FETHULLAH GÜLEN MOVEMENT TIMELINE

1938 or 1941 (April 27): Fethullah Gülen was born in the northeastern city of Erzurum, Turkey. A birth year discrepancy exists throughout biographical sources.

1946-1949: Gülen received an elementary school education in Turkey’s state-administered education system. Gülen did not complete his elementary education, but later completed an exam equivalency.

1951-1957: Gülen studied Islam under the tutelage of several different Hanafi religious masters and community leaders, including his father, Ramiz Gülen, as well as Haci Sikti Effendi, Sadi Effendi, and Osman Bektaș.

1957: Gülen’s first acquaintance with Turkey’s Nur Movement (Nur Hareketi, i.e., followers of Said Nursi) and with the Risal-i Nur Külliyatı (RNK, Epistles of Light Collection – the collected teachings of Said Nursi).

1966: Gülen moved to İzmir, Turkey where he worked as a religious teacher at Kestanepazarı Mosque as an employee of Turkey’s Presidency of Religious Affairs (Diyanet).

1966-1971: Gülen’s popularity began to grow and a community of loyal admirers emerged.

1971 (March 12): Turkey’s second military coup since the establishment of the Republic in 1923. Gülen was arrested for being the alleged leader of an illegal religious community, and although released within days, he was briefly barred from public speaking.

1976: The first two Gülen Movement (GM) institutions were established: Türkiye Öğretmenler Vakfı (Turkish Teachers Foundation) and Akyazılı Orta ve Yüksek Eğitim Vakfı (The Akyazılı Foundation for Middle and Higher Education).

1979: The first GM periodical Sızıntı (Trickle), was published.

1980-1983: Turkey’s third military-led coup d’état and junta took place.

1982: Yamanlar College (high school) in İzmir and Fatih College (high school) in Istanbul became the first “Gülen-inspired schools” (GISs) in Turkey.

1983-1990: Institutional growth and expansion of GM-affiliated education movement in Turkey (private, for-profit schools and central exam preparatory centers with an emphasis on mathematics and natural/physical sciences) took place.

1986: GM affiliates purchase Zaman Newspaper.

1991-2001: GISs opened in countries outside Turkey, throughout post-Soviet Central Asia, Russia, and post-Cold War Balkan countries. Later expansion occurred in South and Southeast Asia.

1994: The Gazeteciler ve Yazarlar Vakfı (GYV, Journalists and Writers Foundation) was established in Istanbul following the “Abant Platform,” a GM-organized conference that brought rival public intellectuals together for several days of “dialogue.” Fethullah Gülen was made the GYV’s honorary president.

1995-1998: Gülen was active in Turkish public life and opinion. He gave several interviews to a number of widely circulated Turkish news dailies, engaged in high profile meetings with a diverse group of political and religious community leaders, and more widely established himself as an influential religious personality in Turkey.

1994: İş Hayatı Dayanışma Derneği (IȘHAD, The Association for Solidarity in Business Life) was established by a group of small to medium, export-oriented GM-affiliated businessmen.

1996-1997: Turkey’s Islamist Refah Partisi (RP, Welfare Party) came to power in a coalition with the center-right True Path Party. The RP’s Necmettin Erbakan became Turkey’s first “Islamist” Prime Minister.

1996: Asya Finans (now Bank Asya) was established by a small group of capitalists affiliated with Fethullah Gülen.

1997 (February 28): Turkey’s third military-led intervention into politics, known infamously as Turkey’s “post-modern coup,” took place. The RP was forced from power and Erbakan was banned from politics for life.

1997-1999: There was a Turkish state crackdown on religious community activity. The GM was scrutinized for being a clandestine religious community with alleged ulterior motives.

1998-2016: GISs opened throughout Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Western Europe, and the United States.

1998 (September 2): Gülen met with Pope John Paul II for a discussion about world relations between Catholics and Muslims.

1999: Gülen traveled from Turkey to the United States, according to spokespeople close to him, due to medical necessity.

1999: Gülen took up residence in the United States, which he has maintained (most recently in Saylorsburg, PA).

1999: A video broadcast on Turkish television showed Gülen allegedly instructing his followers to “move into the arteries of the system until you reach all the power centers.”

1999: Rumi Forum established in Washington, DC as the first (of many) interfaith and intercultural GM-affiliated outreach and public relations institutions in the United States.

2000: Gülen indicted on conspiracy charges in absentia in Turkey and an arrest warrant was issued.

2001 (April): The first academic conference organized by GM-affiliates about Fethullah Gülen and the Gülen Movement took place at Georgetown University.

2002 (November): The “Islamist-roots” Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, Justice and Development Party) came to power in Turkey.

2002-2011: An unofficial alliance between the AKP and the GM formed that constituted Turkey’s “conservative democratic” coalition.

2003-2016: A countrywide expansion of GM-affiliated public charter schools took place in the United States. As of July 2023, there were approximately 150 publicly chartered GISs in twenty-six states and in Washington D.C.

2005: Türkiye Işadamları ve Sanayiciler Konfederasyonu (TUSKON, The Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists) was established under the leadership of the GM-affiliated IȘHAD. It became Turkey’s largest business-related non-governmental organization.

2006: Gülen was acquitted of conspiracy charges in Turkey

2007 (January): The GM-affiliated Today’s Zaman was first published as Turkey’s third English-language news daily and immediately became its largest in circulation.

2007 (January): A weapons cache of military-issued arms was found in an apartment in Istanbul. The “Ergenekon investigation” eventually led to an alleged network of retired and active military personnel and social/business elites who conspired to topple the AKP government.

2007-2013: The Ergenekon trials took place in Turkey, with 275 people, including several retired Turkish generals, issued sentences.

2007: The Gülen Institute was established at the University of Houston in Houston, TX.

2008: Fethullah Gülen was named Prospect and Foreign Policy Magazine’s “World’s Most Influential Public Intellectual” via the results of an online poll. Editors at the two magazines ran series of articles attempting to explain how and why Gülen won.

2008 (November): Gülen won a long legal battle over his immigration status in the United States and was granted permanent residency (i.e., “green card”).

2011: A schism between the GM and Turkey’s governing AKP began.

2011(January): The State Senate of Texas passed Resolution Number 85 recognizing Fethullah Gülen “for his ongoing and inspirational contributions to the promotion of peace and understanding.”

2013 (June-July): The popular protest known as the “Gezi Park Uprising,” which began in Istanbul, spread to over sixty Turkish cities. Turkish police forces put the protest down with heavy force, which received international condemnation.

2013 (November): The GM-affiliated Zaman Newspaper reported on the AKP’s intention to reform Turkey’s education system by closing all standardized examination prep schools. The widespread perception was that this was an AKP-led attack on the GM whose affiliates control many of these institutions.

2013 (December 17 and 25): Arrests of family members of high-ranking AKP officials on charges of bribery, corruption, and graft occurred. These events were framed by Prime Minister Erdoğan and interpreted by Turkish public opinion as a retaliation by GM loyalists in Turkey’s police forces against the AKP.

2014 (January): Erdoğan rebranded the GM the Fethullahist Terror Organization (FETO).

2014 (January)-2016 (July): Erdogan and the AKP-led Turkish government more forcibly cracked down upon GM-affiliates, individuals, and institutions.

2014 (January): TUSKON, the GM’s business consortium, collapsed.

2015 (October)-2016 (September): GM-affiliated Koza-Ipek Holding (cross-sector firm valued in the billions of dollars) was raided, placed under stated control, and eventually seized by Turkey’s Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (Tasarruf Mevduatı Sigorta Fonu, TMSF).

2015: All state contracts with GM-affiliated Bank Asya were terminated. Mass divestment from the bank ensued, resulting in seismic losses.

2015: GM-affiliated Kaynak Corporation was seized by the TMSF and placed under the control of trustees.

2016 (March): GM-affiliated Feza Media (including Zaman and Today’s Zaman newspapers) was raided and ultimately seized by the TMSF.

2016 (July 15): Turkey experienced a failed coups d’état when alleged Gülenist actors in the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) briefly seized Ataturk Airport, tool over a handful of news organizations, and commenced an airstrike on the Turkish Parliament building.

2016 (July 15)–2018 (July 15): Turkey implemented a State of Emergency following the coup attempt that temporarily lifted Turkey’s responsibilities to protect the human rights of suspected “terrorists.” Erdoğan’s aim to destroy the GM in Turkey received legal cover to forgo due process for the accused.

2016 (July 18): Bank Aysa’s assets frozen and all depositors designated “aiders and abettors to terrorists.” Bank Asya’s banking license revoked on July 22, and all remaining assets fell under the authority of the TMSF.

2016 (August): GM-affiliated Dumankaya Holding was seized by the TMSF (and then liquidated in 2018) along with the Naksan Holding (liquidated in 2021). By the end of 2016, approximately 500 allegedly GM-affiliated companies had been seized by the Turkish state and placed under the authority of TMSF.

2017 (April): Referendum held to facilitate a shift in Turkish governance from a Parliamentary system with executive power divided between a Prime Minister and a President, to a “presidential system” that united the powers of these two offices. The referendum narrowly passed setting the stage for a Presidential election in 2018.

2018 (June): Recep Tayyip Erdoğan won the Presidential elections to become Turkey’s twelfth president since 1923, but the first to wield consolidated executive power since Mustafa Kemal Atatürk died in 1938.

2022 (January): All Kaynak assets were sold and liquidated by TMSF.

2016 (July)–2023 (July): Over 170 media outlets in Turkey closed.

2023 (June): Recep Tayyip Erdogan won a second five-year presidential term.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

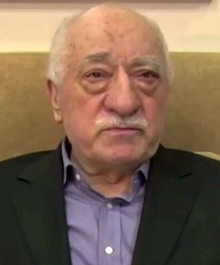

For years, actors associated with the community of Fethullah Gülen [Image at right] referred to themselves by the moniker Hizmet, the Turkish word for “service” [to/for others]. Individuals were designated “hizmet ihasanları” (people of service). Critical observers, by contrast, preferred to designate Gülen’s followers as “the Cemaat” [Jamaat], an Arabic-derived term meaning community or assembly. More polemical titles for affiliated individuals included, Gülenciler (“Gülenists”), “Fethullacılar” (Fetullahists).

Due to the loaded connotation of these terms, before the GM’s great fall, between 2012 and 2018, dispassionate observers (academicians, journalists, politicians, or policy analysts) preferred a more general term, “the Gülen Movement” (GM). Notwithstanding how it was referred, before 2012, Hizmet/the Cemaat/the GM signified thousands of institutions and millions of individuals in Turkey, together with affiliates in over 120 countries throughout the world. Although anchored upon a foundation of math and science-focused private (or privately managed) education, the GM also comprised initiatives in mass media, international trade, finance, information communication technologies, construction, legal services, accounting, and outreach/public relations. Before what GM apologists refer to as Erdoğan’s and the Adalet ve Kalkınma Parti’s (AKP, Justice and Development Party) post-2012 “witch hunt” against GM enterprises and affiliates, this Islamist community, with modest beginnings in the late 1960s, grew to become Turkey’s largest and most influential collective mobilizations.

The GM began as a splinter group of a pre-existing community, the Nur, followers of “Bediüzzaman” (“Wonder of the Age”) Said Nursi (d. 1960). [Image at right] As a teenager, Fethullah Gülen was exposed to Said Nursi’s commentary on the Qur’an, the Risale-i Nur Külliyatı (RNK, Epistles of Light Collection). Composed of essays and answers to questions written in the form of letters to his students, the RNK espoused a modernist interpretation of Qur’anic teachings. Among the most central of these teachings was an articulation about the inherent harmony between Islam and modern science, together with an emphatic plea for Muslims to become educated in modern knowledge, albeit with grounding in Islamic morality (Mardin 1989). Thousands of pages long, the RNK became a central source of knowledge for millions of pious-minded Turks who were subjected to Turkey’s process of social secularization during the formative decades of the Republic (1923-1950). By the time of Nursi’s death in 1960, the Nur represented millions of people in several major cities. In the RNK, and in the social networks created by Nur reading groups (dershane), followers of Nursi forged a collective source of identity that allowed them to harmonize their conservative identities as rural to urban migrants with the demands of modern Turkish nationalism and a growing industrial market economy.

After Nursi’s passing, the Nur splintered into several groups, each contesting with others about how best to disseminate Nursi’s teachings. Although among the youngest of the Nur offshoots, by the late 1980s Gülen’s admirers had rearticulated much of the Nur’s organizational habits and had applied them toward the establishment of a countrywide education, business, financial, and mass media network. By the late 1990s, the GM had become, according to some observers, the largest and most influential of all Nur communities (Hendrick 2013; Yavuz 2003a; Yavuz and Esposito eds. 2003; Yavuz 2013) and according to others, a distinct socio-political entity (Turam 2006).

Known as “Hocaeffendi” (“Esteemed Teacher”) to those who revere him, Fethullah Gülen was born in 1938 or in 1941 in the Northwestern Turkish City of Erzurum. The year of his birth is under contest, as several internally produced sources indicate 1938, while others indicate 1941. Loyalists point to this discrepancy as being of little consequence by suggesting that his parents were late registering their son’s birth, and that his age is of little importance. Hendrick (2013), however, discusses this discrepancy as merely the first instance of an entrenched pattern of “strategic ambiguity” that is employed by GM activists when discussing their leader and his organization (Chapter 3 and Chapter 8). These include how and when Gülen is to be considered a community leader, how and when he is to be considered an intellectual, a teacher, a social movement figure, or simply a humble and reclusive writer whose ideas change with circumstance. Similarly, when a person, a business, a school, a news outfit, or an outreach organization is either highlighted or denied as being part of the GM depended not only upon context, but also upon who was inquiring and for what reasons. Discussed in more detail below, the ambiguity with which individuals and institutions connect with one another in a worldwide social network is at the same time one of the GM’s primary strengths as well as one of its inevitable weaknesses.

Beginning in the late 1960s as a splinter group of Nursi followers, by the late 1970s, Fethullah Gülen was attracting large crowds. Around this time, his followers operated several student dormitories in Western Turkey, and audiocassettes of his sermons were becoming more widely disseminated. Between 1980 and 1983, during modern Turkey’s longest military junta, Gülen’s followers found opportunity in private education (Hendrick 2013; Yavuz 2003). To avoid state suppression as a clandestine religious community, they restructured several pre-existing dormitories to function as private, for-profit educational institutions. In 1982, Yamanlar High School in İzmir and Fatih High School in Istanbul became the first “Gülen-inspired schools” (GISs) in Turkey. Over the course of the 1980s, dozens more institutions were opened. In addition to private elementary and secondary schools, the GM enterprise expanded quickly into the field of standardized examination preparation. Called dershaneler (“lesson houses”), the GM eventually cornered a niche in cram course curriculum (Hendrick 2013). When students at GM-affiliated dershaneler began to routinely test well on Turkey’s centralized high school and university placement exams, and when high school students began to routinely win national scholastic competitions, it became difficult for critics in Turkey to support their claims of religious brainwashing at GISs, or for them to support their accusations that the GM was nothing more than a clandestine Islamist group aiming to overthrow Turkey’s secular republic (Turam 2006).

Success in secular math/science and exam-based education created opportunities to expand into other sectors. A youth-oriented organizational model blossomed in the 1980s when hundreds of thousands of bright students were recruited into the movement through the mechanism of exam prep schools. Aspiring university students were encouraged by “ağabeyler” (“older brothers”) to dedicate much of their time toward preparation for Turkey’s centralized university entrance exam. Students with ties to the GM network had access to instruction outside class at GM-affiliated student dormitories and apartments called “işık evleri” (“houses of light”). If they scored well on the exam, students would earn a spot at a Turkish university. After doing so, students were contacted by their former cram course teachers (or perhaps by a house ağabey) about their plans for room and board while at university, wherein, they were offered subsidized living at a GM-affiliated işık evi. While living at an işık evi, university students were not only encouraged to keep up with their studies, but also to acquaint themselves with Gülen’s and Nursi’s teachings.

Connecting students to a growing network of schools, education-related businesses, media companies, information and communication companies, publishing firms, exporters, and finance sector workers allowed the GM to create for itself a growing pool of human resources from which to draw to create a vast economic network of suppliers, clients, and patrons. Collectively, the GM’s success in a variety of sectors created a successful variation of “market Islam” in Turkey (Hendrick 2013). GISs were not only outfitted with teachers via a vast social network, but also with media and IT equipment, textbooks, and stationary goods via affiliated firms. Owners of these firms maintained close social ties to the GM, and often supported the GM’s mission by subsidizing student rent at işık evleri, by providing scholarships to students to attend a private GIS, or by providing startup capital for a new GM venture. In 1986, for instance, GM-affiliates bought a pre-existing newspaper, Zaman Gazetesi, and once Turkey liberalized broadcast media in the early 1990s, the same media firm began its first television venture, Samanyolu TV. Both ventures were begun with start-up capital secured via GM social networks orbiting GM-affiliated schools, dorms, and apartments.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the GM seized upon the Turkish state’s effort to cultivate relations with post-Soviet republics in Central Asia and the Balkans. GISs were begun with Turkish start-up capital throughout both regions, and affiliated business ventures followed. To facilitate trade with these regions, an export-oriented trade association emerged, İş Hayatı Dayanışma Derneği (IȘHAD, The Association for Solidarity in Business Life) in 1994). A shipping and transport firm was established around the same time, as was an “Islamic” (interest-free, profit sharing) financial institution (Asya Finans, later Bank Asya), which was established in 1996).

With greater size and influence came a greater need to frame a public image that could be perceived as productive and worthy of social prestige. In a public relations campaign that began in 1994, another wing of the GM’s operational ethos was born in the Turkish mountain town of Abant. There, a group of GM-affiliated outreach activists gathered several Turkey’s most widely read news journalists and opinion columnists, as well as a number of academicians and writers from a variety of fields. Known thereafter as “the Abant Platform,” this meeting was envisioned as an opportunity for a diverse group of thinkers to discuss some of the more troubling aspects of Turkish political society. It spawned the emergence of the primary GM-affiliated think tank and outreach organization, The Gazeticiler ve Yazarlar Vakfı (GYV,

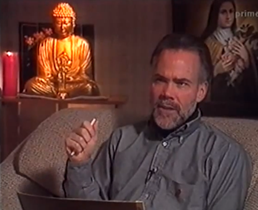

Journalists and Writers Foundation). Every year since, and often several times a year, the Abant Platform and the GYV have organized a variety of policy-oriented discussion forums and academic conferences on a wide range of topics. Making overtures beyond Turkey, in 1997 Gülen arranged a meeting with Pope John Paul II to discuss Muslim/Christian relations. [Image at right] Images of this meeting became a symbolic reference for Gülen’s handlers to point to when they discussed their sincerity in the fields of interfaith and intercultural dialogue.

The GM’s expansion in the 1990s came at a time when a more traditional variation of “political Islam” was on the rise under the leadership of Necmettin Erbakan, who led his Refah Partisi (RP, Welfare Party) to several municipal electoral victories in 1995 and to national victory in 1996. The RP formed a coalition government with the center right True Path Party, and Erbakan became Turkey’s first “Islamist” Prime Minster. Focusing its efforts outside party politics, the GM was able to navigate RP’s rise and abrupt fall during Turkey’s “post-modern coup” in 1997. Notwithstanding, the GM did not come out of this period unscathed. In what became infamously known as “The February 28 process,” Turkey’s military forced Erbakan from power by threatening a military coup. In the two years that followed, the state cracked down on all forms of faith-based social and political organizing. In this context Fethullah Gülen fled to the United States in early 1999. According to his spokespeople, the reason was for medical treatment for a chronic condition. Whether for medical reasons or not, shortly after his departure from Turkey, Gülen was indicted in absentia for being the leader of an alleged criminal organization that aimed to overthrow the Turkish state. He has lived in the U.S. ever since.

Shortly after Gülen’s move to the U.S., GM activists created GYV-modeled outreach and dialogue institutions throughout the country. Now found throughout the world where the GM manages GISs and where GM-affiliates do business, the U.S. hosts the most influential of these institutions outside Turkey

(and the most in number). Between 1999 and 2010, the most influential of these institutions were th e Rumi Forum in Washington D. C. (established in 1999), the Dialogue Institute in Houston (established in 2002), the Niagara Foundation in Chicago (established in 2004), and the Pacifica Institute in Southern California (established in 2003). Each of these organizations organized satellite efforts in smaller cities and college towns. In 2010, over forty separate GM-affiliated interfaith and outreach institutions in the U.S. consolidated under an umbrella organization, [Image at right] The Turkic American Alliance, which continues as the primary public face of the GM in the U.S.

e Rumi Forum in Washington D. C. (established in 1999), the Dialogue Institute in Houston (established in 2002), the Niagara Foundation in Chicago (established in 2004), and the Pacifica Institute in Southern California (established in 2003). Each of these organizations organized satellite efforts in smaller cities and college towns. In 2010, over forty separate GM-affiliated interfaith and outreach institutions in the U.S. consolidated under an umbrella organization, [Image at right] The Turkic American Alliance, which continues as the primary public face of the GM in the U.S.

In 2008, a federal court in Pennsylvania granted Gülen permanent residency in the U.S. in a decision that overturned a previous denial by the Department of Homeland Security. In the same year, Gülen was  named “the world’s most influential public intellectual” in an online poll conducted by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. [Image at right] Although critiqued by the editors of both magazines as illustrating little more than a keen ability to manipulate the outcomes of an online poll, between the years of 2007 and 2012 the GM reached an apex in prestige and influence in Turkey and in countries around the world.

named “the world’s most influential public intellectual” in an online poll conducted by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. [Image at right] Although critiqued by the editors of both magazines as illustrating little more than a keen ability to manipulate the outcomes of an online poll, between the years of 2007 and 2012 the GM reached an apex in prestige and influence in Turkey and in countries around the world.

Indeed, throughout the 2000s, efforts on the part of GM activists in the U.S. and Western Europe to present Fethullah Gülen as a viable alternative to more confrontational articulations of Muslim political identity produced much reward. Employing tactics detailed by Hendrick (2013) and Hendrick (2018), GM activists visited thousands of influential people in American and European academia, mass media, faith communities, state appointment, elected politics, and private business. They organized subsidized leisure travel for groups of these people to Turkey, where professors, politicians, journalists, and religious congregation leaders toured Istanbul, İzmir, Konya, and other places rich with Anatolian culture and history. During these trips, these “recruited sympathizers” also learned about the GM’s activities in education, media, and business.

Exemplifying a grassroots strategy to recruit sympathy from people of influence, by 2012, the GM had subsidized over 6,000 trips to Turkey from the U.S. and had organized over a dozen conferences whose contributing authors wrote essays promoting the GM’s efforts. Most of these conferences resulted in book publications (Barton, Weller, and Yılmaz 2013; Esposito and Yılmaz 2010; Hunt and Aslandoğan 2007; Yavuz and Esposito 2003; Yurtsever 2008).

This dramatic expansion of GM was soon followed by an equally dramatic fall. Following the cessation of Turkey’s Ergenekon and Sledgehammer trials[1] and the subsequent subordination of the Turkish military to civilian authority, the GM and the AKP competed to fill Turkey’s power vacuum. In allegations that are emphatically denied by GM leaders and in GM media sources, between 2003 and 2011 GM affiliates took control of much of the Turkish judiciary and police forces throughout the country. Following the end of the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases in 2013, GM forces in both institutions are believed to have shifted their investigative attention from the old guard to the AKP. When Prime Minster Erdoğan discovered wiretaps in his office in late 2012, it was widely assumed that the GM was somehow involved.

Rumblings of tensions became deafening in November of 2013 when the GM-affiliated Zaman published a story about the AKP’s plan to close all standardized exam prep schools (dershaneler) as part of a larger education reform. As the primary source of recruitment for the GM, this move constituted an existential attack on the GM’s ability to sustain itself in the long term. On December 17, 2013, Istanbul prosecutors with alleged links to the GM retaliated by arresting the sons of three AKP cabinet ministers, as well as several state bureaucrats and businessmen on charges of graft and corruption. Also arrested was an Azeri-Iranian businessman who was accused of orchestrating a gold smuggling operation between Turkey and Iran. Evidence included shoeboxes of cash found in suspects’ homes, and phone recordings that, among other things, implicated several AKP officials, including Erdoğan’s son.

Erdoğan was quick to slam what he called “the parallel state” (referring to the GM) for attempting to subvert the AKP. Hundreds of police personnel were fired, and dozens of prosecutors were removed. Having stalled the investigation into AKP corruption, much of the audio-recording evidence that led to the December 2013 arrests was leaked to an anonymous source that posted numerous voice recordings on Twitter. AKP officials (including Erdoğan himself) were implicated in graft, bribery, and corruption. With municipal elections upcoming in March, Erdoğan proclaimed that democracy was under siege in Turkey. Erdoğan subsequently blocked Turkish access to Twitter for two weeks. Although the ban was overturned, the March 30 elections came and went, and the AKP was able to claim overwhelming victory (forty-six percent).

Immediately after the elections, Erdoğan stepped up his fight against the GM’s “parallel state.” His regime continued to purge police departments and prosecutors’ offices, encouraged public divestment from the GM’s Bank Asya, blocked state contracts with GM-affiliated firms, and canceled the state’s support for GM-sponsored events. More personally, Prime Minster Erdoğan filed civil lawsuits against several GM-affiliated journalists for libel. For his part, Gülen responded with emphatic denials that he or his admirers had anything to do with illegal wiretappings, with stirring up public unrest, or with orchestrating criminal investigations.

Why did these two forces turn on each other? Somewhat confusing for some, it is important to emphasize that the GM and the AKP were partners in a decade-long effort of domestic and foreign policy reform. Their worldviews were so aligned that by the time of the AKP’s third term, analysts pointed to the fact that “Gülenism” had become official state ideology in Turkey (Tuğal 2013). Among their shared goals included an effort to dismantle the Turkish military’s oversight of elected governance and an effort to carve out a position for affiliated capital in Turkey’s big capital markets. Moreover, both aimed to settle old scores with secular party leaders and media moguls, and both sought to facilitate pious revivalism in Turkey’s public sphere. The fissure within Turkey’s Islamist power structure thus had little to do with ideas and everything to do with power. What this struggle proved, however, was that however influential the GM had become in Turkey, its collective influence was no match for the institutional power of the AKP-led Turkish state.

On July 15, 2016, those who long-feared Fethullah Gülen were seemingly validated when a faction of the TSK perpetrated a coup attempt that left hundreds dead, and a country in trauma. It is impossible, without access to evidence and years of investigation, to know the specifics of the GM’s responsibility for the horrific events of July 15, 2016. For their part, GM actors emphatically deny both their mobilization as a “parallel state,” and any role whatsoever in the coup attempt (Dumanlı 2015). Indeed, beginning over two years before July 2016, and continuing with vigor ever since, the GM’s public relations agenda outside Turkey aimed to refocus world attention to Erdoğan’s authoritarian tendencies, to the lack of due process for those arrested in the context of the coup investigations, and to the seizure of property, torture, and other human rights abuses (e.g., Advocates of a Silenced Turkey (Advocates of Silenced Turkey website 2023) and the Stockholm Center for Freedom (Stockholm Center for Freedom website 2017). Notwithstanding, the Turkish public widely believes the GM to be responsible for the failed putsch (Aydıntaşbaş 2016). Having targeted Gülen and the GM for several years leading up to July 2016, Erdogan was quick to assign guilt himself, and the GM has been on the run ever since.

In the two years leading up to July 2016, Erdoğan set his sights on destroying the GM. After the successful 2014 reform of Turkey’s education system, the GM’s primary method of recruitment was dismantled. After this, the government began seizing GM-affiliated holding firms, and in turn, discrediting GM-affiliated enterprises. In early 2014, the GM’s Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists (Türkiye İşadamları ve Sanayiciler Konfederasyonu, TUSKON) collapsed because of mass divestment. Next to fall was Koza-Ipek Holding, a massive Turkish firm, and one of the largest that backed GM initiatives. Active in mining, construction, energy, and mass news and television media, on the eve of its seizure Koza-Ipek was valued in the billions. In late October 2015, Turkish authorities raided Koza-Ipek and confiscated its over twenty companies, including Bügün and Milet newspapers and Bügün TV. After the coup attempt, the Koza-Ipek Group was placed under the control of the state Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (Tasarruf Mevduatı Sigorta Fonu, TMSF).

Arguably more significant in the months before the coup attempt was the state seizure of Feza Media Group, the GM’s central media conglomerate and the parent of its flagship Zaman and Today’s Zaman newspapers, Samanyolu TV, Aksiyon (political/economic magazine) publications, and over a dozen other magazines, news agencies, periodicals, papers, and websites. Constituting a near fatal blow to the GM’s ability to control the narrative; in March 2016 state police raided Zaman. Shortly following the 2016 coup attempt, State Decree Law Number 668 declared as follows: “the newspapers and periodicals…. which belong to, or which are connected to, or affiliated with, the Gülenist Terror Organization (FETÖ/PDY), have been shut down” (ASS 2018:18).

Following the coup attempt, over 1000 schools affiliated with the GM were seized and closed. Shortly after, Boydak Holding was seized and its leaders arrested on charges of aiding and abetting terrorism. Boydak employed over 15,000 people. In September 2016, the firm came under the control of the TMSF. In July 2018, Memduh Boydak was sentenced to eighteen years in prison. Then came Bank Asya. In 2015, all state contracts were canceled leading to mass divestment. Two days after the July 2016 coup attempt, all Bank Asya’s assets were frozen, and its license revoked. Bank Asya depositors were declared aiders and abettors to terrorists. Kaynak Corporation, which included over thirty companies and was the central firm in the GM’s global education enterprise, was also assigned trustees by the Turkish government in 2015 and eventually came under the control of the TMSF. Holding, a massive conglomerate active in energy, plastics, construction, and textiles along with Dumankaya Holding also went down. Both firms were seized in 2016 and placed under the authority of the TMSF. The latter was liquidated in 2018, the former in late 2021. On the eve of the AK Party-GM conflict, the TMSF’s total assets stood at (TY) 19,726 billion (approximately $850 million). By March 2020, that number had grown to (TY) 97,573 billion ($4.2 billion) (SDIF 2021). By January 2022, over 850 companies alleged to be GM-affiliated were seized by Turkish authorities and placed under the control of the TMSF with assets totally over $5,000,000,000 (SDIF 2021).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Gülen’s teachings are disseminated in print and online via hundreds of books, essay collections, periodicals, and websites. Although the entirety of his teachings is available in print in Turkish, a large body of his work (although often incomplete) is translated into English, and to a lesser degree into dozens of other world languages.

The central refrain in Gülen’s teachings is his call for “volunteers,” who are “filled with love for all of humanity,” “ideal humans” who represent what Gülen calls “the generation of hope.” This generation’s task is to cultivate a future “golden generation” (altın nesil) that will usher in a time love, tolerance, and harmony, and by default, that will create the conditions for Day of Judgment:

What we need now is not ordinary people, but rather people devoted to divine reality . . . people who by putting into practice their thoughts, lead first their own nation, and then all people, to enlightenment and to help them find God . . . dedicated spirits . . . (Gülen 2004:105-10).

GM-affiliated teachers, donating businessmen, outreach activists, journalists, and others constitute Gülen’s “blessed cadre” whose members are asked to dedicate their time, money, and efforts to create the conditions for the coming of the golden generation. Throughout his many essays on the topic, Gülen refers to the current “generation of hope” as an “army of light” and as “soldiers of truth.”

The “truth” that Gülen’s soldiers promote is parallel to the “truth” promoted by religious revivalists the world over. Gülen views humanity as having strayed from the path of morality and divinely inspired wisdom, which he views as a crisis stemming from empty consumerism (materialism), carnality, and individualism. Helping Turkish and world society recover from moral decline requires aksiyon insanları (humans of action) and hizmet insanları (humans of service) who can offer the coming generation irşad (moral guidance). Such guidance is presented at the micro level by elders (ağabeyler) and young people in the Gülen community, at the mezzo level in classrooms and in community social groups (sohbetler), and at the macro level via publishing and mass media. Collectively, the math and science-based education delivered at GISs in Turkey and around the world, the news and entertainment media published and broadcast via GM-affiliated media brands, the financial products offered by Bank Asya, the relief work provided by Kimse Yok Mu? and the thousands of services provided by GM-affiliated businesses collectively constitute hizmet (service) to humanity.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Turkey is a majority Sunni Muslim society. Underneath the state’s control of Islam, however, is a deep-rooted tradition of Sufism in Turkey. The Nakşibendi (Naqshbandi), the Mevlevi, Rifai, and others all have long histories in Anatolia. Both facets of historical Islam inform much of the worldview, organization, and ritualistic practice employed by Fethullah Gülen and the GM, but much of its collective practice is also emblematic of “invented tradition” that is somewhat unique to the GM case.

Teachers, authors, editors, journalists, businessmen, and bankers closely associated with the GM often live modern, but pious lifestyles. Most GM-affiliated individuals and institutions thrive in Turkey’s competitive market economy, and its schools have established a brand for themselves by emphasizing math, science, and business-related education. That being stated, different levels of affiliation in the community illustrate different levels of religiosity. Whether or not individuals pray five times a day (namaz; salat), whether they attend Friday prayers, avoids social vices like smoking cigarettes, or (if a woman) choose to cover varies throughout the GM community. The more “connected” someone is, however, the more likely he or she is encouraged to lead a more conservative lifestyle. Such encouragement happens but way of example set by others and typically begins when individuals are recruited to live in an işık evi while attending university. It is at these houses where someone typically attends his or her first sohbet.

In Islam, sohbet (pl. sohbetler) historically refers to a religiously oriented conversation between a Sufi sheikh and his disciple. The term has a pedagogical connotation, and the aim is typically to inculcate correct interpretations about living in accordance with Divine Will. In the GM, however, sohbet refers to the practice of meeting regularly in small groups to read the teachings of Fethullah Gülen and Said Nursi. The GM sohbet is, in many ways, a reformulation of a practice begun by followers of Said Nursi who, during the middle part of the twentieth century, would meet in small groups for reading and discussion of Nursi’s banned RNK. Not to be confused with exam prep schools in Turkey, Nur reading groups were called “dershane” and over the years became a regular identifying practice of the Nur. Continuing this practice as sohbet, the GM rationalized dershane meetings by gender and age, and repurposed them as spaces for socialization (Hendrick 2013).

Sohbetler are administered by senior students at GM işık evleri, by “spiritual coordinators” at GM-affiliated companies, and by respected ağabeyler/ablalar (elder brothers/sisters) and “hocalar” (teachers) in neighborhoods throughout Turkey and among GM communities throughout the world. Sociologically, “the GM sohbet reproduces an alternative public sphere that links individuals in Istanbul and London, Baku and Bangkok, New York and New Delhi, Buenos Aires and Timbuktu in a shared ritual of reading, socializing, money transfer, and communication exchange” (Hendrick 2013:116).

Hizmet and Himmet: The GM aims to cultivate ihlas (approval seeking from God) among all people for all daily actions, Yavuz (2013) explains that “Gülen not only seeks to mobilize the hearts and minds of millions of Turks but also succeeds in convincing them to commit to the mission of creating a better and more humane society and polity” (2013:77). This means that GM loyalists strive to mold individuals into agents of social change in accordance with socially conservative Muslim values and ethics. Gülen teaches that such change necessitates passive engagement with the social and political world, and in so doing; he asks hizmet insanları (people of service) to convince others of the “truth” by acting as models for emulation. The Turkish concept that anchors this method of recruitment to the GM mission is temsil, which Tittensor (2014) translates as “representation” (2014:75). How best to “represent” what Gülen calls “ideal humanity” is to offer hizmet (service) to others as an actor in the GM network.

In addition to “serving” the community through hizmet, individuals are also encouraged to serve the community though himmet (religiously motivated financial donation). In a refrain uttered throughout the community, individuals “give according to their means,” which refers to the fact that a while an editor at a GM-affiliated publishing firm may donate the equivalent of $300 a month to the “spiritual coordinator” in his company, a wealthy business owner may donate ten or twenty times that amount at a himmet donation gathering (Ebaugh 2010; Hendrick 2013).

The practices of himmet and hizmet are most vividly exemplified by university graduates who “volunteer” to teach at GISs in countries around the world. Now a common option for young post grads in Turkey, GM teachers typically travel to teach for comparatively little pay and are expected to work long hours, extra hours, and on weekends, and although paid a salary, they are still expected to regularly donate himmet. Likely having received some benefit from the GM earlier in life, however, (e.g., free tutoring, subsidized rent, etc.), teachers at GISs often report that they are not only willing but honored to “serve” as teachers throughout the world and to donate some portion of their income back to the community. In his writings, Fethullah Gülen often refers to teachers as GISs in Turkey and around the world as “self-sacrificing heroes.”

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Leadership in the GM is administered via a gendered, elder-based, and ethno-nationalist system of authority that extends throughout its worldwide network. [Image at right] At the top is Fethullah Gülen who lives in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania on a multi-house compound called the Golden Generation Retreat and Worship Center. From here, Gülen administers the GM as a passive charismatic leader who maintains direct communication only with a relatively small number of close confidants and students. These men, together with senior figures at GM institutions around the world, constitute the core of the GM’s organization. Affectionately called hocalar (teachers) these leaders comprise the GM’s core community (cemaat), a worldwide social network of totally devoted students of Hocaefendi Fethullah Gülen.

In addition to those who remained physically close to Gülen in the Poconos, before 2012 others directed or managed one of the dozens of dialogue and outreach organizations in the U.S., Europe, or Turkey. Others were writers who authored books about Fethullah Gülen, while others, before the AKP-led destruction of the GM in Turkey (see below) organized the various efforts of the GYV in Istanbul or published regular columns in Zaman, Today’s Zaman, Bügün, Taraf, or other GM-affiliated news publications (Hendrick 2013). All were men, and most traced their connection to Gülen’s early community of loyalists in Edirne and İzmir. Since a failed coup-attempt in July 2016 that the Turkish government blames on the GM, many of these figures are now in prison in Turkey for allegedly participating in a terrorist organization or living in exile.

Although thousands of women identify with the GM, teach (or taught) at GISs around the world, and participated in various aspects of social and business services at one or another GM-affiliated institution, the cemaat level of affiliation has always maintained a strict degree of gender privilege (Turam 2006). Moreover, despite its transnational engagement and despite the thousands of non-Turkish friends and admirers, the cemaat level of affiliation also maintains a strictly Turkish and Turkic bias.

A once-removed level of affiliation consists of a wide network of GM “friends” (arkadaşlar). Before the AKP-GM fallout began in 2012, and especially before the failed coup of July 2016 and the years of investigations since, this level of connectivity included hundreds of thousands of businesses that engaged with GM institutions in the marketplace as patrons and clients. A large portion of their employees (although not all) donated regularly to the movement (himmet), and many regularly attended sohbet. Although loyal to the movement, however, arkadaş social networks extended in unaffiliated directions thus distinguishing this level from the cemaat. Although business owners were likely to maintain very close relations with the GM, there was likely not a coordinator who collected himmet from employees. Indeed, some employees may have had very little to do with the GM at all. At this level, himmet was donated at regular collection meetings that were organized via social networks, rather than at a place of business, and hizmet was conceptualized less as a totalizing responsibility. Arkadaşlar might be businessmen, policemen, lawyers, academicians, or journalists. Some were employed in international trade, while others owned small shops or restaurants, or perhaps worked in information technologies, engineering, or government. Larger in size, the arkadaşlar level of affiliation constitutes most people who received an exam prep education at a GM cram school, who lived in GM-affiliated işık evleri while attending university, and who the GM relies upon for himmet.

Beyond arkadaşlar was a level of GM supporters and sympathizers (yandaşlar). This level of affiliation consisted both of Turks and non-Turks. Many were politicians; others were academicians. Some were journalists or appointed state bureaucrats; others were students or parents of students at GISs; some were people who benefitted from GM-facilitated foreign trade. From education to intercultural outreach/dialogue, from journalism to relief services, yandaşlar supported the GM’s efforts wherever they lived. Although not dedicated, many helped however they could. This may have come in the form of an education board member voting in favor of a charter school application in Toledo, Ohio after visiting Turkey on a sponsored dialogue tour, or it may come in the form of a labor rights attorney agreeing to write a sympathetic account of Gülen’s legal struggles in Turkey and the U.S. (Harrington 2011). Whoever and wherever they were (and wherever they remain), yandaşlar promoted the collective action of Turkey’s GM because they agreed that the service (hizmet) GM activists provide for world society is commendable.

The final stratum of affiliation was perhaps the largest, the weakest linked, and the most important for the GM’s continued expansion. This was the level of the unaware consumer. Most students at GISs in countries around the world, most readers of English language journalism produced by GM media firms, and countless numbers of Turkish and transnational consumers of products manufactured on the GM commodity chain remain completely unaware of the GM as a social entity

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Organized in a graduated network of affiliation, each of the periphery layers of GM organization (friends, sympathizers, and unaware consumers) have been dramatically reduced in number and impact since the failed coup of July 2016. What happened?

Since the GM’s inception, many of Turkey’s news columnists, public intellectuals, and politicians have asserted that GISs function as institutions for brainwashing Turkey’s youth in the interests of Gülen’s Islamist agenda. Turam (2006) begins with an exemplary narrative of this long-standing tension in Turkish public discourse. The long-standing claim was that Gülen emphasized education because to achieve his aims, he required loyalists to infiltrate the Turkish military, the country’s police forces, the judiciary, and other strategic institutions of state to purge the Turkish Republic from the inside out. To find their way into these institutions they needed to compete in a competitive labor market, which required an education centered network of schools, media, cross-sector service providers, and effective public relations.

Over the years, Gülen and his loyalists refuted these accusations by claiming that in a democracy anyone should be able to pursue career objectives according to their skills and interests. If policemen, lawyers, judges, and other bureaucrats personally affiliated with a religious community or social network, that should remain their personal business and should not implicate them in clandestine behavior. Despite such statements, however, arguably the most difficult challenge for Fethullah Gülen and GM leaders was to maintain a stated “non-political” identity. This task proved especially challenging when the GM formed a political and economic alliance with the AKP in the early 2000s.

In this context, it is important to emphasize that the AKP and the GM emerged as a coalition of like-minded social forces whose leaders pointed to the same historical enemies (e.g., secular Kemalists, “leftists,” etc.) as having stalled the political, economic, and social agency of their respective constituents (i.e., pious Turks). Indeed, during the first two terms of the AKP’s rule in Turkey (2002–2011), AKP leaders (even Prime Minster Erdoğan himself) regularly endorsed GM-sponsored events (e.g., the Abant Platform, The Turkish Language Olympics, TUSKON trade summits, etc.) and regularly praised the achievement of GM-affiliated “Turkish schools” on the visits to Thailand, Kenya, South Africa, and elsewhere. Likewise, until late-2013 GM affiliated media and outreach organizations regularly voiced support for AKP-led political initiatives as representing the maturation of Turkish democracy. Public companies such as Turkish Airlines became sponsors of GM-organized social and cultural events (e.g., Turkish Language Olympics, etc.), By 2011, several figures with known GM affinities ran and won as AK Party candidates (e.g., Hakan Şükür, Ertuğrul Günay, İdris Bal, Naim Şahin, Erdal Kalkan, Muhammad Çetin, among others).

After the AKP’s third electoral victory in 2011, however, overlapping interests between the GM and the AKP (e.g., conservative social politics, economically liberal development views, interests in removing the Turkish military’s oversight in Turkish politics and society) were no longer enough to hold maintain a coalition. The result was a bureaucratic, legal, and public relations war that continues. According to several observers, the beginning of the conflict extends back to 2010, while others point to one or another significant event in 2011 or 2012. Examples of tensions include Gülen’s public disagreement with the AKP’s handling of the infamous “Mavi Marmara Incident,” the 2012 subpoena of Hakan Fidan (the AKP-appointed Chief of National Intelligence) by a prosecutor with alleged ties to the GM, and public disagreement between Gülen and Prime Minster about the handling of the Gezi Park protests in the summer of 2013. Speculation about a brewing feud was proven correct toward the end of 2013 when these two forces more forcefully collided.

In 2023, the GM exists as a charismatic community in exile (Angey 2018; Tittensor 2018; Taş 2022; Wartmough and Öztürk 2018; Tee 2021). In countries around the world, schools have shuttered, thousands have been deported, and thousands more continue to make their way to countries still friendly to GM initiatives (e.g., the U.S., England, Australia, Sweden, others). In the United States, especially, the GM’s expansion in charter school education has continued unhindered. Originally hired directly by Erdoğan to investigate GM activities outside Turkey (with an emphasis on the US), Robert Amsterdam and Partners, LLP is an international law firm based in Canada that has published two books on the GM’s activities in the United States. Empire of Deceit (2017) and Web of Influence: Empire of Deceit Series Book 2 (2022) together present a damning critique of the GM’s use and alleged abuse of charter education funding via a pattern of self-dealing employed to create a highly valuable subeconomy that caters primarily to GM interests at the expense of students and teachers.

The GM has weathered these critiques in Utah, Georgia, Arizona, California, and elsewhere. Some schools have lost charter funding, others have endured tighter state oversight. At this writing, however, the GM continues to operate over 150 charter schools in the U.S. and is linked with dozens more affiliated enterprises in technology, engineering, law, real estate, construction, and other sectors. And much to Turkey’s dismay, two U.S. administrations have refused the Turkish state request to extradite the retired imam.

Although the movement that bears his name has been debased and defunded, many of its organizations outside Turkey are maintaining. For his part, Gülen is ill, late in years, spends most of his time inside his Pennsylvania compound, [Image at right] and survives today as a wanted man. Thus is the rise and fall of Fethullah Gülen.

IMAGES

Image #1: Fethullah Gülen.

Image #2: Said Nursi.

Image #3: Meeting between Fethullah Gülen and Pope John Paul II.

Image #4: Turkic American Alliance logo.

Image #5: Gülen Movement logo.

Image #6: Gülen’s residence, Golden Generation Retreat and Worship Center, in Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

Advocates for a Silenced Turkey (ASS). 2018. A Predatory Approach to Individual RIGHTS: ERDOGAN GOVERNMENT’S UNLAWFUL SEIZURES OF PRIVATE PROPERTIES AND COMPANIES IN TURKEY. Accessed from https://silencedturkey.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/A-PREDATORY-APPROACH-TO-INDIVIDUAL-RIGHTS-ERDOGAN-GOVERNMENT’S-UNLAWFUL-SEIZURES-OF-PRIVATE-PROPERTIES-AND-COMPANIES-IN-TURKEY.pdf on 1 June 2023.

Advocates of Silenced Turkey website. 2023. Accessed from https://silencedturkey.org on 15 July 2023.

Amsterdam, Robert. 2022. Web of Influence: Empire of Deceit Series Book 2, An Investigation of the Gulen Charter School Network. New York: Amsterdam & Partners, LLC.

Amsterdam, Robert. 2017. Empire of Deceit: An Investigation of the Gulen Charter School Network Book 1. New York: Amsterdam & Partners, LLC.

Angey, Gabrielle. 2018. “The Gülen Movement and the Transfer of a Political Conflict from Turkey to Senegal.” Politics, Religion, Ideology 19:53-68.

“Assets worth $11bn seized in Turkey crackdown.” 2017. Financial Times, July 17.

Aydıntaşbaş. Aslı. 2016. “The Good, The Bad, and the Gülenists: The Role of the Gülen Movement in Turkey’s Coup Attempt.” London: European Council on Foreign Relations.

Barton, Greg, Paul Weller, and Ihsan Yilmaz, eds. 2013. The Muslim World and Politics in Transition: Creative Contributions of the Gülen Movement. London. Bloomsbury Academic Publishers.

“Biden tells Turkey’s Erdogan: only a federal court can extradite Gulen.” 2016. Reuters, August 24.

Cook, Steven. 2018. “Neither Friend Nor Foe: The Future of US-Turkey Relations.” New York: Council of Foreign Relations, Special Report No. 82.

“Depositing money in Bank Asya on Gülen’s order proof of FETÖ membership.” 2018. Daily Sabah, February 12.

Dumanlı, Ekrem. 2015. Time to Talk: Gülen Answers the Question on the Association of the Hizmet Movement with the Parallel State, December 17 Corruption Investigation, and Other Critical Inquiries. New York: Blue Dome Press.

Ebaugh, Helen Rose. 2010. The Gülen Movement: A Sociological Analysis of a Civic Movement Rooted in Moderate Islam. New York: Springer.

Esposito, John and Ihsan Yilmaz, eds. 2010. Islam and Peace Building: Gülen Movement Initiatives. New York: Blue Dome Press.

Gallagher, Nancy. 2012. “Hizmet Intercultural Dialogue Trips to Turkey.” Pp. 73-96 in The Gülen Hizmet Movement and Its Transnational Activities: Case Studies of Altruistic Activism in Contemporary Islam, edited by Sandra Pandya and Nancy Gallagher. Boca Raton, FL: Brown Walker Press.

Harrington, James. 2011. Wrestling With Free Speech, Religious Freedom, and Democracy in Turkey: The Political Trials and Times of Fethullah Gülen. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Hendrick, Joshua D. 2013. Gülen: The Ambiguous Politics of Market Islam in Turkey and the World. New York: New York University Press.

Hunt, Robert and Alp Aslandoğan, eds. 2007. Muslim Citizens of the Globalized World. Somerset, NJ: The Light Publishing.

Mardin, Şerif. 1989. Religion and Social Change in Modern Turkey: The Case of Bediüzzaman Said Nursi. Albany: SUNY Press.

Pandya, Sophia and Nancy Gallagher, eds. 2012. The Gülen Hizmet Movement and Its Transnational Activities: Case Studies of Altruistic Activism in Contemporary Islam. Boca Raton, FL: Brown Walker Press.

Reynolds, Michael A. 2016. “Damaging Democracy: The U.S. Fethullah Gülen, and Turkey’s Upheaval.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, September 26. Accessed from http://www.fpri.org/article/2016/09/damaging-democracy-u-s-fethullah-gulen-turkeys-upheaval on 10 July 2023.

Rodrik, Dani. 2014. “The Plot Against the Generals.” Accessed from http://www.sss.ias.edu/files/pdfs/Rodrik/Commentary/Plot-Against-the-Generals.pdf on 10 July 2023.

Savings Deposit Insurance Fund. 2021. Annual Report 2021. Accessed from https://www.tmsf.org.tr/en/Rapor/YillikRapor on 1 June 2023.

Savings Deposit Insurance Fund. 2014. Annual Report 2014. Accessed from https://www.tmsf.org.tr/en/Rapor/YillikRapor on 1 June 2023.

“State fund ‘takes control of Koza-İpek Holding’s 18 companies in failed coup attempt probe.” 2016. Hürriyet Daily News. Accessed from https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/state-fund-takes-control-of-koza-ipek-holdings-18-companies-in-failed-coup-attempt-probe-10374819 on 9 May 2023.

Stockholm Center for Freedom website. 2017. Accessed from https://stockholmcf.org/ on 15 July 2023.

Taş, Hakan. 2022. “Collective Identity Change under Exogenous Shocks: The Gülen Movement and Its Diasporization.” Middle East Critique 31:385-99.

Tee, Caroline. 2021. “The Gülen Movement: Between Turkey and International Exile.” Pp. 86-109 in Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements, edited by Muhammad Afzal Upal and Carole M. Cusack. London: Brill.

Tittensor, David. 2018. “The Gülen Movement and Surviving in Exile: The Case of Australia.” Politics, Religion, Ideology 19:123-38.

Tittensor, David. 2014. House of Service: The Gülen Movement and Islam’s Third Way. New York. Oxford University Press.

Tuğal, Cihan. 2013. “Gülenism: The Middle Way or Official Ideology.” Jadaliyya, June 5. Accessed from http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/12673/gulenism_the-middle-way-or-official-ideology on 10 July 2023.

Turam, Berna. 2006. The Politics of Engagement: Between Islam and the Secular State. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

“Turkey’s president orders closure of 1,000 private schools linked to Gülen.” 2016. The Guardian, July 23.

Yavuz, Hakan. 2013. Toward an Islamic Enlightenment: The Gülen Movement. New York. Oxford University Press.

Yavuz, Hakan. 2003. Islamic Political Identity in Turkey. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yavuz, Hakan and John Esposito, eds. 2003. Turkish Islam and the Secular State. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Yurtsever, Ali, ed. 2008. Islam in the Age of Global Challenges: Alternative Perspective of The Gulen Movement. Washington D.C.: Rumi Forum/Tuğhra Books.

Publication Date:

22 August 2014

Update:

22 July 2023

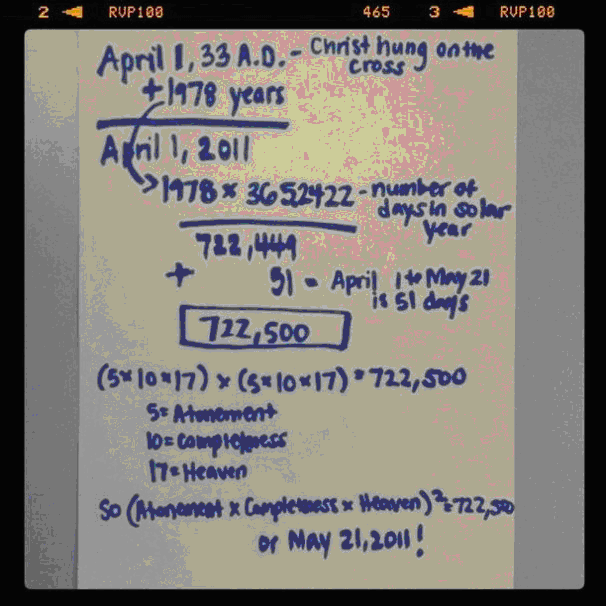

Camping’s Biblical chronology as proposed in his book, The Biblical Calendar of History, set the date of the Flood of Noah’s ark at 4990 BCE. This, along with a “calculation…derived from a bible verse equating 24 hours in God’s life with a thousand years on earth” (McQuigge 2011) led to Camping’s prediction that the end of the world would occur on May 21, 2011, exactly 7,000 years after the Flood. Similar biblical computations had previously led Camping to predict the end of the world in 1994, though he accounted for this inaccuracy on the basis that his “research was incomplete at that time” (Epstein 2011). In his more recent doomsday prophecy, Camping offered a precise, detailed forecast of the Rapture as it would occur on May 21, replete with sinister visions of a catastrophic earthquake beginning at six o’clock p.m. (drawn from Revelation 16:18), graves cracking open, the transformation of believers into “glorified spiritual bodies” (Epstein 2011), and the suffering and destruction of the rest of humanity over a span of several months. All of this would culminate in God’s obliteration of the planet on October 21, 2011. Family Radio urged believers to prepare for the end, and newspapers described adherents’ unswerving confidence in Camping’s prediction. When the expected events did not occur in the manner predicted on May 21, Family Radio issued an apology on its website. Camping has since modified his teachings: Christ’s coming on the May 21 date was “an invisible judgment day” of a purely spiritual nature, and the world will still be destroyed on October 21, 2011 (Tenety 2011).

Camping’s Biblical chronology as proposed in his book, The Biblical Calendar of History, set the date of the Flood of Noah’s ark at 4990 BCE. This, along with a “calculation…derived from a bible verse equating 24 hours in God’s life with a thousand years on earth” (McQuigge 2011) led to Camping’s prediction that the end of the world would occur on May 21, 2011, exactly 7,000 years after the Flood. Similar biblical computations had previously led Camping to predict the end of the world in 1994, though he accounted for this inaccuracy on the basis that his “research was incomplete at that time” (Epstein 2011). In his more recent doomsday prophecy, Camping offered a precise, detailed forecast of the Rapture as it would occur on May 21, replete with sinister visions of a catastrophic earthquake beginning at six o’clock p.m. (drawn from Revelation 16:18), graves cracking open, the transformation of believers into “glorified spiritual bodies” (Epstein 2011), and the suffering and destruction of the rest of humanity over a span of several months. All of this would culminate in God’s obliteration of the planet on October 21, 2011. Family Radio urged believers to prepare for the end, and newspapers described adherents’ unswerving confidence in Camping’s prediction. When the expected events did not occur in the manner predicted on May 21, Family Radio issued an apology on its website. Camping has since modified his teachings: Christ’s coming on the May 21 date was “an invisible judgment day” of a purely spiritual nature, and the world will still be destroyed on October 21, 2011 (Tenety 2011). The group’s primary ritual activity appears to be centered around preparation for the Rapture. This effort is embodied in Project Caravan, the movement’s costly campaign to spread the message that May 21, 2011 would be the Day of Judgment. Family Radio amassed millions of dollars to purchase “20,000 billboards around the world” and subsequently “launched a convoy of caravans to canvas the U.S. and Canada and warn of the impending disaster” (McQuigge 2011). Followers contributed generously to fund the project, which is financed exclusively by donations, and the group has reportedly spent millions on electronic billboards and RVs that have crisscrossed the country. Family radio spokesperson Gunther von Harringa revealed that the group members “believe this so strongly, not only are we putting our reputation on the lines, but we’re spending all our money like there is no tomorrow, because we don’t believer there will be a tomorrow” (McQuigge 2011). Members recounted pouring their savings into Family Radio’s End Times campaign, defaulting on mortgage payments, saying goodbyes to loved ones, parading through the streets with posters, and taking to the road in caravans to spread the message of the impending Day of Judgment.

The group’s primary ritual activity appears to be centered around preparation for the Rapture. This effort is embodied in Project Caravan, the movement’s costly campaign to spread the message that May 21, 2011 would be the Day of Judgment. Family Radio amassed millions of dollars to purchase “20,000 billboards around the world” and subsequently “launched a convoy of caravans to canvas the U.S. and Canada and warn of the impending disaster” (McQuigge 2011). Followers contributed generously to fund the project, which is financed exclusively by donations, and the group has reportedly spent millions on electronic billboards and RVs that have crisscrossed the country. Family radio spokesperson Gunther von Harringa revealed that the group members “believe this so strongly, not only are we putting our reputation on the lines, but we’re spending all our money like there is no tomorrow, because we don’t believer there will be a tomorrow” (McQuigge 2011). Members recounted pouring their savings into Family Radio’s End Times campaign, defaulting on mortgage payments, saying goodbyes to loved ones, parading through the streets with posters, and taking to the road in caravans to spread the message of the impending Day of Judgment.

riding in the white section of a trolley, and refusing to attend segregated schools (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). By 1900, Baker was living in Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked as a gardener and assistant preacher in a local Baptist storefront church. He attended the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 and experienced a major spiritual awakening as he spoke in tongues. For the first time he began to recognize his inner divinity and think of himself in god-like terms (Watts 1995:25). In 1907, Baker met a man named Samuel Morris, a preacher to whom Baker was drawn and who called himself Father Jehovia. Baker found the philosophy that Morris taught, that God is within each individual, to be compelling. According to some reports, Morris referred to himself as God. The two men began working together, and Baker began to refer to himself as “the Messenger,” while sharing the godship with Father Jehovia.

riding in the white section of a trolley, and refusing to attend segregated schools (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). By 1900, Baker was living in Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked as a gardener and assistant preacher in a local Baptist storefront church. He attended the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 and experienced a major spiritual awakening as he spoke in tongues. For the first time he began to recognize his inner divinity and think of himself in god-like terms (Watts 1995:25). In 1907, Baker met a man named Samuel Morris, a preacher to whom Baker was drawn and who called himself Father Jehovia. Baker found the philosophy that Morris taught, that God is within each individual, to be compelling. According to some reports, Morris referred to himself as God. The two men began working together, and Baker began to refer to himself as “the Messenger,” while sharing the godship with Father Jehovia. in a small house for several years. The Messenger took on responsibility for finding jobs for his followers, and they, in turn, returned their earnings to him. With those funds The Messenger paid for the rent, food, and living expenses. During this time, the group was growing slowly. Peninah, managed the house and prepared food for the group. At this time, or perhaps earlier as some sources suggest, The Messenger married Peninah despite his ban on marriage for his disciples. He stated that the marriage was spiritual and not sexual, as celibacy was required by the group’s moral code. It is not clear whether a marriage license was obtained. While living in New York, The Messenger decided to change his name once again. This time he assumed the name Major Jealous Devine, which was later abbreviated M.J. Devine. Subsequently, the name M.J. Devine evolved into Father Divine (2008).

in a small house for several years. The Messenger took on responsibility for finding jobs for his followers, and they, in turn, returned their earnings to him. With those funds The Messenger paid for the rent, food, and living expenses. During this time, the group was growing slowly. Peninah, managed the house and prepared food for the group. At this time, or perhaps earlier as some sources suggest, The Messenger married Peninah despite his ban on marriage for his disciples. He stated that the marriage was spiritual and not sexual, as celibacy was required by the group’s moral code. It is not clear whether a marriage license was obtained. While living in New York, The Messenger decided to change his name once again. This time he assumed the name Major Jealous Devine, which was later abbreviated M.J. Devine. Subsequently, the name M.J. Devine evolved into Father Divine (2008). Father Divine providing both economic and spiritual security for his followers. Eventually, the movement obtained multiple hotels and other businesses. His followers refurbished the buildings and then worked for no wages, blacks and whites together, relying on Father Divine’s leadership. The beginning of the Great Depression and the increasing hardships that poor blacks faced provided an opportunity for Father Divine to advocate for his egalitarian heaven on Earth (Miller 1995). The Peace Mission Movement expanded to 150 “heavenly extensions;” Peace Mission gatherings were held in Canada, Australia, and several European countries. Membership in New York and Long Island peaked at 10,000 around this time. The Peace Mission drew members from the poor black community impacted by the Great Depression, white members who were attracted by the New Thought doctrines, and blacks who had participated in the Universal Negro Improvement Association before founder Marcus Garvey’s deportation in 1927. Watts (1995:85) estimates overall movement membership in the early 1930s as between 20,000 and 30,000.

Father Divine providing both economic and spiritual security for his followers. Eventually, the movement obtained multiple hotels and other businesses. His followers refurbished the buildings and then worked for no wages, blacks and whites together, relying on Father Divine’s leadership. The beginning of the Great Depression and the increasing hardships that poor blacks faced provided an opportunity for Father Divine to advocate for his egalitarian heaven on Earth (Miller 1995). The Peace Mission Movement expanded to 150 “heavenly extensions;” Peace Mission gatherings were held in Canada, Australia, and several European countries. Membership in New York and Long Island peaked at 10,000 around this time. The Peace Mission drew members from the poor black community impacted by the Great Depression, white members who were attracted by the New Thought doctrines, and blacks who had participated in the Universal Negro Improvement Association before founder Marcus Garvey’s deportation in 1927. Watts (1995:85) estimates overall movement membership in the early 1930s as between 20,000 and 30,000. 1930s that the group adopted the name “the International Peace Mission movement.” In 1934, Father Divine, who himself had created a type of communal socialism, forged a short-lived alliance with the Communist Party in the U.S. for a time after being impressed with its commitment to civil rights.

1930s that the group adopted the name “the International Peace Mission movement.” In 1934, Father Divine, who himself had created a type of communal socialism, forged a short-lived alliance with the Communist Party in the U.S. for a time after being impressed with its commitment to civil rights. (the date is uncertain). Apparently, only a few of Father Divine’s inner circle knew of Peninah’s death, and she was quietly buried in an unmarked grave Father Divine never discussed her death, but in August 1946 he suddenly announced his marriage to a twenty-one year-old white follower, Edna Rose Ritchings, who was called Sweet Angel and had been one of his secretaries. Father Divine announced that Ritchings’ and Peninah’s spirits had joined together and thereby the two women had become one. Ritchings subsequently was known as Mother Divine within the movement. Father Divine once again emphasized that this marital union was spiritual and not sexual. This interracial marriage sparked public anger, shock among his followers, and some defections. However, she was accepted and revered within the movement. Father Divine and asserted that she was the incarnation of Peninah (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). The couple moved the headquarters to their current location, the Woodmont Estate, which is located outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1953. Mother Divine significantly aided Father Divine in managing the movement during her younger years, and as his health declined she took on many more duties.

(the date is uncertain). Apparently, only a few of Father Divine’s inner circle knew of Peninah’s death, and she was quietly buried in an unmarked grave Father Divine never discussed her death, but in August 1946 he suddenly announced his marriage to a twenty-one year-old white follower, Edna Rose Ritchings, who was called Sweet Angel and had been one of his secretaries. Father Divine announced that Ritchings’ and Peninah’s spirits had joined together and thereby the two women had become one. Ritchings subsequently was known as Mother Divine within the movement. Father Divine once again emphasized that this marital union was spiritual and not sexual. This interracial marriage sparked public anger, shock among his followers, and some defections. However, she was accepted and revered within the movement. Father Divine and asserted that she was the incarnation of Peninah (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). The couple moved the headquarters to their current location, the Woodmont Estate, which is located outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1953. Mother Divine significantly aided Father Divine in managing the movement during her younger years, and as his health declined she took on many more duties. recruitment, preferring to preserve its elite status. The few hundred members scattered around the U.S. and Europe have continued to abide by the strict moral code that Father Divine instituted. A small number of members remain at Woodmont, aiding Mother Divine in giving tours of the property and performing day-to-day managerial duties (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). Mother Divine has generally been accepted as the incarnation of Father Divine, and has been treated as such, though his immortal spirit continues to be honored (Weisbrot 1995).

recruitment, preferring to preserve its elite status. The few hundred members scattered around the U.S. and Europe have continued to abide by the strict moral code that Father Divine instituted. A small number of members remain at Woodmont, aiding Mother Divine in giving tours of the property and performing day-to-day managerial duties (Schaefer and Zellner 2008). Mother Divine has generally been accepted as the incarnation of Father Divine, and has been treated as such, though his immortal spirit continues to be honored (Weisbrot 1995). Members were taught that they possessed an inner divinity and that Christ was present in every part of every individual’s body. Father Divine was heavily influenced by writings of Robert Collier that advocate for a universal potential in humans, and that success can be realized through the use of their inner divinity. Father Divine focused on the self-image of members. A righteous individual is one with God and this requires positive thinking and an affirmative self-image. Father Divine stated, “The positive is a reality! We dispel the negative and the undesirable…” (Erikson 1977). This positive way of thinking brings the follower closer with God, and closer to the truth. Father Divine purchased copies of New Thought works and gave them to his disciples (Watts 1995). Many white followers were attracted to his movement by the New Thought teachings. Required reading for members included both the Bible and the Divine newspapers, until their publication was discontinued in 1992.