BEDWARDISM TIMELINE

1889 (April 19): The Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church set up August Town, Jamaica, by H.E.S. Woods (also known as “Shakespeare”).

1859: Alexander Bedward was born in St Andrew, Jamaica.

1883: Bedward migrated to Colón, Panama.

1885 (August 10): Bedward returned to Jamaica after a series of visions.

1891 (October 10): Bedward began his public ministry.

1891 (December 22): Bedward performed his first Hope River healing ceremony.

1895 (January 21): Bedward was arrested for making seditious statements.

1895 (May 2): Bedward’s was tried and subsequently incarcerated in the Kingston lunatic asylum.

1895 (May 28): Bedward was released from the asylum.

1920 (December 31): People flocked from all over Jamaica to Kingston to witness Bedward’s attempted ascension into Heaven.

1921 (April 27): Bedward lead his followers on a march from August Town into central Kingston.

1921 (May 4): Bedward’s trial resulted in his incarceration in Kingston lunatic asylum.

1930 (November 8): Bedward’s died in the asylum.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Bedwardism, or the Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church, had its origins in a church founded in 1889 by H.E.S. Woods, also known as “Shakespeare.” Shakespeare was an American who came to live in Jamaica, initially in Spanish Town then moving to St David’s c.1876. There he would preach and make prophesies. In June 1879, Shakespeare visited Dallas Castle, St Andrew, and prophesised that it would be severely damaged by a flood. On October 11 a flood came, destroying the Wesleyan Chapel amongst other buildings, and claiming “several lives” (Brooks 1917:3).

Nine years later, Shakespeare visited August Town and “threatened he would destroy it like he had Dallas Castle unless people repented.” On April 19. 1889, he called a meeting of the town’s three main denominations: Anglicans, Baptists and Wesleyans. After the meeting, Shakespeare appointed twelve men and twelve women as elders of the church. Each appointee had to put their hand upon a Bible, which was balanced on top of a jar of Mona River water, and vow to serve God until death. Shakespeare then placed two elders in charge of the August Town mission and returned to Spanish Town (Brooks 1917:3-4).

A.A. Brooks, a Bedwardite who wrote a tract, History of Bedwardism or The Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church, described Shakespeare as being remarkably robust even into old age, despite sometimes fasting for weeks, “tasting neither food not water” (Brooks 1917:5). Shakespeare died in August Town in 1901 at age 101.

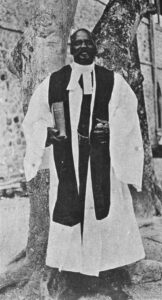

At the founding meeting of his church, Shakespeare had prophesised that “‘There is one among you who shall succeed me, and be the leader of a great Religious movement, which shall be centered in Augustown (sic)…’” (Brooks 1917:4). His successor was to be found in the person of Alexander Bedward. [Image at right]

Alexander Bedward was born in St Andrew, Jamaica, c.1859. He worked as a labourer on the Mona estate, but after suffering persistent ill health for a number of years, he migrated to Panama in 1883 in the hope that a change of climate would alleviate his symptoms. After staying in Colón for two years in good health, Bedward returned to Jamaica where his health issues immediately reappeared. He went back again to Panama but remained ill. On the sixth night in Colón, Bedward had a vision of a man who told him to go back to Jamaica if he wanted to save his soul and the souls of others. If Bedward stayed in Panama, he would die and lose his soul. Bedward said he had no money for his fare back to Jamaica (Brooks 1917:7).

After this vision, Bedward fell asleep and dreamt he was back in Jamaica. In the dream he was walking up the Constant Spring Road when he saw an open gate. He tried to enter but the man on the gate said he couldn’t come in as he had no passport and told him that he was lost. This upset Bedward greatly. As he continued to walk down the road, he met another man who told him to go to August Town, saying “’Go to Augustown (sic), submit yourself to Mr Raderford for instruction, with fastings on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Then be baptised: for I have special work for you to do’” (Brooks 1917:8).

Later that day while out walking, Bedward saw a man in white clothing who asked him angrily why he hadn’t got the money for the return passage to Jamaica. The man whipped Bedward who cried out in pain. However, bystanders reported that they could only see Bedward talking to thin air and wincing in agony. The dream and visions convinced Bedward that he must go back to Jamaica and fulfil the instructions given to him. He managed to get the money together for his return passage, arriving back in Jamaica on August 10, 1885. Six months later he was baptised by Mr Raderford. Bedward continued to work as a labourer on the Mona Estate until October 10, 1891 when he began his public ministry. He was joined by a Baptist gospel worker, V. Dawson, to work on the mission together, with Dawson being appointed pastor (Brooks 1917:8).

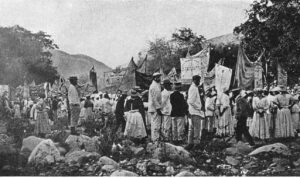

Bedward’s first healing ceremonies at the Hope River took place on December 22, 1891 after he had received a “revelation” about the healing properties of the water there. He administered water to seven people who were, according to Brooks, “immediately cured” (Brooks 1917:8). Bedward’s Hope River ceremonies began to attract very large crowds. [Image at right] In 1904, the British anthropologist and travel writer Bessie Pullen-Burry, who attended one of Bedward’s baptismal meetings, noted that “thousands… were assembled” to watch the immersion of 300 people (Pullen-Burry 1905:144).

As his ministry grew, Alexander Bedward became increasingly outspoken in his criticism of the Jamaican government and the socioracial status quo. In January 1895, Bedward was charged with attempting to cause “insurrection, riots, tumults, and breach of the peace” (Daily Gleaner January 16, 1895:3). The statements made by Bedward which led to him being detained record that the preacher likened white men to the Pharisees and Sadducees of the Bible. He also told his followers to remember the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865 where tensions over landownership in the parish of St Thomas-in-the-East and the difficulties black Jamaicans had in obtaining fair treatment in the courts culminated in a group of about 400 black people, led by a Native Baptist minister, marching from Stony Gut to the parish capital of Morant Bay to demand social justice. Rioting broke out, lasting for several days, and was only quelled after the Governor declared martial law (Heuman 1994:170).

Furthermore, Bedward declared that black Jamaicans should forcibly challenge white oppression, saying that:

There is a white wall and a black wall, and the white wall has been closing around the black wall; but now the black wall has become bigger than the white wall, and they must knock the white wall down. The white wall has oppressed us for years; now we must oppress the white wall (Post 1978:7).

Bedward was sentenced to be detained in Kingston Asylum. However, the preacher was released after his lawyer argued successfully that “you cannot try a man for sedition and sentence him to an asylum” (Daily Gleaner January 16, 1895:3).

Twenty-five years later, Alexander Bedward was still giving the colonial authorities cause for concern. In 1920, large crowds traveled to Kingston from all across Jamaica, including some who had come from Panama, after the preacher announced that he would to ascend to Heaven on December 31, 1920 and return in three days to take his followers with him (Daily Gleaner December 29, 1920; Beckwith 1923:41). After three attempts, the ascension failed and the crowds dispersed.

The American anthropologist Martha Warren Beckwith, who was doing fieldwork on African-Jamaican folk cultures, got to interview Bedward just prior to his ascension attempt. Bedward told Beckwith that he was Jesus Christ and had been crucified (Beckwith 1923:42.). He also informed her that his grievance against white people was due to the government’s consistent refusal to allow Revivalist leaders to conduct marriage ceremonies. This meant that Revivalists who wished to marry had to use the services of other churches, and Revival ministers lost out on the enhanced status being a celebrant would have conferred. Moreover, their churches missed out on the fees they would have received for performing marriages (Beckwith 1929:169).

The following year, on April 27, Bedward led nearly 700 of his followers on a march from his ministry in August Town to Kingston. He was arrested and declared insane. Fellow marchers who supported his declaration that he was ‘the Lord Jesus Christ’ were also committed to Kingston asylum for observation while the others were arrested for vagrancy. Bedward’s incarceration lasted for nine years, ending only with his death in 1930.

Despite Brooks’ assertion in a History of Bedwardism that in the future Bedwardism would succeed Christianity, just as Christianity had “succeeded” Judaism, Bedwardism never regained its radical edge after the incarceration and subsequent death of its leader (Brooks 1917:17; Burton 1997:119). When a Jamaican branch of the Holiness Church of God was founded in 1907, Pentecostalism rapidly became the main faith of working-class Jamaicans, “especially of working women” (Austin-Broos 1992:237; Burton 1997:119). Further, the growth of Rastafarianism, “which offered a more potent vehicle of protest and self-affirmation, appealed more to the radical and displaced (male) sectors of Jamaican society” (Burton 1997:119). Bedwardism, along with Revival, became more the preserve of older people and those in rural areas.

However, at its peak, Bedwardism had over 33,000 members in Jamaica, and there were branches in Panama, Costa Rica and Cuba. Today, Alexander Bedward, in his critique of the socio-racial status quo, is regarded as an influence on the black nationalism of Marcus Garvey and of the Rastafari movement. There is another link between Bedwardism and Rastafarianism. Robert Hinds, one of the founders of the Rastafari faith, had been a Bedwardite and had been arrested on the march into Kingston in 1921. Hinds’ King of Kings Mission mixed elements such as fasting from Revival alongside influences from Ethiopianism and the teachings of Marcus Garvey (Chevannes 1994:127). Furthermore, he introduced a number of his fellow Bedwardites to the incipient Rastafari movement (Gosse 2022:150).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

In the theology of Bedwardism, there was a belief in Divine Revelation, of God revealing knowledge to believers, and an acceptance of the Holy Trinity (Bryan 1991:42). Bedward used the metaphor of the constituent parts of a lighted candle: the tallow representing the Father, the wick, the Son, and the flame, the Holy Spirit (Brooks 1917:22).

The concept of three heavens arranged in a hierarchy was another of the theological beliefs of Bedwardism. At the bottom of the heavenly hierarchy is the third Heaven where those who are not baptised but die believing in God, will go. Those who are baptised will enter the second Heaven. The first Heaven is for the baptised followers of Bedward who devote themselves to the fasting, a key tenet of the faith (Brooks 1917:17-18).

The other main features of Bedward’s ministry were baptism and healing; in the case of the latter, a strong emphasis was placed on the curative powers of water from the Hope River. As the afflicted were being immersed in the river the song “Dip Dem Bedward, Dip dem in the healin’ stream” was sung by the watching crowds (Lewin 2000:33). Consecrated water from the Hope River was also bottled and sold for healing purposes.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Bedwardism is a form of Revival, itself a number of religious sects, principally Revival Zion and Pukkumina (also known as Pukumina), which grew out of a major religious revival that occurred in Britain, Ireland and the United States in the late 1850s, arriving in Jamaica in 1860. Revival sects are not dissimilar to Myal and the Native Baptists, earlier African-Jamaican religions which combined elements from Christianity with those from African spiritual belief systems, such as possession by spirits while in trance and ecstatic dancing to induce the spirits to descend.

Although Revival Zion and Pukkumina both use the Bible, hymns, Christian symbols, and have a belief in the triune Christian God, they differ in which spirits they choose to worship. In Revival Zion, Jesus, the Holy Spirit (or Dove), angels, archangels and the prophets take centre stage, whereas in Pukkumina all spirits are regarded as powerful and given respect, including Satan and the fallen angels (Chevannes 1994:20). As their respective spirit worlds may suggest, Revival Zion is closer to the Baptist Christian end of the spectrum of African-Caribbean folk religions whereas Pukkumina is the most associated with African traditions and is regarded as being closer to Obeah and early Myal (Besson 2002:243).

While teachings from the Bible and the singing of Christian hymns were a feature of Bedward’s services and Bedward himself dressed like an Episcopalian minister, syncretism with African religions is illustrated by the importance of water in a number of rituals in Bedwardism (Bryan 1991:44). Water plays a significant role in West African spiritual beliefs as well as Christian, and in Bedwardism; its importance can be seen in its use in baptism, healing and the washing away of sin (Moore and Johnson 2004:70).

To become a member of Bedward’s church, a person would first have to take part in the Vow ceremony. Candidates were brought before the altar where each received a candle then repeated a prayer led by the minister. The hymn “Before Jehovah’s Awful Throne” was sung to end the service (Brooks 1917:22).

After the Vow ceremony, candidates could then be baptised. Baptism ceremonies took place in the early morning so that those attending could “greet the rising sun” (Chevannes 1994:80). Candidates, wearing white robes, were baptised by full immersion in the Hope River, with women going first. A hymn was sung at each immersion. Afterwards, the newly baptised would be led by Bedward’s assistants to shelters to change from their wet robes before heading back to church for a service (Pullen-Burry 1905:146).

While baptism ceremonies were performed quarterly, Holy Communion was held at August Town on the second Sunday of each month. Members from nearby affiliated camps would also attend, while those who lived in remote locations would receive communion when the pastor visited their area (Brooks 1917:14).

The important ritual of fasting took place every Monday, Wednesday and Friday from midnight until 1 PM the following day. Fast days began with a service at noon. Members, clad in white, sat at long tables covered in white cloths. Water from the Hope River was placed alongside bread at the head of each table to be consumed after hymns and prayers. The meeting closed with a benediction from the New Testament (Brooks 1917:20-21).

ORGANISATION/LEADERSHIP

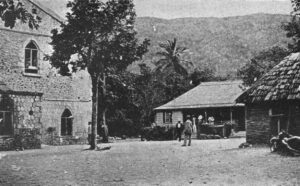

While the centre of Bedwardism was based at Bedward’s church in August Town, [Image at right] there were a number of subsidiary groups, or Camps throughout Jamaica. Each Camp had its own set of leaders and “functioned autonomously” of the main church, although they observed the same services and tri-weekly fasts as in August Town and made visits to the parent church (Chevannes 1994:80).

A.A. Brooks described the structure of leadership at the August Town church as consisting of the Shepherd (Alexander Bedward), at the top followed by the Pastor, V. Dawson, then “twenty-four Elders, and seventy-two Evangelists of both sexes as well as Station-guards and Mothers” (Brooks 1917:13).

The hierarchy and titles of officers are similar in modern Revival with the most common titles of office being firstly the leader, (a “Daddy or “Father”), followed by a Deacon or Deaconess who assist, a “Mother,” Armour Bearers (officers who read the Bible and assist at meetings) Elders, Bandsmen and then the followers (Simpson 1956:403). All the male roles have female counterparts with “Mother” being the highest women’s office. At the bottom are the followers of which women make up a large number (Simpson 1980:196).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

One of the main issues faced by Bedwardism was disapproval by the ruling classes in Jamaica of African-Jamaican religions and spiritual beliefs. The era of Bedward’s ministry, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was a time when the British and Jamaican governments wanted to turn Jamaicans away from African-derived beliefs and cultural practices. In part this was because the British government wanted to create a unified empire sharing a common culture based on British middle-class values and ideas. It held the position that in order to compete with larger countries on the world stage, Britain needed to expand and expansion could be achieved by “drawing its colonies into a closer, more personal relationship” (Thompson 2000:25).

However another factor behind the imposition of this form of cultural hegemony was the idea that it would “civilise” the island, helping to maintain law and order and improve Jamaica’s prosperity. It was felt that showing that Jamaica was a modern, progressive and safe country would encourage investment and the expansion of the country’s burgeoning tourist industry.

As well as facing official disapproval because it did not fit in with the shared cultural values the ruling classes felt were desirable for Jamaican society, another major challenge faced by Bedwardism was that the increasingly political nature and anti-white rhetoric of some of Alexander Bedward’s statements attracted police attention. Bedward, a charismatic preacher who could draw large crowds to his gatherings, evoked memories of Jamaica’s two largest rebellions of the nineteenth century. Both the Baptist War of 1831 and Morant Bay in 1865, had been led by ministers of non-mainstream religions: Sam Sharpe, a Native Baptist “daddy” in the case of the former and Paul Bogle, a Native Baptist deacon leading the latter. Furthermore, many of Bedward’s followers came from the predominantly black, disaffected, rural peasantry and working-classes. These factors led to government surveillance of Bedward’s activities, and a police presence became common at his services and healing ceremonies. There were fears of serious civil unrest in 1920 because of the thousands who flocked to witness the preacher’s ascension into Heaven, and a large number of police were dispatched to prevent any disturbances (Satchell 2009:47-48).

Bedward was first arrested and incarcerated in 1895 for allegedly making seditious comments and then again in 1921 as a result of the march into Kingston. Bedward had applied for a permit to hold his march in a public park, but permission was denied. Despite this, he was determined the march should go ahead. In response, the island’s governor, Sir Leslie Probyn, the chief of police, and the attorney general held an emergency meeting to work out how to deal with the situation. They decided that a strong, repressive response was necessary, and joint action between the police and the military was agreed upon. On the morning of April 27, two platoons of the Sussex Regiment, armed with rifles, joined with police to arrest the marchers (Satchell 2009:50, 53).

685 of the marchers were charged under the Vagrancy Act (1902), even though few if any were actually vagrants; the majority having taken time off work to attend the march (Satchell 2009: 55). The outcome of Bedward’s arrest was, as had happened in 1895, incarceration in Kingston lunatic asylum. Nevertheless, the issue of Alexander Bedward’s mental health is a complex one, and his incarceration formed part of a pattern in the state handling of some African-Jamaican faiths whereby preachers who made outspoken comments of a political nature were vulnerable to being detained in mental institutions as a means to quell defiance (Post 1978:8).

In 1892, Bedward’s own family had tried to get him committed to an asylum because of episodes of erratic and violent behaviour. After an examination, the doctor diagnosed that the preacher was insane, but Bedward’s family could not afford to have him privately committed (Moore and Johnson 2004:82). A doctor who gave evidence at Bedward’s 1895 trial said that the preacher was suffering from amentia, a usually congenital mental problem. However, the doctor went on to say that Bedward was still aware of the difference between right and wrong (Jamaica Post May 1, 1895:3; Post 1978:12).

In an account of Bedward’s trial in 1921, Kingston’s Daily Gleaner newspaper reported that he had “proclaimed himself as Jesus Christ and a son of the Virgin Mary” and had been “commanded by God to do certain things” (Daily Gleaner May 5, 1921:1). Some months before, during the course of Martha Beckwith’s interview with Bedward, the preacher told her that he was Jesus Christ and had been crucified (Beckwith 1923:42). Bedward’s self-identification as Jesus Christ was taken as an indicator of his mental instability at his trial in 1921. However Bedward’s insistence that he should be addressed as Christ fitted in with a trait in turn-of-the-century Revivalism in which Revivalists identified themselves with Biblical figures including Jesus Christ, John the Baptist and Old Testament prophets. Such identification was linked with the ability to prophesise, an important element in Revival.

IMAGES**

Image #1: Alexander Bedward.

Image #2: Procession to the Hope River.

Image #3: Church and cottage at August Town.

** All images are from Martha Warren Beckwith. 1929. Black Roadways: A Study of Jamaican Folklife reprint, New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969 of original edition, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. Accessed from HathiTrust Digital Library: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015002677949&view=page&seq=11 on 20 May 2023.

REFERENCES

Austin-Broos, Diane J. 1992. “Redefining the Moral Order: Interpretations of Christianity in Post-emancipation Jamaica.” Pp. 221-43 in The Meaning of Freedom, Economy, Politics and Culture after Slavery,” Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Beckwith, Martha Warren. 1969 [1929]. Black Roadways: A Study of Jamaican Folklife. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Beckwith, Martha Warren. 1923. “Some Religious Cults in Jamaica.” The American Journal of Psychology 3:32-45.

Brooks, A. A. 1917. History of Bedwardism or The Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church, Second Edition. Kingston: The Gleaner Co, Ltd.

Bryan, Patrick. 2000 [1991], The Jamaican People, 1880-1902: Race, Class and Social Control reprint, Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press. London: Macmillan Caribbean.

Burton, Richard D. E. 1997. Afro-Creole: Power, Opposition and Play in the Caribbean. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

Chevannes, Barry. 1994. Rastafari: Roots and Ideology. New York: Syracuse University Press.

Daily Gleaner. Articles from 1895, 1920, 1921.

Gosse, Dave St. Aubyn. 2022. Alexander Bedward, the Prophet of August Town: Race, Religion and Colonialism. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press.

Heuman, Gad. 1994. “The Killing Time”: The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica. London: Macmillan Caribbean.

Moore, Brian L. and Michele A. Johnson. 2004. Neither Led nor Driven: Contesting British Imperialism in Jamaica, 1865-1920. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press.

Pullen-Burry, Bessie. 1905. Ethiopia in Exile: Jamaica Revisited. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Post, Ken. 1978. Arise Ye Starvelings: The Jamaican Labour Rebellion of 1938 and its Aftermath. The Hague: Nijhoff.

Satchell, Veront, 2009, “Colonial Injustice: The Crown vs the Bedwardites, Apr. 1921.” Pp. 46-67 in The African-Caribbean Worldview and the Making of Caribbean Society, edited by Horace Levy. Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago: University of the West Indies Press.

Simpson, George Eaton, 1980, Religious Cults of the Caribbean: Trinidad, Jamaica and Haiti, Third Edition, enlarged. Rio Piedras: Institute of Caribbean Studies, University of Puerto Rico.

Simpson, George Eaton 1956. “Jamaican Revivalist Cults.” Social and Economic Studies 5:i-iv, 321-445.

Thompson, Andrew S. 2000. Imperial Britain: The Empire in British Politics c.1880-1932. Harlow: Longman.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Sparkes, Hilary. 2021. “Minds Overwrought by “Religious Orgies”: Narratives of African-Jamaican Folk Religion and Mental Illness in Late Nineteenth-Century and Early Twentieth-Century Ethnographies.” Journal of Africana Religions 9:227-49.

Publication Date:

22 May 2023