KATHERINE TINGLEY TIMELINE

1847 (July 6): Katherine Tingley was born Catherine Augusta Westcott in Newbury, Massachusetts.

1850s: As a child Tingley was greatly influenced by nature, New England Transcendentalism and the Masonic background of her grandfather Nathan Chase.

1861: Tingley attended to those wounded in the Civil War while her family was in Virginia

1862–1865: Horrified at her response to the suffering soldiers, Tingley’s father sent her to Villa Marie Convent in Montreal, Quebec, over objections from her grandfather.

1867: Tingley briefly married Richard Henry Cook, a printer.

1866–1887: There is little or no documentation for this period, but Tingley had two unsuccessful, childless marriages. During part of this time, she was in Europe working in a travelling stage/drama group.

1880: Tingley married George W. Parent, an investigator for New York Elevated. The marriage ended by 1886.

1880s: Tingley adopted and raised two children, from her former husband, Richard Henry Cook’s, second marriage.

1887: Tingley formed the Ladies Society of Mercy to visit hospitals and prisons.

1888: Tingley married Philo B. Tingley in the spring. Philo B. Tingley joined the Manhattan, New York City Masonic group that year, where William Q. Judge was the almoner.

1888–1889: Katherine Tingley met William Q. Judge during a cloakmakers strike, somewhere between fall of 1888 and winter of 1889. Judge investigated her work for the Manhattan Masonic Lodge. The Lodge provided funding for some of Tingley’s Do Good Mission efforts.

1890 (April): W. Q. Judge was ill with gradually progressing tuberculosis and Chagres fever. He sent Tingley to Sweden on secret mission to meet King Oscar II, arranged through Masonic connections.

1888–1891: Tingley established various social work outreach projects, which included the Do Good Mission and the Women’s Emergency Relief Association, which arranged and provided a soup kitchen, clothing and medical needs in New York City for the Upper Eastside and for striking immigrant garment workers.

March 1896: William Q. Judge died.

April 1896: At the second annual convention of the Theosophical Society in America an announcement was made of the prospective founding by Tingley of the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity (SLRMA), generally referred to later as the School of Antiquity. Tingley was elected as head for life of Theosophical Society in America.

1896 (June 7): A ten-month World Theosophical Crusade was inaugurated to visit Theosophical centers, form new branches, and hold Brotherhood Suppers for the poor.

1896 (June 13): World Theosophical Crusade sailed from New York City, landed in England and then went to Ireland, Continental Europe, Greece (stopping to feed hundreds of Armenian refugees), then to Egypt (October), India (November/December), Australia (January 1897), New Zealand and Samoa. While on board the ship Tingley gave Theosophical talks for the steerage underclass passengers; while at various stops in Great Britain and Europe she held Brotherhood Suppers for the poor,

1896 (September): While in Switzerland, Tingley received information that the Point Loma, California location, which appeared to her in a vision, was available. She met Gottfried de Purucker (who would become her successor) who drew a map of Point Loma. Tingley sent the cable to purchase the land at Point Loma.

1896 (October/November): Tingley described her meeting with Helena P. Blavatsky’s young Tibetan “Teacher” in Darjeeling.

1897 (January): Tingley purchased 132 acres on Point Loma in San Diego, with option to buy an additional forty acres.

1897 (February 13): Tingley arrived at Point Loma.

1897 (February 23): Tingley officially laid the cornerstone for the future School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity. More than 1,000 people attended the ceremony.

1898: Tingley formally changed the name of her group from The Theosophical Society to The Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society.

1898 (November 19): Tingley produced a benefit performance in New York City of the Greek tragedy by Aeschylus, The Eumenides, for American soldiers and Spanish and Cuban sufferers in the Spanish American War. The New York Tribune reviewed the performance favorably.

1899 (February): Tingley met with large group from all over Cuba upon her arrival in Santiago, Cuba. She encountered Emilio Bacardi Moreau, the mayor of Santiago, Cuba and grandmaster of Masonic lodges in Cuba.

1899 (April 13): The first Universal Brotherhood Congress convened at Point Loma, with two performances of the Eumenides featuring a cast of two hundred.

1899 (September 13): The second Universal Brotherhood Congress convened in Stockholm, Sweden, with a reception attended by King Oscar II. There was another large gathering in Brighton, England, on October 6.

1899–1900: Extensive remodeling of the preexisting large sanatorium building into the Academy and Temple of Peace, along with extensive development of the Point Loma site, began.

1900: Raja Yoga school founded at Point Loma with first five students at Point Loma, including Iverson Harris Jr. and four daughters of Walter T. Hanson from Georgia: Coralee, Margaret, Estelle, and Kate.

1900: Tingley held a debate with Christians at the Fisher Opera House in San Diego. The Christians, who verbally attacked her and the Theosophists, declined to participate, and so Tingley presented both sides at the debate. She then purchased the Fisher Opera House and renamed it the Isis Theater after the Egyptian goddess.

1901: Tingley built the first Greek-style theater in America at Point Loma.

1901: Tingley produced a Greek symposium, The Wisdom of Hypatia, performed at the renamed Isis Theater. That same year saw dramatic productions of The Conquest of Death and a children’s drama Rainbow Fairy Play.

1901 (October 28): The Los Angeles Times headlined a sensationalized column: “Outrages at Point Loma: Women and Children Starved and Treated like Convicts. Thrilling Rescue.” Tingley’s subsequent suit for libel against the publisher Otis Gray, one of the most powerful people in California at that time, was successful and she was awarded $7,500.

1902: One hundred students were now enrolled at the Raja Yoga school. Two-thirds were Cuban, including children of Emilio Bacardi Moreau.

1903: Twenty-five Raja Yoga students were sent to Cuba to help launch schools there. Three schools were established. Nan Ino Herbert was the principal.

1903: Tingley journeyed to Japan with Gottfried de Purucker. She was impressed with Japanese discipline and ethic and invited Japanese educators to visit Point Loma.

1907: A Midsummer Night’s Dream was produced at Point Loma and performed in the Greek Theater, featuring original music, costumes, and set. Dozens of plays, mostly from Shakespeare and Aeschylus were produced at Point Loma over the next thirty years.

1907: Tingley had a private visit and meeting with King Oscar II of Sweden, who died a few weeks later. She purchased government land to establish a Raja Yoga school on Visingso Island in Sweden.

1909: The Raja Yoga schools were closed in Cuba due to financial strain. Tingley had been diverting Point Loma funds there, which was not sustainable.

1909: Kenneth Morris, Welsh poet and fantasist, moved to Point Loma.

1911: The first issue of The Theosophical Path appeared, with Gottfried de Purucker as acting editor. This journal was issued monthly in the same format from 1911 until 1929.

1911: Pageant and symposium, The Aroma of Athens, was written and performed by the Theosophists as a dramatic production at Isis Theater.

1911 (November): After a very moving visit to San Quentin, Tingley began to publish The New Way, an eight-page newsletter directed at prisoners and edited by Herbert Coryn. The newsletter stated that it was published by “The International Theosophical League of Humanity for Gratuitous Distribution in Prisons.”

1913 (Midsummer): 1913 (Midsummer): Tingley organized, with Swedish members, and attended with a group of Raja Yoga students from Point Loma, the Theosophical Peace Congress at Visingso Island.

1913–1920s: Tingley’s anti-war peace activities were pervasive from this time through the 1920s with many events and activities organized in San Diego and in Europe.

1914: Tingley inaugurated the Peace Day of Nations. Telegrams peace and anti-war messages were sent to President Woodrow Wilson.

1914–1915: Tingley lost part of an inheritance from A. B. Spaulding in a lawsuit brought by his heirs.

1915: Tingley suggested to plein air impressionist artist Maurice Braun, who had come to join the Theosophists in 1909, that he establish his art focus in San Diego, rather than at Point Loma. Braun became one of the founders of the San Diego Art Guild, which later became the San Diego Art Institute.

1914–1917: Tingley successfully campaigned against capital punishment in Arizona, supporting and collaborating with then-Governor George W. P. Hunt.

1917–1920: Tingley headed anti-vivisection animal rights efforts.

1919 (January): The Spanish Influenza, which raged throughout the nation, saw only a single case at Point Loma.

1920: Through a large publicity campaign Tingley successfully influenced the California governor to commute the sentence of Roy Wolff, who was seventeen at the time he killed a taxi driver.

1920s: At its height, Point Loma had residents from twenty-six nations.

1922: Katherine Tingley’s talk on Theosophy: The Path of the Mystic was printed and published at Point Loma.

1923: Adventure novelist Talbot Mundy took up residence at Point Loma, and there wrote his most mystical adventure story, Om the Secret of Ahbor Valley, in which the Lama protagonist is patterned after Tingley.

1923: Tingley met Rudolf Steiner, founder of the Anthroposophical Society, in Germany and proposed that the two groups merge. Tingley’s stroke later that year and Steiner’s death precluded this potential merger.

1923: Tingley lost a lawsuit that relatives brought in the Mohn family inheritance.

1925: Katherine Tingley’s talk on The Wine of Life, which outlined the ideal of the Theosophical home life, was printed and published at Point Loma.

1926: Katherine Tingley’s talk on The Gods Await was printed and published at Point Loma.

1927: Katherine Tingley’s talk on The Travail of the Soul was printed and published at Point Loma.

1929: Tingley had premonitions of her impending death, described by Elsie Savage Benjamin.

1929 (July 11): Katherine Tingley died in Sweden while on a European tour, following an auto accident in Germany.

BIOGRAPHY

Katherine Augusta Westcott was born in Newbury, Massachusetts on 6 July 1847. She grew up in New England, her childhood spent wandering along the banks of the Merrimac River near Newbury. The first years through her mid-teens appear to have been idyllic. She found the companionship of her grandfather, Nathan Chase, to be inspiring. She observed that she was drawn to the outdoors and described a nature-loving, interior, and more spiritualized orientation from early childhood. She portrayed her childhood experience and wonderment with the natural world, writing that “in my love of Nature and in my love of the true and the beautiful, in my love of this Eternal Supreme Power, my views broadened and I felt there is still greater knowledge and more wonderful meaning to human life” (Tingley 1925:286). Additionally, she was also drawn to the visitors and friends of her family, who were participants in the New England Transcendentalist movement. She wrote that she tried many philosophies, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and though they stirred her, they “did not quite satisfy.”

The first major transition in her life came in 1861 during the American Civil War. Her father was a regiment captain, stationed with the Union Army in Virginia, and there she witnessed the suffering and wounded soldiers. After the second battle of Bull Run, she saw “the ambulances returning with the dead and dying, followed by the files of Confederate soldiers, ragged and half starving” (Tingley 1926:36–37). Unable to bear the sight, Tingley and her African American servant went out among the soldiers and tended their wounds late into the night. However, her father’s reaction to Katherine’s impulse to aid the suffering and wounded was not a positive one. Out of concern for Katherine’s well-being he quickly sent her off, over the protests of her grandfather, a member of the Masons, to a Catholic boarding school administered by nuns at Villa Marie Convent in Montreal, Quebec. This was a highly regimented and structured environment, a drastic change from the free-spirited life in New England. She appears to have lived there until she was eighteen, and upon completing school, for reasons not clear, she did not return to her parents’ home.

From 1865 until 1880, there is almost no information on Tingley’s life, although she was briefly married to Richard Henry Cook, a printer, in 1867. From 1880 to 1888 all that is known is that she married a second time: George W. Parent was an investigator for New York Elevated. The marriage ended by 1886. By the mid-1880s, for a short time, she adopted and raised two children who were from her first husband’s second marriage. Tingley gave little information about these marriages other than that they were times of great suffering for her.

Living in New York City brought her into contact with the horrible conditions of those living on the East Side, and in 1887 she established a women’s group to visit prisons and hospitals, called the Ladies Society of Mercy. In 1888, she married Philo B. Tingley, a steamship employee and inventor, who would be Katherine’s connection to what would become the most world-changing event in her life, namely meeting William Q. Judge (1851–1896), president of the American Section of the Theosophical Society. The same year he married Katherine, Philo Tingley had joined the Manhattan Masonic Lodge, where Judge was the bursar. Katherine’s work with the poor and particularly with the plight of striking garment workers and their working conditions was suggested as a charitable project. Judge, as the Masonic Lodge treasurer, was sent to check on it, view the project in action and determine if it was worth supporting. Historical documents discovered in 2015 clearly indicate that Judge first saw Katherine in late 1888 at her “Do Good” outreach mission, when, as she would describe later, she saw an unusual gentleman within the crowd of the downtrodden, “strikingly noble of expression, with a look of grave sadness and of sickness too” (Tingley 1926:79). They met in person for the first time in early 1889. “It was then, when I came to know him, that I realized that I had found my place. I was face to face with a new type of human nature: with something akin to that which my inner consciousness had told me a perfect human being might be” (Tingley 1926:79–80). It is remarkable that both Judge and Tingley kept her connection with him and the Theosophical Society totally secret until 1894, even though revealing it would have greatly benefited her position with those Theosophists who were critical of her.

During 1894 and possibly earlier, Katherine took Judge to warmer weather and hot springs in Texas and Arkansas for rest and  recuperation from his progressing tuberculosis and Chagres fever. At the same time, she formally joined the Theosophical Society and a month later Judge admitted her to the private Esoteric Section. As it became clearer that Judge’s chronic illness was more serious, Tingley [Image at right] was introduced to a few Theosophists in 1895. Tensions and differences had been building between William Q. Judge and both Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), who had remained with the parent Theosophical Society headquartered in Adyar, India. There were a complex and contentious series of events, which turned acrimonious at times. This finally came to a head when Judge led the American Section to secede from the Theosophical Society in 1895. Declaring autonomy, the Theosophical Society in America was established and William Q. Judge was elected president for life (Ryan 1975). At that time, Katherine Tingley rapidly moved to the center of governance as Judge’s health declined further.

recuperation from his progressing tuberculosis and Chagres fever. At the same time, she formally joined the Theosophical Society and a month later Judge admitted her to the private Esoteric Section. As it became clearer that Judge’s chronic illness was more serious, Tingley [Image at right] was introduced to a few Theosophists in 1895. Tensions and differences had been building between William Q. Judge and both Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), who had remained with the parent Theosophical Society headquartered in Adyar, India. There were a complex and contentious series of events, which turned acrimonious at times. This finally came to a head when Judge led the American Section to secede from the Theosophical Society in 1895. Declaring autonomy, the Theosophical Society in America was established and William Q. Judge was elected president for life (Ryan 1975). At that time, Katherine Tingley rapidly moved to the center of governance as Judge’s health declined further.

Upon Judge’s death in 1896, Tingley was elected president for life. Conflicts and schisms followed, but Tingley forged ahead. She quickly shifted the direction of the Theosophical Society in America to create an educational and living community where Theosophy could be practiced in daily life and not only for abstract study of metaphysics or the exploring of visionary realms. It was her aim to make Theosophy “intensely practical” and rooted in a deep altruistic ethic. At the January 13, 1898 convention, she would rename it the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society (UBTS). For the direct application of her philanthropic work she also established the International Brotherhood League, which carried on a very large relief effort in Cuba in 1898 after the Spanish-American War, and also served the sick and wounded soldiers returning from the war. President William McKinley authorized the use of U.S. Government transport to take Tingley, her physicians and other workers to Cuba with large supplies of food, clothing, and medicines (Ryan 1975:348).

In 1896, she gathered together a few supporters for a Theosophical Crusade and headed off around the world, beginning in  Europe. In Switzerland she met a young Theosophical Society member, Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942) for the first time. He had joined the Theosophical Society and met Judge who admitted him to the Esoteric Section without the usual probationary period. De Purucker had been to California a few years before and lived in San Diego in 1893, working on a ranch and leading study groups in the Secret Doctrine by the co-founder of the original Theosophical Society, Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). De Purucker helped Tingley identify the land at Point Loma in San Diego for purchase for the UBTS project (PLST Archive). Meanwhile, the Theosophical “crusaders” traveled through the Middle East and sailed on to India. [Image at right] Early one morning near Darjeeling, Tingley evaded her companions and slipped off up into the foothills. She would return a day or so later, stating she had visited one of Blavatsky’s “Teachers” referring to the encounter as “life transforming” (Tingley 1926:155–162; and Tingley 1928). Some years later Tingley would reflect that her encounter with Blavatsky’s young Tibetan “Teacher” in India had given her the courage to continue with establishing and developing the Point Loma community and the gradual alleviation and reversal of symptoms of her chronic Addison’s kidney/adrenal disease. For Katherine Tingley this was a much needed and spiritually life-changing experience, that brought her the energy and motivation to bring her vision of a “White City in the West” into manifestation.

Europe. In Switzerland she met a young Theosophical Society member, Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942) for the first time. He had joined the Theosophical Society and met Judge who admitted him to the Esoteric Section without the usual probationary period. De Purucker had been to California a few years before and lived in San Diego in 1893, working on a ranch and leading study groups in the Secret Doctrine by the co-founder of the original Theosophical Society, Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). De Purucker helped Tingley identify the land at Point Loma in San Diego for purchase for the UBTS project (PLST Archive). Meanwhile, the Theosophical “crusaders” traveled through the Middle East and sailed on to India. [Image at right] Early one morning near Darjeeling, Tingley evaded her companions and slipped off up into the foothills. She would return a day or so later, stating she had visited one of Blavatsky’s “Teachers” referring to the encounter as “life transforming” (Tingley 1926:155–162; and Tingley 1928). Some years later Tingley would reflect that her encounter with Blavatsky’s young Tibetan “Teacher” in India had given her the courage to continue with establishing and developing the Point Loma community and the gradual alleviation and reversal of symptoms of her chronic Addison’s kidney/adrenal disease. For Katherine Tingley this was a much needed and spiritually life-changing experience, that brought her the energy and motivation to bring her vision of a “White City in the West” into manifestation.

The Point Loma community began in 1897 with Tingley’s arrival. Great enthusiasm and energy accompanied construction and transformation of the grounds, which were called Lomaland. By 1899, the first five students were enrolled in the Raja Yoga school, and by 1902 there were a hundred, of whom about seventy-five were from Cuba. Collaborating with Emilio Bacardi Moreau (1844–1923), mayor of Santiago, Cuba, she began a mission to build schools in Cuba and to bring Cuban students to the Raja Yoga School at Point Loma. By 1915, the school in San Diego reached its peak with 500 students (Greenwalt 1978). The Raja Yoga curriculum evolved quickly, with its emphasis on the creative arts: the classics, music, drama, art, and literature, as well as science, sports and agriculture. The overarching view that the Point Loma community manifested was what Tingley called the School of Antiquity. According to Tingley’s secretary, Joseph H. Fussell, the purpose of the School of Antiquity was to revive a knowledge of the Sacred Mysteries of Antiquity by promoting the physical, mental, moral and spiritual education and welfare of the people of all countries, irrespective of creed, sex, caste or color; by instructing them in an understanding of the laws of universal nature and justice and particularly the laws governing their own being: the teaching them the wisdom of mutual helpfulness, such being the science of Raja Yoga. (qtg Tingley, Fussell 1917:12).

The School of Antiquity and the entire vision and form of the Point Loma community was patterned after Tingley’s conception of an ancient mystery school, drawing a great deal of her inspiration from Plato and Pythagorean ideas. Elsie Benjamin described the mission as being to replicate an ancient Mystery-School:

In the ancient Mystery-Schools, the pupils were more like children: they have instinct, they have intuition, but they didn’t have full self-consciousness. . . . Because Judge had told K.T., that it is not your mission to teach them technical Theosophy. Your mission is to teach them morals, ethics, universal brotherhood, humanity and self-discipline (Benjamin).

Tingley’s vision of “practical Theosophy” encompassed all of the arts, and much more. For her, the architecture of Lomaland needed to express the sacredness of home and place, as both receptacle and expression of a higher divine source. Her inspiration culturally was, at least in part, Greek and Pythagorean harmonics. Of the unique buildings designed and built at Lomaland, the Greek Theater remains as the single purely classically Greek structure. Other structures, such as the Temple of Peace or the home of Elizabeth Mayer Spaulding, wife of sporting goods magnate Albert G. Spaulding, reflected influences from India and Persia.

Drama played a significant role, not only to develop community esprit d’corps, but for the individual transformational elements involved. From 1903 into the 1930s, the Point Loma Theosophical community produced scores of plays. Tingley chose Greek tragedy and Shakespeare’s dramas for what she viewed as their philosophical perennialism and universal Theosophic ideas, combined with the participatory opportunity that drama has for inner psychological and spiritual development. There were also productions of their own plays, including one based on Socrates’ dialogues in Plato, called The Aroma of Athens. Another, based on the life of the fourth-century Alexandrian neo-Platonist woman philosopher Hypatia, featured Katherine Tingley in the lead role. Reviews in the San Diego Union reflected the central role that the Theosophical productions played in San Diego’s cultural life.

Well-known artists from the U.S. and abroad came to live and work at Lomaland and there developed a unique mystical style. The late 1890s view of art held by Reginald Willoughby Machell (1854–1927), presaged a later twentieth-century phenomenological view found in philosophers like Kitaro Nishida, Maurice Merleau-Ponty or Ananda Coomaraswamy, where an understanding of how the awareness of observer and object are experienced as highly interdependent with the art object and its creation. Said Machell:

Beauty is really a state of mind. The senses only register vibrations, which are translated by the mind into colour, form, sound. . . . It would be more true perhaps to say that beauty is in both observer and observed, but not in one apart from the other (Machell 1892:4).

Another artist who developed a Theosophical style was Maurice Braun (1877–1941). According to Emmett Greenwalt, “Braun was not hesitant in crediting Theosophy with sharpening his insight into nature. To him art was for ‘the service of the divine powers in man,’ or as he otherwise phrased it, ‘art for humanities sake,’ and he saw in Theosophy ‘the champion and inspirer or all that is noble and true and genuine in art’” (Greenwalt 1978: 129–31).

In addition to her devotion to the arts, Katherine Tingley worked for social justice and peace throughout her life. She had been involved in a prison ministry project which involved corresponding with prisoners. She was engaged in movements to abolish capital punishment in California and Arizona. She also organized an anti-vivisection program to protect animal welfare.

In 1922 or 1923, Tingley, around age seventy-six, [Image at right] suffered a minor stroke. It did not cause any noticeable physical  debility, but from then until her death, she suffered a kind of emotional agitation at times when under stress. When it became severe, her office staff would call for Gottfried de Purucker to come, given his very calming influence on her in general, and his presence would usually resolve Tingley’s anxieties.

debility, but from then until her death, she suffered a kind of emotional agitation at times when under stress. When it became severe, her office staff would call for Gottfried de Purucker to come, given his very calming influence on her in general, and his presence would usually resolve Tingley’s anxieties.

The last seven years of her life can be seen as a gradual decline of the Point Loma experiment, after the dynamic growth and successes of the 1910–1922 period. Her important financial backers of the earlier period had almost all died, and the expenses for maintaining Lomaland had stayed the same. Over this time, significant debt was incurred, even to mortgaging part of the property to maintain the community. The drama, art, music and Raja Yoga school continued, but the income was less. Some long-time residents also left Point Loma at this time, including Hildor and Margueite Barton, Montegue Machell and his wife Coralee (one of the Hanson sisters), and E. August Neresheimer and his wife Emily Lemke. Tingley expressed her dismay and felt that she had not lived up to supporting her committed residents and partisans, especially Reginald Machell.

By late spring of 1929, and approaching the age of eighty-two, Tingley was ready to travel to Europe yet again. Elsie Savage Benjamin, then her secretary, was helping with preparations and sharing her concerns with Tingley about the European trip. She was especially concerned about driving with an inexperienced young man whom Tingley had chosen to be her chauffeur for the tour. Tingley, with her darting, penetrating eyes rapidly responded to Elsie with extraordinary prescience: “Don’t you know, he’s going to be in a car crash and kill someone” (Benjamin n.d.). On May 31, 1929, driving in the fog near dawn on a winding road in Germany about fifty miles from the Dutch border, the chauffeur crashed the car into a concrete bridge pier (Greenwalt 1955:192). Tingley had a double fracture of her right leg and much bruising. Others in the car were also injured. Tingley insisted on being taken to Visingso Island in Sweden rather than to a hospital. Staying in command until the last, and in considerable pain, she even dismissed her doctor rather than be moved to where she could receive better medical care. Katherine Tingley died on Visingso Island, what she considered sacred land, July 11, 1929.

TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Tingley saw Theosophy, “not so much as a body of philosophic or other teaching, but as the highest law of conduct, which is the enacted expression of divine love or compassion” (Tingley The Theosophical Path :3). This divine love could be realized only in a communal setting in which people lived and worked together to express their best selves.

For Tingley, educating children’s minds so that they recognized the Immortal Self was “the truest and grandest thing of all as regards education” (Tingley The Theosophical Path:175). Toward this end she founded the Raja Yoga system in order to develop children’s character so that their true nature would emerge from within. “The real secret of the Raja Yoga system is rather to evolve the child’s character than to overtax the child’s mind; it is to bring out rather than to bring to the faculties of the child. The grander part is from within” (Tingley The Theosophical Path:174). The essential divinity of humanity served as the foundation for this kind of education, with a curriculum integrating body, mind, and spirit, in which all participated. Physical cultivation along with intellectual training were required, so that the intellect would be “the servant, not the master.” Thus, the Raja Yoga system, which Tingley called a “science of the soul,” would pervade all life and activity, becoming “the true expression of soul-ideals” so that art would no longer be extraneous to life, but rather an integral part of the environment (Tingley The Theosophical Path: 159–75). This view toward the arts as the means to develop the whole person helps explain Tingley’s passion for theater, since drama, in her view, reached the heart of everyone.

Clearly influenced by Blavatsky’s writings on education, Tingley nevertheless created a practical program not envisaged by her predecessor. She outlined it as follows:

The basis of this education is the essential divinity of man, and the necessity for transmuting everything in his nature which is not divine. To do this no part must be neglected, and the physical nature must share to the full in the care and attention which are required. Neither can the most assiduous training of the intellect be passed over; it must be made subservient to the forces of the heart. The intellect must be the servant, not the master, if order and equilibrium are to be attained (Emmett W. Small n.d.:93–94).

RITUALS/PRACTICES

While there was no group liturgy at Lomaland, there were daily community practices. Tingley spoke of “the sacredness of the moment and the day” and sought to make Theosophy intensely practical as “the enacted expression of divine love or compassion” (Tingley 1922:3) According to her, “The ideal must no longer be left remote from life, but made divinely human, close and intimate, as of old. NOW is the day of resurrection” (Tingley 1922:94). The daily life practice at Lomaland could be compared to the group spiritual practice in the monastic traditions of east and west, yet with unique differences. The Lomaland practice was based on the creative arts within the context of the wisdom traditions of East and West. Daily group activity was ritualized in common endeavors that were creative, contemplative and inspirational, encapsulated within an altruistic ethic. As she expressed it, “Intellectualism has no lasting power without the practice of the highest morality” (Tingley 1922:98). It was a community, the center of which was the education of children.

The entire community gathered together daily at sunrise at the Greek Theater or in the Temple of Peace. Inspirational phrases were read from literature such as the Bhagavad Gita, the Buddha’s life story in Edwin Arnold’s poetic rendition in The Light of Asia, from Theosophical sources, including Light on the Path by Mabel Collins (1885) and the Voice of the Silence by Blavatsky (1889). This was followed by silent contemplation. Meals were eaten in a group setting and in silence, with a brief recitation before each meal and upon entering the refectory eating area; men and women were grouped together. Idle talk was discouraged and the overall quality of the community was to “do well the smallest duty . . . then joy will come” (Tingley 1927:274–75).

The following invocation, given to the students by Katherine Tingley, was recited in unison primarily at meetings held in the Temple, but also on many occasions elsewhere.

Oh my Divinity! Thou dost blend with the

earth and fashion for thyself Temples of mighty power.

Oh my Divinity! thou livest in the heart-life

of all things and dost radiate a Golden Light

that shineth forever and doth illumine even the

darkest comers of the earth.

Oh my Divinity! blend thou with me that

from the corruptible I may become Incorruptible;

that from imperfection I may become Perfection;

that from darkness I may go forth in

Light.

In addition to the morning gatherings in silence and meditation with devotional readings, there was also community music, both instrumental and choral. Everyone sang in the chorus and played a musical instrument. Tingley considered music to be of central value for inner transformation and life harmony: “The soul power which is called forth by a harmony well delivered and well received does not die away with the conclusion of the piece” (Tingley 1922:178). She would attract to Point Loma the renowned director of the Amsterdam Conservatory of music, Daniël de Lange (de Lange 2003), from 1910 to 1915, who transformed the Raja Yoga orchestra into a symphonic quality musical group.

There were frequent gatherings on cultural and Theosophical subjects for presentations in the Temple of Peace. Regular Point Loma visitors, like art historian Osvald Siren (1879–1966), would give lectures in the Temple illustrated by lantern slides of photos from his recent journeys in China or Asian or European art history (Carmen Small n.d.). Lomaland was an oasis of sophistication in the cultural wasteland that was San Diego at the turn of the twentieth century.

LEADERSHIP

Katherine Tingley’s leadership began in 1896, when she was elected amidst some controversy to succeed William Q. Judge as leader for life of the Theosophical Society in America. This resulted in a number of outer changes, including the change of name to the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society and also the shift of primary focus from lodges to the establishment of the community at Lomaland. These alterations also provided a shift in the internal culture within Tingley’s Theosophical movement at the time, which could be described as a shift from discursive metaphysics to Theosophy in daily activity. There was the practical work for Universal Brotherhood, e.g. promoting global peace, prison outreach, capital punishment abolition and so on, but there was also a new modality, where cultivating an inner ethic of altruistic motivation and awareness was primary. This change opened the door, to what could be described as contemplative Theosophy. As Tingley declared:

Wisdom comes not from the multiplication of spoken or written instructions; what you have is enough to last you a thousand years. Wisdom comes from the performance of duty, and in the silence, and only the silence expresses it (Tingley 1925:343).

As a self-proclaimed dictator, Tingley appeared to wield the primary power in the organization, but as the Point Loma community developed, that control was progressively counterbalanced by her delegating responsibilities to others. There was a complex of interconnected departments and committees at Lomaland, which managed everything from maintaining the extensive agricultural gardens with fruit orchards, to supervising school curriculum, Theosophical programs and running a large communal endeavor. The one area in which Tingley immersed herself was her personal direction and management of the dramatic productions in the Greek Theater at Lomaland and at the Isis Theater in San Diego. She felt most at home in the role of guide to the students’ inner development of character and spirituality when she was absorbed in the dramatic productions. In this context, she would exclaim to one student, “I work best in utter chaos” (Harris n.d.).

Tingley was definitely not a micromanager. This is evidenced, for example, by her giving a free hand to Gottfried de Purucker in 1911 in the editorship of The Theosophical Path. She never read or indicated what or what not to print in it and would read the issues, as time permitted, only after they were published (Emmett W. Small n.d.). When she requested a couple of the resident artists to make some Christmas cards by hand for her, it was left to their creativity to work out the design and quotes used (Lester n.d.). Clearly the rapid development and success in establishing the Point Loma community and Raja Yoga school with all its activities of art, music, drama etc., was the result of her delegating and giving others the reins. In addition, she was away travelling almost every summer for a few months, though she made use of letters, cards and telegrams daily while away, keeping a close connection with everyone, including young students and administrators.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Throughout the Lomaland period of her life, Tingley faced several lawsuits and filed one of her own against the Los Angeles Times for libel, which she won. There was more than one attempt on her life. On one occasion, a man with a loaded pistol attempted to reach where she was seated at the Isis Theater, but was stopped by a quick acting police guard (Harris n.d.). In the later 1920s, Tingley mortgaged part of the Lomaland property, over de Purucker’s pleas not to do so (Emmett W. Small n.d.; Harris n.d.). Most of the long-term residents had given everything they had when arriving at Lomaland in exchange for lifetime residency. Yet their contributions were spent on either maintaining the community or on Raja Yoga School projects in Cuba and Europe, especially since the income from the Raja Yoga School was insufficient to maintain expenses.

After Tingley’s death, the financial condition of Lomaland was precarious, but under the leadership of her successor, Gottfried de Purucker, and thanks to frugal cutbacks and voluntary reduction of residents to around 125, the overwhelming debt had been paid off by the mid-1930s. From 1929 through the 1930s, more than half of the donations received to support Lomaland were coming from Europe. By 1938, while the political conditions in Germany were rapidly deteriorating, donations from European members dried up. De Purucker sent out an urgent letter asking everyone to eliminate any expense possible to save on the monthly outlay (PLST Archive).

During de Purucker’s period, dramatic productions had continued with creative success under the direction of Florence Collison, though the dramas were reduced in pageantry compared to the Tingley era. Also, the Raja Yoga School still had significant numbers of children from San Diego residents, but the entire scope of both community activities and outreach, compared to the peak around 1920, was greatly diminished. There was insufficient income without the outside donations.

By the end of 1941, the community was hard pressed financially, with additional stress nearby when the U.S. government placed large military bunkers with artillery both north and south of the property and out on Point Loma itself. Tension was heightened with the U.S. declaration of war with Japan over the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. De Purucker had already sent out individuals scouting California for a smaller less encumbered property and developed a plan to shrink the number of residents yet again. He had found a property in Cupertino that he preferred, but it could only accommodate a small staff of fifteen or so. In January 1942, the decision was made to sell the property and move to Covina, east of Los Angeles, where a boys’ school facility was purchased. The move in spring of 1942 was followed by de Purucker’s sudden death from a heart attack at Covina on September 27. De Purucker left no indications of a designated heir, but he did write out a letter giving advice and direction for interim governance and recommendations for the cabinet to follow for electing a president for the society (PLST Archive).

Internal conflict within the group amidst questions and assertions of spiritual authoritative power would break out in 1945 over the cabinet’s election of a new leader. As Yeats expressed it poetically, “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold,” and amidst dissension the magic of Point Loma had ceased and withdrawn, leaving antagonists with varying assertions and claims to inheriting the earlier holy grail. Despite the hopeful move to Covina, the qualities nurtured and grown at Point Loma could not endure. The sacred architecture was gone, music and the arts had faded, and the daily community group activities were radically reduced.

IMAGES

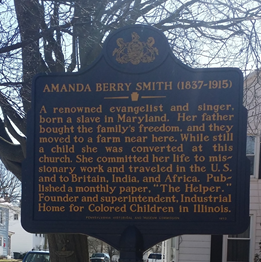

Image #1: Photograph of Katherine Tingley in the in the early 1900s.

Image #2: Photograph of Katherine Tingley on the way to meeting with one of Helena P. Blavatsky’s teachers in India.

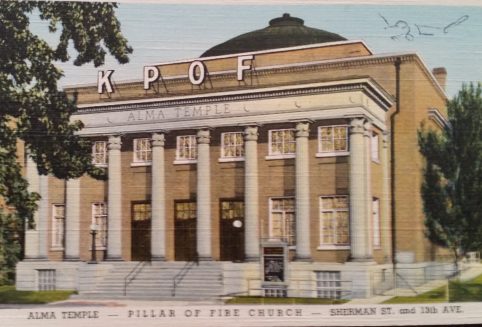

Image #3: Photograph of Katherine Tingley in the mid-1920s.

REFERENCES

De Lange, Daniël. 2003. Thoughts on Music: Musical Art as Explained as One of the Most Important Means of Building up Man’s Character. The Hague: International Study Centre for Independent Search for Truth; reprinted from The Theosophical Path where it was published in ten installments between November 1916 and May 1918.

Fussell, Joseph H. 1917. The School of Antiquity: Its Meaning, Purpose and Scope. Point Loma, CA: Aryan Philosophical Press.

Greenwalt, Emmett. 1955, revised 1978. California Utopia: The Point Loma Community in California, 1897–1942. San Diego: Point Loma Publications.

Machell, Reginald. 1892. Theosophical Siftings. Volume 5.

Ryan, Charles. 1937, revised 1975. H. P. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Movement. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Writings by Katherine Tingley

1922. Theosophy. The Path of the Mystic. With Grace Frances Knoche. Point Loma, CA: Woman’s International Theosophical League.

1925. The Wine of Life. With preface by Talbot Mundy. Point Loma, CA: Woman’s International Theosophical League.

1926. The Gods Await. Point Loma, CA: Woman’s International Theosophical League.

1928. The Voice of the Soul. Point Loma, CA: Woman’s International Theosophical League.

1978. The Wisdom of the Heart: Katherine Tingley Speaks. Edited by W. Emmett Small. San Diego: Point Loma Publications.

Tingley, Katherine, ed. 1911–1929. The Theosophical Path [Theosophy periodical].

Primary Archival References

Point Loma School of Theosophy Archive. Accessed from http://www.pointlomaschool.com on 5 March 2017. (PLST Archive in text).

Recorded Interviews, Oral Histories, and Personal Writings.

Benjamin, Elsie Savage. n.d. Recorded Interviews. [Secretary to Katherine Tingley].

Harris, Helen. n.d. Notebooks. [Lomaland Resident].

Harris, Iverson L., Jr. n.d. Oral History. [Lomaland Resident].

Lester, Marian Plummer. n.d. Oral History. [Lomaland Resident].

Small, Carmen H. n.d. Oral history. [Lomaland Resident].

Small, W. Emmett. n.d. Oral History. [Lomaland Resident].

Post Date:

8 March 2017

sources that have her husband, Victor Houteff (1885–1955), founder of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists, as their principal subject. [Image at right] This presents a problem of perspective. Nevertheless, there are some biographical details that are helpful to report here. Florence was born in 1919, the daughter of Eric and Sopha Hermanson and sister to Thomas Oliver Hermanson. Members of the Hermanson family were among the very earliest converts to the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists, a group from which the later Branch Davidians were to emerge. According to a census return dated 1940, Sopha, Thomas Oliver and Florence Hermanson/Houteff were already residing at the Mount Carmel Center in Waco, Texas in 1935, with their earlier place of residence listed as Los Angeles. These details are in full accord with the wider reconstructed narrative of the beginnings of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists given in secondary sources. Newport, for example, provides evidence that Florence was among the very first group of Davidians to move from California to Texas, a trip that commenced on May 19, 1935 (Newport 2006a:57). Florence’s actual place of birth is listed as Wisconsin. This same census record lists Florence as being the wife of Victor, which makes the reported date of January 1, 1937 entirely plausible (Newport 2006a:58).

sources that have her husband, Victor Houteff (1885–1955), founder of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists, as their principal subject. [Image at right] This presents a problem of perspective. Nevertheless, there are some biographical details that are helpful to report here. Florence was born in 1919, the daughter of Eric and Sopha Hermanson and sister to Thomas Oliver Hermanson. Members of the Hermanson family were among the very earliest converts to the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists, a group from which the later Branch Davidians were to emerge. According to a census return dated 1940, Sopha, Thomas Oliver and Florence Hermanson/Houteff were already residing at the Mount Carmel Center in Waco, Texas in 1935, with their earlier place of residence listed as Los Angeles. These details are in full accord with the wider reconstructed narrative of the beginnings of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists given in secondary sources. Newport, for example, provides evidence that Florence was among the very first group of Davidians to move from California to Texas, a trip that commenced on May 19, 1935 (Newport 2006a:57). Florence’s actual place of birth is listed as Wisconsin. This same census record lists Florence as being the wife of Victor, which makes the reported date of January 1, 1937 entirely plausible (Newport 2006a:58). movement. Her ascendency in 1955 was not uncontested however; there were at least three other contenders, including the later founder of the Branch Davidians, Ben Roden (1902–1978) (Newport 2006a:96). Florence occupied the leadership position until her resignation in March 1962. That resignation, which was not Florence’s alone but that of the entire executive council, marked the breakup of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists into several splinter groups, one of which was to become the Branch Davidians (see further Newport 2006b). Little is known of Florence following this key event. However, it is clear that at some point she married Carl Levi Eakin (1910–1998), whose grave, like that of Florence Marcella Hermanson Eakin, is located at Evergreen Memorial Gardens in Vancouver, Washington. [Image at right] The date of Florence’s death is given as September 14, 2008.

movement. Her ascendency in 1955 was not uncontested however; there were at least three other contenders, including the later founder of the Branch Davidians, Ben Roden (1902–1978) (Newport 2006a:96). Florence occupied the leadership position until her resignation in March 1962. That resignation, which was not Florence’s alone but that of the entire executive council, marked the breakup of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists into several splinter groups, one of which was to become the Branch Davidians (see further Newport 2006b). Little is known of Florence following this key event. However, it is clear that at some point she married Carl Levi Eakin (1910–1998), whose grave, like that of Florence Marcella Hermanson Eakin, is located at Evergreen Memorial Gardens in Vancouver, Washington. [Image at right] The date of Florence’s death is given as September 14, 2008. claim that on his deathbed Victor had specifically named her as the chosen successor, a claim that was reinforced by Florence’s brother Thomas Oliver Hermanson. There appear to have been no further witnesses to Victor’s words on this matter, and unsurprisingly it was challenged by some others within the movement, particularly by those who harbored ambition for the highest office themselves. In the end, however, since no one else was able to produce evidence either that Florence had not been so designated or that another claimant had a better case, Florence was appointed to the Vice-Presidency of the group. Victor Houteff’s actual post of President was not again filled as it was one to which only God could appoint.

claim that on his deathbed Victor had specifically named her as the chosen successor, a claim that was reinforced by Florence’s brother Thomas Oliver Hermanson. There appear to have been no further witnesses to Victor’s words on this matter, and unsurprisingly it was challenged by some others within the movement, particularly by those who harbored ambition for the highest office themselves. In the end, however, since no one else was able to produce evidence either that Florence had not been so designated or that another claimant had a better case, Florence was appointed to the Vice-Presidency of the group. Victor Houteff’s actual post of President was not again filled as it was one to which only God could appoint.

Québec City, Québec. Later, Lac-Etchemin (where a small Marian shrine was built in the 1950s) would acquire a peculiar significance in Giguère’s millennial worldview. A pious young girl, Marie-Paule considered religious life as a missionary in Africa, but her poor health was interpreted by her spiritual advisors as a sign that the Lord was calling her to marriage. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917–1997), with whom she had five children between 1945 and 1952. [Image at right] But the marriage proved a nightmare, with Georges revealing himself to be prodigal, alcoholic, and adulterous. The Church, while opposed to divorce, accepted separation in extreme cases, and several priests suggested that Marie-Paule leave her husband. She did so, reluctantly, in 1957, and later attempts at reconciliation proved unsuccessful, although as an old man Georges would eventually join Marie-Paule’s movement.

Québec City, Québec. Later, Lac-Etchemin (where a small Marian shrine was built in the 1950s) would acquire a peculiar significance in Giguère’s millennial worldview. A pious young girl, Marie-Paule considered religious life as a missionary in Africa, but her poor health was interpreted by her spiritual advisors as a sign that the Lord was calling her to marriage. In 1944, she married Georges Cliche (1917–1997), with whom she had five children between 1945 and 1952. [Image at right] But the marriage proved a nightmare, with Georges revealing himself to be prodigal, alcoholic, and adulterous. The Church, while opposed to divorce, accepted separation in extreme cases, and several priests suggested that Marie-Paule leave her husband. She did so, reluctantly, in 1957, and later attempts at reconciliation proved unsuccessful, although as an old man Georges would eventually join Marie-Paule’s movement. radio stations. In 1954, she supernaturally heard for the first time a reference to “the Army of Mary,” a “wonderful movement” she would later lead (Giguère 1979–1994, 1:174). [Image at right] Slowly, a small Marian group was formed, which included a couple of priests. On August 28, 1971, during a pilgrimage to the Lac-Etchemin shrine, Marie-Paule officially inaugurated the

radio stations. In 1954, she supernaturally heard for the first time a reference to “the Army of Mary,” a “wonderful movement” she would later lead (Giguère 1979–1994, 1:174). [Image at right] Slowly, a small Marian group was formed, which included a couple of priests. On August 28, 1971, during a pilgrimage to the Lac-Etchemin shrine, Marie-Paule officially inaugurated the  he moved from France to Québec, where he became the editor of the movement’s magazine, L’Étoile (later replaced by Le Royaume). In the years that followed, the Army of Mary gathered thousands of followers in Canada and hundreds more in Europe. The Community of the Sons and Daughters of Mary, a religious order including both priests and nuns, was established in 1981, with Pope John Paul II (1920–2005) personally ordaining the first Son of Mary as a priest in 1986. Several other ordinations followed, and a number of Catholic dioceses throughout the world were happy to welcome both the Sons and the Daughters of Mary to help them in their pastoral work. After her husband’s death in 1997, Marie-Paule herself became a Daughter of Mary, and was subsequently elected Superior General of the congregation as Mère Marie-Paule, later Mère Paul-Marie. [Image at right] A larger “Family of the Sons and Daughters of Mary” also included auxiliary organizations, such as the Oblates-Patriots, established by Marie-Paule in 1986 with the aim of spreading conservative Catholic social teachings, and the Marialys Institute, created in 1992, which gathered together Catholic priests who were not members of the Sons of Mary but shared their general aims.

he moved from France to Québec, where he became the editor of the movement’s magazine, L’Étoile (later replaced by Le Royaume). In the years that followed, the Army of Mary gathered thousands of followers in Canada and hundreds more in Europe. The Community of the Sons and Daughters of Mary, a religious order including both priests and nuns, was established in 1981, with Pope John Paul II (1920–2005) personally ordaining the first Son of Mary as a priest in 1986. Several other ordinations followed, and a number of Catholic dioceses throughout the world were happy to welcome both the Sons and the Daughters of Mary to help them in their pastoral work. After her husband’s death in 1997, Marie-Paule herself became a Daughter of Mary, and was subsequently elected Superior General of the congregation as Mère Marie-Paule, later Mère Paul-Marie. [Image at right] A larger “Family of the Sons and Daughters of Mary” also included auxiliary organizations, such as the Oblates-Patriots, established by Marie-Paule in 1986 with the aim of spreading conservative Catholic social teachings, and the Marialys Institute, created in 1992, which gathered together Catholic priests who were not members of the Sons of Mary but shared their general aims. something theologically and canonically impossible in the Roman Catholic Church. On July 11, 2007, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith excommunicated those advocating and propagating the doctrines of the Army of Mary.

something theologically and canonically impossible in the Roman Catholic Church. On July 11, 2007, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith excommunicated those advocating and propagating the doctrines of the Army of Mary. recuperation from his progressing tuberculosis and Chagres fever. At the same time, she formally joined the Theosophical Society and a month later Judge admitted her to the private Esoteric Section. As it became clearer that Judge’s chronic illness was more serious, Tingley [Image at right] was introduced to a few Theosophists in 1895. Tensions and differences had been building between William Q. Judge and both Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), who had remained with the parent Theosophical Society headquartered in Adyar, India. There were a complex and contentious series of events, which turned acrimonious at times. This finally came to a head when Judge led the American Section to secede from the Theosophical Society in 1895. Declaring autonomy, the Theosophical Society in America was established and William Q. Judge was elected president for life (Ryan 1975). At that time, Katherine Tingley rapidly moved to the center of governance as Judge’s health declined further.

recuperation from his progressing tuberculosis and Chagres fever. At the same time, she formally joined the Theosophical Society and a month later Judge admitted her to the private Esoteric Section. As it became clearer that Judge’s chronic illness was more serious, Tingley [Image at right] was introduced to a few Theosophists in 1895. Tensions and differences had been building between William Q. Judge and both Annie Besant (1847–1933) and Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), who had remained with the parent Theosophical Society headquartered in Adyar, India. There were a complex and contentious series of events, which turned acrimonious at times. This finally came to a head when Judge led the American Section to secede from the Theosophical Society in 1895. Declaring autonomy, the Theosophical Society in America was established and William Q. Judge was elected president for life (Ryan 1975). At that time, Katherine Tingley rapidly moved to the center of governance as Judge’s health declined further. Europe. In Switzerland she met a young Theosophical Society member, Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942) for the first time. He had joined the Theosophical Society and met Judge who admitted him to the Esoteric Section without the usual probationary period. De Purucker had been to California a few years before and lived in San Diego in 1893, working on a ranch and leading study groups in the Secret Doctrine by the co-founder of the original Theosophical Society, Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). De Purucker helped Tingley identify the land at Point Loma in San Diego for purchase for the UBTS project (PLST Archive). Meanwhile, the Theosophical “crusaders” traveled through the Middle East and sailed on to India. [Image at right] Early one morning near Darjeeling, Tingley evaded her companions and slipped off up into the foothills. She would return a day or so later, stating she had visited one of Blavatsky’s “Teachers” referring to the encounter as “life transforming” (Tingley 1926:155–162; and Tingley 1928). Some years later Tingley would reflect that her encounter with Blavatsky’s young Tibetan “Teacher” in India had given her the courage to continue with establishing and developing the Point Loma community and the gradual alleviation and reversal of symptoms of her chronic Addison’s kidney/adrenal disease. For Katherine Tingley this was a much needed and spiritually life-changing experience, that brought her the energy and motivation to bring her vision of a “White City in the West” into manifestation.

Europe. In Switzerland she met a young Theosophical Society member, Gottfried de Purucker (1874–1942) for the first time. He had joined the Theosophical Society and met Judge who admitted him to the Esoteric Section without the usual probationary period. De Purucker had been to California a few years before and lived in San Diego in 1893, working on a ranch and leading study groups in the Secret Doctrine by the co-founder of the original Theosophical Society, Helena P. Blavatsky (1831–1891). De Purucker helped Tingley identify the land at Point Loma in San Diego for purchase for the UBTS project (PLST Archive). Meanwhile, the Theosophical “crusaders” traveled through the Middle East and sailed on to India. [Image at right] Early one morning near Darjeeling, Tingley evaded her companions and slipped off up into the foothills. She would return a day or so later, stating she had visited one of Blavatsky’s “Teachers” referring to the encounter as “life transforming” (Tingley 1926:155–162; and Tingley 1928). Some years later Tingley would reflect that her encounter with Blavatsky’s young Tibetan “Teacher” in India had given her the courage to continue with establishing and developing the Point Loma community and the gradual alleviation and reversal of symptoms of her chronic Addison’s kidney/adrenal disease. For Katherine Tingley this was a much needed and spiritually life-changing experience, that brought her the energy and motivation to bring her vision of a “White City in the West” into manifestation. debility, but from then until her death, she suffered a kind of emotional agitation at times when under stress. When it became severe, her office staff would call for Gottfried de Purucker to come, given his very calming influence on her in general, and his presence would usually resolve Tingley’s anxieties.

debility, but from then until her death, she suffered a kind of emotional agitation at times when under stress. When it became severe, her office staff would call for Gottfried de Purucker to come, given his very calming influence on her in general, and his presence would usually resolve Tingley’s anxieties. age and was never able to pinpoint the exact moment of her conversion. She married Walter Palmer on September 28, 1827. They had six children, three of whom lived to adulthood. The Palmers were active laypeople in the Methodist Episcopal Church and participated in numerous charitable activities. Both taught Sunday school classes. In 1839, Phoebe Palmer became the first woman to lead a class of both women and men in New York City.

age and was never able to pinpoint the exact moment of her conversion. She married Walter Palmer on September 28, 1827. They had six children, three of whom lived to adulthood. The Palmers were active laypeople in the Methodist Episcopal Church and participated in numerous charitable activities. Both taught Sunday school classes. In 1839, Phoebe Palmer became the first woman to lead a class of both women and men in New York City. churches and at camp meetings [Image at right], which generally were held outdoors in more rural areas. The content of her sermons was the same regardless of the location. Palmer did not ignore the goal of bringing sinners to Christ through sermons, which was historically the focus of revivals, but her emphasis was on holiness. By 1853 her schedule included Canada. Her labors there in 1857 resulted in more than 2,000 conversions and hundreds of Christians who claimed the baptism of the Holy Ghost or holiness (Palmer 1859:259). Her ministry there contributed to the general Prayer Revival of 1857–1858, which resulted in more than 2,000,000 converts in the United States and the British Isles. Between 1859 and 1863, Palmer preached at fifty-nine locations throughout the British Isles (White 1986:241–42). At one meeting in Sunderland, 3,000 attended her services held over a period of twenty-nine days, with some people turned away. She reported 2,000 seekers there, including approximately 200 who experienced holiness under her preaching (Wheatley 1881:355, 356). Between 1866 and 1870 she held services throughout the United States and eastern Canada (Raser 1987:69–70). At a camp meeting in Goderich, Canada in 1868, about 6,000 gathered to hear her preach (Wheatley 1881:445, 415). Palmer continued to accept preaching engagements until shortly before her death. Overall, she preached before hundreds of thousands of people at more than 300 camp meetings and revivals.

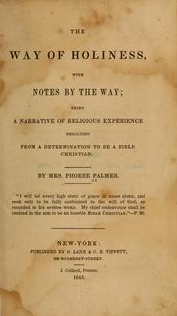

churches and at camp meetings [Image at right], which generally were held outdoors in more rural areas. The content of her sermons was the same regardless of the location. Palmer did not ignore the goal of bringing sinners to Christ through sermons, which was historically the focus of revivals, but her emphasis was on holiness. By 1853 her schedule included Canada. Her labors there in 1857 resulted in more than 2,000 conversions and hundreds of Christians who claimed the baptism of the Holy Ghost or holiness (Palmer 1859:259). Her ministry there contributed to the general Prayer Revival of 1857–1858, which resulted in more than 2,000,000 converts in the United States and the British Isles. Between 1859 and 1863, Palmer preached at fifty-nine locations throughout the British Isles (White 1986:241–42). At one meeting in Sunderland, 3,000 attended her services held over a period of twenty-nine days, with some people turned away. She reported 2,000 seekers there, including approximately 200 who experienced holiness under her preaching (Wheatley 1881:355, 356). Between 1866 and 1870 she held services throughout the United States and eastern Canada (Raser 1987:69–70). At a camp meeting in Goderich, Canada in 1868, about 6,000 gathered to hear her preach (Wheatley 1881:445, 415). Palmer continued to accept preaching engagements until shortly before her death. Overall, she preached before hundreds of thousands of people at more than 300 camp meetings and revivals. synonyms for holiness, such as sanctification, full salvation, promise of the Father, entire consecration, and perfect love. Her first book, The Way of Holiness with Notes by the Way (1843), [Image at right] was her spiritual autobiography that provided a roadmap for achieving holiness. Based on her own pursuit of holiness she explained a “shorter way,” which consisted of three steps: consecration, followed by faith, and then testimony.

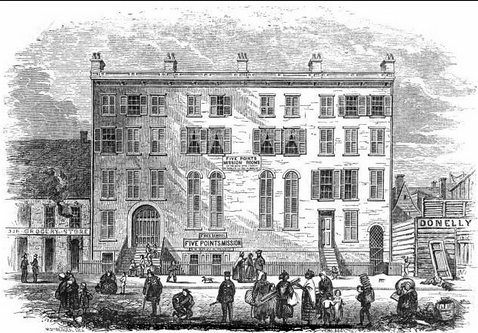

synonyms for holiness, such as sanctification, full salvation, promise of the Father, entire consecration, and perfect love. Her first book, The Way of Holiness with Notes by the Way (1843), [Image at right] was her spiritual autobiography that provided a roadmap for achieving holiness. Based on her own pursuit of holiness she explained a “shorter way,” which consisted of three steps: consecration, followed by faith, and then testimony. holiness believers engaged in activities that exhibited God’s love to those around them. This expression of social Christianity motivated by God’s love has become known as social holiness. It reflected Palmer’s emphasis on the responsibility of holiness adherents to be useful. Her ministry in the slums of New York City modeled social holiness. A notable example was her prominent role in founding the Five Points Mission in 1850 in lower Manhattan where the worst slums in New York City converged. Committed to addressing both the spiritual and physical needs of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, the Mission became one of the first settlement houses in the United States with a chapel, schoolrooms, and housing for twenty families (Raser 1987, 217).

holiness believers engaged in activities that exhibited God’s love to those around them. This expression of social Christianity motivated by God’s love has become known as social holiness. It reflected Palmer’s emphasis on the responsibility of holiness adherents to be useful. Her ministry in the slums of New York City modeled social holiness. A notable example was her prominent role in founding the Five Points Mission in 1850 in lower Manhattan where the worst slums in New York City converged. Committed to addressing both the spiritual and physical needs of the neighborhood’s inhabitants, the Mission became one of the first settlement houses in the United States with a chapel, schoolrooms, and housing for twenty families (Raser 1987, 217). had six children (George, Benjamin, Jr., John, Jane, Sammy and Rebecca) (Newport 2006 :117). The Rodens joined a Seventh-day Adventist church at Kilgore, Texas in 1940. They were fully committed to the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist prophet

had six children (George, Benjamin, Jr., John, Jane, Sammy and Rebecca) (Newport 2006 :117). The Rodens joined a Seventh-day Adventist church at Kilgore, Texas in 1940. They were fully committed to the teachings of the Seventh-day Adventist prophet  Israel during the next several years trying to achieve this goal. They created a pilot settlement at Amirim, which Lois directed. But the group as a whole never moved there (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:199). Whereas Ben was quiet, Lois was characterized as “exceptionally dynamic and [the leader of] the group for a number of years” (Newport 2006:115, 136).

Israel during the next several years trying to achieve this goal. They created a pilot settlement at Amirim, which Lois directed. But the group as a whole never moved there (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:199). Whereas Ben was quiet, Lois was characterized as “exceptionally dynamic and [the leader of] the group for a number of years” (Newport 2006:115, 136). published a mimeographed three-part study entitled By His Spirit (Roden 1980). The group secured an offset press, and in December 1980 she launched SHEkinah, [Image at right] a regularly published journal for disseminating her teaching (Roden and Doyle 1980–1983). She, along with Clive Doyle as co-editor and printer, searched newspapers, popular magazines and academic publications for articles that explored the ideas of the feminine character of God and the ordination of women. Some mainline Protestant denominations had begun ordaining women in the 1950s, and many more denominations began ordaining women as ministers in the 1970s. Meanwhile, feminist scholars studying the early Christian churches found evidence for belief in the feminine character of God and the existence of female clergy among early Christian churches.

published a mimeographed three-part study entitled By His Spirit (Roden 1980). The group secured an offset press, and in December 1980 she launched SHEkinah, [Image at right] a regularly published journal for disseminating her teaching (Roden and Doyle 1980–1983). She, along with Clive Doyle as co-editor and printer, searched newspapers, popular magazines and academic publications for articles that explored the ideas of the feminine character of God and the ordination of women. Some mainline Protestant denominations had begun ordaining women in the 1950s, and many more denominations began ordaining women as ministers in the 1970s. Meanwhile, feminist scholars studying the early Christian churches found evidence for belief in the feminine character of God and the existence of female clergy among early Christian churches. to meet the needs of her day. Victor Houteff [Image at right] established the style of leadership practiced among the Davidians/Branch Davidians. He set forth the organization of the General Association of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists in a constitution he called The Leviticus (Houteff 1943). In it he was named the president; the other executive officers ( vice president, treasurer and secretary ) were family members and one close associate who held office only as long as they were approved by the president. Following Houteff’s lead, Ben Roden also composed a Leviticus for the General Association of the Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists.

to meet the needs of her day. Victor Houteff [Image at right] established the style of leadership practiced among the Davidians/Branch Davidians. He set forth the organization of the General Association of the Davidian Seventh-day Adventists in a constitution he called The Leviticus (Houteff 1943). In it he was named the president; the other executive officers ( vice president, treasurer and secretary ) were family members and one close associate who held office only as long as they were approved by the president. Following Houteff’s lead, Ben Roden also composed a Leviticus for the General Association of the Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists. challenges to her leadership from male competitors. First, her son George [Image at right] was a rival throughout her years of prophetic leadership. He offered both gender and theological arguments to support his claim to succeed his father as prophet; failing that, he resorted to force. He was mentally unstable and violent, carrying a gun on the Mount Carmel grounds and into the church and threatening people (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:53–54). Because of fear of George Roden’s violence, the majority of the Branch Davidians, along with their new leader

challenges to her leadership from male competitors. First, her son George [Image at right] was a rival throughout her years of prophetic leadership. He offered both gender and theological arguments to support his claim to succeed his father as prophet; failing that, he resorted to force. He was mentally unstable and violent, carrying a gun on the Mount Carmel grounds and into the church and threatening people (Doyle with Wessinger and Wittmer 2012:53–54). Because of fear of George Roden’s violence, the majority of the Branch Davidians, along with their new leader to live there while her son George took control of the property. She died on November 10, 1986 at age seventy, and her body was transported to Israel for burial. George Roden lost control of the Mount Carmel property to Koresh’s Branch Davidians in 1988 while George was imprisoned for threatening a judge. He subsequently killed a man and spent the rest of his years in a state mental hospital.

to live there while her son George took control of the property. She died on November 10, 1986 at age seventy, and her body was transported to Israel for burial. George Roden lost control of the Mount Carmel property to Koresh’s Branch Davidians in 1988 while George was imprisoned for threatening a judge. He subsequently killed a man and spent the rest of his years in a state mental hospital. Ellen Bracewell, was a nanny for the local gentry and her father, Bruce Bracewell, was a tradesman and interior decorator for great manor homes in England. His ancestors had been weavers. Olga loved reading, showed an early talent in music, and possessed a clear and pure soprano voice. She attended various schools in the suburbs of Birmingham until the age of fourteen when she won a scholarship to Aston Pupil Teachers’ Centre for three years, intending to become a teacher.

Ellen Bracewell, was a nanny for the local gentry and her father, Bruce Bracewell, was a tradesman and interior decorator for great manor homes in England. His ancestors had been weavers. Olga loved reading, showed an early talent in music, and possessed a clear and pure soprano voice. She attended various schools in the suburbs of Birmingham until the age of fourteen when she won a scholarship to Aston Pupil Teachers’ Centre for three years, intending to become a teacher. understanding, Charles Sydney McGaffin, who after his death became her spiritual partner working with her from the life beyond death.

understanding, Charles Sydney McGaffin, who after his death became her spiritual partner working with her from the life beyond death. recounted in Between Time and Eternity, these came entirely unsought, and at first she was uncomfortable with them. It was only in her later years that she spoke of them to friends, and compiled her spiritual records for distribution to acquaintances who expressed interest. By this time such experiences were so extensive that she simply accepted their unusualness, and hoped they would be of help to others.

recounted in Between Time and Eternity, these came entirely unsought, and at first she was uncomfortable with them. It was only in her later years that she spoke of them to friends, and compiled her spiritual records for distribution to acquaintances who expressed interest. By this time such experiences were so extensive that she simply accepted their unusualness, and hoped they would be of help to others. frequently, on almost a or weekly basis. Some of Olga’s most significant visions are described in her own words on a website containing her self-published writings: the story of the psychic vase and its shattering; a viewing of the panorama of religions throughout the ages; an experience of the Cosmic Christ as Osiris in the Great Pyramid of Giza; an out-of-body tour of the Church of Christ of the Future; an account of the Temple of God Consciousness; and her receiving of third-eye vision (“The Communion Service” n.d.).

frequently, on almost a or weekly basis. Some of Olga’s most significant visions are described in her own words on a website containing her self-published writings: the story of the psychic vase and its shattering; a viewing of the panorama of religions throughout the ages; an experience of the Cosmic Christ as Osiris in the Great Pyramid of Giza; an out-of-body tour of the Church of Christ of the Future; an account of the Temple of God Consciousness; and her receiving of third-eye vision (“The Communion Service” n.d.). scrap of paper “containing an account of a man in England who was preaching that the Earth would be consumed in about thirty years” (White 1915:21). She would later recount that she was so “seized with terror” after reading the paper that she “could scarcely sleep for several nights, and prayed continually to be ready when Jesus came” (White 1915:22). In December of the same year, she was hit in the face by a stone thrown by a schoolmate “angry at some trifle” and was so badly injured that she “lay in a stupor for three weeks” (White 1915:17, 18). She was a shy, intense, and spiritual child, and these two events focused her attention on the destiny of her soul, especially as her injuries forced the formerly strong student to withdraw from school and spend her days in bed shaping crowns for her father’s hat-making business.