Concerned Christians

CONCERNED CHRISTIANS TIMELINE

Founder : Monte Kim Miller.1

Date of Birth : April 20, 1954 2 .

Birth Place : Burlington, Colorado 3 .

Sacred or Revered Texts : Bimonthly newsletter, Report from Concerned Christians . Our Foundation radio program. The Old Testament is also used, but their beliefs primarily deal with the New Testament.

Size of Group : There were 78 members of the group in September 30, 1998. How many perceive themselves to still be members of the group is unknown. 10

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Monte Kim Miller was born on April 20, 1954 and raised in the small farming community of Burlington, Colorado. Miller’s family did not attend church, but he claims to have converted to Christianity after listening to Bill Bright, founder and president of Campus Crusade for Christ. He allegedly worked for Campus Crusade, but no record of that work can be found. Miller received no formal theological training. Thus, he claims he avoided any “disciplining in ‘man’s’ traditions” and was able to learn solely from God. 5

Miller was an anti-cult activist in the early 1980’s, around the same time he formed Concerned Christians. He was working as a marketing executive at Proctor and Gamble at the time and he began to lecture at local Denver churches. Miller formed Concerned Christians in response to the New Age movement and his perception of anti-Christian bias in the media. His newsletter, Report from Concerned Christians focused on such topics as feminist spirituality, the Harmonic Convergence of 1987, New Age trends in the Christian church, and alternative medicine. 6

By the mid-1980s Miller’s views began to deviate from orthodox evangelical Christian doctrine and practice. It is claimed that Miller began to have conversations with God at this point, but this is disputed. By around 1988 Miller’s focus began to shift even more. This is evidenced in a series of newsletters criticizing the World-Faith movement and the Roman Catholic Church. Although this in itself is unremarkable, as many religious organizations were also voicing concern in regards to these groups, it served as a precursor to Miller’s attacks on organized Christianity.

Miller began to isolate himself starting in the early 1990’s. In 1996 he began producing a radio program entitled Our Foundation . The program was removed from the air after Miller refused to pay for air time, claiming that God had ordered him not to pay. Miller declared bankruptcy after becoming more than $600,000 in debt. He asked his followers to contribute up to $100,000 apiece. When they refused, it is alleged that he advised his followers that they were going to hell. 7

It was also during this time that Miller began to channel messages from God. His prophecies became increasing apocalyptic. He proclaimed himself to be one of the two witnesses of Revelation 11, who would be killed in Jerusalem in December 1999, and then resurrected after three days. He also prophesied that the Apocalypse would begin after Denver was to be destroyed by and earthquake on October 10, 1998. 8

Seventy-two members of the Concerned Christians group abandoned their homes on September 30, 1998 and apparently fled to Jerusalem. The alleged reason for their abrupt departure was both to avoid the destruction of Denver and also to prepare themselves to witness the coming of the Messiah in Jerusalem during the millennium. Israeli authorities raided the homes of 14 members of the group on January 3, 1999, alleging that the group was planning to commit a violent action in an attempt to instigate Christ’s Second Coming. The members were deported on January 8, 1999, and they were returned to Denver. 9

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The beliefs of the Concerned Christians group reflect those of many religious fundamentalist groups. Monte Kim Miller focuses on several key issues and is concerned primarily with the New Testament, especially the Book of Matthew. The following concepts are derived from the only known source available regarding the beliefs of this group, the transcripts of a radio program, Our Foundation , preached by Miller. There are 45 numbered programs.

First and foremost, Miller teaches about the importance of spiritual rebirth. This spiritual birth, as opposed to our natural birth, leads to eternal life. To glorify the importance of flesh is to lead a life contrary to the spirit of God. Following that, Miller preaches that humans must become meek and lowly in heart so that they can decrease themselves and Christ can increase himself in them. This suffering and the death of self (and his own ways and desires) correlates with the theme of diminishing so Christ can prosper, and this is accomplished through the Holy Spirit.

Through this decreasing/increasing of the self and Christ and the concept of “cross- carrying” (the idea of suffering identified with Christ bearing the cross), the fruits of the Holy Spirit can be attained. When it is no longer the self that lives, but Christ within the self, it is then that the fruit of the Holy Spirit can be manifested. The fruits of the Spirit include meekness, temperance, longsuffering, gentleness, love, joy, peace, and goodness. Faith is also a fruit of the Spirit, but more importantly it is the means by which these fruits can be achieved.

Humility and self-denial are the next two issues dealt with in the radio programs. Humility is produced by faith, and humility is a centerpiece of each fruit of the spirit. Christians are to humble themselves before one another and also before non- believers. Christians are not to attempt to achieve ruler ship status over the governments of the world during this age (the present). This is the age for humility, not reigning over the fallen world system. Miller believes that the Heavenly Kingdom Teachings are what Christians should live by, and they include:

By denying ourselves,

Carrying our crosses,

Being humble before others, and

Living in Faith.

One cannot abide by these teachings unless the Holy Spirit is in the heart. These teachings to Miller represent the divine edict to turn the other cheek and to love your enemies. It is this concept that is later expounded on it great detail in future programs. Miller’s focus in the programs numbered 10-20 is on self-denial and its consequences.

One should submit to the Holy Spirit and deny oneself. Men who do not know Jesus Christ pursue self; they pursue their own lives and dreams. They pursue the desires of their flesh, and these are the fruits of self-will. The fruits of the Spirit come from self-denial – and that self-denial is a result of the giving up of your own life for the pursuit of Christ’s. One must ignore the earthly kingdom’s “wisdom of this world” because it will lead to the pursuit of self and the fallen natural man. One must strive at all costs to avoid this downfall. The fallen natural man, for example, will take revenge when wronged. Miller then describes the various characteristics ascribed to the self, such as selfishness, self-importance, self-centered, self-serving, self-interest, self-love, and self-pity, among a few.

Miller contends that the only positive aspect of self is self-improvement, which comes about only through a denial of self (a “death to self”) and a subsequent victory in Jesus Christ. There should be no self-defense, even in the example of slanderous accusations are made against one’s nature. Like Christ on the cross, one should merely accept those accusations and forgive his enemies. Along these lines, Miller challenges people to:

Bless them that curse us,

Do good to them that hate us,

Pray for them which despitefully use us.

The next issue that Miller addresses is resistance to evil. He argues that true believers should not resist evil, but should resist Satan. Consequently, Miller argues that one is in fact resisting Satan when one refuses to resist the evil perpetrated by those who do not have Jesus Christ in their lives, and who are Satan’s agents in the flesh. Miller contends that any form of resistance to evil, even non-violent (as demonstrated in the actions of Ghandi and Martin Luther King, Jr.,) is unbiblical.

The rest of Miller’s sermons are devoted to the transition from the Old Testament rule of law to the New Testament world of grace.

One should not merely see God’s grace directed to the believer, but one should see God’s grace shining through the believer. One is not to render judgment and attempt to punish non-believing sinners according to Old Testament law, because the new covenant is stronger than the old.

Miller’s emphasis in the last sermons is to establish the idea that believers not challenge government, or attempt to create laws that would punish sinners, but rather to not resist their evil, because one had no legitimate right to judge non-believers.

Like Christ, who came to earth without judging but only to save, believers should try to offer the non-believer eternal life through Jesus Christ, in the same spirit that Christ saved the world. Miller cautions his listeners against the easy trap of a “common religious purpose”, which serves to bring together true believers into deception and alliance with those who are religious but do not truly follow Jesus Christ into the resistance of evil in society. This deception can lead a believer to think is acceptable to resist evil in order to make society more righteous. An example of this is an anti-abortion law. Miller argues that it is not the place of believers to make these laws, because that is an example of resistance to evil.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

“There’s a gulf of Biblical dimensions between what Monte Kim Miller preaches on tape and what some have heard firsthand” 11 .

So begins an article in the Denver Rocky Mountain News , and so also begins the difficulty of distinguishing and discerning the truth from opinion, not only in this article but also all articles written about the Concerned Christians. There most certainly is a discrepancy between the written and/or oral teachings of Monte Kim Miller and the accounts given by family, friends, former members, and self proclaimed “cult experts”. While there doesn’t seem to be any immediate consequences arising from this simple fact, complexities arise because only one faction of this divide is talking to the media – and it isn’t Mote Kim Miller and his followers.

A careful examination of the archive of newspaper articles written about the Concerned Christians, suggests that local newspapers have been less than objective. The statistics that follow are derived from the archives of the Denver Post – I have also read through all of the articles from the Rocky Mountain News and found that the articles presented in it follow the trend that is illustrated below, therefore I have chosen to only focus on one newspaper for the sake of clarity.

There were 39 total articles published on the subject of the Concerned Christians between October 7, 1998 and January 3, 2000. In those articles there were 57 sources quoted. By calculating the number of times any given source was quoted, I concluded there are 132 “quotes” in the 39 articles. A few persons accounted for many of the quotes. To clarify, a quote is not calculated by ascertaining the number of times a certain person spoke throughout the same article, but rather if that person is quoted at least once in the article, that is considered a “quote” for him or her. The “quote” number ascribed to a person or group is the number of times that person or group was cited as a source in the articles. The majority of these sources (35) were quoted only once. The breakdown of the sources is as follows:

There were 22 family members or friends quoted. These family members and friends accounted for 52 “quotes”.

There were 5 anonymous sources quoted. These sources accounted for 10 “quotes”.

There were 13 “official” sources quoted. These sources accounted for 15 “quotes”. Of these 13 “official” sources, 9 issued neutral statements regarding Concerned Christians, 3 issued what can be considered negative statements, and 1 issued a positive statement on their behalf.

Perhaps most interestingly, there were 3 anti-cult activists quoted as sources, but between the three of them they make up 35 “quotes”. That is almost 1/3 of the quotes attributed to 3 people.

Family spokespersons

Among the family members and friends portion, the most often quoted include John Weaver, Sherry Clark, Jennifer Cooper and Del Dyck.

John Weaver is the father of Nicolette Weaver, an outspoken critic of the group who falls under both the family member and former member rubric. Nicolette’s mother, Jan Cooper, is believed to be a high-ranking member of the group and Nicolette has testified that her mother often told her of the short time they had left on earth and that if directed by Miller, she would kill Nicolette. 12 John Weaver often makes highly derogatory statements regarding the group, including claims that the group demands members surrender their lives to Miller’s dictums, charges that Miller is a “con” and “biblical illiterate” 13 and beliefs that Miller is like Almighty God to members and has the ability to plot his own martyrdom and lead them to mass suicide.

Sherry Clark is often the unofficial spokeswoman of the family members, and she testifies that when she met with Miller he told her the only way to be saved was to write a check for $70,000 while simultaneously twisting his mouth and talking in a “weird voice” 14 . She has also questioned his ability to make choices. She is the primary source for characterizing the feelings of family members regarding the cult – she has said that the experience has tragically divided and pulled families apart. 15

Jennifer Cooper is the daughter of John Cooper, who is the husband of Jan Cooper and who also is believed to be the primary financer of the group’s activities. Jennifer successfully petitioned for a conservatorship for control of her father’s estate. To do so, she had to convince a judge that her father was unable to make financial decisions for himself. Cooper claimed that her father had been “brainwashed” and was acting out of character. 16 She feels as though Miller is only after her father’s money.

Lastly, Del Dyck only made the news around January 7, 1999, when 14 of the members were being deported from Israel back to the United States. Knowing his son would be among the members returning, he flew to Denver and met every incoming flight from Tel Aviv – to no avail. These four people are characteristic of the family member’s testimonies as a whole. Generally, family and friends express frustration, anger, sadness, and hurt, which is not surprising. Their sentiments, however, cannot be considered objective.

The anti-cult experts

It is understandable that a group that believes the media to be biased against them would be reluctant to respond to requests for interviews. How much effort the Denver media made to speak with group members is not known, but there are no quotes from members of Concerned Christians in the news stories I examined. One would expect the media would call upon family members for perspective about a group that was believed to be controversial even before they disappeared. If this is understandable, it is also clear that the media have not sought more objective or neutral perspective. Indeed, as I noted above, three local anti-cult activists account for approximately one-third of all quotes. To more clearly understand the context of the quotes used by the media, it may be instructive to offer brief sketches about the three most frequently cited “experts.” In each instance, it is clear that these “experts” are working with presuppositions that preclude much objective analysis.

Bill Honsberger is referred to in many news articles as a “local cult expert.” He is, in fact, a Christian missionary with the Baptist church. Honsberger virulently attacks the legitimacy of both Miller and his followers. He is quoted in 15 of the 39 articles. Some of his more aggressive accusations include:

“Miller is liable to do something bizarre to ensure his place in history” 23 .

“[H]e has that much control. You question him, you question God” 24 .

Honsberger also believes Miller’s divine edicts could turn violent, and that he [Miller] is capable of ordering a group suicide. Honsberger feels that Miller would not mind dying if his prophetic role in the universe was intact. He further considers Miller to be a danger both to those in his group and those around him. Miller’s power, Honsberger asserts, lies in his ability to convince his followers to abandon their families and isolate them completely. 25

Honsberger has also said that Miller has threatened to kill him and casts him as the Antichrist. 26 What is more interesting than all of these characterizations, however, is the fact that Honsberger is one of the only people who can testify to the beliefs of the Concerned Christians. He is often called upon to present their beliefs to the media. This can raise some concerns, as will be discussed later, with the validity of the presentation of their beliefs.

Mark Roggeman , tied with Honsberger as the most quoted source about Concerned Christians, is a Denver police officer who “tracks cults in his spare time”. 27 Roggeman often issues statements of a rather generic sort, usually he comments on the status of family members or general concepts of the members’ beliefs. While he may not provide harsh attacks on the cult members, Roggeman is clearly anti-cult. He was indicted on June 11, 1981 for second degree kidnapping and false imprisonment. He was charged with forcibly kidnapping Emily Dietz and holding her against her will for nearly two weeks before she finally escaped by jumping from a second story window in the middle of the night. 28 It is clear that Roggeman should not be considered an unbiased source.

Hal Mansfield is the director of the Religious Movement Resource Center. The Center is concerned with dissuading people from entering into what they term “destructive cults”. They define a destructive cult as “an organization that inhibits individual freedom of thought through the use of violence, deception and mind control”. 29 A destructive cult is not defined on the basis of its belief system or theology, but rather the dynamics of group organization. There are two different methods by which a group is deemed to be a “destructive cult”. First, from “Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism” by Dr. Robert Jay Lifton, there are eight points of mind control. They are:

Milieu control

Mystical manipulation

The demand for purity

The cult of confession

Sacred science

Loading the language

Doctrine over person

Another guide used by the Center is the Cult Danger Evaluation Frame developed is P. E. I. Bonewits. This evaluation uses a ten-point scale. The areas rated are:

Internal control

Wisdom claimed

Wisdom credited

Dogma

Recruiting

Front groups

Wealth

Political power

Sexual manipulation

Censorship

Dropout control

Endorsement of violence

Paranoia

Grimness

Both of these resources are considered by scholars of religious movements to have dubious validity.

Mansfield is the most outspoken and derogatory of the anti-cultists. He often compares the Concerned Christians to the members of Heaven’s Gate, Jonestown, and the Branch Davidians. He has said he considers the Concerned Christians a “very dangerous group”, 32 .and charges that Miller is wrapped up in a power trip. Hansfield also has made assumptions about the violent tendencies of the group. When there were no weapons found on the members after a raid on their house in Jerusalem, Mansfield indicated that weapons were readily accessible to the members. “Come on, that’s the Middle East. You can go across the border and come back with an armful of AK-47s,” he said. 33

Mansfield has also alluded to previous instances of Miller’s “violent tendencies,” but there is no verifiable evidence to support his statements.

Official sources

The “official” sources that were quoted usually offered neutral statements, and many times were not directed at Concerned Christians specifically but rather at new religious movements generally. There were, however, some interesting contradictions among these sources. Consider the following:

Linda Menuhin, and Israeli police spokeswoman, said that Israel would act vehemently against any attempt of extremist groups that distract the arrival of Christians. 17

Yair Yizahki, the Jerusalem police commander, also said that the deportation was merely a reaction to the need to fight for freedom of religious worship. 18 This raises an interesting question – how can barring the existence of one religious group promote the freedom of others? This might follow only if, as alleged by the Israeli police, the members of that group are plotting violence.

Brig. Gen. Elihu Ben-Ohn, the national police spokesman, said that the members of Concerned Christians planned to carry out violent and extreme acts in the streets of Jerusalem. 19

There were not, however, any charges filed. John Russel, a spokesman for the U.S. Justice Department said there were no charges against the deportees and Bill Carter, a FBI spokesman, said no action was going to be taken against the members. 20

A police source said it was “not in the public interest to spend the time and money to try these men in Israel” 21 .

David Parsons, the director of the International Christian Embassy in Jerusalem believed the action was overzealous and was just an excuse to get them “out of Israel’s hair”. 22

Many have argued that Israel was acting in order to defer other “extremist” groups from causing trouble. The Concerned Christians were used to make an example.

Conclusions

There is no question that there is an obvious discrepancy between the theology presented in the Our Foundation radio program and the reports of mass suicide and violent tendencies, apocalyptic predictions, “God-voice”, and anti-government rhetoric.

The only testimony relating Miller and his followers to the extremist ideas presented in all of the news articles are former members, family members, and anti-cult activists. The problem at hand is assessing the objectivity of these sources and getting to the truth of what really happened.

An issue of considerable importance is why the media so readily adopted these stories as the truth, and why the media seemingly made such little effort to engage Miller and current members. In the early articles about the Concerned Christians, Bill Honsberger was the only person who could attest to Monte Kim Miller’s prophesies and “extreme” beliefs. Consequently, the statements about these beliefs were always credited to Honsberger. For example, “Honsberger said that Miller teaches Concerned Christians members that he is God and prophesies he will die in the streets of Jerusalem in December 1999, only to rise again in three days. He also believes the apocalypse will strike Denver on Saturday,” 34 .

However biased the presuppositions of the source, this is probably proper journalism. Around November, 1998 the attribution “Honsberger said” began to be left out of stories. So, for example, we read “Miller, who considers himself the last prophet of God, has said he will die on the streets of that ancient city [ Jerusalem] in December 1999 and be resurrected three days later” 35 . This leads the reader to the impression that these statements are a proven fact, when in reality that can only be attributed to one anti-cultist.

The group known as Concerned Christians remains shrouded in mystery. Monte Kim Miller seems clearly to be a charismatic leader who holds (or has held) considerable influence over his small group of followers. Whether Miller and his followers are dangerous to themselves and others is not clear. The uncertainty pivots very substantially on the credibility of the evidence about them.

We have essentially no first hand information about the group — only accounts of a few persons who claim some level of involvement in the group in the past. And, at this point, we have little basis for assessing the reliability of their accounts.

What we do know is that a small number of zealous anti-cultists have waged an assault on the Concerned Christians, and these attacks have been transmitted uncritically by the mass media. I have focused on the Denver media, but the national media in the U.S., as well as well as Israel and Great Britain, have largely accepted the anti-cult presuppositions.

Religious movements are the product of human initiatives and, thus, are subject to all the shortcomings of human beings. Monte Kim Miller may turn out to be a real scoundrel, but that is not clear to me at this point.

As a student of religious movements, I am struck by how closely this case seems to conform to the gulf between public perceptions and the objective reality of so many other religious movements in the course of American history.

REFERENCES

Abanes, Richard. 1998. End-time Visions: The Road to Armageddon? New York: Four Walls Eight Windows.

Elliot, Paul. 1998. Warrior Cults: A History of Magical, Mystical, and Murderous Organizations. London: Blandford.

Hubback, Andrew. 1996. Prophets of Doom: The Security Threat of Religious Cults. London: Alliance Publishers for the Institute for European Defence and Strategic Studies.

Lewis, James R. 1999. Peculiar Prophets: A Biographical Dictionary of New Religions. St Paul, Minn.: Paragon House.

WILSON, Bryan, and Jamie Cresswell. eds. 1999. New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response. London; New York: Routledge.

Weber, Eugen Joseph. 1999. Apocalypses: Prophecies, Cults, and Millennial Beliefs Through the Ages. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

References

- www.watchman.org/concernedchristianspro.htm

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. and www.religioustolerance.org

- www.watchman.org

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- www.religioustolerance.org

- Rocky Mountain News , December 13, 1998.

- Denver Post , January 4, 1999.

- Denver Post , November 1, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Denver Post , January 10, 1999.

- Denver Post , January 9, 1999.

- Denver Post , January 4, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Denver Post , January 4, 1999.

- Denver Post , January 6, 1999.

- Denver Post , January 7, 1999.

- Denver Post , January 5, 1999.

- Denver Post , October 7, 1998.

- Ibid.

- Denver Post , October 8, 1998.

- Denver Post , January 9, 1999.

- Denver Post , October 7, 1998.

- http://cultawarenessnetwork.org/cani1/page09.html

- http://lamar.colostate.edu/~ucm/rmrc1.htm

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Denver Post , October 8, 1998.

- Denver Post , January 4, 1999.

- Denver Post , October 7, 1998.

- Denver Post , November 9, 1998.

- Denver Post , January 18, 1999.

- Ibid.

- http://www.jeack.com.au/~parkdale/cultaware_unzipped/intro.htm

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

Created by Kacey Chappelear

For Soc 257: New Religious Movements

University of Virginia

Spring Term 2000

Last modified: 04/19/01

CONCERNED CHRISTIANS VIDEO CONNECTIONS

became so displeased with his son for claiming knowledge of secret teachings, that in a letter believed to have been written in 1256, he disowned him saying, “I no longer consider you my son.” Shinran, to assure his disciples in a distant province that he had not given his son a secret teaching, wrote the following in a letter:

became so displeased with his son for claiming knowledge of secret teachings, that in a letter believed to have been written in 1256, he disowned him saying, “I no longer consider you my son.” Shinran, to assure his disciples in a distant province that he had not given his son a secret teaching, wrote the following in a letter: the most prominent figure in Shin history after Shinran, repeatedly criticized those who claimed knowledge of secret teachings. In one of his pastoral letters in 1474 he wrote “The secret teachings (hiji bōmon) that are widespread in Echizen province are certainly not the Buddha-dharma; they are deplorable, outer (non-Buddhist) teachings. Relying on them is futile; it creates karma through which one sinks for a long time into the hell of incessant pain” (Ofumi 2.14; translated in Rogers and Rogers 1991).

the most prominent figure in Shin history after Shinran, repeatedly criticized those who claimed knowledge of secret teachings. In one of his pastoral letters in 1474 he wrote “The secret teachings (hiji bōmon) that are widespread in Echizen province are certainly not the Buddha-dharma; they are deplorable, outer (non-Buddhist) teachings. Relying on them is futile; it creates karma through which one sinks for a long time into the hell of incessant pain” (Ofumi 2.14; translated in Rogers and Rogers 1991).

Alberta Province from the U.S in 1882, and American open-range cattle ranching soon was a favored style in the industry (Breen 1901-1910). Calgary became the hub of the Canadian cattle industry. However, just as in the U.S., it was not long before fenced ranches replaced open range and the role of the cowboy diminished. As in the U.S. cowboy culture continued through rodeo culture. By the middle of the nineteenth century rodeos became popular as cowboys roped cows and broke in wild horses in order to win cash prizes, engage in sport, and provide entertainment for growing rodeo audiences (Fleck 2003). In 1886, the forerunner of The Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, The Calgary and District Agricultural Society, took place. The first Calgary Exhibition and Stampede was held in 1923. The term “rodeo” only gradually came into use, and it was only in the 1940s that events were referred to as rodeos by participants. The Canadian Cowboys’ Association was created in 1963. It covered three provinces at that time: Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan; Ontario was included in 2005 ( Leduc Black Gold Pro Rodeo & Exhibition 2014) .

Alberta Province from the U.S in 1882, and American open-range cattle ranching soon was a favored style in the industry (Breen 1901-1910). Calgary became the hub of the Canadian cattle industry. However, just as in the U.S., it was not long before fenced ranches replaced open range and the role of the cowboy diminished. As in the U.S. cowboy culture continued through rodeo culture. By the middle of the nineteenth century rodeos became popular as cowboys roped cows and broke in wild horses in order to win cash prizes, engage in sport, and provide entertainment for growing rodeo audiences (Fleck 2003). In 1886, the forerunner of The Calgary Exhibition and Stampede, The Calgary and District Agricultural Society, took place. The first Calgary Exhibition and Stampede was held in 1923. The term “rodeo” only gradually came into use, and it was only in the 1940s that events were referred to as rodeos by participants. The Canadian Cowboys’ Association was created in 1963. It covered three provinces at that time: Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan; Ontario was included in 2005 ( Leduc Black Gold Pro Rodeo & Exhibition 2014) . and Australia. The cowboy church movement is non-denominational, though many churches are affiliated with particular traditional denominations. There are over 800 cowboy churches in the U.S. Cowboy Church of Ellis County in Waxahachie, Texas, which was established in 2005, is reputed to be the world’s largest cowboy church. Its membership has grown to nearly 2,000, with over 1,700 in regular attendance. There is a Monday evening service to accommodate those who attend rodeos and competitions on weekends (Bromley and Phillips 2013).

and Australia. The cowboy church movement is non-denominational, though many churches are affiliated with particular traditional denominations. There are over 800 cowboy churches in the U.S. Cowboy Church of Ellis County in Waxahachie, Texas, which was established in 2005, is reputed to be the world’s largest cowboy church. Its membership has grown to nearly 2,000, with over 1,700 in regular attendance. There is a Monday evening service to accommodate those who attend rodeos and competitions on weekends (Bromley and Phillips 2013). Clearwater Cowboy Church in Caroline. Probably the best known Canadian cowboy church in Canada is the Cowboy Trail Church in Cochrane, which was founded by Bryn Thiessen in 2005. Thiessen and his four sisters were brought up in a Mennonite family in Gamble Flats. He and his wife have three children and own the 2,500 Helmer Creek Ranch near Sundre where he raises horses and cattle and she raises Border Collies (Toneguzzi 2014). Thiessen is also a noted cowboy poet.

Clearwater Cowboy Church in Caroline. Probably the best known Canadian cowboy church in Canada is the Cowboy Trail Church in Cochrane, which was founded by Bryn Thiessen in 2005. Thiessen and his four sisters were brought up in a Mennonite family in Gamble Flats. He and his wife have three children and own the 2,500 Helmer Creek Ranch near Sundre where he raises horses and cattle and she raises Border Collies (Toneguzzi 2014). Thiessen is also a noted cowboy poet. want to know a wishy-washy gospel. They want the truth, worded in a way they can understand it. My job is to put the Gospel in a palatable form” (Stephen 2007 ). For that reason Thiessen tries to keep his preaching simple. As he states it, “Mine’s non-negotiable,” he said. “Tell the truth and serve good coffee. Offer opportunities for fellowship. It’s simple, there’s no need to water down the gospel” (Junkin 2011).

want to know a wishy-washy gospel. They want the truth, worded in a way they can understand it. My job is to put the Gospel in a palatable form” (Stephen 2007 ). For that reason Thiessen tries to keep his preaching simple. As he states it, “Mine’s non-negotiable,” he said. “Tell the truth and serve good coffee. Offer opportunities for fellowship. It’s simple, there’s no need to water down the gospel” (Junkin 2011). at the Cochrane Ranche House, a onetime cattle ranch turned convention center. The overall congregation numbers around 300, with about 100 on average attending the weekly services. In addition to its regular services, the church also performs marriages, baptisms and funerals, all in with a western flavor. The church is supported through donations by the congregation. However, the church does not pass a collection plate. Rather, those attending services are invited to drop donations in two cowboy boots that are placed at the church door.

at the Cochrane Ranche House, a onetime cattle ranch turned convention center. The overall congregation numbers around 300, with about 100 on average attending the weekly services. In addition to its regular services, the church also performs marriages, baptisms and funerals, all in with a western flavor. The church is supported through donations by the congregation. However, the church does not pass a collection plate. Rather, those attending services are invited to drop donations in two cowboy boots that are placed at the church door. some way, they are sometimes criticized for their western orientation. The critique is that the style of the church becomes more important than the substance of the doctrine (wayoflife.org 2012). This appears to be less an issue in Canada than it is in the U.S. The more significant challenge to cowboy churches, like Cowboy way, is maintaining the kind of commitment from second generation members that energizes the founding generation. If commitment erodes or novelty wears off, cowboy churches may lose the luster they currently enjoy.

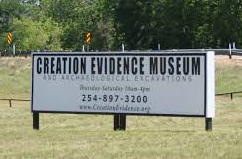

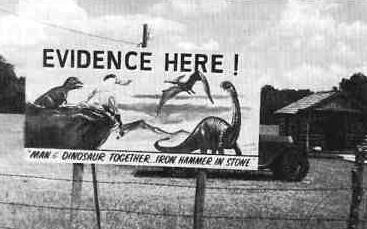

some way, they are sometimes criticized for their western orientation. The critique is that the style of the church becomes more important than the substance of the doctrine (wayoflife.org 2012). This appears to be less an issue in Canada than it is in the U.S. The more significant challenge to cowboy churches, like Cowboy way, is maintaining the kind of commitment from second generation members that energizes the founding generation. If commitment erodes or novelty wears off, cowboy churches may lose the luster they currently enjoy. with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world ( Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). One of the more significant creationist museums in the U.S. is the Creationist Evidence Museum.

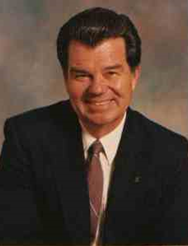

with creationism, in part due to the struggles over a variety of issues (e.g., science education, sex education, prayer in schools) in the public school system. One outgrowth of these struggles has been the formation of a variety of museums, research institutes, and foundations defending the biblical creation narrative (Numbers 2006; Duncan 2009). Creationist museums are found primarily in the United States, but there is a sprinkling of such museums around the world ( Simitopoulou and Xirotitis 2010). One of the more significant creationist museums in the U.S. is the Creationist Evidence Museum. Baugh was ordained as a minister in the conservative Baptist Bible Fellowship denomination. In 1968, he founded Calvary Heights Baptist Church in East St. Louis, Illinois and then during the 1970s founded International Baptist College there (Henry 1996).

Baugh was ordained as a minister in the conservative Baptist Bible Fellowship denomination. In 1968, he founded Calvary Heights Baptist Church in East St. Louis, Illinois and then during the 1970s founded International Baptist College there (Henry 1996). strong creationist position gradually. He initially held both biblical and “atheistic” (evolutionist) views simultaneously. He initially was a “theistic evolutionist.” He believed that there was a God of creation who Himself created the lowest life forms and then put in place the process of evolution: “It means that there is a God superintending all the universe, but he developed man through the lower life systems in a progressive, evolutionary epoch” (Henry 1996). It was his experience excavating limestone formations along the Paluxy River that converted him into a strong creationist. In the course of his excavations, he discovered in the context of what was an ancient limestone formation (in situ) containing what he believed to be a perfect human footprint. He recalled that “It blew my mind. My explanation for my origins had been blown. If man and dinosaur had existed contemporaneously in the fossil record, that meant that the whole fossil record had to be recent in origin,” he says. “I had to examine my own philosophical posture. That was traumatic. It was exhilarating, but traumatic” (Henry 1996). Baugh subsequently authored a book, Dinosaur: Scientific Evidence that Dinosaurs and Men Walked Together in which he presented the evidence produced from his excavations (Baugh 1987).

strong creationist position gradually. He initially held both biblical and “atheistic” (evolutionist) views simultaneously. He initially was a “theistic evolutionist.” He believed that there was a God of creation who Himself created the lowest life forms and then put in place the process of evolution: “It means that there is a God superintending all the universe, but he developed man through the lower life systems in a progressive, evolutionary epoch” (Henry 1996). It was his experience excavating limestone formations along the Paluxy River that converted him into a strong creationist. In the course of his excavations, he discovered in the context of what was an ancient limestone formation (in situ) containing what he believed to be a perfect human footprint. He recalled that “It blew my mind. My explanation for my origins had been blown. If man and dinosaur had existed contemporaneously in the fossil record, that meant that the whole fossil record had to be recent in origin,” he says. “I had to examine my own philosophical posture. That was traumatic. It was exhilarating, but traumatic” (Henry 1996). Baugh subsequently authored a book, Dinosaur: Scientific Evidence that Dinosaurs and Men Walked Together in which he presented the evidence produced from his excavations (Baugh 1987). The museum space remains too limited to adequately display range of artifacts necessary to support its basic premise. Baugh claims to have located and excavated 475 dinosaur footprints along with 86 human footprints. The museum features exhibits such as a painting of a baby playing alongside, a painting of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, a videotaped lecture titled “Creation in Symphony,” the fossil collection gathered from the Glen Rose area, and, somewhat inexplicably, a statue of legendary Dallas football coach Tom Landry.

The museum space remains too limited to adequately display range of artifacts necessary to support its basic premise. Baugh claims to have located and excavated 475 dinosaur footprints along with 86 human footprints. The museum features exhibits such as a painting of a baby playing alongside, a painting of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, a videotaped lecture titled “Creation in Symphony,” the fossil collection gathered from the Glen Rose area, and, somewhat inexplicably, a statue of legendary Dallas football coach Tom Landry. New Guinea in search of living pterodactyls. Baugh reports that five colleagues have spotted the flying dinosaurs, “but all the sightings were made after dark, and we were not able to capture the creatures” (Powers 2005; Moore 2009).

New Guinea in search of living pterodactyls. Baugh reports that five colleagues have spotted the flying dinosaurs, “but all the sightings were made after dark, and we were not able to capture the creatures” (Powers 2005; Moore 2009). program, Creation in the 21st Century on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. During the 1990s, he also appeared on televangelist Kenneth Copeland’s television program in a series, Evidences of Creation, which featured some of Baugh’s most extreme claims and explanations ( Scaramanga 2012). In 1996, NBC broadcasted a one-hour special program, hosted by actor Charlton Heston ,”The Mysterious Origins of Man,” that featured Baugh’s claims. The NBC program drew intense opposition from mainstream scientists and skeptics. One review concluded that “Rather than being an objective documentary on human origins, or legitimate scientific debate about the subject, the show promoted many unfounded and pseudoscientific claims, presented a very misleading picture of the way science works, and largely ignored what mainstream scientists have to say on these subjects (Kuban 1996; see also Thomas 1996).

program, Creation in the 21st Century on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. During the 1990s, he also appeared on televangelist Kenneth Copeland’s television program in a series, Evidences of Creation, which featured some of Baugh’s most extreme claims and explanations ( Scaramanga 2012). In 1996, NBC broadcasted a one-hour special program, hosted by actor Charlton Heston ,”The Mysterious Origins of Man,” that featured Baugh’s claims. The NBC program drew intense opposition from mainstream scientists and skeptics. One review concluded that “Rather than being an objective documentary on human origins, or legitimate scientific debate about the subject, the show promoted many unfounded and pseudoscientific claims, presented a very misleading picture of the way science works, and largely ignored what mainstream scientists have to say on these subjects (Kuban 1996; see also Thomas 1996). controversy. Some major sources of controversy in the Creationist Evidence Museum case have been Baugh’s educational claims and credentials and the validity of the artifacts presented to support the creationist case.

controversy. Some major sources of controversy in the Creationist Evidence Museum case have been Baugh’s educational claims and credentials and the validity of the artifacts presented to support the creationist case. assessment of the mantracks debate, Hastings asserted: “ To conclude that there are no mantracks in Cretaceous limestone along the Paluxy River in Texas is to take no necessary ideological stand; it merely is stating matter-of-factly the results of an evidence-based scientific position. From a variety of viewpoints among the careful and probing mantrack investigators came our common scientific conclusions. That variety includes both conservative and liberal Christianity, atheistic humanism, and agnostic skepticism. Though we differed on some details of interpretation, we have come to the same or very similar overall conclusions concerning creationist mantrack claims along the Paluxy. The absence of mantracks is not necessarily a pro-evolutionary statement, although none of the research in pursuit of them does harm to modern evolutionary conclusions. Nor is it anti-creationist for the myriad of philosophical and theological positions embodying the concept of a Creator. It is, however, a devastating indictment against scientifically irresponsible claims fueled by an anti-evolutionary zeal notable among many fundamentalist Christian believers – a zeal sufficient to obscure or diminish sensitivity to the scientific irresponsibility of the claims” (Hastings 1988; see also Kuban 2010). It is also worth noting that the expansive Dinosaur Valley State Park, which is just a short distance from the Creationist Evidence Museum, has yielded thousands of dinosaur tracks along the Paluxy, but no contemporaneous human footprints ( Henry 1996; Moore 2009). It does not help Baugh’s case that there have been some admissions of deliberate fabrication of artifacts (Kennedy 2008).

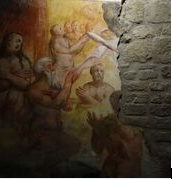

assessment of the mantracks debate, Hastings asserted: “ To conclude that there are no mantracks in Cretaceous limestone along the Paluxy River in Texas is to take no necessary ideological stand; it merely is stating matter-of-factly the results of an evidence-based scientific position. From a variety of viewpoints among the careful and probing mantrack investigators came our common scientific conclusions. That variety includes both conservative and liberal Christianity, atheistic humanism, and agnostic skepticism. Though we differed on some details of interpretation, we have come to the same or very similar overall conclusions concerning creationist mantrack claims along the Paluxy. The absence of mantracks is not necessarily a pro-evolutionary statement, although none of the research in pursuit of them does harm to modern evolutionary conclusions. Nor is it anti-creationist for the myriad of philosophical and theological positions embodying the concept of a Creator. It is, however, a devastating indictment against scientifically irresponsible claims fueled by an anti-evolutionary zeal notable among many fundamentalist Christian believers – a zeal sufficient to obscure or diminish sensitivity to the scientific irresponsibility of the claims” (Hastings 1988; see also Kuban 2010). It is also worth noting that the expansive Dinosaur Valley State Park, which is just a short distance from the Creationist Evidence Museum, has yielded thousands of dinosaur tracks along the Paluxy, but no contemporaneous human footprints ( Henry 1996; Moore 2009). It does not help Baugh’s case that there have been some admissions of deliberate fabrication of artifacts (Kennedy 2008). afterlife became increasingly specific due to a number of cultural shifts. One particularly important shift was the evolution of the concept of justice; punishments for crimes began to be tailored to individual circumstances. This concept eventually extended into the afterlife and a person’s fate after death reflected the magnitude of his or her sins. This was accomplished through the conception of a third place, other than heaven and hell. It was a temporary place for punishment and atonement thought to be adjacent to hell. All souls marred by sin were believed to go there for a time that corresponded to the number and severity of an individual’s sins before being admitted into heaven. The place was called “purgatory” [Image at right is Fresco of souls in purgatory], and the concept was formally accepted as doctrine in 1274 at the second Council of Lyons.

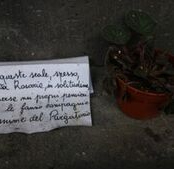

afterlife became increasingly specific due to a number of cultural shifts. One particularly important shift was the evolution of the concept of justice; punishments for crimes began to be tailored to individual circumstances. This concept eventually extended into the afterlife and a person’s fate after death reflected the magnitude of his or her sins. This was accomplished through the conception of a third place, other than heaven and hell. It was a temporary place for punishment and atonement thought to be adjacent to hell. All souls marred by sin were believed to go there for a time that corresponded to the number and severity of an individual’s sins before being admitted into heaven. The place was called “purgatory” [Image at right is Fresco of souls in purgatory], and the concept was formally accepted as doctrine in 1274 at the second Council of Lyons. practice. It was an individualistic, results-based style of worship that coexisted with belief in folk-magic and witchcraft, especially among the lower classes. Specific icons of the Madonna, as well as the relics of saints appeared to be venerated by the laity in the orthodox way (by praying with the icon or relic, not to it) but these prayers were, in practice, said to the icon or saint. In turn these images and objects were expected to use their supernatural powers to aid the venerator. When prayers were answered, the person who made the request would bring a token of gratitude, called an ex voto, to the shrine where the request was made [Image at right]. In orthodox Catholicism, ex votos are offered freely in thanksgiving; however, in Neapolitan folk Catholicism, these gifts establish a unique, reciprocal relationship between the individual and the tangible sacred object (the icon or relic). From this moment of reciprocity on, the relationship was expected to be mutually beneficial and could be reversed at any time should the sacred object fail to perform or the venerator fail to express appropriate gratitude.

practice. It was an individualistic, results-based style of worship that coexisted with belief in folk-magic and witchcraft, especially among the lower classes. Specific icons of the Madonna, as well as the relics of saints appeared to be venerated by the laity in the orthodox way (by praying with the icon or relic, not to it) but these prayers were, in practice, said to the icon or saint. In turn these images and objects were expected to use their supernatural powers to aid the venerator. When prayers were answered, the person who made the request would bring a token of gratitude, called an ex voto, to the shrine where the request was made [Image at right]. In orthodox Catholicism, ex votos are offered freely in thanksgiving; however, in Neapolitan folk Catholicism, these gifts establish a unique, reciprocal relationship between the individual and the tangible sacred object (the icon or relic). From this moment of reciprocity on, the relationship was expected to be mutually beneficial and could be reversed at any time should the sacred object fail to perform or the venerator fail to express appropriate gratitude. doctrine does not allow the souls in purgatory the power to bestow favors on the living, nor does it believe they ought to be venerated as one would venerate saints or the Virgin Mary. For orthodox Catholics, the relationship between the living and souls in purgatory is strictly one-sided and charitable: prayers said by the living are intended to shorten the dead’s time in purgatory without the expectation of reward. In contrast, members of the Cult of the Dead expect the souls in purgatory to hear their prayers and affect change quickly in their lives. This added benefit explains the unique preoccupation with purgatory in Naples, from the unusually high number of confraternities devoted to caring and praying for the dead, such as the Arciconfraternita dei Bianchi and the Congrega di Purgatorio ad Arco, to the Neapolitan practice of building shrines to souls in purgatory in niches on the street, [Image at right] often complete with terra cotta figurines of people standing in flames and photos of deceased family members.

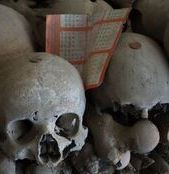

doctrine does not allow the souls in purgatory the power to bestow favors on the living, nor does it believe they ought to be venerated as one would venerate saints or the Virgin Mary. For orthodox Catholics, the relationship between the living and souls in purgatory is strictly one-sided and charitable: prayers said by the living are intended to shorten the dead’s time in purgatory without the expectation of reward. In contrast, members of the Cult of the Dead expect the souls in purgatory to hear their prayers and affect change quickly in their lives. This added benefit explains the unique preoccupation with purgatory in Naples, from the unusually high number of confraternities devoted to caring and praying for the dead, such as the Arciconfraternita dei Bianchi and the Congrega di Purgatorio ad Arco, to the Neapolitan practice of building shrines to souls in purgatory in niches on the street, [Image at right] often complete with terra cotta figurines of people standing in flames and photos of deceased family members. cult believes that souls whose names remain unknown, typically people who died in plagues, wars, or natural disasters, are doomed to an eternity in purgatory. These souls are represented by the anonymous bones in Naples’ numerous mass graves and burial caves which have been entombed without markers. [Image at right]. Within the Cult of the Dead, these souls are collectively venerated and are thought to be extremely powerful when it comes to bestowing miracles on the living. For this reason, the dead are often commemorated collectively, through the stacking and cataloguing of their bones (as in the case of the Fontanelle Cemetery), building churches above the places they were buried (as in the cases of Santa Maria del Pianto and Santa Croce e Purgatorio al Mercato which replaced the original plague column memorial), or in the preservation of anonymous bodies within the church (as are on display at the Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso detta la Sciabica).

cult believes that souls whose names remain unknown, typically people who died in plagues, wars, or natural disasters, are doomed to an eternity in purgatory. These souls are represented by the anonymous bones in Naples’ numerous mass graves and burial caves which have been entombed without markers. [Image at right]. Within the Cult of the Dead, these souls are collectively venerated and are thought to be extremely powerful when it comes to bestowing miracles on the living. For this reason, the dead are often commemorated collectively, through the stacking and cataloguing of their bones (as in the case of the Fontanelle Cemetery), building churches above the places they were buried (as in the cases of Santa Maria del Pianto and Santa Croce e Purgatorio al Mercato which replaced the original plague column memorial), or in the preservation of anonymous bodies within the church (as are on display at the Chiesa del Santissimo Crocifisso detta la Sciabica). veneration of anonymous human remains. This can take several forms. In the broadest sense, an entire town may adopt a mass grave site such as a prisoner’s cemetery, plague pit or potter’s field and erect a monument where people can come to pray to the souls and leave ex votos. In other instances, specific anonymous remains are adopted by a community and elevated to folk-saint status, as in the case of a mummy nicknamed “Uncle Vincent” [Image at right] in the town of Bonito.

veneration of anonymous human remains. This can take several forms. In the broadest sense, an entire town may adopt a mass grave site such as a prisoner’s cemetery, plague pit or potter’s field and erect a monument where people can come to pray to the souls and leave ex votos. In other instances, specific anonymous remains are adopted by a community and elevated to folk-saint status, as in the case of a mummy nicknamed “Uncle Vincent” [Image at right] in the town of Bonito. Purgatorio ad Arco), “Donna Concetta,” [Image at right] and the “The Captain” (both at the Fontanelle Cemetery) are treated like the relics of saints, in that they are considered community property and cannot be adopted by an individual. They receive prayers and thanks from many people and collect ex votos, for prayers answered, just as saints do at the shrines where their relics rest.

Purgatorio ad Arco), “Donna Concetta,” [Image at right] and the “The Captain” (both at the Fontanelle Cemetery) are treated like the relics of saints, in that they are considered community property and cannot be adopted by an individual. They receive prayers and thanks from many people and collect ex votos, for prayers answered, just as saints do at the shrines where their relics rest. or may place a coin on it [Image at right] . In other cases, the person is adopted by a particular skull who comes to the living in a dream to ask for veneration. Communications between the living and the dead typically occur through dreams and the unnamed soul will often reveal its name to the living in this way.

or may place a coin on it [Image at right] . In other cases, the person is adopted by a particular skull who comes to the living in a dream to ask for veneration. Communications between the living and the dead typically occur through dreams and the unnamed soul will often reveal its name to the living in this way. not available for adoption. Skulls that do not answer prayers can be stripped of their gifts and sometimes re-abandoned in favor of a skull with a more generous soul. (Though this vengeful behavior isn’t limited to the Cult of the Dead in Naples, the bust of the city’s most famous patron saint, San Gennaro, was thrown into the sea in 1799 for traitorously granting the wishes of an occupying French general.)

not available for adoption. Skulls that do not answer prayers can be stripped of their gifts and sometimes re-abandoned in favor of a skull with a more generous soul. (Though this vengeful behavior isn’t limited to the Cult of the Dead in Naples, the bust of the city’s most famous patron saint, San Gennaro, was thrown into the sea in 1799 for traitorously granting the wishes of an occupying French general.) tourists by locals with more orthodox views. While several of the mass grave sites and confraternity burial grounds have been closed to the public entirely, sites such as the catacombs of San Gennaro and church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco are now primarily cultural institutions controlled by the Council of Naples. Visitors must pay an entrance fee and are restricted to guided tours to discourage participation in the cult. While this has virtually eliminated unwanted ex votos and bone theft from the catacombs and hypogea, one can still find persistent traces of the cult in the form of ex votos, letters and candles left near these sites, or in the case of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco, near the grated window to the hypogeum on the street. [Image at right].

tourists by locals with more orthodox views. While several of the mass grave sites and confraternity burial grounds have been closed to the public entirely, sites such as the catacombs of San Gennaro and church of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco are now primarily cultural institutions controlled by the Council of Naples. Visitors must pay an entrance fee and are restricted to guided tours to discourage participation in the cult. While this has virtually eliminated unwanted ex votos and bone theft from the catacombs and hypogea, one can still find persistent traces of the cult in the form of ex votos, letters and candles left near these sites, or in the case of Santa Maria delle Anime del Purgatorio ad Arco, near the grated window to the hypogeum on the street. [Image at right]. and leaving devotional items that could damage the site. Over the years, the group has also addressed ongoing structural issues with the tufa cave (most recently a cave-in that closed the cemetery for several months in 2011 and water leaks that persist today). While I Care Fontanelle’s leadership has successfully addressed these pressing issues, the ongoing lack of funds has left the lighting and video surveillance systems in disrepair. Without these safeguards, the Cult of the Dead still operates. Its adherents leave rosaries, prayer cards, candles, lottery tickets, coins, and even plastic dolls and religious figurines for specific skulls; and new housings for skulls still occasionally show up.

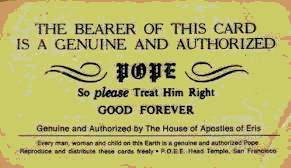

and leaving devotional items that could damage the site. Over the years, the group has also addressed ongoing structural issues with the tufa cave (most recently a cave-in that closed the cemetery for several months in 2011 and water leaks that persist today). While I Care Fontanelle’s leadership has successfully addressed these pressing issues, the ongoing lack of funds has left the lighting and video surveillance systems in disrepair. Without these safeguards, the Cult of the Dead still operates. Its adherents leave rosaries, prayer cards, candles, lottery tickets, coins, and even plastic dolls and religious figurines for specific skulls; and new housings for skulls still occasionally show up. and published (as five xeroxed copies) in 1965. Principia Discordia (also known as ‘The Magnum Opiate of Malaclypse the Younger’, subtitled How I Found Goddess and What I Did to Her When I Found Her) was an anarchic ’zine, which contained hand-drawn pictures, a jumble of typefaces, selected reproductions of “found’ documents, and instances of absurdist humor. Despite the fact that it lacked a coherent narrative or formal doctrines, the philosophy expounded in Principia Discordia was broadly consistent: Chaos is the only reality, and apparent order (the Aneristic Principle) and apparent disorder (the Eristic Principle) are merely mental constructs, created by humans to assist them to cope with reality. Humanity’s miserable existence, oppressed by convention, wage-slavery, sexual repression and a myriad other ills, results from the Curse of Greyface, discussed in the next section. Principia Discordia became a subcultural classic: it is freely available to all under what Hill and Thornley called “Kopyleft,” it is original, sharply clever, and funny (Cusack 2010:28-30).

and published (as five xeroxed copies) in 1965. Principia Discordia (also known as ‘The Magnum Opiate of Malaclypse the Younger’, subtitled How I Found Goddess and What I Did to Her When I Found Her) was an anarchic ’zine, which contained hand-drawn pictures, a jumble of typefaces, selected reproductions of “found’ documents, and instances of absurdist humor. Despite the fact that it lacked a coherent narrative or formal doctrines, the philosophy expounded in Principia Discordia was broadly consistent: Chaos is the only reality, and apparent order (the Aneristic Principle) and apparent disorder (the Eristic Principle) are merely mental constructs, created by humans to assist them to cope with reality. Humanity’s miserable existence, oppressed by convention, wage-slavery, sexual repression and a myriad other ills, results from the Curse of Greyface, discussed in the next section. Principia Discordia became a subcultural classic: it is freely available to all under what Hill and Thornley called “Kopyleft,” it is original, sharply clever, and funny (Cusack 2010:28-30). nevertheless profoundly attracted to all sorts of “strange” phenomena. He was a friend of Timothy Leary, the controversial advocate of psychedelic drugs, and had interviewed the popularist Zen author Alan Watts, for The Realist, a freethought magazine. In 1975, he and speculative fiction author Robert Shea, published the vast, sprawling, epic novel, Illuminatus! Trilogy, which ushered in the next phase of the Discordian penetration of popular culture. The first twenty years had been dominated by founders Thornley and Hill, and the religion had spread primarily by word of mouth, personal contact, and ’zines, the circulation of which was limited. By 1988, Illuminatus! was the highest selling science fiction paperback in the United States; it had been made into a rock opera and won awards (LiBrizzi 2003:339). The novel has a complicated, conspiratorial plot that will be discussed below. Most importantly, Shea and Wilson reproduced much of the text of Principia Discordia throughout it, winning a huge, mainstream audience for the subcultural scripture. Knowledge of Discordianism thus ceased to be truly esoteric and rare, and entered Western popular culture.

nevertheless profoundly attracted to all sorts of “strange” phenomena. He was a friend of Timothy Leary, the controversial advocate of psychedelic drugs, and had interviewed the popularist Zen author Alan Watts, for The Realist, a freethought magazine. In 1975, he and speculative fiction author Robert Shea, published the vast, sprawling, epic novel, Illuminatus! Trilogy, which ushered in the next phase of the Discordian penetration of popular culture. The first twenty years had been dominated by founders Thornley and Hill, and the religion had spread primarily by word of mouth, personal contact, and ’zines, the circulation of which was limited. By 1988, Illuminatus! was the highest selling science fiction paperback in the United States; it had been made into a rock opera and won awards (LiBrizzi 2003:339). The novel has a complicated, conspiratorial plot that will be discussed below. Most importantly, Shea and Wilson reproduced much of the text of Principia Discordia throughout it, winning a huge, mainstream audience for the subcultural scripture. Knowledge of Discordianism thus ceased to be truly esoteric and rare, and entered Western popular culture. sterile and destructive. Eris ordained order, which caused the emergence of disorder (which till then escaped notice as all was chaos). Void also generated a son, Spirituality, and mandated that if Aneris tried to destroy Spirituality he would be reabsorbed into Void. This became the Discordian doctrine concerning the fate of humans; “so it shall be that non-existence shall take us back from existence and that nameless spirituality shall return to Void, like a tired child home from a very wild circus” (Malaclypse the Younger 194:58). Discordian understandings of reality are monistic, a view that is usually understood to be Eastern in origin. Discordianism asserts that binary oppositions are illusory (male/female, order/disorder, serious/humorous) and affirms the oneness of all. Discordians follow Mal-2’s position, dismissing the “truth question” and stating that everything is true, including false things. He is asked how that works, and replied, “I don’t know, man. I didn’t do it” ( Malaclypse the Younger and Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst 2006:34).

sterile and destructive. Eris ordained order, which caused the emergence of disorder (which till then escaped notice as all was chaos). Void also generated a son, Spirituality, and mandated that if Aneris tried to destroy Spirituality he would be reabsorbed into Void. This became the Discordian doctrine concerning the fate of humans; “so it shall be that non-existence shall take us back from existence and that nameless spirituality shall return to Void, like a tired child home from a very wild circus” (Malaclypse the Younger 194:58). Discordian understandings of reality are monistic, a view that is usually understood to be Eastern in origin. Discordianism asserts that binary oppositions are illusory (male/female, order/disorder, serious/humorous) and affirms the oneness of all. Discordians follow Mal-2’s position, dismissing the “truth question” and stating that everything is true, including false things. He is asked how that works, and replied, “I don’t know, man. I didn’t do it” ( Malaclypse the Younger and Omar Khayyam Ravenhurst 2006:34). discord, a gift to the “most beautiful.” In this myth, Eris arrived at the wedding of the sea-nymph Thetis and the hero Peleus furious as the couple had not invited her. She threw the apple and the guests rioted, as the goddesses argued over who should possess it. The apple was awarded by the Trojan prince Paris to Aphrodite the goddess of love, which was resented by her rivals Athena and Hera (Littlewood 1968:149-51). She promised Paris the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta, which led to the Trojan War when her husband Menelaus and Agamemnon of Mycenae invaded Troy. The Discordian version of the myth has Eris “joyously partake of a hot dog” after she departs, and concludes “and so we suffer because of the Original Snub. And so a Discordian is to partake of No Hot Dog Buns. Do you believe that?” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:17-18). The second myth is the “Curse of Greyface,” which explains humanity’s predicament, which is due a “malcontented hunchbrain,” Greyface, who in 1166 BCE taught that humor and play violated Serious Order, the true state of reality. Greyface and his followers “were known even to destroy other living beings whose ways of life differed from their own,” which resulted in humanity “suffering from a psychological and spiritual imbalance” called the Curse of Greyface (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:42). These myths teach that humanity needs liberation.

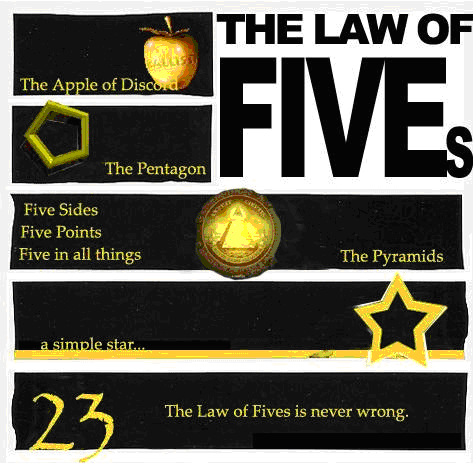

discord, a gift to the “most beautiful.” In this myth, Eris arrived at the wedding of the sea-nymph Thetis and the hero Peleus furious as the couple had not invited her. She threw the apple and the guests rioted, as the goddesses argued over who should possess it. The apple was awarded by the Trojan prince Paris to Aphrodite the goddess of love, which was resented by her rivals Athena and Hera (Littlewood 1968:149-51). She promised Paris the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta, which led to the Trojan War when her husband Menelaus and Agamemnon of Mycenae invaded Troy. The Discordian version of the myth has Eris “joyously partake of a hot dog” after she departs, and concludes “and so we suffer because of the Original Snub. And so a Discordian is to partake of No Hot Dog Buns. Do you believe that?” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:17-18). The second myth is the “Curse of Greyface,” which explains humanity’s predicament, which is due a “malcontented hunchbrain,” Greyface, who in 1166 BCE taught that humor and play violated Serious Order, the true state of reality. Greyface and his followers “were known even to destroy other living beings whose ways of life differed from their own,” which resulted in humanity “suffering from a psychological and spiritual imbalance” called the Curse of Greyface (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:42). These myths teach that humanity needs liberation. five … [and] the Law of Fives is never wrong” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:16). The pentagon in the Sacred Chao is a five-sided figure, and the Law of Fives results in 23 being a number of significance for Discordians, as 2 + 3 = 5. The Pentabarf, the Discordian profession of faith (“catma,” which is flexible and provisional, as opposed to “dogma,” which is rigid and unchanging), has five principles (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:4):

five … [and] the Law of Fives is never wrong” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:16). The pentagon in the Sacred Chao is a five-sided figure, and the Law of Fives results in 23 being a number of significance for Discordians, as 2 + 3 = 5. The Pentabarf, the Discordian profession of faith (“catma,” which is flexible and provisional, as opposed to “dogma,” which is rigid and unchanging), has five principles (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:4): the Assassins, but also as part of Kerry Thornley’s life in the wake of the Kennedy assassination. In the late 1970s, he descended into paranoia, believing his friends had been replaced by look-alikes and that he was living in the reality of Operation Mindfuck. A key Discordian term, fnord, which is disinformation spread by a worldwide conspiracy appears in Principia, but is amplified in meaning by Shea and Wilson, for whom the ability to “see the fnords” is a quality of the enlightened characters (Wagner 2004:68-69). Thornley’s later years were chronicled in interviews with the journalist Sondra London. These are available on YouTube, and the full text of the interviews, titled The Dreadlock Recollections, was released in 2000 (Thornley 2007). Thornley by then regarded Discordianism as essentially Zen Buddhist in nature, and it is true that its worldview is non-dualist, a monistic view of reality in which all is underscored by chaos. This view fits with many Eastern religions that are pantheist and mystical in orientation; as Principia Discordia stated, “all affirmations are true in some sense, false in some sense, meaningless in some sense, true and false in some sense, true and meaningless in some sense, false and meaningless in some sense, and true and false and meaningless in some sense” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:39-40).

the Assassins, but also as part of Kerry Thornley’s life in the wake of the Kennedy assassination. In the late 1970s, he descended into paranoia, believing his friends had been replaced by look-alikes and that he was living in the reality of Operation Mindfuck. A key Discordian term, fnord, which is disinformation spread by a worldwide conspiracy appears in Principia, but is amplified in meaning by Shea and Wilson, for whom the ability to “see the fnords” is a quality of the enlightened characters (Wagner 2004:68-69). Thornley’s later years were chronicled in interviews with the journalist Sondra London. These are available on YouTube, and the full text of the interviews, titled The Dreadlock Recollections, was released in 2000 (Thornley 2007). Thornley by then regarded Discordianism as essentially Zen Buddhist in nature, and it is true that its worldview is non-dualist, a monistic view of reality in which all is underscored by chaos. This view fits with many Eastern religions that are pantheist and mystical in orientation; as Principia Discordia stated, “all affirmations are true in some sense, false in some sense, meaningless in some sense, true and false in some sense, true and meaningless in some sense, false and meaningless in some sense, and true and false and meaningless in some sense” (Malaclypse the Younger 1994:39-40). Discordianism is “the fastest growing religion in all creation (Discordians grow at the exact same rate as the population)” (Chidester 2005: 199). Despite POEE being deemed a “non-prophet irreligious disorganization” and Discordianism “an anarchist’s paradise” (Adler 1986:332), as noted above members do get together to practice the religion. Discordian groups are called “cabals” (from kabbalah, the Jewish mystical system). Discordians do not have to join a cabal, but members often do. In the early twenty-first century many cabals are online (Narizny 2009).

Discordianism is “the fastest growing religion in all creation (Discordians grow at the exact same rate as the population)” (Chidester 2005: 199). Despite POEE being deemed a “non-prophet irreligious disorganization” and Discordianism “an anarchist’s paradise” (Adler 1986:332), as noted above members do get together to practice the religion. Discordian groups are called “cabals” (from kabbalah, the Jewish mystical system). Discordians do not have to join a cabal, but members often do. In the early twenty-first century many cabals are online (Narizny 2009). several shifts in membership before summer, 2006 when there were only four people left on the committee: Charlie Johnson, Larry Yang, Spring Washam and David Foecke. Charlie Johnson is an Insight and Yoga teacher who has served on the board of directors at both Spirit Rock Meditation Center and EBMC. Larry Yang is an Insight teacher who has made a significant contribution to bringing diversity and multicultural awareness and training to the Insight community. Spring Washam is an Insight teacher who is well known for bringing mindfulness to minority populations. David Foecke is an Insight practitioner who was instrumental in developing EBMC’s generosity-based economics (gift economics system). In March, 2007, Mushim Patricia Ikeda, a Zen-trained Buddhist teacher and diversity facilitator, and Kitsy Schoen, an Insight teacher, joined the founding members. These six figures were known as the original “core teachers” at EBMC (Gleig 2014 and East Bay Meditation Center n.d.).

several shifts in membership before summer, 2006 when there were only four people left on the committee: Charlie Johnson, Larry Yang, Spring Washam and David Foecke. Charlie Johnson is an Insight and Yoga teacher who has served on the board of directors at both Spirit Rock Meditation Center and EBMC. Larry Yang is an Insight teacher who has made a significant contribution to bringing diversity and multicultural awareness and training to the Insight community. Spring Washam is an Insight teacher who is well known for bringing mindfulness to minority populations. David Foecke is an Insight practitioner who was instrumental in developing EBMC’s generosity-based economics (gift economics system). In March, 2007, Mushim Patricia Ikeda, a Zen-trained Buddhist teacher and diversity facilitator, and Kitsy Schoen, an Insight teacher, joined the founding members. These six figures were known as the original “core teachers” at EBMC (Gleig 2014 and East Bay Meditation Center n.d.). January 20, 2007. Shortly afterward, they invited the pre-existing East Bay LGBTQI group to sit at the center. EBMC has since added a number of population specific sitting and mindful movement groups. These include an EBMC teenage sangha, an “Every Body Every Mind” group for people with chronic illness and disabilities, a People of Color yoga group, and a recovery and dharma sangha. In addition to this, the EBMC has developed a robust calendar of events that include such things as family practice classes and workshops on nonviolent conflict reconciliation. The attendance at these events grew rapidly, with often a fifty to sixty percent waiting list for daylong programs. In order to accommodate such high demand, in 2012, EBMC relocated to a much larger space in downtown Oakland.