Nova Cana

NOVA CANA TIMELINE

1947 (May 2): Six year old Angela Volpini received her first Holy Communion in the village of Casanova Staffora, Lombardy, Italy, in the Apennine mountain range.

1947 (June4): Angela, having turned seven on the June 2, experienced her first apparition of the Virgin Mary at a place called Bocco on the hill overlooking Casanova Staffora.

1947 (July 4): The second apparition occurred in which the vision confirmed that she is Mary. This established a series of apparitions on the fourth of the month over nine years.

1947 (October 4): Solar prodigies, reminiscent of other apparitions especially Fátima, were reported during the apparitions.

1947 (November or December): The diocese of Tortona, having noticed the large crowds gathering at Casanova Staffora, began an investigation.

1948 (April 18): The crucial Italian general election of 1948 took place. Christian Socialists gained power against the left-wing coalition of Socialists and Communists.

1950 (November 4): Solar prodigies, reminiscent of other apparitions especially Fátima, were reported during the apparitions.

1950: The building of the cappellina (English: “small chapel”) began at the site of the apparitions; the present statue was installed in 1960.

1952 (June 6): The first indications of the decision of the diocesan commission of enquiry became known. Angela’s character was praised and she was declared mentally sound, but the Church took the position that there was no evidence to judge her apparitions as supernatural.

1955 (November 4): The last apparition in the regular series occurred, but the Virgin promised that she would return once more.

1956 (June 4): The final apparition took place in which the Virgin foretold a great spiritual revival after a period of instability among the nations. She said that God is merciful and would spare the people punishment.

1957 (August 15): The Diocese of Tortona agreed that a church could be built at Bocco as a Marian shrine.

1958 (April 9): Angela presented a file of her messages to Pope Pius XII at St Peter’s in Rome.

1958 (June 22): The first stone of the new church was blessed by senior priest Monsignor Ferreri, with many pilgrims present.

1958: The association Nova Cana was founded by Angela at the age of eighteen.

1959 (November 4): The bell of the new church was blessed by Canon Caldi, delegate of Bishop Melchiori of Tortona.

1962 (June 4): Monsignor Rossi, also a delegate of the bishop of Tortona, celebrated the Mass at which the new church was blessed and inaugurated.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The apparitions of Casanova Staffora occurred in the context of post-war Italy, amid a very unstable political situation. In 1947, post-war Italy was in a period of intense uncertainty as to whether the future government would be Christian Democrat, and thus supportive of the Church, or Socialist/Communist, with the threat to the Catholic way of life that this would have suggested in the first half of the twentieth century and into the Cold War period. The Christian Democrats won the crucial election in April 1948 and stayed in power for some decades (among others, see Ginsborg 1990).

Believers in Casanova Staffora agree that the national context was relevant to the beginning of the shrine; the decade 1944-1954 saw more Marian apparitions in Italy than in any other modern period. Angela first reported seeing the Virgin Mary on June 4, 1947, having passed her seventh birthday two days before. The first message from the Virgin Mary was: “I have come to teach the way to happiness on this Earth … Be good, pray and I will be the salvation of your nation” (Angela Volpini’s website 2016). The first part of this message is written on a board at the site of the apparition, the cappellina (a small edifice containing a statue and marked off by a fence). For Angela, this first apparition established everything that she has since believed about God, Mary, and humanity:

It was the aim of the human life, it was all human possibilities, it was what gave meaning to every human living. It was the joy of the Creator. With great approximation I can say that I have contemplated the universal world, through the eyes of the Madonna I have seen all mankind … I saw all the story of human beings (Angela Volpini’s website 2016).

At the time of this first vision, Angela [Image at right] was a young girl in a farming family, pasturing the cows with other children in a hillside area  known as Bocco, a few hundred metres outside the main village. At about four o’clock in the afternoon she recalls sitting on the grass putting flowers into bunches. She felt someone lift her up and, thinking it was her aunt, turned round to see an unknown woman with a beautiful face. Angela was a sole visionary, as the other children did not share this experience (one of the characteristics of a successful and long-term apparition movement is clarity over whom the Madonna is speaking through; a multiplicity of voices may harm the reputation of the case). Angela immediately identified her vision as the Virgin Mary, and this was confirmed in the second apparition one month later on the July 4, 1947, when the vision declared herself to be Mary. This was further clarified on the August 4, when she referred to herself as “Mary, Help of Christians, Refuge of Sinners.” These are traditional titles of Mary.

known as Bocco, a few hundred metres outside the main village. At about four o’clock in the afternoon she recalls sitting on the grass putting flowers into bunches. She felt someone lift her up and, thinking it was her aunt, turned round to see an unknown woman with a beautiful face. Angela was a sole visionary, as the other children did not share this experience (one of the characteristics of a successful and long-term apparition movement is clarity over whom the Madonna is speaking through; a multiplicity of voices may harm the reputation of the case). Angela immediately identified her vision as the Virgin Mary, and this was confirmed in the second apparition one month later on the July 4, 1947, when the vision declared herself to be Mary. This was further clarified on the August 4, when she referred to herself as “Mary, Help of Christians, Refuge of Sinners.” These are traditional titles of Mary.

Pilgrims soon came in their thousands to Casanova Staffora. By the autumn of 1947, it was national news; newspapers such as La Stampa and Oggi covered the story. The crowds participated in the dramatic events: the title of Ferdinando Sudati’s book (2004) promoting the apparitions, Dove posarano i suoi piedi (“Where her feet rested”), refers to the fact that pilgrims claimed to have seen the invisible Mary’s feet imprinted on the flowers which had been placed to honour her. Angela’ gestures and charismatic smile assured them that Mary was present; she presented flowers to the Virgin and children to kiss and bless, and she carried the invisible Christ child in her arms. The shrine overlooks the beauty of the Apennine river valley below, providing a memorable backdrop to the scene. In the late 1940s, the hillside was literally covered with people. Like many Catholic visionaries, Angela as a child seer attracted a great deal of attention. Many priests visited too, and the diocesan authorities at Tortona began an investigation. Angela describes how intensively she underwent interviews by priests, journalists, and doctors: she recalls being taken from her home for about forty days and kept in a room without windows. This pressure was applied to see if Angela would admit that she had falsified the visions, but she did not.

Angela’s apparitions were experienced in a series, like other apparitions, in this case on each fourth of the month up until June 1956, with some breaks over the years. A series helps to create a pattern of pilgrimage. The messages were not unfamiliar in the Marian apparition tradition: the Virgin requested prayer, penance, a chapel and, eventually, a larger sanctuary. The Casanova Staffora apparitions also echoed the famous apparitions of Fátima in 1917, increasingly well-known across Europe in the late 1940s, with the anticipation of a great miracle, warnings of divine punishment, and sensational reports of movements of the sun, for the first time on the October 4, 1947 and then later on the November 4, 1950, three days after the definition of the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary by Pope Pius XII.

Angela’s apparitions concluded on the June 4, 1956, and she says that she has not had any further experiences of this kind. The message of this final vision was important in determining future directions. According to Angela, Mary said:

The great miracle has already begun, and once again the merciful God has spared the earth his punishment. Many people will come back to the Church and the world will finally have peace. But before that happens, many nations will be shaken and renewed. Always remember my last words: love God sincerely, love your heavenly mother, love each other. I will not return, but I will give the signs and graces promised, so that you may know that I will always be with you (Sudati 2004:174, my translation).

Therefore the sixteen year-old Angela, immediately after the final apparition, announced that the miracle would be a spiritual renewal which had already begun. This, and the removal of the threats of divine chastisement, distinguished Casanova Staffora from other apparitions in the second half of the twentieth century that emphasised apocalyptic miracles and punishments. Angela’s mission was to be more grounded and more optimistic about the direction of human society. Angela remembers that:

Mary told me that the miracle would be an increase of public conscience and awareness. In 1958, I founded the organisation Nova Cana to help this process. Nova Cana attempts to focus people’s attention on the coming of the Kingdom of God, just as the wedding at Cana was the manifestation of the divinity in Jesus. It is a centre for dialogue. I realised the need for a space in which people could reflect on their desire for fulfilment and come to know that it could be realised (Interviews, October 28-31, 2015, also quoted further below).

Despite priestly support for Angela, two diocesan bishops of Tortona, Egisto Melchiori and Francesco Rossi, announced that they could not authenticate the apparitions, in 1952 and 1965 respectively. They expressed their appreciation of Angela’s character and the orthodoxy of her message, and could not rule out the possibility of a supernatural origin. However, they felt that the apparitions were more likely to have been triggered by the experience of her first communion and her coming into contact with the story of Fátima. Nonetheless, the diocese did grant permission for the building of a shrine church at Bocco, the first stone was laid in 1958, and the building was formally blessed by an episcopal delegate in 1962. The relationship with the Church has not always been smooth, but the diocese continues to provide support by appointing a priest to celebrate Mass at Bocco once a month. Furthermore, Angela has enjoyed strong friendships with many priests and monks, most notably the priest and politician Don Gianni Baget Bozzo (1925-2009) and the monk Frate Ave Maria (1900-1964) of the hermitage of Sant’ Alberto di Butrio.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Angela’s messages from Mary are optimistic about human potential in a way that anticipates later Catholic movements, such as Creation Spirituality and Fully Human, Fully Alive. They also have non-Catholic parallels in the Human Potential Movement in the United States arising in the 1960s. For Angela, however, this vision was already fully present in the initial apparition on the June 4, 1947, when Mary said that “I have come to teach the way to happiness on this Earth.” Angela says that:

Mary is an icon of the history of humanity. All human beings possess the opportunity for fulfilment and entry into the domain of the divine, and Mary is the one in whom this is fully realised.

While Angela refers to the importance of human liberation, she does not associate herself with liberation theology per se, nor with feminist theology either. Nevertheless, she does agree that being a woman has made it more difficult for her voice to be heard in the Church.

Angela regards Mary as humanity fulfilled: she is the first human being to achieve fulfilment and thus an exemplar for all others. Mary has a strong relationship of communion with God, and Angela (aware of possible interpretations of her message) makes clear that God and Mary are absolutely distinct and not to be confused. The goal of every human being is Mary but also for each person to be unique. To quote Angela:

Fulfilment is development of our own uniqueness, by which we are in communion with God. The concept of the divine is based on the personal; it is the original source of oneself. When humanity is fulfilled, we can enter the domain of the divine. There is a choice, a choice to love.

God’s project was incarnation and God chose Mary. This was because she was the one human being who was acknowledging and realising her potential. She committed herself to her own desire to love and was not bound by the culture around her. She discovered that the secret of God was that this could be done.

Angela also says that:

This is a vision of potential but it depends on us. The task of receiving the message is our responsibility. Traditional believers of all religions prefer to delegate this to God. Mary relied upon herself. Mary was independent of God in order to meet him in love. This is the project of all human beings: 1) To be oneself, which is the purpose of creation, and 2) to love, which is to grasp the human quality. Other things follow.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

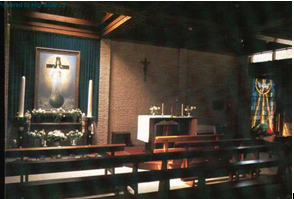

The shrine at Bocco, Casanova Staffora, [Image at right] is part of the Roman Catholic diocese of Tortona. Therefore religious rituals follow the Catholic sacraments which are administered by priests of the diocese. Angela Volpini and practicing members of Nova Cana remain within the Catholic Church.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Angela played her part in the message of renewal by founding a new association for prayer, Nova Cana, in 1958. Its target membership was young, its principles respect and love for humanity, and the unity of political thought and religious life. Unlike other 20th century Catholic movements such as Opus Dei, the Nova Cana movement has tended to sit on the left of the political spectrum rather than the right. This is testified to by its links with the Latin American churches, and contacts with bishops with liberation theology credentials such as Helder Camara and Oscar Romero. Angela says that she was invited by Latin American bishops to discuss the themes of the Second Vatican Council to which her own vision of human potential corresponded. In the 1960s and 1970s, Nova Cana attracted students and left-wing workers, and was accused by Church members of being communist. While Angela accepts that Nova Cana and its humanitarian project did largely resonate with the political left, she also states that it was never communist (socialism and communism can be clearly distinguished in Italian political history). After the difficulties with the Church that this caused, Angela was reconciled to the parish in the 1980s and has established herself as an influential Catholic teacher and speaker; several books and numerous articles have been written about her and she has appeared several times on television. In recent years, bishops of Tortona have visited the shrine at Bocco and it continues to attract pilgrims.

Angela describes Nova Cana in the following way:

Nova Cana gave the impulse to the birth of initiatives whose purpose was to value those economic subjects that operated in the local area under the conditions of long term marginalisation. Thanks to the self-esteem boost that Nova Cana was able to inject to the subjects involved, solitary farmers were transformed into modern social entrepreneurs. For example livestock and farming cooperatives were created (Angela Volpini website 2016).

Nova Cana runs successful conferences, seminars, and courses, and it has enabled Angela to publish several books, with distribution in the thousands. Angela’s husband, Giovanni Prestini, a sociologist, has contributed to the setting up of co-operatives in the agricultural regions surrounding Casanova Staffora. Nova Cana works to promote self-esteem in poor communities and thus help people realise their potential for economic, social, and political development. Nova Cana projects have also been launched in Peru, Brazil, Turkey, and South Africa.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Nova Cana has always existed at a distance from the official Catholic Church, despite the support of many priests and the visits of bishops to the shrine at Bocco. Early on, while Angela was a child, the Church was not persuaded to authenticate the apparitions, a decision which still stands. Later on, the adult Angela’s interpretation of her visions differed in some aspects to Catholic teachings as established by the Vatican. However, this does not make Nova Cana a sect, as the community has never made a complete break from the Church. All of Angela’s teachings reflect the Catholic culture into which she was born.

One major contrast between Angela’s vision and the Church’s official teaching consists in the fact that she believes we are all immaculate. This does not conform to the doctrine of the Church, in which Mary is the sole instance of immaculate conception. Angela contrasts her own vision to Church doctrine by saying that the Church emphasises God’s initiative and Jesus’ redemption, whereas she puts much more weight on human fulfilment and belief as definitive in the liberation of humanity. For her, Jesus was more a revealer of our potential than a redeemer; she is against passive views of human involvement in salvation. She says:

This has been my vocation, to help people become more empowered in respect of themselves and the world, and live their desires which are the starting point. The projects of Nova Cana are partial examples of this empowerment. The divine in man is a potential and a choice. One must see this potential in humanity. The message was more about humanity than about God. Being faithful to oneself is at the core of the relationship with God. Without this, one cannot be faithful to others. The Church does not emphasise this message; rather the contrary, as the Church teaches that man is a sinner and requires a saviour, but in fact the potential for salvation is internal. Jesus, by his words, actions, life, death and resurrection, revealed the potential for liberation to us. Salvation is our accomplishment and our value.

Angela sees these ideas as central to the vision of the Second Vatican Council. Like others who followed radical interpretations of the Council, such as Catholic liberation and feminist theologians and some progressive moral theologians, Angela regards herself as a Catholic but not one that would accept the view of the Magisterium without question. She says that: “Unity is very important but not at the expense of the conscience. Unity is not conformity, but unity in diversity.”

Divergence between the hierarchy of the Church and visionaries who are often female as alternative sources of authoritative teaching is more common than perceived to be the case (see Maunder 2016). The assumption that visionaries merely restate Church teaching and thereby exist only to reinforce the status of the Vatican is not justified. This viewpoint can be derived perhaps from Bernadette Soubirous, famous in the Church as the model visionary who said that Mary referred to herself as “the Immaculate Conception” just four years after Pius IX declared this as dogma. She is the most well-known seer, perhaps, but not the normal case.

The Church-approved vision, although desired by devotees of apparitions, is the exception rather than the rule. In twentieth century Europe, only four apparitions (at Fátima [Portugal, visions in 1917], Beauraing, Banneux [both Belgium, 1932-1933], and Amsterdam [the Netherlands, 1945-1949]) were accorded full approval by the diocesan bishop. Others achieved the status of official diocesan shrines but without recognition of the visions themselves: examples include the German shrines Heede (1937-1940), Marienfried (1946) and Heroldsbach (1949-1952). Many more gained a compromise whereby the Church accepted the existence of the shrine and gave some support, such as blessing of the shrine buildings and provision of priests to celebrate Mass. This is the case at Casanova Staffora. Other famous examples of compromise include San Sebastian de Garabandal (Spain, 1961-1965), San Damiano (Italy, 1964-1981) and Medjugorje (Bosnia-Herceovina, 1981-date).

Finally, when Angela Volpini experienced apparitions watched by thousands of pilgrims in the 1940s and 1950s, this was perfectly natural and normal in the context of the time. The child seer has been understood in Catholicism as enjoying special divine favour because  of their innocence, a view repeated by Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, in The Message of Fatima (Bertone and Ratzinger 2000). However, my recent book, Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th Century Catholic Europe asks whether putting child seers under the spotlight of public attention would be regarded as acceptable any longer given the developing concern about child welfare. Gilles Bouhours of Espis in France (where visions occurred to a group of children between 1946 and 1950) was only two years old when he was recognised as a visionary. Unsurprisingly, then, most prominent visionaries after the early 1980s (when the Medjugorje children began to have visions) have been adults. The revival of Catholic devotion due to apparitions to rural children while animal herding [Image at right] has been a standard motif in Europe across the centuries, but this phenomenon is disappearing now.

of their innocence, a view repeated by Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, in The Message of Fatima (Bertone and Ratzinger 2000). However, my recent book, Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th Century Catholic Europe asks whether putting child seers under the spotlight of public attention would be regarded as acceptable any longer given the developing concern about child welfare. Gilles Bouhours of Espis in France (where visions occurred to a group of children between 1946 and 1950) was only two years old when he was recognised as a visionary. Unsurprisingly, then, most prominent visionaries after the early 1980s (when the Medjugorje children began to have visions) have been adults. The revival of Catholic devotion due to apparitions to rural children while animal herding [Image at right] has been a standard motif in Europe across the centuries, but this phenomenon is disappearing now.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of Angela Volpini worshiping as a young child.

Image #2: Photograph of the church at Bocco.

Image #3: Photograph of Angela Volpini herding cattle as a young woman.

REFERENCES*

* Quotes in the text from Angela Volpini that are unreferenced are from interviews during my fieldwork in Casanova Staffora, October 28 – 31 2015.

Angela Volpini’s website. 2016. Accessed from http://www.angelavolpini.it on 5 November 2016. Translations by Laura Casimo.

Bertone, Tarcisio and Ratzinger, Joseph. 2000. The Message of Fatima. Vatican City: Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Accessed from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20000626_message-fatima_en.html on 5 November 2016.

Ginsborg, Paul. 1990. A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics 1943–1988. London: Penguin.

Maunder, Chris. 2016. Our Lady of the Nations: Apparitions of Mary in 20th-Century Catholic Europe. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Nova Cana’s website. 2016. Accessed from http://www.novacana.it/index.htm on 5 November 2016.

Sudati, Ferdinando. 2004. Dove Posarono i suoi Piedi: Le Apparizioni Mariane di Casanove Staffora (1947–1956). Third Edition. Barzago: Marna Spiritualità.

Volpini, Angela. 2003. La Madonna Accanto a Noi. Trento: Reverdito Edizioni.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Boss, Sarah J., ed. 2007. Mary: The Complete Resource. London and New York: Continuum.

Graef, Hilda and Thompson, Thomas A. 2009. Mary: A History of Doctrine and Devotion, New Edition. Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria.

Rahner, Karl. 1974. Mary, Mother of the Lord. Wheathampstead: Anthony Clarke.

ACKNOWLDEGEMENTS

Grateful thanks to Angela Volpini for agreeing to be interviewed by the author at Casanova Staffora in October 2015, to Maria Grazia Prestini for interpreting at these interviews, and to the Nova Cana community for providing excellent hospitality. Thank you also to Laura Casimo for translating passages from Angela Volpini’s website.

Publication Date:

10 November 2016

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, the Virgin Mary. They named her Our Lady of the Conception Who Appeared from the Waters, which was subsequently shortened to Our Lady Aparecida. The men wrapped her in cloth, continued fishing, and soon had enough fish to provide a sumptuous feast. The appearance of Our Lady of Aparecida came to be regarded as a double miracle. To the faithful, it was miraculous, first, that the fishermen found both the body and the head of the statue simultaneously and, second, that finding the statue was followed by a bountiful harvest of fish. This miracle resonates with a biblical narrative in which Jesus appears to unsuccessful fishermen, telling them to cast their nets again, which leads them to an abundant catch.

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, the Virgin Mary. They named her Our Lady of the Conception Who Appeared from the Waters, which was subsequently shortened to Our Lady Aparecida. The men wrapped her in cloth, continued fishing, and soon had enough fish to provide a sumptuous feast. The appearance of Our Lady of Aparecida came to be regarded as a double miracle. To the faithful, it was miraculous, first, that the fishermen found both the body and the head of the statue simultaneously and, second, that finding the statue was followed by a bountiful harvest of fish. This miracle resonates with a biblical narrative in which Jesus appears to unsuccessful fishermen, telling them to cast their nets again, which leads them to an abundant catch. of Aparecida on May 31 of the next year. In 1931, Getulio Vargas seized power in Brazil after a military coup d’etat. While in power he sought to create a unified Brazil and so promoted a semi-official Catholic Church with Our Lady of Aparecida as its sign. Vargas’s reign as dictator ended in 1945, but by then the plans were already underway for a new basilica. In 1959, Our Lady of Aparecida was moved to the unfinished building. In the meantime, after a period of civilian government, military rule returned in 1964. Catello Branco, who was designated as president, symbolically named Our Lady of Aparecida to be the highest general of the Brazilian Army in an attempt to restrict how public spaces could be used. When the new basilica was finally completed in 1980, Pope John Paul II visited and blessed her shrine. His visit led to the creation of a law which named October 12, her likely date of discovery, an official national Brazilian holiday. The mixing of religious and political legitimation for Our Lady of Aparecida has been controversial but has also meant that Our Lady has been not only a symbol of the Catholic Church but also of Brazil as a nation (Johnson 1997:129).

of Aparecida on May 31 of the next year. In 1931, Getulio Vargas seized power in Brazil after a military coup d’etat. While in power he sought to create a unified Brazil and so promoted a semi-official Catholic Church with Our Lady of Aparecida as its sign. Vargas’s reign as dictator ended in 1945, but by then the plans were already underway for a new basilica. In 1959, Our Lady of Aparecida was moved to the unfinished building. In the meantime, after a period of civilian government, military rule returned in 1964. Catello Branco, who was designated as president, symbolically named Our Lady of Aparecida to be the highest general of the Brazilian Army in an attempt to restrict how public spaces could be used. When the new basilica was finally completed in 1980, Pope John Paul II visited and blessed her shrine. His visit led to the creation of a law which named October 12, her likely date of discovery, an official national Brazilian holiday. The mixing of religious and political legitimation for Our Lady of Aparecida has been controversial but has also meant that Our Lady has been not only a symbol of the Catholic Church but also of Brazil as a nation (Johnson 1997:129). was first moved into its prayer chapel near the river, miraculous events were reported: candles that blew out in the chapel would relight, a slave running from a cruel master prayed to the idol for freedom and his chains were released, a blind girl received sight, and a man who wished to harm the statue found his horse’s feet “locked fast to the ground at the entrance of the building” when he tried to enter the chapel (“Our Lady Aparecida” n.d.). Further, while the new basilica was being constructed, it was reported that the every evening the statue was moved to reside in the in progressing Basilica, but every morning, she would appear back in the old Basilica. This went on for several years. Eventually, it is believed, the statue gave up and realized that no member of the clergy was going to heed her desire to remain at her old resting place.

was first moved into its prayer chapel near the river, miraculous events were reported: candles that blew out in the chapel would relight, a slave running from a cruel master prayed to the idol for freedom and his chains were released, a blind girl received sight, and a man who wished to harm the statue found his horse’s feet “locked fast to the ground at the entrance of the building” when he tried to enter the chapel (“Our Lady Aparecida” n.d.). Further, while the new basilica was being constructed, it was reported that the every evening the statue was moved to reside in the in progressing Basilica, but every morning, she would appear back in the old Basilica. This went on for several years. Eventually, it is believed, the statue gave up and realized that no member of the clergy was going to heed her desire to remain at her old resting place. wherein the pilgrims may promise to accomplish something in the name of Our Lady of Aparecida if she will grant them something. The second is a Territorial Bond, wherein pilgrims bring items to be blessed by the statue to improve their relationship with Aparecida. Finally, there is Inclusion, which connotes that, while there are many rituals associated with Catholic Saints, all of them are related and equally important. This is directly contrasted, though, by the attitudes of pilgrims who come to see the idol. They generally arrive to visit the statue and nothing more. They do not confess their sins or hold much stock in the other aspects of Catholicism. In their minds, the statue of Our Lady of Aparecida is the only reality they need.

wherein the pilgrims may promise to accomplish something in the name of Our Lady of Aparecida if she will grant them something. The second is a Territorial Bond, wherein pilgrims bring items to be blessed by the statue to improve their relationship with Aparecida. Finally, there is Inclusion, which connotes that, while there are many rituals associated with Catholic Saints, all of them are related and equally important. This is directly contrasted, though, by the attitudes of pilgrims who come to see the idol. They generally arrive to visit the statue and nothing more. They do not confess their sins or hold much stock in the other aspects of Catholicism. In their minds, the statue of Our Lady of Aparecida is the only reality they need. around her shoulders and a large crown adorns her head), what honors and special titles she has been given, and the official date for her celebration are controlled by various units of the Catholic church, one might say that actual leadership resides with the pilgrims. When Pope John Paul II visited Brazil in 1980 and great preparation was made to receive the expected increase in pilgrims to Aparecida to coincide with his visit, officials were surprised when no more than the normal 300,000 appeared, as opposed to the 2,000,000 who were expected. It seems that the pilgrims intended to follow their traditional schedules with regard to the Lady and to wait until the Pope visited their own locales to pay tribute to him.

around her shoulders and a large crown adorns her head), what honors and special titles she has been given, and the official date for her celebration are controlled by various units of the Catholic church, one might say that actual leadership resides with the pilgrims. When Pope John Paul II visited Brazil in 1980 and great preparation was made to receive the expected increase in pilgrims to Aparecida to coincide with his visit, officials were surprised when no more than the normal 300,000 appeared, as opposed to the 2,000,000 who were expected. It seems that the pilgrims intended to follow their traditional schedules with regard to the Lady and to wait until the Pope visited their own locales to pay tribute to him. Marian seer. Lueken’s first mystical experiences followed the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy on June 5, 1968. The next day, as Kennedy lay in the hospital, Lueken was praying for his recovery when she felt herself surrounded by an overwhelming fragrance of roses. Although the senator died late that night, the inexplicable smell of roses continued to haunt her. Soon she would wake up to find she had written poetry that she could not remember writing. She had prayed to St. Therese of Lisieux to save senator Kennedy and suspected that Therese was somehow the true author of these poems. She discussed these experiences with the priests at her parish church, St. Robert Bellarmine’s, but she felt they did not take her seriously. Her husband, Arthur, also discouraged any discussion of miracles.

Marian seer. Lueken’s first mystical experiences followed the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy on June 5, 1968. The next day, as Kennedy lay in the hospital, Lueken was praying for his recovery when she felt herself surrounded by an overwhelming fragrance of roses. Although the senator died late that night, the inexplicable smell of roses continued to haunt her. Soon she would wake up to find she had written poetry that she could not remember writing. She had prayed to St. Therese of Lisieux to save senator Kennedy and suspected that Therese was somehow the true author of these poems. She discussed these experiences with the priests at her parish church, St. Robert Bellarmine’s, but she felt they did not take her seriously. Her husband, Arthur, also discouraged any discussion of miracles. Bellarmine’s church in Bayside “when the roses are in bloom.” On the night of June 18, 1970, Lueken knelt alone in the rain praying the rosary before a statue of the Immaculate Conception outside her church. Here, Mary appeared to Lueken and instructed her that she was a bride of Christ, that she wept for the sins of the world, and that everyone must return to saying the rosary. Lueken announced that a national shrine should be built on the church grounds and that Mary would henceforth appear there on every Catholic feast day. Over the next two years, a small body of followers joined Lueken in her vigils in front of the statue. At each appearance, Lueken would deliver a “message from heaven,” spoken through her by Mary as well as a growing cast of saints and angels. These messages typically included jeremiads about the weight of America’s sins and warnings of a coming chastisement (Lueken 1998: vol. 1).

Bellarmine’s church in Bayside “when the roses are in bloom.” On the night of June 18, 1970, Lueken knelt alone in the rain praying the rosary before a statue of the Immaculate Conception outside her church. Here, Mary appeared to Lueken and instructed her that she was a bride of Christ, that she wept for the sins of the world, and that everyone must return to saying the rosary. Lueken announced that a national shrine should be built on the church grounds and that Mary would henceforth appear there on every Catholic feast day. Over the next two years, a small body of followers joined Lueken in her vigils in front of the statue. At each appearance, Lueken would deliver a “message from heaven,” spoken through her by Mary as well as a growing cast of saints and angels. These messages typically included jeremiads about the weight of America’s sins and warnings of a coming chastisement (Lueken 1998: vol. 1). The Pilgrims were also known as “the White Berets” for the hats they wore. Like Lueken, they were disturbed by the reforms of Vatican II. The White Berets declared Lueken to be “the seer of the age” and printed her messages from heaven in their newsletter. They also began organizing buses that transported hundreds of pilgrims to attend vigils in front of Lueken’s parish church. Lueken’s messages began to hint at global conspiracies, a coming nuclear war, and a celestial body called “The Fiery Ball of Redemption” that would soon strike the Earth, causing planet-wide destruction.

The Pilgrims were also known as “the White Berets” for the hats they wore. Like Lueken, they were disturbed by the reforms of Vatican II. The White Berets declared Lueken to be “the seer of the age” and printed her messages from heaven in their newsletter. They also began organizing buses that transported hundreds of pilgrims to attend vigils in front of Lueken’s parish church. Lueken’s messages began to hint at global conspiracies, a coming nuclear war, and a celestial body called “The Fiery Ball of Redemption” that would soon strike the Earth, causing planet-wide destruction.

contradicted Catholic doctrine (Goldman 1987). Mugavero’s findings were sent to three hundred bishops throughout the United States and one hundred conferences of bishops around the world. Despite this censure from Church authorities, Lueken’s followers still identify as Catholics in good standing and they defend their views citing canon law. They contend that Lueken’s visions never received a proper investigation led by a bishop, and that the diocese’s dismissal of Lueken is therefore not legitimate. If anyone has violated Church law, they argue, it is the modernists whom Lueken condemned for receiving communion in the hand and other ritual transgressions that go against long-established Catholic tradition.

contradicted Catholic doctrine (Goldman 1987). Mugavero’s findings were sent to three hundred bishops throughout the United States and one hundred conferences of bishops around the world. Despite this censure from Church authorities, Lueken’s followers still identify as Catholics in good standing and they defend their views citing canon law. They contend that Lueken’s visions never received a proper investigation led by a bishop, and that the diocese’s dismissal of Lueken is therefore not legitimate. If anyone has violated Church law, they argue, it is the modernists whom Lueken condemned for receiving communion in the hand and other ritual transgressions that go against long-established Catholic tradition. pilgrimages to Flushing Meadows with followers from around the world. But in 1997, a schism occurred between the shrine’s director, Michael Mangan, and Lueken’s widower, Arthur Lueken. A judge ruled in favor of Arthur Lueken, declaring him president of Our Lady of the Roses Shrine (OLR) and awarding him all of the organization’s assets and facilities. Undaunted, Mangan formed his own group, Saint Michael’s World Apostolate (SMWA). Both groups continued to arrive at the movement’s sacred site in Flushing Meadows where they held rival vigils. Once again, police were sent out to keep the peace (Kilgannon 2003). Today, this conflict has thawed into a detente. Their celebrations of Catholic feast days are sometimes timed such that only one group will be present in the park on a given day. For events where both groups must be present, such as Sunday morning holy hour, they alternate which group will have access to the monument. One group may set its statue of the Virgin Mary on the Vatican Monument, the other must use a nearby traffic island. The rival groups have decided it is in everyone’s interests to appear professional while in the park.

pilgrimages to Flushing Meadows with followers from around the world. But in 1997, a schism occurred between the shrine’s director, Michael Mangan, and Lueken’s widower, Arthur Lueken. A judge ruled in favor of Arthur Lueken, declaring him president of Our Lady of the Roses Shrine (OLR) and awarding him all of the organization’s assets and facilities. Undaunted, Mangan formed his own group, Saint Michael’s World Apostolate (SMWA). Both groups continued to arrive at the movement’s sacred site in Flushing Meadows where they held rival vigils. Once again, police were sent out to keep the peace (Kilgannon 2003). Today, this conflict has thawed into a detente. Their celebrations of Catholic feast days are sometimes timed such that only one group will be present in the park on a given day. For events where both groups must be present, such as Sunday morning holy hour, they alternate which group will have access to the monument. One group may set its statue of the Virgin Mary on the Vatican Monument, the other must use a nearby traffic island. The rival groups have decided it is in everyone’s interests to appear professional while in the park. have been a trope in Marian apparitions since the nineteenth century. Lueken’s visions repeatedly described a fiery celestial object called “The Ball of Redemption” (possibly a comet, although this is not clear), that will collide with the Earth, killing much of the population. Her visions also describe World War III, which will include a full nuclear exchange. Horrifying descriptions of nuclear war have also been common in Marian Apparitions since the start of the Cold War. Unlike Protestant dispensationalism, Baysiders believe that the Chastisement can be postponed through prayer. When prophecies do not come to pass, Baysiders often take credit for earning the world a reprieve from judgment.

have been a trope in Marian apparitions since the nineteenth century. Lueken’s visions repeatedly described a fiery celestial object called “The Ball of Redemption” (possibly a comet, although this is not clear), that will collide with the Earth, killing much of the population. Her visions also describe World War III, which will include a full nuclear exchange. Horrifying descriptions of nuclear war have also been common in Marian Apparitions since the start of the Cold War. Unlike Protestant dispensationalism, Baysiders believe that the Chastisement can be postponed through prayer. When prophecies do not come to pass, Baysiders often take credit for earning the world a reprieve from judgment. Hour” every Sunday that is dedicated to prayer for the priesthood. These events are held around a monument built in Flushing Meadows Park as part of the Vatican Pavilion during the 1964 World’s Fair. The monument, known as The Excedra, is a simple curved bench resembling an unrolling scroll. During vigils, the monument is transformed into a shrine. A fiberglass statue of Mary is ensconced on top of the bench and surrounded with by candles, flags representing the United States and the Vatican, and other ritual objects. The grounds are also consecrated with holy water.

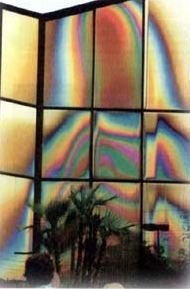

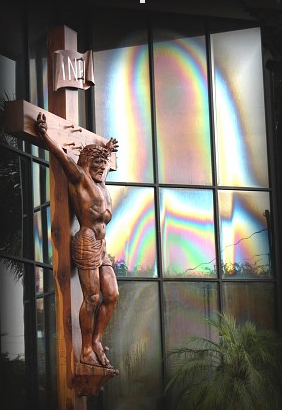

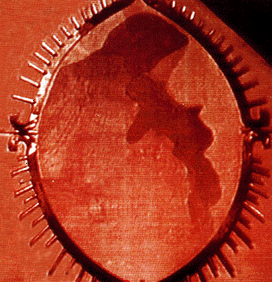

Hour” every Sunday that is dedicated to prayer for the priesthood. These events are held around a monument built in Flushing Meadows Park as part of the Vatican Pavilion during the 1964 World’s Fair. The monument, known as The Excedra, is a simple curved bench resembling an unrolling scroll. During vigils, the monument is transformed into a shrine. A fiberglass statue of Mary is ensconced on top of the bench and surrounded with by candles, flags representing the United States and the Vatican, and other ritual objects. The grounds are also consecrated with holy water. movement coincided with the development of Polaroid cameras. Many pilgrims took Polaroids during the vigils and found anomalies in the film. Most of these effects are easily attributable to user error or to ambient light sources like candles or car lights. Some, however, are more spectacular and difficult to explain. These anomalies were regarded as messages from heaven (Wojcik 1996, 2009). While Lueken was alive, people could bring her their “miraculous Polaroids” and she would interpret the streaks and blurs that appeared on the film, finding their symbolic significance (Chute and Simpson 1976). Today, ordinary Baysiders have developed codes to interpret the anomalies. During vigils, pilgrims take many photos and continue to find anomalies. While digital cameras are used, some Pilgrims prefer to use vintage Polaroid cameras like those used during the original vigils. Discovering a “message from heaven” in a photograph can be a source of great personal meaning for some Baysiders.

movement coincided with the development of Polaroid cameras. Many pilgrims took Polaroids during the vigils and found anomalies in the film. Most of these effects are easily attributable to user error or to ambient light sources like candles or car lights. Some, however, are more spectacular and difficult to explain. These anomalies were regarded as messages from heaven (Wojcik 1996, 2009). While Lueken was alive, people could bring her their “miraculous Polaroids” and she would interpret the streaks and blurs that appeared on the film, finding their symbolic significance (Chute and Simpson 1976). Today, ordinary Baysiders have developed codes to interpret the anomalies. During vigils, pilgrims take many photos and continue to find anomalies. While digital cameras are used, some Pilgrims prefer to use vintage Polaroid cameras like those used during the original vigils. Discovering a “message from heaven” in a photograph can be a source of great personal meaning for some Baysiders. Park. Saint Michael’s World Apostolate is the larger group, which is led by Michael Mangan. Although a court awarded the name “Our Lady of the Roses Shrine” to Veronica Lueken’s widower, Mangan’s group had more support from pilgrims and acquired more infrastructure. When Our Lady of the Roses Shrine was unable to maintain their printing presses, Mangan’s group arranged to buy them. Saint Michael’s World Apostolate is headed by a group of men called the Lay Order of Saint Michael, who live together in a religious community. They are supported by numerous shrine workers who help to raise funds, disseminate the messages, and organize vigils.

Park. Saint Michael’s World Apostolate is the larger group, which is led by Michael Mangan. Although a court awarded the name “Our Lady of the Roses Shrine” to Veronica Lueken’s widower, Mangan’s group had more support from pilgrims and acquired more infrastructure. When Our Lady of the Roses Shrine was unable to maintain their printing presses, Mangan’s group arranged to buy them. Saint Michael’s World Apostolate is headed by a group of men called the Lay Order of Saint Michael, who live together in a religious community. They are supported by numerous shrine workers who help to raise funds, disseminate the messages, and organize vigils.

reported Mary’s request for the distribution of not only “Mary’s Message,” but also several other books published by the Shepherds of Christ Ministries, including God’s Blue Book and Rosaries from the Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Further, many of the messages conveyed God’s wrath with human sinfulness and the failure to listen to previous messages, threatening humanity with fire, even citing religious negligence and divine wrath as the source of contemporary wildfires across Florida. There have also been prophecies of an imminent Endtime. All of Ring’s messages have been discerned by Father Carter.

reported Mary’s request for the distribution of not only “Mary’s Message,” but also several other books published by the Shepherds of Christ Ministries, including God’s Blue Book and Rosaries from the Hearts of Jesus and Mary. Further, many of the messages conveyed God’s wrath with human sinfulness and the failure to listen to previous messages, threatening humanity with fire, even citing religious negligence and divine wrath as the source of contemporary wildfires across Florida. There have also been prophecies of an imminent Endtime. All of Ring’s messages have been discerned by Father Carter. leave offerings to the Virgin, such as “candles, flowers, fruit, [and] beads, and participate in individual acts of piety (Posner 1997:2). Mary’s requests for pilgrims, as reported by Ring, include prayer, a daily recitation of the Ten Commandments at the site, recitation of the rosary, and an observance of the First Saturday devotion. In order to fulfill the Virgin’s requests to distribute her messages and lead others into prayer, audiotapes of “Mary’s Message” are played and rosaries, pamphlets, and brochures are provided by site staff (Swatos 2002:192). The focus on individual worship, rather than “the communal sense of the Mass,” is one of the primary factors setting the Clearwater group’s organization apart from traditional Catholic configuration (Swatos 2002).

leave offerings to the Virgin, such as “candles, flowers, fruit, [and] beads, and participate in individual acts of piety (Posner 1997:2). Mary’s requests for pilgrims, as reported by Ring, include prayer, a daily recitation of the Ten Commandments at the site, recitation of the rosary, and an observance of the First Saturday devotion. In order to fulfill the Virgin’s requests to distribute her messages and lead others into prayer, audiotapes of “Mary’s Message” are played and rosaries, pamphlets, and brochures are provided by site staff (Swatos 2002:192). The focus on individual worship, rather than “the communal sense of the Mass,” is one of the primary factors setting the Clearwater group’s organization apart from traditional Catholic configuration (Swatos 2002). the Shepherds of Christ Ministry. She reportedly began receiving “private revelations” from Jesus and Mary in 1991, several years prior to reporting messages associated with the image at Our Lady of Clearwater. More is known about Father Edward Carter. He was brought up I Cincinnati, attended Xavier University, was ordained in the Jesuit Order when he was 33 years-old, and taught theology at Xavier University for nearly three decades. Carter reports having begun receiving messages from Jesus during the summer, 1993, and on the day before Easter in 1994 was told that he would now begin to receive messages for others (Carter 2010). He founded the Shepherds of Christ Ministry in 1994 after the Batavia Vissionary was instructed to include him with the other priests who were to receive messages through her and to carry out the special mission of establishing the Shepherds of Christ. Carter also received a message from Jesus in which he was told to undertake this mission and to include Rita Ring: ” I am requesting that a new prayer movement be started under the direction of Shepherds of Christ Ministries…. I will use this new prayer movement within My Shepherds of Christ Ministries in a powerful way to help in the renewal of My Church and the world. I will give great graces to those who join this movement…. I am inviting My beloved Rita Ring to be coordinator for this activity” (“About” 2006).

the Shepherds of Christ Ministry. She reportedly began receiving “private revelations” from Jesus and Mary in 1991, several years prior to reporting messages associated with the image at Our Lady of Clearwater. More is known about Father Edward Carter. He was brought up I Cincinnati, attended Xavier University, was ordained in the Jesuit Order when he was 33 years-old, and taught theology at Xavier University for nearly three decades. Carter reports having begun receiving messages from Jesus during the summer, 1993, and on the day before Easter in 1994 was told that he would now begin to receive messages for others (Carter 2010). He founded the Shepherds of Christ Ministry in 1994 after the Batavia Vissionary was instructed to include him with the other priests who were to receive messages through her and to carry out the special mission of establishing the Shepherds of Christ. Carter also received a message from Jesus in which he was told to undertake this mission and to include Rita Ring: ” I am requesting that a new prayer movement be started under the direction of Shepherds of Christ Ministries…. I will use this new prayer movement within My Shepherds of Christ Ministries in a powerful way to help in the renewal of My Church and the world. I will give great graces to those who join this movement…. I am inviting My beloved Rita Ring to be coordinator for this activity” (“About” 2006). validated (“discerned) her messages. For a time she received messages daily that were made available in the Message Room along with video tapes. Ring visited what became the ” Mary Image Building” on the fifth of each month. Beginning in 2000, the year of Jubilee, the image has appeared to turn completely gold on that day.

validated (“discerned) her messages. For a time she received messages daily that were made available in the Message Room along with video tapes. Ring visited what became the ” Mary Image Building” on the fifth of each month. Beginning in 2000, the year of Jubilee, the image has appeared to turn completely gold on that day.

of Christ Ministries presents itself as a lay Catholic organization but has no formal relationship to the church. Site representatives have taken care not to challenge Roman Catholic Church authority. For example, the group indicated that it would seek permission from the local diocese before constructing a chapel at the site. Father Carter has repeatedly stated that “I recognize and accept that the final authority regarding private revelations rests with the Holy See of Rome, to whose judgment I willingly submit” (“News” n.d.). The Catholic diocese of St. Petersburg has disavowed any connection to Shepherds of Christ and has called the image a “naturally explained phenomenon.” However, the diocese has not launched an investigation of the site and has not condemned it (“Clearwater Madonna Changes Hands” 1998; Tisch 2004:4). There have other criticisms from within the Catholic community that conclude the apparitions are not authentic (Conte 2006).

of Christ Ministries presents itself as a lay Catholic organization but has no formal relationship to the church. Site representatives have taken care not to challenge Roman Catholic Church authority. For example, the group indicated that it would seek permission from the local diocese before constructing a chapel at the site. Father Carter has repeatedly stated that “I recognize and accept that the final authority regarding private revelations rests with the Holy See of Rome, to whose judgment I willingly submit” (“News” n.d.). The Catholic diocese of St. Petersburg has disavowed any connection to Shepherds of Christ and has called the image a “naturally explained phenomenon.” However, the diocese has not launched an investigation of the site and has not condemned it (“Clearwater Madonna Changes Hands” 1998; Tisch 2004:4). There have other criticisms from within the Catholic community that conclude the apparitions are not authentic (Conte 2006). St. Maria Goretti Catholic Church. There, several young people as well as Father Jack Spaulding reported apparitions or locutions of Jesus and of Our Lady, appearing as Our Lady of Joy. These messages from Jesus have been published in six volumes of I Am Your Jesus of Mercy. In 1989, the diocese of Phoenix investigated the Scottsdale apparitions and took a neutral position on the matter.

St. Maria Goretti Catholic Church. There, several young people as well as Father Jack Spaulding reported apparitions or locutions of Jesus and of Our Lady, appearing as Our Lady of Joy. These messages from Jesus have been published in six volumes of I Am Your Jesus of Mercy. In 1989, the diocese of Phoenix investigated the Scottsdale apparitions and took a neutral position on the matter. Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Now run by Mt. St. Mary’s University, the site centers upon a replica of the 1858 apparition site in Lourdes, France, and also features a Glass Chapel and visitor’s center. A walkway winds through Stations of the Cross and a Rosary Walk, ending at the foot of a large metal Crucifix atop a wooded hill. This is where Gianna received her first apparition in Emmitsburg. Our Lady, clothed in a blue dress and white veil, invited Gianna and Michael to move to the small town, if they were willing. They were given three days to make the decision, and returned home to Arizona to consider the invitation.

Grotto of Our Lady of Lourdes. Now run by Mt. St. Mary’s University, the site centers upon a replica of the 1858 apparition site in Lourdes, France, and also features a Glass Chapel and visitor’s center. A walkway winds through Stations of the Cross and a Rosary Walk, ending at the foot of a large metal Crucifix atop a wooded hill. This is where Gianna received her first apparition in Emmitsburg. Our Lady, clothed in a blue dress and white veil, invited Gianna and Michael to move to the small town, if they were willing. They were given three days to make the decision, and returned home to Arizona to consider the invitation. Group at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Emmitsburg. Gianna received a vision at her first prayer meeting, surprising fellow devotees when she fell to her knees and began conversing with Our Lady. Father Alfred Pehrsson, C.M., the parish pastor she had met during her January visit to Emmitsburg, explained to parishioners what had happened and implored them to keep quiet about what they had seen so as not to call undue attention to Gianna or the prayer group. Nevertheless, attendance at the Thursday Marian Prayer Group grew as news of the visionary spread. As many as 1,000 visitors attended weekly (Gaul 2002), including several priests, bishops from other countries, and even non-Catholic visitors. Close to 700,000 people attended between 1994 and 2008 (G. Sullivan 2008). Church groups throughout the region organized bus trips to Emmitsburg, and many families drove several hours to spend the day visiting the town. The numbers of conversions and confessions increased, and Fr. Pehrsson even heard confessions from Jewish and Protestant attendees (Pehrsson n.d.). Many attendees reported miracles during the service: a spinning sun or two suns, healings, and once, the lights of heaven visible in Gianna’s eyes during ecstasy. Every week, several rows of pews were reserved at the church for parishioners, but others had to arrive before noon (for the 7 PM service) in order to find a seat. Overflow crowds were directed to the church rectory across the street, where a television screen was set up so that all could see Gianna. Problematically, crowds set up blankets and chairs on the lawn and cemetery surrounding the church, and parked illegally throughout the small town. In response, some Protestant churches in the area opened their parking lots to pilgrims.

Group at St. Joseph Catholic Church in Emmitsburg. Gianna received a vision at her first prayer meeting, surprising fellow devotees when she fell to her knees and began conversing with Our Lady. Father Alfred Pehrsson, C.M., the parish pastor she had met during her January visit to Emmitsburg, explained to parishioners what had happened and implored them to keep quiet about what they had seen so as not to call undue attention to Gianna or the prayer group. Nevertheless, attendance at the Thursday Marian Prayer Group grew as news of the visionary spread. As many as 1,000 visitors attended weekly (Gaul 2002), including several priests, bishops from other countries, and even non-Catholic visitors. Close to 700,000 people attended between 1994 and 2008 (G. Sullivan 2008). Church groups throughout the region organized bus trips to Emmitsburg, and many families drove several hours to spend the day visiting the town. The numbers of conversions and confessions increased, and Fr. Pehrsson even heard confessions from Jewish and Protestant attendees (Pehrsson n.d.). Many attendees reported miracles during the service: a spinning sun or two suns, healings, and once, the lights of heaven visible in Gianna’s eyes during ecstasy. Every week, several rows of pews were reserved at the church for parishioners, but others had to arrive before noon (for the 7 PM service) in order to find a seat. Overflow crowds were directed to the church rectory across the street, where a television screen was set up so that all could see Gianna. Problematically, crowds set up blankets and chairs on the lawn and cemetery surrounding the church, and parked illegally throughout the small town. In response, some Protestant churches in the area opened their parking lots to pilgrims. Commission was unfair to Gianna, spending very little time with her and prohibiting her supporters (including theologians) from speaking on her behalf. Gianna was permitted to answer only the questions posed to her by the Commission, rather than tell her whole story.

Commission was unfair to Gianna, spending very little time with her and prohibiting her supporters (including theologians) from speaking on her behalf. Gianna was permitted to answer only the questions posed to her by the Commission, rather than tell her whole story. Cult Watch , took a negative view of the apparitions, supporters, and visionary. Father Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., Gianna’s spiritual advisor, was silenced when Cardinal Keeler ordered Fr. Kavanaugh’s superior to temporarily restrict the priest from attending the monthly prayer meetings. Father Alfred Pehrsson, the parish priest at St. Joseph who had since been relocated to another parish, was also asked by his superiors not to speak about the Emmitsburg apparitions. Both men have remained reticent to speak about the Emmitsburg events.

Cult Watch , took a negative view of the apparitions, supporters, and visionary. Father Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D., Gianna’s spiritual advisor, was silenced when Cardinal Keeler ordered Fr. Kavanaugh’s superior to temporarily restrict the priest from attending the monthly prayer meetings. Father Alfred Pehrsson, the parish priest at St. Joseph who had since been relocated to another parish, was also asked by his superiors not to speak about the Emmitsburg apparitions. Both men have remained reticent to speak about the Emmitsburg events. leadership, Gianna wrote a letter to Archbishop O’Brien informing him of the history of the apparitions in Emmitsburg and assuring him that she would comply with his wishes regarding the monthly prayer meetings held at Lynfield. Archbishop O’Brien did not respond to Gianna’s letter directly, but instead released a Pastoral Advisory in 2008 repeating the Church’s position that the messages were not supernatural. While he admitted in the Pastoral Advisory that there is nothing necessarily sacrilegious about the messages, he asserted his view that the “alleged apparitions are not supernatural in origin” (O’Brien 2008). He further “strongly” cautioned Mrs. Gianna Talone-Sullivan not to communicate in any manner whatsoever, written or spoken, electronic or printed, personally or through another in any church, public oratory, chapel or any other place or locale, public or private, within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Baltimore any information of any type related to or containing messages or locutions allegedly received from the Virgin Mother of God.

leadership, Gianna wrote a letter to Archbishop O’Brien informing him of the history of the apparitions in Emmitsburg and assuring him that she would comply with his wishes regarding the monthly prayer meetings held at Lynfield. Archbishop O’Brien did not respond to Gianna’s letter directly, but instead released a Pastoral Advisory in 2008 repeating the Church’s position that the messages were not supernatural. While he admitted in the Pastoral Advisory that there is nothing necessarily sacrilegious about the messages, he asserted his view that the “alleged apparitions are not supernatural in origin” (O’Brien 2008). He further “strongly” cautioned Mrs. Gianna Talone-Sullivan not to communicate in any manner whatsoever, written or spoken, electronic or printed, personally or through another in any church, public oratory, chapel or any other place or locale, public or private, within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Baltimore any information of any type related to or containing messages or locutions allegedly received from the Virgin Mother of God. many messages assuring them that she is not leaving Emmitsburg. The February 5, 2006 message, for instance, assures listeners that Emmitsburg is the Center of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart despite opposition from some Church leaders, then continues, “Know that I am not leaving and that I intercede for all good things for you before the Throne of God.” The October 5, 2008 message (just before the Pastoral Advisory was released) repeats this theme: “know that I am here with you. I am not leaving , even if you think I am far away.”

many messages assuring them that she is not leaving Emmitsburg. The February 5, 2006 message, for instance, assures listeners that Emmitsburg is the Center of Our Lady’s Immaculate Heart despite opposition from some Church leaders, then continues, “Know that I am not leaving and that I intercede for all good things for you before the Throne of God.” The October 5, 2008 message (just before the Pastoral Advisory was released) repeats this theme: “know that I am here with you. I am not leaving , even if you think I am far away.” Revelations 12:1 is another helpful source of historical information. Both organizations maintain websites easily accessible by any internet search engine, the Foundation of the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary and Private Revelations of Our Lady of Emmitsburg . Both organizations officially are located in Pennsylvania and are thus outside the jurisdiction of the Baltimore Archdiocese and its prohibitions. Notably, Gianna disavowed any involvement with The Foundation in her 2008 response to the Pastoral Advisory.

Revelations 12:1 is another helpful source of historical information. Both organizations maintain websites easily accessible by any internet search engine, the Foundation of the Sorrowful and Immaculate Heart of Mary and Private Revelations of Our Lady of Emmitsburg . Both organizations officially are located in Pennsylvania and are thus outside the jurisdiction of the Baltimore Archdiocese and its prohibitions. Notably, Gianna disavowed any involvement with The Foundation in her 2008 response to the Pastoral Advisory. In August 1994, an image of the Virgin Mary, holding the baby Jesus, seemed to appear through plasterwork on a wall at the front of the church to the right of the altar. A parishioner first noticed the image and eventually commented on it to the rector at that time, Father Andrew Notere (originally Nutter), a native of Canada whose father was an Anglican archbishop (Lloyd 1996a:3). There was a waiting period to see if the image remained, and when it did, it was discussed at a church council. The Australian media took up an article that had been prepared for the local diocesan paper by Father Notere (Morgan 2007:32).

In August 1994, an image of the Virgin Mary, holding the baby Jesus, seemed to appear through plasterwork on a wall at the front of the church to the right of the altar. A parishioner first noticed the image and eventually commented on it to the rector at that time, Father Andrew Notere (originally Nutter), a native of Canada whose father was an Anglican archbishop (Lloyd 1996a:3). There was a waiting period to see if the image remained, and when it did, it was discussed at a church council. The Australian media took up an article that had been prepared for the local diocesan paper by Father Notere (Morgan 2007:32). third person, possibly Mary Magdalene or Mary MacKillop was emerging” (Pengelley 1996:3). Saint Mary MacKillop [1842-1909], the first Australian saint [cannonised 2010], was a member of the Josephite order that established a school at Yankalilla.

third person, possibly Mary Magdalene or Mary MacKillop was emerging” (Pengelley 1996:3). Saint Mary MacKillop [1842-1909], the first Australian saint [cannonised 2010], was a member of the Josephite order that established a school at Yankalilla. continued to the present day. Many common Marian pilgrimage motifs are present such as miraculous events, healing and messages. This traditional, high Anglican church has accepted the image in its Church despite the general “Protestant view [which] tends to limit the communion of saints to the living and does not look favourably on the possibility of supernatural intervention by deceased saints” (Turner and Turner 1982:145). At the Shrine of Our Lady of Yankalilla visitors have the chance to observe, and to have experiences, that they do not have in their home parishes. Interestingly, the initial rituals at the shrine were drawn from Charismatic, Catholic, Anglican and Buddhist practices (Jones 1998). These rather New Age practices could attract visitors who may not necessarily be drawn to an Anglican church (Cusack 2003:119). McPhillips considers such a mix “in effect releases Mary into new realms of enchantment” (McPhillips 2006:149). It did however cause conflict at a parish level (Jones 1998).

continued to the present day. Many common Marian pilgrimage motifs are present such as miraculous events, healing and messages. This traditional, high Anglican church has accepted the image in its Church despite the general “Protestant view [which] tends to limit the communion of saints to the living and does not look favourably on the possibility of supernatural intervention by deceased saints” (Turner and Turner 1982:145). At the Shrine of Our Lady of Yankalilla visitors have the chance to observe, and to have experiences, that they do not have in their home parishes. Interestingly, the initial rituals at the shrine were drawn from Charismatic, Catholic, Anglican and Buddhist practices (Jones 1998). These rather New Age practices could attract visitors who may not necessarily be drawn to an Anglican church (Cusack 2003:119). McPhillips considers such a mix “in effect releases Mary into new realms of enchantment” (McPhillips 2006:149). It did however cause conflict at a parish level (Jones 1998). visitors originating from India, most notably from Kerala and Goa, while others are from the South Australian Indian community (Gardiner 2015). The visitors’ book indicates pilgrims are local, interstate as well as from Europe, South America and Asia. These visits may just be curiosity; however, “a tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist” (Turner 1978;20)

visitors originating from India, most notably from Kerala and Goa, while others are from the South Australian Indian community (Gardiner 2015). The visitors’ book indicates pilgrims are local, interstate as well as from Europe, South America and Asia. These visits may just be curiosity; however, “a tourist is half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist” (Turner 1978;20) international shrine” (Smart 1996:6 Innes 1996:4). This blessing would appear to indicate that at the time of the emergence of the image there was official Anglican support and acceptance. It is important for miraculous events to fall within the boundaries of the traditional religion with which it is associated. T he Virgin Mary can be found in Anglican shrines, such as at Walsingham [United Kingdom], a site visited by many pilgrims each year, and Christ Church Yankalilla is high Anglican, which accepts veneration of the Virgin Mary (Kahl 1998:257). To link these shrines, an icon dedicated to Walsingham hangs on the Church wall. Such an icon, a pieta (a statue depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus) image, may assist visitors in seeing the apparent image on the wall (Morgan 2007:31).

international shrine” (Smart 1996:6 Innes 1996:4). This blessing would appear to indicate that at the time of the emergence of the image there was official Anglican support and acceptance. It is important for miraculous events to fall within the boundaries of the traditional religion with which it is associated. T he Virgin Mary can be found in Anglican shrines, such as at Walsingham [United Kingdom], a site visited by many pilgrims each year, and Christ Church Yankalilla is high Anglican, which accepts veneration of the Virgin Mary (Kahl 1998:257). To link these shrines, an icon dedicated to Walsingham hangs on the Church wall. Such an icon, a pieta (a statue depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus) image, may assist visitors in seeing the apparent image on the wall (Morgan 2007:31). was formed but since disbanded. The aims of the community were to work with pilgrims and foster a healing spirit at the shrine (Kahl 1998:50). A Retreat Centre next to the church was established in 2000, but the space is now utilized for general parish purposes (Morgan 2007:33). A Maori group of singers was reportedly considering moving to the area, drawn by the image. The group joined a local choir to make a CD dedicated to the Virgin Mary appearing at Yankalilla (“Choirs Combine” 2002:14).

was formed but since disbanded. The aims of the community were to work with pilgrims and foster a healing spirit at the shrine (Kahl 1998:50). A Retreat Centre next to the church was established in 2000, but the space is now utilized for general parish purposes (Morgan 2007:33). A Maori group of singers was reportedly considering moving to the area, drawn by the image. The group joined a local choir to make a CD dedicated to the Virgin Mary appearing at Yankalilla (“Choirs Combine” 2002:14). Later, many would look upon him as the seer par excellence, while others would consider him a fake or something in between. After failing to enter priest seminary, he became an office clerk. He worked for a Catholic company in Seville for a time but subsequently was fired. Clemente was not one of the pioneer seers, but beginning in the summer of 1969, and on an almost daily basis, he went to Palmar de Troya together with his friend, the lawyer Manuel Alonso Corral (1934-2011).

Later, many would look upon him as the seer par excellence, while others would consider him a fake or something in between. After failing to enter priest seminary, he became an office clerk. He worked for a Catholic company in Seville for a time but subsequently was fired. Clemente was not one of the pioneer seers, but beginning in the summer of 1969, and on an almost daily basis, he went to Palmar de Troya together with his friend, the lawyer Manuel Alonso Corral (1934-2011). Alonso, written down, copied and distributed. Some of them were translated into English, French and German as part of the diffusion of the news beyond Spain’s borders. To be able to make mission journeys and institutionalize the movement, funding was needed. According to testimonies, Manuel Alonso was a very good fund-raiser who convinced some very wealthy people to contribute large sums. The capital influx meant that Clemente and Manuel could travel widely on both sides of the Atlantic. Beginning in 1971, they went through Western Europe, to the United States and to various countries in Latin America to win people for the Palmarian cause.

Alonso, written down, copied and distributed. Some of them were translated into English, French and German as part of the diffusion of the news beyond Spain’s borders. To be able to make mission journeys and institutionalize the movement, funding was needed. According to testimonies, Manuel Alonso was a very good fund-raiser who convinced some very wealthy people to contribute large sums. The capital influx meant that Clemente and Manuel could travel widely on both sides of the Atlantic. Beginning in 1971, they went through Western Europe, to the United States and to various countries in Latin America to win people for the Palmarian cause. a steady stream of pilgrims kept coming to Palmar de Troya. It was reported that as many as 40,000 people were present on May 15, 1970. Three days after this all-time-high, Bueno published a document, where he briefly commented on the events. He did not mince matters when stating that they were signs of “collective and superstitious hysteria.” The gist of the archbishop Bueno’s statement on Palmar de Troya was reiterated in 1972. In a decree, he explicitly forbade all kinds of public worship at the Alcaparrosa field, ordering Roman Catholic priests not to be present, let alone celebrate any religious services there.

a steady stream of pilgrims kept coming to Palmar de Troya. It was reported that as many as 40,000 people were present on May 15, 1970. Three days after this all-time-high, Bueno published a document, where he briefly commented on the events. He did not mince matters when stating that they were signs of “collective and superstitious hysteria.” The gist of the archbishop Bueno’s statement on Palmar de Troya was reiterated in 1972. In a decree, he explicitly forbade all kinds of public worship at the Alcaparrosa field, ordering Roman Catholic priests not to be present, let alone celebrate any religious services there. bishop in 1938 and became archbishop of Hue in 1960. While living in Europe, he was replaced in Hue and instead made titular archbishop of Bulla Regia. However, he actually served as an assistant pastor in a small Italian town, upset and bewildered by the changes in the post-conciliar church. Archbishop Thuc came to Palmar de Troya through the mediation of Maurice Revaz, who taught canon law at the traditionalist Society of Pius X’s seminary in Ecône. Revaz convinced Thuc that he was elected by the Virgin to save the Catholic Church from perdition. With short notice, the Vietnamese prelate therefore travelled to Seville and Palmar de Troya. On New Year’s night in 1976, he ordained Clemente Dominguez, Manuel Alonso, and two other men to the priesthood. The priestly ordinations, however, were just the prelude. Less than two weeks later, on January 11, 1976, Thuc consecrated five of the Palmarians, once again including Clemente and Manuel. With the episcopal consecrations, the Palmarians had secured their much sought-after apostolic succession and could start making bishops of their own.