LUCIFERIANISM TIMELINE

1231: Luciferian was used as an accusation against heretical Christians in Tier, Germany.

1667: John Milton´s Paradise Lost was published.

1840: Alphonse Louis Constant published Bible de la liberté.

1875: The Theosophical Society was founded.

1885: Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès, using the pen name Léo Taxil, “converted” to Catholicism and began an expose of Luciferians within Freemasonry.

1888: The Secret Doctrine by Helena Blavatsky was published.

1899: Charles Leland published his Aradia; the Gospel of the Witches in which Lucifer appeared as a sun god.

1906: Ben Kadosh (Carl William Hansen) published The Dawn of a New Morning: Lucifer-Hiram: The Return of the World’s Master Builder and referred to himself as a Luciferian in a Danish population census.

1914: Anatole France published Revolt of the Angels (La Révolte des anges)

1926: The Fraternitas Saturni was founded by Gregor A Gregorius (Eugen Grosche).

1929: Magick in Theory and Practice by Aleister Crowley was published in which he described Lucifer as identical to “AIWAZ, the solar-phallic-hermetic ‘Lucifer’,” His own Holy Guardian Angel.”

1956: Madeleine Montalba and her partner, Nicolas Heron, founded the Order of the Morning Star, or Ordo Stella Matutina (OSM).

1966: The Process Church of the Final Judgment was founded.

1972: The Kenneth Anger movie Lucifer Rising was released.

1989: Dragon Rouge was founded in Stockholm, Sweden.

2005: The Neo-Luciferian Church was founded in Copenhagen, Denmark.

2015: The Greater Church of Lucifer opened a church in Springs, Texas, leading to protests from Christian groups.

2015: Author Michael Howard, central in the popularization of Luciferianism died.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Luciferianism does not have a founder nor is it represented by a specific group or ideology; [Image at right] rather, it’s a reference to a heterodox and internally conflicted modern religious/spiritual phenomenon. Like “Witchcraft” and “Satanism,” “Luciferian” was originally used as an accusatory label by the Church. The first time the term seems to have been used is 1231 in Gesta Treverorum a chronology and history of the Archbishops in Tier, present day Germany (Luijk 2016:30). Here we find mentioned a woman, Lucardis, who lead a pious religious circle but was accused of secretly lamenting “the unjust expulsion from Heaven of Lucifer.” Following this “expose” of Luciferians, the church began a crusade to find more Luciferians. In 1234, Pope Gregory IX sent the bull Vox in Rama where we find one of the first descriptions of Luciferian initiations and rituals that foreshadow later descriptions of the Witches Sabbat and Black Masses with desecrations of the Host, inversions of the Mass and sexual orgies (Luijk 2016:31). That there existed any Luciferians during this period outside the imagination of the Church and the Pope is, however, unlikely.

During the thirteenth through the fifteenth centuries there where several cases where worship of Lucifer was used as an accusation against heretical groups, like the Cathars and the Waldensians. There is, however, no evidence that any of the groups or persons mentioned had beliefs that in any form resembled the Papal descriptions; rather, they seemed to have regarded the Church as being under the control of Lucifer (Luijk 2016:28). Even if there never existed any Luciferians in this period, the myth of their existence would be used by both anti-Satanists as well as modern-day Luciferians and Satanists. It gave their traditions a more substantial pedigree, even if most of both Luciferians and Satanists probably see this as more of a mythological story. As an example of how the myth of early Luciferians influenced modern Satanism and Luciferianism is H.T.F Rhodes’ 1954 history of early Satanism in The Satanic Mass that was a central inspiration for the founder of the Church of Satan, Anton LaVey. During the reformation in the sixteenth century and the internal conflicts within Christianity that followed, accusations of Devil and Lucifer worship continued, again directed against other Christians. However, there is no evidence of any groups that venerated Lucifer existing in this period (Medway 2001:9).

Central for the development of both modern Luciferianism and Satanism was a literary work John Milton’s Paradise Lost from 1667. While presented as a defence of the rule of God, some later readers would find Lucifer not as a the villain but as a heroic character reminiscent of the Greek Titan Prometheus who stole the fire from Heaven and gave it to humanity, Indeed, Lucifer’s speech in the first book has become central for the development of the heroic Satan (Lucifer):

Here at least

we shall be free; the Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure, and in my choice

to reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven

Milton’s image of Satan (as a tragic, courageous being, who even act with love and comradery with his fellow fallen angels) was essential to the image of Lucifer that we find later, and modern Luciferianism can’t be understood without this reference. Reception of Milton’s Lucifer as a heroic symbol for liberation and rebellion would develop with the Romantics, and with poets. Writers like Mary Wollstonecraft, William Blake, Percy Shelly, and Lord Byron all made use of Milton’s work to present a heroic, if not always outright positive image, of Lucifer (Werblowsky 2007).

While heterodox views of Lucifer and Satan were presented, it should be noted that the primary source of inspiration for the Romantics was Hellenism and Greek mythology dominated the writings. Lucifer became associated with the Greek titan Prometheus that stole the fire from Mount Olympus. Noticing the similarities between the two myths, it became easy to view Lucifer in a favourable light, even if poets like Percy Shelly emphasised that, while heroic, Lucifer was not as noble as Prometheus who rebelled without selfish motives (Schock 2003:39).

One of the best examples of the romantic reimagining of Milton was William Blake’s The Marriage between Heaven and Hell (1793) that presents an image of Hell and Satan as symbols of creativity and movement, in balance and opposition to the stasis of Heaven. Blake refers to Milton and claims he was of the Devils party without knowing it. With the Romantics, the image of Lucifer as a symbol of rebellion and quest for knowledge is established, but it is only in a literary sense and not without ambivalence. There is no indication or evidence that there developed any form of spiritual movement from the Romantic Satanists in the nineteenth century, although they would inspire later Luciferians and Satanists. There is also no real separation between Satan and Lucifer, rather they are treated as synonymous, but based on a reception of Milton rather than the Bible (Schock 2003).

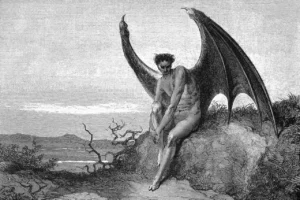

Among some nineteenth-century socialists Lucifer would become a role model for the revolution, often more satirical and anti-clerical, as with Anarchists like Pierre Proudhon and Michael Bakunin, than based on a veneration for Lucifer. An interesting example of how Lucifer was used by nineteenth-century socialists are the “Ten commandments of Lucifer” (1886), a short text distributed among Swedish socialists by Atterdag Wermelin (1861-1904). The text is a mockery of the Ten Commandments but also contains serious calls for solidarity among workers, equality between men and women, and a rejection of monogamy and the institution of marriage (Faxneld 2013). For the early, more radical part of the labour movement, Lucifer appears rather frequently as a symbol for freedom and liberation, and several magazines took the title Lucifer. In Sweden there was the yearly published periodical for the Social Democrats titled Lucifer: the light bearer (Lucifer: Ljusbringaren, 1891-1895, quarterly 1902-1903) and in the United States we find Moses Harmans anarchist magazine Lucifer, the Light Bearer (1883-1907). We also find the fictional work of the socialist author Anatole France Revolt of the Angels (La Révolte des anges) from 1914 that describes Lucifer as a force that through the ages has attempted to help humanity. France identifies Lucifer with Satan and see the evolution of Lucifer to Satan as a positive. The book is perhaps one of the clearest examples of literary Satanism and in the twenty-first century, and the book became one of the canonical texts for the Satanic Temple (Hedenborg White and Gregorius 2019).

In the middle and later part of the nineteenth century, a revised version of Lucifer starts to enter esoteric movements both in fiction and reality. A bridge between the socialist interpretation and the esoteric is Eliphas Lévi (i.e., Alphonse-Louis Constant, 1810–1875). Following the Romantics, Leví wrote in Bible de la liberté (1840) that Lucifer was an angel of Liberty and that in the end he would be reunited with God. Leví would continue these themes later when his work would turn to more occult ideas around the Astral Light. While earlier biographies of Leví argued that there was a clear break between his earlier political writings as Constant and his later occult writings, religious scholar Julian Strube has argued that there is a continuity and his later occult works must be understood from the backdrop of his utopian socialist ideals. Leví was part of a occult movement in France that presented themselves as Neo-Catholic or Gnostic and still regarded themselves as Christians (Strube 2016).

The most important Luciferian legacy from France in the nineteenth century did not come from an existing Luciferian milieu but a mostly imaginary one. In 1885, the French Anti-Catholic, Marie Joseph Gabriel Antoine Jogand-Pagès, using the pen name Léo Taxil (1854-1907), had publicly converted to Catholicism and at the same time exposed a massive conspiracy against the Church directed by Freemasons. Jogand-Pagés would publish several books both under the name Leo Taxil, and other pseudonyms, in which he described a global cult around Lucifer that he claimed where at the centre of Freemasonry. The secret inner circle was called the Palladium and was lead by a woman, Diana Vaughn. The Palladium, as described by Taxil, believed that Lucifer was the true God, in opposition to the lesser god Adonai, and the two gods were in a battle for control over the Earth and mankind (Luijk 2016:266-69). A few years later, Jogand-Pagés revealed publicly it was all a prank, carried out to ridicule both the Catholic Church and Freemasonry. Despite this, many would continue to take his ideas seriously, and they can still be found in conspiracy theories around secret societies. For some esoteric writers this was seen as intriguing, however, and they developed a positive reception to Taxil´s hoax. One example of this was the Danish Luciferian Ben Kadosh who will be discussed below. While most of the descriptions about Luciferians were based on accusations, as we have seen, there where esoteric writers that had a more sympathetic view on Lucifer.

The most influential proponent of a positive view of Lucifer came from the Theosophical Society (1875), founded by Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832-1907). With the Theosophists, we generally see Lucifer presented as a symbol of illumination, and they would even name their magazine Lucifer. For Blavatsky, Lucifer was the bringer of light to mankind and identified Lucifer with Prometheus but also with “Mahasura” in Hinduism, who was cast down after rebelling against Brahma, and made, according to Blavatsky, to repent. Lucifer can be seen as a symbol of human evolution and initiation. For Helena Blavatsky Lucifer was integrated in a non-dualist cosmology based on a Western reception of Buddhism and Hinduism, and a rejection of Christian doctrines, as is noticeable in the quote above as well. As to what degree Lucifer and Satan where identified within Theosophy is debated, often Blavatsky would be clear in distinguishing them but scholars like Per Faxneld have argued that the writings of Blavatsky contained “unembarrassed and explicit Satanism” (Faxneld 2012).

Within Blavatsky’s voluminous writings there are clear positive descriptions of Lucifer, and while it is debatable as to whether this should be regarded as central to her worldview, the references we find, most notably within The Secret Doctrine (1888), would have a central impact on later receptions of Lucifer. For some Theosophists the positive image of Lucifer would become central, as with the Swedish painter Sven Bengtsson (1843-1916), who painted Lucifer as an angelic being combatting the forces of ignorance, represented as a dark monster.

Perhaps the first person who used “Luciferian” as a self-identification was Ben Kadosh, the penname for the Danish esotericist and eccentric Karl William Hansen (1872-1936). Kadosh had been involved with several different forms of esoteric order and was an early, pre-Thelemic, member of Ordo Templi Orients. In 1906, when he was thirty-three, he published Den Ny Morgens Gry, Lucifer-Hiram, Verdensbygmesterens Genkomst (The Dawn of a New Morning, Lucifer-Hiram, The Return of the World’s Master Builder). The Neo-Luciferian Church, which considers its work to be partially a continuation of Kadosh, published a revised translation of the text in 2010. Later, a new translation was made by Johan Nilsson and Rebecca Bugge and published in the anthology Satanism: A reader, 2023. In the small book we see a strong influence from Theosophy but also Leo Taxil. Kadosh sees Lucifer as the true god of creation and individuality:

Lucifer is the “sum” – or I – of the material nature, the creative logon or force. Both personal and impersonal or individual and non-individual, just as everything else in nature, as it should be. Actually, he is the object and the individual in the third person. (quoted in Nilsson 2023a:132).

Further, he associated this doctrine with the secret teachings that he believed were found in Freemasonry, which is evident from the title of Lucifer as the “Worlds Master Builder.” Lucifer is regarded as the energy of Darkness, and thus superior to the Light, partially following Blavatsky. As Per Faxneld has commented the image of Lucifer is rather unique:

Lucifer is portrayed by Kadosh as a sort of rebellious and “criminal” initiator, giving man access to mysteries that the Christian church has tried to keep hidden. He is, according to Kadosh, a phallic and expansive personification of energy, which is why he is the nemesis of all attempts to confine and limit. (Faxneld 2011)

The idea of Lucifer as a phallic and vitalist force is reminiscent of Crowley’s presentation of Lucifer but predates Crowley as he would present this mostly in later in works, like the 1929 Magick in theory and Practice. The short text is complicated and at times difficult to follow. Lucifer is also seen as Pan and Venus. Kadosh makes a point that this might seem paradoxical as Lucifer is very masculine. Pan is particularly important, and a large part of the text deals more with Pan than with Lucifer. Kadosh sees something sacred in the animal nature and regards a union or an integration of the animal intelligence as a form of path to enlightenment.

Kadosh took a lot of inspiration from the sensationalist book Satan og hans kultus (1902) by Carl Kohl that also builds upon the Leo Taxil-hoax. Apart from Lucifer-Hiram, Kadosh never published more about Luciferianism, and while he claimed to have gathered a small number of followers, there is no indication that they continued after his death or even remained active during his lifetime. What little we know about his life is from other sources, some being ironic and cynical descriptions by August Strindberg, who seems to have regarded him as a fascinating but a to confused (Faxneld 2011). After his death in 1936 he would become almost completely forgotten until an English translation of Lucifer-Hiram was published in the Swedish occult journal The Fenris Wolf nr 3 in 1993. In recent years, there has been a revived interest in Kadosh and he is seen as one of the main antecedents for the Neo-Luciferian Church. There has also been a growing academic interest in Kadosh, primarily through the work of Per Faxneld who has published several articles about him. Kadosh is of interest as one of the few, if not the first that identified himself as a devotee of Lucifer/Satan and identified as Luciferian in a national census in Denmark in 1906 (Faxneld 2011). Whether his interest in Luciferianism remained through his life is uncertain as there is limited information about his life and the only other text available from him is a later Rosicrucian text that contains no Luciferian aspects or such doctrines (Nilsson 2023a:123).

During the same period, but only partially related to each other, there was also a significant positive reception of Lucifer in the early modern re-imagining of Witchcraft as a positive form of spirituality. Charles Leland´s Aradia; the Gospel of the Witches (1899) tells the story of the goddess Aradia, daughter of Diana and Lucifer, incarnating on Earth to help the people with magic and poison against the oppression of feudal lords and the Church. In Aradia, Lucifer is the god of the Sun and Moon, and the twin and reflection of Diana, who is seen as the primary creatrix. Still, even though clearly more Pagan, Lucifer is still presented as a rebellious and proud spirit: “Diana greatly loved her brother Lucifer, the god of the Sun and of the Moon, the god of Light (Splendor), who was so proud of his beauty, and who for his pride was driven from Paradise.” (Gregorius 2012:232f)

Aradia is a controversial text as Leland claimed that it was not his own invention, but rather that the text was given to him from his assistant Maddelena and based on genuine folk magical traditions from Italy. Many critics have argued that the text was Leland’s own invention. Regardless of the origin, Aradia would be a central influence of the Wiccan movement in the 1940’s. While Wicca would disassociate from any types of Satanism, references to Lucifer in Wiccan literature would continue, as in the works of Alex Sanders and Janet and Stewart Farrar. Here Lucifer has become a solar deity, developed from Aradia but with very little to do with the fallen Angel (Gregorius 2012:234).

Following Theosophy, we find several esoteric writers that present an ambivalent if not outright positive view of Lucifer in the twentieth century. One important example is Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) who continually presents Lucifer as a positive symbol, representing initiation and knowledge. He even identifyied Aiwass, the angelic being that dictated The Book of the Law to him, with “Solar-Phallic hermetic Lucifer” (Crowley 1998:227). An influential poem regarding Lucifer was then undated, and, during his lifetime, the unpublished poem Hymn to Lucifer ends with:

His body a bloody-ruby radiant

With noble passion, sun-souled Lucifer

Swept through the dawn colossal, swift aslant

On Eden’s imbecile perimeter.

He blessed nonentity with every curse

And spiced with sorrow the dull soul of sense,

Breathed life into the sterile universe,

With Love and Knowledge drove out innocence

The Key of Joy is disobedience (Crowley in Nilsson 2023b:170).

The poem would later have a significant impact on modern occulture through the American film maker Kenneth Anger (1927-2023), who used the poem as a primary inspiration for his 1972 movie Lucifer Rising. It also seems that the first time the poem was published was by Anger in 1970. Anger saw, like Crowley in Lucifer a spirit of freedom and rebellion and as the patron of the artist. He regarded Lucifer as separate from Satan. Anger would also tattoo Lucifer across his chest.

Still, it would be wrong to label Crowley a Luciferian, and he never uses the term, even if his works undoubtedly have such aspects, as well as a revision of Biblical motifs and characters. How Crowley interpreted negative Biblical symbols as positive has been analysed in Manon Hedenborg White´s The Eloquent Blood: The Goddess Babalon and the Construction of Femininities in Western Esotericism (2019). A similarly positive image of Lucifer is also found in the writings of Crowley’s disciple Jack Parsons (1914-1952). He presents Lucifer as a spirit of individuality and rebellion, pared with the goddess Babalon, and connected this with his ideas about “the Witchcraft.” While a few short texts survive, there is no evidence that Parsons managed to create any form of practice around these beliefs before his death in 1952.

As we move further in the twentieth century, there is more open expressions of Luciferian ideas. One notable example is the German esoteric order Fraternitas Saturni, founded 1926 by Eugen Grosche (1888-1964), writing as Gregor A Gregorius. According to Thomas Hakl, the cosmology of the Fraternitas Saturni is based on a polarity and conflict between, light and dark, fire and ice, and this cosmology is light as separated from darkness as represented by Chrestos (light, the sun). Lucifer is the force carrying the light to Saturn, the planet farthest from the Sun, representing the other polarity as opposed to Chrestos. Lucifer also becomes the higher octave of Saturn. While Fraternitas Saturni used the term “Luciferian Principle,” there is no indication that participants labelled themselves as Luciferians or that the Lucirerian Principle played a significant role (Hakl 2013). Fraternitas Saturni was introduced to the anglophone world with Stephen Flowers book Fire and Ice: Magical Teachings of Germany’s Greatest Secret Occult Order (1995), which also included translations of some of their ceremonies. In his book Flowers emphasised the Luciferian and Satanic elements of Fraternitas Saturni.

One of the more interesting examples of a non-Satanic Luciferianism was the British occultist Madelaine Montalban (1910-1982). Montalban published very little about her Luciferian ideas during her lifetime, so a lot is ascribed to her comes from people associated with her, like Michael Howard. Julia Philps’ Madeline Montalban: The Magus of St Giles is the only currently available biography of her (2012).

In 1956, she founded, with Nicolas Heron, the Order of the Morning Star, or Ordo Stella Matutina (OSM). OSM developed a system of magic based on astrology and interaction with angelic beings, one of the aims being for the adept to develop a relationship with these angelic beings themselves. She wrote a small text, The Book of Lumiel, that is as of yet unpublished. Based on extracts from the book, primarily from Michael Howard and Julia Philips, we encounter Lucifer as Lumiel, the light-bringer [Image at right] that seek to guide mankind from darkness to light. For Montalban, Lumiel was originally a Babylonian god, and she made several references to Chaldean magic as central for her work and associated it with Venus.

Montalban made a clear distinction between Lucifer and Satan, and, according to Howard, the teachings of Lumiel or Lucifer came rather late in the courses of OSM and were further developed in a text called The Book of the Devil. In this text, Lucifer is presented as the first created being, the first subdivision of God “representing divine knowledge and wisdom and the intellect.” Lucifer is appointed by God or “the Cosmic Creator” to rule over the Earth and is devoted to the evolution of mankind. Montalban interprets the story of the fall of the Watchers as the angelic beings mixed their vibrations with the “daughters of men.” The reason being that Lucifer felt that the evolution of mankind was too slow. However, mankind was not prepared for this wisdom, and so it led to chaos and anarchy. As punishment, Lucifer had to incarnate in human form and become “The Light of the World” and take upon himself “pain and sorrows” of mankind. Montalban is presenting an idea that Christ was one of Lucifers incarnations. Following this description, we see a developed and original take on the story of the fall of Lucifer, in some respects it is reminiscent of the ideas found among the Kurdish Ezidi or Yezidi. The Order of the Morning Star considers its understanding of Lucifer to have nothing to do with Satanism.

Montalban’s teachings from OSM are largely unpublished, and so later interpretations largely come from the recollections of her students. One of the most important of these was Michael Howard (1948-2015), a member in OSM between 1967-1969. Howard was one of the most central and original thinkers within the British Pagan scene, being the chief-editor of The Cauldron (1976-2015) and one of the primary writers popularising Luciferianism within modern Paganism and Witchcraft. Howard was a member of several different Pagan and Esoteric organisations, and in 1999 he was initiated into Andrew Chumbleys Cultus Sabbati. Howard developed ideas about Lucifer that contained elements from a variety of esoteric authors, like Montalban, Cochrane and Chumbley. Writing under the pseudonym Frater Ashtan, he wrote articles about Luciferianism for The Cauldron, and later these ideas would be published in books like Pillars of Tubal Cain (2001) and The Book of Fallen Angels (2004). Howard also wrote about the history of Traditional Witchcraft in Children of Cain (2000) and several works on local British forms of Witchcraft where he emphasised the Luciferian element. The Luciferian elements are noticeable in his later works and particularly the above-mentioned Pillars of Tubal Cain and The Book of Fallen Angels (Gregorius 2012:243f).

Howard attributed strong Luciferians components to the work of Montalban but also to the work of Robert Cochrane (1931-1966), founder of a Witchcraft traditions during the 1950s that diverged from Gerald Gardner’s. This has led to some critique that Howard overemphasized Lucifer and interpreted Cochranes texts to fit his own beliefs, as Lucifer does not seem to be mentioned in the surviving writings of Cochrane.

While the term “Luciferian” was established as a reference to a form of spirituality that expressed a positive view of Lucifer, and there were several positive reimagining’s of Lucifer in the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, it is more difficult to find examples of groups or individuals that used the label Luciferian about themselves. Neither Blavatsky or Crowley used it, and as far as I can see, neither did the Fraternitas Saturni, although there is mention about a Luciferian principle. The first to publicly call himself Luciferian seems to have been Ben Kadosh in 1906. Another early example of the use of the term Luciferian publicly as a self-imposed identity was within the Process Church of the Final Judgment (active from 1966 until the middle of the 1970´s) which identified “Luciferian” as one of the identities to be used by their members, the others being Jehovian and Satanist. The Process is of interest as they make a clear distinction between Lucifer and Satan, as well as Luciferian and Satanist. For the Process Church, Luciferians where more optimistic and positive to life than the Satanist:

LUCIFER, the Light Bearer, urges us to enjoy life to the full, to value success in human terms, to be gentle and kind and loving, and to live in peace and harmony with one another. Man’s apparent inability to value success without descending into greed, jealousy, and an exaggerated sense of his own importance, has brought the God LUCIFER into disrepute. He has become mistakenly identified with SATAN. (De Grimston 1970)

For the Process Church the goal was the unity of the gods of the universe (,Jehova, Satan, Lucifer and Christ), the latter being both a fourth god and the unifying principle. None of the gods was evil but could be unbalanced and reflected aspects of a person that had to be both embraced and worked upon. Members could be combinations of these gods. The idea of the unity between the gods was also related to a millenarian idea about the end times that would happen when the gods where united in love. Later in the 1970’s, the Process Church faced a lot of internal conflicts and outside pressure and was disbanded. In 1977, it reformed as the Foundation Faith of the Millennium (Gregorius 2023a).

It is in the later part of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries that we find clear examples of self-identified Luciferian groups. One example is the Neo-Luciferian Church (NLC) founded in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2005 by Bjarne Salling Pedersen in collaboration with Michael Bertiaux from Chicago. The NLC practices a form of Luciferianism that is inspired by Gnosticism and draws a lot of inspiration from the writings of Ben Kadosh, but also from the Thelema and Bertiaux eclectic interpretation of Vodou. The Neo-Luciferian Church has a linage that traces back to the different esoteric and occult orders that where founded by Michael Bertiaux, but also Gnostic French esoteric traditions. Organized as an initiatory order NLC have seven degrees, but only six are named: Lightbearer, Deacon, Priest/priestess, High Priest/priestess, Bishop and Arch-Bishop. As initiations are only performed physically, NLC have not expanded in any significant degree outside of Denmark and Sweden, though there are a few members in the United States. There is a visible influence from the degree structure found in the Thelemic organisations Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica and Ordo Templi Orientis (Neo-Luciferian Church website 2013).

Members of NLC are expected to develop their own understanding of Lucifer and Luciferianism, and NLC encouragescritical thinking and rejection of authorities. The idea of Lucifer is non-Satanic and NLC contrast Luciferianism with Satanism. Lucifer is presented as a force for illumination and the quest for knowledge, and members argue strongly against an identification between Lucifer and Satan. As such they are a distinctly non-Satanic form of Luciferianism. While the webpage for NLC is no longer active, the group maintains its activities primarily in Denmark and Sweden (personal communication)

One of the most important Luciferian authors is the American Michael Ford who has published several books on Luciferianism such as The Bible of the Adversary, Luciferian Witchcraft, Luciferian Goetia, to name a few. He also runs the webpage Luciferian Apotheca and is currently one of the leaders of the Assembly of Light Bearers. Before he was one of three leaders of the Greater Church of Lucifer, founded. The Greater Church of Lucifer opened a physical church 2015 in Spring, a suburb to Houston, Texas. After a few months the church had to close due to protests and harassment and one of the leaders later converted to Evangelical Christianity (Blakinger 2017). In articles connected to the opening of the church and the following protests, Ford, and other members, where clear that they were not Satanists and regarded Luciferianism as being a separate tradition. Like other forms of Luciferianism Ford places a central emphasis on rebellion and questioning authority, but he also uses symbols and images that are more Satanic and Demonic than many other forms of Luciferianism (Cevjan 2023:317-321). Ford see his form of Luciferianism as part of the Left Hand Path, a term not used by all Luciferians. After the collapse of the Greater Church of Lucifer in North America Ford with two other members created the Assembly of Light Bearers that remains active (Assembly of Light Bearers website 2018).

While there are some organizations that will explicitly use the term Luciferian like the Greater Church of Lucifer (reconstituted as Assembly of Light Bearers), the Neo-Luciferian Church, the Luciferian Society, there are also orders that have Luciferian tendencies and been central to the development of modern Luciferianism. The Swedish based order Dragon Rouge, founded in 1989, has strong Luciferian tendencies, and, as their material have become available in English, they are now more influential globally with active groups especially in South America. Dragon Rouge use term “dark magic” for their practice and see themselves as part of the Left Hand Path. The founder Thomas Karlsson have claimed to have had revelations from Lucifer that he sees these the foundation of his order. Dragon Rouge is however an organisation that contains a lot of different forms of magical practices, and the order cannot as such be labelled as explicitly Luciferian, even if Lucifer plays a central and recurring role (Gregorius 2023b:306-13 and Granholm 2014:113, 122). The Polish artist and writer, Asenath Mason, who used to lead the Polish section of Dragon Rouge, Lodge Magan, has published extensively on Lucifer. In her organization, Temple of the Ascending Flame, the focus is on Lucifer as a part of a Draconian trinity. The other is Leviathan and Lilith, and Lucifer representing the solar and enlightenment (Mason 2007; Aseanth Mason: Author and Artist website 2024). Her work often follows similar themes as those found in Dragon Rouge with work on the Qliphotic.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Luciferianism is as an umbrella term for different new religious movements and ideologies that venerate Lucifer as either as an ideal or as a deity and there are no set doctrines as such to be found. Luciferians can differ on who Lucifer is supposed to be and there are Luciferians that are atheists and those that are theistic, some are closer to Satanism while other emphasise Lucifers pre-Christian origins like the Order of the Morning Star and the Neo-Luciferian Church.

Certain themes have developed that is recurring in Luciferian literature. In the twentieth century, Luciferianism has increasingly become a term of self-definition and often refers to an understanding of Lucifer that has been significantly separated from its Christian origin, and many forms of Luciferianism also regard their tradition as distinct from Satanism. Many Luciferians see themselves as part of a Gnostic tradition with a focus on knowledge and enlightenment as a path to self-deification, we see this from Order of the Morning Star to Assembly of Light Bearers. Still there is no true or original form of Luciferianism, and the term is fluid and changing.

Clear separation between Luciferianism and Satanism only exist as a theoretical ideal type, and it should be noted that lived practices are far blurrier. We further have the problem that the positive reimagining of Lucifer up to the twentieth century follows the same history of reimagining as with Satan. Thus there are strong links to “Romantic Satanism” within both Luciferianism and Satanism as well as the reception of Milton´s Paradise Lost. The scholar of Religion Masimo Introvigne has for this reason chosen not to make a distinction between Satanism and Luciferianism historically (Introvigne 2016:4). As modern Luciferians however do make this distinction, it is important to understand Luciferians from their own perspective.

To distinguish Satan and Lucifer many Luciferians emphasise the pre-Christian origin of Lucifer, the name being derived from lucem ferens, Latin for Light-bearer, or Light-bringer, and referred originally to referring to Venus as the morning star. In Roman religion there are a few references to Lucifer; sometimes he is paired with Noctifer (Night-bringer, Venus as the evening star) as in the poetry of Catullus. It is debatable if Lucifer was a proper god in Rome or seen as a personification of the morning or as a form of Aura (Dawn). While Luciferianism tends to use the Christian myth of Lucifer’s rebellion against the host of Heaven, many Luciferians want to emphasise the connection to the Roman god to make a clearer distinction between themselves and Satanism. Groups that place an emphasis on the pre-Christian origin of Lucifer are the Order of the Morning Star (which argues more for a Babylonian origin) and the Neo-Luciferian Church. Still, there do not seem to be any Luciferians that only focus on the Roman Pagan god and so aspects from Christian mythology are present even in the Neo-Luciferian Church. They elevate the rebellious nature of Lucifer and use him as a symbol of Enlightenment, presenting their understanding of the nature of Lucifer as (Neo-Luciferian Church website 2013):

Lucifer is the deity of illumination, education and insight.

Lucifer is the deity of pride.Lucifer is the deity of freedom.

Lucifer is the deity of prosperity.

Lucifer is a primeval force.

Christianity established a narrative from the fourth century onwards about a rebellious angel that was seeking to overthrow God but due to his pride fell and became Satan. As this development came rather late in Christian theology the use of the morning star is often not used negatively in the Bible, as in 2 Peter 1:19 where it is in reference to Christ as: “a light shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts.” There are also references that identify Christ with the morning star in Revelations. This has led some Luciferians to see an identification between Lucifer and Christ and thus rejecting their tradition as being anti-Christian One of these was Madelaine Montalban and her Order of the Morning Star.

Luciferians then tend to distinguish themselves between themselves and Satanism seeing the two as separate. Michael Ford presents Luciferianism as a more spiritual philosophy in contrast to Satanism, that is presented as being more materialistic (probably connecting Satanism to LaVey´s Church of Satan). Similar sentiments can be found among other Luciferians. Luciferianism is regarded as being more focused on knowledge and illumination rather than physical gratification. Also, Luciferianism is not a dualistic philosophy while Satanism is seen as being bound in their opposition to Christianity.

For Ford the goal is self-deification using antinomianism, something often found in Satanism as well (Cevjan 2023:230). In his book Apotheosis (2019) he presents ” the Luciferian 11 points of power” that aim to explain the central core of Luciferian belief. The focus is on Lucifer as rebellious and striving for autonomy, and to challenge all forms of dogmatism and authorities, and for the Luciferian to strive to self-deification (apotheosis), not to worship Lucifer or any other god. The eleven points are referred to by the Assembly of Light-Bearers as:

The 11 Points are the basic foundation for the Luciferian Philosophy. They are non-dogmatic and adaptable to the individual to support a Left Hand Path, or self-determined path of power utilizing the continual process of Liberation, Illumination and Apotheosis (https://www.assemblyoflightbearers.org/luciferian-11-points-of-power).

When presenting the differences between Satanism and Luciferianism it´s necessary to remember that Satanism is here presented as the” Other,” and these divisions say little about Satanism as understood by Satanists. Satanism is an equally heterogenic phenomenon, some being materialistic while other are theistic and spiritual, and many forms of Satanism are indistinguishable from Luciferianism, with many using both to describe their practice. One reason to emphasise that there are differences is to create an identity for Luciferianism. In the case of the Neo-Luciferian Church there is an emphasis on the pre-Christian and Gnostic aspects of their teachings that are considered to distinguish their ideals about Lucifer from Satanism. A distinction between Lucifer and Satan is not uncommon and can be found in other forms of Esotericism as well as exemplified by the writings of Robert Ambelain and Jean Chaboseau where Lucifer is related to Venus and contrasted to Satan, ideas also expressed in the modernist poetry of H.D. (1886-1961) (Robinson 2016:107). Luciferians then tend to see Lucifer as less based on Christianity than Satan. While historically indistinguishable, Luciferianism and Satanism have begun to develop as two different forms of spirituality and many Luciferians regard their traditions to be distinct, we need to treat it as such.

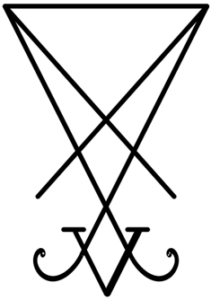

While there is no symbol of Luciferianism that is accepted by all, many Luciferians use the seal of Lucifer as a symbol for Lucifer (Image at right). The symbol was part of the seal of Lucifer originally used in the Grimorium Verum from the eighteenth century onward and has been used by both Michael Ford and Asenath Mason. It has today become one of the most popular symbols for Lucifer and has also been adopted by the Swiz avantgarde metal band Zeal and Ardor who present Lucifer as a force against oppression and subjugation (Zeal and Ardor website. n.d.).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Specific Luciferian groups have distinct rituals, and these also vary in the importance they play. Some, like the Neo-Luciferian Church, uses as structure that are well familiar from other forms of esoteric orders, like co-Masonic orders such as the Ordo Templi Orientis but encourage their members to develop their own understanding and practice. Michael Ford has published extensive ritual writings, often following a ceremonial magical format, often with inspiration from traditional European grimoires and references to non-Wiccan forms of Witchcraft, like those of the Cultus Sabbati. Ford´s books are the most ritualistic, and we find similar formats here as in other twentieth century magical traditions, with the opening of a circle space, developing a body of light, assumption of god-forms, and invocations of “dark entities” (Cevjan 2023:232). Also, the works derived from Dragon Rouge, like those of Thomas Karlsson and Asenath Mason, contain ritual description often focused in the Qliphotic side of the tree of life, often oriented to astral work and travel. Not all Luciferians, however, are as oriented toward rituals, and some are more interested in Luciferianism as a philosophy. All forms of Luciferianism discussed here reject the use of animal sacrifice in their practice; here they are aligned with many forms of Esoteric and Occult traditions that developed in Western Europe and North America in the twentieth century, including most forms of Satanism.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

There are different forms of Luciferian organization, and most Luciferians are probably not even members of a Luciferian organization, which in any event tend to be small, but rather practice alone as a private form of spirituality. An important area for Luciferians to meet is online on platforms like Facebook and Discord groups that can have several thousands of members. Still, this is a poor indication on the level of interest. Organized Luciferian groups many use the structure from co-Masonry and Ceremonial Magical groups like the Hermetic order of the Golden Dawn with fixed degrees. This is mixed with a rejection of authority that can appear paradoxical. Organizations like Assembly of Light Bearers and Temple of Ascending Flame both reject a traditional form of organization and don´t offer conventional forms of membership, being more of a network. Many Luciferian organizations are local in their activities, like the Neo-Luciferian Church, so most Luciferians will work solitary or be members on non-Luciferian groups that still are open to such approaches. There currently are no central figure that can be said to represent most Luciferians.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Due to the association with Satanism, Luciferians have had to face similar forms of prejudice and hostility as Satanists. One example was the protests in Spring, Texas related to the opening of the Greater Church of Lucifer. This opposition is perhaps also a reason Luciferians have tended to distance themselves from Satanism. Like Satanism and Witchcraft, the term has its origin as an accusatory label and little if no distinction was made between Satanism and Luciferianism originally. Even within Pagan and Occult communities the use of Lucifer can be controversial and connected with black magic and Satanism. For Luciferianism this can pose a challenge in two directions, one is that the connection to Satanism means that the same stigma will become associated with them, the other is that a complete rejection of Satanism and separation of Lucifer from Christian mythology can also lead to the symbol losing meaning and cultural relevance.

While there has been controversy around individual groups using Lucifer either as their focus or as one central aspect of their practice, like the Process Church of the Final Judgment, and there have been internal conflicts, most Luciferian organisations seem to have avoided much public controversy.

IMAGES

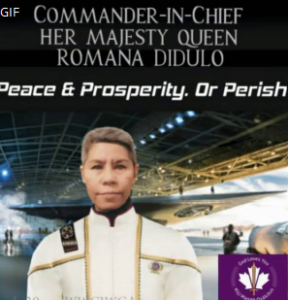

Image #1: William Blake’s illustration of Lucifer as presented in John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

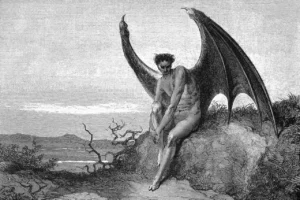

Image #2: Logo of Lucifer: The Light-Bearer.

Image #3: The seal of Lucifer.

REFERENCES

Aseanth Mason: Author and Artist website. 2024. Accessed from https://www.asenathmason.com/ on 17 March 2024.

Assembly of Light Bearers website. 2018. Accessed from https://www.assemblyoflightbearers.org/ on 17 March 2024.

Assembly of Light Bearers website. 2018. “Luciferian 11 points of Power” Accessed from https://www.assemblyoflightbearers.org/luciferian-11-points-of-power on 17 March 2024.

Blakinger, Keri. 2017. “Exorcised: Luciferian church looks to start anew after harassment”. Houston Chronicle, April 23. Accessed from https://www.houstonchronicle.com/lifestyle/houston-belief/article/Exorcised-Luciferian-church-looks-to-start-anew-11093429.php on 17 March 2024.

Cevjan, Olivia. 2023.“Michael W. Ford (The Order of Phosphorus, etc), excerpt from The Bible of the Adversary (2007).” Pp. 317-22 in Satanism: A Reader, edited by Per Faxneld and Johan Nilsson. New York: Oxford University Press

Crowley, Aleister. 1998. Magick: Liber ABA, edited by Hymenaeus Beta. York Beach: Weiser.

De Grimston, Robert. 1970. The Gods and Their People. Chicago: Process Church of the Final Judgment, Chicago Chapter.

Faxneld, Per. 2013. “The Devil is Red: Socialist Satanism in the Nineteenth Century.” Numen 60:558-58.

Faxneld, Per. 2011. “The Strange Case of Ben Kadosh: A Luciferian Pamphlet from 1906 and its Current Renaissance.” Aries 1:1-21.

Flowers, Stephen. 1995. Fire and Ice: Magical Teachings of Germany’s Greatest Secret Occult Order. Woodbury: Llewellyn Publications.

Frisvold, Nicholaj de Mattos. 2023. Seven Crossroads of Night: Quimbanda in Theory and Practice. West Yorkshire: Hadean Press.

Gregorius, Fredrik. 2023a.“The Process Church of the Final Judgement, excerpts from “The Gods on War” (1967) & “The Gods and Their People” (1970).” Pp. 187–216 in Satanism: A Reader, edited by Per Faxneld and Johan Nilsson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gregorius, Fredrik. 2023b. ”Thomas Karlsson (Dragon Rouge), excerpt from Kabbala, kliffot och den goetiska magin (2004).” Pp. 306–316 in Satanism: A Reader, edited by Per Faxneld and Johan Nilsson. New York: Oxford University Press

Granholm, Kennet. 2014. Dark Enlightenment: The Historical, Sociological, and Discursive Contexts of Contemporary Esoteric Magic. Leiden: Brill.

Gregorius, Fredrik. 2013. “Luciferian Witchcraft: At the Crossroads between Paganism and Satanism.” Pp. 229-49 in The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity, edited by Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hakl, Hans Thomas. 2013. “The Magical order of Franternitas Saturni.” Pp. 37-66 in Occultism in a Global Perspectives, edited by Henrik Bogdan and Gordan Djurdjevic. Stocksfield: Acumen Publishing.

Hedenborg White, Manon. 2019. The Eloquent Blood: The Goddess Babalon and the Construction of Femininities in Western Esotericism. New York: Oxford University Press

Hedenborg White, Manon and Fredrik Gregorius. 2019. “The Satanic Temple: Secularist Activism and Occulture in the American Political Landscape.” International Journal For the Study of New Religions. 10:89-110. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.

Howard, Michael. 2016.”Teachings of the Light: Madeline Montalban and the Order of the Morgning Star.” Pp. 55-65 in The Luminous Stone: Lucifer in Western Esotericism, edited by Michael Howard and Daniel A. Schulke. Richmond Vista: Three Hands Press.

Howard, Michael. 2004. The Book of Fallen Angels. Somerset: Capall Bann Publishing.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2016. Satanism: A Social History. Leiden: Brill

Luijk, Ruben van. 2016. Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism. New York: Oxford University Press

Mason, Asenath. 2007. “Necronimicon Gnosis: A practical introduction.” Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein. Accessed from https://deepcuts.blog/tag/asenath-mason/ on 17 March 2024.

Medway, Gareth J. 2001. Lure of the Sinister: The Unnatural History of Satanism. New York: New York University Press.

Neo-Luciferian Church website. 2013. Accessed from https://web.archive.org/web/20131228124306/http://www.neoluciferianchurch.dk/neo-luciferian-church-welcome.php) on 17 March 2024.

Nilsson, Johan. 2023a. ”Ben Kadosh (aka Carl William Hansen), Den ny morgens gry (1906).” Pp. 122-34 in Satanism: A Reader, edited by Per Faxneld and Johan Nilsson. New York: Oxford University Press

Nilsson, Johan. 2023b. ”Aleister Crowley, “Hymn to Lucifer” (undated) & excerpt from The Book of Thoth (1944).” Pp. 153-73 in Satanism: A Reader, edited by Per Faxneld and Johan Nilsson. New York: Oxford University Press.

Phillips, Julia. 2012. Madeline Montalban: The Magus of St Giles. London: Neptune Press.

Rhodes, Henry Taylor Fowkes. 1965. The Satanic Mass: A Sociological and Criminological Study. London: Arrow.

Robinson, Matte. 2016. The Astral H.D. Occult and Religious Sources and Contexts for H.D´s Poetry and Prose. New York: Bloomsbury.

Schock, Peter A. 2003. Romantic Satanism: myth and the historical moment in Blake, Shelley and Byron. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Strube, Julian. 2016. “The ‘Baphomet’ of Eliphas Lévi: Its Meaning and Historical Context.” Correspondences 4. Accessed from https://correspondencesjournal.com/15303-2/) on 17 March 2024.

Temple of Ascending Flame website. n.d. “About Us.” Accessed from http://ascendingflame.com/index.php/about-us/) on 17 March 2024.

Werblowsky, R. J. Zwi. 2007. Lucifer and Prometheus: A Study of Milton´s Satan. Oxon: Routledge.

Zeal and Ardor website. n.d. Accessed from https://www.zealandardor.com/ on 17 March 2024.

Publication Date:

23 March 2024

undress while Hopeful lay with the wife and Gloria with the husband, although without any sexual involvement (Beale 2009:47). Marriage ceremonies in the community paused while the couple went to a special room to consummate the marriage and then returned for a celebration. [Image at right] There were also stories of nakedness in the spa pool and couples making love simultaneously in a common room. (Beale 2009:49). Hopeful would apparently sometimes attend the consummation of marriages (Tarawa 2017:54).

undress while Hopeful lay with the wife and Gloria with the husband, although without any sexual involvement (Beale 2009:47). Marriage ceremonies in the community paused while the couple went to a special room to consummate the marriage and then returned for a celebration. [Image at right] There were also stories of nakedness in the spa pool and couples making love simultaneously in a common room. (Beale 2009:49). Hopeful would apparently sometimes attend the consummation of marriages (Tarawa 2017:54).

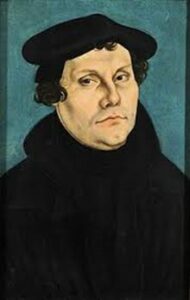

engaging in similar religious rituals. Menno Simons [Image at right] was a prominent organizer of these groups of people and Mennonites draw their name from him.

engaging in similar religious rituals. Menno Simons [Image at right] was a prominent organizer of these groups of people and Mennonites draw their name from him.

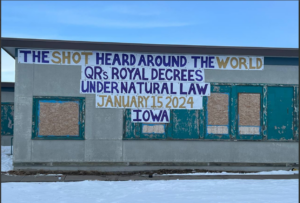

produced by the oxidation of adrenaline that it is alleged global elites harvest from kidnapped children to ingest as an elixir of youth), organ harvesting, and the manufacture and sale of children for sex trafficking (Sarteschi 2023). She claimed that she single-handedly removed these individuals from Canada, and in so doing she prevented World War III. As a result of her great effort, she was bestowed the title of Queen. [Image at right]

produced by the oxidation of adrenaline that it is alleged global elites harvest from kidnapped children to ingest as an elixir of youth), organ harvesting, and the manufacture and sale of children for sex trafficking (Sarteschi 2023). She claimed that she single-handedly removed these individuals from Canada, and in so doing she prevented World War III. As a result of her great effort, she was bestowed the title of Queen. [Image at right]

distributed a series of, at times, apocalyptic private revelations allegedly received by the group’s founder Debra Burslem (b.1953), in the form of diaries entitled What Might God Say to Me Today…in Australia. [Image at right]

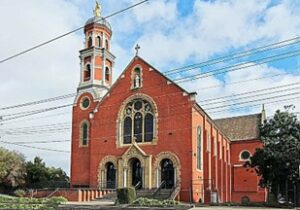

distributed a series of, at times, apocalyptic private revelations allegedly received by the group’s founder Debra Burslem (b.1953), in the form of diaries entitled What Might God Say to Me Today…in Australia. [Image at right] that Debra was overly disciplinarian in her treatment of children. Following leaving the teaching profession, Debra Geilesky went into the real estate industry with her then husband, Gordon. The couple’s fortunes were not positive, and according to contemporary reports they were near bankruptcy by the mid-1990s. According to media reports it was around this time that Debra became increasingly involved in the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, through the parish of Our Lady Help of Christians in East Brunswick, Melbourne. [Image at right]

that Debra was overly disciplinarian in her treatment of children. Following leaving the teaching profession, Debra Geilesky went into the real estate industry with her then husband, Gordon. The couple’s fortunes were not positive, and according to contemporary reports they were near bankruptcy by the mid-1990s. According to media reports it was around this time that Debra became increasingly involved in the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, through the parish of Our Lady Help of Christians in East Brunswick, Melbourne. [Image at right]

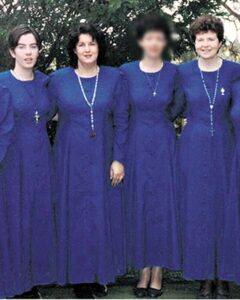

restrictions on Christmas trees and on the celebration of birthdays, Mother’s Day, and even Easter. Within the group’s community, followers were encouraged to tithe to the movement, often in the form of cash, and to work on its properties. The group was conspicuous for its long blue robes or dresses which were worn both in the cloister and in the wider community. [Image at right]

restrictions on Christmas trees and on the celebration of birthdays, Mother’s Day, and even Easter. Within the group’s community, followers were encouraged to tithe to the movement, often in the form of cash, and to work on its properties. The group was conspicuous for its long blue robes or dresses which were worn both in the cloister and in the wider community. [Image at right]