Demographics2

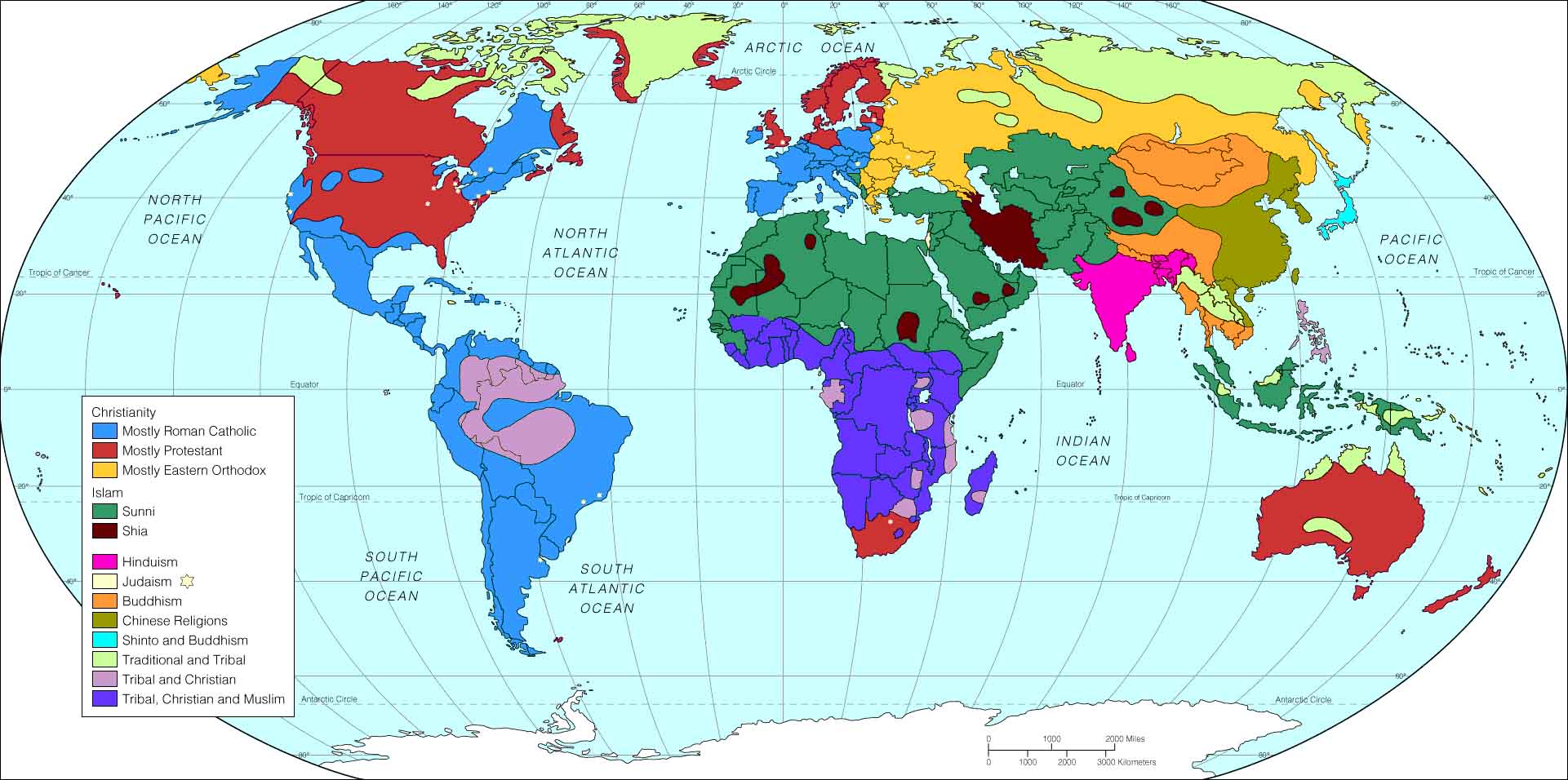

GLOBAL STATUS OF MAJOR WORLD RELIGIONS

(RANKED BY MEMBERSHIP SIZE)Religion

World

2000 United States

1970 United States

2000United States

2025Christians 1,999,564,000 191,182,000 235,741,000 266,348,500 Muslims 1,888,243,000 800,000 4,131,910 5,290,000 Hindus 811,336,000 100,000 1,031,677 1,500,000 Buddhists 359,982,000 200,000 2,449,570 5,000,000 Ethnoreligionists 228,367,000 0,000 434,851 500,000 Sikhs 23,258,000 1,000 233,820 310,000 Jews 14,434,000 14,434,000 5,621,339 6,100,000 Confucianists 6,299,000 *** *** *** Babi and Baha’i 7,106,000 138,000 753,423 1,150,000 Jains 4,218,000 000 6,959 7,000 Shinto 2,762,000 000 56,220 84,000 Zoroastrians 2,544,000 000 52,721 84,000 Nonreligionists 918,249,000 10,070,000 25,077,844 40,000,000

Agnostics

768,159,000 *** *** ***

Aethists

150,090,000 200,000 1,149,486 1,600,000

The term “major world religion” generally applies to groups that are of major historical and cultural significance. Precisely what should be deemed a major world religion is a matter of some disagreement. Baha’ism may be omitted because it is a recent tradition or mis-classified as an Islamic sect. Zoroastrianism and Shinto may be omitted because they are relatively small and geographically limited. Confucianism and Taoism may be omitted because they are defined as ethical systems rather than religions and have few formal adherents with a primary loyalty to them.

Demographics3

Top Twenty Religions in the United States, 2001

(self-identification, ARIS)

Religion 1990 Est.

Adult Pop. 2001 Est.

ADULT Pop. 2004 Est.

Total Pop. % of U.S. Pop.,

2000 % Change

1990 – 2000 Christianity 151,225,000 159,030,000 224,437,959 76.5% +5% Nonreligious/Secular 13,116,000 27,539,000 38,865,604 13.2% +110% Judaism 3,137,000 2,831,000 3,995,371 1.3% -10% Islam 527,000 1,104,000 1,558,068 0.5% +109% Buddhism 401,000 1,082,000 1,527,019 0.5% +170% Agnostic 1,186,000 991,000 1,398,592 0.5% -16% Atheist 902,000 1,272,986 0.4% Hinduism 227,000 766,000 1,081,051 0.4% +237% Unitarian Universalist 502,000 629,000 887,703 0.3% +25% Wiccan/Pagan/Druid 307,000 433,267 0.1% Spiritualist 116,000 163,710 0.05% Native American Religion 47,000 103,000 145,363 0.05% +119% Baha’i 28,000 84,000 118,549 0.04% +200% New Age 20,000 68,000 95,968 0.03% +240% Sikhism 13,000 57,000 80,444 0.03% +338% Scientology 45,000 55,000 77,621 0.02% +22% Humanist 29,000 49,000 69,153 0.02% +69% Deity (Deist) 6,000 49,000 69,153 0.02% +717% Taoist 23,000 40,000 56,452 0.02% +74% Eckankar 18,000 26,000 36,694 0.01% +44%

Demographics4

Richmond-Petersburg

Metropolitan Area

(self-identification, ARIS)

Religion

Number of

Congregations, 2000

Number of Adherents,

2000

Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection 1 4 American Baptist Churches in the USA 37 25,442 Apostolic Christian Churches (Nazarean) 1 48 Armenian Apostolic Church / Catholicossate of Etchmiadzin 1 400 Assemblies of God 21 8,656 Catholic Church 29 56,743 Christian and Missionary Alliance, The 3 270 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) 22 6,530 Christian Churches and Churches of Christ 19 6,391 Church of God (Anderson, Indiana) 2 175 Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) 12 3,566 Church of God of Prophecy 5 253 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, The 18 6,522 Church of the Brethren 4 363 Church of the Nazarene 13 3,977 Churches of Christ 17 2,372 Community of Christ 1 83 Conservative Congregational Christian Conference 1 109 Episcopal Church 55 25,938 Evangelical Free Church of America, The 2 245 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America 8 4,216 Evangelical Presbyterian Church 1 179 Free Methodist Church of North America 0 0 Friends (Quakers) 3 379 General Association of Regular Baptist Churches 3 778 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America 2 1,365 Holy Orthodox Church in North America 1 40 Independent, Charismatic Churches 4 6,400 Independent, Non-Charismatic Churches 2 2,200 International Church of the Foursquare Gospel 2 193 International Churches of Christ 1 128 International Pentecostal Church of Christ 1 50 International Pentecostal Holiness Church 16 2,615 Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod 10 4,731 Mennonite Church USA 3 305 Moravian Church in America–Southern Province 0 0 National Association of Free Will Baptists 5 519 Orthodox Church in America: Territorial Dioceses 1 67 Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) 64 24,617 Presbyterian Church in America 10 2,689 Primitive Baptist Churches–Old Line 3 0 Reformed Baptist Churches 1 0 Salvation Army, The 2 443 Seventh-day Adventist Church 12 2,478 Southern Baptist Convention 217 145,014 Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations 3 790 United Church of Christ 4 883 United Methodist Church, The 120 66,028 Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches 1 256 Vineyard USA 1 182 Wesleyan Church, The 3 254 Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod 2 128 Bahá’í 4 335 Buddhism 1 0 Hindu 2 0 Jewish Estimate 8

15,350

Muslim Estimate 5 2,686

The population of these 13 counties (or equivalents) in 1990 was 865,640; in 2000 it was 996,512. The total population changed 15.1%. The adherent totals for 1990 (456,519) represent 52.7% of the 1990 population. The adherent totals for 2000 (434,385) include 43.6% of the 2000 population. The totals represent the change in groups that reported in both 1990 and 2000 only.

Source:

Churches and Church Membership in the United States 1990 and Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States 2000.

Demographics5

Religious Bodies Theology Congregations Adherents Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection Evangelical Protestant 1 4 American Baptist Churches in the USA Mainline Protestant 37 25,442 Apostolic Christian Churches (Nazarean) Evangelical Protestant 1 48 Armenian Apostolic Church / Catholicossate of Etchmiadzin Mainline Protestant 1 400 Assemblies of God Evangelical Protestant 21 8,656 Bahá’í Other Theology 4 335 Buddhism Other Theology 1 0 Catholic Church Catholic 29 56,743 Christian and Missionary Alliance, The Evangelical Protestant 3 270 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) Mainline Protestant 22 6,530 Christian Churches and Churches of Christ Evangelical Protestant 19 6,391 Church of God (Anderson, Indiana) Evangelical Protestant 2 175 Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee) Evangelical Protestant 12 3,566 Church of God of Prophecy Evangelical Protestant 5 253 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, The Other Theology 18 6,522 Church of the Brethren Evangelical Protestant 4 363 Church of the Nazarene Evangelical Protestant 13 3,977 Churches of Christ Evangelical Protestant 17 2,372 Community of Christ Evangelical Protestant 1 83 Conservative Congregational Christian Conference Evangelical Protestant 1 109 Episcopal Church Mainline Protestant 55 25,938 Evangelical Free Church of America, The Evangelical Protestant 2 245 Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Mainline Protestant 8 4,216 Evangelical Presbyterian Church Evangelical Protestant 1 179 Free Methodist Church of North America Evangelical Protestant 0 0 Friends (Quakers) Mainline Protestant 3 379 General Association of Regular Baptist Churches Evangelical Protestant 3 778 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America Orthodox 2 1,365 Hindu Other Theology 2 0 Holy Orthodox Church in North America Orthodox 1 40 Independent, Charismatic Churches Evangelical Protestant 4 6,400 Independent, Non-Charismatic Churches Evangelical Protestant 2 2,200 International Church of the Foursquare Gospel Evangelical Protestant 2 193 International Churches of Christ Evangelical Protestant 1 128 International Pentecostal Church of Christ Evangelical Protestant 1 50 International Pentecostal Holiness Church Evangelical Protestant 16 2,615 Jewish Estimate Other Theology 8 15,350 Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod Evangelical Protestant 10 4,731 Mennonite Church USA Evangelical Protestant 3 305 Moravian Church in America–Southern Province Mainline Protestant 0 0 Muslim Estimate Other Theology 5 2,686 National Association of Free Will Baptists Evangelical Protestant 5 519 Orthodox Church in America: Territorial Dioceses Orthodox 1 67 Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) Mainline Protestant 64 24,617 Presbyterian Church in America Evangelical Protestant 10 2,689 Primitive Baptist Churches–Old Line Evangelical Protestant 3 0 Reformed Baptist Churches Evangelical Protestant 1 0 Salvation Army, The Evangelical Protestant 2 443 Seventh-day Adventist Church Evangelical Protestant 12 2,478 Southern Baptist Convention Evangelical Protestant 217 145,014 Southwide Baptist Fellowship Evangelical Protestant 2 0 Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations Other Theology 3 790 United Church of Christ Mainline Protestant 4 883 United Methodist Church, The Mainline Protestant 120 66,028 Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches Mainline Protestant 1 256 Vineyard USA Evangelical Protestant 1 182 Wesleyan Church, The Evangelical Protestant 3 254 Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod Evangelical Protestant 2 128 Totals (Unadjusted)*: 792 434,385 Total (Adjusted)**: 613,810

Tenrikyō

TENRIKYŌ TIMELINE

1798 (18th day of 4th month, lunar calendar): Miki was born into the Maegawa family in Sanmaiden Village, Yamabe County, Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture).

1810: Miki married Nakayama Zenbei of Shoyashiki Village.

1816: Miki attended a training course known as the fivefold transmission (gojū sōden) at the Zenpuku Temple of Jōdo Shin Buddhism.

1837: Miki’s son, Shūji, began to suffer from pains in his legs. Nakano Ichibei, a mountain ascetic (shugenja), performed prayer rituals (kitō) over the next twelve months.

1838 (23rd day of 10th month): An incantation (yosekaji) was performed for Shūji with Miki as the medium. During the incantation, Miki went into trance and had a revelation from Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto.

1838: (26th day of 10th month): Miki was settled as the Shrine of Tsukihi (tsukihi no yashiro), marking the founding of the religious teaching. She remained in seclusion for the next three years.

1853: Zenbei passed away at the age of sixty-six. Kokan, Miki’s youngest daughter, went to Naniwa (present-day Osaka) to spread the name of Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto.

1854: Miki’s daughter’s childbirth marked the beginning of the “Grant of Safe Childbirth” (obiya yurushi).

1864: Iburi Izō of Ichinomoto Village came to see Miki for the first time.

1864: The construction of the Place for the Service (tsutome basho) began.

1865: Miki went to Harigabessho Village to confront Sukezō, who claimed the religious authority in place of Miki.

1866: Miki began to teach the songs and hand movements for the service (tsutome).

1867: Shūji gained official permission to conduct religious activities from the Yoshida Administrative Office of Shinto (Yoshida jingi kanryō).

1869: Miki began writing the Ofudesaki (The Tip of the Writing Brush).

1874: Miki began to bestow the truth of the Sazuke (sazuke no ri) for physical healing.

1875: The identification of the Jiba (jiba sadame) took place.

1876: Shūji obtained a license to run a steam bath and an inn as a way to allow worshippers to gather.

1880: Tenrin-Ō-Kōsha was formally inaugurated under the auspices of the Jifuku Temple.

1881: Shūji passed away at the age of sixty-one.

1882: The steam bath and the inn were closed down. Tenrin-Ō-Kōsha was officially dismissed by the Jifuku Temple.

1882: Miki completed the writing of the Ofudesaki.

1885: The movement to establish the church (kyōkai setsuritsu undō) began to be conducted with Shinnosuke as the leader.

1887 (26th of 1st month by the lunar calendar): Miki “withdrew from physical life” (utsushimi wo kakushita) at the age of ninety.

1887: Iburi Izō became the Honseki and began to deliver divine directions (osashizu) as well as bestow the Sazuke on behalf of Miki.

1888: Shintō Tenri Kyōkai was established in Tokyo under the direct supervision of the Shinto Main Bureau. The location was subsequently moved back to present-day Tenri.

1888: The Mikagura-uta (The Songs for the Service) was officially published by Tenri Kyōkai.

1896: The tenth anniversary of the foundress was observed.

1896: The Home Ministry issued its Directive No. 12 to enforce strict control on Tenri Kyōkai.

1899: The movement for sectarian independence (ippa dokuritsu undō) began.

1903: Tenrikyō kyōten (The Doctrine of Tenrikyō), also known as Meiji kyōten, was published.

1907: Iburi Izō passed away, marking the official end of the era of the divine directions.

1908: Tenri Seminary (Tenri kyōkō) and Tenri Junior High School were founded respectively.

1908: Tenrikyō gained sectarian independence from the Shinto Main Bureau.

1908: Nakayama Shinnosuke, the first Shinbashira, became the superintendent (kanchō) of Tenrikyō.

1910: Tenrikyo Women’s Association (Tenrikyō fujinkai) was founded.

1914: Nakayama Shinnosuke, the first Shinbashira, passed away at the age of forty-eight.

1915: Nakayama Shōzen became the superintendent of Tenrikyō at the age of nine. (Yamazawa Tamezō served as the acting superintendent until Shōzen came of age in 1925.)

1918: Tenrikyo Young Men’s Association (Tenrikyō seinenkai) was founded.

1925: Tenri School of Foreign Languages (Tenri gaikokugo gakkō) was established along with what would later become Tenri Central Library (Tenri toshokan). Also, Tenrikyō Printing Office (Tenrikyō kyōchō insatsusho) and the Department of Doctrine and Historical Materials (Kyōgi oyobi shiryō shūseibu) were established.

1928: The Ofudesaki was officially published.

1938: Nakayama Shōzen announced the adjustment (kakushin) to comply with the state authority’s demand.

1945 (August 15): Nakayama Shōzen announced the restoration (fukugen) of the teaching.

1946: The Mikagura-uta was published and offered to local churches.

1948: The Ofudesaki, accompanied with commentaries, as well as the first volume of the Osashizu (The Divine Directions) were published and offered to local churches.

1949: Tenri School of Foreign Languages was reorganized as Tenri University.

1949: Tenrikyō kyōten (The Doctrine of Tenrikyō) was officially published.

1953: Nakayama Shōzen announced the construction of Oyasato-yakata Building-complex (Oyasato yakata).

1954: Tenri City was instated.

1966: Tenrikyo Children’s Association (Tenrikyō shōnenkai) was established.

1967: Nakayama Shōzen, the second Shinbashira, passed away at the age of sixty-two. Nakayama Zenye became the third Shinbashira.

1970: Tenrikyō left the Sect Shinto Union (Kyōha Shintō rengōkai).

1986: The centennial anniversary of the foundress was observed.

1998: Nakayama Zenji became the fourth Shinbashira

1998: Tenrikyō held the “Tenrikyo-Christian Dialogue” between Tenri University and the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome.

2002: Tenrikyō held the “Tenrikyo-Christian Dialogue II” between Tenri University and the Pontifical Gregorian University in Tenri.

2013: Nakayama Daisuke became the designate successor to the position of the Shinbashira.

2014: Nakayama Zenye, the third Shinbashira, passed away at the age of eighty-two.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

On the 18th day of the 4th month in 1798, Miki was born as a daughter of Maegawa Hanshichi in Sanmaiden Village, Yamabe County, Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture). She was known to be diligent in household work and was a devout adherent of Jōdo Shin Buddhism since her childhood. In 1810, she married Nakayama Zenbei of a nearby village at the age of thirteen and was entrusted with all the household work of Nakayama family in 1813. She gave birth to her first child, Shūji, in 1821 and then to five daughters two of whom died early (Tenrikyo Doyusha Publishing Company [TDPC] 2014:1-27).

In 1837, Shūji was afflicted with pain in his legs, and Nakayama family had Nakano Ichibei, a shugenja (ritual practitioner associated with a mountain religious sect), perform prayer rituals (kitō) for him over the next twelve months. On the 23rd day of the 10th month, an incantation (yosekaji) was performed for Shūji with Miki acting as spirit medium, during which God descended into Miki’s body and claimed to take Miki as the “Shrine of God” (kami no yashiro). After three days of fierce negotiation between God and the members of Nakayama family, Miki was acknowledged as the Shrine of God on the 26th day of the 10th month upon the consent by her husband, thus marking the founding of the teaching (TDPC 2014:28-39). In the current doctrinal view of Tenrikyō, Miki’s life for the next fifty years is referred to as the Divine Model (hinagata), and it is believed that her mind was completely in accordance with God’s will. In contrast, Shimazono (1998) has emphasized that Miki’s religious thought developed through a gradual process of self-inquiry rather than as a result of sudden revelation.

For the next three years or so, Miki secluded herself in a storehouse and later began giving away her belongings and her family’s possessions to the extent of eventually dismantling the house building. Miki’s unusual actions caused distrust from her relatives and villagers and led the family into poverty. In 1854, she began what is now known as the Grant of Safe Childbirth (obiya yurushi), which was intended to assure safe childbirth without observing traditional customs and taboos relating to women’s defilement (kegare) (TDPC 2014:40-70). In addition to the significance of breaking gender-related taboos, Miki may have used this practice to allow those around her to understand the idea that divine providence is most evident in the body of a woman in pregnancy, which embodies the fundamentally passive nature of human body (Watanabe 2015:27). Along with crossing the boundaries of conventional customs, Miki is said to have interacted with people seeking healings including those of outcaste areas (buraku). The breaching of these taboos increased her alienation from others in her village (Ikeda 2006:82-124). Also, doctors and mountain ascetics reportedly confronted Miki, with violence at times, as she gained adherents from those religious communities (TDPC 2014:90-96). This was also related to the fact that Miki’s presence as a female religious leader challenged the male-oriented religious authority of mountain ascetics (Hardacre 1994). As a way to avoid these confrontations, Miki’s followers (despite her reluctance) sought to gain official authorization from the Yoshida Administrative Office of Shintō (Yoshida jingi kanryō) in Kyoto so that they could hold gatherings at their private residence. This official authorization was granted in 1867 but was later voided when the Shintō office was abolished in 1870 (TDPC 2014:99-106).

Following the dismantling of the main house, Miki embarked on the construction of the tsutome basho (the Place for performing religious services) in 1864 with the initiatives of early followers especially Iburi Izō, who was a carpenter by profession (TDPC 2014:71-89). In 1866, Miki began to teach the form of service (tsutome) that was to be used in her movement. The service involves  songs and accompanying hand gestures and dance that are performed in tune with the melodies of nine musical instruments. (See the Ritual section for more details.) This ritual would come to be performed at the Jiba, a site which Miki identified in 1875 in the premises of the Nakayama residence to mark the place of original human conception (TDPC 2014:107-18). In addition to making arrangements for the ritual, Miki began writing what would later come to be called the Ofudesaki (The Tip of the Writing Brush). Written from 1869 to 1882, the text contains a total of 1,711 verses in seventeen parts written in the waka style of poetry (TDPC 2014:119-23). Meanwhile, Miki began to mark herself out as the Shrine of God by wearing a red cloth (akaki) in 1874, and in the same year she began to bestow in various forms the truth of the Sazuke (the Divine Grant), which allowed her followers to conduct healing prayers for those suffering from illness (TDPC 2014:145-46). In 1881, Miki began the construction of the Kanrodai (the Stand for the Heavenly Dew), a hexagonal stand of thirteen stone blocks that demarcates the Jiba. A wooden model of the Kanrodai had been already made by Iburi Izō as early as in 1873 and was placed at the Jiba in 1875, the same year in which Miki identified the Jiba. The construction of the stone-made Kanrodai came to halt in 1882, however, when the police confiscated the stones from Miki’s house (TDPC 2014:221-32). From about 1880-1881, Miki began to tell her followers various stories containing her teachings, and the record of the stories as written by her followers are referred to as kōki (the Divine Record) (TDPC 2014:233-42).

songs and accompanying hand gestures and dance that are performed in tune with the melodies of nine musical instruments. (See the Ritual section for more details.) This ritual would come to be performed at the Jiba, a site which Miki identified in 1875 in the premises of the Nakayama residence to mark the place of original human conception (TDPC 2014:107-18). In addition to making arrangements for the ritual, Miki began writing what would later come to be called the Ofudesaki (The Tip of the Writing Brush). Written from 1869 to 1882, the text contains a total of 1,711 verses in seventeen parts written in the waka style of poetry (TDPC 2014:119-23). Meanwhile, Miki began to mark herself out as the Shrine of God by wearing a red cloth (akaki) in 1874, and in the same year she began to bestow in various forms the truth of the Sazuke (the Divine Grant), which allowed her followers to conduct healing prayers for those suffering from illness (TDPC 2014:145-46). In 1881, Miki began the construction of the Kanrodai (the Stand for the Heavenly Dew), a hexagonal stand of thirteen stone blocks that demarcates the Jiba. A wooden model of the Kanrodai had been already made by Iburi Izō as early as in 1873 and was placed at the Jiba in 1875, the same year in which Miki identified the Jiba. The construction of the stone-made Kanrodai came to halt in 1882, however, when the police confiscated the stones from Miki’s house (TDPC 2014:221-32). From about 1880-1881, Miki began to tell her followers various stories containing her teachings, and the record of the stories as written by her followers are referred to as kōki (the Divine Record) (TDPC 2014:233-42).

In the aftermath of the Meiji Restoration (1868), Miki and her movement encountered surveillance and prosecution from political authorities as a non-authorized religious group. She was arrested eighteen times between 1875 and 1886. To mitigate the tension, Shūji obtained a license to run a steam bath and an inn so as to allow Miki’s followers to gather at the residence. Moreover, he managed to gain authorization from the Jifuku Temple of Kongōsan and established Tenrin-Ō-Kōsha as a legitimate sub-organization of the Jifuku Temple in 1880, although the Kōsha would be abolished two years later along with the bath and inn (TDPC 2014:206-77). As was the case with the official authorization from Yoshida Shintō, Miki consistently opposed any move to comply with the authorities in ways that could compromise her teaching. In such circumstances, Nakayama Shinnosuke, Miki’s grandson who had become the head of Nakayama family, began an initiative to establish an independent church (kyōkai setsuritsu undō) in 1882. He was granted the permission to establish a church under the direct supervision of the Shinto Main Bureau (Shintō honkyoku) in 1885, but the official authorization from the government was yet to be achieved. There was an internal tension between Miki, who urged her followers to perform the service, and Shinnosuke and other followers, who were keen to gain official authorization so as to prevent any suppression of Miki. This tension was resolved on the lunar calendar date of first month 26th, 1887 (February 18th in Gregorian calendar), when followers performed the service to comply with the request of Miki. Soon after the service ended, Miki passed away at the age of ninety. In Tenrikyō, it is believed that Miki withdrew from physical life (utsushimi wo kakushita) and is still alive (zonmei) overseeing the movement as well as working for the salvation of human beings (TDPC 2014:278-319). As a way to embody this doctrinal idea, it is said that she is served with three meals a day and a bath is run for her, among other things, at the Foundress’ Sanctuary of Tenrikyo Church Headquarters (fieldwork observation). Also related to this notion is that her photograph has never been made public by the Church Headquarters, and this also serves as a way to preserve the sacredness of Miki as the Shrine of God (Nagaoka 2016).

After the death of Miki, Iburi Izō became the Honseki (main seat; i.e. a person who bestows the Sazuke on behalf of Miki) while Shinnosuke served the role of the Shinbashira (central pillar; i.e., the spiritual and administrative leader of the movement). In 1888, the religious movement gained official authorization as Shintō Tenri Kyōkai under the direct supervision of the Shinto Main Bureau in 1888. This led to formations of many churches under Tenri Kyōkai, amounting to some 1,300 churches by 1896. Also in 1888, Tenri Kyōkai published the Mikagura-uta (The Songs for the Service), which is the compilation of the songs taught by Miki. The rapid growth of the religious movement and its focus on faith healing, however, in turn invited criticism from the wider society, particularly from journalists that labeled the group as an “evil cult” (inshi jakyō) on the grounds that the religious movement emphasized superstition and magical healings over modern medical treatment. Similar public criticism was also directed against other new religious groups including Renmonkyō. This social tension developed to the point where the Home Ministry issued its Directive No. 12 in 1896, which enforced strict control and surveillance of the religious movement. As a way to respond to the public scrutiny and criticism, Tenri Kyōkai began to campaign for sectarian independence (ippa dokuritsu undō) in 1899. To meet the government’s criteria for a legitimate religious organization, the group developed an institutionalized religious organization and a systematized doctrine known as the Meiji version of Tenrikyō kyōten (The Doctrine of Tenrikyō), which complied with the government’s regulation that required religious doctrines to be in line with the State Shinto (kokka Shintō). In 1908, the group was granted permission to become an independent religious organization as one of the recognized religions in the thirteen Sect Shinto sects (kyōha shintō jūsanpa) (Astley 2006:100; Nagaoka 2015:75-77; TOMD 1998:56-65).

After gaining sectarian independence, the religious group, now with the name Tenrikyō, enjoyed a relatively peaceful time with regards to political and social pressure under the leadership of Nakayama Shinnosuke, who was the Shinbashira as well as the superintendent (kanchō) of Tenrikyō. With official sanction, Tenrikyō revitalized its efforts of propagation in the subsequent years, particularly by organizing public lectures in such places as factories across the country. This was influenced by the government’s policy of kokumin kyōka (national edification) marked by the initiative known as sankyō kaidō (three religions conference) in 1912, which brought together the representatives of Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian sects for the purpose of strengthening social order in Japan. As a result of the propagation efforts, Tenrikyō experienced rapid growth in the years leading up to 1920, especially in urban regions with a high population growth due to the influx of people from rural areas. In the meantime, Nakayama Shōzen became the superintendent of Tenrikyō in 1915 after the death of Shinnosuke in the previous year (Lee 1994:39-44; Ōya 1996:59-72; TOMD 1998:65-75).

In the following years, Tenrikyō developed further and established various sub-organizations. In 1925, Tenri School of Foreign Languages (Tenri Gaikokugo Gakkō) was established along with what would later become Tenri Central Library (Tenri toshokan). The language school was intended to support followers going overseas for missionary work, which had already begun toward the end of 1890s in Japan’s neighboring countries and regions such as Korea, Manchuria, and Taiwan as well as in immigrant-based regions including Hawaiʻi and the U.S. West Coast. Tenrikyō also established Tenrikyō Printing Office (Tenrikyō kyōchō insatsusho) and the Department of Doctrine and Historical Materials (Kyōgi oyobi shiryō shūseibu) as well as educational facilities such as a nursery, kindergarten, and elementary school. The Osashizu (The Divine Directions; a compilation of divine messages delivered through Iburi Izō) and the Ofudesaki began to be published in 1927 and 1928, respectively. In 1933 and 1934, the construction of the Foundress’s Sanctuary (Kyōsoden) and the South Worship Hall of the Main Sanctuary (Shinden) were completed, respectively, and the Kagura Service was performed around the model Kanrodai. These doctrinal and ritual developments, however, came to be hampered by the initiative known as the adjustment (kakushin) in 1939, which came in the wake of the National Mobilization Act (kokka sōdōin hō). To comply with the state’s demand in the face of war efforts, Tenrikyō made various changes including the removal of certain verses from the Mikagura-uta as well as withdrawing the Ofudesaki and the Osashizu from circulation (TOMD 1998:71-75). While Tenrikyō’s official discourse claims that the religious organization complied with the state on the surface, Nagaoka (2015) has demonstrated how Tenrikyō’s doctrines and practices were (re-)configured through the interaction with the state after the death of Miki. (See Issues/Challenges below for a related discussion.)

In the immediate aftermath of World War II on August 15, 1945, Nakayama Shōzen announced the restoration (fukugen) of Tenrikyō’s teachings into the one as taught by the foundress. He restored the Kagura Service in the same year, and over the next years he published the three scriptures, namely the Ofudesaki (1948), the Mikagura-uta (1946), and the Osashizu (1949), all of which had been prohibited by the government during the war. In 1949, he published Tenrikyō kyōten based on the three scriptures to replace the Meiji version of the doctrine. As a biography of the foundress, he published Kōhon Tenrikyō kyōsoden (the manuscript edition of the Life of Oyasama, Foundress of Tenrikyo) in 1956. In 1953, Shōzen announced the construction of Oyasato-yakata Building-complex (Oyasato yakata) that would surround the sanctuary to embody a model of the Joyous Life world. In further advancing Tenrikyō’s propagation, Shōzen made an official announcement of the promotion of an overseas mission in 1961, seeking to spread the name of the religion in various parts of the world (TOMD 1998:76-80)

With the death of the second Shinbashira in 1967, Nakayama Zenye, Shōzen’s son, became the third Shinbashira. Under his leadership, Tenrikyo started to place emphasis on the religious education of church members. While following in the footsteps of his predecessor who had opened a broad path to the development of the tradition in various fields, the third Shinbashira primarily focused on enhancing the quality of each church community through seminars on doctrine as well as the service performance. In the meantime, Tenrikyō left the Sect Shintō Union (Kyōha Shintō rengōkai) in 1970 and later abolished some of the Shintō-related materials such as himorogi (or more precisely masakaki, a pair of sacred tree branches to which five-coloured silk clothes as well as a ritual sword, mirror, and magatama beads are attached) and shimenawa (a rope that marks the sacred space) in 1976 and 1986, respectively. It also stopped conducting the ritual of tamakushi hōken in 1986. Moreover, the construction of the East and West Worship Halls of the Main Sanctuary was completed in 1984. In 1998, Nakayama Zenye passed on leadership to his son, Nakayama Zenji, who now serves as the fourth Shinbashira. Meanwhile, Tenrikyō held two events of “Tenrikyo-Christian Dialogue” between Tenri University and the Pontifical Gregorian University, the first time in Rome in 1998 and second time in Tenri in 2002. The two events each involved a symposium that brought together academics from both universities as well as some external scholars to exchange theological/doctrinal views on common themes including revelation, salvation, family, and education. In 2013, Nakayama Daisuke, Zenji’s adopted son, became the designated successor to the position of the Shinbashira. In 2014, Nakayama Zenye, the third Shinbashira, passed away at the age of eighty-two (Tenri Daigaku Fuzoku Oyasato Kenkyūsho 1997:286; Tenrikyō Dōyūsha 2016:112; 122, 142, 166, 175, 197, 199; Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no Taiwa II Soshiki Iinkai 1998; Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no Taiwa II Soshiki Iinkai 2005; TOMD 1998:80-88).

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

The underlying principle of Tenrikyō’s present official teaching is prescribed in Tenrikyō kyōten, the postwar doctrinal text first published in 1949 with the authorization of the second Shinbashira and was later translated into English with the title The Doctrine of Tenrikyo.

The doctrine states that human beings were created by the divine being called Tenri-Ō-no-Mikoto, also referred to as God the Parent (oyagami). In the story of human creation known as the Truth of Origin (Moto no ri), which is also the title of one of the chapters of the doctrinal text, the human creation is said to have taken place 900,099,999 years before the founding of the teaching in 1838 (Tenrikyo Church Headquarters [TCH] 1993:20-23). The story teaches that God the Parent created human beings for the purpose of seeing them lead the Joyous Life (yōki gurashi), the happy, self-less state of human life to be attained in the present world rather than in an afterlife (TCH 1993:12-19). In this view of salvific truth, which expresses a this-worldly orientation that is also characteristic of other Japanese new religions, the mind (kokoro) is defined as the basis of human existence and is indeed considered to be the only thing that belongs to human beings. This is expressed in a commonly cited phrase, “the mind alone is yours” (kokoro hitotsu ga waga no ri) (TCH 1993:52). The human body, which exists in relation to the mind, is described as a “thing lent, a thing borrowed” (kashimono karimono) from God the Parent. The official interpretation of this expression is that the human body is being kept alive by God’s providence (TCH 1993:50-52). The divine providence with which human beings are sustained is referred to as God the Parent’s “complete providence” (jūzen no shugo), which delineates ten aspects of God’s workings relating to the creation and sustenance of human life as the entirety of divine functioning in the human body (TCH 1993:30-32). This relationship between the human body and God further extends to an idea that the existence of all things including human beings and the physical world are reliant upon the providence of God (TCH 1993:32). Described as such, the concept of God is viewed as a synonym of the phenomenal world itself, an idea that is encapsulated in a scriptural phrase, “This universe is the body of God” (Ofudesaki III:40, 135).

In light of this ontological view, the human mind comes to play a key role in Tenrikyō’s soteriological discourse. In the process toward the realization of the Joyous Life, the mind is considered to be the determinant of human experiences and all the phenomena in the world. In this view, God the Parent is believed to provide human beings with divine blessings, such as good health or harmonious relationships with others, depending on the ways in which they use their minds. In this way, the human mind is believed to be able to affect the ways in which divine blessings are provided to human beings. The doctrine makes a distinction between what counts as a proper use of the mind and what does not. The doctrine states that, in order to achieve the world of joyousness, human beings are required to rid themselves of what is called the “dusts of the mind” (kokoro no hokori), a metaphor signifying self-centered thoughts that are considered to be the cause of negative occurrences such as illnesses and troubles. These dusts of the mind are miserliness, covetousness, hatred, self-love, grudge-bearing, anger, greed, and arrogance, while falsehood and flattery should also be avoided (TCH 1993:53). In a symbolic sense, these dusts are believed to accumulate and eventually develop into “causality” (innen), which affects the conditions or circumstances of one’s life in an unwanted manner in the present life and, after one passes away for rebirth, in the next life (TCH 1993:50-57). The doctrine states, however, that these negative phenomena are not punishments per se but rather “divine guidance” (tebiki) with which God the Parent urges human beings to purify their self-centered thoughts (TCH 1993:45-49).

It is postulated that, when the dust of the mind is completely purified, human beings can attain the quality of “true sincerity” (makoto shinjitsu), which represents a state of mind that fully accords with God the Parent’s intention that human beings live their lives by helping one another. In the process of purification, human beings ought to engage in “hinokishin,” which is defined as a selfless, thankful action based on the mind of “joyous acceptance” (tanno), a state of mind that seeks to accept any life events as manifestation of God’s guidance with a sense of joy and spiritedness (TCH 1993:60-83). Having attained the mind of true sincerity, human beings can experience the state of Joyous Life. In this manner, Tenrikyō’s soteriological discourse maintains that one can experience joy in the phenomenal world by perceiving things just as they appear. With their minds purified, human beings can find manifestations of divine blessings in what seem to be daily mundane occurrences and, with that very awareness, can attain the mind of joyousness.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Tenrikyō has developed an array of ritual practices that relate to the soteriological discourse in its doctrine. The most important  formalized ritual is called the service (tsutome), which involves symbolic ritual dance and the tune of accompanying nine musical instruments that are performed along the songs based on the words in the Mikagura-uta. [Image at right] At the monthly service on the twenty-sixth of every month (which commemorates the dates of the founding of the teaching as well as the “physical withdrawal” of the foundress) and at other grand services, the Church Headquarters conducts a ritual known as the Kagura Service (kagura-zutome), the name of which derives from Shinto’s traditional theatrical dance known as kagura. In the Kagura Service, ten performers conduct the ritual dance with the Kanrodai as the center while wearing Kagura masks (kagura men) symbolizing the mythical figures described in the Truth of Origin. The service is intended to be a symbolic expression of the Joyous Life as well as the divine providence of God the Parent at the time of the creation of humankind. The Kagura Service is then followed by the Dance with Hand Movements (teodori), which is performed by three men and three women on the dais of the Main Sanctuary. The service is also conducted at a monthly service of local churches in a slightly different form, with six performers dancing to the tune of the same nine musical instruments without Kagura masks. In both cases, the performers portray and spiritually enact religious symbols through the use of their bodies in the Service. Aside from the monthly and grand services, there are also morning and evening services, which are conducted both at the Church Headquarters and at local churches throughout the year, with only the seated service (suwari-zutome) being performed with three of the nine musical instruments (TOD 2004:48-57, 2010:375-382; TOMD 1998:37-40).

formalized ritual is called the service (tsutome), which involves symbolic ritual dance and the tune of accompanying nine musical instruments that are performed along the songs based on the words in the Mikagura-uta. [Image at right] At the monthly service on the twenty-sixth of every month (which commemorates the dates of the founding of the teaching as well as the “physical withdrawal” of the foundress) and at other grand services, the Church Headquarters conducts a ritual known as the Kagura Service (kagura-zutome), the name of which derives from Shinto’s traditional theatrical dance known as kagura. In the Kagura Service, ten performers conduct the ritual dance with the Kanrodai as the center while wearing Kagura masks (kagura men) symbolizing the mythical figures described in the Truth of Origin. The service is intended to be a symbolic expression of the Joyous Life as well as the divine providence of God the Parent at the time of the creation of humankind. The Kagura Service is then followed by the Dance with Hand Movements (teodori), which is performed by three men and three women on the dais of the Main Sanctuary. The service is also conducted at a monthly service of local churches in a slightly different form, with six performers dancing to the tune of the same nine musical instruments without Kagura masks. In both cases, the performers portray and spiritually enact religious symbols through the use of their bodies in the Service. Aside from the monthly and grand services, there are also morning and evening services, which are conducted both at the Church Headquarters and at local churches throughout the year, with only the seated service (suwari-zutome) being performed with three of the nine musical instruments (TOD 2004:48-57, 2010:375-382; TOMD 1998:37-40).

Another prominent ritual is a healing rite known as the Sazuke (the Divine Grant), which is performed to pray for the recovery of  someone who is afflicted with illnesses and disorders. The Sazuke involves recitation of the name of God and corresponding hand gestures, and the ritual performer strokes the afflicted part of the body of the person concerned. The Sazuke can only be administered by a Yoboku (an initiated member), who has received the truth of the Sazuke (sazuke no ri) from the Foundress through the Shinbashira after going through a systematized procedure of attending a lecture known as Besseki for a total of nine times. The Besseki lecture outlines basic tenets of Tenrikyō, including the Truth of Origin, the dusts of the mind, the body as a thing lent, thing borrowed, the Divine Model of the Foundress, the significance of the service and the Sazuke, and other topics. Through attending the series of lectures, which has the same content each time, the listener is expected to cultivate an orientation of the mind that desires the salvation of others for the rest of his or her life. Compared to the service, which is a collective ritual embodiment of the principle of God the Parent’s providence, the Sazuke is primarily an individual ritual performance that occurs between two persons. The efficacy of the healing ritual is believed to rely upon the sincerity of the one who administers the Sazuke and that of the one who receives it, thus corresponding to the doctrinal claim that the mind constitutes the fundamental basis of human experiences. Because of its nature as a healing ritual, the Sazuke is used by Tenrikyō missionaries to spread their religious teachings to non-followers (TOMD 1998:40-43; TOD 2004:58-59).

someone who is afflicted with illnesses and disorders. The Sazuke involves recitation of the name of God and corresponding hand gestures, and the ritual performer strokes the afflicted part of the body of the person concerned. The Sazuke can only be administered by a Yoboku (an initiated member), who has received the truth of the Sazuke (sazuke no ri) from the Foundress through the Shinbashira after going through a systematized procedure of attending a lecture known as Besseki for a total of nine times. The Besseki lecture outlines basic tenets of Tenrikyō, including the Truth of Origin, the dusts of the mind, the body as a thing lent, thing borrowed, the Divine Model of the Foundress, the significance of the service and the Sazuke, and other topics. Through attending the series of lectures, which has the same content each time, the listener is expected to cultivate an orientation of the mind that desires the salvation of others for the rest of his or her life. Compared to the service, which is a collective ritual embodiment of the principle of God the Parent’s providence, the Sazuke is primarily an individual ritual performance that occurs between two persons. The efficacy of the healing ritual is believed to rely upon the sincerity of the one who administers the Sazuke and that of the one who receives it, thus corresponding to the doctrinal claim that the mind constitutes the fundamental basis of human experiences. Because of its nature as a healing ritual, the Sazuke is used by Tenrikyō missionaries to spread their religious teachings to non-followers (TOMD 1998:40-43; TOD 2004:58-59).

As is implied by the particular locality associated with the Kagura Service and the bestowal of the Sazuke, Tenrikyō places a strong emphasis on the significance of the Jiba as the origin of human life as well as the source of salvation. This cosmological centrality of the Jiba in the doctrine is largely embodied in the religious practice of returning to the Jiba (ojiba gaeri). Also referred to as the Pilgrimage to the Jiba in English translation, this religious practice is described metaphorically as a journey to return to the Home of the Parent (oyasato) of all humanity (TOD 2010:137-138, 168-171). This is indeed very much emphasized in the current Japanese official website of Tenrikyo Church Headquarters (Tenrikyō kyōkai honbu), particularly the web page intended for non-followers (Personal note).

Returning to the Jiba can take place as a journey of individual persons or a group and may involve participation in associated and ceremonies along with the most important meaning of visiting the sacred place itself. In the sense of pilgrimage, Tenrikyō followers from all walks of life from different regions and countries come together at the Jiba as fellow children of God and pray for the realization of the Joyous Life during the service (Inoue 2013:177; cf. Ellwood 1982). Aside from the services conducted at the Jiba, Tenrikyo Church Headquarters hold various kinds of training courses for followers including the Spiritual Development Course (shūyōka) as well as conventions and other events of Tenrikyō associations such as the Young Men’s Association (seinenkai), the Women’s Association (fujinkai), the Student Association (gakuseikai), and the Children’s Association (shōnenkai). Further solidifying the centrality of the Jiba are educational and social welfare institutions built around the Church Headquarters, with a full lineup of facilities from kindergarten to university as well as, for instance, Tenri Yorozu-Sodansho Foundation’s Ikoi no Ie Hospital (TOMD 1998:100-27). [Image at right] Furthermore, the religious organization holds large anniversary events for the foundress on (and around) January 26 every ten years, with the latest one being the 130th anniversary as observed on January 26, 2016. This special event brings large numbers of people to the Jiba as an occasion to renew their commitment to follow the foundress’ teaching.

(seinenkai), the Women’s Association (fujinkai), the Student Association (gakuseikai), and the Children’s Association (shōnenkai). Further solidifying the centrality of the Jiba are educational and social welfare institutions built around the Church Headquarters, with a full lineup of facilities from kindergarten to university as well as, for instance, Tenri Yorozu-Sodansho Foundation’s Ikoi no Ie Hospital (TOMD 1998:100-27). [Image at right] Furthermore, the religious organization holds large anniversary events for the foundress on (and around) January 26 every ten years, with the latest one being the 130th anniversary as observed on January 26, 2016. This special event brings large numbers of people to the Jiba as an occasion to renew their commitment to follow the foundress’ teaching.

In addition to these formal rituals, there are some less structured, day-to-day practices that are based on doctrinal concepts. One of them is hinokishin, which normally takes the form of social engagement such as litter picking in public places, cleaning public facilities, etc. These actions of hinokishin are seen to be an expression of gratitude to God for the blessings the followers receive on a daily basis and in effect serve as a way to reach out to the wider society (fieldwork observation). At a more organized level, Tenrikyō has been organizing what is known as the Disaster Relief Hinokishin Corps (saigai kyūen hinokishin tai) to regions in Japan (and in recent years in Taiwan) in the wake of major natural disasters since early twentieth century, including the Great Hanshin Earthquake (1995) and the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami (2011). (See the Issues/Challenges section for a related discussion.)

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

Tenrikyō is generally considered to be one of the largest Japanese new religious organizations, particularly among the ones that came into being at the turn of Japan’s modernization. Though the number of adherents is hard to grasp in Tenrikyō, which does not have a proper rite of passage apart from attendance at the Besseki lecture, a statistical review published by the religious organization based on reports from local churches claims 1,216,137 adherents in and outside Japan combined as of 2008. The number is slightly lower than that of 1986, the year of foundress’s centennial anniversary, when it marked the highest number in the post-war period at 1,687,220 (Tenrikyō Omote Tōryōshitsu Chōsa Jōhōka 2008:8). As has been briefly mentioned in the history of the religious group, Tenrikyō had experienced a higher growth in the number of adherents during the pre-war period. In 1896, for example, it claimed the membership of 3,137,113 based on the number of people who paid the membership fee (kōkin) (Arakitōryō Henshūbu 2002:38). Over the course of its development, Tenrikyō has spread to different parts of Japan from Hokkaidō to Okinawa, with church communities mainly concentrated in regions such as Kinki and Setouchi regions, which experienced rapid population growth as a result of industrial development around 1920s (Ōya 1996:71; Tsujii 1997).

Aside from its presence in its country of origin, Tenrikyō has expanded to more than thirty overseas countries and regions (TOD 2009), with the first move taking place in the Korean Peninsula in as early as 1893 (Kaneko K. 2000). Much of its church following is found in countries and regions with a sizable number of Japanese immigrants, including Brazil with approximately 20,000 (Yamada 2010); Hawaii, with 2,000-2,500 (Takahashi 2014); and the U.S. mainland with approximately 2,000 (Kato 2011). There also are significant member pools in Japan’s former Japanese colonies, including South Korea, with approximately 270,000 (Lee 2011); and Taiwan, with approximately 20,000–30,000 (Fujii 2006; cf. Huang 2016). It is estimated that people of Japanese origin comprise the majority of followers in the immigrant-based regions as well as in other regions including Europe, but non-Japanese make up a large proportion or the entirety of adherents in some of the former Japanese colonies as well as in several other regions such as the Republic of the Congo (Fujii 2006; Lee 2011; Mori 2013).

Followers of Tenrikyō living in Japan as well as in other parts of the world are considered to be part of the larger organization  under Tenrikyo Church Headquarters (Tenrikyō kyōkai honbu). The organizational structure of Tenrikyō is mainly based on a centripetal principle centered on the religious authority of Tenrikyo Church Headquarters located at the Jiba. [Image at right] This principle involves two threads of organizational logic that are based on spiritual relationship and regional relationship, respectively. The first has to do with a parent-child relationship in which spiritual parents (ri no oya) are those who provide spiritual guidance to members who are, in terms of the religion, their children (ri no ko, “spiritual children”). In the organizational structure, this logic appears in the form of lineage (keitō). The Church Headquarters has about 240 directly supervised churches, the majority of which are known as grand churches (daikyōkai). These directly supervised churches each are connected with the Church Headquarters as their parent. The directly supervised churches in turn have their branch churches (bunkyōkai), thus comprising a chain of parent-child relationships in an institutional lineage structure. From a legal and financial point of view, a Tenrikyō church is an independent and autonomous social entity, but it is thus connected with other superior or subordinate churches in the wider spiritual hierarchy (Yamada 2012:325-28; cf. Morioka 1989:311-18). The second organizational logic concerns a network of churches in respective geographical regions. In Japan, each prefecture is defined as a diocese (kyōku) and is overseen by a Church Headquarters’ administrative office known as a diocese office (kyōmu shichō). In overseas countries, an equivalent function is undertaken by a mission headquarters (dendōchō), a mission center (shucchōsho), or a mission post (renrakusho), respectively, depending on the size of the church following in the country or region concerned. These regionally-based organizational units are intended to enhance the communication and interaction between followers belonging to different church lineages in a given geographical region. A Tenrikyō church is thus symbolically connected with the Church Headquarters in terms of the two interlacing organizational structures, with the spiritual relationship traditionally being the primary source of connection (Yamada 2012:325-28).

under Tenrikyo Church Headquarters (Tenrikyō kyōkai honbu). The organizational structure of Tenrikyō is mainly based on a centripetal principle centered on the religious authority of Tenrikyo Church Headquarters located at the Jiba. [Image at right] This principle involves two threads of organizational logic that are based on spiritual relationship and regional relationship, respectively. The first has to do with a parent-child relationship in which spiritual parents (ri no oya) are those who provide spiritual guidance to members who are, in terms of the religion, their children (ri no ko, “spiritual children”). In the organizational structure, this logic appears in the form of lineage (keitō). The Church Headquarters has about 240 directly supervised churches, the majority of which are known as grand churches (daikyōkai). These directly supervised churches each are connected with the Church Headquarters as their parent. The directly supervised churches in turn have their branch churches (bunkyōkai), thus comprising a chain of parent-child relationships in an institutional lineage structure. From a legal and financial point of view, a Tenrikyō church is an independent and autonomous social entity, but it is thus connected with other superior or subordinate churches in the wider spiritual hierarchy (Yamada 2012:325-28; cf. Morioka 1989:311-18). The second organizational logic concerns a network of churches in respective geographical regions. In Japan, each prefecture is defined as a diocese (kyōku) and is overseen by a Church Headquarters’ administrative office known as a diocese office (kyōmu shichō). In overseas countries, an equivalent function is undertaken by a mission headquarters (dendōchō), a mission center (shucchōsho), or a mission post (renrakusho), respectively, depending on the size of the church following in the country or region concerned. These regionally-based organizational units are intended to enhance the communication and interaction between followers belonging to different church lineages in a given geographical region. A Tenrikyō church is thus symbolically connected with the Church Headquarters in terms of the two interlacing organizational structures, with the spiritual relationship traditionally being the primary source of connection (Yamada 2012:325-28).

The leadership of the church hierarchy centers on the religious authority of the Shinbashira, which literally means the “central pillar.” As the administrative and spiritual leader of the entire Tenrikyō organization, the Shinbashira takes charge of officiating religious rites including the Kagura Service as well as bestow the Sazuke on behalf of the foundress (TOMD 1998:100). It is mandated that the Shinbashira should bear the family name of Nakayama, and the selection of a successor to the position is considered based on the lineage of the foundress (TOD 2010:389). As has been mentioned in the historical description above, the position of the Shinbashira has been traditionally held by direct male descendants or close male relatives in the lineages of the foundress. Under the Shinbashira, there are different ranks of church officials including the Director-in-Chief of Administrative Affairs (omote tōryō), the Director-in-Chief of Religious Affairs (uchi tōryō), headquarters executive officials (honbu-in), headquarters female officials (honbu fujin), and other ranks of senior and junior officials (TOD 2010:139-40). One can observe that most of these positions under the Shinbashira at the Church Headquarters are held by the descendants of the early followers. This family-oriented designation of leadership positions in the Church Headquarters to a large degree mirrors the internal structure of grand churches and branch churches (fieldwork observation).

Despite its close-knit institutional hierarchy centered on the religious authority of the Jiba, there have been numerous cases of schism particularly after the death of the foundress. Normally referred to as heretics (itan) by the Church Headquarters, these groups emerged at certain historical junctures of Tenrikyō’s development with a distinctive claim of salvific truth and related rituals that highlight certain aspects of Nakayama Miki’s teaching. The leaders of these groups have tended to view themselves as legitimate successors of the foundress. Depending on the time period in which these groups took form, they were marked with (1) an expectation for a prophetic figure descending from the spiritual lineage of Nakayama Miki and Iburi Izō; (2) an expectation for the appearance of a prophetic figure capable of effecting social change before the arrival of the end time; and (3) the emergence of religious leaders capable of performing mystical or magical healings. It must be noted that these cases of schism originated from the individual experiences of particular figures existing in periphery areas of the wider religious institution rather than as a result of organizational schism of a particular church. Some of these schismatic groups are Honmichi, Tenrin-Ō-Kyōkai, Shūyōdan Hōseikai, Morarojī Kenkyūsho, Seishōdō Kyōdan, Ōkanmichi, among many others (Yumiyama 2005).

In overseas contexts, one can identify a case of organizational schism in postwar South Korea. Unlike the aforementioned instances of schism in the Japanese context, Tenrikyō’s schism in South Korea was mainly triggered by a socio-political climate engendered by anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korean society. At the height of anti-Japanese sentiment in the public sphere coupled with the South Korean government’s suppression against religions of Japanese origin, a group of Tenrikyō followers in South Korea announced that they were changing their object of worship from a shrine to a model of Kanrodai in 1985. This has in turn led to the split of another group of followers aligning with the Church Headquarters’ orthodox view of the object of worship (Jin 2015, 2016).

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

Of all the possible issues and challenges facing the movement, five in particular are worth mentioning, namely, overseas mission, gender issues, Tenrikyō’s roles in society, assessment of prewar history, and membership decline.

In the context of overseas mission, some of the characteristics identifiable as associated with Japanese culture in Tenrikyō’s doctrines, practices, and its institutional and material cultures have had rather ambivalent consequences. The association with Japan and Japanese culture, such as the shrine being the object of worship, has been considered to be a source of difficulty for propagating the religious teaching in South Korea, where anti-Japanese sentiment runs high (Jin 2015, 2016). In a place like Brazil, the centripetal principle of the organizational structure of Tenrikyō has at times led to the appreciation of Japan and its language among followers of Japanese descent, effecting in further consolidation of Tenrikyō as an ethnic religious community (Yamada 2012). At the same time, however, the association with Japan and Japanese culture has served as a resource to attract non-Japanese people in some other regions. This includes Taiwan, where some parts of the population view Japan as a model to follow in contrast to that of the Nationalist government from the mainland China (Huang 2016), and the Republic of Congo and Nepal, where the symbol of religious authenticity is converged with the image of Japan as an industrially developed nation among local members (Mori 2013:131-34; Marilena Frisone, personal communication). Also worth noting in terms of the association with Japan is that Tenrikyō has used Japanese cultural resources (e.g., in the form of Japanese language schools) as a way of increasing the visibility of the group and attracting potential members in such regions as France, New York, and Singapore, where Tenrikyō has established Japanese cultural centers. In relation to the language, the Mikagura-uta can be sung only in the original Japanese except in South Korea, where it is sung in Korean, something that has occurred due to the political circumstances in the country in addition to the similar grammatical structure of the two languages. To address this linguistic limitation, there has been a grassroots initiative in recent years among followers in English-speaking countries to create a “Singable-Danceable Mikagura-uta” (utatte odoreru Mikagura-uta) that can be sung and danced in English (fieldwork observation; see also Inoue 2015). Another potential issue with regards to the overseas mission is that members need to go to the Jiba to become a Yoboku and attend some of the seminars and courses required to obtain certain qualifications, which can be at times difficult for overseas followers due to the time and financial cost for the travel (fieldwork observation).

As is implied in the description of the organizational structure, Tenrikyō also shows ambivalence in its doctrinal views and institutional practices relating to gender orientation. Despite originating from a female leader, Tenrikyō has developed and maintained a rather male-oriented organizational structure with, for example, having only one female honbu-in in its history (Watanabe 2015:15). It also emphasizes the relationship between husband and wife based on the modern sense of gender division of labor with some remaining influence of the household ie system of premodern society, a view that was developed based on a particular interpretation of the foundress’s words in the context of Japan’s modern period (Kaneko J. 2003). It is in fact pointed out that while Miki emphasized the salvation of both men and women as well as contravening traditional taboos concerning women’s bodies, she did not necessarily go beyond the conventional gender roles of men as fathers and women as mothers (Ambros 2013). At the same time, however, the foundress did not necessarily consider married life as an ideal way of living for everybody, for example, encouraging women with certain religious roles such as Kokan to live a single life. In recent times, moreover, the practice of foster parents in local churches is said to show an example of the practice of a “church family” (kyōkai kazoku), which in some ways transcends the configuration of modern nuclear family (Kaneko J. 2003).

Where it concerns social issues, Tenrikyō has been quite active in some social welfare activities including foster parents as well as in disaster relief hinokishin activities in the wake of natural disasters (TOMD 1998:138-141; see also Ambros 2016; Kaneko A. 2002; Kisala 1992). At the same time, however, it has been pointed out that Tenrikyō does not take a clear stance towards certain social or political issues, largely due to the emphasis on the spiritual dimension of salvation in the postwar doctrine (Hatakama 2013). This aspect can be said to have been partly addressed by the initiative of Tenri Yamato Culture Congress (Tenri Yamato bunka kaigi) with the publication of its proceeding known as Michi to shakai (Tenrikyō and Society) in 2004, which contains discussions of various topics including bioethics, environmental issues, and family issues such as domestic violence. The discussion in the book highlights some of the doctrinal concepts as guiding principles to understand these issues from Tenrikyō’s doctrinal viewpoint, i.e., in terms of organ transplants viewing the body as “a thing lent, a thing borrowed,” the universe as the body of God for environmental issues, causality and free use of mind for family issues, to name but a few. The discussion tends to avoid taking sides in controversial issues, although it expresses a certain degree of reservation against the practice of organ transplant on the basis of the teaching of a thing lent, a thing borrowed. In recent years, there has been relatively less concerted efforts to address social issues from Tenrikyō’s standpoint, but individual issues are occasionally discussed in the group’s official publications including Michi no tomo magazine, Tenri jihō newspaper, and Arakitōryō magazine.

As for the interpretation of prewar history, Tenrikyō’s official view has it that the religious institution complied with Japan’s modern state ideology by modifying its doctrines and practices on the surface level while maintaining in the undercurrent the original teaching and practices as taught by Miki (Tenrikyō Omote Tōryōshitsu Tokubetsu Iinkai 1995:44-46). In recent years, however, some scholars have questioned and nuanced this view, which they call the “discourse of two-tier structure” (nijū kōzō ron), by applying historical approaches that highlight a certain level of historical continuity between the prewar and postwar doctrines and practices (see for example Hatakama 2006, 2007, 2012; Nagaoka 2015). Though these scholarly views may not converge with those of scholars affiliated with Tenrikyō, there has recently been an attempt of scholarly dialogue at a special session entitled “Reviewing the Current State of Research on Tenrikyō: Historical Approaches” (Tenrikyō kenkyū no genzai: Rekishi kara tou) at the 2014 annual conference of the Japanese Association for the Study of Religion and Society (“Shūkyō to shakai” gakkai) (Nagaoka et al. 2015). In this panel, historians sought to nuance the evaluation of prewar history in Tenrikyō’s official doctrinal discourse, which are in one way or another shared among scholars studying new religions, by employing approaches derived from the study of deconstruction and postcolonial studies. The discussion in the panel involved responses from scholars affiliated with new religions including Tenrikyō and Konkōkyō, thus being a rare case of a dialogue between two parties sharing different views on the prewar history of new religions (Nagaoka et al. 2015).

As has been briefly mentioned above, the movement has faced a declining membership in recent years, with the membership dropping approximately by 200,000 every ten years between 1986 and 2006. In a statistical review published in 2008, the declining membership is attributed to the passing of elderly followers, the declining number of people starting to attend the Besseki lectures as well as those who receive the truth of the Sazuke, and the declining number of Yoboku who participate in church activities (Tenrikyō Omote Tōryōshitsu Chōsa Jōhōka 2008:8-9, 14, 26, 29). To address this issue, Tenrikyo Church Headquarters has made various attempts to date. These include the manual distribution of the movement’s weekly newspaper, Tenri jihō, among followers living in the same region (Michi no Tomo Henshūbu 2009:10-13) as well as launching training courses such as Tenrikyo Basics Course (Tenrikyō kiso kōza) and Three Day Course (Mikka kōshūkai), which are designed for people who are new to Tenrikyō and followers who cannot take a long leave from work, respectively (Michi no Tomo Henshūbu 2003a, 2003b). These initiatives, among others, are intended to help missionaries to attract new members to the movement as well as help churches to encourage existing members to learn and practice the teaching.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph the Ofudesaki (The Tip of the Writing Brush)

Image #2: Photograph of the instruments used in the performance of tsutome.

Image #3: Photograph of the Sazuke ritual being performed by a Yoboku.

Image #4: Photograph of the Tenri Yorozu-Sodansho Foundation’s Ikoi no Ie Hospital.

Image #5: Photograph of the headquarters of Tenrikyō (Tenrikyō kyōkai honbu).

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

Arakitōryō Henshūbu. 2002. “Oyasama go-nensai wo moto ni kyōshi wo furikaeru.” Arakitōryō 209:8-71.

Michi no Tomo Henshūbu. 2009. “’Tenri jihō fukyū he no torikumi.” Michi no tomo 119:8-25.

Michi no Tomo Henshūbu. 2003a. “Kyōka ikusei no shin shisutemu to wa: Tenrikyō kiso kōza.” Michi no Tomo 113:8-15.

Michi no Tomo Henshūbu. 2003b. “Kyōka ikusei no shin shisutemu: Mikka kōshūkai.” Michi no Tomo 113:10-19.

Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1998. Ofudesaki: The Tip of the Writing Brush. Tenri: Tenrikyo Church Headquarters.

Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1996. The Life of Oyasama, Foundress of Tenrikyo: Manuscript Edition. Third Edition. Tenri: Tenrikyo Church Headquarters.

Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. 1993. The Doctrine of Tenrikyo. Tenth Edition. Tenri: Tenrikyo Church Headquarters.

Tenri Daigaku Fuzoku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. 1997. Kaitei Tenrikyō jiten. Tenri: Tenrikyō Dōyūsha.

Tenrikyō Dōyūsha, ed. 2016. Bijuaru nenpyō Tenrikyō no hyaku sanjū nen: Meiji 21 nen (1888)—Heisei 27 nen (2015). Tenri: Tenrikyo Dōyūsha.

Tenrikyo Doyusha Publishing Company. 2014. Tracing the Model Path: A Close Look into The Life of Oyasama. Tenri: Tenrikyo Doyusha Publishing Company.

Tenrikyō Omote Tōryōshitsu Chōsa Jōhōka, ed. 2008. Dai 8 kai kyōsei chōsa hōkoku. Tenri: Tenrikyō Kyōkai Honbu.

Tenrikyō Omote Tōryōshitsu Tokubetsu Iinkai, ed. 1995. Sekai tasuke he saranaru ayumi wo: “Fukugen” gojū nen ni atatte. Tenri: Tenrikyo Dōyūsha.

Tenrikyo Overseas Department. 2010. A Glossary of Tenrikyo Terms. Tenri: Tenrikyo Overseas Department.

Tenrikyo Overseas Department. 2009. “A Statistical Review of Tenrikyo.” Tenrikyo, January 26, pp. 4.

Tenrikyo Overseas Department. 2004. Yoboku’s Guide to Tenrikyo. Tenri: Tenrikyo Overseas Department.

Tenrikyo Overseas Mission Department. 1998. Tenrikyo: The Path to Joyousness. Tenri: Tenrikyo Overseas Mission Department.

Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no Taiwa Soshiki Iinkai. 1998. Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no taiwa. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no Taiwa II Soshiki Iinkai. 2005. Tenrikyō to Kirisutokyō no taiwa II. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Tenri Yamato Bunka Kaigi, ed. 2004. Michi to shakai: Gendai “jijō” wo shian suru. Tenri: Tenrikyo Dōyūsha.

Secondary Sources

Ambros, Barbara. 2016. “Mobilizing Gratitude: Contextualizing Tenrikyō’s Response after the Great East Japan Earthquake.” Pp. 132-55 in Disasters and Social Crisis in Contemporary Japan: Political, Religious, and Sociocultural Responses, edited by Mark R. Mullins and Koichi Nakano. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ambros, Barbara R. 2013. “Nakayama Miki’s View of Women and Their Bodies in the Context of Nineteenth Century Japanese Religions.” Tenri Journal of Religion 41:85-116.

Astley, Trevor. 2006. “New Religions.” Pp. 91-114 in Nanzan Guide to Japanese Religions, edited by Paul L. Swanson and Clark Chilson. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Ellwood, Robert. 1982. Tenrikyo: A Pilgrimage Faith: The Structure and Meanings of a Modern Japanese Religion. Tenri: Oyasato Research Institute, Tenri University.

Fujii, Takeshi. 2006. “Sengo Taiwan ni okeru Tenrikyō no tenkai.” Tenri Taiwan gakuhō 15:63-75.

Hardacre, Helen. 1994. “Conflict between Shugendō and the New Religions of Bakumatsu Japan.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 21:137-66.

Hatakama, Kazuhiro. 2013. “Oshie no ashimoto wo terasu: ‘Fukugen’ to shakai.” Pp. 59-83 in Gendai shakai to Tenrikyō, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Hatakama, Kazuhiro. 2012. “Kōhon Tenrikyō kyōsoden no seiritsu.” Pp. 193-240 in Katarareta kyōso: Kinse kingendai no shinkōshi, edited by Kazuhiro Hatakama. Kyoto: Hōzōkan.

Hatakama, Kazuhiro. 2007. “Hataraki Hinokishin” Pp. 85-130 in Tenrikyō no kosumorojī to gendai, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Hatakama, Kazuhiro. 2006. “’Fukugen’ to ‘Kakushin.’” Pp. 137-73 in Sensō to shūkyō, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Huang, Yueh-po. 2016. “Colonial Encounter and Inculturation: The Birth and Development of Tenrikyo in Taiwan.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions 19:78-103.

Ikeda, Shirō. 2006 [1996]. Nakayama Miki to hisabetsu minshū: Tenrikyō kyōso no ayunda michi. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Inoue, Akihiro. 2013. “’Ojiba gaeri’ no junrei ron.” Pp. 167-83 in Gendai Shakai to Tenrikyō, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Inoue, Akihiro. 2015. “Eigo ken ni okeru Tenrikyō dendō: Hawai, Hokubei wo chūshin ni.” Shūkyō to Shakai 21:171-73.

Jin, Jonghyun. 2016. “Kankoku ni okeru Tenrikyō no tenkai: Sengo no kattō to henyō wo megutte.” Jisedai jinbun shakai kenkyū 12:181-97.

Jin, Jonghyun. 2015. “Sengo no Kankoku ni okeru Nikkei shinshūkyō no tenkai: Tenrikyō no genchika wo megutte.” Kankokugaku no furontia 1:42-59.

Kaneko, Akira. 2002. Kaketsukeru shinkōsha tachi: Tenrikyō saigai kyūen no hyakunen. Tenri: Tenrikyō Dōyūsha.

Kaneko, Juri. 2003. “Can Tenrikyō Transcend the Modern Family? From a Humanistic Understanding of Hinagata and Narratives of Foster Care Activities.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 30:243–58.

Kaneko, Keisuke. 2000. Kaitei zōho Tenrikyō dendōshi gaisetsu. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Kato, Masato. 2011. “Nikkei Amerikajin Tenrikyō shinja no kenkyū: San Furanshisuko Bei Eria zaijū Nikkei Shin-Nisei shinja no jirei wo tōshite.” Pp. 83-113 in Amerikasu no Tenrikyō: Nanboku Amerika ni okeru dendō no shosō to tenbō, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūsho. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Kisala, Robert. 1992. Gendai shūkyō to shakai rinri: Tenrikyō to Risshō Kōseikai no fukushi katsudō wo chūshin ni. Tokyo: Seikyūsha.

Lee, Won Bum. 2011. “Kankoku ni okeru Nihon no shinshūkyō.” Pp. 55-84 in Ekkyō suru Nikkan shūkyō bunka: Kankoku no Nikkei shinshūkyō, Nihon no Hanryū Kirisutokyō, edited by Won Bum Lee and Yoshihide Sakurai. Sapporo: Hokkaidō Daigaku Shuppankai.

Lee, Won Bum. 1994. “Kindai Nihon no tennōsei kokka to Tenri kyōdan: Sono shūdanteki jiritsusei no keisei katei wo megutte.” Pp. 18-62 in Nanno tame no “shūkyō” ka: Gendai shūkyō no yokuatsu to jiyū, edited by Susumu Shimazono. Tokyo: Seikyūsha.

Mori, Yōmei. 2013. Dendō shūkyō ni yoru ibunka sesshoku: Tenrikyō Kongo dendō wo tsūjite. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Morioka, Kiyomi. 1989. Shinshūkyō undō no tenkai katei. Tokyo: Sōbunsha.

Nagaoka, Takashi. 2016. “Kyoso no kazoku shashin wo meguru oboegaki.” Pp. 378-90 in Ishibashi hyōron: Cultures/Critiques bessatsu, edited by Ishibashi hyōron henshūbu. Osaka: Kokusai Nihongaku Kenkyūkai.

Nagaoka, Takashi. 2015. Shinshūkyō to sōryokusen: Kyōso igo wo ikiru. Nagoya: Nagoya Daigaku Shuppankai.

Nagaoka, Takashi, et al. 2015. “Tenrikyō kenkyū no genzai: Rekishi kara tou.” Shūkyō to Shakai 21:159-68.

Ōya, Wataru. 1996. Tenrikyō no shiteki kenkyū. Osaka: Tōhō Shuppan.

Personal Note. n.d. I wish to thank Marilena Frisone for drawing my attention to this point.

Shimazono, Susumu. 1998. “Utagai to shinkō no aida: Nakayama Miki no tasuke no shinkō no kigen.” Pp. 71-117 in Nakayama Miki, sono shōgai to shisō: Sukui to kaihō no ayumi, edited by Shirō Ikeda, Susumu Shimazono, and Kazutoshi Seki. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Takahashi, Norihito. 2014. Imin, shūkyō, kokoku: Kingendai Hawai ni okeru Nikkei shūkyō no keiken. Tokyo: Hābesutosha.

Tsujii, Masakazu. 1997. “Gendai sekai ni okeru Tenrikyō no fukyō dendō: Kyōkai tōkei wo tegakari ni.” Pp. 47-76 in Tenrikyō no fukyō dendō, edited by Tenri Daigaku Oyasato Kenkyūjo. Tenri: Tenri Daigaku Shuppanbu.

Watanabe, Yū. 2015. “Kyōso no shintai: Nakayama Miki kō.” Kyōseigaku 10:6-44.

Yamada, Masanobu. 2012. “Tenrikyō no kyōdan keiei rinen to Burajiru ni okeru tenkai.” Pp. 324-42 in Gurōbaruka suru Ajia kei shūkyō: Keiei to māketingu, edited by Hirochika Nakamaki and Wendy Smith. Osaka: Tōhō Shuppan.

Yamada, Masanobu. 2010. “Tenrikyo in Brazil from the Perspective of Globalization.” Revista de Estudos da Religião 10:29–49.

Yumiyama, Tatsuya. 2005. Tenkei no yukue: Shūkyō ga bunpa suru toki. Tokyo: Nihon Chiiki Shakai Kenkyūsho.

Post Date:

13 March 2017

Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona

FERENZONA TIMELINE

1879 (September 24): Raoul Ferenzona was born in Florence, Italy.

1880 (April 19): Ferenzona’s father, a controversial political journalist who wrote under the pseudonym “Giovanni Antonio Dal Molin,” was assassinated in Livorno. Raoul would later change his last name to “Dal Molin Ferenzona” to honor his father.

1890 (ca): Ferenzona was enrolled in a military college in Florence and subsequently in the Military Academy in Modena.

1899: Ferenzona published in Modena his first book: Primulae – novelle gentili (Primulas – Gentle Tales), a collection of tales.

1900: Ferenzona made his first artistic apprenticeship in Palermo under the guidance of the sculptor Ettore Ximenes.

1901: Ferenzona was admitted to the Art Academy in Florence, renowned at that time for its nude art classes.