APOSTOLIC UNITED BRETHREN TIMELINE

1843: Joseph Smith announced his revelation on plural marriage.

1862: The U.S. Congress passed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act.

1882: The U.S. Congress passed the Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act.

1886: John Taylor received a revelation about the continuation of plural marriage.

1887: The U.S. Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act.

1890 (October 6): Wilfred Woodruff announced a Manifesto forbidding plural marriage.

1904-1907: Hearings were held in the U.S. Senate on the seating of Reed Smoot as Senator from Utah.

1904 (April 6): A second Manifesto was issued by Joseph F. Smith that threatened excommunication for LDS members who engaged in plural marriage.

1910: The LDS Church began a policy of excommunication for new plural marriages.

1929-1933: Lorin C. Woolley created the “Council of Friends.”

1935 (September 18): Lorin C. Woolley died, and Joseph Leslie Broadbent became head of the Priesthood Council.

1935: Broadbent died, and John Y. Barlow became head of the Priesthood Council.

1935: The Utah legislature elevated the crime of unlawful cohabitation from a misdemeanor to a felony.

1941: Leroy S. Johnson and Marion Hammon were ordained to the Priesthood Council by John Y. Barlow.

1941: Alma “Dayer” LeBaron established Colonia LeBaron in Mexico, as a refuge for those who wanted to practice plural marriage

1942: The United Effort Plan Trust was established.

1944 (March 7-8): The Boyden polygamy raid was conducted.

1949: Joseph Musser had a stroke and called his physician, Rulon C. Allred, to be his second elder.

1952: The Priesthood Council split into two groups: the FLDS (Leroy S. Johnson) and the Apostolic United Brethren (Rulon Allred).

1953 (July 26): The raid on the polygamist community at Short Creek was conducted.

1951-1952: With Joseph Musser’s death, Rulon Allred became the head of the Priesthood Council.

1960: Rulon Allred bought the 640 acres in Pinesdale, Montana as a polygamist haven.

1977: Rulon Allred was killed by a female assassin sent by Ervil LeBaron; Owen Allred took the helm.

2005: Owen Allred died at the age of ninety-one, after appointing Lamoine Jensen to be his successor.

2014 (September): Lamoine Jensen died of colon cancer.

2015: Lamoine Jensen’s death led to a major split in the group, with some following Lynn Thompson and others following Morris and Marvin Jessop. The Montana order became known as the “Second Ward.”

2021 (October 5): Lynn Thompson died; David Watson became the prophet.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

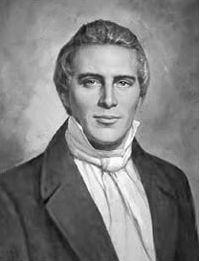

Although many mainstream Mormons seek to distance themselves  from the practice, polygamy first arose in the Mormon context in 1831 when Joseph Smith Jr., [Image at right] founder of the Mormon Church, also known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, claimed to have a revelation that it was his duty to restore plural marriage to the earth. Smith, who married at least thirty-three women and had children with thirteen of them, claimed that he had been given the authority to practice “celestial marriage” from the same source that commanded Abraham to take his handmaid, Hagar, to bed in order to produce a righteous seed and glorious progeny. Smith, like others of his era in western New York, was caught up in the “American dream of perpetual social progress, believing in a unique theology made up of an eternal monopoly of resources (including women) by males and whole congeries of gods” (Young 1954:29). Smith described a vision he had of God and Christ together in a grove of trees in which Christ told him that he would be instrumental in restoring the true gospel.

from the practice, polygamy first arose in the Mormon context in 1831 when Joseph Smith Jr., [Image at right] founder of the Mormon Church, also known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, claimed to have a revelation that it was his duty to restore plural marriage to the earth. Smith, who married at least thirty-three women and had children with thirteen of them, claimed that he had been given the authority to practice “celestial marriage” from the same source that commanded Abraham to take his handmaid, Hagar, to bed in order to produce a righteous seed and glorious progeny. Smith, like others of his era in western New York, was caught up in the “American dream of perpetual social progress, believing in a unique theology made up of an eternal monopoly of resources (including women) by males and whole congeries of gods” (Young 1954:29). Smith described a vision he had of God and Christ together in a grove of trees in which Christ told him that he would be instrumental in restoring the true gospel.

Although Smith disclosed the Principle of Plural Marriage in 1843, it was practiced for several years after that in secret in Nauvoo, Illinois. In 1852, Brigham Young, leader of the Mormon Church), revealed the practice of plural marriage as a Mormon doctrine. When Mormons received the revelation regarding polygamy, its supporters argued that while monogamy was associated with societal ills such as infidelity and prostitution, polygamy could meet the need for sexual outlets outside marriage for men outside marriage in a more benign way (Gordon 2001). Young, hesitant at first, eventually overcame his timidity and married fifty-five wives. He had fifty-seven children by nineteen of the wives he slept with. In its heyday in Utah territory, however, polygamy was practiced by only about fifteen percent to twenty percent of LDS adults, mostly among the leadership (Quinn 1993). Although plural marriage was practiced openly in the Utah Territory, it wasn’t until 1876 that it became an official religious tenet that was included in the Doctrine and Covenants.

Politicians in Washington did not welcome this innovation. In 1856, the platform of the newly founded Republican Party committed the party to prohibit the “twin relics of barbarism”; polygamy and slavery. In 1862, the federal government outlawed polygamy in the territories through passage of the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act. Mormons, who were the majority residents of the Utah territory, ignored the act.

However, prosecutions for polygamy proved difficult because evidence of unregistered plural marriages was scarce. However, in 1887, the Edmunds-Tucker Act made polygamy a felony offense and permitted prosecution based on mere cohabitation. The spouses did not need not to have gone through any ceremony to be accused of Polygamy without purporting to create a legal marriage. Scores of polygamists, including my own ancestors, Angus Cannon and his brother George Q. Cannon, were each sentenced to six months of in prison in 1889. The final blow to the viability of nineteenth century Mormon polygamy came that same year when Congress dissolved the corporation of the Mormon Church and confiscated most of its property. Within two years, the government also denied the church’s right to be a protected religious body. This policy of removal of church resources meant that polygamous families with limited funding had to abandon these extra wives who had been deemed illegal under the Edmunds Act. This abandonment created a large group of single and impoverished polygamous women who were no longer tied to their husbands religiously or economically. As a result of the pressures brought on by the Edmunds-Tucker Act, the LDS church renounced the practice of polygamy in 1890 with church president Wilford Woodruff’s manifesto. Utah was admitted into the Union in 1896. As a result of anti-polygamy legislation, many advocates of plural marriage began an exodus to Mexico in 1885 to avoid prosecution. There, they created a small handful of colonies, three of which are still intact today.

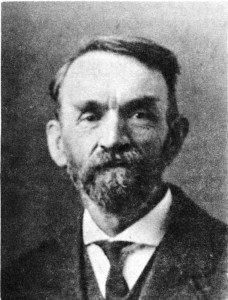

Interestingly, many members of the LDS Church, including my own Cannon and Bennion ancestors and President Woodruff himself (Kraut 1989), continued to obtain wives long after the 1890 manifesto prohibited it. In 1904, to address the continued practice of contracting plural marriage, Joseph F. Smith issued a manifesto that was designed to eradicate polygamy once and for all. Fundamentalist Mormons believe that both manifestos were used to manipulate the holy covenants for political gain (Willie Jessop, quoted in Anderson 2010:40); they believe that God had secretly transferred the power to continue polygamy to John Taylor (third prophet of the church) through a revelation in 1886. This revelation was the defining narrative for fundamentalists and led to their separation from the mainstream church (Driggs 2005). Taylor claimed that while he was hiding in John Woolley’s home in Centerville, Utah, he spent a whole night with Joseph Smith, who commanded him to continue the practice of polygamy. John Woolley’s son, Lorin, a bodyguard to the prophet, was present during a clandestine meeting on September 27 in the Woolley household. At this meeting John Taylor ordained George Q. Cannon, John W. Woolley, Samuel Bateman, Charles Wilkins, and Lorin Woolley as “sub rosa” priests and gave them the authority to perform plural marriages. John Woolley was first given the keys to the  patriarchal order, or priesthood keys. He subsequently passed them to Lorin, [Image at right] who was later excommunicated by the LDS Church for “pernicious falsehood.”

patriarchal order, or priesthood keys. He subsequently passed them to Lorin, [Image at right] who was later excommunicated by the LDS Church for “pernicious falsehood.”

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the legal status of polygamy in Utah was still not clear. In 1904, the US Senate held a series of hearings after LDS apostle Reed Smoot was elected as a senator from Utah. The controversy centered on whether or not the LDS church secretly supported plural marriage. In 1905, the LDS church issued a second manifesto that confirmed the church’s renunciation of the practice, which helped Smoot keep his senate seat. Yet the hearings continued until 1907, the Senate majority still interested in punishing Smoot for his association with the Mormon church. By 1910, Mormon leadership began excommunicating those who formed new polygamous alliances, targeting underground plural movements. From 1929 to 1933, Mormon fundamentalist leadership refused to stop practicing polygamy and was subject to arrest and disenfranchisement. In 1935, the Utah legislature elevated the crime of unlawful cohabitation from a misdemeanor to a felony. That same year, Utah and Arizona law enforcement raided the polygamous settlement at Short Creek after allegations of polygamy and sex trafficking.

From 1928 to 1934, Lorin C. Woolley led a group called the Council of Seven, also known as the Council of Friends. This group was comprised of Lorin Woolley, John Y. Barlow, Leslie Broadbent, Charles Zitting, Joseph Musser, LeGrand Woolley, and Louis Kelsch. Woolley claimed that the council was the true priesthood authority on earth and had previously existed, in secret, in Nauvoo, Illinois. This underground movement reinforced some of the early doctrines of Brigham Young such as communalism, the Adam-God belief, and plural marriage. Leaders of the movement claimed that the LDS Church had lost its authority to gain direct revelation from God when it discontinued the holy principle of plural marriage during the Woodruff presidency.

Although the Council of Friends started in Salt Lake, it moved its order to the town of Short Creek on the Utah-Arizona border in order to avoid prosecution. Short Creek set the stage for the first attempt to create a United Order or Effort, to help organize properties and manage lands. The location, surrounded by majestic red rock buttes and tiny fertile creek beds, was consecrated by Brigham Young, who said it would be the “head not the tail” of the Church. For a decade it was the gathering place for many members of the LDS Church who wanted to keep polygamy alive. The members of the Council of Friends were generally in agreement about how to run the underground priesthood movement, and the population of adherents to Mormon fundamentalism began to grow, mostly through natural increase and the immigration of disgruntled members of the Mormon Church who wanted to live the “old ways.” In 1935, the LDS Church asked Short Creek members to support the presidency of the church and sign an oath denouncing plural marriage. This request was not well received with twenty-one members, who refused to sign and were subsequently excommunicated. Several members were jailed for bigamy.

Coinciding with the organization of Short Creek was the development of a fundamentalist movement in Colonia Juarez in northern Mexico. Benjamin Johnson, a member of the Council of Fifty (a new world government orchestrated in Brigham Young’s time), claimed to have obtained the priesthood keys from Young. He, in turn, gave them to his great-nephew, Alma “Dayer” LeBaron. Dayer later established Colonia LeBaron, located eighty miles southeast of Colonia Juarez in Galeana, as a refuge for those who wanted to practice plural marriage.

Meanwhile, back in Short Creek, the council leadership shifted from Lorin C. Woolley, who died in 1934, to J. Leslie Broadbent, who led until his death in 1935. John Y. Barlow then took over as prophet from 1935 to 1949, after which Joseph Musser controlled the priesthood council. Musser and L. Broadbent wrote the Supplement to the New and Everlasting Covenant of Marriage (1934), which established three degrees of priesthood leadership: 1) the true priesthood made up of high priests, anciently known as the Sanhedrin, or power of God on earth; 2) the Kingdom of God, the channel through which the power and authority of God functions in managing the earth and “inhabitants thereof in things political;” and 3) the Church of Jesus Christ (the LDS Church), which has only ecclesiastical jurisdiction over its members. The first category, according to Musser, was comprised of the fundamentalist key holders, himself and other members of the council. The second category referred to the large body of general members, who were in service to the key holders. The third referred to the mainstream orthodox church, which no longer had direct authority to do God’s work but still provided a valuable stepping-stone to the next top levels.

In 1944, during Barlow’s leadership, the U.S. government raided Short Creek and the Salt Lake City polygamists, putting fifteen men and nine women in the Utah State Prison. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the legal status of polygamy in Utah was still not clear.

On July 26, 1953, another raid swept over Short Creek. After this raid, thirty-one men and nine women were arrested and 263 children were taken from their homes and put into state custody. Of the 236 children, 150 were not allowed to return to their parents for more than two years.

Other parents never regained custody of their children. Prior to the raid, the Short Creek priesthood council had begun to split apart, fulfilling a prophecy by John Woolley many years before that “a generation yet unborn, along with some of the men who are living here now, are going to establish groups . . . [and] . . . would contend among each other, that they would divide, that they would subdivide and they would be in great contention” (quoted in Kraut 1989:22).

After Joseph Musser had a stroke in 1949, he called his physician, Rulon C. Allred, [Image at right] to be his second elder. In 1951, Musser recovered enough to join Richard Jessop in voting Rulon in as patriarch of the priesthood council. Musser’s decision was vetoed by most of the council, who were absent during the appointment of Rulon, inspiring contentions and different interpretations over who would be the “one mighty and strong.” This bickering split the original movement. Rulon Allred led one faction and Louis Kelsch headed the other. Leroy S. Johnson and Charles Zitting, who were loyal to Kelsch, remained in Short Creek, where they created the official Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while Musser, Jessop, and Allred began work to start a new movement, which eventually became known as the Apostolic United Brethren. This latter group created a new council in 1952 made up of E. Jenson, John Butchereit, Lyman Jessop, Owen Allred, Marvin Allred, and Joseph Thompson. Although this split led to major changes in the expression of Mormon fundamentalism, all contemporary groups whose origins lie in the original Short Creek movement share common threads of kinship, marriage, and core beliefs.

DOCTRINE/BELIEFS

Mormon fundamentalists are those who subscribe to a brand of Latter-day Saint theology founded by Joseph Smith that includes polygamy, traditional gender roles, and religious communalism. About seventy-five percent of these polygamists come from the three largest movements: the Apostolic United Brethren (AUB or Allred Group), the Fundamentalist Latter-day Saints (FLDS), and the Kingston Clan. The remainder come from the small LeBaron community in Mexico and unaffiliated polygamists spread throughout the western United States who are known as “independents.” These schismatic sects and individuals are dedicated to an Abrahamic kingdom-building paradigm that leads to the ultimate goal of entering the celestial presence of Elohim, the Father.

To summarize the differences of AUB fundamentalists from the mainstream church, polygamist Ogden Kraut (1983) lists several key issues: the practice of polygamy, the practice of missionary work, beliefs about the priesthood, the adoption of the United Order, belief in the concept of the gathering of Israel, belief in the Adam-God theory, adoption of the concept of the “one mighty and strong,” development of the concept of Zion, beliefs about blacks and the priesthood, and belief about the kingdom of God. The Adam-God doctrine is a theological idea taught by Brigham Young that Adam was from another planet and came to earth as Michael, the angel. He then became a mortal man, Adam, establishing the human race with his second wife, Eve. After his ascent to heaven, he served as God, the Heavenly Father of humankind.

Fundamentalists also differ in their association of the “fulness of times” with plural marriage and their belief that one must acquire wives through the Law of Sarah to attain the highest glories of the Celestial Kingdom.6 They also believe that the gospel is unchanging; accordingly, if God told Joseph Smith to practice polygamy, it should be practiced today and always. In other words, truth is a knowledge of “things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come” (Doctrine and Covenants 93:24). Smith also stated that if “any man preach any other gospel than that which I have preached, he shall be cursed” (Smith 1838:327) and that God “set the ordinances to be the same forever and ever” (Smith 1838:168).

Endowment rites, fundamentalists feel, should therefore not be altered, as they were in 1927, when LDS apostle Stephen Richards renounced the Adam-God doctrine and removed its associated symbols from the priesthood garment (Richards 1932), and in the 1990s, when LDS prophet Ezra T. Benson reformed the ceremony to allow women to have a direct pathway to God rather than having to go through their husbands or fathers. The latter change also removed the punishment symbols and gestures used to illustrate what might befall one if the sacred rites were divulged, not unlike those used by the Masons. The LDS Church also altered the rite that brings Saints into God’s presence and shortened and modernized the holy garment. Fundamentalists believe that the rites and symbols that were lost should be reinstated and that women must go through their Saviors on Mt. Zion in their pathway to God. They also maintain that the exact words in sacred ceremony, the ones used in Joseph Smith’s day when priesthood blessings were conferred, should be used in the modern day, spoken in nineteenth-century verse.

Many members of the AUB also reject the 1978 revelation given to President Kimball that allowed blacks to enter the priesthood (Doctrine and Covenants, Declaration 2). They believe that God told Joseph Smith that “negroids” are marked by the blood of Cain and would defile the priesthood and the temples. The FLDS removed a Polynesian from their midst, stating that he was too dark, and they frown on interracial marriages of any kind. Brigham Young sanctioned such beliefs when he wrote that that blacks “are low in their habits, wild and seemingly deprived of nearly all the blessings of the intelligence that is generally bestowed upon mankind” (Young 1867:290). The AUB and LeBarons are also against blacks but allow mixed alliances with both Hispanics and Polynesians. Nevertheless, the AUB removed Richard Kunz (an individual who is phenotypic white and genotypic black) from his position on the priesthood council.

Another difference between the LDS Church and the AUB is that they believe that God’s law is intended to surpass man’s laws. Although welfare fraud, bigamy, the collection of illegal armaments, or certain types of home schooling may be against the civil law, they are means of following the higher mandate of providing for large numbers of children (Hales 2006). It should be noted that some polygamist communities, such as Pinesdale, Montana, work very closely with law enforcement and are law abiding. They register any sex offenders and excommunicate any criminals.

The AUB also feels that missionary work should be conducted as Joseph Smith commanded it, without “purse or scrip,” meaning without financial support. They also disagree with the mainstream church’s identification of Independence, Missouri, as the “one place” for the gathering of Zion. This location is also known as Adam-ondi-Ahman, or the former Garden of Eden. Most fundamentalists feel that Zion is located in the Rocky Mountains, where the Savior will one day return.

Mormon fundamentalists, like mainstream LDS, are asked by God to consider themselves as Adam or Eve, a concept embedded in the endowment ceremony. They all serve a probationary period on earth until they may return to the presence of the Father. During this probation they must, like Adam, pursue “further light and knowledge” and seek messengers who can guide them in receiving the keys that can unlock the power of the priesthood and remove the veil that borders earthly life and the Celestial Kingdom.

For the apocalyptic fundamentalists, portents and signs abound and every symbol and text has sublime meaning. Many of these signs direct the millenarianist to go above and beyond orthodoxy and to strive to be among the truly blessed who live in the society of the Gods (Michael also known as Adam, Jesus, and Joseph) and embrace the “mysteries of the kingdom” (Doctrine and Covenants 63:23; 76:1–7). But not all can understand the mysteries; the truly righteous must have the “eyes to see and ears to hear” the truth about the fulness of the gospel. Many fundamentalists see their modern prophet (Jeffs, Allred, Kingston, and so on) as the source of divine revelation, but independents often claim that they themselves hold the “sacred secret” of direct man-to-God revelation (Doctrine and Covenants Commentary 1972:141). That is the lure of fundamentalism, that you can be your own prophet, seer, and king.

The “mysteries” include divine steps to test the validity of revelations and true prophets. One involves making the calling and election sure (Young 1867) so that the Chosen will have the right to converse with the dead beyond the veil and gain personal revelations from God. Another step is to humble yourself in the true order of prayer, a method that was used by Adam; those who follow this practice wear temple garments, kneel, and pray with upraised hands of praise and supplication, crying, “Oh God, hear the words of my mouth.” Just as Joseph Smith was given the divine ordinances and doctrines, so too can any man who seeks with the appropriate priesthood authority, who honors the covenants, and who hungers and thirsts for the knowledge. Saints who devote themselves to righteousness and receive higher ordinances of exaltation become members of the “church of the firstborn,” an inner circle of faithful saints who practice the fulness and who will be joint heirs with Christ in receiving all that the Father has (McConkie 1991:139–40). They will be sealed by “the holy spirit of promise,” will become kings and Gods in the making, and will take part in the first resurrection. This will enable them to live on Mt. Zion with God in the company of angels in the Celestial Kingdom (Doctrine and Covenants 76:50–70). Members of the firstborn may be asked to break the law of the land for the higher law, perhaps even commit murder, as Book of Mormon prophet Nephi was commanded to kill the evil one, Laban. It is through this process that “just men will be made perfect” and be given the gifts of kingdoms and principalities in new worlds beyond the limits of their imaginations.

Besides the “mysteries,” the most valued fundamentalist principles that were abandoned by the LDS Church are polygamy, the Adam-God doctrine, and the Law of Consecration. When these principles are intact, the order of heaven correlates four different gospel-oriented elements in a workable system: social, political, spiritual, and economic. The social element of the heavenly order is polygamy, the political element is the kingdom of God or the government of God, the spiritual element is the priesthood as the conduit for revelation, and the economic element is the United Order.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

The Apostolic United Brethren (AUB) have approximately 8,000 members throughout the world. Their official headquarters is in Bluffdale, Utah, where they have a chapel/cultural hall, an endowment house, a school, archives, and a sports field. Most of members live in medium-sized split-level homes and work in construction. The more successful own huge compounds in Eagle Mountain and Rocky Ridge accommodating four to five wives and twenty-five children. The church operates at least three private schools, but many families homeschool or send their children to public or public charter schools, blending with the mainstream. Other branches include Cedar City, Lehi, and Granite, Utah; Pinesdale, Montana; Lovell, Wyoming; Mesa, Arizona; Humansville, Missouri; and Ozumba, Mexico, where it has a temple with around 700 followers. More AUB members live in Germany, the Netherlands, and England.

As mentioned, Dr. Rulon C. Allred, a naturopath, became prophet in 1954, adopting polygamy while maintaining strong ties to the LDS Church, even though he was excommunicated. He did not see the fundamentalist effort as being above the church but parallel to it, feeling that not everyone could (or should) participate in polygamy.

By 1959, the AUB had grown to 1,000 members with the help of Joseph Lyman Jessop, Joseph Thompson, and other converts, who met covertly in the Bluffdale home of Owen Allred, Rulon’s brother. In 1960, Rulon Allred bought the 640 acres in Pinesdale, Montana for $42,500, and by 1973 more than 400 fundamentalists called it home. When I was there, from 1989 to 1993, there was a school/church complex, a library, a cattle operation, a machine shop, and the vestiges of a dairy operation. I counted approximately 60-70 married men (patriarchs) with around 140-150 wives (around 2.8 each, on average) and 720 children. The Jessops (Marvin and Morris) and their eldest sons were the leaders of Pinesdale, along with less powerful members of the priesthood council.

The AUB boasted of more converts than any other group. People were drawn to the promise of homesteading and kingdom building in a group with few restrictions. Plural ceremonies were performed by the priesthood council in homes, in the endowment house, in the church building, or even on a hillside or meadow. By 1970, the number of AUB members was close to 2,500 expanding to southern Utah and along the Wasatch Front.

Rulon Allred’s priesthood council included Rulon, Owen Allred, George Scott, Ormand Lavery, Marvin Jessop and his brother Morris Jessop, Lamoine Jensen, George Maycock, John Ray, and Bill Baird. Over the years, Rulon replaced members who died, who were excommunicated (as in the case of John Ray), or who apostatized. Rulon kept his two brothers, Owen and Marvin, close at hand, bestowing upon them favorable stewardships and granting them permission to marry several wives each. The AUB use LDS Church material in their sermons and for Sunday school lessons. Many of the offices and callings are the same. The AUB’s members also tend to integrate with surrounding Mormon communities, largely due to  Owen Allred’s desire to work with local law enforcement officials and end the practice of arranged marriages with underage girls. Allred [Image at right] believed that transparency was an important factor in his efforts to show the non-Mormon community that the AUB and its members were not a threat.

Owen Allred’s desire to work with local law enforcement officials and end the practice of arranged marriages with underage girls. Allred [Image at right] believed that transparency was an important factor in his efforts to show the non-Mormon community that the AUB and its members were not a threat.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

In 1977, Rulon was killed by a female assassin sent by Ervil LeBaron and his brother Owen took the helm. Owen led the group for twenty-eight years, a period when the AUB expanded its membership and entered into a time of collaboration with the press, academia, and the Utah attorney general’s office.

Accusations of child sexual abuse were made against three Allred councilmen over the space of two decades, 1975-1995: John Ray, Lynn Thompson, and Chevral Palacios. Yet, the rates of abuse are no greater than what you would expect to find in the mainstream monogamist communities of the United States. Members who perpetrate abuse are excommunicated, and victims are encouraged to report the incidents to the police. In addition, I suggest that the AUB is more progressive and law-abiding than other groups. Its members pay their taxes, seem to dress like everyone else for the most part, send their children to public school, and even have a Boy Scout troop. There are some flies in the AUB ointment, such as the ex-Allredite man who recently was arrested for raping twin sisters in Humansville, Missouri. There is also evidence of money laundering and some welfare fraud. According to one former member, attorney John Llewellyn, plural wives are sent into nearby Hamilton to apply for welfare as single mothers, and they take this money directly to the priesthood Brethren. In my own research in 1993, I heard of welfare misuse in twenty-five percent of my sample of fifteen extended families. They looked on it much the same way that the FLDS wives did, as “creative financing” that was taking from the federal government, a corrupt entity.

In 2004, the priesthood leadership was comprised of Owen Allred, Lamoine Jensen, Ron Allred, Dave Watson, Lynn Thompson, Shem Jessop, Harry Bonell, Sam Allred, Marvin Jessop, and Morris Jessop. In 2005, Owen Allred died at the age of ninety-one, after appointing Lamoine Jensen to be his successor, passing up more senior council members. In 2015, Lamoine died of intestinal cancer, which caused a major split in the group with some following Lynn Thompson and the others following Morris and Marvin Jessop.

Since 2016, a number of prominent AUB members in Pinesdale, MT separated themselves from the leadership of Lynn Thompson and formed their own group with their own meetings, calling themselves the “Second Ward.” Such dissenters include two from the AUB Priesthood Council, two Melchizedek Priesthood leaders, two bishops, the president of the all-female Relief Society, the Sunday school president, the elders quorum president, and the Seventies quorum president. Central to this schism between the Salt Lake AUB and the Pinesdale, Montana community was the accusations of sexual misconduct by Lynn Thompson against one of his daughters, Rosemary Williams, and shortly thereafter by two of his nieces. Thompson was also accused of embezzling tithing funds (Carlisle 2017). When Lynn Thompson died in 2021, he was replaced by David Watson (Carlisle 2017).

The year before Thompson’s death, the Utah legislature passed a bill to decriminalize polygamy in Utah. Those who favored the passage of the bill argued that the criminal status of polygamy directly contributed to a culture of distrust and isolation, and subsequently abuse. Decriminalization would serve to bring such abuses into the light for prosecution (Bennion and Joffe 2016). This law did not impact the Thompson case as his daughter declined to bring formal charges.

IMAGES

Image #1: Joseph Smith Jr.

Image #2: Lorin Woolley.

Image #3: Rulon Allred.

Image #4: Owen Allred.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Scott. 2010. “The Polygamists.” National Geographic, February: 34–61.

Bennion, Janet and Joffe, Lisa F. 2016. “Introduction.” Pp. 3-22 in The Polygamy Question. Boulder: University of Colorado Press.

Carlisle, Nate. 2017. “Sex abuse allegations have rocked the polygamous church of ‘Sister Wives,’ causing rift from Utah to Montana.” Salt Lake Tribune, October 21.

Driggs, Ken. 2005. “Imprisonment, Defiance, and Division: A History of Mormon Fundamentalism in the 1940s and 1950s.” Dialogue 38:65–95.

Driggs, Ken. 2001. “‘This Will Someday be the Head and Not the Tail of the Church’: A History of the Mormon Fundamentalists at Short Creek.” Journal of Church and State 43:49–80.

Gordon, Sarah. 2001. The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth Century America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Hales, Brian. 2006. Modern Polygamy and Mormon Fundamentalism: The Generations After the Manifesto. Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books.

Kraut, Ogden. 1989. The Fundamentalist Mormon. Salt Lake City: Pioneer Press.

McConkie, Bruce R. 1991. Mormon Doctrine. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. [Encyclopedic work originally written in 1958; not an official publication of the LDS Church.], 139-40

Musser, Joseph, and L. Broadbent. 1934. Supplement to the New and Everlasting Covenant of Marriage. Pamphlet. Salt Lake City: Truth Publishing Company.

Quinn, D. Michael. 1993. “Plural Marriage and Mormon Fundamentalism.” Pp. 240-66 in Fundamentalisms and Society, edited by Martin Marty and R. Scott Appleby. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Richards, Stephen. 1932. Sermon delivered at April 1932 LDS general conference, also quoted in the Salt Lake Tribune, April 10, 1932.

Smith, Joseph Fielding. [1838] 2006. Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith. Compiled and edited by Joseph Fielding Smith. Salt Lake City: Deseret Books.

Young, Brigham.1867. Journal of Discourses 12:103; 7:290, November. Liverpool: LDS Church.

Young, Kimball. 1954. “Sex Roles in Polygamous Mormon Families.” Pp. 373-93 in Readings in Psychology, edited by Theodore Newcomb and Eugene Hartley. New York: Holt.

Publication Date:

27 May 2019