ISKCON TIMELINE

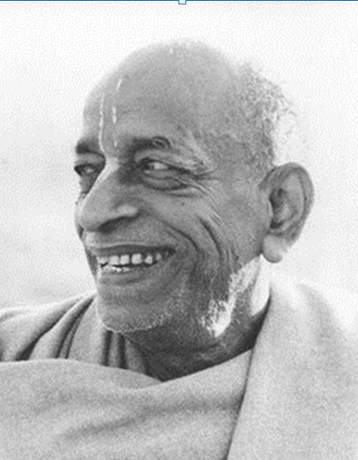

1896: International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) founder Swami A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada was born as Abhay Charan De, in Calcutta, India.

1932: Prabhupada took initiation from his guru Bhaktisiddhanta, becoming a disciple of Krishna.

1936: Bhaktisiddhanta charged Prabhupada with spreading Krishna consciousness in the West.

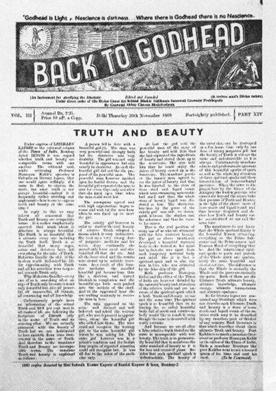

1944: Prabhupada began publishing Back to Godhead, an English-language publication.

1959: Prabhupada took sanyasa order, becoming a monk and dedicating himself full time to spreading Krishna Consciousness.

1965: Prabhupada traveled to America.

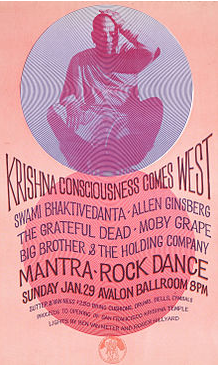

1966: ISKCON was founded in New York City; Prabhupada initiated his first disciples; ISKCON became part of hippie counterculture.

1966-1968: ISKCON spread to other major North American cities (San Francisco, Boston, Toronto, and Los Angeles) and globally (India, England, Germany, and France).

1968: ISKCON members founded New Vrindaban, a rural commune in West Virginia that later became a source of conflict.

1968-1969: Prabhupada met with members of The Beatles; George Harrison became a disciple; the Hare Krishna movement became part of transatlantic musical and artistic landscape.

1970: The ISKCON Governing Board Commission (GBC) and Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT) were established.

1977: Prabhupada died.

1977-1987: A series of succession conflicts resulted in schisms and a significant loss of membership.

1984-1987: A reform movement emerged within ISKCON.

1985-1987: The New Vrindaban community separated from ISKCON; criminal charges were filed against its leaders.

1987: GBC endorses position of Reform movement

1991: The ISKCON Foundation was created to build bridges with Hindu immigrants to America.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

The story of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), popularly known as the Hare Krishna movement,  tightly interweaves with the story of its founder, the religious teacher (swami ) A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada. Born Abhay Charan De, in Calcutta, India, the future founder of ISKCON witnessed firsthand the modernization of India and the effects of British colonial rule. His autobiographic reflections and official hagiography reveal that he was both enamored of the tremendous social, cultural, and technological change occurring around him as well as attracted to the traditional mores of his family, faith, and culture (Zeller 2012:73-81). According to his biography, Abhay grew up across the street from a Vaishnava temple, a Hindu sect dedicated to the worship of Krishna. The Chaitanya (Gaudya) Vaishnava branch of Hinduism practiced at the temple, which would later become the form that Abhay Charan De accepted and of which he become the greatest proponent, is a monotheistic type of Hinduism. It envisions Krishna as the supreme form of God who creates and maintains the cosmos, and who is both personal and universal God (Goswami 1980).

tightly interweaves with the story of its founder, the religious teacher (swami ) A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada. Born Abhay Charan De, in Calcutta, India, the future founder of ISKCON witnessed firsthand the modernization of India and the effects of British colonial rule. His autobiographic reflections and official hagiography reveal that he was both enamored of the tremendous social, cultural, and technological change occurring around him as well as attracted to the traditional mores of his family, faith, and culture (Zeller 2012:73-81). According to his biography, Abhay grew up across the street from a Vaishnava temple, a Hindu sect dedicated to the worship of Krishna. The Chaitanya (Gaudya) Vaishnava branch of Hinduism practiced at the temple, which would later become the form that Abhay Charan De accepted and of which he become the greatest proponent, is a monotheistic type of Hinduism. It envisions Krishna as the supreme form of God who creates and maintains the cosmos, and who is both personal and universal God (Goswami 1980).

As a child of high caste middle class parents, Abhay attended a British colonial school and college, earned a Bachelors degree, and became a chemist working for a pharmaceutical company. He married and had children, all the while continuing his personal religious devotions. In 1922, he met a swami in the Chaitanya Vaishnava lineage named Bhaktisiddhanta, and ten years later he took initiation from Bhaktisiddhanta and became a disciple. Abhay was later granted the honorific Bhaktivedanta on account of his religious erudition and dedication. Bhaktisiddhanta charged his colonially educated disciple with spreading Krishna consciousness among English-speakers (Knott 1986:26-31).

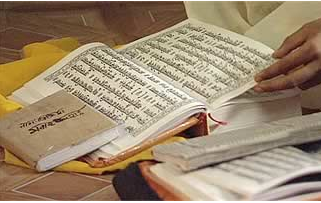

Bhaktivedanta did just this, at first part time as a householder through public speeches and a new English-language newspaper he founded in 1944, Back to Godhead . After arriving in America over two decades later, Bhaktivedanta would restart Back to Godhead, which eventually became the official organ of ISKCON, its major publication, and the literary means by which the movement propagated itself. Bhaktivedanta also began translating sacred Vaishnava scriptures into English, notably the Bhagavadgita and Bhagavata Purana.

founded in 1944, Back to Godhead . After arriving in America over two decades later, Bhaktivedanta would restart Back to Godhead, which eventually became the official organ of ISKCON, its major publication, and the literary means by which the movement propagated itself. Bhaktivedanta also began translating sacred Vaishnava scriptures into English, notably the Bhagavadgita and Bhagavata Purana.

In keeping with Hindu religious norms and Indian social norms, in 1959 Bhaktivedanta took the religious order of sanyasa, becoming a monastic and leaving behind his familial obligations. He then dedicated himself to the fulltime religious propagation of Krishna consciousness and laid the groundwork for his travel to the English speaking West. He did so in 1965, arriving in Boston and then founding a religious ministry in the bohemian areas of Manhattan. Finding limited interest among the middle class, Bhaktivedanta discovered that his religious message primarily appealed to members of the counterculture who had rejected middle class American social, cultural, and religious norms (Rochford 1985). Bhaktivedanta rededicated himself to outreach to this segment of the population. His disciples took to calling him Prabhupada, an honorific that Bhaktisiddhanta had also used.

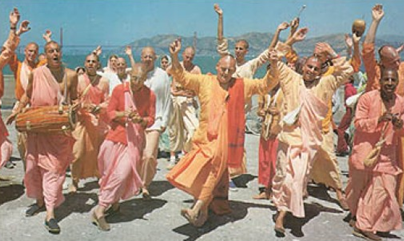

Prabhupada founded ISKCON in New York City in 1966. Within months his own disciples and converts began to spread Krishna Consciousness throughout the American hippie counterculture, first to San Francisco and then to other major North American cities. Within two years of founding ISKCON, Prabhupada and his disciples had planted temples throughout North America and Europe, making inroads in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Canada, as well as  establishing an outreach in India itself. ISKCON members also established a series of rural communes, the best known of which was New Vrindaban, in West Virginia. Most members were full-time disciples, dedicating themselves to propagating Krishna Consciousness and living in the temples and communes. Some began to marry, and Prabhupada blessed their marriages. A divide between married householders and fulltime monastic members would eventually cause tensions within the movement. During this time ISKCON also made inroads among the creative class, with George Harrison and John Lennon of The Beatles becoming enamored of the Hare Krishnas and their philosophy. ISKCON had become a recognized part of the transatlantic youth counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Knott 1986).

establishing an outreach in India itself. ISKCON members also established a series of rural communes, the best known of which was New Vrindaban, in West Virginia. Most members were full-time disciples, dedicating themselves to propagating Krishna Consciousness and living in the temples and communes. Some began to marry, and Prabhupada blessed their marriages. A divide between married householders and fulltime monastic members would eventually cause tensions within the movement. During this time ISKCON also made inroads among the creative class, with George Harrison and John Lennon of The Beatles becoming enamored of the Hare Krishnas and their philosophy. ISKCON had become a recognized part of the transatlantic youth counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Knott 1986).

In the 1970s, Prabhupada laid the groundwork for the institutionalization of his charismatic leadership. He founded the Governing Board Commission (GBC) and Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (BBT), two legal entities that were charged respectively with managing the movement and literary output of the founder. In the remaining seven years before his death, Prabhupada granted increasingly more authority to the GBC and BBT, though as founder and undisputed leader of ISKCON he routinely acted independently of the institution and even directed them on occasion. Though Prabhupada attempted to groom members of the GBC and BBT to manage the movement, few of its members had any administrative experience and most had been countercultural hippies only years earlier. A conflicting set of instructions regarding religious, as opposed to bureaucratic, authority sowed the seeds of later discord after Prabhpada’s death (see below, Issues/Challenges).

The decade after Swami A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada’s death in 1977 was characterized by a series of succession conflicts. Competing forces within ISKCON envisioned alternative directions for the movement, and many of the leaders were incapable of assuming the mantle Prabhupada had left. Many members of ISKCON’S GBC sought to refocus on the monastic strand within the tradition, disparaging and often ignoring the increasingly numerically significant householders. Financial problems led some members of the movement to approve of unethical and even illegal fund raising strategies, and several of the religious gurus became involved in sexual or drug-related scandals. It was a dark period for many members of ISKCON, and the movement shed over half of its adherents in the two decades that followed (Rochford 1985:221-55; Rochford 2007:1-16).

The debacle at New Vrindaban ( explored below, under Issues/Challenges ), a series of conflicts over religious gurus, poor leadership by the GBC, accusations of child abuse in the ISKCON schools, and several well publicized falls from grace by Prabhupada’s hand-picked successors resulted in a decade of numerical decline and soul searching by members of the Hare Krishna movement. A reform movement began to emerge within ISKCON during the mid-1980s calling for better oversight, clearer ethical standards for the leaders, and increased participation of householders and women in the leadership of ISKCON. In 1987, the GBC endorsed most of the proposals of ISKCON reform movement, among them abolishing the “zonal acharya system” that had created regional fiefdoms wherein individual gurus functioned as sole religious leaders without oversight (Deadwyler 2004).

In recent decades, ISKCON has stabilized under the leadership of a more professional and broader based GBC, as well as individual temples that have empowered laypeople, householders, and families rather than solely relying on monastic elites. Some of the current issues facing the Hare Krishna movement in the twenty-first century are the relation of ISKCON to broader Hinduism and the Indian diasporic community and the acculturation and education of second and third generation members.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The Hare Krishna movement must be understood as a form of the Chaitanya (Gaudya) school of Vaishnavism, a monotheistic  branch of Hinduism tracing its origin to the sixteenth century reforms of the religious guru Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486-1533). As a Vaishnava tradition, IKSCON falls within the largest of the three major schools of Hinduism, focusing on the veneration of Vishnu as supreme God. (The other major schools are Shaivism, worshipping Shiva, and Shaktism, venerating Shakti, the divine mother.) Hinduism is a quite diverse tradition, and because the notion of Hinduism as a unified religion is quite new and in many ways foreign to actual Hindu self-understandings (the term was first imposed on Hindus by Muslims and then Christians) one can make relatively few generalizations about the tradition as a whole. Hindus accept the doctrines of karma and reincarnation, the notion of unified cosmic law (dharma), beliefs in vast cosmic cycles of creation and destruction, and hold that there are multiple goals within life that culminate in the quest for self-understanding and spiritual freedom (moksha). Importantly, Hindus believe that the gods incarnate in physical form as avatars in order to accomplish divine work on Earth. Foremost are the avatars of Vishnu, notably Krishna and Rama as described in the Hindu epics of the Mahabharata, of which the Bhagavadgita is a part, the Ramayana, and the devotional text of the Bhagavata Purana. Hindus also hold as central the ideal of the guru, the spiritual master who takes disciples and teaches them how to seek spiritual self-fulfillment and salvation. All of these basic Hindu beliefs carry over into Vaishnavism, the Chaitanya school, and ISKCON specifically (Frazier 2011).

branch of Hinduism tracing its origin to the sixteenth century reforms of the religious guru Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486-1533). As a Vaishnava tradition, IKSCON falls within the largest of the three major schools of Hinduism, focusing on the veneration of Vishnu as supreme God. (The other major schools are Shaivism, worshipping Shiva, and Shaktism, venerating Shakti, the divine mother.) Hinduism is a quite diverse tradition, and because the notion of Hinduism as a unified religion is quite new and in many ways foreign to actual Hindu self-understandings (the term was first imposed on Hindus by Muslims and then Christians) one can make relatively few generalizations about the tradition as a whole. Hindus accept the doctrines of karma and reincarnation, the notion of unified cosmic law (dharma), beliefs in vast cosmic cycles of creation and destruction, and hold that there are multiple goals within life that culminate in the quest for self-understanding and spiritual freedom (moksha). Importantly, Hindus believe that the gods incarnate in physical form as avatars in order to accomplish divine work on Earth. Foremost are the avatars of Vishnu, notably Krishna and Rama as described in the Hindu epics of the Mahabharata, of which the Bhagavadgita is a part, the Ramayana, and the devotional text of the Bhagavata Purana. Hindus also hold as central the ideal of the guru, the spiritual master who takes disciples and teaches them how to seek spiritual self-fulfillment and salvation. All of these basic Hindu beliefs carry over into Vaishnavism, the Chaitanya school, and ISKCON specifically (Frazier 2011).

The Chaitanya school is part of the bhakti or devotional path of Hinduism, a path that cuts across the different schools of Hindu practice and has long been one of the most popular forms of Hindu practice. Bhakti practitioners center their religious lives on the ideal of devotion to their chosen God, serving the divine through worship, prayer, song, social service, and study. Members of bhakti groups who become initiated as formal devotees often vow to perform specific means of devotion, including set numbers of prayers or forms of worship. In the case of ISKCON, initiated devotees also take new Vaishnava names referring to their divine service.

The Hare Krishna movement and other branches of the Chaitanya tradition depart from most other forms of Hinduism in terms of understanding Krishna as the true nature of the divine, or the supreme personality of Godhead (to use the language most often heard within the movement itself). This reverses the more common belief held by most Hindus that Krishna was one among several avatars or appearances of Vishnu. As Indologist and expert on the Vaishnava tradition Graham Schweig explains, “the Chaitanyaites consider Krishna as the ultimate transcendent Lord at the very center of the godhead from whom the majestic and powerful cosmic Vishnu emanates. Krishna is known as the purnavatara, ‘full descent of the deity’” (Schweig 2004:17). In other words, members of the Hare Krishna movement look to Krishna as the true and absolute nature of the divine as well as the specific appearance of the divine who took form in ancient India as an avatar. Adherents of the Chaitanya school also distinguish themselves from other Hindus by regarding the founder himself, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as an incarnation of Krishna.

understanding Krishna as the true nature of the divine, or the supreme personality of Godhead (to use the language most often heard within the movement itself). This reverses the more common belief held by most Hindus that Krishna was one among several avatars or appearances of Vishnu. As Indologist and expert on the Vaishnava tradition Graham Schweig explains, “the Chaitanyaites consider Krishna as the ultimate transcendent Lord at the very center of the godhead from whom the majestic and powerful cosmic Vishnu emanates. Krishna is known as the purnavatara, ‘full descent of the deity’” (Schweig 2004:17). In other words, members of the Hare Krishna movement look to Krishna as the true and absolute nature of the divine as well as the specific appearance of the divine who took form in ancient India as an avatar. Adherents of the Chaitanya school also distinguish themselves from other Hindus by regarding the founder himself, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as an incarnation of Krishna.

ISKCON devotees are monotheistic, believing that the other divinities of Hinduism are mere demigods in service of Krishna, and they worship Krishna in the various forms that he takes. Yet ISKCON theology also recognizes that Krishna exists in a binary pairing of Radha-Krishna, where Radha is the female consort and lover of the male Krishna, the cowgirl ( gopi ) who symbolizes the devotee himself or herself in seeking intimate connection to the divine. Devotees venerate other avatars, associates, and saintly devotees of Krishna, such as Rama, Balaram, Chaitanya, and the sacred basil plant ( tulasi ) that adherents believe is an Earthly incarnation of one of Krishna’s associates on the spiritual realm.

One of the most important aspects of ISKCON beliefs is the centrality of the idea of the Vedas, Vedic knowledge, and Vedism.  Prabhupada and others referred to the tradition as a “Vedic science” and envisioned the Society as propagating Vedic norms in the modern world. The Vedas are the ancient sacred texts of India, the origin, dating, and province of which are hotly contested by scholars, practitioners, and even politicians. Like other Hindus, devotees believe that the Vedas are the essence of dharma : timeless truths recorded by ancient sages and indicating the basic truths and underlying law of the universe, the structuring of society, the purpose of living, and the nature of the divine (Frazier 2011). ISKCON takes a broad view of the Vedic corpus as including the Puranas, Bhagavadgita, and other later sources, since they perceive these texts as part of the same religious and textual tradition as the earliest Vedic sources.

Prabhupada and others referred to the tradition as a “Vedic science” and envisioned the Society as propagating Vedic norms in the modern world. The Vedas are the ancient sacred texts of India, the origin, dating, and province of which are hotly contested by scholars, practitioners, and even politicians. Like other Hindus, devotees believe that the Vedas are the essence of dharma : timeless truths recorded by ancient sages and indicating the basic truths and underlying law of the universe, the structuring of society, the purpose of living, and the nature of the divine (Frazier 2011). ISKCON takes a broad view of the Vedic corpus as including the Puranas, Bhagavadgita, and other later sources, since they perceive these texts as part of the same religious and textual tradition as the earliest Vedic sources.

Prabhupada and his earliest disciples positioned ISKCON as Vedic and in opposition to what they saw as decadent and materialistic Western (non-Vedic) culture, capturing much of the spirit of the counterculture and fusing it with Prabhupada’s anti-imperialist Indian perspective. Some elements of contemporary ISKCON retain this highly twofold manner of envisioning society as Vedic (good) vs. non-Vedic (bad), but other members of ISKCON have synthesized the ideal of living in accordance with the Vedas within life in the contemporary West.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

The central ritual of ISKCON is that of chanting the name of God in the form of the mahamantra (great mantra): Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Rama Rama, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. This mahamantra not only gave the movement its unofficial but most common name but also links ISKCON back to the theological developments of Chaitanya, who predicted predicated his sixteenth century reforms on chanting, as well as Bhaktisiddhanta, who emphasized chanting as well. Chaitanya, Bhaktisiddhanta, and Prabhupada all emphasized that chanting was not only supremely pleasing to God and spiritually efficacious but also easy to do, universally available, and fit for contemporary times. Initiated members of ISKCON vow to chant sixteen rounds of the Hare Krishna mahamantra each day, where each round includes 108 repititions repetitions of the mantra. Some devotees do this in temples, others at home shrines, and still others in gardens, parks, workplaces, or during daily commutes. Chanting, along with following the regulative principles (no illicit sex, intoxicants, meat eating, or gambling) serve as the heart of religious practice in Krishna Consciousness (Bhaktivedanta 1977).

Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Rama Rama, Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. This mahamantra not only gave the movement its unofficial but most common name but also links ISKCON back to the theological developments of Chaitanya, who predicted predicated his sixteenth century reforms on chanting, as well as Bhaktisiddhanta, who emphasized chanting as well. Chaitanya, Bhaktisiddhanta, and Prabhupada all emphasized that chanting was not only supremely pleasing to God and spiritually efficacious but also easy to do, universally available, and fit for contemporary times. Initiated members of ISKCON vow to chant sixteen rounds of the Hare Krishna mahamantra each day, where each round includes 108 repititions repetitions of the mantra. Some devotees do this in temples, others at home shrines, and still others in gardens, parks, workplaces, or during daily commutes. Chanting, along with following the regulative principles (no illicit sex, intoxicants, meat eating, or gambling) serve as the heart of religious practice in Krishna Consciousness (Bhaktivedanta 1977).

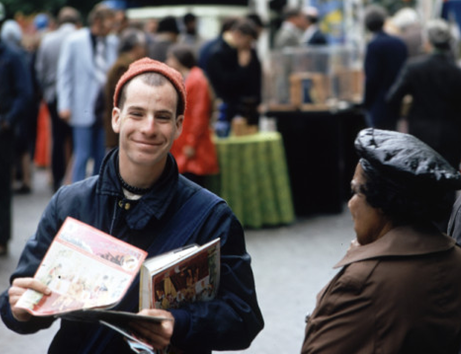

Prabhupada also emphasized book distribution, and the donation or selling of literature remains one of the most a common forms of religious practice in ISKCON outside of chanting. In the early days of the movement ISKCON devotees made a name for themselves selling books, magazines, and pamphlets in streets, parks, and, most famously, airports. The movement was lampooned for these practices in such American popular culture fixtures as Airplane! and The Muppet Movie. A series of court cases in the 1980 limited the ability to engage in book distribution in public places. With the aging of the movement, public activities such as book distribution, chanting, and preaching (collectively called sankirtana ) have become less common.

of religious practice in ISKCON outside of chanting. In the early days of the movement ISKCON devotees made a name for themselves selling books, magazines, and pamphlets in streets, parks, and, most famously, airports. The movement was lampooned for these practices in such American popular culture fixtures as Airplane! and The Muppet Movie. A series of court cases in the 1980 limited the ability to engage in book distribution in public places. With the aging of the movement, public activities such as book distribution, chanting, and preaching (collectively called sankirtana ) have become less common.

Increasingly, ISKCON members look to their religious involvement as centered on weekly attendance at the temple and performing deity worship there. While temple worship certainly extends to the earliest days of the movement, the advent of congregational membership and the demographic shifts that have made congregational membership the norm has led to weekly temple attendance becoming central. In the United States, where Protestant norms have shaped the  environment, ISKCON temples hold weekly worship on Sundays. During deity worship at temples, Hare Krishna devotees engage in a ritualized form of devotion (bhakti ), including service to Krishna (puja ), and viewing of Krishna (darshan). ISKCON follows standard Vaishnava and broader Hindu worship norms with some minor additions, such as salutations to ISKCON’s founder Swami A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada through chants and spoken prayers.

environment, ISKCON temples hold weekly worship on Sundays. During deity worship at temples, Hare Krishna devotees engage in a ritualized form of devotion (bhakti ), including service to Krishna (puja ), and viewing of Krishna (darshan). ISKCON follows standard Vaishnava and broader Hindu worship norms with some minor additions, such as salutations to ISKCON’s founder Swami A.C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupada through chants and spoken prayers.

Temple worship normally ends in a communal meal, and such meals, “feasts,” as ISKCON advertisements have called them since 1965, often attract a diverse range of attendees. Certainly the majority of those eating at the ISKCON feasts are worshipers who took part in temple services, but the Hare Krishna movement uses its feasts as an outreach effort, and in many cases spiritual seekers, hungry college students, and simply the curious attend as well. The food served is spiritual food (prasadam) that has been offered to Krishna, and adherents believe that preparing, distributing, and eating it are spiritual acts. Outside of temples, Krishna devotees offer prasadam in venues ranging from public parks to college campuses to city streets. Adherents look to the distribution of such spiritual food as not just a religious act but also a form of evangelism as well as social welfare and feeding the hungry (Zeller 2012).

ISKCON’s religious calendar is filled with holidays ranging from weekly partial fasts to monthly lunar ceremonies to major yearly  festivals. Such festivals commemorate the activities of Krishna, his closest disciples, and the major leaders of ISKCON’s lineage, such as the birth and death of Chaitanya and Prabhupada. ISKCON adherents also celebrate all the major Hindu holidays such as Holi, Navaratri, and Divali, but they do so in ways highlighting Krishna rather than other Hindu deities. The celebration of holidays explicitly centering on other Gods, such as Shivaratri, are contentious issues within individual ISKCON communities. Many Western-born devotees are uninterested in venerating what they consider demigods, and many Indian-born devotees seek to participate in valued parts of their religious-cultural tradition.

festivals. Such festivals commemorate the activities of Krishna, his closest disciples, and the major leaders of ISKCON’s lineage, such as the birth and death of Chaitanya and Prabhupada. ISKCON adherents also celebrate all the major Hindu holidays such as Holi, Navaratri, and Divali, but they do so in ways highlighting Krishna rather than other Hindu deities. The celebration of holidays explicitly centering on other Gods, such as Shivaratri, are contentious issues within individual ISKCON communities. Many Western-born devotees are uninterested in venerating what they consider demigods, and many Indian-born devotees seek to participate in valued parts of their religious-cultural tradition.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Today ISKCON’s organization is both centralized and diffuse. It is centralized in terms of the authority of the GBC, the sole institution granted the legitimacy and authority over the religious affairs of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. The GBC determines how funds are collected and used, which gurus will travel to what areas of the world, where to focus evangelism efforts, and how to respond to challenges and problems as they occur. The GBC has the authority to make liturgical changes as well, for example limiting the veneration of gurus to Prahbuphada alone. Along with the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, which publishes the liturgical, educational, and intellectual materials of the movement, the GBC is the embodiment of the institutionalized charisma of ISKCON’s leader and founder Prabhupada.

Yet throughout the world the local ISKCON temples and communities have a great deal of latitude in terms of how they run their  own affairs. Individuals and small groups of devotees have sponsored the building of new temples, renovations of older ones, and the planting of new communities meeting in individual houses or rented spaces. Local leaders oversee worship, social activities, and educational services at the temples, and they generally do so with attention to the local needs of their communities. While the actual deity service, texts, and doctrines are shared across all ISKCON communities, great diversity exists in terms of the mood and social functions of the temples. Some temples cater primarily to families and congregational members, others appeal to spiritual seekers or young students. Some temples engage in extensive outreach and evangelism, others are vibrant hubs of social and cultural activities, and others function more like worship halls that are utilized only during weekly temple worship.

own affairs. Individuals and small groups of devotees have sponsored the building of new temples, renovations of older ones, and the planting of new communities meeting in individual houses or rented spaces. Local leaders oversee worship, social activities, and educational services at the temples, and they generally do so with attention to the local needs of their communities. While the actual deity service, texts, and doctrines are shared across all ISKCON communities, great diversity exists in terms of the mood and social functions of the temples. Some temples cater primarily to families and congregational members, others appeal to spiritual seekers or young students. Some temples engage in extensive outreach and evangelism, others are vibrant hubs of social and cultural activities, and others function more like worship halls that are utilized only during weekly temple worship.

ISKCON’s gurus serve as the intermediary leaders between the GBC and the temples. Though initially only Prabhupada served as guru, shortly after his death the pool of gurus expanded exponentially and not without conflict, as noted below (“Issues/Challenges”). Gurus serve as the spiritual elite within ISKCON, initiating new members, blessing and performing weddings, and giving instruction. All are sanctioned by the GBC and act in accordance with its wishes. There is disagreement on the actual number of gurus, with Rochford reporting “more than 80” by 2005 (2007:14), Squarcini and Fizzori seeing eighty in 1993 and seventy in 2001 (2004:26, 80, note 99), and William H. Deadwyler reporting fifty in 2004 (Deadwyler 2004:168). Regardless, enough gurus serve ISKCON that religious power is both centralized within this group but decentralized outside of any one individual or small group. Until recently, all the gurus are were sanyasis, male celibate monks who have dedicated their lives exclusively to Krishna and spreading Krishna Consciousness. Quite recently householder men and women have joined the ranks of gurus as well.

At the base of the movement most ISKCON devotees are congregational members, meaning individuals not living in the movement’s temples. Some formally belong to the International Society for Krishna Consciousness as they have taken initiation into the worship of Krishna from one of the movement’s gurus. Others are uninitiated members, those who attend worship and engage in some forms of worship and service but have not been initiated. Today, many congregational members are married. Many of these congregational members (and most members in some North American and British temples) are Indian born Hindus who worship in ISKCON temples but were not members of ISKCON before immigrating to the West. This shift towards participation of householders as congregational members is one of the more remarkable shifts in ISKCON over the years. Sociologist E. Burke Rochford, Jr. has indicated that in 1980, fifty-three percent of the devotees he surveyed had never been married and seventy-three percent had no children. By 1991/1992, only fifteen percent had never been married and only thirty percent had no children (1985:62). Fedrico Squarcini and Eugenio Fizzotti estimate a similar 7:3 ration of householders to celibates among American ISKCON communities (2004:29).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Like many other new religious movements, ISKCON has faced its share of challenges. Many of these trace to problems arising after the death of the charismatic founder, and others are traced to demographic and social shifts within the movement.

The death of Prabhupada proved the most challenging issue for ISKCON in its brief history as a movement. A highly charismatic leader with appeal that was able to reach a diverse audience, the founder left impossibly large shoes to fill, an apt metaphor since images of Prabhupda’s footprints are a common devotional object in ISKCON temples. The conflict over post-charismatic leadership is therefore central to understanding the development of the Hare Krishna movement over the past thirty years.

A complete analysis of the succession of post-charismatic leadership in ISKCON has yet to be written, though several shorter analyses exist (Rochford 2009; Deadwyler 2004). During his life, Prabhupada served as not just founder and organizational leader, but the only guru and initiating master of the movement. Towards the end of his life he appointed intermediary priests serving on his behalf (ritviks) to initiate disciples. Following his death these ritviks declared themselves gurus, the “zonal acharyas,” each leading a geographic region of the world as sole guru. Prabhupada had also empowered the GBC (on which the gurus served, but not in a majority role) the BBT, and other institutions to guide and lead the movement. Many of the gurus proved themselves unable to lead, either corrupt, inept, or both. The gurus and the GBC came into increasing conflict, until eventually the GBC abolished the zonal acharya system and re-exerted itself as the highest authority of the movement. The GBC also expanded the number of gurus so as to limit their individual authority and focus on Krishna Consciousness itself rather than the messenger.

Certainly the darkest episode in the history of ISKCON involves one such failed guru, and centers on the movement’s agrarian  commune, the New Vrindavan community outside Moundsville, West Virginia. Originally intended to serve as a utopian ideal community to demonstrate ISKCON’s religious, social, and cultural teachings, New Vrindavan’s leadership had slowly drifted away from the thinking and direction of the rest of the movement, culminating in the expulsion of the community from ISKCON in 1988. Its leader, an early disciple of Prabhupada with the religious name of Bhaktipada, sought to introduce interreligious and explicitly Christian elements into their religious practice, as well as elevate his local leadership as equal to Prabhupada and above the authority of the GBC. Later, several prominent members of the community were accused of participation in various criminal activities and cover-ups, including child abuse, drug running, weapons trafficking, and eventually murder. Bhaktipada was found guilty of federal racketeering charges and sentenced to prison. Excommunicated from ISKCON, he died in 2011. After his removal from power, the community was slowly brought back into the ISKCON fold (Rochford and Bailey 2006).

commune, the New Vrindavan community outside Moundsville, West Virginia. Originally intended to serve as a utopian ideal community to demonstrate ISKCON’s religious, social, and cultural teachings, New Vrindavan’s leadership had slowly drifted away from the thinking and direction of the rest of the movement, culminating in the expulsion of the community from ISKCON in 1988. Its leader, an early disciple of Prabhupada with the religious name of Bhaktipada, sought to introduce interreligious and explicitly Christian elements into their religious practice, as well as elevate his local leadership as equal to Prabhupada and above the authority of the GBC. Later, several prominent members of the community were accused of participation in various criminal activities and cover-ups, including child abuse, drug running, weapons trafficking, and eventually murder. Bhaktipada was found guilty of federal racketeering charges and sentenced to prison. Excommunicated from ISKCON, he died in 2011. After his removal from power, the community was slowly brought back into the ISKCON fold (Rochford and Bailey 2006).

Despite this challenges and open conflicts remain regarding the issue of leadership. The majority of ISKCON’s members left the movement during the leadership transitions, but some of these have formed alternative Vaishnava communities equally devoted to Krishna Consciousness but not a formal part of ISKCON. This broader Hare Krishna milieu also includes schismatic movements led by gurus who left or were thrown out of ISKCON, as well as those inspired by Prabhupada’s godbrothers (fellow disciples of Prabhupada’s guru Bhaktisiddhanta). Another group has returned to the idea of the ritviks, breaking with Hindu tradition by refusing to accept the continuation of the lineage of living gurus. This sub-movement looks to ritviks as continuing to act as Prabhupada’s emissaries, and hold Prabhupada as a guru accepting new disciples even after his death.

Connected to the notion of changing leadership, the full and inclusive involvement of non-celibate males has been a major challenge to ISKCON. Prabhupada took a extremely conservative view of gender and family, limiting leadership positions to men and counseling women on the whole to look to religious fulfillment through submission to male leaders or as mothers. Women who joined found this approach attractive and even freeing (Palmer 1994), though with time many female devotees challenged their exclusion from leadership, teaching, and oversight positions (Lorenz 2004). Non-celibate householder men similarly found themselves devalued within ISKCON, which generally had valued celibacy and monasticism as the religious ideal (Rochford 2007).

The centrality of celibate men in leadership roles and a generally negative view of women, children, householder men ( that is, families ) resulted in the creation of the gurukula system, a sort of religious boarding school for the children born into Krishna Consciousness. The celibate leaders intended the system to help prevent over-attachment of children to their parents and allow them to focus on Krishna bhakti, and the gurukulas also freed parents to focus on service to the Society rather than child raising. Yet the gurukulas generally failed their students, who have reported profoundly negative experiences. Several prominent cases of mistreatment, criminal neglect, and even child abuse led to a series of court cases and the eventual shuttering of many of the gurukula s and a reformation of the few that remained (Deadwyler 2004) .

Slowly, ISKCON has made room for greater involvement of women and householder men. Rochford traces this development to labor shortages within ISKCON and the need to use the volunteer talents of women (2007:132-33). In 1998, a woman was chosen to serve on the GBC, and several women have became temple presidents (Rochford 2007:136). Simultaneously, ISKCON leaders have reached out to the South Asian community and welcomed its non-initiated congregational householders as members of the movement. Such involvement has provided financial stability and greater legitimacy to the movement, which increasingly identifies itself with Hinduism as a way to disassociate itself from the notion of ISKCON as a new religious movement or cult. This denominationalization of ISKCON represents the future of the movement as diasporic South Asians become the numerical majority of the movement and ISKCON increasingly associates itself with the Indian diaspora and more normative Hinduism. It remains to be seen what elements of ISKCON’s first generation, so marked by the American counterculture, will remain within this still-transforming religious movement.

REFERENCES

Bhaktivedanta, Swami A.C. Prabhupada. 1977. The Science of Self-Realization. Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Bryant, Edwin, and Maria Ekstrand, eds. 2004. The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deadwyler, William H. 2004. “Cleaning House and Cleaning Hearts: Reform and Renewal in ISKCON.” Pp. 149-69 in The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant, edited by Edwin Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press.

Frazier, Jessica. 2011. The Continuum Companion to Hindu Studies. London: Bloomsbury

Goswami, Satsvarupa Dasa. 1980. A Lifetime in Preparation: India 1896-1965: A Biography of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Los Angeles: Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.

Judah, J. Stillson. 1974. Hare Krishna and the Counterculture. New York: Wiley.

Knott, Kim. 1986. My Sweet Lord: The Hare Krishna Movement. Wellingborough, U.K.: Aquarian.

Lorenz, Ekkehard. 2004. “The Guru, Mayavadins, and Women: Tracing the Origins of Selected Polemical Statements in the Works of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.” Pp. 112-28 in The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant, edited by Edwin Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press.

Palmer, Susan J. 1994. Moon Sisters, Krishna Mothers, Rajneesh Lovers: Women’s Roles on New Religions. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Rochford, E. Burke, Jr. 2009. “Succession, Religious Switching, and Schism in the Hare Krishna Movement.” Pp. 265-86 in Sacred Schisms: How Religions Divide, edited by James R. Lewis and Sarah M Lewis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rochford, E. Burke, Jr. 2007. Hare Krishna Transformed. New York: New York University Press.

Rochford, E. Burke, Jr. 1985. Hare Krishna in America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Schweig, Graham M. 2004. “Krishna, the Intimate Deity.” Pp. 13-30 in The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant, edited by Edwin Bryant and Maria Ekstrand. New York: Columbia University Press.

Squarcini, Federico, and Eugenio Fizzotti. 2004. Hare Krishna. Salt Lake City: Signature Books.

Zeller, Benjamin E. 2012. “Food Practices, Culture, and Social Dynamics in the Hare Krishna Movement.” Pp. 681-702 in Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production, edited by Carole M. Cusack and Alex Norman. Leiden: Brill.

Zeller, Benjamin E. 2010. Prophets and Protons: New Religious Movements and Science in Late-Twentieth Century America. New York: New York University Press.

Publication Date:

27 August 2013