SŌKA GAKKAI TIMELINE

1871 (6 th day of the 6 th month): Makiguchi Tsunesaburō, founder of Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai (Value Creation Education Study Association), was born Watanabe Chōshichi in a town now called Kashiwazaki, Niigata Prefecture, Japan. He was adopted at the age of six into the Makiguchi family and moved to Otaru, Hokkaidō at the age of thirteen.

1889: Makiguchi entered Hokkaidō Normal School (predecessor to Hokkaido University of Education) in Sapporo. Upon graduation, he began teaching at the Normal School’s attached elementary school.

1893: Makiguchi changed his given name to Tsunesaburō.

1900 (February 11): Toda Jōsei, second president of Sōka Gakkai (Value Creation Study Association), was born Toda Jin’ichi in Ishikawa Prefecture. He moved with his family to Ishikari, Hokkaido two years later.

1901 (April): Makiguchi moved with his wife and children from Sapporo to Tokyo.

1903 (October 15): Makiguchi published his first major book, Geography of Human Life, (Jinsei chirigaku ).

1910: Makiguchi joined the Kyōdokai (Home Town Association).

1917: Toda obtained an elementary school teaching license and began teaching at Mayachi Elementary School in Yūbari, Hokkaido.

1920: Toda visited Makiguchi upon moving to Tokyo. Makiguchi helped Toda obtain a position teaching elementary school in the imperial capital, and the two began a lifelong mentor-disciple relationship.

1922 (December): Toda quit teaching at Mikasa Elementary School and left the profession thereafter.

1923: Toda founded a private academy called Jishū Gakkan that was dedicated to preparing elementary school students for secondary school entrance examinations; the academy’s pedagogy was based on Makiguchi’s theories of pragmatic instruction. Toda changed his given name to Jōgai (“outside the fortress”).

1928 (January 2): Ikeda Daisaku (originally Taisaku) was born in what is now the Ōmori neighborhood of Ōta Ward, Tokyo.

1928 (June): Makiguchi was convinced by fellow elementary school educator Mitani Sōkei to dedicate himself to Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism. Toda later followed his mentor’s example.

1930 (November 18): Makiguchi published Volume One of Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ( System of Value-Creating Educational Study ); Toda oversaw the publication of this text and suggested the term sōka, or “value creation,” as a title for Makiguchi’s educational theories. This publication date has subsequently been memorialized as Sōka Gakkai’s founding moment.

1932: Makiguchi retired from schoolteaching.

1935: Makiguchi and Toda began publishing the magazine Shinkyō (New Teachings), which bore the byline “educational revolution, religious revolution” (kyōiku kakumei / shūkyō kakumei ).

1937 (January 27): The inaugural formal meeting of Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai was convened at a Tokyo restaurant .

1940: The Japanese government enacted the Religious Corporations Law and Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai came under increased scrutiny by the Special Higher Police. Despite this, Makiguchi and other Gakkai leaders dedicated the next several years to organizing hundreds of study meetings and engaging enthusiastically in shakubuku, the form of proselytization promoted within Nichiren Shōshū tradition. After Gakkai adherents took up shakubuku in earnest, the organization grew to more than five thousand registered members by 1943.

1940 (October 20): Makiguchi was appointed Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai’s first president, and Toda its general director.

1941 (June 20): Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai launched a new periodical titled Kachi sōzō (Value Creation).

1942 (May 10): The Japanese government ended Kachi sōzō ‘s publication at its ninth issue.

1943 (July 6): Makiguchi, Toda, and nineteen other Gakkai leaders were arrested in multiple locations during a coordinated police raid. They were charged with violating the Peace Preservation Law and detained thereafter at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. Makiguchi and Toda were the only two leaders who refused to recant their convictions.

1944 (November 18): Makiguchi Tsunesaburō died of malnutrition at the hospital ward in Sugamo Prison.

1944 (November 18): Toda, after months of intense study of the Lotus Sūtra and chanting the Lotus ‘s title namu-myōhō-renge-kyō (the daimoku) millions of times, experienced a vision in which he joined the innumerable Bodhisattvas of the Earth (jiyu no bosatsu).

1945 (July 3): Toda was released on parole, only a few weeks before Japan surrendered to Allied forces on August 15. He changed his given name from Jōgai to Jōsei (“holy fortress”) and set about reconvening the Gakkai.

1946 (March): Toda changed the name of the organization from Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai to Sōka Gakkai (Value Creation Study Association). The newly reformed group met on the second floor of Toda’s publishing and distance education company Nihon Shōgakkan.

1946 (May 1): Toda was appointed general director of Sōka Gakkai.

1947 (August 14): Ikeda accompanied a friend to a Sōka Gakkai study meeting; he joined the group ten days later.

1949 (January 3): Ikeda began working at Nihon Shōgakkan.

1950 (November 12): Toda resigned as Sōka Gakkai’s general director.

1951 (April 4): The first edition of the Seikyō shinbun (Holy Teaching Newspaper), the periodical that would become Sōka Gakkai’s primary media outlet, was published.

1951 (May 3): Toda accepted appointment as second president of Sōka Gakkai at a gathering of approximately 1,500 members.

1951 (May): The launch of the Great March of Shakubuku (shakubuku daikōshin) that saw Sōka Gakkai surge from relative obscurity into Japan’s largest new religious movement.

1951 (November 18): The first edition of the Shakubuku Doctrine Manual (Shakubuku kyōten) was published, a book which, for the next nineteen years, supplied Gakkai members with explanations of Nichiren Buddhist concepts and arguments to employ against “false sects” in the course of proselytizing.

1952 (April 27): The “Tanuki Festival,” an incident in which a group of Young Men’s Division members on a pilgrimage to the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji seized a Shōshū priest named Ogasawara Jimon.

1952 (April 28): The first edition of the New Edition of the Complete Works of the Great Sage Nichiren ( Shinpen Nichiren Daishōnin gosho zenshū) was published. Known as the Gosho zenshū or simply the Gosho, a single-volume collection of Nichiren’s writings that continues to serve as the organization’s primary source for its Buddhist practice. It was published on a date that commemorated Nichiren’s first chanting of namu-myōhō-renge-kyō (the daimoku) seven hundred years earlier.

1953 (January 2): Ikeda was appointed Young Men’s Division leader.

1953 (November 25): Ikeda changed his given name to Daisaku.

1953: Sōka Gakkai began holding written and oral “appointment examinations” (nin’yō shiken) to test youth leaders on Nichiren Buddhist doctrinal knowledge.

1954 (October 31): Toda reviewed ten thousand Young Men’s and Young Women’s Division members at Taisekiji from atop a white horse.

1954 (November 7): The Youth Division held its first sports competition on the grounds of Nihon University in Tokyo; this event served as the model for Sōka Gakkai’s subsequent mass performances.

1954 (22 November): Sōka Gakkai established a Culture Division (Bunkabu), a sub-organization dedicated primarily to selecting candidates to run in elections and to mobilizing members to gather votes.

1954 (December 13): Ikeda was appointed Sōka Gakkai’s Public Relations Director.

955 (March 11): In an event known as the “Otaru Debate” (Otaru montō), members of Sōka Gakkai’s Study Department challenged priests from the Minobu sect of Nichiren Buddhism to a doctrinal debate.

1955 (April 3): Members of Sōka Gakkai’s Culture Division won election in city councils in Tokyo wards and in other municipalities; this marked the first time Sōka Gakkai ran its own candidates for office.

1955: By the end of this year, Sōka Gakkai claimed 300,000 member households.

1956 (8 July): Sōka Gakkai ran six independent candidates for election to the House of Councilors (Upper House); three were elected.

1956 (August 1): Toda issued an essay titled “On the Harmonious Union of Government and Buddhism “ (Ōbutsu myōgō ron) in the Gakkai study magazine Daibyaku renge (Great White Lotus).

1957 (June): Gakkai members clashed with affiliates of Tanrō, a coal miner’s union in Yūbari, Hokkaidō, in conflicts over electioneering and collective bargaining.

1957 (July 3): The beginning of an event memorialized as the “Osaka Incident” took place. Ikeda Daisaku was arrested in Osaka in his capacity as Sōka Gakkai’s Youth Division Chief of Staff for overseeing activities that constituted violations of elections law.

1957 (September 8): Toda issued “Declaration for the Banning of the Hydrogen Bomb,” calling for the death penalty as punishment for evil people who use this weapon.

1957 (December): Sōka Gakkai surpassed Toda Jōsei’s stated goal of 750,000 convert households.

1958 (April 2): Toda Jōsei died of liver disease. By the time of Toda’s death, Sōka Gakkai claimed in excess of one million adherent households.

1958 (June 30): Ikeda was appointed head of Sōka Gakkai’s newly organized bureaucratic hierarchy, occupying the post of General Manager.

1958 (September 23): 70,000 Gakkai adherents gathered at Tokyo’s Gaien National Stadium to watch 3,000 fellow members perform in the organization’s fifth sporting competition.

1959 (June 30): Ikeda was appointed head of Sōka Gakkai’s board of directors.

1960 (May 3): Ikeda Daisaku was appointed third president of Sōka Gakkai.

1960 (October 2): Ikeda departed with fellow Gakkai leaders on a visit to the United States, Canada, and Brazil, officially inaugurating the spread of Sōka Gakkai into a global enterprise. This grip was followed by trips to Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Australia, India, and other places over the following years.

1961 (November 27): Sōka Gakkai formed the Clean Government League (Kōmei Seiji Renmei), which successfully ran nine candidates for the House of Councilors in January, 1962.

1962 (April 2): The first edition of Kōmei shinbun was published; this newspaper became the primary media outlet for political operations.

1963 (October 18): Sōka Gakkai’s Min-on Concert Association was founded; it sponsored thousands of artistic performances in ensuing years.

1964 (May 3): Ikeda abolished political subdivisions within Sōka Gakkai and declared that henceforth the group was to be a purely religious organization. Sōka Gakkai now claimed in excess of 3.8 million member households.

1964 (November 8): One hundred thousand Gakkai members participated in a Culture Festival ( bunkasai ) at National Stadium in Sendagaya, Tokyo. Sōka Gakkai staged numerous other massive Culture Festivals in subsequent years.

1964 (November 17): Ikeda announced the dissolution of Kōmei Seiji Renmei and the founding of the “Clean Government Party” (Kōmeitō).

1965 (January): Seikyō shinbun began carrying serial installments of The Human Revolution ( Ningen kakumei ), the novelized version of Sōka Gakkai’s history and Ikeda Daisaku’s biography that members came to regard as an essential text.

1965 (October): Between October 9 and 12, eight million members in Japan contributed more than 35.5 billion yen to the construction of the Shōhondō, a massive new hall to be constructed at Taisekiji to house the daigohonzon , the calligraphic mandala that serves as Sōka Gakkai’s and Nichiren Shōshū’s primary object of worship.

1967 (January 29): Twenty-five Kōmeitō candidates were elected to the House of Representatives (Lower House).

1968 (April 1): Junior and Senior High Schools (Sōka Gakuen) were founded in Tokyo, marking the start of Sōka Gakkai’s private accredited school system.

1969 (October 19): Sōka Gakkai launched the New Student Alliance (Shin Gakusei Undō) as its answer to the Student Movement protesting the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. 70,000 members of the Gakkai’s Student Division gathered in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park.

1969 (November): Events that came to be known as the genron shuppan bōgai mondai , or “problem over obstructing freedom of expression and the press” surrounding attempts by Kōmeitō and allies to forestall publication of the book I Denounce Sōka Gakkai.

1969 (December 28): Forty-seven Kōmeitō candidates were elected to the Lower House, and Kōmeitō received just over 10 percent of the popular vote. It was now the third largest party in the Japanese Diet.

1970 (January): Sōka Gakkai claimed 7.55 million member households.

1970 (May 3): In the wake of the I Denounce Sōka Gakkai scandal, Ikeda Daisaku announced the official separation of Sōka Gakkai and Kōmeitō and a new Gakkai policy of seikyō bunri , or “separation of politics and religion.”

1971 (April 2): Sōka University opened in Hachiōji, western Tokyo.

1971 (June 15): Takeiri Yoshikatsu, head of Kōmeitō, accompanied Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei to the People’s Republic of China as part of a mission that ushered in normalization of diplomatic relations between China and Japan.

1972 (May 5): Ikeda met for the first time with British historian Arnold J. Toynbee in the first of hundreds of dialogues with prominent figures. The “dialogue” format became a central feature of Gakkai media and propagation efforts after this point.

1972 (October): Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū celebrated the opening of the Shōhondō, a massive modern hall at Taisekiji that could accommodate more than six thousand worshippers.

1973 (May 3): Fuji Art Museum opened in Shizuoka; moved later to Hachiōji, next to Sōka University, and was renamed Tokyo Fuji Art Museum.

1974 (December 5): Ikeda met with Premier Zhou Enlai in Beijing.

1975 (January 26): Soka Gakkai International (SGI) was founded at a World Peace Conference in Guam, and Ikeda Daisaku was declared SGI president.

1976 (March): The tabloid Gekkan pen (Monthy Pen) began publishing a series of articles alleging liaisons between Ikeda and six women, including top Women’s Division leaders. Sōka Gakkai sued for defamation and the Tokyo District Court ruled in its favor.

1977 (October): Sōka Gakkai opened Toda Memorial Park, its first gravesite outside a Nichiren Shōshū temple and the first of thirteen massive mortuary facilities the group has built in Japan. Competition for Gakkai member graves began to escalate between Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū.

1977: The first major conflict between Ikeda Daisaku and the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood took place.

1978 (June 30): Sōka Gakkai issued a statement in the Seikyō shinbun reaffirming Nichiren Shōshū priestly lineage claims.

1978 (November 7): Ikeda led two thousand Gakkai administrators to Taisekiji on an “apology pilgrimage” (owabi tōzan).

1979: The Youth Division established a Peace Conference, and the Married Women’s Division and other subgroups soon followed with similar initiatives. World peace, in place within Sōka Gakkai since the early 1960s as a guiding theme, became a central organizational concern from this era onward.

1979 (April 24): Ikeda resigned as third president of Sōka Gakkai. He took the position Honorary President and retained his post as president of SGI. He maintained a low profile for approximately one year. Hōjō Hiroshi was inaugurated as Sōka Gakkai’s fourth president.

1981 (April): Sōka Gakkai registered as an NGO (non-governmental organization) with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

1981 (July 18): Akiya Einosuke was appointed fifth Sōka Gakkai president.

1983 (January 25): Ikeda issued his first annual “Peace Proposal.”`

1984 (January 2): Ikeda was reappointed as Nichiren Shōshū’s chief lay representative by the Shōshū’s Chief Abbot Abe Nikken.

1984 (September 29 and 30): The World Youth Culture Festival was held at Osaka’s Kōshien Stadium.

1990 (December): The second major conflict between Ikeda Daisaku and the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood took place. Acrimony between the Shōshū priesthood and the Sōka Gakkai leadership erupted in a series of missives between the two camps.

1991: Conflict between the priesthood and Sōka Gakkai leaders escalated.

1991 (November 28): In a final move, the priesthood issued a “Notice of Excommunication of Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū.” Henceforth, parishioners who wished to enter sect temples, including the head temple Taisekiji, were required to pledge that they were unaffiliated with Sōka Gakkai. Gakkai members were henceforth barred from pilgrimages to their principal object of worship.

1992 (August 11): Nichiren Shōshū issued a specific edict excommunicating Ikeda Daisaku.

1993 (October 2): Sōka Gakkai began conferring objects of worship ( gohonzon ) replicas made from a transcription of the daigohonzon mandala inscribed by the Shōshū Chief Abbot Nichikan in 1720. Gakkai members were instructed to turn in their old gohonzon and receive new ones directly from Sōka Gakkai.

1995 (January): In response to the January 17 Hanshin Awaji Earthquake that devastated the city of Kobe and the surrounding region, Sōka Gakkai opened ten Culture Centers to refugees, mobilized thousands of member volunteers, and gathered over 230 million yen in relief funds.

1998 (May): Nichiren Shōshū destroyed the Shōhondō at Taisekiji.

1999 (October 5): Kōmeitō, now New Kōmeitō after decades of political transformations, entered into coalition with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Kōmeitō remained allied with the LDP in government until 2009, and the LDP-Kōmeitō coalition was reelected to government in December, 2012.

2001 (May 3): Soka University of America opened in Aliso Viejo, California.

2002 (April): Sōka Gakkai issued new institutional regulations.

2006 (November 9): Harada Minoru was appointed sixth Sōka Gakkai president.

2011 (March): In the wake of the March 11 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disasters that devastated northeastern Japan, Sōka Gakkai housed in excess of 5,000 refugees in Culture Centers across the region, gathered hundreds of millions of yen in emergency aid, and mobilized thousands of volunteers from across Japan to take part in both short- and long-term rescue and relief initiatives.

2013 (November 18): Sōka Gakkai officially opened its new General Headquarters at Shinanomachi, Tokyo. The organization now claims 8.27 million member households, and Soka Gakkai International claims in excess of 1.5 million members in 192 countries outside Japan.

2023 (November 15): Ikeda Daisaku died.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Sōka Gakkai can be described as Japan’s most successful new religious movement. The group claims 8.27 million adherent households in Japan, and more than 1.5 million members in 192 other countries under its overseas umbrella organization Soka Gakkai International, or SGI. These numbers are inflated, but statistical surveys conducted over the past few decades indicate that between roughly two and three percent of the Japanese population self-identifies as belonging to Sōka Gakkai (McLaughlin 2009; Roemer 2009). This makes the organization the largest active religious group in the country. No temple-based Buddhist group, Shintō organization, or other new religious group matches Sōka Gakkai’s ability to mobilize adherents for the sake of proselytizing, electioneering, and other activities.

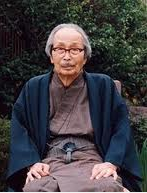

Sōka Gakkai’s history distinguishes it from many Japanese new religious movements. First, as its name Sōka Gakkai, or “Value Creation Study Association” suggests, the group did not begin as a religion, but was founded as an educational reform association. Second, Sōka Gakkai in effect had three separate foundings, one each under its first three presidents: Makiguchi Tsunesaburō (1871-1944), Toda Jōsei (1900-1944), and Ikeda Daisaku (1928-2023). Each of these founders oversaw a new era of institutional changes.

Sōka Gakkai claims its founding moment as November 18, 1930, when its first president Makiguchi Tsunesaburō published the first volume of his collected essays, System of Value-Creating Educational Study ( Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ), marking the start of the Value Creation Education Study Association (Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai), Sōka Gakkai’s predecessor. Makiguchi was born in 1871 in what is now Niigata Prefecture in northeastern Japan, but he moved to the northern island of Hokkaido at the age of thirteen, where he was raised and eventually educated as an elementary school teacher. In 1901, he moved with his wife and children from the Hokkaido city of Sapporo to Tokyo, where he embarked on a career teaching at a series of Tokyo elementary schools. He also collaborated with intellectuals concerned with educational reform as he published books and essays. From 1910, Makiguchi joined the Kyōdokai, or Home Town Association, a research group engaged in ethnology and surveys of local culture in rural areas; the group included the famed folklorist Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) and internationally renowned educator Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933). Thanks to scholarly engagements in these circles and through his own research, Makiguchi’s ideas were influenced by educational and philosophical trends, including neo-Kantian thought and pragmatism, which moved from Europe and the United States into Japan around the turn of the twentieth century.

volume of his collected essays, System of Value-Creating Educational Study ( Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ), marking the start of the Value Creation Education Study Association (Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai), Sōka Gakkai’s predecessor. Makiguchi was born in 1871 in what is now Niigata Prefecture in northeastern Japan, but he moved to the northern island of Hokkaido at the age of thirteen, where he was raised and eventually educated as an elementary school teacher. In 1901, he moved with his wife and children from the Hokkaido city of Sapporo to Tokyo, where he embarked on a career teaching at a series of Tokyo elementary schools. He also collaborated with intellectuals concerned with educational reform as he published books and essays. From 1910, Makiguchi joined the Kyōdokai, or Home Town Association, a research group engaged in ethnology and surveys of local culture in rural areas; the group included the famed folklorist Yanagita Kunio (1875-1962) and internationally renowned educator Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933). Thanks to scholarly engagements in these circles and through his own research, Makiguchi’s ideas were influenced by educational and philosophical trends, including neo-Kantian thought and pragmatism, which moved from Europe and the United States into Japan around the turn of the twentieth century.

On November 18, 1930, Makiguchi published Volume One of System of Value-Creating Educational Study ( Sōka kyōikugaku taikei ). When Makiguchi compiled his essays on educational reform in this volume, he was beginning of process of summarizing a lifetime of scholarship, and his interests after this moved in the direction of religion. In 1928, Makiguchi converted to Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism. Nichiren Shōshū, or “Nichiren True Sect,” follows the teachings of Nichiren (1222-1282), a medieval Buddhist reformer. Trained primarily in the Tendai tradition, Nichiren broke away from established temples to preach that only faith in the Lotus Sūtra , held to be the historical Buddha Śākyamuni’s final teaching, and the practice of chanting the title of the Lotus in the seven-syllable formula namu-myōhō-renge-kyō were effective means of achieving salvation in the degraded Latter Days of the Buddha’s Dharma ( mappō ) (see below).

In 1932, Makiguchi retired from schoolteaching, and he turned thereafter toward concentrated study and practice of Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism. Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai began to meet formally from 1937, and by the 1940s Makiguchi and the organization he established, which claimed approximately five thousand members at its peak, were firmly committed to defending Nichiren Buddhist principles. From 1941, Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai launched a periodical titled Value Creation (Kachi sōzō). This short-lived magazine featured several articles by Makiguchi in which he directly challenged the Japanese government’s religious policies. The Japanese government ended Kachi sōzō ‘s publication at its ninth issue; Makiguchi remonstrated the government for its decision in a short article titled “An Address on the Discontinuation of Publication.”

On June 27, 1943, Makiguchi and other Gakkai leaders were summoned by the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood to the sect’s headquarters at the temple Taisekiji. They were urged to abide by the dictates of the Religious Corporations Law and Japan’s wartime State Shintō injunctions by instructing Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai adherents to enshrine talismans ( kamifuda ) from the Grand Shrine at Ise, despite the fact that the practice constituted a violation of Nichiren Buddhism. Makiguchi refused to do so. On July 6, Makiguchi, his disciple Toda, and nineteen other Gakkai leaders were arrested on charges of violating the Peace Preservation Law. They were charged with violating the Peace Preservation Law and imprisoned thereafter at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. Makiguchi died of malnutrition on November 18, 1944.

Makiguchi’s disciple Toda Jōsei was, like his mentor, born in northern Japan, raised in poverty in the northern island of Hokkaidō,  and made his way to the imperial capital to pursue his fortunes in teaching. Even after he left the teaching profession in late 1922, Toda remained beholden to his mentor Makiguchi, and he attributed his subsequent success in business to Makiguchi’s teachings. Toda alone demonstrated absolute commitment to Makiguchi by refusing to bow to the Japanese state’s pressure to recant his Nichiren Shōshū beliefs. While in prison, Toda experienced a vision in which he joined the innumerable Bodhisattvas of the Earth ( jiyu no bosatsu ) at Vulture Peak where the Buddha Śākyamuni delivers the Lotus Sūtra . He interpreted this revelation as an awakening to the sacred task of continuing his master Makiguchi’s mission to propagate Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism.

and made his way to the imperial capital to pursue his fortunes in teaching. Even after he left the teaching profession in late 1922, Toda remained beholden to his mentor Makiguchi, and he attributed his subsequent success in business to Makiguchi’s teachings. Toda alone demonstrated absolute commitment to Makiguchi by refusing to bow to the Japanese state’s pressure to recant his Nichiren Shōshū beliefs. While in prison, Toda experienced a vision in which he joined the innumerable Bodhisattvas of the Earth ( jiyu no bosatsu ) at Vulture Peak where the Buddha Śākyamuni delivers the Lotus Sūtra . He interpreted this revelation as an awakening to the sacred task of continuing his master Makiguchi’s mission to propagate Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism.

After his release from prison in July, 1945, weeks before the end of the Second World War, Toda devoted himself to resuming Makiguchi’s religious mission. He is responsible for transforming the group from a small collective into a religious mass movement. In 1946, he dropped “education” (kyōiku) from the title, changing the group’s name to Sōka Gakkai. The reformed group met initially on the second floor of Toda’s publishing and distance education company Nihon Shōgakkan. On May 1, 1946, Toda was appointed general director of Sōka Gakkai. As he continued launching business ventures, he began holding regular Gakkai study meetings (called zadankai , or “study roundtables”) and organizing a growing number of new converts under the group’s developing administrative leadership. Japan’s tumultuous economy created trouble for Toda’s businesses, and on November 12, 1950, Toda resigned as Sōka Gakkai’s general director, citing his business failures as proof of retribution for failing to commit fully to rebuilding his mentor Makiguchi’s organization. The group, which had experienced slow but steady growth to this point, began to organize for the purpose of radical expansion.

On May 3, 1951, Toda accepted appointment as second president of Sōka Gakkai. At his inauguration, Toda challenged the Gakkai’s adherents to convert seven hundred and fifty thousand families to Sōka Gakkai before his death: “If this goal is not realized while I am alive,” he declared, “do not hold a funeral for me. Simply dump my remains in the bay at Shinagawa.” The group soon developed a widely publicized reputation for aggressive proselytizing and harsh condemnation of rival religions. These tactics met with success: from 1951, Sōka Gakkai grew from a few thousand members to claim over one million adherent households by the end of the decade. The majority of the people who joined the group in the immediate postwar years were some of the millions who were flooding Japan’s cities seeking material security, social infrastructure, and spiritual certainty. Toda relied upon the organization’s structure as a study association (gakkai) to school converts in Nichiren Buddhist doctrine and attract disenfranchised people to Sōka Gakkai’s legitimizing framework of standardized education. He also relied upon the group’s original emphasis on pragmatic thought to emphasize practical benefits. Toda likened Nichiren’s main object of worship to a “happiness-producing machine” that provides its user endless possibilities, and he organized converts into efficient cadres that relentlessly employed persuasive tactics to combat “false sects” (rival religions) in their conversion efforts. Converts enjoyed a renewed sense of self-worth as they were given the task of not only mastering command of Nichiren Buddhist doctrine but also of teaching it to others. Members combined their study of Nichiren and the Lotus with discussions of value, ethics, and pragmatic evaluation that Toda derived from Makiguchi as well as the canon of modern philosophy and world literature.

Sōka Gakkai’s hard-sell approach brought it a rush of new converts, but its aggressive approach also earned the group a negative public image, particularly in the wake of several scandals. One of the most notorious events came to be known as the “Ogasawara Incident” or “Tanuki (Racoon Dog) Festival.” On April 27, 1952, during rituals marking the seven hundredth anniversary of Nichiren’s first chanting of namu-myōhō-renge-kyō, a group of Young Men’s Division members on a pilgrimage to the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji seized a Shōshū priest named Ogasawara Jimon. Ogasawara had promoted a controversial plan during the wartime era (one opposed by Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai and the Shōshū leadership) to amalgamate all Nichiren sects into one nation-promoting denomination. He was accused by Toda and the Gakkai youth members of alerting wartime authorities to Makiguchi’s refusal to follow State Shintō protocol, and was blamed for the arrest of the Gakkai leaders and the resulting death of Makiguchi. The Gakkai youth stripped Ogasawara of his robes, paraded him around the Taisekiji grounds, hung a placard from his neck bearing the phrase “tanuki monk” (associating him with the tanuki, an animal that appears in Japanese folk tradition as a shape-changing trickster), and brought him to Makiguchi’s grave, where he was forced to sign a prepared written apology. Reports of this incident in the popular press created a negative public image for Sōka Gakkai, an image that came to permanently define public opinion about the organization in Japan.

Sōka Gakkai’s reputation for aggressive behavior was amplified after another controversial event known as the “Otaru Debate,” when members of Sōka Gakkai’s Study Department challenged priests from the Minobu Sect of Nichiren Buddhism to a doctrinal debate. The event was held in a hall in the city of Otaru (Hokkaido) that was packed with Gakkai members, who jeered at the priests and accused them of heterodox worship and financial corruption. The priests withdrew, and Sōka Gakkai declared themselves the debate’s winners. Publications critical of Sōka Gakkai by the Nichiren sect and other religious organizations began to emerge in large numbers from around this time.

Despite growing controversy about its tactics, Sōka Gakkai continued unflagging growth. From 1953, Sōka Gakkai began holding written and oral “appointment examinations” (nin’yō shiken) to test youth leaders on Nichiren Buddhist doctrinal knowledge. The Gakkai’s administration across Japan expanded rapidly from around this time. With administrative expansion came expansion outside lay Buddhist practices. On May 9, 1954, the Gakkai’s Young Men’s Division leader Ikeda Daisaku (1928-2023) founded the Gungakutai (Military Band Corps), predecessor of the present-day Music Corps (Ongakutai), establishing an interest in the arts that the organization would deepen in later years. The Gungakutai played its first concert in the rain at Taisekiji on October 31, 1954, when Toda reviewed ten thousand mustered Young Men’s and Young Women’s Division members while he rode a white horse, an act viewed by critics outside the group as emulating the wartime Japanese emperor.

The Gakkai’s most notable growth beyond its lay Buddhist focus was expansion into electoral politics. From November 1954, Sōka Gakkai established a Culture Division (Bunkabu), a sub-organization dedicated primarily to selecting candidates to run in elections and to mobilizing members to gather votes. On April 3, 1955, members of Sōka Gakkai’s Culture Division won election in city councils in Tokyo wards and in other municipalities; this marked the first time Sōka Gakkai ran its own candidates for office. On August 1, 1956, Toda issued an essay titled “On the Harmonious Union of Government and Buddhism” (Ōbutsu myōgō ron) in the Gakkai study magazine Great White Lotus (Daibyaku renge), in which he stated that “the only purpose of our going into politics is the erection of the national ordination platform (kokuritsu kaidan).” Expressions of alarm regarding Sōka Gakkai’s forays into national-level politics became a media staple in Japan from around this time.

Sōka Gakkai’s initial forays into politics met with conflict. On April 23, 1957, a group of Young Men’s Division members campaigning for a Gakkai candidate in an Osaka Upper House by-election were arrested for distributing money, cigarettes, and caramels at supporters’ residences, in violation of elections law, and on July 3 of that year, at the beginning of an event memorialized as the “Osaka Incident,” Ikeda Daisaku was arrested in Osaka. He was taken into custody in his capacity as Sōka Gakkai’s Youth Division Chief of Staff for overseeing activities that constituted violations of elections law. He spent two weeks in jail and appeared in court forty-eight times before he was cleared of all charges in January 1962. Sōka Gakkai characterized this incident as Ikeda’s triumph over corrupt tyranny, and the trial of the young leader galvanized Sōka Gakkai members to greater efforts in proselytizing and electioneering.

By the time Toda Jōsei died in April 1958, Sōka Gakkai claimed in excess of one million adherent households, and its size and political clout compelled displays of respect, even from its rivals. An estimated 250,000 Gakkai members lined Tokyo streets to view Toda’s hearse passing to his official funeral on April 20, 1957, where Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke and Minister of Education Matsunaga Tō offered incense to the deceased leader.

After Toda’s disciple Ikeda Daisaku took the post of third Sōka Gakkai president in May, 1960, he set about expanding the group  from a Japan-focused lay Buddhist organization into an international enterprise with a broad mandate in religion, politics, and culture. Under Ikeda’s leadership, Sōka Gakkai established official branches in Asia, Europe, North America, Brazil, and other parts of the globe. Under Ikeda, Sōka Gakkai founded its own accredited private school system, sub-organizations committed to supporting the arts, and other education- and culture-focused initiatives.

from a Japan-focused lay Buddhist organization into an international enterprise with a broad mandate in religion, politics, and culture. Under Ikeda’s leadership, Sōka Gakkai established official branches in Asia, Europe, North America, Brazil, and other parts of the globe. Under Ikeda, Sōka Gakkai founded its own accredited private school system, sub-organizations committed to supporting the arts, and other education- and culture-focused initiatives.

Sōka Gakkai continued radical growth in Japan under Ikeda’s leadership throughout the 1960s, powered by the organization’s mobilization in electoral politics through its party Kōmeitō (founded 1964) and a related focus on the goal of building a “national ordination platform” (kokuritsu kaidan). This platform, a special temple facility for ordinations, was to be erected by government decree to mark the completion of kōsen rufu , interpreted by Sōka Gakkai by this time to mean the conversion of one third of the population of Japan. From late 1965, the Gakkai membership focused on the project of constructing the Shōhondō, a massive facility at the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji to house the daigohonzon , the calligraphic mandala inscribed by Nichiren in 1279 that serves Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū as their primary object of worship. The Shōhondō was referred to until the end of the decade by Shōshū and Gakkai leaders as a virtual realization of the “true ordination platform” (the honmon no kaidan), marking the completed task of converting the populace.

facility at the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji to house the daigohonzon , the calligraphic mandala inscribed by Nichiren in 1279 that serves Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū as their primary object of worship. The Shōhondō was referred to until the end of the decade by Shōshū and Gakkai leaders as a virtual realization of the “true ordination platform” (the honmon no kaidan), marking the completed task of converting the populace.

Growth stalled at the end of the 1960s, at a point when Sōka Gakkai and Kōmeitō were compelled to officially separate. This official split followed a scandal that began in November, 1969 over events that came to be known as the “problem over obstructing freedom of expression and the press” (genron shuppan bōgai mondai ). Fujiwara Hirotatsu (1921-1999), a Meiji University professor, published a book titled I Denounce Sōka Gakkai ( Sōka gakkai o kiru ). He claimed that attempts were made by prominent Kōmeitō politicians and Liberal Democratic Party Secretary General Tanaka Kakuei (1918-1993, later Prime Minister) to block publication. Press coverage of this scandal encouraged sales of Sōka gakkai o kiru and a flood of negative press for Sōka Gakkai.

In the wake of the I Denounce Sōka Gakkai scandal, Ikeda Daisaku announced the official separation of Sōka Gakkai and Kōmeitō  and a new Gakkai policy of “separation of politics and religion” (seikyō bunri ). The official separation of the religion and the political party served as a watershed moment for both organizations: Sōka Gakkai’s membership only grew by small amounts after this, and Kōmeitō suffered electoral losses throughout the following decade. Even after the official separation, devout Gakkai adherents have continued to regard electioneering on behalf of Kōmeitō candidates as part of their regular faith activities.

and a new Gakkai policy of “separation of politics and religion” (seikyō bunri ). The official separation of the religion and the political party served as a watershed moment for both organizations: Sōka Gakkai’s membership only grew by small amounts after this, and Kōmeitō suffered electoral losses throughout the following decade. Even after the official separation, devout Gakkai adherents have continued to regard electioneering on behalf of Kōmeitō candidates as part of their regular faith activities.

From the early 1970s, Sōka Gakkai moved away from its mission of aggressive expansion in favor of cultivating the generation of children born to first generation converts in discipleship under Ikeda Daisaku. On October 12, 1972, during ceremonies marking the opening of the completed Shōhondō at Taisekiji, Ikeda delivered a speech announcing the start of Sōka Gakkai’s “Phase Two,” describing a turn away from aggressive expansion toward envisioning the Gakkai as an international movement promoting peace through friendship and cultural exchange.

Sōka Gakkai’s official announcement of an inward turn did not deter critiques from outside the group. From March 1976, the tabloid Monthy Pen (Gekkan pen) began publishing a series of articles alleging liaisons between Ikeda and six women, including top Women’s Division leaders. Sōka Gakkai sued for defamation, and the Tokyo District Court ruled in its favor; Gekkan pen was forced to issue a published apology, and its publisher Kumabe Taizō served one year on probation. A recurring pattern of tabloid accusation followed by Gakkai lawsuit became an entrenched feature from this point, causing further damage to Sōka Gakkai’s public image, and the “women problem” (josei mondai) remained an angle of attack that journalists have continued to employ against Ikeda to the present.

From 1977, Ikeda began to clash openly with the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood. At several points during this year Ikeda delivered speeches and published essays in which he challenged the authority of the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood. In one of these, an essay titled “Lecture on the Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life” (Shōji ichidaiji ketsumyakushō kōgi) that Sōka Gakkai reprinted in millions of pamphlets, Ikeda contended that Shōshū priestly claims to an exclusive lineage going back to the founder Nichiren were not superior to links Gakkai members forge to the Dharma by chanting namu-myōhō-renge-kyō. Extensive negotiations between the two organizations led to Sōka Gakkai reaffirming Nichiren Shōshū priestly lineage claims, and in 1979 Ikeda was compelled to step down from the post of third Gakkai president to take the position of Honorary President.

Distance between Sōka Gakkai and Nichiren Shōshū continued to widen throughout the 1980s, and by the middle of that decade the Shōshū priesthood found itself the uncomfortable elderly companion of a dynamic international organization led by a public intellectual who was more likely to speak of the Enlightenment of European philosophy than the enlightenment promised by Nichiren Buddhist doctrine. These years saw Sōka Gakkai grow increasingly internationally focused; concerned with world peace, culture, and education; centered on Ikeda’s authority; and distant from its Nichiren Shōshū parent organization.

In 1990, the second major conflict between Ikeda Daisaku and the Nichiren Shōshū priesthood erupted. Open acrimony between the Shōshū priesthood and the Sōka Gakkai leadership escalated through a series of missives between the two camps. The priesthood complained about speeches made by Ikeda in which he criticized Abe Nikken. Sōka Gakkai responded with lists of their own concerns about the treatment of their members by the priesthood. From early 1991, Sōka Gakkai began publishing articles in the Seikyō shinbun that were openly critical of Abe Nikken, and the organization began promoting funerals conducted by Gakkai leaders without Nichiren Shōshū priests. Tensions between the two leaderships reached a breaking point by the end of November, 1991 when Nichiren Shōshū excommunicated Sōka Gakkai; in one day, the sect expelled more than ninety-five percent of its parishioners.

Prevented from engaging directly with its principal object of worship enshrined at the Shōshū head temple, Sōka Gakkai after 1991 confirmed its identity as an organization committed entirely to Ikeda. In April, 2002, Sōka Gakkai issued new institutional regulations stipulating that Makiguchi, Toda, and Ikeda are to be known as the sandai kaichō (three generations of presidents), the “eternal mentors” ( eien no shidōsha ) who founded the movement; that the organization upholds the principle of shitei funi (the “indivisible bond of mentor and disciple”); and that the post of Sōka Gakkai president is purely administrative. Sōka Gakkai definitively curtailed the possibility of extending charismatic leadership past Ikeda Daisaku.

In recent years, Gakkai members have mostly come to learn about Nichiren Buddhism in the context of Ikeda’s writings, and dedicated adherents structure their lives around a busy calendar of large and small Gakkai events that serve as rededications of their discipleship under the Honorary President.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Sōka Gakkai is commonly characterized as a lay movement within Nichiren Shōshū Buddhist tradition. However, as the history outlined above indicates, it is much more than a Buddhist organization and is instead best understood as heir to twin legacies: (1) a tradition of self-cultivation through the practice of Nichiren Shōshū Buddhism, and (2) intellectual currents that flourished in late nineteenth to early twentieth century Japan valorizing education, pedagogy, and humanism, inspired by modern Euro-American philosophy and traditions that fall under the general rubric of “culture.” These two legacies shape the commitments, expressive idioms, and combination of doctrines and practices Sōka Gakkai members uphold.

Members maintain traditional Buddhist practices in keeping with Nichiren Shōshū tradition. These include:

Chanting. Members intone morning and evening prayers in front of their home altars in a chanting performance called gongyō, literally “to exert oneself in practice.” The twice-daily chant includes Chapter Two, “Expedient Means” (Hōben), and sections of Chapter Sixteen, “Life Span” (Juryō), of the Lotus Sūtra. The sūtra sections are followed by repeated incantations of the title of the Lotus, called the daimoku, which consists of the seven syllables namu-myōhō-renge-kyō, and by silent prayers.

Reverence for the daigohonzon . This is the “great object of worship,” a calligraphic mandala said to have been inscribed by Nichiren on the twelfth day of the tenth month of 1279 for the sake of all humanity. Membership in Sōka Gakkai is confirmed by the reception of a gohonzon , a replica of the daigohonzon . Sōka Gakkai’s lack of access to the daigohonzon after November 1991 and the group’s practice since then of manufacturing gohonzon based on a replica produced in 1720 contribute to ongoing heated doctrinal controversies between the Gakkai and rival Nichiren groups, particularly Nichiren Shōshū and the Shōshū-based lay organization Fuji Taisekiji Kenshōkai.

Conversion activities known as shakubuku. Shakubuku can be translated as “break and subdue [attachment to inferior teachings].” It was promoted by Nichiren as the only practice appropriate for countries, such as Japan, that slander the dharma. Recent decades have seen Sōka Gakkai, especially its international wing SGI, encourage a move away from shakubuku in favor of shōju , the proselytizing method promoted in the Nichiren tradition of gentle suasion through reasoned argument. However, ordinary members in Japan rarely speak of converting others to Sōka Gakkai in anything other than terms of shakubuku , although interpretations of that term have mostly shifted from hard-sell tactics in the early postwar decades to less intense methods in recent years.

The mission of kōsen rufu , which calls for the spread of the Lotus in the time of mappō, the latter day of the Buddha’s Dharma. The term, which can be translated as “widely declare and spread [the truth of the Lotus Sūtra ],” is employed within Sōka Gakkai as a means of describing any activities that promote the growth of the institution.

Belief that the present age is the latter days of the Buddha’s Dharma (mappō). The three stages of history in East Asian Buddhist tradition are the age of shōbō , or “true Dharma”; the age of zōhō , or “semblance Dharma”; and the final age of mappō , understood to have begun in the year 1052. Sōka Gakkai members uphold Nichiren’s belief that the only means of salvation in mappō is to embrace the Lotus Sūtra and reject all other teachings as false (Stone 1999:383-84).

Reverence for Nichiren and his writings. Followers in the Nichiren Shōshū tradition, including members of Sōka Gakkai, regard Nichiren as the earthly avatar of the eternal or original Buddha. As such, his writings are considered by Gakkai followers to bear scriptural authority surpassing even that of the sūtra s of the Buddha Śākyamuni.

Nichiren as the earthly avatar of the eternal or original Buddha. As such, his writings are considered by Gakkai followers to bear scriptural authority surpassing even that of the sūtra s of the Buddha Śākyamuni.

Though focus on this matter has diminished considerably within Sōka Gakkai since 1970, the group was greatly concerned with realizing the final of Nichiren’s Three Great Secret Dharmas (sandai hihō). These are (1) the honmon no daimoku , the title of the Lotus , namu-myōhō-renge-kyō ; (2) the honmon no honzon, or true object of worship, the calligraphic mandala with the daimoku inscribed at its center that Nichiren devised for his followers; and (3) the honmon no kaidan, or “true ordination platform,” a site for the ordination of clerics that would become the spiritual center for all people, marking the achievement of kōsen rufu , or the conversion of all people to exclusive worship of the Lotus . The first two of the Three Great Secret Dharmas were achieved by Nichiren himself, and the third remained a lofty and remote goal for Nichiren’s followers for centuries, that is, until Sōka Gakkai began to attract millions of converts in the years after the Second World War. Toda Jōsei moved Sōka Gakkai into electoral politics in the 1950s for the sake of realizing the third of the Three Great Secret Dharmas: securing state support for the construction of the honmon no kaidan, known in the modern era as the kokuritsu kaidan, or “national ordination platform,” was required, according to Nichiren Buddhist decree. Sōka Gakkai abandoned the kokuritsu kaidan objective after it separated officially from its political party Kōmeitō in 1970.

Though Nichiren Buddhism forms the core of Sōka Gakkai’s identity as a lay organization, the group’s founding as an educational reform movement concerned with pedagogy and culture guides the ethos and activities of members. In particular, members today define themselves as Gakkai adherents in terms of discipleship under Honorary President Ikeda Daisaku. They conceive of their practice as operating within an affective one-to-one relationship with Ikeda, and though they rarely meet with him directly, they constantly encourage one another to forge an “indivisible bond of mentor and disciple” (shitei funi) by formulating all of their personal objectives and accomplishments as dedications to the Honorary President.

Members are cultivated in reverence for Ikeda through constant immersion in Gakkai media. Maximally dedicated Gakkai members can receive most or even all of their information through the organization. Information is obtained through meetings and satellite broadcasts they attend at Culture Centers and through the daily newspaper Seikyō shinbun , the study magazine Daibyaku renge , videos produced by the production company Shinano Kikaku, and thousands of books, magazines, CDs, websites, and other sources. Today, members are most likely to encounter Nichiren’s writings and the Lotus Sūtra through transcribed speeches and essays by Ikeda. Culture Centers are decorated with Ikeda’s photographs and images of the historical figures he finds most inspiring; typically, apart from altars that enshrine the gohonzon , there is nothing traditionally “Buddhist” or even Japanese to be seen in a Gakkai building. Ikeda extols Napoleon, Ludwig van Beethoven, Martin Luther King Jr., the Mahātmā Gandhi, and other historical greats known for having realized their transcendent visions in the face of adversity. Members are inspired to model their own lives on the examples of these heroic figures, and constant immersion in Gakkai media encourages them to conflate the biographies of triumphant historical personages with that of Ikeda. Reverence for Ikeda is also cultivated by reading books authored by him, particularly The Human Revolution (Ningen kakumei) and its sequel The New Human Revolution (Shin ningen kakumei), serial novelized histories of Sōka Gakkai and its founding presidents that members regard as possessing de facto scriptural authority.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

In addition to twice-daily recitation of sections of the Lotus Sūtra and repetitions of namu-myōhō-renge-kyō , Gakkai members  engage in numerous other activities that make up ritual life in the group. These include:

engage in numerous other activities that make up ritual life in the group. These include:

Study meetings: Local Gakkai members meet at member homes not for Buddhist study per se but at zadankai , monthly “discussion meetings” or “study roundtables.” Members otherwise gather at Culture Centers for larger meetings and to attend broadcasts that include speeches by Honorary President Ikeda. Members will also attend many other meetings convened for the Gakkai sub-organizations to which they belong, such as the Married Women’s Division or the Young Men’s Division, and vocational groups such as the Doctor’s Division, the Educator’s Division, the Artist’s Division, or others.

Gathering subscriptions for Gakkai publications: Sōka Gakkai members regularly solicit friends, relatives, acquaintances, and each other to sign up to receive periodicals such as the newspaper Seikyō shinbun . The group calls the practice of soliciting for its newspaper “newspaper enlightenment” (shinbun keimō) or using the European (not the Buddhist) term for “enlightenment” ( keimō ) to celebrate the awakening of new readers.

Political campaigns: A major component of devoted members’ practice is electioneering on behalf of candidates for Kōmeitō or, on occasion, for its coalition partner the Liberal Democratic Party. Sōka Gakkai maintains Japan’s most powerful grassroots-level electioneering network, powered primarily by its Married Women’s Division, who gather votes for candidates in every election, from local town councils to races for seats in the National Diet. Though Sōka Gakkai and Kōmeitō are formally separate, most committed members regard campaigning for Kōmeitō as part of their faith-driven activities.

Visits to important Gakkai sites: Since 1991, when they were barred from pilgrimages to the daigohonzon at the Nichiren Shōshū head temple Taisekiji in Shizuoka Prefecture, members have taken to carrying out pilgrimages to places associated with the person of Ikeda Daisaku. These include the Sōka Gakkai administrative headquarters at Shinanomachi in central Tokyo, the tree-lined campus of Sōka University in Hachiōji, and the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum. Particularly committed adherents will make annual visits on significant dates in Ikeda’s biography, such as his birthday on January 2, and his date of conversion to Sōka Gakkai on August 24. These annual observances have come to replace the nenchū gyōji, or the “cycle of annual practices” maintained by the Gakkai’s temple-based Buddhist parent Nichiren Shōshū.

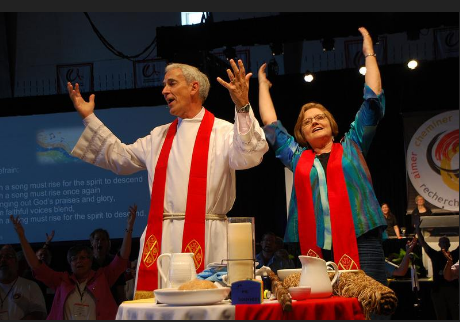

Cultural engagement: From the late 1950s, Gakkai members began to perform at mass events held in sports arenas, and from the 1960s into the early 2000s Culture Festivals (bunkasai) featuring thousands of ordinary members engaged in cast-of-thousands musical spectaculars were organized with some regularity. The last two decades has seen a decline in these mass events in favor of members attending exhibitions at Culture Centers, visiting the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, and patronizing performances sponsored by the Min-on Concert Association. Young members also perform (primarily) Western classical music in orchestras, concert bands, and other ensembles administered by the Young Men’s Division Music Corps (Ongakutai) and the Young Women’s Division Fife-and-Drum Corps (Kotekitai).

Ritual reception of a gohonzon : In contrast to earlier eras, when converts were urged to convert to Sōka Gakkai immediately, aspiring members are now encouraged to practice gongyō for six months before they receive their own gohonzon replica in a ceremony called gojukai, to “take the precepts,” or uphold exclusive reverence for the gohonzon .

Funerals and memorials: Since 1991, members have been encouraged to have “friend funerals”( yūjinsō ) conducted by Gakkai administrators from the Liturgy Division (Gitenbu) who perform gongyō for the deceased and carry out other funerary duties formerly performed by Nichiren Shōshū priests.

Regardless of the nature of the Gakkai meeting, the beginnings and endings of small and large gatherings in the presence of an enshrined gohonzon are routinely marked by reciting the daimoku sanshō : three invocations of namu-myōhō-renge-kyō.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Sōka Gakkai maintains an elaborate bureaucratic administration that resembles that of a modern national government and its civil service. Honorary President Ikeda floats above a massive pyramidal structure topped by a president (currently sixth president Harada Minoru) who oversees more than five hundred vice-presidents, a board of regents, and many other paid administrators who in turn oversee the activities of the Gakkai’s many subdivisions. Members are grouped by age, marital status, gender, location, occupation, and many other demographic considerations. The primary sub-organizations are the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Divisions, the Married Women’s Division, and the Men’s Division. Children under the age of eighteen belong to the Future Division. Members across Japan belong to a vertical administrative hierarchy based in households (setai) that are organized into blocks (burokku), districts (chiku), chapters (shibu), regional headquarters (honbu), wards (ku or ken), and prefectures (ken), which are in turn administered by thirteen national districts; almost all of the administrative work ensuring the daily operation of these subdivisions is carried out by volunteer administrators. One active member may hold multiple volunteer administrative posts at different levels of the organization, from the block on upward, and each of these positions will entail numerous responsibilities. The most active members at the local level belong to the Married Women’s Division, and though the majority of regular attendees at meetings are women, membership in Sōka Gakkai’s administration, with the exception of the Future, Young Women’s, and Married Women’s Divisions, is restricted to men.

service. Honorary President Ikeda floats above a massive pyramidal structure topped by a president (currently sixth president Harada Minoru) who oversees more than five hundred vice-presidents, a board of regents, and many other paid administrators who in turn oversee the activities of the Gakkai’s many subdivisions. Members are grouped by age, marital status, gender, location, occupation, and many other demographic considerations. The primary sub-organizations are the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Divisions, the Married Women’s Division, and the Men’s Division. Children under the age of eighteen belong to the Future Division. Members across Japan belong to a vertical administrative hierarchy based in households (setai) that are organized into blocks (burokku), districts (chiku), chapters (shibu), regional headquarters (honbu), wards (ku or ken), and prefectures (ken), which are in turn administered by thirteen national districts; almost all of the administrative work ensuring the daily operation of these subdivisions is carried out by volunteer administrators. One active member may hold multiple volunteer administrative posts at different levels of the organization, from the block on upward, and each of these positions will entail numerous responsibilities. The most active members at the local level belong to the Married Women’s Division, and though the majority of regular attendees at meetings are women, membership in Sōka Gakkai’s administration, with the exception of the Future, Young Women’s, and Married Women’s Divisions, is restricted to men.

In addition to a modern rationalized bureaucracy overseen by a presidency, Sōka Gakkai maintains other administrative features that mirror the appurtenances of a nation-state. These include:

A Sōka Gakkai flag: A red, yellow, and blue tri-color modeled on European national flags that frequently features a lotus flower  drawn at the center. Gakkai territory is instantly recognizable in Japan when the flag hangs over a building, a member’s home, or a business run by an adherent.

drawn at the center. Gakkai territory is instantly recognizable in Japan when the flag hangs over a building, a member’s home, or a business run by an adherent.

Anthems: Gakkai members learn Sōka Gakkai songs and sing them at meetings. The songs serve as rallying cries that bind members to the group’s institutional memory, and almost all of these are military marches written for optimal performance by singing in unison over brass band accompaniment.

A Sōka Gakkai economy: The organization maintains a thriving internal economy based primarily on zaimu (literally “finances”), or monetary donations from members. Sōka Gakkai depends financially on the flow of billions of yen and material goods provided as gifts by members to the institution.

A media empire: Members receive news about the group’s activities, doctrinal teachings, guidance from Ikeda, and other forms of information from the visual, audio, literary, and other forms of media issued by the organization. They are also bonded to Sōka Gakkai media through quotidian practices such as delivering newspapers, soliciting new subscriptions, and filling their shelves, screens, and stereos with Gakkai texts, images, and sounds.

Schools: Since 1968, the group has built a respected private secular educational system from preschool up to Sōka University, and in recent years has added educational institutions overseas. Graduates from Sōka Gakkai educational institutions maintain lifelong ties, and in recent decades the organization has staffed the ranks of its paid administrative staff with graduates from its own schools.

Sōka Gakkai territory: The organization maintains thousands of Culture Centers and other facilities across Japan that are patrolled by trained special cadres, usually the Gajōkai (Fortress Protection) and Sōkahan (Value Creation Team) sub-groups of the Young Men’s Division.

No matter their level of commitment to the group’s administration or the extent to which they devote themselves to life within the nation-like structure of the group, Gakkai members perceive themselves to be in an affective direct relationship with Ikeda Daisaku, a relationship that can at times circumvent Sōka Gakkai’s massive bureaucracy.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

As a vast, expansionist organization that came to dominate Japan’s religious landscape and make its presence felt in politics, education, publishing, and many other spheres, Sōka Gakkai has provoked many conflicts. Numbering among these are:

A reputation for aggressive proselytizing. Though the terms of shakubuku have changed considerably, from its interpretation under Toda as aggressive conversion of all to encouraging dialogue between friends today, Sōka Gakkai retains a reputation for intolerance of other faiths and requiring its members to proselytize.

Conflict with other religious organizations. Sōka Gakkai exploded to millions of exclusive adherents over a few short decades by converting followers of other religions. It was able to do this in part because of arguments it leveled against “false teachings” and what it regarded as heterodox forms of worship. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this approach led almost all other religious groups in Japan (including Buddhist organizations, Shintō-based groups, Christian denominations, and New Religions) to target Sōka Gakkai as their primary rival.

The most acute religious conflict Sōka Gakkai faces today is with Nichiren Shōshū. The years following the 1991 split have seen published accusations and hundreds of lawsuits define the relationship between the two organizations. Both groups have sought to purge themselves of each other’s influence; Nichiren Shōshū demolished the Shōhondō in 1998, and Sōka Gakkai denies the religious legitimacy of the Shōshū abbot. Sōka Gakkai’s Shōshū-connected rivals, including the lay group Fuji Taisekiji Kenshōkai, focus in particular on what they regard as the sacrilege of Gakkai members’ reverence for replicas made from the 1720 Nichikan transcription of the daigohonzon .

Political engagement. The Sōka Gakkai activity that attracts the majority of public opposition is its continuing support of Kōmeitō. Critics accuse Sōka Gakkai of violating Article 20 of the 1947 Japanese Constitution, which bars religious organizations from receiving privileges from the state or exercising political authority. During the 1950s and 60s, when Sōka Gakkai was pushing for the construction of the ordination platform by government decree, critics also accused the group of violating Article 89, which prevents the government from expending funds for the benefit of religious enterprises. Dropping the objective of constructing the ordination platform has made it easier for Sōka Gakkai to defend its position that supporting Kōmeitō does not violate the Constitution. Sōka Gakkai argues that it and its affiliated political party are officially separate organizations and reminds critics that the 1947 Constitution guarantees freedom of expression and freedom of assembly.

Reverence for Honorary President Ikeda. Outside observers note that Sōka Gakkai has transformed from an organization led by Ikeda to a group dedicated to Ikeda. The Gakkai’s Nichiren Buddhist practice is now framed as a means of refining the indivisible bond of mentor and disciple (shitei funi) encouraged within all its adherents. Critics employ the singular reverence Gakkai members maintain for their Honorary President as evidence that the group has moved away from its Nichiren Buddhist origins.

Sōka Gakkai faces a looming challenge occasioned by its singular focus on Ikeda Daisaku: when the Honorary President passes away, there will be no clear successor, and the organization’s bureaucrats may face difficulties exercising authority in the absence of a charismatic living leader.

As a result of these and other conflicts (see the timeline and founder/group history above), Sōka Gakkai has earned the most prominent and longest lasting negative public reputation of any religious group in contemporary Japan. Gakkai members live ordinary lives in mainstream Japanese society, yet many experience stigma in their schools, workplaces, and personal lives due to prevailing negative associations with their faith.

REFERENCES

Asahi Shinbun Aera Henshūbu, ed. 2011. Sōka gakkai kaibō. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbun.

Bessatsu Takarajima Henshūbu, ed. 2007. Ikeda Daisaku naki ato no Sōka gakkai. Tokyo: Takarajimasha.

Bethel, Dayle M. 1989. Education for Creative Living: Ideas and Proposals of Tsunesaburō Makiguchi. Translated by Alfred Birnbaum. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

Asano Hidemitsu. 1974. Watashi no mita sōka gakkai. Tokyo: Keizai Ōraisha.

Bessatsu Takarajima, ed. 1995. Tonari no sōka gakkai: uchigawa kara mita gakkai’in to iu shiawase. Tokyo: Takarajimasha.

Asano Hidemitsu. 1973. Makiguchi the Value Creator, Revolutionary Japanese Educator and Founder of Sōka Gakkai. New York: Weatherhill.

Ehrhardt, George, Axel Klein, Levi McLaughlin, and Steven Reed, eds. Forthcoming. Kōmeitō: Politics and Religion in Japan . Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies Japan Monograph Series.

Fisker-Nielsen, Anne Mette. 2012. Religion and Politics in Contemporary Japan: Soka Gakkai Youth and Komeito. London and New York: Routledge.

Fujiwara Hirotatsu. 1970. I Denounce Sōka Gakkai. Translated from the Japanese by Worth C. Grant. Tokyo: Nisshin Hōdō.

Fujiwara Hirotatsu . 1969. Kono nihon wo dō suru 2: sōka gakkai o kiru . Tokyo: Nisshin Hōdō Shuppanbu.

Higuma Takenori. 1970. Toda Jōsei / Sōka gakkai. Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha.

Higuma Takenori. 1983. Gendai shūkyōron. Tokyo: Shiraishi Shoten.

Ikeda Daisaku. 1998-2013. Ikeda Daisaku zenshū (130+ volumes). Tokyo: Seikyō Shinbunsha.

Ikeda Daisaku. 1998-2013. Shin ningen kakumei. Tokyo: Seikyō Shinbunsha (25 volumes).

Ikeda Daisaku. 1971-1994. Ningen kakumei. Tokyo: Seikyō bunko (12 volumes).

Inose Yūri. 2011. Shinkō wa dono yō ni keishō sareru ka: Sōka Gakkai ni miru jisedai ikusei. Sapporo: Hokkaidō Daigaku Shuppankai.

Itō Tatsunori. 2006 (March). “Kenkyū shiryō: sōka gakkai to nichirenshū no ‘otaru montō’ saigen kiroku.” Gendai Shūkyō Kenkyū 40:630-77.

Itō Tatsunori. 2004 (March). “ Shakubuku kyōten kōshō.” Gendai Shūkyō Kenkyū 38:251-75.

Itō Tatsunori. 2003 (March). “Kenkyū shiryō: kaisei sareta sōka gakkai kaisoku henkō sareta ‘Sōka gakkai’ kisoku.” Gendai Shūkyō Kenkyū 37:154-225.

Kumagai Kazunori. 1978. Makiguchi Tsunesaburō. Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha.

Machacek, David and Bryan Wilson, eds. 2000. Global Citizens: The Sōka Gakkai Buddhist Movement in the World . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Makiguchi Tsunesaburō. 1981-1987. Makiguchi Tsunesaburō zenshū (10 volumes). Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha.

McLaughlin, Levi. 2012. “Did Aum Change Everything? What Soka Gakkai Before, During, and After the Aum Shinrikyō Affair Tells Us About the Persistent ‘Otherness’ of New Religions in Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 39:51-75.

McLaughlin, Levi. 2012. “Sōka Gakkai in Japan.” Pp. 269-307 in Handbook of Contemporary Japanese Religion, edited by Inken Prohl and John Nelson. Leiden: Brill.

McLaughlin, Levi. 2009. “Sōka Gakkai in Japan.” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Religion, Princeton University.

Miyata Kōichi . 2000. Makiguchi Tsunesaburō: gokuchū no tatakai. Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha.

Miyata Kōichi . 1993 Makiguchi Tsunesaburō no shūkyō undō. Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha.

Murata, Kiyoaki. 1969. Japan’s New Buddhism: An Objective Account of Sōka Gakkai. New York: Walker / Weatherhill.

Nishino Tatsukichi. 1985. Denki Toda Jōsei. Tokyo: Daisan Bunmei.

Nishiyama Shigeru. 2004 (June). “Henbō suru sōka gakkai no konjaku.” Sekai :170-81.

Nishiyama Shigeru. 1998. “Naisei shūkyō no jiyūka to shūkyō yōshiki no kakushin: sengō dainiki no sōka gakkai no baai.” In Shūkyō to shakai seikatsu no shosō, edited by Numa Gishō hakushi koki kinen ronbunshū. Tokyo: Ryūbunkan.

Nishiyama Shigeru. 1989. “Seitōka no kiki to kyōgaku kakushin: ‘Shōhondō’ kansei ikō no ishiyama kyōgaku no baai.” Pp. 263-99 in Genkin Nihon bunka ni okeru dentō to henyō 5: genkin Nihon no “shinwa,” edited by Nakamaki Hirochika. Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan.

Nishiyama Shigeru. 1985. “Butsuryūkō to sōka gakkai ni miru kindai hokekei kyōdanhatten no nazo.” In Nichiren to hokekyō shinkō, edited by Tamura Yoshirō et.al. Tokyo: Yomiuri Shinbunsha.

Nishiyama Shigeru. 1975. “Nichiren shōshū sōka gakkai ni okeru ‘honmon kaidan’ ron no hensen: seijiteki shūkyō undō to shakai tōsei.” Pp. 241-75 in Nichirenshū no shomondai , edited by Nakao Takashi. Tokyo: Yūzankaku.

Roemer, Michael. 2009. “Religious Affiliation in Contemporary Japan: Untangling the Dilemma.” Review of Religious Research 50:298-320.

Saeki Yūtarō. 2000. Toda Jōsei to sono jidai . Tokyo: Mainichi Shinbunsha.

Shichiri Wajō. 2000. Ikeda Daisaku gensō no yabō: shōsetsu ningen kakumei hihan . Tokyo: Shin Nippon Shuppansha.

Shimada Hiromi. 2007. Kōmeitō vs. Sōka gakkai . Tokyo: Asahi Shinsho.

Shimada Hiromi. 2006. Sōka gakkai no jitsuryoku . Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha.

Shimada Hiromi. 2004. Sōka gakkai. Tokyo: Shinchō Shinsho.

Shimazono, Susumu. 2006. “Teikō no shūkyō / kyōryoku no shūkyō: senjiki sōka kyōiku gakkai no hen’yō.” Pp. 239-68 in Iwanami kōza ajia / taiheiyō sensō 6: nichijō seikatsu no naka no sōryokusen, edited by Kurazawa Aiko et. al. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Shimazono, Susumu. 2004. From Salvation to Spirituality: Popular Religious Movements in Modern Japan . Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Sōka Gakkai. 1952. Shinpen Nichiren Daishōnin gosho zenshū. Tokyo: Sōka Gakkai.

Sōka Gakkai Kyōgakubu, ed. 1951 to 1969. Shakubuku kyōten. Tokyo: Sōka Gakkai.

Sōka Gakkai Mondai Kenkyūkai, ed. 2001. Sōka gakkai fujinbu: saikyō shūhyō gundan no kaibō. Tokyo: Gogatsu Shobō.

Sōka Gakkai Nenpyō Hensan Iinkai, ed. 1976. Sōka gakkai nenpyō. Tokyo: Seikyō Shinbunsha.

Sōka Gakkai Yonjū Shūnenshi Hensan Iinkai, ed. 1970. Sōka gakkai yonjū shūnenshi. Tokyo: Sōka Gakkai.

Stone, Jacqueline I. 2003. “By Imperial Edict and Shogunal Decree: Politics and the Issue of the Ordination Platform in Modern Lay Nichiren Buddhism.” Pp. 192-219 in Buddhism in the Modern World: Adaptions of an Ancient Tradition, edited by Steven Heine and Charles Prebish. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stone, Jacqueline I. 2003. “Nichiren’s Activist Heirs: Sōka Gakkai, Risshō Kōseikai, Nipponzan Myōhōji.” Pp. 63-94. In Action Dharma: New Studies in Engaged Buddhism, edited by Christopher Queen, Charles Prebish and Damien Keown. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Stone, Jacqueline I. 1999. Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Stone, Jacqueline I. 1998. “Chanting the August Title of the Lotus Sūtra : Daimoku Practices in Classical and Medieval Japan.” Pp. 116-66 in Re-visioning “Kamakura” Buddhism, edited by Richard Payne. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Stone, Jacqueline I. 1994. “Rebuking the Enemies of the Lotus : Nichirenist Exclusivism in Historical Perspective.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 21:231-59.

Sugimori Kōji. 1976. Kenkyū / sōka gakkai. Tokyo: Jiyūsha.

Suzuki Hiroshi. 1970. Toshiteki sekai. Tokyo: Seishin Shobō.

Tamano Kazushi. 2008. Sōka gakkai no kenkyū. Tokyo: Kōdansha.

Toda Jōsei. 1981-1990. Toda Jōsei zenshū (9 volumes). Tokyo: Seikyō Shinbunsha.

Toda Jōsei. 1961. Toda Jōsei-sensei kōenshū jō / ge. Tokyo: Sōka Gakkai.

Toda Jōsei. 1961. Toda Jōsei-sensei ronbunshū. Tokyo: Sōka Gakkai.

Tōkyō Daigaku Hokekyō Kenkyūkai. 1975. Sōka gakkai no rinen to jissen. Tokyo: Daisan Bunmeisha.

Tōkyō Daigaku Hokekyō Kenkyūkai, ed. 1962. Nichiren shōshū sōka gakkai . Tokyo: Sankibō Busshorin.

White, James Wilson. 1970. The Sōkagakkai and Mass Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Yamazaki Masatomo. 2001. “Gekkan Pen” jiken: Umoreteita shinjitsu. Tokyo: Daisan Shokan.

Publication Date:

1 December 2013

known as Bocco, a few hundred metres outside the main village. At about four o’clock in the afternoon she recalls sitting on the grass putting flowers into bunches. She felt someone lift her up and, thinking it was her aunt, turned round to see an unknown woman with a beautiful face. Angela was a sole visionary, as the other children did not share this experience (one of the characteristics of a successful and long-term apparition movement is clarity over whom the Madonna is speaking through; a multiplicity of voices may harm the reputation of the case). Angela immediately identified her vision as the Virgin Mary, and this was confirmed in the second apparition one month later on the July 4, 1947, when the vision declared herself to be Mary. This was further clarified on the August 4, when she referred to herself as “Mary, Help of Christians, Refuge of Sinners.” These are traditional titles of Mary.

known as Bocco, a few hundred metres outside the main village. At about four o’clock in the afternoon she recalls sitting on the grass putting flowers into bunches. She felt someone lift her up and, thinking it was her aunt, turned round to see an unknown woman with a beautiful face. Angela was a sole visionary, as the other children did not share this experience (one of the characteristics of a successful and long-term apparition movement is clarity over whom the Madonna is speaking through; a multiplicity of voices may harm the reputation of the case). Angela immediately identified her vision as the Virgin Mary, and this was confirmed in the second apparition one month later on the July 4, 1947, when the vision declared herself to be Mary. This was further clarified on the August 4, when she referred to herself as “Mary, Help of Christians, Refuge of Sinners.” These are traditional titles of Mary.

of their innocence, a view repeated by Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, in The Message of Fatima (Bertone and Ratzinger 2000). However, my recent book, Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th Century Catholic Europe asks whether putting child seers under the spotlight of public attention would be regarded as acceptable any longer given the developing concern about child welfare. Gilles Bouhours of Espis in France (where visions occurred to a group of children between 1946 and 1950) was only two years old when he was recognised as a visionary. Unsurprisingly, then, most prominent visionaries after the early 1980s (when the Medjugorje children began to have visions) have been adults. The revival of Catholic devotion due to apparitions to rural children while animal herding [Image at right] has been a standard motif in Europe across the centuries, but this phenomenon is disappearing now.

of their innocence, a view repeated by Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, in The Message of Fatima (Bertone and Ratzinger 2000). However, my recent book, Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th Century Catholic Europe asks whether putting child seers under the spotlight of public attention would be regarded as acceptable any longer given the developing concern about child welfare. Gilles Bouhours of Espis in France (where visions occurred to a group of children between 1946 and 1950) was only two years old when he was recognised as a visionary. Unsurprisingly, then, most prominent visionaries after the early 1980s (when the Medjugorje children began to have visions) have been adults. The revival of Catholic devotion due to apparitions to rural children while animal herding [Image at right] has been a standard motif in Europe across the centuries, but this phenomenon is disappearing now.

around whether or not that is true. Gardner contended that he was initiated into the New Forest Coven, by Dorothy Clutterbuck in 1939. Members of this coven claimed that theirs was a traditional Wiccan coven whose rituals and practices had been passed down since pre- Christian times.