Scientology and the Visual Arts

VISUAL ARTS TIMELINE

1911 (March 13): Lafayette Ron Hubbard was born in Tilden, Nebraska.

1946 (March 14): Claude Sandoz was born in Zurich, Switzerland.

1948 (October 8): Gottfried Helnwein was born in Vienna, Austria.

1950 (May 9): Hubbard published Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health.

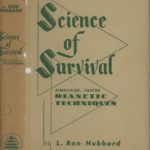

1951 (August 1): Hubbard published Science of Survival, which included a section about aesthetics and the visual arts.

1953 (November 12): Carl-W. Röhrig was born in Munich, Germany.

1965 (August 30): Hubbard published his first technical bulletin of the “Art” series.

1977 (September 26): Hubbard published his technical bulletin on “Art and Communication.”

1984 (February 26): Hubbard published his technical bulletins on “Colors,” and on “Art and Integration,” where he presented his theory of the mood lines.

1986 (January 24): Hubbard died in Creston, California.

1991: The posthumous book Art, collecting Hubbard’s technical bulletins on the arts, was published.

2013 (July 24-October 13): A retrospective on the art of Helnwein at the Albertina Museum in Vienna attracted 250,000 visitors.

2013 (October 6): The renovated Flag Building of the Church of Scientology was dedicated in Clearwater, Florida. It includes sixty-two sculptures illustrating the basic concepts of Scientology.

VISUAL ARTS TEACHINGS/DOCTRINES

Lafayette Ron Hubbard (1911-1986) [Image at right] founded Dianetics and Scientology,  which represent two distinct phases of his thought. Dianetics, first presented by Hubbard in 1950, deals with the mind, and studies how it receives and stores images. Scientology focuses on the entity who looks at the images stored in the mind. Mind for Scientology has three main parts. The analytical mind observes and remembers data, stores their pictures as mental images, and uses them to take decisions and promote survival. The reactive mind records mental images at times of unconsciousness, incidents, or pain, and stores them as “engrams.” They are awakened and reactivated when similar circumstances occur, creating all sort of problems. The somatic mind, directed by the analytical or reactive mind, translates their inputs and messages on the physical level. Dianetics aims at freeing humans from engrams, helping them achieving the status of “clear.”

which represent two distinct phases of his thought. Dianetics, first presented by Hubbard in 1950, deals with the mind, and studies how it receives and stores images. Scientology focuses on the entity who looks at the images stored in the mind. Mind for Scientology has three main parts. The analytical mind observes and remembers data, stores their pictures as mental images, and uses them to take decisions and promote survival. The reactive mind records mental images at times of unconsciousness, incidents, or pain, and stores them as “engrams.” They are awakened and reactivated when similar circumstances occur, creating all sort of problems. The somatic mind, directed by the analytical or reactive mind, translates their inputs and messages on the physical level. Dianetics aims at freeing humans from engrams, helping them achieving the status of “clear.”

Dianetics, however, left open the question of who, exactly, is the subject continuously observing the images stored in the mind. To answer this question, Hubbard introduced Scientology and moved from psychology to metaphysics and religion. At the core of Scientology’s worldview, there is a gnostic narrative. In the beginning, there were the “thetans,” pure spirits who created MEST (matter, energy, space, and time), largely for their own pleasure. Unfortunately, incarnating and reincarnating in human bodies, the thetans came to forget that they had created the world, and believed that they were the effect rather than the cause of physical universe. Their level of “theta,” i.e. of creative energy, gradually decreased and, as they kept incarnating as humans, the part of mind known as the reactive mind took over.

The more the thetan believes itself to be the effect, rather than the cause, of the physical universe, the more the reactive mind exerts its negative effects, and the person is in a state of “aberration.” This affects the Tone Scale, showing the emotional tones a person can experience, and the levels of ARC (Affinity – Reality – Communication). Affinity is the positive emotional relationship we establish with others. Reality is the agreement we reach with others about how things are. Communication is the most important part of the triangle: through it, we socially construct reality and, once reality is consensually shared, we are able to generate affinity.

Hubbard was familiar with the artistic milieus as a successful writer of fiction. However, he struggled for years on how to integrate an aesthetic and a theory of the arts into his system.  In 1951, Hubbard wrote that “there is yet to appear a good definition for aesthetics and art” (Hubbard 1976a:129). In the same year, he dealt with the argument in Science of Survival, one of his most important theoretical books. [Image at right] He returned often to the arts, particularly in seventeen articles included in technical bulletins he published from 1965 to 1984, which formed the backbone of the 1991 book Art, published by Scientology after his death (Hubbard 1991).

In 1951, Hubbard wrote that “there is yet to appear a good definition for aesthetics and art” (Hubbard 1976a:129). In the same year, he dealt with the argument in Science of Survival, one of his most important theoretical books. [Image at right] He returned often to the arts, particularly in seventeen articles included in technical bulletins he published from 1965 to 1984, which formed the backbone of the 1991 book Art, published by Scientology after his death (Hubbard 1991).

In Science of Survival, Hubbard explained that “many more mind levels apparently exist above the analytical level.” Probably “immediately above” the analytical mind, something called the “aesthetic mind” exists. Aesthetics and the aesthetic mind, Hubbard admitted, “are both highly nebulous” subjects. In general, the aesthetic mind is the mind that “deals with the nebulous field of art and creation.” And “the aesthetics have very much to do with the tone scale” (Hubbard 1951:234-36).

One might expect that the aesthetic mind would be incapable of functioning until most engrams have been eliminated and the state of clear has been reached. However, Hubbard claimed that it is not so. “It is a strange thing, he wrote, that the shut-down of the analytical mind and the aberration of the reactive mind may still leave in fairly good working order the aesthetic mind.” “The aesthetic mind is not much influenced by the position on the tone scale,” although “it evidently has to employ the analytical, reactive, and somatic minds in the creation of art and art forms” (Hubbard 1951:234).

Being “a person of great theta,” as artists often are, is also a mixed blessing. Hubbard explains that “a person of great theta endowment picks up more numerous and heavier locks and secondaries than persons of smaller endowment” (Hubbard 1951:235). Locks and secondaries are mental image pictures in which we are reminded of engrams. They would not exist without the engrams, but they may be very disturbing.

Hubbard claimed that, even before Scientology explained these phenomena, they were obvious enough to be noticed but were often misinterpreted. Many believed that it was normal, if not “absolutely necessary,” for an artist to be “neurotic.” “Lacking the ability to do anything about neurosis, like Aesop’s fox who had no tail and tried to persuade the other foxes to cut theirs off, frustrated mental pundits glorified what they could not prevent or cure.” The dysfunctional artist was hailed as a counter-cultural hero. Being “crazy” was regarded as typical of the good artist (Hubbard 1951:235).

Not so, Hubbard argued. Going down the tone scale is not good for anybody, and is not good for artists either. It is a dangerous misconception, according to Hubbard, to believe that “when an artist becomes less neurotic, he becomes less able.” Regrettably, our world has programmed the artists by widely inculcating these false ideas. The consequence is that many artists “seek to act in their private and public lives in an intensely aberrated fashion in order to prove that they are artists” (Hubbard 1951:238). Scientology, Hubbard promised, may “take a currently successful but heavily aberrated artist and (…) bring him [sic] up the tone scale” (Hubbard 1951:235). Not only will the artist be happier as a human being, he or she will also become a better artist.

Hubbard’s vision of the arts, as proposed in Science of Survival, is also crucial for Scientology’s social program. “The artist, Hubbard wrote, has an enormous role in the enhancement of today’s and the creation of tomorrow’s reality.” In fact, art operates “in advance of science” and “the elevation of a culture can be measured directly by the numbers of its people working in the field of aesthetics.” “A culture is only as great as its dreams, and its dreams are dreamed by artists” (Hubbard 1951:237-39).

Totalitarian states, Hubbard added, are the enemies of the artists, while pretending to be their friends, as they try to control them through state subsidies. Democratic governments, in principle, should not have these problems, but they run, according to Hubbard, a different risk. They “are prone to overlook the role of the artist in the society.” In the United States, he exemplified, as soon as artistic success is achieved, excessive taxes discourage the artist from further production. Hubbard proposed a tax reform with incentives for the artists. The reasons for this proposed reform were not merely economic, and were connected to Hubbard’s key idea that the prosperity of a society depends from the amount of circulating theta. Without enough theta, the reactive mind would dominate culture itself. “The artist injects the theta into the culture, and without that theta the culture becomes reactive” (Hubbard 1951:237-39).

Science of Survival also presents Hubbard’s view of the history of Western art. “In the early days of Rome, art was fairly good.” Christianity revolted against the Romans, and had one good reason for its revolt, “Roman disregard for human life.” However, those who revolt always run the risk of being dominated by the reactive mind. It thus happened, Hubbard believed, that Christianity fell into a “reactive computation” and came to regard everything Roman as negative, including the art. Happily, “the Catholic Church recovered early and began to appreciate the artist.” However, the old anti-Roman and, consequently, anti-artistic prejudice resurfaced with Protestantism and eventually came to the United States. “Puritanism and Calvinism,” according to Hubbard, “revolted against pleasure, against beauty, against cleanliness, and against many other desirable things” (Hubbard 1951:238).

The next step was a revolt against the revolt. In modern times, artists revolted against the Protestant and Puritan revolt against the classics and the arts. The problem was that, again, the reactive mind took over, and artists renounced everything Protestant, if not everything Christian, including morality. Being a good artist came to be “commonly identified with being loose-moraled, wicked, idle and drunken, and the artist, to be recognized, tried to live up to this role” (Hubbard 1951:238-39). This had a direct and negative impact on society. “When the level of existence of the artist becomes impure, so becomes impure the art itself, to the deterioration of the society. It is a dying society indeed into which can penetrate totalitarianism” (Hubbard 1951:239).

Hubbard concluded his discussion of aesthetics in Science of Survival noting that “there may be many levels of mind above the aesthetic mind” but we do know a lot about them. Therefore, “no attempt to classify any level of mind alertness above the level of the aesthetic mind will be made beyond stating that these mind levels more and more seem to approach an omniscient status” (Hubbard 1951:240). He mentioned, however, among the possible superior levels “a free theta mind, if such things exist” (Hubbard 1951:25). This notion would become central for the subsequent development in Scientology of the notion of “operating thetan,” a state where the thetan finally recovers his native abilities.

Hubbard continued his study of art after Science of Survival through writings that later would be collected  in his posthumously published book Art (Hubbard 1991). [Image at right] On August 30, 1965, he issued a technical bulletin that was quite important for his theory of art (Hubbard 1976b:83-85). Hubbard explained that it was now fifteen years since he had started considering how to “codify” knowledge about art and announced that “this [the “codification” of aesthetic theory] has now been done” (Hubbard 1976b:83).

in his posthumously published book Art (Hubbard 1991). [Image at right] On August 30, 1965, he issued a technical bulletin that was quite important for his theory of art (Hubbard 1976b:83-85). Hubbard explained that it was now fifteen years since he had started considering how to “codify” knowledge about art and announced that “this [the “codification” of aesthetic theory] has now been done” (Hubbard 1976b:83).

At first, art “seemed to stand outside the field of Dianetics and Scientology.” Hubbard, however, was not persuaded by this conclusion and eventually “made a breakthrough.” He realized that art and communication are closely connected. In fact, “ART is a word which summarizes THE QUALITY OF COMMUNICATION.” (Hubbard 1976b:83, capitals in original). Scientology had already elaborated certain “laws” about communication. Now, they should be applied to the arts.

In 1965, Hubbard was ready to propose three axioms about art. The first was that “too much originality throws the audience into unfamiliarity and therefore disagreement.” Communication, in fact, includes “duplication.” If the audience is totally unable to replicate the experience, it would not understand nor appreciate the work of art. The second axiom taught that “TECHNIQUE should not rise above the level of workability for the purpose of communication.” The third maintained that “PERFECTION cannot be attained at the expense of communication” (Hubbard 1976b:83, capitals in original).

Hubbard believed that his approach to aesthetics was new with respect to both classic and contemporary theories of art. The latter emphasized “originality,” to the point that audiences were often surprised by the artists – but, Hubbard maintained, not persuaded. The former sought perfection through technique. But, Hubbard insisted, “one should primarily seek communication with it [art] and then perfect it as far as reasonable” (Hubbard 1976b:84). Often, the artist should be prepared to lower the level of perfection to allow communication to flow.

“Art for art’s sake”, Hubbard argues, always failed because it was “attempted perfection without communicating.” We become artists when we learn how to communicate. Except in very rare cases, this does not come naturally nor is achieved overnight. Normally, one becomes an artist gradually, reflecting on past failures to communicate. These failures are, in fact, engrams, and artists should be “rehabilitated” through Dianetics just as anybody else, yet considering that they have specific engrams of their own. In fact, “due to the nature of the Reactive Mind, full rehabilitation [of the artists] is achieved only through releasing and clearing.” (Hubbard 1976b:83-85)

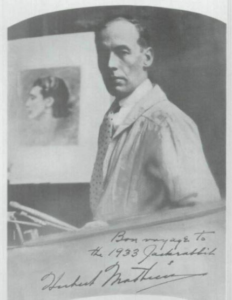

When the thetan understands himself as the cause rather than the effect of the physical reality, he (the thetan is always referred to by Hubbard as male, although women are incarnated thetans  too) perceives the world in a new way. If hemasters the appropriate technique, he is also able to produce art with a very high communication potential. On what role technique exactly plays, Hubbard mentioned in a bulletin of July 29, 1973 his discussions with “the late Hubert Mathieu” (Hubbard 1991:16). Although some who later wrote about Hubbard were unable to identify him or speculated he was a fictional character, in fact Mathieu (1897-1954) was a distinguished South Dakota illustrator and artist [Image at right], who worked for magazines Hubbard was familiar with.

too) perceives the world in a new way. If hemasters the appropriate technique, he is also able to produce art with a very high communication potential. On what role technique exactly plays, Hubbard mentioned in a bulletin of July 29, 1973 his discussions with “the late Hubert Mathieu” (Hubbard 1991:16). Although some who later wrote about Hubbard were unable to identify him or speculated he was a fictional character, in fact Mathieu (1897-1954) was a distinguished South Dakota illustrator and artist [Image at right], who worked for magazines Hubbard was familiar with.

Based inter alia on the ideas of Mathieu, Hubbard concluded that in the arts communication (the end) is more important than technique (the means), but technique is not unimportant. Artists who are well-trained are able to communicate in different styles, including the non-figurative, and the audience understands intuitively that they are real artists. Perceiving the world and representing it from the superior viewpoint of the thetan is not enough. One should be able to communicate this to the audience, which however should be invited to “contribute part of the meaning” (Hubbard 1991: 91) This is precisely the difference between fine art and mere illustration, where little is left to the audience’s own contribution.

Communication is achieved through integration, or combination into an integral whole of elements such as perspective, lines, colors, and rhythm. Hubbard emphasized “mood lines,” i.e. abstract line forms that influence the audience’s emotional response. Vertical lines communicate drama and inspiration, horizontal lines, happiness and calm, and so on (Hubbard 1991:76-77). There are several systems of mood lines described in manuals for artists. Scientology uses the one developed by visionary landscape architect John Ormsbee Simonds (1913-2005). Simonds’ theory of form was influenced by Zen Buddhism and by Anthroposophical theories he was exposed to through his mentor at Harvard, Marcel Breuer (1902-1981), formerly of the Bauhaus. Another common tool Hubbard recommended to artists, the color wheel, was promoted in his times through references to market surveys, but in fact had been first used in a different context by Robert Fludd (1574-1637) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Like many Theosophists (and market researchers), Hubbard believed that colors correspond to specific emotional states.

NOTABLE MEMBER ARTISTS

Becker Mirlach, Petra (b. 1944). German painter.

Bennish, Gracia (b. 1943). American painter and photographer.

Collins, Leisa (b. 1958). American painter.

Díaz-Rivera, Susana (b. 1957). Mexican painter.

Duke, Renée (1927-2011). American painter.

Escallon, Natalia (b 1985). Colombian painter and photographer.

Farina, Franco (b. 1957). Italian painter.

Findlay, Beatrice (b. 1941). Canadian painter, currently residing in Brooklyn, New York.

Gáll, Gregor (b. 1957). Hungarian sculptor.

Galli, Eugenio (b. 1951). Italian painter.

Green Peter (b. 1945). American painter.

Hancock, Houston (b. 1943). American painter.

Hanson, Erin (b. 1981). American painter.

Helnwein, Gottfried (b. 1948). Austrian painter and performance artist.

Helnwein, Mercedes (b. 1979). Austrian-born American painter and writer.

Hepner, Pomm (b. 1956). American painter.

Holl Hunt, Pamela (b. 1945). English painter.

Hubbard, Arthur Conway (b. 1958). American painter, son of Scientology founder, L. Ron Hubbard.

Hunter, Madison (b. 1989). American sculptor.

Kelly, Carolyn (1945-2017). American cartoonist and artist, daughter of well-known American cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913-1973), the creator of Pogo.

Mirlach, Max (b. 1944). German painter.

Munro, Ross (b. 1948). Canadian painter.

Prager, Vanessa (b. 1984). American painter.

Röhrig, Carl-W. (b. 1953). German painter, currently residing in Switzerland.

Rose, Marlene (b. 1967). Glass sculptor.

Rotenberg, Jule (b. 1954). American sculptor.

Sandoz, Claude (b. 1946). Swiss painter.

Schoeller Robert (b. 1950). Austrian painter, currently residing in Clearwater, Florida.

Shereshevsky, Barry (b. 1942). American painter.

South, Randolph (“Randy,” aka Carl Randolph) (b. 1950). American painter.

Spencer, Joe (b. 1949). American painter.

Warren, Jim (b. 1949). American painter.

Wright, D. Yoshikawa (b. 1951). American sculptor.

Wunderer, Bia (b. 1943). German painter.

Zöllner, Waki (1935-2015). German painter and sculptor.

INFLUENCE ON ARTISTS

Among modern new religious movements, Scientology is unique for its conscious effort of transmitting its worldview to the artists, at the same time teaching them how to be more apt at communicating their art to their audiences, through its courses and seminaries taught in its Celebrity Centers. Yet, Scientology’s influence on artists is understudied. One of the  reasons lies in the attacks and discrimination some artists have received because of their association with Scientology, particularly in Germany. There, abstract painter and textile artist Bia Wunderer is one of the artists who had exhibitions cancelled because she was “exposed” as a Scientologist. This made some artists understandably reluctant to discuss their relationship with Scientology. However, in Germany, of all places, artists were involved in Scientology since its beginnings. When he died in 2015, painter and sculptor Waki Zöllner (1935-2015), who had joined Scientology in 1968, was the German with more years of Scientology training. [Image at right]

reasons lies in the attacks and discrimination some artists have received because of their association with Scientology, particularly in Germany. There, abstract painter and textile artist Bia Wunderer is one of the artists who had exhibitions cancelled because she was “exposed” as a Scientologist. This made some artists understandably reluctant to discuss their relationship with Scientology. However, in Germany, of all places, artists were involved in Scientology since its beginnings. When he died in 2015, painter and sculptor Waki Zöllner (1935-2015), who had joined Scientology in 1968, was the German with more years of Scientology training. [Image at right]

The most famous international artist who took Scientology courses for several years, starting in 1972, was the Austrian-born Gottfried Helnwein (b. 1948). He became increasingly involved in Scientology’s activities, with all his family, and was attacked by anti-cult critics, who promoted even a book against him (Reichelt 1997). This generated in turn court cases and Helnwein’s increasing reluctance to discuss his religious beliefs.

In 1975, Helnwein told Stuttgart’s Scientology magazine College that “Scientology has caused a consciousness explosion in me” (Helnwein 1975). In 1989, in an interview in Scientology’s Celebrity, Helnwein elaborated that Scientology offers to artists invaluable tools to survive in a world often hostile to them, but also gave him a “new viewpoint” and an understanding how “people would react to my art” (Helnwein 1989a:10-11).

American novelist William Burroughs (1914-1997) took several Scientology courses between 1959 and 1968. Later, he rejected Scientology as an organization, while maintaining an appreciation for its techniques. In 1990, he wrote an essay about Helnwein, calling him “a master of surprised recognition,” which he defined as the art “to show the viewer what he knows but does not know that he knows” (Burroughs 1990:3) In this sense, “surprised recognition” may also describe the moment when a thetan “remembers” his true nature.

Helnwein’s unique style and approach to reality, a “photorealism” where paintings often look as photographs (but aren’t), derive from multiple sources. Ultimately, however, we can perhaps see in Helnwein’s works an attempt to depict the world as a thetan sees it, finally realizing he is its creator.

Seen as it really is, the world is not always pleasant, and includes suppression and totalitarianism. Some of Helnwein’s most famous paintings include suffering children. Helnwein exposes there the society’s unacknowledged cruelty. But there is also hope. The artist is aware of Hubbard’s ideas about children as spiritual beings occupying young bodies. Armed with the technology, children can survive and defeat suppression.

Criticizing psychiatry’s abuses is a cause dear to Scientologists. In 1979, leading Austrian psychiatrist Heinrich Gross (1915-2005), who participated in the Nazi program for the euthanasia of mentally handicapped children, defended himself by stating that children were killed in a somewhat humane way, with poison. Helnwein reacted with a watercolor, Lives unworthy of being lived, depicting a child “humanely” poisoned by Gross.

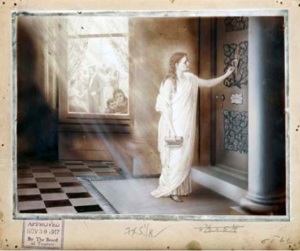

Helnwein also looked provocatively at Nazism and the Holocaust as an evil the German and Austrian society still refused to confront. In his famous Epiphany I (1996), the child may or may not be a young Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), but the Three Kings are clearly Nazi officers. [Image at right] Helnwein wants the audience, as Hubbard suggested, to contribute part of the meaning and to understand by itself.

to confront. In his famous Epiphany I (1996), the child may or may not be a young Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), but the Three Kings are clearly Nazi officers. [Image at right] Helnwein wants the audience, as Hubbard suggested, to contribute part of the meaning and to understand by itself.

Born in 1948, Helnwein reports how he escaped from Vienna’s suffocating conformism through comics, something the Austrian educational establishment did not approve of at that time. He maintains a fascination for Disney’s Donald Duck and the creator of several Donald stories, Carl Barks (1901-2000), who became his friend. Both Mickey Mouse and Donald are featured in Helnwein’s work. Barks, Helnwein wrote, created a “decent world where one could get flattened by steam-rollers and perforated by bullets without serious harm. A world in which the people still looked proper (..). And it was here that I met the man who would forever change my life – a man who (…) is the only person today that has something worthwhile saying – Donald Duck” (Helnwein 1989b:16). Perhaps, again, Barks’ Duckburg became a metaphor for Helnwein of the “clear” world created by a technology capable of restoring the thetans to their proper role. In 2013, Helnwein was honored by a great retrospective at Vienna’s Albertina, which attracted 250,000 visitors, a far cry from when the artist was discriminated as a Scientologist.

While Helnwein became reserved on his relationship with Scientology, other artists declared it openly. Scientology through its Celebrity Centers also created a community of artists, knowing and meeting each other across different countries, continents, and styles. Several Scientologist artists decided to live either in Los Angeles or in Clearwater, Florida, near the main centers of the Church of Scientology.

Scientologist artists do not share a single style, as is true for artists who are Theosophists or Catholics. For example, German-born Carl-W. Röhrig (1953-), currently residing in Switzerland, calls his art “fantastic realism” and is also influenced by fantasy literature, surrealism, and popular esotericism (von Barkawitz 1999), as evidenced by his successful deck of tarot cards  (Röhrig and Marzano-Fritz 1997). There are, however, common themes among Scientology artists, as evidenced in interviews I conducted between 2015 and 2016 with a number of them (the subsequent quotes, unless otherwise indicated, are from those interviews).

(Röhrig and Marzano-Fritz 1997). There are, however, common themes among Scientology artists, as evidenced in interviews I conducted between 2015 and 2016 with a number of them (the subsequent quotes, unless otherwise indicated, are from those interviews).

Röhrig is among the few Scientologist artists who included explicit references to Scientology doctrines in some of his paintings, including The Bridge (2009), i.e. the journey to become free from the effects of the reactive mind. [Image at right] Röhrig and other artists who are Scientologists, including the American Pomm Hepner and Randy South (aka Carl Randolph), also contributed murals to churches of Scientology around the world.

California Scientologist artist Barry Shereshevsky devoted several paintings to the ARC triangle. California sculptor D. Yoshikawa Wright moved “from Western to more Eastern thought,” rediscovering his roots, and finally found in Scientology something that, he says, “merges East and West.” About his Sculptural Waterfalls, he comments that the stone represents the thetan, the water the physical universe as motion, and their relationship the rhythm, the dance of life [Image at right]. Another Scientologist sculptor (and painter), the Italian Eugenio Galli, experiments with rhythm and motion through different abstract compositions all connected with the idea of “transcendence,” i.e. transcending our present, limited status.

more Eastern thought,” rediscovering his roots, and finally found in Scientology something that, he says, “merges East and West.” About his Sculptural Waterfalls, he comments that the stone represents the thetan, the water the physical universe as motion, and their relationship the rhythm, the dance of life [Image at right]. Another Scientologist sculptor (and painter), the Italian Eugenio Galli, experiments with rhythm and motion through different abstract compositions all connected with the idea of “transcendence,” i.e. transcending our present, limited status.

Artists who went through Scientology’s Art course all insisted on art as communication. Winnipeg-born New York abstract artist Beatrice Findlay told me that “art is communication, why the heck would you do it otherwise?” She also insisted that Hubbard  “never said abstract art communicated less” and had a deep appreciation of music, a form of abstract communication par excellence. Hubbard’s ideas about composition are translated by Findlay into peculiar abstract lines and color (Carasso 2003) [Image at right]. A similar abstract approach while other Scientologist artist apply the same principles to more traditional approach to landscape. They include the Italian Franco Farina, the Canadian Ross Munro, and the American Erin Hanson, whose depictions of national parks and other iconic American landscapes in a style she calls “Open Impressionism” won critical acclaim (Hanson 2014; Hanson 2016).

“never said abstract art communicated less” and had a deep appreciation of music, a form of abstract communication par excellence. Hubbard’s ideas about composition are translated by Findlay into peculiar abstract lines and color (Carasso 2003) [Image at right]. A similar abstract approach while other Scientologist artist apply the same principles to more traditional approach to landscape. They include the Italian Franco Farina, the Canadian Ross Munro, and the American Erin Hanson, whose depictions of national parks and other iconic American landscapes in a style she calls “Open Impressionism” won critical acclaim (Hanson 2014; Hanson 2016).

Pomm Hepner is both a professional artist and a senior technical supervisor at Scientology’s church in Pasadena, as well as a leader in Artists for Human Rights, an advocacy organization started by Scientologists. As Scientology taught her “on the spiritual world,” she evolved, she says, from “pretty things” to “vibrations,” from “a moment that exists to a moment I create… I can bring beauty to the world and no longer need to depend on the world bringing beauty to me.” By adopting the point of view of the thetan, she tried to “reverse” the relationship between the artist and the physical universe. A similar experience emerges in the artistic and literary career of Scientologist Renée Duke (1927-2011). Although she had painted before, she became a professional painter only later in life, after she had encountered Scientology (Duke 2012).

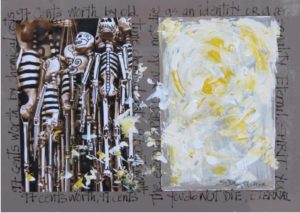

There is a difference between how Scientologist artists were discriminated against in Europe and  some mild hostility their beliefs received occasionally in the U.S. However, they all stated in my interviews that modern society is often disturbed by artists and tries to suppress them, singling out psychiatry as a main culprit, a recurring theme in Scientology. The Trick Cyclist by Randolph South depicts well-known psychiatrists and “was created to draw attention to the evil practice of psychiatry.” [Image at right] Most Scientologist artists share an appreciation of Helnwein, although they may be very far away from both his art and his persona. Some address the theme of suffering children with obvious Helnweinian undertones. The youngest child of L. Ron Hubbard, Arthur Conway Hubbard (1958-), himself became a painter and studied under Helnwein, although he also produced works in a different style. In some of his paintings, he used his own blood.

some mild hostility their beliefs received occasionally in the U.S. However, they all stated in my interviews that modern society is often disturbed by artists and tries to suppress them, singling out psychiatry as a main culprit, a recurring theme in Scientology. The Trick Cyclist by Randolph South depicts well-known psychiatrists and “was created to draw attention to the evil practice of psychiatry.” [Image at right] Most Scientologist artists share an appreciation of Helnwein, although they may be very far away from both his art and his persona. Some address the theme of suffering children with obvious Helnweinian undertones. The youngest child of L. Ron Hubbard, Arthur Conway Hubbard (1958-), himself became a painter and studied under Helnwein, although he also produced works in a different style. In some of his paintings, he used his own blood.

Pollution as a form of global suppression and Scientology’s mission to put an end to it are a main theme for Röhrig. Landscapes and cultures in developing countries are also in danger of being suppressed. This is a main theme in the work of Swiss Scientologist artist Claude Sandoz, who spends part of his time in the Caribbean, in Saint Lucia. Exhibitions of Sandoz’s works, which blends Caribbean and European themes and styles, [Image at right] took place in several Swiss museums (see Stutzer and Walser Beglinger 1994).

theme for Röhrig. Landscapes and cultures in developing countries are also in danger of being suppressed. This is a main theme in the work of Swiss Scientologist artist Claude Sandoz, who spends part of his time in the Caribbean, in Saint Lucia. Exhibitions of Sandoz’s works, which blends Caribbean and European themes and styles, [Image at right] took place in several Swiss museums (see Stutzer and Walser Beglinger 1994).

Some of those who took Scientology’s Art Course are “commercial” artists. The course told them that this is not a shame and hailed success as healthy. They believe that the boundary between commercial and fine art is not clear-cut. Some of them were encouraged to also engage in fine arts. Veteran Scientologist artist Peter Green claims he understood through Scientology that commercial artists are not “coin-operated artists,” but have their own way of communicating and presenting a message. Green manifested this approach in his iconic posters, such as a famous one of Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970). Green also contributed to horror comics magazines published by the Warren company in California, and keeps producing his successful Politicards, i.e. trading and playing cards with politicians (see Kelly 2011). He insists that you can “paint to live and remain sane. And in the end, you may live to paint too.” Randy South insisted that, even when working for advertising, artists may “perceive the physical universe” as “not overwhelming spirituality” but “vice versa.” He added that “Hubbard said that life is a game. I want to play the game, and it’s fun.”

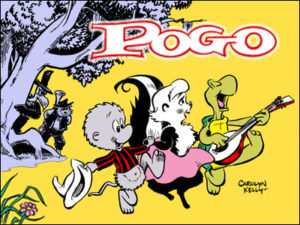

The portraits of another Scientologist artist, Robert Schoeller, are sold for commercial purposes, but he believes that “by painting somebody I make him spiritual.” In fact, there have been museum exhibitions of his portraits around the central theme of spirituality. Similar considerations may be  made for Jim Warren’s popular lithographs and Disney-related themes. Other Scientologist artists became photographers and cartoonists. Carolyn Kelly (1945-2017) was the daughter of well-known American cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913-1973), the creator of Pogo. She was a cartoonist and illustrator in her own right, and was among those who designed her father’s Pogo when the strip was shortly revived in the 1990s. [Image at right]

made for Jim Warren’s popular lithographs and Disney-related themes. Other Scientologist artists became photographers and cartoonists. Carolyn Kelly (1945-2017) was the daughter of well-known American cartoonist Walt Kelly (1913-1973), the creator of Pogo. She was a cartoonist and illustrator in her own right, and was among those who designed her father’s Pogo when the strip was shortly revived in the 1990s. [Image at right]

Some (but not all) Scientologist artists took an interest in popular esoteric discourse. Before meeting Scientology, Pomm Hepner, was exposed to Anthroposophy by studying at a Steiner school. Röhrig uses the Tarots as well as the Zodiac. He explains he doesn’t believe in the content of astrology or Tarot, as “they are effects and as a Scientologist you try to be cause,” but they provide a widely shared language and are “a very good tool to communicate.” Other Scientologist artists approach in a similar way Eastern spirituality. For instance, Marlene Rose’s glass sculptures often feature the Buddha. Rose is one of the artists who decided to live in Clearwater, Florida, near the Flag headquarters of the Church of Scientology. The area offers a favorable environment for artists working with glass and in April 2017 nearby St. Petersburg opened the Imagine Museum devoted to this artistic medium, with Marlene Rose featured in the opening exhibit.

“We were one hundred students doing the same [Scientology] course. Suddenly, the room took the most beautiful characteristics. Everything became magical. I became more me. The room did not  change but how I perceived it changed,” reported Susana Díaz-Rivera, a Mexican Scientologist painter. Several artists told how the “static” experience, which in Scientology language means realizing your nature as thetan, completely changed how they perceive the world. Then, “art is about duplicating what you perceive. Perception is communication,” as Yoshikawa Wright told me. Díaz-Rivera struggled to recapture and express this perception of herself as a thetan. She tried both painting [Image at right] and photographing in different locations, including Rome and Los Angeles, and using mirrors. “The spiritual part, she said, emerges through the mirrors.”

change but how I perceived it changed,” reported Susana Díaz-Rivera, a Mexican Scientologist painter. Several artists told how the “static” experience, which in Scientology language means realizing your nature as thetan, completely changed how they perceive the world. Then, “art is about duplicating what you perceive. Perception is communication,” as Yoshikawa Wright told me. Díaz-Rivera struggled to recapture and express this perception of herself as a thetan. She tried both painting [Image at right] and photographing in different locations, including Rome and Los Angeles, and using mirrors. “The spiritual part, she said, emerges through the mirrors.”

Scientology, the artists who attended its courses reported, offers to the artist a number of suggestions, aimed at “putting them back in the driver’s seat” (Peter Green) of their lives, exposing the “myth” of the dysfunctional, starving artist. Scientology also creates and cultivates a community of artists, and does more than offering practical advice. By interiorizing the gnostic narrative of the thetan, artists learn to perceive the physical universe in a different way. Then, they try to share this perception through communication, with a variety of different techniques and styles, inviting the audience to enhance their works with further meanings.

Sixty-two sculptures in the Grand Atrium of the new Flag Building in Clearwater, Florida, inaugurated in 2013, illustrate the fundamental concepts of Scientology. The fact that these concepts had to be  explained to the artists, none of them a Scientologist, is significant. Artists who are Scientologists normally are inspired by Scientology in their work, but prefer not to “preach” or illustrate its doctrines explicitly. On the other hand, although not realized by Scientologists, the Flag complex of sculptures is part and parcel of an art inspired by Hubbard and Scientology. [Image at right]

explained to the artists, none of them a Scientologist, is significant. Artists who are Scientologists normally are inspired by Scientology in their work, but prefer not to “preach” or illustrate its doctrines explicitly. On the other hand, although not realized by Scientologists, the Flag complex of sculptures is part and parcel of an art inspired by Hubbard and Scientology. [Image at right]

In 2008, the Los Angeles magazine Ange described the circle of young artists who are Scientologists, including painter and novelist Mercedes Helnwein (Gottfried Helnwein’s daughter) and promising abstract artist Vanessa Prager as the “first generation of casual Scientologists,” whose religious affiliation caused less controversy (Brown 2008). Visual arts seem to offer an ideal window to discuss the worldview and multiple influences of Scientology independently of the usual legal and other controversies.

IMAGES**

**All images are clickable links to enlarged representations.

Image #1: L. Ron Hubbard, portrait by Peter Green (1999).

Image #2: Cover of Science of Survival, 1951.

Image #3: Cover of L. Ron Hubbard posthumously published Art, 1991.

Image #4: Hubert Mathieu.

Image #5: Waki Zöllner.

Image #6: Gottfried Helnwein, Epiphany I (1996).

Image #7: Carl-W. Röhrig, The Bridge (2009).

Image #8: D. Yoshikawa Wright, Rain Circle, from the series Sculptural Waterfalls (2010).

Image #9: Beatrice Findlay, December Fog Runners (2015).

Image #10: Randolph South, The Trick Cyclist (2008).

Image #11: Claude Sandoz, Ixora II (Elvira Bach and Her Children) (1997-98).

Image #12: Pogo characters designed by Carolyn Kelly.

Image #13: Bones and the Eternal Spirit (2014), Susana Díaz-Rivera’s contribution to the exhibition Dialogue on Death at the Diocesan Museum of Gubbio, Italy, 2015. All the words in the painting are by L. Ron Hubbard.

Image #14: Part of the groups of sculptures The Eight Dynamics, The Flag Building, Clearwater, Florida.

REFERENCES

Brown, August. 2008. “The Radar People.” Ange, November. Accessed from http://digital.modernluxury.com/article/The+Radar+People/93054/10070/article.html on 26 March 2007.

Burroughs, William. 1990. “Helnwein’s Work.” P. 3 in Kindskopf, edited by Peter Zawrel, Vienna: Museum Niederösterreich.

Carasso, Roberta. 2003. Beatrice Findlay Runners/Landscapes. Santa Monica, CA: Bergamot Station Art Center.

Duke, Renée. 2012. Cocktails, Caviar and Diapers: A Woman’s Journey to Find Herself through Seven Countries, Six Children and a Dog. Charleston, SC: Alex Eckelberry.

Hanson, Erin. 2016. Open Impressionism, Volume II. San Diego, CA: Red Rock Fine Art.

Hanson, Erin. 2014. Open Impressionism: The Landscapes of Erin Hanson. San Diego, CA: Red Rock Fine Art.

Helnwein, Gottfried. 1989a. “Celebrity Interview of the Month: Fine Artist Gottfried Helnwein.” Celebrity 225:8-11.

Helnwein, Gottfried. 1989b. “Micky Maus unter dem roten Stern.” Zeitmagazin, April, 12-13.

Helnwein, Gottfried. 1975. Interview in College: Zeitschrift des Stuttgarter Dianetic College e.V., no. 12.

Hubbard, L. Ron. 1991. Art. Los Angeles: Bridge Publications.

Hubbard, L. Ron. 1976a. The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology. Volume I 1950-53, Copenhagen and Los Angeles: Scientology Publications.

Hubbard, L. Ron. 1976b. The Technical Bulletins of Dianetics and Scientology. Volume VI 1965-1969, Copenhagen and Los Angeles: Scientology Publications.

Hubbard, L. Ron. 1951. Science of Survival: Simplified, Faster Dianetic Techniques. Wichita, KS: The Hubbard Dianetic Foundation.

Kelly, Tiffany. 2011. “Political Satire is in the Cards.” Los Angeles Times, October 7. Accessed from http://www.latimes.com/tn-gnp-1007-green-story.html on 26 March 2017.

Reichelt, Peter. 1997. Helnwein und Scientology. Lüge und Verrat eine Organisation und ihr Geheimdienst. Mannheim, Germany: Brockmann und Reichelt.

Röhrig, Carl-W. and Francesca Marzano-Fritz. 1997. The Röhrig-Tarot Book. Woodside (California): Bluestar Communications.

Stutzer, Beat, and Annakatharina Walser Beglinger. 1994. Claude Sandoz. Ornamente des Alltags. Chur: Bündner Kunstmuseum

Von Barkawitz, Volker. 1999. The Future is Never Ending: The Phantastic [sic] Naturalism of Carl-W. Röhrig. Hamburg (Germany): CO-Art.

Post Date:

9 May 2017

1935. The title of her most well-known non-figurative work, Quarante Huit Quai d’Auteuil, refers to her address in Paris, where she started a lifelong friendship with Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). From the abstract experiments, however, Nicholson consistently returned to flowers. Later in life, she formed a close association with Chinese abstract painter Li Yuan-Chia (1929-1994). Under his influence, she experimented with prisms, producing a whole series of painted meditations about light, a symbol of Christ and of Divine Science dispelling the errors of the mortal mind. [Image at right]

1935. The title of her most well-known non-figurative work, Quarante Huit Quai d’Auteuil, refers to her address in Paris, where she started a lifelong friendship with Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian (1872-1944). From the abstract experiments, however, Nicholson consistently returned to flowers. Later in life, she formed a close association with Chinese abstract painter Li Yuan-Chia (1929-1994). Under his influence, she experimented with prisms, producing a whole series of painted meditations about light, a symbol of Christ and of Divine Science dispelling the errors of the mortal mind. [Image at right]