SAINT ANGELA OF FOLIGNO TIMELINE

1248/1249: Angela of Foligno was born at Foligno in Umbria, a few miles from Assisi, of a possibly noble and wealthy family.

1270 (?): Angela got married. From this marriage, she might have had several sons.

1285: At age thirty seven, Angela of Foligno received a vision of St. Francis of Assisi and converted to Christianity.

1288 (?): All of Angela’s family members had died.

1291 (June 28): Angela took the habit of the Third Order of Saint Francis and became a tertiary.

1291 (early autumn): Angela met Friar Arnaldo on a pilgrimage to Assisi.

1292 (March 26): Friar Arnaldo, Angela’s scribe, suspected that Angela was captured by evil spirits; she began dictating her book, the Memorial, to him.

1296: Angela finished the Memorial.

1296 (April 3): Angela went to work in hospitals to serve lepers.

1294–1296: Angela suffered from despair.

1300 (early August): Angela went on another pilgrimage to Assisi.

1307: Angela visited the Poor Clares (nuns of the Order of St. Clare) of Spello.

1206 (?)–1309 (?): Angela’s teachings were assembled as her second book, the Instructions.

1309 (January 4): Angela died in Foligno.

1701 (July 11): Angela formally received the title of “Blessed” by a decree of Pope Clement XI.

2013 (October 9): Angela was canonized by Pope Francis.

BIOGRAPHY

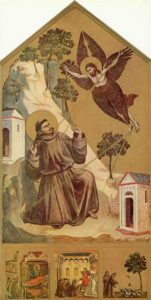

Although Angela of Foligno shares certain similarities with other women saints, she took a male saint as her model to guide her religious life. [Image at right] She admired St. Francis of Assisi (1181/1182–1226) and imitated many of his well-known religious practices and miracles. Francis was venerated as practicing the Imitatio Christi, that is, the imitation of Christ. Angela, in contrast, practiced the Imitatio Francisci of Imitatio Christi—imitating St. Francis who imitated Jesus Christ.

Following Jesus Christ through St. Francis and adopting their voluntary poverty, Angela repudiated worldly belongings and sought a simple life. By living as a poor person, she was able to reject worldly matters as well as bodily comfort and pleasure. Like Francis, Angela wanted to focus on heavenly matters and her relationship with God. She also wanted to help the poor, which Jesus encouraged his disciples to do in the Gospels.

Angela of Foligno was a rather ordinary woman who enjoyed worldly life before she began to have mystical visions, which were then recognized and valued by others. She was born in Foligno, Italy in 1248 or 1249. We know little about her apart from her own writings and a few documents that suggest her existence (Stróżyński 2018:188). Apparently, she was quite popular during her lifetime and was respected after her death (Arcangeli 1995:41). She was married and had children from this marriage, and was known to have run her own business, possibly in trade. It is not known if her wealth was comparable to St. Francis’ luxurious life before conversion. Angela joined religious life in her thirties, relatively late in life at that time.

Angela’s “secular” life was entirely changed in 1285. According to the Memorial, a book that describes her visions, Angela was seized by fear and guilt that her sin would lead her to hell. There is little evidence to show what her sin was (Lachance 1993:17). Whatever the sin was, she cried in despair and prayed to St. Francis for spiritual help and advice. Angela believed that Francis responded to her plea. According to Angela, the saint guided her to a church so she could find an appropriate confessor. Arnaldo, a Franciscan friar, became her confessor and scribe, writing down what Angela dictated in her local dialect, Umbrian, and then translating it into Latin (Lachance 2006:20). The original Umbrian transcription is lost, but twenty-nine manuscripts exist of her written visions, making it harder to distinguish her voice from the scribe’s possible intervention (Cervigni 2005:339–40). While there is less information available for the life of Arnaldo, he played a major role in hearing, writing, and editing the record of her visions. He became her first disciple (Lachance 2006:24). Undoubtedly others edited and redacted Arnaldo’s transcriptions, but they remain anonymous (Lachance 2006:85).

Angela’s religious life did not start easily. Her family opposed her decision to renounce secular life, even after her vision of St. Francis. In her forties, Angela took the habit in the Third Order of St. Francis, only after her own family members died. Perhaps not surprisingly, Angela expressed joy at the loss of her family, since she could now work as a spiritual mother to the poor and followers (Meany 2000:65), as well as become a faithful bride of Christ. The Third Order of St. Francis is a religious group of lay penitents, called tertiaries, founded by St. Francis. Its rule was set in 1289, but individuals and groups took various forms of devotional life, frequently remaining in the secular world. The Third Order generally gave women more opportunity to join a religious life that was not bound to monasteries (More 2014:297–99). As a tertiary, Angela lived at home with her companions while attending liturgies in nearby church on the regular basis (Schroeder 2006:36).

What little information we have about Angela of Foligno is compiled in Il Libro della Beata Angela da Foligno, which contains her book of visions, the Memorial, and her book of Instructions. The Memorial depicts the process of her mystical experience as passus or “steps” in English. These steps indicate the stages the soul encounters as it approaches perfect union with God. Unfortunately for modern researchers, her scribe Arnaldo had difficulties in distinguishing and organizing the steps (Schroeder 2006:41). In the first step, Angela confesses her sin. Subsequent steps are mixed in with Angela’s accounts of her repentance from sin and the consolation she received from God. Accounts of visions and mystical experiences are also included. Higher steps portray deepening levels of penance. In the nineteenth step, Angela tastes the “first great sensation of God’s sweetness” (Angela of Foligno 1993:131). In the final, twentieth step, she converts a man on his way to the church of St. Francis in Assisi. The other book compiled in Il Libro presents thirty-six Instructions, followed by descriptions of Angela’s death and an epilogue. Assembled by anonymous scribes after the Memorial—and possibly after Angela’s death (Mooney 2007:58)—the Instructions emphasize theological discourses between Angela and her scribe.

After fewer than two decades of living the religious life, Angela died in Foligno in 1309. In the early eighteenth century, Pope Clement XI (p. 1700–1721) awarded the title of “Blessed” to Angela, a step on the path to canonization. Pope Francis canonized Angela of Foligno as a saint in 2013, in the somewhat unique process of equipollent canonization—that is, she became a saint due to the longstanding veneration she received over the centuries.

DEVOTEES

During her lifetime, Angela attracted both men and women committed to becoming holy, and she herself founded a community of female tertiaries not bound by monastic enclosure. [Image at right] Yet Angela’s extraordinary behaviors made many people uncomfortable, which she reports in the Memorial. It is noteworthy that her book was more popular in European countries outside of Italy. The Memorial was widely circulated among the Spanish Franciscans, and Angela became a spiritual model during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Tar 2005:83). The Memorial was read in France by both the (vowed) religious and the nonreligious (laypersons) even before those in Italy saw it (Arcangeli 1995:44). Angela of Foligno’s book appears in the writings of later Italian mystics such as St. Francis de Sales (1567–1622) and St. Alphonsus Liguori (1696–1787), thus indicating her influence among later male mystics. With the recent recovery of significant female figures in Christian history, she has become the subject of study by feminist scholars and by those investigating mystical and ascetical traditions. At the same time, she retains appeal for traditionalists, being the saint that widows and those facing sexual temptation call upon.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

Late medieval Catholic Christianity, especially the mystical and ascetical traditions, emphasized the body (Bynum 1990:182). The body was seen to be an effective method by which to practice Imitatio Christi, to feel God’s presence, and to demonstrate miracles. St. Francis, the model that Angela followed, also exemplified the valorization of bodily pain and miraculous events, such as stigmata (Bynum 1990:86).

Angela went much further, however, in that her holy experiences and asceticism were what most people, even then, would consider extreme. Her writings—the Memorial and the Instructions—contain three narrators: Angela of Foligno, Arnaldo, and God (Lachance 2006:20). All three characters appear as “I,” the first-person pronoun, despite the different voices each represents, although the most frequent narrator is Arnaldo, conveying the opinion of the Church (Cervigni 2005:340–41). After Angela’s pilgrimage to Assisi in 1291, in a group of which Arnaldo was also a member, they started to write the Memorial. The Memorial is filled with accounts of her visions, ecstasies, and experiences of the presence and absence of God. The Instructions is more systematic and explanatory, presenting Angela as a spiritual mother and teacher. Here, she is talking to her spiritual sons and occasionally her spiritual daughters (Lachance 2006:81-82).

In both books, Angela of Foligno’s mystical experience develops in different steps, moving toward higher and deeper union with God, from her painful repentance of the sinful past to the ineffable experience of union with God accompanied by consolation. Lachance explains these developments in three stages:

(1) imitation of the works of the suffering God–man in whom is manifested God’s will; (2) union with God accompanied by powerful feelings and consolation that, nonetheless, can find expression in words and thoughts; and (3) a most perfect union with God in which the soul feels and tastes God’s presence in such a sublime way that it is beyond words and conception (Lachance 2006:35)

While the spiritual developmental stages are not always linear in her writings, Angela of Foligno yearns for the ultimate presence of God in her heart, which often fosters her frenzied behaviors or emotions. For example, her devotion to lepers bridged ascetic practice and mystical experience in outlandish ways, as she describes one incident:

And after we had distributed all that we had, we washed the feet of the women and the hands of the men, and especially those of one of the lepers which were festering and in an advanced stage of decomposition. Then we drank the very water with which we had washed him. And a small scale of the leper’s sores was stuck in my throat, I tried to swallow it. My conscience would not let me spit it out, just as if I had received Holy Communion. I really did not want to spit it out but simply to detach it from my throat (Angela of Foligno 1993:163).

Following the life of Jesus, and overcoming his pride and disgust, St. Francis of Assisi also reportedly kissed and helped lepers, saying he experienced joy (Orlemanski 2012:151). Angela of Foligno went even further, however, by drinking the leftover water and skin from the leper. Whereas St. Francis described being filled with a vague and somewhat nebulous sweetness at seeing the lepers (Francis of Assisi 1999:124), Angela reported a more physical and tangible sensation. For her, the “sweetness” was directly connected to her tasting the body of Christ and feeling the presence of God. These bodily impressions, along with visions of the body of Jesus, and miracles involving the host (the consecrated communion wafer), seemed to provide direction to Angela for understanding the will of God. In the lower steps in the Memorial, she expressed a kind of separation anxiety, saying that she felt insecure and miserable when she did not hear from God or feel God’s presence. However, as she was guided into the higher steps, experiencing sweetness and consolation in her body, she became more confident and certain of God’s love toward her. In a process of a deep union between Angela and God, she felt comforted. As a bride of Christ, Angela not only witnessed Christ but also touched and kissed his body. For her, God talked to her and guided her through her own body.

Opening the understanding of my soul, [God] answered: “Wherever I am, the faithful are also with me.” And I myself perceived that this was so. I also very clearly discovered that I was everywhere he was. But to be within God is not the same as to be outside of him. He alone is everywhere encompassing everything (Angela of Foligno 1993:217).

On the other hand, Angela’s mystical experiences were not always pleasant. She is famous for her extraordinary behaviors, including extravagant crying. After witnessing the passion of Christ in vision, Angela stated that she cried so hard that she felt her skin burning.

I wept much, shedding such hot tears that they burned my flesh. I had to apply water to cool it. In the eleventh step, for the aforesaid reasons, I was moved to perform even harsher penance (Angela of Foligno 1993:127).

The feeling of burning appears throughout the Memorial. Extreme levels of happiness, misery, pain, and joy are listed in her devotions without much elaboration. It seems as though Angela of Foligno had little opportunity to learn or write. She had no access to formal theology apart from traditions of the church that she learned from oral teachings. Many parts of her spiritual writings, therefore, show her inability to understand or explain her visions or emotional reactions. Angela’s theology was embedded in her mystical experiences and extraordinary behaviors. Throughout her Memorial, she expresses her unfulfilled love toward God with jealousy, happiness, anger, but seldom with satisfaction.

Following the prevalent medieval tradition of Sponsa Christi, “The Bride of Christ,” Angela of Foligno often describes her intimate relationship with Jesus. She treats Christ as her lover in many parts of the Memorial, expressing her eagerness to be united permanently with Christ. She voices her great love toward him throughout book. When she feels that she is with Christ, she is extremely happy. And when she feels his absence, she is acutely sad and depressed.

These representations are somewhat dissimilar to what other medieval mystics experienced, both male and female. Those who saw themselves as brides of Christ strove to make themselves pious and chaste wives of Christ. They did not care too much about worldly things but focused on Christ and love towards him. As a bride of Christ, they wanted to devote themselves entirely to him. Regardless of their actual gender, from the twelfth century onward even some male theologians began to see themselves as a wife of Christ and wrote about their love of him (Keller 2000:34–35). They described themselves as females, following the biblical Song of Songs tradition.

What is most interesting about Angela’s depiction of being the bride of Christ in the Memorial is that she describes in detail having actual physical contact between Christ and herself in her visions. Angela represents Jesus Christ as her lover. She yearns to touch and kiss him. He thus appears to her as fulfilling not only her religious desire, but also her bodily yearning. Here, the physical affection between lovers, which is discouraged as dangerous or understood as the result of Original Sin in the eyes of the Catholic Church, becomes embedded in holiness as spiritual lovers in the words of Angela.

[I]n a state of ecstasy, she found herself in the sepulcher with Christ. She said she had first of all kissed Christ’s breast—and saw that he lay dead, with his eyes closed—then she kissed his mouth, from which, she added, a delightful fragrance emanated, one impossible to describe. This moment lasted only a short while. Afterward, she placed her cheek on Christ’s own and he, in turn, placed his hand on her other cheek, pressing her closely to him. At that moment, Christ’s faithful one heard him telling her: “Before I was laid in the sepulcher, I held you this tightly to me” (Angela of Foligno 1993:182).

In this vision, Angela and Jesus Christ are apparently lovers. Angela touches him first, and then he embraces her back. In fact, the romanticized contact between Christ and his believers is not entirely different from the exegetical traditions of the Song of Songs, which was often understood by Christians as representing Christ and his believers as lovers longing for mystical union. After this physical and spiritual contact, she had great “immense and indescribable” pleasure, emphasizing her sensual satisfaction.

What is more, this passage represents Angela of Foligno as a savior herself, by implying that she is the one who revives and saves Jesus Christ from death. Angela first sees him lying in the tomb, which reminds readers of his death. However, no one witnessed the process of his resurrection, since he had already disappeared when his women followers, traditionally believed to include Mary Magdalene among them, visited his tomb. It is Angela who witnesses and “resurrects” Jesus Christ. Unlike various Gospel traditions, Angela describes herself actually seeing him lying in the tomb. At the sight of motionless Christ, she touches and kisses him. By her physical contact, he wakes up from death. Her kiss vivifies him, bringing him back to life. Then, Christ is able to respond to Angela’s touch by embracing her and uttering sweet words to her. Now, Angela could feel his breath after she kissed him first. In this vision, Angela of Foligno is the one who brings Jesus Christ back to life. And just as God breathed life into Adam (Genesis 2: 7), so too did Angela breathe life into Christ. Thus, Angela is the savior of the Savior.

Many medieval female saints pursued a mystical path of extreme asceticism. Whereas the early Christians sought torture and martyrdom as a part of their religious duty and practice, the medieval saints tried to imitate the suffering of Jesus Christ with voluntary self-inflicted pain and ascetic practice (Miles 2006:63). While both sexes were actively engaged in asceticism (Bynum 1987:42-47), female practitioners significantly adopted more severe habits of fasting (Bynum 1987: 87). Asceticism is also tied to the historical fact that medieval women did not have many opportunities for advancement. They were not allowed into priesthood, nor could they (officially) teach or preach. Women did not have many chances to get educated or study theology. Angela of Foligno was not far from this model. Bodily pain took priority in her mystical experiences. Vivid descriptions of fleshly agonies appear in most of the steps described in the Memorial. Angela constantly confesses that she is currently in physical pain and always yearning for it. She highlights her body as an important medium for delivering her pain and vision together. In this sense, we can say that Angela’s religious life begins with pain. Pain is not negative, although Angela seems to complain about it in the Memorial. Pain works importantly in her piety, guiding her to penance and confirming her sanctity.

On many occasions in the Memorial, Angela reports to her scribe that she goes through pain when she sees Jesus Christ in her visions.

At the tenth step, while I was asking God what I could do to please him more, in his mercy, he appeared to me many times, both while I was asleep and awake, crucified on the cross. He told me that I should look at his wounds. In a wonderful manner, he showed me how he had endured all these wounds for me; and he did this many times. As he was showing me the suffering he had endured for me from each of these wounds, one after the other, he told me: “What then can you do that would seem to you to be enough?” Likewise, he appeared many times to me while I was awake, and these appearances were more pleasant than those with occurred while I was asleep, although he always seemed to be suffering greatly (Angela of Foligno 1993:126–27).

Angela of Foligno’s understanding of Imitatio Christi included a physical dimension, as did that of her model, St. Francis. Just as Christ placed himself into human life, taking on mortality and physicality, as described in the Gospels, St. Francis also wanted to endure physical pain and even death in his religious life. Along with his voluntary poverty, Francis tried to avoid bodily comfort as much as possible. Rough clothes and a hard bed made him not only uncomfortable but also caused him agony. He and his followers were mocked by people who did not understand their ascetic practices. Being mocked like Jesus was a part of following the life of Jesus. The hagiographies of St. Francis and Angela emphasize the suffering caused by being mocked.

Perhaps St. Francis’ most notable characteristic in his quest to imitate Christ was the appearance of the Five Wounds of Jesus, miraculously engraved on his body. [Image at right] The Five Wounds of Christ, or stigmata, refers to physical wounds miraculously appearing on the bodies of the saints or holy people, typically hands, feet, side, or brow. In this incident, a seraph (a six-winged angel) appeared to Francis and shot light rays into his body in the exact places where Jesus was wounded when he was crucified. Angela of Foligno experienced the wounds of Christ somewhat differently:

In the fourteenth step, while I was standing in prayer, Christ on the cross appeared more clearly to me while I was awake, that is to say, he gave me an even greater awareness of himself than before. He then called me to place my mouth to the wound in his side. It seemed to me that I saw and drank the blood, which was freshly flowing from his side. His intention was to make me understand that by this blood he would cleanse me. And at this I began to experience a great joy, although when I thought about the passion I was still filled with sadness (Angela of Foligno 1993:128).

This rather graphic scene suggests that pain is something to be shared between Angela of Foligno and Christ. Her description suggests that “holy pain” was also a source of pleasure The wound on Christ’s side is the connection between them. Directly after this experience, Angela prayed to experience severe pain in order to compensate for Christ’s suffering and crucifixion. The pain originating from Christ was repeated through the religious lives of saints, including the Virgin Mary, St. John the Apostle, St. Francis of Assisi, and many medieval saints (Angela of Foligno 1993:224; Bynum 1987:5; Cohen 2000:61).

All pain is not the same, however, for Angela of Foligno. While she suffers pain for religious reasons and to help in her devotion, she attributes other pains to her unnamed sin or to devils.

To all this my soul felt the need to respond, for it was aware that each member of my body suffered from a particular infirmity, and it proceeded to identify the sins of each other. My soul then began to enumerate all the members and the sins proper to each one; it was aware of these sins and identified them with astonishing facility. [God] listened to everything patiently, and afterward he responded that it was a great delight for him to heal each infirmity immediately and in an orderly manner (Angela of Foligno 1993:155).

Angela tries to avoid the pain originating from evil spirits, and instead seeks the holy pain that is similar to or linked to Christ’s sacrifice. Although Angela sees the source of her pain as a result of her sin, she does not consider it entirely bad. Her corporeal pain is a helpful reminder that she can look back on her life and confess her sin. Also, it makes her able to consult with Christ regarding her sin. In the Gospels, Jesus said to people that he was a doctor and was needed by the sick, not the healthy. “It is not the healthy who need a physician, but they who are sick. For I have not come to call the just, but sinners” (Mark 2:17, trans. from Vulgate). Angela takes his words literally, believing that he will heal her body wherever she feels pain due to her vice.

A final type of pain is that of childbirth. Angela of Foligno bore several children, and thus experienced the pain of parturition. Although many female saints reported great pain in mind and body, Angela is unique in that she experienced both physical childbirth pain and spiritual sacrificial pain, both of which gave life to people. Her full experience of being a physical mother may partly explain her obsession with the physical body of Jesus Christ as a baby and lover.

Our Lady [Virgin Mary] totally reassured my soul, and she held forth her son to me and said: “O lover of my son, receive him” While saying these words, she extended her arms and placed her son in my arms. . . . Then suddenly, the child was left naked in my arms. He opened his eyes and raised them and looked at me. I saw and felt such a love for me as he looked at me that I was completely overwhelmed. I brought my face close to his, and pressed mine to him (Angela of Foligno 1993:273–34).

It seems that Angela of Foligno witnessed the young child Jesus Christ as well as a fully grown man, which can be understood as emphasizing the physical role of woman as a mother and partner, demanding the physical touch. This relationship was experienced by other female mystics in the Middle Ages (Bynum 1987:246)

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Caroline Walker Bynum has pointed out the extreme fasting and mystical sensations emphasized among medieval religious women (Bynum 1987). Bynum discussed the particular importance of food among the features represented in those religious women’s piety and related it to the intense physicality that was marked as a distinctly female characteristic. Medieval theology, as well as medicine, determined women as the more physical being due to Eve’s first sin, human reproduction, and their “weak” nature.

Angela of Foligno presents an example of this. Her womanly body defined her mystical experience. Though following the voluntary poverty and ascetic model of St. Francis of Assisi, she extended her mysticism in an embodied direction, relying upon her physicality and five senses more actively. [Image at right] She did not avoid describing her body explicitly while explaining her mystical experiences and God’s teaching. Her writings are full of sensual stimuli, bodily contacts, and physical longings for Christ, all focusing on her body. In Angela’s experience, her body functioned as a medium for receiving and delivering God’s teaching and as a tool to understand God’s will. Moreover, in Angela’s books, Christ affirms her body as innocent and lovable, thus creating a positive image of her female body.

Poverty was an important part of Angela’s practice, following the model of St. Francis of Assisi. Both St. Francis and Angela gave their own garments to the poor, but there were important differences in their poverty. For example, Angela gathered all the head coverings in her community of tertiaries and donated them to the hospital for the poor (Angela of Foligno 1993:162–63). They were ready to violate social customs if it was the right way of imitating St. Francis or Jesus Christ. Taking off the veil challenged ecclesiastical regulations because of the teaching of St. Paul (1 Corinthians 11). This could upset Church leaders and medieval male theologians arguing for the woman’s subjectivity, submission, and shame (Bain 2018:48–55).

Physical pain and other sensory stimuli are important features in Angela of Foligno’s mystical experiences. Sweetness in particular is the sensation that appears frequently related to her mystical experiences described in the Memorial. The taste of sweetness is one of the major bodily sensations that Angela relies on to express her elevated state of mind. It works as a positive sign to let Angela know that she is going in the right direction with her piety, visions, and practice. Contrary to the sensation of bitterness, sweetness gave Angela consolation and happiness by making her feel the presence and love of God.

There is no way that I could possibly render a just account of how great was the joy and sweetness I was feeling, especially when I heard God tell me: “I am the Holy Spirit who enters into your deepest self.” Likewise, all the other words he told me were so very sweet (Angela of Foligno 1993:141).

In this place she heard God speaking to her with words that were so sweet that her soul was immediately and totally restored. What he told her was: “My daughter, you are sweet to me”—and words that were even more endearing. But even before this, it seemed to her that God had already restored her soul when he had spoken to her as follows: “My sweet daughter, no creature can give you this consolation, only I alone” (Angela of Foligno 1993:169).

This sweetness is something Angela physically recognized with her sense of taste, not just allegorically or symbolically. Several times Angela confessed to her scribe that she felt sweetness eating the host, that is, the body of Christ. The Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the bread changes into the actual flesh of Jesus Christ during Eucharist) was a theological innovation in the Middle Ages. According to medieval theology, the Eucharist is a ritual bringing the moment back when Christ assumed the body of humankind and came to the world as a human so that he could die for the sake of others. The rite of Eucharist was especially popular with women because the body assumed an important role. According to Bynum, woman saints sought out the Eucharist frequently, and experienced miracles related to receiving the host (Bynum 1985:8–9). Thus, living in a misogynistic culture, women adopted a practice favorable to themselves and their  embodiedness.

embodiedness.

Angela of Foligno, who yearned to see, touch, and taste Christ’s body, was no exception. Like other female saints, she also wanted to receive the Eucharist as many times as she could. She wanted to receive communion every day (Angela of Foligno 1993:209). [Image at right] Once, Angela complained that she could not fully enjoy the moment of elevation of the host, blaming the priest for lowering the host too soon during Holy Communion (Angela of Foligno 1993:147). She reported that she was annoyed by that haste, since elevation of the host was the moment that she could see the beautiful body of Jesus Christ. She wanted to stay in this contemplative state longer.

Angela’s pleasure did not stop just at seeing the body of Jesus Christ. She also ate the body of Christ. Angela emphasized her sensual or physical responses when she took the host into her mouth and body.

In the [fifth supplementary] step, she reports after receiving communion, that she had just been granted a vision of God as the All Good. Further elaborating on the most recent effects of communion in her soul, she describes the host as more savory than any other food. It produces a most pleasant sensation as it descended into her body, and at the same time made her shake violently. To be noted in juxtaposition with this experience is an earlier episode in which, after having swallowed the water she had used to wash the sores of a leper, the taste of it was so sweet that she asserted it was like receiving holy communion (Lachance 1993:88).

Communion for Angela was not just about theology or mysticism. Seeing and eating the host brought her sensual pleasure. The Eucharist was something to satisfy her physically and spiritually. The carnality of the host was also highlighted by her confession that the host tasted like meat. According to Arnaldo, her scribe, writing in both the third person and the first person:

She then added that recently when she receives communion, the host lingers in her mouth. She said that it does not have the taste of any known bread or meat. It has most certainly a meat taste, but one very different and most savory. I cannot find anything to compare it to. The host goes down very smoothly and pleasantly not crumbling into little pieces as it used to do. . . . And I do so, the body of Christ goes down with this unknown taste of meat (Angela of Foligno 1993:186).

Angela described a moment when she swallowed the host. She confessed that the host not only gave her a “pleasant sensation” but also made her entire body tremble so much that she could barely hold the chalice (Angela of Foligno 1993:186).

On many occasions that Angela received visions, she felt intense sweetness, to which she became addicted immediately. The sense of sweetness occurred when she touched the body of Christ or ate it as a form of the host. Compared to this sweetness, mundane life seemed bitter and sad. On the other hand, the sweetness signaled to Angela that God accompanied her and that she was acting according to God’s will, which gave her a feeling of relief. This sweetness gave Angela such great pleasure that she constantly yearned for having this holy sweetness over and over again, which made her sorrowful without it. Then, her desire brought sweetness back to her, which Angela saw as a gift from God. As soon as this miraculous sensation returned to Angela, her sorrow disappeared. Although she could not explain how she felt with exact words, this sense comforted her. Angela wanted to die when she lacked this sweet sensation.

Bitterness, as another of the four basic taste sensations (salt, sweet, savory, bitter) is often referred to in the Bible to describe sadness, distress, disappointment, and anger. For example, Jesus described his coming persecution as a bitter cup (Matthew 26:37–46). Christ mentioned this cup in one of Angela’s visions.

And to those who are, strictly speaking, his sons, God permits great tribulations which he grants to them as a special grace so that they might eat with him from the same place. “For to this table, I was also called,” said Christ, “and the chalice that I drank tasted bitter; but because I was motivated by love it was sweet to me.” Thus for these sons who are aware of the aforesaid benefits and have received the special grace for it, even though they experience at times bitter tribulations, these, nonetheless, become sweet to them on account of the love and grace with which they are motivated. And they are even more in distress when they are not afflicted, for they know that the more they endure tribulations and persecutions, the more they will feel delight in and know God (Angela of Foligno 1993:161).

Angela applied the concept of bitterness to her feeling of the absence of God or lack of her conviction that God loved her. When Angela felt bitter, it meant that she was sad, depressed, or doubtful of God’s love. Until she arrived at the higher steps and the deeper level of mystical understanding, she was uncertain and hesitant regarding being a messenger of God. Just after the voices and consolation of God disappeared, Angela felt deserted and left behind. She described her pain of being parted from God as “bitter” and yearned for reunion with God.

Elsewhere in the Memorial, Angela reports a moment when she feels bitterness and sweetness at the same time. This experience is a clear example of how Angela depicts these two opposing sensations. The following passages describe Angela’s experience when she hears from God during her pilgrimage to Assisi.

[God speaking] “Thus I will hold you closely to me and much more closely than can be observed with the eyes of the body. And now the time has come, sweet daughter, my temple, my delight to fulfill my promise to you. I am about to leave you in the form of this consolation, but I will never leave you if you love me” (Angela of Foligno 1993:141).

Bitter in some ways as these words were for me to hear, I nonetheless experienced them above all as sweet, the sweetest I have ever heard (Angela of Foligno 1993:142).

Bitterness and sweetness alike frequently appear in Angela’s descriptions of her mystical experience, bridging her bodily sensations to God.

Finally, when Angela of Foligno was praying, she heard a voice that stated, “You are full of God.” She said that she heard it with her soul and then her body became full of the pleasant feeling of God (Angela of Foligno 1993:148). The feeling then expanded to the whole world. God said to Angela that, it is true that the whole world is full of her. God assured her that her body is full of God, which in turn produced an agreeable physical feeling. While her soul heard what God said, her body felt sensations which the presence of God poured into her. Then, Angela’s body expanded to the whole body of the universe. By confirming that God’s presence is all over the world, God demonstrated the goodness of creation through Angela’s vision. Here, Angela’s physicality worked as a kind of medium between God and the universe to deliver the presence of God to her.

As a medium between God and the world, Angela identified with Christ’s physical sensations, including his pain. Not only did Christ exist in all bodily members of Angela, but Christ also attributed his own sensations to Angela’s flesh, which gave her the opportunity to become like, or even to become, Christ. She felt the same pain as Jesus Christ did while suffering, thereby showing not only the closeness, but even the merging of Christ and Angela’s sensations (Hollywood 2002:72). Just as Jesus Christ went through many bodily afflictions, Angela received the same suffering. As he voluntarily took the pain to save humankind, Angela for years suffered the same torments to bring his message of salvation once more to all people. This message was brought by the bodies of Jesus Christ and Angela, connecting them and even identifying them.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

One challenge for understanding Angela of Foligno is that the Memorial and Instructions, the only known written works of Angela, are transcribed by a Friar Arnaldo. Thus, Angela’s voice is mediated by a man. Unlike the few female saints who were fortunate enough to be educated, Angela of Foligno was illiterate and unable to write down by herself what she went through. That is why Angela had to find a scribe, her cousin Arnaldo, to describe what she experienced. With Friar Arnaldo’s help, Angela composed an account of her visions and thoughts under the title Memorial in 1298 before recounting her visions and her own interpretations in the Instructions. However, she constantly complained that the scribe did not understand what she was reporting. These complaints were accepted and recorded faithfully by Friar Arnaldo. There seems to be a significant gap between Angela’s experience and Arnaldo’s writing that is acknowledged by both parties.

In truth, I [Arnaldo] wrote them, but I had so little grasp of their meaning that I thought of myself as a sieve or sifter which does not retain the previous and refined flour but only the most coarse. . . . I would add nothing of my own, not even a single word, unless it was exactly as I could grasp it just out of her mouth as she related it. I did not want to write anything after I had left her (Angela of Foligno 1993:137).

Arnaldo’s confession implies the possibility that Angela’s visions and interpretations may not be fully conveyed through the written word. This was a common problem for most medieval female mystics. At the same time, however, this fissure between Angela’s experience and Arnaldo’s written texts might be regarded as an effective rhetorical tactic designed to faithfully deliver Angela’s problematic visions while not losing his authority as a Franciscan friar and Angela’s scribe. Or, it may have been a strategy to give Angela more credibility by masking, or obfuscating, her more heretical comments. Arnaldo’s transcriptions give some space to the validity of Angela’s mysticism by his expressing his inability to understand her visions and by stating Angela’s self-confessed inability to describe her experiences fully. In any case, Arnaldo’ involvement in writing Angela’s narratives raises questions about his role as a commentator as well as a scribe (Cervigni 2005:342).

A second challenge is that Angela of Foligno faced the suspicion that she was preoccupied with sickness or evil spirits, and not God. This was another common problem medieval female mystics in Europe encountered (Lachance 1993:42). The difference between heretics and non-heretics was often arbitrary. Angela of Foligno was not entirely free from the threat of being condemned as a heretic, although she was not officially tested or subjected to an inquisition. Nevertheless, one of her few codices was found together with Marguerite Porete’s writings. Porete (1250–1310), a French mystic and the author of The Mirror of Simple Souls, was condemned as a heretic and burned at the stake in 1310 in Paris (Lachance 1993:112).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGION

Angela of Foligno [Image at right] was canonized in 2013 by Pope Francis, three hundred years after being beatified by Pope Innocent XII in 1697. This declaration skipped the formal procedure of canonization in the Catholic Church, recognizing her sainthood by being venerated by pious Catholics for a long time. This is aligned with the current movement of the Vatican to highlight more female saints. Although she was canonized almost 800 years after she died, Angela of Foligno is one of the most well-known medieval female Catholic saints. As the twentieth-century mystic Evelyn Underhill states in The Essentials of Mysticism, “excepting only St. Bonaventura, this woman has probably exerted a more enduring, more far reaching influence than any other Franciscan of the century which followed the Founder’s death” (1942:160).

Historically, Angela of Foligno influenced later mystical movements in Europe, especially among the Franciscan mystics. Initially, she seldom appears in Italian theological literature, unlike Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), who instantly achieved theological attention in Italian literature (Arcangeli 1995:42–44). Later Angela’s book started to being praised in writings, such as those of St. Francis de Sales (Devas 1953:28), and Pope Benedict XIV (p. 1740–1758). More recently, Angela of Foligno received attention from the Vatican, which pointed out that she exemplifies the importance of lay religiosity. For example, in a sermon given to the public in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI (p. 2005–2013) emphasized Angela of Foligno’s mystical union with God despite her worldly life to remind modern Catholics that God will be with them even though the world seems secular (Pope Benedict XVI 2010).

Outside of the Catholic Church, Angela of Foligno was highlighted by psychoanalytic and feminist scholars. Female mysticism in medieval Christianity was seen as an alternative to the hierarchical or elite Church. Medieval mystics, including Angela, were seen as more artistic, harmonious, and transcendental (Underhill 2002:74–76) in contrast to the artificial, hierarchical, and earthly institutions of the Church led by men. Underhill, for example, highlights Angela of Foligno as someone who achieved “a purged and heightened consciousness” in her visions (2002:219). French feminist philosopher and psychoanalyst Luce Irigaray interpreted Angela’s erotic mysticism as an embodied unconscious drive to “dismantle the phallocentric and logocentric” consciousness in Western culture (Hollywood 1994:168).

IMAGES

Image #1 Angela of Foligno, depicted in a 17th-century illustration. Wikimedia Commons.

Image # 2. Holy card depicting Jesus Christ appearing to Angela of Foligno. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #3: “Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata” by Giotto di Bondone (1295 to 1300). Wikimedia Commons.

Image # 4. Saint Angela of Foligno. 1890. Wikimedia Commons.

Image # 5. Saint Angela of Foligno. Brigade of Saint Ambrose.

Image # 6. Statue of Angela of Foligno. Franciscan Media.

REFERENCES

Angela of Foligno. 1993. Angela of Foligno: Complete Works, trans. Paul Lachance. New York: Paulist Press.

Arcangeli, Tiziana. 1995. “Re-Reading a Mis-known and Mis-read Mystic: Angela da Foligno.” Annali d’Italianistica 13:41–78.

Bain, Emmanuel, and Caroline Mackenzie. 2018. “Femininity, the Veil and Shame in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-century Ecclesiastical Discourse.” Clio: Women, Gender, History 47:45–66.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1985. “Fast, Feast, and Flesh: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women.” Representations 11:1–25.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1987. Holy Feast and Holy Fast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. 1991. “The Female Body and Religious Practice in the Later Middle Ages.” Pp. 161-219 in Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books.

Cervigni, Dino S. 2005. “Angela da Foligno’s Memoriale: The Male Scribe, the Female Voice, and the Other.” Italica 82:339–55.

Cohen, Esther. 2000. “The Animated Pain of the Body.” American Historical Review 105:36–68.

Devas, Dominic. 1953. “Blessed Angela of Foligno (1248–1305)” Life of the Spirit 8:27–36.

Francis of Assisi. 1999. “The Testament.” Pp. 124-27 in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents: The Saint, Volume 1, edited by Regis J. Armstrong, J. A. Wayne Hellmann, and William J. Short. New York: New City Press.

Hollywood, Amy. 2002. Sensible Ecstasy: Mysticism, Sexual Difference, and the Demands of History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hollywood, Amy M. 1994. “Beauvoir, Irigaray, and the Mystical.” Hypatia 9:158-85.

Keller, Hildegard Elisabeth. 2000. My Secret Is Mine: Studies on Religion and Eros in the German Middle Ages. Leuven: Peeters.

Lachance, Paul, ed. 2006. Angela of Foligno: Passionate Mystic of the Double Abyss. New York: New City Press.

Mazzoni, Cristina M. 1991. “Feminism, Abjection, Transgression: Angela of Foligno and the Twentieth Century.” Mystics Quarterly 17:61–70.

Meany, Mary Walsh. 2000. “Angela of Foligno: A Eucharistic Model of Lay Sanctity.” Pp. 61-76 in Lay Sanctity, Medieval and Modern: A Search for Models, edited by Ann W. Astell. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Miles, Margaret R. 2006. Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock.

Mooney, Catherine M. 2007 “The Changing Fortunes of Angela of Foligno, Daughter, Mother, and Wife.” Pp. 56-67 in History in the Cosmic Mode: Medieval Communities and the Matter of Person, edited by Rachel Fulton Brown and Bruce Holsinger. New York: Columbia University Press.

More, Alison. 2014. “Institutionalizing Penitential Life in Later Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Third Orders, Rules, and Canonical Legitimacy.” Church History 83:297–323.

Orlemanski, Julie. 2012. “How to Kiss a Leper.” Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies 3:142–57.

Pope Benedict XVI. 2010. “General Audience, Saint Peter’s Square, Wednesday, 13 October 2010.” Vatican. Accessed from https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2010/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20101013.html on 23 August 2022.

Schroeder, Joy A. 2006. “The Feast of the Purification in the Liturgical Mysticism of Angela of Foligno.” Mystics Quarterly 32:35-67.

Stróżyński, Mateusz. 2018. “The Composition of the Instructiones of St. Angela of Foligno.” Collectanea Franciscana 88:187–215.

Tar, Jane. 2005. “Angela of Foligno as a Model for Franciscan Women Mystics and Visionaries in Early Modern Spain.” Magistra: A Journal of Women’s Spirituality in History 11:83–105.

Thier, Ludger, and Abele Calufetti. 1985. Il Libro della Beata Angela da Foligno: Edizione critica. Grottaferrata, Romae: Editiones Collegii S. Boinaventurae ad Claras Quas.

Trembinski, Donna C. 2005. “Non alter Christus: Early Dominican Lives of Saint Francis.” Franciscan Studies 63:69–105.

Underhill, Evelyn. 1942. Mysticism: A Study in the Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness. London: Methuen. Reproduced by Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Accessed from https://ccel.org/ccel/underhill/mysticism/mysticism.i.html on 23 August 2022.

Publication Date:

24 August 2022