OOM THE OMNIPOTENT TIMELINE

1876 (October 31): Pierre Bernard was born as Perry Arnold Baker in Leon, Iowa.

1889: Bernard met his yoga teacher, Sylvais Hamati.

1893: Bernard and Hamati traveled to California.

1898: Bernard ran the San Francisco College for Suggestive Sciences. He performed the “Kali Mudra” stunt to advertise the power of yoga.

1902: Bernard was arrested for practicing medicine illegally.

1906: Bernard published Vira Sadhana: The International Journal of the Tantrik Order of America

1906: Bernard left San Francisco, traveling to Seattle and then New York City.

1910: Bernard was arrested in New York City on charges of abduction. The charges were subsequently dropped.

1918: Bernard and Blanche DeVries married.

1919: Bernard created the Braeburn Country Club in Nyack, New York, with funding provided by Anne Vanderbilt.

1919: State police raided the Braeburn Country Club

1924: Bernard expanded the Braeburn Country Club to become the Clarkstown Country Club.

1933: Bernard created the Clarkstown Country Club Sports Centre, with a baseball diamond and a football field.

1939: Boxer Lou Nova trained under Bernard for his bout against Max Baer.

1941: DeVries resigned from the Clarkstown Country Club, formalizing her separation from Bernard.

1955: Bernard died.

1956: DeVries sold the Clarkstown Country Club to the Missionary Training Institute.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Pierre Bernard, sometimes referred to as “Oom the Omnipotent,” was an early advocate of postural yoga in America. He created a number of short-lived organizations to promote yoga, Sanskri, and tantric teachings, including San Francisco College for Suggestive Therapeutics, The Tantrik Order of America, and the New York Sanskrit College. He finally found success in the Clarkstown Country Club, where he popularized postural yoga by training the wealthy, athletes, and celebrities.

Bernard demonstrated some genuine knowledge of hatha yoga, Vedic philosophy, and even tantric practices. However, he embellished this training with a good measure of charlatanism, especially in the first part of his career. After meeting his wife, Blanche DeVries, Bernard was able to make postu ral yoga acceptable to Americans by re-branding it as “physical culture” and a technique for achieving health, beauty, and athleticism. Prior to this, many Americans associated yoga and Hinduism with sexual deviance, primitivism, and white slavery. At their country club in Nyack New York, they trained heiresses, athletes, and celebrities, who further popularized yoga. For better or worse, Bernard pioneered an American movement that separated postural yoga from its Hindu roots, transforming it into a secular exercise form.

ral yoga acceptable to Americans by re-branding it as “physical culture” and a technique for achieving health, beauty, and athleticism. Prior to this, many Americans associated yoga and Hinduism with sexual deviance, primitivism, and white slavery. At their country club in Nyack New York, they trained heiresses, athletes, and celebrities, who further popularized yoga. For better or worse, Bernard pioneered an American movement that separated postural yoga from its Hindu roots, transforming it into a secular exercise form.

Pierre Bernard’s biography[Image at right] is challenging because he used numerous aliases and provided false details about his origins. The most authoritative sources record that he was born in 1876 as Perry Arnold Baker in Leon, Iowa (Love 2010:9). Bernard often claimed he had travelled in India, although this seems implausible. He did, however, meet a man named Sylvais Hamati in 1889 in Lincoln, Nebraska, who taught him hatha yoga and Vedic philosophy. Hamati’s background is also murky. He had come to America from Calcutta and may have worked as a performer prior to meeting Bernard. Bernard began studying under Hamati for three hours a day and, in 1893, they travelled to California (Love 2010:12-13). In San Francisco, Bernard was able to meet some early representatives of Hinduism in America, including Swami Vivekananda and Swami Ram Tirath (Laycock 2013:104).

With help from his uncle, Dr. Clarence Baker, Bernard established a business using his yogic training as a sort of holistic medicine. By 1898, Bernard had established a business called the San Francisco College for Suggestive Therapeutics. That year,  he performed a stunt called “the Kali Mudra” [Image at right] as a public demonstration of the power of yoga: Bernard entered a death-like trance and doctors were invited to probe or cut him in an attempt to elicit a response. In 1902, Bernard was arrested for practicing medicine illegally. This was the first of many obstacles as Bernard sought a way to earn a livelihood training Americans in yoga (Laycock 2013:104).

he performed a stunt called “the Kali Mudra” [Image at right] as a public demonstration of the power of yoga: Bernard entered a death-like trance and doctors were invited to probe or cut him in an attempt to elicit a response. In 1902, Bernard was arrested for practicing medicine illegally. This was the first of many obstacles as Bernard sought a way to earn a livelihood training Americans in yoga (Laycock 2013:104).

Bernard and Hamati were also experimenting with an esoteric group called The Tantrik Order of America. This group drew bohemians, actors, and artists, and offered training in Vedic philosophy, yoga, and tantra. Bernard had plans to create a network of Tantrik lodges in different cities; however, it remains unclear if significant groups were ever formed outside of San Francisco. In 1906, Bernard published the first and only volume of Vira Sadhana: The International Journal of the Tantrik Order of America. [Image at right] Bernard also created a social club known as “The Bacchante Club,” where men dressed in Oriental-inspired robes, smoked hookahs, and watched women  perform Oriental dances. The San Francisco police monitored The Bacchante Club, even sending in officers undercover (Love 2010:40). The police may have been motivated by sensationalized media stories about Hindu gurus mesmerizing and enslaving white women.

perform Oriental dances. The San Francisco police monitored The Bacchante Club, even sending in officers undercover (Love 2010:40). The police may have been motivated by sensationalized media stories about Hindu gurus mesmerizing and enslaving white women.

Bernard left San Francisco in 1906, possibly hoping to avoid police scrutiny. He and a few followers travelled to Seattle before re-locating to New Yo rk City. By 1910, Bernard had created a new Tantrik Order lodge on 74th Street in Manhattan. Once again, Bernard’s operation presented both an esoteric and an exoteric face: The lodge offered yoga classes to promote health and vigor as well as initiation into the secrets of the Tantrik Order (Laycock 2013:105).

Many of Bernard’s students were young women who had become interested in yoga after watching vaudeville performances of Oriental dancing. Bernard had a number of romantic relationships with his female students. One such student was Gertrude Leo, who had met Bernard in and followed him to New York. Bernard also had a relationship with Zelia Hopp. Hopp suffered from health problems and Bernard had approached her under the alias “Dr. Warren” and offered to help. On May 2, 1910, Hopp, along with Leo’s Sister, Jennie Miller, led detectives to Bernard’s school whereupon Bernard was arrested for abduction (Laycock 2013:105-06).

1910 was the same year that the Mann Act, also known as the White-Slave Traffic Act, was passed. Hopp and Leo’s story seemed to confirm many Americans’ worst fears about women being trafficked, and Bernard’s trial became a media coup. It was covered not only in New York City’s forty daily newspapers, but also in Seattle and San Francisco. Leo and Hopp reported that Bernard sometimes referred to himself as “the Great Om,” and by the afternoon after his arrest, headlines were calling him “Oom the Omnipotent.” They also claimed that Bernard had kept them in captivity using a combination of threats and hypnotic power. Bernard spent more than three months awaiting trial in the infamous Manhattan jail known as “The Tombs.” The case collapsed after Bernard’s lawyer was able to get Leo disqualified as a witness, and Hopp dropped all charges and fled New York City. With no witnesses, Bernard was released (Laycock 2013:107).

Bernard seems to have learned from this episode that Orientalist fantasies about yoga were a double-edged sword: They could attract clients in search of adventure, but they also played into a moral panic about gurus using nefarious forms of mind control to prey on women. During the trial Bernard insisted that yoga was merely “physical culture,” a talking point that he would continue to raise in the face of criticism.

Upon his release from The Tombs, Bernard moved to Leonia, New Jersey. When he returned to New York, he set up a new school, but this time he branded his teachings as academic, rather than esoteric. He called his new business the New York Sanskrit College and took the alias Homer Stansbury Leeds. He hired faculty from India to teach courses in Sanskrit, Vedic philosophy, Ayurvedic medicine, and Indian music. Unfortunately, the New York Sanskrit College was immediately the subject of rumors by neighbors and media in search of stories. The State Board of Education sent police to arrest him for running a “college” without any license or academic credentials. This time, Bernard evaded arrest end returned to Leonia (Laycock 2013:107-08).

In Leonia, Bernard began a new romance with the woman who would change his fortunes: Dace Shannon Charlot. Charlot had come to New York after leaving her abusive husband. Her divorce attorney also represented Bernard. Charlot’s divorce had attracted some media attention, which she hoped to use to launch a career in vaudeville. She changed her name to Blanche DeVries and studied dance at the New York Sanskrit College. [Image at right] Bernard and DeVries married in 1918, and in their letters the two refer to each other as “Shiva” and “Shakti,” respectively. DeVries understood how to find the right market for Bernard’s teachings. Bernard ceased fleeing police, holding “Bacchante Club” meetings, or using aliases. With DeVries’s guidance, Bernard opened several yoga studios around New York aimed exclusively at women (Laycock 2013:108).

One of Bernard’s new students was Margaret Rutherford, daughter of Anne Vanderbilt. In 1919, Mrs. Vanderbilt funded the Braeburn Country Club in Nyack, New York (Laycock 2013:108). The Club attracted wealthy aristocrats who sought to improve their health and relieve their boredom by studying yoga. The town was initially hostile to Bernard. There were rumors that Bernard ran “a love cult” and that he performed abortions. In its first year, mounted state police raided the club (Randall 1995:83). But Bernard soon became an important taxpayer and even a pillar of the community. In 1922, the New York Times wrote of him, “The ‘‘Omnipotent Oom’ . . . is known here simply as Mr. Bernard, one of the most active and patriotic townspeople of Nyack.”

In 1924, Bernard spent $200,000 purchasing and developing an additional seventy-six acres for his estate, renaming it the Clarkstown Country Club (Laycock 2013:108). This was followed by the creation of the massive Clarkstown Country Club Sports Centre in 1933, which featured a baseball diamond, a football field, and impressive electric lights (Love 2010:250). At the height of his career, Bernard owned $12,000,000 in real estate. He was the president of a county bank, owned a mortgage company, a reconstruction corporation, and a large realty company, and was the treasurer of the Rockland County Chamber of Commerce (Clarkstown Country Club 1935:124).

However, Bernard never shed his flamboyant style completely, which attracted more patrons to his club. He purchased a troupe of elephants as well as several apes and other exotic animals. The elephants were featured in an annual circus in which students performed as acrobats. Bernard also invented the sport of “donkey ball,” a variant of baseball with all players (save the catcher and pitcher) mounted on donkeys (Love 2010:274).

The club became a hub for Americans who were integrating Asian religions into American culture. Bernard’s nephew, Theos Bernard, travelled to Tibet before receiving his doctorate from Columbia University and publishing a classical text on hatha yoga. Bernard’s half-sister married Hazra Inayat Khan, the founder of The Sufi Order International (Ward 1991:40). The biochemist Ida Rolf studied under Bernard, and her physical therapy technique of structural integration or “rolfing” has similarities to the scientific approach to yoga advocated by Bernard (Stirling and Snyder 2006:8). In her youth, Ruth Fuller Sasaki spent time at the Clarkstown Country Club as therapy for her asthma (Stirling and Snynder 2006:6). She went on to be instrumental in importing Zen Buddhism to America, translating important several important texts into English.

In 1939, heavyweight boxer Lou Nova arrived at the country club to study yoga. The training had been conceived as a stunt to promote his upcoming fight with Max Baer. Nova learned headstands, meditation, and boxed with one of Bernard’s elephants, which had been trained to wear one oversized glove on its trunk. Newspapers reported that Nova had mastered “the cosmic punch” under Bernard’s training. Later, Nova patented a device called the “yogi nova” to assist practice with headstands (Laycock 2013:125). Figures like Nova helped to broadcast the idea to Americans that yoga could give athletes an edge.

By the end of the 1930s the Clarkstown Country Club had started a slow decline. Bernard also became estranged from DeVries, and in 1941 she resigned from the Club, formalizing her separation from Bernard (Love 2010:304). Bernard died in 1955. The following year, the nearby Missionary Training Institute purchased the land. Today, Nyack College stands on the former site of the Clarkstown Country Club. The campus folklore includes stories about paranormal phenomena left behind by the strange rituals allegedly performed by Pierre Bernard (Swope 2008).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Clarkstown Country Club had a sizeable library and Bernard lectured on a wide variety of topics. However, little is known about his actual beliefs regarding yoga and tantra. This problem is rendered more difficult by the fact that he catered his teachings to his audience, presenting himself as an esoteric master in some contexts, a holistic healer in others, and an athletic trainer in still others. There is no record of Bernard discussing doctrines of Hinduism such as karma, reincarnation, or moksha (liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth). Perhaps Bernard was most honest in a 1939 interview for American Weekly when he stated, “Yoga’s my bug, that’s all. Like another guy will go in for gardening or collecting stamps” (Love 2010:296).

There is some evidence that while he was running The Tantrik Order Bernard understood himself to be a traditional tantric guru and expected his initiates to regard him as having a quasi-divine status. This may be how Bernard regarded his own teacher, Sylvais Hamati. Intriguingly, Bernard’s publication Vira Sadhana contains an illustration of the Greek god Bacchus holding a staff and states that he came from India (Tantrik Order of America 1906:49). There are, of course, legends tying Bacchus’s Greek counterpart, Dionysus, to Asia. Bernard’s Bacchante club was named after Bacchus and Bernard may have believed that the Greek mystery schools were, in fact, a form of tantra imported from India.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

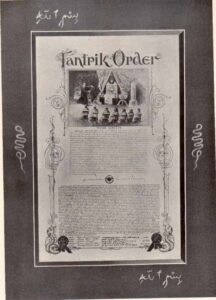

Little is known about the Tantrik Order of America. [Image at right] It apparently had seven degrees of initiation, each of which required a blood oath. Women were allowed to join, as was revealed by testimony during Bernard’s 1910 trial for abduction. The Order seemed loosely modeled on Freemasonry, and its chapters were called “lodges.”

In New York City, we have some descriptions of Bernard’s yoga classes, which seem to have added elements of the exotic. A detective testifying at Bernard’s trial described students tumbling on a mat with “strange figures” on it while Bernard stood near a crystal ball (Laycock 2013:106). These esoteric elements were largely dropped by the time Bernard was running a country club. Bernard does seem to have pioneered important material aspects of American postural yoga, such as having specialized mats and having students wear tights while training.

The Clarkstown Country Club emphasized physical culture and adult education with a heavy dose of play and whimsy. A stone pediment at the gate stated, “HERE THE PHILOSOPHER MAY DANCE AND THE FOOL MAY WEAR A THINKING CAP” (Boswell 1965). In addition to yoga classes, Bernard would lecture on a wide range of topics and maintained a large library. The Club forbade sex, liquor, and smoking, at least officially. Bernard still consumed cigars, and skinny-dipping was reported to be a popular activity.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Bernard seems to have regarded Sylvais Hamati as his guru. During his time in New York there were rumors that Bernard encouraged his students to think of him as a god. While this behavior disturbed Americans, it makes more sense in the context of tantra where gurus are understood as having a divine status. Bernard was also rumored to sometimes be deliberately off-putting around new students, doing things like chomping cigars and spitting near their feet, to test whether they were worthy to study under him (Watts 2007:120).

DeVries seems to have been essential in helping Bernard to rebrand himself. However, she does not seem to have been an equal partner in teaching yoga or running the finances of the Clarkstown Country Club. Despite their estrangement, she was left as Bernard’s sole heir and executress upon his death.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Bernard’s lifelong challenge was getting Americans to overcome their negative attitudes toward yoga, which were rooted in bigoted fear of Hinduism, racist attitudes toward Asians, Victorian attitudes about the body and sexuality, and a moral panic over white slavery. Of course, many Americans were interested in yoga because of Orientalist fantasies about beautiful dancing harem girls and athletic, savage men. Bernard was not above catering to these fantasies, which caused many to perceive him as a charlatan. He was ultimately able to strike a balance in which he made yoga appealing to those seeking beauty and athleticism without seeming scandalous.

Since Bernard, many Americans now associate yoga not with mysticism but with posh yoga supplies and vain people sculpting their bodies. Groups such as the Hindu American Foundation have expressed frustration that Americans have divorced yoga from its roots in Hinduism and turned it into a form of secular exercise (Vitello 2010). Bernard was clearly interested in Vedanta philosophy and would likely have taught a less secular form of yoga, if only Americans been ready for this in the first decades of the twentieth century.

IMAGES

Image #1: Pierre Bernard.

Image #2: Bernard performing the Kali Mudra.

Image #3: Vira Sadhana: The International Journal of the Tantrik Order of America.

Image #4: Blan.che DeVries.

Image #5: Clarkstown Country Club.

Image #6: Tantric Order of America charter document.

REFERENCES

Boswell, Charles. 1965. “The Great Fuss and Fume Over the Omnipotent Oom.” True: The Man’s Magazine, January. Accessed from http://people.vanderbilt.edu/~richard.s.stringer-hye/fuss.htm on 22 November 2008.

Clarkstown Country Club. 1935. Life at the Clarkstown Country Club. Nyack, NY: The Club.

Laycock, Joseph. 2013. “Yoga for the New Woman and the New Man The Role of Pierre Bernard and Blanche DeVries in the Creation of Modern Postural Yoga.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 23:101-36.

Love, Robert. 2010. The Great Oom: The Improbable Birth of Yoga in America. New York: Viking.

Randall, Monica. 1995. Phantoms of the Hudson Valley: the Glorious Estates of Lost Era. New York: Overlook Press.

Stirling, Isabel and Gary Snyder. 2006. Ruth Fuller Sasaki: Zen Pioneer. New York: Shoemaker and Hoard Publishers.

Swope, Robin S. 2008. “The Specters of Oom” The Paranormal Pastor, July 1. Accessed from http://theparanormalpastor.blogspot.com/2008/07/specters-of-oom.html on 3 March 2021.

Tantrik Order of America. 1906. Vira Sadhana: International Tantrik Order vol 1: issue 1. New York: Tantrik Press.

Ward, Gary L. 1991. “Bernard, Pierre Arnold.” Pp. 39-40 in Religious Leaders of America, edited by J. Gordon Melton. New York: Gale.

Watts, Alan. 2007. In My Own Way: An Autobiography 1915-1965. New York: New World Library.

Vitello, Paul. 2010. “Hindu Group Stirs a Debate Over Yoga’s Soul” New York Times, November 27. Accessed from https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/28/nyregion/28yoga.html on 3 March 2021.

Publication Date:

9 April 2021