

Muslims who joined IS became, intentionally or not, part of its mythic narrative of the coming apocalypse, but they also entered a social world, in which people had been invited to lead real lives, with families, homes, and jobs. As William McCants points out, IS blurred the lines between eschatological expectations of the coming of the long-awaited messiah (mahdi) and the practical responsibilities of running the caliphate: “Messiah gave way to management. It was a clever way to prolong the apocalyptic expectations of the Islamic State’s followers while focusing them on the immediate task of state building” (McCants 2015:147). Of course, death would eventually come for many who were drawn in by talk of the apocalypse, but life in the caliphate also had an air of normality, proof that it was in fact a “state.”

Through its media outreach, IS appealed to Muslims around the world to emigrate to the newly established Islamic State, and to contribute to the only place where Muslims can enjoy the fruits of a true Islamic society, where Islamic law is enforced and Muslim brotherhood comes naturally. People with professional backgrounds were specifically targeted because they would bring much-needed skills for the growing community. The benefits of life within the boundaries of the Islamic State were touted as material and spiritual: newly arrived families were promised homes (sometimes confiscated ones), men were promised wives (sometimes enslaved ones), and social services were established to provide for the needy. IS was reported to have paid for the weddings and honeymoons of some of its fighters. Indeed, IS went to great lengths to show that it had established a workable society, with an Islamic police force, collection and distribution of charity (zakat), care for the orphans, and a consumer protection office with a number to call for complaints (Islamic State Report 1:4-6). And there were plans, never actualized, to mint coins for use within the umma (community), in an effort to create a “financial system” distinct from that of the Western-dominated world (Dabiq 5:18-19). In an article entitled “A Window into the Islamic State,” images of people engaging in repairing bridges and the electrical grid, street cleaning, caring for the elderly, providing child cancer treatment attested to IS’s efforts to meet the basic needs of Muslims (Dabiq 4:27-29). Another article entitled “Healthcare in the Khilafah” claimed that IS was “expanding and enhancing the current medical care” and has opened training colleges for medical professionals in Raqqa and Mosul (Dabiq 9:25).

Such everyday images, however, stand in stark contrast to other promotional references: to the final battle and the end time, and to photos of grisly beheadings, mass executions, stoning of adulterers, and martyrdom operations. But it is precisely this blending of the mundane and the murderous, of worldly and millennial expectations, that infused IS propaganda during the heady days of its caliphal rebirth. The life of jihadis in the Islamic State, it seems, had to be lived on the knife’s edge of history and the apocalypse.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

IS advocated the traditional rituals linked to Sunni orthopraxis and imposed them within the area under its control. It also supplemented these with ritual-like activities related to state formation and the return of the caliphate. It is no exaggeration to say that IS, like many jihadi groups turned jihad into the sixth pillar of Islam. The group praised the importance of jihad (for purifying the soul, defeating the enemy, restoring the caliphate, and taking revenge for a history of Western aggression) at every opportunity and hurled insults at those Muslims who portrayed Islam as a religion of peace and, thereby, surrendered to Western pressure. Like prayer and fasting during Ramadan, jihad was obligatory for Muslims, according to IS, and so was performing the hijra, the emigration from the abode of unbelief to the abode of Islam, the Islamic State. Another “ritual” that took on an obligatory nature with the establishment of the caliphate was the oath of allegiance (bay’a), given to the caliph, often in a public setting, to demonstrate a person or group’s submission to the caliph’s authority. Staged photo ops of oaths being offered to al-Baghdadi, IS’s caliph, have appeared in various issues of Dabiq, and militant movements in other countries have sent their oaths, either via delegates or Twitter, declaring their allegiance and renaming themselves provinces of the Islamic State.

Perhaps the most dramatic, and troubling, ritualized activities carried out by IS were the public punishments and executions. IS prohibited smoking cigarettes and punished its own fighters with whippings and beatings for indulging. Those caught watching pornography or taking drugs were also beaten. Thieves had their hands chopped off or worse. Those found guilty of adultery were put to death by stoning, and homosexuals were tossed off buildings. Such displays drew large crowds, most of the onlookers coerced to attend, and video clips captured people cheering and calling for the guilty to be punished. Enforcing Islamic law, and being seen doing so, was in large part what justified the existence of IS, and the results were sometimes grudgingly respected. In a region where law and order were subject to arbitrary enforcement and corrupt officials, IS gained a reputation for honesty and efficiency. Such was the lived reality of citizens in the states that IS had supplanted (Hamid :2016 220-21).

While not a ritual per se, martyrdom became an essential feature of IS’s military tactics and mythology. Suicide bombers were regularly deployed at the outset of an attack, to take out defensive outposts and shock the enemy into a state of fear. According to Islamic tradition, a Muslim could achieve no higher honor than death in battle against the enemies of Islam, and IS propaganda was replete with images of those jihadis who had taken that final transformative step. Muslims who joined IS were reinventing themselves, separating themselves from family, friends, and work to make a new beginning. Performing the hijra was the first step, followed by engaging in jihad. Becoming a martyr completed the transformative path and linked the honored dead with those still waging jihad. Indeed, the martyred dead spoke, as it were, from the grave through inspirational messages dictated or recorded before death, advertisements to join the cult of blood and sacrifice. As the message of one martyr made clear, death was not simply the ultimate expression of jihadi conviction; it also served as a definitive proof text of the faithful life one has led:

My words will die if I do not save them with my blood. My emotions will be put out if I do not inflame them with my death. My writings will testify against me if I do not produce evidence of my innocence of hypocrisy. Nothing except for blood will fully assure the certainty of any evidence (Dabiq 3: 28).

Memorializing such sacrifices (in videos, poetry, and song) provided a powerful boost to the fighting spirit and identity of those who remained: “For jihadis, acts of martyrdom are the building blocks of communal history” (Creswell and Haykel 2015:106).

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

IS was born in a competitive jihadi environment, with numerous movements and leaders vying to attract recruits and financial support. All had grown out of the same militant Islamist soil and drew on the teachings and inspiration of an array of radicalized thinkers, from Qutb to bin Laden. Under the leadership of Zarqawi, ISI, the precursor to IS, distinguished itself by its ruthless acts of violence, directed largely against Iraq’s Shi‘i population. When IS declared the return of the caliphate and named al-Baghdadi the caliph of the age, it set itself apart from other militant groups, and created a crisis of legitimacy and expediency within jihadist ranks. Whether Baghdadi was the best figure to assume this historic role was an ethical and legal question for many jihadists at the time. IS attempted to address any doubts about al-Baghdadi’s leadership in the first issue of Dabiq, which ran under the title “The Return of Khilafah.” One story in the issue quoted at length from al-Baghdadi’s inaugural speech and referred to him as Amirul-Mu’minin or Commander of the Faithful; another provided a historical argument about the fusion of religious and political affairs under Muslim leaders like Abraham and Muhammad, and the need to restore this model of leadership (Dabiq 1:6-9, 20-29). But IS effectively upstaged the competition, and silenced the debate about al-Baghdadi’s legitimacy, by winning the image war on social media and by backing up its claims of authority with military prowess and territorial expansion. Bold claims and bold actions, then, transformed this militia-cum-state into a preeminent leadership role. What al-Qaeda aspired to become post-9/11, IS turned into a reality, and it did so by redefining the rules of militant Islam: movement structure gave way to state-building; distinctions between “near enemy” and “far enemy” became moot as IS targeted enemies (Muslim and non-Muslim) everywhere; and the magnetic force of a reawakened and victorious caliphate lured Muslim recruits from around the world.

Once the organizational structure of IS became a quasi-territorial state, it exposed itself to the same kind of targeted attacks on infrastructure and supply lines that IS deployed against Iraq and Syria. But the claim of being a caliphate, not a nation-state, gave IS rhetorical latitude on challenges to its territorial sovereignty. The reinvented caliphate was an exception in the world of nation-states, and one might argue that was IS’s intent: to create an exceptional place, literally and figuratively. Unlike modern nation-states that define themselves by their borders, the boundaries of the caliphate can shift without undermining its theoretical integrity. Historically, the shape of caliphal lands on maps was always changing, as was the capital city of the caliphate. Reinvented in an era of nation-states, the caliphate appeared anachronistic, and was, but that is precisely the point IS wished (and still wishes) to make. In a sense, IS was attempting to intervene, on a grand scale, in what Muslim reformers since the nineteenth century had identified as a decline in Islamic power and Muslim self-confidence, a decline made apparent by the rise of the West and its imperialist expansion into Muslim lands. The modern period, according to the reformist narrative, demanded a rethink about what Islam once was and could be again if Muslims rededicated themselves and found the lost spirit of Islam. By changing the modern map of the Middle East, and the structure and language of governance, IS hoped to reawaken the true spirit of Salafi reform and to reset the clock on modernity. It was a fantasy of sorts, but one that resonated (and still does) with many who continue to wrestle with the narrative of disappointment that has informed modern Muslim consciousness.

Of course, a reawakened caliphate required a good deal of reinvention, meaning that aside from its name and other historical references, it was no more authentic than that other invented tradition which it competed: the nation-state. In fact, IS organized itself and ruled over the territory it controlled much like a nation-state. It was a command-and-control operation infused with religious references and figures. Baghdadi served as the “commander and chief” or caliph, with advice provided by a cabinet (shura council composed of religious specialists) and an array of deliberative councils spanning a range of state functions: military, finance, legal, intelligence, media, security…etc. As caliph, Baghdadi had ultimate authority, though he can in theory be removed from office by the shura council. Two deputies had authority to preside over affairs in Iraq and Syria, and governors were named to oversee everyday rule in the various provinces. The precise means by which orders were passed along the chain of command and finances routed or hidden have remained open questions, though various raids over the years have provided insight into the inner-workings and thoughts of a leadership that was clearly resilient and determined to continue the fight. IS learned how to withstand the losses inflicted by coalition forces, maintaining its command-and-control infrastructure, economic activity, and flow of recruits, which is to say that, for a time, it truly functioned like a state…until it did not.

After the caliphate was defeated in 2019, noncontiguous provinces, under the ongoing banner of the Islamic State, became the organizational structure, though its coherence as an operational movement has proven difficult to assess. What seems clear is that planning for a post-caliphate continuation of jihad began before IS reached its height of power in Syria and Iraq, suggesting that the leadership, despite its rhetorical bravado, recognized that its consolidated power would be short-lived. Working with existing militant groups in places like Afghanistan and the Egyptian Sinai, IS offered training and financing in exchange for allegiance and renaming. These provinces expanded the IS brand and the jihad, along with providing another battlefield to which fighters could be dispersed as the territorial caliphate shrank. As early as 2015, IS negotiated with local militants in Afghanistan, a jihad-friendly environment with a weak centralized-state, mountainous terrain, and ongoing Taliban resistance. This resulted in the creation of the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) or IS-K, a group that has grown larger and bolder over time, sometimes working with other militants like the Taliban, always working against al-Qaeda. However, after U.S. forces were withdrawn from Afghanistan in August 2021, IS criticized the Taliban, asserting that the American departure was simply “a peaceful transfer of power from one idolatrous ruler to another…the substitution of a shaven idolatrous ruler for a bearded one” (Bunzel 2021). al-Qaeda, by contrast, congratulated the Taliban for evicting the Americans and continuing to wage jihad. A competition between militant groups, rooted in stated tactics and goals, is playing out in Afghanistan, and elsewhere, and IS has tried to position itself as the most committed and uncompromising. Given al-Qaeda’s deference to and dependence on the Taliban, and the Taliban’s limited agenda of Islamizing Afghanistan, IS seems destined to waging jihad against fellow militant Islamists.

In other provinces, IS affiliates are adjusting to complex political, ethnic, and religious landscapes, often exploiting existing divisions and grievances to secure allies (even if only temporary), fighters, and resources. Africa has witnessed a dramatic expansion of IS interest and activity, starting in 2015 when Boko Haram, a violent Islamist sectarian group based in northeastern Nigeria, pledged allegiance to IS and was rebranded the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). Founded in 2002, Boko Haram, meaning “Westernization is Sacrilege,” advocated a reform of Nigerian society, in particular its corruption and poverty, by instituting Islamic law and shunning all forms of Western influence in education, culture, and morality. Its ongoing attacks on civilians, especially schools, and expansion into new territory led the government to ban the group and mount an offensive; by 2015, Boko Haram, under heavy government assault, sought to gain assistance and reinvigorate its forces and image by joining IS. In the same year, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, a Salafi-jihadi leader with a long career of militant movement activism in the Sahel, declared his oath of allegiance to IS, forming what would be called the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). A sub-Saharan region cutting across many countries (from Senegal to Chad) and roiling with ethnic and religious factions, the Sahel has become home to criminal gangs, rebel movements, and jihadists, both domestic and foreign. Though not an official province, ISGS espouses the aims of IS and both competes and cooperates with other groups, including al-Qaeda, to carry out attacks on Western outposts. IS fighters in war-torn, post-Gaddafi Libya are now operating in a similar contested and chaotic environment.

The ostensible goal of the provinces and affiliate groups is to create an Islamic state, but the more immediate objective, in the absence of sufficient military force, is to foment instability and demonstrate that the jihad continues. As was the pattern in Iraq and Syria, the strategy is to enter already destabilized regions, establish makeshift command-and-control infrastructure, and plan attacks that communicate the jihadist threat: to local and regional governments, to other jihadist groups, and to the West. And with the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS still in place, IS knows that the world is getting the message. Every year, the coalition issues a communique, outlining IS activities in its provinces and reaffirming the members continued determination to eliminate or, at least, contain the extremists (Joint Communiqué by Ministers of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS 2023).

Speculation abounds regarding the organizational structure of the provinces, communication between them, and how they are funded. Each region seems to have a certain operational independence and responsibility to find resources (human, material, and financial), a situation no doubt driven by efforts of the coalition to disrupt flows of communication, money, and fighters. In fact, IS has struggled to keep its propaganda message alive. Once an effective means of recruitment and messaging, social media has become highly restrictive, making it more difficult to post violent video clips and invite Muslims to make the “journey to jihad” (Taub 2015; Mazzetti and Gordon 2015). The leadership of IS has also been significantly weakened, both symbolically and in human terms. Each time a caliph, the foundational claim of IS authority over the Muslim world, has been named, he has been targeted and killed by coalition forces. Provincial leaders and other known militant Muslim actors have also been taken off the battlefield. Of course, replacements eventually emerge from the ranks (though at the time of this writing no new caliph has been identified), but the constant fear of being targeted eats into morale and undermines the management of jihad.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

With the demise of the caliphate, IS has returned to its jihadi terrorist organization roots, but the conditions have changed, and it’s important to consider the implications for the current global jihadist scene and the forces arrayed against it. Initially, IS succeeded by playing on and exacerbating political and social tensions that preexisted and facilitated its rise in Iraq and Syria. Like its global-jihadist ancestor al-Qaeda, IS operated opportunistically, taking advantage of weak states and putting pressure on ethnic and sectarian divisions. In a very real sense, its survival depends on continuing this strategy, but it must now be implemented in different environments throughout Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia with each province or affiliated group having semi-independent command and control. Put differently, IS currently functions like a transnational terrorist or crime organization with self-contained, self-sustaining cells. The cells adapt to their respective environments, carving out niches in the socio-political and criminal landscape, making temporary alliances as needed, feeding off the land, and plotting opportunities to strike. In this scenario, “global terrorism” can be difficult to distinguish from the existing social and political realities that challenge governments and law enforcement agencies around the world. And countering the threat of IS, along with that of other terror groups, becomes more complex, nuanced, and costly, to such an extent that many governments and citizens have come to accept that, while the official “War on Terror” has ended, the unofficial one continues unabated. Of course, the threat level has lessened and the threat itself has evolved, but IS remains a source of social, political, economic, and cultural instability, especially for those living in the immediate vicinity of its provinces or affiliated groups.

The Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, then, will not be able to declare victory soon or, perhaps, ever. It can only hope to preempt large-scale attacks, mitigate the impact of lesser ones, and continue to engage in long-term counterterrorism efforts, both hard and soft. Western nations (the ones with sufficient resources) have developed the techno-surveillance capacity to disrupt or prevent future attacks, though only after experiencing the kind of terrorist violence that still plagues other countries. As one insightful analyst points out, “[w]ell-resourced states will be able to buy their way to order, whereas weaker ones will not” (Hegghammer 2021 52). And the cost of IS goes far beyond counterterrorism measures. The loss of life and damage to infrastructure in Iraq and Syria has yet to be quantified. Iraq has started the difficult path of recovery, trying to rebuild essential services, effective governance, and national unity; healing the country’s deep rift between Sunnis and Shi’as has no easy short-term fix. Syria is all but a failed state, with swaths of territory under the control of Turkish, Kurdish, and rebel forces, along with a remnant of IS fighters; the Assad government is attempting to shed its pariah status, at least in the Arab world, but it owes its political survival to Iran and Russia and has become financially dependent on international aid agencies.

Refugees from Iraq and Syria, in the hundreds of thousands, are scattered across the region, and the number of internally displaced people is equally high; many will never return to their original homes. Admittedly, IS is not responsible for all the chaos that has enveloped the two nations. The civil war in Syria started years before IS established its caliphate, and Iraq had gone through decades of autocratic misrule, foreign occupation, and civil unrest. As noted, IS stoked this instability to gain a Salifi-jihadist foothold. More directly linked to years of IS war-making/state-making is the unresolved problem of how to deal with captured IS fighters and their families. Some 60,000-70,000 detainees, many of them children, are being held at two camps in northern Syria, al-Hol and Roj, by the Kurdish-led Syrian Defense Force. Among the fighters are both Syrian and foreign nationals, and the same is true of family members. Efforts to repatriate foreign nationals has been slow, with many countries balking at resettling radicalized fighters or their families. Those researching the problem report that repatriated children adjust well when given a chance, especially those under twelve, but “many governments refuse to take these young nationals back, citing national security concerns or fearing public backlash” (Becker and Tayler 2023). No judicial process has been established to sort out who among the detainees might be prosecuted or otherwise rehabilitated, and with repatriations stalled, the situation has become a human rights crisis. Conditions in the camps are stark and create a potential breeding ground for the very radicalism coalition forces are opposing and, ideally, preempting. Fears that fighters might escape and continue the jihad are rife. “It’s a problem from hell,” according to one security expert, “and until the international community comes together to clean this up, it’s a bomb waiting to go off” (Lawrence 2023).

Finally, a note on the Islamist politics that gave rise to IS and informs its propaganda and stated raison d’etre. Central to Islamism is the twined notion that 1) Islam (broadly understood) provides all the essential teachings and truths that Muslims and Muslim societies need to survive and succeed in the modern world, and 2) the Western path of secular development is incompatible with Islam and Muslim identity. Viewed one way, this is a simple assertion of Muslim authenticity and of the need to carve out a modern way of life compatible with Islamic values. But the assertion arose at a time when most leaders of Muslim-majority countries, many of which were living under or had experienced colonial rule, began to adopt development programs and sometimes rhetoric that mimicked the so-called “Western model.” As a result, Islamists emerged as national opposition voices, ones that challenged mainstream thinking about both religion and politics in the modern world. Moderate Islamists went on to teach the benefits of Islam as a path of salvation and modern prosperity and to critique the failures of Western systems of governance (capitalism, communism, socialism) adopted in their respective nations; militant Islamists, grown tired of the seeming failures of these systems and the anti-Islamist oppression of rulers, shifted from teaching to the sword or AK-47. IS and other jihadi organizations have pushed the once nation-state-centric voice of Islamist opposition, backed up by well-armed militias, onto the world stage, transforming Islamism into an ideological catchall for Muslim mobilization and resistance. Thus, what had been a struggle to normalize Islamist politics within the framework of Muslim-majority nation-states has become a global effort to extinguish jihadist firestorms fueled by failures of nation-building, economic injustice, and inequality between the developed and developing worlds. Such large-scale and complex problems lie beyond the reach of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, even though many of its members, in both the Muslim world and the West, have contributed to them.

IMAGES

Image #1: IS battle flag.

Image #2: Sayyid Qutb’s radical primer, Milestones.

Image #3: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

Image #4: Abu Bakr a-Baghdadi.

Image #5: Osama bin Laden.

Image #6: A Jordanian pilot burned alive in a cage.

Image #7: An issue of Dabiq,

REFERENCES

Becker, Jo and Letta Tayler. 2023. “Revictimizing the Victims: Children Unlawfully Detained in Norther Syria.” Human Rights Watch, January 27. Accessed from https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/01/27/revictimizing-victims-children-unlawfully-detained-northeast-syria on 25 June 2023.

Bin Laden, Osama. 2005. Messages to the World: The Statements of Osama bin Laden, edited by Bruce Lawrence, translated by James Howarth. London: Verso.

Bunzel, Cole. 2021. “Al Qaeda Versus ISIS: The Jihadi Power Struggle in Afghanistan.” Foreign Affairs, September 14. Accessed from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2021-09-14/al-qaeda-versus-isis?utm_medium=promo_ on 25 June 2023.

Cockburn, Patrick. 2015. The Rise of the Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution. London and New York: Verso.

Creswell, Robyn and Bernard Haykel. 2015. “Battle Lines.” The New Yorker, June 8: 102-08.Dabiq. Issues 1-9.

Devji, Faisal. 2005. Landscapes of the Jihad: Militancy, Morality, Modernity. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Doxee, Catrina, Jared Thompson and Grace Hwang. 2021. Examining Extremism: Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). Blog Post, Center for Strategic & International Studies. Accessed from https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-islamic-state-khorasan-province-iskp on 25 June 2023.

Hamid, Shadi. 2016. Islamic Exceptionalism: How the Struggle over Islam is Reshaping the World. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Haykel, Bernard. 2009. “On the Nature of Salafi Thought and Action.” Pp. 33-57 in Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement, edited by Roel Meijer. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hegghammer, Thomas. 2021. “Resistance if Futile: The War on Terror Supercharged State Power.” Foreign Affairs 100:44-53.

Institute for Economics & Peace. 2023. Global Terrorism Index 2023: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney, Australia. Accessed from https://www.visionofhumanity.org/resources on 25 June 2023.

Islamic State Report. Issues 1-4.

Jones, Seth G., James Dobbins, Daniel Byman, Christopher S. Chivvis, Ben Connable, Jeffrey Martini, Eric Robison, and Nathan Chandler. 2017. Rolling Back the Islamic State. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Accessed from https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1912.html on 25 June 2023.

Kenney, Jeffrey T. 2006. Muslim Rebels: Kharijites and the Politics of Extremism in Egypt. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lawrence, J.P. 2023. “ISIS fighters and families under guard in Syria pose ‘problem from hell’ for US forces.” Stars and Stripes, April 10. Accessed from https://www.stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/2023-04-10/isis-prison-syria-military-centcom-9758748.html on 25 June 2023.

Mazzetti, Mark and Michael R. Gordon. 2015. “ISIS is Winning the Social Media War, U.S. Concludes.” The New York Times, June 13, A1.

McCants, William. 2015. The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. New York. St. Martin’s Press.

Olidort, Jacob. 2016. Inside the Caliphate’s Classroom: Textbooks, Guidance Literature, and Indoctrination Methods of the Islamic State. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Accessed from https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/inside-caliphates-classroom-textbooks-guidance-literature-and-indoctrination on 25 June 2023.

Roy, Olivier. 2004. Globalized Islam: The Search for a New Ummah. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schmidtt, Eric. 2015. “A Raid on ISIS Yields a Trove of Intelligence.” The New York Times, June 9, A1.

Taub, Ben. 2015. “Journey to Jihad.” The New Yorker, June 1:38-49.

The United Nations Security Council. 2015. “Security Council ‘Unequivocally’ Condemns ISIL Terrorist Attacks, Unanimously Adopting Text That Determines Extremist Poses ‘Unprecedented’ Threat.” Meetings Coverage, Security Council. United Nations. Accessed from https://press.un.org/en/2015/sc12132.doc.htm on 25 June 2023.

U.S. Department of State. 2023. Joint Communiqué by Ministers of the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS. Media Note, June 8. Accessed from https://www.state.gov/joint-communique-by-ministers-of-the-global-coalition-to-defeat-isis-3/ on 25 June 2023.

Weiss, Michael and Hassan Hassan. 2015. ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror. New York: Reagan Arts.

Wright, Lawrence. 2006. “The Master Plan.” The New Yorker, September 11:49-59.

Publication Date:

29 June 2023