BISSU TIMELINE

2500 B.C.E.: The ancestors of the Buginese people settled in Sulawesi, the third largest Island in present-day Indonesia.

1544: Portuguese merchant Antonio de Paiva wrote a letter from Sulawesi, the home of bissu, back to Portugal describing bissu.

1848: European traveller James Brooke visited Sulawesi and recorded notes about bissu in his journal.

1960s: Bissu were severely suppressed with the advent of Islamic fundamentalism.

1990s-early 2000s: Puang Matoa Saidi served as the recognized leader of the bissu.

1990s-2015: There has been some revitalization of the bissu but primarily with respect to offering rituals for commoners and some supporting tourism.

2015- onwards: There has been increasing persecution at political and legal levels towards any type of gender, sexual and spiritual diversity. This persecution is harming bissu and traditional belief systems more generally.

FOUNDER/GROUP HISTORY

Prior to the coming of Islam, and to a lesser extent Christianity, many people in Indonesia followed a form of animism, often influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. The form of spirituality they followed allowed for the worship of animals, the erection of alters, and the development of idols. When Islam came in the 1500s, much of this form of animism was removed; however, other parts of it were syncretised with Islam. Indeed, it was bissu, which is ironic since many Muslims see bissu as anti-Islamic, who convinced the rulers of South Sulawesi to convert to Islam. Bissu were thus in a position to incorporate some of their significant pre-Islamic beliefs with more orthodox Islamic ones.

Depending on how the notion of gender is defined, it is possible to say that Bugis people recognise five genders: makkunrai, oroané, calabai, calalai, and bissu. While the terms are not necessarily cognate with Western conceptions of gender, it is possible to say that makkunrai are feminine female women, oroané are masculine male men, calabai are feminine males, calalai are masculine females and bissu combine elements of female and male. Bissu are cognate with a number of other spiritual roles around the world whereby those in power draw on a combination of female and male elements, such as hijra in India (Nanda 1990) and two-spirit people in North America (Jacobs,  Thomas, Lang 1997) and indeed across Southeast Asia (Peletz 2006).

Thomas, Lang 1997) and indeed across Southeast Asia (Peletz 2006).

Bissu [Image at right] are an order of spiritual guides who offer support and assistance to people on the island of Sulawesi in Indonesia. Many believe that bissu get their spiritual power from being a combination of female and male elements. Bissu can bestow blessings on people to ensure good marriage alliances, successful harvests and safe travels, including to Mecca for the Islamic pilgrimage.

The earliest written historical evidence available on the role and position of bissu comes from European travellers to the region who recorded their journeys. For instance, in 1544 Portuguese merchant Antonio de Paiva spent time in Sulawesi, the home of bissu. He then wrote a letter back to Portugal saying:

Your Lordship will know that the priests of these kings are generally called bissus. They grow no hair on their beards, dress in a womanly fashion, and grow their hair long and braided; they imitate [women’s] speech because they adopt all of the female gestures and inclinations. They marry and are received, according to the custom of the land, with other common men, and they live indoors, uniting carnally in their secret places with the men who they have for husbands. This is public [knowledge], and not just around here, but on account of the same mouths which Our Lord has given to proclaim his praise. These priests, if they touch a woman in thought or deed, are boiled in tar because they hold that all their religion would be lost if they did it; and they have their teeth covered in gold. And as I say to Your Lordship, I went with this very sober thought, amazed [that] Our Lord would destroy those three cities of Sodom for the same sin and considering how a destruction had not come over such a wanton people as these in such a long time and what was there to do, for the whole land was encircled by evil. (cited in Baker 2005:69)

Some years later another European traveller, James Brooke, came to Sulawesi. He recorded in his journal notes about bissu and also calalai’ (etymologically “false men”) and calabai’ (etymologically “false women”). Brooke wrote that:

The strangest custom I have observed is, that some men dress like women, and some women like men; not occasionally, but all their lives, devoting themselves to the occupations and pursuits of their adopted sex. In the case of the males, it seems that the parents of a boy, upon perceiving in him certain effeminacies of habit and appearance, are induced thereby to present him to one of the rajahs, by whom he is received. These youths often acquire much influence over their masters. (Brooke 1848:82-83)

There is also of course evidence of bissu prior to European exploration but it comes to us in the stories of the past (Pelras 1996). For instance, there are many origin narratives retold in Sulawesi about the founding of the world and how bissu were sent down from the heavens and up from the underworld to ensure the flourishing of humanity on earth.

We also have evidence of bissu through the writings of indigenous sages. Indeed, writing has been in use in Sulawesi since at least the fifteen century if not earlier. Sadly, though, the oldest known surviving Bugis manuscript dates from the early 1700s (Noorduyn 1965). W\e therefore cannot know for certain about the role of bissu before the 1500s when de Paiva visited. But from the 1700s there are thousands of indigenous documents available, many of which talk about the role of bissu. Manuscripts recount bissu playing key roles in state affairs. There are manuscripts that note battles between the sixteenth and twentieth centuries where bissu helped Bugis win key victories against the Dutch. Other manuscripts talk about battles where bissu marched toward an invading army, impervious to the flood of bullets. As they combine male and male energies. bissu could communicate with the spiritual world to gain protection during battle. Manuscripts also talk of bissu occupying key roles across generations of Bugis royal courts, advising rulers who to marry, when to go to war and about good trading practices (Andaya 2000).

As of 2018, the position of bissu is perhaps more precarious than in the past. Indeed, bissu face many contemporary challenges and issues which are discussed below.

DOCTRINES/BELIEFS

While bissu were practising long before Islam came to Indonesia, bissu in contemporary society amalgamate pre-Islamic beliefs with Islamic ones. In the past bissu and their adherents would worship at alters and to idols believed to represent the gods. Islam does not permit this, and so bissu no longer undertake such practices. Further, bissu used to also offer food sacrifices such as pork (which was a staple food source before Islam), but again as Muslims, bissu have altered these practices. Food sacrifices are still made, but all the food offered is halal. And after the spirits have taken the essence of the food, the food is consumed so as not to waste it, which would be considered a sin under Islam. One of the most frequently requested blessings for bissu to conduct is to bless the trip of a person about to make the haj pilgrimage to Mecca. Indeed, a number of bissu are themselves hajji, meaning they have previously undertaken the pilgrimage to Mecca.

One of the key bases for bissu being able to bestow blessings is that they are considered to embody both female and male elements. This undifferentiated combination of female and male means that bissu have been able to retain their connection with the spirit world, something that is severed when humans differentiate into female or male. The acknowledgement that humanity is diverse in both gender, sexuality and biology has been a powerful antidote to arguments that all individuals should be either just female or male.

RITUALS/PRACTICES

Bissu have played a key role in the cultural and religious life of Bugis Indonesians for many hundreds of years. This role has decreased in recent decades, but bissu still form an important part of Bugis life. People seek the assistance of bissu for many reasons, including blessing the birth of a new born baby. Rituals are performed in a variety of ways. Often, people seeking a blessing travel to the house of a bissu who may have a special room dedicated to blessings. In this room might be ornately decorated cloth, bowls and plates of ritual significance, and lots of burning incense. The person seeking a blessing will sit on the floor in front of bissu and, for a simple blessing, bissu recount a poem, rotate incense smoke and wish the person well.

In more elaborate blessings, such as that for a successful harvest for an entire village, ten or more bissu may be involved. Other large blessings are conducted for events such as the water festival, the planting of crops and for the marriages of the nobility. Such a large blessing may require that bissu demonstrate their ability to give a blessing, which they do by performing the ma’giri.

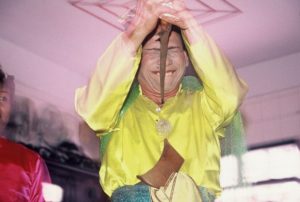

Ma’giri is a ritual self-stabbing exercise where bissu prove they are possessed by powerful spirits, and thus capable of bestowing a blessing, by taking a knife or kris and attempting to stab themselves with it. [Image at right] Bissu take the knife and force it into sensitive parts of their body such as neck and eye. If the blade fails to enter, even under great pressure, the bissu has shown proof that they are invulnerable (kebal) and thus possessed by a powerful spirit and therefore able to grant a blessing.

Ma’giri performances are incredibly dramatic and can involve a dozen bissu dancing and performing in a circle all stabbing themselves in increasingly heated movements. The room fills with incense smoke and musicians seated on the floor around the bissu pound drums and other instruments making the experience all the more intense. These performances are attended by everyone in the village from the very young to the very old and can last many hours, although the actual ma’giri performance is usually less than an hour. The preparation leading up to the performance takes days, with the whole village participating in various ways from weaving baskets, to decorating the room to cooking copious amounts of food for both the sprits and the participants.

While many of the blessings are performed for local people of modest means, bissu are also involved in hugely elaborate ceremonies for the rich and famous. One particularly activity in which bissu are involved is the marriage ceremonies of the very wealthy and of the nobility. Such weddings are often planned years in advance and bissu play key roles in ensuring the wedding is a success. Bissu can connect with the spirit world to choose an auspicious date for the wedding, which can on occasion take place over an entire week. Bissu have separate appointments with both the bride and groom to connect them with the spirit world and to ensure that the match will be a successful one both in terms of compatibility and fecundity. Bissu play a role in the beautification of the bride, organising for her skin treatments, hair treatments and selecting clothes that look both attractive and have symbolic meaning. Bissu will also prepare ritual food to be consumed after the spirits have taken the essence of it. Bissu will bless the marital bed to ensure children will result from the marriage. All of this is performed, in the case that the marital couple are Muslim, in ways that are compatible with Islam. The ability of bissu to draw on previous animistic beliefs and adapt and modify these to fit with contemporary Islam has enabled bissu to stay relevant to the current day.

ORGANIZATION/LEADERSHIP

For most of the 1990s and early 2000s, the generally recognised leader of bissu was Puang Matoa Saidi. [Image at right] Puang Matoa is a Bugis word for leader. Puang Matoa Saidi travelled with Robert Wilson and his theatre company to stage the production of La Galigo in Asia, Europe and the US. La Galigo was a stage play based on Bugis origin narratives and thus bissu played an instrumental role.Sadly, Puang Matoa Saidi passed away from tuberculous in the mid-2000s. A number of bissu have stepped into the role of Puang Matoa since Saidi’s passing but none have yet achieved the level of seniority that Saidi had. There is also a long lineage of bissu before Puang Matoa Saidi, and while many originate from the same area as Puang Matoa Saidi (Pangkep and Segeri), others hail from places such as Pare-Pare (for instance Puang Matoa Haji Gandaria) and also the area of Bone in South Sulawesi.

While a possible ally in establishing a legitimate social space might be collaboration between bissu and LGBT groups in Indonesia, this has not occurred on a large scale. The LGBT movement is currently considered a threat to national security in Indonesia, according to recent Tweets by Indonesia’s national security advisor. Any sign of an LGBT movement advocating for legal and political rights is quickly shut down by the government. But events that have been happening in Indonesia since the 2016 start of the “LGBT Crisis” might necessitate all gender and sexually diverse groups working together in solidarity to force Indonesia along a path of tolerance and not intolerance.

International attention given to bissu has both helped and hindered the group. Through the work of stage plays, documentaries and other media coverage, people outside Sulawesi, and even within the region, are increasingly aware of the dynamic spiritual history of the area. However, this attention has also provoked negative response among some sections of society who see bissu are threatening some parts of social life. In particular, those who do not understand the strategic ways in which bissu have amalgamated their beliefs with those of Islam feel that bissu might undermine Islam in the region. In contrast, though, many bissu are amongst the strongest supports of Islam. Indeed, bissu Haji Gandaria could proudly boast of making the haj to Mecca no less than three times during his life.

ISSUES/CHALLENGES

While events such as Robert Wilson’s stage play La Galigo brought bissu to world attention, domestic events are having a devastating impact on LGBT in Indonesia, including bissu. In 1998, authoritarian leader President Suharto was overthrown in Indonesia marking Indonesia’s experiment with democracy. While democracy brought many advantages to Indonesia, including the establishment of a Human Rights Commission, it also brought many devastating impacts. One of these impacts was the rise of hate speech and intolerance. Indeed, Indonesia’s province of Aceh now has laws criminalising homosexuality; moreover, any displays of gender diversity or of spiritual diversity are severely punished.

While under Suharto life was not easy for LGBT Indonesians, including bissu, they were rarely the explicit target of hate campaigns. Under democracy, however, right wing extremism, often extending from an Islamicist perspective, has seen a rise in violence against LGBT Indonesians. Indeed, there are currently moves at senior political and legal levels to criminalise all forms of sexuality outside marital heterosexuality. Moreover, non-normative genders are also under increasing pressure to conform to very limited forms of self-expression. It is thus unclear what the future will look like for bissu. It can only be hoped that Indonesia recognises its incredible past of such gender and sexual diversity, and the important spiritual and social role that bissu have played in the community for centuries and that their subject position will be honoured not repressed.

IMAGES

Image #1: Photograph of a group of bissu.

Image #2: Photograph of a bissu performing the ma’giri ritual.

Image #3: Photograph of Puang Matoa Saidi.

REFERENCES **

** Unless otherwise noted, this profile draws on my work cited in the reference list.

Andaya, Leonard. 2000. “The Bissu: Study of a Third Gender in Indonesia.” Pp. 27-46 in Other Pasts: Women, Gender, and History in Early Modern Southeast Asia, edited by Barbaraatson Andaya. Honolulu: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of Hawai’i.

Baker, Brett. 2005. “South Sulawesi in 1544: A Portuguese Letter.” Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 39:61-85.

Davies, Sharyn Graham. 2016. “Indonesia’s Anti-LGBT Panic.” East Asia Forum 8:8-11.

Davies, Sharyn Graham. 2015a. “Performing Selves: The Trope of Authenticity and Robert Wilson’s Stage Production of I La Galigo.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 46:417-43.

Davies, Sharyn Graham. 2015b. “Sexual Surveillance.” Pp. 10-31 in Sex and Sexualities in Contemporary Indonesia: Sexual Politics, Health, Diversity and Representations, edited by Linda Rae Bennett and Sharyn Graham Davies. London: Routledge.

Davies, Sharyn Graham. 2011. Gender Diversity in Indonesia: Sexuality, Islam, and Queer Selves. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Jacobs, Sue-Ellen, Wesley Thomas, and Sabine Lang. 1997. Two-spirit People: Native American Gender Identity, Sexuality, and Spirituality. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Matthes, B. F. 1872. “Over de Bissoe’s of Heidensche Priesters en Priesteressen der \ Boeginezen.” Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Akademie can Wetenschappen, Afdeeling Letterkunde 17:1-50.

Nanda, Serena 1990. Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Noorduyn, J. 1965. “Origins of South Celebes Historical Writing.” Pp. 137-55 in An Introduction to Indonesian Historiography, edited by Soedjatmoko. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Peletz, Michael G. 2006. “Transgenderism and Gender Pluralism in Southeast Asia since Early Modern Times.” Current Anthropology 47: 309-40.

Pelras, Christian. 1996. The Bugis. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Post Date:

19 July 2018