SAINT TERESA OF ÁVILA TIMELINE

1515 (March 28): Teresa Sánchez Cepeda y Ahumada was born to Alonso de Cepeda and his second wife, Beatriz de Ahumada.

1528 or 1529: Teresa’s mother died.

1531: Teresa’s father placed her as a boarder in the Augustinian convent, Our Lady of Grace.

1535: Teresa entered the Carmelite convent of the Incarnation in Ávila.

1536 (November 2): Teresa became a novice at Incarnation convent.

1537 (November 3): Teresa professed (took her final vows) at Incarnation. She left the convent due to a serious illness, during which time she fell into a coma for four days. On her way to Castellanos de la Cañada for treatment, she read Francisco de Osuna’s Third Spiritual Alphabet, her introduction to mental prayer.

1543: Teresa’s father died.

1553: Teresa experienced what was called her “reconversion” before an image of the crucified Christ (known as ecce homo).

1554: Teresa met Francisco Borgia, one of the most influential men in Spain, who became a Jesuit priest. Although many clerics doubted the authenticity of Teresa’s spiritual experiences, Borges believed they were valid

1556–1557: Teresa had several intense mystical experiences. She began confessing with Jesuits. She also had a famous vision known as the “transverberation.”

1558: Teresa met Pedro de Alcántara, a famous Franciscan friar and mystic.

1560: Teresa and some of her close friends began to entertain the possibility of founding a Carmelite convent that would adhere to the unmitigated (original) rule of the order.

1562 (August 24): Teresa founded the first Discalced Carmelite convent, Saint Joseph, in Ávila, Spain, which followed the unmitigated rule. (Although “discalced” literally means barefoot, the Sisters wore sandals.) Teresa finished the first draft of The Book of Her Life.

1563: Teresa received verbal permission to reside in the Saint Joseph of Ávila convent.

1564: Teresa completed the revised version of The Book of Her Life.

1567: The Carmelite general, Giovanni Battista Rossi, known as Juan Bautista Rubeo in Spain, gave Teresa patents (official permission) to found male and female monasteries. On August 15, a convent was founded in Medina del Campo. (Note that the words “monastery” and “convent” can refer to either male or female religious houses. These words are used interchangeably.)

1567: Teresa met the Spanish mystic John of the Cross.

1568: Teresa wrote the Constitutions of the order. On April 11, she founded a convent in Malagón, and on August 15, another in Valladolid.

1568 (November 28): John of the Cross and Antonio de Heredia founded the first Discalced Carmelite friary in Duruelo.

1569: Several more monasteries were founded: on May 14, in Toledo; on June 28, a female convent and on July 13, a male convent in Pastrana.

1570 (September 29): A female convent was founded in Salamanca.

1571 (January 25): A female convent was founded in Alba de Tormes. Teresa became prioress of the Medina del Campo convent, then was forced to become prioress of Incarnation. Teresa began to compose Concepts of the Love of God.

1573: Teresa finalized the text of Way of Perfection and began The Book of Foundations.

1574 (March 19): A female convent was founded in Segovia.

1575 (February 24): A female convent was founded in Beas. Teresa met Jerónimo Gracián, the Carmelite visitator. The struggle between Calced and Discalced Carmelites began.

1575 (May 29): A female convent was founded in Seville. At the General Chapter of the order at Piacenza, Italy, delegates decided that Teresa must retire to one convent and refrain from making further foundations (that is, establishing any more convents).

1576: Teresa left for the Carmelite convent in Toledo, where she remained until the following year. She wrote The Way of Visiting Convents.

1577: Teresa wrote The Interior Castle. She returned to Ávila at the end of July.

1577 (December 3–4): Calced Carmelites captured and imprisoned John of the Cross. On December 24, Teresa fell and broke her arm.

1578: Rubeo died. The papal Nuncio Felipe Sega put the Discalced Carmelites under the authority of the Calced.

1579: Sega withdrew the Discalced Carmelites from the control of the Calced.

1580 (February 2): A female convent was founded in Villanueva de la Jara. Teresa fell seriously ill. The female convent in Palencia was founded on December 29.

1581: The Calced and Discalced Carmelites became two separate provinces. The Discalced Constitutions were confirmed. On June 14, a female Discalced Carmelite convent was founded in Soria. Teresa was elected prioress of Saint Joseph convent in Ávila. The Constitutions were printed.

1582 (April 19): A female Discalced Carmelite convent was founded in Burgos. Ana de Jesús and John of the Cross made a foundation in Granada.

1582 (October 4 or 15): Teresa died in Alba de Tormes.

1622 (March 16): Pope Gregory XX canonized Saint Teresa of Ávila.

1970 (September 27): Pope Paul VI named Saint Teresa the first female Doctor of the Church.

BIOGRAPHY

Traditional biographies describe Saint Teresa of Ávila (known as Teresa de Jesús in the Spanish-speaking world) as an Old Christian (a Christian with no Jewish or Muslim ancestors) of patrician ancestry. For example, William Walsh claims that her father, Alonso Sánchez de Cepeda, was a nobleman and that “Teresa’s family, on both sides, boasted of limpieza de sangre, blood “clean” from any Moorish or Jewish taint” (Walsh 1943:4, 5). However, Teófanes Egido has produced ample documentation that Teresa’s paternal grandfather, Juan Sánchez, was a converso (convert from Judaism). Sánchez adopted the Catholic faith a decade before King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella (jointly ruling 1479–1516) issued the Alhambra Decree in 1492 ordering Jews in Spain either to leave or convert to Catholicism. However, in 1485, Sánchez was charged with backsliding into Jewish practices and avoided being burned at the stake by paying a hefty sum of money (Egido 1986:26). He then left his native Toledo for Ávila, where ambitious merchants like himself were making new lives for themselves (Bilinkoff 1989:53).

Successful conversos often sought to procure a position in society through a pleito de hidalguía, a petition for recognition as a gentleman. Sánchez won a pleito de hidalguía in 1500 and then secured an ejecutoria (patent of nobility), a legal document issued in the name of the king affirming a person’s Old Christian lineage and noble status. The patent was obviously fraudulent in Juan’s case. It must have offered Juan’s family insufficient protection because four of his sons, including Teresa’s father Alonso, began another pleito de hidalguía in 1519, when Teresa was four years old. Scholars have debated whether Teresa was aware of her Jewish origins. It was common for conversos to hide their ancestry from their children. Cathleen Medwick writes that if Teresa knew, it was “probably not through her father, a man invested in obliterating the past” (Medwick 1999:24). However, Teresa probably did know the truth, as she mentions the patents of nobility in a letter to her brother Lorenzo written on December 23, 1561 (Teresa 2001:36).

In 150 5, Alonso de Cepeda married Catalina del Peso, who bore him two children and then died in 1507. Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada was the third child and eldest daughter of Alonso and his second wife, Beatriz de Ahumada. Before Teresa was born, [Image at right] Beatriz had had two sons and then, after Teresa’s birth, five more sons and another daughter, Juana. It was the custom in large families for some children to take their father’s surname and others to take their mother’s. Teresa, who was named after her maternal grandmother, took her mother’s. After Beatriz died shortly after Juana’s birth in 1528, Teresa took the Virgin to be her mother, she writes in The Book of Her Life.

5, Alonso de Cepeda married Catalina del Peso, who bore him two children and then died in 1507. Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada was the third child and eldest daughter of Alonso and his second wife, Beatriz de Ahumada. Before Teresa was born, [Image at right] Beatriz had had two sons and then, after Teresa’s birth, five more sons and another daughter, Juana. It was the custom in large families for some children to take their father’s surname and others to take their mother’s. Teresa, who was named after her maternal grandmother, took her mother’s. After Beatriz died shortly after Juana’s birth in 1528, Teresa took the Virgin to be her mother, she writes in The Book of Her Life.

Nevertheless, by her own description, she was not a particularly devout child. She loved reading hagiographies, but many of these were adventure stories similar to novels of chivalry. Biographers have made much of an incident she describes in The Book of Her Life in which she and her brother Rodrigo decided to run away to Moorish lands to be martyred (Teresa 1987:55), but this seems to have been more of a lark than an act of true devotion. Teresa describes herself in Life as a rather frivolous adolescent, occupied with “conversations and vanities” (Teresa 1987:58). Her account of her early years reveals a shrewd, strong-willed young woman who knew how to get her own way.

A scandal involving one of Teresa’s male cousins prompted Don Alonso to place his daughter in the Augustinian convent of Our Lady of Grace as a boarder in 1531. At the time, Teresa had no intention of becoming a nun. However, under the guidance of Mother María Briceño, she changed her mind. She left the convent in 1532 due to illness, but then, despite her father’s objections, entered the Carmelite Convent of the Incarnation, in Ávila, in 1535. The Carmelite sisters followed what was called the mitigated rule: that is, they did not adhere to the strict policies dictated by the original friars of the order. For example, under the mitigated rule, nuns were allowed to leave the convent, while under the unmitigated rule, they were strictly cloistered. Although Incarnation was not lax by prevailing standards, it was more relaxed than Our Lady of Grace.

Shortly after profession of her vows on November 3, 1537, Teresa once again fell ill. Her father sent her to a famous healer in the nearby town of Becedas to be cured. On route, she visited her Uncle Pedro, who lent her his copy of The Third Spiritual Alphabet, by the Franciscan friar Francisco de Osuna (1497–1541). This book introduced her to recollection (turning inward to seek God in one’s own soul) and mental prayer (conversing with God without an established text). In Life, Teresa writes:

I did not know how to proceed in prayer or how to be recollected. And so I was

very happy with this book and resolved to follow that path with all my strength. . . . I

began to take time out for solitude, to confess frequently, and to follow that path,

taking the book for my master (Teresa 1987:66–67).

Although recollection had been practiced by Observant Franciscans (those who followed the unmitigated rule) since around 1470, after the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church viewed spiritual illumination unmediated by clergy, rite, or a sanctioned script as unorthodox. Teresa’s emphasis on interiority eventually caused her countless difficulties.

In 1537, when the healer in Becedas failed to cure Teresa, Don Alonso took her back to Ávila, where she fell into a coma that lasted four days. Eventually she returned to the Convent of the Incarnation, but instead of immersing herself in prayer, she was once again drawn into the social whirl of the community. Teresa was by nature an outgoing person and enjoyed the company of the Sisters. However, she began to feel that Christ was judging her harshly. She plunged into a period of spiritual struggle and suffered long bouts of aridity, or dryness, during which she could not pray.\

Teresa’s father died in 1545, leaving Teresa and her brother-in-law Martín de Guzmán as coexecutors of his will. A series of lawsuits against the estate followed, which provided Teresa with excellent negotiating experience for the future. In 1553, when Teresa’s younger sister Juana married Juan de Ovalle, it was Teresa who arranged the marriage contract.

During these years, Teresa’s spiritual experiences intensified. [Image at right] In 1553, she had a powerful vision before an ecce homo (image of the crucified Christ), which has come to be known as her “reconversion.” Distressed at the thought that her behavior might be offensive to Jesus, who had sacrificed so much for humanity, she threw herself down and began to sob. The incident marked a spiritual awakening, after which Teresa was able to practice recollection and mental prayer. Several more mystical experiences followed. However, not all of her confessors took her seriously: “They were all against me; some, it seemed, made fun of me when I spoke of the matter, as though I were inventing it; others said my experience was clearly from the devil” (Teresa 1987:220). Her critics were so severe that Teresa herself began to fear that her visions and locutions came from the devil.

Guiomar de Ulloa, a rich widow with two daughters at Incarnation, introduced Teresa into her circle of friends, which included the spiritual avant-garde of Ávila (people who were knowledgeable about sophisticated prayer practices). Doña Guiomar was also friendly with the recently-formed Society of Jesus(the Jesuits) who founded a school in Ávila in 1554. At her urging, Teresa began to confess with a young Jesuit priest, Diego de Cetina (1531–1568), who believed her reports of spiritual experiences. When another Jesuit, Francisco de Borja (1510–1527), came to town, he too reassured her that her experiences came from God. Borja was a powerful and influential man whose favor enabled Teresa to gain credibility among the Jesuits. Shortly afterward, she began to confess with yet another Jesuit, Juan de Prádanos (1529–1597), under whose guidance Teresa made considerable spiritual progress. She also met Pedro de Alcántara (1499–1562), the renowned mystic, who encouraged her as well.

guidance Teresa made considerable spiritual progress. She also met Pedro de Alcántara (1499–1562), the renowned mystic, who encouraged her as well.

In the months that followed, Teresa’s mystical experiences became more intense and frequent. The most famous of her visions is called the “Transverberation,” in which an angel pierced her heart with a flaming dart, an image immortalized by Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) in his statue Saint Teresa in Ecstasy and described by Teresa herself in Life: [Image at right]

I saw in his hands a large golden dart and at the end of the iron tip there appeared to be a little fire. It seemed to me that this angel plunged the dart several times into my heart and that it reached deep within me. When he drew it out, I thought he was carrying off with him the deepest part of me; and he left me all on fire with great love of God. The pain was so great that it made me moan, and the sweetness this greatest pain caused me was so superabundant that there is no desire capable of taking it away (Teresa 1987:252).

Teresa’s fame as a mystic now began to spread, but while many admired her spiritual sensitivity, others believed her to be a fraud.

The Catholic Church maintained a skeptical attitude toward mystics, who claimed to have personal experiences of God without the mediation of an ecclesiastical authority. The Church found the teachings of certain mystics too close to Protestantism or alumbradismo (Illuminism), which taught that the individual could be directly illuminated by God without external intervention. Especially problematic was the practice of Illuminist sects of holding meetings in private homes without the guidance of a priest and sometimes under the leadership of a woman. Many clerics viewed women as daughters of Eve (sinful and deceitful) which made them distrustful of female mystics. Hysteria was associated with women, and ecstasies in women were often viewed as signs of mental instability. Any nun claiming to have mystical experiences was investigated, and if she was deemed to be a fraud or, worse yet, possessed by the devil, her whole convent came under scrutiny.

Theologian Gillian Ahlgren argues that the Catholic Church’s position undermined women’s religious authority, which depended on revelation from God; as confidence in revelation diminished, “so inevitably did the authority of women’s voices” (Ahlgren 1996:21). As a female mystic, Teresa was in a vulnerable position made even more dangerous, as literary scholar Carole Slade points out, by her converso background, of which some people were surely aware despite her father’s and uncles’ pleitos de hidalguía (1995:20). Because Teresa herself distrusted her mystical experiences, she consulted her acquaintance García de Toledo (1514–1577), the subprior at the Royal Monastery of Saint Thomas. Through him, she met the respected Dominican theologian Pedro Ibáñez (c. 1589–1633), who declared her experiences legitimate. Still, García was concerned that Teresa would be investigated by the Inquisition. He ordered her to write a spiritual memoir to demonstrate the orthodoxy of her prayer practices.

Teresa felt uncomfortable at the Incarnation convent both because her reputation as a mystic was causing resentment among some of the Sisters and because no time was set aside for mental prayer. Along with her relative María de Ocampo and a close-knit group of friends, she decided to leave Incarnation, where she had lived nearly twenty-five years, and found a new convent that would adhere to the primitive rule. Here, nuns would live in poverty and silence, remain cloistered, forgo the use of titles such as Doña, and devote themselves to prayer. Dowries would not be required. Given her background as a converso, Teresa would not do background checks to determine lineage, a significant act of resistance against prevailing social norms (Slade 2001:91). The nuns would call themselves Discalced (Barefoot) Carmelites to highlight their commitment to austerity, although they did wear sandals. (Note that what distinguished the Discalced from the Calced [Shod] Carmelites was not footwear, but adherence to the original rule of the order.)

Opposition to Teresa’s project was fierce and immediate. To begin with, the reform was producing conflict in the Carmelite order. The Incarnation nuns were angry that Teresa had found their convent lacking. The Carmelite authorities were furious that Doña Guiomar had applied directly to Rome on Teresa’s behalf for authorization to found a new convent in the primitive rule under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Ávila, rather than under the Carmelite provincial, Ángel de Salazar (c. 1518–c. 1596). Furthermore, the city council was enraged that she had founded the community in poverty rather than under the sponsorship of a rich patron, as was the custom, arguing that the new convent would be expensive for the town to maintain, even though it was originally inhabited by only four Sisters.

Salazar was anxious to remove Teresa from Ávila. When the husband of Duchess Luisa de la Cerda died, Salazar sent Teresa to Toledo to comfort the grieving widow. However, rather than hinder Teresa’s plans, Salazar advanced them. In Toledo, Teresa made important friends who would help her with future foundations, that is, new communities of Discalced Carmelites. She also had time to compose her spiritual memoir—The Book of Her Life—and met María de San José (1548–1603), who would become one of her closest collaborators.

On August 24, 1562, the new convent, Saint Joseph of Ávila, opened its doors. Teresa returned to Incarnation, where she remained until she was given permission to occupy the Saint Joseph of Ávila convent the following year. In 1566, she wrote The Way of Perfection, a guide to prayer for the Sisters of the Saint Joseph convent. In the spring of 1567, the prior general, Giovanni Battista Rossi, known as Rubeo in Spain (1507–1578), made an official  visit to the new convent and consented to the creation of Discalced foundations for women as well as two for men in Castile. He did not want Teresa to found in the south because the Andalusian friars, who were known as a rough lot, were opposed to the reform. Teresa established a second Discalced Carmelite convent for women later in 1567, in Medina del Campo, where she met her future collaborator, John of the Cross (1542–1591). [Image at right] Although she had never wanted sponsors, the following year, she made a third foundation in Malagón, on the estate of her friend Doña Luisa. She also wrote the Constitutions of the order. More foundations followed: Valladolid (1568); Toledo (1569); Salamanca (1570); Alba del Tormes (1571). In the meantime, she instructed John of the Cross about the Discalced way of life. With Antonio de Heredia, he founded the first Discalced Carmelite convent for friars in Duruelos in 1568.

visit to the new convent and consented to the creation of Discalced foundations for women as well as two for men in Castile. He did not want Teresa to found in the south because the Andalusian friars, who were known as a rough lot, were opposed to the reform. Teresa established a second Discalced Carmelite convent for women later in 1567, in Medina del Campo, where she met her future collaborator, John of the Cross (1542–1591). [Image at right] Although she had never wanted sponsors, the following year, she made a third foundation in Malagón, on the estate of her friend Doña Luisa. She also wrote the Constitutions of the order. More foundations followed: Valladolid (1568); Toledo (1569); Salamanca (1570); Alba del Tormes (1571). In the meantime, she instructed John of the Cross about the Discalced way of life. With Antonio de Heredia, he founded the first Discalced Carmelite convent for friars in Duruelos in 1568.

Some clerics thought that Teresa was displaying too much independence and administrative ability for a woman. To get her out of the way, Salazar made her prioress of Incarnation, a Calced convent (one that followed the mitigated rule), where many of the nuns still harbored resentment against her. During the next three years, however, she managed to win them over and introduce reforms. She also named the Discalced friars John of the Cross and Germán de San Matías to be confessors at the Incarnation and began writing The Book of Foundations.

One of Doña Luisa’s friends was Ana de Mendoza, princess of Éboli, known to be a deceitful, treacherous woman. Because Doña Luisa had a convent on her property, Doña Ana insisted on endowing one on hers, in Pastrana. When her husband died, she moved into the new convent. However, she refused to obey the rules of the order, and after several clashes with the prioress, Isabel de Santo Domingo, she left. Then she suppressed the nuns’ revenue to starve them into submission. Teresa ordered the nuns to abandon the convent, which they did, sneaking out in the dead of night on April 6–7, 1574. Doña Ana took revenge by denouncing Teresa’s Life to the Valladolid Inquisition, which did not make a decision on the book until years later.

Although the Inquisition is often associated with the persecution of heterodoxy in Spain, it did not originate there. The German king and Roman emperor Frederick II (1194–1250) took a step toward the establishment of the Inquisition when he declared death by fire for impenitent members of certain religious sects in northern Italy. Pope Gregory IX (p. 1227–1241) later issued the decrees to institute the medieval Inquisition, an institution that spread throughout Germany, France, and Aragón (then an independent kingdom). By the time King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain adopted the Inquisition, its methods had already been established. Known as the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella received authority from the pope to appoint inquisitors in all parts of Castile, and tribunals were set up in eight Castilian cities. Two years later, tribunals were established in parts of Andalusia (Kamen 1998).

After founding a convent in Segovia in 1574, Teresa founded convents in Beas and Seville the following year. While in Beas, in 1575, she met Jerónimo Gracián (1545–1614), the Carmelite visitator, the friar charged with visiting convents to ensure they are observing the rules of the order. Thirty years Teresa’s junior, Gracián was well connected and filled with reformist zeal. Teresa was so impressed with him that she made a vow of obedience to him, while he promised to consult her on all issues involving the reform.

Teresa believed Beas to be in Castile, but it was actually under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Andalusia, where Rubeo had forbidden her to take the reform. The error had serious consequences. Gracián had already founded Discalced friaries in Andalusia, disregarding Rubeo’s order. Now, he convinced Teresa to found a convent in Seville. The new convent was inaugurated on May 26, 1575, with María de San José as prioress, and problems occurred from the beginning. A resentful nun accused Teresa, María, and others of unorthodox spiritual practices, leading to an investigation by the Seville Inquisition. Furthermore, the Carmelite authorities were furious that Teresa had disobeyed Rubeo’s directive. At the chapter meeting in 1575, in Piacenza, Italy, they decided that Teresa must retire to one convent and make no further foundations. Now the conflict between the Calced and Discalced Carmelites began in earnest.

Teresa retired to Toledo but was furious. She wrote in Foundations that the Toledo convent “would be a kind of prison” (Teresa 2011:338). Yet she maintained her leadership of the reform through intensive letter-writing activity. Starting in 1575, she wrote letters constantly, corresponding with Carmelite and other ecclesiastical authorities, collaborators, family members, and friends. When the Calced faction launched a campaign of calumnies against Gracián, she even wrote to King Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–1598) protesting the slanders of “the friars of the cloth,” as she called them (Mujica 2009a:18–43). At the behest of Gracián, she also began writing The Interior Castle, considered her masterwork, in which she describes the soul’s path toward union with God.

In response to the Piacenza directives, the new visitator, Jerónimo Tostado (1524–1582), attempted to suppress all the Discalced Carmelite convents and bring them under the control of the Calced, but King Philip II intervened and prevented him from achieving his goal. In 1577, a new papal nuncio, Filippo Sega (d. 1596), took office. An anti-reformist zealot, he joined Tostado in his efforts to eliminate the Discalced houses.

In July 1577, Teresa left Toledo, thanks again to the king’s intervention. She returned to Ávila, but now the same Incarnation nuns who had created obstacles for her earlier wanted her to serve as prioress for their convent. Teresa managed to have a new prioress installed, but then, Calced friars kidnapped and imprisoned John of the Cross and his associate Germán de San Matías. Once more, Teresa wrote to the king begging, unsuccessfully, for his intervention (Slade 2003). John endured a brutal captivity until he managed to escape nearly a year later (Rodríguez 2012:295–43).

On December 24, 1577, Teresa fell down the stairs and broke her arm at the Saint Joseph convent. Yet, with the help of an amanuensis, she continued to write letters to undermine Sega’s maneuvers. Finally, appalled by the behavior of the Calced friars, the pope intervened to force Sega to abandon his campaign. In 1580, the papal brief Pia consideratione allowed the Discalced to form a separate province, the same year that the Toledo Inquisition finally approved publication of a “corrected” version of Teresa’s Life. The following year, King Philip II officially divided the Calced and Discalced Carmelites, and the Discalced Constitutions were approved.

Exhausted and infirm, Teresa continued to carry on the work of the reform. During the last three years of her life, she founded convents at Villanueva de la Jara (1580), Palencia (1580), Soria (1581), and Burgos (1582). She assigned the task of founding a community in Granada to Anne of Jesus and John of the Cross (1582). In the spring of 1582, she initiated the journey to Burgos in a treacherous storm to found her last convent, inaugurated on April 19, 1582. She then left for Alba de Tormes, where she had been called by the Duchess of Alba. She died there on October 4. Due to the calendar reforms of Gregory XIII, which required the excision of the dates October 5–14, her death and feast day are celebrated on October 15. In total, Teresa was responsible for founding seventeen female and many male convents.

DEVOTEES

Teresa’s fame as a mystic and the foundress of a new order, the Discalced Carmelites, had spread widely long before she died. She was declared Blessed by Pope Paul V in 1614 and canonized by Pope Gregory XV on March 12, 1622, barely forty years after her death. Nevertheless, the process was far from automatic. Because female mystics continued to be viewed with suspicion, the canonization of women could be problematical.

Some seventeenth-century priests began to reconstruct Teresa’s image. Rather than celebrating her as a strong, innovative woman, they strove to transform her into “an obedient, submissive virgin who could serve as an emblem of female sanctity” (Mujica 2009a:181). They downplayed her work as spiritual guide and teacher, as they believed that these were roles that should be reserved for university-educated men. When the Bishop of Puebla Juan de Palafox y Mendoza (1600–1659), an influential cleric and politician, published the first printed edition of Teresa’s letters in 1656, he omitted those he considered problematical and included some apocryphal missives that highlighted the qualities he thought appropriate to a female saint (Mujica 2009a:182).

Some ecclesiastics were patently opposed to Teresa’s canonization, arguing that her books were proof of her pride, pride being Satan’s sin. In fact, the inquisitor Alonso de la Fuente crusaded to have Teresa’s books banned on the grounds that they were creations of the devil, even though Teresa had been investigated and cleared five times by the Inquisition (Weber 1990:160).

For many, however, Teresa’s canonization was cause for great celebration. Plays and poems were written in her honor. Etchings and paintings were made as well. In 1617, the Discalced Carmelites petitioned the Spanish cortes, or parliament, to make Teresa copatron saint of Spain, along with the existing patron saint, James (Santiago) of Compostela. This initiative was unsuccessful, as were several later ones. One of the fiercest opponents to Teresa’s elevation to the position of copatron saint was the Spanish writer Francisco de Quevedo (1580–1645). For Quevedo, Saint James was a hero in the battle against the infidel, one of the twelve apostles, and the protector of Spain, whose remains were buried at Compostela. According to historian Katie MacLean, “By preserving the pre-eminence of Santiago as the only patron of Spain, Quevedo hoped to preserve Spain’s unique tie to Christ and to the primitive Church” (MacLean 2006:905).

Interest in expanding the Discalced Carmelite reform beyond Spain began while Teresa was still alive. In 1578, Teutónio de Bragança (1530–1602), Archbishop of Évora, requested that she found a female convent in Portugal, but she was too occupied with other Discalced Carmelite business to act on his suggestion. However, in 1581, the year before Teresa’s death, Ambrosio Mariano, one of her close associates, founded a male convent in Lisbon, and in 1584, María de San José founded a female convent in the same city (Mujica 2020:25–134).

In 1604, Ana de Jesús (1545–1621), a close friend of Teresa’s, crossed the Pyrenees at the urging of the religious reformer Pierre de Bérulle (1575–1629), future confessor of King Henri IV (1553-1610, king of France 1589-1610). Bérulle was a member of a reformist spiritual circle known as Paris dévot, headed by his cousin Barbe Acarie (1565–1618). A powerful aristocrat, Acarie attributed her spiritual awakening to the French translation of Teresa’s hagiography, by Francisco de Ribeira. Acarie believed that God wanted her to bring the Discalced Carmelite reform to France, and she called upon her influential contacts to advance the project. Bérulle traveled to Spain to recruit Spanish nuns (among them Ana de Jesús and Teresa’s former nurse and amanuensis, Ana de San Bartolomé (1549–1626)) to found a Discalced Carmelite convent in Paris (Diefendorf 2006:78ff). Ana de Jesús became the first prioress (superior) of the Paris foundation, but she was unhappy in France, and, at the invitation of Isabel Clara Eugenia (1566–1633), who ruled as co-Sovereign of the Low Countries with her husband Albert of Austria (1559–1621), went north to found convents in Brussels, Louvain, and Mons (Mujica 2020:137–204).

Ana de San Bartolomé stayed in France to found several female convents. However, she and Bérulle soon had a serious falling out. According to Ana, Bérulle was manipulating the nuns and trying to take control of the order even though he was not a Discalced Carmelite. Eventually, Ana de San Bartolomé extricated herself from Bérulle’s dominance and followed Ana de Jesús to the Netherlands, where, in 1616, she founded a female Discalced Carmelite convent that still stands, in Antwerp (Mujica 2020:207–302).

The Discalced Carmelite reform spread rapidly throughout Europe and the New World during the seventeenth century. Today, Teresa of Ávila has millions of devotees. In addition to the nuns and friars, “third order” or “secular” Discalced Carmelites keep the order alive. These are lay persons from every walk of life who maintain a relationship with the Discalced Carmelites and practice the teachings of Saint Teresa.

Teresa has influenced many well-known people. For example, the German Jewish philosopher Edith Stein (1891–1942) converted to Catholicism after reading the works of Teresa de Ávila. Later, she became a Discalced Carmelite nun and was murdered by the Nazis because of her Jewish origins.

Teresa’s influence is not limited to those with ties to the order. In fact, Christians, non-Christians, and even nonbelievers have found inspiration in Teresa’s teachings. The current disillusionment with conventional religions in many sectors of society has sparked an explosion of popular interest in alternative approaches to faith. Teresa’s emphasis on interiority and meditation speaks to many people who consider themselves spiritual, yet not religious. The self-help writer Caroline Myss has attracted a large following with her Entering the Castle books and CDs, which are based on Teresa’s Interior Castle. Books on Teresa appear every year in Germany, Italy, and, of course, Spain and Latin America. France, considered a bastion of secularism, has produced several new books on Teresa, including Thérèse Mon Amour [Teresa, My Love], by Julia Kristeva (b. 1941), the prolific Bulgarian-born philosopher, feminist critic, and psychoanalyst. Interest in Teresa has been so intense in recent years that Publisher’s Weekly called her “a mystic for our times” (Mujica 2010).

TEACHINGS AND PRACTICES

By the late Middle Ages, many Christians in Europe recognized the need for spiritual reform, as the Catholic Church had become highly bureaucratic, and prayer was often reduced to empty rituals. New orders that stressed austerity and simplicity, in accordance with their primitive rules, began to form. In the Low Countries, laypeople spearheaded the devotio moderna, a movement aimed at restoring a more authentic form of Christianity. Adherents practiced mental prayer, a direct and unstructured conversation with God in which one speaks directly to God and listens to the voice within. The movement was popular both among certain Spanish nobles and conversos, who preferred to pray without the encumbrance of Catholic ritual.

Although Teresa had learned the principles of the devotio moderna from Osuna’s book, she did not put its teachings into practice immediately. However, she eventually came to understand that mental prayer provided a means to enter the depths of the soul and find God within. In The Interior Castle, she offers a concise description of her spiritual teachings and prayer practices through the metaphor of the soul as “a castle made entirely out of a diamond or very clear crystal, in which there are many rooms, just as in heaven, there are many dwelling places” (Teresa 1980:283). Through the process of recollection, the soul moves into itself, through the rooms, which are arranged in seven concentric circles, gradually detaching itself from worldly concerns as it approaches the center, where God dwells. The door that enables the soul to enter the castle is prayer, but prayer is not an intellectual process; it is an effect of the soul’s longing for God and of God’s love for us. Prayer does not guarantee a mystical experience. The Interior Castle is not a manual on how to achieve union with God, which depends solely on the divine will. It is, rather, a description of a process that no two people experience in the same way.

The circles of the castle are arranged symmetrically, with the three outer circles corresponding to the meditative, or active, stages of prayer. For example, the individual can initiate recollection by engaging with an inspirational image or reading. The outer rooms of the castle remain relatively dark, as they receive little light from within. However, Teresa writes:

It should be kept in mind here that the fount, the shining sun that is in the center of the soul, does not lose its beauty and splendor; it is always present in the soul, and nothing can take away its loveliness. But if a black cloth is placed over a crystal that is in the sun, obviously the sun’s brilliance will have no effect on the crystal even though the sun is shining on it. (Teresa 1980:289)

That is, while the soul is still consumed with worldly matters, it remains “in the dark.” It cannot reach its inner light. Yet, that light is always present, and the soul can strive to reach it through prayer.

The fourth circle is transitional and can be painful because here the soul loses agency; it can no longer advance on its own but depends entirely on God’s will. The three inner circles correspond to the passive, or contemplative, stages of prayer. Now, the faculties and understanding cease to function, and the soul surrenders entirely to God.

When beginning to pray, the soul meets with many obstacles. The poisonous pests on the periphery of the castle represent the temptations and vanities that distract us from prayer. The servants of the castle, the senses, reside in the first dwelling places and serve as mediators between the soul and the “world,” that is, the everyday concerns that keep us from advancing in prayer. In the second dwelling places, the intellect is not passive but plays an important role in the process of detachment, for it now grasps the dangers of worldly things and consciously disengages from them. It recognizes its own sinfulness, which sparks humility, a virtue essential for spiritual progress. In the third dwelling places, the soul becomes increasingly aware of its own free will, which it places at God’s service. This means serving others, for, as Teresa writes, love of God “must not be fabricated in our imaginations but proved by deeds” (Teresa 1980:308). For Gillian Ahlgren, this is “a space of greater mindfulness, intentionality and personal integration” (Ahlgren 2016:28).

The journey into the castle is a process of letting go. By the fourth dwelling places, the soul is reaching a state of detachment, and hence, inner tranquility. The intellect is much less active: “the important thing is not to think much but to love much” (Teresa 1980:319). Once the soul opens itself completely to God’s love, the individual becomes more sensitive and compassionate toward others. At the same time, the soul suffers because it is anxious to move more deeply into itself but cannot do so of its own will; its progress depends on God.

The fifth dwelling places mark the beginning of the contemplative state, the “prayer of union,” during which the soul comes to understand God’s love more profoundly. The faculties are benumbed. The soul “has died to the world as to live completely in God. Thus, the death is a delightful one. . .” (Teresa 1980:337). The soul is like a moth that is drawn to a flame and is consumed by it. Yet it does not lose all agency. As Ahlgren explains, it opens itself “relationally to allow for divine activity to operate in it” (Alhgren 2005:69). The soul is transformed by submitting completely to God, which intensifies its awareness of its connection to others and its wish to serve.

In the sixth circle, the soul comes to know God mystically, sometimes experiencing favors such as raptures (feelings of ecstasy or being transported to another dimension). The soul may become frightened, explains Teresa, for God’s presence can be overwhelming: “The soul truly suffers a form of disintegration in the sixth dwelling places, because it is undergoing a final purification that threatens its identity as an individual” (Ahlgren 2005:90). However, this dissolution of the self is what permits the transformation of the soul and enables it to endure everyday challenges. The soul will emerge renewed and ready to enjoy the delights of the spiritual marriage in the seventh circle.

Through the metaphor of marriage, Teresa describes the total surrendering of the soul (the Bride) and God (the Bridegroom) to each other. [Image at right] Spiritual marriage is different from spiritual union, explains Teresa, for in the latter, the lovers can separate: “Let us say that the union is like the joining of two wax candles to such an extent that the flame coming from them is but one. . . . But afterward, one candle can be easily separated from the other. . .” (Teresa 1980:434). In contrast, marriage is like rain that falls into a river: “all is water, for the rain that fell from heaven cannot be divided or separated from the water of the river” (Teresa 1980:434). They are one. Teresa also employs the metaphor of the butterfly (the soul) that approaches a candle (God) and is consumed by flame, becoming oblivious to its physical self and the world. It emerges from this experience transformed and with the desire to submit entirely to do God’s will, not by withdrawing from the world but by “helping the Crucified,” that is, those who are suffering (Teresa 1980:439).

ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Teresa’s profound experience of God’s presence in her soul galvanized her to found a new religious order, the Discalced Carmelites. Having experienced life at Incarnation, an overcrowded, mitigated Carmelite convent, Teresa wanted to provide other women with a truly spiritual environment where they could immerse themselves in prayer.

In early modern Spain, many women entered convents with no sense of vocation. Some were the younger daughters of parents without the means or desire to pay their marriage dowries and so placed them there as toddlers. Some were widows, orphans, or girls with tainted honor. Convents reflected the prevailing social hierarchy. Nuns from aristocratic families maintained their titles and enjoyed special privileges, such as keeping their servants and slaves. Often relatives joined the same convent, which contributed to cliquishness and petty rivalries. At the time Teresa made her profession, Incarnation was severely overpopulated. Although fasting, abstinence, and periods of silence were required, strict claustration (enclosure) was not. Because the number of inhabitants was larger than the convent could comfortably accommodate, nuns were permitted to take their meals elsewhere and accept gifts of food from visitors.

The new order that Teresa founded followed the unmitigated Carmelite rule. The nuns lived in poverty and devoted themselves entirely to God. They renounced their titles and social identity, disassociating themselves from the male power structure by taking new names. Thus, Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada became Teresa de Jesús. To avoid girls taking vows before they understood their commitment, Teresa set the minimum age for novices at seventeen. To avoid overcrowding, she limited the number of nuns in a convent to around thirteen, although the number sometimes fluctuated.

For Teresa, withdrawal into the convent mirrored the inward movement of the soul, a liberating experience that freed the individual from the trials of everyday life (Carrión 1994:133). Yet, a spiritual life was an active life. It required making conscious decisions in conformity with God’s will and acting on them. Teresa saw spreading the reform as a spiritual mission, one that involved risks. In the face of fierce opposition, making foundations became a form of engagement, even militancy (Bilinkoff 1994:174). Paradoxically, the castle, a refuge from worldly affairs, prepares the individual to better engage in worldly affairs. Spiritual grounding enables today’s men and women to better interact with others and to accept a role in contemporary life.

As founder of a new order, Teresa maintained administrative responsibility for the operation of her convents. She argued that she, not a priest, was best equipped to govern the nunneries because she had a better understanding of female psychology than any man. Since visitators were always male, she wrote The Way of Visiting Convents to guide them. Teresa’s letters show that she was involved with every detail of convent management: the selection of novices, finance, dowries, legal issues, property management, discipline, health, and diet (Mujica 2009a:141–177). She was especially concerned with mental health and wrote extensively on melancholia in Foundations. She determined how nuns could spend their leisure moments and how they sang psalms. She also had to deal with political and diplomatic questions, such as the order’s sometimes rocky relationship with the Jesuits (Mujica 2009a:172–177). As she couldn’t be everywhere at once, she had to handle many of these matters by letter.

Teresa gave prioresses considerable administrative freedom to manage their convents. They could accept novices, negotiate dowries, and purchase property, although Teresa maintained oversight authority. Prioresses were also charged with the spiritual well-being of their nuns. Early modern Hispanist Alison Weber points out that one of Teresa’s innovations was “a system of governance based on an expanded spiritual magisterium for prioresses working in close collaboration with prelates who shared their vision” (Weber 2000:126). Prioresses were to work together with confessors to ensure the spiritual progress of their nuns. Teresa herself had some bad experiences with incompetent confessors and wanted to ensure that those working with Discalced Carmelite nuns were sensitive to their needs.

ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

Teresa met with opposition from the beginning of her career due largely to the Catholic Church’s distrust of mystics, especially female mystics. [Image at right] The prevailing view that women were defective beings, prideful and susceptible to the wiles of the devil, meant that women had to avoid appearing clever, independent-minded, or assertive. Alison Weber argues that Teresa used different rhetorical strategies in her writing to affirm her authority yet avoid the appearance of pride. Like many early modern women, she cultivated a “rhetoric of modesty,” using self-deprecating language or expressions such as “it seems to me” to avoid making outright assertions (Weber 1990:42–70).

Teresa’s teachings made her susceptible to charges of alumbradismo, and, in fact, her name first appears in Inquisition records in 1574 in connection with a case of Illuminism. Although she was never brought to trial, without the intervention of influential friends, she might have suffered severe punishment (Slade 1995:17–18). The Interior Castle links Teresa to the apophatic tradition, which teaches that by moving inward, the soul finds absolute darkness from which the light of God emanates. Strict apophaticism admits no rational understanding or anthropomorphic descriptions of God, which made it problematic for the Church, since Christianity centers on belief in the manifest presence of God on Earth through Christ. Apophaticism came to be seen as a manifestation of spiritual autonomy. It was associated with Illuminism and, later, Protestantism.

Teresa sought to disassociate herself from strict apophaticism. In Chapter 22 of Life, she defends the centrality of the sacred humanity of Christ, and in The Interior Castle, images of Christ in his humanity and Christ as Bridegroom abound, especially in the seventh dwelling places. The danger in the sixth dwelling places, she explains, is that the soul will become so lost in contemplation that it will disengage from the Passion, the physical presence of the suffering Christ (Teresa 1980:399). Teresa’s insistence on the humanity of Christ positioned her securely within the tenets of Catholic Christianity. The words she reputedly spoke on her deathbed, “I die a daughter of the Church,” were a final affirmation of her orthodoxy and Catholic identity (Slade 1995:71).

SIGNIFICANCE TO THE STUDY OF WOMEN IN RELIGIONS

Unlike letrados (lettered men who studied scripture and practiced an intellectualized spirituality based on theology), women did not receive a university education. They practiced affective spirituality, which depended more on interior experience than on formal theologizing. By founding convents that fostered interiority, Teresa validated women’s devotional practices and defended their right to pursue higher forms of spiritual activity. Her manuals, The Interior Castle and The Way of Perfection, written to guide her nuns in prayer, came to be cherished by a wide audience outside the convent.

Discalced Carmelite convents offered women not only a place for spiritual growth, but also opportunities for educational and vocational development (Mujica 2009b:74–82). [Image at right]Teresa read widely in the vernacular, and she specified in article forty of the Constitutions that all Discalced Carmelite nuns be taught to read (Teresa 2011:321). Teresa believed that reading, which enabled nuns to seek counsel in the words of sages, was an indispensable protection against unscrupulous or ignorant confessors. White-veiled nuns—those who performed menial tasks such as cooking, cleaning, gardening, and nursing—were not required to learn to write. Black-veiled nuns, who were responsible for praying the Divine Office, had to learn both to read and write.

Convents of literate nuns of different orders often developed into true intellectual communities, with Sisters writing chronicles, memoirs, poetry, plays or letters (Arenal and Schlau 1989). In some convents, nuns composed music. In some, they painted religious images. All Discalced Carmelite convents had a novice mistress who taught reading, writing, and religion, as well as an infirmarian who cared for the ill and a cellaress in charge of ordering provisions.

Discalced Carmelite nuns withdrew from the world to form strong prayer communities where women found spiritual sustenance, a sense of unity and belonging, and meaningful work. After Teresa’s death, the reform spread throughout the world. Today there are Discalced Carmelite convents on every continent. Teresa of Ávila’s successful leadership is manifested in the seventeen female convents, and additional male monasteries, she founded, as well as the expansion of Discalced Carmelites throughout Europe. Perhaps the sixteenth-century saint’s most famous protégé is a nineteenth-century saint, Thérèse of Lisieux (1873–1897), a Discalced Carmelite known as the Little Flower.

IMAGES

Image #1: Portrait of Teresa of Ávila, by French painter François Gerard, 1827. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #2: The Vision of Saint Teresa. Portrait by Francesco Cozza. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #3: Statue of Teresa by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, titled “Teresa in Ecstasy.” Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome. Wikiemedia Commons.

Image #4: John of the Cross, 1656. Portrait attributed to Zurbarán. From www.muzeum.archidiecezja.katowice.pl. Wikimedia Commons..

Image #5: Saint Teresa of Ávila. Wikimedia Commons.

Image #6: Statues representing John of the Cross and Teresa of Ávila in Beas de Segura. Cosasdebeas. Wikimedia Commons.

Image # 7: Carmelite saints: Blessed Anne of Jesus, Saint Teresa of Ávila, and Blessed Anne of St. Bartholomew. The Church of Stella Maris, Haifa, Israel. Adobe Stock Photos.

REFERENCES

Ahlgren, Gillian. 2016. Enkindling Love: The Legacy of Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Ahlgren, Gillian. 2005. Entering Teresa de Ávila’s Interior Castle: A Reader’s Companion. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Arenal, Electa, and Stacy Schlau. 1989. “‘Leyendo yo y escribiendo ella’: The Convent as Intellectual Community.” Journal of Hispanic Philology 13:214–29.

Bilinkoff, Jodi. 1989. The Ávila of Saint Teresa: Religious Reform in a Sixteenth-Century City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Carrión, María. 1994. Arquitectura y cuerpo en la figura autorial de Teresa de Jesús. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Diefendorf, Barbara B. 2004. From Penitence to Charity: Pious Women and the Catholic Reformation in Paris. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Egido, Teófanes. 1986. El linaje judeoconverso de santa Teresa. Madrid: Espiritualidad.

Kamen, Henry. 1998. The Spanish Inquisition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

MacLean, Katie. 2006. “The Mystic and the Moor-Slayer: Saint Teresa, Santiago and the Struggle for Spanish Identity.” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 83:887–910.

Medwick, Cathleen. 1999. Teresa de Ávila: The Progress of a Soul. New York: Knopf.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2020. Women Religious and the Epistolary Exchange in the Carmelite Reform: The Disciples of Teresa de Ávila. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2010. “Teresa de Ávila: A Woman of Her Time, A Saint for Ours.” Commonweal, February 22. Accessed from https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/teresa-%C3%A1vila on 15 December 2023.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2009a. Teresa de Ávila, Lettered Woman. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2009b. “Was Teresa of Ávila a Feminist?” Pp. 74-82 in Approaches to Teaching Teresa de Ávila and the Spanish Mystics, edited by Alison Weber. New York: Modern Language Association.

Rodríguez, José Vicente. 2016. San Juan de la Cruz: La biografía. Madrid: San Pablo.

Slade, Carole. 2003. “The Relationship between Teresa of Ávila and Philip II: A Reading of the Extant Textual Evidence.” Archive for Reformation History 94, no. 1: 223–42.

Slade, Carole. 1995. St. Teresa of Ávila: Author of a Heroic Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Teresa de Ávila (de Jesús). 2007. The Collected Letters of St. Teresa of Ávila. Translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. Volume 2. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Teresa de Ávila (de Jesús). 2001. The Collected Letters of St. Teresa of Ávila. Translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. Volume 1. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Teresa de Ávila (de Jesús). 2011. The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Ávila. Translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodríguez, O.C.D. Volume 3. Washington D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Teresa de Ávila (de Jesús). 1987. The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Ávila. Translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodríguez, O.C.D. Volume 1, Revised. Washington D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Teresa de Ávila (de Jesús). 1980. The Collected Works of St. Teresa of Ávila. Translated by Kieran Kavanaugh, O.C.D. and Otilio Rodríguez, O.C.D. Volume 2. Washington D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Walsh, William. 1943. Saint Teresa of Ávila. Rockford, IL: Tan.

Weber, Alison. 2000. “Spiritual Administration: Gender and Discernment in the Carmelite Reform.” Sixteenth Century Journal 31:127–50.

Weber, Alison. 1990. Teresa de Ávila and the Rhetoric of Femininity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

SUPPLEMENTARY RESOURCES

Carrera, Elena. 2005. Teresa de Ávila’s Autobiography: Authority, Power and the Self in Mid-Sixteenth Century Spain. Oxford: Legenda / Modern Humanities Research Association.

Efrén de la Madre de Dios, and Otger Steggink. 1986. Tiempo y vida de Santa Teresa de Jesús. Madrid: Espiritualidad.

Lehfeldt, Elizabeth. 2005. Religious Women in Golden Age Spain: The Permeable Cloister. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2023. “Finding Refuge in Your Own Castle: Teresa de Ávila’s Las Moradas.” Pp. 149-61 in Refugees, Refuge, and Human Displacement, edited by Ignacio López-Calvo and Marjorie Agosín. New York: Anthem.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2007. Sister Teresa. New York: Overlook.

Mujica, Bárbara. 2001. “Beyond Image: The Apophatic-Kataphatic Dialectic in Teresa de Ávila.” Hispania 84:741–48.

Osuna, Francisco. 1981. The Third Spiritual Alphabet. Translated by Mary Giles. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Rossi, Rosa. 1984. Teresa de Ávila: Biografía de una escritora. Translated by Marieta Gargatagli. Barelona: Icaria.

Weber, Alison, ed. 2009. Approaches to Teaching Teresa de Ávila and the Spanish Mystics, edited by Alison Weber. New York: Modern Language Association.

Welch, John. 1982. Spiritual Pilgrims: Carl Jung and Teresa de Ávila. New York: Paulist Press.

Wilson, Christopher, ed. 2006. The Heirs of Saint Teresa. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Carmelite Studies.

Publication Date:

18 December 2023

bohemian hippie community. They set up a store front called Mystic Arts World and sold various products that catered to the growing psychedelic subculture. It seemed that the Brotherhood and its gospel of love and LSD was gaining traction, but to grow even further, they would need legitimation of a grander sort. Griggs began to recruit of one of the most infamous counter-cultural icons of the 1960s,

bohemian hippie community. They set up a store front called Mystic Arts World and sold various products that catered to the growing psychedelic subculture. It seemed that the Brotherhood and its gospel of love and LSD was gaining traction, but to grow even further, they would need legitimation of a grander sort. Griggs began to recruit of one of the most infamous counter-cultural icons of the 1960s,  west coast. Leary, who was facing mounting law enforcement pressure in New York, would eventually move to Laguna Beach in 1966. In Laguna, Leary and his family took root, hosting psychedelic sessions and lectures at the Mystic Arts World on Leary’s popular catchphrase: “turn on, tune in, and drop out” (Greenfield 2006). [Image at right] Leary settled into his role as the spiritual guru, bringing both academic clout and a “pop-star” like presence to the west coast, and it certainly gave the Brotherhood a sense of visibility that they didn’t have before (Schou 2010). Griggs and Leary’s relationship was mutually beneficial as they worked together to hatch a plan to find a property that would help them and others to “drop out” of society, but they did have disagreements as to where. Griggs, and much of the Brotherhood, had always envisioned buying an island utopia somewhere in the South Pacific; Leary, on the other hand, wanted to stay on the mainland. Many members of the Brotherhood believed Leary wanted to stay on the mainland to be closer to media and publicity in order to take psychedelics mainstream. Eventually, the Brotherhood used their money to buy a ranch north of Palm Springs, and named it the Idyllwild ranch. The purchasing of the ranch foreshadowed the divergent views within the Brotherhood, as it became increasingly muddled by Leary’s fame, money from the drug trade, and the ambitions to transform society (Schou 2010).

west coast. Leary, who was facing mounting law enforcement pressure in New York, would eventually move to Laguna Beach in 1966. In Laguna, Leary and his family took root, hosting psychedelic sessions and lectures at the Mystic Arts World on Leary’s popular catchphrase: “turn on, tune in, and drop out” (Greenfield 2006). [Image at right] Leary settled into his role as the spiritual guru, bringing both academic clout and a “pop-star” like presence to the west coast, and it certainly gave the Brotherhood a sense of visibility that they didn’t have before (Schou 2010). Griggs and Leary’s relationship was mutually beneficial as they worked together to hatch a plan to find a property that would help them and others to “drop out” of society, but they did have disagreements as to where. Griggs, and much of the Brotherhood, had always envisioned buying an island utopia somewhere in the South Pacific; Leary, on the other hand, wanted to stay on the mainland. Many members of the Brotherhood believed Leary wanted to stay on the mainland to be closer to media and publicity in order to take psychedelics mainstream. Eventually, the Brotherhood used their money to buy a ranch north of Palm Springs, and named it the Idyllwild ranch. The purchasing of the ranch foreshadowed the divergent views within the Brotherhood, as it became increasingly muddled by Leary’s fame, money from the drug trade, and the ambitions to transform society (Schou 2010). opportunity to build the island utopia. Hawaii had transformed into a haven for hippies, surfers, and various vagabonds, all of whom had an insatiable appetite for marijuana. To capitalize on this large market, Ashbrook purchased a seventy-foot yacht, the Aafje, to smuggle hash from Asia and Mexico into Maui. [Image at right] From 1969-1972, Maui was indeed profitable, as many members of the Brotherhood raked in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in illicit drug profits (Maguire and Ritter 2014).

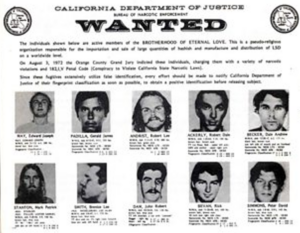

opportunity to build the island utopia. Hawaii had transformed into a haven for hippies, surfers, and various vagabonds, all of whom had an insatiable appetite for marijuana. To capitalize on this large market, Ashbrook purchased a seventy-foot yacht, the Aafje, to smuggle hash from Asia and Mexico into Maui. [Image at right] From 1969-1972, Maui was indeed profitable, as many members of the Brotherhood raked in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, in illicit drug profits (Maguire and Ritter 2014). continued through the following year. Twenty-six members of the Brotherhood, or those affiliated with its smuggling operation, were targeted by police. [Image at right] Possibly the biggest catch, Timothy Leary, was captured in Kabul, Afghanistan, and flown back to Los Angeles. He was charged with escaping prison, along with various other drug charges. The police raid, and the revelations of the depths of the drug trafficking operations, no doubt captured the media’s attention, with Rolling Stone magazine dubbing the group “the Hippie Mafia.” By October 3, 1973, the U.S. government all but celebrated its victory over the Brotherhood. That day, a subcommittee hearing, entitled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” highlighted the extensive drug smuggling operation of the group. DEA supervisor Job Sinclair told Congress:

continued through the following year. Twenty-six members of the Brotherhood, or those affiliated with its smuggling operation, were targeted by police. [Image at right] Possibly the biggest catch, Timothy Leary, was captured in Kabul, Afghanistan, and flown back to Los Angeles. He was charged with escaping prison, along with various other drug charges. The police raid, and the revelations of the depths of the drug trafficking operations, no doubt captured the media’s attention, with Rolling Stone magazine dubbing the group “the Hippie Mafia.” By October 3, 1973, the U.S. government all but celebrated its victory over the Brotherhood. That day, a subcommittee hearing, entitled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” highlighted the extensive drug smuggling operation of the group. DEA supervisor Job Sinclair told Congress:

5, Alonso de Cepeda married Catalina del Peso, who bore him two children and then died in 1507. Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada was the third child and eldest daughter of Alonso and his second wife, Beatriz de Ahumada. Before Teresa was born, [Image at right] Beatriz had had two sons and then, after Teresa’s birth, five more sons and another daughter, Juana. It was the custom in large families for some children to take their father’s surname and others to take their mother’s. Teresa, who was named after her maternal grandmother, took her mother’s. After Beatriz died shortly after Juana’s birth in 1528, Teresa took the Virgin to be her mother, she writes in The Book of Her Life.

5, Alonso de Cepeda married Catalina del Peso, who bore him two children and then died in 1507. Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda y Ahumada was the third child and eldest daughter of Alonso and his second wife, Beatriz de Ahumada. Before Teresa was born, [Image at right] Beatriz had had two sons and then, after Teresa’s birth, five more sons and another daughter, Juana. It was the custom in large families for some children to take their father’s surname and others to take their mother’s. Teresa, who was named after her maternal grandmother, took her mother’s. After Beatriz died shortly after Juana’s birth in 1528, Teresa took the Virgin to be her mother, she writes in The Book of Her Life.

guidance Teresa made considerable spiritual progress. She also met Pedro de Alcántara (1499–1562), the renowned mystic, who encouraged her as well.

guidance Teresa made considerable spiritual progress. She also met Pedro de Alcántara (1499–1562), the renowned mystic, who encouraged her as well. visit to the new convent and consented to the creation of Discalced foundations for women as well as two for men in Castile. He did not want Teresa to found in the south because the Andalusian friars, who were known as a rough lot, were opposed to the reform. Teresa established a second Discalced Carmelite convent for women later in 1567, in Medina del Campo, where she met her future collaborator, John of the Cross (1542–1591). [Image at right] Although she had never wanted sponsors, the following year, she made a third foundation in Malagón, on the estate of her friend Doña Luisa. She also wrote the Constitutions of the order. More foundations followed: Valladolid (1568); Toledo (1569); Salamanca (1570); Alba del Tormes (1571). In the meantime, she instructed John of the Cross about the Discalced way of life. With Antonio de Heredia, he founded the first Discalced Carmelite convent for friars in Duruelos in 1568.

visit to the new convent and consented to the creation of Discalced foundations for women as well as two for men in Castile. He did not want Teresa to found in the south because the Andalusian friars, who were known as a rough lot, were opposed to the reform. Teresa established a second Discalced Carmelite convent for women later in 1567, in Medina del Campo, where she met her future collaborator, John of the Cross (1542–1591). [Image at right] Although she had never wanted sponsors, the following year, she made a third foundation in Malagón, on the estate of her friend Doña Luisa. She also wrote the Constitutions of the order. More foundations followed: Valladolid (1568); Toledo (1569); Salamanca (1570); Alba del Tormes (1571). In the meantime, she instructed John of the Cross about the Discalced way of life. With Antonio de Heredia, he founded the first Discalced Carmelite convent for friars in Duruelos in 1568.

him a copy of a mock psychological test he had devised as well as a description of his mescaline experience. Leary responded with a postcard and invitation to visit the Millbrook estate (Kleps 2005:5). [Image at right]

him a copy of a mock psychological test he had devised as well as a description of his mescaline experience. Leary responded with a postcard and invitation to visit the Millbrook estate (Kleps 2005:5). [Image at right] ly irreverent and satirical tact when establishing its structure. “Clergy” were known as “Boo Hoos (male)” or “Bee Hees (female)” while a “Primate” was designated for each state by the “Chief Boo Hoo (Kleps).” State Primates could name local Boo Hoos, but final decisions were made by Kleps. A “Board of Toads” acted in an advisory manner and included Timothy Leary and William Mellon (Billy) Hitchcock, co-owner of the Millbrook estate along with his twin brother Thomas (Tommy) Hitchcock III. The church’s symbol was a drawing of a three-eyed toad, [Image at right] while its official motto was “Victory over Horseshit” and its official hymn was “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

ly irreverent and satirical tact when establishing its structure. “Clergy” were known as “Boo Hoos (male)” or “Bee Hees (female)” while a “Primate” was designated for each state by the “Chief Boo Hoo (Kleps).” State Primates could name local Boo Hoos, but final decisions were made by Kleps. A “Board of Toads” acted in an advisory manner and included Timothy Leary and William Mellon (Billy) Hitchcock, co-owner of the Millbrook estate along with his twin brother Thomas (Tommy) Hitchcock III. The church’s symbol was a drawing of a three-eyed toad, [Image at right] while its official motto was “Victory over Horseshit” and its official hymn was “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

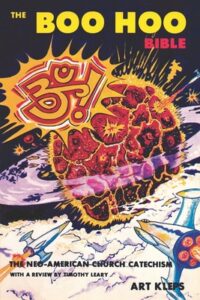

summer. All the while, Kleps worked regularly on his first book, The Neo-American Church Catechism and Handbook, aka, “The Boo-Hoo Bible,” which was first printed and distributed by the Sri Ram Ashram on a printing press they installed in the estate’s former carriage house. [Image at right]

summer. All the while, Kleps worked regularly on his first book, The Neo-American Church Catechism and Handbook, aka, “The Boo-Hoo Bible,” which was first printed and distributed by the Sri Ram Ashram on a printing press they installed in the estate’s former carriage house. [Image at right] Columbia ruled that, essentially, the NAC was not a “true” religion at all and that, therefore, its members were not protected by the free exercise clause. In the ruling opinion written by District Judge Gerhard A. Gesell, he suggested that a close examination of the NAC’s established beliefs and a reading of The Boo Hoo Bible [Image at right] showed a lack of “any solid evidence of a belief in a supreme being, a religious disciple, a ritual, or tenets to guide one’s daily existence” and that instead “one gains the inescapable impression that the membership is mocking established institutions” and shows no regard for “a supreme being, law or civic responsibility” (United States v. Kuch 1968).

Columbia ruled that, essentially, the NAC was not a “true” religion at all and that, therefore, its members were not protected by the free exercise clause. In the ruling opinion written by District Judge Gerhard A. Gesell, he suggested that a close examination of the NAC’s established beliefs and a reading of The Boo Hoo Bible [Image at right] showed a lack of “any solid evidence of a belief in a supreme being, a religious disciple, a ritual, or tenets to guide one’s daily existence” and that instead “one gains the inescapable impression that the membership is mocking established institutions” and shows no regard for “a supreme being, law or civic responsibility” (United States v. Kuch 1968). occultism already in his teens (Hilton 2005:202–04). The family moved to Gothenburg in the early nineties when Khashnood-Sharis was a young adult, and it was here that MLO was first envisioned. Khashnood-Sharis changed his name to Nemesis, but also called himself “Vlad,” “N.A-A.218” and “Father Nemidial.” He was most likely always the front-runner and group leader, even though the hierarchy of MLO was originally intended to be egalitarian (Hilton 2005:190). Jon Nödtveidt (1975–2006), [Image at right] the guitarist of the Black Metal band Dissection, joined the group early in its history. Originally from a small town a few hours from Gothenburg, Nödtveidt had always been interested in music and Black Metal became a passion. He joined the True Satanist Hord, a group of Black Metal enthusiasts who experimented with extreme forms of metal music and occultism. Nödtveidt was later introduced to MLO and Khashnood-Sharis by a mutual friend, one of MLO’s original members (Bogdan 2016:490–91; Hilton 2005:187). Khashnood-Sharis and Nödtveidt quickly became close, inseparable, and they made up the core of the group.

occultism already in his teens (Hilton 2005:202–04). The family moved to Gothenburg in the early nineties when Khashnood-Sharis was a young adult, and it was here that MLO was first envisioned. Khashnood-Sharis changed his name to Nemesis, but also called himself “Vlad,” “N.A-A.218” and “Father Nemidial.” He was most likely always the front-runner and group leader, even though the hierarchy of MLO was originally intended to be egalitarian (Hilton 2005:190). Jon Nödtveidt (1975–2006), [Image at right] the guitarist of the Black Metal band Dissection, joined the group early in its history. Originally from a small town a few hours from Gothenburg, Nödtveidt had always been interested in music and Black Metal became a passion. He joined the True Satanist Hord, a group of Black Metal enthusiasts who experimented with extreme forms of metal music and occultism. Nödtveidt was later introduced to MLO and Khashnood-Sharis by a mutual friend, one of MLO’s original members (Bogdan 2016:490–91; Hilton 2005:187). Khashnood-Sharis and Nödtveidt quickly became close, inseparable, and they made up the core of the group. soaking in a bathtub of what was said to be blood and described her admiration and love of Satan. Khashnood-Sharis and the woman became involved, and she was, most likely, part of MLO during this time. After having reported Khashnood-Sharis to the authorities the couple reunited and Khashnood-Sharis’ girlfriend supported him in court, pregnant with his child (Hilton 2005:220).

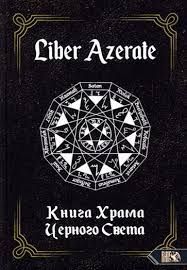

soaking in a bathtub of what was said to be blood and described her admiration and love of Satan. Khashnood-Sharis and the woman became involved, and she was, most likely, part of MLO during this time. After having reported Khashnood-Sharis to the authorities the couple reunited and Khashnood-Sharis’ girlfriend supported him in court, pregnant with his child (Hilton 2005:220). band Dissection released their third and last album Reinkaos [Image at right] on April 30, 2006. The lyrics were said to be based on Liber Azerate and MLO-beliefs. In 2006, after some public interviews concerning his music, he was reported as having said that he was planning a trip to Transylvania (said to be a designation for Hell), Nödtveidt was found in his apartment shot dead by a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Nödtveidt’s body is said to have laid in the middle of a pentagram drawn on the floor, with a book (possibly Liber Azerate) next to him (Introvigne 2016:509). Soon after Nödtveidt’s death, MLO changed its name to Temple of Black Light. Not much is known of the activities or structure of the group since then, as few studies have been conducted. However, Khashnood-Sharis has continued to published a series of books exploring the worldview and sacramental aspects of the particular form of Satanism of MLO, also termed “Chaos-Gnosticism.”

band Dissection released their third and last album Reinkaos [Image at right] on April 30, 2006. The lyrics were said to be based on Liber Azerate and MLO-beliefs. In 2006, after some public interviews concerning his music, he was reported as having said that he was planning a trip to Transylvania (said to be a designation for Hell), Nödtveidt was found in his apartment shot dead by a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Nödtveidt’s body is said to have laid in the middle of a pentagram drawn on the floor, with a book (possibly Liber Azerate) next to him (Introvigne 2016:509). Soon after Nödtveidt’s death, MLO changed its name to Temple of Black Light. Not much is known of the activities or structure of the group since then, as few studies have been conducted. However, Khashnood-Sharis has continued to published a series of books exploring the worldview and sacramental aspects of the particular form of Satanism of MLO, also termed “Chaos-Gnosticism.”